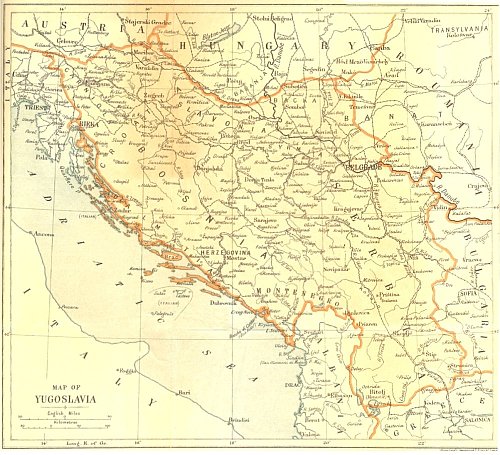

Title: The Birth of Yugoslavia, Volume 2

Author: Henry Baerlein

Release date: March 8, 2008 [eBook #24781]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jason Isbell, Irma Spehar and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BY

HENRY BAERLEIN

VOLUME II

LONDON

LEONARD PARSONS

DEVONSHIRE STREET

First Published 1922

[All Rights Reserved]

Leonard Parsons Ltd.

New foes for old—Roumanian activities—The Italian frame of mind—Sensitiveness with respect to their army—An unfortunate naval affair—What was happening at Pola—The story of the "Viribus Unitis"—How the Italians landed at Pola—The sea-faring Yugoslavs—Who set a standard that was too high—An electrical atmosphere and no precautions—Italians' mildness on the Isle of Vis—Their truculence at Korčula—And on Hvar—How they were received at Zadar—What they did there—Pretty doings at Krk—Unhappy Pola—What Istria endured—The famous town of Rieka—The drama begins—The I.N.C.—The Croats' blunder—Melodrama—Farce—Parole d'honneur—The population of the town—The tale continues on the northern isles—Rab is completely captured—Avanti Savoia!—The Entente at Rieka—A candid Frenchman—Economic considerations—The turncoat Mayor—His fervour—Three pleasant places—Italy is led astray by Sonnino—The state of the Chamber—The state of the country—A fountain in the sand—Those who held back from the Pact of Rome—Gathering winds—Why the Italians claimed Dalmatia—Consequences of the Treaty of London—Italian hopes in Montenegro—What had lately been the fate of the Austrians there—And of the natives—Now Nikita is deposed—The Assembly which deposed him—Nikita's sorrow for the good old days—The state of Bosnia—Radić and his peasants—Those who will not move with the times—The Yugoslav political parties—The Slovene question—The sentiments of Triest—Magnanimity in the Banat—Temešvar in transition—A sort of war in Carinthia—Yugoslavia begins to put her house in order—The problem of Agrarian Reform—Frenzy at Rieka—Admiral Millo explains the situation—His misguided subordinates at Šibenik—The Italians want to take no risks—Yet they are incredibly nonchalant—One of their victims—Seven hundred others—A glimpse of the official robberies—And harshness and bribery—The Italians in Dalmatia before and during the War—Consequent suspicion of this minority—Allied censure of the Italian navy—Nevertheless the tyranny continues—A[8] visit to some of the islands—Which the Italians tried to obtain before, but not during, the War—Our welcome to Jelša—Proceedings at Starigrad—The affairs of Hvar—Four men of Komiža—The women of Biševo—On the way to Blato—What the Major said—The protest of an Italian journalist—Interesting delegates—A digression on Sir Arthur Evans—The dupes of Nikita in Montenegro—Italian endeavours—Various British commentators—The murder of Miletić—D'Annunzio comes to Rieka—The great invasion of Trogir—The Succession States and their minorities—Obligations imposed on them because of Roumanian Antisemitism.

NEW FOES FOR OLD

With the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian army, the Serbs and Croats and Slovenes saw that one other obstacle to their long-hoped-for union had vanished. The dream of centuries was now a little nearer towards fulfilment. But many obstacles remained. There would presumably be opposition on the part of the Italian and Roumanian Governments, for it was too much to hope that these would waive the treaties they had wrung from the Entente, and would consent to have their boundaries regulated by the wishes of the people living in disputed lands. Some individual Italians and Roumanians might even be less reasonable than their Governments. If Austria and Hungary were in too great a chaos to have any attitude as nations, there would be doubtless local opposition to the Yugoslavs. And as soon as the Magyars had found their feet they would be sure to bombard the Entente with protestations, setting forth that subject nationalities were intended by the Creator to be subject nationalities. A large pamphlet, The Hungarian Nation, was issued at Buda-Pest in February 1920. It displayed a very touching solicitude for the Croats, whom the Serbs would be sure to tyrannize most horribly. If only Croatia would remain in the Hungarian State, says Mr. A. Kovács, Ministerial Councillor in the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, then the Magyars would instantly bestow on her both Bosnia (which belonged to the Empire as a whole) and Dalmatia (which belonged to Austria). That is the worst of being a Ministerial Statistical Councillor. Another gentleman, Professor Dr. Fodor, has the bright idea that "the race is the multitude of individuals who inhabit one uniform region." ... Passing to Yugoslavia's[9] domestic obstacles, it was impossible to think that all the Serbs and Croats and Slovenes would forthwith subscribe to the Declaration of Corfu and become excellent Yugoslavs. Some would be honestly unable to throw off what centuries had done to them, and realize that if they had been made so different from their brothers, they were brothers still. For ten days there was a partly domestic, partly foreign obstacle, but as the King of Montenegro did not take his courage in both hands and descend on the shores of that country with an Italian army, he lost his chance for ever.

ROUMANIAN ACTIVITIES

There was indeed far less trouble from the Roumanian than from the Italian side. On October 29, 1918, one could say that all military power in the Banat was at an end. The Hungarian army took what food it wanted and made off, leaving everywhere, in barracks and in villages, guns, rifles, ammunition. Vainly did the officers attempt to keep their men together. And scenes like this were witnessed all over the Banat. Then suddenly, on Sunday, November 3, the Roumanians, that is the Roumanians living in the country, made attacks on many villages, and the Roumanians of Transylvania acted in a similar fashion. With the Hungarian equipment and with weapons of their own they started out to terrorize. Among their targets were the village notaries, in whom was vested the administrative authority. At Old Moldava, on the Danube, they decapitated the notary, a man called Kungel, and threw his head into the river. At a village near Anina they buried the notary except for his head, which they proceeded to kick until he died. Nor did they spare the notaries of Roumanian origin, which made it seem as if this outbreak of lawlessness—directed from who knows where—had the high political end of making the country appear to the Entente in such a desperate condition that an army must be introduced, and as the Serbs were thought to be a long way off, with the railways and the roads before them ruined by the Austrians, it looked as if Roumania's army was the only one available. On the Monday and the Tuesday these Roumanian freebooters,[10] who had all risen on the same day in regions extending over hundreds of square kilometres, started plundering the large estates. Near Bela Crkva, on the property of Count Bissingen-Nippenburg, a German, they did damage to the sum of eight and a half million crowns. At the monastery of Mešica, near Veršac, the Roumanians of a neighbouring village devastated the archimandrate's large library, sacked the chapel and smashed his bee-hives, so that they were not impelled by poverty and hunger. In the meantime there had been formed at Veršac a National Roumanian Military Council. The placard, printed of course in Roumanian, is dated Veršac, November 4, and is addressed to "The Roumanian Officers and Soldiers born in the Banat," and announces that they have formed the National Council. It is a Council, we are told, in which one can have every confidence; moreover, it is prepared to co-operate in every way with a view to maintaining order în lăuntra și în afară (both internal and external). The subjoined names of the committee are numerous; they range from Lieut.-Colonel Gavriil Mihailov and Major Petru Jucu downwards to a dozen privates. The archimandrate, who fortunately happened to be at his house in Veršac, begged his friend Captain Singler of the gendarmerie to take some steps. About twenty Hungarian officers undertook to go, with a machine gun, to the monastery on November 7; at eleven on the previous night Mihailov ordered the captain to come to see him; he wanted to know by whom this expedition had been authorized. The captain answered that Mešica was in his district, and that he had no animus against Roumanians but only against plunderers. After his arrival at Mešica the trouble was brought to an end. Nor was it long before the Serbian troops, riding up through their own country at a rate which no one had foreseen, crossed the Danube and occupied the Banat, in conjunction with the French. The rapidity of this advance astounded the Roumanians; they gaped like Lavengro when he wondered how the stones ever came to Stonehenge.... When the Serbian commandant at Veršac invited these enterprising Roumanian officers to an interview he was asked by one of them, Major Iricu, whether or not they were to be interned.[11] "What made you print that placard?" asked the commandant; and they replied that their object had been to preserve order. They had not imagined, so they said, that the Serbs would come so quickly. "I will be glad," said the commandant, "if you will not do this kind of thing any more."

