W.H.G. Kingston

"Norman Vallery"

Chapter One.

Just come from India.

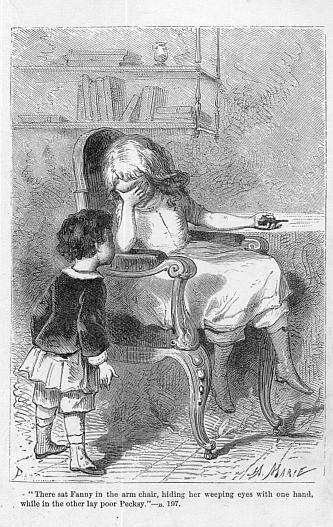

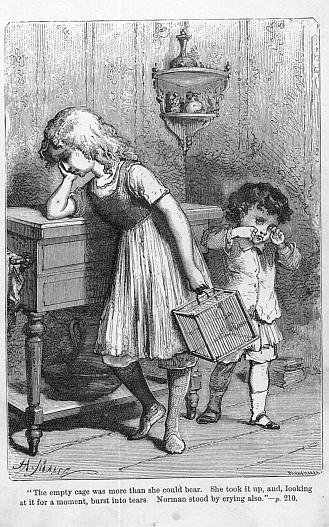

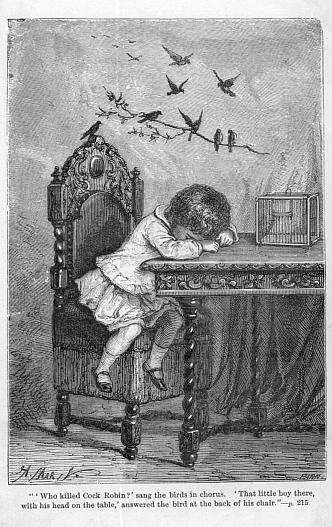

“Are they really coming to-morrow, granny?” exclaimed Fanny Vallery, a fair, blue-eyed, sweet-looking girl, as she gazed eagerly at the face of Mrs Leslie, who was seated in an arm-chair, near the drawing-room window. “Oh, how I long to see papa, and mamma, and dear little Norman! I have thought, and thought so much about them; and India is so far off it seemed as if they would never reach England.”

“Your mamma writes me word from Paris that they hope to cross the Channel to-night, and be here early in the afternoon,” answered Mrs Leslie, looking at the open letter which she held in her hand. “I too long to see your dear mamma; and had it not been for you, my own darling, I should have missed her even more than I have done; but you have ever been a good, obedient, loving child, and my greatest comfort during her absence.”

Mrs Leslie, as she spoke, drew her grandchild towards her, and kissed her brow.

Fanny said nothing, but, pressing the hand which held hers, turned her eyes towards her grandmamma’s face, while the consciousness that the praise was not wrongly bestowed, caused a bright gleam of pleasure to pass over her countenance.

Mrs Leslie, who had brought up Fanny from her infancy, lived in a pretty villa a few miles from London, surrounded by shrubberies, with a lawn and beautifully-kept flower-garden in front. On one side was a poultry-yard, over which Fanny presided as the reigning sovereign; and even Trusty, the spaniel, who considered himself if not the ruler at all events the guardian of the rest of the premises, when he ventured into her domain always followed humbly at her heels, never presuming to interfere with her feathered subjects. More than once he had been known to turn tail and fly as if for his life when Phoebe, the bantam hen, with extended neck and outspread wings had run after him, as he had by chance approached nearer to her brood of fledglings than she had approved of.

Fanny with her fowls, Trusty, and Kitty, the tortoiseshell cat; and her doll, which had a house of its own fitted with furniture; and, more than all, with the consciousness of her granny’s affection, considered herself one of the happiest little girls in existence. Everybody in the house, indeed, loved her; and she was kind, and gentle, and loving to every one in return.

Her mamma—Mrs Leslie’s only daughter—had married Captain Vallery, an officer in the Indian army, while he was at home on leave, and had accompanied him to the East. She returned three or four years afterwards, in consequence of ill health, bringing with her little Fanny, who, when she went back to her husband, was left under charge of her mother, Mrs Leslie.

Great as was Mrs Vallery’s grief at parting from her child, she well knew, from her own experience, with what wise and loving care she would be brought up.

Captain Vallery was of a French Protestant family, but having been partly educated in England, and having English relations, he had entered the British army. He was considered an honourable and brave officer, and was a very kind husband, but Mrs Vallery discovered that he had certain peculiar notions which were not likely to make him bring up his children as she would desire. One of his notions was, that boys especially, in order to develop their character, as he said, should always be allowed to have their own way.

“But, my dear husband,” she pleaded, “suppose that way should prove to be a bad way, what then will be the consequence?”

“Oh, but our little Norman is a perfect cherub, surely he can have nothing bad about him, and I must insist that no one curbs his fine and noble temper, lest his young spirit should be broken and irretrievably ruined,” answered Captain Vallery. “I say, let the boy have his own way, and you will see what a fine fellow he will become.”

Mrs Vallery sighed—she knew that it would be useless to contend with her husband, though she feared, should his plan be persevered in, it would entail many a severe trial on her boy in future years.

Of this Mrs Leslie had some suspicions, though Fanny, who had pictured her little brother as all she could wish him to be, looked forward with unmitigated pleasure to having him as her companion.

With eager interest she assisted Susan, the housemaid, in preparing the rooms for the expected guests; for she was a notable little woman, and she had been encouraged by her grandmamma to busy herself in household matters. She with much taste arranged the bouquets in the vases on her mamma’s dressing-table, and then she went into the little room next her own, in which Norman was to sleep, and placed some flowers in that also, as well as three or four of her prettiest picture-books, which she had carefully preserved, thinking that they might amuse him. Gently, too, she smoothed down his pillow, and, after everything was in order, went back delighted to make her report to granny.

How her heart beat when a carriage drove up to the door, with a gentleman and lady in it, whom she knew must be her papa and mamma, while on the coach box was seated a young boy. “What a fine, noble, little fellow he is,” she thought to herself, as the boy scrambled down without waiting for the assistance of any one.

The next instant she scarcely knew what was happening—every one seemed so full of confused delight. She felt that she was in her mother’s arms, who, still holding her, threw herself into those of granny. Then her papa, a fine, handsome gentleman, took her up and kissed her again and again; and next, she saw the little boy who had come in with a whip in his hand; she sprang towards him exclaiming, “You are Norman!” and, following the impulse of heart, covered his face with kisses.

“Yes, that’s my name,” answered the boy, “and you are the sister Fanny I was told I should see; and is that old woman there granny? Will she want to kiss me as you have done? I hope she won’t, for I do not choose to be treated as a baby.”

Happily Mrs Leslie did not hear these remarks; they grieved Fanny sorely.

“Oh but dear granny will love you as she does me, and you must come to her as I am sure she wants to see you,” she whispered gently. “Then you shall go out with me, and I will show you my poultry and Trusty and all sorts of things, which I am sure you will like.”

“Come along then,” said Norman, “I shall like to see the things you talk of.”

“Not surely till you have spoken to granny, but afterwards I will gladly take you,” said Fanny, and she led him up to Mrs Leslie.

Though his grandmamma kissed him several times, he behaved better than might have been expected, restraining for a wonder his impatience, somewhat awed perhaps by the dignified manner of the old lady.

“And now, Fanny, I am ready to see what you have got to show me,” he exclaimed, as Mrs Leslie taking her daughter’s arm led her into the drawing-room.

Captain Vallery cast a proud glance at his two beautiful children as hand in hand they ran upstairs.

“Here is my doll’s house,” said Fanny, as she led Norman into her neat bed-chamber; “see, it has a drawing-room, with sofas and chairs and looking-glasses, and a dining-room, with a long table and plates and dishes and knives and forks on it; and this is the kitchen, with its stove and pots and pans; and here is the bedroom, where little Nancy sleeps. She is a dear good child, and never cries, but as I have had her for a long time, she is not as pretty as she used to be. I tell granny that she was a poor neglected little orphan, and that she came begging at the door one day, and as she had no one to look after her, I took her in, and that is the reason she has so many knocks and bruises.”

Fanny, as she spoke, drew out a small doll, dressed in a cotton frock, from the doll’s house, and held it up to Norman.

“It does look just like a wretched beggar child,” he observed; “I wonder you can care for such a thing. If I were you I should throw it out of the window, and tell papa he must get another much prettier, dressed like a fine lady, who would be fit to walk out with you, and you need not be ashamed of, as I should think you must be of Nancy, as you call her.”

“Oh, but I love Nancy very much,” said Fanny; “she and I have known each other very many years, and I would not throw her away on any account. If I ever get a finer doll, I can let Nancy attend on her, I am sure she will be very glad to do that, for she is not a bit proud, and wishes, I am sure, to be a good girl and please everybody.”

“You may think more of her than I do,” remarked Norman, “and now, as I am not a baby, and do not care about dolls, won’t you show me some of the other things you talk of?”

