Title: The Honourable Mr. Tawnish

Author: Jeffery Farnol

Illustrator: C. E. Brock

Release date: March 27, 2008 [eBook #24922]

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/24922

Credits: Produced by Bernd Meyer, Suzanne Shell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BY

JEFFERY FARNOL

Author of "The Broad Highway," and

"The Amateur Gentleman"

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

CHARLES E. BROCK

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1913

Copyright, 1913,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Published, October, 1913

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

To

DOROTHY

THE BEST AND GENTLEST OF SISTERS

THE TRUEST AND BRAVEST OF COMRADES

I DEDICATE THIS BOOK

JEFFREY FARNOL

London, August 28, 1913

Chapter One

Introducing Mr. Tawnish, and what befell

at "The Chequers"

Myself and Bentley, who, though a good fellow in many ways, is yet a fool in more (hence the prominence of the personal pronoun, for, as every one knows, a fool should give place to his betters)—myself and Bentley, then, were riding home from Hadlow, whither we had been to witness a dog-fight (and I may say a better fight I never saw, the dog I had backed disabling his opponent very effectively in something less than three-quarters of an hour—whereby Bentley owes me a hundred guineas)—we were riding home as I say, and were within a half-mile or so of Tonbridge, when young Harry Raikes came up behind us at his usual wild gallop, and passing with a curt nod, disappeared down the hill in a cloud of dust.

"Were I but ten years younger," says I, looking after him, "Tonbridge Town would be too small to hold yonder fellow and myself—he is becoming a positive pest."

"True," says Bentley, "he's forever embroiling some one or other."

"Only last week," says I, "while you were away in London, he ran young Richards through the lungs over some triviality, and they say he lies a-dying."

"Poor lad! poor lad!" says Bentley. "I mind, too, there was Tom Adams—shot dead in the Miller's Field not above a month ago; and before that, young Oatlands, and many others besides—"

"Egad," says I, "but I've a great mind to call 'out' the bully myself."

"Pooh!" says Bentley, "the fellow's a past master at either weapon."

"If you will remember, there was a time when I was accounted no mean performer either, Bentley."

"Pooh!" says Bentley, "leave it to a younger man—myself, for instance."

"Why, there is but a month or two betwixt us," says I.

"Six months and four days," says he in his dogged fashion; "besides," he went on, argumentatively, "should it come to small-swords, you are a good six inches shorter in the reach than Raikes; now as for me—"

"You!" says I, "Should it come to pistols you could not help but stop a bullet with your vast bulk."

Hereupon Bentley must needs set himself to prove that a big man offered no better target than a more diminutive one, all of which was of course but the purest folly, as I very plainly showed him, whereat he fell a-whistling of the song "Lillibuleero" (as is his custom ever, when at all hipped or put out in any way). And so we presently came to the cross-roads. Now it has been our custom for the past twelve years to finish the day with a game of picquet with our old friend Jack Chester, so that it had become quite an institution, so to speak. What was our surprise then to see Jack himself upon his black mare, waiting for us beneath the finger-post. That he was in one of his passions was evident from the acute angle of his hat and wig, and as we approached we could hear him swearing to himself.

"Bet you fifty it's his daughter," says Bentley.

"Done!" says I, promptly.

"How now, Jack?" says Bentley, as we shook hands.

"May the Devil anoint me!" growled Jack.

"Belike he will," says Bentley.

"Here's an infernal state of affairs!" says Jack, frowning up the road, his hat and wig very much over one eye.

"Why, what's to do?" says I.

"Do?" says he, rapping out three oaths in quick succession—"do?—the devil and all's to do!"

"Make it a hundred?" says Bentley aside.

"Done!" says I.

"To think," groans Jack, blowing out his cheeks and striking himself a violent blow in the chest, "to think of a pale-faced, pranked-out, spindle-shanked, mealy-mouthed popinjay like him!"

"Him?" says I, questioningly.

"Aye—him!" snaps Jack, with another oath.

"Make it a hundred and fifty, Bentley?" says I softly.

"Agreed!" says Bentley.

"To think," says Jack again, "of a prancing puppy-dog, a walking clothes-pole like him—and she loves him, sir!"

"She?" repeated Bentley, and chuckled.

"Aye, she, sir," roared Jack; "to think after the way we have brought her up, after all our care of her, that she should go and fall in love with a dancing, dandified nincompoop, all powder and patches. Why damme! the wench is run stark, staring mad. Egad! a nice situation for a loving and affectionate father to be placed in!"

"Father?" says I.

"Aye, father, sir," roars Jack again, "though I would to heaven Penelope had some one else to father her—the jade!"

"What!" says I, unheeding Bentley's leering triumph (Bentley never wins but he must needs show it) "what, is Penelope—fallen in love with somebody?"

"Why don't I tell you?" cries Jack, "don't I tell you that I found a set of verses—actually poetry, that the jackanapes had written her?"

"Did you tax her with the discovery?" says I.

"To be sure I did, and the minx owned her love for him—vowed she'd never wed another, and positively told me she liked the poetry stuff. After that, as you may suppose, I came away; had I stayed I won't answer for it but that I might have boxed the jade's ears. Oh, egad, a pretty business!"

"And I thought we had settled she was to marry Bentley's nephew Horace some day," says I, as we turned into the High Street.

"It seems she has determined otherwise—the vixen; and a likely lad, too, as I remember him," says Jack, shaking his head.

"Where is he now, Bentley?" says I.

"Humph!" says Bentley, thoughtfully. "His last letter was writ from Venice."

"Aye, that's it," says Jack, "while he's gadding abroad, this mincing, languid ass, this—"

"What did you say was the fellow's name?" says I.

"Tawnish!" says Jack, making a wry face over it, "the Honourable Horatio Tawnish. Come, Dick and Bentley, what shall we do in the matter?"

"Speaking for myself," I returned, "it's devilish hard to determine."

"And speaking for us all," says Bentley, "suppose we thrash out the question over a bottle of wine?" and swinging into the yard of "The Chequers" hard by, he dismounted and led the way to the sanded parlour.

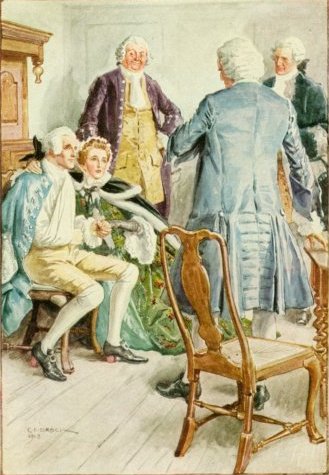

We found it empty (as it usually is at this hour) save for a solitary individual who lounged upon one of the settles, staring into the fire.

He was a gentleman of middling height and very slenderly built, with a pair of dreamy blue eyes set in the oval of a face whose pallor was rendered more effective by a patch at the corner of his mouth. His coat, of a fine blue satin laced with silver, sat upon him with scarce a wrinkle (the which especially recommended itself to me); white satin small-clothes and silk stockings of the same hue, with silver-buckled, red-heeled shoes, completed a costume of an elegance seldom seen out of London. I noticed also that his wig, carefully powdered and ironed, was of the very latest French mode (vastly different to the rough scratch wigs usually affected by the gentry hereabouts), while the three-cornered hat upon the table at his elbow was edged with the very finest point. Altogether, there was about him a certain delicate air that reminded me of my own vanished youth, and I sighed. As I took my seat, yet wondering who this fine gentleman might be, Jack seized me suddenly by the arm.

"Look!" says he in my ear, "damme, there sits the fellow!"

Turning my head, I saw that the gentleman had risen, and he now tripped towards us, his toes carefully pointed, while a small, gold-mounted walking cane dangled from his wrist by a riband.

"I believe," says he, speaking in a soft, affected voice, "I believe I have the felicity of addressing Sir John Chester?"

"The same, sir," said Jack, rising, "and, sir, I wish a word with you." Here, however, remembering myself and Bentley, he introduced us—though in a very perfunctory fashion, to be sure.

"Sir John," says Mr. Tawnish, "your very obedient humble; gentlemen—yours," and he bowed deeply to each of us in turn, with a prodigious flourish of the laced hat.

"I repeat, Sir," says Jack, returning his bow, very stiff in the back, "I repeat, I would have a word with you."

"On my soul, I protest you do me too much honour!" he murmured—"shall we sit?" Jack nodded, and Mr. Tawnish sank into a chair between myself and Bentley.

"Delightful weather we are having," says he, breaking in upon a somewhat awkward pause, "though they do tell me the country needs rain most damnably!"

"Mr. Tawnish," says Jack, giving himself a sudden thump in the chest, "I have no mind to talk to you of the weather."

"No?" says Mr. Tawnish, with a tinge of surprise in his gentle voice, "why then, I'm not particular myself, Sir John—there are a host of other matters—horses and dogs, for instance."

"The devil take your horses and dogs, sir!" cries Jack.

"Willingly," says Mr. Tawnish, "to speak the truth I grow something tired of them myself; there seems very little else talked of hereabouts."

