Title: John Hus: A brief story of the life of a martyr

Author: William Dallmann

Release date: July 25, 2008 [eBook #26129]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, D Alexander and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

by

JOHN HUS

JOHN HUS

| PAGE | ||

| 1. | The Youth of Hus | 1 |

| 2. | Wiclif's Influence on Hus | 5 |

| 3. | Hus is Opposed | 6 |

| 4. | Hus Offends the Clergy | 6 |

| 5. | Hus Again Rector | 8 |

| 6. | Hus is Accused to the Pope | 10 |

| 7. | Hus Opposes the Pope | 15 |

| 8. | Hus is Excommunicated | 17 |

| 9. | Hus in Exile | 18 |

| 10. | The Council of Constance is Called to Convene | 20 |

| 11. | Hus Arrives at Constance | 22 |

| 12. | Hus in Prison | 28 |

| 13. | Hus Before the Council | 35 |

| 14. | Hus Again Before the Council | 38 |

| 15. | Hus Once More Before the Council | 40 |

| 16. | Hus Prepares for Death | 45 |

| 17. | Hus Condemned | 48 |

| 18. | Hus Degraded | 51 |

| 19. | Hus Made Over to the Emperor | 55 |

| 20. | Hus Burned | 55 |

In a humble hamlet in the southern section of beautiful Bohemia near the Bavarian border of poor peasant parents was born a boy and called Jan—Hus was added from Husinec, his birthplace; some say he saw the light of day on July 6, 1373, but that is not certain.

When about sixteen Hus went to the University of Prag, the first one founded in the German empire by Charles IV in 1348. Here he sang for bread in the streets, like Luther after him, and often had to go to sleep hungry on the bare ground.

WHERE HUS WAS BORN

WHERE HUS WAS BORN

Though many of the thousands of students from all parts of Europe were rowdies and immoral, the behavior of Hus was excellent and his diligence great. He took part in the rough sports; sometimes he played chess and even won money prizes.[Pg 3] To the day of his death none of his many bitter enemies even so much as breathed a suspicion on his pure life. When pardons for sins were publicly sold during a jubilee in 1393, the devout young student gave up his last four pennies to secure this heavenly favor from the Pope.

Jerome of Prag was a fellow student.

In 1393, at a very early age, Hus was made a Bachelor of Arts; in 1394, a Bachelor of Theology; in 1396, a Master of Arts; like Melanchthon, he never took his degree as Doctor of Theology. In 1400, Hus was ordained a priest; in 1401, appointed Dean of the Philosophical Faculty; in 1402, chosen Rector of the University—at an unusually early age. In the same year he became preacher at the important Bethlehem chapel, seating about 1,000 worshipers, founded by John of Milheim in 1391, that the people might hear the Word of God in their own language.

From the very first the powerful preacher made his pulpit potent and popular, even among the nobility; Queen Sophia was a frequent worshiper, made him her confessor, and had him appointed court chaplain.

BETHLEHEM CHAPEL

BETHLEHEM CHAPEL

When Anne, the daughter of Emperor Charles IV, and sister of King Wenzel of Bohemia and of King Sigismund of Hungary, was married to King Richard II of England in 1382, there was much travel between Bohemia and England, and Jerome of Prag brought the writings of Wiclif from Oxford. They spread like wild fire, deeply impressed Hus, and made him an apt pupil and loyal follower of the great "Evangelical Doctor." He saw the dangers ahead and said in a sermon: "O Wiclif, Wiclif, you will trouble the heads of many!"

Converted by missionaries from Greece, the Bohemians never felt quite so dependent on Rome. They had the Bible translated in their own language; Queen Anne took with her the Gospels in Latin and German and Bohemian. In addition Milic of Kremsier and Matthias of Janov had but recently fiercely denounced the wicked lives of popes and prelates and priests. So it came that the teaching of Wiclif and the preaching of Hus fell upon the Bohemian soul as upon a prepared soil.

