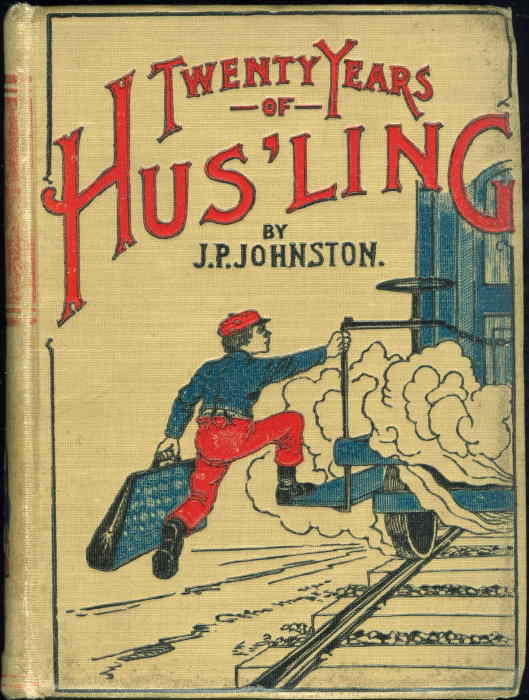

Title: Twenty Years of Hus'ling

Author: J. P. Johnston

Illustrator: W. W. Denslow

Release date: April 18, 2008 [eBook #25087]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Lybarger, Charles Aldarondo, Martin

Pettit and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

Copyright, 1887,

by J. P. Johnston.

All Rights Reserved.

——

Copyright, 1900,

by Thompson & Thomas.

After finishing all that I had intended for publication in my book entitled "The Auctioneer's Guide," I was advised by a few of my most intimate friends to add a sketch of my own life to illustrate what had been set forth in its pages.

This for the sole purpose of stimulating those who may have been for years "pulling hard against the stream," unable, perhaps, to ascertain where they properly belong, and possibly on the verge of giving up all hope, because of failure, after making repeated honest efforts to succeed.

The sketch when prepared proved of such magnitude that it was deemed advisable to make it a separate volume. Hence, the "Twenty Years of Hus'ling."

J. P. Johnston.

Date and place of birth—My Mother's second marriage—A kind step-father—Raising a flock of sheep from a pet lamb—An established reputation—Anxious to speculate—Frequent combats at home—How I conquered a foe—What a phrenologist said—A reconciliation—Breaking steers—Mysterious disappearance of a new fence—My confession—My trip to New York—The transformation scene—My return home with my fiddle.

My mother wishes me to learn a trade—My burning desire to be a live-stock dealer—Employed by a deaf drover to do his hearing—How I amused myself at his expense and misfortune.

Selling and trading off my flock of sheep—Co-partnership formed with a neighbor boy—Our dissolution—My continuance in business—Collapse of a chicken deal—Destruction of a wagon load of eggs—Arrested and fined my last dollar—Arrived home "broke."

Borrowing money from Mr. Keefer—Buying and selling sheep pelts—How I succeeded—A co-partnership in the restaurant business—Buying out my partner—Collapsed—More help from Mr. Keefer—Horses and Patent rights.

Swindled out of a horse and watch—More help from Mr. Keefer—How I got even in the watch trade—My patent right trip to Michigan and Indiana—Its results—How a would-be sharper got come up with.

My new acquaintance and our co-partnership—Three weeks' experience manufacturing soap—The collapse—How it happened—Broke again—More help from Mr. Keefer—A trip to Indiana—Selling prize soap with a circus—Arrested and fined for conducting a gift enterprise—Broke again.

Eleven days on a farm—How I fooled the farmer—Arrived at Chicago—Running a fruit stand—Collapsed—My return home—Broke again—A lucky trade.

Three dollars well invested—Learning telegraphy—Getting in debt—A full-fledged operator—My first telegraph office—Buying and selling ducks and frogs while employed as operator—My resignation—Co-partnership in the jewelry and spectacle business—How we succeeded—Our dissolution.

Continuing the jewelry and spectacle business alone—Trading a watch chain for a horse—Peddling on horseback—Trading jewelry for a harness and buggy—Selling at wholesale—Retiring from the jewelry business.

Great success as an insurance agent—Sold out—Arrived at Chicago—Selling government goods—Acquiring dissipated habits—Engaged to be married—Broke among strangers—How I made a raise—My arrival home.

More help from Mr. Keefer—Off to see my girl—Embarked in the Agricultural-implement business without capital—Married—Sold out—In the grocery business—Collapsed—Running a billiard hall—Collapsed again—Newspaper reporter for a mysterious murder.

More help from Mr. Keefer—Six weeks as a horse-trainer—A mysterious partner—Collapsed—How I made a raise—Home again—Father to a bouncing boy.

Engaged in the Patent-right business—My trade with Brother Long—The compromise—My second trade with a deacon—His Sunday honesty and week-day economy—A new partner—The landlord and his cream biscuits—How we headed him off—A trade for a balky horse—How we persuaded him to go—Our final settlement with the landlord.

Our trip through Indiana—How I fooled a telegraph operator—The old landlord sends recipe for cream biscuit—Our return to Ohio—Becoming agents for a new patent—Our valise stolen—Return to Ft. Wayne—Waiting six weeks for Patent-right papers—Busted—Staving off the washerwoman for five weeks—"The Kid" and 'de exchange act'—How the laundry woman got even with us—The landlord on the borrow—How we borrowed of him—Replenishing our wardrobe—Paying up the hotel bill.

Our visit to La Grange, Ind.—Traded for a horse—Followed by an officer, with a writ of replevin—Putting him on the wrong scent—His return to the hotel—The horse captured—Broke again—How I made a raise.

Arriving at Elmore, Ohio, stranded—Receiving eight dollars on a Patent right sale—Dunned in advance by the landlord—Changing hotels—My visit to Fremont—Meeting Mr. Keefer and borrowing money—Our visit to Findlay—A big deal—Losing money in wheat—Followed by officers with a writ of replevin—Outwitting them—A four-mile chase—Hiding our rig in a cellar.

Visiting my family at Elmore—How we fooled a detective—A friend in need—Arriving at Swanton, Ohio, broke—How I made a raise—Disguising my horse with a coat of paint—Captured at Toledo—Selling my horse—Arrived home broke.

Mr. Keefer called from home—My mother refuses me a loan—Peddling furniture polish on foot—Having my fortune told—My trip through Michigan—Arrested for selling without license—"It never rains but it pours"—Collapsed—A good moral—Making a raise.

My co-partnership with a Clairvoyant doctor—Our lively trip from Ypsilanti to Pontiac, Michigan—Poor success—The doctor and his Irish patient—My prescription for the deaf woman—Collapsed, and in debt for board.

Engaged to manage the hotel—The doctor my star boarder—Discharging all the help—Hiring them over again—The doctor as table waiter—The landlady and the doctor collide—The arrival of two hus'lers—How I managed them—The landlady goes visiting—I re-modeled the house—My chambermaid elopes—Hiring a Dutchman to take her place—Dutchy in disguise—I fooled the doctor—Dutchy and the Irish shoemaker.

The doctor swindled—How we got even—Diamond cut diamond—The doctor peddling stove-pipe brackets—His first customer—His mishap and demoralized condition—The doctor and myself invited to a country dance—He the center of attraction—The doctor in love with a cross-eyed girl—Engaged to take her home—His plan frustrated—He gets even with me—We conclude to diet him—The landlady returns—Does not know the house.

Out of a position—Moved to Ann Arbor—How I made a raise—A return to furniture polish—Selling experience—Hauling coke—My summer clothes in a snow-storm—A gloomy Christmas—An attack of bilious fever—Establishing an enforced credit—The photograph I sent my mother—Engaged as an auctioneer at Toledo, Ohio—My first sale.

A successful auctioneer—Playing a double role—Illustrating an auction sale.

My employer called home—I continue to hus'le—An auctioneering co-partnership—Still in a double role—A neat, tidy, quiet boarding-house—We move to a hotel—A practical joke—Auctioneering for merchants—Making a political speech—Getting mixed.

