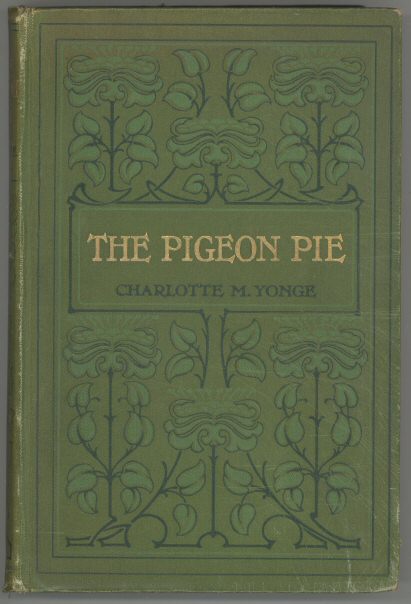

Title: The Pigeon Pie

Author: Charlotte M. Yonge

Release date: April 1, 2001 [eBook #2606]

Most recently updated: January 10, 2015

Language: English

Credits: Transcribed from the 1905 A. R. Mowbray & Co. edition by David Price

Transcribed from the 1905 A. R. Mowbray & Co. edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

BY

CHARLOTTE M. YONGE

Author of “The Heir of Redclyffe”

NEW EDITION

A. R. MOWBRAY & CO. Limited

Oxford: 106, S. Aldate’s

Street

London: 34, Great Castle Street,

Oxford Circus, W

1905

|

PAGE |

Chapter I. |

|

Chapter II. |

|

Chapter III. |

|

Chapter IV. |

|

Chapter V. |

|

Chapter VI. |

|

Chapter VII. |

|

Chapter VIII. |

|

Chapter IX. |

Early in the September of the year 1651 the afternoon sun was shining pleasantly into the dining-hall of Forest Lea House. The sunshine came through a large bay-window, glazed in diamonds, and with long branches of a vine trailing across it, but in parts the glass had been broken and had never been mended. The walls were wainscoted with dark oak, as well as the floor, which shone bright with rubbing, and stag’s antlers projected from them, on which hung a sword in its sheath, one or two odd gauntlets, an old-fashioned helmet, a gun, some bows and arrows, and two of the broad shady hats then in use, one with a drooping black feather, the other plainer and a good deal the worse for wear, both of a small size, as if belonging to a young boy.

An oaken screen crossed the hall, close to the front door, and there was a large open fireplace, a settle on each side under the great yawning chimney, where however at present no fire was burning. Before it was a long dining-table covered towards the upper end with a delicately white cloth, on which stood, however, a few trenchers, plain drinking-horns, and a large old-fashioned black-jack, that is to say, a pitcher formed of leather. An armchair was at the head of the table, and heavy oaken benches along the side.

A little boy of six years old sat astride on the end of one of the benches, round which he had thrown a bridle of plaited rushes, and, with a switch in his other hand, was springing himself up and down, calling out, “Come, Eleanor, come, Lucy; come and ride on a pillion behind me to Worcester, to see King Charles and brother Edmund.”

“I’ll come, I am coming!” cried Eleanor, a little girl about a year older, her hair put tightly away under a plain round cap, and she was soon perched sideways behind her brother.

“Oh, fie, Mistress Eleanor; why, you would not ride to the wars?” This was said by a woman of about four or five-and-twenty, tall, thin and spare, with a high colour, sharp black eyes, and a waist which the long stiff stays, laced in front, had pinched in till it was not much bigger than a wasp’s, while her quilted green petticoat, standing out full below it, showed a very trim pair of ankles encased in scarlet stockings, and a pair of bony red arms came forth from the full short sleeves of a sort of white jacket, gathered in at the waist. She was clattering backwards and forwards, removing the dinner things, and talking to the children as she did so in a sharp shrill tone: “Such a racket as you make, to be sure, and how you can have the heart to do so I can’t guess, not I, considering what may be doing this very moment.”

“Oh, but Walter says they will all come back again, brother Edmund, and Diggory, and all,” said little Eleanor, “and then we shall be merry.”

“Yes,” said Lucy, who, though two years older, wore the same prim round cap and long frock as her little sister, “then we shall have Edmund here again. You can’t remember him at all, Eleanor and Charlie, for we have not seen him these six years!”

“No,” said Deborah, the maid. “Ah! these be weary wars, what won’t let a gentleman live at home in peace, nor his poor servants, who have no call to them.”

“For shame, Deb!” cried Lucy; “are not you the King’s own subject?”

But Deborah maundered on, “It is all very well for gentlefolks, but now it had all got quiet again, ’tis mortal hard it should be stirred up afresh, and a poor soul marched off, he don’t know where, to fight with he don’t know who, for he don’t know what.”

“He ought to know what!” exclaimed Lucy, growing very angry. “I tell you, Deb, I only wish I was a man! I would take the great two-handled sword, and fight in the very front rank for our Church and our King! You would soon see what a brave cavalier’s daughter—son I mean,” said Lucy, getting into a puzzle, “could do.”

The more eager Lucy grew, the more unhappy Deborah was, and putting her apron to her eyes, she said in a dismal voice, “Ah! ’tis little poor Diggory wots of kings and cavaliers!”

What Lucy’s indignation would have led her to say next can never be known, for at this moment in bounced a tall slim boy of thirteen, his long curling locks streaming tangled behind him. “Hollo!” he shouted, “what is the matter now? Dainty Deborah in the dumps? Cheer up, my lass! I’ll warrant that doughty Diggory is discreet enough to encounter no more bullets than he can reasonably avoid!”

This made Deborah throw down her apron and reply, with a toss of the head, “None of your nonsense, Master Walter, unless you would have me speak to my lady. Cry for Diggory, indeed!”

“She was really crying for him, Walter,” interposed Lucy.

“Mistress Lucy!” exclaimed Deborah, angrily, “the life I lead among you is enough—”

“Not enough to teach you good temper,” said Walter. “Do you want a little more?”

“I wish someone was here to teach you good manners,” answered the tormented Deborah. “As if it was not enough for one poor girl to have the work of ten servants on her hands, here must you be mock, mock, jeer, jeer, worrit, worrit, all day long! I had rather be a mark for all the musketeers in the Parliamentary army.”

This Deborah always said when she was out of temper, and it therefore made Walter and Lucy laugh the more; but in the midst of their merriment in came a girl of sixteen or seventeen, tall and graceful. Her head was bare, her hair fastened in a knot behind, and in little curls round her face; she had an open bodice of green silk, and a white dress under it, very plain and neat; her step was quick and active, but her large dark eyes had a grave thoughtful look, as if she was one who would naturally have loved to sit still and think, better than to bustle about and be busy. Eleanor ran up to her at once, complaining that Walter was teasing Deborah shamefully. She was going to speak, but Deborah cut her short.

“No Mistress Rose, I will not have even you excuse him, I’ll go and tell my lady how a poor faithful wench is served;” and away she flounced, followed by Rose.

“Will she tell mamma?” asked little Charlie.

“Oh no, Rose will pacify her,” said Lucy.

“I am sure I wish she would tell,” said Eleanor, a much graver little person than Lucy; “Walter is too bad.”

“It is only to save Diggory the trouble of taking a crabstick to her when he returns from the wars,” said Walter. “Heigh ho!” and he threw himself on the bench, and drummed on the table. “I wish I was there! I wonder what is doing at Worcester this minute!”

“When will brother Edmund come?” asked Charlie for about the hundredth time.

“When the battle is fought, and the battle is won, and King Charles enjoys his own again! Hurrah!” shouted Walter, jumping up, and beginning to sing—

“For forty years our royal throne

Has been his father’s and his own.”

Lucy joined in with—

“Nor is there anyone but he

With right can there a sharer be.”

“How can you make such a noise?” said Eleanor, stopping her ears, by which she provoked Walter to go on roaring into them, while he pulled down her hand—

“For who better may

The right sceptre sway

Than he whose right it is to reign;

Then look for no peace,

For the war will never cease

Till the King enjoys his own again.”

As he came to the last line, Rose returning exclaimed, “Oh, hush, Lucy. Pray don’t, Walter!”

“Ha! Rose turned Roundhead?” cried Walter. “You don’t deserve to hear the good news from Worcester.”

“O, what?” cried the girls, eagerly.

“When it comes,” said Walter, delighted to have taken in Rose herself; but Rose, going up to him gently, implored him to be quiet, and listen to her.