On May 28, 1403, Master John Huebner in the Church of the Black Rose called attention to certain condemned statements of Wiclif—many of which had been forged. Hus cried out the falsifiers ought to be executed the same as recently the two adulterators of food. After a stormy debate in the great hall of the Carolinum, a majority of the professors forbade the public and private teaching of these articles, forty-five in all.

The decree produced no effect, and the opponents of Hus got Pope Innocent VII to order the Archbishop to root out the heresy of Wiclif, in 1405.

In 1405, Archbishop Sbynko appointed Hus the Synodal preacher, and he often with fierce and fiery fervor severely scored the avarice and immorality of the clergy. He held sin no more permitted to a clergyman than to a layman, and indeed more blameworthy—a most astonishing novelty, [Pg 7]especially to the priesthood. They honored him with their undying hatred.

About this time two followers of Wiclif, James and Conrad of Canterbury, came to Prag and in their house outside the city painted a cartoon contrasting the lowly Christ and the proud pope. Crowds went to view it, and Hus recommended it from the pulpit as a true representation of the opposition between Christ and Antichrist. Later Luther edited similar cartoons—"Passional of Christ and Antichrist."

When amid the wreckage of a church at Wilsnack in Brandenburg a red wafer was found, it was proclaimed the blood of Christ, preserved through thirteen centuries or sent direct from heaven, had baptized and reddened the white wafer, or host. The miracle drew many pilgrims from even distant countries to be cured of their incurable diseases; of course, they left much money to the pious priests. Hus condemned this coarse fraud, and Archbishop Zbynek, or Sbynko, forbade the pilgrimages from his diocese.

In order to justify his step, Hus wrote a book asserting a Christian need not seek for [Pg 8]signs and miracles but need only hold by the Holy Scriptures.

Hurt in pride and pocket, the enraged clergy lodged complaints against Hus as a pestiferous heretic, who had to be suppressed; he lost his position as the Synodal preacher in 1408.

Since 1378, there were two sets of rival popes most lustily pelting one another with papal curses. The Council of Pisa in 1409 deposed popes Benedict XIII and Gregory XII as heretics and schismatics and then elected Alexander V, who died on May 11, 1410, most probably poisoned by "Diavolo Cardinale" Cossa, who then became Pope John XXIII. Now there were three popes and a three-cornered fight. To make the good old times still more interesting, three rivals struggled for the crown of the Holy Roman Empire.

POPE ALEXANDER V

POPE ALEXANDER V

Though King Wenzel demanded strict neutrality, Archbishop Sbynko sided with Gregory XII, and at the University the Bohemian "nation" under the lead of Hus was the only one to remain neutral. Wenzel[Pg 10] was bitter and on Jan. 18, 1409, decreed the Bohemian "nation" three votes and the three German "nations" one vote in all University affairs.

Aeneas Sylvius, later Pope Pius II, estimates that 200 German professors and students on May 16, 1409, left Prag and founded the University of Leipzig and spread the news of the Bohemian heresies and hatred of Hus.

At Prag Hus was now at the height of his influence, enjoying the favor of the Court; he was again elected Rector of the University.

Now Archbishop Sbynko went over to the rival pope, Alexander V, and convinced him that all the troubles in Bohemia were due to the teachings of Wiclif spread by Hus. These teachings, he said, made the clergy disobedient and led them to ignore the authority of the Roman Church, made the laity think it was for them to lead the clergy, encouraged the King to lay hands on the property of the Church.

KING WENZEL OF BOHEMIA

KING WENZEL OF BOHEMIA

As a result Alexander V sent a bull on[Pg 12] Dec. 20, 1409, ordering the Archbishop to suppress all books of Wiclif and all preaching except at the usual places; this last was to silence Hus in Bethlehem Chapel.

On July 16, 1410, the Archbishop burned two hundred manuscripts of Wiclif, many of them in costly binding; two days later he excommunicated Hus and his followers.