I continue to sell for merchants—Well prepared for winter—Trading a shot-gun for a horse and wagon—Auctioneering for myself—Mr. Keefer needing help—How I responded—Turning my horse out to pasture—Engaged to sell on commission—How I succeeded—Out of a job—Busted—How I made a raise—A return to the Incomprehensible—Peddling with a horse and wagon—Meeting an old friend—Misery likes company—We hus'le together—Performing a surgical operation—A pugilistic encounter—Our Wild-west stories—Broke again—A hard customer—Another raise.

Helping a tramp—We dissolve partnership—My auction sale for the farmer—How I settled with him—I resume the auction business for myself—My horse trade—I start for Michigan.

Auctioneering at the Michigan State Fair—Three days' co-partnership with a showman—My partner's family on exhibition—Our success—Traveling northward—Business increases—Frequent trades in horses and wagons—The possessor of a fine turn-out—Mr. Keefer again asks assistance—How I responded—Traveling with an ox-team and cart—A great attraction—Sold out—Traveling by rail—My return to Ohio—Meeting the clairvoyant doctor—How I fooled him—Quail, twelve dollars a dozen—The doctor loses his appetite.

A co-partnership formed in the auction business—How it ended—A new friend—His generosity—Exhibiting a talking machine—It failed to talk—How I entertained the audience—In the role of a Phrenologist.

In the auction business again—A new conveyance for street sales—My trip through the lumber regions—A successful summer campaign—A winter's trip through the south—My return to Grand Rapids, Mich.—A trip to Lake Superior—Selling needles as a side issue—How I did it—State license demanded by an officer—How I turned the tables on him—Buying out a country store—A great sale of paper-cambric dress patterns—A compromise with the buyers—My return to Chicago—Flush and flying high.

Buying out a large stock of merchandise—On the road again—Six weeks in each town—Muddy roads and poor trade—Closing out at auction—Saved my credit but collapsed—Peddling polish and jewelry—Wholesaling jewelry—Fifty dollars and lots of experience my stock in trade—Tall "hus'ling" and great success—An offer from a wholesale jewelry firm—Declined with thanks—Hus'ling again—Great success.

Robbed of a trunk of jewelry—Only a small stock left—A terrible calamity—Collapsed—An empty sample-case my sole possession—Peddling polish again—Making a raise—Unintentional generosity breaks me up—Meeting an old partner—The wholesaler supplies me with jewelry—Hus'ling again with great success—Making six hundred dollars in one day—My health fails me—I return to Ohio—A physician gives me but two years to live—How I fooled him.

A friend loans me twenty-five dollars—My arrival in Chicago—Forty dollars' worth of goods on credit—I leave for Michigan—Effecting a sale by stratagem—Great success during the summer—Enforcing a credit—Continued success—Opening an office in the city—Paying my old debts, with interest—My trip to New York—Buying goods from the manufacturers—My return to Chicago—Now I do hus'le—Immense success.

Employing traveling salesmen—Depression in trade—Heavily in debt—How I preserved my credit—I take to the road again—Traveling by team—Deciding a horse-trade—My book-keeper proposes an assignment—I reject the proposition—Collecting old debts by stratagem.

Another horse trade—A heavy loss—Playing detective—My visit home—A retrospect—Calling in my agents—A new scheme—It's a winner—Mr. Keefer and my mother visit Chicago—His verdict, "It does beat the devil."

I was born near Ottawa, Illinois, January 6th, 1852, of Scotch-Irish descent. My great-great-grandfather Johnston was a Presbyterian clergyman, who graduated from the University of Edinburg, Scotland. My mother's name was Finch. The family originally came from New England and were typical Yankees as far as I have been able to trace them. My father, whose full name I bear, died six months previous to my birth. When two years of age my mother was married to a Mr. Keefer, of Ohio, a miller[Pg 14] by trade and farmer by occupation. Had my own father lived he could not possibly have been more generous, affectionate, kind-hearted and indulgent than this step-father.

And until the day of his death, which occurred on the 10th of July, 1887, he was always the same. This tribute is due him from one who reveres his memory.

He had a family of children by his former wife, the youngest being a year or two older than myself. Two daughters were born of this marriage.

A mixed family like the Keefer household naturally occasioned more or less contention. More especially as the neighborhood contained those who took it upon themselves to regulate their neighbors' domestic affairs in preference to their own.

Consequently, in a few years, Mr. Keefer was severely criticised for not compelling me to do more work on the farm, and for the interest he took in schooling me.

As for myself, had I been hanged or imprisoned as often as those neighbors prophesied I would be, I would have suffered death and loss of freedom many times.[Pg 15]

The farm life was distasteful to me from my earliest recollection. I cannot remember ever having done an hour's work in this capacity except under protest.

From this fact I naturally gained the reputation for miles around, of being the laziest boy in the country, with no possible or probable prospect of ever amounting to anything.

But they failed to give me credit for the energy required to walk three miles night and morning to attend the village school, which afforded better advantages than the district school.

When but a small lad my step-father gave me a cosset lamb which I raised with a promise from him to give me half the wool and all of the increase.

This, in a few years, amounted to a flock of over one hundred sheep. The sale of my share of the wool, together with the yield from a potato patch, which was a yearly gift from Mr. Keefer, was almost sufficient to clothe me and pay my school expenses.

I should here add, that the potatoes above mentioned were the product of the old gentleman's labor in plowing, planting, cultivating, digging and marketing.[Pg 16]

While I was expected to do this work, I was seldom on hand except on the day of planting to superintend the job and see that the potatoes were actually put into the ground, and again on market day to receive the proceeds. During all my life on the farm, one great source of annoyance and trouble to my step-father was my constant desire to have him purchase everything that was brought along for sale, and to sell everything from the farm that was salable.

In other words, I was always anxious to have him go into speculation. I could not be too eager for a horse trade or the purchase of any new invention or farm implement that had the appearance of being a labor-saving machine.

Even the advent of a lightning-rod or insurance man delighted me, for it broke the monotony and gave me some of the variety of life.

The rapid growth and development of my flock of sheep were partially due to my speculative desires. I was persistent in having them gratified, and succeeded, by being allowed the privilege of selling off the fat wethers whenever they became marketable, and replacing them with young ewes, which increased rapidly. These could be bought for much less than the wethers would sell for.[Pg 17]

My step-father was a man of more than ordinary common sense, and often suggested splendid ideas, but was altogether too cautious for his own good, and too slow to act in carrying them out.

While he and I got along harmoniously together, I am forced to admit that my mother and myself had frequent combats.

There, perhaps, was never a more affectionate, kind-hearted mother than she, and I dare say but few who ever possessed a higher-strung temper or a stronger belief in the "spare the rod and spoil the child" doctrine. At least, this was my candid, unprejudiced belief during those stormy days. Why, I had become so accustomed to receiving my daily chastisement, as to feel that the day had been broken, or something unusual had happened, should I by chance miss a day.

The principle difficulty was, that I had inherited a high-strung, passionate temper from my mother, and a strong self-will from my father, which made a combination hard to subdue. In my later days I have come to realize that I must have tantalized and pestered my mother beyond all reason, and too often, no doubt, at times when[Pg 18] her life was harassed, and her patience severely tried by the misconduct of one or more of her step-children, who, by the way, I never thought were blessed with the sweetest of all sweet tempers, themselves. At any rate, whenever I got on the war path, I seldom experienced any serious difficulty in finding some one of the family to accommodate me. Notwithstanding, I usually "trimmed" them, as I used to term it, to my entire satisfaction, and no matter whether they, or I were to blame, it was no trouble for them to satisfy my mother that I was the guilty one, despite my efforts to prove an "alibi." For this I was sure to be punished, as I was also for every fight I got into with the neighbor boys, whose great stronghold was to twit me of being "lazy and red-headed."

I was, however, successful at last in convincing my mother that those lads whom I was frequently fighting and quarreling with, were taking every advantage of her action in flogging me every time I had difficulty with them. They could readily see and understand that I was more afraid of the "home rule" than I was of them, and would lose no opportunity to say and do things to provoke me.

One day I came home from school at recess in the afternoon, all out of sorts, and greatly incensed at one of the boys who was two years older than myself, and who had been, as I thought, imposing upon me. I met Mr. Keefer at the barn, and declared right there and then that I would never attend school another day, unless I could receive my parents' full and free consent to protect myself, and to go out and fight that fellow as he passed by from school that evening.

"Do you think you can get satisfaction?" he asked.

"I am sure I can," I answered.