“All this noisy rejoicing grieves our mother,” said she. “If you could but have seen her yesterday evening, when she heard your loyal songs. She sighed, and said, ‘Poor fellow, how high his hopes are!’ and then she talked of our father and that evening before the fight at Naseby.”

Walter looked grave and said, “I remember! My father lifted me on the table to drink King Charles’s health, and Prince Rupert—I remember his scarlet mantle and white plume—patted my head, and called me his little cavalier.”

“We sat apart with mother,” said Rose, “and heard the loud cheers and songs till we were half frightened at the noise.”

“I can’t recollect all that,” said Lucy.

“At least you ought not to forget how our dear father came in with Edmund, and kissed us, and bade mother keep up a good heart. Don’t you remember that, Lucy?”

“I do,” said Walter; “it was the last time we ever saw him.”

And Walter sat on the table, resting one foot on the bench, while the other dangled down, and leaning his elbow on his knee and his head on his hand; Rose sat on the bench close by him, with Charlie on her lap, and the two little girls pressing close against her, all earnest to hear from her the story of the great fight of Naseby, where they had all been in a farmhouse about a mile from the field of battle.

“I don’t forget how the cannon roared all day,” said Lucy.

“Ah! that dismal day!” said Rose. “Then by came our troopers, blood-stained and disorderly, riding so fast that scarcely one waited to tell my mother that the day was lost and she had better fly. But not a step did she stir from the gate, where she stood with you, Charlie, in her arms; she only asked of each as he passed if he had seen my father or Edmund, and ever her cheek grew whiter and whiter. At last came a Parliament officer on horseback—it was Mr. Enderby, who had been a college mate of my father’s, and he told us that my dear father was wounded, and had sent him to fetch her.”

“But I never knew where Edmund was then,” said Eleanor. “No one ever told me.”

“Edmund lifted up my father when he fell,” said Walter, “and was trying to bind his wound; but when Colonel Enderby’s troop was close upon them, my father charged him upon his duty to fly, saying that he should fall into the hands of an old friend, and it was Edmund’s duty to save himself to fight for the King another time.”

“So Edmund followed Prince Rupert?” said Eleanor.

“Yes,” said Lucy; “you know my father once saved Prince Rupert’s life in the skirmish where his horse was killed, so for his sake the Prince made Edmund his page, and has had him with him in all his voyages and wanderings. But go on about our father, Rose. Did we go to see him?”

“No; Mr. Enderby said he was too far off, so he left a trooper to guard us, and my mother only took her little babe with her. Don’t you remember, Walter, how Eleanor screamed after her, as she rode away on the colonel’s horse; and how we could not comfort the little ones, till they had cried themselves to sleep, poor little things? And in the morning she came back, and told us our dear father was dead! O Walter, how can we look back to that day, and rejoice in a new war? How can you wonder her heart should sink at sounds of joy which have so often ended in tears?”

Walter twisted about and muttered, but he could not resist his sister’s earnest face and tearful eyes, and said something about not making so much noise in the house.

“There’s my own dear brother,” said Rose. “And you won’t tease Deborah?”

“That is too much, Rose. It is all the sport I have, to see the faces she makes when I plague her about Diggory. Besides, it serves her right for having such a temper.”

“She has not a good temper, poor thing!” said Rose; “but if you would only think how true and honest she is, how hard she toils, and how ill she fares, and yet how steadily she holds to us, you would surely not plague and torment her.”

Rose was interrupted by a great outcry, and in rushed Deborah, screaming out, “Lack-a-day! Mistress Rose! O Master Walter! what will become of us? The fight is lost, the King fled, and a whole regiment of red-coats burning and plundering the whole country. Our throats will be cut, every one of them!”

“You’ll have a chance of being a mark for all the musketeers in the Parliament army,” said Walter, who even then could not miss a piece of mischief.

“Joking now, Master Walter!” cried Deborah, very much shocked. “That is what I call downright sinful. I hope you’ll be made a mark of yourself, that I do.”

The children were running off to tell their mother, when Rose stopped them, and desired to know how Deborah had heard the tidings. It was from two little children from the village who had come to bring a present of some pigeons to my lady. Rose went herself to examine the children, but she could only learn that a packman had come into the village and brought the report that the King had been defeated, and had fled from the field. They knew no more, and Walter pronouncing it to be all a cock-and-bull story of some rascally prick-eared pedlar, declared he would go down to the village and enquire into the rights of it.

These were the saddest times of English history, when the wrong cause had been permitted for a time to triumph, and the true and rightful side was persecuted; and among those who endured affliction for the sake of their Church and their King, none suffered more, or more patiently, than Lady Woodley, or, as she was called in the old English fashion, Dame Mary Woodley, of Forest Lea.

When first the war broke out she was living happily in her pleasant home with her husband and children; but when King Charles raised his standard at Nottingham, all this comfort and happiness had to be given up. Sir Walter Woodley joined the royal army, and it soon became unsafe for his wife and children to remain at home, so that they were forced to go about with him, and suffer all the hardships of the sieges and battles. Lady Woodley was never strong, and her health was very much hurt by all she went through; she was almost always unwell, and if Rose, though then quite a child, had not shown care and sense beyond her years for the little ones, it would be hard to say what would have become of them.

Yet all she endured while dragging about her little babies through the country, with bad or insufficient food, uncomfortable lodgings, pain, weariness and anxiety, would have been as nothing but for the heavy sorrows that came upon her also. First she lost her only brother, Edmund Mowbray, and in the battle of Naseby her husband was killed; besides which there were the sorrows of the whole nation in seeing the King sold, insulted, misused, and finally slain, by his own subjects. After Sir Walter’s death, Lady Woodley went home with her five younger children to her father’s house at Forest Lea; for her husband’s estate, Edmund’s own inheritance, had been seized and sequestrated by the rebels. She was the heiress of Forest Lea since the loss of her brother, but the old Mr. Mowbray, her father, had given almost all his wealth for the royal cause, and had been oppressed by the exactions of the rebels, so that he had nothing to leave his daughter but the desolate old house and a few bare acres of land. For the shelter, however, Lady Woodley was very thankful; and there she lived with her children and a faithful servant, Deborah, whose family had always served the Mowbrays, and who would not desert their daughter now.

The neighbours in the village loved, and were sorry for, their lady, and used to send her little presents; there was a large garden in which Diggory Stokes, who had also served her father, raised vegetables for her use; the cow wandered in the deserted park, and so they contrived to find food; while all the work of the house was done by Rose and Deborah. Rose was her mother’s great comfort, nursing her, cheering her, taking care of the little ones, teaching them, working for them, and making light of all her exertions. Everyone in the village loved Rose Woodley, for everyone had in some way been helped or cheered by her. Her mother was only sometimes afraid she worked too hard, and would try her strength too much; but she was always bright and cheerful, and when the day’s work was done no one was more gay and lively and ready for play with the little ones.

Rose had more trial than anyone knew with Deborah. Deborah was as faithful as possible, and bore a great deal for the sake of her mistress, worked hard day and night, had little to eat and no wages, yet lived on with them rather than forsake her dear lady and the children. One thing, however, Deborah would not do, and that was to learn to rule her tongue and her temper. She did not know, nor do many excellent servants, how much trial and discomfort she gave to those she loved so earnestly, by her constant bursting out into hasty words whenever she was vexed—her grumbling about whatever she disliked, and her ill-judged scolding of the children. Servants in those days were allowed to speak more freely to their masters and mistresses than at present, so that Deborah had more opportunity of making such speeches, and it was Rose’s continual work to try to keep her temper from being fretted, or Lady Woodley from being teased with her complaints. Rose was very forbearing, and but for this there would have been little peace in the house.

Walter was thirteen, an age when it is not easy to keep boys in order, unless they will do so for themselves. Though a brave generous boy, he was often unruly and inconsiderate, apt not to obey, and to do what he knew to be unkind or wrong, just for the sake of present amusement. He was thus his mother’s great anxiety, for she knew that she was not fit either to teach or to restrain him, and she feared that his present wild disobedient ways might hurt his character for ever, and lead to dispositions which would in time swallow up all the good about him, and make him what he would now tremble to think of.