"Mr. Tawnish," says Jack, beginning to lose his temper despite my admonitory frown, "the matter on which I would speak to you is my daughter, sir, the Lady Penelope."

"What—here, Sir John?" cries Mr. Tawnish, in a horrified tone, "in the tap of an inn, with a—pink my immortal soul!—a sanded floor, and the very air nauseous with the reek of filthy tobacco? No, no, Sir John, indeed, keep to horses and dogs, I beg of you; 'tis a subject more in harmony with such surroundings."

"Now look you, sir," says Jack, blowing out his cheeks, "'tis a good enough place for what I have to say to you, sanded floor or no, and I promise it shall not detain you long."

Hereupon Jack rose with a snort of anger, and began pacing to and fro, striking himself most severely several times, while Mr. Tawnish, drawing out a very delicate, enamelled snuff-box, helped himself to a leisurely pinch, and regarded him with a mild astonishment.

"Sir," says Jack, turning suddenly with a click of spurred heels, "you are in the habit of writing poetry?"

The patch at the corner of the Honourable Horatio's mouth quivered for a moment. "Really, my dear Sir John—" he began.

"You sent a set of verses to my daughter, sir," Jack broke in, "well, damme, sir, I don't like poetry!"

"I do not doubt it for a moment, sir," says Mr. Tawnish, "but these were written, if you remember, to—the lady."

"Exactly," cries Jack, "and you will understand, sir, that I forbid poetry, once and for all—curse me, sir, I'll not permit it!"

"This new French sauce that London is gone mad over is a thought too strong of garlic, to my thinking," says Mr. Tawnish, flicking a stray grain of snuff from his cravat. "You will, I think, agree with me, Sir John, that to a delicate palate—"

"The devil anoint your French sauce, sir," cries Jack, in a fury, "who's talking of French sauces?"

"My very dear Sir John," says Mr. Tawnish, with an engaging smile, "when one topic becomes at all—strained, shall we say?—I esteem it the wiser course to change the subject, having frequently proved it to have certain soothing and calming effects—hence my sauce."

Here Bentley sneezed and coughed both together and came nigh choking outright (a highly dangerous thing in one of his weight), which necessitated my loosening his steenkirk and thumping him betwixt the shoulder-blades, while Jack strode up and down, swearing under his breath, and Mr. Tawnish took another pinch of snuff.

"French sauce, by heaven!" cries Jack suddenly, "did any man ever hear the like of it?—French sauce!" and herewith he snatched off his wig and trampled upon it, and Bentley choked himself purple again. I will admit that Jack's round bullet head, with its close-cropped, grizzled hair standing on end, would have been a whimsical, not to say laughable sight in any other (Bentley for instance)—but Jack in a rage is no laughable matter.

"By the Lord, sir," cries he, turning upon Mr. Tawnish, who sat cross-legged, regarding everything with the same mild wonderment—"by the Lord! I'd call you out for that French sauce if I thought you were a fighting man."

"Heaven forfend!" exclaimed Mr. Tawnish, with a gesture of horror, "violence of all kinds is abhorrent to my nature, and I have always regarded the duello as a particularly clumsy and illogical method of settling a dispute."

Hereupon Jack looked about him in a helpless sort of fashion, as indeed well he might, and catching sight of his wig lying in the middle of the floor, promptly kicked it into a corner, which seemed to relieve him somewhat, for he went to it and, picking it up again, knocked out the dust upon his knee, and setting it on very much over one eye, sat himself down again, flushed and panting, but calm.

"Mr. Tawnish," says he, "as regards my daughter, I must ask—nay demand—that you cease your persecution of her once and for all."

"Sir John," says Mr. Tawnish, bowing across the table, "allow me to suggest in the most humble and submissive manner, that the word 'persecution' is perhaps a trifle—I say just a trifle—unwarranted."

"Be that as it may, sir, I repeat it, nevertheless," says Jack, "and furthermore I must insist that you communicate no more with the Lady Penelope either by poetry or—or any other means."

"Alas!" sighs Mr. Tawnish, "cheat myself as I may, the possibility will obtrude itself that you do not look upon my suit with quite the degree of warmth I had hoped. Sir, I am not perfect, few of us are, but even you will grant that I am not altogether a savage?" As he ended, he helped himself to another pinch of snuff with a pretty, delicate air such as a lady would use in taking a comfit; indeed his hand, small and elegantly shaped, whose whiteness was accentuated by the emerald and ruby ring upon his finger, needed no very strong effort of fancy to be taken for a woman's outright. I saw Jack's lip curl and his nostrils dilate at its very prettiness.

"There be worse things than savages, sir," says he, pointedly.

"Indeed, Sir John, you are very right—do but hearken to the brutes," says Mr. Tawnish, with lifted finger, as from the floor above came a roar of voices singing a merry drinking-catch, with the ring of glasses and the stamping of spurred heels. "Hark to 'em," he repeated, with a gesture of infinite disgust; "these are creatures the which, having all the outward form and semblance of man, yet, being utterly devoid of all man's finer qualities, live but to quarrel and fight—to eat and drink and beget their kind—in which they be vastly prolific, for the world is full of such. To-night it would seem they are in a high good humour, wherefore they are a trifle more boisterous than usual, indulging themselves in these howlings and shoutings, and shall presently drink themselves out of what little wit Dame Nature hath bestowed upon 'em, and be carted home to bed by their lackeys—pah!"

"How—what?" gasps Jack, while I sat staring (very nearly open-mouthed) at the cool audacity of the fellow.

"Are you aware, sir," cries Jack, when at last he had regained his breath, "that the persons you have been decrying are friends of mine, gallant gentlemen all—aye, sir, damme, and men to boot!—hard-fighting, hard-riding, hard-drinking, six-bottle gentlemen, sir?"

"I fear me my ignorance of country ways hath led me into a grave error," says Mr. Tawnish, with a scarce perceptible shrug of the shoulders; "upon second thoughts I grant there is about a man who can put down one throat what should suffice for six, something great."

"Or roomy!" adds Bentley, in a strangling voice.

"We are at side issues," says Jack, very red in the face, "the point being, that I forbid you my daughter once and for all."

"Might I enquire your very excellent reasons?"

"Plainly, then," returns Jack, hitting himself in the chest again, "the Lady Penelope Chester must and shall marry a man, sir."

"Yes," nodded Mr. Tawnish, "a man is generally essential in such cases, I believe."

"I say a man, sir," roared Jack, "and, damme, I mean a man, and not a clothes-horse or a dancing master, or—or a French sauce, sir. One who will not faint if a dog bark too loudly, nor shiver at sight of a pistol, nor pick his way ever by smooth roads. He must be a man, I say, able to use a small-sword creditably, who knows one end of a horse from another, who can win well but lose better, who can follow the hounds over the roughest country and not fall sick for a trifle of mud, nor fret a week over a splashed coat—in a word, he must be a man, sir."

"Alas, what a divine creature is man, after all!" sighs Mr. Tawnish, with a shake of the head, "small matter of wonder if I cannot attain unto so high an estate; for I beg you to observe that though I am tolerably efficient in the use of my weapon" (here he laid his hand lightly upon the silver hilt of his small-sword), "though I can tell a spavined horse from a sound one, and can lose a trifle without positive tears, yet—and I say it with a sense of my extreme unworthiness—I have an excessive and abiding horror of mud, or dirt in any shape or form. But is there no other way, Sir John? In remote times it was the custom in such cases to set the lover some arduous task—some enterprise to try his worth. Come now, in justice do the same by me, I beg, and no matter how difficult the undertaking, I promise you shall at least find me zealous."

"Come, Jack," cries Bentley, suddenly, "smite me, but that's very fair and sportsmanlike! How think you, Dick?"

"Why, for once I agree with you, Bentley," says I, "'tis an offer not devoid of spirit, and should be accepted as such."

Jack sat down, took two gulps of wine, and rose again.

"Mr. Tawnish," says he, "since these gentlemen are in unison upon the matter, and further, knowing they have the good of the Lady Penelope at heart as much as I, I will accept your proposition, and we will, each of us, set you a task. But, sir, I warn you, do not delude yourself with false hopes; you shall not find them over-easy, I'll warrant."

Mr. Tawnish bowed, with the very slightest shrug of his shoulders.

"Firstly, then," Jack began, "you must—er—must—" Here he paused to rub his chin and stare at his boots. "Firstly," he began again, "if you shall succeed in doing—" Here his eyes wandered slowly up to the rafters, and down again to me. "Curse it, Dick!" he broke off, "what the devil must he do?"

"Firstly," I put in, "you must accomplish some feat the which each one of us three shall avow to be beyond him."

"Good!" cries Jack, rubbing his hands, "excellent—so much for the first. Secondly—I say secondly—er—ha, yes—you must make a public laughing stock of that quarrelsome puppy, Sir Harry Raikes. Raikes is a dangerous fellow and generally pinks his man, sir."

"So they tell me," nodded Mr. Tawnish, jotting down a few lines in his memorandum.

"Thirdly," ended Bentley, "you must succeed in placing all three of us—namely, Sir Richard Eden, Sir John Chester, and myself—together and at the same time, at a disadvantage."

