A GREEK SHEPHERD, OLYMPIA.

A GREEK SHEPHERD, OLYMPIA.

Title: Historic Tales: The Romance of Reality. Vol. 10 (of 15), Greek

Author: Charles Morris

Release date: May 29, 2008 [eBook #25642]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/25642

Credits: Produced by David Kline, Greg Bergquist and The Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Édition d'Élite

The Romance of Reality

By

CHARLES MORRIS

Author of "Half-Hours with the Best American Authors," "Tales from the

Dramatists," etc.

IN FIFTEEN VOLUMES

Volume X

Greek

J.B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

PHILADELPHIA AND LONDON

Copyright, 1896, by J.B. Lippincott Company.

Copyright, 1904, by J.B. Lippincott Company.

Copyright, 1908, by J.B. Lippincott Company.

| PAGE | |

| How Troy Was Taken | 7 |

| The Voyage of the Argonauts | 28 |

| Theseus and Ariadne | 33 |

| The Seven Against Thebes | 41 |

| Lycurgus and the Spartan Laws | 50 |

| Aristomenes, the Hero of Messenia | 60 |

| Solon, the Law-Giver of Athens | 67 |

| The Fortune of Crœsus | 77 |

| The Suitors of Agaristé | 86 |

| The Tyrants of Corinth | 93 |

| The Ring of Polycrates | 100 |

| The Adventures of Democedes | 109 |

| Darius and the Scythians | 117 |

| The Athenians at Marathon | 126 |

| Xerxes and His Army | 135 |

| How the Spartans Died at Thermopylæ | 144 |

| The Wooden Walls of Athens | 154 |

| Platæa's Famous Day | 165 |

| Four Famous Men of Athens | 174 |

| How Athens Rose From its Ashes | 186 |

| The Plague at Athens | 194 |

| The Envoys of Life and Death | 200 |

| The Defence of Platæa | 205 |

| How the Long Walls Went Down | 213 |

| Socrates and Alcibiades | 221 |

| The Retreat of the Ten Thousand | 231 |

| The Rescue of Thebes | 245 |

| The Humiliation of Sparta | 259 |

| Timoleon, the Favorite of Fortune | 271 |

| The Sacred War | 288 |

| Alexander the Great and Darius | 296 |

| The World's Greatest Orator | 305 |

| The Olympic Games | 315 |

| Pyrrhus and the Romans | 324 |

| Philopœmen and the Fall of Sparta | 334 |

| The Death-Struggle of Greece | 345 |

| Zenobia and Longinus | 351 |

| The Literary Glory of Greece | 360 |

GREEK.

