Title: Marguerite

Author: Anatole France

Translator: J. Lewis May

Release date: May 9, 2008 [eBook #25406]

Most recently updated: February 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

Publish Marguerite, dear Monsieur André Coq, if you so desire, but pray relieve me from all responsibility in the matter.

It would argue too much literary conceit on my part were I anxious to restore it to the light of day. It would argue, perhaps, still more did I endeavour to keep it in obscurity. You will not succeed in wresting it for long from the eternal oblivion where-unto it is destined. Ay me, how old it is! I had lost all recollection of it. I have just read it over, without fear or favour, as I should a work unknown to me, and it does not seem to me that I have lighted upon a masterpiece. It would ill beseem me to say more about it than that. My only pleasure as I read it was derived from the proof it afforded that, even in those far-off days, when I was writing this little trifle, I was no great lover of the Third Republic with its pinchbeck virtues, its militarist imperialism, its ideas of conquest, its love of money, its contempt for the handicrafts, its unswerving predilection for the unlovely. Its leaders caused me terrible misgivings. And the event has surpassed my apprehensions.

But it was not in my calculations to make myself a laughing-stock, by taking Marguerite as a text for generalizations on French politics of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The specimens of type and the woodcuts you have shown me promise a very comely little book.

Believe me, dear Monsieur Coq,

Yours sincerely,

Anatole France.

La Béchellerie, 16th April, 1920.

As I left the Palais-Bourbon at five o’clock that afternoon, it rejoiced my heart to breathe in the sunny air. The sky was bland, the river gleamed, the foliage was fresh and green. Everything seemed to whisper an invitation to idleness. Along the Pont de la Concorde, in the direction of the Champs-Elysées, victorias and landaus kept rolling by. In the shadow of the lowered carriage-hoods, women’s faces gleamed clear and radiant and I felt a thrill of pleasure as I watched them flash by like hopes vanishing and reappearing in endless succession. Every woman as she passed by left me with an impression of light and perfume. I think a man, if he is wise, will not ask much more than that of a beautiful woman. A gleam and a perfume! Many a love-affair leaves even less behind it. Moreover, that day, if Fortune herself had run with her wheel a-spinning before my very nose along the pavement of the Pont de la Concorde, I should not have so much as stretched forth an arm to pluck her by her golden hair. I lacked nothing that day; all was mine. It was five o’clock and I was free till dinner-time. Yes, free! Free to saunter at will, to breathe at my ease for two hours, to look on at things and not have to talk, to let my thoughts wander as I listed. All was mine, I say again. My happiness was making me a selfish man. I gazed at everything about me as though it were all a picture, a splendid moving pageant, arranged for my own particular delectation. It seemed to me as though the sun were shining for me alone, as though it were pouring down its torrents of flame upon the river for my special gratification. I somehow thought that all this motley throng was swarming gaily around me for the sole purpose of animating, without destroying, my solitude. And so I almost got the notion that the people about me were quite small, that their apparent size was only an illusion, that they were but puppets; the sort of thoughts a man has when he has nothing to think about. But you must not be angry on that score with a poor man who has had his head crammed chock-full for ten years on end with politics and law making and is wearing away his life with those trivial preoccupations men call affairs of state.

In the popular imagination, a law is something abstract, without form or colour. For me a law is a green baize table, sealing-wax, paper, pens, ink-stains, green-shaded candles, books bound in calf, papers yet damp from the printer’s and all smelling of printer’s ink, conversations in green papered offices, files, bundles of documents, a stuffy smell, speeches, newspapers; a law, in short, is all the hundred and one things, the hundred and one tasks you have to fulfil at all hours, the grey and gentle hours of the morning, the white hours of middle day, the purple hours of evening, the silent, meditative hours of night; tasks which leave you no soul to call your own and rob you of the consciousness of your own identity.

Yes, it is so. I have left my own ego behind me there. It is scattered up and down among all sorts of memoranda and reports. Industrious junior clerks have put away a parcel of it in each one of their beautiful green filing cases. And so I have had to go on living without my ego, which, moreover, is how all politicians have to live. But an ego is a strangely subtle thing. And wonder of wonders! mine came back to me just now on the Pont de la Concorde. ‘Twas he without a doubt and, would you believe it, he had not suffered so very much from his sojourn among those musty papers. The very moment he arrived I found myself again, I recognized my own existence, whereof I had not been conscious these ten years. “Ha ha!” said I to myself, “since I exist, I am just as well pleased to know it. Behold I will set forth here and now to improve this new acquaintance by strolling, with a lover’s thoughts in my heart, down the Champs-Elysées.”