"Now, sir," says Jack, complacently, "prove your manhood equal to these three tasks, and you shall be free to woo and wed the Lady Penelope whenever you will. How say you, Dick and Bentley?"

"Agreed," we replied.

"Indeed, gentlemen," says Mr. Tawnish, glancing at his memoranda with a slight frown, "I think the labours of Hercules were scarce to be compared to these, yet I do not altogether despair, and to prove to you my readiness in the matter, I will, with your permission, go and set about the doing of them." With these words he rose, took up his hat, and with a most profound obeisance turned to the door.

At this moment, however, there came a trampling of feet upon the stairs, another door was thrown open, and in walked Sir Harry Raikes himself, followed by D'Arcy and Hammersley, with three or four others whose faces were familiar. They were all in boisterous spirits, Sir Harry's florid face being flushed more than ordinary with drinking, and there was an ugly light in his prominent blue eyes.

Now, it so happened that to reach the street, Mr. Tawnish must pass close beside him, and noting this, Sir Harry very evidently placed himself full in the way, so that Mr. Tawnish was obliged to step aside to avoid a collision; yet even then, Raikes thrust out an elbow in such a fashion as to jostle him very unceremoniously. Never have I seen an insult more wanton and altogether unprovoked, and we all of us, I think, ceased to breathe, waiting for the inevitable to follow.

Mr. Tawnish stopped and turned. I saw his delicate brows twitch suddenly together, and for a moment his chin seemed more than usually prominent—then all at once he smiled—positively smiled, and shrugged his shoulders with his languid air.

"Sir," says he, with a flash of his white teeth, "it seems they make these rooms uncommon small and narrow, for the likes of you and me—your pardon." And so, with a tap, tap, of his high, red-heeled shoes, he crossed to the door, descended the steps, turned up the street, and was gone.

"He—he begged the fellow's pardon!" spluttered Jack, purple in the face.

"A more disgraceful exhibition was never seen," says I, "the fellow's a rank coward!" As for Bentley, he only fumbled with his wine-glass and grunted.

The departure of Mr. Tawnish had been the signal for a great burst of laughter from the others, in the middle of which Sir Harry strolled up to our table, nodding in the insolent manner peculiar to him.

"They tell me," said he, leering round upon us, "they tell me your pretty Penelope takes something more than a common interest in yonder fop; have a care, Sir John, she's a plaguey skittish filly by the looks of her, have a care, or like as not—"

But here his voice was drowned by the noise of our three chairs, as we rose.

"Sir Harry Raikes," says I, being the first afoot, "be you drunk or no, I must ask you to be a little less personal in your remarks—d'ye take me?"

"What?" cries Raikes, stepping up to me, "do you take it upon yourself to teach me a lesson in manners?"

"Aye," says Bentley, edging his vast bulk between us, "a hard task, Sir Harry, but you be in sad need of one."

"By God!" cries Raikes, clapping his hand to his small-sword, "is it a quarrel you are after? I say again that the wench—"

The table went over with a crash, and Raikes leaped aside only just in time, so that Jack's fist shot harmlessly past his temple. Yet so fierce had been the blow, that Jack, carried by its very impetus, tripped, staggered, and fell heavily to the floor. In an instant myself and Bentley were bending over him, and presently got him to his feet, but every effort to stand served only to make him wince with pain; yet balancing himself upon one leg, supported by our shoulders, he turned upon Raikes with a snarl.

"Ha!" says he, "I've long known you for a drunken rascal—fitter for the stocks than the society of honest gentlemen, now I know you for a liar besides; could I but stand, you should answer to me this very moment."

"Sir John, if you would indulge me with the pleasure," says I, putting back the skirt of my coat from my sword-hilt, "you should find me no unworthy substitute, I promise."

"No, no," says Bentley, "being the younger man, I claim this privilege myself."

"I thank you both," says Jack, stifling a groan, "but in this affair none other can take my place."

Raikes laughed noisily, and crossing the room, fell to picking his teeth and talking with his friend, Captain Hammersley, while the others stood apart, plainly much perturbed, to judge from their gestures and solemn faces. Presently Hammersley rose, and came over to where Jack sat betwixt us, swearing and groaning under his breath.

"My dear Sir John," says the Captain, bowing, "in this much-to-be-regretted, devilish unpleasant situation, you spoke certain words in the heat of the moment which were a trifle—hasty, shall we say? Sir Harry is naturally a little incensed, still, if upon calmer consideration you can see your way to retract, I hope—"

"Retract!" roars Jack, "retract—not a word, not a syllable; I repeat, Sir Harry Raikes is a scoundrel and a liar—"

"Very good, my dear Sir John," says the Captain, with another bow; "it will be small-swords, I presume?"

"They will serve," says Jack.

"And the time and place?"

"Just so soon as I can use this leg of mine," says Jack, "and I know of no better place than this room. Any further communication you may have to make, you will address to my friend here, Sir Richard Eden, who will, I think, act for me?"

"Act for you?" I repeated, in great distress, "yes, yes—assuredly."

"Then we will leave it thus for the present, Sir John," says the Captain, bowing and turning away, "and I trust your foot will speedily be well again."

"Which is as much as wishing me speedily dead!" says Jack, with a rueful shake of the head. "Raikes is a devil of a fellow and generally pinks his man—eh, Dick and Bentley?"

"Oh, my poor Jack!" sighed Bentley, turning his broad back upon Sir Harry, who, having bowed to us very formally, swaggered off with the others at his heels.

"Man, Jack," says I, "you'll never fight—you cannot—you shall not!"

"Aye, but I shall!" says Jack, grimly.

"'Twill be plain murder!" says Bentley.

"And—think of Pen!" says I.

"Aye, Pen!" sighed Jack. "My pretty Pen! She'll be lonely awhile, methinks, but—thank God, she'll have you and Bentley still!"

And so, having presently summoned a coach (for Jack's foot was become too swollen for the stirrup), we all three of us got in and were driven to the Manor. And I must say, a gloomier trio never passed out of Tonbridge Town, for it was well known to us that there was no man in all the South Country who could stand up to Sir Harry Raikes; and moreover, that unless some miracle chanced to stop the meeting, our old friend was as surely a dead man as if he already lay in his coffin.[Pg 50]

Chapter Two

Of the further astonishing conduct of the

said Mr. Tawnish

Myself and Bentley were engaged upon our usual morning game of chess, when there came a knocking at the door, and my man, Peter, entered.

"Checkmate!" says I.

"No!" says Bentley, castelling.

"Begging your pardon, Sir Richard," says Peter, "but here's a man with a message."

"Oh, devil take your man with a message, Peter!—the game is mine in six moves," says I, bringing up my queen's knight.

"No," says Bentley, "steady up the bishop."

"From Sir John Chester," says Peter, holding the note under my nose.

"Oh! Sir John Chester—check!"

"What in the world can Jack want?" says Bentley, reaching for his wig.

"Check!" says I.

"Why, what can have put him out again?" says Bentley, pointing to the letter—"look at the blots."

Jack is a bad enough hand with the pen at all times, but when in a passion, his writing is always more or less illegible by reason of the numerous blots and smudges; on the present occasion it was very evident that he was more put out than usual.

"Some new villainy of the fellow Raikes, you may depend," says I, breaking the seal.

"No," says Bentley, "I'll lay you twenty, it refers to young Tawnish."

"Done!" I nodded, and spreading out the paper I read (with no little difficulty) as follows:

Dear Dick and Bentley,

Come round and see me at once, for the devil anoint me if I ever heard tell the like on't, and more especially after the exhibition of a week ago. To my mind, 'tis but a cloak to mask his cowardice, as you will both doubtless agree when you shall have read this note.

Yours,

Jack.

"Well, but where's his meaning? 'Tis ever Jack's way to forget the very kernel of news," grumbled Bentley.

"Pooh! 'tis plain enough," says I, "he means Raikes; any but a fool would know that."

"Lay you fifty it's Tawnish," says Bentley, in his stubborn way.

"Done!" says I.

"Stay a moment, Dick," says Bentley, as I rose, "what of our Pen,—she hasn't asked you yet how Jack hurt his foot, has she?"

"Not a word."

"Ha!" says Bentley, with a ponderous nod, "which goes to prove she doth but think the more, and we must keep the truth from her at all hazards, Dick—she'll know soon enough, poor, dear lass. Now, should she ask us—as ask us she will, 'twere best to have something to tell her—let's say, he slipped somewhere!"

"Aye," I nodded, "we'll tell her he twisted his ankle coming down the step at 'The Chequers'—would to God he had!" So saying, we clapped on our hats and sallied out together arm in arm. Jack and I are near neighbours, so that a walk of some fifteen minutes brought us to the Manor, and proceeding at once to the library, we found him with his leg upon a cushion and a bottle of Oporto at his elbow—a-cursing most lustily.

"Well, Jack," says Bentley, as he paused for breath, "and how is the leg?"

"Leg!" roars Jack, "leg, sir—look at it—useless as a log—as a cursed log of wood, sir—snapped a tendon—so Purdy says, but Purdy's a damned pessimistic fellow—the devil anoint all doctors, say I!"