THE ITALIAN FRAME OF MIND

Italy was not in a good humour. She was well aware that in the countries of her Allies there was a marked tendency to underestimate her overwhelming triumphs of the last days of the War. Perhaps those exploits would have been more difficult if Austria's army had not suffered a deterioration, but still one does not take 300,000 prisoners every day. Some faithful foreigners were praising Italy—and she deserved it—for having persevered at all after Caporetto. That disaster had been greatly due to filling certain regiments with several thousand munition workers who had taken part in a revolt at Turin, and then concentrating these regiments in the Caporetto salient, which was the most vulnerable sector in the eastern Italian front. How much of the disaster was due to the Vatican will perhaps never be known. But as for the uneducated, easily impressed peasants of the army, it was wonderful that all, except the second army and a small part of the third, retreated with such discipline in view of what they had been brooding on before the day of Caporetto. They had such vague ideas what they were fighting for, and if the Socialists kept saying that the English paid their masters to continue with the War—how were they to know what was the truth? The British regiments, who were received not merely with cigars and cigarettes and flowers and with little palm crosses which their trustful little weavers had blessed, but also with showers of stones as they passed through Italian villages in 1917, must have sometimes understood and pardoned. Then the troops were in distress about their relatives, for things were more and more expensive, and where would it end? In face of these discouragements it was most admirable that the army and the nation rallied and reconstituted their morale.[12]

SENSITIVENESS WITH RESPECT TO THEIR ARMY

Of course one should not generalize regarding nations, except in vague or very guarded terms; but possibly it would not be unjust to say that the Italians, apart from those of northern provinces and of Sardinia, have too much imagination to make first-class soldiers. And they are too sensitive, as you could see in an Italian military hospital. Their task was also not a trifling one—to stand for all those months in territory so forbidding. And there would have been more sympathy with the Italians in the autumn of 1918 if they had not had such very crushing triumphs when the War was practically over. What was the condition of the Austrian army? About October 15, in one section of the front—35 kilometres separating the extreme points from one another—the following incidents occurred: the Army Command at St. Vitto issued an order to the officers invariably to carry a revolver, since the men were now attacking them; a Magyar regiment revolted and marched away, under the command of a Second-Lieutenant whom they had elected; at Stino di Livenza, while the officers were having their evening meal, two hand grenades were thrown into the mess by soldiers; at Codroipo a regiment revolted, attacked the officers' mess, and wounded several of the people there, including the general in command. Such was the Austrian army in those days; and it was only human if comparisons were made—not making any allowances for Italy's economic difficulties, her coal, her social and her religious difficulties—but merely bald comparisons were made between these wholesale victories against the Austrians as they were in the autumn of 1918 and the scantier successes of the previous years. In September 1916 when the eighth or ninth Italian offensive had pierced the Austrian front and the Italians reached a place called Provachina, Marshal Boroević had only one reserve division. The heavy artillery was withdrawn, the light artillery was packed up, the company commanders having orders to retire in the night. Only a few rapid-fire batteries were left with a view to deceiving the enemy. But as the Italians appeared to the Austrians to have no heart to come on—there may have been other[13] reasons—the artillery was unpacked and the Austrians returned to their old front. In May 1917, between Monte Gabriele and Doberdo, Boroević had no reserve battalion; his troops, in full marching kit, had to defend the whole front: they were able to do so by proceeding now to this sector and now to that. No army is immune from serious mistakes—"We won in 1871," said Bismarck, "although we made very many mistakes, because the French made even more"—but the Yugoslavs in the Austrian army could not forget such incidents as that connected with the name of Professor Pivko. This gentleman, who is now living at Maribor, was made the subject of a book, Der Verrath bei Carzano ("The Treachery near Carzano"), which was published by the Austrian General Staff. His battalion commander was a certain Lieut.-Colonel Vidale, who was a first cousin of the C.O., General Vidale; and when an orderly overheard Pivko, who is a Slovene, and several Czech officers, discussing a plan which would open the front to the Italians, he ran all the way to the General's headquarters and gave the information. The General telephoned to his cousin, who said that the allegation was absurd and that Pivko was one of his best officers. The orderly was therefore thrown into prison, and Pivko, having turned off the electricity from the barbed wires and arranged matters with a Bosnian regiment, made his way to the Italians. The suggestion is that, owing to the lie of the land and the weak Austrian forces, it was possible for the Italians to reach Trent; anyhow the Austrians were amazed when they ceased to advance and the German regiment which was in Trent did not have to come out to defend it. Everyone in the Austrian army recognized that the Italian artillery was pre-eminent and that the officers were most gallant, especially in the early part of the War, when one would frequently find an officer lying dead with no men near him. But such episodes as the above-mentioned—it would be possible, but wearisome, to describe others—could not but have some effect on the opposing army, and would be recalled when the Italians sang their final panegyric. The reasons for the Austrian débâcle on the Piave are as follows: when the Allied troops had reached Rann, Susegana, Ponte di Piave and Montiena, the Austrian High Command[14] decided on October 24 to throw against them the 36th Croat division, the 21st Czech, the 44th Slovene, a German division and the 12th Croat Regiment of Uhlans. However, the 16th and 116th Croat, the 30th Regiment of Czech Landwehr and the 71st Slovene Landwehr Regiment declared that they would not fight against the French and English, and, instead of advancing, retired. The 78th Croat Regiment, as well as three other Czech Regiments, abandoned the front, after having made a similar declaration. At the same time the 96th and 135th Croat Regiments, in agreement with the Czech detachments, made a breach for the Italians on the left wing at Stino di Livenza, while Slav marching formations revolted at Udine. The Austro-Hungarian troops consequently had to retreat.... No one expects of the Italian army, as a whole, that it will be on a level with the best, but when the British officers who were with the Serbs on the Salonica front compare their reminiscences with those of the British officers on the Italian front, it is improbable that garlands will be strewn for the Italians. Towards the end of October a plan was adopted by the British and Italian staffs for capturing the island of Papadopoli in the Piave; this island, about three miles in length, formed the outpost line of the Austrian defences. On the night of October 23-24 an attack was to be made by the 2nd H.A.C., while three companies of the 1st Royal Welsh Fusiliers were to act as reserve. This operation is most vividly described by the Senior Chaplain of the 7th Division, the Rev. E. C. Crosse, D.S.O., M.C.;[1] and he says nothing as to what occurred on that part of the island which was to be seized by the Italians. Well, nothing had occurred, for the Italians did not get across and when the water rose they said they could do nothing on that night. These are the words of Mr. Crosse's footnote: "The obvious question, 'What was going to be done with the farther half of the island?' we have purposely left undiscussed here. This half was outside the area of the 7th Division, and as such it falls outside the scope of this work for the time being. The subsequent capture of the whole island (on the following night) by the 7th Division was not part of the original plan." Afterwards, when a [15]crossing was made to the mainland, the left flank was unsupported, as the Italians did not cross the river, and thus the 23rd Division had its flank exposed. A belief is entertained that the Italian cavalry is one of the best in the world; evidently it is not the best, for on that Piave front, where thousands of Italian cavalry were available, the only ones who put in their appearance early in the battle were three hundred very war-stained Northampton Yeomanry.