| PAGE | |

| A Greek Shepherd, Olympia | Frontispiece. |

| Parting of Hector and Andromache | 15 |

| Œdipus and Antigone | 42 |

| Grecian Ladies at Home | 87 |

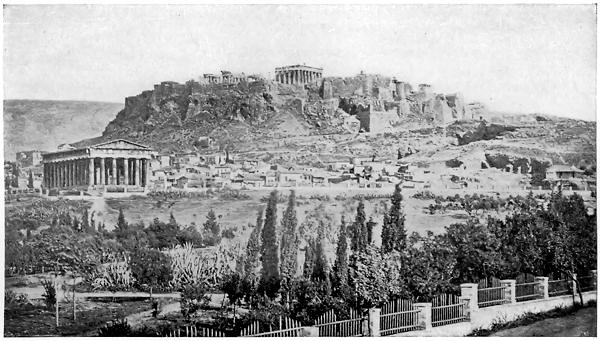

| The Acropolis of Athens | 98 |

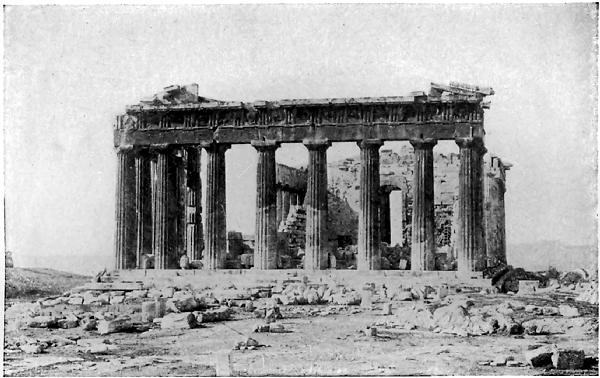

| Ruins of the Parthenon | 130 |

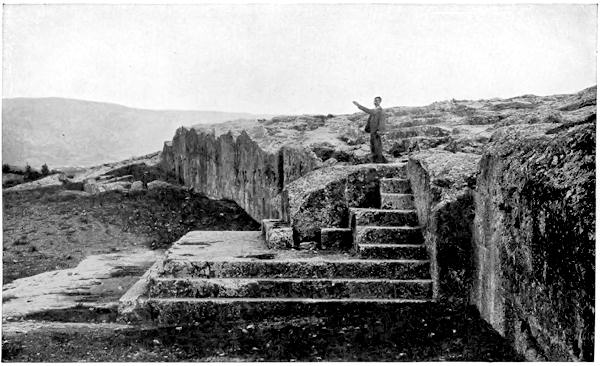

| The Place of Assembly of the Athenians | 145 |

| The Victors at Salamis | 160 |

| Ancient Entrance To the Stadium, Athens | 181 |

| A Reunion at the House of Aspasia | 190 |

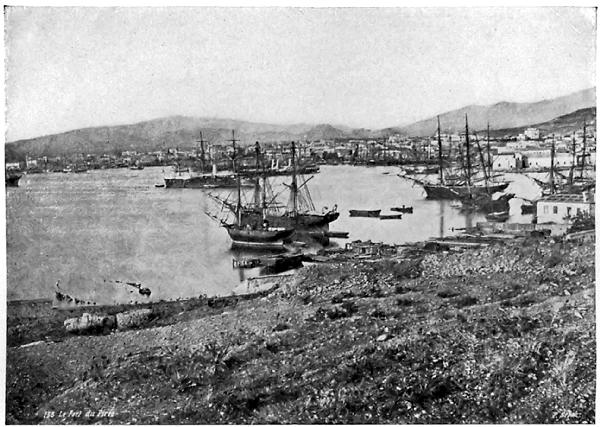

| Piræus, the Port of Athens | 213 |

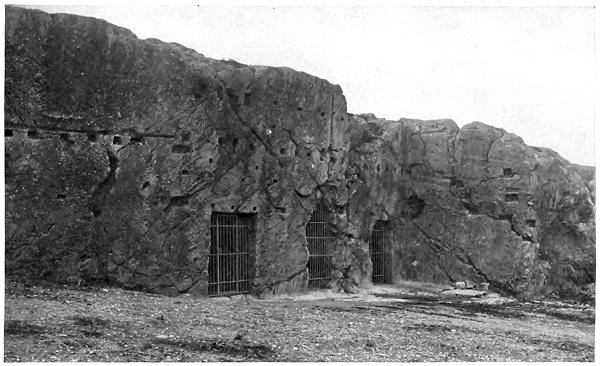

| Prison of Socrates, Athens | 229 |

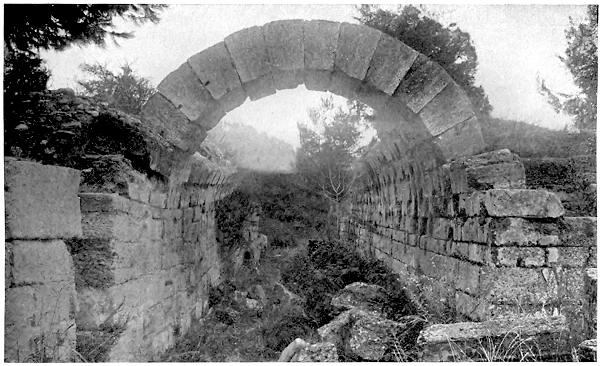

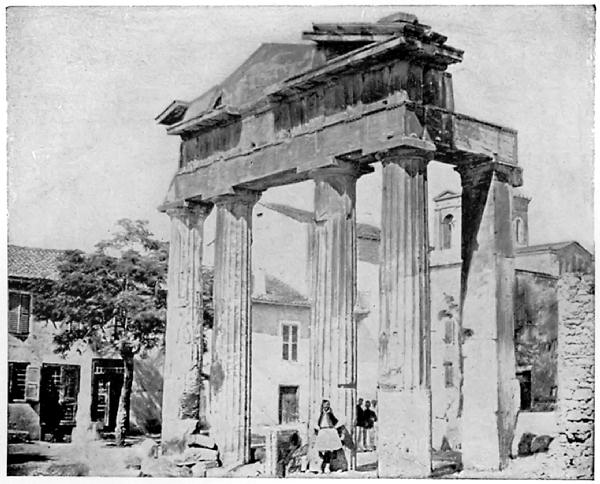

| Gate of the Agora, or Oil Market, Athens | 255 |

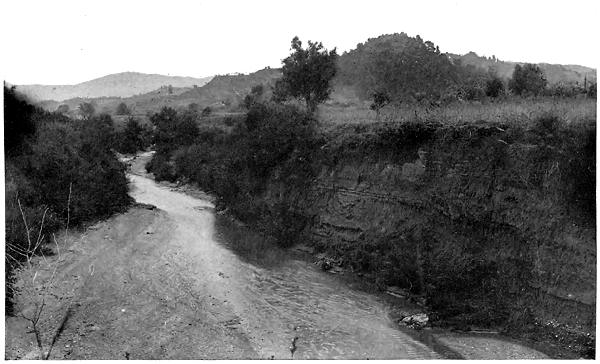

| Bed of the River Kladeos | 289 |

| The Death of Alexander the Great | 300 |

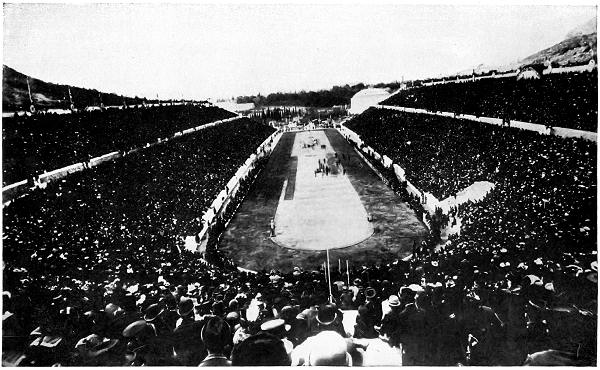

| The Modern Olympic Games in the Stadium | 316 |

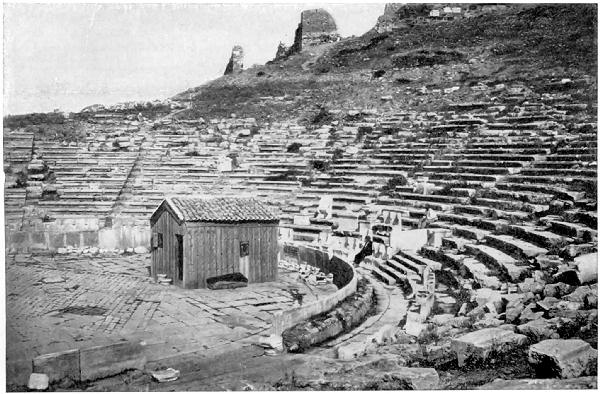

| The Theatre of Bacchus, Athens | 322 |

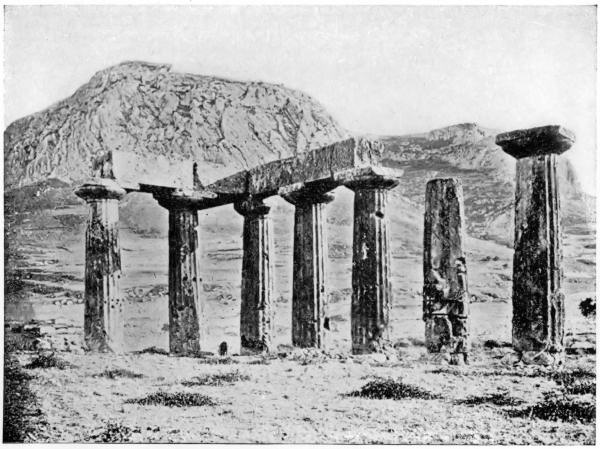

| Remains of the Temple of Minerva, Corinth | 345 |

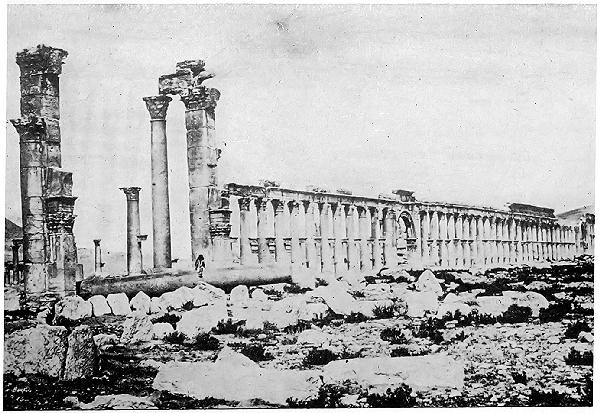

| The Ruins of Palmyra | 358 |

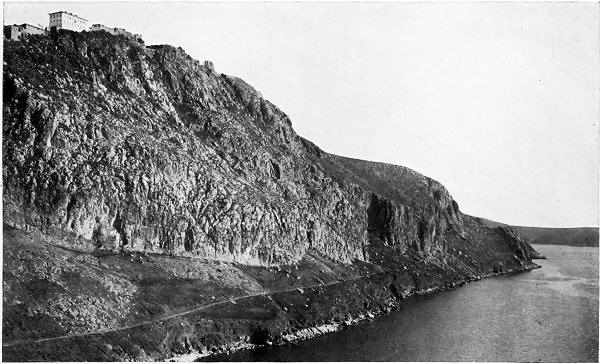

| Along the Coast of Greece | 362 |

The far-famed Helen, wife of King Menelaus of Sparta, was the most beautiful woman in the world. And from her beauty and faithlessness came the most celebrated of ancient wars, with death and disaster to numbers of famous heroes and the final ruin of the ancient city of Troy. The story of these striking events has been told only in poetry. We propose to tell it again in sober prose.

But warning must first be given that Helen and the heroes of the Trojan war dwelt in the mist-land of legend and tradition, that cloud-realm from which history only slowly emerged. The facts with which we are here concerned are those of the poet, not those of the historian. It is far from sure that Helen ever lived. It is far from sure that there ever was a Trojan war. Many people doubt the whole story. Yet the ancient Greeks accepted it as history, and as we are telling their story, we may fairly include it among the historical tales of Greece. The heroes concerned are certainly fully alive in Homer's great poem, the "Iliad," and we can do no better than follow the story of this stirring poem, while adding details from other sources.

Mythology tells us that, once upon a time, the[Pg 8] three goddesses, Venus, Juno, and Minerva, had a contest as to which was the most beautiful, and left the decision to Paris, then a shepherd on Mount Ida, though really the son of King Priam of Troy. The princely shepherd decided in favor of Venus, who had promised him in reward the love of the most beautiful of living women, the Spartan Helen, daughter of the great deity Zeus (or Jupiter). Accordingly the handsome and favored youth set sail for Sparta, bringing with him rich gifts for its beautiful queen. Menelaus received his Trojan guest with much hospitality, but, unluckily, was soon obliged to make a journey to Crete, leaving Helen to entertain the princely visitor. The result was as Venus had foreseen. Love arose between the handsome youth and the beautiful woman, and an elopement followed, Paris stealing away with both the wife and the money of his confiding host. He set sail, had a prosperous voyage, and arrived safely at Troy with his prize on the third day. This was a fortune very different from that of Ulysses, who on his return from Troy took ten years to accomplish a similar voyage.

As might naturally be imagined, this elopement excited indignation not only in the hearts of Menelaus and his brother Agamemnon, but among the Greek chieftains generally, who sympathized with the husband in his grief and shared his anger against Troy. War was declared against that faithless city, and most of the chiefs pledged themselves to take part in it, and to lend their aid until Helen was recovered or restored. Had they known all[Pg 9] that was before them they might have hesitated, since it took ten long years to equip the expedition, for ten years more the war continued, and some of the leaders spent ten years in their return. But in those old days time does not seem to have counted for much, and besides, many of the chieftains had been suitors for the hand of Helen, and were doubtless moved by their old love in pledging themselves to her recovery.

Some of them, however, were anything but eager to take part. Achilles and Ulysses, the two most important in the subsequent war, endeavored to escape this necessity. Achilles was the son of the sea-nymph Thetis, who had dipped him when an infant in the river Styx, the waters of which magic stream rendered him invulnerable to any weapon except in one spot,—the heel by which his mother had held him. But her love for her son made her anxious to guard him against every danger, and when the chieftains came to seek his aid in the expedition, she concealed him, dressed as a girl, among the maidens of the court. But the crafty Ulysses, who accompanied them, soon exposed this trick. Disguised as a pedler, he spread his goods, a shield and a spear among them, before the maidens. Then an alarm of danger being sounded, the girls fled in affright, but the disguised youth, with impulsive valor, seized the weapons and prepared to defend himself. His identity was thus revealed.

Ulysses himself, one of the wisest and shrewdest of men, had also sought to escape the dangerous expedition. To do so he feigned madness, and when[Pg 10] the messenger chiefs came to seek him they found him attempting to plough with an ox and a horse yoked together, while he sowed the field with salt. One of them, however, took Telemachus, the young son of Ulysses, and laid him in the furrow before the plough. Ulysses turned the plough aside, and thus showed that there was more method than madness in his mind.

And thus, in time, a great force of men and a great fleet of ships were gathered, there being in all eleven hundred and eighty-six ships and more than one hundred thousand men. The kings and chieftains of Greece led their followers from all parts of the land to Aulis, in Bœotia, whence they were to set sail for the opposite coast of Asia Minor, on which stood the city of Troy. Agamemnon, who brought one hundred ships, was chosen leader of the army, which included all the heroes of the age, among them the distinguished warriors Ajax and Diomedes, the wise old Nestor, and many others of valor and fame.

The fleet at length set sail; but Troy was not easily reached. The leaders of the army did not even know where Troy was, and landed in the wrong locality, where they had a battle with the people. Embarking again, they were driven by a storm back to Greece. Adverse winds now kept them at Aulis until Agamemnon appeased the hostile gods by sacrificing to them his daughter Iphigenia,—one of the ways which those old heathens had of obtaining fair weather. Then the winds changed, and the fleet made its way to the island of Tenedos, in the[Pg 11] vicinity of Troy. From here Ulysses and Menelaus were sent to that city as envoys to demand a return of Helen and the stolen property.

Meanwhile the Trojans, well aware of what was in store for them, had made abundant preparations, and gathered an army of allies from various parts of Thrace and Asia Minor. They received the two Greek envoys hospitably, paid them every attention, but sustained the villany of Paris, and refused to deliver Helen and the treasure. When this word was brought back to the fleet the chiefs decided on immediate war, and sail was made for the neighboring shores of the Trojan realm.