"And pray, what might be the meaning of this note of yours?" and I held it out towards him.

"Meaning," cries Jack, "can't you read—don't I tell you? The insufferable insolence of the fellow."

"Faith!" says I, "if it's Raikes you mean, anything is believable of him—"

"Raikes!" roars Jack, louder than ever, "fiddle-de-dee, sir! who mentioned that rascal—you got my note?"

"In which you carefully made mention of no one."

"Well, I meant to, and that's all the difference."

"To be sure," added Bentley,—"it's young Tawnish; anybody but a fool would know that."

"To be sure," nodded Jack. "Dick," says he, turning upon me suddenly, "Dick, could you have passed over such an insult as we saw Raikes put upon him the other day?"

"No!" I answered, very short, "and you know it."

Jack turned to Bentley with a groan.

"And you, Bentley, come now," says he, "you could, eh!—come now?"

"Not unless I was asleep or stone blind, or deaf," says Bentley.

"Damme! and why not?" cries Jack, and then groaned again. "I was afraid so," says he, "I was afraid so."

"Jack, what the devil do you mean?" I exclaimed.

For answer he tossed a crumpled piece of paper across to me. "Read that," says he, "I got it not an hour since—read it aloud." Hereupon, smoothing out the creases, I read the following:

Tonbridge, Octr. 30th, 1740.

My dear Sir John,

Fortune, that charming though much vilified dame, hath for once proved kind, for the first, and believe me by far the most formidable of my three tasks, namely, to perform that which each one of you shall avow to be beyond him, is already accomplished, and I make bold to say, successfully.

To be particular, you could not but notice the very objectionable conduct, I might say, the wanton insolence of Sir Harry Raikes upon the occasion of our last interview. Now, Sir John, you, together with Sir Richard Eden and Mr. Bentley, will bear witness to the fact that I not only passed over the affront, but even went so far as to apologise to him myself, wherein I think I can lay claim to having achieved that which each one of you will admit to have been beyond his powers.

Having thus fulfilled the first undertaking assigned me, there remain but two, namely, to make a laughing stock of Sir Harry Raikes (which I purpose to do at the very first opportunity) and to place you three gentlemen at a disadvantage.

So, my dear Sir John, in hopes of soon gaining your esteem and blessing (above all), I rest your most devoted, humble, obedient,

Horatio Tawnish.

"This passes all bounds," says I, tossing the letter upon the table, "such audacity—such presumption is beyond all belief; the question is, whether the fellow is right in his head."

"No, Dick," says Bentley, helping himself to the Oporto, "the question is rather—whether he is wrong in his assertion."

"Why, as to that—" I began, and paused, for look at it as I might 'twas plain enough that Mr. Tawnish had certainly scored his first point.

"We all agree," continued Bentley, "that we none of us could do the like; it therefore follows that this Tawnish fellow wins the first hand."

"Sheer trickery!" cries Jack, hurling his wig into the corner—"sheer trickery—damme!"

"Fore gad! Jack," says I, "this fellow's no fool, if he 'quits himself of his other two tasks as featly as this, sink me! but I must needs begin to love him, for look you, fair is fair all the world over and I agree with Bentley, for once, that Mr. Tawnish wins the first hand."

"Ha!" cries Jack, "and because the rogue has tricked us once, would you have us sit by and let Pen throw herself away upon a worthless, fortune-hunting fop—"

"Why, as to that, Jack," says Bentley, "a bargain's a bargain—"

"Pish!" roared Jack, fumbling in his pocket, "why only this very morning I came upon more of his poetry-stuff! Here," he continued, tossing a folded paper on the table in front of Bentley, "it seems the young rascal's been meeting her—over the orchard wall. Read it, Bentley—read it, and see for yourself." Obediently Bentley took up the paper and read as here followeth:

"'Dear Heart—'"

"Bah!" snorted Jack.

"'Dear Heart!'" read Bentley again and with a certain unction:

"'Dear Heart,

I send you these few lines, poor though they be, for since they were inspired by my great love for thee, that of itself, methinks, should make them more worthy,

Thine, as ever,

Horatio.'"

"You mark that?" cries Jack, excitedly, "'hers as ever,' and 'Horatio!' Horatio—faugh! I could ha' taken it kinder had he called himself Tom, or Will, or George, but 'Horatio'—oh, damme! And now comes the poetry-stuff."

Hereupon Bentley hummed and ha'd, and clearing his throat, read this:

"'Slumbers keep,'" snorted Jack, "the insolence of the fellow! Now look on t'other side."

"'I shall be in the orchard to-morrow at the usual hour, in the hope of a word or a look from you.'"

Bentley read, and laid down the paper.

"At the usual hour—d'ye mark that!" cries Jack, thumping himself in the chest—"'tis become a habit with 'em, it seems—and there's for ye, and a nice kettle o' fish it is!"

"Ah, Bentley," says I, "if only your nephew, the young Viscount, were here—"

"To the deuce with Bentley's nephew!" roars Jack. "I say he shouldn't marry her now, no—not if he were ten thousand times Bentley's nephew, sir—deuce take him!"

"So then," says I, "all our plans are gone astray, and she will have her way and wed this adventurer Tawnish, I suppose?"

"No, no, Dick!" cries Jack; "curse me, am I not her father?"

"And is she not—herself?" says I.

"True!" Jack nodded, "and as stubborn as—as—"

"Her father!" added Bentley. "Why, Jack—Dick—I tell you she's ruled us all with a rod of iron ever since she used to climb up our knees to pull at our wigs with her little, mischievous fingers!"

"Such very small, pink fingers!" says I, sighing. "Indeed we've spoiled her wofully betwixt us."

"Ha!" snorted Jack, "and who's responsible for all this, I say; who's petted and pampered, and coddled and condoned her every fault? Why—you, Dick and Bentley. When I had occasion to scold or correct her, who was it used to sneak behind my back with their pockets bulging with cakes and sticky messes? Why, you, Dick and Bentley!"

"You scold her, Jack?" says Bentley, "yes, egad! in a voice as mild as a sucking dove! And when she wept, you'd frown tremendously to hide thine own tears, man, and end by smothering her with your kisses. And thus it has ever been—for her dead mother's sake!"

"But now," says I after a while, "the time is come to be resolute, for her sake—and her mother's."

"Aye," cries Jack, "we must be firm with her, we must be resolute! Penelope's my daughter and shall obey us for once, if we have to lock her up for a week. I'll teach her that our will is law, for once!"

"You're in the right on 't, Jack," says I, "we must show her that she can't ride rough-shod over us any longer. We must be stern to be kind."

"We must be adamant!" says Bentley, his eyes twinkling.

"We must be harsh," says I, "if need be and—"

But here, perceiving Bentley's face to be screwed up warningly, observing his ponderous wink and eloquent thumb, I glanced up and beheld Penelope herself regarding us from the doorway. And indeed, despite the pucker at her pretty brow, she looked as sweet and fresh and fair as an English summer morning. But Jack, all innocent of her presence, had caught the word from me.

"Harsh!" cries he, thumping the table at his elbow, "I'll warrant me I'll be harsh enough—if 'twas only on account of the fellow's poetry-stuff—the jade! We'll lock her up—aye, if need be, we'll starve her on bread and water, we'll—"

But he got no further, for Penelope had stolen up behind him and, throwing her arms round his neck, kissed him into staring silence.

"Uncle Bentley!" says she, giving him one white hand to kiss, "and you, dear uncle Dick!" and she gave me the other.

"What, my pretty lass!" cries Bentley, rising, and would have kissed the red curve of her smiling lips, but she stayed him with an authoritative finger.

"Nay, sir," says she, mighty demure, "you know my new rule,—from Monday to Wednesday my hand; from Wednesday to Saturday, my cheek; and on Sunday, my lips—and to-day is Tuesday, sir!"

"Drat my memory, so it is!" says Bentley, and kissed her slender fingers obediently, as I did likewise. Hereupon she turns, very high and haughty, to eye Jack slowly from head to foot, and to shake her head at him in dignified rebuke.

"As for you, sir," says she, "you stole away my letter,—was that gentle, was it loving, was it kind? Uncle Bentley—say 'No'!"

"Why—er—no," stammered Bentley, "but you see, Pen—"

"Then, Sir John," she continued, with her calm, reproving gaze still fixed upon her father's face the while he fidgetted in his chair, "then yesterday, Sir John, when I found you'd taken it, and came to demand it back again, you heard me coming and slipped out—through the window, and hid yourself—in the stables, and rode away without even stopping to put on your riding-boots, and—in that terrible old hat! Was that behaving like a dignified, middle-aged gentleman and Justice of the Peace, sir? Uncle Richard, say 'Certainly not!'"

"Well, I—I suppose 'twas not," says I, "but under the circumstances—"

"And now I find you all with your heads very close together, hatching diabolical plots and conspiracies against poor little me—heigho!"

