Title: Birds, Illustrated by Color Photography, Vol. 1, No. 5

Author: Various

Release date: July 6, 2008 [eBook #25983]

Most recently updated: January 20, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Anne Storer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

Transcriber’s Note:

A couple of unusual spellings in the “ads”

have been left as printed.

W. E. Watt, President &c.,

Fisher Building,

277 Dearborn St., Chicago, Ill.

My dear Sir:

Please accept my thanks for a copy of the first publication of “Birds.” Please enter my name as a regular subscriber. It is one of the most beautiful and interesting publications yet attempted in this direction. It has other attractions in addition to its beauty, and it must win its way to popular favor.

Wishing the handsome little magazine abundant prosperity, I remain

Yours very respectfully,

NOW READY.

THE STORY of the BIRDS.

By JAMES NEWTON BASKETT.

Edited by Dr. W. T. Harris, U. S. Com’r of Education.

table of contents.

| chapter | ||

| I. | — | A Bird’s Forefathers. |

| II. | — | How did the Birds First Fly, Perhaps? |

| III. | — | A Bird’s Fore Leg. |

| IV. | — | Why did the Birds put on Soft Raiment? |

| V. | — | The Cut of a Bird’s Frock. |

| VI. | — | About a Bird’s Underwear. |

| VII. | — | A Bird’s Outer Wrap. |

| VIII. | — | A Bird’s New Suit. |

| IX. | — | “Putting on Paint and Frills” among the Birds. |

| X. | — | Color Calls among the Birds. |

| XI. | — | War and Weapons among the Birds. |

| XII. | — | Antics and Odor among the Birds. |

| XIII. | — | The Meaning of Music among Birds. |

| XIV. | — | Freaks of Bachelors and Benedicts in Feathers. |

| XV. | — | Step-Parents among Birds. |

| XVI. | — | Why did Birds begin to Incubate? |

| XVII. | — | Why do the Birds Build So. |

| XVIII. | — | Fastidious Nesting Habits of a few Birds. |

| XIX. | — | What Mean the Markings and Shapes of Bird’s Eggs? |

| XX. | — | Why Two Kinds of Nestlings? |

| XXI. | — | How Some Baby Birds are Fed. |

| XXII. | — | How Some Grown-Up Birds get a Living. |

| XXIII. | — | Tools and Tasks among the Birds. |

| XXIV. | — | How a Bird Goes to Bed. |

| XXV. | — | A Little Talk on Bird’s Toes. |

| XXVI. | — | The Way of a Bird in the Air. |

| XXVII. | — | How and Why do Birds Travel? |

| XXVIII. | — | What a Bird knows about Geography and Arithmetic. |

| XXIX. | — | Profit and Loss in the Birds. |

| XXX. | — | A Bird’s Modern Kinsfolk. |

| XXXI. | — | An Introduction to the Bird. |

| XXXII. | — | Acquaintance with the Bird. |

1 vol. 12mo. Cloth, 65 cents, postpaid.

D. APPLETON & CO., New York, Boston, Chicago.

Chicago Office, 243 Wabash Ave.

“With cheerful hop from perch to spray,

They sport along the meads;

In social bliss together stray,

Where love or fancy leads.

Through spring’s gay scenes each happy pair

Their fluttering joys pursue;

Its various charms and produce share,

Forever kind and true.”

CHICAGO, U. S. A.

Nature Study Publishing Company, Publishers

1896

It has become a universal custom to obtain and preserve the likenesses of one’s friends. Photographs are the most popular form of these likenesses, as they give the true exterior outlines and appearance, (except coloring) of the subjects. But how much more popular and useful does photography become, when it can be used as a means of securing plates from which to print photographs in a regular printing press, and, what is more astonishing and delightful, to produce the REAL COLORS of nature as shown in the subject, no matter how brilliant or varied.

We quote from the December number of the Ladies’ Home Journal: “An excellent suggestion was recently made by the Department of Agriculture at Washington that the public schools of the country shall have a new holiday, to be known as Bird Day. Three cities have already adopted the suggestion, and it is likely that others will quickly follow. Of course, Bird Day will differ from its successful predecessor, Arbor Day. We can plant trees but not birds. It is suggested that Bird Day take the form of bird exhibitions, of bird exercises, of bird studies—any form of entertainment, in fact, which will bring children closer to their little brethren of the air, and in more intelligent sympathy with their life and ways. There is a wonderful story in bird life, and but few of our children know it. Few of our elders do, for that matter. A whole day of a year can well and profitably be given over to the birds. Than such study, nothing can be more interesting. The cultivation of an intimate acquaintanceship with our feathered friends is a source of genuine pleasure. We are under greater obligations to the birds than we dream of. Without them the world would be more barren than we imagine. Consequently, we have some duties which we owe them. What these duties are only a few of us know or have ever taken the trouble to find out. Our children should not be allowed to grow to maturity without this knowledge. The more they know of the birds the better men and women they will be. We can hardly encourage such studies too much.”

Of all animated nature, birds are the most beautiful in coloring, most graceful in form and action, swiftest in motion and most perfect emblems of freedom.

They are withal, very intelligent and have many remarkable traits, so that their habits and characteristics make a delightful study for all lovers of nature. In view of the facts, we feel that we are doing a useful work for the young, and one that will be appreciated by progressive parents, in placing within the easy possession of children in the homes these beautiful photographs of birds.

The text is prepared with the view of giving the children as clear an idea as possible, of haunts, habits, characteristics and such other information as will lead them to love the birds and delight in their study and acquaintance.

NATURE STUDY PUBLISHING

Illustrated by COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY.

“There swims no goose so gray, but soon or late,

She takes some honest gander for a mate;”

There live no birds, however bright or plain,

But rear a brood to take their place again.

—C. C. M.

UITE the jolliest season of the year, with the birds, is when they begin to require a home, either as a shelter from the weather, a defence against their enemies, or a place to rear and protect their young. May is not the only month in which they build their nests, some of our favorites, indeed, waiting till June, and even July; but as it is the time of the year when a general awakening to life and activity is felt in all nature, and the early migrants have come back, not to re-visit, but to re-establish their temporarily deserted homes, we naturally fix upon the first real spring month as the one in which their little hearts are filled with titillations of joy and anticipation.

In May, when the trees have put on their fullest dress of green, and the little nests are hidden from all curious eyes, if we could look quite through the waving branches and rustling leaves, we should behold the little mothers sitting upon their tiny eggs in patient happiness, or feeding their young broods, not yet able to flutter away; while in the leafy month of June, when Nature is perfect in mature beauty, the young may everywhere be seen gracefully imitating the parent birds, whose sole purpose in life seems to be the fulfillment of the admonition to care well for one’s own.