Of the long-drawn-out war that followed we know little more than what Homer has told us, though something may be learned from other ancient poems. The first Greek to land fell by the hand of Hector, the Trojan hero,—as the gods had foretold. But in vain the Trojans sought to prevent the landing; they were quickly put to rout, and Cycnus, one of their greatest warriors and son of the god Neptune, was slain by Achilles. He was invulnerable to iron, but was choked to death by the hero and changed into a swan. The Trojans were driven within their city walls, and the invulnerable Achilles, with what seems a safe valor, stormed and sacked numerous towns in the neighborhood, killed one of King Priam's sons, captured and sold as slaves several others, drove off the oxen of the celebrated warrior Æneas, and came near to killing that hero himself. He also captured and kept as his own prize a beautiful maiden named Briseis, and was even granted, through[Pg 12] the favor of the gods, an interview with the divine Helen herself.

This is about all we know of the doings of the first nine years of the war. What the Greeks were at during that long time neither history nor legend tells. The only other event of importance was the death of Palamedes, one of the ablest Grecian chiefs. It was he who had detected the feigned madness of Ulysses, and tradition relates that he owed his death to the revengeful anger of that cunning schemer, who had not forgiven him for being made to take part in this endless and useless war.

Thus nine years of warfare passed, and Troy remained untaken and seemingly unshaken. How the two hosts managed to live in the mean time the tellers of the story do not say. Thucydides, the historian, thinks it likely that the Greeks had to farm the neighboring lands for food. How the Trojans and their allies contrived to survive so long within their walls we are left to surmise, unless they farmed their streets. And thus we reach the opening of the tenth year and of Homer's "Iliad."

Homer's story is too long for us to tell in detail, and too full of war and bloodshed for modern taste. We can only give it in epitome.

Agamemnon, the leader of the Greeks, robs Achilles of his beautiful captive Briseis, and the invulnerable hero, furious at the insult, retires in sullen rage to his ships, forbids his troops to take part in the war, and sulks in anger while battle after battle is fought. Deprived of his mighty aid, the Greeks[Pg 13] find the Trojans quite their match, and the fortunes of the warring hosts vary day by day.

On a watch-tower in Troy sits Helen the beautiful, gazing out on the field of conflict, and naming for old Priam, who sits beside her, the Grecian leaders as they appear at the head of their hosts on the plain below. On this plain meet in fierce combat Paris the abductor and Menelaus the indignant husband. Vengeance lends double weight to the spear of the latter, and Paris is so fiercely assailed that Venus has to come to his aid to save him from death. Meanwhile a Trojan archer wounds Menelaus with an arrow, and a general battle ensues.

The conflict is a fierce one, and many warriors on both sides are slain. Diomedes, a bold Grecian chieftain, is the hero of the day. Trojans fall by scores before his mighty spear, he rages in fury from side to side of the field, and at length meets the great Æneas, whose thigh he breaks with a huge stone. But Æneas is the son of the goddess Venus, who flies to his aid and bears him from the field. The furious Greek daringly pursues the flying divinity, and even succeeds in wounding the goddess of love with his impious spear. At this sad outcome Venus, to whom physical pain is a new sensation, flies in dismay to Olympus, the home of the deities, and hides her weeping face in the lap of Father Jove, while her lady enemies taunt her with biting sarcasms. The whole scene is an amusing example of the childish folly of mythology.

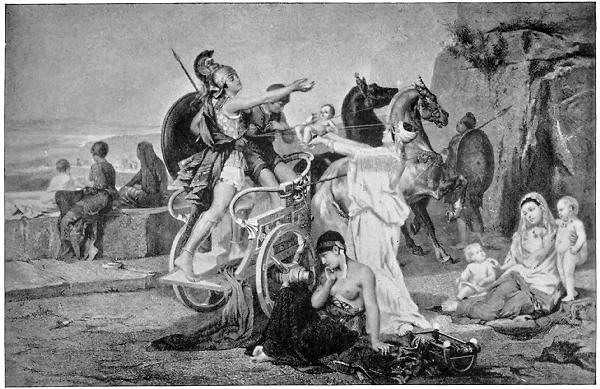

In the next scene a new hero appears upon the field, Hector, the warlike son of Priam, and next to[Pg 14] Achilles the greatest warrior of the war. He arms himself inside the walls, and takes an affectionate leave of his wife Andromache and his infant son, the child crying with terror at his glittering helmet and nodding plume. This mild demeanor of the warrior changes to warlike ardor when he appears upon the field. His coming turns the tide of battle. The victorious Greeks are driven back before his shining spear, many of them are slain, and the whole host is driven to its ships and almost forced to take flight by sea from the victorious onset of Hector and his triumphant followers. While the Greeks cower in their ships the Trojans spend the night in bivouac upon the field. Homer gives us a picturesque description of this night-watch, which Tennyson has thus charmingly rendered into English:

"As when in heaven the stars about the moon

Look beautiful, when all the winds are laid,

And every height comes out, and jutting peak

And valley, and the immeasurable heavens

Break open to their highest, and all the stars

Shine, and the shepherd gladdens in his heart;

So, many a fire between the ships and stream

Of Xanthus blazed before the towers of Troy,

A thousand on the plain; and close by each

Sat fifty in the blaze of burning fire;

And, champing golden grain, the horses stood

Hard by their chariots, waiting for the dawn."

Affairs had grown perilous for the Greeks. Patroclus, the bosom friend of Achilles, begged him to come to their aid. This the sulking hero would not do, but he lent Patroclus his armor, and permitted him to lead[Pg 15] his troops, the Myrmidons, to the field. Patroclus was himself a gallant and famous warrior, and his aid turned the next day's battle against the Trojans, who were driven back with great slaughter. But, unfortunately for this hero of the fight, a greater than he was in the field. Hector met him in the full tide of his success, engaged him in battle, killed him, and captured from his body the armor of Achilles.

THE PARTING OF HECTOR AND ANDROMACHE.

THE PARTING OF HECTOR AND ANDROMACHE.

The slaughter of his friend at length aroused the sullen Achilles to action. Rage against the Trojans succeeded his anger against Agamemnon. His lost armor was replaced by new armor forged for him by Vulcan, the celestial smith,—who fashioned him the most wonderful of shields and most formidable of spears. Thus armed, he mounted his chariot and drove at the head of his Myrmidons to the field, where he made such frightful slaughter of the Trojans that the river Scamander was choked with their corpses; and, indignant at being thus treated, sought to drown the hero for his offence. Finally he met Hector, engaged him in battle, and killed him with a thrust of his mighty spear. Then, fastening the corpse of the Trojan hero to his chariot, he dragged it furiously over the blood-soaked plain and around the city walls. Homer's story ends with the funeral obsequies of the slain Patroclus and the burial by the Trojans of Hector's recovered body.

Other writers tell us how the war went on. Hector was replaced by Penthesileia, the beautiful and warlike queen of the Amazons, who came to the aid of the Trojans, and drove the Greeks from the field. But, alas! she too was slain by the invincible[Pg 16] Achilles. Removing her helmet, the victor was deeply affected to find that it was a beautiful woman he had slain.

The mighty Memnon, son of godlike parents, now made his appearance in the Trojan ranks, at the head of a band of black Ethiopians, with whom he wrought havoc among the Greeks. At length Achilles encountered this hero also, and a terrible battle ensued, whose result was long in doubt. In the end Achilles triumphed and Memnon fell. But he died to become immortal, for his goddess mother prayed for and obtained for him the gift of immortal life.

Such triumphs were easy for Achilles, whose flesh no weapon could pierce; but no one was invulnerable to the poets, and his end came at last. He had routed the Trojans and driven them within their gates, when Paris, aided by Apollo, the divine archer, shot an arrow at the hero which struck him in his one pregnable spot, the heel. The fear of Thetis was realized, her son died from the wound, and a fierce battle took place for the possession of his body. This Ajax and Ulysses succeeded in carrying off to the Grecian camp, where it was burned on a magnificent funeral pile. Achilles, like his victim Memnon, was made immortal by the favor of the gods. His armor was offered as a prize to the most distinguished Grecian hero, and was adjudged to Ulysses, whereupon Ajax, his close contestant for the prize, slew himself in despair.

We cannot follow all the incidents of the [Pg 17]campaign. It will suffice to say that Paris was himself slain by an arrow, that Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles, took his place in the field, and that the Trojans suffered so severely at his hands that they took shelter behind their walls, whence they never again emerged to meet the Greeks in the field.

But Troy was safe from capture while the Palladium, a statue which Jupiter himself had given to Dardanus, the ancestor of the Trojans, remained in the citadel of that city. Ulysses overcame this difficulty. He entered Troy in the disguise of a wounded and ragged fugitive, and managed to steal the Palladium from the citadel. Then, as the walls of Troy still defied their assailants, a further and extraordinary stratagem was employed to gain access to the city. It seems a ridiculous one to us, but was accepted as satisfactory by the writers of Greece. This stratagem was the following:

A great hollow wooden horse, large enough to contain one hundred armed men, was constructed, and in its interior the leading Grecian heroes concealed themselves. Then the army set fire to its tents, took to its ships, and sailed away to the island of Tenedos, as if it had abandoned the siege. Only the great horse was left on the long-contested battle-field.

The Trojans, filled with joy at the sight of their departing foes, came streaming out into the plain, women as well as warriors, and gazed with astonishment at the strange monster which their enemies had left. Many of them wanted to take it into the city, and dedicate it to the gods as a mark of gratitude[Pg 18] for their deliverance. The more cautious ones doubted if it was wise to accept an enemy's gift. Laocoon, the priest of Neptune, struck the side of the horse with his spear. A hollow sound came from its interior, but this did not suffice to warn the indiscreet Trojans. And a terrible spectacle now filled them with superstitious dread. Two great serpents appeared far out at sea and came swimming inward over the waves. Reaching the shore, they glided over the land to where stood the unfortunate Laocoon, whose body they encircled with their folds. His son, who came to his rescue, was caught in the same dreadful coils, and the two perished miserably before the eyes of their dismayed countrymen.