POPE JOHN XXIII

POPE JOHN XXIII

This caused an indescribable sensation all over, in some places serious riots resulted. The publishers of the excommunication were in danger of their lives. The King compelled the Archbishop to pay damages to those whose manuscripts had been burned. Hus defended the writings of Wiclif in public debates. The Wiclifites in England were delighted. Hus wrote them: "The whole Bohemian people thirst for the truth, it will have nothing but the Gospel and the Epistles, and wherever in a city or village or castle a preacher of the holy truth appears, the people stream together in great crowds. Our king, all his court, the barons, and the plain people favor the word of Christ." Hus continued to preach in the Bethlehem Chapel in ever bolder tones. He said: "We must obey God rather than men in things which are necessary for salvation."[Pg 14] Against the authority of the Church Hus placed the individual conscience. The decisive step of a breach with the Papal system had been taken.

Hus, the King, and the Queen repeatedly appealed to the new Pope, but John XXIII twice confirmed the sentence of Pope Alexander V; Hus was declared a heretic and Prag placed under interdict. This was done on the advice of Cardinal Otto Colonna, later Pope Martin V. Hus was summoned to appear before the Pope. Hus did not appear; he was pronounced excommunicated in February 1411, published in Prag on March 15, 1411.

The bold preacher said: "I avow it to be my purpose to defend the truth which God has enabled me to know, and especially the truth of the Holy Scriptures, even to death, since I know that the truth stands and is forever mighty and abides eternally; and with Him there is no respect of persons. And if the fear of death should terrify me, still I hope in my God and in the assistance of the Holy Spirit that the Lord will give me firmness. And if I have found favor in His sight He will crown me with martyrdom."

In June the King's commission requested the removal of the interdict. On September 28, the Archbishop died; they say he poisoned himself. In the attempt to sacrifice Hus, he sacrificed himself.

On Dec. 2, 1411, Pope John XXIII decreed a crusade against King Ladislas of Naples, who favored the rival Pope Gregory XII, "the heretic, blasphemer, schismatic," as John called him, and offered a plenary indulgence, or forgiveness of sins, to all who would give money for the war.

Tiem, the papal pedler, like Tetzel a century later, caused trouble. He came to Prag and with beating of drums ordered the people into the churches, where contribution boxes had been placed; even the confessional was abused to extort money from the people.

In the University and in the Church Hus protested against this shameless business. On June 7, 1412, there was a great disputation on the subject in the large hall of the Carolinum. Hus held no pope or bishop had the right to draw the sword in the name [Pg 16]of the Church, he must pray for his enemies and bless them that curse him. Man gets forgiveness of sins through real sorrow and repentance, not through money. Unless one be of the elect, the indulgence will do him no good. If the Pope's bulls are against the Bible, they are to be resisted.

Jerome also made a stormy speech, and the younger scholars escorted him home in triumph.

On June 24, there was an uproarious procession, and a crowd burned the Pope's bull.

The King threatened death for speaking against the indulgence.

On Sunday, July 10, three young men in church called the indulgence a lie. Hus and thousands of students pleaded for them. The magistrates made fair promises, but on Monday the three young men were executed. They were buried in Bethlehem Chapel, which the people now called the "Church of the Three Saints." The Reformation had won its first martyrs.

King Wenzel now forbade the preaching of Wiclif's teaching. Hus demanded it be proven against the Bible, and proceeded to prove it in accordance with the Bible.

The riots at Prag caused a disagreeable sensation in all Bohemia, but all efforts for peace were vain.

Pope John XXIII turned the case of Hus over to Cardinal Annibaldi, who promptly pronounced the greater excommunication against Hus: if within twenty days he did not submit to the Church, none were to speak to him or receive him into their houses; all church services were to cease when he was present, and the sentence was to be read in all churches in all Bohemia on all Sundays. A second decree ordered all the faithful to seize Hus and deliver him to be burned; Bethlehem Chapel was to be leveled with the ground.