"The record of the Italian troops in the field renders unnecessary an assertion of their courage," says Mr. Anthony Dell;[2] "for reckless bravery in assault none surpasses them." But when you have said that you have nearly summed up their military virtues, for discipline is not their strong suit, and they have little sense of responsibility. On the other hand, we must remember their admirable patience, but the great mass of the people have not attained the level of Christianity; they are savage both in heart and mind, with no outlook wider than that of the family. It is the Italian proletariat which is judged by the Yugoslavs, whose otherwise acute discernment has been warped by the unhappy circumstances of the time. Indifferent to the fact that he himself is a compound of physical energy and oriental mysticism, the Yugoslav has become inclined to contemplate merely the physical side of the Italian, and for the most part that portion of it which has to do with war. The Italian long-sightedness and prudence and business capacity are ignored save in so far as they delayed the country's entrance into the Great War. The sensitiveness and artistic attributes of the Italians, who gaze with aching hearts upon the glories of a sunset, are but rarely felt by Serbs, who gather brushwood for the fire that is to roast their sucking-pig and who sit down to watch the operation, haply with their backs turned to the sunset. The Yugoslav, especially the Serb, is a man from the Middle Ages brought suddenly into the twentieth century. With his heroic heart and his wonderful strength he fails to understand those people who, on account of one reason or another, have no passion for war. And as the military deeds of the Italians have had such effect upon [16]the minds of the Yugoslavs, we have alluded to them at a greater length than would otherwise have been profitable. The Yugoslavs despise the Italians. Also the Italians, who concern themselves with diplomacy, are conscious that their keen wits and their long training in the wiles of the civilized world, their old traditions and their prestige give them a considerable advantage over the Yugoslav diplomat, so that this kind of Italian despises the Yugoslav. He knows very well that the French or British statesmen do not, amid the smoke of after-dinner cigars, esteem his case by the same standard as that which they apply to the case which the ordinary Yugoslav diplomat presents to them in office hours. As for the wider Italian circles, one must fear that the old hatred of Germany, because the Germans seemed to despise them, will henceforward colour the sentiments with which they regard the Yugoslavs. It is a state of things between these neighbours which other people cannot but view with apprehension.

AN UNFORTUNATE NAVAL AFFAIR

There was in Yugoslav naval circles no very cordial feeling for the Italians. The Austrian dreadnought, Viribus Unitis, was torpedoed in a most ingenious fashion by two resolute officers, Lieutenant Raffaele Paolucci, a doctor, and Major Raffaele Rossetti. In October 1917 they independently invented a very small and light compressed-air motor which could be used to propel a mine into an enemy harbour. They submitted their schemes to the Naval Inventions Board, were given an opportunity of meeting, and after three months had brought their invention into a practical form. The naval authorities, however, refused to allow them to go on any expedition till they both were skilled long-distance swimmers. Six months had thus to be dedicated entirely to swimming. At the end of that time they were supplied with a motor-boat and two bombs of a suitable size for blowing up large airships. To these bombs were fixed the small motors by means of which they were to be propelled into the port of Pola, while the two men, swimming by their side, would control and guide them. Just after[17] nightfall on October 31, 1918, the raiders arrived outside Pola.

Were they aware that anything had happened in the Austro-Hungarian navy? On October 26 there appeared in the Hrvatski List of Pola a summons to the Yugoslavs, made by the Executive Committee of Zagreb, which had been elected on the 23rd. This notice in the newspaper recommended the formation of local committees, and asked the Yugoslavs in the meantime to eschew all violence. When Rear-Admiral (then Captain) Methodius Koch—whose mother was an Englishwoman—read this at noon he thought it was high time to do something. Koch had always been one of the most patriotically Slovene officers of the Austrian navy. On various occasions during the War he had attempted to hand over his ships to the Italians, and when some other Austrian commander signalled to ask him why he was cruising so near to the Italian coast he invariably answered, "I have my orders." He found it, however, impossible to give himself up, as the Italians whom he sighted, no matter how numerous they were, would never allow him to come within signalling range. Koch had frequently spoken to his Slovene sailors, preparing them for the day of liberation, and he was naturally very popular among them. Let us not forget that such an officer, true to his own people, was in constant peril of being shot.

WHAT WAS HAPPENING AT POLA

On the afternoon of that same day, October 26th, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with its army and navy, was collapsing, Admiral Horthy, an energetic, honest, if not brilliant Magyar, the Commander of the Fleet at Pola, called to his flag-ship, the Viribus Unitis, one officer representing each nationality of the Empire. Koch was there on behalf of the Slovenes. The Admiral announced that a wholesale mutiny had been planned for November 1st, during which the ships' treasuries would be robbed, and he asked these officers to collaborate with him in preventing it. Koch, at the Admiral's request, wrote out a speech that he would deliver to the Slovenes, and this document, with one or two notes in[18] the Admiral's writing, is in Koch's possession. "If you will not listen to your Admirals, then," so ran the speech, "you should listen to our national leaders." He addressed himself to the men, of course in the Slovene language, as a fellow-countryman. He begged them to keep quiet. He deprecated all plundering, firstly in order that their good name should not be sullied, and also pointing out that the neighbouring population was overwhelmingly Slovene. Out of 45,000 men only 2000 could leave by rail; he therefore asked them all to stay peacefully at Pola. Meanwhile the local committee had been formed; Koch was, secretly, a member of it, and on the 28th, Rear-Admiral Cicoli, a kindly old gentleman who was port-commandant, advised Koch to join it as liaison-officer. It was on the 28th at eight in the morning that the officers who had been selected to calm the different nationalities started to go round the fleet. That officer who spoke to the Germans declared that one must not abandon hopes of victory, and that anyhow the War would soon be over. Count Thun, who discoursed to the Czechs, was ill-advised enough to make the Deity, their Kaiser and their oath the main subjects of his remarks, so that he was more than once in great danger of being thrown overboard. Koch went first of all to the Viribus Unitis, but the mutiny had begun; a bugle was sounded for a general assembly; it was ignored, and the crew let it be known that they were weary of the old game, which consisted of the officers egging on one nation against another. This mutiny had not yet spread to the remaining ships, and on them the speeches were delivered. At the National Assembly that evening Koch was chosen as chief of National Defence; he thereupon went to Cicoli and formally asked to be allowed to join the committee. When Vienna refused its assent, Koch resigned his commission. By this time all discipline had gone by the board, no one thought of such a thing as office work and, amid the chaos, sailors' councils appeared, with which Koch had to treat. The situation was made no easier by the presence of large numbers of Germans, Magyars and Italians, of whom the latter also formed a National Council. On the 30th, Koch, as chief of National Defence, asked Admirals Cicoli and Horthy[19] to come at 9 p.m. to the Admiralty, with a view to the transference of the military power. At 7.30, in the municipal building, there was a joint meeting of the Yugoslav and the Italian National Councils, and so many speeches were made that the Admirals had to be asked to postpone their appearance for two hours; and at eleven o'clock, with the street well guarded against a possible outbreak on the part of any loyal troops, the whole Yugoslav committee, accompanied by one member of the Italian committee, went to the Admiralty. Horthy had gone home, but Cicoli and his whole staff were waiting. The old gentleman was informed that he no longer had any power in his hands; he was asked to give up his post to Koch, and this he was prepared to do. "It is not so hard for me now," he said, "as I have meanwhile received a telegram from His Majesty, ordering me," and at this point he produced the paper, "to give up Pola to the Yugoslavs." The affair had apparently been settled between nine and eleven o'clock. Cicoli was ready to sign the protocol, but out of courtesy to a chivalrous old man this was left undone; after all there were witnesses enough.