There can hardly be a higher pleasure than to watch the nest-building of birds. See the Wren looking for a convenient cavity in ivy-covered walls, under eaves, or among the thickly growing branches of fir trees, the tiny creature singing with cheerful voice all day long. Observe the Woodpecker tunneling his nest in the limb of a lofty tree, his pickax-like beak finding no difficulty in making its way through the decayed wood, the sound of his pounding, however, accompanied by his shrill whistle, echoing through the grove.

But the nest of the Jay: Who can find it? Although a constant prowler about the nests of other birds, he is so wary and secretive that his little home is usually found only by accident. And the Swallow: “He is the bird of return,” Michelet prettily says of him. If you will only treat him kindly, says Ruskin, year after year, he comes back to the same niche, and to the same hearth, for his nest. To the same [Pg 150] niche! Think of this a little, as if you heard of it for the first time.

But nesting-time with the birds is one of sentiment as well as of

industry The amount of affectation in lovemaking they are capable of is

simply ludicrous. The British Sparrow which, like the poor, we have with

us always, is a much more interesting bird in this and other respects

than we commonly give him credit for. It is because we see him every

day, at the back door, under the eaves, in the street, in the parks,

that we are indifferent to him. Were he of brighter plumage, brilliant

as the Bobolink or the Oriole, he would be a welcome, though a

perpetual, guest, and we would not, perhaps, seek legislative action for

his extermination. If he did not drive away Bluebirds, whose

nesting-time and nesting-place are quite the same as his own, we might

not discourage his nesting proclivity, although we cannot help

recognizing his cheerful chirp with generous crumbs when the snow has

covered all the earth and left him desolate.

C. C. Marble.

extract from the report of the committee on dress, by its chairman, mrs. frank johnson.

Birds, Wings and Feathers Employed as Garniture.

From the school-room there should certainly emanate a sentiment which would discourage forever the slaughter of birds for ornament.

The use of birds and their plumage is as inartistic as it is cruel and barbarous.

The Halo.

“One London dealer in birds received, when the fashion was at its height, a single consignment of thirty-two thousand dead humming birds, and another received at one time, thirty thousand aquatic birds and three hundred thousand pairs of wings.”

Think what a price to pay,

Faces so bright and gay,

Just for a hat!

Flowers unvisited, mornings unsung,

Sea-ranges bare of the wings that o’erswung—

Bared just for that!

Think of the others, too,

Others and mothers, too,

Bright-Eyes in hat!

Hear you no mother-groan floating in air,

Hear you no little moan—birdling’s despair—

Somewhere for that?

Caught ’mid some mother-work,

Torn by a hunter Turk,

Just for your hat!

Plenty of mother-heart yet in the world:

All the more wings to tear, carefully twirled!

Women want that?

Oh, but the shame of it,

Oh, but the blame of it,

Price of a hat!

Just for a jauntiness brightening the street!

This is your halo—O faces so sweet—

Death, and for that!—W. C. Gannett.

screech owl.

screech owl.

IGHT WANDERER,” as this species of Owl has been appropriately called, appears to be peculiar to America. They are quite scarce in the south, but above the Falls of the Ohio they increase in number, and are numerous in Virginia, Maryland, and all the eastern districts. Its flight, like that of all the owl family, is smooth and noiseless. He may be sometimes seen above the topmost branches of the highest trees in pursuit of large beetles, and at other times he sails low and swiftly over the fields or through the woods, in search of small birds, field mice, moles, or wood rats, on which he chiefly subsists.

The Screech Owl’s nest is built in the bottom of a hollow trunk of a tree, from six to forty feet from the ground. A few grasses and feathers are put together and four or five eggs are laid, of nearly globular form and pure white color. This species is a native of the northern regions, arriving here about the beginning of cold weather and frequenting the uplands and mountain districts in preference to the lower parts of the country.

In the daytime the Screech Owl sits with his eyelids half closed, or slowly and alternately opening and shutting, as if suffering from the glare of day; but no sooner is the sun set than his whole appearance changes; he becomes lively and animated, his full and globular eyes shine like those of a cat, and he often lowers his head like a cock when preparing to fight, moving it from side to side, and also vertically, as if watching you sharply. In flying, it shifts from place to place “with the silence of a spirit,” the plumage of its wings being so extremely fine and soft as to occasion little or no vibration of the air.

The Owl swallows its food hastily, in large mouthfuls. When the retreat of a Screech Owl, generally a hollow tree or an evergreen in a retired situation, is discovered by the Blue Jay and some other birds, an alarm is instantly raised, and the feathered neighbors soon collect and by insults and noisy demonstration compel his owlship to seek a lodging elsewhere. It is surmised that this may account for the circumstance of sometimes finding them abroad during the day on fences and other exposed places.

Both red and gray young are often found in the same nest, while the parents may be both red or both gray, the male red and the female gray, or vice versa.

The vast numbers of mice, beetles, and vermin which they destroy render the owl a public benefactor, much as he has been spoken against for gratifying his appetite for small birds. It would be as reasonable to criticise men for indulging in the finer foods provided for us by the Creator. They have been everywhere hunted down without mercy or justice.

During the night the Screech Owl utters a very peculiar wailing cry, not unlike the whining of a puppy, intermingled with gutteral notes. The doleful sounds are in great contrast with the lively and excited air of the bird as he utters them. The hooting sound, so fruitful of “shudders” in childhood, haunts the memory of many an adult whose earlier years, like those of the writer, were passed amidst rural scenery.

I wouldn’t let them put my picture last in the book as they did my cousin’s picture in March “Birds.” I told them I would screech if they did.

You don’t see me as often as you do the Blue-bird, Robin, Thrush and most other birds, but it is because you don’t look for me. Like all other owls I keep quiet during the day, but when night comes on, then my day begins. I would just as soon do as the other birds—be busy during the day and sleep during the night—but really I can’t. The sun is too bright for my eyes and at night I can see very well. You must have your folks tell you why this is.

I like to make my nest in a hollow orchard tree, or in a thick evergreen. Sometimes I make it in a hay loft. Boys and girls who live in the country know what a hay loft is.

People who know me like to have me around, for I catch a good many mice, and rats that kill small chickens. All night long I fly about so quietly that you could not hear me. I search woods, fields, meadows, orchards, and even around houses and barns to get food for my baby owls and their mamma. Baby owls are queer children. They never get enough to eat, it seems. They are quiet all day, but just as soon as the sun sets and twilight gathers, you should see what a wide awake family a nest full of hungry little screech owls can be.

Did you ever hear your mamma say when she couldn’t get baby to sleep at night, that he is like a little owl? You know now what she means. I think I hear my little folks calling for me so I’ll be off. Good night to you, and good morning for me.

orchard oriole.

orchard oriole.

The Orchard Oriole is here.

Why has he come? To cheer, to cheer—C. C. M.