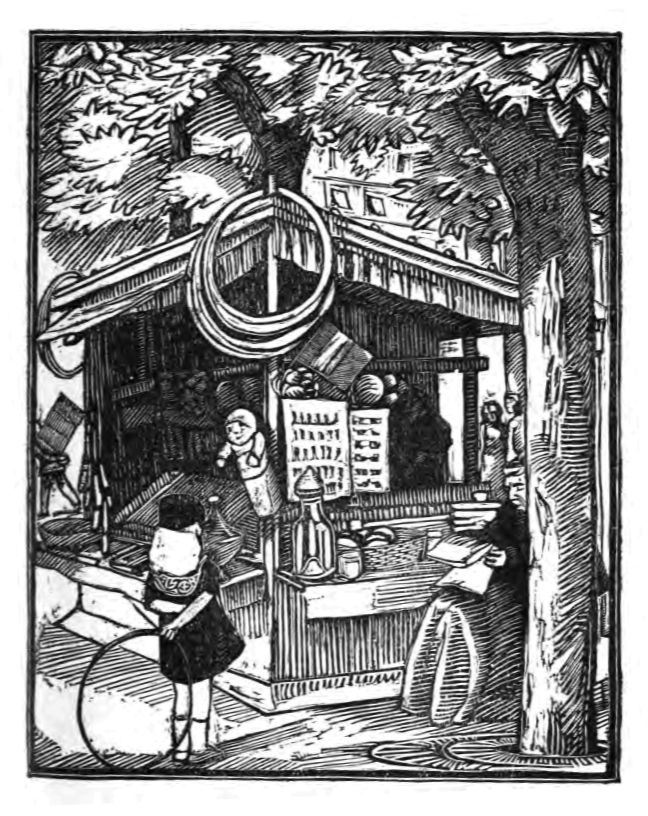

And this is why I am here, at this hour, beneath the sculptured steeds of Marly, more high-spirited than those aristocratic quadrupeds themselves; this is why I am setting foot in the avenue whose entrance is marked by their hoofs of stone perpetually poised in air. The carriages flow past endlessly, like a sombre scintillating stream of lava or molten asphalt, whereon the hats of the women seem borne along like so many flowers, and like everything else one sees in Paris, at once extravagant and pretty. I light up a cigar and looking at nothing, behold everything. So intense is my joy that it scares me. It is the first cigar I have smoked for ten years. Oh yes, I grant I have begun as many as ten a day in my room; but those I scorched, bit, chewed and threw away; I never smoked them. This one I am really and truly smoking and the smoke it exhales is a cloud of poesy spreading grace and charm about it. What an interest I take in all I see. These little shops, which display at regular intervals their motley assortment of wares, fill me with delight. Here especially is one which I cannot forbear stopping to look at. What I chiefly delight to contemplate there is a decanter with lemonade in it. The decanter reflects in miniature on its polished sides the trees around it and the women that pass by and the skies. It has a lemon on the top of it which gives it a sort of oriental air. However, it is not its shape nor its colour that is the attraction in my eyes; I cannot keep my gaze from it because it reminds me of my childhood. At the sight of it, innumerable delightful scenes come thronging into my memory. Once again do I behold those shining hours, those hours divine of early childhood. Ah, what would I not give to be again the little boy of those days and to drink once more a glass of that precious liquid!

In that little shop, I find once more, besides the lemonade and the gooseberry syrup, all those divers things wherein my childhood took delight. Here be whips, trumpets, swords, guns, cartridge-pouches, belts, scabbards, sabretaches, all those magic toys which, from five to nine years old, made me feel that I was fulfilling the destiny of a Napoleon. I played that mighty rôle, in my tenpenny soldier’s kit, I played it from start to finish, bating only Waterloo and the years of exile. For, mark you, I was always the victor. Here, too, are coloured prints from Épinal. It was on them that I began to spell out those signs which to the learned reveal a few faint traces of the Mighty Riddle. Yes, the sorriest little coloured daub that ever came out of a village in the Vosges consists of print and pictures, and what is the sum and substance of Science after all but just pictures and print?

From those Épinal prints I learned things far finer and more useful than anything I ever got from the little grammar and history books my schoolmasters gave me to pore over. Épinal prints, you see, are stories, and stories are mirrors of destiny. Blessed is the child that is brought up on fairy-tales. His riper years should prove rich in wisdom and imagination. And see! here is my own favourite story The Blue Bird. I know him by his outspread tail. ‘Tis he right enough. It is as much as I can do to prevent myself flinging my arms round the old shop-woman’s neck and kissing her flabby cheeks. The Blue Bird, ah me, what a debt I owe him! If I have ever wrought any good in my life, it is all due to him. Whenever we were drafting a Bill with our Chief, the memory of the Blue Bird would steal into my mind amid the heaps of legal and parliamentary documents by which I was hemmed in. I used to reflect then that the human soul contained infinite desires, unimaginable metamorphoses and hallowed sorrows, and if, under the spell of such thoughts, I gave to the clause I chanced to be engaged upon an ampler, a humaner sense, an added respect for the soul and its rights, and for the universal order of things, that clause would never fail to encounter vigorous opposition in the Chamber. The counsels of the Blue Bird seldom prevailed in the committee stage. Howbeit some did manage to get through Parliament.