As Bishop Robert Grosseteste of Lincoln before him, Hus now appealed from the Pope to Jesus Christ, the Supreme Head of the Church.

The excitement grew greater. Bloody conflicts loomed ahead. On the royal request Hus left Prag in the autumn of 1412.

As later Luther in the Wartburg, so Hus now found shelter in the castle of the Lord of Usti, and later with Henry of Lazan in his castle of Cracowec.

Hus had a rare gift of persuasion, and wherever he preached, in city or country, everybody became his follower; he was the pastor of his people; his immense popularity clings to his memory to the present day.

Besides much preaching, the exile did much writing. He revised a Bohemian translation of the Bible of the fourteenth century and thereby greatly improved the popular language, much like Luther with his German Bible. He guarded the purity of his Bohemian language against the foreign, disfiguring influences. He labored to establish fixed rules of grammar and invented a new system of spelling, which is in general use today! He wrote letters, tracts, poems, and hymns. His chief work was "On the Church," based on Wiclif, often to the word and letter.

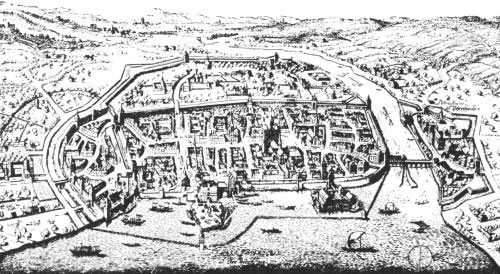

CONSTANCE ON THE RHINE

CONSTANCE ON THE RHINE

The excitement in Prag continued. The King convened the Estates of the realm for[Pg 20] Christmas, 1412. These called for a Synod, which met Feb. 2, in the Archbishop's palace at Prag; it was a failure. The King had a Commission continue the work of peace in April, 1414. The papists held the Pope the Head of the Church, the Cardinals the body of the Church, and all commands of this Church are to be obeyed. Of course, Hus and his followers could not accept such monstrously wicked teaching. On the contrary, Hus held it the duty of kings to restrain the wickedness of the clergy and root out simony.

King Sigismund and Pope John XXIII, the two vilest men then living on the face of the earth, were the rulers of the Christian world, and they agreed to call a General Council at Constance, in Baden, near Switzerland, for Nov. 1, 1414, in order to end the Schism, to begin the sorely needed reform of the Church, and to settle the heresies of Wiclif and Hus.

THE EMPEROR SIGISMUND

THE EMPEROR SIGISMUND

Heir to his childless brother Wenzel's Bohemian crown, King Sigismund of Hungary[Pg 22] was naturally anxious to have the stain of heresy removed from the fair land that was now the talk of the world, and he ordered three Bohemian noblemen to protect Hus on his way to Constance, during his stay at the Council, and on his return to Bohemia.

Even Divucek, one of Sigismund's envoys, warned Hus, "Master, be sure that thou wilt be condemned."

Thinking he was going to his death, Hus put his house in order, got a certificate of orthodoxy from his bishop, and bade farewell to his people—"Beloved, if my death ought to contribute to the Master's glory, pray that it may come quickly and that He may enable me to support all my calamities with constancy. You will probably nevermore behold my face at Prag."

He set out on Oct. 11, as boldly as later Luther to Worms.

On his journey Hus was everywhere welcomed heartily and at Biberach even triumphantly. He reached Constance, a beautiful city of fifty thousand inhabitants,[Pg 24] on Nov. 3, and found lodgings with Fida, "a second widow of Sarepta," in St. Paul St.,—now Hus St.—near the Schnetz Gate, not far from the abode of Pope John XXIII. On the same day came the historic and notorious safe-conduct of Sigismund—"The honorable Master John Hus we have taken under the protection and guardianship of ourselves and of the Holy Empire. We enjoin upon you to allow him to pass, to stop, to remain and to return, freely and without any hindrance whatever; and you will, as in duty bound, provide for him and for his, whenever it shall be needed, secure and safe conduct, to the honor and dignity of our Majesty." Dated at Speyer, October 18, 1414.