“Oh yes!” said Fanny, “I will take you to my poultry-yard, but I must carry Nancy with me as she has not been out all day, and she will like to see me feed my hens. They are all very fond of me, and I hope they will learn to know you, Norman, too, and come when you call them, and eat out of your hand, as they do out of mine, especially Thisbe, who is the tamest of all, and the fondest of me.”

“I do not know that I care about cocks and hens and those sort of creatures, but I will go with you,” answered Norman, tucking his whip under his arm and accompanying Fanny.

“O Miss Fanny,” said Susan, whom they met on the way with a china vase in her hand, “your grandmamma says that your papa is fond of flowers, and that we ought to have put some on the mantelpiece of his dressing-room. Will you come and help me to pick them, and will you arrange them, as you can do so beautifully?”

Fanny gladly undertook to do as Susan asked her, and told Norman that after she had picked the flowers she would take him into the poultry-yard. Putting down her doll with her back against a clump of box, she, with a smile at her own conceit, begged him while she was engaged to try and amuse Nancy by telling her something about India or his voyage home. “Stuff!” he replied in a grumpy tone, and turned away, while his sister began to pick the flowers. One side of the yard, composed of trellis work, it should be said, was close to the garden, so that the fowls running about within could easily be seen through the bars. A door, also of trellis work, opened from the garden into the yard.

Norman though he did not care much about seeing the poultry, felt vexed and angry that Susan should venture to draw off his sister’s attention from himself, and stood with his finger in his mouth watching them as they were engaged in picking the flowers.

The hens which had espied their young mistress, had gathered near the side of the yard, and Thisbe, Fanny’s favourite hen, was making strenuous efforts to get out. Norman had strolled up to the door, and finding that he could lift the latch opened it, and out ran Mistress Thisbe. Fanny, not observing what had happened just then, called to Norman, and asked him to hold the vase, that she might arrange the flowers within it. He had taken it in his hands, when at that moment Trusty, who had been snuffing about the rooms, not perfectly satisfied as yet that the newly arrived strangers had a right to enter them, espying Fanny in the garden came bounding towards her. He gave vent as he saw Norman to a short bark, as much as to ask, “Who are you?” but Norman, not accustomed to dogs in India, and already in no very amiable mood, became alarmed, and dashing the vase at Trusty’s head, seized his whip, with which he began lashing about in all directions at everybody and everything he saw near him.

Susan seeing his alarm rushed forward, intending to assist him, but what between anger and fear his temper was now fairly aroused, and instead of thanking her, he turned round and bestowed on her a lash with his whip, which made her run off to call Mrs Vallery, thinking that his mamma would be better able to manage him than she could.

His gentle sister came in for the next assault of his blind rage, and she fled with her doll, which she had snatched up in her arms, feeling that the wisest thing just then to do was to get out of his way.

Trusty, unaccustomed to the blows which Norman now liberally bestowed, scampered off in one direction, while Thisbe the hen took to flight in another, and the young gentleman remained as he believed himself the victor of the field, shouting out:—

“I will have no one interfere with me, either maid-servants or dogs or fowls: I will soon show who is master here!” and again he shouted and bawled and waved his whip.

Poor Fanny who had never before seen a person in a passion, stood by trembling at a little distance while Master Norman walked up and down shouting out that he would whip any one who came in his way, and that the ugly dog would soon learn what to expect if he dared to bark at him again. Fanny entreated him to be quiet. “I am sure Trusty had no wish to frighten you, Norman,” she said, “if you will keep your whip quiet and call to him he will come up wagging his tail and soon be friends with you.”

Norman, however, instead of doing as his sister advised, flourished his whip more vehemently and shouted louder than ever, walking up and down and trampling on the flowers which had been scattered on the ground.

In the meantime Susan had reached the drawing-room where Mrs Vallery was reclining on the sofa to rest after the fatigue of her journey.

“Please marm,” said Susan as she entered, “I am sorry to say that the young gentleman is in such a tantrum that I do not know what to do with him, and I am afraid he will make himself ill. He won’t listen to his sister or to me, but if you will just come and speak to him, perhaps he will be quiet.”

“If you will excuse me, mamma, I will go to the poor child,” said Mrs Vallery rising.

“Could you not let Susan bring him here? He of course will come if she tells him that you have sent for him,” observed Mrs Leslie.

“I am afraid that he might refuse,” answered Mrs Vallery, “he is not always as obedient as I could desire.”

Mrs Vallery hurried out to Norman.

“My dear child, what is the matter?” she exclaimed, as she saw him still flourishing his whip and looking very angry and red in the face.

“The hen flew at me, and the dog barked, and I threw the jar at their heads, and Fanny has been scolding ever since, and I will not stand it,” shouted Norman.

“Come in with me, my dear child,” said Mrs Vallery soothingly. “I am sure Fanny did not intend to scold you.”

“Indeed, I did not, mamma,” cried Fanny, running up and kissing Norman. “Trusty barked only in play, and I am sure would not hurt him for the world. You must make friends with Trusty, Norman, and he will then do anything you tell him, and will never bark at you again.”

At length Norman, becoming calmer, consented to accompany his mamma into the house. Fanny ran upstairs and brought down one of the picture-books with the pictures, in which she tried to amuse him by telling him stories about them, for she found that he was unable to read the descriptions which were placed below them, or on the opposite pages.

At last she saw that he had fallen asleep in the arm-chair on which he was seated, so she put a cushion under his head that he might rest more comfortably, and finding that he was not likely to awake, she stole out that she might gather some more flowers instead of those which had been scattered on the ground when Norman broke the vase, and which he had trampled on while he was angrily stamping about on the gravel walk.

She watched for an opportunity while her papa was out of his room, and placed the fresh bouquet on his mantelpiece.

The day passed away without any other adventure, and as Norman having slept but little on board the steamer was very tired, Mrs Vallery carried him up to bed at an early hour.

“Now, my dear child, kneel down and say your prayers,” she said when she had undressed him.

“No, I won’t!” answered Norman, “I am too tired, I want to go to sleep.”

His mamma knew that it would be useless to argue with him, so with a sigh she placed him in his bed, and kneeling down, prayed that God would change him, for her love did not prevent her from seeing that his present heart was hard and bad, and that none of the qualities she desired him to possess could spring out of it.

She sat by his bedside till he was asleep, and then went back to Mrs Leslie.

Sweet Fanny felt sadly hurt and disappointed at the behaviour of her young brother, whom she had naturally expected to find as loving, and gentle, and ready to be pleased as she was. She consoled herself, however, with the thought that he was tired and out of sorts after his long journey, and hoped that the next day he would become more amiable and more like what she had fancied him to be.

Sleep soon visited her eyelids and as she was a brisk active little girl, she was awake betimes.

She had said her prayers and read a chapter in the Bible, which she did every morning to herself, and was waiting for Susan to assist her in putting on her frock when her mamma came into her room.

“My dear Fanny, I shall be so much obliged to you if you will assist Norman to dress; I am afraid that I shall be late for breakfast if I attempt to do so, as he is apt to dawdle over the business when I go to him,” said Mrs Vallery, giving her a kiss and admiring her fresh and blooming countenance. “He has been awake for some time, and as he does not know how to amuse himself he may perhaps be doing some mischief,” she continued. “He misses his ayah, his native nurse, who declined accompanying us farther than Alexandria, so you must be prepared to find him a little troublesome, but I hope he will improve.”

“Oh, I shall be delighted, mamma, to help Norman, and I daresay I shall have nothing to complain of,” answered Fanny, and without waiting to put on her frock she accompanied her mamma to the door of Norman’s room.

“You will be a good boy, and let Fanny help you dress, my dear,” said Mrs Vallery, putting in her head.

Fanny entered as her mamma withdrew, and having kissed Norman, arranged his clothes in readiness to put them on. She then poured out some water for him to wash his face.

“Shall I help you?” she asked, getting a towel ready.

“No, I can do it myself,” he answered, snatching the towel from her hand. “I don’t like to have my nose rubbed up the wrong way, and my eyes filled with soapsuds. I can wash my face as much as it wants. It isn’t dirty, I should think,” and dipping a corner of the towel in the water he began to dab himself all over with it cautiously as if he was afraid of rubbing off his skin.

“There, that will do,” he said, drying himself much in the same fashion. “I am ready to put on my clothes.”

“But you have not washed your neck or shoulders at all,” said Fanny, “and if you will let me, and bend down your head over the basin, I will pour the water upon it and give you a pleasant shower-bath this warm morning.”

“I have washed enough, and do not intend to wash any more,” answered Norman in a determined tone. “Where is my vest?”

Fanny, seeing that it would be useless to contend further on that point, assisted him to dress, and buttoned or tied the clothes which required buttoning or tying. When, however, she brought him his stockings, he took it into his head that he would not put them on.

“I can do very well without them,” he exclaimed, throwing himself into an arm-chair.

“There, you stand by my side, and wait till I want you to help me, just as my ayah used to do—the wicked old thing would not come on with us because I one day spit at her and called her a name she did not like. I can talk Hindostanee as well as English, I suppose you can’t,” and Master Norman uttered some words which sounded in Fanny’s ears very much like gibberish.