HE Orchard Oriole has a general range throughout the United States, spending the winter in Central America. It breeds only in the eastern and central parts of the United States. In Florida it is a summer resident, and is found in greatest abundance in the states bordering the Mississippi Valley. This Oriole appears on our southern border about the first of April, moving leisurely northward to its breeding grounds for a month or six weeks, according to the season, the males preceding the females several days.

Though a fine bird, and attractive in his manners and attire, he is not so interesting or brilliant as his cousin, the Baltimore Oriole. He is restless and impulsive, but of a pleasant disposition, on good terms with his neighbors, and somewhat shy and difficult to observe closely, as he conceals himself in the densest foliage while at rest, or flies quickly about from twig to twig in search of insects, which, during the summer months, are his exclusive diet.

The favorite haunts of this very agreeable songster, as his name implies, are orchards, and when the apple and pear trees are in bloom, and the trees begin to put out their leaves, his notes have an ecstatic character quite the reverse of the mournful lament of the Baltimore species. Some writers speak of his song as confused, but others say this attribute does not apply to his tones, the musician detecting anything but confusion in the rapidity and distinctness of his gushing notes. These may be too quick for the listener to follow, but there is harmony in them.

In the Central States hardly an orchard or a garden of any size can be found without these birds. They prefer to build their nests in apple trees. The nest is different, but quite as curiously made as that of the Baltimore. It is suspended from a small twig, often at the very extremity of the branches. The outer part of the nest is usually formed of long, tough grass, woven through with as much neatness and in as intricate a manner as if sewed with a needle. The nests are round, open at the top, about four inches broad and three deep.

It is admitted that few birds do more good and less harm than our Orchard Oriole, especially to the fruit grower. Most of his food consists of small beetles, plant lice, flies, hairless caterpillars, cabbage worms, grasshoppers, rose bugs, and larvæ of all kinds, while the few berries it may help itself to during the short time they last are many times paid for by the great number of insect pests destroyed, making it worthy the fullest protection.

The Orchard Oriole is very social, especially with the king bird. Most of his time is spent in trees. His flight is easy, swift, and graceful. The female lays from four to six eggs, one each day. She alone sits on the eggs, the male feeding her at intervals. Both parents are devoted to their young.

The fall migration begins in the latter part of July or the beginning of August, comparatively few remaining till September.

NE of the most widely distributed birds of North America is the Marsh Hawk, according to Wilson, breeding from the fur regions around Hudson’s Bay to Texas, and from Nova Scotia to Oregon and California. Excepting in the Southern portion of the United States, it is abundant everywhere. It makes its appearance in the fur countries about the opening of the rivers, and leaves about the beginning of November. Small birds, mice, fish, worms, and even snakes, constitute its food, without much discrimination. It is very expert in catching small green lizards, animals that can easily evade the quickest vision.

It is very slow on the wing, flies very low, and in a manner different from all others of the hawk family. Flying near the surface of the water, just above the weeds and canes, the Marsh Hawk rounds its untiring circles hour after hour, darting after small birds as they rise from cover. Their never ending flight, graceful as it is, becomes monotonous to the watcher. Pressed by hunger, they attack even wild ducks.

In New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, where it sweeps over the low lands, sailing near the earth, in search of a kind of mouse very common in such situations, it is chiefly known as the Mouse Hawk. In the southern rice fields it is useful in preventing to some extent the ravages of the swarms of Bobolinks. It has been stated that one Marsh Hawk was considered by planters equal to several negroes for alarming the rice birds. This Hawk when feeding is readily approached.

The birds nest in low lands near the sea shore, in the barrens, and on the clear table-lands of the Alleghanies, and once a nest was found in a high covered pine barrens of Florida.

The Marsh Hawks always keep together after pairing, working jointly in building the nest, in sitting upon the eggs, and in feeding the young. The nest is clumsily made of hay, occasionally lined with feathers, pine needles, and small twigs. It is built on the ground, and contains from three to five eggs of a bluish white color, usually more or less marked with purplish brown blotches. Early May is their breeding time.

It will be observed that even the Hawk, rapacious as he undoubtedly is, is a useful bird. Sent for the purpose of keeping the small birds in bounds, he performs his task well, though it may seem to man harsh and tyranical. The Marsh Hawk is an ornament to our rural scenery, and a pleasing sight as he darts silently past in the shadows of falling night.

marsh hawk.

marsh hawk.Bird of the Merry Heart.

Here is a picture of a bird that is always merry. He is a bold, saucy little fellow, too, but we all love him for it. Don’t you think he looks some like the Canada Jay that you saw in April “Birds?”

I think most of you must have seen him, for he stays with us all the year, summer and winter. If you ever heard him, you surely noticed how plainly he tells you his name. Listen—“Chick-a-dee-dee; Chick-a-dee; Hear, hear me”—That’s what he says as he hops about from twig to twig in search of insects’ eggs and other bits for food. No matter how bitter the wind or how deep the snow, he is always around—the same jolly, careless little fellow, chirping and twittering his notes of good cheer.

Like the Yellow Warblers on page 169, Chickadees like best to make their home in an old stump or hole in a tree—not very high from the ground. Sometimes they dig for themselves a new hole, but this is only when they cannot find one that suits them.

The Chickadee is also called Black-capped Titmouse. If you look at his picture you will see his black cap. You’ll have to ask someone why he is called Titmouse. I think Chickadee is the prettier name, don’t you?

If you want to get well acquainted with this saucy little bird, you want to watch for him next winter, when most of the birds have gone south. Throw him crumbs of bread and he will soon be so tame as to come right up to the door step.

LYCATCHERS are all interesting, and many of them are beautiful, but the Scissor-tailed species of Texas is especially attractive. They are also known as the Swallow-tailed Flycatcher, and more frequently as the “Texan Bird of Paradise.” It is a common summer resident throughout the greater portion of that state and the Indian Territory, and its breeding range extends northward into Southern Kansas. Occasionally it is found in southwestern Missouri, western Arkansas, and Illinois. It is accidental in the New England states, the Northwest Territory, and Canada. It arrives about the middle of March and returns to its winter home in Central America in October. Some of the birds remain in the vicinity of Galveston throughout the year, moving about in small flocks.