"Well, then," he said, "I want you to go out and flog him good this evening, and I'll go along and see that you have fair play."

"All right, I'll show you how I'll fix him," I answered.

About fifteen or twenty minutes later Henry and one of his chums came from school to our barn-yard well for a pail of water.

I came to the barn door just in time to see them coming through the gate. Mr. Keefer's consent that I should "do him up" gave me courage[Pg 20] to begin at once. I went to the pump, and throwing my cap on the ground, said:

"See here, my father tells me to trim every mother's son of you that twits me of being lazy and red-headed. Now, I'm going to finish you first."

He was as much scared as he was surprised.

I buckled into him, and kick, bite, scratch, gouge, pull hair, twist noses, and strike from the shoulder were the order of the day. I felt all-confident and sailed in for all I was worth, and finished him in less than three minutes, to the evident satisfaction of Mr. Keefer, whom, when the fight was waxing hot, I espied standing on the dunghill with a broad smile taking in the combat. I had nearly stripped my opponent of his clothing, held a large wad of hair in each hand, his nose flattened all over his face, two teeth knocked down his throat, his shins skinned and bleeding, and both eyes closed. After getting himself together he started down our lane, appearing dazed and bewildered. I first thought he was going to a stone pile near by, but as he passed it I began to realize his real condition, when I hurried to his rescue and led him back[Pg 21] to the water trough, and there helped to soak him out and renovate him. After which his comrade returned to school alone with the water, and he proceeded homeward.

After that I had no serious trouble with those near my own age, as it was generally understood and considered that I had a license to fight and a disposition to do so when necessary to protect my own rights.

When my mother heard of this she said I was a regular "tough."

Mr. Keefer said I could whip my weight in wild cats anyhow.

She said I deserved a good trouncing.

He said I deserved a medal and ought to have it.

My mother never seemed to understand me or my nature until the timely arrival of an agent selling patent hay-forks, who professed to have a knowledge of Phrenology, Physiognomy, and human nature in general. In course of a conversation relative to family affairs, my mother remarked that, with but one exception, she had no trouble in managing and controling her children. He turned suddenly to me and said, "I see, this is the one."

At this he called me to him and began a delineation of my character. The very first thing he said was:

"You can put this boy on a lone island with nothing but a pocket knife, and he will manage to whittle himself away."

From this, he went on to say many more good things for me than bad ones, which, of course, gratified me exceedingly.

But it was hot shot for others of the family who were present, and who had never lost an opportunity to remind me of my future destiny.

This gentleman said to my mother, that the principle trouble was her lack of knowledge of my disposition. That if she would shame me at times when I was unruly, and make requests instead of demands when she wanted favors from me, and above all, never to chastise me, she would see quite a change for the better.

He also ventured the remark that some day, under the present management, the boy would pack up his clothes, leave home, and never let his whereabouts be known.

This opened my mother's eyes more than all else he had said, for I had often threatened to do this very thing. In fact I had once been thwarted[Pg 23] by her in an effort to make my escape, which would have been accomplished but for my anxiety to get possession of "the old shot gun," which I felt I would need in my encounter with Indians, and killing bear and wild game. I might add that one of our neighbor boys was to decamp with me, and the dime novel had been our guide.

From this time on there was a general reformation and reconciliation, and my only regrets were that "hay forks" hadn't been invented several years before, or at least, that this glorious good man with his stock of information hadn't made his appearance earlier.

The greatest pleasure of my farm life and boyhood days was in squirrel hunting and breaking colts and young steers.

My step-father always said he hardly knew what it was to break a colt, as I always had them under good control and first-class training by the time they were old enough to begin work.

Whenever I was able to match up a pair of steer calves, I would begin yoking them together before they were weaned. I broke and raised one pair until they were four years old, when Mr. Keefer sold them for a good round sum. I shall never forget an incident that occurred, about the[Pg 24] time this yoke of steers were three years old, and when I was about twelve years of age.

One of my school mates and I had played truant one afternoon, and concluded to have a little fun with the steers, as my parents were away from home that day. We yoked them together, and I thought it a clever idea to hitch them to a large gate post which divided the lane and barn-yard, and see them pull. From this post Mr. Keefer had just completed the building of a fence, running to the barn, and had nailed the rails at one end, to this large post and had likewise fastened the ends of all the rails together, by standing small posts up where the ends met, and nailing them together, which made a straight fence of about four or five rods, all quite securely fastened together.

I hitched the steers to it, stepped back, swung my whip, and yelled, "Gee there," and they did "gee." Away they went, gate post and fence following after. I ran after them, yelling "whoa," at the top of my voice, but they didn't "whoa," and seemed bent on scattering fence-rails over the whole farm. One after another dropped off as they ran several rods down the lane, before I was able to overtake and stop them. Realizing that[Pg 27] we were liable to be caught in the act, we unhitched them on the spot, and after carrying the yoke back to the barn, went immediately to school so as to be able to divert suspicion from ourselves.

On the arrival home of my folks, which occurred just as school was out, Mr. Keefer drove to the barn, and at once discovered that his new fence had been moved and scattered down the lane—which was the most mysterious of anything that had ever occurred in our family. He looked the ground all over, but as we had left no clue he failed to suspect me.

The case was argued by all members of the family and many theories advanced, and even some of the neighbors showed their usual interest in trying to solve the mystery.

Of course it was the generally accepted belief that it was the spite-work of some one, but who could it be, and how on earth could anyone have done such a dare-devil thing in broad day light, when from every appearance it was no small task to perform, was the wonder of all. The more curious they became the more fear I had of exposure.

A few days later while Mr. Keefer and I were[Pg 28] in the barn, he remarked, that he would like to know who tore that fence down.

I then acknowledged to him that I knew who did it, and if he would agree to buy me a "fiddle," I would tell him all about it. He had for years refused to allow the "noisy thing in the house," as he expressed it, but thinking to clear up the mystery, he agreed, and I made a frank confession.

After this, he said he would buy me the fiddle when I became of age, and as I had failed to make any specifications in my compromise with him, he of course had the best of me.

I was not long, however, in getting even with him. I had a well-to-do uncle (my own father's brother) J. H. Johnston, in the retail jewelry business, at 150 Bowery, N. Y., (at which place he is still located). I wrote him a letter explaining my great ambition to become a fiddler, and how my folks wouldn't be bothered with the noise. I very shortly received an answer saying, "Come to New York at once at my expense; have bought you a violin, and want you to live with me until you are of age. You can attend school, and fiddle to your heart's content."

He also said, that after I had attended school eight years there, he would give me my choice of three things; to graduate at West Point, learn the jewelry business, or be a preacher.

When this letter was read aloud by my mother, in the presence of the family and a couple of neighbor boys, who had called that evening, it created a great deal of laughter.

One of the boys asked if my uncle was much acquainted with me, and when informed he had not seen me since I was two years old, he said that was what he thought.

My mother fixed me up in the finest array possible, and with a large carpet bag full of clothes, boots, shoes, hats, caps and every thing suitable, as she supposed, for almost every occasion imaginable. After bidding adieu forever to every one for miles around, I started for my new home.

On arriving at my uncle's store, he greeted me kindly, and immediately hustled me off to a clothing establishment, where a grand lightning change and transformation scene took place. I was then run into a barber shop for the first time in my life, and there relieved of a major portion of my crop of hair.

When we reached his residence I was presented to the family, and then with the fiddle, a box of shoe blacking and brush, a tooth brush, clothes brush, hair brush and comb, the New Testament and a book of etiquette.

I was homesick in less than twenty-four hours.

I would have given ten years of my life, could I have taken just one look at my yoke of steers, or visited my old quail trap, down in the woods, which I had not failed to keep baited for several winters in succession and had never yet caught a quail.

Whenever I stood before the looking glass, the very sight of myself, with the wonderful change in appearance, made me feel that I was in a far-off land among a strange class of people.

Then I would think of how I must blacken my shoes, brush my clothes, comb my hair, live up to the rules of etiquette and possibly turn out to be a preacher.

I kept my trouble to myself as much as possible, but life was a great burden to me.