During the night of October 30th-31st, a radiogram, destined for President Wilson, was composed. "Together with the Czechs, the Slovaks and the Poles, and in understanding," it said, "with the Italians, we have taken over the fleet and Pola, the war-harbour, and the forts." It asked for the dispatch of representatives of such Entente States as were disinterested in the local national question. But now a telegram was received from Zagreb, announcing that Dr. Ante Tresić-Pavičić, of the chief National Council, would be at Pola at 8 a.m. and that, pending his arrival, no wireless was to be sent out. Dr. Tresić-Pavičić,[3] poet and deputy for the lower Dalmatian islands, had always been, in spite of his indifferent health, one of the most strenuous fighters for Yugoslavia. Two years of the War he spent in an Austrian prison, but on his release he managed to travel up and down Croatia and Dalmatia, inciting the Yugoslav sailors to revolt; many of them had already read a speech by this silver-tongued deputy in the Reichsrath, a speech of which [20]the reading and circulation had been forbidden as a crime of high treason. About 9 a.m. of the 31st there was a meeting, on board the Viribus Unitis, between Tresić-Pavičić and Koch. There was a brief ceremony, the leader of the Sailors' Council handing over the vessel to the deputy, as representing the National Council of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Admiral Horthy, in his cabin, likewise drew up a procès-verbal to the same effect, saying that he was authorized to do this by the Emperor, and he supported his statement by the production of a wireless message. Koch urged on the doctor the necessity of sending the above-mentioned wireless to Wilson. "The news of this great event," says Tresić-Pavičić in an article in the Balkan Review (May 1919), "was dispatched to all the Powers by wireless." But unfortunately he seems, whether on his own responsibility or that of Zagreb, to have prevented Koch from sending it on that day. Captain Janko de Vuković Podkapelski was then placed in command of the fleet, though the Sailors' Council at first declined to accept him. He was at heart a patriot, but had taken no active part in Yugoslav propaganda and, unluckily for himself, he had been compelled to accompany Count Tisza in his recent ill-starred tour of Bosnia, when the Magyar leader made a last attempt to browbeat the local Slavs. Yet, as no other high officer was available, Koch told the Sailors' Council that they simply must acknowledge Vuković, and at 4 p.m. he took over the command, the Yugoslav flag being hoisted on all the vessels simultaneously, to the accompaniment of the Croatian national anthem and the firing of salutes.

THE STORY OF THE "VIRIBUS UNITIS"

Three hours previously to this a torpedo-boat, with Paolucci and Rossetti on board, had sailed from Venice; and at ten o'clock in the evening, as Paolucci tells us,[4] he and his companion, after a certain amount of embracing, handshaking, saluting and loyal exclamations, plunged into the water. The first obstacle was a wooden pier upon which sentries were marching to and fro; this [21]was safely passed by means of two hats shaped like bottles, which Paolucci and Rossetti now put on. The bombs were submerged, and thus the sentry saw nothing but a couple of bottles being tossed about by the waves. A row of wooden beams, bearing a thin electric wire, had then to be negotiated, and the last obstacle consisted of half a dozen steel nets which had laboriously to be disconnected from the cables which held them. It was now nearly six o'clock; the two men cautiously approached the Viribus Unitis and fixed one of their bombs just below the water-line, underneath the ladder conducting to the deck. Paolucci simply records, without comment, that the ship was illuminated; perhaps he and his friend were too tired to make the obvious deduction that the hourly-expected end of the War had really arrived. A number of officers from other ships had remained on the Viribus Unitis after the previous evening's ceremony; but the look-out, seeing the Italians in the water, must have thought it was eccentric of them to come swimming out at this hour to join in the festivities. A motor-launch soon picked them up and they were brought on board the flag-ship. "Viva l'Italia!" they shouted, for they were proud of dying for their country. "Viva l'Italia!" replied some of the crew to this pair of allied officers. When they were conducted to Captain Vuković they told him that his vessel would in a short time be blown up. The order was given to abandon ship, and Paolucci and his friend relate[5] that when they asked the captain if they might also try to save themselves he shook them both by the hand, saying that they were brave men and that they deserved to live. So they plunged into the water and swam rapidly away, but a few minutes later they were picked up by a launch and taken back, the captain having suddenly begun to suspect, they said, that the story of the bomb was untrue. They were again made to walk up the ladder, under which lay the explosives. It was then 6.28. The ladder was crowded with sailors who were also returning to their ship. "Run, run for your lives," shouted Paolucci. At last his foot touched the deck, and then he and Rossetti ran as fast as they could to the stern. Hardly had they got there [22]than a terrific explosion rent the air, and a column of water shot three hundred feet straight up into the sky. Paolucci and Rossetti were again in the water, and looking back they saw a man scramble up the side of the vessel, which had now turned completely over, with her keel uppermost. There on the keel stood this man, with folded arms. It was Vuković, who had insisted on going down with his ship. About fifty other men were killed.

When Koch came out of his house, feeling that there must be no more delay in sending the radiogram to President Wilson, a young Italian Socialist ran up to him in the street and told him of the fate of the flagship. As the news spread everyone thought it must be the work of some Austrian officers. It was feared that they would explode the arsenal, and that would have meant the destruction of the whole town. Amid the uproar and chaos, Koch had placards distributed, saying that the Viribus Unitis had been torpedoed by two Italians, who were in custody. And then the wireless was sent to Paris.

The two officers were taken to the Admiralty and then placed on the dreadnought Prince Eugene, it being rumoured that the Italians of Pola intended to rescue them. Subsequently Koch and other officers, together with Dr. Stanić, President of the Italian National Council, went out to see the prisoners. Stanić was left alone with them for as long as he wished. And when Koch saw them—he did not then shake hands—and asked if they knew what they had done, "I know it," replied Rossetti rather arrogantly. Paolucci's demeanour was more modest.

"I was your friend all through the War," said Koch, "and now you sink our ships. I can only assume that you were ignorant of what had taken place."

They said that that was so.

"But if you had known," said the Admiral to Rossetti, "would you have done this?"

"Yes," he answered. "I am an officer. I had my orders to blow up the ship and I would have obeyed them."

Koch had undertaken that if it turned out that they were unaware of the ship's transference to the Yugoslavs he would kiss them both. He did so, and allowed them to communicate with Italy by wireless.

Never, says Koch, will the unpleasant taste of those[23] kisses leave his mouth. The men were officers; their words could not be doubted. But as they must surely have been in Venice for at least a day or two before October 31, it seems extraordinary that they did not hear, via Triest, of what the Emperor Charles was doing with his navy. If only they had perfected their invention and learned to swim a trifle sooner there would be no shadow cast on their achievement, but the Yugoslavs—who had never seen any sort of Italian naval attack on Pola during the War—could not be blamed for thinking that the disappearance of their Viribus Unitis would be viewed with equanimity by the Italians.... With regard to the other vessels, it was arranged in Paris that they should proceed, under the white flag, to Corfu with Yugoslav commanders; but this was found impossible, as they were undermanned. Part of the fleet arrived at Kotor and was placed at the disposal of the commander of the Yugoslav detachment of the Allied forces which had come from Macedonia. A serious episode occurred at Pola, where on November 5 an Italian squadron arrived and demanded the surrender of the ships. The Yugoslav commander succeeded in sending by wireless a strong protest to Paris against this barefaced violation of the agreement. The Italian commander, Admiral Cagni, likewise sent a protest, but Clemenceau upheld the Yugoslavs. They were absolutely masters of the ex-Austro-Hungarian fleet; it rested solely with them either to sink it or hand it over to the Allies in good condition. The Yugoslavs did not sink the fleet, because they wished to show their loyalty to, and confidence in, the justice of the Allies. They never suspected at that time that the ships would not be shared at least equally between themselves and the Italians. But in December 1919 the Supreme Council in Paris allotted to the Yugoslavs twelve disarmed torpedo-boats for policing and patrolling their coasts.

HOW THE ITALIANS LANDED AT POLA

Admiral Cagni was invited by the Yugoslavs to enter the harbour of Pola. But for two and a half days he hesitated outside and heavily bombarded the hill-fortress of[24] Barbarica, which had been abandoned. At last he made up his mind to risk a landing. The Italian girls of Pola, dressed in white, came down in a procession to the port; their arms were full of flowers for the Italian sailors. And the first men who disembarked were buried in flowers and kissed and kissed before the girls perceived that, by a prudent Italian arrangement, this advance guard consisted of men of the Czecho-Slovak Legion. The first care of the Italians at Pola was not to ascertain the whereabouts of the munition depots; they made for the naval museum, where trophies from the battle of Vis in 1866 were preserved. These they removed, as well as whatever took their fancy at the Arsenal. Among their booty was a silver dinner service which it had been customary to use on occasions of Imperial visits. An Italian officer appeared on the Radetzky. Very roughly he asked an officer who he was. "I am the commander," said this first-lieutenant. "No! no!" said the other, "I am that." But the Italians for the most part avoided going on board the ships.... Admiral Cagni himself was very ill at ease, but grew noticeably more confident as he observed the utter demoralization of Pola. His correspondence likewise underwent the appropriate changes. While Koch was in command of 45,000 men, Cagni wrote to "His Excellency the most illustrious Signor Ammiraglio"; when the numbers were reduced to 20,000 the style of address was "Illustrious Signor Ammiraglio"; when they fell to 10,000 it became "Al Signor Ammiraglio"; when only 5000 remained a letter began with the word "Ammiraglio!" and when the last man had left Pola and Koch was alone, Cagni sent word through his adjutant that he knew no Admiral Koch but merely a Signor Koch.