There was no longer any talk of rejecting the fatal gift. The gods had given their decision. A breach was made in the walls of Troy, and the great horse was dragged with exultation within the stronghold that for ten long years had defied its foe.

Riotous joy and festivity followed in Troy. It extended into the night. While this went on Sinon, a seeming renegade who had been left behind by the Greeks, and who had helped to deceive the Trojans by lying tales, lighted a fire-signal for the fleet, and loosened the bolts of the wooden horse, from whose hollow depths the hundred weary warriors hastened to descend.

And now the triumph of the Trojans was changed to sudden woe and dire lamentation. Death followed close upon their festivity. The hundred warriors attacked them at their banquets, the returned fleet disgorged its thousands, who poured through[Pg 19] the open gates, and death held fearful carnival within the captured city. Priam was slain at the altar by Neoptolemus. All his sons fell in death. The city was sacked and destroyed. Its people were slain or taken captive. Few escaped, but among these was Æneas, the traditional ancestor of Rome. As regards Helen, the cause of the war, she was recovered by Menelaus, and gladly accompanied him back to Sparta. There she lived for years afterwards in dignity and happiness, and finally died to become happily immortal in the Elysian fields.

But our story is not yet at an end. The Greeks had still to return to their homes, from which they had been ten years removed. And though Paris had crossed the intervening seas in three days, it took Ulysses ten years to return, while some of his late companions failed to reach their homes at all. Many, indeed, were the adventures which these home-sailing heroes were destined to encounter.

Some of the Greek warriors reached home speedily and were met with welcome, but others perished by the way, while Agamemnon, their leader, returned to find that his wife had been false to him, and perished by her treacherous hand. Menelaus wandered long through Egypt, Cyprus, and elsewhere before he reached his native land. Nestor and several others went to Italy, where they founded cities. Diomedes also became a founder of cities, and various others seem to have busied themselves in this same useful occupation. Neoptolemus made his way to Epirus, where he became king of the Molossians. Æneas, the Trojan hero, sought Carthage, whose[Pg 20] queen Dido died for love of him. Thence he sailed to Italy, where he fought battles and won victories, and finally founded the city of Rome. His story is given by Virgil, in the poem of the "Æneid." Much more might be told of the adventures of the returning heroes, but the chief of them all is that related of the much wandering Ulysses, as given by Homer in his epic poem the "Odyssey."

The story of the "Odyssey" might serve us for a tale in itself, but as it is in no sense historical we give it here in epitome.

We are told that during the wanderings of Ulysses his island kingdom of Ithaca had been invaded by a throng of insolent suitors of his wife Penelope, who occupied his castle and wasted his substance in riotous living. His son Telemachus, indignant at this, set sail in search of his father, whom he knew to be somewhere upon the seas. Landing at Sparta, he found Menelaus living with Helen in a magnificent castle, richly ornamented with gold, silver, and bronze, and learned from him that his father was then in the island of Ogygia, where he had been long detained by the nymph Calypso.

The wanderer had experienced numerous adventures. He had encountered the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, who feasted on the fattest of the Greeks, while the others escaped by boring out his single eye. He had passed the land of the Lotus-Eaters, to whose magic some of the Greeks succumbed. In the island of Circe some of his followers were turned into swine. But the hero overcame this enchantress, and while in her land visited the realm of the [Pg 21]departed and had interviews with the shades of the dead. He afterwards passed in safety through the frightful gulf of Scylla and Charybdis, and visited the wind-god Æolus, who gave him a fair wind home, and all the foul winds tied up in a bag. But the curious Greeks untied the bag, and the ship was blown far from her course. His followers afterwards killed the sacred oxen of the sun, for which they were punished by being wrecked. All were lost except Ulysses, who floated on a mast to the island of Calypso. With this charming nymph he dwelt for seven years.

Finally, at the command of the gods, Calypso set her willing captive adrift on a raft of trees. This raft was shattered in a storm, but Ulysses swam to the island of Phæacia, where he was rescued by Nausicaa, the king's daughter, and brought to the palace. Thence, in a Phæacian ship, he finally reached Ithaca.

Here new adventures awaited him. He sought his palace disguised as an old beggar, so that of all there, only his old dog knew him. The faithful animal staggered to his feet, feebly expressed his joy, and fell dead. Telemachus had now returned, and led his disguised father into the palace, where the suitors were at their revels. Penelope, instructed what to do, now brought forth the bow of Ulysses, and offered her hand to any one of the suitors who could bend it. It was tried by them all, but tried in vain. Then the seeming beggar took in his hand the stout, ashen bow, bent it with ease, and with wonderful skill sent an arrow hurtling through the[Pg 22] rings of twelve axes set up in line. This done, he turned the terrible bow upon the suitors, sending its death-dealing arrows whizzing through their midst. Telemachus and Eumæus, his swine-keeper, aided him in this work of death, and a frightful scene of carnage ensued, from which not one of the suitors escaped with his life.

In the end the hero, freed from his ragged attire, made himself known to his faithful wife, defeated the friends of the suitors, and recovered his kingdom from his foes. And thus ends the final episode of the famous tale of Troy.

We are forced to approach the historical period of Greece through a cloud-land of legend, in which atones of the gods are mingled with those of men, and the most marvellous of incidents are introduced as if they were everyday occurrences. The Argonautic expedition belongs to this age of myth, the vague vestibule of history. It embraces, as does the tale of the wanderings of Ulysses, very ancient ideas of geography, and many able men have treated it as the record of an actual voyage, one of the earliest ventures of the Greeks upon the unknown seas. However this be, this much is certain, the story is full of romantic and supernatural elements, and it was largely through these that it became so celebrated in ancient times.

The story of the voyage of the ship Argo is a tragedy. Pelias, king of Ioleus, had consulted an oracle concerning the safety of his dominions, and was warned to beware of the man with one sandal. Soon afterwards Jason (a descendant of Æolus, the wind god) appeared before him with one foot unsandalled. He had lost his sandal while crossing a swollen stream. Pelias, anxious to rid himself of this visitor, against whom the oracle had warned[Pg 24] him, gave to Jason the desperate task of bringing back to Locus the Golden Fleece (the fleece of a speaking ram which had borne Phryxus and Helle through the air from Greece, and had reached Colchis in Asia Minor, where it was dedicated to Mars, the god of war).

Jason, young and daring, accepted without hesitation the perilous task, and induced a number of the noblest youth of Greece to accompany him in the enterprise. Among these adventurers were Hercules, Theseus, Castor, Pollux, and many others of the heroes of legend. The way to Colchis lay over the sea, and a ship was built for the adventurers named the Argo, in whose prow was inserted a piece of timber cut from the celebrated speaking oak of Dodona.

The voyage of the Argo was as full of strange incidents as those which Ulysses encountered in his journey home from Troy. Land was first reached on the island of Lemnos. Here no men were found. It was an island of women only. All the men had been put to death by the women in revenge for ill-treatment, and they held the island as their own. But these warlike matrons, who had perhaps grown tired of seeing only each other's faces, received the Argonauts with much friendship, and made their stay so agreeable that they remained there for several months.

Leaving Lemnos, they sailed along the coast of Thrace, and up the Hellespont (a strait which had received its name from Helle, who, while riding on the golden ram in the air above it, had fallen and[Pg 25] been drowned in its waters). Thence they sailed along the Propontis and the coast of Mysia, not, as we may be sure, without adventures. In the country of the Bebrycians the giant king Amycus challenged any of them to box with him. Pollux accepted the challenge, and killed the giant with a blow. Next they reached Bithynia, where dwelt the blind prophet Phineus, to whom their coming proved a blessing.

Phineus had been blinded by Neptune, as a punishment for having shown Phryxus the way to Colchis. He was also tormented by the harpies, frightful winged monsters, who flew down from the clouds whenever he attempted to eat, snatched the food from his lips, and left on it such a vile odor that no man could come near it. He, being a prophet, knew that the Argonauts would free him from this curse. There were with them Zetes and Calias, winged sons of Boreas, the god of the north winds; and when the harpies descended again to spoil the prophet's meal, these winged warriors not only drove them away, but pursued them through the air. They could not overtake them, but the harpies were forbidden by Jupiter to molest Phineus any longer.

The blind prophet, grateful for this deliverance, told the voyagers how they might escape a dreadful danger which lay in their onward way. This came from the Symplegades, two rocks between which their ships must pass, and which continually opened and closed, with a violent collision, and so swiftly that even a bird could scarce fly through the opening in safety. When the Argo reached the dangerous[Pg 26] spot, at the suggestion of Phineus, a dove was let loose. It flew with all speed through the opening, but the rocks clashed together so quickly behind it that it lost a few feathers of its tail. Now was their opportunity. The rowers dashed their ready oars into the water, shot forward with rapid speed, and passed safely through, only losing the ornaments at the stern of their ship. Their escape, however, they owed to the goddess Minerva, whose strong hand held the rocks asunder during the brief interval of their passage. It had been decreed by the gods that if any ship escaped these dreadful rocks they should forever cease to move. The escape of the Argo fulfilled this decree, and the Symplegades have ever since remained immovable.

Onward went the daring voyagers, passing in their journey Mount Caucasus, on whose bare rock Prometheus, for the crime of giving fire to mankind, was chained, while an eagle devoured his liver. The adventurers saw this dread eagle and heard the groans of the sufferer himself. Helpless to release him whom the gods had condemned, they rowed rapidly away.