She used to talk of her anxieties to Doctor Bathurst, the good old clergyman who had been driven away from his parish, but used to come in secret to help, teach, and use his ministry for the faithful ones of his flock. He would tell her that while she did her best for her son, she must trust the rest to his Father above, and she might do so hopefully, since it had been in His own cause that the boy had been made fatherless. Then he would speak to Walter, showing him how wrong and how cruel were his overbearing, disobedient ways. Walter was grieved, and resolved to improve and become steadier, that he might be a comfort and blessing to his mother; but in his love of fun and mischief he was apt to forget himself, and then drove away what might have been in time repentance and improvement, by fancying he did no harm. Teasing Deborah served her right, he would tell himself, she was so ill-tempered and foolish; Diggory was a clod, and would do nothing without scolding; it was a good joke to tease Charlie; Eleanor was a vexatious little thing, and he would not be ordered by her; so he went his own way, and taught the merry chattering Lucy to be very nearly as bad as himself, neglected his duties, set a bad example, tormented a faithful servant, and seriously distressed his mother. Give him some great cause, he thought, and he would be the first and the best, bring back the King, protect his mother and sisters, and perform glorious deeds, such as would make his name be remembered for ever. Then it would be seen what he was worth; in the meantime he lived a dull life, with nothing to do, and he must have some fun. It did not signify if he was not particular about little things, they were women’s affairs, and all very well for Rose, but when some really important matter came, that would be his time for distinguishing himself.

In the meantime Charles II. had been invited to Scotland, and had brought with him, as an attendant, Edmund Woodley, the eldest son. As soon as he was known to have entered England, some of the loyal gentlemen of the neighbourhood of Forest Lea went to join the King, and among their followers went Farmer Ewins, who had fought bravely in the former war under Edmund Mowbray, several other of the men of the village, and lastly, Diggory Stokes, Lady Woodley’s serving man, who had lately shown symptoms of discontent with his place, and fancied that as a soldier he might fare better, make his fortune, and come home prosperously to marry his sweetheart, Deborah.

Walter ran down to the village at full speed. He first bent his steps towards the “Half-Moon,” the little public-house, where news was sure to be met with. As he came towards it, however, he heard the loud sound of a man’s voice going steadily on as if with some discourse. “Some preachment,” said he to himself: “they’ve got a thorough-going Roundhead, I can hear his twang through his nose! Shall I go in or not?”

While he was asking himself this question, an old peasant in a round frock came towards him.

“Hollo, Will!” shouted Walter, “what prick-eared rogue have you got there?”

“Hush, hush, Master Walter!” said the old man, taking off his hat very respectfully. “Best take care what you say, there be plenty of red-coats about. There’s one of them now preaching away in marvellous pied words. It is downright shocking to hear the Bible hollaed out after that sort, so I came away. Don’t you go nigh him, sir, ’specially with your hat set on in that—”

“Never mind my hat,” said Walter, impatiently, “it is no business of yours, and I’ll wear it as I please in spite of old Noll and all his crew.”

For his forefathers’ sake, and for the love of his mother and sister, the good village people bore with Walter’s haughtiness and discourtesy far more than was good for him, and the old man did not show how much he was hurt by his rough reception of his good advice. Walter was not reminded that he ought to rise up before the hoary head, and reverence the old man, and went on hastily, “But tell me, Will, what do you hear of the battle?”

“The battle, sir! why, they say it is lost. That’s what the fellow there is preaching about.”

“And where was it? Did you hear? Don’t you know?”

“Don’t be so hasty, don’t ye, sir!” said the old slow-spoken man, growing confused. “Where was it? At some town—some town, they said, but I don’t know rightly the name of it.”

“And the King? Who was it? Not Cromwell? Had Lord Derby joined?” cried Walter, hurrying on his questions so as to puzzle and confuse the old man more and more, till at last he grew angry at getting no explanation, and vowed it was no use to talk to such an old fool. At that moment a sound as of feet and horses came along the road. “’Tis the soldiers!” said Walter.

“Ay, sir, best get out of sight.”

Walter thought so too, and, springing over a hedge, ran off into a neighbouring wood, resolving to take a turn, and come back by the longer way to the house, so as to avoid the road. He walked across the wood, looking up at the ripening nuts, and now and then springing up to reach one, telling himself all the time that it was untrue, and that the King could not, and should not be defeated. The wood grew less thick after a time, and ended in low brushwood, upon an open common. Just as Walter was coming to this place, he saw an unusual sight: a man and a horse crossing the down. Slowly and wearily they came, the horse drooping its head and stumbling in its pace, as though worn out with fatigue, but he saw that it was a war-horse, and the saddle and other equipments were such as he well remembered in the royal army long ago. The rider wore buff coat, cuirass, gauntlets guarded with steel, sword, and pistols, and Walter’s first impulse was to avoid him; but on giving a second glance, he changed his mind, for though there was neither scarf, plume, nor any badge of party, the long locks, the set of the hat, and the general air of the soldier were not those of a rebel. He must be a cavalier, but, alas! far unlike the triumphant cavaliers whom Walter had hoped to receive, for he was covered with dust and blood, as if he had fought and ridden hard. Walter sprung forward to meet him, and saw that he was a young man, with dark eyes and hair, looking very pale and exhausted, and both he and his horse seemed hardly able to stir a step further.

“Young sir,” said the stranger, “what place is this? Am I near Forest Lea?”

A flash of joy crossed Walter. “Edmund! are you Edmund?” he exclaimed, colouring deeply, and looking up in his face with one quick glance, then casting down his eyes.

“And you are little Walter,” returned the cavalier, instantly dismounting, and flinging his arm around his brother; “why, what a fine fellow you are grown! How are my mother and all?”

“Well, quite well!” cried Walter, in a transport of joy. “Oh! how happy she will be! Come, make haste home!”

“Alas! I dare not as yet. I must not enter the house till nightfall, or I should bring danger on you all. Are there any troopers near?”

“Yes, the village is full of the rascals. But what has happened? It is not true that—” He could not bear to say the rest.

“Too true!” said Edmund, leading his tired horse within the shelter of the bushes. “It is all over with us!”

“The battle lost!” said Walter, in a stifled tone; and in all the bitterness of the first disappointment of his youth, he turned away, overcome by a gush of tears and sobs, stamping as he walked up and down, partly with the intensity of his grief, partly with shame at being seen by his brother, in tears.

“Had you set your heart on it so much?” said Edmund, kindly, pleased to see his young brother so ardent a loyalist. “Poor fellow! But at least the King was safe when I parted from him. Come, cheer up, Walter, the right will be uppermost some day or other.”

“But, oh, that battle! I had so longed to see old Noll get his deserts,” said Walter, “I made so sure. But how did it happen, Edmund?”

“I cannot tell you all now, Walter. You must find me some covert where I can be till night fall. The rebels are hot in pursuit of all the fugitives. I have ridden from Worcester by byroads day and night, and I am fairly spent. I must be off to France or Holland as soon as may be, for my life is not safe a moment here. Cromwell is bitterer than ever against all honest men, but I could not help coming this way, I so much longed to see my mother and all of you.”

“You are not wounded?” said Walter, anxiously.

“Nothing to speak of, only a sword-cut on my shoulder, by which I have lost more blood than convenient for such a journey.”

“Here, I’ll lead your horse; lean on me,” said Walter, alarmed at the faint, weary voice in which his brother spoke after the first excitement of the recognition. “I’ll show you what Lucy and I call our bower, where no one ever comes but ourselves. There you can rest till night.”

“And poor Bayard?” said Edmund.

“I think I could put him into the out-house in the field next to the copse, hide his trappings here, and get him provender from Ewins’s farm. Will that do?”

“Excellently. Poor Ewins!—that is a sad story. He fell, fighting bravely by my side, cut down in Sidbury Street in the last charge. Alas! these are evil days!”

“And Diggory Stokes, our own knave?”

“I know nothing of him after the first onset. Rogues and cowards enough were there. Think, Walter, of seeing his Majesty strive in vain to rally them, when the day might yet have been saved, and the traitors hung down their heads, and stood like blocks while he called on them rather to shoot him dead than let him live to see such a day!”

“Oh, had I but been there, to turn them all to shame!”

“There were a few, Walter; Lord Cleveland, Hamilton, Careless, Giffard, and a few more of us, charged down Sidbury Street, and broke into the ranks of the rebels, while the King had time to make off by S. Martin’s Gate. Oh, how I longed for a few more! But the King was saved so far; Careless, Giffard, and I came up with him again, and we parted at nightfall. Lord Derby’s counsel was that he should seek shelter at Boscobel, and he was to disguise himself, and go thither under Giffard’s guidance. Heaven guard him, whatever becomes of us!”