She waited patiently for some minutes, hoping that her brother would let her finish his toilet. At last, knowing that it was nearly time for her to go down and make the tea, she brought his stockings and attempted to put one of them on.

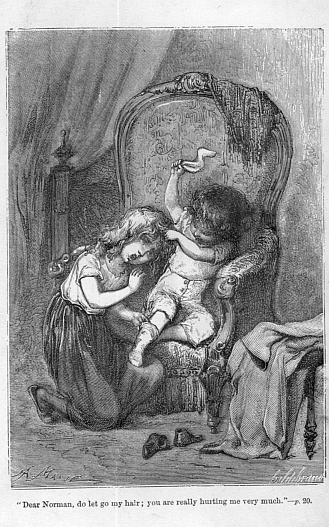

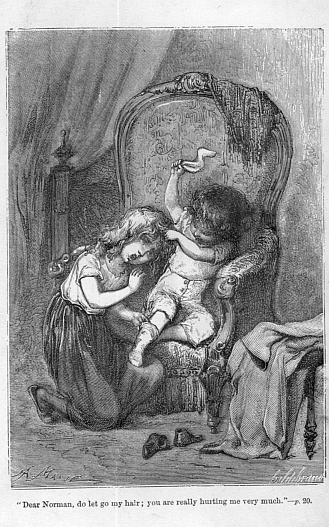

“I told you to wait till I was ready,” he exclaimed, and as she determined if possible on this occasion not to be defeated, stooped down to draw on one of his stockings. He seized her by her hair, and began belabouring her with the other which he had snatched out of her hand.

Fanny, supposing him to be in play, persevered in her efforts, but he continued to pull and pull at her hair, and to beat her about the shoulders so vehemently that he began to hurt her very much. She at first only laughed and cried out—

“Pray be quiet, Norman, I shall have the stocking on in a moment.”

But as her brother pulled more savagely, she could with difficulty help shrieking from the pain he inflicted.

“My dear Norman, do let go my hair,” she exclaimed, “you are really hurting me very much.”

“I know I am, and I intend to do so. I want to show you the way I treated my ayah when she dared to do anything I did not like, and I do not choose to let you meddle with my feet. When I want to put on my stockings I will put them on myself,” and Norman pulled and kicked and struggled so much that Fanny thought it would be wiser to give up attempting to draw on the stocking in the hopes that he would then release her hair from the grasp of his fingers. He was, however, in one of his evil moods, and, believing that he had gained a victory, instead of acting the part of a generous conqueror, he cruelly continued to tug at her hair till poor Fanny could no longer help shrieking out, “Let me go! let me go, Norman!”

She might, to be sure, have grasped his arms, and holding them have released herself by force, but the idea of doing so did not enter her gentle heart, for in the attempt she must have inflicted pain, and she was ready to suffer anything rather than do that.

Her shrieks brought Susan, who had come up to fasten her frock, into the room, and she, not at all approving of the way her favourite, Miss Fanny, was being treated, quickly grasped the young gentleman’s wrists, and made him open his fingers and release his sister’s hair.

“You naughty boy, how dare you behave in this way?” she exclaimed indignantly, “I will take you to your mamma this moment if you do not behave better, and do as you are told.”

“You had better not, or I will pull your hair, and make you wish you had let me alone,” exclaimed Norman, throwing himself back in the chair, and holding on to its arms to prevent Susan from lifting him up.

“Pray allow him to remain here, Susan, and I daresay he will let me finish dressing him. He did not hurt me so very much, but I was frightened, not expecting him to behave in that way, and so I could not help crying out for a moment,” said Fanny. “You will be good now, Norman, won’t you? and finish dressing, and be ready to go down to breakfast.”

The young gentleman made no answer, but sat as if rooted in the chair, looking defiantly at Susan and his sister.

“I see what we must do, young gentleman,” said Susan, who was a sensible woman, possessing herself of the stockings which had fallen on the ground, “we must put an end to this nonsense.”

Suddenly jerking up Master Norman, she seated herself in the chair, and pressing down his arms so that he could not reach her, she quickly drew on first one stocking and then the other.

“Now, Miss Fanny, please hand me the shoes,” and though Norman tried to kick she held his little legs and put them on.

“Now your hair must be put to rights, young gentleman. It is in a pretty mess with your struggles. Hand me the brush please, Miss Fanny!” and while she held down his arms, though he moved his head from side to side, she managed dexterously to arrange his rich curly locks.

“Has he washed his hands?” asked Susan.

Fanny shook her head.

“No, I have not, and I don’t intend to do so,” growled Norman.

“We shall soon see that,” cried Susan, dragging him to the basin; “there, take care you don’t upset it,” and forcing his hands into the water, she covered them well with soap.

Norman was so astonished at the whole proceeding, that he forgot to struggle, and only looked very red and angry. Susan made him rub his hands together till all the soap was washed off, and then dried them briskly with the towel.

“There, we have finished the business for you, young gentleman,” she said, as she released the boy, of whom she had kept a firm hold all the time.

“Now, we will put on your jacket and handkerchief, and you will be ready to go downstairs, but before you go just let me advise you not again to beat your sister in the way you did just now, or I will not let you off so easily.”

“Oh, pray do not be angry with him, Susan,” said Fanny, “he will I hope let me help him to dress to-morrow, and behave like a good boy.”

“No, I won’t,” growled Norman, “as soon as I see my papa I will tell him how that horrid woman has treated me, and he will soon send her about her business.”

Susan wisely did not reply to the last observation, but quietly made the young gentleman put on his jacket, and then fastened his collar, and tied his handkerchief round his neck.

“There, you will do now,” she said, surveying him with an expression in which pity was mingled with admiration, for he was indeed a handsome child, and she thought how grievous it would be that he should be spoilt by being allowed to have his own way. She then, lifting him up, suddenly placed him again in the chair and said, “Sit quiet, young gentleman, and try and get cool and nice to go down, and see your grandmamma. We are not accustomed to have angry faces in this house, and what is more we won’t have them.”

“Now come, Miss Fanny, I will help you to finish dressing.”

Saying this she signed to Fanny to go out of the room, and, closing the door, locked the young gentleman in.

As soon as she had put on Fanny’s frock and shoes, and arranged her hair, she went back to release Norman, whom she found still seated in the chair, in sullen dignity, with the angry frown yet on his countenance.

Susan said nothing, but taking his hand led him down after Fanny, to the door of the breakfast-room. He went in willingly enough, for he was very hungry and wanted his breakfast, but the angry frown on his brow had not vanished.

“Good morning, my dear,” said his grandmamma, who was already there, and had just kissed Fanny, who sprang forward to meet her.

Norman did not answer, but stood near the door, pouting his lips, while he kept his fists doubled by his side.

“What is the matter with him, my dear Fanny?” asked Mrs Leslie.

His sister did not like to tell their grandmamma of his behaviour, so instead of replying, she ran to him and tried to lead him forward.

“I want my breakfast,” muttered Norman.

“You will have it directly your mamma comes down, and prayers are over,” said Mrs Leslie quietly. “Come my dear, and give me a kiss, as your sister does every morning, you know that you are my grandchild as well as she is, and that I wish to love you as I do her.”

“I don’t care about that, I want my breakfast,” exclaimed Norman, breaking away from Fanny, and going towards the table, to help himself to some rolls he saw on it.

Fanny greatly ashamed at his behaviour, again endeavoured to lead him up to his grandmamma, but he, tearing his hands from hers, kicked out at her, and ran back to the table.

Just then Mrs Vallery entered the room and affectionately embracing her mother, drew her attention for a moment away from her grandchild. Norman took the opportunity of seizing one of the rolls, which he began stuffing into his mouth. His mother, though she saw him, and felt somewhat ashamed of his behaviour made no remark, for she knew what the consequences would be should she interfere.

“I am so much obliged to you, Fanny,” she said, “for dressing your brother. I hope he behaved well.”

Fanny would not tell an untruth, but she did not wish to complain of Norman, so she hung down her head, as if she herself had done something wrong.

Mrs Leslie suspected that Norman had not behaved well, but she remained silent on the subject as Mrs Vallery did not repeat the question.

Fanny, having made the tea, rang the bell and the servants, as usual, came in to prayers. Norman not being interfered with, kept munching away at the hot roll, and did not relinquish it when his mamma took him up, and placed him on a chair by her side. All the time Mrs Leslie was reading the sound of his biting the crisp crust was heard, while he sat casting a look of defiance at Susan, whose eye he saw was resting on him.

When they were seated at the table, Mrs Vallery apologised to his grandmamma for his conduct, observing that he was very hungry, as he was accustomed to have his breakfast as soon as he was up.

“We must let Susan give it him, then, another morning,” observed Mrs Leslie; “she will, I am sure, be very glad to attend to him in her room.”

“I won’t eat anything that woman gives me,” growled Norman, looking up from the roll and pat of fresh butter which his mamma had given him; “she is a nasty old thing; and if she tries to put on my stockings and wash my hands again, I will beat her as I did my ayah, and will soon show her who is master.”

