The Prairie on Fire.

Title: The American family Robinson

or, The adventures of a family lost in the great desert of the West.

Author: D. W. Belisle

Release date: February 15, 2008 [eBook #24621]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

The lofty mountains, mighty forests, rivers and valleys of the West, many portions of which have never been explored, furnish abundant resources for the gratification of the Naturalist, the Lapidary, and the Antiquarian. It is with the view of directing attention to these sources of information, that the author has grouped together in this little work, many startling incidents in prairie life, and alluded to relics of antiquity, bearing unmistakable indications of a high order of civilization and science, in regard to which subsequent discoveries have proved the hypothesis he assumes correct. That this country has been peopled by a civilized race of sentient beings anterior to the existence of the present tribes of Indians or their ancestors, is no longer a matter of uncertainty; for everywhere throughout the West, and in many places East of the Mississippi Valley, incontrovertible evidences attest the high antiquity of monuments and relics of a people, whose race, name and customs have been lost in the deep gloom that hangs over the mighty past. In order more successfully to call attention to these ancient reminiscences of our own country, and to incite a spirit of inquiry in the minds of the young, he has incidentally alluded to them while following the family of Mr. Duncan in their toilsome journey and wanderings through the Great American Desert. To those unacquainted with the antiquarian characteristics of this continent, some of the allusions may appear improbable; yet sufficiently competent authority has been consulted in the preparation of this work to give the allusions reliable authenticity. If we shall be successful in awakening such an inquiry, we shall be content, and feel that our labors have not been unrewarded.

Philadelphia 1853.

| PAGE |

| Mr. Duncan's Discontentment. He starts for the West in search of a place of Settlement. | 9 |

| The Journey. Encampment. Buffalo hunt. Anne and Edward lost. They discover an old fort. Fight with a Wolf. Take refuge in a Tree. Rescued by Howe and Lewis. Return to the Camp. | 16 |

| Howe's Story of a singular piece of Metal, resembling a shield or helmet, found on Lake Superior. | 36 |

| Their journey continued. Finding a Prairie. Encamping for the Night. Singular incident. A Mirage on the Prairie. The Prairie on fire. Flight to the Sand Hills. Their final escape. Finding a stream. Encampment. | 49 |

| Heavy Storm. Straggling Indians seen. Preparations for defence. A friendly Indian approaches and warns them of their danger. The Camp Attacked. Capture of Five in the Camp. Recovery of some of the Captured. | 62 |

| Strength of the Tabagauches. Attack of their camp. Flight of the Whites. Pursuing the Indians. Desperate Engagement. Taken Prisoners. Carried off captives. Singular Springs of Water. Kind treatment by the Indians. Discovery of Gold. | 81 |

| Their continued Captivity. They are cautiously watched and guarded. A singular Cave. Preparations to escape into it. Lassoing the Guard. Enter the Cavern and close the Door. They are missed by the Indians. They follow the Cavern. Mysterious discoveries. Discovery of an outlet. They halt for repose. | 100 |

| Entering the unknown Wilds. Their encampment attacked by Panthers. They save themselves. The Panthers kill one of their pack. They continue their journey. Whirlwind becomes lost. Everything strange about them. Encampment at the base of a mountain. | 122 |

| Encounter with a Wolf. Sidney seriously wounded. Whirlwind procures medicine. They Build a Cabin. Fears entertained of Sidney's death. Talk of Pow-wowing the disease. Miscellaneous conversation on the matter. Their final consent to the Pow-wow. | 137 |

| The apparent solemnity of Whirlwind. The Pow-wow. Its effects upon Sidney. Favourable turn in his fever. His health improves. They proceed on their way. Encamp for the night. Singular trees discovered. Preparations for spending the winter. | 151 |

| Search for winter quarters. Strange Discoveries. Works of the lost people. Their search among the Ruins. Walls, roads, and buildings found. Their state of Preservation. They prepare to locate themselves. A salt spring. Their joy at their discoveries. | 163 |

| Astonishment of the Children. The Antiquity of the Ruins. The Chief's contentment. Strange discoveries. Discovery of wild horses. The chief captures a colt. The winter sets in. A series of storms prevail. They discover an Indian woman and her papoose. | 174 |

| Jane's reception of the Indian woman. Condition of the party. They cannot calculate the day nor month. The chief imagines he has found the Arapahoes' hunting grounds. Deer chased by a wild man. The chief lassoes him. A desperate struggle. The wild man captured and taken into camp. | 193 |

| The return of spring. Their thoughts of home. Preparations to continue their journey. Escape of the Wild Man. They suffer from want of water. A party of Indians. A beautiful Landscape. A terrific storm. The chief rendered insensible by a stroke of lightning. He recovers and returns to the camp. | 214 |

| They endeavour to conceal themselves from the Indians. They are discovered. A frightful encounter. Escape of Mahnewe. They pursue their journey in the night. Discovery of a river over which they cross. Come to a prairie. Approach a sandy desert. They provide themselves with ample provisions and set out over the cheerless waste. | 231 |

| Encampment in the sand. An island discovered. Singular appearance of rocks. Human skeletons found. Dreary prospects. They arrive at an oasis. They come to a lake. They discover a cavern in which they find mysterious implements. The cavern supposed to have been an ancient mine. Its remarkable features. | 240 |

| Recovery, and continuance of their journey. A joyous prospect. It changes to gloom. Discovered and followed by Indians. They finally escape. They wander on unconscious of their way. They meet with friendly Indians who give them cheering intelligence. They rest with them a few days. | 263 |

| They proceed on their journey. Jane bitten by a rattlesnake. Taken back to the village. It causes a violent fever to set in. She becomes delirious, but finally recovers. A war party returns having two white prisoners. Minawanda assists them to escape by a sound imitating that of a whippoorwill. They proceed on their flight unmolested. | 281 |

| They arrive at a stream of considerable magnitude over which they cross. They ride in the water to elude their pursuers. Jones and Cole give them information relative to their friends. The joyful reception of the news. Arrival at the base of the Sierra Nevada. Fear of crossing the mountains in the snow. They construct themselves winter quarters. | 298 |

| The cold increases. Abundant supplies of game. Jones and Cole tell some of their adventures in the gold regions. Comfortable condition of the children. Howe describes an adventure he experienced near Lake Superior. Whirlwind relates a circumstance that occurred to himself and Shognaw. | 309 |

| Departure of winter. Joy at the fact of knowing which way they were travelling. They reach the first ranges of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Discovery of gold. Discovery of singular ancient walls. An engraved slab of granite. They reach the foot of the Sierra in safety. They arrive at the residence of a Spanish Curate. They tarry awhile at his house. | 319 |

| Return to the family of Mr. Duncan. Lewis and his father succeed in getting back to camp. Cole and the chief reach the camp of the Arapahoes. They continue their course to Mr. Duncan's camp. Joy at the news they bring. They start again for the west. Thirty Arapahoes accompany them. They arrive at the Sierra Nevada. | 335 |

| The Curate becomes much attached to the Wanderers. Arrival of Mr. and Mrs. Duncan and family. Whirlwind demands Jane in marriage. Jane refuses, and the Indians take their departure. The curate gives an account of the discoveries he made of a singular road, city and pyramid. Prosperous condition of Mr. Duncan's family. The lapse of twelve years. Change of their condition. Conclusion. | 342 |

Chapter First.

Mr. Duncan's Discontentment. He starts for the West.