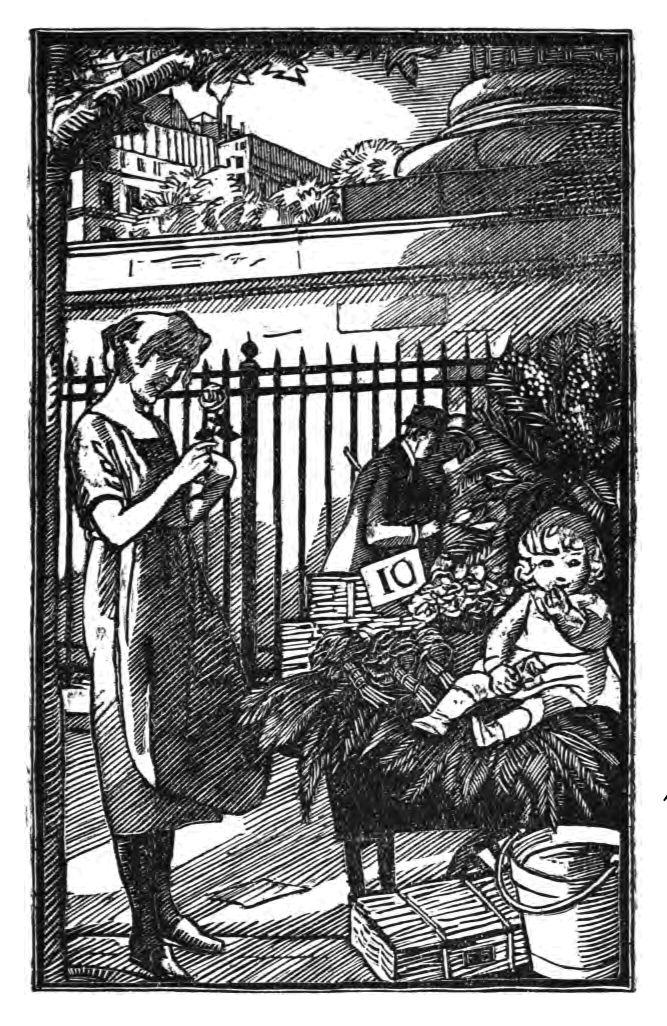

I now perceive that I am not the only one inspecting the little stall: a little girl has come to a halt in front of the brilliant display. I am looking at her from behind. Her long, bright hair comes tumbling in cascades from under her red velvet hood and spreads out on her broad lace collar and on her dress, which is the same colour as her hood. Impossible to say what is the colour of her hair (there is no colour so beautiful) but one can describe the lights in it; they are bright and pure and changing, fair as the sun’s rays, pale as a beam of starlight. Nay, more than that, they shine, yes; but they flow also. They possess the splendour of light, and the charm of pleasant waters. Methinks that, were I a poet, I should write as many sonnets on those tresses as M. José Maria de Heredia composed concerning the Conquerors of Castille d’Or. They would not be so fine, but they would be sweeter. The child, so far as I can judge, is between four and five years old. All I can see of her face is the tip of her ear, daintier than the daintiest jewel, and the innocent curve of her cheek. She does not stir; she is holding her hoop in her left hand; her right is at her lips as though she were biting her nails in her eager contemplation. What is it she is gazing at so longingly? The shop contains other things besides the arms and the gear of fighting men. Balls and skipping ropes are suspended from the awning. On the stall are baby dolls with bodies made of grey cardboard, smiling after the manner of idols, monstrous and serene as they. Little six-penny dolls, dressed like servant girls, stretch out their arms, little stumpy arms so flimsy that the least breath of air sets them a-tremble. But the little maid whose hair is made of liquid light, has no eyes for these dolls and puppets. Her whole soul hangs upon the lips of a beautiful baby doll that seems to be calling her his mummy. He is hitched on to one of the poles of the booth all by himself. He dominates, he effaces everything else. Once you have beheld him, you see naught else save him.

Bolt upright in his warm wraps, a little swansdown tucker under his chin, he is stretching out his little chubby arms for some one to take him. He speaks straight to the little maid’s heart. He appeals to her by every maternal instinct she possesses. He is enchanting. His face has three little dots, two black ones for the eyes, and one red one for the mouth. But his eyes speak, his mouth invites you. He is alive.

Philosophers are a heedless race. They pass by dolls with never a thought. Nevertheless the doll is more than the statue, more than the idol. It finds its way to the heart of woman, long ere she be a woman. It gives her the first thrill of maternity. The doll is a thing august. Wherefore cannot one of our great sculptors be so very kind as to take the trouble to model dolls whose lineaments, coming to life beneath his fingers, would tell of wisdom and of beauty?

At last the little girl awakens from her silent day-dream. She turns round and shows her violet eyes made bigger still with wonder, her nose which makes you smile to look at it, her tiny nose, quite white, that reminds you of a little pug dog’s black one, her solemn mouth, her shapely but too delicate chin, her cheeks a shade too pale. I recognize her. Oh yes! I recognize her with that instinctive certainty that is stronger than all convictions supported by all the proofs imaginable. Oh yes, ‘tis she, ‘tis indeed she and all that remains of the most charming of women. I try to hasten away but I cannot leave her. That hair of living gold, it is her mother’s hair; those violet eyes, they are her mother’s own; Oh, child of my dreams, child of my despair! I long to gather you to my arms, to steal you, to bear you away.

But a governess draws near, calls the child and leads her away: “Come, Marguerite, come along, it’s time to go home.”

And Marguerite, casting a look of sad farewell at the baby with its outstretched arms, reluctantly follows in the footsteps of a tall woman clad in black with ostrich feathers in her hat.

“Jean, bring me file 117.... Now then, M. Boscheron, let’s get this circular done. Take this down: I draw your special attention, M. le Préfet, to the following point. An end must be put at the earliest possible moment to an abuse which, if suffered to continue, would tend to—tend to—I draw your special attention to the following point, M. le Préfet. An end must be put as soon as possible to an abuse. Take that down, M. Boscheron.”

But M. Boscheron, my secretary, respectfully remarks that I keep on dictating the same sentence. Jean deferentially places a file on my table.

“What’s that, Jean?”

“File number 117. You asked me to fetch it, sir.”

“I asked you for file number 117?”

“Yes, sir.”

Jean gives me an anxious glance and retires.

“Where were we, M. Boscheron?”

“An end must be put as soon as possible to an abuse . . . .”