"Nay, Penelope," says Jack, beginning to bluster, "we—I say we are determined—"

"Oh, Sir John," she sighed, "oh, Sir John Chester, 'tis a shameful thing and most ungallant in a father to run off with his daughter's love-letter. Prithee, where is her love-letter? Give her her love-letter—this moment!"

Hereupon Jack must needs produce the letter from his pocket (where he had hidden it) and she (naughty baggage) very ostentatiously set it 'neath the tucker at her bosom. Which done, she nods at each one of us in turn, frowning a little the while.

"I vow," says she, tapping the floor with the toe of her satin shoe, "I could find it in my heart to be very angry with you—all of you, if I didn't—love you quite so well. So, needs must I forgive you. Sir John dear, stoop down and let me straighten your wig—there! Now you may kiss me, sir—an' you wish."

Hereupon Jack kissed her, of course, and thereafter catching sight of us, frowned terrifically.

"Now, look'ee here, Pen—Penelope," says he, "I say, look'ee here!"

"Yes, Sir John dear."

"I—that is to say—we," began Jack, "for Dick and Bentley are one with me, I say that—that—er, I say that—what the devil do I mean to say, Dick?"

"Why, Pen," I explained, "'tis this stranger—this—er—"

"Tawnish!" says Bentley.

"Aye, Tawnish!" nodded Jack. "Now heark'ee, Pen, I repeat—I say, I repeat—"

"Very frequently, dear," she sighed. "Well?"

"I say," continued Jack, "that I—we—utterly forbid you to see or hear from the fellow again."

"And pray, sir, what have you against him?" says she softly,—only her slender foot tapped a little faster.

"Everything!" says Jack.

"Which is as much as to say—nothing!" she retorted.

"I say," cried Jack, "the man you come to marry shall be a man and not a mincing exquisite with no ideas beyond the cut of his coat."

"And," says I, "a man of position, and no led-captain with an eye to your money, or needy adventurer hunting a dowry, Pen."

"Oh!" she sighed, "how cruelly you misjudge him! And you, Uncle Bentley, what have you to say?"

"That whoso he be, we would have him in all things worthy of thee, Pen."

"Aye!" nodded Jack, "so my lass, forego this whim—no more o' this Tawnish fellow—forget him."

"Forget!" says she, "how lightly you say it! Oh, prithee don't you see that I am a child no longer—don't you understand?"

"Pooh!" cries Jack. "Fiddle-de-dee! What-a-plague! This fellow is no fit mate for our Pen, a stranger whom nobody knows! a languid fop! a pranked-out, patched and powdered puppy-dog! So Penelope, let there be an end on't!"

Pen's little foot had ceased its tattoo, but her eyes were bright and her cheeks glowed when she spoke again.

"Oh!" says she, scornfully. "Oh, most noble, most fair-minded gentlemen—all three of you, to condemn thus, out of hand, one of whom you know nothing, and without allowing him one word in his own behalf! Aye, hang your heads! Oh, 'tis most unworthy of you—you whom I have ever held to be in all things most just and honourable!"

And here she turned her back fairly upon us and crossed to the window, while we looked at one another but with never a word betwixt us; wherefore she presently went on again.

"And yet," says she, and now her voice was grown wonderfully tender, "you all loved the mother I never knew—loved her passing well, and, for her sake, have borne with my foolish whims all these years, and given me a place deep within your hearts. And because of this," says she, turning and coming back to us, "yes, because of this I love thee, Uncle Dick!" Here she stooped and kissed me (God bless her). "And you too, Uncle Bentley!" Here she kissed Bentley. "And you, dear, tender father!" Here she kissed Jack. "Indeed," she sighed, "methinks I love you all far more than either of you, being only men, can ever understand. But because I am a woman, needs must I do as my heart bids me in this matter, or despise myself utterly. As for the worth of this gentleman, oh! think you I am so little credit to your upbringing as not to know the real from the base? Ah! trust me! And indeed I know this for a very noble gentleman, and what's more, I will never—never—wed any other than this gentleman!" So saying, she sobbed once, and turning about, sped from the room, banging the door behind her.

Hereupon Jack sighed and ruffled up his wig, while Bentley, lying back in his chair, nodded up at the ceiling, and as for myself I stared down at the floor, lost in sombre thought.

"Well," exclaimed Jack at last, "what the devil are you shaking your heads over? Had you aided me just now instead of sitting there mumchance like two graven images—say like two accursed graven images—"

"Why," retorted Bentley, "didn't I say—"

"Say," cries Jack, "no sooner did you clap eyes on her than it's 'My sweet lass!' 'My pretty maid!' and such toys! And after all your talk of being 'harsh to be kind!' Oh, a cursed nice mess you've made on't betwixt you. Lord knows I tried to do my best—"

"To be sure," nodded Bentley, "'Come let me straighten your wig' says she, and there you sat like—egad, like a furious lamb!"

"Jack and Bentley," says I, "'tis time we realized that our Pen's a woman grown and we—old men, though it seems but yesterday we were boys together at Charterhouse. But the years have slipped away, as years will, and everything is changed but our friendship. As we, in those early days lived, and fought, and worked together, so we loved together, and she—chose Jack. And because of our love, her choice was ours also. And in a little while she died, but left us Pen—to comfort Jack if such might be, and to be our little maid. Each day she hath grown more like to what her sweet mother was, and so we have loved her—very dearly until—to-day we have waked to find our little maid a woman grown—to think, and act, and choose for herself, and we—old men."

And so I sighed, and rising crossed to the window and stood there awhile.

"Lord!" says Bentley at last, "how the years do gallop upon a man!"

"Aye!" sighed Jack, "I never felt my age till now."

"Nor I!" added Bentley.

"And now," says Jack, "what of Raikes; have you seen aught of him lately?"

"No, Jack."

"But I met Hammersley this morning," says Bentley, "and he was anxious to know when the—the—"

"Meeting was likely to take place?" put in Jack, as he paused; "Purdy tells me I shan't be able to use this foot of mine for a month or more."

"That will put it near Christmas," added Bentley.

"Yes," nodded Jack, "I think we could do no better than Christmas Day."

"A devilish strange time for a duel," says Bentley, "peace on earth, and all that sort of thing, you know."

"Why, it's Pen," says Jack, staring hard into the fire, "she will be at her Aunt Sophia's then, which is fortunate on the whole. I shouldn't care for her to see me—when they bring me home."

For a long time it seemed to me none of us spoke. I fumbled through all my pockets for my snuff-box without finding it (which was strange), and looking up presently, I saw that Bentley had upset his wine, which was trickling down his satin waistcoat all unnoticed.

"Jack," says I at last, "a Gad's name, lend me your snuff-box!"

"And now," says he, "suppose we have a hand at picquet."[Pg 81]

Chapter Three

Of a Flight of Steps, a Stirrup, and a Stone

Autumn, with its dying flowers and falling leaves, is, to my thinking, a mournful season, and hath ever about it a haunting melancholy, a gentle sadness that sorts very ill with this confounded tune of "Lillibuleero," more especially when whistled in gusts and somewhat out of key.

Therefore, as we walked along towards the Manor on this November afternoon, I drew my arm from Bentley's and turned upon him with a frown:

"Why in heaven's name must you whistle?" I demanded.

"Did I so, Dick? I was thinking."

"Of what, pray?"

"Of many things, man Dick, but more particularly of my nephew."

"Ah!" says I scornfully, "our gallant young Viscount! our bridegroom elect who—ran away!"

"But none the less," added Bentley, stoutly, "a pretty fellow with a good leg, a quick hand and a true eye, Dick—one who can tell 'a hawk from a hern-shaw' as the saying is."

"Which I take leave to doubt," says I, sourly, "or he would have fallen in with our wishes and married Pen a year ago, instead of running away like a craven fool!"

"But bethink you, Dick," says Bentley flushing, "he had never so much as seen her and, when he heard we were all so set on having him married, he writ me saying he 'preferred a wife of his own choosing' and then—well, he bolted!"

"Like a fool!"

"'Twas very natural," snorted Bentley, redder in the face than ever. "And what's more, he's a fine lad, a lovable lad, and a very fine gentleman into the bargain, as you will be the first to admit when—" but here Bentley broke off to turn and look at me mighty solemn all at once: "Dick," says he, "do you think young Raikes is so great a swordsman as they say?"

"Yes," I answered bitterly, "and that's why I grieve for our poor Jack."

"Jack?" says Bentley, staring like a fool, "Jack—ah yes, to be sure—to be sure."

"I tell you, Bentley," I continued, impressively, "so sure as he crosses swords with the fellow, Jack is a dead man."

"Humph!" says Bentley, after we had gone some little way in silence. "Man Dick, I'm greatly minded to tell thee a matter."

"Well?" I enquired, listlessly.

"But on second thoughts, I won't, Dick," says he, "for 'silence is golden,' as the saying is!"

"Why then," says I, "go you on to the house; I'm minded to walk in the rose-garden awhile," for I had caught the flutter of Pen's cloak at the end of one of the walks.

"Walk?" repeated Bentley, staring. "Rose-garden? But Jack will be for a game of picquet—"

"I'll be with you anon," says I, turning away.