Near the Cold Springs, in Lafayette county, Missouri, lived Mr. Duncan, a sturdy woodsman, who emigrated thither with his father, while the Mississippi valley was still a wilderness, inhabited by wild beasts, or the still more savage Indians. His grandfather was an eastern man; but had bared his brawny arm on many a battle field, and had earned the right to as many broad acres as he chose to occupy. So, at least, he said, on leaving his eastern home, after peace had been declared, for the then verge of civilization—the Ohio. Here the soldier lived to see the wilderness blossom like the rose, and here he died, grieving that infirmity prevented his flying from the din of the sledge hammer, and the busy hum of mechanical life. Mr. Duncan's father, in the vigor of manhood, crossed the Mississippi, and settled at the Cold Springs, a region then isolated from civilization, as the Ohio was many years before the white man had planted his foot west of the Alleghanies. But he lived to see the silent echoes resound to the shrill whistle of the engine, and luxury with its still but mighty sway enervate the sons and daughters of the pioneers, until the one quailed at the sight of danger and the other dosed away the morning in kid slippers and curl-papers. Time claimed its own, and he died; and then his son, the Mr. Duncan of our narrative, began to turn his attention to the west, as his grandfather and his father had done before him. He had married a trapper's daughter, twenty years before, and his family consisted now of four sons and two daughters, an adopted son, and his brother-in-law, Andy Howe, who had spent his life in trapping, and trading with the Indians.

Lewis, his eldest son, nineteen years of age, was a man in strength, proportion and judgment, cool and prompt in emergencies, but on ordinary occasions caring for little else than his dogs, gun and uncle, whose superior knowledge of all that pertained to the forest, made him an oracle among the less experienced.

Edward, a boy of seventeen, passionate and headstrong, but generous and brave.

Jane, a girl of fifteen, the mother's supporter and helper, high spirited, energetic and courageous.

Martin, a pleasure-seeking, fun-loving, mischief-making lad of twelve years.

Anne, a timid child of ten years, who went by the soubriquet of the baby, by all except Lewis, who understood her better and called her the "fawn."

And last, but not least, the son of his adoption, Sidney Young, a noble young fellow of eighteen, whose parents dying left him to the care of Mr. Duncan, who had reared him with as tender care as that he bestowed upon his own children.

"Little Benny," or Benjamin more properly, we must not forget to introduce, a manly little fellow of eight, who could handle a bow and arrow, or hook and line, and propel a canoe with as much dexterity as a young Indian.

Such was the family of Mr. Duncan, when he resolved to penetrate the almost unknown region of the west. No hypochondriac papa or aristocratic mamma, can I introduce, but a hale, robust yeoman, who looks upon himself as in the prime of manhood, though nearly fifty years of age, and who boasts of never having consulted a physician or taken a drug. Mrs. Duncan wore her own glossy hair at forty-five, without a thread of silver among it, while her step was as elastic, and eye as bright, as in her girlhood. Her cheek was less rounded than it was formerly; but the matronly dignity and motherly kindness that characterized her, amply compensated for its loss. True types of man and womanhood were they, whom no dangers or vicissitude could daunt, no trials swerve from the path of right or inclination. Mr. Duncan well knew the undertaking he proposed was not one to be entered into thoughtlessly, or without due preparation. His habits from earliest infancy, of daily encountering the perils of border life, had taught him this, and with it taught him to love the boundless forest, the dashing waterfalls, and the deep stillness that retreated as refinement advanced.

"This is no place for me," he said, as he heard of some new innovation on old customs, as having taken place in the vicinity. But when a favorite haunt by a small stream was taken possession of, the trees felled, the brooklet dammed, and a factory set in motion, he for a moment seemed astounded, his eye wandered inquiringly from one member of his family to another, and finally rested upon Howe, as though expecting him to provide some remedy to stay the hand of innovation.

"It cannot be done, Duncan," said the trapper, comprehending the unspoken inquiry. "We are completely ensnared. Don't you see we are surrounded?"

"Had they only chosen some other spot for this last shop, or factory, or whatever else you call it, I would have tried to borne it. But there—no, it is too much."

"I have news that will be as unpleasant as the mill. The surveyors will pass near here in laying out a railroad to-morrow," said Lewis.

"I will never see it," said Mr. Duncan. "The world is wide enough for all. It may be for the best, that there should be a general revolution in the mode of manufactures and commerce, but I cannot appreciate it; I am willing to fall back to the forest to give place to those who can."

It must not be inferred that Mr. Duncan was an illiterate man. On the contrary, he was well posted on all the great events that transpired, and was conversant with many ancient and modern authors. He had carefully instilled into the minds of his children, a love of truth and virtue, for the contentment and nobleness it gave, and to despise vice as a thing too contaminating to indulge in by thought or practice. This love of forest life had become a part of his being, and he could no more content himself among the rapidly accumulating population that sprang up around him, than a Broadway dandy could in the wilderness. When driven from his accustomed fishing ground by the demolition of the forest, whose trees shaded the brooklet with their gigantic arms stretching from either side, interlacing and forming an arch above so compact as to render it impenetrable to the noonday sun, he wearied of his home, and sighed for the forest that was still in the west. Here he had been accustomed to resort to indulge in piscatory amusement; with his trusty rifle, full many a buck and even nobler game had fallen beneath his aim, as lured by the stillness they had come to quench their thirst at the brook, unconscious of the danger to which they were drawing near. He had long looked upon this haunt as peculiarly his own, not by the right of purchase, but by the possession, which he had actually enjoyed many years, until he considered it as an essential to his happiness.

For Mr. Duncan to resolve was to accomplish. Seconded by his family, his farm was sold, his affairs closed, and May 10, 1836, saw him properly fitted out for a plunge into the western wilds. Three emigrant wagons contained their movables, each drawn by three yoke of stout oxen. The first contained provisions and groceries, seeds and grain for planting, with apparatus for cooking. The second contained the household furniture that was indispensable, beneath which lay a quantity of boards, tent canvass, an extra set of wagon covers ready for use, twine, ropes &c., and was also to be the apartments of Mr. and Mrs. Duncan, and the girls. The third was loaded with agricultural and carpenter's tools, and contained the magazine, and was appropriated to the use of Andy Howe and the boys. Two saddle horses, five mules and three milch cows, with six as fierce hunting dogs as ever run down an antelope, constituted their live stock.

Thus prepared the family bade a glad adieu to their old home to find a more congenial one. I say a glad adieu, for certainly the older members of the family went voluntarily, and the younger ones, carried away by the hurry of preparation, had no time to think, and perhaps knew not of the dangers they would have to encounter. Youth is ever sanguine, and they had learned from the older ones to look upon the forest freed from the Indians as the Elysium of this world.

Onward to the west the tide of emigration is still rolling. Three centuries ago, the Massachusetts and Virginia colonies were the west to the European, three thousand miles over the Atlantic ocean. Brave was the soul, and stout the heart, that then dared it. A century later Pennsylvania and New York was the west; the tide was rolling on; still a century later its waves had swept over the Alleghanies, and went dashing down the Mississippi valley, anon dividing in thousands of rivulets, went winding and murmuring among the rugged hills and undulating plains. But even the burden of its murmurings was the west, still on to the west. And now where is the west? Not the Mississippi valley but the fastnesses of the Rocky Mountains. That part we find on charts as the "unknown." A valley situated among mountains, sunny and luxuriant as those of a poet's dream; but guarded by a people driven to desperation. This is now the west.

Chapter Second.

The Journey. Encampment. Buffalo hunt. Anne and Edward lost. They discover an old fort. Fight with a Wolf. Take refuge in a Tree. Rescued by Howe and Lewis. Return to the Camp.

Mr. Duncan chose the trader's route to Oregon as the one most likely to lead him to his desired haven. He was familiar with this route, having frequently made it some years before. To Andy Howe, every rock, tree, and river, was like the face of a friend so often had he passed them. Mrs. Duncan had no misgivings when they entered on the forest. She had so often heard the different scenes and places described as to recognize the locality through which they passed, and with perfect confidence in the forest craft of her brother and husband, she gave herself no trouble, save that of making her family as comfortable and pleasant as circumstances would allow.

No incident disturbed their journey, worthy of note, day after day as they easily moved along. It was not Mr. Duncan's policy to exhaust his teams at the outset by long weary marches; but like a skilful general, husband his strength, in case of emergencies. The road was smooth and level, being generally over large extended prairies.

The fifth day out they crossed the Kansas, when the country became more broken, and they saw the first buffalo on their route, which Lewis had the good luck to kill. With the aid of Howe it was cut up and the choicest parts brought to camp. Never was a supper enjoyed with more zest than that night. Delicious steaming beef stakes, wheat cakes, butter, cheese, new milk and tea, spread out on a snow white cloth, on their temporary table, to which they had converted two boards by nailing sheets across the back, and resting each end on a camp stool, made a feast worth travelling a few days into the wilderness to enjoy.