“I thought you dressed your brother this morning, Fanny,” observed Mrs Vallery.

“So I did, mamma, but Susan came in to help me, though I hope to-morrow Norman will let me dress him entirely,” answered Fanny, determined if possible not to speak of her brother’s misconduct, and hoping by loving-kindness to overcome his evil temper.

Mrs Leslie wondered how a child of her gentle daughter’s could behave as Norman was doing.

“You will arrange about his breakfast as you think best, Mary,” she said; “but I hope that if Susan is kind enough to attend to him, he will be grateful to her. She is a faithful and excellent servant, and, of course, will expect to be obeyed and treated with respect by a little boy.”

A peculiar shake of the head which Norman gave, showed that he had no intention of following his grandmamma’s wishes.

Captain Vallery coming in, no further remark on the subject was made.

Having saluted his mother-in-law and daughter, and given Norman an affectionate pat on the head, he sat down to breakfast. Fanny having given him a cup of tea, and helped him to an egg and toast, and offered him other things on the table, he began to talk in his usual animated way, so that Norman, who wanted to make a complaint against Susan in his presence, was unable to get in a word. Fanny, who, guessing his intentions, was on the watch, whenever she saw that he was about to speak offered him a little more bread, or honey, or milk, anxiously endeavouring to prevent him saying anything which she considered would bring disgrace upon himself, by making his misconduct known. Happily for her affectionate design, Captain Vallery had to go up to London, and as soon as breakfast was over, kissing her and Norman, without listening to the mutterings of the latter, he hurried off to catch the train.

Chapter Two.

In Pursuit of Knowledge.

A lady came every morning to teach Fanny, but Mrs Leslie had begged that she might have a holiday in consequence of her papa’s and mamma’s arrival, and that she might have more time to play with her little brother.

Fanny had been anxiously considering how she could best amuse him.

“What should you like to do, Norman?” she asked, putting her arm affectionately round his neck. “You see I am a girl, and perhaps I may like many things that you will not care about. Let me consider. We can arrange my doll’s house, or we can play at paying visits; and I have two battledores and a shuttlecock, which I will teach you how to use; and then you must come out and help me to feed my chickens. I have also a garden of my own, and I am sure granny will let you have a piece of ground near it, or else you shall have part of mine, and you can learn how to keep it neat and pretty. And whenever you like you can have a game at romps with Trusty. You must make friends with him to-day; and if you call him by his name and give him a piece of meat, which I will get from the cook for you, and pat his head, he will soon learn to know you. But you must not frighten him with your whip, or he will run away from you. He used to be beaten when he was naughty, but then he was a little puppy, and did not know better; but now he never does anything wrong, and if he was ever so hungry, and was told to guard the things in the larder, or on the dining-room table, from the cat, he would not touch the nicest dish himself, and would take care that neither the cat nor any other dog came near them.”

“I do not care about any of the things you speak of,” answered Norman. “I want my whip, and I think Susan has hid it for fear I should beat her, and I intend to do so if she dares to treat me like a baby. I will beat Trusty too, if he barks at me—you’ll see if I don’t—and he will soon find out who is master. I am a brave boy, papa says so, and I want to be a man as soon as I can.”

“But brave and good boys do not beat either women or dogs, and I hope you wish to be good as well as brave,” said Fanny gently.

“So I am, when I have my own way,” exclaimed Norman, “and my own way I intend to have that I can tell you. Now, Fanny, go and find my whip, or make Susan give it to you if she has got it, and if she will not, tell her that my papa will make her when he comes home.”

Fanny, wishing to please her brother, and not believing that he would really make a bad use of his whip, hunted about for it, but in vain. She then went and asked Susan if she had got it.

Susan replied that she knew nothing about the whip, and had last seen it by the side of the young gentleman when he had fallen asleep in the arm-chair.

On hearing this, Norman marched into the drawing-room, expecting to find his whip in the place where he was supposed to have left it, but it was not there. He searched about in all directions, as Fanny had done in vain. He saw his grandmamma following him with her eyes, but he could not bring himself to ask her if she knew where his whip was, and she did not speak to him. At last, losing patience, he ran out of the room, and joined Fanny in the garden.

“Somebody has my whip, and I will find out who it is,” he muttered angrily, “I am not going to have my things taken away. But I say, Fanny, cannot you come out with me and buy another, I must have one just like the last, and I will try it on Trusty’s back if he comes barking at me again.”

“I cannot possibly take you out without granny’s or mamma’s leave, and you must not think of buying another whip to beat Trusty, I had just been thinking of asking cook to give you some small pieces of meat, and I will go at once and get them, then you must call Trusty, and when he comes to you, you must give him a piece at a time and pat his head and he will wag his tail, and you will be friends with him in a few minutes.”

“I would rather not have him come near me unless I have my whip to beat him if he tries to bite me,” said Norman.

“Oh, he will not bite you,” answered Fanny, and she ran to the kitchen where she got some bits of meat from the cook and brought them to her brother.

She soon found Trusty who was lying down on the rug in the dining-room, and followed her out into the garden.

“Call Trusty, Trusty, and show him a piece of meat,” she cried to her brother.

Norman with some hesitation in his tone called to the dog as Fanny bade him, and Trusty ran up wagging his tail. Instead of holding the meat and letting Trusty take it, which he would have done gently, Norman nervously threw the meat towards him, Trusty caught it, and putting up his nose and wagging his tail drew nearer; Norman instead of giving a piece at a time as Fanny had told him to do, fancying that the dog was going to snatch it from him, threw the whole handful on the ground and retreated several paces. Trusty began quickly to gobble up the meat.

“Oh, you should have given him bit by bit,” said Fanny.

As soon as Trusty had finished he ran forward expecting to get some more, when Norman fancying that the dog was going to bite him, took to his heels and ran off screaming, while Trusty bounded playfully after him thinking that he was running, as Fanny often did, to amuse him.

“Stop the horrid dog! he is going to kill me, stop him, stop him!” screamed Norman as he ran towards the house.

In vain Fanny called to Trusty and ran to catch him, he kept leaping up, however, hoping to get some more meat from the little boy who had, as he fancied, treated him so generously.

The cries of Norman brought out his mamma.

“The naughty dog is going to bite me, and Fanny is encouraging him. Save me, mamma, save me!” he exclaimed, as he threw himself into Mrs Vallery’s arms.

“Fanny, what is the matter,” she asked, “it is very naughty of you to let the dog frighten your little brother.”

Sweet gentle Fanny feeling how innocent she was of any such intention burst into tears.

“Indeed, dear mamma, I only tried to get Norman to play with Trusty and to make friends with him, I did not for a moment think he would be frightened,” and she ran forward and tried to kiss her brother in order to soothe him, but he now believed himself safe from the dog, who sagaciously perceiving that something was wrong had stopped jumping, and lay quietly on the ground, and as she approached he received her with a box on the ears.

“Take that for setting the dog at me,” he exclaimed maliciously.

Fanny stood hanging down her head as if she had been guilty, but really feeling ashamed of her brother’s behaviour.

“That was very naughty of you, Norman,” said Mrs Vallery, holding back the young tyrant, who was endeavouring again to strike his sister.

She then carried him into the drawing-room; Fanny followed her without a thought of vindicating herself, but wished to try and calm her young brother and to assure him that Trusty was only in play.

His mamma sat down with him on her knee. Mrs Leslie inquired whether he had hurt himself.

“He has been frightened by the dog, and says that Fanny set the animal at him,” answered Mrs Vallery.

“That is impossible,” observed Mrs Leslie, “Fanny could not have done anything of the sort.”

“She is a cruel thing, and wants the dog to bite me,” growled out Norman in a whining tone, still half crying.

“I will answer for it that Fanny is much more likely to have tried to prevent the dog from frightening you, for I am sure that he would not bite you. Come here, Fanny, I know that you will speak the truth.”

Fanny felt grateful to her grandmamma for her remark, and explained exactly what had occurred.

Mrs Vallery was convinced that she was innocent, and Norman was at last persuaded to return with her into the garden. Fanny talked to him gently, and tried to make him forget his fright.

“Come to the tool-house where I keep my spade and hoe and rake. There is a little spade which I used to use, it will just suit you, and we will go and arrange the garden you are to have,” she said as they went along.

“That is an old thing you have done with,” growled Norman scornfully, as she gave him the little spade, “I must have a new one of my own.”

“I hope papa will give you one,” she answered quietly, “but in the meantime will you not use this?”

Norman took it, eyeing it disdainfully, but Fanny, making no remark, led the way to the plot of ground the gardener had laid out for them. One part of it was full of summer flowers, the other half she had left uncultivated that Norman might have the pleasure of digging it up and putting in seeds and plants.

“You have taken good care to make your own garden look pretty,” he observed, as he eyed her portion of the plot. “What am I to do with that bare place?”

Fanny told him what her object had been, and offered to help him. She had got several pots with nice plants, which there was still time to put in, and a number of seeds of autumn flowers. These she promised to give to him as soon as the ground was fit for their reception. She began digging away in her usual energetic manner, and he for a time tried to imitate her, but he soon grew tired.