THE SEA-FARING YUGOSLAVS

Talking of numbers, one may mention that the Yugoslavs formed about 65 per cent. of the Austro-Hungarian navy, as one would naturally expect from the sea-faring population of Dalmatia and Istria. In the technical branches of the service only about 40 per cent. were Yugoslavs, for a preference was given to Germans and[25] Magyars. Out of 116 chief engineers only two were Yugoslavs. Serbo-Croat was an obligatory language; but German, as in the army, was the language of command. Thus one sees that, in spite of not being favoured, the Yugoslavs of the Adriatic, who are natural sailors, constituted more than half the personnel of the navy. "These Slav people," writes Mr. Hilaire Belloc,[6] who took the trouble to go to the Adriatic with a view to solving the local problems, "these Slav people have only tentatively approached the sea. Its traffic was never native to them." If he had continued a little way down the coast he would have seen many and many a neat little house whose owners are retired sea-captains. "They are not mariners," says Mr. Belloc. If he had made a small excursion into history he would have learned that Venice—since it was to her own advantage—made an exception of Dalmatia's shipping industry, and while she was placing obstacles along the roads that a Dalmatian might wish to take, allowed the time-honoured industries of the sea to be developed. Such fine sailors were the Dalmatians that Benedetto Pesaro, the Venetian Admiral against the Turks in the fifteenth century, deplored the fact that his galleys were not fully manned by them, instead of those "Lombardi" whom he despised. "They are," says Mr. John Leyland,[7] the naval authority—they are "pre-eminently a maritime race. The circumstances of their geography, and in a chief degree the wonderful configuration of their coast-line, with its sheltered waters and admirable anchorages, made them sea-farers.... The proud Venetians knew them as pirates and marauders long ago." And "there has never been a better seaman," adds Mr. Leyland, "than the pirate turned trader." In 1780 the island of Brač had forty vessels, Lussin a hundred, and Kotor, which in the second half of the eighteenth century quadrupled her mercantile marine, had a much larger fleet than either of them. The best-known dockyards were those at Korčula and Trogir, while the great Overseas Sailing Ship Navigation Company at Peljesac (Sabioncello) occupied an important position in the world of trade. The company's fleet of [26]large sailing vessels was of native construction; both crews and captains were natives of the country, so that it was in every way the best representative of the Dalmatian mercantile marine of the period. When the Treaty of Vienna in 1815 gave Venice, Istria and the Eastern Adriatic to the Habsburgs the vessels plying in those waters were very largely Slav. And with the substitution of steam the Dalmatians are still holding their own, with this difference, that the ships are now built, even as they are manned, not by nobles and the wealthy bourgeoisie, but by men who come from modest sea-faring or peasant families. In the Austrian mercantile marine German capital formed 47·82 per cent., Italian capital 19·37 per cent. and Slav capital 31·80 per cent. One of these Dalmatian Slavs, Mihanović, going out in poverty to the Argentine, has followed with such success the shipbuilding of his ancestors that he is now among the chief millionaires of Buenos Aires. With regard to fishing, there are along the Istrian and Dalmatian coast more than 5000 small vessels which give employment to 19,000 fishermen, of whom only 1000 are citizens of Italy. But Mr. Belloc says that these Slav people have only tentatively approached the sea, that its traffic was never native to them, and that they are not mariners. It is marvellous that you can be paid for writing that sort of stuff.... By Mr. Belloc's side is the Marchese Donghi, who in the Fortnightly Review of June 1922 says: "It is superfluous to add that everything which has to do with navigation [in Dalmatia] is entirely in the hands of the Italians." But I think it is superfluous to contradict a gentleman who ingenuously believes that Dalmatia is largely Italian because on our maps we have hitherto used Italian place-names. Will he say that the population of Praha is not Czech because on our maps that capital is commonly called Prague? It pleases the Marchese to be facetious about what he describes as "that queer thing called the Srba Hrvata i Slovenca Kralji (Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes)"; he should have said "Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca." He says that in Serbia "no industry is possible," whereas in one single town, Lescovac, there are no less than eleven textile besides other factories. He says that[27] one-third of the population of Dalmatia is Italian, and "almost exclusively the nobility and the upper bourgeoisie." I suppose that is why more than 700 of Dalmatia's leading citizens were deported by the Italians after the Great War. He says many other nonsensical things, and sums it all up by telling us of the "bewildered incomprehension" of the Adriatic problem!

WHO SET A STANDARD THAT WAS TOO HIGH

Whether rightly or wrongly, the Yugoslavs had formed their opinion of the Italian sailors, an opinion which dated from the time of Tegetthoff and had not undergone much modification by the incidents of this War. They remembered what had happened when they cruised outside Italian ports; they knew very probably that the British had on more than one occasion to break through the boom outside Taranto harbour, and they may have read[8] of the experience of some French ladies who came to the Albanian coast on the Città di Bari towards the end of 1915 with 2000 kilos of milk, clothing and medical supplies for the Serbian children who had struggled across the mountains. These ladies write that after the torpedoing of the Brindisi their own crew ran up and down without appearing to see them; the crew had life-belts, those of the ladies were taken away. Ultimately they succeeded in having themselves put ashore, and the Città di Bari fled in the night without landing the stores. And in Albania, the ladies say, one witnessed the "stoic endurance of the noble Serbian race, of which every day brought us more examples. In that procession of ghosts and of the dying there was no imploring look, there was no hand stretched out to beg." ... The Yugoslavs may have known what happened to Lieutenant (now Captain) Binnos de Pombara of the French navy. This officer, in command of the Fourche, had been escorting the Città di Messina and, observing that she was torpedoed, had sent to her, perhaps a little imprudently, all his life-boats and belts. A few minutes later, when he was himself torpedoed, the Italians did not see him; anyhow they made for the shore. De Pombara encouraged his men [28]by causing them to sing the Marseillaise and so forth; they were in the water, clinging to the wreckage, for several hours, until another boat came past. The next day at Brindisi, when he met the captain of the Città di Messina, this gentleman once more did not see him; but the French Government, although de Pombara was a very young man, created him an officer of the Legion of Honour.

AN ELECTRICAL ATMOSPHERE AND NO PRECAUTIONS

There was thus a certain amount of tension existing between the military and naval services of the Yugoslavs and those of Italy. Other Yugoslavs were apprehensive as to whether the Italians would not demand the enforcement of the Treaty of London. But the United States was not bound by that agreement, which was so completely at variance with Wilson's principle of self-determination. One presumed that, pending an examination of these matters, the disputed territories would be occupied by troops of all the Allies. But unfortunately this did not turn out to be the case. France, Britain and America stood by, while the Italians and the Yugoslavs took whatsoever they could lay their hands on. As the Yugoslav military forces had to come overland, while the Italians had command of the sea, it was natural that in most places the Italians got the better of the scramble; and where they found the Yugoslavs in possession, as at Rieka, they usually ousted them by diplomatic methods. And in one way or another they managed to make their holdings tally, as far as possible, with the Treaty of London, and even to go beyond it. Baron Sonnino declined to make a comprehensive statement as to the Italian programme. Of course he desired in the end to exchange Dalmatia—the seizure of which would entail a war with Yugoslavia—against Rieka. But as Italian public opinion had scarcely thought of Rieka during the War, he made it his business to cause them to yearn for that town. His compatriots were asking why Mr. Wilson's Fourteen Points should be waived for France in the Sarre Basin, for Britain in Ireland and Egypt, but not for them. And some of his would-be[29] ingenious compatriots pointed out—their contentions were embodied in the Italian Memorandum to the Supreme Council on January 10, 1920—that as the Treaty of London was based on the presumption that Montenegro, Serbia and Croatia would remain separate States, this instrument had been altogether upset by the merging of those Southern Slavs into one country, Yugoslavia; it followed, therefore, that the Treaty which attributed Rieka to the Croats could no longer be invoked. But the other parts of the Treaty which gave the Slav mainland and islands to Italy were absolutely unassailable. The reader will resent being troubled by this kind of balderdash, but Messrs. Clemenceau, Lloyd-George and Wilson may have resented it even more.