My uncle was as kind to me as an own father, and gave me to understand, that whenever I needed money I had only to ask for it. This was a new phase of life, and it was hard for me[Pg 33] to understand how he could afford to allow me to spend money so freely. But when he actually reprimanded me one day for being stingy, and said I ought to be ashamed to stand around on the outside of a circus tent and stare at the advertising bills when I had plenty of money in my pocket, I thought then he must be "a little off in his upper story." Of course I didn't tell him so, but I really think for the time being he lowered himself considerably in my estimation, by trying to make a spendthrift of me. I had been taught that economy was wealth, and the only road to success. I thought how easily I could have filled my iron bank at home, in which I had for years been saving my pennies, had my folks been like my uncle.

Altogether it was a question hard to solve, whether I should remain there and take my chances of being a preacher and possibly die of home-sickness, with plenty of money in my pockets, or return to Ohio, where I had but a few days before bidden farewell forever to the whole country, and where I knew hard work on the farm awaited me, and economy stared me in the face, without a dollar in my pocket.

Of the two I chose the latter and returned home in less than three weeks a full fledged New Yorker. I brought my fiddle along and succeeded in making life a burden to Mr. Keefer, who "never was fond of music, anyhow," and who never failed to show a look of disgust whenever I struck up my tune.

Before I left New York, my uncle very kindly told me that if I would attend school regularly after getting home, he would assist me financially.

He kept his promise, and for that I now hold him in grateful remembrance.

I made rather an uneventful trip homeward, beguiling the time by playing my only tune which I had learned while in New York—"The girl I left behind me." It proved to be a very appropriate piece, especially after I explained what tune it was, as there were some soldiers on board the cars who were returning home from the war. They were profuse in their compliments, and said I was a devilish good fiddler, and would probably some day make my mark at it.

I felt that I had been away from home for ages, and wondered if my folks looked natural, if they would know me at first sight, and if the town had changed much during my absence.

When I alighted from the train at Clyde, I met several acquaintances who simply said, "How are you Perry? How are the folks?"

Finally I met one man who said, "How did it happen you didn't go to New York?"

Another one said:

"When you going to start on your trip, Perry? Where'd you get your fiddle?"

I then started for the farm, and on my arrival found no change in the appearance of any of the family.

My mother said I looked like a corpse.

Mr. Keefer said he was glad to see me, but sorry about that cussed old fiddle.

MY MOTHER WISHES ME TO LEARN A TRADE—MY BURNING DESIRE TO BE A LIVE-STOCK DEALER—EMPLOYED BY A DEAF DROVER TO DO HIS HEARING—HOW I AMUSED MYSELF AT HIS EXPENSE AND MISFORTUNE.

I then began attending school at Clyde, Ohio, boarding at home and walking the distance—three miles—during the early fall and late spring, and boarding in town at my uncle's expense during the cold weather.

At the age of sixteen I felt that my school education was sufficient to carry me through life and my thoughts were at once turned to business.

My mother frequently counseled with me and suggested the learning of a trade, or book-keeping, or that I take a position as clerk in some mercantile establishment, all of which I stubbornly rebelled against.

She then insisted that I should settle my mind on some one thing, which I was unable to do.

My greatest desire was to become a dealer in[Pg 39] live stock, which necessitated large capital and years of practical experience for assured success.

This desire no doubt had grown upon me through having been frequently employed by an old friend of the family, Lucius Smith, who was in that business.

He was one of the most profane men in the country, as well as one of the most honorable, and so very deaf as to be obliged to have some one constantly with him to do the hearing for him.

He became so accustomed to conversing with me as to enable him to understand almost every thing I said by the motion of my lips. For these services he paid me one dollar per day and expenses. I used to amuse myself a great deal at his expense and misfortune. He owned and drove an old black mare with the "string-halt" and so high-spirited that the least urging would set her going like a whirlwind.

Whenever we came to a rough piece of road I would sit back in my seat and cluck and urge her on in an undertone, when she would lay her ears back and dash ahead at lightning speed.

Mr. Smith unable to hear me or to understand the reason for this, would hang on to the reins[Pg 40] as she dashed ahead, and say: "See 'er go! See 'er go! The —— old fool, see 'er go! Did you ever see such a crazy —— old fool as she is? See 'er go! See 'er go! Every time she comes to a rough piece of road she lights out as if the d——l was after her. See 'er go! The crazy old fool. See 'er go!"

It was alone laughable to see the old mare travel at a high rate of speed on account of lifting her hind feet so very high in consequence of her "string-halt" affliction.

As soon as the rough road was passed over I would quit urging her, and she would quiet down to her usual gait.

Then Lute, with a look of disgust, would declare that he would trade the —— crazy old fool off the very first chance he had "if he had to take a goat even up for her."

One day we drove up to a farmer who was working in the garden, and Lute inquired at the top of his voice if he had any sheep to sell.

The man said he did not, and never had owned a sheep in his life. I waited until Mr. Smith looked at me for the man's answer when I said:

"Yes, he has some for sale."

Then a conversation about as follows ensued:

Smith—"Are they wethers or ewes?"

Farmer—"I told you I had none for sale."

Interpreter—In undertone, "Wethers."

Smith—"Are they fat?"

Farmer—"Fat nothing. I tell you I have no sheep."

Interpreter—"Very fleshy."

Smith—"About how much will they weigh?"

Farmer—"Oh, go on about your business."

Interpreter—"Six hundred pounds each."

Smith—"Great Heavens! Do you claim to own a flock of sheep that average that weight?"

Interpreter—"He says that's what he claims."

Smith—"Where are they? I would like to see just one sheep of that weight."

Farmer—Disgusted and fighting mad—"O, you are too gosh darn smart for this country."

Interpreter—"He says you had better not call him a liar."

Smith—"Who in thunder called you a liar?"

Farmer—"Well, you had better not call me a liar, either."

Interpreter—"He says you can't beat him out of any sheep."

Smith—"Who wants to beat you out of your sheep, you chump? I can pay for all I buy."

Farmer—looking silly—"Well that's all right. When did you get out of the asylum?"

Interpreter—"He says he wouldn't think so judging from your horse and buggy."

Smith—"Well, I'll bet five hundred dollars you haven't a horse on your cussed old farm that can trot with her."

Farmer—"Who said anything about a horse, you lunatic?"

Interpreter—"He says if you have so much money you'd better pay your debts."

Smith—"You uncultivated denizen of this God-forsaken country, I want you to distinctly understand I do pay my debts and I dare say that is more than you do."

Farmer—"Well, you are absolutely the crankiest old fool I ever saw."

Interpreter—"He says you don't bear that reputation."

Smith—"The dickens I don't. I don't owe you nor any other man a cent that I can't pay in five seconds."

Farmer—to his wife—"Great Heavens! What do you suppose ails that 'ere man?"

Interpreter—"He says he knows you, and you can't swindle him."

Smith (driving off)—"I think you are a crazy old liar anyhow, and I'll bet you never owned a sheep in your life."

The reader will be able to form a better idea of the ridiculousness of this controversy as it sounded to me, by simply reading the conversation between Smith and the farmer, omitting what I had to say.

The need of capital would of course have prevented me from going into the live stock business, and the very thought of my being compelled to work for and under some one else in learning a trade or business, was enough to destroy all pleasure or satisfaction in doing business. This caused my mother much anxiety, as it was a question what course I would pursue.

SELLING AND TRADING OFF MY FLOCK OF SHEEP—CO-PARTNERSHIP FORMED WITH A NEIGHBOR BOY—OUR DISSOLUTION—MY CONTINUANCE IN BUSINESS—COLLAPSE OF A CHICKEN DEAL—DESTRUCTION OF A WAGON LOAD OF EGGS—ARRESTED AND FINED MY LAST DOLLAR—ARRIVED HOME "BROKE."

I became very anxious to sell my sheep in order to invest the money in business of some kind, but could not find a buyer for more than twenty-five head. This sale brought me seventy-five dollars in cash, and I traded thirty-five head for a horse and wagon.

Thus equipped, I concluded to engage in buying and selling butter, eggs, chickens and sheep pelts. Not quite satisfied that I would succeed alone, I decided to take in one of our neighbor boys as a partner.

He furnished a horse to drive with mine, and we started out, each having the utmost confidence in the other's ability, but very little confidence in himself.

We made a two weeks' trip, and after selling out entirely and counting our cash, found we had eighteen cents more than when we started. We had each succeeded in ruining our only respectable suit of clothes, and our team looked as if it had been through a six months' war campaign.