Finally Colchis was reached, a land then ruled over by King Æetes, from whom the heroes demanded the golden fleece, stating that they had been sent thither by the gods themselves. Æetes heard their request with anger, and told them that if they wanted the fleece they could have it on one condition only. He possessed two fierce and tameless bulls, with brazen feet and fire-breathing nostrils. These had been the gift of the god Vulcan. Jason[Pg 27] was told that if he wished to prove his descent from the gods and their sanction of his voyage, he must harness these terrible animals, plough with them a large field, and sow it with dragons' teeth.

Perilous as this task seemed, each of the heroes was eager to undertake it, but Jason, as the leader of the expedition, took it upon himself. Fortune favored him in the desperate undertaking. Medea, the daughter of Æetes, who knew all the arts of magic, had seen the handsome youth and fallen in love with him at sight. She now came to his aid with all her magic. Gathering an herb which had grown where the blood of Prometheus had fallen, she prepared from it a magical ointment which, when rubbed on Jason's body, made him invulnerable either to fire or weapons of war. Thus prepared, he fearlessly approached the fire-breathing bulls, yoked them unharmed, and ploughed the field, in whose furrows he then sowed the dragons' teeth. Instantly from the latter sprang up a crop of armed men, who turned their weapons against the hero. But Jason, who had been further instructed by Medea, flung a great stone in their midst, upon which they began to fight each other, and he easily subdued them all.

Jason had accomplished his task, but Æetes proved unfaithful to his words. He not only withheld the prize, but took steps to kill the Argonauts and burn their vessel. They were invited to a banquet, and armed men were prepared to murder them during the night after the feast. Fortunately, sleep overcame [Pg 28]the treacherous king, and the adventurers warned of their danger, made ready to fly. But not without the golden fleece. This was guarded by a dragon, but Medea prepared a potion that put this perilous sentinel to sleep, seized the fleece, and accompanied Jason in his flight, taking with her on the Argo Absyrtus, her youthful brother.

The Argonauts, seizing their oars, rowed with all haste from the dreaded locality. Æetes, on awakening, learned with fury of the loss of the fleece and his children, hastily collected an armed force, and pursued with such energy that the flying vessel was soon nearly overtaken. The safety of the adventurers was again due to Medea, who secured it by a terrible stratagem. This was, to kill her young brother, cut his body to pieces, and fling the bleeding fragments into the sea. Æetes, on reaching the scene of this tragedy, recognized these as the remains of his murdered son, and sorrowfully stopped to collect them for interment. While he was thus engaged the Argonauts escaped.

But such a wicked deed was not suffered to go unpunished. Jupiter beheld it with deep indignation, and in requital condemned the Argonauts to a long and perilous voyage, full of hardship and adventure. They were forced to sail over all the watery world of waters, so far as then known. Up the river Phasis they rowed until it entered the ocean which flows round the earth. This vast sea or stream was then followed to the source of the Nile, down which great river they made their way into the land of Egypt.

Here, for some reason unknown, they did not follow[Pg 29] the Nile to the Mediterranean, but were forced to take the ship Argo on their shoulders and carry it by a long overland journey to Lake Tritonis, in Libya. Here they were overcome by want and exhaustion, but Triton, the god of the region, proved hospitable, and supplied them with the much-needed food and rest. Thus refreshed, they launched their ship once more on the Mediterranean and proceeded hopefully on their homeward way.

Stopping at the island of Ææa, its queen Circe—she who had transformed the companions of Ulysses into swine—purified Medea from the crime of murder; and at Corcyra, which they next reached, the marriage of Jason and Medea took place. The cavern in that island where the wedding was solemnized was still pointed out in historical times.

After leaving Corcyra a fierce storm threatened the navigators with shipwreck, from which they were miraculously saved by the celestial aid of the god Apollo. An arrow shot from his golden bow crossed the billows like a track of light, and where it pierced the waves an island sprang up, on whose shores the imperilled mariners found a port of refuge. On this island, Anaphe by name, the grateful Argonauts built an altar to Apollo and instituted sacrifices in his honor.

Another adventure awaited them on the coast of Crete. This island was protected by a brazen sentinel, named Talos, wrought by Vulcan, and presented by him to King Minos to protect his realm. This living man of brass hurled great rocks at the vessel, and destruction would have overwhelmed the[Pg 30] voyagers but for Medea. Talos, like all the invulnerable men of legend, had his one weak point. This her magic art enabled her to discover, and, as Paris had wounded Achilles in the heel, Medea killed this vigilant sentinel by striking him in his vulnerable spot.

The Argonauts now landed and refreshed themselves. In the island of Ægina they had to fight to procure water. Then they sailed along the coasts of Eubœa and Locris, and finally entered the gulf of Pagasæ and dropped anchor at Iolceus, their starting-point.

As to what became of the ship Argo there are two stories. One is that Jason consecrated his vessel to Neptune on the isthmus of Corinth. Another is that Minerva translated it to the stars, where it became a constellation.

So ends the story of this earliest of recorded voyages, whose possible substratum of fact is overlaid deeply with fiction, and whose geography is similarly a strange mixture of fact and fancy. Yet though the voyage is at an end, our story is not. We have said that it was a tragedy, and the denouement of the tragedy remains to be given.

Pelias, who had sent Jason on this long voyage to escape the fate decreed for him by the oracle, took courage from his protracted absence, and put to death his father and mother and his infant brother. On learning of this murderous act Jason determined on revenge. But Pelias was too strong to be attacked openly, so the hero employed a strange stratagem, suggested by the cunning magician Medea. He and[Pg 31] his companions halted at some distance from Iolcus, while Medea entered the town alone, pretending that she was a fugitive from the ill-treatment of Jason.

Here she was entertained by the daughters of Pelias, over whom she gained great influence by showing them certain magical wonders. In the end she selected an old ram from the king's flocks, cut him up and boiled him in a caldron with herbs of magic power. In the end the animal emerged from the caldron as a young and vigorous lamb. The enchantress now told her dupes that their old father could in the same way be made young again. Fully believing her, the daughters cut the old man to pieces in the same manner, and threw his limbs into the caldron, trusting to Medea to restore him to life as she had the ram.

Leaving them for the assumed purpose of invoking the moon, as a part of the ceremony, Medea ascended to the roof of the palace. Here she lighted a fire-signal to the waiting Argonauts, who instantly burst into and took possession of the town.

Having thus revenged himself, Jason yielded the crown of Iolcus to the son of Pelias, and withdrew with Medea to Corinth, where they resided together for ten years. And here the final act in the tragedy was played.

After these ten years of happy married life, during which several children were born, Jason ceased to love his wife, and fixed his affections on Glauce, the daughter of King Creon of Corinth. The king[Pg 32] showed himself willing to give Jason his daughter in marriage, upon which the faithless hero divorced Medea, who was ordered to leave Corinth. He should have known better with whom he had to deal. The enchantress, indignant at such treatment, determined on revenge. Pretending to be reconciled to the coming marriage, she prepared a poisoned robe, which she sent as a wedding-present to the hapless Glauce. No sooner had the luckless bride put on this perilous gift than the robe burst into flames, and she was consumed; while her father, who sought to tear from her the fatal garment, met with the same fate.

Medea escaped by means of a chariot drawn by winged serpents, sent her by her grandfather Helios (the sun). As the story is told by Euripides, she killed her children before taking to flight, leaving their dead bodies to blast the sight of their horror-stricken father. The legend, however, tells a different tale. It says that she left them for safety before the altar in the temple of Juno; and that the Corinthians, furious at the death of their king, dragged the children from the altar and put them to death. As for the unhappy Jason, the story goes that he fell asleep under the ship Argo, which had been hauled ashore according to the custom of the ancients, and that a fragment of this ship fell upon and killed him.

The flight of Medea took her to Athens, where she found a protector and second husband in Ægeus, the ruler of that city, and father of Theseus, the great legendary hero of Athens.

Minos, king of Crete in the age of legend, made war against Athens in revenge for the death of his son. This son, Androgeos by name, had shown such strength and skill in the Panathenaic festival that Ægeus, the Athenian king, sent him to fight with the flame-spitting bull of Marathon, a monstrous creature that was ravaging the plains of Attica. The bull killed the valiant youth, and Minos, furious at the death of his son, laid siege to Athens.

As he proved unable to capture the city, he prayed for aid to his father Zeus (for, like all the heroes of legend, he was a son of the gods). Zeus sent pestilence and famine on Athens, and so bitter grew the lot of the Athenians that they applied to the oracles of the gods for advice in their sore strait, and were bidden to submit to any terms which Minos might impose. The terms offered by the offended king of Crete were severe ones. He demanded that the Athenians should, at fixed periods, send to Crete seven youths and seven maidens, as victims to the insatiable appetite of the Minotaur.

This fabulous creature was one of those destructive monsters of which many ravaged Greece in the age[Pg 34] of fable. It had the body of a man and the head of a bull, and so great was the havoc it wrought among the Cretans that Minos engaged the great artist Dædalus to construct a den from which it could not escape. Dædalus built for this purpose the Labyrinth, a far-extending edifice, in which were countless passages, so winding and intertwining that no person confined in it could ever find his way out again. It was like the catacombs of Rome, in which one who is lost is said to wander helplessly till death ends his sorrowful career. In this intricate puzzle of a building the Minotaur was confined.

Every ninth year the fourteen unfortunate youths and maidens had to be sent from Athens to be devoured by this insatiate beast. We are not told on what food it was fed in the interval, or why Minos did not end the trouble by allowing it to starve in its inextricable den. As the story goes, the living tribute was twice sent, and the third period came duly round. The youths and maidens to be devoured were selected by lot from the people of Athens, and left their city amid tears and woe. But on this occasion Theseus, the king's son and the great hero of Athens, volunteered to be one of the band, and vowed either to slay the terrible beast or die in the attempt.