“There, you can dig away by yourself,” he said, “just as the natives do in India in the plantations, and I will look on like an owner, and watch that you do your work properly,” and he leant back with his arms folded, as he thought, in a very dignified way.

Fanny dug on for some time. At last she stopped and said, laughing—

“Now it is your turn to work, and mine to watch you.”

“I do not want to dig,” he answered, “I am going to be an officer like papa, and have others to obey me.”

Just then the gardener came by, and seeing Fanny digging away and making herself very hot, promised her that in the evening he would put the ground to rights. As she found that Norman was not disposed to garden, she invited him to have a game of battledore and shuttlecock on the lawn.

They had played for half-an-hour, and he seemed to be more amused than he had been with anything else. While they were in the garden Mrs Vallery had been unpacking her trunks, and wishing to show Fanny a dress she had brought from Paris for her, called her in. Norman said he would remain out and play by himself.

Some time was occupied in admiring the beautiful frock and in trying on some boots and other things. How grateful did she feel to her mamma as she kissed her again and again, and thanked her for bringing her so many pretty things. Though she would have liked to have stopped and admired them again and again, she did not forget Norman.

“I am afraid he will be growing dull by himself, mamma,” she said, “I will go out and try to amuse him. I see that he has gone away from the lawn and has left the battledore on the grass.”

Fanny, putting on her bonnet, went out to look for Norman. To her surprise, after searching about for some time, she saw him digging, as she thought, on his plot of ground.

“Oh, I am so glad that he is trying to amuse himself in that way,” she said to herself, “he will now learn to like gardening, I hope.”

On reaching the spot, however, she stood aghast, for Norman, instead of working in his own part of the ground, was digging away in hers, and had already uprooted nearly all her beautiful flowers.

“I am going to put them into my ground,” he said, when he caught sight of her, “I do not see why you should have them all to yourself.”

“But, my dear Norman, they will not bear transplanting,” she answered, almost bursting into tears, as she surveyed the havoc he had committed, for many of her flowers were not only dug up, but broken and trampled on, and it was evident that he intended rather to destroy than remove them.

“Oh, do stop, Norman!” she cried out, “the gardener promised, you know, to put some flowers into your garden, and he knows how to do it properly.”

“He may do as he likes,” said Norman, throwing down his spade; “I have taught you a lesson, Miss Selfish, your garden is not much better than mine now.”

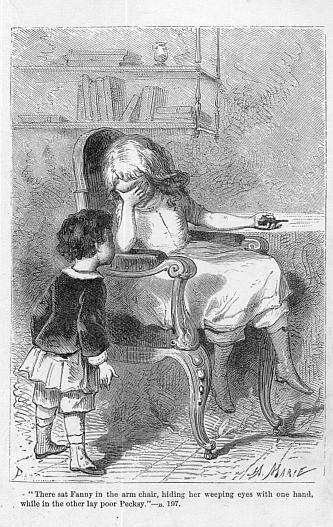

Fanny could no longer restrain her tears.

“O Norman!” she exclaimed, “it was not from selfishness I did not plant your garden, but I thought you would like to do it yourself, and that you would find pleasure in seeing flowers spring up which you had put in. Indeed, indeed, Norman, you accuse me wrongfully.”

“Well, at all events, we are even now,” growled out the boy, walking up and down, and it is to be hoped feeling somewhat ashamed of himself, as he surveyed the mischief he had done.

“Granny and mamma will be so angry with him if they see it,” thought Fanny, “I must try to put it to rights as far as I can,” and while Norman stood by with an angry frown on his brow, she began to replace some of the least injured plants. While she was thus employed, Susan came to tell her and her brother that it was time to get ready for dinner, for Fanny in her agitation had not even heard the gong sound.

“Why, Miss Fanny, what has happened to your garden?” exclaimed Susan.

Fanny never told an untruth, but she was very anxious to shield her brother, for she knew how angry Susan would be with him if she discovered what he had done.

“Pray do not ask me, Susan,” she answered, “John promised to put Norman’s garden to rights this evening, and I daresay he will do mine at the same time, until after that we had better not look at it.”

Susan guessed pretty correctly what had happened, but as Fanny had begged her not to ask questions, she refrained for her sake from doing so.

Fanny was going up to Norman to lead him towards the house, but he hung back, so Susan took him by the arm.

“Come along, young gentleman,” she said in the stern voice she knew how to assume, “you will require to wash your hands well after your gardening,” and she pointed back at the ground he had upturned. “Are you not ashamed of yourself?” she whispered. Fanny had run on a little way lest Susan should again ask questions. “If you are not ashamed you ought to be,” continued Susan, “your sweet sister is an angel, and I should like you just to ask yourself what you are.”

Norman though he threatened Susan behind her back stood in considerable awe of her in her presence, he therefore did not venture to reply, but as he hung somewhat behind her as she led him on, he made faces at her, which he knew she could not see.

Having washed his hands and brushed his hair she conducted him to the dining-room.

“Many a worse boy deserves his dinner more than you do,” she whispered, stopping before she took him in. “Eat yours with what appetite you can, but let me advise you to try and be sorry for the ungrateful way you have treated your sister, who has been so kind to you since you came into the house.”

Norman snatched his hand away from her, and with a glum countenance entered the dining-room. Walking up to the table he took his seat eyeing Fanny, who he suspected, judging by himself, had been telling their grandmamma and mamma what he had done. She, however, had not said a word about the matter. They were merely looking at him, wondering what made his countenance so sullen.

“I hope you have had a happy morning, Norman,” said his grandmamma, as she offered him some minced beef.

He made no reply.

“My dear, pray answer your grandmamma,” said Mrs Vallery, for she had been directed never to order Norman to do anything.

Still he did not speak.

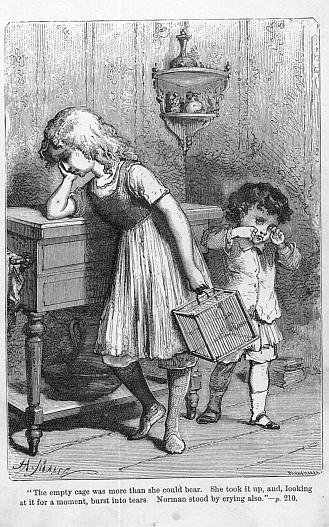

“My dear child do let me entreat you to make use of your tongue, your grandmamma spoke to you and asked if you had had a happy morning.”

“I never am happy, and am not likely to be with no one to try and amuse me,” growled out Norman.

“I am sure that your sister wishes to amuse you,” observed Mrs Leslie, “and I shall be very glad to read to you, or to tell you stories such as I used to tell Fanny, when she was of your age, if you will come and sit by me and listen.”

“She is only a girl, and you are an old woman,” muttered Norman shovelling the mince meat into his mouth. “I want boys to play with me.”

“You will find plenty of boys to play with when you go to school, where I hope your papa will soon send you,” observed Mrs Leslie, “but you will find that they do not treat you in the gentle way your sister does, and perhaps you will often wish that you had her again as a playmate.”

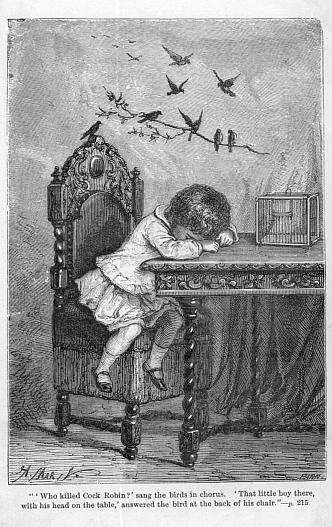

“We must have another game of battledore and shuttlecock on the lawn after dinner,” said Fanny, “you seem to like that, and on one side it will be pleasant and shady.”

Norman finding that Fanny had not complained of the way he had treated her garden, became more amiable and agreed to her proposal.

Before going out, however, she persuaded him to sit quiet and listen to a story, which she told him out of one of her picture-books.

The children were playing on the lawn, when Captain Vallery appeared followed by a man carrying a large parcel. Norman went on throwing up the shuttlecock, but Fanny ran to her papa to welcome him with a kiss.

“I have got something for you both, will you like to come in and see the parcel opened,” he said taking it from the man and going into the house.

Hearing his papa’s remark Norman followed him and Fanny, eager to learn what the parcel contained. Captain Vallery had placed it on a chair. While he was speaking to his wife and Mrs Leslie, Norman ran up to it, and although he had not even spoken to his papa, began pulling away at the string.

“Ah, he is a zealous little fellow, he wishes to save me trouble,” observed Captain Vallery, and Fanny hoped that such was the motive which prompted Norman, though she wished he had shown greater pleasure at seeing their papa come back.

Mrs Vallery at her husband’s request now opened the parcel, which Norman notwithstanding his efforts had been unable to do. Among other articles which he had brought for her and Mrs Leslie, she drew out a long parcel carefully done up in silver paper.

“This I think must be for Fanny,” she said.

Fanny, her countenance beaming with pleasure, carefully unwrapped the parcel, and exhibited a beautiful doll with a wax head and shoulders and wax hands looking exactly, she thought, as if they were real flesh.