“Amen!” said Walter, earnestly. “And here we are. Here is Lucy’s bank of turf, and my throne, and here we will wait till the sun is down.”

It was a beautiful green slope, covered with soft grass, short thyme, and cushion-like moss, and overshadowed by a thick, dark yew-tree, shut in by brushwood on all sides, and forming just such a retreat as children love to call their own. Edmund threw himself down at full length on it, laid aside his hat, and passed his hand across his weary forehead. “How quiet!” said he; “but, hark! is that the bubbling of water?” he added, raising himself eagerly.

“Yes, here,” said Walter, showing him where, a little further off on the same slope, a little clear spring rose in a natural basin of red earth, fringed along the top with fresh green mosses.

“Delicious!” said the tired soldier, kneeling over the spring, scooping it up in his hand to drink, opening his collar, and bathing hands and face in the clear cool fountain, till his long black hair hung straight, saturated with wet.

“Now, Bayard, it is your turn,” and he patted the good steed as it sucked up the refreshing water, and Walter proceeded to release it from saddle and bridle. Edmund, meanwhile, stretched himself out on the mossy bank, asked a few questions about his mother, Rose, and the other children, but was too tired to say much, and presently fell sound asleep, while Walter sat by watching him, grieving for the battle lost, but proud and important in being the guardian of his brother’s safety, and delighting himself with the thought of bringing him home at night.

More was happening at home than Walter guessed. The time of his absence seemed very long, more especially when the twilight began to close in, and Lady Woodley began to fear that he might, with his rashness, have involved himself in some quarrel with the troopers in the village. Lady Woodley and her children had closed around the wood fire which had been lighted on the hearth at the approach of evening, and Rose was trying by the bad light to continue her darning of stockings, when a loud hasty knocking was heard at the door, and all, in a general vague impression of dread, started and drew together.

“Oh my lady!” cried Deborah, “don’t bid me go to the door, I could not if you offered me fifty gold caroluses! I had rather stand up to be a mark—”

“Then I will,” said Rose, advancing.

“No, no, Mistress Rose,” said Deborah, running forward. “Don’t I know what is fit for the like of you? You go opening the door to rogues and vagabonds, indeed!” and with these words she undrew the bolts and opened the door.

“Is this the way you keep us waiting?” said an impatient voice; and a tall youth, handsomely accoutred, advanced authoritatively into the room. “Prepare to—” but as he saw himself alone with women and children, and his eyes fell on the pale face, mourning dress, and graceful air of the lady of the house, he changed his tone, removed his hat, and said, “Your pardon, madam, I came to ask a night’s lodging for my father, who has been thrown from his horse, and badly bruised.”

“I cannot refuse you, sir,” said Lady Woodley, who instantly perceived that this was an officer of the Parliamentary force, and was only thankful to see that he was a gentleman, and enforced with courtesy a request which was in effect a command.

The youth turned and went out, while Lady Woodley hastily directed her daughters and servant. “Deborah, set the blue chamber in order; Rose, take the key of the oak press, Eleanor will help you to take out the holland sheets. Lucy, run down to old Margery, and bid her kill a couple of fowls for supper.”

As the girls obeyed there entered at the front door the young officer and a soldier, supporting between them an elderly man in the dress of an officer of rank. Lady Woodley, ready of course to give her help to any person who had suffered an injury, came forward to set a chair, and at the same moment she exclaimed, in a tone of recognition, “Mr. Enderby! I am grieved to see you so much hurt.”

“My Lady Woodley,” he returned, recognising her at the same time, as he seated himself in the chair, “I am sorry thus to have broken in on your ladyship, but my son, Sylvester, would have me halt here.”

“This gentleman is your son, then?” and a courteous greeting passed between Lady Woodley and young Sylvester Enderby, after which she again enquired after his father’s accident.

“No great matter,” was the reply; “a blow on the head, and a twist of the knee, that is all. Thanks to a stumbling horse, wearied out with work, I have little mind to—the pursuit of this poor young man.”

“Not the King?” exclaimed Lady Woodley, breathless with alarm.

It was with no apparent satisfaction that the rebel colonel replied, “Even so, madam. Cromwell’s fortune has not forsaken him; he has driven the Scots and their allies out of Worcester.”

Lady Woodley was too much accustomed to evil tidings to be as much overcome by them as her young son had been; she only turned somewhat paler, and asked, “The King lives?”

“He was last seen on Worcester bridge. Troops are sent to every port whence he might attempt an escape.”

“May the God of his father protect him,” said the lady, fervently. “And my son?” she added, faintly, scarcely daring to ask the question.

“Safe, I hope,” replied the colonel. “I saw him, and I could have thought him my dear old friend himself, as he joined Charles in his last desperate attempt to rally his forces, and then charged down Sidbury Street with a few bold spirits who were resolved to cover their master’s retreat. He is not among the slain; he was not a prisoner when I left the headquarters. I trust he may have escaped, for Cromwell is fearfully incensed against your party.”

Colonel Enderby was interrupted by Lucy’s running in calling out, “Mother, mother! there are no fowls but Partlet and the sitting hen, and the old cock, and I won’t have my dear old Partlet killed to be eaten by wicked Roundheads.”

“Come here, my little lady,” said the colonel, holding out his hand, amused by her vehemence.

“I won’t speak to a Roundhead,” returned Lucy, with a droll air of petulance, pleased at being courted.

Her mother spoke gravely. “You forget yourself, Lucy. This is Mr. Enderby, a friend of your dear father.”

Lucy’s cheeks glowed, and she looked down as she gave her hand to the colonel; but as he spoke kindly to her, her forward spirit revived, and she returned to the charge.

“You won’t have Partlet killed?”

Her mother would have silenced her, but the colonel smiled and said, “No, no, little lady; I would rather go without supper than let one feather of Dame Partlet be touched.”

“Nay, you need not do that either, sir,” said the little chatter-box, confidentially, “for we are to have a pie made of little Jenny’s pigeons; and I’ll tell you what, sir, no one makes raised crust half so well as sister Rose.”

Lady Woodley was not sorry to stop the current of her little girl’s communications by despatching her on another message, and asking Colonel Enderby whether he would not prefer taking a little rest in his room before supper-time, offering, at the same time all the remedies for bruises and wounds that every good housekeeper of the time was sure to possess.

She had a real regard for Mr. Enderby, who had been a great friend of her husband before the unhappy divisions of the period arrayed them on opposite sides, and even then, though true friendship could not last, a kindly feeling had always existed.

Mr. Enderby was a conscientious man, but those were difficult times; and he had regarded loyalty to the King less than what he considered the rights of the people. He had been an admirer of Hampden and his principles, and had taken up arms on the same side, becoming a rebel on political, not on religious, grounds. When, as time went on, the evils of the rebellion developed themselves more fully, he was already high in command, and so involved with his own party that he had not the resolution requisite for a change of course and renunciation of his associates. He would willingly have come to terms with the King, and was earnest in the attempt at the time of the conferences at Hampden Court. He strongly disapproved of the usurpation of power by the army, and was struck with horror, grief, and dismay, at the execution of King Charles; but still he would not, or fancied that he could not, separate himself from the cause of the Parliament, and continued in their service, following Cromwell to Scotland, and fighting at Worcester on the rebel side, disliking Cromwell all the time, and with a certain inclination to the young King, and desire to see the old constitution restored.

He was just one of those men who cause such great evil by giving a sort of respectability to the wrong cause, “following a multitude to do evil,” and doubtless bringing a fearful responsibility on their own heads; yet with many good qualities and excellent principles, that make those on the right side have a certain esteem for them, and grieve to see them thus perverted.

Lady Woodley, who knew him well, though sorry to have a rebel in her house at such a time, was sure that in him she had a kind and considerate guest, who would do his utmost to protect her and her children.

On his side, Colonel Enderby was much grieved and shocked at the pale, altered looks of the fair young bride he remembered, as well as the evidences of poverty throughout her house, and perhaps he had a secret wish that he was as well assured as his friend, Sir Walter, that his blood had been shed for the maintenance of the right.

Rose Woodley ran up and down indefatigably, preparing everything for the accommodation of the guests, smoothing down Deborah’s petulance, and keeping her mother from over-exertion or anxiety. Much contrivance was indeed required, for besides the colonel and his son, two soldiers had to be lodged, and four horses, which, to the consternation of old Margery, seemed likely to devour the cow’s winter store of hay, while the troopers grumbled at the desolate, half-ruined, empty stables, and at the want of corn.