“That’s right... an abuse which would tend to diminish popular respect for government servants and to transform... transform, what a wealth of hidden things that word conceals. I cannot so much as pronounce it but a world of ideas and sentiments come thronging pell-mell to invade the secret recesses of my being.” “I beg pardon, monsieur?” “What did you say, M. Boscheron?” “Please repeat, monsieur; I didn’t quite follow you.”

“Really, Monsieur Boscheron? Possibly I was not very clear. Well, well! we will stop there if you like. Give me what I have dictated, I will finish it myself.”

M. Boscheron gives me his notes, gathers up his papers, bows and retires. Left alone in my office, I fall to examining the wallpaper with a sort of idiotic minuteness. It has the appearance of green felt with here and there a yellow stain; I begin to draw little men on my paper; I make an effort to write; for the fact is my Chief has asked for the circular three times and has promised the government deputies that it shall go to the prefects forthwith. I am bound to let him have it. I begin reading it through: to diminish popular respect for government servants and to transform them. I make a blot; then with my pen I adorn it with hair. I transform it into a comet. I dream of Marguerite’s tresses. The other day, in the Champs-Elysées, little filaments of gold, little delicate spirals stood out from the rest of her graceful tresses, with a singular brightness. You can see their like in fifteenth century miniatures, also in some of an earlier date. Dante says in his Vita Nuova: “One day when I was busy drawing angel’s heads . . .” And now here am I trying to draw angels’ heads on a government circular. Come now, we must get on with it: government servants and to transform them—transform them . . . How is it I simply cannot write a single word after that? How is it I am here dreaming still, as I have been ever since I rediscovered my ego on the Pont de la Concorde that evening of the lovely sunset? Transform, did I say? O God of mystery, nature, truth, if she whose name even now after four years I dare not utter, if she died in giving life to Marguerite, I should believe, I should know with the certainty of instinct, that the soul of the mother had passed into the daughter and that they are one and the same being.

All’s well. I have lost my ego again. It has gone back into the green filing cases. Number 117 contains a good part of it. I have finished my circular. It is drawn up in good official style. We have a fine piece of legislation to get off before the holidays. My Chief speaks every day in the House. Every night I correct the proofs of his speeches. If the Blue Bird comes to see me now and again in the small hall of the Palais Bourbon, it is merely to advise me to tone down some rather too forcible expression and he never addresses himself to my imagination. I don’t know whether I am living happily or unhappily since I don’t know that I am living at all. I do not even recognize my own clothes. I picked up the hat of the Comte de Mérodac a little while ago and wore it for three days without knowing it, yet it is a romantic sombrero-like sort of thing worn nowadays by no one save this elderly nobleman. I cut an astounding figure they told me, but I never noticed myself, and, if by chance I had, I should not have heeded what I saw since it had nothing to do with politics. I am no longer a person; I am a piece of the official machine. To-night I have neither proofs to correct nor official reception to attend. I have put on my slippers. There is always a tiny bit of my ego hidden away in these slippers. I am in my room seated by the fire and I am conscious of being there. By heaven I wonder whether I should know myself in the glass. Let’s have a look. Hum! not so very ... I didn’t think I was so grave and respectable looking. I quite see that I shall have to take myself seriously. I have been a long time about it, but then it wasn’t for me to begin.