Their camp was pitched for the night on the mossy bank of a small stream, overshadowed by large cotton-woods through which the stars peered, and the new moon with its silvery crescent gleamed faintly as the shadows of evening closed around them.

After night fall the party was thrown into quite an excitement by the approach of figures which they supposed to be Indians, but which turned out to be a herd of deer feeding. Howe laughed heartily at the fright, for the Indians were to him as brothers. His father had been known and loved for many acts of kindness to them, and had been dignified as the great Medicine.1 Accompanying his father on his trapping excursions, while still a boy, he had spent many a day and night in their wigwams, partaking of their hospitality, contending with the young braves in their games, and very often joining them in their hunts among the mountains. Hostile and cruel they might be to others, but Howe was confident that he and those with him would meet with nothing but kindness at their hands.

Antelopes were now seen often, and sometimes numerous buffalo; but nothing of importance had been killed for two days. The morning of the twenty-fifth dawned clear and beautiful. Howe and Lewis brought the horses, and with Sidney mounted on a fleet mule, the three set out on a hunt. They had been tempted to this by a moving mass of life over the plain against the horizon, that resembled a grove of trees waving in the wind, to all but a practised eye; but which the hunters declared to be a herd of buffalo. Such a sight creates a strange emotion of grandeur, and there was not one of the party but felt his heart beat quicker at the sight. The herds were feeding, and were every where in constant motion. Clouds of dust rose from various parts of the bands, each the scene of some obstinate fight. Here and there a huge bull was rolling in the grass. There were eight or nine hundred buffaloes in the herd. Riding carelessly the hunters came within two hundred yards of them before their approach was discovered, when a wavering motion among them, as they started in a gallop for the hills, warned them to close in the pursuit. They were now gaining rapidly on them, and the interest of the chase became absorbingly intense.

A crowd of bulls brought up the rear, turning every few moments to face their pursuers, as if they had a mind to turn and fight, then dashed on again after the band. When at twenty yards distant the hunters broke with a sudden rush into the herd, the living mass giving away on all sides in their heedless career. They separated on entering, each one selecting his own game. The sharp crack of the rifle was heard, and when the smoke and dust, which for a moment blinded them, had cleared away, three fine cows were rolling in the sand. At that moment four fierce bulls charged on Sidney, goring his mustang in a frightful manner, and would probably have terminated his hunting career, had not the sudden shock of the onset thrown him some distance over his mustang's head. He was not much hurt, and before the buffaloes could attack him again, they were put to flight by Howe and Lewis. On examining the animal they soon saw he could not live, and shot him to end his suffering.

This they felt was an unlucky incident, and with saddened hearts turned their faces campward, which on reaching they found in consternation at the prolonged absence of Edward and Anne. They had gone out a few moments after the hunters, Edward to fish in the brook by which they had encamped, and Anne to gather curious plants and flowers, of which she was passionately fond. Mr. Duncan had been in search of them and came up as the hunters were dismounting.

"Have you found them?" was asked by every one in a moment, as he came up.

"No! but I found this, and this, about two miles down the stream," said he, holding up a fading wreath of wild flowers, and the skeleton of a fish that Edward had evidently cut away to bait his hook with.

"It is now nearly noon, and by the looks of that fish and those flowers, they have laid in the sun three hours. Give us a lunch, Mary, and now for the dogs, Lewis. No time is to be lost," said Howe.

"I fear the worst," said the father; "I saw signs of Indians."

"What were they?" quickly asked the Trapper.

"A raft on the opposite bank of the stream."

"They will bring them back, if they have taken them," said Howe, to which the surmise was not new, for it had occurred to him the moment he found the children were gone, but did not like to say so, lest he should raise an unnecessary alarm, But there was no outcry, no lamentation or dismay, though all was bustle and hurry. They knew it was time to act, not to spend their time in useless sorrow.

"Bring up two mules," said Howe, filling his pockets with bread and cheese, which he told Lewis to do also, "for," said he, "we may not come in to supper, certainly not unless we find them."

"I will go with you," said the father.

"And I," said Sidney, decidedly.

"No: a sufficient force is necessary here; you will take care of the camp, and if you hear the report of three guns in succession, bring the horses, which must be fed immediately," said the Trapper. "But, if we do not have to go a long distance, the mules will do."

"How will you know whether they are lost or have been carried off by savages," asked the mother, and though no coward, she shuddered and turned white as she asked the question.

"Easily enough known, when once on the ground. I know the red-skins as thoroughly as I do my rifle. Here Buff, here Lion," cried the Trapper, calling two noble bloodhounds to him—"Now, Mary," he continued, "give me a pair of Edward's and Anne's shoes, that they have worn." They were given him, and taking the hounds by the collar, he made them smell the shoes until they got the scent, then leading them to the bank of the stream pointed to them the tracks made in the morning.

"They have it! they have it!" shouted the family, as the hounds, with their noses to the ground, led off in fine style.

"Take Prince and Carl in the leash, Lewis, and fasten it to your saddle, then mount and away," cried the Trapper, throwing himself into his saddle, and giving the mule the spur, he was rapidly following in their wake.

Two hours passed, when the signals were given for the horses. Sidney saddled them, took a basket of provisions which Mrs. Duncan had put up with her usual thoughtfulness for others, and started in the direction from which the firing proceeded.

Edward and Anne, in the morning, had followed the course of the stream as far down as their father had traced them, Edward whiling away the time in drawing the finny tribes from their element, Anne in weaving in wreaths the gorgeous tinted wild flowers, sweet scented violets, and glossy green of the running pine. The children heeded not time, nor the distance they were placing between themselves and the camp, but wandered on. The wild birds were trilling the most delicious music, which burst on the ear enchantingly, and was the only sound that broke the solemn stillness that reigned around, save the soft gurgling of the water, as it glided over its pebbly bed. The forest was dense, the foliage above them shielding them from the sun, while the bank was smooth, mossy, and thickly studded with wild spring flowers, now in all the luxuriance of their natural loveliness. When they came to the bank of the stream where their father lost their track, they had their curiosity excited by a grove of willows on the opposite side, in the midst of which they could discern trunks of large trees piled up systematically, with a quantity of rubbish laying around. Thoughtlessly they resolved to cross over. The stream was about forty feet wide, but very shallow, not over three feet deep at any point, and in many places not more than two. But in order to get over, it was necessary to make a raft. Edward was at no loss how to begin; he had too often seen his father make temporary rafts to hesitate. Indeed, he looked upon it as a thing too small to be of much importance. Collecting two as large pieces of drift-wood as he could manage, he drew them to the bank, collected fallen limbs and brush wood, laying them across the drift wood, until he found, by walking upon it, that it would sustain their weight; then seating Anne in the centre, and with a long pole in his hand, placed himself beside her, and with the end of his pole pushing against the bank, launched his strange looking craft into the stream, their weight pressing against the water and its density resisting the pressure, kept the raft together. Slowly but securely they moved along; by pressing the pole against the bed of the river he propelled it until they finally reached in safety the opposite bank, where, drawing their raft a little out of water, that it might not float out of their reach into the stream, they prepared to explore the grove of willows that had drawn them thither. It was the sight of this raft across the stream that caused Mr. Duncan's alarm about the Indians.

On entering they found a large space cleared of its primitive growth, in the centre of about three acres, which was slightly overgrown with stunted shrubs, but the willows that formed the grove were of gigantic proportions, many of them three and a half, and some four feet in diameter.

In the centre of the clearing, was an immense fort, evidently built of the willows that had been felled to clear the space. The logs had been cut, straightened, and made to fit each other, with some sharp instrument, the corners being smoothly jointed, making the whole structure solid and impregnable to gun-shot or arrows. What had evidently been the door was torn away, and lay mouldering on the ground. The whole structure was apparently very old, and had been long deserted. The grass was growing within the enclosure, with weeds and briers, while the logs that formed it were covered with moss, and were crumbling to decay.