“Oh, thank you, papa, thank you,” she exclaimed running up and kissing him. “Look granny! look mamma! see what a lovely little girl she is, with such fair soft hair and such blue bright eyes, she must surely be able to see out of them.”

Mrs Leslie and her mamma admired the doll, which was indeed a very handsome one, and very superior to poor Nancy.

“There, Norman, you will not be ashamed to walk out with her, I am sure,” she said. “But I hope Nancy will not think that she will make me forget her, for I should not like to hurt her feelings. What name shall we give her? for she would not like to be called ‘The New Doll,’ shall it be Emma or Julia or Lucy? I think Lucy is a very pretty name—shall she be called Lucy, granny? Norman do you like that name? it sounds so soft and so nice for a young lady doll as she is.”

Norman had been eyeing the doll with no pleasant feelings; he did not like that his sister should receive a present when he thought that there was none for him.

“You may call her Lucy, or whatever you fancy,” he answered gruffly, “boys like me do not care for dolls.”

“He is a fine, manly, little fellow,” observed Captain Vallery. “I have not forgotten you, though, Norman. Perhaps mamma will find something more to your taste in that large, round parcel,” and Mrs Vallery drew out the package at which her husband pointed.

“There, Norman, that is the sort of thing a boy likes,” said the Captain, handing it to him.

Norman snatched at it eagerly, and, with the assistance of his papa, tore off the paper, and found within an enormous football covered with leather, which he could just manage to grasp with his arms.

“There, you will be able to play with that famously on the lawn,” said Captain Vallery, “and I must come out and join you. I used to be very fond of football when I was at school, and we must have some fine games together.”

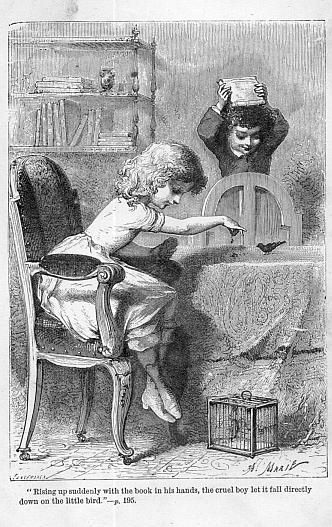

Norman, instead of thanking his papa, hugged the football and made towards the door, eager to go out on the lawn and kick it about. At the same time, he looked with a jealous eye at Fanny’s beautiful doll, which she was fondly caressing. Though he had declared that he did not care for dolls, he could not help thinking it prettier than his own great, brown ball, and, as he had never been taught to restrain any of the evil feelings which rose in his heart, he at once began to be jealous of his sister, because the present she had received was of more value than his. Still, he thought he should like to have a game with his ball, which, his papa told him, he was to kick from one end of the lawn to the other. Getting his hat, therefore, he told Fanny she must leave her doll, and come and play with him.

Fanny, ever anxious to please her brother, though longing to take Miss Lucy upstairs and introduce her to Nancy and to her doll’s house, at once consented to go out with him into the garden. Placing her doll, therefore, carefully in her own little chair, and telling her she must sit very patiently and be a good girl till she came back, she put on her hat, which hung up in the hall, and ran out into the garden.

Norman had already put the ball on the grass, and had begun to kick at it. He kicked and kicked away utterly regardless of his sister, and when she attempted to join him, he told her to wait till he was tired.

“But papa said you were to kick it from one side, and I was to kick it from the other,” she observed, “so we ought both to play at the same time.”

Norman at last allowed her to kick the ball, and was angry because she sent it away from him, and he had to run after it before he could get another kick. Still, Fanny did not remonstrate, and tried to send the ball so that Norman could easily reach it.

At last Captain Vallery came out.

“I am glad to see you play so nicely together,” he said; “pray go on.”

“Oh do, papa, take my place,” exclaimed Fanny, “it will be much better fun for Norman, and you will show him how to play.”

Captain Vallery accordingly kicked the ball, and sent it flying high up into the air. Norman shouted with delight.

“That’s much better than Fanny can do,” he exclaimed, as his papa sent the ball up several times.

“What makes it fly up like that?”

“My feet, in the first place; but as it is filled with wind, it is very light, and rises easily,” answered the Captain. “You, in time, will be able to make it fly as high.”

“I should like to see the wind in it,” said Norman; and his papa laughed at his remark, which he thought very witty.

They continued playing for some time; Captain Vallery, proud of having a son to instruct, showing Norman how to kick the ball, and explaining the way in which real football is played by big boys.

“I wish I was a big boy, and I soon shall be, I hope, for then I shall have some one else besides a stupid girl to play with,” exclaimed Norman. “I would rather have her than you, though, because you kick the ball about more than I like, and I want to kick it all by myself.”

“You are an independent little fellow,” observed his father approvingly, instead of rebuking him for his rude remark.

Captain Vallery stood by, allowing Norman to kick the ball backwards and forwards, which he did for some time, declaring on each occasion that if it reached either one side of the shrubbery or the other he had won the game—not a very difficult matter, considering that he had no one to oppose him.

At length, the gong sounding, Captain Vallery went in to dress for dinner, and Norman was left to play by himself, for, Fanny finding she was not wanted, had entered the house, and, after exhibiting her doll to Susan, had gone to her room to introduce Miss Lucy to Nancy and to her future abode.

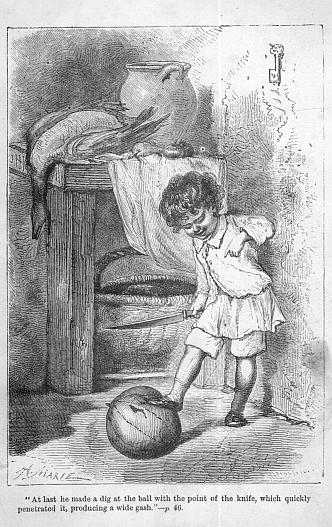

Norman soon grew weary of being by himself, and with his big ball in his arms, wandered into the house. Making his way into the drawing-room, he there found among a number of Indian curiosities which had just been unpacked, and which his papa intended to hang up against the wall, a long knife. Though Norman was very forward in some things, and could talk better than many boys older than he was, yet he was very ignorant in others, but of that, like many more ignorant people, he was not aware. “I should like to see the wind papa told me was inside this big ball,” he said to himself; “perhaps there is something else besides wind, it feels pretty soft—I daresay I could easily cut it open with this knife and see.” He took the knife and examined it, “I must not do it here though, or they may be coming downstairs and stop me,” so tucking the knife under one arm, and holding the big ball in the other, he went along the passage and out at the garden door. He at first proposed  going to the further end of the garden, where he need have no fear of being interrupted, then he recollected his performance of the morning, and thought that the gardener might be there, and would scold him for digging up Fanny’s plants, so instead of going there, he made his way along the side of the house, till he reached another door, which led to the larder.

going to the further end of the garden, where he need have no fear of being interrupted, then he recollected his performance of the morning, and thought that the gardener might be there, and would scold him for digging up Fanny’s plants, so instead of going there, he made his way along the side of the house, till he reached another door, which led to the larder.

“The cook won’t be coming in here at this hour, as she is serving up the dinner, so I shall have the place all to myself!” he observed, thinking how clever he was.

He accordingly went in and closed the door.

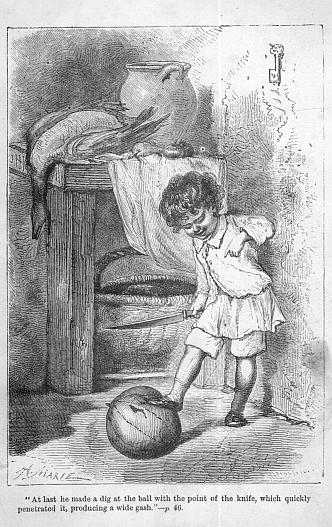

“Now I shall soon find out what is inside my ball,” he said chuckling and placing it on the ground. Putting one foot on it, to hold it steady, he began cutting away with the huge knife. The part of the weapon he used was not very sharp, and as the leather yielded, he at first made no impression; at last he made a dig at the ball with the point of the knife, which quickly penetrated it, producing a wide gash. Out rushed the wind faster and faster, as he pressed down his foot, till the coating of leather and the thin bladder inside had become perfectly flat. He took it up wondering at the result, and shook it and told it to get fat again, but all to no purpose. He felt very much inclined to cry, when somehow or other he discovered, that he had done a very foolish thing, but he was not accustomed to blame himself.

“Papa ought to have brought me a different sort of ball, which would not grow thin just because I happen to stick a knife into it,” he muttered to himself.

Again he threw down what had once been a ball, and stamped on it, and abused it for not doing as he told it. At last he began to think that the knife, which he supposed was his grandmamma’s, might be missed and that she would scold him for carrying it away. Taking up the leather therefore, and finding that no one was near, he returned. On his way seeing a thick bush, he threw the case into it—for he was somewhat ashamed of letting his father know the folly of which he had been guilty.