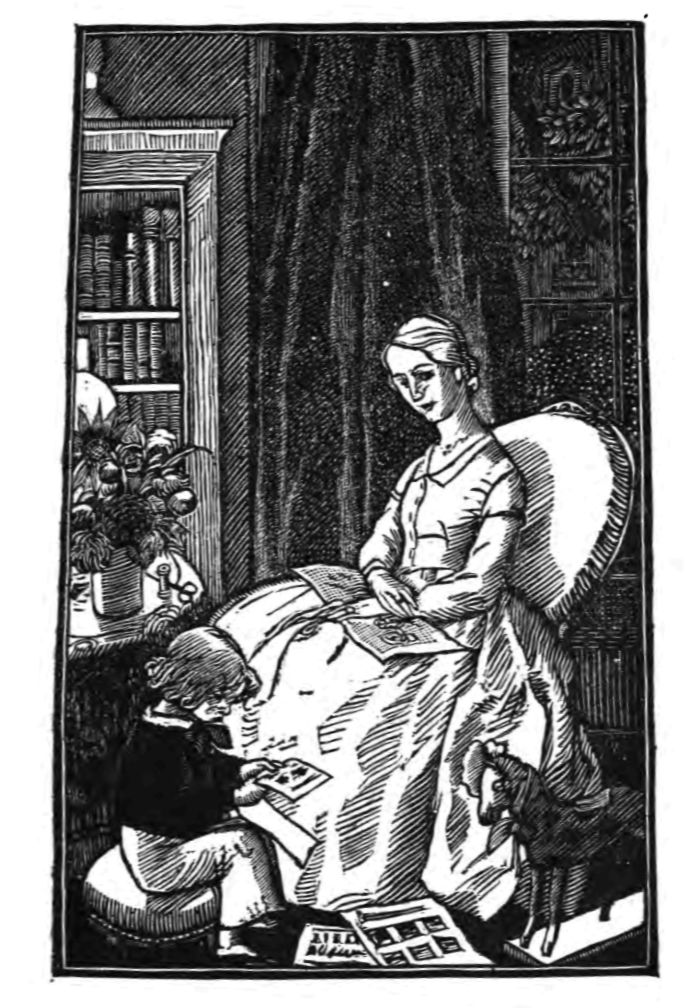

I am a man of weight and I account myself such. But, alas, I do not know myself. And I am not anxious to acquire the knowledge; it would be a tedious business. No, I haven’t the smallest desire to hold converse with the grave and frigid gentleman who mimics all my movements. On the other hand, did I but dare, what a happy time I should have with that little fellow whose miniature I see there in that locket hanging against the frame of the mirror. He is building a house with dominoes. What a nice little chap. I feel like calling him and saying “Let’s go and have a game together shall we?” But, alas, he is far away, very far away. That little boy is myself as I was forty years ago. He is dead, just as dead as if I were lying beneath the sod, sealed up in a leaden coffin. For what have we in common, he and I? In what respect does he survive in me to-day? In what do my castles of cards resemble his tower of dominoes?

We say that we live, we miserable beings, because we keep dying over and over again.

I remember, it is true, how I used to play my games of an evening what time my mother sat sewing at the table and gazed at me, now and again, with a look full of that beautiful and simple tenderness that makes one adore life, bless God and gives one courage enough to fight a score of battles. Ah yes, hallowed memories, I shall treasure you in my heart like a precious balm which, till my days are done, will have power to soothe all bitterness and soften the very agony of death. But does the child that I then was survive in me today? No. He is a stranger to me; I feel that I can love him without selfishness and weep for him without unmanliness. He is dead and gone, and has taken away with him my innocent simplicities and my boundless hopes. We all of us die in swaddling clothes. Little Marguerite, that delightful image of unfolding life, how many times has she not died and what profound depths of irrevocable memories, what a grave of dead thoughts and emotions has not already been delved within her, though she is but five years old. I, a stranger, a passer-by, know more of her life than she does and, in consequence, I am more truly she than she herself. After that let him who will prate of the feeling of identity and the consciousness of self.

Oh, gracious Heaven, what things we mortals be and into what an abyss of terrors we should be for ever plunging if we had but time to think, instead of making laws or planting cabbages. I feel like pulling my slippers off my feet and pitching them out of the window, since they have called me back to the consciousness of my existence. Our lives are only bearable provided we do not think about them.

It is a year ago to-day since I fell in with that little girl in front of a toyshop in the Champs-Elysées, the child of her who first awakened in me the sense of beauty.

I was happy before I saw her; but the poetry of the wide world was unknown to me, nor had I had experience of the dolorous joys of love. The first time I saw Marie was one Good Friday at a classical concert to which her father, an old diplomat with a passion for music, who had heard the finest orchestras of every Court in Europe, had conducted her attired in stately weeds of solemn black. Her mourning garb only served to accentuate her radiant beauty. The sight of her aroused in me feelings which bore, I think, a close resemblance to religious exaltation. I was no longer very young. The uncertainty of my worldly position, dependent as it then was upon the vicissitudes of a political party, combined with my natural timidity to deprive me of all hope of figuring as a successful suitor. I often saw her at her father’s and she treated me with an air of open friendliness that did not encourage me to foster higher ambitions. It was clear I did not impress her as the sort of man with whom she could fall in love. As for me, the sight of her and the sound of her voice produced in me such a state of delicious agitation that the mere memory of it, mingled though it be with grief, still avails to make me in love with life.

Nevertheless, shall I avow it? I longed to hear her and to see her always; I would have died in rapture at her side, but I was never fain to wed her. No, some instinct of harmony held desire remote from my heart. “It was not love then,” some one will say. I know not what it was, but I know that it filled my soul.

Clearly, however, the feelings I experienced cannot have been strange to the heart of man, since I have found them expressed with power and sweetness in the works of the poets, in Virgil, in Racine and Lamartine. They have given utterance to the emotions which I but felt. I could not break silence. The miracles wrought in my soul by this young girl will remain for ever unrevealed. For two years I lived an enchanted life; then, one day, she told me she was going to be married. My feelings, as I have said, bear a strong resemblance to religious emotion. They are sad, but in their sadness they still preserve their charm. Grief corrupts them not. From suffering they derive a wholesome bitterness that lends them strength. I listened to her with that gentle courage which comes with renunciation. She was marrying a man senior to myself, a widower, almost an old man, whose birth and fortune had marked him out for the public career in which he had displayed a haughtiness of disposition and much misplaced courage. Although I moved in a lower sphere, I came in contact with him on several important occasions. I belonged to a political group with views very similar to his own, but we had never been able to meet without considerable friction and, although the newspapers treated us with the same approval or, as was more often the case, with the same hostility, we were not friends, far from it, and we avoided each other with sedulous care.

I was present at the wedding. I saw, and I shall ever see Marie, wearing her white dress and lace veil. She was a little pale and very lovely. I was struck, without apparent reason, by the impression of fragility with which this girl who was animated by so poetic a soul seemed to give one. This impression, which I think occurred to no one but myself, was only too well founded. I never saw Marie again.

She died after three years of married life, leaving a little girl ten months old. An indescribable feeling of tender affection has always drawn me to this child, to Marie’s Marguerite. An unconquerable desire to see her took possession of me.