HOUSE WITH TABLET WHERE HUS LODGED AND THE SCHNETZ GATE.

HOUSE WITH TABLET WHERE HUS LODGED AND THE SCHNETZ GATE.

John XXIII with piratical pomposity promised the papal protection: "Even if Hus had killed my own brother, he shall be safe in Constance."

With the Emperor Sigismund came twenty princes and one hundred and forty counts. The Pope had been a pirate; at Bologna he had plundered and oppressed his people and sold licenses to usurers, gamblers, and prostitutes; his cruelty thinned the population; in the first year as [Pg 25]legate at Bologna he outraged two hundred maidens, wives, or widows, and a multitude of nuns; at least so Catholic historians say.

With this holy father there came to the Council twenty-nine cardinals, seven patriarchs, over three hundred bishops and archbishops, four thousand priests, two hundred and fifty university professors, besides Greeks and Turks, Armenians and Russians, Africans and Ethiopians, in all from sixty to a hundred thousand strangers, and thirty thousand horses.

In order to amuse these godly fathers amid their grave labors there came seventeen hundred artists, dancers, actors, jugglers, musicians and—prostitutes, seven hundred public ones, not counting the private ones.

Hus wrote: "Would that you could see this Council, which is called most holy and infallible; truly you would see great wickedness, so that I have been told by Suabians that Constance could not in thirty years be purged of the sins which the Council has committed in the city."

These men of sin, who kissed the toe of Pope John XXIII, a man of sin, burned the saintly Hus; no wonder he likened them to [Pg 26]the scarlet whore of the Revelation. At one stage of the holy and infallible Council these learned fathers used arguments that strike us as rather striking: a cardinal assaulted an archbishop; a patriarch hit a protonotary; a Spanish prelate hurled an Englishman into the mud; the English were caught in arms to assault Pierre d'Ailly, the Cardinal of Cambray. As members of the Church militant they were certainly fighting a good fight.

Sigismund burnt Hus as a Wiclifite, the next year the Council called the Emperor a Wiclifite and Hussite and heretic. Pope John XXIII condemned Hus as a heretic, soon after he was a prisoner in the same prison with Hus. Dramatic!

PIERRE D'AILLY

PIERRE D'AILLY

John Gerson, the celebrated Chancellor of the great University of Paris and "Doctor Christianissimus," and Pierre d'Ailly, the great Cardinal of Cambray, accused Hus of heresy; later on themselves were accused of heresy by the same Council. Gerson declared Hus had never been sentenced had not an attorney been denied him, and himself would rather be tried by Jews and infidels than before the commission. Such [Pg 28]were the men that were to try a man such as Hus.

As Paul preached in his own hired house under the very palace of Nero, so Hus preached Christ to all who came to his humble house and with a few friends maintained daily worship, close to the Pope's palace. Greater than emperors and popes, princes and prelates from all Europe that crowded Constance, was the humble Bohemian Hus; they are seen today mainly in the light shed from his shining name.

Despite the royal safe-conduct and the promised papal protection, Hus was flung into prison in a prelate's palace on Nov. 28.

John of Chlum forced his way into the papal apartments and charged the holy ex-pirate Pope John XXIII to his infallible face with having broken his sacred papal promise, and then fixed on the doors of the Cathedral a solemn protest against the papal perfidy and the shameless violation of the royal safe-conduct.