There is no denying that the gracefulness of the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher should well entitle him to the admiration of bird-lovers, and he is certain to be noticed wherever he goes. The long outer tail feathers he can open and close at will. His appearance is most pleasing to the eye when fluttering slowly from tree to tree on the rather open prairie, uttering his twittering notes, “Spee-spee.” When chasing each other in play or anger these birds have a harsh note like “Thish-thish,” not altogether agreeable. Extensive timber land is shunned by this Flycatcher, as it prefers more open country, though it is often seen in the edges of woods. It is not often seen on the ground, where its movements are rather awkward. Its amiability and social disposition are observed in the fact that several pairs will breed close to each other in perfect harmony. Birds smaller than itself are rarely molested by it, but it boldly attacks birds of prey. It is a restless bird, constantly on the lookout for passing insects, nearly all of which are caught on the wing and carried to a perch to be eaten. It eats moths, butterflies, beetles, grasshoppers, locusts, cotton worms, and, to some extent, berries. Its usefulness cannot be doubted. According to Major Bendire, these charming creatures seem to be steadily increasing in numbers, being far more common in many parts of Texas, where they are a matter of pride with the people, than they were twenty years ago.

The Scissor-tails begin housekeeping some time after their arrival from Central America, courting and love making occupying much time before the nest is built. They are not hard to please in the selection of a suitable nesting place, almost any tree standing alone being selected rather than a secluded situation. The nest is bulky, commonly resting on an exposed limb, and is made of any material that may be at hand. They nest in oaks, mesquite, honey locust, mulberry, pecan, and magnolia trees, as well as in small thorny shrubs, from five to forty feet from the ground. Rarely molested they become quite tame. Two broods are often raised. The eggs are usually five. They are hatched by the female in twelve days, while the male protects the nest from suspicious intruders. The young are fed entirely on insects and are able to leave the nest in two weeks. The eggs are clear white, with markings of brown, purple, and lavender spots and blotches.

scissor-tailed flycatcher.

scissor-tailed flycatcher.

“Chic-chickadee dee!” I saucily say;

My heart it is sound, my throat it is gay!

Every one that I meet I merrily greet

With a chickadee dee, chickadee dee!

To cheer and to cherish, on roadside and street,

My cap was made jaunty, my note was made sweet.

Chickadeedee, Chickadeedee!

No bird of the winter so merry and free;

Yet sad is my heart, though my song one of glee,

For my mate ne’er shall hear my chickadeedee.

I “chickadeedee” in forest and glade,

“Day, day, day!” to the sweet country maid;

From autumn to spring time I utter my song

Of chickadeedee all the day long!

The silence of winter my note breaks in twain,

And I “chickadeedee” in sunshine and rain.

Chickadeedee Chickadeedee!

No bird of the winter so merry and free;

Yet sad is my heart, though my song one of glee,

For my mate ne’er shall hear my chickadeedee.—C. C. M.

SAUCY little bird, so active and familiar, the Black-Capped Chickadee, is also recognized as the Black Capped Titmouse, Eastern Chickadee, and Northern Chickadee. He is found in the southern half of the eastern United States, north to or beyond forty degrees, west to eastern Texas and Indian Territory.

The favorite resorts of the Chickadee are timbered districts, especially in the bottom lands, and where there are red bud trees, in the soft wood of which it excavates with ease a hollow for its nest. It is often wise enough, however, to select a cavity already made, as the deserted hole of the Downy Woodpecker, a knot hole, or a hollow fence rail. In the winter season it is very familiar, and is seen about door yards and orchards, even in towns, gleaning its food from the kitchen remnants, where the table cloth is shaken, and wherever it may chance to find a kindly hospitality.

In an article on “Birds as Protectors of Orchards,” Mr. E. H. Forbush says of the Chickadee: “There is no bird that compares with it in destroying the female canker-worm moths and their eggs.” He calculated that one Chickadee in one day would destroy 5,550 eggs, and in the twenty-five days in which the canker-worm moths run or crawl up the trees 138,750 eggs. Mr. Forbush attracted Chickadees to one orchard by feeding them in winter, and he says that in the following summer it was noticed that while trees in neighboring orchards were seriously damaged by canker-worms, and to a less degree by tent caterpillars, those in the orchard which had been frequented by the Chickadee during the winter and spring were not seriously infested, and that comparatively few of the worms and caterpillars were to be found there. His conclusion is that birds that eat eggs of insects are of the greatest value to the farmer, as they feed almost entirely on injurious insects and their eggs, and are present all winter, where other birds are absent.

The tiny nest of the Chickadee is made of all sorts of soft materials, such as wool, fur, feathers, and hair placed in holes in stumps of trees. Six to eight eggs are laid, which are white, thickly sprinkled with warm brown.

Mrs. Osgood Wright tells a pretty incident of the Chickadees, thus: “In the winter of 1891-2, when the cold was severe, the snow deep, and the tree trunks often covered with ice, the Chickadees repaired in flocks daily to the kennel of our old dog Colin and fed from his dish, hopping over his back and calling Chickadee, dee, dee, in his face, a proceeding that he never in the least resented, but seemed rather to enjoy it.”

Quite a long name for such small birds—don’t you think so? You will have to get your teacher to repeat it several times, I fear, before you learn it.

These little yellow warblers are just as happy as the pair of wrens I showed you in April “Birds.” In fact, I suspect they are even happier, for their nest has been made and the eggs laid. What do you think of their house? Sometimes they find an old hole in a stump, one that a woodpecker has left, perhaps, and there build a nest. This year they have found a very pretty place to begin their housekeeping. What kind of tree is it? I thought I would show only the part of the tree that makes their home. I just believe some boy or girl who loves birds made those holes for them. Don’t you think so? They have an upstairs and a down stairs, it seems.

Like the Wrens I wrote about last month, they prefer to live in swampy land and along rivers. They nearly always find a hole in a decayed willow tree for their nest—low down. This isn’t a willow tree, though.

Whenever I show you a pair of birds, always pick out the father and the mother bird. You will usually find that one has more color than the other. Which one is it? Maybe you know why this is. If you don’t I am sure your teacher can tell you. Don’t you remember in the Bobolink family how differently Mr. and Mrs. Bobolink were dressed?

I think most of you will agree with me when I say this is one of the prettiest pictures you ever saw.

chickadee.

chickadee. prothonotary warbler.

prothonotary warbler.

HE Golden Swamp Warbler is one of the very handsomest of American birds, being noted for the pureness and mellowness of its plumage. Baird notes that the habits of this beautiful and interesting warbler were formerly little known, its geographical distribution being somewhat irregular and over a narrow range. It is found in the West Indies and Central America as a migrant, and in the southern region of the United States. Further west the range widens, and it appears as far north as Kansas, Central Illinois, and Missouri.

Its favorite resorts are creeks and lagoons overshadowed by large trees, as well as the borders of sheets of water and the interiors of forests. It returns early in March to the Southern states, but to Kentucky not before the last of April, leaving in October. A single brood only is raised in a season.

A very pretty nest is sometimes built within a Woodpecker’s hole in a stump of a tree, not more than three feet high. Where this occurs the nest is not shaped round, but is made to conform to the irregular cavity of the stump. This cavity is deepest at one end, and the nest is closely packed with dried leaves, broken bits of grasses, stems, mosses, decayed wood, and other material, the upper part interwoven with fine roots, varying in size, but all strong, wiry, and slender, and lined with hair.