"Hum!" says Bentley, scratching his chin, and presently sets off towards the house, whistling lustily.

I found Penelope in the yew-walk, leaning against the statue of a satyr. And looking from the grotesque features above to the lovely face below, I suddenly found my old heart a-thumping strangely—for beside this very statue, in almost the same attitude, her mother had once stood long ago to listen to the tale of my hopeless love. For a moment it almost seemed that the years had rolled backward, it almost seemed that the thin grey hair beneath my wig might be black once more, my step light and elastic with youth. Instinctively, I reached out my hands and took a swift step across the grass, then, all at once she looked up, and seeing me, smiled.

My hands dropped.

"Penelope," I said.

"Uncle Dick," says she, her smile fading, "why, what is it?"

"Naught, my dear," says I, trying to smile, "old men have strange fancies at times—"

"Nay, but what was it?" she repeated, catching my hands in hers.

"Child," says I, "child, you are greatly like what your mother was before you."

"Am I?" says she very low, looking at me with a new light in her eyes. Then she leaned suddenly forward and kissed me.

"Why, Pen!" says I, all taken aback.

"I know," she nodded, "on Monday my hand, on Wednesday my cheek, and on Sunday my lips—"

"And to-day is Friday!"

"What if it is, sir," says she, tossing her head, "I made that rule simply for peace and quietness sake; you and Uncle Bentley were forever pestering me to death, you know you were."

"Were we?" says I, chuckling, "well, I'm one ahead of him to-day, anyhow, Pen."

Talking thus, we came to the rose-garden (Pen's special care) and here we must needs fall a-sorrowing over the dead flowers.

"And yet," says Pen, pausing beside a bush whereon hung a few faded blooms, "all will be as sweet, and fresh, and glorious again next year."

"Yes," I answered, heavily, "next year." And I sighed again, bethinking me of the changes this next year must bring to all of us.

"Tell me, Uncle Dick," says she, suddenly, laying a hand on either of my shoulders, "how did father hurt his foot?"

"Why, to be sure," says I, readily, "'twas an accident. You must know 'twas as we came down the steps at 'The Chequers', Pen; talking and laughing, d'ye see, he tripped and fell—caught his spur, I fancy."

"But he wore no spurs, Uncle Dick," says she, mighty demure.

"Oh—why—didn't he so, Pen?" says I, a little hipped. "Well, then he—er—just—tripped, you know—fell, you understand."

"On the steps, Uncle Dick?"

"Aye, on the steps," I nodded.

"Prithee did he fall up the steps or down the steps, Uncle Dick?"

"Down, Pen, down; he simply tripped down the steps and—and there you have it."

"But prithee Uncle Dick—"

"Nay, nay," says I, "the game waits for me, Pen—I must go."

But at this moment, as luck would have it, Bentley reappeared, nor was I ever more glad to see him.

"Aha, man Dick," cries he, wagging his finger at me. "Walk in the rose-garden, was it? Oh, for shame, to so abuse my confidence—Dick, I blush for thee; and Jack's a roaring for thee, and the game waits for thee; in a word—begone! And to-day, Pen," says he, as I turned away, "to-day is Friday!" and he stooped and kissed her pretty cheek.

I had reached the terrace when I stopped all at once and, moved by a sudden thought, I turned about and hurriedly retraced my steps. They were screened from sight by one of the great yew hedges, but as I approached I could hear Bentley's voice:

"His horse?" says Bentley.

"Yes," says Pen, "and Saladin's such a quiet old horse as a rule!"

"But what's his horse got to do with it?" says Bentley.

"Why, you were there, Uncle Bentley. Saladin jibbed, didn't he, just as father had one foot in the stirrup ready to mount?"

"Oh! Ha! Hum!" says Bentley. "Did Jack tell you all that, Pen?"

"Who else?" says she, "'twas you caught his bridle, wasn't it?"

"I? Hum! The bridle?" says Bentley, "why—egad, Pen—"

"And Uncle Dick caught father as he fell," she continued.

"Did Jack tell thee all that?" says Bentley.

"How should I know else?" says she.

"Lord!" says Bentley.

"And 'twas you caught the bridle, now, wasn't it?" says she, carelessly.

"Why—er—since you mention it, —yes—I suppose so," mumbled Bentley, "oh, yes, certainly I caught the bridle—surprisingly agile in one o' my size, Pen, eh? But egad, the game waits—I must be off, but a kiss first—for saving thy father for thee, Pen."

Waiting for no more, I turned and set off towards the house, but as I once more reached the terrace, up comes Bentley behind me, whistling lustily as usual.

"Why Dick," says he, "where have you sprung from?"

"Bentley," says I, shaking my head, "it's in my mind you've been a vasty fool!"

"For what, Dick?"

"For catching that bridle!" says I. "Why on earth couldn't you be content to let him trip down the steps as we agreed a week ago?"

"Why then, what of Jack's story of Saladin's jibbing—though strike me purple, Dick, if I thought he had enough imagination."

"Do you think he did tell her so?" says I.

"To be sure he did, Dick, unless—"

"Humph!" says I, "let's go and ask him."

Side by side we entered the great hall, and side by side we came to the door of the library; now the door was open, and from within came the sound of Jack's voice.

"I tell thee 'twas nought but a stone, Pen," he was saying, "I say, an ordinary, loose cobble-stone! Good Gad, madam, and why shouldn't it be a cobble-stone? Gentlemen are forever twisting their ankles on cobble-stones! I tell you—" Hereupon Bentley threw open the door, but I entered first.

"No, no, Jack!" I cried, "'twas down the steps—you tripped down the steps at 'The Chequers,' you know you did!"

"Nay, 'twas Saladin jibbed,—don't you remember?" says Bentley.

"Why, Dick and Bentley!" cries Jack, staring from one to the other of us, "what a plague's all this? Don't I know how I hurt my own foot? I say 'twas a cobble-stone, and a cobble-stone it shall be. Lord! how could ye try to fill our maid's pretty head with such folly? Shame on ye both! Why not stick to the truth—and my cobble-stone?"

"And now, dear Sir John," says Pen, very soft and demure, "pray tell me—how did you hurt your foot?"

"Hey—what?" spluttered Jack, "don't I tell you—"

"A flight of steps, a stirrup, and a stone!" sighed Pen, shaking her head at us each in turn.

"Now look'ee, Pen," says Jack, trying to bluster, "I say I'm not to be badgered and brow-beaten by a slip of a girl—I say I'm not, by heaven!"

"Oh, my dears, my dears!" sighed Pen, reprovingly, "Isn't it time you learned that you can keep few—very few secrets from me, who understand you all so well because I love you all so well? I have been your playfellow and companion so long that, methinks, I know you much better than you know yourselves; I, who have had my word in all your councils? How foolish then to think to put me off with such flimsy stories. Of course I shall find out all about it, sooner or later, I always do. Yes, I shall, even if I must needs hide in corners sirs, and hearken at keyholes, and peep and pry—so I warn you." And with this, she nodded and turned and left us to stare blankly at one another.

"That settles it!" said Bentley, gloomily, "she'll no more swallow thy cobble-stone than Dick's flight of steps, Jack. She'll know the truth before the week is out!"

"The minx!" cried Jack, "the jade!" And with the word he snatched off his wig and hurled it into a corner.

"Jack," says I, "what's to be done?"

"Done?" he roared, "I'll pack her off to her Aunt Sophia to-morrow!"

"Aye," says Bentley, "but—will she go?"

"Bentley," says Jack, "I'll thank you to reach me my wig!"[Pg 100]

Chapter Four

Of how We fell in with a Highwayman at

the Cross Roads

Myself and Bentley were returning from another dog-fight. This time my dog had lost (which was but natural, seeing its very unfit condition, though to be sure it looked well enough at a glance). Alas! the sport is not what it was in my young days, when rogues can so put off a sick dog upon the unsuspecting. Methinks 'tis becoming a very brutal, degrading practice—have determined to have done with dog-fighting once and for all. Bentley was in a high good humour (as was but to be expected, seeing he had won nigh upon two hundred guineas of me), but then, as I have said, Bentley never wins but he must needs show it.

"By the way," said he, breaking off in the middle of the air he was humming, "did you see him at the fight?"

"Him?" says I.

"Raikes," nodded Bentley. "Man Dick, I never see the fellow but my fingers itch for his throat. I heard some talk that he had won a thousand or so from young Vesey, by this one bout alone."

"Humph!" says I.

"Come, Dick," says Bentley, "let's get on; he cannot be so very far behind, and I have no stomach for his society—I'll race you to the cross roads for fifty."

"I'll hurry myself for no such fellow as Raikes!" says I.

"Nor fifty guineas?"

"No," says I, "nor fifty guineas!"