The children's curiosity was now blended with an absorbing interest, and Anne longed to follow Edward into the enclosure, but hesitated until he called out, "Only look! Anne! what can this be?" Then forgetting all her timidity, she hastened to see what he was dragging out of the rubbish, and as he held it up triumphantly for her inspection, she looked on with wonder and amazement.

"It is a huge plate cover; here is the handle," said Anne, turning it round with eagerness.

"Hardly that," said her brother; "this is two feet across, and is hardly the right thing for a plate cover; it is made of some metal."

"We will take it home," said Anne; "father and uncle Howe will know what it is, don't you think so?"

But Edward was not listening, and did not answer. He was digging down where he had found the thing, and came to a quantity of arrow heads, evidently made of the same material as the other, but of what it was he could not determine. Anne, with a strong stick in her hand, commenced searching, and soon came upon what they knew to be a stone mortar, for they had often seen them before.

Anne now began to complain of hunger, and Edward said he would give her a treat, Indian-fashion, to celebrate their arrival into, as he facetiously said, an Indian palace!

"But what can you give? We brought nothing with us; besides we have been out quite as long as we ought to, and had better return immediately."

"Oh, no; we have not. You know the camp will not move to-day, and I intend to make a day's work of it."

"We certainly must return; they will be alarmed about us. Come, let us go back."

"Not until we have the feast. Now keep quiet, Anne, until that is over, and then I will return with you."

"A funny feast it will be, composed of nothing."

"A finny feast it is to be, composed of fish. Now see how I will make a fire." And taking a flint he had found, he struck his pocket knife blade slant-wise against it, when it emitted sparks of fire in profusion, which, falling on a sort of dry wood, known to woodmen as "punk wood," set it on fire, which Edward soon blew into a blaze, and by feeding it judiciously a fire was soon crackling and consuming the fuel he had piled on it. In the mean time he had taken the fish he had caught, dressed and washed them at the stream, and laying them on the live coals until one side was done, turned them on the other by the aid of a long stick he had sharpened for the purpose, and when done he took them up on its point, and laid them steaming on a handful of leaves he had collected, and presented them to his sister.

Anne was sure she had never ate fish that tasted so delicious, a conclusion an excellent appetite helped her to arrive at. Edward was highly elated at his success, and laughed and joked over a dinner they enjoyed with a relish an epicure might covet. There is an old proverb about stolen waters being sweet; certainly their stolen ramble and impromptu dinner had a charm which completely blinded them to their duty to their parents, and even their own safety; for Edward proposed they should take a short ramble on the other side, where they were to try if they could discover some other ruins like those at the fort, and overruling the slight opposition Anne made, they gathered up the relics they had found, and moved on from the stream towards the deep luring shades, that were the same for many thousand miles, unbroken by the bound of civilization, but bewildering by its still mystic loveliness.

On they went, regardless of taking any notes or landmarks until the exhaustion of Anne warned Edward it was indeed time to return. Changing their course for one they mistook for that they had come, they plunged deeper and deeper at every step into the woods, without discovering their error, until they knew by the distance they had traversed they ought to have reached the old fort: but now it was no where to be seen, neither were there any signs of a river. They wandered to and fro, hoping every moment to make out the true direction to take, yet becoming more confused and bewildered at every step. Finally, Edward laid his ear to the ground, and listening, was sure he heard the faint murmuring of water. They hastened on towards the direction whence it proceeded, guided by the sound, until, oh joy! a stream burst upon their sight. Reaching its banks, Edward took his sister in his arms, plunged into the water, and was soon in safety on the opposite shore. He was now in a great quandary, for though he had gained what he supposed to be the bank he had left, without having lost time in building a raft, yet he knew if he missed his way he would not be able to gain the camp by sunset, for he saw by the long falling shadows that the sun was rapidly descending.

Anne was greatly terrified, and wept bitterly. "Do not grieve," said Edward, "they will of course miss, and come in search of us, if we do not get home soon. I am very certain we are very near the camp already."

"I am afraid we are lost," Anne replied, sobbing, "and if we are, we may never get back again!"

"Fie! Anne, don't be a coward, for I am very certain we shall, and that within the hour."

"How can you be certain? you do not even know which direction to take."

"Oh! yes I do: we came south, and of course must go north to get back again."

"If we only knew which way was north. No stars are to be seen to indicate it."

"Easily enough told,—come, we must not lose a moment, and as we go I will tell you an unmistakable sign."

"Oh! I am so weary I can go no farther," and again the child sobbed bitterly.

"Never mind, I am not tired, and can help you," and passing one arm around her he rendered her great assistance, and again they were hurrying on.

"You observe these trees," said he; "the bark on the side that faces the way we are going is quite smooth and even, while the opposite side is rough and the branches jagged. It is always so on forest trees, and a person may rely on this as a natural sign, when he has none other to go by, with perfect security. I have heard uncle Howe and father say that they have repeatedly lost themselves in the woods, but by following in one direction to a given point they could soon find themselves again."

"It is getting so very dark. Oh! Edward, what shall we do?"

"The first of every thing we must do is, to keep up our courage."

"Hist! what is that?—There it is again! Oh! Edward, let us run! There! there it is!" screamed the terrified girl.

Edward turned to the direction indicated, and a wolf was crouching with glaring eyes, ready to spring upon them. Edward's only weapon was a pocket-knife, one of those long two-edged bladed weapons, so common in the west; yet he did not despair, but placing Anne behind a large tree stationed himself before it, and with his knife open and a huge club he awaited the approach of the wolf.

It soon came. The wolf was lean and desperate, and with a terrific growl he bounded forward, but was met by the brave boy, who sprang aside as he came, and before the monster could recover his leap, Edward had dealt him several deep and deadly blows. Following up his advantage he sprang at the wolf with his knife, plunging it again and again in his side. The brute feeling he was being conquered, with a mighty effort turned on Edward with jaws extended, and would have done him harm had not Anne sprung forward with the circular metallic relic they had found at the fort, and placed it before her brother. This drew the attention of the enraged wolf on her; but before he could spring, Edward had felled him a second time to the ground, where he soon dispatched him.

It was now too dark to make their way farther, and Edward was forced to acknowledge the only hope of getting to camp that night, lay in their being found by his friends and carried back. Many a boy would have been discouraged, but Edward was not; though but seventeen he was athletic and brave, and felt that he was answerable for his sister's safety, whom he had led into this difficulty. "I can," said he to himself, "and I will; and where there is a will, there is a way."

He immediately kindled a fire, as he had done in the morning, in order to keep other wild beasts away, as well as to prepare some supper; then taking his line he soon had some fine fish, (for he was on the river bank he had last crossed,) which he broiled on the coals.

He could not shut his eyes to the terrible truth that they were in a very dangerous place; for, although they piled on fuel to frighten the beasts, yet they could hear the fierce growl of the wolf, the yell of the panther, and their stealthy tread, and see their eyes flash and glare in the surrounding gloom. The smell of the broiling fish seemed to have collected them, and sharpening their voracious appetites, made them desperate. To add to the difficulty of the children, the fuel was getting scarce around the fire, and they dared not go away from it, for it would be running into the very jaws of their terrible besiegers.

"We must get up into a tree, Anne," said Edward; "it is now our only hope."

"Then, Edward, there is no hope for me; I cannot climb, but you can. Save yourself while you can!"

"No, Anne, these monsters shall never have you while I live; never fear that. I know you cannot climb of yourself, but I can get you there. We must make a strong cord somehow. My fishing-line doubled twice will help, and here is a tree of leather-wood;2 this is fortunate, I can now succeed."

Collecting together all the fuel he could, he piled it on the fire, then taking his knife, stripped off the leather-wood bark, and tying it around Anne's waist, with the other end in his hand, he climbed up to the lowest limb, and then cautiously drew her up after him. Seating her securely on that limb, he climbed higher up, drawing her after him, until he reached a secure place, where he seated her, taking the precaution to fasten the cord that was around her to the tree. It was a large hemlock tree, and the limbs being very elastic, he proceeded to weave her a bed, that she might take some repose, for the poor child was wearied with fright and fatigue. Disengaging part of the cord from her, he bent together some limbs, and fastened them securely with the leather-wood string; he then broke some smaller branches, and interlaced them with the larger ones, until he had made a strong and quite comfortable bed. In this singular couch he placed Anne, where she soon fell asleep.