As no one had yet come down, he replaced the knife among the articles from which he had taken it, and ran up to his room. When he came back he found Fanny in the drawing-room reading, she told him that their granny and papa and mamma had gone in to dinner.

“Cannot you do something to amuse me?” he asked.

“Willingly,” she answered, putting aside her own book, and she read some stories to him out of one of the picture-books.

Susan came shortly to call the children to their tea, and they then went down to dessert in the dining-room.

“Well, my boy, are you inclined to have another game at football before you go to bed?” asked Captain Vallery.

“No,” answered Norman, not liking the question, “I do not want to play any more to-day.”

“I thought you seemed so pleased with your football, that you would never get tired of it,” observed Mrs Vallery.

Norman made no answer.

The ladies rose from the table, and Captain Vallery soon joined them in the drawing-room, they then strolled out on to the lawn to enjoy the cool air of that lovely summer evening.

“Go and get your football, Norman,” said Captain Vallery, “though you do not wish to play, I shall enjoy kicking it about to remind me of my schoolboy days.”

Norman did not move.

“Go and get it, my dear, as your papa tells you,” said Mrs Leslie, vexed at her grandson’s disobedience.

“I will go and get it—where did you leave it, Norman,” said Fanny.

“I do not know,” he answered.

“I daresay I shall find it,” said Fanny, supposing that her brother had left it in his room, or else in the hall.

She soon came back saying that she had hunted everywhere, but could not find it.

“I suppose the somebody who stole my whip, has taken that,” growled Norman.

“My dear, no one in this house would I am sure steal anything,” said Mrs Leslie, “but a friend, who considered that you would make a bad use of your whip, has undoubtedly put it out of your way. Do not let me bear you make that remark again.”

“There are thieves everywhere,” muttered Norman.

At that moment, Trusty was seen coming along one of the walks, dragging something brown, and tossing it playfully about. On he came till he reached the lawn.

“Why, Norman, I believe the dog has got your football, though he has managed to let the wind out of it,” exclaimed Captain Vallery.

“Oh, the thief, beat him, papa!” cried Norman.

“Oh, pray not!” exclaimed Fanny, “I am sure Trusty did not intend to hurt Norman’s ball,” cried Fanny, running forward and catching Trusty. “Give it up, sir, give it up, you do not know the mischief you have done,” she added.

“Oh, but he must have stolen it, and see he has made a great hole in it with his teeth!” exclaimed Norman.

Captain Vallery took up the football and examined it.

“The dog did not do this,” he said, pointing to the slit in the leather. “This was done by a sharp knife; we must not wrongfully accuse the dog, he must have found it in this condition; somebody else cut the hole.”

Norman grew very red; his papa looked at him.

“I suspect somebody wanted to see the wind which I told him was within it,” he observed.

Norman grew redder still.

“I thought so,” said Captain Vallery. “Did you cut the hole in your ball, Norman?” he asked sternly.

“I wanted to see the wind in it,” murmured Norman.

Now Captain Vallery, though he held some wrong ideas about education, was a highly honourable man, and as every honourable man must do, he hated a falsehood, or any approach to a falsehood. He considered that what some people call white lies are black notwithstanding, and he knew in his heart that God hates them.

“Why did you say, then, that the dog had torn your ball, when you knew that you yourself cut it?” he asked. “I have never before punished you, but I intend to do so. I will not have a son of mine become a liar.”

“My dear,” he said, turning to his wife, “take Norman in and put him to bed. I cannot look at him any more to-night.”

Mrs Vallery took Norman by the hand and led him into the house.

Mrs Leslie said nothing, but she was glad to find that her son-in-law considered it necessary to try and put a stop to one of the bad ways of his son. Perhaps he might in time find out that there were other bad ways of his which it would be as well to check.

Captain Vallery walked up and down on the lawn by himself for some time, considering how he should treat his son, and he began to reflect whether after all his system of allowing a boy to have his own way was likely to prove the best.

Chapter Three.

Can you forgive it?

Next morning, when Norman came down to breakfast, his papa, instead of playfully addressing him, turned away his head and took no notice of his presence. Norman ate his breakfast in silence. Fanny looked very sad, she felt that her brother deserved punishment, and that it might teach him the necessity of speaking the truth. Still she could not bear the thoughts of her young brother being beaten, and from what her papa had said she believed he intended to do so. Her grandmamma had quoted the proverb of Solomon, “He that spareth the rod hateth his son, but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes.”

“You are right, Mrs Leslie,” her papa had remarked, “I acknowledge the wisdom of the great king, and must follow his advice.”

After breakfast Fanny’s governess arrived, and Captain Vallery took his son up into his room. What happened there Norman did not divulge, but he looked very crestfallen during the rest of the morning. When he met Fanny afterwards he told her that he did not intend to tell any more lies.

“I hope you will not do so,” said Fanny, “remember that God hates them even more than papa or anybody else can do, and He knows when you tell an untruth, although no human being may find it out.”

After dinner Norman appeared to have recovered his spirits, and Fanny took him out to play battledore and shuttlecock.

They were beginning to get tired, when Mrs Leslie and their mamma came out.

“Come and walk with us, my dears,” said Mrs Leslie, “I want to show your mamma the pretty garden you have cultivated so nicely, Fanny.”

Fanny would thankfully have prevented them from seeing her garden, for she knew that the way Norman had treated it would be discovered. Still she could not think how to avoid going, and she could only hope that the gardener had put it to rights, as he had promised to do.

Mrs Leslie, wishing to gain her grandson’s confidence, called to him, and taking his hand, led him on talking to him kindly; Fanny and her mamma followed at a little distance.

Mrs Vallery interested Fanny by giving her accounts of India, but she was so anxious about her garden and the vexation her granny would feel at seeing it destroyed, that she could not listen as attentively as she otherwise would have done. She saw that Norman was walking on very unwillingly, and from time to time making an effort to escape, but his grandmamma had no intention of letting him go.

At length Mrs Leslie and Norman reached Fanny’s garden.

“Why, my dear, what changes you have made!” she exclaimed, “and I see you have dug up nearly half of it.”

Fanny ran forward. The gardener had begun to set it to rights, but had evidently been prevented from finishing the work. The two spades were stuck in the ground where Fanny and Norman had left them.

Fanny said nothing, she hoped that her brother would manfully confess what he had done, that she might then be better able to plead for him. Instead of doing so he snatched his hand away from that of his grandmamma and ran off along the walk. Fanny had then most reluctantly to confess that her brother had dug up her garden.

“Do not be angry with him, granny,” she said, “he is very very young, and he thought I had ill-treated him by not making his garden as nice as mine was. He did not understand that I fancied he would like to arrange it himself, but John has promised to put it in order, and I hope to-morrow that mine will be as nice as ever, and that Norman’s will be like it, so pray say no more to him about it.”

“I will do as you wish, Fanny,” answered Mrs Leslie, “but I cannot allow your brother, young as he is, to behave in the same way again.”

Mrs Vallery was greatly grieved at discovering what Norman had done, at the same time she was much pleased to hear the way Fanny pleaded for her young brother, and she could not resist stooping down and kissing her again and again while the tears came into her eyes.

“O mother! you have indeed made her all I can wish,” she said, turning to Mrs Leslie.

“Not I, my dear Mary, I did but what God tells us to do in His Word; I corrected her faults as I discovered them, and have ever sought guidance from Him. But His Holy Spirit has done the work which no human person could accomplish.”

Norman, conscience-stricken, had hidden himself in the shrubbery. The rest of the party supposing that he had run into the house, continued their walk, and after taking a few turns in the shady avenue they went in-doors.

Mrs Norton, Fanny’s governess, having just then arrived she set to work on her lessons, while her mamma and Mrs Leslie went to the drawing-room.

“I am afraid, mamma, that you must think Norman a very naughty boy,” said Mrs Vallery, “I have spoken to him very often about his conduct, and as yet I see no improvement.”

“I have hopes that he will at all events learn that he must not tell stories,” observed Mrs Leslie, “and if your husband takes the same means that he did this morning to teach him what is wrong he will by degrees learn what he must not do. It is far more difficult to teach a child what it ought to do, though I trust the good example set by our dear Fanny will have its due effect, while we must continue to pray without ceasing that the heart of your child may be changed.”

“I fear he has a very bad heart now,” sighed Mrs Vallery, “I am always in dread that he should do something wrong.”

“All children have bad seeds in their hearts, and it is our duty by constant and careful weeding to root them out, and to impress also on the child from its earliest days the necessity of endeavouring to do so likewise. The child is not excused as it gains strength and knowledge if it does not perform its own part in the work,” observed Mrs Leslie. “We justly believe our Fanny to be sweet and charming, but she is well aware of this, and is ever on the watch to overcome the evil she discovers within herself. Depend upon it, did she not do so she would not be the delightful creature we think her.”

“Could Fanny possibly have been otherwise than delightful?” said Mrs Vallery.