Other nests have been discovered which were circular in shape. In one instance the nest was built in a brace hole in a mill, where the birds could be watched closely as they carried in the materials. They were not alarmed by the presence of the observer but seemed quite tame.

So far from being noisy and vociferous, Mr. Ridgway describes it as one of the most silent of all the warblers, while Mr. W. Brewster maintains that in restlessness few birds equal this species. Not a nook or corner of his domain but is repeatedly visited during the day. “Now he sings a few times from the top of some tall willow that leans out over the stream, sitting motionless among the marsh foliage, fully aware, perhaps, of the protection afforded by his harmonizing tints. The next moment he descends to the cool shadows beneath, where dark, coffee-colored waters, the overflow of a pond or river, stretch back among the trees. Here he loves to hop about the floating drift-wood, wet by the lapping of pulsating wavelets, now following up some long, inclining, half submerged log, peeping into every crevice and occasionally dragging forth from its concealment a spider or small beetle, turning alternately its bright yellow breast and olive back towards the light; now jetting his beautiful tail, or quivering his wings tremulously, he darts off into some thicket in response to a call from his mate; or, flying to a neighboring tree trunk, clings for a moment against the mossy hole to pipe his little strain, or look up the exact whereabouts of some suspected insect prize.”

HE Indigo Bunting’s arrival at its summer home is usually in the early part of May, where it remains until about the middle of September. It is numerous in the eastern and middle states, inhabiting the continent and seacoast islands from Mexico, where they winter, to Nova Scotia. It is one of the very smallest of our birds, and also one of the most attractive. Its favorite haunts are gardens, fields of deep clover, the borders of woods, and roadsides, where, like the Woodpecker, it is frequently seen perched on the fences.

It is extremely active and neat in its manners and an untiring singer, morning, noon, and night his rapid chanting being heard, sometimes loud and sometimes hardly audible, as if he were becoming quite exhausted by his musical efforts. He mounts the highest tops of a large tree and sings for half an hour together. The song is not one uninterrupted strain, but a repetition of short notes, “commencing loud, and rapid, and full, and by almost imperceptible gradations for six or eight seconds until they seem hardly articulated, as if the little minstrel were unable to stop, and, after a short pause, beginning again as before.” Baskett says that in cases of serenade and wooing he may mount the tip sprays of tall trees as he sings and abandon all else to melody till the engrossing business is over.

The Indigo Bird sings with equal animation whether it be May or August, the vertical sun of the dog days having no diminishing effect upon his enthusiasm. It is well known that in certain lights his plumage appears of a rich sky blue, varying to a tint of vivid verdigris green, so that the bird, flitting from one place to another, appears to undergo an entire change of color.

The Indigo Bunting fixes his nest in a low bush, long rank grass, grain, or clover, suspended by two twigs, flax being the material used, lined with fine dry grass. It had been known, however, to build in the hollow of an apple tree. The eggs, generally five, are bluish or pure white. The same nest is often occupied season after season. One which had been used for five successive summers, was repaired each year with the same material, matting that the birds had evidently taken from the covering of grape vines. The nest was very neatly and thoroughly lined with hair.

The Indigo feeds upon the ground, his food consisting mainly of the seed of small grasses and herbs. The male while moulting assumes very nearly the color of the female, a dull brown, the rich plumage not returning for two or three months. Mrs. Osgood Wright says of this tiny creature: “Like all the bright-hued birds he is beset by enemies both of earth and sky, but his sparrow instinct, which has a love for mother earth, bids him build near the ground. The dangers of the nesting-time fall mostly to his share, for his dull brown mate is easily overlooked as an insignificant sparrow. Nature always gives a plain coat to the wives of these gayly dressed cavaliers, for her primal thought is the safety of the home and its young life.”

indigo bird.

indigo bird.

HE range of the Night Hawk, also known as “Bull-bat,” “Mosquito Hawk,” “Will o’ the Wisp,” “Pisk,” “Piramidig,” and sometimes erroneously as “Whip-poor-will,” being frequently mistaken for that bird, is an extensive one. It is only a summer visitor throughout the United States and Canada, generally arriving from its winter haunts in the Bahamas, or Central and South America in the latter part of April, reaching the more northern parts about a month later, and leaving the latter again in large straggling flocks about the end of August, moving leisurely southward and disappearing gradually along our southern border about the latter part of October. Major Bendire says its migrations are very extended and cover the greater part of the American continent.

The Night Hawk, in making its home, prefers a well timbered country. Its common name is somewhat of a misnomer, as it is not nocturnal in its habits. It is not an uncommon sight to see numbers of these birds on the wing on bright sunny days, but it does most of its hunting in cloudy weather, and in the early morning and evening, returning to rest soon after dark. On bright moonlight nights it flies later, and its calls are sometimes heard as late as eleven o’clock.

“This species is one of the most graceful birds on the wing, and its aerial evolutions are truly wonderful; one moment it may be seen soaring through space without any apparent movement of its pinions, and again its swift flight is accompanied by a good deal of rapid flapping of the wings, like that of Falcons, and this is more or less varied by numerous twistings and turnings. While constantly darting here and there in pursuit of its prey,” says a traveler, “I have seen one of these birds shoot almost perpendicularly upward after an insect, with the swiftness of an arrow. The Night Hawk’s tail appears to assist it greatly in these sudden zigzag changes, being partly expanded during most of its complicated movements.”

Night Hawks are sociable birds, especially on the wing, and seem to enjoy each other’s company. Their squeaking call note, sounding like “Speek-speek,” is repeated at intervals. These aerial evolutions are principally confined to the mating season. On the ground the movements of this Hawk are slow, unsteady, and more or less laborious. Its food consists mainly of insects, such as flies and mosquitos, small beetles, grasshoppers, and the small night-flying moths, all of which are caught on the wing. A useful bird, it deserves the fullest protection.

The favorite haunts of the Night Hawk are the edges of forests and clearings, burnt tracts, meadow lands along river bottoms, and cultivated fields, as well as the flat mansard roofs in many of our larger cities, to which it is attracted by the large amount of food found there, especially about electric lights. During the heat of the day the Night Hawk may be seen resting on limbs of trees, fence rails, the flat surface of lichen-covered rock, on stone walls, old logs, chimney tops, and on railroad tracks. It is very rare to find it on the ground.

The nesting-time is June and July. No nest is made, but two eggs are deposited on the bare ground, frequently in very exposed situations, or in slight depressions on flat rocks, between rows of corn, and the like. Only one brood is raised. The birds sit alternately for about sixteen days. There is endless variation in the marking of the eggs, and it is considered one of the most difficult to describe satisfactorily.