My partner said he didn't think there was any money in the business, so we dissolved partnership.

I then decided to make the chicken business a specialty, believing that the profits were large enough to pay well. Mr. Keefer loaned me a horse, and after building a chicken-rack on my wagon, I started out on my new mission.

There was no trouble in buying what I considered a sufficient number to give it a fair trial, which netted me a total cost of thirty-five dollars.

Sandusky City, twenty miles from home, was the point designed for marketing them.

I made calculations on leaving home at one o'clock on the coming Wednesday morning, in order to arrive there early on regular market day.

The night before I was to start, a young acquaintance and distant relative came to visit me. He was delighted with the idea of accompanying me to the city when I invited him to do so.

During the fore part of the night a very severe rain storm visited us. I had left the loaded wagon standing in the yard.

Little suspecting the damage the storm had done me, we drove off in high spirits, entering the suburbs of the city at day-break.

Then Rollin happened to raise the lid on top of the rack, and discovered very little signs of life.

We made an immediate investigation and found we were hauling dead chickens to market, there being but ten live ones among the lot, and they were in a frightful condition. Their feathers were turned in all directions, and their eyes rolling backwards as if in the agonies of death. This trouble had been caused by the deluge of water from the rain of the night before, as I had neglected to provide a way for the water to pass through the box. The chickens that escaped drowning had been suffocated. We threw the dead ones into a side ditch, and hastened to the city. No time was lost in disposing of the ten dying fowls at about half their original cost.

We held a consultation and agreed that the chicken business was disagreeable and unpleasant anyhow. Then and there we decided to [Pg 49]withdraw from it in favor of almost any other scheme either might suggest. While speculating on what to try next, the grocer to whom we had sold the chickens remarked that he would give eighteen cents per dozen for eggs delivered in quantities of not less than one hundred dozen. I felt certain I could buy them in the country so as to realize a fair profit. After demolishing the chicken rack and loading our wagon with a lot of boxes and barrels, we started on our hunt for eggs. We soon learned that by driving several miles away to small villages, we could buy them from country merchants for twelve cents per dozen.

We bought over three hundred dozen and started back with only one dollar in cash left to defray expenses.

On the way our team became frightened at a steam engine and ran fully two miles at the top of their speed over a stone pike road. We were unable to manage them, but at last succeeded in reining them into a fence corner, where we landed with a crash, knocking down about three rods of fence, and coming to a sudden halt with one horse and half of the wagon on the opposite side, and the eggs flying about, scattered in all directions.

I landed on my head in a ditch, while the wagon-seat landed "right side up with care" on the road side, with Rollin sitting squarely in it as if unmolested. The mishap caused no more damage to horses and wagon than a slight break of the wagon pole and a bad scare for the horses.

But it was a sight to behold! The yelks streaming down through the cracks of the wagon box.

I felt that my last and only hopes were blasted as I gazed on that mixture of bran and eggs.

We were but a short distance from the city, whither we hastened and drove immediately to the bay shore.

There we unloaded the boxes and barrels and began sorting out the whole eggs and cracked ones. After washing them we invoiced about twenty-six dozen whole, and four dozen cracked. The latter we sold to a boarding house near by, and the former we peddled out from house to house. We counted our money, which amounted to five dollars and seventy-two cents. We then held another consultation, and decided that "luck had been against us." We also decided that we had better start at once for home, if we expected to reach there before our last dollar was lost. In [Pg 53]our confusion and excitement we prepared to do so, but happened to think we ought to feed our team before making so long a journey.

We returned to a grocery store, and after buying fifteen cents' worth of oats, drove to a side street, unhitched our horses, and turned their heads to the wagon to feed, after which we went to a bakery and ate bologna sausage and crackers for dinner.

On returning to the wagon we found a large fleshy gentleman awaiting us. He wore a long ulster coat and a broad-brimmed hat, and carried a large cane. After making several inquiries as to the ownership of the team, where we hailed from, and what our business was, he politely informed us that he was an officer of the law, and would be obliged to take us before the Mayor of the city. We asked what we had done that we should be arrested.

He simply informed us that we would find out when we got there.

We protested against any such proceedings, when he threw back his coat-collar, exposing his "star" to full view, and sternly commanded us to follow him. On our way to the Mayor's office I urged him to tell us the trouble, but in vain. I thought of every thing I had ever done, and [Pg 54]wondered if there were any law against accidentally breaking eggs or having chickens die on our hands. We arrived there only to find that the Mayor was at dinner.

The suspense was terrible!

The more I thought about it, the more guilty I thought I was.

In a few moments he returned, and I am certain I looked and acted as though I had been carrying off a bank.

When his Majesty took his seat, the officer informed him that we had been violating the city ordinance by feeding our horses on the streets. The Executive asked what we had to say for ourselves.

We acknowledged the truth of the statement, but undertook to explain our ignorance of the law.

He reminded us that ignorance of law excused no one, and our fine would be five dollars and costs, the whole amount of which would be seven dollars and fifty cents.

At this juncture we saw the necessity for immediate action towards our defense, as the jail was staring us in the face.

Rollin, who was older and more experienced[Pg 55] than myself, and withal a brilliant sort of lad, took our case in hand and made a plea that would have done credit to a country lawyer.

It resulted in a partial verdict in our favor, for after explaining our misfortunes and that all the money we had left was five dollars and thirty-seven cents, and as proof of our statement counted it out on his desk, he remitted what we lacked, but said as he raked in the pile, "Well, boys, I am very sorry for your misfortunes and will let you down easy this time, but you must be more careful hereafter."

I replied that he needn't have any fears of our ever violating their city ordinance again, as it was my impression that would be our last visit there.

We left for home without any further ceremony, neither seeming to have anything particular to say. I don't believe half a dozen words passed between us during the whole twenty miles ride.

On arriving home my mother anxiously inquired how I came out with my chicken deal.

"Well, I came out alive," I replied.

"How much money did you make?" she asked.

"How much money did I make? Well, when I got to Sandusky I discovered all my chickens were dead but ten," and explained the cause.

"Where have you been that you did not return home sooner?" she asked next.

I explained my egg contract and my trip in the country to procure them.

"Well, how was that speculation?" she asked.

"About the same as with the chickens," was my answer. When I entered into particulars concerning the wreck she became greatly disgusted, and sarcastically remarked:

"I am really surprised that you had sense enough to come home before losing your last dollar."

"Well," I replied, "I am gratified to know that such a condition of affairs would be no surprise to you, as it is an absolute fact that I have been cleaned out of not only my last dollar but my last penny."

I then rehearsed the visit to the Mayor and its results.

She gave me an informal notice that my services were required in the potato patch, and to fill the position creditably I should rise at five o'clock on the following morning.

BORROWING MONEY FROM MR. KEEFER—BUYING AND SELLING SHEEP PELTS—HOW I SUCCEEDED—A CO-PARTNERSHIP IN THE RESTAURANT BUSINESS—BUYING OUT MY PARTNER—COLLAPSED—MORE HELP FROM MR. KEEFER—HORSES AND PATENT RIGHTS.

I hardly complied with my mother's five o'clock order. When I did arise I sought Mr. Keefer, to whom I told the story of my misfortunes. He listened attentively and said he could easily see that it was bad luck, and he believed I would yet be successful. I explained to him that if he would lend me fifteen dollars, I could engage in buying sheep pelts, which could neither drown, suffocate nor break.

He complied with my request, and I started out that morning with only my own horse hitched to a light wagon.

Rollin, having finished his visit, left for home the same day.

I bought several pelts during the day, and sold[Pg 58] them to a dealer before returning home, making a profit of three dollars.

This was the first success I had met with during my three weeks' experience, and was certainly very encouraging. I continued in the business until cold weather, when I had cleared one hundred dollars.

I then began looking about for a chance to invest what I had made, as the weather was too cold to continue traveling in the country.

I was not long in finding an opportunity to invest with an old school mate in a restaurant.

It took about sixty days to learn that the business would not support two persons. As he was unable to buy me out, I made him an offer of my horse for his share, I to assume all liabilities of the firm, which amounted to about one hundred dollars.

He accepted my proposition. I sold the remainder of my flock of sheep, and paid the debts. I kept on with the business, meeting with splendid success in selling cigars and confectionery and feeding any number of my acquaintances, for which I received promises to pay, and which up to the present writing have never been collected.