Gradually the fire died away, and nearer and nearer their dreadful enemies approached, until they came to the carcass of the dead wolf, which they tore into pieces and devoured, amidst frightful growlings and fightings. When nothing but the bare bones were left, they surrounded the tree in whose friendly branches the children had taken refuge, and kept up a continued howl through the night. Edward sat on a limb by his sister through the night, his knife ready for use, wondering if ever there was a night so long before. To him it seemed as though day would never dawn; and when he espied the first faint glimmer in the east, his heart bounded with gratitude that he had escaped the perils of the night. But would the wolves go away with the darkness? alas! they did not, but still prowled around, so that they did not dare to descend from their place of security.

Howe and Lewis had discovered the place where the children had ate their dinners at the fort, and had traced them until they came to the place where they first found they had missed their way. Here the hounds became perplexed in consequence of the children having doubled their track, and were unable to make out the path. After some delay it was again found, and followed to the river bank, which Howe hesitated to cross, as it was now quite dark; accordingly they encamped for the night. At dawn the next morning they crossed the river; the dogs were turned loose, and after a few moments they set off at a rapid pace in one direction; Howe and Lewis followed, and came in sight in time to see the dogs give battle to the wolves that were watching the children in the tree.

"Our rifles are needed there," said Howe, as his practised glance took in the combat, and drawing his eye across his trusty gun, a sharp crack was heard, and a wolf was felled to the ground. Again it was heard, and another bit the dust. Lewis had not been idle; he too had brought down two of them, and the remainder fled, with the hounds in pursuit.

The children's joy I will not attempt to describe, as they saw their rescuers approach, nor yet the agony of the parents, as the night wore away and the absent ones came not. Lewis took his sister in his arms, holding her on the saddle before him, and bore her back to camp. She would not relinquish the trophies found at the fort, which she had purchased so dearly, but carried them with her.

"My children, how could you wander away so, when you well knew the dangers of the woods?" said the father, when they were once more safely in the camp.

"It was not Anne's fault, father: do not blame her. I persuaded her to cross the river, and after leaving the old Indian fort, somehow we got turned around, and instead of recrossing the river, we went on and crossed over another stream," said Edward.

"Neither was it all Edward's fault," replied Anne; "I wanted to see what was in the Willow Grove, and when once there the woods were so shady and looked so cool and inviting——"

"Wolves and all, sister?" said Benny.

"The wolves were not there then; nothing but birds and squirrels, and such bright flowers and——"

"Were you not very much frightened, when you found you had lost yourselves?" asked Jane.

"Oh! yes; and when the wolf jumped at Edward, I thought we should never see any of you again."

"Where is your 'plate cover' you used so effectually," said Edward, "for I want you all to know that when the wolf was getting the better of me, Anne, usually so timid, suddenly became very courageous, and with this for a weapon turned the brute's attention on herself, and thus perhaps saved my life."

"Give me Anne's 'plate cover;'" said the father, "I am curious to examine what seems to have played so active a part in your adventure."

"A curious thing, very," said he, examining it closely. "Howe, did you ever come across anything like it in your wanderings? It is heavy, evidently of some kind of metal."

"Once, and once only. But its description would be a long story. Scrape away the rust, Duncan, and see if it is made of copper."

Mr. Duncan cut away a thick scale of corroded metal, then scraping it with a knife a pure copper plate was exposed to view.

"I thought so," said Howe. "It is a strange story, but I will tell you all I know of it."

Chapter Third.

Howe's Story of a singular piece of Metal.

In compliance with Mr. Duncan's wish Howe related the story of the singular piece of metal he had seen, similar to the one they had discovered.

"Some twenty years ago," said he, "my father and I carried on an extensive traffic with the Indians around Lake Superior for furs, often being gone a year on our expeditions, during which time we lived entirely with the Indians, when not in some inhabited region, by ourselves, which we often were, for a trapper penetrates and brings to light hidden resources, of which the Indian never dreams. During one of these excursions, we had been struck with the singular appearance of an old man, tottering with age, who belonged to the wigwam of the Indian chief with whose people we were trading. His thin hair, falling from the lower part of his head, was long, curling and white, leaving the top bald, and the scalp glossy. His beard was very heavy, parting on the upper lip, and combed smoothly and in waving masses, fell on his breast. His must have been a powerful, athletic frame in his manhood, for when I saw him he was over seven feet high, and though feeble and tottering, his frame was unbent, and his eye was blue and glittering, with a soul his waning life could not subdue. His features, as well as complexion, were totally unlike the rest of the tribe. His forehead was broad and high, his chin wide and prominent, his lips full, with a peculiar cast about them I had never seen on any other human being, giving the impression of nobleness mingled with a hopeless agony and sorrow. Such, at least, was the impression made on my mind, which time has never effaced. He was a strange old man, with such a form and face, and so unlike any other human being, that his very presence inspired the heart with feelings of reverence. The Indians have no beard. This fact impressed us with the idea that he was a white man; but when I compared him to the white race, he was as unlike them as the Indians. Singular in all his ways and manners, he seemed a being isolated from every human feeling or sympathy.

"My father said he had known this man for thirty-five years, and when he first saw him he was old, but then there was a woman with him, whom he tenderly cherished, and who, but a few years before, died of extreme old age. Otherwise he knew nothing more of them, as he never sought to learn farther than what the chief had told him. When he asked who they were, he was answered that they were all that was left of a nation their ancestors had conquered so many moons ago, and the chief caught a handful of sand, to designate the moons by the grains.

"I was more deeply impressed with the sight of this old man than I can describe; and what I heard of him only deepened the impression, until it haunted me continually. Who was he? How came he here? And where came he from when he came here? Who were his kindred, and of what race and nation was he? These were questions that I asked myself day after day, but was unable to answer them. I resolved to find out, and attempted to make friends with him as the most tangible way of succeeding. He was reserved and haughty, and I doubted my success; but I was agreeably surprised when he deigned to receive and converse with me, though at the same time he treated me with a degree of contempt by no means agreeable; yet it came from him with such a glance of pity in his eye as if he earnestly commiserated my inferiority, that I half forgave him at the moment. He conversed about everything save the one subject nearest my heart—himself. But on this point he was silent, and when, day after day, I entreated him to give me a history of himself, the thought seemed to call up such agonizing recollections as to make every renewal of the subject difficult for me and painful to him.

"Many months went by, but as yet I was no farther advanced than at first, on the one great subject of which I so longed to be familiar. I fancied of late the old man had become more taciturn and reserved than formerly, showing a disinclination to converse on any subject, and I could not avoid seeing his steps grow slower; he took less exercise than had been his custom, and I saw plainly he was passing away. Then I feared he would never relent; that death would come upon him and his history remain unknown.

"One evening, after I had in vain endeavored to gain access to the old man through the day, I wandered out and stood on a high cliff, against whose base the waves of the lake beat with a sullen roar; and looking far away over the turbulent surface of this prince of inland seas, was wondering if ever its waters would become tributary to the will of my race, or if, as now, the canoe of the Indian was all the vessel that should breast its rugged waves. The place where I stood was a sort of table, or level rock, the highest peak of the cliff, rising in a cone-like shape, some thirty feet above. Below it was irregular, and the path to the place where I stood tortuous, difficult, and dangerous; but when once there, one of the grandest views on the whole lake was presented. I had not been there long, when, hearing a footstep approach, and thinking it a dangerous place to be caught in if it should be an unfriendly Indian, I caught hold of some shrubs growing in the crevices of the rock, and silently let myself down a few feet below the table, whose overhanging rock I knew would protect me from observation, and where I could have a full view of the rock by looking through the shrubs, by whose friendly aid I had descended to my retreat.