As you will see from my name, I am a bird of the night. Daytime is not at all pleasing to me because of its brightness and noise.

I like the cool, dark evenings when the insects fly around the house-tops. They are my food and it needs a quick bird to catch them. If you will notice my flight, you will see it is swift and graceful. When hunting insects we go in a crowd. It is seldom that people see us because of the darkness. Often we stay near a stream of water, for the fog which rises in the night hides us from the insects on which we feed.

None of us sing well—we have only a few doleful notes which frighten people who do not understand our habits.

In the daytime we seek the darkest part of the woods, and perch lengthwise on the branches of trees, just as our cousins the Whippoorwills do. We could perch crosswise just as well. Can you think why we do not? If there be no woods near, we just roost upon the ground.

Our plumage is a mottled brown—the same color of the bark on which we rest. Our eggs are laid on the ground, for we do not care to build nests. There are only two of them, dull white with grayish brown marks on them.

Sometimes we lay our eggs on flat roofs in cities, and stay there during the day, but we prefer the country where there is good pasture land. I think my cousin Whippoorwill is to talk to you next month. People think we are very much alike. You can judge for yourself when you see his picture.

night hawk.

night hawk.

“With what a clear

And ravishing sweetness sang the plaintive Thrush;

I love to hear his delicate rich voice,

Chanting through all the gloomy day, when loud

Amid the trees is dropping the big rain,

And gray mists wrap the hill; foraye the sweeter

His song is when the day is sad and dark.”

O many common names has the Wood Thrush that he would seem to be quite well known to every one. Some call him the Bell Thrush, others Bell Bird, others again Wood Robin, and the French Canadians, who love his delicious song, Greve des Bois and Merle Taune. In spite of all this, however, and although a common species throughout the temperate portions of eastern North America, the Wood Thrush can hardly be said to be a well-known bird in the same sense as the Robin, the Catbird, or other more familiar species; “but to every inhabitant of rural districts his song, at least, is known, since it is of such a character that no one with the slightest appreciation of harmony can fail to be impressed by it.”

Some writers maintain that the Wood Thrush has a song of a richer and more melodious tone than that of any other American bird; and that, did it possess continuity, would be incomparable.

Damp woodlands and shaded dells are favorite haunts of this Thrush, but on some occasions he will take up his residence in parks within large cities. He is not a shy bird, yet it is not often that he ventures far from the wild wood of his preference.

The nest is commonly built upon a horizontal branch of a low tree, from six to ten—rarely much more—feet from the ground. The eggs are from three to five in number, of a uniform greenish color; thus, like the nest, resembling those of the Robin, except that they are smaller.

In spite of the fact that his name indicates his preference for the woods, we have seen this Thrush, in parks and gardens, his brown back and spotted breast making him unmistakable as he hops over the grass for a few yards, and pauses to detect the movement of a worm, seizing it vigorously a moment after.

He eats ripening fruits, especially strawberries and gooseberries, but no bird can or does destroy so many snails, and he is much less an enemy than a friend of the gardener. It would be well if our park commissioners would plant an occasional fruit tree—cherry, apple, and the like—in the public parks, protecting them from the ravages of every one except the birds, for whose sole benefit they should be set aside. The trees would also serve a double purpose of ornament and use, and the youth who grow up in the city, and rarely ever see an orchard, would become familiar with the appearance of fruit trees. The birds would annually increase in numbers, as they would not only be attracted to the parks thereby, but they would build their nests and rear their young under far more favorable conditions than now exist. The criticism that birds are too largely destroyed by hunters should be supplemented by the complaint that they are also allowed to perish for want of food, especially in seasons of unusual scarcity or severity. Food should be scattered through the parks at proper times, nesting boxes provided—not a few, but many—and then

The happy mother of every brood

Will twitter notes of gratitude.

The Bird of Solitude.

Of all the Thrushes this one is probably the most beautiful. I think the picture shows it. Look at his mottled neck and breast. Notice his large bright eye. Those who have studied birds think he is the most intelligent of them all.

He is the largest of the Thrushes and has more color in his plumage. All who have heard him agree that he is one of the sweetest singers among birds.

Unlike the Robin, Catbird, or Brown Thrush, he enjoys being heard and not seen.

His sweetest song may be heard in the cool of the morning or evening. It is then that his rich notes, sounding like a flute, are heard from the deep wood. The weather does not affect his song. Rain or shine, wet or dry, he sings, and sings, and sings.

During the light of day the Wood Thrush likes to stay in the cool shade of the woods.

Along toward evening, after sunset, when other birds are settling themselves for the night, out of the wood you will hear his evening song.

It begins with a strain that sounds like, “Come with me,” and by the time he finishes you are in love with his song.

The Wood Thrush is very quiet in his habits. So different from the noisy, restless Catbird.

The only time that he is noisy is when his young are in danger. Then he is as active as any of them.

A Wood Thrush’s nest is very much like a Robin’s. It is made of leaves, rootlets and fine twigs woven together with an inner wall of mud, and lined with fine rootlets.

The eggs, three to five, are much like the Robin’s.

Compare the picture of the Wood Thrush with that of the Robin or Brown Thrush and see which you think is the prettiest.

wood thrush.

wood thrush.

HE CATBIRD derives his name from a fancied resemblance of some of his notes to the mew of the domestic cat. He is a native of America, and is one of the most familiarly known of our famous songsters. He is a true thrush, and is one of the most affectionate of our birds. Wilson has well described his nature, as follows:

“In passing through the woods in summer I have sometimes amused myself with imitating the violent chirping or clucking of young birds, in order to observe what different species were round me; for such sounds at such a season in the woods are no less alarming to the feathered tenants of the bushes than the cry of fire or murder in the street is to the inhabitants of a large city. On such occasion of alarm and consternation, the Catbird is first to make his appearance, not single but sometimes half a dozen at a time, flying from different quarters to the spot. At this time those who are disposed to play on his feelings may almost throw him into a fit, his emotion and agitation are so great at what he supposes to be the distressful cries of his young. He hurries backward and forward, with hanging wings, open mouth, calling out louder and faster, and actually screaming with distress, until he appears hoarse with his exertions. He attempts no offensive means, but he wails, he implores, in the most pathetic terms with which nature has supplied him, and with an agony of feeling which is truly affecting. At any other season the most perfect imitations have no effect whatever on him.”

The Catbird is a courageous little creature, and in defense of its young it is so bold that it will contrive to drive away any snake that may approach its nest, snakes being its special aversion. His voice is mellow and rich, and is a compound of many of the gentle trills and sweet undulations of our various woodland choristers, delivered with apparent caution, and with all the attention and softness necessary to enable the performer to please the ear of his mate. Each cadence passes on without faltering and you are sure to recognize the song he so sweetly imitates. While they are are all good singers, occasionally there is one which excels all his neighbors, as is frequently the case among canaries.