Rose had to look to everything; to provide blankets from the bed of the two little girls, send Eleanor to sleep with her mother, and take Lucy to her own room; despatch them on messages to the nearest cottage to borrow some eggs, and to gather vegetables in the garden, whilst she herself made the pigeon pie with the standing crust, much wishing that the soldiers were out of the way. It was a pretty thing to see her in her white apron, with her neat dexterous fingers, and nimble quiet step, doing everything in so short a time, and so well, without the least bustle.

She was at length in the hall, laying the white home-spun, home-bleached cloth, and setting the trenchers (all the Mowbray plate had long ago gone in the King’s service), wondering anxiously, meantime, what could have become of Walter, with many secret and painful misgivings, though she had been striving to persuade her mother that he was only absent on some freak of his own.

Presently the door which led to the garden was opened, and to her great joy Walter put his head into the room.

“O Walter,” she exclaimed, “the battle is lost! but Edmund and the King have both escaped.”

“Say you so?” said Walter, smiling. “Here is a gentleman who can give you some news of Edmund.”

At the same moment Rose saw her beloved eldest brother enter the room. It would be hard to say which was her first thought, joy or dismay—she had no time to ask herself. Quick as lightning she darted to the door leading to the staircase, bolted it, threw the bar across the fastening of the front entrance, and then, flying to her brother, clung fast round his neck, kissed him on each cheek, and felt his ardent kiss on her brow, as she exclaimed in a frightened whisper, “You must not stay here: there are troopers in the house!”

“Troopers!—quartered on us?” cried Walter.

Rose hastily explained, trembling lest anyone should attempt to enter. Walter paced up and down in despair, vowing that it was a trick to get a spy into the house. Edmund sat down in the large arm-chair with a calm resolute look, saying, “I must surrender, then. Neither I nor my horse can go further without rest. I will yield as a prisoner of war, and well that it is to a man of honour.”

“Oh no, no!” cried Rose: “he says Cromwell treats his prisoners as rebels. It would be certain death!”

“What news of the King?” asked Edmund, anxiously.

“Not seen since the flight? but—”

“And Lord Derby, Wilmot—”

“I cannot tell, I heard no names,” said Rose, “only that the enemy’s cruelties are worse than ever.”

Walter stood with his back against the table, gazing at his brother and sister in mute consternation.

“I know!” cried Rose, suddenly: “the out-house in the upper field. No one ever goes up into the loft but ourselves. You know, Walter, where Eleanor found the kittens. Go thither, I will bring Edmund food at night. Oh, consent, Edmund!”

“It will do! it will do!” cried Walter.

“Very well, it may spare my mother,” said Edmund; and as footsteps and voices were heard on the stairs, the two brothers hurried off without another word, while Rose, trying to conceal her agitation, undid the door, and admitted her two little sisters, who were asking if they had not heard Walter’s voice.

She scarcely attended to them, but, bounding upstairs to her mother’s room, flung her arms round her neck, and poured into her ear her precious secret. The tremour, the joy, the fears, the tears, the throbbings of the heart, and earnest prayers, may well be imagined, crowded by the mother and daughter into those few minutes. The plan was quickly arranged. They feared to trust even Deborah; so that the only way that they could provide the food that Edmund so much needed was by Rose and Walter attempting to save all they could at supper, and Rose could steal out when everyone was gone to rest, and carry it to him. Lady Woodley was bent on herself going to her son that night; but Rose prevailed on her to lay aside the intention, as it would have been fatal, in her weak state of health, for her to expose herself to the chills of an autumn night, and, what was with her a much more conclusive reason, Rose was much more likely to be able to slip out unobserved. Rose had an opportunity of explaining all this to Walter, and imploring him to be cautious, before the colonel and his son came down, and the whole party assembled round the supper-table.

Lady Woodley had the eggs and bacon before her; Walter insisted on undertaking the carving of the pigeon-pie, and looked considerably affronted when young Sylvester Enderby offered to take the office, as a more experienced carver. Poor Rose, how her heart beat at every word and look, and how hard she strove to seem perfectly at her ease and unconscious! Walter was in a fume of anxiety and vexation, and could hardly control himself so far as to speak civilly to either of the guests, so that he was no less a cause of fear to his mother and sister than the children, who were unconscious how much depended on discretion.

Young Sylvester Enderby was a fine young man of eighteen, very good-natured, and not at all like a Puritan in appearance or manner. He had hardly yet begun to think for himself, and was merely obeying his father in joining the army with him, without questioning whether it was the right cause or not. He was a kind elder brother at home, and here he was ready to be pleased with the children of the house.

Lucy was a high-spirited talkative child, very little used to seeing strangers, and perhaps hardly reined in enough, for her poor mother’s weak health had interfered with strict discipline; and as this evening Walter and Rose were both grave and serious under their anxieties, Lucy was less restrained even than usual.

She was a pretty creature, with bright blue eyes, and an arch expression, all the droller under her prim round cap; and Sylvester was a good deal amused with her pert bold little nods and airs. He paid a good deal of attention to her, and she in return grew more forward and chattering. It is what little girls will sometimes do under the pleasure and excitement of the notice of gentlemen, and it makes their friends very uneasy, since the only excuse they can have is in being very little, and it shows a most undesirable want of self-command and love of attention.

In addition to this feeling, Lady Woodley dreaded every word that was spoken, lest it should lead to suspicion, for though she was sure Mr. Enderby would not willingly apprehend her son, yet she could not tell what he might consider his duty to his employers; besides, there were the two soldiers to observe and report, and the discovery that Edmund was at hand might lead to frightful consequences. She tried to converse composedly with him on his family and the old neighbourhood where they had both lived, often interrupting herself to send a look or word of warning to the lower end of the table; but Lucy and Charles were too wild to see or heed her, and grew more and more unrestrained, till at last, to the dismay of her mother, brother, and sister, Charles’ voice was heard so loud as to attract everyone’s notice, in a shout of wonder and complaint, “Mother, mother, look! Rose has gobbled up a whole pigeon to her own share!”

Rose could not keep herself from blushing violently, as she whispered reprovingly that he must not be rude. Lucy did not mend the matter by saying with an impertinent nod, “Rose does not like to be found out.”

“Children,” said Lady Woodley, gravely, “I shall send you away if you do not behave discreetly.”

“But, mother, Rose is greedy,” said Lucy.

“Hold your tongues, little mischief makers!” burst out Walter, who had been boiling over with anxiety and indignation the whole time.

“Walter is cross now,” said Lucy, pleased to have produced a sensation, and to have shocked Eleanor, who sat all the time as good, demure, and grave, as if she had been forty years old.

“Pray excuse these children,” said Lady Woodley, trying to hide her anxiety under cover of displeasure at them; “no doubt Mrs. Enderby keeps much better order at home. Lucy, Charles, silence at once. Walter, is there no wine?”

“If there is, it is too good for rebels,” muttered Walter to himself, as he rose. “Light me, Deborah, and I’ll see.”

“La! Master Walter,” whispered Deborah, “you know there is nothing but the dregs of the old cask of Malmsey, that was drunk up at the old squire’s burying.”

“Hush, hush, Deb,” returned the boy; “fill it up with water, and it will be quite good enough for those who won’t drink the King’s health.”

Deborah gave a half-puzzled smile. “Ye’re a madcap, Master Walter! But sure, Sir, the spirit of a wolf must have possessed Mistress Rose—she that eats no supper at all, in general! D’ye think it is wearying about Master Edmund that gives her a craving?”

It might be dangerous, but Walter was so much diverted, that he could not help saying, “I have no doubt it is on his account.”

“I know,” said Deborah, “that I get so faint at heart that I am forced to be taking something all day long to keep about at all!”

By this time they were re-entering the hall, when there was a sound from the kitchen as of someone calling. Deborah instantly turned, screaming out joyfully, “Bless me! is it you?” and though out of sight, her voice was still heard in its high notes of joy. “You good-for-nothing rogue! are you turned up again like a bad tester, staring into the kitchen like a great oaf, as you be?”

There was a general laugh, and Eleanor said, “That must be Diggory.”

“A poor country clown,” said Lady Woodley, “whom we sent to join my son’s troop. I hope he is in no danger.”

“Oh no,” said Mr. Enderby; “he has only to return to his plough.”

“Hollo there!” shouted Walter. “Come in, Diggory, and show yourself.”

In came Diggory, an awkward thick-set fellow, with a shock head of hair, high leathern gaiters, and a buff belt over his rough leathern jerkin. There he stood, pulling his forelock, and looking sheepish.