"I had scarcely secreted myself when, to my astonishment, the old man advanced slowly up the path, his labored breathing showing how painful to him was the exertion. Fearing no harm I was soon by his side, begging him to lean on me and to allow me to assist him. He looked down on me with a peculiar expression, akin to that I should express should Benny here insist on going out buffalo hunting, and which annoyed me exceedingly, of which he, however, took no notice.

"After standing with folded arms, looking intently over the water towards the far south, he turned to me and said:

"'It shall be even so. Come hither, son of a degenerate race, and learn the secrets of the past. Long before your race knew this continent existed, my people were in the vigor and glory of national prosperity. From the extreme north, where the icebergs never yield to the sun, through the variations of temperature to the barren rocks in the farthest south, were ours, all, from ocean to ocean!'

"He paused for a moment, as if endeavoring to recall some half-forgotten facts, then proceeded in a sorrowful tone.

"'But troubles came. Our kings had fostered two different races on their soil, who were at first but a handful, and who had at two different periods been driven by winds on our shore. The first that were thus cast on our hospitality were partially civilized in their ways, and though far removed above the brute, were not like us; so wide was the difference that an intermarriage with them would have been punished with death. They were human, and therefore protected, their insignificance being their greatest friend; for my ancestors no more thought of laying tribute on them, even when they came to number themselves by thousands, than you would on an inferior race. The other race were savages of the worst character; more savage than beasts of prey, and so they multiplied and became strong, and even preyed upon themselves. Thus our forests became filled with beasts in the shape of man, and our districts with an imbecile race. Centuries rolled onward, and the savages multiplied and grew audacious. They even penetrated our cities and preyed upon us, while we, paralyzed by such acts of ingratitude, were weakened by what should have made us strong. We passively beheld a loathsome reptile, that might at first have been crushed in an hour, thrive to become a monster to devour us.

"At length, but, alas! too late, we awoke to the danger of our situation. We drove them from our cities to the mountains, but ere we could take active measures to prevent a recurrence of these outrages, the other race we had fostered started up like a swarm of locusts, and declaring themselves our equals, demanded to be recognized as such. So preposterous was this demand, that we were at first disposed to treat it only as the suggestion of a disordered intellect, but, of course, could never comply with so degrading a request, for nothing we could do could invest them with strength, intellect, or form like ours. Soon after our refusal they too grew audacious, and forming a league with the savages, set up a king whom they said should make laws and govern the land. Then commenced a terrible war of extermination. This whole continent was drenched with blood. We fought to save our homes and our country, they to gain the supremacy. It was not a battle of a year or of half a century. As many years as I have seen, the torrent was never stayed, and when an advantage was gained, on either side, life was never spared. By slow degrees, they possessed themselves of fortress after fortress, and city after city: we, the while, growing weaker, they stronger, until we were compelled to take refuge in the cities of our king. These cities were built and walled with granite, and we supposed them to be impregnable; and laying as they did in the centre of the continent, and in proximity to one another, we hoped yet to withstand them. But, alas! we had another foe to encounter. Gaunt hunger and famine came with their ghastly forms and bony arms, blighting the strong and the brave. But it could not make traitors or cowards of us, and dying we hurled defiance at our foes. The walls of our cities unmanned, were scaled—the gates thrown open; and our streets filled with the murderers whom we had reared to exterminate us. A few were found alive, and these few were saved by the victors that the arts and sciences might not die. From these I am descended; but though we refused to transmit this knowledge to them, they treated us with great care, hoping that after a lapse of time we would amalgamate with them. But we were made of sterner stuff than that. We could see our race and nation blotted from existence, but not degraded. After the lapse of many centuries we were forgotten in the struggles of a half civilized race and the savages for supremacy, and my people dying out year by year, are all gone save myself, the last of the rightful owners of this continent."

As the old man concluded, his head fell forward on his breast and he remained silent and motionless so long, that I feared the recalling of the past had been too great a task for him, and going up to him, I laid my hand on his. Throwing it aside, he said: "Young man, I have told you of the past, and now there is a page of the future I will unfold to you. Your race shall possess the heritage of my ancestors. And as the savages exterminated us, so shall you them. But, beware, you too are fostering a serpent that at last will sting, and perhaps devour you." "The arts and sciences of your race speak of them; were they like ours," I said, anxious to learn more of this strange people: "Yours," he replied with more warmth than he had exhibited, "are not unlike ours, though far inferior to them. Your race boasts of discoveries and inventions! ah! boy, you are but bringing to light arts long lost, but in perfection centuries of centuries before your people ever knew of this land."

"Is there any proof of this? is there nothing remaining to give ocular demonstration of these facts?" I asked.

"A few," said he. "Nothing very satisfactory, but what there is, you shall see."

So saying, he let himself down to the same spot where I had, in hiding from him, I following. On removing a few pieces of loose rock the door leading to a cavern was visible, which we entered. It was a large cave running back into a lofty arched room, as far as I could see in the surrounding gloom. The old man took a couple of torches from a pile that lay on a shelving rock close by the door, lighted them, and giving one to me bade me follow. The farther we went the wider and loftier was the cave, until I began to wonder where it would end. At this moment he paused before a stone tablet of immense proportions, raised about three feet from the floor, the ends resting on blocks of granite. All over its surface was hieroglyphics engraved in characters I had never seen before, though I have often found similar ones since.

"Here," said he, "are recorded the heroic deeds of our race while fighting to save our firesides from a rapacious foe. Every character is a history in itself. Yet your race know it not; but still boast of sciences you do not possess."

"No," said I, "we cannot decypher these characters, we have never claimed to have done so; but if you can give me a key to them, tell me how we may make an alphabet to it, we may still be able to do so."

"It would be useless for me to do so," said he, with his old manner of superiority, "your intellect could not grasp it; you would not understand me."

"Try me," said I, eagerly, "try me and see."

But he only beckoned me away, then advancing a few paces took from a recess in the rock, a heavy flagon not unlike our own in shape, and placing it in my hand, informed me that their vessels for drinking were like that, varied in shape and size according to taste. Holding it to the light, I was astonished to find it was made of gold, fine and pure as any I had ever seen. There were instruments of silver, also, which he assured me, would carry sound many miles, and others of glass and silver to shorten objects to the sight at an equal distance. And these, said he, handing me some curious shaped vases are like the material of which we made many of our ornaments to our dwelling. They appeared to be made of glass, yet they were elastic. He said the material was imperishable. There were helmets, shields, curiously shaped weapons, chisels, and many things I knew not the use of, all made of copper, among the rest a shield precisely like the one you have, Anne."

"Did you bring nothing away? uncle," asked the children.

"No: when he had shown me all he desired me to see, he led me back to the mouth of the cave, and motioning me out, followed, closing the opening he had made and ascending to the table where we stood before.

"Then I begged the old man to tell me more of his race, to unfold the curtain that hung like a pall between them and us. He shook his head sadly, and standing with his face towards the south, communing with himself awhile, turned to me, and said: 'You believe in a God, good and evil, rewards and punishments?'"

I answered in the affirmative.

"Would you hesitate to break an oath taken in the name of the God in which you believe?" he asked.

"I would not dare to commit such a crime," I answered.

"Then, swear," said he, "that what I have told and shown you, you will never reveal to human being by word or sign."

"Oh, no, you cannot mean that; leave us some clue to your lost race," I entreated.

"Yes, swear," repeated he imperiously.

"No: oh! no, I cannot. Though for your sake," I said, "I will be silent any reasonable number of years you shall dictate to me."

He gazed sternly on me for a few moments, then said.

"Let it be so. When I have passed away you are absolved from your oath."

"You will teach me to read the recorded past," I said inquiringly, "and tell me of the arts now lost, at some future day!"

"It is too late, my days are spent, he said; then rousing himself, he exclaimed, in a voice that still rings in my ears: 'Son of a degenerate race, go over this whole continent and there trace the history of my people. Our monuments are there, and on them are chiseled our deeds, and though we moulder in the dust, they can never die; they are imperishable. Go where the summer never ends, where the trees blossom, still laden with fruit, and there we once were mighty as these forests, and numerous as the drops in this lake; there read of our glory—but not of our shame—that was never chiseled in our monumental pillars; it is here, (placing his hand on his heart) and with me must die. Go, (said he, waving with his hand towards the path that ascended the table) go, and leave the last of a mighty race, to die alone. It is not fitting you should be here: Go? I am called.'"