ITALIAN MILDNESS ON THE ISLE OF VIS

On November 3 the Italians arrived outside Vis (Lissa), the most westerly of the large islands, where the entire population of 11,000 is Slav, except for the family of an honoured inhabitant, Dr. Doimi, and three other families related to his. Dr. Doimi's people have lived for many years on this island—his father was mayor of the capital, which is also called Vis, for half a century—and now they have become so acclimatized that, as he told me, three of his four nephews prefer to call themselves Yugoslavs. This phenomenon can be seen all down the Adriatic coast. It has often, for example, been pointed out to Dr. Vio, the very Italian ex-mayor of Rieka, that he has a Croat father and several Croat brothers. Thus also the Duimić family of the same town has one brother married to a Magyar lady and very fond of the Magyars, a second brother who is a Professor at Milan, and a third who lives above Rieka and is a Yugoslav. The terms "Yugoslav" and "Italian" have now come to signify not what a man is, but what he wants to be, applying thus the admirable principle of self-determination. Well, in the old days on the isle of Vis between two and three hundred people belonged to the Autonomist party, owing to their great regard for Dr. Doimi; but these say now that they are Yugoslavs, and the Italians—at[30] all events Captain Sportiello, their chief officer at Vis—acknowledged that they must base their demand on strategic reasons. A day or two before the Italians arrived the population had arrested several Austrian functionaries, including the mayor and three gendarmes, who had maltreated them during the War. None of these persons were Italian; and when the Italian boats were sighted a committee went to meet them joyfully and brought the officers ashore upon their backs. The officers explained that they had come as representatives of the Entente and the United States, and for the object—which appeared superfluous—of protecting Vis from German submarines. If the Italians had been everywhere as inoffensive as at Vis, it would be more agreeable to write about their doings. Captain Sportiello, a naval officer, showed himself throughout the months of his administration to be sensible; he frequented Yugoslav houses. The greatest divergence occurred on June 1, 1919, when the Italians planned to have a demonstration for their national holiday, and asked the inhabitants to come to the bioscope, where they would be regaled with cakes and sweets; the inhabitants replied that they preferred to have Yugoslavia.... But there is a monument in the cemetery at Vis to which I must refer. It is a very fine monument of white marble, erected by the Austrians to commemorate their victory in these waters over the Italian navy in 1866.[9] On the top there is a lion clutching the Italian flag, while on two of the sides there are inscriptions in the German language. One of them, some feet in length, relates that this memorial is placed there for the officers and men who on July 20, 1866, gave their lives in the service of their Emperor and country. The Italians screwed two marble slabs across the upper and the lower parts of this inscription, so that the German lettering of the central part remained visible; on the lower slab one read: "Novembre 1918" and on the upper one "Italia Vincitrice" (Victorious [31]Italy). We were taken by several Italian officers to look at this. They were so proud of it that they presented us with photographs of the monument in its altered state. I fear that the Italian mentality escapes me. I should not have written anything about them.

THEIR TRUCULENCE AT KORČULA

They landed on the same day, November 3, on the beautiful and prosperous island of Korčula (Curzola), putting ashore at Velaluka, the western harbour. With the exception of five families, all the people are Yugoslavs; and the Italians, who sailed in under a white flag, announced that they had come as friends of the Yugoslavs and of the Entente, to preserve order and to protect them against submarines. On the 5th, they went to the town of Korčula, where one of the two officers, Lieutenant Poggi, of the navy, put his assurances in writing, as he had done at Velaluka. He protested against the word "Occupation." On the 7th they returned to Velaluka and on the 12th went back, with about a hundred men, to Korčula. Once more he wrote that he had not come to occupy the island; he added, though, that the district officials should act on the opposite peninsula of Sabioncello in the name of the Yugoslavs, but over Korčula and the island of Lastovo (Lagosta) in the name of Italy—not of the Entente. He wanted to remove the Yugoslav flags from public buildings and substitute Italian flags. When he was reminded of what he had said with regard to the Entente, he exclaimed: "No, no! This is Italy!" The chief district official protested, and refused to carry out Lieut. Poggi's injunctions, nor were the Italians able to do so. This officer remained at Korčula, requisitioning houses and hoisting as many Italian flags as he could. He issued an order that after 6.30 p.m. not more than three persons were allowed to come together in the streets. His men used to offer food to the women of the place, who declined it; after which the food was given to the children, who were previously photographed in an imploring attitude. There was some trouble on December 15 when the Leonidas, an American ship, came in with a number of mine-sweepers.[32] Apparently the Yugoslavs contravened the Italian regulations by omitting to ask whether their band might play in the harbour, but, on the supposition that this would not be accorded to them, went down to the harbour just as if they were not living under regulations. They waved American, Serbian and Croatian flags, all of which the Italians attempted to seize; the most gorgeous one, a Yugoslav flag of silk with gilt fringes, they tore up and divided among themselves as a trophy. When the Leonidas made fast, a lieutenant leaped ashore and placed himself, holding a revolver, in front of an American flag. The captain, according to some reports, had his men standing to their guns, while others of the crew are said to have been given hand-grenades; but whether by this method or another, the turbulence on shore was calmed and the Italians seem to have invited the captain to step off his boat. He preferred, however, to go to another port; the populace came overland. One need not say that there was jollification.... When the other American boats departed, a small one remained at Korčula. One day a steamer came from Metković, having on board a few men of the Yugoslav Legion. The people of Korčula, not being allowed to take the men to their houses, came down quietly to the harbour with coffee and bread, but the carabinieri drove them away. These legionaries were emigrants to Australia and Canada, who had come back to fight for the Entente, including Italy. The Italians wanted to arrest them all on account of a small Croatian flag which one of them was holding, but at the request of the American ship they refrained. A certain Marko Šimunović, who had gone to Australia from the Korčula village of Račišca, went over to speak to the sailors on the American boat. Because of this the carabinieri took him to the military headquarters. He was interned for several months in Italy.

The long island of Hvar (Lesina) was not occupied until November 13. It is interesting, by the by, to note how this island came to have its names. In the time of the Greek colonists it was known as ὁ φἁρος, which subsequently became Farra or Quarra, leading to the name Hvar, by which it is known to the Slavs. They also,[33] in the thirteenth century, gave it an alternative name: Lesna, from the Slav word signifying "wooded," for the Venetians had not yet despoiled the island of many of its forests. Lesna was the popular and Hvar the literary name; and the Italians, taking the former of these, coined the word Lesina, the sound of which makes many of them and of other people think that this is an Italian island.[10] The question of Slav and Italian geographical names in Dalmatia has been carefully investigated by a student at Split. Taking the zone which was made over to the Italians by the Treaty of London, he found that with the exception of a reef called Maon, alongside the island of Pago, every island, village, mountain and river has a Slav name, whereas out of the total of 114 names there were 64 which have no names in Italian; and this is giving the Italians credit for such words as Sebenico, Zemonico and so forth, which in the opinion of philologists are merely modifications of the original Šibenik, Zemunik, etc.