When spring came, my liabilities were two hundred and fifty dollars, and no stock in trade. My available assets were a lot of marred and broken furniture which I peddled out in pieces, receiving in cash about one hundred dollars which I applied on my debts.

I called on Mr. Keefer with a full explanation of "just how it all happened," and he said he could see how it occurred, and without hesitation endorsed a note with me to raise the balance of my indebtedness.

Now I began looking for something else to engage in.

It was the wrong time of year for buying sheep pelts. My funds exhausted and in debt besides, I felt anxious to strike something very soon.

My mother still insisted that I should learn a trade or get steady employment somewhere. I told her there was nothing in it. She claimed there was a living in it, which I admitted, but declared if I kept "hustling" I would accomplish that much anyhow.

She gave me to distinctly understand that Mr. Keefer would sign no more notes nor loan me a dollar in money thereafter. Mr. Keefer held a note of fifty dollars against a man, not yet due,[Pg 60] which he handed to me that same morning, saying if I could use it I could have it.

A young in our village had just patented an invention for closing gates and doors. He offered me the right for the State of Illinois for this note, which I readily accepted.

In a few days I traded my right in this patent for six counties in Michigan and Indiana in a patent pruning shears, an old buck sheep, a knitting machine, an old dulcimer, a shot-gun and a watch.

I traded all of the truck except the watch, for an old gray mare. Then commenced a business of trading horses and watches.

In this I was quite successful during the summer and fall. I had paid my board and clothed myself comfortably, and was the owner of a horse which I had refused a large sum for, besides an elegant watch which I valued highly.

My mother said it was a regular starved-to-death business.

Mr. Keefer said he knew I would make it win.

SWINDLED OUT OF A HORSE AND WATCH—MORE HELP FROM MR. KEEFER—HOW I GOT EVEN IN THE WATCH TRADE—MY PATENT RIGHT TRIP TO MICHIGAN AND INDIANA—ITS RESULTS—HOW A WOULD-BE SHARPER GOT COME UP WITH.

One day as I was passing the house of a neighboring farmer he came out and hailed me.

"How's business?" he asked.

"O, first-class," I answered.

"Don't you want to trade your horse and watch for a very fine gold watch?" he asked, confidentially.

"Why, I don't know."

"Well," he remarked, "I have owned such a watch for three years, and have no use for one of so much value. A cheaper one will do me just as well, and I am ready to give you a good trade."

I entered the house with him, and he said: "Wife, bring me that gold watch from the other room."

"All right," she said, and brought the watch and handed it to me, saying as she did so, "I have been in constant fear for three years of having that watch stolen from us, and I hope my husband will trade it off, and relieve me of so much anxiety."

I took it, examined it and discovered a small rusty spot in the inside of one of the cases. I called their attention to it and said, "I don't really like the looks of that spot."

"Well, sir," said he, "if you don't like the looks of that rusty spot, just leave it right where it is. But if you like it well enough to give me your horse and watch and chain for it, all right. If not, there will be no harm done."

His independence caught me, I traded at once.

I walked back home with much pride, and showed my new watch to the folks.

My mother looked at it suspiciously and said, in rather a sneering tone, "Why, it looks like a cheap brass watch, and I believe it is."

"O, I think that watch is all right," said Mr. Keefer, in an assuring manner, "and I believe he has made a good trade. We'll hitch up the team and go down to Geo. Ramsey (the jeweler) and see what he has to say about it."

So we started off and handed the watch to Mr. Ramsey. He looked it over carefully and said:

"Well, Perry, it is so badly out of repair that it would not pay you to have it fixed."

"What would be the expense?"

"About five dollars."

"After being put in good order what would it be worth?" I confidently asked again.

"Well, Mr. Close, the auctioneer down street, has been selling them for three dollars and a half apiece."

I put the watch in my pocket, and thanking him, left the store, and explained to Mr. Keefer "just how it all happened."

He said he thought "it was enough to fool any one."

I then borrowed fifteen dollars of him, to "sort of bridge me over," until I could get on my feet again.

I kept quiet about my trade. In fact, I had nothing to say. I simply told two or three of my acquaintances who I thought might help me out.

A few days after this a gentleman from Kentucky made his appearance on the streets with a patent rat trap.

One of the men to whom I had shown the[Pg 64] watch, happened to be talking to him as I passed by, and remarked:

"That red-headed fellow owns a watch which he traded a horse and nice watch for a few days ago, and I believe you can trade him territory in your patent for it."

"I'll give you ten dollars if you will help me put it through," said the rat trap man.

"All right, I'll help you," said my friend.

It was not long before I was found and induced to look at the rat trap.

I was immensely pleased with it, and felt certain I could sell a rat trap to every farmer in the country, if I had the right to do so.

"What is the price of Sandusky County?"

"One hundred dollars."

"Well, I guess the price is reasonable enough," I said, "but I haven't got the money."

"What have you got to 'swap'?"

"I don't think I have anything," I answered.

"Haven't you got a horse, town lot or watch? I am in need of a good watch and I would give some one an extra good trade for one."

I replied: "I have a watch, but I don't care to trade it off."

"Let me see it," said he. After looking it over, he said:

"It suits me first-rate. How will you trade?"

"I'll trade for one hundred dollars and Sandusky County."

"No," he said, "I'll give you fifty dollars in cash, and the County."

"I won't take that," I said, "but I'll tell you what I will do. I'll take seventy-five dollars."

"I'll split the difference with you."

"All right, make out the papers."

He did so, and handed me over sixty-two dollars and fifty cents and the patent, (which I still own), for my watch.

An hour afterwards I met the Kentuckian who excitedly informed me that the watch was not gold. I frankly admitted that I knew it was not, and that I didn't remember of ever saying it was. He had paid my friend five dollars of the ten he had promised, and his reason for not paying the balance was because he had been obliged to pay cash difference to make the trade.

He looked crest-fallen and discouraged and took the first train out of town, "a sadder and a wiser man."

With my sixty odd dollars and a sample pair[Pg 66] of pruning shears, I left for Michigan, to take orders, and if possible, to sell some portion or all of my six counties. In that invention I owned Branch, Hillsdale and Leneway Counties in Michigan, and Steuben, La Grange and St. Joseph in Indiana.

I arrived at Bronson, Michigan, from which point I started out taking orders. My success was immense, but I was somewhat handicapped for the reason that none of the farmers wanted the shears delivered to them before the coming spring.

At last I found a customer for the Michigan counties, and traded them for a handsome bay horse which I bought a saddle for, and rode through to Ohio. On arriving home I explained my success in taking orders.

My mother said I was a goose for not staying there and working up a nice business, instead of fooling away the territory for a horse.

Mr. Keefer said he would rather have the horse than all the territory in the United States.

I traded the horse to one of our neighbors for a flock of sheep and sold them for one hundred and twenty-five dollars. I then started for La Grange, Indiana, to dispose of my other three[Pg 67] counties. I took several orders on the following Saturday, as many farmers were in town that day.

The next Monday I received word from one of the wealthiest men of the town that he would buy some territory in my patent if satisfactory terms could be made. I called upon him and we were not long in striking a bargain.

He agreed to give his note payable in one year for three hundred dollars, for my three counties.

We made out the papers, and as he was about to sign the note he demanded that I write on the face of it the following: "This note was given for a patent right." I refused at first, but when informed it was according to law I complied.

When I called upon a money loaner he laughed and said he wouldn't give me one dollar for such a note, as he wouldn't care to buy a lawsuit. He said when the note came due it would be easier for the maker of it to prove the worthlessness of the patent than it would for him to prove it was valuable.

I saw the point, and realized that I had been duped.

I made preparations to leave for home on the morning train. During the night I conceived an idea which I thought if properly manipulated would bring me out victorious.

The next morning I called on my customer at his office, and in the presence of his clerks said:

"Mr. ——, I have been thinking over my affairs, and find I will be very much in need of money six months from now, and if you will draw up a new note, making it come due at that time, I will throw off twenty-five dollars, and give you back this note."

He agreed, and after I drew up the note for two hundred and seventy-five dollars I handed it to him to sign, and then stepped back out of reasonable reach of him, when he looked up and said:

"Well, here, you want to add that clause."