Whereupon, Bentley yielding to my humour, we rode on with never a word betwixt us. It lacked now but a short three weeks to Christmas, and every day served but to bring Jack nearer to his grave, and add a further load to that which pressed upon my heart. At such times the thought of Pen, and the agony I must see in her eyes so soon, drove me well-nigh frantic. In this rough world men must be prepared for fortune's buffets—and shame to him that blenches, say I—but when through us Fate strikes those we fain would shelter, methinks it is another matter. Thus, had Jack proved coward, I for one should have rejoiced for Pen's sake, but as it was, no power on earth could stay the meeting, and this Christmas would bring her but anguish, and a great sorrow. With all these thoughts upon my mind I was very silent and despondent—and what wonder! As for Bentley, he, on the contrary, manifested an indifference out of all keeping with his character, an insensibility that angered and disgusted me not a little, but surprised and pained me, most of all.

So it was in moody silence that we walked our horses up the hill where the beacon stands, and were barely on top, when we heard the sound of rapidly approaching hoofs behind us, and a few minutes later Sir Harry Raikes with his friend, Captain Hammersley, galloped up.

Hereupon Bentley, in his usual easy, inconsequent fashion, fell into conversation with them, but as for me, having bowed in acknowledgment of their boisterous salutation, I relapsed once more into gloomy thought. Little by little however, it became apparent to me that for some reason I had become a mark for their amusement; more than once I caught them exchanging looks, or regarding me from the corners of their eyes in such fashion as set my ears a-tingling. The Captain was possessed of a peculiarly high-pitched, falsetto laugh, which, recurring at frequent intervals (and for no reason as I could see), annoyed me almost beyond bearing. But I paid no heed, staring straight before me and meditating upon a course of action which had been in my head for days past—a plan whereby Jack's duel might be prevented altogether, and our sweet maid shielded from the sorrow that must otherwise blight her life so very soon. As I have said before, there was a time, years ago, when I was accounted a match for any with the small-sword, and though a man grows old he can never forget what he has learned of the art. I had, besides, seen Raikes fight on two or three occasions, and believed, despite the disparity of our years, that I could master him. If on the other hand I was wrong, if, to put it bluntly, he should kill me, well, I was a very lonely man with none dependent upon me, nay, my money would but benefit others the sooner; moreover, I was a man of some standing, a Justice of the Peace, with many friends in high authority, both in London and the neighbourhood, who I know would raise such an outcry as would serve to rid the county of Raikes once and for all. And a better riddance could not well be imagined.

Thus, I argued, in either case my object could not fail, and therefore I determined on the first favourable opportunity to put the matter to a sudden issue. Presently the road narrowed so that we were forced to ride two abreast, and I noticed with a feeling of satisfaction that Raikes purposely reined in so as to bring himself beside me.

"By the way, Sir Richard," says he carelessly, "what of Jack Chester?"

"You possibly allude to my friend Sir John Chester," I corrected.

"To be sure," he answered, staring me in the eyes—"to be sure—Jack Chester." Hereupon the Captain giggled. "They tell me his leg yet troubles him," continued Raikes, seeing I was silent.

"'Tis nearly well," says Bentley, over his shoulder, and at the same time I noticed his great mare began to edge closer to the Captain's light roan.

"Can it be possible?" cried Raikes, in mock surprise. "On my soul, you astonish me!" At this the Captain screeched with laughter again, yet he broke off in the middle to curse instead, as his horse floundered into the ditch.

"Pink my immortal soul, sir!" says he, as he got down to pick up his hat, "but I verily believe that great beast of yours is gone suddenly mad!" And indeed, Bentley's mare was sidling and dancing in a manner that would seem to lend truth to the words.

"No," says Bentley, very solemn, "she has an objection to sudden noises—'twas your laugh frightened her belike."

The Captain muttered a curse or two, wiped the mud from his hat, and climbing back into the saddle, we proceeded upon our way.

"Speaking of Jack Chester," began Raikes, but here he was interrupted by Bentley, who had been regarding us for some time with an uneasy eye.

"Gentlemen," says he, pointing to the finger-post ahead of us, "'tis said Sir Charles d'Arcy was stopped at the cross roads yonder by a highwayman, no later than last night, and he swears the fellow was none other than the famous Jerry Abershaw himself, and he is said to be in these parts yet."

"The devil!" exclaimed the Captain, glancing about apprehensively, while I stared at Bentley in surprise, for this was the first I had heard of it. As for Sir Harry Raikes, he dismissed the subject with a careless shrug, and turned his attention to me once more.

"Speaking of Jack Chester," says he, "I begin to fear that leg of his will never mend."

"Ah?" says I, looking him in the eyes for the first time, "yes?"

"Considering the circumstances," he nodded.

"It would seem that your fears were wasted none the less, sir."

"My dear Sir Richard," he smiled, "as I was saying to some one only the other day, an injured arm—or leg for that matter, has often supplied a lack of courage before now."

As he ended, the Captain began to laugh again, but meeting my eye, stopped, for the moment I had waited for had arrived, and I reined round so suddenly as to throw Sir Harry's horse back upon its haunches.

"Damnation!" he cried, struggling with the plunging animal, "are you mad?"

"Do me the favour to dismount," says I, suiting the action to the word, and throwing my bridle to Bentley.

"And what now?" says Raikes, staring.

"You will perceive that the road here is passably even, and the light still fairly good," says I.

"Highly dramatic, on my soul!" he sneered.

"Sir Harry Raikes," says I, stepping up to his stirrup, "you will notice that I have here a sword and a whip—which shall it be?"

The sneer left his lips on the instant, his face as suddenly grew red, and I saw the veins start out on his temples.

"What," cries he, "is it a fight you're after?"

"Exactly!" says I, and laid my hand upon my small-sword; but at this moment Bentley rode betwixt us.

"By God, you don't, Dick!" says he, laying his great hand upon my shoulder.

"By God, but I do!" says I, endeavouring vainly to shake off his grasp.

"Man, Dick," cries he, "you are a madman—and full six inches shorter in the reach! Now I—"

"You!" I broke in, "you are a mountain—besides, the quarrel is mine—come, loose me, Bentley—loose me, I say."

"No! Devil take me—do you think I'll stand by and see you murdered?"

"Bentley," I cried, "if ever you were friend of mine you will free my arm this instant."

All this time Raikes sat regarding us with a look of such open amusement as came nigh driving me frantic.

"Mr. Bentley," says he, with a flourish of his hat, "I fancy 'twould be as well for Sir Richard were I and Captain Hammersley to ride on before, yet do not loose him till I am out of sight, I beg."

"You hear, Bentley?" says I, trembling with passion. "Come—let us go—fool," I whispered under my breath, "for her sake!" Bentley's fingers twitched upon my arm.

"Ah, I thought so!" he nodded.

"Then quick, do as I bid, and get it over."

"On condition that you settle the affair in the meadow yonder—'tis a better place in all respects," says Bentley, under his breath.

"I care not where it be," says I.

"So," sneered Raikes, "you are bent on fighting, then?"

"In the meadow yonder," nodded Bentley, pointing with his whip to a field that lay beyond the narrow stone bridge, some little distance ahead.

"As you will," says Raikes, shrugging his shoulders; "but whatever the consequences, I call you all to witness that Sir Richard's own impulsiveness is entirely to blame."

So, having remounted, we rode forward, Raikes and the Captain leading the way.

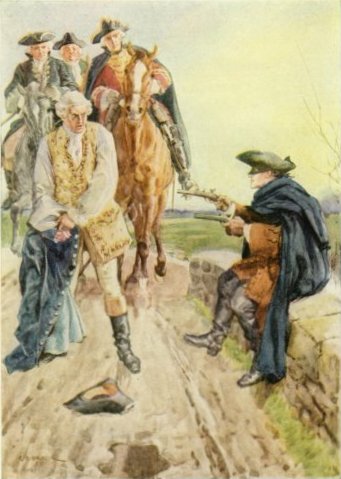

Now as we drew nearer to the bridge I have mentioned, I noticed a solitary figure wrapped in a horseman's cloak who sat upon the coping, seemingly absorbed in watching the flow of the stream beneath. We were almost upon him when he slowly rose to his feet, and as he turned his head I saw that he was masked, and, furthermore, that in either hand he held a long-barrelled pistol.

"Abershaw, by God!" exclaimed the Captain, reining up all of a sudden.

"Stand!" cried a harsh voice, whereupon we all very promptly obeyed with the exception of Raikes, who, striking spurs to his horse, dashed in upon the fellow with raised whip. There was the sound of a blow, a bitter curse, and the heavy whip, whirling harmlessly through the air, splashed down into the stream.

"Ah! would you then?" says the fellow, with the muzzles of the pistols within a foot of Sir Harry's cowering body. "Ah, would you? Curse me, but I've a mind to blow the heart and liver out of you—d'ye take me?"

"I'll see you hanged for this," said Raikes, betwixt his teeth.

"Maybe aye, maybe no," says the fellow, in the same rough yet half-jovial voice, "but for the present come down—get down, d'ye hear?" Muttering oaths, Sir Harry perforce dismounted, and being by this still nearer the threatening muzzles, immediately proceeded to draw out a heavy purse, which he sullenly extended toward the highwayman, who, shifting one pistol to his pocket, took it, weighed it in his hand a moment, and then coolly tossed it over into the stream.

"What the devil!" gasped Raikes, "are you mad?"