I obeyed him reluctantly, but I never saw him again.

Chapter Fourth.

Their journey continued. Finding a Prairie. Encamping for the Night. Singular incident. A Mirage on the Prairie. Alarm in the Camp. The Prairie discovered to be on fire. Flight to the Sand Hills. Their final escape. Search for water. Finding a stream. Encampment.

The next day the camp was struck and packed; the oxen, rested and invigorated by roving over and cropping the rich grasses that grew in luxuriance along the banks of the river by which they had encamped, moved with a brisk step along their shady track, while the voices of the drivers sounded musically, reverberating through the stillness of the forest. Towards noon they came to one of those singularly interesting geological features of the west, a Prairie. This was something entirely new to the younger children, who had never been far from the place where they were born, and it very naturally surprised them to see such a boundless extent of territory, without a house, barn, or fence of any kind—nothing but a waving mass of coarse rank grass.

"Oh! father," cried little Benny, as the vast prairie burst on his sight, "see what a great big farm somebody has got! But where does he live? I don't see any house."

"And the fences, apple, peach, and pear trees?" said Anne.

"It is not a farm; it's a big pasture kept on purpose to feed buffaloes and deer in," said Martin.

"You are all wrong," retorted Lewis, "for though buffaloes and deer do feed on the prairie, it is not kept for them alone; it has always been so—trees will not grow on it."

"You, too, are wrong, Lewis," said Mr. Duncan. "Though it is true trees will not grow on the prairie now, yet it was not always so. Geologists tell us that the vegetable growth, some thousand years ago was, in many respects, different from what now covers the solid surface of our earth. Changes of temperature and constituents of soil are going on from age to age, and correspondent changes take place in the vegetable kingdom. Over large tracks, once green with ferns, stately trees have succeeded, followed in their turn, in the course of ages, by grosser and other herbaceous plants."

"According to that theory, after a regular course of time has elapsed, these rank grasses will be succeeded by some ether form of vegetable growth," remarked Sidney.

"Certainly," replied Mr. Duncan. "When one class of trees has exhausted the soil of appropriate pabulum, and filled it with an excrement which, in time, it came to loathe, another of a different class sprang up in its place, luxuriated on the excrement and decay of its predecessor, and in time has given way to a successor destined to the same ultimate fate. Thus, one after another, the stately tribes of the forest have arisen, flourished, and fell, until the soil has become exhausted of the proper food for trees, and become fitted for the growth of herbaceous plants."

After pitching their camp that night, the children in rambling round it, came to one of those landmarks with which the prairies are so thickly studded along the different trails—a grave. Saddened at the thought of any one dying in that lonely place, they gathered around it, wondering if the hand of affection soothed his last, his darkest hour, if tears bedewed his resting place, or whether he died unmourned, unwept, hurried with unseemly haste beneath the sod, and only remembered by a mother, wife or sister, who a thousand miles away was wondering why the absent one, or tidings of him, came not.

The children assembled thus in a group, Howe drew thither also, to ascertain what they had found.

"A grave," said he, "ah! poor fellow, he sleeps well in his prairie bed."

"Here is a name cut in this bit of board at the head, uncle, but it is done so badly I can't make it out," said Martin.

"Let me try," said Howe; "it is plain enough, sure."

"JOSHUA CRANE

"DIED

"OCT. 20, 1834, AGED 27."

"Now, children, would you like to see Mr. Joshua?" said Howe.

"Why, uncle," said they, "how can you make light of such a thing?"

"I am in earnest; for, from various indications about it, I am of opinion that he is a curious fellow."

Anne, with a tear in her eye, cast a reproachful look towards her uncle, while the rest were too much surprised to do anything but stare at him in wonder.

"Bring me a crowbar and shovel, Edward. I find I must convince these little doubters that I am really in my senses."

"Oh, uncle!" said Jane, "you could not have the heart to disturb the dead!"

"Bless me, child, who thinks of disturbing the dead; I am only going to show you what a funny fellow Joshua is. Now," said he, raising the crowbar, "if Joshua is sleeping here, this iron cannot reach him; but, if as I suspect, why, then, you see"—and down went the crowbar in the loose earth. "Now give me the shovel," said he, and commenced removing the dirt, the children looking on in astonishment. He soon brought to the surface, and rolled on the grass a barrel of brandy. The broad lonely prairie fairly resounded to the shouts and laughter of the children, as they danced about the barrel; Howe standing by enjoying a deep ha! ha! peculiarly his own.

"What a curiosity, Joshua is! Who would have thought of finding such a thing there?"

"It is a rare thing, I own," said Howe, "yet occasionally resorted to when oxen have given out, or died. Sometimes wagons have been over-loaded, and then unable to make their way over the rough roads, some heavy article is taken and buried with all the signs of a grave about it, to prevent its being disturbed and stolen, as in the present instance. Probably the owner will be along here for it, or sell it to some one who will come for it in course of the summer."

"Will you leave it here, or bury it again?"

"The prize is mine; I shall carry it along with me," said Howe.

"That would not be right," rejoined Martin. "It is another man's property."

"Which he forfeited by false pretences. No, children, whatever found without an owner in these wilds, falls to the finder by right," said the Trapper.

"I think the children are right," said Mrs. Duncan, who had come hither at the sound of their mirth.

"Suppose the owner is dead and never comes for it," said Howe.

"It in no wise alters the case. It is better that it never finds an owner than possess ourselves of what has purposely been hid from us."

"Such notions are right and proper for a settlement, but for a place like this, it is carrying it to too nice a point."

"The rights of others should be as sacred to us in one place as another," replied Mrs. Duncan.

"Suppose somebody had trapped beaver and foxes in some particular locality, would that make the animals that were uncaught in that locality his own?"

"Certainly not. The case is different; as the beaver uncaught never were his, he had no claim on them. But if he caught a hundred beaver and cured the skins, and secreted them in some place until he chose to sell them, it would be decidedly dishonest for any one to take them away as their own, because they had found the place in which they were hidden."

"I believe you are right, Mary. Joshua shall be reinterred," said Howe, rolling the barrel in its old bed, and proceeding to cover it.

"Mother is always right," cried the children, as they wended their way back to camp.

Early the next morning, as they were moving over the prairie, a beautiful vision burst on their sight. It was a mirage of the prairie. As the sun rose in all the splendor of an unclouded sky in the east, the objects in the west became suddenly elongated vertically, the long rank grass stretching to an amazing altitude, while its various hues of green were reflected with vivid accuracy. As the emigrants approached the optical illusion, it gradually contracted laterally above and below towards the centre, at the same time rapidly receded towards the horizon, until it assumed its original aspect. As the sun approached the meridian, the atmosphere become so intensely warm that Mr. Duncan thought it prudent to rest until it began to descend, to which they all joyfully assented, as their oxen appeared to be almost overcome with the heat. They had been a day and a half on the prairie, and as the water they brought with them would not last them longer than the next morning, they were anxious to make the distance to the hills, which were looming faintly before them in the west, where they were sure of finding an abundant supply. Accordingly, the oxen were turned loose, the horses and mules being picketed, and all resigned themselves to the disagreeable necessity of an encampment in a burning noonday sun on the prairie, with not even a shrub to shelter them from its rays. But there was no help for it, the oxen could not proceed with the wagons, and they were obliged to wait until the heat of the day was over.

Towards evening, a light breeze began to stir the heated air, and borne on its wings, came also a disagreeable odor caught only at long intervals, but which served to put Howe and Mr. Duncan on their guard.

"There is a fire on the prairie, away at the north," said Howe, "and there is not a moment to be lost, if we would save our baggage, cattle, or even our lives!"

"It is true, there is fire, and now I see the smoke away yonder, looking like a thin mist against the sky; should it blow this way, our only refuge is the Sand Hills, that I know lay yonder towards the forest," said Mr. Duncan, looking intently towards the point whence the odor came.