“Not only possibly, but very probably so, although we, blinded by our love might have overlooked the faults of which she would certainly have been guilty,” answered Mrs Leslie. “One of the chief lessons we should endeavour to impress on young people is the importance of keeping a strict watch over their mind and temper, of putting away every bad thought the instant it comes into the mind, and to suppress at once the rising of bad temper, envy, hatred, and all other evil feelings, while we teach them that Satan, like a roaring lion, is always going about seeking whom he may devour, although the aid of the Holy Spirit will never be sought in vain to drive him away.”

While this conversation was going on between his grandmamma and mamma in the drawing-room Norman remained in the shrubbery. He was afraid to come out, supposing that his mamma was looking for him, and that he would be punished for destroying his sister’s garden, as he had been in the morning for telling a falsehood. Growing weary he at length crept out, and hearing and seeing no one, thought he might venture into the open garden. He soon became tired of being by himself, and wished that Fanny would come out and play with him, then he felt angry with her because she did not, though he well knew that she was attending to her lessons.

At last as he wandered about his eyes fell on the covering of his football.

“That’s what my fine present has come to,” he muttered, “and she has got a beautiful doll all to herself; I do not see why she should be better off than I am. I wonder if anybody could make my ball round again.”

He took it up.

“Perhaps the cook or John can.”

He carried the leathern case in to the cook.

“Make your ball round again Master Norman!” she exclaimed, “it would be a hard job to do that, with the big slit which I see in it. You must get a fresh bladder of the proper size, and then perhaps we may be able to mend the leather case.”

“Can you get me a bladder?” asked Norman.

“A bladder costs money! You must ask your papa to get one for you,” answered the cook, who was not particularly willing to oblige him for the way he had treated his sister, and Susan had prevented him from gaining the goodwill of the servants.

“But I say you must get me a bladder,” exclaimed Norman, “what are you? you are only a servant. I will make you do what I want.”

“I tell you what young gentleman, I will pin a dish-cloth to your back, and send you out of the kitchen, if you speak to me in that way. I am busy now in preparing your grandmamma’s luncheon, and I cannot attend to you.”

Norman after walking about looked very angry for some minutes. Seeing, however, the cook take up a dirty cloth and draw a pin from her dress, he thought it wiser to walk off, and made his way back into the garden.

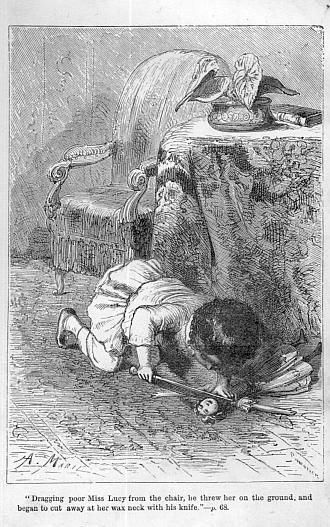

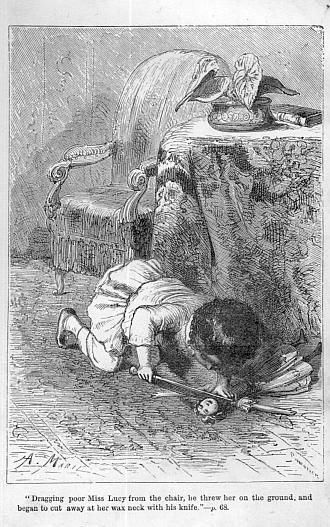

“I do not see why Fanny should have a beautiful doll and I only a stupid bit of leather,” he muttered to himself. “If I can get hold of that doll of hers, I know what I will do to it, and then she won’t be a bit better off than I am.”

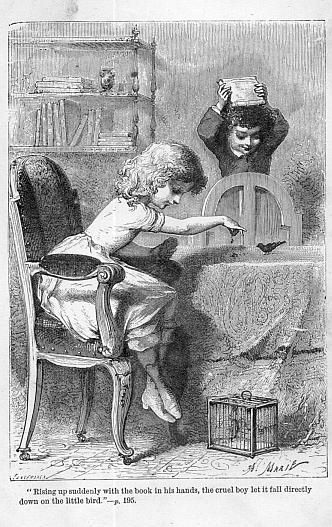

Instead of attempting to overcome the spirit of envy, which sprung up in his heart, he went on muttering to himself that he would soon spoil Miss Lucy’s beauty.

He had not improved in temper, when he was summoned in to dinner.

Neither Mrs Leslie nor his mamma said anything about Fanny’s garden, and he himself was not inclined to introduce the subject. His grandmamma did not speak to him, for she was anxious if possible to make him ashamed of his conduct. Discerning as she was, she was little aware of the obstinacy of his disposition, and that all he cared for, was to avoid punishment.

Fanny had talked to him and tried to amuse him after dinner; as it was still too hot to go out, she invited him to come into the drawing-room, and listen to a pretty story she would read to him out of a book.

After she had read a little time, her grandmamma invited her to sit by her side, that she might go on with some work that she was teaching her to do.

“Come with me, Norman,” said Fanny, jumping up immediately, “granny will let you sit near me on a footstool, and if you hold the book, I can tell you some of the stories by merely looking at the pictures.”

Norman, who liked having stories told to him, made no objection, and sat down quietly on a footstool near Fanny.

“I think Norman, you should now tell Fanny something about India,” said Mrs Leslie, after Fanny had told him several stories.

“It’s a finer country than this, and people do as they are told, that’s one thing I know about it,” observed Norman. “A very good thing too,” said Mrs Leslie, “I always like little boys and girls to do as they are told.”

“But big people do as they are told, our kitmutgars and chaprassey ran off as quick as lightning to do anything I told them, and if not I kicked them.”

“I hope that you will not do so to any one in England, my dear,” said Mrs Leslie.

“I am sorry to say that Norman did sometimes attempt to do as he tells you,” observed Mrs Vallery. “The people he speaks of were our servants. A kitmutgar is a man who waits at table, and a chaprassey is another servant, whose duty it is to run on messages, to attend on ladies when they go out, and to perform the general duties of a footman, though he does not wait at table. You must know, Fanny, in India each person has especial duties, and he considers it degrading to perform any others.

“A groom is called a syce, but he will not cut the grass for his own horse, and requires another man to do so. The head servant, who performs the duty of butler, and purchases all the food for the family, is called a rhansaman.

“A great deal of water is required in the hot weather for bathing and wetting the tatties, and one man is employed in bringing it up from the river to the bungalow in which we lived—he is called a chestie. A different man, however, called an aubdar, takes care that proper drinking water is supplied—we generally used rain water, which was collected in large sheets stretched out between four poles in the rainy season, and drained into earthen jars, where it keeps cool and sweet.

“None of those I have mentioned would clean the rooms, and, therefore, another man a mehter or sweeper was employed. Our clothes were washed by a man called a dhobie; he used to come with his donkey, and carry them off to the river, where he beat them with a flat stick on a wooden slab over and over again till they were clean, and then dried them in the sun.

“When any out-door work was to be done, we hired labourers of the lowest caste, who were called coolies. Then we had a tailor, who made all my clothes as well as Norman’s and his papa’s, and he is called a durize. We had six bearers, who were employed to carry our palanquin, when we went out, and they also had to keep the punkahs at work, besides having other things to do.”

“What a household,” exclaimed Mrs Leslie, “I am glad we have not so many servants to attend to in England. Where did they all live?”

“Some slept rolled up in their sheets on mats in the verandah in front of the bungalow, others in huts by themselves.”

“Had you no maid-servants?” asked Fanny.

“Only one, called an ayah, who acted as my lady’s maid, and took care of Norman, but had nothing else to do,” answered Mrs Vallery.

“Mamma, what are punkahs and tatties?” inquired Fanny, “I did not like to interrupt you when you spoke of them.”

“The punkah is something like an enormous fan suspended to the roof, and when a breeze is required, it is drawn backwards and forwards with ropes by the bearers. Sometimes in hot weather it is kept going day and night, indeed without it at times we should scarcely have been able to bear the heat, or go to sleep at night. The tatties are mats made of a sweet-smelling grass, which are hung up on the side from which the hot wind comes, and being kept constantly wet by the chesties, the air passing through them is cooled by the evaporation which takes place.”

“I suppose you must have lived in a very large house, as you had so many servants to attend on you,” observed Fanny.

“When we were at a station up the country, we resided in a bungalow, which was a cottage, with all the rooms on the ground floor, in the centre of an enclosure called a compound. It was covered with a sloping thickly-thatched roof, to keep out the rays of the sun. In the centre was a large hall which was our sitting-room, with doors opening all round it into the bedrooms, and outside them was a broad verandah. I spoke of doors, but I should rather have called them door-ways with curtains to them, thus the air set moving by the punkahs could circulate through the house, while the sun could not penetrate into the inner room, it was therefore kept tolerably cool.”

“I think we are better off in England, where even in the hottest weather we can keep cool without so much trouble being taken,” observed Fanny. “How I pity the poor men who are obliged to work at the punkahs.”

“They are accustomed to the heat, and it is their business,” observed Mrs Vallery; “they would not have thanked us had we dismissed them, and told them that for their sakes we were ready to bear the hot stifling atmosphere, or to refrain from going out in our palanquins.”

“What are palanquins, mamma?” asked Fanny.