There seem to have been few great events in those early days of Greece in which Theseus did not take part. Among his feats was the carrying off of Helen, the famous beauty, while still a girl. He then took part in a journey to the under-world,—the realm of ghosts,—during which Castor and Pollux, the[Pg 35] brothers of Helen, rescued and brought her home. He was also one of the heroes of the Argonautic expedition and of an expedition against the Amazons, or nation of women warriors; he fought with and killed a series of famous robbers; and he rid the world of a number of ravaging beasts,—the Calydonian boar, the Crommyonian sow, and the Marathonian bull, the monster which had slain the son of Minos. He was, in truth, the Hercules of ancient Athens, and he now proposed to add to his exploits a battle for life or death with the perilous Minotaur.

The hero knew that he had before him the most desperate task of his life. Even should he slay the monster, he would still be in the intricate depths of the Labyrinth, from which escape was deemed impossible, and in whose endless passages he and his companions might wander until they died of weariness and starvation. He prayed, therefore, to Neptune for help, and received a message from the oracle at Delphi to the effect that Aphrodite (or Venus) would aid and rescue him.

The ship conveying the victims sailed sadly from Athens, and at length reached Crete at the port of Knossus, the residence of King Minos. Here the woful hostages were led through the streets to the prison in which they were to be confined till the next day, when they were to be delivered to death. As they passed along the people looked with sympathy upon their fair young faces, and deeply lamented their coming fate. And, as Venus willed, among the spectators were Minos and his fair daughter Ariadne, who stood at the palace door to see them pass.

The eyes of the young princess fell upon the face of Theseus, the Athenian prince, and her heart throbbed with a feeling she had never before known. Never had she gazed upon a man who seemed to her half so brave and handsome as this princely youth. All that night thoughts of him drove slumber from her eyes. In the early morning, moved by a new-born love, she sought the prison, and, through her privilege as the king's daughter, was admitted to see the prisoners. Venus was doing the work which the oracle had promised.

Calling Theseus aside, the blushing maiden told him of her sudden love, and that she ardently longed to save him. If he would follow her directions he would escape. She gave him a sword, which she had taken from her father's armory and concealed beneath her cloak, that he might be armed against the devouring beast. And she provided him besides with a ball of thread, bidding him to fasten the end of it to the entrance of the Labyrinth, and unwind it as he went in, that it might serve him as a clue to find his way out again.

As may well be believed, Theseus warmly thanked his lovely visitor, told her that he was a king's son, and that he returned her love, and begged her, in case he escaped, to return with him to Athens and be his bride. Ariadne willingly consented, and left the prison before the guards came to conduct the victims to their fate. It was like the story of Jason and Medea retold.

With hidden sword and clue Theseus followed the guards, in the midst of his fellow-prisoners. They[Pg 37] were led into the depths of the Labyrinth and there left to their fate. But the guards had failed to observe that Theseus had fastened his thread at the entrance and was unwinding the ball as he went. And now, in this dire den, for hours the hapless victims awaited their destiny. Mid-day came, and with it a distant roar from the monster reverberated frightfully through the long passages. Nearer came the blood-thirsty brute, his bellowing growing louder as he scented human beings. The trembling victims waited with but a single hope, and that was in the sword of their valiant prince. At length the creature appeared, in form a man of giant stature, but with the horned head and huge mouth of a bull.

Battle at once began between the prince and the brute. It soon ended. Springing agilely behind the ravening monster, Theseus, with a swinging stroke of his blade, cut off one of its legs at the knee. As the man-brute fell prone, and lay bellowing with pain, a thrust through the back reached its heart, and all peril from the Minotaur was at an end.

This victory gained, the task of Theseus was easy. The thread led back to the entrance. By aid of this clue the door of escape was quickly gained. Waiting until night, the hostages left the dreaded Labyrinth under cover of the darkness. Ariadne was in waiting, the ship was secretly gained, and the rescued Athenians with their fair companion sailed away, unknown to the king.

But Theseus proved false to the maiden to whom he owed his life. Stopping at the island of Naxos, which was sacred to Dionysus (or Bacchus), the god[Pg 38] of wine, he had a dream in which the god bade him to desert Ariadne and sail away. This the faithless swain did, leaving the weeping maiden deserted on the island. Legend goes on to tell us that the despair of the lamenting maiden ended in the sleep of exhaustion, and that while sleeping Dionysus found her, and made her his wife. As for the dream of Theseus, it was one of those convenient excuses which traitors to love never lack.

Meanwhile, Theseus and his companions sailed on over the summer sea. Reaching the isle of Delos, he offered a sacrifice to Apollo in gratitude for his escape, and there he, and the merry youths and maidens with him, danced a dance called the Geranus, whose mazy twists and turns imitated those of the Labyrinth.

But the faithless swain was not to escape punishment for his base desertion of Ariadne. He had arranged with his father Ægeus that if he escaped the Minotaur he would hoist white sails in the ship on his return. If he failed, the ship would still wear the black canvas with which she had set out on her errand of woe.

The aged king awaited the returning ship on a high rock that overlooked the sea. At length it hove in sight, the sails appeared, but—they were black. With broken heart the father cast himself from the rock into the sea,—which ever since has been called, from his name, the Ægean Sea. Theseus, absorbed perhaps in thoughts of the abandoned Ariadne, perhaps of new adventures, had forgotten to make the promised change. And thus was the[Pg 39] deserted maiden avenged on the treacherous youth who owed to her his life.

The ship—or what was believed to be the ship—of Theseus and the hostages was carefully preserved at Athens, down to the time of the Macedonian conquest, being constantly repaired with new timbers, till little of the original ship remained. Every year it was sent to Delos with envoys to sacrifice to Apollo. Before the ship left port the priest of Apollo decorated her stern with garlands, and during her absence no public act of impurity was permitted to take place in the city. Therefore no one could be put to death, and Socrates, who was condemned at this period of the year, was permitted to live for thirty days until the return of the sacred ship.

There is another legend connected with this story worth telling. Dædalus, the builder of the Labyrinth, at length fell under the displeasure of Minos, and was confined within the windings of his own edifice. He had no clue like Theseus, but he had resources in his inventive skill. Making wings for himself and his son Icarus, the two flew away from the Labyrinth and their foe. The father safely reached Sicily; but the son, who refused to be governed by his father's wise advice, flew so high in his ambitious folly that the sun melted the wax of which his wings were made, and he fell into the sea near the island of Samos. This from him was named the Icarian Sea.

There is a political as well as a legendary history of Theseus,—perhaps one no more to be depended upon than the other. It is said that when he [Pg 40]became king he made Athens supreme over Attica, putting an end to the separate powers of the tribes which had before prevailed. He is also said to have abolished the monarchy, and replaced it by a government of the people, whom he divided into the three classes of nobles, husbandmen, and artisans. He died at length in the island of Scyrus, where he fell or was thrown from the cliffs. Ages later, after the Persian war, the Delphic oracle bade the Athenians to bring back the bones of Theseus from Scyrus, and bury them splendidly in Attic soil. Cimon, the son of Miltiades, found—or pretended to find—the hero's tomb, and returned with the famous bones. They were buried in the heart of Athens, and over them was erected the monument called the Theseium, which became afterwards a place of sanctuary for slaves escaping from cruel treatment and for all persons in peril. Theseus, who had been the champion of the oppressed during life, thus became their refuge after death.

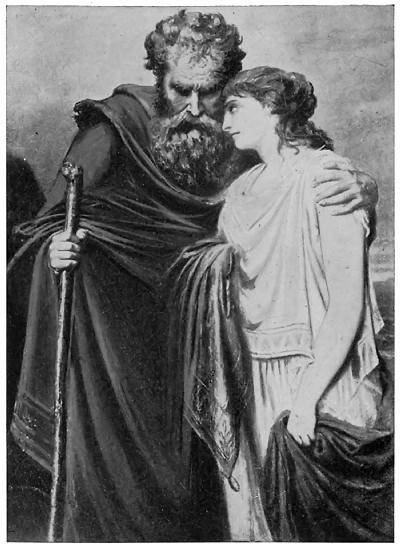

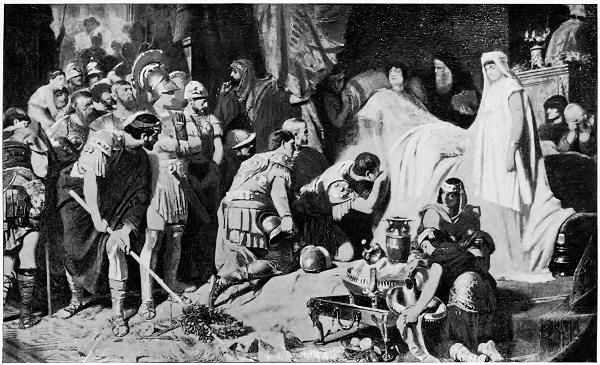

Among the legendary tales of Greece, none of which are strictly, though several are perhaps partly, historical, none—after that of Troy—was more popular with the ancients than the story of the two sieges of Thebes. This tale had probably in it an historical element, though deeply overlaid with myth, and it was the greatest enterprise of Grecian war, after that of Troy, during what is called the age of the Heroes. And in it is included one of the most pathetic episodes in the story of Greece, that of the sisterly affection and tragic fate of Antigone, whose story gave rise to noble dramas by the tragedians Æschylus and Sophocles, and is still a favorite with lovers of pathetic lore.