“Come in, Diggory,” said his mistress; “I am glad to see you safe. You need not be afraid of these gentlemen. Where are the rest?”

“Slain, every man of them, an’t please your ladyship.”

“And your master, Mr. Woodley?”

“Down, too, an’t please your ladyship.”

Lucy screamed aloud; Eleanor ran to her mother, and hid her face in her lap; Charles sat staring, with great round frightened eyes. Very distressing it was to be obliged to leave the poor children in such grief and alarm, when it was plain all the time that Diggory was an arrant coward, who had fancied more deaths and dangers than were real, and was describing more than he had even thought he beheld, in order to make himself into a hero instead of a runaway. Moreover, Lady Woodley and Rose had to put on a show of grief, lest they should betray that they were better informed; and they were in agonies lest Walter’s fury at the falsehoods should be as apparent to their guests as it was to themselves.

“Are you sure of what you say, Diggory?” said Lady Woodley.

“Sure as that I stand here, my lady. There was sword and shot and smoke all round. I stood it all till Farmer Ewins was cut down a-one-side of me, ma’am, and Master Edmund, more’s the pity, with his brains scattered here and there on the banks of the river.”

There was another cry among the children, and Walter made such a violent gesture, that Rose, covering her face with her handkerchief, whispered to him, “Walter dear, take care.” Walter relieved his mind by returning, “Oh that I could cudgel the rogue soundly!”

At the same time Colonel Enderby turned to their mother, saying, “Take comfort, madam, this fellow’s tale carries discredit on the face of it. Let me examine him, with your permission. Where did you last see your master?”

“I know none of your places, sir,” answered Diggory, sullenly.

Colonel Enderby spoke sternly and peremptorily. “In the town, or in the fields? Answer me that, sirrah. In the field on the bank of the river?”

“Ay.”

“There you left your ranks, you rogue; that was the way you lost sight of your master!” said the colonel. Then, turning to Lady Woodley, as Diggory slunk off, “Your ladyship need not be alarmed. An hour after the encounter, in which he pretends to have seen your son slain, I saw him in full health and soundness.”

“A cowardly villain!” cried Walter, delighted to let out some of his indignation. “I knew he was not speaking a word of truth.”

The children cheered up in a moment; but Lady Woodley was not sorry to make this agitating scene an excuse for retiring with all her children. Lucy and Eleanor were quite comforted, and convinced that Edmund must be safe; but poor little Charlie had been so dreadfully frightened by the horrors of Diggory’s description, that after Rose had put him to bed he kept on starting up in his sleep, half waking, and sobbing about brother Edmund’s brains.

Rose was obliged to go to him and soothe him. She longed to assure the poor little fellow that dear Edmund was perfectly safe, well, and near at hand; but the secret was too important to be trusted to one so young, so she could only coax and comfort him, and tell him they all thought it was not true, and Edmund would come back again.

“Sister,” said Charlie, “may I say my prayers again for him?”

“Yes, do, dear Charlie,” said Rose; “and say a prayer for King Charles too, that he may be safe from the wicked man.”

So little Charlie knelt by Rose, with his hands joined, and his little bare legs folded together, and said his prayer: and did not his sister’s heart go with him? Then she kissed him, covered him up warmly, and repeated to him in her soft voice the ninety-first Psalm: “Whoso dwelleth under the defence of the Most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty.”

By the time it was ended, the little boy was fast asleep, and the faithful loyal girl felt her failing heart cheered and strengthened for whatever might be before her, sure that she, her mother, her brother, and her King, were under the shadow of the Almighty wings.

In a very strong fit of restlessness did little Mistress Lucy Woodley go to bed in Rose’s room that night. She was quite comforted on Edmund’s account, for she had discernment enough to see that her mother and sister did not believe Diggory’s dreadful narration; and she had been so unsettled and excited by Mr. Sylvester Enderby’s notice, and by the way in which she had allowed her high spirits to get the better of her discretion, as well as by the sudden change from terror to joy, that when first she went to Rose’s room she could not attend to her prayers, and next she could not go to sleep.

Perhaps the being in a different apartment from usual, and the missing her accustomed sleeping companion, Eleanor, had something to do with it, for little Eleanor had a gravity and steadiness about her that was very apt to compose and quiet her in her idlest moods. To-night she lay broad awake, tumbling about on the very hard mattress, stuffed with chaff, wondering how Rose could bear to sleep on it, trying to guess how there could be room for both when her sister came to bed, and nevertheless in a great fidget for her to come. She listened to the howling and moaning of the wind, the creaking of the doors, and the rattling of the boards with which Rose had stopped up the broken panes of her lattice; she rolled from side to side, fancied odd shapes in the dark, and grew so restless and anxious for Rose’s coming that she was just ready to jump out of bed and go in the passage to call her when Rose came into the room.

“O Rose, what a time you have been!”

It was no satisfaction to Rose to find the curious little chatter-box so wide awake at this very inconvenient time, but she did not lose her patience, and answered that she had been first with Charlie, and then with their mother.

“And now I hope you are coming to bed. I can’t go to sleep without you.”

“Oh, but indeed you must, Lucy dear, for I shall not be ready this long time. Look, here is a great rent in Walter’s coat, which I must mend, or he won’t be fit to be seen to-morrow.”

“What shall we have for dinner to-morrow, Rose? What made you eat so much supper to-night?”

“I’ll tell you what, Lucy, I am not going to talk to you, or you will lie awake all night, and that will be very bad for you. I shall put my candle out of your sight, and say some Psalms, but I cannot talk.”

So Rose began, and, wakeful as Lucy was, she found the low sweet tones lulled her a little. But she did not like this; she had a perverse intention of staying awake till Rose got into bed, so instead of attending to the holy words, she pinched herself, and pulled herself, and kept her eyes staring open, gazing at the flickering shadows cast by the dim home-made rush candle.

She went to sleep for a moment, then started into wakefulness again; Rose had ceased to repeat her Psalms aloud, but was still at her needlework; another doze, another waking. There was some hope of Rose now, for she was kneeling down to say her prayers. Lucy thought they lasted very long, and at her next waking she was just in time to hear the latch of the door closing, and find herself left in darkness. Rose was not in bed, did not answer when she called. Oh, she must be gone to take Walter’s coat back to his room. But surely she might have done that in one moment; and how long she was staying! Lucy could bear it no longer, or rather she did not try to bear it, for she was an impetuous, self-willed child, without much control over herself. She jumped out of bed, and stole to the door. A light was just disappearing on the ceiling, as if someone was carrying a candle down stairs; what could it mean? Lucy scampered, pit-pat, with her bare feet along the passage, and came to the top of the stairs in time to peep over and discover Rose silently opening the door of the hall, a large dark cloak hung over her arm, and her head and neck covered by her black silk hood and a thick woollen kerchief, as if she was going out.

Lucy’s curiosity knew no bounds. She would not call, for fear she should be sent back to bed, but she was determined to see what her sister could possibly be about. Down the cold stone steps pattered she, and luckily, as she thought, Rose, probably to avoid noise, had only shut to the door, so that the little inquisitive maiden had a chink to peep through, and beheld Rose at a certain oaken corner-cupboard, whence she took out a napkin, and in it she folded what Lucy recognised as the very same three-cornered segment of pie-crust, containing the pigeon that she had last night been accused of devouring. She placed it in a basket, and then proceeded to take a lantern from the cupboard, put in her rushlight, and, thus prepared, advanced to the garden-door, softly opened it, and disappeared.

Lucy, in an extremity of amazement, came forward. The wind howled in moaning gusts, and the rain dashed against the windows; Lucy was chilly and frightened. The fire was not out, and gave a dim light, and she crept towards the window, but a sudden terror came over her; she dashed back, looked again, heard another gust of wind, fell into another panic, rushed back to the stairs, and never stopped till she had tumbled into bed, her teeth chattering, shivering from head to foot with fright and cold, rolled herself up tight in the bed-clothes, and, after suffering excessively from terror and chill, fell sound asleep without seeing her sister return.

Causeless fears pursue those who are not in the right path, and turn from what alone can give them confidence. A sense of protection supports those who walk in innocence, though their way may seem surrounded with perils; and thus, while Lucy trembled in an agony of fright in her warm bed, Rose walked forth with a firm and fearless step through the dark gusty night, heedless of the rain that pattered round her, and the wild wind that snatched at her cloak and gown, and flapped her hood into her eyes.