She was being brought up at ——— near Melun, where her father had a château standing in the midst of a magnificent park. One day I went to ——— and wandered for hours, like a thief, about the park bound-aries. At last, through a gap in the trees, I caught sight of Marguerite in the arms of her nurse, who was dressed in black. She was wearing a hat with white plumes and an embroidered pelisse. I cannot say in what respect she differed from any other child, but I thought she was the fairest in the world. It was autumn. The wind that was sighing in the trees was whirling the dead leaves about in little eddies as they floated to earth. Dead leaves covered all the long avenue in which the little white-robed child was being carried up and down. An immense sadness took possession of me. At the edge of a bed of flowers as white as the raiment of Marguerite, an old gardener who was gathering up the fallen leaves saluted his little mistress with a smile and, with his hand on his rake and hat in hand, spoke to her with the gentle gaiety of old men who are not overburdened with their thoughts. But she paid no heed to him. With her little hand like to a star she sought her nurse’s breast. As I hurried away with grief in my heart, the nurse resumed her walk and I heard the sound of the dead leaves sighing sorrowfully beneath her steps.

The President of the Chamber rises and says: “The motion proposed by Messrs. ——— and ——— is now put.”

The Prime Minister, without quitting his seat says: “The Government does not assent to the motion.”

The President rings his bell and says: “A ballot has been demanded. A ballot will therefore be taken. Those in favour of Messrs. ——— and ———‘s motion must place a white paper in the urn; those who are against it, a blue paper.”

There was a great movement in the hall. The deputies poured out in a disorderly mob into the corridors, while the ushers passed the white metal urn along the tiers of seats. The corridors were full of the sound of shuffling feet, and of shouting and gesticulating people. Grave looking young men and excited old ones went passing by. The air was pierced with the sound of voices calling out figures:

“Eleven votes.”

“No, nine.”

“They are being checked.”

“Eight against.”

“No, not at all; eight for.”

“What, the amendment is carried?”

“Yes.”

“The Government is beaten?”

“Yes.”

“Ah!”

The President’s bell is heard in the corridors.

Slowly the hall fills again.

The President standing up with a paper in his hand rings his bell for the last time and says:

“The following is the result of the ballot on the motion proposed by Messrs. ——— and ———. Number of votes 470; for the motion 239 ; against 231. The motion is carried.”

There is an immense sensation. The Ministers get up and leave their seats. Two or three friends shake them timidly by the hand. It’s all over, they are beaten. They go under and I with them. I no longer count. I make up my mind to it. To say that I am happy would be to go too far. But it spells the end of my worries and bothers and toils. I have regained my freedom, but not voluntarily. Repose and liberty, I’ve got them back again, but it is to my defeat that I owe them. An honourable defeat it is true, but painful all the same because our ideas suffer with ourselves. How many things are involved in our fall, alas. Economy, public security, tranquillity of conscience and that spirit of prudence, that continuity of policy, which gives a nation its strength. I hurried away to shake hands with the Chief of my department, proud of having rendered faithful service to so upright a leader. Then, pushing my way through the crowd that had gathered about the precincts of the Palais Bourbon, I crossed the Seine and made my way slowly towards the Madeleine. At the top of the boulevard there was a barrow of flowers drawn up alongside the kerb. Between the two shafts was a young girl making up bunches of violets. I went up to her and asked her for a bunch. I then saw a little girl of four sitting on the barrow amid the flowers. With her baby fingers she was trying to make bunches like her mother. She raised her head at my approach and, with a smile, held out all the flowers she had in her hands. When she had given them all to me, she blew kisses.

I was extremely flattered. “I must have a kindly look about me,” I said to myself, “for a child to smile a welcome at me like that. What is your name?” I asked her.

“Marguerite,” replied her mother.

It was half-past six. There was a news-vendor’s hard by. I bought a paper. As soon as I glanced at it I saw that I was in for a wigging. The political editor, having referred to my Chief as an individual of ill omen, spoke of me too, on the first page, as a sinister creature. But, after Marguerite’s kisses, I could not believe it. I felt at once a lightness and a sort of emptiness at heart; both glad and sorrowful.

A week later found me on my way, to ——— near Melun, where I had taken a little house hard by the Château of Marguerite’s upbringing. In my eyes it was the fairest region in the world.

As we approached the station I looked out of the carriage window. The silver river flowed in graceful curves between willows, until it vanished from the sight. But long after it was lost to view one could divine its course by the rows of poplars which lined its banks. A weathercock and two towers visible amid the trees marked the site of the town. Then I exclaimed, “Here is the resting place for me, here will I lay my head.”