The Catbird builds in syringa bushes, and other shrubs. In New England he is best known as a garden bird. Mabel Osgood Wright, in “Birdcraft,” says: “I have found it nesting in all sorts of places, from an alder bush, overhanging a lonely brook, to a scrub apple in an open field, never in deep woods, and it is only in its garden home, and in the hedging bushes of an adjoining field, that it develops its best qualities—‘lets itself out,’ so to speak. The Catbirds in the garden are so tame that they will frequently perch on the edge of the hammock in which I am sitting, and when I move they only hop away a few feet with a little flutter. The male is undoubtedly a mocker, when he so desires, but he has an individual and most delightful song, filled with unexpected turns and buoyant melody.”

What do you think of this nest of eggs? What do you suppose Mrs. Catbird’s thoughts are as she looks at them so tenderly? Don’t you think she was very kind to let me take the nest out of the hedge where I found it, so you could see the pretty greenish blue eggs? I shall place it back where I got it. Catbirds usually build their nests in hedges, briars, or bushes, so they are never very high from the ground.

Did you ever hear the Catbird sing? He is one of the sweetest singers and his song is something like his cousin’s, the Brown Thrush, only not so loud.

He can imitate the songs of other birds and the sounds of many animals. He can mew like a cat, and it is for this reason that he is called “Catbird.” His sweetest song, though, is soft and mellow and is sung at just such times as this—when thinking of the nest, the eggs, or the young.

The Catbird is a good neighbor among birds. If any other bird is in trouble of any sort, he will do all he can to relieve it. He will even feed and care for little birds whose parents have left them. Don’t you think he ought to have a prettier name? Now remember, the Catbird is a Thrush. I want you to keep track of all the Thrushes as they appear in “Birds.” I shall try to show you a Thrush each month.

Next month you shall see the sweetest singer of American birds. He, too, is a Thrush. I wonder if you know what bird I mean. Ask your mamma to buy you a book called “Bird Ways.” It was written by a lady who spent years watching and studying birds. She tells so many cute things about the Catbird.

catbird.

catbird.

flash light picture made with “dexter” camera.

flash light picture made with “dexter” camera.

MATEUR PHOTOGRAPHY is the most delightful pastime one can indulge in. Aside from the pleasure and amusement derived, it cultivates the artistic taste, the love of nature, is a source of instruction, and may be made to serve many useful purposes. The “Dexter” is small, neat and compact. Makes pictures 31⁄2×31⁄2 inches square and will produce portraits, landscapes, groups, interiors or flashlights equally as well as many higher priced cameras. Will carry three double plate holders with a capacity of six dry plates. Each camera is covered with black morocco grain leather, also provided with a brilliant finder for snap shot work. Has a Bausch & Lomb single acromatic lens of wonderful depth and definition and a compound time and instantaneous shutter which is a marvel of ingenuity. A separate button is provided for time and instantaneous work so that a twist of a button or pulling of a lever is not necessary as in most cameras. A tripod socket is also provided so that it can be used for hand or tripod work as desired. All complicated adjustments have been dispensed with so that the instrument can be manipulated with ease by the youngest amateur. Full and explicit instructions are sent with each camera. Send 5c stamps for sample picture and descriptive circulars.

elkhart lake.

elkhart lake.

SUMMER Excursion Tickets to the resorts of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Michigan, Colorado, California, Montana, Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia; also to Alaska, Japan, China,and all Trans-Pacific Points, are now on sale by the CHICAGO, MILWAUKEE & ST. PAUL RAILWAY. Full and reliable information can be had by applying to Mr. C. N. SOUTHER, Ticket Agent, 95 Adams Street, Chicago.

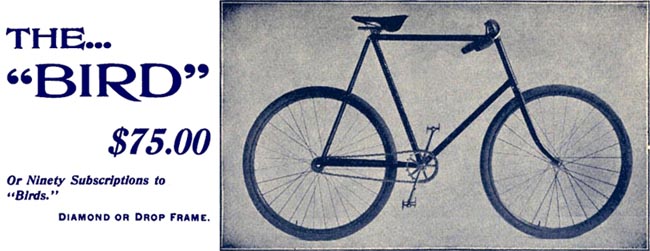

This wheel is made especially for the Nature Study Publishing Co., to be used as a premium. It is unique in design, of material the best, of workmanship unexcelled. No other wheel on the market can compare favorably with it for less than $100.00.

SPECIFICATIONS FOR 1897 “BIRD” BICYCLE.

Frame.—Diamond pattern; cold-drawn seamless steel tubing; 11⁄8 inch tubing in the quadrangle with the exception of the head, which is 11⁄4inch. Height, 23, 24, 25 and 26 inches. Rear triangle 3⁄4 inch tubing in the lower and upright bars. Frame Parts.—Steel drop forgings, strongly reinforced connections. Forks.—Seamless steel fork sides, gracefully curved and mechanically reinforced. Steering Head.—9, 11 and 13 inches long, 11⁄4 inches diameter. Handle Bar.—Cold-drawn, weldless steel tubing, 7⁄8 inch in diameter, ram’s horn, upright or reversible, adapted to two positions. Handles.—Cork or corkaline; black, maroon or bright tips. Wheels.—28 inch, front and rear. Wheel Base.—43 inches. Rims.—Olds or Plymouth. Tires.—Morgan & Wright, Vim, or Hartford. Spokes.—Swaged, Excelsior Needle Co.’s best quality; 28 in front and 32 in rear wheel. Cranks.—Special steel, round and tapered; 61⁄2 inch throw. Pedals.—Brandenburg; others on order. Chain.—1⁄4 inch, solid link, with hardened rivet steel centers. Saddle.—Black, attractive and comfortable; our own make. Saddle Post.—Adjustable, style “T.” Tread. —47⁄8 inches. Sprocket Wheels.—Steel drop forgings, hardened. Gear.—68 regular; other gears furnished if so desired. Bearings.—Made of the best selected high-grade tool steel, carefully ground to a finish after tempering, and thoroughly dust-proof. All cups are screwed into hubs and crank hangers. Hubs.—Large tubular hubs, made from a solid bar of steel. Furnishing.—Tool-bag, wrench, oiler, pump and repair kit. Tool Bags.—In black or tan leather, as may be preferred. Handle bar, hubs, sprocket wheels, cranks, pedals, seat post, spokes, screws, nuts and washers, nickel plated over copper; remainder enameled. Weight.—22 and 24 pounds.

Send for Specifications for Diamond Frame.

OTHER PREMIUMS OFFERED.

“Bird” Wheel No. 2, ’97 model,...............................................

Price $60.00, given for 70 subscriptions to “Birds.”