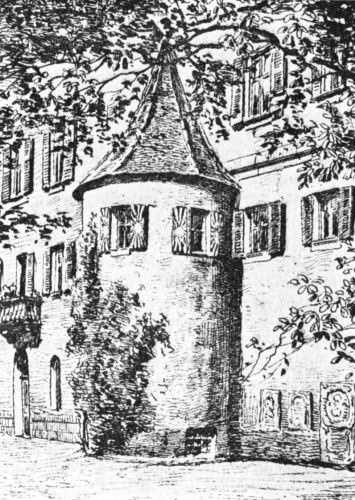

HUS TOWER

HUS TOWER

On Dec. 6, Hus was dragged to the Dominican[Pg 30] convent on an island in Lake Constance, and stuck into a dark hole at the opening of a sewer, where he was struck down by a violent fever, so that his life was despaired of, and the Pope sent his own physician.

Crowned in Aachen on Nov. 8, as Emperor of Germany, Sigismund arrived in Constance on Christmas and seated himself in his imperial robes on his throne in the cathedral during the imposing religious service.

The Emperor read the Gospel for the day from Luke 2: 1—"There went out a decree from Caesar Augustus." The Pope trembled as he saw before him the successor to the throne and power of Caesar.

Near the Emperor sat the Empress; beside him stood the Markgraf of Brandenburg with the scepter; the Duke of Saxony, as marshal of the realm, held aloft a drawn sword; between the Pope and the Emperor stood his father-in-law, Count Cilley, holding the golden globe; the Pope handed the Emperor a sword with the charge to use it in defence of the Church, which Sigismund promised to do.

When the Emperor heard his safe-conduct [Pg 31]had been disgracefully broken, he blustered. The Pope insisted the Emperor had no right to interfere in the treatment of a pestilent heretic. The Emperor broke his sacred word and sacrificed Hus to his enemies.

This treachery cost him the kingdom of Bohemia. The Holy Synod defended Sigismund, declaring "no faith whatever, either by natural, human or divine right, ought to be observed toward a heretic."

On the same day, New Year, 1415, the Emperor also sacrificed the Holy Father, John XXIII.

About the first of March Hus was taken to the Franciscan convent near the Pope's dwelling and fed from the Pope's kitchen, that is, he was almost starved; on March 20, the Pope fled, and Hus had to go without food for three days.

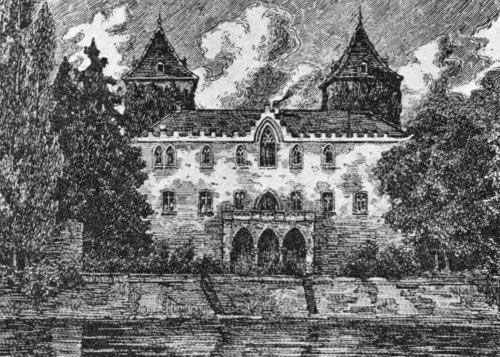

CASTLE OF GOTTLIEBEN ON THE RHINE

CASTLE OF GOTTLIEBEN ON THE RHINE

Did the Emperor release Hus, now that the Pope was fled? On March 25, the Emperor turned Hus over to the Bishop of Constance, who imprisoned him in his Castle of Gottlieben in a chamber so low Hus could not stand upright. He was handcuffed by day and chained to the wall by night, poorly fed, and separated from his [Pg 33]friends; and this went on for seventy-three days!

"The holy and infallible Council," as the Pope called it, brought against the infallible Pope seventy-two charges—the murder of Pope Alexander V, rape, adultery, sodomy, incest, simony, corruption, poisoning, denying the resurrection and eternal life, etc., etc.

Though hostile to the Pope personally, the Patriarch of Antioch quoted Gratian that if a Pope, by his misconduct and negligence, should lead crowds of men into hell, no one but God would be entitled to find fault with him.

The Pope promised to resign, and the Emperor joyfully kissed the toe of John XXIII and thanked him in the name of the Council.