As a prelude to our story we must glance at the mythical history of Œdipus, which, like that of his noble daughter, has been celebrated in ancient drama. An oracle had declared that he should kill his father, the king of Thebes. He was, in consequence, brought up in ignorance of his parentage, yet this led to the accomplishment of the oracle, for as a youth he, during a roadside squabble, killed his father not knowing him. For this crime, which had been one of their own devising, the gods, with their usual[Pg 42] inconsistency, punished the land of Thebes; afflicting that hapless country with a terrible monster called the Sphinx, which had the face of a woman, the wings of a bird, and the body of a lion. This strangely made-up creature proposed a riddle to the Thebans, whose solution they were forced to try and give; and on every failure to give the correct answer she seized and devoured the unhappy aspirant. Œdipus arrived, in ignorance of the fact that he was the son of the late king. He quickly solved the riddle of the Sphinx, whereupon that monster committed suicide, and he was made king. He then married the queen,—not knowing that she was his own mother.

ŒDIPUS AND ANTIGONE.

ŒDIPUS AND ANTIGONE.

This celebrated riddle of the Sphinx was not a very difficult one. It was as follows: "A being with four feet has two feet and three feet; but its feet vary, and when it has most it is weakest."

The answer, as given by Œdipus, was "Man," who

"First as a babe four-footed creeps on his way,

Then, when full age cometh on, and the burden of years weighs full heavy,

Bending his shoulders and neck, as a third foot useth his staff."

When the truth became known—as truth was apt to become known when too late in old stories—the queen, Jocasta, mad with anguish, hanged herself, and Œdipus, in wild despair, put out his eyes. The gods who had led him blindly into crime, now handed him over to punishment by the Furies,—the ancient goddesses of vengeance, whose mission it was to pursue the criminal with stinging whips.

The tragic events which followed arose from the curse of the afflicted Œdipus. He had two sons, Polynikes and Eteocles, who twice offended him without intention, and whom he, frenzied by his troubles, twice bitterly cursed, praying to the gods that they might perish by each other's hands. Œdipus afterwards obtained the pardon of the gods for his involuntary crime, and died in exile, leaving Creon, the brother of Jocasta, on the throne. But though he was dead, his curse kept alive, and brought on new matter of dire moment.

It began its work in a quarrel between the two sons as to who should succeed their uncle as king of Thebes. Polynikes was in the wrong, and was forced to leave Thebes, while Eteocles remained. The exiled prince sought the court of Adrastus, king of Argos, who gave him his daughter in marriage, and agreed to assist in restoring him to his native country.

Most of the Argive chiefs joined in the proposed expedition. But the most distinguished of them all, Amphiaraüs, opposed it as unjust and against the will of the gods. He concealed himself, lest he should be forced into the enterprise. But the other chiefs deemed his aid indispensable, and bribed his wife, with a costly present, to reveal his hiding-place. Amphiaraüs was thus forced to join the expedition, but his prophetic power taught him that it would end in disaster to all and death to himself, and as a measure of revenge he commanded his son Alkmæon to kill the faithless woman who had betrayed him, and after his death to organize a second expedition against Thebes.

Seven chiefs led the army, one to assail each of the seven celebrated gates of Thebes. Onward they marched against that strong city, heedless of the hostile portents which they met on their way. The Thebans also sought the oracle of the gods, and were told that they should be victorious, but only on the dread condition that Creon's son, Menœceus, should sacrifice himself to Mars. The devoted youth, on learning that the safety of his country depended on his life, forthwith killed himself before the city gates,—thus securing by innocent blood the powerful aid of the god of war.

Long and strenuous was the contest that succeeded, each of the heroes fiercely attacking the gate adjudged to him. But the gods were on the side of the Thebans and every assault proved in vain. Parthenopæus, one of the seven, was killed by a stone, and another, Capaneus, while furiously mounting the walls from a scaling-ladder, was slain by a thunderbolt cast by Jupiter, and fell dead to the earth.

The assailants, terrified by this portent, drew back, and were pursued by the Thebans, who issued from their gates. But the battle that was about to take place on the open plain was stopped by Eteocles, who proposed to settle it by a single combat with his brother Polynikes, the victory to be given to the side whose champion succeeded in this mortal duel. Polynikes, filled with hatred of his brother, eagerly accepted this challenge. Adrastus, the leader of the assailing army, assented, and the unholy combat began.

Never was a more furious combat than that [Pg 45]between the hostile brothers. Each was exasperated to bitter hatred of the other, and they fought with a violence and desperation that could end only in the death of one of the combatants. As it proved, the curse of Œdipus was in the keeping of the gods, and both fell dead,—the fate for which their aged father had prayed. But the duel had decided nothing, and the two armies renewed the battle.

And now death and bloodshed ran riot; men fell by hundreds; deeds of heroic valor were achieved on either side; feats of individual daring were displayed like those which Homer sings in the story of Troy. But the battle ended in the defeat of the assailants. Of the seven leaders only two survived, and one of these, Amphiaraüs, was about to suffer the fate he had foretold, when Jupiter rescued him from death by a miracle. The earth opened beneath him, and he, with his chariot and horses, was received unhurt into her bosom. Rendered immortal by the king of the gods, he was afterwards worshipped as a god himself.

Adrastus, the only remaining chief, was forced to fly, and was preserved by the matchless speed of his horse. He reached Argos in safety, but brought with him nothing but "his garment of woe and his black-maned steed."

Thus ended, in defeat and disaster to the assailants, the first of the celebrated sieges of Thebes. It was followed by a tragic episode which remains to be told, that of the sisterly fidelity of Antigone and her sorrowful fate. Her story, which the dramatists have made immortal, is thus told in the legend.

After the repulse of his foes, King Creon caused the body of Eteocles to be buried with the highest honors; but that of Polynikes was cast outside the gates as the corpse of a traitor, and death was threatened to any one who should dare to give it burial. This cruel edict, which no one else ventured to ignore, was set aside by Antigone, the sister of Polynikes. This brave maiden, with warm filial affection, had accompanied her blind father during his exile to Attica, and was now returned to Thebes to perform another holy duty. Funeral rites were held by the Greeks to be essential to the repose of the dead, and Antigone, despite Creon's edict, determined that her brother's body should not be left to the dogs and vultures. Her sister, though in sympathy with her purpose, proved too timid to help her. No other assistance was to be had. But not deterred by this, she determined to perform the act alone, and to bury the body with her own hands.

In this act of holy devotion Antigone succeeded; Polynikes was buried. But the sentinels whom Creon had posted detected her in the act, and she was seized and dragged before the tribunal of the tyrant. Here she defended her action with an earnestness and dignity that should have gained her release, but Creon was inflexible in his anger. She had set at naught his edict, and should suffer the penalty for her crime. He condemned her to be buried alive.

Sophocles, the dramatist, puts noble words into the mouth of Antigone. This is her protest against the tyranny of the king:

[Pg 47]"No ordinance of man shall override

The settled laws of Nature and of God;

Not written these in pages of a book,

Nor were they framed to-day, nor yesterday;

We know not whence they are; but this we know,

That they from all eternity have been,

And shall to all eternity endure."

And when asked by Creon why she had dared disobey the laws, she nobly replied,—

"Not through fear

Of any man's resolve was I prepared

Before the gods to bear the penalty

Of sinning against these. That I should die

I knew (how should I not?) though thy decree

Had never spoken. And before my time

If I shall die, I reckon this a gain;

For whoso lives, as I, in many woes,

How can it be but he shall gain by death?"

At the king's command the unhappy maiden was taken from his presence and thrust into a sepulchre, where she was condemned to perish in hunger and loneliness. But Antigone was not without her advocate. She had a lover,—almost the only one in Greek literature. Hæmon, the son of Creon, to whom her hand had been promised in marriage, and who loved her dearly, appeared before his father and earnestly interceded for her life. Not on the plea of his love,—such a plea would have had no weight with a Greek tribunal,—but on those of mercy and justice. His plea was vain; Creon was obdurate: the unhappy lover left his presence and sought Antigone's living tomb, where he slew himself at[Pg 48] the feet of his love, already dead. His mother, on learning of his fatal act, also killed herself by her own hand, and Creon was left alone to suffer the consequences of his unnatural act.

The story goes on to relate that Adrastus, with the disconsolate mothers of the fallen chieftains, sought the hero Theseus at Athens, and begged his aid in procuring the privilege of interment for the slain warriors whose bodies lay on the plain of Thebes. The Thebans persisting in their refusal to permit burial, Theseus at length led an army against them, defeated them in the field, and forced them to consent that their fallen foes should be interred, that last privilege of the dead which was deemed so essential by all pious Greeks. The tomb of the chieftains was shown near Eleusis within late historical times.

But the Thebans were to suffer another reverse. The sons of the slain chieftains raised an army, which they placed under the leadership of Adrastus, and demanded to be led against Thebes. Alkmæon, the son of Amphiaraüs, who had been commanded to revenge him, played the most prominent part in the succeeding war. As this new expedition marched, the gods, which had opposed the former with hostile signs, now showed their approval with favorable portents. Adherents joined them on their march. At the river Glisas they were met by a Theban army, and a battle was fought, which ended in a complete victory over the Theban foe. A prophet now declared to the Thebans that the gods were against them, and advised them to surrender the[Pg 49] city. This they did, flying themselves, with their wives and children, to the country of the Illyrians, and leaving their city empty to the triumphant foe. The Epigoni, as the youthful victors were called, marched in at the head of their forces, took possession, and placed Thersander, the son of Polynikes, on the throne. And thus ends the famous old legend of the two sieges of Thebes.