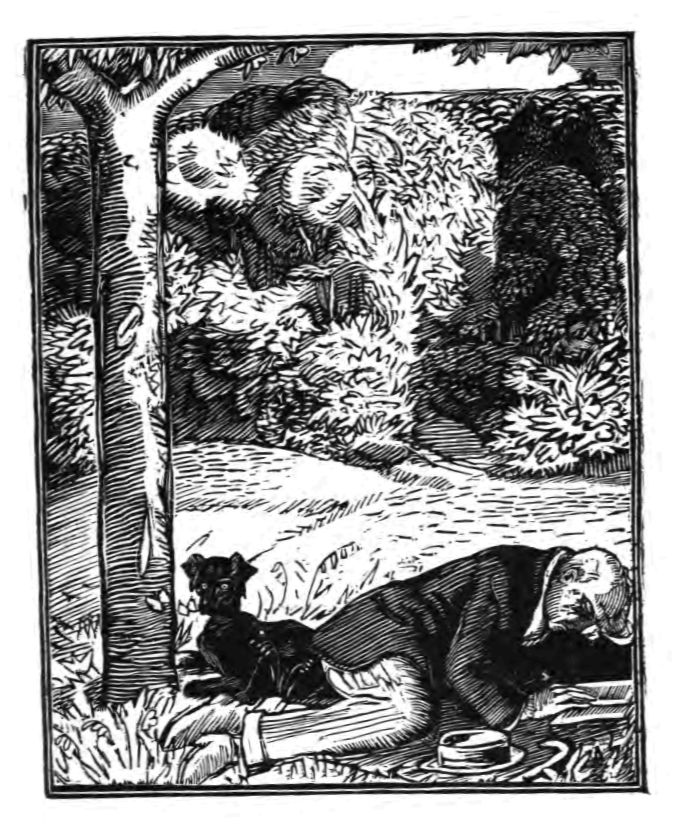

The walk I love best is the walk to Saint-Jean, for there, about a hundred yards from the town is a little wood, or rather a little half-wild cluster of hornbeams, maples, limes and lilac bushes, a bouquet that murmurs in the breeze. The very first day I discovered it, I felt its charm. I determined to make love to it; I made up my mind to know it tree by tree, to search out its humblest plants, its vetches, its saxifrages, and to see whether there was no Solomon’s seal to be found growing beneath the shade of the big trees. I kept my word and now I am beginning to make acquaintance with the flora and fauna of my little wood. I had been reclining on the grass to-day for the space of an hour, book in hand, when I heard some one crying in a faint voice. I looked up and beheld a little girl standing beside an elderly man and weeping. The man was undeniably old. His face was long and pallid. There was an expression of sadness in his eyes and his mouth drooped mournfully. He had a skipping-rope in his hand and was looking fixedly at the child. Then he turned aside to brush away a tear from his cheek. It was then that I beheld him full face and saw that he was Marguerite’s father. I was shocked at the great change that illness and sorrow had wrought in his haughty mien. Despair was graven on his countenance and he seemed to be calling for help.

I went up to him and, in response to my offer to assist him in any way possible, he explained with some embarrassment that a ball with which his little girl had been playing had got caught in a tree and that his stick, which he had thrown up in order to dislodge it, had become entangled in the branches. He was at his wit’s end.

Only a few years before, this same man had circumvented the policy of England and imparted a vigorous stimulus to French diplomacy in Europe. Then he fell with honour, and was followed in his retirement by a profound but honourable unpopularity. And now, behold his powers are unequal to the task of dislodging a ball from a tree. Such is the frailty of man. As for his daughter, Marie’s daughter, a sort of presentiment forbade me to look in her face. And then when at length I did look at her, I could not tear myself away from such a sorrowful object of contemplation. She was no longer the little pink and white child I had seen in the Champs-Elysées; she had grown taller and thinner, and her face was wan as a waxen taper. Her languid eyes were encircled with blue rings. And her temples . . . what invisible hand had laid those two sad violets upon her temples?

“There! there! there!” cried the old man as he stretched forth a trembling arm which pointed aimlessly in all directions.

The first thing to be done was to help him. By means of a stone which I threw up into the tree, I soon managed to bring the ball down. X . . . witnessed its fall with childish delight. He had not recognized me. I hurriedly escaped to spare him the trouble of thanking me and myself the agony of seeing the change that had taken place in Marie’s daughter.

I seldom go out. I am no longer moved by the beauty of things. Or to speak more truly, the more pleasurable and splendid aspects of nature give me pain. All day long I sully sheet after sheet of paper and beguile the tedious hours with the half-faded recollections of my childhood. What I am writing will be burned. I should be ashamed that pages, tear-stained and dream-haunted, should fall beneath the eyes of grave, sober-minded folk. What would they see in them? Naught but childish faces.

To-dau I went for a stroll by the river in whose blue waters are mirrored the willows and the houses that befringe its banks. There is a seductive charm about running waters. They bear along with them as they flow all those idlers who love to dream their time away.

The river lured me as far as the château de- ——— which had witnessed the betrothal and the death of Marie, and the birth of Marguerite. My heart tolled a knell within me when I saw once more that peaceful abode, which, despite the scenes of sorrow enacted within its walls, speaks, with its white pillared façade, of naught save elegant opulence and luxurious repose. I was so overcome that, to save myself from falling, I clung to the bars of the park gate and gazed at the wide lawns which stretched away as far as the flight of steps which the hem of Marie’s robe had kissed so often. I had been there some minutes when the gate was opened and X ... came out.

On this occasion, also, he was accompanied by his child: but this time she was not walking. She was lying in a perambulator which was being pushed by a governess. With her head resting on an embroidered pillow in the shadow of the lowered hood, she resembled one of those little waxen images of saint or martyr, embellished with silver filigree, on whose wounds and gems the nuns of Spain are wont to pore in the solitude of their cells.

Her father, elegantly dressed, presented a faded, tear-stained countenance. He advanced towards me with little faltering steps, took me by the hand and led me to his little girl.

“Tell me,” he said in the tone of a child asking a favour, “you don’t think she has changed since you last saw her, do you? It was the day she threw her ball up into the tree.”

The perambulator which we were following in silence came to a halt in the Bois Saint-Jean. The governess lowered the hood. Marguerite lay with her head thrown back, her eyes big with terror, and she was stretching out her arms to push aside something that we could not see. Oh, I guessed well enough what invisible hand it was. The same hand that had touched the mother was now laid upon the child. I fell on my knees. But the phantom departed and Marguerite, raising her head, lay resting peacefully. I gathered some flowers and laid them reverently beside her. She smiled. Seeing her come back to life I gave her more flowers and sang to her, endeavouring to beguile her. The air and the feeling of happiness she now experienced brought back to her that desire to live which had forsaken her. At the end of an hour her cheeks were almost rosy. When it grew cool and we had to take the little suffering child back to the château again, her father took my hand as we parted and, pressing it, said in suppliant tones:

“Come again to-morrow.”