AND ON HVAR

At Starigrad on Hvar the Italians also said that they were representatives of the Entente, but soon they prohibited the national colours. Being perhaps aware that in the whole island, with its population of about 20,000, there were before the War only four or five Italians who were engaged in selling fruit, their countrymen in November 1918 did their best, by the distribution of other commodities—rice, flour and macaroni—to make some more Italians. They succeeded at Starigrad in obtaining fifteen or twenty recruits. And they made it obvious that it would be more comfortable to be an Italian than a Yugoslav. The local Reading-Rooms, whose committee had received no previous warning, fell so greatly under the displeasure of the Italians that one night after ten o'clock—at which time curfew sounded for the Yugoslavs; the Italians and their friends could stay out until any hour—the premises were sacked: knives were used against the pictures, furniture was taken by assault, and [34]mirrors did not long resist the fine élan of the attacking party. Old vases, other ornaments and books were thrown into the harbour near the Sirio, the Italian destroyer which was anchored ten yards from the Reading-Rooms. Of course there was an inquiry; the result of it was that several Yugoslavs (and no others) were imprisoned. The Sirio's commander was a gentleman of some activity; he sent a telegram to Rome and another one to Admiral Millo, the Italian Governor of the occupied parts of Dalmatia, saying that the people of the island longed for annexation. These telegrams he read aloud before the islanders, with all his carabinieri in attendance.... The old-world capital of the island, which is a smaller place than Starigrad, was occupied on the same day. The first serious encounter took place on December 4, when the Italians, who were quartered on the upper floor of the Sokol or gymnastic club, observed that furniture was being taken from the rooms below them and was being carried out into the street. If they had asked the people what they were about they would have heard that these things had been stored in the gymnasium during the War and that the place was now to be devoted to its original purpose. What they did was to believe at once the yarn of a renegade, who told them that the people were preparing to blow up the house. The Italians opened fire, wounded several persons and killed one of their own carabinieri.

HOW THEY WERE RECEIVED AT ZADAR

On the mainland the Italians were received at Šibenik with some suspicion. They announced, however, that they came as representatives of the Allies, and begged for a pilot who would take them into Šibenik's land-locked harbour, through the mine-field. The Yugoslavs consented, and after the Italians had installed themselves they requisitioned sixty Austrian merchant vessels which were lying in that harbour. (They left, as a matter of fact, to the Yugoslavs out of all the ex-Austrian mercantile fleet exactly four old boats—Sebenico, Lussin, Mossor and Dinara—with a total displacement of 390 tons.)[35] On the other hand, at Zadar, they were received in a very friendly fashion. In this town, as it had been the seat of government, with numerous officials and their families, the Autonomist anti-Croat party had been, under Austria, more powerful than in any other town in Dalmatia. With converts coming in from the country, which is entirely Slav, the Autonomists in Zadar had become well over half the population,[11] which is about 14,000, that of the surrounding district being about 23,000. Zadar was thus a place apart from the rest of Dalmatia, and although the Dalmatian Autonomists were unable to claim any of the eleven deputies who went to Vienna, they managed to be represented in the provincial Chamber—the Landtag—by [36]six out of the forty-one members. The Landtag was not elected on the basis of universal suffrage; four out of these six members were chosen by large landowners, one (Dr. Ziliotto, the mayor) by the town of Zadar and one by the Zadar chamber of commerce. Out of the eighty-six communes of Dalmatia, Zadar was the solitary one that was Autonomist. Some very few Autonomists were wont to say that they aspired to union with Italy, but it was generally thought that most of them agreed with Dr. Ziliotto when he said in the Landtag in 1906: "We, separated from Italy by the whole Adriatic—we a few thousand men, scattered, with no territorial links, among a population not of hundreds of thousands but of millions of Slavs, how could we think of union with Italy?" And Dr. Ziliotto was one of those who always regarded himself as an Italian. But whether the Zadar Autonomists were sincere or not when Austria ruled over them, the large majority of them hung out Italian colours after the War, and in this they were undoubtedly sincere, although the motives varied; in some it was the love of Italy, in some it was ambition and in some a thirst for vengeance.

[Although both Yugoslavs and Italians criticize the Austrian figures, it is probable that they are pretty accurate. The census of 1910 gave for Dalmatia: 610,669 Serbo-Croats, 18,028 Italians, 3081 Germans and 1410 Czecho-Slovaks. The Autonomist party claimed that they were not 18,028 but 30,000; and that 150,000 persons in Dalmatia speak Italian. But the Orlando-Sonnino Government really did try its utmost to improve these figures. At the end of November 1918 the Italians, who had charge of the police at Constantinople, put up notices asking all Austrian subjects from Dalmatia to inscribe themselves with the authorities and thus receive protection. In addition to the ordinary large Yugoslav population, the Austrian army was still there, and two of its officers, in uniform, inscribed themselves. The Italians had to endure not a few rebuffs, for they applied to people at their houses—they had found the nationality lists at the police offices. The Dutch were looking after Yugoslav interests, but received no instructions.][37]

WHAT THEY DID THERE

It was thought at Zadar that the Italians would be followed in the course of days by the other Allies. Anyhow the Yugoslavs were in no carping spirit; about 5000 of them assembled to greet the Italian destroyer; they were, in fact, more numerous than the Italians. And perhaps one should record that on this memorable occasion—it was at an early hour—Dr. Ziliotto had to complete his toilette as he ran down to the quay. Soon the Italian captain, shouldered by the crowd, was flourishing two flags, the Italian and the Yugoslav—although his country had, of course, not recognized Yugoslavia. For a little time it was the colour of roses, and the worm that crept into this paradise seems to have been a Japanese warship in whose presence each of the two parties wished to demonstrate how powerful it was. The carabinieri resolved to maintain order, and as an inmate of the seminary made, they said, an unpolished gesture at them from a window they went off and, with some reinforcements, broke into the Slav Reading-Room and damaged it considerably. The Italian officers and men at Zadar went about their duties for some time without permitting themselves to be drawn into local politics, but they were told repeatedly that the Slavs are goats and barbarians, so that at last the men appear to have concluded that strong measures were required. Some of them mingled, in civilian clothes, with the unruly elements, and Zadar's narrow streets became most hazardous for Yugoslav pedestrians. Girls and men alike were roughly handled; thrice in one day, for example, a professor—Dr. Stoikević—had his ears boxed as he went to or was coming from his school. Yet Zadar is a dignified old place; the chief men of the town and the Italian officers did what they could to keep it so. But away from their control some deeds of truculence occurred. The prison warders, as the spirit moved them, forced the Slavs there to be quiet, or to shout "Viva Italia!" Most of the Slavs were in the gaol for having had in their possession Austrian paper money stamped by the Yugoslav authorities; these notes were subsequently declared by the Italians to be illegal; but if a man came from Croatia, for example, and had[38] nothing else, it was a trifle harsh to lock him up and confiscate the money. Eight good people went to Zadar prison owing to the fact that near the ancient town of Biograd they had been sitting underneath the olive trees and singing Croat folk-songs. Nor was it much in keeping with Zadar's dignity when the "Ufficio Propaganda" put out a large red placard which invited boys between the ages of nine and seventeen to join in establishing a "Corpo Nazionale dei giovani esploratori"—that is to say, an association of boy scouts. It is superfluous to inquire as to why these boys were mustered.... When the Austrians collapsed, a few old rifles were seized by the Italians and the Croats, the latter having fifteen or twenty which they hid in various villages. A priest and a medical student were privy to this fearful crime. A hue and cry was raised by the carabinieri—the priest vanished, the student jumped out of a window of his house and also vanished. But the carabinieri would not be denied. They suspected that the Albanians of the neighbouring village of Borgo Erizzo were abetting the Slavs. It was necessary, therefore, to castigate them. The 2500 inhabitants of Borgo Erizzo, nearly all of them Albanians who speak their own language and Serbo-Croat, while 5 per cent. also speak Italian, used to be divided in their sympathies before the War—75 per cent. being adherents of the Slavs in Zadar and 25 per cent. of the Autonomists. Now they have, excepting 5 per cent., gone over to the Slavs, and as they have retained some of the habits of their ancestors, they were not going to let the hostile forces win an easy victory. A student marched in front of the Italians, then about ten carabinieri, then a few ranks of soldiers, and then the mob of Zadar. The Albanians were in two groups, twenty sheltering behind walls to the right of the road and twenty to the left; they were armed with stones, their women folk were bringing them relays of these. The encounter ended in three carabinieri and seven or eight soldiers being wounded. In order to avenge this defeat one Duka, who is by birth an Albanian and is a teacher at the Italian "Liga" school, which was built a few years ago at Borgo Erizzo, determined on the next afternoon to attack the Teachers' Institute, which is situated 400 steps from his own establishment, and which on the previous[39] day had shown a strong defence. He led the attack in person, firing his revolver. But the casualties were light. The Teachers' Institute was, after this, occupied by the military, and Admiral Millo paid a complimentary visit to Duka at his school.