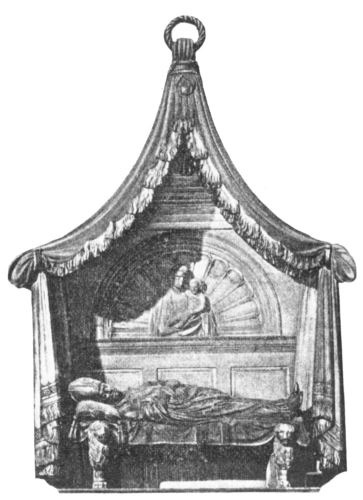

MONUMENT TO POPE JOHN XXIII

MONUMENT TO POPE JOHN XXIII

The Council considered the charges proved and on May 25, 1415, deposed him as "the supporter of iniquity, the defender of simonists, the enemy of all virtue, the slave of lasciviousness, a devil incarnate." The Bishop of Salisbury thought he ought to be burnt at the stake. And yet this precious prelate was made a cardinal and after his death at Florence on Nov.[Pg 35] 23, 1419, an exquisite monument by Donatello was erected in 1427 to his saintly memory.

When the Council deposed John XXIII, Hus wrote: "Courage, friends! You can now give answer to those who declare that the Pope is God on earth; that he is the head and heart of the Church; that he is the fountain from which all virtue and excellence issue; that he is the sun, the sure asylum where all Christians ought to find refuge. Behold this earthly god bound in chains!"

On June 3, Pope John XXIII was a prisoner in the same prison with Hus!

On May 4, Wiclif's writings were ordered to be burnt as heretical; his memory was condemned, and it was decreed to dig out his bones and cast them out of consecrated ground. It does not need a prophet to foretell the end of Hus. It needed only to show Hus was a follower of Wiclif, and he would be burned also.

Though the Bohemians and Moravians earnestly protested against the harsh [Pg 37] treatment of Hus and demanded his release, he was not released. On June 5, he was brought to the Franciscan cloister, between the Cathedral and St. Stephen's Church, where he spent his last days on earth.

CATHEDRAL OF CONSTANCE

CATHEDRAL OF CONSTANCE

In the afternoon, bearing his chains, he was brought before the Council. He admitted the authorship of his books and declared himself ready to retract every expression that could be proved wrong.

The first article was then read. When Hus tried to reply, he was bellowed into silence. When he was silent, they said, Silence gives consent.

Socrates was allowed to make a long defence before his heathen judges; Hus was overwhelmed with angry outcries by the representatives of all Christendom!

Luther commented: "All worked themselves into a rage like wild boars. The bristles of their backs stood on end; they bent their brows and gnashed their teeth against John Hus."

Hus protested: "I supposed that there would have been more fairness, kindness, and order in the Council." Hus asked wherein he had erred. "Recant first, and [Pg 38]then you will be informed!" Thus ended the first hearing.

When a synod would condemn Wiclif's writings in May, 1382, an earthquake delayed the decision, and when the Council on June 7, 1415, would condemn Hus, a total eclipse of the sun delayed the proceeding. At one o'clock the sky was clear and Hus was again brought in, again in chains, and under guard. He was accused of denying the presence of Christ's body in the sacrament. Hus repelled the charge and stuck to it against the famous Pierre d'Ailly of Cambray and many other French and Italian prelates, and he did it so stoutly that the British objected: "This man, so far as we see, has right views as to the sacrament of the altar." Violent disputes arose. As the Roman captain had to interfere when Paul stood before the factions of the Jewish Sanhedrin, so the Emperor Sigismund had now to exercise his authority and command and compel order in the grave and reverend holy Council. Hus could not with a good conscience condemn[Pg 40] all of Wiclif's writings until they were proven against Holy Scriptures, and such was his admiration of the stainless life of the man, that he wished his soul might be where Wiclif's was.

THE INTERIOR OF THE CATHEDRAL

THE INTERIOR OF THE CATHEDRAL

Renewed jeers and derision. Pierre d'Ailly advised Hus to submit to the Council; the Emperor likewise, since he would not protect a heretic; rather would he with his own hands fire the stake.