I returned next day. On the steps of the Empire château I encountered the family doctor. He is a spare, elderly man whom you meet wherever there is good music to be heard. He seems like a man perpetually listening to the harmonies of some inward concert. He is for ever under the spell of sounds and lives by his ear alone. He is specially noted for his treatment of nervous complaints. Some say he is a genius; others that he is mad. Certainly there is something peculiar about him. When I saw him he was coming down the steps; his feet, his finger and his lips moving in time to some intricate measure.

“Well, doctor,” I said with an involuntary quaver in my voice, “and how is your little patient?”

“She means to live,” he answered.

“You will pull her through for us, won’t you?” I said eagerly.

“I tell you she means to live.”

“And you think, doctor, that people live just as long as they really want to and that we do not die save with our own consent?”

“Certainly.”

I walked with him along the gravel path. He stopped for a moment at the gate, his head bowed as if in thought.

“Certainly,” he said again, “but they must really want to and not merely think they want to. Conscious will is an illusion that can deceive none save the vulgar. People who believe they will a thing because they say they will it, are fools. The only genuine act of volition is that in which all the obscure forces of our nature take part. That will is unconscious, it is divine. It moulds the world. By it we exist, and when it fails we cease to be. The world wills, otherwise it would not exist.”

We walked on a few steps farther.

“Look here,” he exclaimed, tapping his stick against the bark of an oak tree that spread out its broad canopy of grey branches above our heads, “if that fellow there had not willed to grow, I should like to know what power could have made him do so.”

But I had ceased to listen.

“So you have hopes,” I said at length, “that Marguerite . . .”

But he was a stubborn little old fellow.

He murmured as he walked away: “The Will’s crowning Victory is Love.”

And I stood and watched him as he departed with little quick steps, beating time to a tune that was running in his head.

I went quickly back to the château and found little Marguerite. The moment I saw her, I realized that she had the will to live. She was still very pale and very thin, but her eyes had more colour in them and were not so big, and her lips, lately so dead-looking and so silent, were gay with prattling talk.

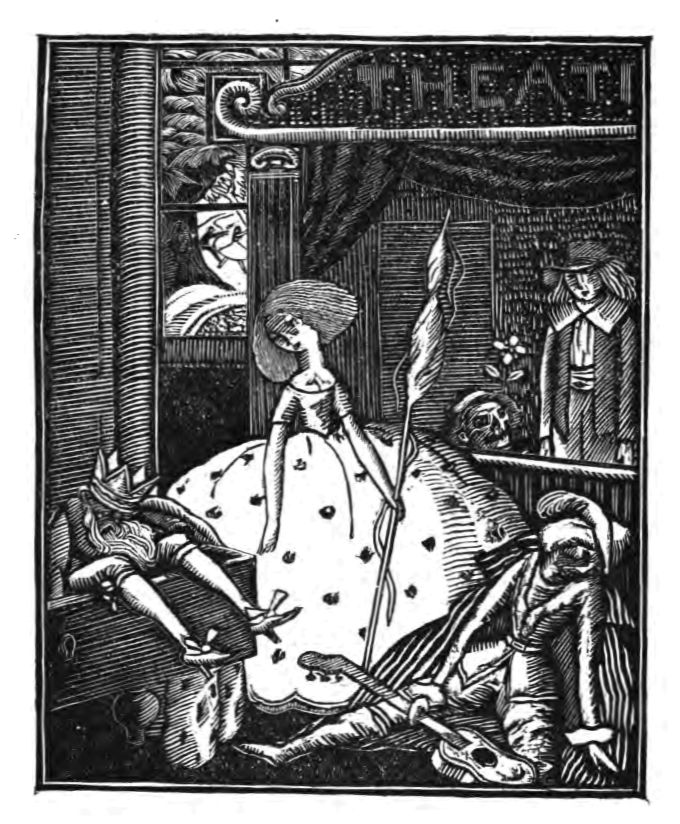

“You are late,” she said. “Come here, see! I have a theatre and actors. Play me a beautiful piece. They say that ‘Hop o’ my Thumb’ is nice. Play ‘Hop o’ my Thumb’ for me.”

You may be sure I did not refuse. However, I encountered great difficulties at the very outset of my undertaking. I pointed out to Marguerite that the only actors she had were princes and princesses, and that we wanted woodmen, cooks and a certain number of folks of all sorts.

She thought for a moment and then said:

“A prince dressed like a cook; that one there looks like a cook, don’t you think?”

“Yes, I think so too.”

“Well, then, we’ll make woodmen and cooks out of all the princes we have over.”

And that’s what we did. O Wisdom, what a day we spent together!

Many others like it followed in its train. I watched Marguerite taking an ever firmer hold on life. Now she is quite well again. I had a share in this miracle. I discovered a tiny portion of that gift wherein the apostles so richly abounded when they healed the sick by the laying on of hands.

Editor’s Note.—I found this manuscript in a train on the Northern Railway. I give it to the public without alteration of any sort, save that, as the names were those of well-known persons, I have thought it well to suppress them.

Anatole France.