PRETTY DOINGS AT KRK

Proceeding up the Adriatic we come to the Quarnero Islands, of which the most considerable is Krk (Veglia). The whole district had, at the last census, 19,562 inhabitants whose ordinary language was Serbo-Croat, and 1544 who commonly spoke Italian. Of these latter the capital, likewise called Krk, contained 1494, and only 644 who gave themselves out as Slavs. The town, with its tortuous, rather wistful streets, was the residence of the Venetian officials, and five or six of those old families remain. The rest of the 1494 are nearly all Italianized Slavs, who under Austria used to call themselves either Austrians of Italian tongue or else Istrians. However, if they wish to be Italians now, there is none to say them nay. They include five out of the twenty officials, and these five gentlemen seem to have boldly said before the War that it would please them if this island were to be included in the Kingdom of Italy. They did not give their Austrian rulers many sleepless nights; this confidence in them was justified, for during the War they placed themselves in the front rank of those who flung defiant words at Italy, and one of them enlarged his weapon, copying upon his typewriter some Songs of Hate, which probably were sent to him from Rieka or Triest. These typewritten sheets were then circulated in the island. One of them—"Con le teste degli Italiani"—had been specially composed for children and expressed the intention of playing bowls with Italian heads. The songs for adults were less blood-thirsty but not less cruel. The Yugoslavs of the island must have been engaged in other War work; no songs were provided for them.... When Austria collapsed, some youths came from Rieka, flourishing their flags and sticks, and crying, "Down with Austria!" "Long live Italy!" "Long live Yugoslavia!" "Long live King Peter!" There was, in fact general goodwill. A Croat[40] National Council was formed, and was recognized by the Italian party; it introduced a censorship, but as the postmaster's allegiance was given to the minority he sent a telegram to Triest, asking for bread and protection; and on November 15 the Stocco arrived. Other people soon departed; the Bishop's chancellor and his chaplain, two magistrates and a Custom-house official, were shipped off to Italy or Sardinia, while the owner of the typewriter flew off as a delegate to Paris, having persuaded the town council of the capital to vote a sum of 36,000 crowns for his expenses—but a crown was now worth less than half a franc. However, two members of the town council thought that it was a waste of money; but when they were threatened with internment in Sardinia they withdrew their active opposition, and the delegate set out. On the way he granted an interview to an Italian journalist, and depicted the spontaneous enthusiasm with which the islanders had called for Italy. But the journalist had heard of the National Council and he asked, very naturally, whether it shared these sentiments. "Ha parlato da Italiano!" ("I have spoken as an Italian"), replied the delegate; and when the newspaper reached the island, this cryptic saying was interpreted in various ways, his critics pointing out that, as he had diverged from truthfulness, this was another little Song of Hate. The Bishop, Dr. Mahnić,[12] did not go to Italy for several months. He was a learned Slovene, an ex-Professor of Gorica University, known also as a stern critic of any poetry which was not dogmatically religious. He gave vent to his dislike of the poetry of Gregorčić and Aškerc, both of them priests. The former, being of a mild disposition, bowed before the storm; but Aškerc wrote a cutting satire on his critic. The Austrians, disapproving of his religious and patriotic activities, thought they would smother him by this appointment to a rather out-of-the-way diocese. But his influence spread far beyond it, and in the islands he was so solicitous for the people's material welfare that, for example, he founded savings-banks, which were [41]a great success. It was unavoidable, as he was a man of character, that he should come into conflict with the Italians, for their commanding officer, a naval captain of Hungarian origin, was not a suave administrator. He charged a priest with making Yugoslav propaganda because he catechized the little children in their own language; another priest on the island of Unie, which forms a part of the diocese, was accused of making propaganda, because he has had in his church two statues—which had been there for years—of SS. Cyril and Methodus. They were removed from the church, he put them back; finally he was himself expelled and Unie remained without a priest. The naval captain was irritated by the old Slavonic liturgy, which is used in all except four churches of the diocese, but if he could not alter this—Dr. Mahnić referring him to the Pope—he and the Admiral at Pola, Admiral Cagni, could manage with some trouble to rid themselves of the bishop. This gentleman, who was in his seventieth year and an invalid, said that he would perhaps go to Rome after Easter. On March 24 the captain told him that the admiral had settled he should sail in three days, but the bishop was ill. On the 26th the captain returned with a lieutenant of carabinieri to ask if the bishop was still ailing; the admiral, it seemed, had ordered that two other doctors—the officer of health for the district and an Italian army doctor—should verify the report of the bishop's own medical attendant. The three of them quarrelled for two hours, but finally they all signed a memorandum that the bishop was ill. On the 31st the captain came to say that a destroyer would arrive and that it would take the bishop wherever he wanted to go, for the Italians had made up their minds that go he must. He had objected far too vigorously to their methods—not approving, for example, of the written permit which was given in the autumn to the people of two villages in Krk, on which it stated that these people could supply themselves with timber at Grdnje. This was a State forest, rented by a certain man; but the Italians acknowledged that what they wanted was adherents, and these grateful villagers, if there should be a plebiscite, would vote for them. The man appealed to justice, but the judge received a verbal[42] order not to act. The villagers were given a general amnesty on January 1, an Italian flag was hoisted at the judge's office—the judge had gone away. Another transaction which the bishop had resented was after a visit paid by the captain and another officer of the French warship Annamite to the Yugoslav Reading-Rooms at Lošinj mali (Lussinpiccolo); a priest and two other gentlemen had escorted their guests to the harbour at 11 p.m.; during the night all three were arrested and the priest deported. When the Annamite put in at the lofty island of Cres (Cherso) and a couple of officers went to the Franciscan monastery, it resulted in the monastery being closed and the monks removed. Their simple act of courtesy was, said the Italians, propaganda. From Lošinj mali and Cres five ladies were collected, four of them being teachers and one the wife of the pilot, Sindičić. They were guilty of having greeted the French, and on account of this were taken to the prison at Pola. Afterwards in Venice they were kept for six weeks in the company of prostitutes and from there they passed to Sardinia, on which island they were retained for nine months. As for Dr. Mahnić, he set sail on April 4 at 6 a.m. Being asked whither he would like to go, he said he wished to be put down at Zengg on the mainland. "Excellent," said the Italians; but after a few minutes they said they had received a radio from Pola that the bishop must be taken to Ancona. He was afterwards allowed to live in a monastery near Rome.

UNHAPPY POLA

The Italians had not been two days in Pola—in which arsenal town the population, unlike that of the country, mostly uses the Italian language—when they made themselves disliked by both parties. The President of the Italian National Council was told by the Admiral that an Austrian crown was to be worth forty Italian centesimi. This, said the Admiral, was an order from Rome. The President explained that this meant ruin for the people of the town. He asked if he might telegraph to Rome. "I am Rome!" said the Admiral, or words to that effect. Thereupon the President and the colleagues who were with him said they would never come again to see the[43] Admiral "If I want you," said the Admiral, "I will have you brought by a couple of carabinieri." On the next day red flags were flying on the arsenal and on the day after the Italian troops were taken elsewhere, while 10,000 fresh ones came from Italy. And Pola, in exchange for troops, gave coal. For some time the Italians carried off two trainloads of it every day. This absence of coal from their own native country, which rather places them at the mercy of the coal-producing lands, seems to be more their misfortune than anybody's fault, yet the Italian party of Rieka added this to their grievances against France and Great Britain. Those two countries ought, they said, in very decency, to correct the oversights of Providence; but no very practical suggestions were put forward.

WHAT ISTRIA ENDURED