"That's all right," said I, "go on and sign it. It can be added just as well afterwards."

He did so and I picked it up, folded it and put it into my pocket, as I passed the old note to him.

"But you must add that clause," he remarked.

"O, no," said I, "I guess I must not. This last note was not given for a patent right. It was given for the old note, the same as if you had discounted it."

Then he saw the point, and I had the pleasure of receiving two hundred and sixty-five dollars cash from him for his paper. With this I started for home, highly elated with my success.

MY NEW ACQUAINTANCE AND OUR CO-PARTNERSHIP—THREE WEEKS' EXPERIENCE MANUFACTURING SOAP—THE COLLAPSE—HOW IT HAPPENED—BROKE AGAIN—MORE HELP FROM MR. KEEFER—A TRIP TO INDIANA—SELLING PRIZE SOAP WITH A CIRCUS—ARRESTED AND FINED FOR CONDUCTING A GIFT ENTERPRISE—BROKE AGAIN.

On my way home, I formed the acquaintance of a young man, Fleming by name, who had been employed in a soap factory in Chicago, and was on his way to Toledo, where his parents resided. He said he had a new recipe for making a splendid toilet soap, which could be put on the market for less money and with a larger profit than any other ever manufactured.

With a little capital and an enterprising salesman on the road, a fortune could be made very soon.

I stated the amount of my cash capital, and assured him of my ability as a salesman, and my desire to engage in a good paying business.

When we arrived at Toledo, and before we separated, we had nearly completed arrangements for forming a co-partnership, I agreeing to return in a few days for that purpose. I hastened home and notified my folks of my success.

My mother said "it was merely a streak of good luck." Mr. Keefer said "he didn't know about that."

She said I had better leave enough with them to pay that note of one hundred and fifty dollars, which would soon come due, but Mr. Keefer said it wasn't due yet and there was no hurry about it anyhow, and that I had better invest it in that soap business.

I returned to Toledo, where I met Mr. Fleming, who had rented a building and contracted for materials and utensils. We started our business under the firm name of "Johnston & Fleming, Manufacturers of Fine Toilet Soap."

I advanced the necessary money to meet our obligations, after which we made up a sample lot, and I started on the road.

My orders were taken on condition that the goods were to be paid for promptly in ten days.

I sold to druggists and grocers, and made enough sales in one week to keep our factory[Pg 73] running to its "fullest capacity" for at least four weeks. I then returned to Toledo and began filling orders.

As soon as ten days had expired, after having sent out our first orders, we began sending out statements, asking for remittances.

We received but two small payments, when letters began pouring in from our customers condemning us and our soap.

The general complaint was that it had all dried or shriveled up, and as some claimed, evaporated.

One druggist wrote in, saying the soap was there, or what there was left of it, subject to our orders. He was thankful he had not sold any of it, and was glad he had discovered the fraud before it had entirely disappeared and before he had paid his bill!

Another druggist stated that he had analyzed it and would swear that it was made of "wind and water;" while still another declared that his wife had attempted to wash with a cake of it, and was obliged to send down town for some "soap" to remove the grease from her hands.

After reading a few of these letters, I opened my traveling case, took out my original sample box, and discovered at once that in shaking it, it[Pg 74] rattled like a rattle-box. I raised the cover and found my twelve sweet-scented, pretty cakes of soap had almost entirely withered away, and the odor was more like a glue factory than a crack toilet soap. We made strenuous efforts to satisfy them, by making all manner of excuses and apologies but to no purpose. In every instance "the soap was there subject to our orders."

My partner was much chagrined at the outcome and sudden collapse of our firm, and no doubt felt the situation more deeply than myself, although I was the loser financially.

After borrowing money enough from an old school-mate, I paid my board bill and bought a ticket for home. I had been away less than four weeks.

I first met Mr. Keefer at the barn and explained to him "just how it all happened," and how the soap dried up, and how I had become stranded at Toledo and borrowed money to get home with.

He said he guessed he would have to let me have the money to pay the fellow back, as I had promised, which he did, and a few dollars besides.

I then went to the house and explained matters to my mother.

She said I might have known just how that[Pg 75] soap business would end, and reminded me of the request she made about leaving money enough to pay the note and informed me that I needn't expect any help from Mr. Keefer, for he should not give me a penny.

The next day while in town, I met and got into conversation with a friend who was on his way to Huntington, Ind., to take a position as an agent for selling fruit trees. He showed me a letter from the General agent of an Eastern nursery, who stated that there were vacancies at Huntington for half a dozen live, enterprising young men. I had just about cash enough to pay my fare there, and decided to go.

We arrived there the next day, only to find that the fruit tree men had gone to the southern part of the State.

I explained to Charlie that I was rather low financially, when he informed me that he was a little short himself, but that I could rest assured that so long as he had any money he would divide.

Forepaugh's Menagerie was advertised to be at Huntington two days later, and we decided to await its arrival and see what might turn up in our favor.

The menagerie arrived and drew an immense crowd of people.

I had frequently seen men sell prize packages at fairs, and conducting almost all kinds of schemes to make money, and it occurred to me that with such a large crowd, and so few street salesmen, there was a good opportunity for making money, if one could strike the right thing.

I consulted with Charlie, who said he would be able to raise about two dollars after paying our board.

I suggested my plan, which he considered favorably.

We purchased a tin box and three large cakes of James S. Kirk's laundry soap, and some tinfoil.

We cut the soap into small, equal sized cakes about three inches long, and a half inch square at the ends. We then cut small strips of writing paper, and after marking 25c on some of them and 50c, 75c, and $1.00 and $2.00 on an occasional one, we pasted a strip of this paper on each cake of soap, some prizes and many blanks. We then cut the tinfoil and wrapped it nicely around the soap and put it into the tin box. Then after borrowing a couple of boxes and a[Pg 79] barrel from a merchant, put them out on the street and turned the barrel bottom side up on top of one of the boxes.

I then mounted the other box, and soon gathered an immense crowd by crying out, at the top of my voice:

"Oh yes! oh yes! oh yes! Gentlemen, every one of you come right this way; come a running; come a running, everybody come right this way!

"I have here, gentlemen, the erasive soap for removing tar, pitch, paint, oil or varnish from your clothing. Every other cake contains a prize from twenty-five cents to a two-dollar note."

We found no trouble in making sales and but little trouble in paying off those who were lucky. Our profits were sixteen dollars that day.

The next day we opened at Fort Wayne, Ind., where the show attracted a large crowd, and our profits were thirty-six dollars.

From there we went to Columbia City, where our profits were twenty-two dollars. Our fourth and last sale was made at Warsaw, where we were having excellent success, when a large, portly gentleman (whom I afterwards learned was Mr. Wood, the prosecuting attorney), came up to our stand, and after listening awhile and watching[Pg 80] the results, went away, and in a few moments returned with the city marshal, who placed me under arrest for violating a new law just passed, to prohibit the running of gift enterprises. They took me before the Mayor, who read the charges against me, and asked what I had to say.

I informed him I had taken out city license, which I supposed entitled me to the privilege of selling.

He then read the new law to me, I plead ignorance, and asked the Mayor to be lenient. He imposed a fine of twenty-five dollars and costs, which altogether amounted to thirty-two dollars and fifty cents, which we paid.

The prosecuting attorney then explained to me, that such a law had recently been passed in almost every State.

This satisfied me that there was absolutely no money in the soap business. My partner and I divided up what little money we had left and there separated. He returned to Ohio and I visited a daughter of Mr. Keefer's, who had married a wealthy farmer, Smith by name, and was residing in Branch County, Michigan.

ELEVEN DAYS ON A FARM—HOW I FOOLED THE FARMER—ARRIVED AT CHICAGO—RUNNING A FRUIT STAND—COLLAPSED—MY RETURN HOME—BROKE AGAIN—A LUCKY TRADE.

I was anxious to go to Chicago, but was a "little short" financially, and asked Mr. Smith to give me a job on the farm. He asked if I could plow. I assured him that I was a practical farmer, and he then hired me at one dollar per day.

He had a sixty acre field, in which his men had been plowing, and after hitching up a pair of mules instructed me to go over in the field and go to "back furrowing."

I wondered what the difference could be between back furrowing or any other furrowing, but rather than expose my ignorance, said nothing, preferring to trust to luck and the "mules." As there was no fault found, I must have struck it right.