She was not afraid of fancied terrors, and real perils and anxieties were at this moment lost in the bounding of her young heart at the thought of seeing, touching, speaking to her brother, her dear Edmund. She had been eleven years old when they last had parted, the morning of the battle of Naseby, and he was five years older; but they had always been very happy and fond companions and playfellows as long as she could remember, and she alone had been on anything like an equality with him, or missed him with a feeling of personal loss, that had been increased by the death of her elder sister, Mary.

Quickly, and concealing her light as much as possible, she walked down the damp ash-strewn paths of the kitchen-garden, and came out into the overgrown and neglected shrubbery, or pleasance, where the long wet-laden shoots came beating in her face, and now and then seeming to hold her back, and strange rustlings were heard that would have frightened a maiden of a less stout and earnest heart. Her anxiety was lest she should be confused by the unwonted aspect of things in the dark, and miss the path; and very, very long did it seem, while her light would only show her leaves glistening with wet. At last she gained a clearer space, the border of a field: something dark rose before her, she knew the outline of the shed, and entered the lower part. It was meant for a cart-shed, with a loft above for hay or straw; but the cart had been lost or broken, and there was only a heap of rubbish in the corner, by which the children were wont to climb up to inspect their kittens. Here Rose was for a moment startled by a glare close to her of what looked like two fiery lamps in the darkness, but the next instant a long, low, growling sound explained it, and the tabby stripes of the cat quickly darted across her lantern’s range of light. She heard a slight rustling above, and ventured to call, in a low whisper, “Edmund.”

“Is that you, Walter?” and as Rose proceeded to mount the pile of rubbish, his pale and haggard face looked down at her.

“What? Rose herself! I did not think you would have come on such a night as this. Can you come up? Shall I help you?”

“Thank you. Take the lantern first—take care. There. Now the basket and the cloak.” And this done, with Edmund’s hand, Rose scrambled up into the loft. It was only the height of the roof, and there was not room, even in the middle, to stand upright; the rain soaked through the old thatch, the floor was of rough boards, and there was but very little of the hay that had served as a bed for the kittens.

“O Edmund, this is a wretched place!” exclaimed Rose, as, crouching by his side, one hand in his, and the other round his neck, she gazed around.

“Better than a prison,” he answered. “I only wish I knew that others were in as good a one. And you—why, Rose, how you are altered; you are my young lady now! And how does my dear mother?”

“Pretty well. I could hardly prevail on her not to come here to-night; but it would have been too much, she is so weak, and takes cold so soon. But, Edmund, how pale you are, how weary! Have you slept? I fear not, on these hard boards—your wound, too.”

“It hardly deserves such a dignified name as a wound,” said Edmund. “I am more hungry than aught else; I could have slept but for hunger, and now”—as he spoke he was opening the basket—“I shall be lodged better, I fear, than a king, with that famous cloak. What a notable piece of pasty! Well done, Rose! Are you housewife? Store of candles, too. This is noble!”

“How hungry you must be! How long is it since you have eaten?”

“Grey sent his servant into a village to buy some bread and cheese; we divided it when we parted, and it lasted me until this morning. Since then I have fasted.”

“Dear brother, I wish I could do more for you; but till Mr. Enderby goes, I cannot, for the soldiers are about the kitchen, and our maid, Deborah, talks too much to be trustworthy, though she is thoroughly faithful.”

“This is excellent fare,” said Edmund, eating with great relish. “And now tell me of yourselves. My mother is feeble and unwell, you say?”

“Never strong, but tolerably well at present.”

“So Walter said. By the way, Walter is a fine spirited fellow. I should like to have him with me if we take another African voyage.”

“He would like nothing better, poor fellow. But what strange things you have seen and done since we met! How little we thought that morning that it would be six years before we should sit side by side again! And Prince Rupert is kind to you?”

“He treats me like a son or brother: never was man kinder,” said Edmund, warmly. “But the children? I must see them before I depart. Little Lucy, is she as bold and pert as she was as a young child?”

“Little changed,” said Rose, smiling, and telling her brother the adventures at the dinner.

As cheerfully as might be they talked till Edmund had finished his meal, and then Rose begged him to let her examine and bind up the wound. It was a sword-cut on the right shoulder, and, though not very deep, had become stiff and painful from neglect, and had soaked his sleeve deeply with blood. Rose’s dexterous fingers applied the salve and linen she had brought, and she promised that at her next visit she would bring him some clean clothes, which was what he said he most wished for. Then she arranged the large horseman’s cloak, the hay, and his own mantle, so well as to form, he said, the most luxurious resting place he had seen since he left Dunbar; and rolled up in this he lay, his head supported on his hand, talking earnestly with her on the measures next to be taken for his safety, and on the state of the family. He must be hidden there till the chase was a little slackened, and then escape, by Bosham or some other port, to the royal fleet, which was hovering on the coast. Money, however—how was he to get a passage without it?

“The Prince, at parting—heaven knows he has little enough himself—gave me twenty gold crowns, which he said was my share of prize-money for our captures,” said Edmund, “but this is the last of them.”

“And I don’t know how we can get any,” said Rose. “We never see money. Our tenants, if they pay at all, pay in kind—a side of bacon, or a sack of corn; they are very good, poor people, and love our mother heartily, I do believe. I wish I knew what was to be done.”

“Time will show,” said Edmund. “I have been in as bad a case as this ere now, and it is something to be near you all again. So you like this place, do you? As well as our own home?”

Rose shook her head, and tears sprang into her eyes. “Oh no, Edmund; I try to think it home, and the children feel it so, but it is not like Woodley. Do you remember the dear old oak-tree, with the branches that came down so low, where you used to swing Mary and me?”

“And the high branch where I used to watch for my father coming home from the justice-meeting. And the meadow where the hounds killed the fox that had baffled them so long! Do you hear anything of the place now, Rose?”

“Mr. Enderby told us something,” said Rose, sadly. “You know who has got it, Edmund?”

“Who?

“That Master Priggins, who was once justices’ clerk.”

“Ha!” cried Edmund. “That pettifogging scrivener in my father’s house!—in my ancestors’ house! A rogue that ought to have been branded a dozen years ago! I could have stood anything but that! Pretty work he is making there, I suppose! Go on, Rose.”

“O Edmund, you know it is but what the King himself has to bear.”

“Neighbour’s fare! as you say,” replied Edmund, with a short dry laugh. “Poverty and wandering I could bear; peril is what any brave man naturally seeks; the acres that have been ours for centuries could not go in a better cause; but to hear of a rascal such as that in my father’s place is enough to drive one mad with rage! Come, what has he been doing? How has he used the poor people?”

“He turned out old Davy and Madge at once from keeping the house, but Mr. Enderby took them in, and gave them a cottage.”

“I wonder what unlucky fate possessed that Enderby to take the wrong side! Well?”

“He could not tell us much of the place, for he cannot endure Master Priggins, and Master Sylvester laughs at his Puritanical manner; but he says—O Edmund—that the fish-ponds are filled up—those dear old fish-ponds where the water-lilies used to blow, and you once pulled me out of the water.”

“Ay, ay! we shall not know it again if ever our turn comes, and we enjoy our own again. But it is of no use to think about such matters.”

“No; we must be thankful that we have a home at all, and are not like so many, who are actually come to beggary, like poor Mrs. Forde. You remember her, our old clergyman’s widow. He died on board ship, and she was sent for by her cousin, who promised her a home; but she had no money, and was forced to walk all the way, with her two little boys, getting a lodging at night from any loyal family who would shelter her for the love of heaven. My mother wept when she saw how sadly she was changed; we kept her with us a week to rest her, and when she went she had our last gold carolus, little guessing, poor soul, that it was our last. Then, when she was gone, my mother called us all round her, and gave thanks that she could still give us shelter and daily bread.”

“There is a Judge above!” exclaimed Edmund; “yet sometimes it is hard to believe, when we see such a state of things here below!”

“Dr. Bathurst tells us to think it will all be right in the other world, even if we do have to see the evil prosper here,” said Rose, gravely. “The sufferings will all turn to glory, just as they did with our blessed King, out of sight.”

Edmund sat thoughtful. “If our people abroad would but hope and trust and bear as you do here, Rose. But I had best not talk of these things, only your patience makes me feel how deficient in it we are, who have not a tithe to bear of what you have at home. Are you moving to go? Must you?”