Boys’ “Bird” or Girls’ “Bird,” ’97 model,....................................

Price $45.00, given for 50 subscriptions to “Birds.”

The Monarch ’97 Model Bicycle,.........................................

Price $100.00, given for 150 subscriptions to “Birds.”

The Racycle, Narrow Tread, ’97 model,...............................

Price $100.00, given for 150 subscriptions to “Birds.”

The “Dexter” Camera. Pictures

31⁄2 × 31⁄2.

$4.00, or eight subscriptions to “Birds.”

Produces portraits, landscapes, groups and flashlights better than many higher priced instruments. It will hold three double plate holder with a capacity of six dry plates. It is covered with black morocco grain leather, and provided with finder. Send for full description. Price $4.00, or eight subscriptions to “Birds.”

Photake Camera. Pictures 2 × 2, portraits, landscapes, flashlight. Price $2.50, or six subscriptions to “Birds.”

The “Lakeside” Tennis Racket. Price $4.00, or nine subscriptions to “Birds.”

The “Greenwood” Tennis Racket. Price $3.30, or seven subscriptions to “Birds.”

The Crown Fountain Pen,......................................................

Price $2.25, given for three subscriptions to “Birds.”

The Stay-Lit Bicycle Lamp,......................................................

Price $2.50, given for five subscriptions to “Birds.”

Youth’s Companion and Reversible Blackboard,.....................

Price $3.50, given for eight subscriptions to “Birds.”

Webster’s International Dictionary—sheep—indexed,............

Price $10.75, twenty annual subscriptions to “Birds.”

Oxford Bibles,............................

Prices $3.70 to $10.70, given for seven to twenty annual subscriptions to “Birds.”

The Twentieth Century Library,.............................

Price, each $1.00, given for two annual subscriptions to “Birds.”

Tuxedo Edition of Poets,.......................................

Price, each $1.00, given for two annual subscriptions to “Birds.”

The Story of the Birds, 12mo., cloth,...............................

Price 65c, given for three annual subscriptions to “Birds.”

We call special attention to The Story of the Birds, by James Newton Baskett, M. A., as an interesting book to be read in connection with our magazine, “BIRDS.” It is well written and finely illustrated. Persons interested in Bird Day should have one of these books. We can furnish nearly any book of the Poets or Fiction or School Books as premiums to “BIRDS.” We can furnish almost any article on the market as premiums for subscriptions to “BIRDS,” either fancy or sporting goods, musical instruments, including high-grade pianos, or any book published in this country. We will gladly quote price or number of subscriptions necessary.

Agents Wanted in every Town and City to represent “BIRDS.” CHICAGO.

We give below a list of publications, especially fine, to be read in connection with our new magazine, and shall be glad to supply them at the price indicated, or as premiums for subscriptions for “Birds.”

| “Birds Through an Opera Glass” | 75c. | or | 2 | subscriptions. | ||||

| “Bird Ways” | 60c. | “ | 2 | “ | ||||

| “In Nesting Time” | $1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “A Bird Lover of the West” | 1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “Upon the Tree Tops” | 1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “Wake Robin” | 1.00 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “Birds in the Bush” | 1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “A-Birding on a Bronco” | 1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “Land Birds and Game Birds of New England” | 3.50 | “ | 8 | “ | ||||

| “Birds and Poets” | 1.25 | “ | 3 | “ | ||||

| “Bird Craft” | 3.00 | “ | 7 | “ | ||||

| “The Story of the Birds” | .65 | “ | 2 | “ | ||||

| “Hand Book of Birds of Eastern North America” | 3.00 | “ | 7 | “ |

See our notice on another page concerning Bicycles. Our “Bird” Wheel is one of the best on the market—as neat and attractive as “Birds.”

We shall be glad to quote a special price for teachers or clubs.

We can furnish any article or book as premium for subscriptions for “Birds.”

Address,

HE Nature Study Publishing Company is a corporation of educators and business men organized to furnish correct reproductions of the colors and forms of nature to families, schools, and scientists. Having secured the services of artists who have succeeded in photographing and reproducing objects in their natural colors, by a process whose principles are well known but in which many of the details are held secret, we obtained a charter from the Secretary of State in November, 1896, and began at once the preparation of photographic color plates for a series of pictures of birds.

The first product was the January number of “BIRDS,” a monthly magazine, containing ten plates with descriptions in popular language, avoiding as far as possible scientific and technical terms. Knowing the interest children have in our work, we have included in each number a few pages of easy text pertaining to the illustrations. These are usually set facing the plates to heighten the pleasure of the little folks as they read.

Casually noticed, the magazine may appear to be a children’s publication because of the placing of this juvenile text. But such is not the case. Those scientists who cherish with delight the famous handiwork of Audubon are no less enthusiastic over these beautiful pictures which are painted by the delicate and scientifically accurate fingers of Light itself. These reproductions are true. There is no imagination in them nor conventionalism. In the presence of their absolute truth any written description or work of human hands shrinks into insignificance. The scientific value of these photographs can not be estimated.

To establish a great magazine with a world-wide circulation is no light undertaking. We have been steadily and successfully working towards that end. Delays have been unavoidable. What was effective for the production of a limited number of copies was inadequate as our orders increased. The very success of the enterprise has sometimes impeded our progress. Ten hundred teachers in Chicago paid subscriptions in ten days. Boards of Education are subscribing in hundred lots. Improvements in the process have been made in almost every number, and we are now assured of a brilliant and useful future.

When “BIRDS” has won its proper place in public favor we shall be prepared to issue a similar serial on other natural objects, and look for an equally cordial reception for it.

PREMIUMS.

To teachers we give duplicates of all the pictures on separate sheets for use in teaching or for decoration.

To other subscribers we give a color photograph of one of the most gorgeous birds, the Golden Pheasant.

Subscriptions, $1.50 a year including one premium. Those wishing both premiums may receive them and a year’s subscription for $2.00.

We have just completed an edition of 50,000 back numbers to accommodate those who wish their subscriptions to date back to January, 1897, the first number.

We will furnish the first volume, January to June inclusive, well bound in cloth, postage paid, for $1.25. In Morocco, $2.25.

AGENTS.

10,000 agents are wanted to travel or solicit at home.

We have prepared a fine list of desirable premiums for clubs which any popular adult or child can easily form. Your friends will thank you for showing them the magazine and offering to send their money. The work of getting subscribers among acquaintances is easy and delightful. Agents can do well selling the bound volume. Vol. 1 is the best possible present for a young person or for anyone specially interested in nature.

Teachers and others meeting them at institutes do well as our agents. The magazine sells to teachers better than any other publication because they can use the extra plates for decoration, language work, nature study, and individual occupation.

NATURE STUDY PUBLISHING COMPANY,

277 Dearborn Street, Chicago.