Mr. Smith made a practice of visiting his men[Pg 82] and inspecting their work, always once and often twice a day.

He gave me orders to go to breaking up a new piece of ground, which he had recently finished clearing, and which of course was a hard task.

One day he came to the field at noon, and after looking the work over, instructed me to take the "coulter" off before I commenced work again in the afternoon, adding that it would be easier for the mules as well as myself.

I looked the plow over carefully and wondered what the "coulter" was. After dinner I began work, hoping that some one might come along who could post me. In this I was disappointed. Realizing that there must be something done before Smith visited me in the evening, I decided he must have meant the wheel at the end of the beam, and consequently took it off and waited his coming.

When he arrived he looked at the plow a moment and said, in an impetuous manner:

"Where is that wheel? I thought I told you to take the coulter off."

"Well, I did," I quickly replied. "I did take the coulter off, and as it didn't work well I put it back on, and thought I would take the wheel off."

"Where is the wheel?" he asked. I pointed to a stump some distance away, and said:

"It's over there."

He said: "You take that coulter off and I'll get the wheel."

"No," I said, "you take the coulter off; I am younger than you and will go after the wheel." And before getting the words out of my mouth was half way there. When I returned he was taking the coulter off.

I worked eleven days, and after receiving that many dollars left for Chicago, where I had an uncle residing.

He gave me a cordial welcome and said I was just the lad he wanted to see, as he had traded for a fruit stand the day before, and wanted me to take charge of it.

The next morning he took me to the stand, which was a small frame building—size, about eight by ten—which stood on the northwest corner of Halsted and Harrison Streets.

This was a very slow business, and too slow to suit me, yet I continued to run it about three months, when by repeated losses on decayed fruit, and the too frequent visits of relatives and friends, we found the business in an unhealthy[Pg 86] condition and lost no time in looking up a buyer, which we were fortunate in finding and successful in getting a good price from.

After receiving my share of the profits, which was about enough to pay my expenses back to Ohio, I decided to go there.

On arriving home, my mother said she hoped I was satisfied now that I couldn't make money, and that I was only fooling my time away. She said she had told Mr. Keefer just how that fruit business would end.

I took Mr. Keefer to one side and explained just "how it all happened" and how the fruit all rotted, and how my relatives and friends helped themselves. He said they ought to be ashamed and it was too bad.

I borrowed a few dollars from him for incidental expenses, until I could "strike something."

My mother wanted to know what I expected to do, and said I needn't ask Mr. Keefer for money, because he shouldn't give me a penny.

Of course I could give her no satisfaction. She finally said was going to take me to a jeweler, with whom she had talked, and have me learn the jeweler's trade. I disliked the idea and rebelled against it. She was determined, however, and compelled me to accompany her.

The jeweler had a talk with me and told my mother he thought he could make quite a mechanic out of me.

I thought I was destined to stay with him, until my mother happened to leave the store for a few minutes, when he asked me if I thought I would like the business. I told him no, I knew I would dislike it. He said he wouldn't fool his time away with a boy who had no taste for the business, and so informed my mother.

I returned home with her, and that evening she and Mr. Keefer and myself had a long conference.

We talked about the past, and my mother suggested all kinds of trades, professions and clerkships, all of which I objected to, because I would not work for some one else.

Mr. Keefer said he believed I would strike something "yet" that I would make money out of.

My mother said she couldn't understand why he should think so; everything had been a failure thus far.

He explained his reasons by reminding her that with all my misfortunes, not one dollar had been spent in dissipation or gambling, but[Pg 88] invariably in trying to make money, and with no lack of energy.

I remained idle a few days until the few dollars Mr. Keefer had loaned me were spent, when one day I called upon a friend in town. Kintz by name, who was engaged in the bakery business.

In conversation with him I learned that he owned two watches and wanted to exchange one of them (a small lady's gold watch) for something else. I asked him to let me carry it and try and find a customer for it.

I called that evening on the night telegraph operator, Andy Clock, and bantered him to trade watches. He owned a large silver watch and gold chain.

"How will you trade?" I asked, showing him the lady's gold watch.

"Oh, I'll leave it with you."

"You ought to give your watch and chain and ten dollars," I said.

"I'll make it five."

"Let me take your watch and chain a few minutes."

"All right," he answered.

I immediately called on Mr. Kintz and said: "John, are you willing to give your gold watch[Pg 89] and five dollars for Mr. Clock's silver watch and gold chain?"

He replied by simply handing me five dollars. I then returned to Mr. Clock, made the trade and also received from him five dollars.

Although the amount I made was small, it came in a very opportune time, and afforded me much satisfaction, as I argued in my own mind, that if I was able to drive those kind of trades in a small way, while young, I might be able some day to make similar deals on a larger scale.

The next day, when I met Mr. Keefer, I explained how I had made ten dollars. He laughed and said: "Well, if they are both satisfied I suppose you ought to be."

The next Sunday after I had made the trade, several of the boys, including Mr. Kintz, Clock and myself, were sitting in the hotel. I was reading a paper when Mr. Kintz and Clock began a conversation about the watch trade, when Kintz remarked:

"If that gold watch had not been a lady's size I never would have paid any difference on the trade."

"Did you give any boot?" quickly asked Clock.

"Why, I gave five dollars," answered Kintz.

"The d——l you did; so did I," replied Clock.

They immediately demanded an explanation, which I gave, by declaring as the "middleman" I was entitled to all I could make; and this was the universal opinion of every one there, including the landlord, who insisted that it was a good joke and well played.

THREE DOLLARS WELL INVESTED—LEARNING TELEGRAPHY—GETTING IN DEBT—A FULL-FLEDGED OPERATOR—MY FIRST TELEGRAPH OFFICE—BUYING AND SELLING DUCKS AND FROGS WHILE EMPLOYED AS OPERATOR—MY RESIGNATION—CO-PARTNERSHIP IN THE JEWELRY AND SPECTACLE BUSINESS—HOW WE SUCCEEDED—OUR DISSOLUTION.

The next day after making this trade and procuring the ten dollars, I bought an old silver watch from a stranger who had become stranded, paying him three dollars for it. This I traded for another watch and received five dollars as a difference. From this I continued to make trades until I was the owner of ten head of fine sheep, three pigs, a shot-gun, violin, watch, and a few dollars in money, besides having paid my board at the hotel and bought necessary clothing.

When I found a buyer for my sheep and pigs, my mother said of course I couldn't be contented until I sold them and lost the money. I [Pg 92]explained to her that, in order to speculate, it was necessary to keep re-investing and turning my money often.

Mr. Keefer said I was right, but advised me to be very careful, now that I had quite a nice start from simply nothing.

After selling out, I one day called on the day telegraph operator, Will Witmer, and while sitting in his office, asked him to explain the mysteries of telegraphy. He did so, and I then asked him to furnish me with the telegraph alphabet, which he did. I studied it that night, and the next day called at his office again, and began practicing making the letters on the instrument.

He paid me a very high compliment for my aptness, and said I was foolish for not learning the business.

I asked what the expense would be.

He said his charges would be fifteen dollars, and it would take four months anyhow, and possibly six, before I would be able to take an office.

Two days later, after giving special attention to the business, I had become quite infatuated with it, and paid over the fifteen dollars to him and two weeks' board at the hotel.

My intentions were to try and sustain myself[Pg 93] by speculating and trafficking, but I very soon became so absorbed in my new undertaking as to be unfit for that business.

My mother was immensely pleased at the turn affairs had taken. Mr. Keefer was both surprised and pleased, and said he would help me pay my board, although he couldn't see how I ever happened to take a liking to that business.

During this winter, my associates and habits of life differing wholly from those of former years, I became what would now be considered "quite a dude." And having no income from business, and a limited one from Mr. Keefer, with a fair future prospect, I took advantage of my good credit in town, and bought clothes, boots, shoes and furnishing goods, and borrowed money occasionally from my friends, who never refused me.

Three months from the very day I began learning the alphabet, through the advice and recommendation of Mr. Witmer, I called on Wm. Kline, Jr., General Superintendent of Telegraph, and made application for an office. He sent me to Whiting, Indiana, sixteen miles from Chicago, with instructions to take charge of the night office, at a salary of forty dollars per month.