Of the many nations between which the small peninsula of Greece was divided, much the most interesting were those whose chief cities were Athens and Sparta. These are the states with whose doings history is full, and without which the history of ancient Greece would be little more interesting to us than the history of ancient China and Japan. No two cities could have been more opposite in character and institutions than these, and they were rivals of each other for the dominant power through centuries of Grecian history. In Athens freedom of thought and freedom of action prevailed. Such complete political equality of the citizens has scarcely been known elsewhere upon the earth, and the intellectual activity of these citizens stands unequalled. In Sparta freedom of thought and action were both suppressed to a degree rarely known, the most rigid institutions existed, and the only activity was a warlike one. All thought and all education had war for their object, and the state and city became a compact military machine. This condition was the result of a remarkable code of laws by which Sparta was governed, the most peculiar and surprising code which any nation has ever possessed. It is this[Pg 51] code, and Lycurgus, to whom Sparta owed it, with which we are now concerned.

First, who was Lycurgus and in what age did he live? Neither of these questions can be closely answered. Though his laws are historical, his biography is legendary. He is believed to have lived somewhere about 800 or 900 B.C., that age of legend and fable in which Homer lived, and what we know about him is little more to be trusted than what we know about the great poet. The Greeks had stories of their celebrated men of this remote age, but they were stories with which imagination often had more to do than fact, and though we may enjoy them, it is never quite safe to believe them.

As for the very uncertain personage named Lycurgus, we are told by Herodotus, the Greek historian, that when he was born the Spartans were the most lawless of the Greeks. Every man was a law unto himself, and confusion, tumult, and injustice everywhere prevailed. Lycurgus, a noble Spartan, sad at heart for the misery of his country, applied to the oracle at Delphi, and received instructions as to how he should act to bring about a better state of affairs.

Plutarch, who tells so many charming stories about the ancient Greeks and Romans, gives us the following account. According to him the brother of Lycurgus was king of Sparta. When he died Lycurgus was offered the throne, but he declined the honor and made his infant nephew, Charilaus, king. Then he left Sparta, and travelled through Crete, Ionia, Egypt, and several more remote [Pg 52]countries, everywhere studying the laws and customs which he found prevailing. In Ionia he obtained a copy of the poems of Homer, and is said by some to have met and conversed with Homer himself. If, as is supposed, the Greeks of that age had not the art of writing, he must have carried this copy in his memory.

On his return home from this long journey Lycurgus found his country in a worse state than before. Sparta, it may be well here to say, had always two kings; but it found, as might have been expected, that two kings were worse than one, and that this odd device in government never worked well. At any rate, Lycurgus found that law had nearly vanished, and that disorder had taken its place. He now consulted the oracle at Delphi, and was told that the gods would support him in what he proposed to do.

Coming back to Sparta, he secretly gathered a body-guard of thirty armed men from among the noblest citizens, and then presented himself in the Agora, or place of public assembly, announcing that he had come to end the disorders of his native land. King Charilaus at first heard of this with terror, but on learning what his uncle intended, he offered his support. Most of the leading men of Sparta did the same. Lycurgus was to them a descendant of the great hero Hercules, he was the most learned and travelled of their people, and the reforms he proposed were sadly needed in that unhappy land.

These reforms were of two kinds. He desired to reform both the government and society. We[Pg 53] shall deal first with the new government which he instituted. The two kings were left unchanged. But under them was formed a senate of twenty-eight members, to whom the kings were joined, making thirty in all. The people also were given their assemblies, but they could not debate any subject, all the power they had was to accept or reject what the senate had decreed. At a later date five men, called ephors, were selected from the people, into whose hands fell nearly all the civil power, so that the kings had little more to do than to command the army and lead it to war. The kings, however, were at the head of the religious establishment of the country, and were respected by the people as descendants of the gods.

The government of Sparta thus became an aristocracy or oligarchy. The ephors came from the people, and were appointed in their interest, but they came to rule the state so completely that neither the kings, the senate, nor the assembly had much voice in the government. Such was the outgrowth of the governmental institutions of Lycurgus.

It is the civil laws made by Lycurgus, however, which are of most interest, and in which Sparta differed from all other states. The people of Laconia, the country of which Sparta was the capital, were composed of two classes. That country had originally been conquered by the Spartans, and the ancient inhabitants, who were known as Helots, were held as slaves by their Spartan conquerors. They tilled the ground to raise food for the citizens, who were all soldiers, and whose whole life and[Pg 54] thought were given to keeping the Helots in slavery and to warlike activity. That they might make the better soldiers, Lycurgus formed laws to do away with all luxury and inequality of conditions, and to train up the young under a rigid system of discipline to the use of weapons and the arts of war. The Helots, also, were often employed as light-armed soldiers, and there was always danger that they might revolt against their oppressors, a fact which made constant discipline and vigilance necessary to the Spartan citizens.

Lycurgus found great inequality in the state. A few owned all the land, and the remainder were poor. The rich lived in luxury; the poor were reduced to misery and want. He divided the whole territory of Sparta into nine thousand equal lots, one of which was given to each citizen. The territory of the remainder of Laconia was divided into thirty thousand equal lots, one of which was given to each Periœcus. (The Periœci were the freemen of the country outside of the Spartan city and district, and did not possess the full rights of citizenship.)

This measure served to equalize wealth. But further to prevent luxury, Lycurgus banished all gold and silver from the country, and forced the people to use iron money,—each piece so heavy that none would care to carry it. He also forbade the citizens to have anything to do with commerce or industry. They were to be soldiers only, and the Helots were to supply them with food. As for commerce, since no other state would accept their iron[Pg 55] money, they had to depend on themselves for everything they needed. The industries of Laconia were kept strictly at home.

To these provisions Lycurgus added another of remarkable character. No one was allowed to take his meals at home. Public tables were provided, at which all must eat, every citizen being forced to belong to some special public mess. Each had to supply his quota of food, such as barley, wine, cheese, and figs from his land, game obtained by hunting, or the meat of the animals killed for sacrifices. At these tables all shared alike. The kings and the humblest citizens were on an equality. No distinction was permitted except to those who had rendered some signal service to the state.

This public mess was not accepted without protest. Those who were used to luxurious living were not ready to be brought down to such simple fare, and a number of these attacked Lycurgus in the market-place, and would have stoned him to death had he not run briskly for his life. As it was, one of his pursuers knocked out his eye. But, such was his content at his success, that he dedicated his last eye to the gods, building a temple to the goddess Athené of the Eye. At these public tables black broth was the most valued dish, the elder men eating it in preference, and leaving the meat to their younger messmates.

The houses of the Spartans were as plain as they could well be made, and as simple in furniture as possible, while no lights were permitted at bedtime, it being designed that every one should become [Pg 56]accustomed to walking boldly in the dark. This, however, was but a minor portion of the Spartan discipline. Throughout life, from boyhood to old age, every one was subjected to the most rigorous training. From seven years of age the drill continued, and everyone was constantly being trained or seeing others under training. The day was passed in public exercises and public meals, the nights in public barracks. Married Spartans rarely saw their wives—during the first years of marriage—and had very little to do with their children; their whole lives were given to the state, and the slavery of the Helots to them was not more complete than their slavery to military discipline.

They were not only drilled in the complicated military movements which taught a body of Spartan soldiers to act as one man, but also had incessant gymnastic training, so as to make them active, strong, and enduring. They were taught to bear severe pain unmoved, to endure heat and cold, hunger and thirst, to walk barefoot on rugged ground, to wear the same garment summer and winter, to suppress all display of feeling, and in public to remain silent and motionless until action was called for.

Two companies were often matched against each other, and these contests were carried on with fury, fists and feet taking the place of arms. Hunting in the woods and mountains was encouraged, that they might learn to bear fatigue. The boys were kept half fed, that they might be forced to provide for themselves by hunting or stealing. The latter[Pg 57] was designed to make them cunning and skilful, and if detected in the act they were severely punished. The story is told that one boy who had stolen a fox and hidden it under his garment, permitted the animal to tear him open with claws and teeth, and died rather than reveal his theft.

One might say that he would rather have been born a girl than a boy in Sparta; but the girls were trained almost as severely as the boys. They were forced to contend with each other in running, wrestling, and boxing, and to go through other gymnastic exercises calculated to make them strong and healthy. They marched in the religious processions, sung and danced at festivals, and were present at the exercises of the youths. Thus boys and girls were continually mingled, and the praise or reproach of the latter did much to stimulate their brothers and friends to the utmost exertion.

As a result of all this the Spartans became strong, vigorous, and handsome in form and face. The beauty of their women was everywhere celebrated. The men became unequalled for soldierly qualities, able to bear the greatest fatigue and privation, and to march great distances in a brief time, while on the field of battle they were taught to conquer or to die, a display of cowardice or flight from the field being a lifelong disgrace.

Such were the main features of the most singular set of laws any nation ever had, the best fitted to make a nation of soldiers, and also to prevent intellectual progress in any other direction than the single one of war-making. Even eloquence in speech[Pg 58] was discouraged, and a brief or laconic manner sedulously cultivated. But while all this had its advantages, it had its defects. The number of citizens decreased instead of increasing. At the time of the Persian war there were eight thousand of them. At a late date there were but seven hundred, of whom one hundred possessed most of the land. Whether Lycurgus really divided the land equally or not is doubtful. At any rate, in time the land fell into a few hands, the poor increased in number, and the people steadily died out; while the public mess, so far as the rich were concerned, became a mere form.

But we need not deal with these late events, and must go back to the story told of Lycurgus. It is said that when he had completed his code of laws, he called together an assembly of the people, told them that he was going on a journey, and asked them to swear that they would obey his laws till he returned. This they agreed to do, the kings, the senate, and the people all taking the oath.

Then the law-giver went to Delphi, where he offered a sacrifice to Apollo, and asked the oracle if the laws he had made were good. The oracle answered that they were excellent, and would bring the people the greatest fame. This answer he had put into writing and sent to Sparta, for he had resolved to make his oath binding for all time by never returning. So the old man starved himself to death.