"Maybe aye, maybe no," says the fellow, grinning beneath his mask, "but that's neither here nor there, master, the question betwixt us being a coat."

"What coat?" cries Raikes, with a bewildered stare.

"This coat," says the fellow, tapping him upon the arm with his pistol barrel, "and a very passable coat it is—fine velvet, I swear, and as I'm a living sinner, a flowered waistcoat!—come, take 'em off, d'ye hear?"

Very slowly, Sir Harry obeyed, swearing frightfully, while the fellow, sitting upon the parapet of the bridge, swung his legs and watched him.

"Humph!" says he, as if to himself, "buckskin breeches, and boots brand new—burn me!" and then suddenly in a louder tone: "Off with them!"

"What d'ye mean?" snarled Raikes, and his face was murderous.

"What I says," returned the other, with a flourish of his pistols, "such being my natur', d'ye take me? And if the gentleman in the muddy hat moves a finger nearer his barkers, I'll blow his head off—curse me if I won't." Saying which the highwayman began to whistle softly, swinging his legs in time to himself. As for the Captain, the hand which had crept furtively towards his pistols dropped as if it had been shot, and he sat watching the fellow with staring eyes.

And indeed he made a strange, fantastic figure sitting there hunched up in the fading light, with the quick gleam of his ever restless eyes showing through the slits of his hideous half-mask, and the pout of his whistling lips beneath; nay, there was about the whole figure, from the rusty spurs at his heels to the crown of his battered hat, something almost devilish, with an indefinable mockery beyond words.

"Bentley," I whispered, as Raikes slowly kicked off his boots one after the other, "this fellow's a madman beyond a doubt, or we are dreaming." Bentley's reply was something betwixt a groan and a choke, and looking round, I saw that his face was purple.

"Man, don't do that," I cried, "you'll burst a blood-vessel!"

"Come," says the fellow, breaking off his whistle of a sudden, and turning over the garments at his feet with the toe of his boot, "you wouldn't go for to cheat me out of your breeches, would you? Come now, master, off with 'em, I say, for look ye, I mislike to be kept waiting for a thing as I wants—such being my natur', d'ye take me?"

Sir Harry Raikes stood rigid, his face dead white—only his burning eyes and twitching mouth told of the baffled fury that was beyond all words. Twice he essayed to speak and could not—once he turned to look at us with an expression of such hopeless misery and mute appeal as moved even me to pity. As for the highwayman, he began to whistle and swing his legs once more.

"Bentley," says I, "this must go no farther."

"What can we do?" gasped Bentley, and laid his heavy hand upon my arm.

"Come," says the fellow again, rising to his feet.

"No," cries Raikes, in a choking voice, "not for all the devils in hell!"

"I'll count five," grinned the fellow, and he levelled his pistols.

"One!" says he, but Raikes never stirred—"Two," the harsh, inexorable voice went on, "three—four—" There was a sudden wild sob, and Sir Harry Raikes was shivering in his hat and shirt. The highwayman now turned his attention to Raikes's horse—though keeping a wary eye upon us—and having drawn both pistols from their holsters, motioned him to remount. Sir Harry obeyed with never so much as a word; which done, the fellow gave a whistle, upon which a horse appeared from the shadow of the hedge beyond, from whose saddle he took two lengths of cord, and beckoning to the Captain, set him to bind Raikes very securely to the stirrup-leathers. As one in a dream the Captain proceeded about it (bungling somewhat in the operation), but it was done at last.

"Now, my masters," says the fellow briskly, "I must trouble each one of you for his barkers—and no tricks, mark me, no tricks!" With this he nodded to Bentley, who yielded up his weapons after a momentary hesitation, while the Captain seemed positively eager to part with his, and I in my turn was necessitated to do the same.

It may be a matter of wonder to some, that one man could so easily disarm four, but 'tis readily understood if you have looked into the muzzle of a horse-pistol held within a few inches of your head.

Thus, all being completed, the highwayman, having mounted, gave us the word to proceed, Bentley and I riding first, then Raikes and the Captain, and last of all the fellow, pistol in hand. So thus it was, in the dusk of the evening, that we came into Tonbridge Town, with never a word betwixt us—myself silent from sheer amazement, the Captain for reasons of his own, Sir Harry Raikes for very obvious causes, but mostly (as I judge) on account of his chattering teeth, and Bentley because a man cannot whistle "Lillibuleero" beneath his breath and talk at the same time.

Lights were beginning to gleam at windows as we entered the High Street, and here I made sure the highwayman would have left us—but no, on turning my head, there he rode, close behind—his battered hat over his nose, and his pistol in his hand, for all the world as if we were back on the open road rather than the main thoroughfare of a Christian town.

By this time we were become a mark for many eyes; people came running from all sides, the air hummed with voices; shouts were heard, mingled with laughter and jeers, but we rode on, and through it all at a gallop. As we passed "The Chequers" I saw the windows full of faces, and Truscott and Finch with five or six others came running out to stare after us open mouthed. So we galloped through Tonbridge Town, and never drew rein until we were out upon the open road once more. There the fellow stopped us.

"Masters all," says he, "'tis here we part—maybe you'll forget me—maybe not—especially one of you; d'ye take me?" and he pointed to the shivering figure of Raikes. "The wind is plaguily chill I'll allow, but burn me! could I be blamed for that, my masters—what, all silent? Well! Well! Howsomever, give me that trinket, Master—just to show there's no ill-feeling, so to speak; and he indicated a small gold locket that Raikes wore round his neck on a riband, who, without a word, or even looking up, slipped it off and laid it in the other's outstretched hand.

"Well, good-night, my masters, good-night!" says he, in his jovial voice; "maybe we shall meet again, who knows? My best respects to you all—me being respectful by natur'. Good-night." So, with an awkward flourish of his hat, he wheeled his horse and galloped away towards London.[Pg 126]

Chapter Five

Concerning the true Identity of our High-

wayman

'Twas some half-hour later that we found Jack in his library, seated before the fire, his wine at his elbow and Pen at his feet, reading aloud from Mr. Steele's "Tatler."

Upon our sudden appearance Penelope rose, and looked from myself to Bentley a trifle anxiously I thought. Now, as I made my bow to her, I heard Bentley softly begin to whistle "Lillibuleero," and though I had heard him do so many times before, it suddenly struck me that this was the air the highwayman fellow had whistled as he sat swinging his legs upon the bridge.

"Bentley, to-day is Wednesday!" I expostulated, as breaking off in the middle of a bar, he kissed Pen full upon the lips.

"To be sure it is," says he, and kissed her again upon the cheek.

"And ten o'clock," added Jack, "and time all maids were abed."

"Not before I even matters," says I. "I'll give second place to none, least of all Bentley!" And I having kissed her twice—once upon the cheek for Wednesday, and once upon the lips for myself,—she dropped us a laughing courtesy, and with a final good-night kiss for Jack, and a nod to each of us, ran up to bed. But even then Bentley must needs follow her out to the stairs and stand there whispering his nonsense—which goes but to prove the jealous nature of the man!

"What's to do?" says Jack, pushing the wine towards me. "I've sat here with the cards beside me ever since eight o'clock—what's to do?"

"Why, you must know," I began, "we were stopped at the cross roads by a highwayman—myself and Bentley, with Captain Hammersley and Sir Harry Raikes—"

Here Bentley, returning, must needs throw himself into a chair, laughing and choking all at once.

"Raikes—" he gasped,—"in his shirt—by the Lord! Oh, egad, Jack! fluttering in the wind—"

"What in the world!" began Jack, staring. "Is he drunk or mad?"

"As I tell you," says I, loosening Bentley's cravat, "we were stopped by a highwayman—" and forthwith I plunged into an account of the whole matter.

"Egad!" cries Bentley again, breaking in ere I was half done, "here was Dick offering Raikes a choice betwixt his horsewhip and his sword—and he, look you, a full six inches shorter in the reach, while I—"

"You!" says I, "he couldn't help but pink you somewhere or other at the first pass—"

"Well, Raikes was a-sneering as I say," pursued Bentley, "when up comes our highwayman and coolly strips him to his very shirt, Jack—ties him to his horse, and parades him all through Tonbridge—rat me!—and as I tell you, the wind, Jack—'t was cursedly cold, and—and—oh! strike me purple!" Here Bentley choked again, and while I thumped his back, he and Jack rolled in their chairs, and shook the very casements with their laughter.

"His shirt?" gasped Jack at last, wiping his eyes.

"His shirt," groaned Bentley, wiping his.

"Lord!" cries Jack, "Lord! 'twill be the talk of the town," says he, after a while.

"To be sure it will," says Bentley, and hereupon they fell a-roaring with laughter again. For my part, what betwixt thumping Bentley's back and the memory of Christmas morning now so near, I was sober enough.

They were still howling with laughter, and Bentley's face had already assumed a bluish tinge, when the door opened and a servant appeared, who handed a letter to Jack. Still laughing, he took it and broke the seal; at sight of the first words, however, his face underwent a sudden change. "Is the messenger here?" says he, very sharp.

"No, Sir John."