“I fear so, dear brother; the light seems to be beginning to dawn, and if Lucy wakes and misses me—Is your shoulder comfortable?”

“I was never more comfortable in my life. My loving duty to my dear mother. Farewell, you, sweet Rose.”

“Farewell, dear Edmund. Perhaps Walter may manage to visit you, but do not reckon on it.”

The vigils of the night had been as unwonted for Lucy as for her sister, and she slept soundly till Rose was already up and dressed. Her first reflection was on the strange sights she had seen, followed by a doubt whether they were real, or only a dream; but she was certain it was no such thing; she recollected too well the chill of the stone to her feet, and the sound of the blasts of wind. She wondered over it, wished to make out the cause, but decided that she should only be scolded for peeping, and she had better keep her own counsel.

That Lucy should keep silence when she thought she knew more than other people was, however, by no means to be expected; and though she would say not a word to her mother or Rose, of whom she was afraid, she was quite ready to make the most of her knowledge with Eleanor.

When she came down stairs she found Walter, with his elbows on the table and his book before him, learning the task which his mother required of him every day; Eleanor had just come in with her lapfull of the still lingering flowers, and called her to help to make them up into nosegays.

Lucy came and sat down by her on the floor, but paid little attention to the flowers, so intent was she on showing her knowledge.

“Ah! you don’t know what I have seen.”

“I dare say it is only some nonsense,” said Eleanor, gravely, for she was rather apt to plume herself on being steadier than her elder sister.

“It is no nonsense,” said Lucy. “I know what I know.”

Before Eleanor had time to answer this speech, the mystery of which was enhanced by a knowing little nod of the head, young Mr. Enderby made his appearance in the hall, with a civil good-morning to Walter, which the boy hardly deigned to acknowledge by a gruff reply and little nod, and then going on to the little girls, renewed with them yesterday’s war of words. “Weaving posies, little ladies?”

“Not for rebels,” replied Lucy, pertly.

“May I not have one poor daisy?”

“Not one; the daisy is a royal flower.”

“If I take one?”

“Rebels take what they can’t get fairly,” said Lucy, with the smartness of a forward child; and Sylvester, laughing heartily, continued, “What would General Cromwell say to such a nest of little malignants?”

“That is an ugly name,” said Eleanor.

“Quite as pretty as Roundhead.”

“Yes, but we don’t deserve it.”

“Not when you make that pretty face so sour?”

“Ah!” interposed Lucy, “she is sour because I won’t tell her my secret of the pie.”

“Oh, what?” said Eleanor.

“Now I have you!” cried Lucy, delighted. “I know what became of the pigeon pie.”

In extreme alarm and anger, Walter turned round as he caught these words. “Lucy, naughty child!” he began, in a voice of thunder; then, recollecting the danger of exciting further suspicion, he stammered, “what—what—what—are you doing here? Go along to mother.”

Lucy rubbed her fingers into her eyes, and answered sharply, in a pettish tone, that she was doing no harm. Eleanor, in amazement, asked what could be the matter.

“Intolerable!” exclaimed Walter. “So many girls always in the way?”

Sylvester Enderby could not help smiling, as he asked, “Is that all you have to complain of?”

“I could complain of something much worse,” muttered Walter. “Get away, Lucy?”

“I won’t at your bidding, sir.”

To Walter’s great relief, Rose entered at that moment, and all was smooth and quiet; Lucy became silent, and the conversation was kept up in safe terms between Rose and the young officer. The colonel, it appeared, was so much better that he intended to leave Forest Lea that very day; and it was not long before he came down, and presently afterwards Lady Woodley, looking very pale and exhausted, for her anxieties had kept her awake all night.

After a breakfast on bread, cheese, rashers of bacon, and beer, the horses were brought to the door, and the colonel took his leave of Lady Woodley, thanking her much for her hospitality.

“I wish it had been better worth accepting,” said she.

“I wish it had, though not for my own sake,” said the colonel. “I wish you would allow me to attempt something in your favour. One thing, perhaps, you will deign to accept. Every royalist house, especially those belonging to persons engaged at Worcester, is liable to be searched, and to have soldiers quartered on them, to prevent fugitives from being harboured there. I will send Sylvester at once to obtain a protection for you, which may prevent you from being thus disturbed.”

“That will be a kindness, indeed,” said Lady Woodley, hardly able to restrain the eagerness with which she heard the offer made, that gave the best hope of saving her son. She was not certain that the colonel had not some suspicion of the true state of the case, and would not take notice, unwilling to ruin the son of his friend, and at the same time reluctant to fail in his duty to his employers.

He soon departed; Mistress Lucy’s farewell to Sylvester being thus: “Good-bye, Mr. Roundhead, rebel, crop-eared traitor.” At which Sylvester and his father turned and laughed, and their two soldiers looked very much astonished.

Lady Woodley called Lucy at once, and spoke to her seriously on her forwardness and impertinence. “I could tell you, Lucy, that it is not like a young lady, but I must tell you more, it is not like a young Christian maiden. Do you remember the text that I gave you to learn a little while ago—the ornament fit for a woman?”

Lucy hung her head, and with tears filling her eyes, as her mother prompted her continually, repeated the text in a low mumbling voice, half crying: “Whose adorning, let it not be the putting on of gold, or the plaiting of hair, or the putting on of apparel, but let it be the hidden man of the heart, even the ornament of a meek and quiet spirit, which is in the sight of God of great price.”

“And does my little Lucy think she showed that ornament when she pushed herself forward to talk idle nonsense, and make herself be looked at and taken notice of?”

Lucy put her finger in her mouth; she did not like to be scolded, as she called it, gentle as her mother was, and she would not open her mind to take in the kind reproof.

Lady Woodley took the old black-covered Bible, and finding two of the verses in S. James about the government of the tongue, desired Lucy to learn them by heart before she went out of the house; and the little girl sat down with them in the window-seat, in a cross impatient mood, very unfit for learning those sacred words. “She had done no harm,” she thought; “she could not help it if the young gentleman would talk to her!”

So there she sat, with the Bible in her lap, alone, for Lady Woodley was so harassed and unwell, in consequence of her anxieties, that Rose had persuaded her to go and lie down on her bed, since it would be better for her not to try to see Edmund till the promised protection had arrived, lest suspicion should be excited. Rose was busy about her household affairs; Eleanor, a handy little person, was helping her; and Walter and Charles were gone out to gather apples for a pudding which she had promised them.

Lucy much wished to be with them; and after a long brooding over her ill-temper, it began to wear out, not to be conquered, but to depart of itself; she thought she might as well learn her lesson and have done with it; so by way of getting rid of the task, not of profiting by the warning it conveyed, she hurried through the two verses ending with—“Behold how great a matter a little fire kindleth!”

As soon as she could say them perfectly, she raced upstairs, and into her mother’s room, gave her the book, and repeated them at her fastest pace. Poor Lady Woodley was too weary and languid to exert herself to speak to the little girl about her unsuitable manner, or to try to bring the lesson home to her; she dismissed her, only saying, “I hope, my dear, you will remember this,” and away ran Lucy, first to the orchard in search of her brothers, and not finding them there, round and round the garden and pleasance. Edmund, in his hiding-place, heard the voice calling “Walter! Charlie!” and peeping out, caught a glimpse of a little figure, her long frock tucked over her arm, and long locks of dark hair blowing out from under her small, round, white cap. What a pleasure it was to him to have that one view of his little sister!

At last, tired with her search, Lucy returned to the house, and there found Deborah ironing at the long table in the hall, and crooning away her one dismal song of “Barbara Allen’s cruelty.”

“So you can sing again, Deb,” she began, “now the Roundheads are gone and Diggory come back?”

“Little girls should not meddle with what does not concern them,” answered Deborah.

“You need not call me a little girl,” said Lucy. “I am almost eleven years old; and I know a secret, a real secret.”

“A secret, Mistress Lucy? Who would tell their secrets to the like of you?” said Deborah, contemptuously.

“No one told me; I found it out for myself!” cried Lucy, in high exultation. “I know what became of the pigeon pie that we thought Rose ate up!”

“Eh? Mistress Lucy!” exclaimed Deborah, pausing in her ironing, full of curiosity.

Lucy was delighted to detail the whole of what she had observed.

“Well!” cried Deborah, “if ever I heard tell the like! That slip of a thing out in all the blackness of the night! I should be afraid of my life of the ghosts and hobgoblins. Oh! I had rather be set up for a mark for all the musketeers in the Parliament army, than set one foot out of doors after dark!”