"Saddle the horses and mules, boys," said Mr. Duncan, "and place Mary and the children on them. Benny, you must ride with your mother, I am afraid to trust you alone on a mule chased by fire. You must sit still, my boy, and keep up your courage; the Sand Hills are yonder, not more than three miles over the plain; you see them, Mary," he continued, "but do not mind the trail; keep your horses headed direct for them, and ride for your lives. I do not think there will be any danger for any of us; but it is better to make all ready for the worst."

"But, suppose you, with the oxen, wagons, and cows, are surrounded with fire," said Mrs. Duncan.

"We will do our best in the emergency. But I hope to gain the hills in safety. Perhaps the wind will shift and blow the fire in another direction. We must hope for the best, doing everything in our power for our safety. Now go; give the horses and mules a loose rein."

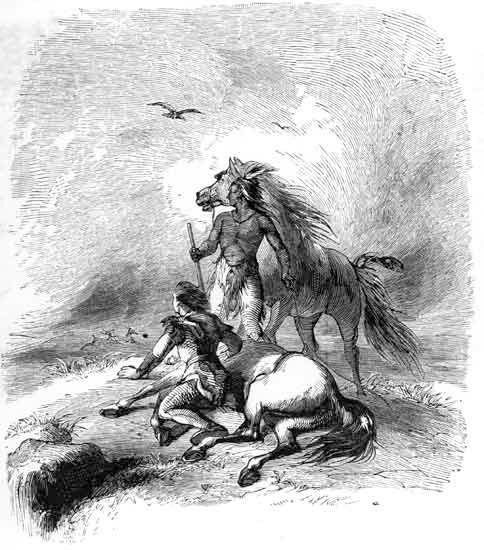

And away over the plain the cavalcade went, followed by the wagon as fast as the oxen could travel, but the progress they made was slow in comparison to that of the fire. On it came, and on went the cattle, goaded by the drivers at first, but at last catching sight of the heavy, rolling wave of fire that was sweeping towards them, they started into a gallop, frightened and seeming to comprehend the danger that menaced them. Mr. Duncan saw his wife and children gain the Sand Hills in safety, and then the smoke and half consumed grass filled the air, hiding the rescued from view as the burning wave swept toward them, maddening the oxen and making the stout hearts of the pioneers quail, as the burning fragments eddying through the air, fell thick and fast among them. Prairie dogs, in droves went howling past, wolves and panthers laying their bodies close to the ground in their rapid leaps, heeded not each other, and even an antelope joined in the flight unmolested, from their common foe. Innumerable prairie fowls filled the air with their cries; but, above every other sound arose the roar and crackling of the scorching billowy mass, as on, still on it came, now rising until its seething flame seemed to touch the sky, then falling a moment only to rise the next still higher.

A prairie on fire is a sublime spectacle, which those who have had the good fortune to see, in a place of safety, will not soon forget. But a horrible ordeal it is for those who are overtaken by the raging flame; for, if the grass is dry, with a slight breeze to fan the flame, it travels with the speed of a whirlwind.

Mr. Duncan could not abandon his noble beasts in the extremity, for he knew if left to themselves, unaccustomed to the ground, they would lose themselves, and ensure their destruction; but, in keeping by their sides, encouraging them by his presence and urging them on, he still hoped to save them, although half blinded with smoke and the hot air that surrounded them. Howe had charge of one of the teams, and Sidney the other, who, following the example of Mr. Duncan, stood their ground bravely, resolving to share the fate of their cattle.

Mrs. Duncan and the children, from their hill of refuge, saw with terror the fearful and unequal race on the plain below, until they were entirely enveloped in smoke, and then their suspense was harrowing till a puff of wind lifted the smoky cloud, which it occasionally would, giving them for an instant a glimpse of their friends, as on they came towards them in their headlong career. But, as nearer, still nearer came the flames, the cloud became too dense to be lifted by the wind, and all was one circling, eddying wave, hiding every object from view. A few moments of suspense, during which no words were spoken, and then bursting through the cloud came their noble oxen, their tongues dry and blackened and hanging from their mouths, their hair scorched from their sides, and the wagon covers on fire, while the drivers feeling they were safe sank on the sand, half way up the hill from exhaustion.

Mrs. Duncan, and the children, were soon by the wagons, tearing off the covers, and by so doing, saved the contents from burning. Then pouring water over and down the throats of their exhausted oxen, they were soon able to breathe freely. In the meantime, by Mrs. Duncan's direction, Anne had taken a basin of water and bathed the faces and hands of the drivers, so that they were, though quite exhausted, very comfortable. The fire rolled past them without reaching them further, and finally, after having spent itself died away, leaving the broad prairie that was at noon so heavily covered with verdure, a blackened plain.

"This is a pretty fix for us to get in, Duncan," said Howe, as the fire rolling away, left them clear of smoke, and gave them a full view of their position. "Here we are," he continued, "every drop of water spent, without a blade of grass around us, begrimed with soot and smoke, looking worse than any Indians I ever saw."

"We ought to be thankful," said Mr. Duncan, "that no lives are lost. We have escaped better than we had reason to hope, placed as we were."

"To be sure we have escaped ourselves, but see what a pitiable plight our oxen are in. They will not be able to draw another load in a week, at least; and what are we to do in the meantime?"

"I declare, uncle, I think you have the horrors; for whoever before saw you at a loss for an expedient under any circumstances?" said Jane, with a merry twinkle in her eye; for this was a peculiar phase in her uncle's character, to hold up to others the worst side of any circumstance, while at the same time he was taking active measures to remedy it. So in this instance: for he had already made arrangements to reconnoitre the forest, that lay west of the Sand Hills, not over two and a half miles distant. Accordingly, mounting one horse, with Lewis on the other, they galloped over the plain, and striking the forest at the nearest point, they found it dry, destitute of grass, and totally unfit for a camping ground. Taking a circuit in a southerly direction, where the surface seemed more broken, they found they were on higher ground, and as they rode on, the thick undergrowth all the while growing more dense, encouraged them to proceed; for which they were rewarded by striking a small brooklet of pure water, whose banks were lined with rich grasses, sheltered by tall trees that grew on either side. Here he resolved the camp should be pitched, and lighting a fire to mark the place, they galloped back to the Sand Hills. To remove the heavy wagons was no easy task, as the oxen were only able to walk without a burthen.

There were two pairs of mules and one of horses, and these being hitched to one of the wagons, were taken to the place designated by the stream, and then brought back for another until all the wagons were on the ground, which the last reached about ten at night. In the meantime, Mrs. Duncan had walked thither with the children, Mr. Duncan, with the other boys, driving the oxen a little way at a time, and at last reached the camp ground as the last wagon came up.

Chapter Fifth.

Preparing a Supper. Heavy Storm. The Place of their Encampment. Straggling Indians seen. Apprehensions of an Attack. Preparations of defense. Approach of the Crows. A Fight. The Camp Attacked. Capture of Five in the Camp. The Pursuit. Recovery of some of the Captured. The pursuit Continued. Tabagauches meet the Crows, and defeat them. They are discovered. Encampment.

Tired and sleepy, our travelers provided themselves with supper, having pitched their tents, and laid down to court sleep the great restorer for body and mind. The sky was cloudless betokening a clear night; and presuming on this they had not re-covered their wagons, intending to leave it until they had slept off their fatigue. But in this, even Howe had something to learn. People under such circumstances should presume on nothing, but make everything sure, for at one hour they are not certain that the next will find them secure. It did not them, for they had slumbered scarcely three hours, when the whistling winds and creaking of their tent poles aroused them from their slumbers. Springing from their beds they were almost blinded by the lightnings' glare, as flash followed flash, in quick succession, each accompanied by a deafening peal of thunder that reverberated portentously through the forest. Mr. Duncan hastened into the open air. The sky was overcast with fleecy clouds, while from the northwest came slowly up a dark heavy cloud stretching over the whole of that part of the sky. As higher and higher it rose, louder grew the thunder, and more vivid the lightning, the wind sweeping round in angry blasts until it seemed as if every element in nature was in commotion.