"I call God to witness ... that I came here of my own accord with this intent—that if any one could give me better instruction I would unhesitatingly change my views."

In the final hearing, on June 8, thirty-nine articles from his books were brought against Hus, twenty-six of them from his "On the Church." He was charged with teaching that only the electing grace of God made one a true member of the Church, not any outward sign or high office. This God's truth was condemned as false by the Council.

Hus held the Pope a vicar of Christ only [Pg 41]as he imitates Christ in his living; if he lives wickedly, he is the agent of Antichrist.

The prelates looked at one another, shook their heads and laughed. If Hus was to be burned for only saying that, what did they deserve for actually imprisoning the Pope?

Hus held the Pope's temporal power came from the (forged) donation of the Emperor Constantine, not from Christ, and stoutly stuck to it against the great Cardinal of Cambray.

Hus had spoken and written plainly against the wicked lives of prelates and popes, and for this he was to be burned, although d'Ailly and Gerson also had done so, and this very Council had deposed a vile wretch, Pope John XXIII.

Another heresy of Hus was this: "A heretic ought to be first instructed kindly, justly, and humbly from the Sacred Scriptures," then he may be burned.

"All those who give up to the civil sword any innocent man, as the scribes and Pharisees did Christ," are like the Pharisees.

HUS BEFORE THE COUNCIL, BY BROZIK

HUS BEFORE THE COUNCIL, BY BROZIK

The Prelates felt the thrust. "You mean[Pg 43] to condemn the dignitaries of the Church!" For this they would burn Hus.

Hus said an evil nature cannot do good. In a state of grace, however, the man, whether he eat or drink or sleep, does everything to the glory of God. This plain truth of God was damned as heresy!

Hus was charged with calling an unjust excommunication a benediction. "In truth, I say the same thing now, according to that Scripture, 'They shall curse, but Thou shalt bless'."

Another heresy ran thus: "If pope, bishop or prelate be in mortal sin, then is he no longer pope, bishop or prelate." Hus defended it by asking pointedly: "If John XXIII was a true pope, why did you depose him from his office?"

Hus said the Church did not need an earthly head, a pope; Christ, the true head, can rule His church better without the popes, who were often monsters of iniquity. Shouts of derision!

Hus calmly added the telling point: "Surely the Church in the times of the Apostles was infinitely better ruled than now. At present we have no such head at all."

He could not be answered, and so he was derided.

An Englishman correctly pointed out that this was the teaching of Wiclif. That was ample to damn Hus as a heretic.

Pierre d'Ailly said to the Emperor Sigismund: "Almost all the articles are based on Wiclif, so that the Englishman John Stokes was right in saying Hus had no right to boast of these teachings as his property, since they all demonstrably belonged to Wiclif."

In order to embitter the Emperor against Hus, they tried to show his teachings to be dangerous to the civil government. Finally d'Ailly advised Hus to submit to the Council. Hus again said he was open to conviction. He only asked for a hearing to explain and prove his doctrines. If his reasons and Bible proofs were not sufficient, he would be ready to be taught better.

The Cardinal said: "You have only to perform the three conditions required of you—to confess your errors, to promise not to teach them hereafter, and to renounce all the articles charged against you."

Sigismund also again urged Hus to submit, [Pg 45]and said, in effect: "Recant now, or die."

Hus humbly but firmly refused to do anything against his conscience; he asked for proof from God's word, then he would submit.

"I stand before the judgment of God; He will judge me and you in righteousness, as we deserve it."

As Hus was led back to prison, John of Chlum, a Bohemian nobleman, shook hands with him, just as Frundsberg comforted Luther at Worms.

Sigismund hounded on the prelates to make an end of Hus, even if he recanted. This lost him the Bohemian crown for ever.

Hus had about a month after the trial to await the end. He remembered his and his friends' forebodings, and wrote bitterly: "Put not your trust in princes. I thought the Emperor had some regard for law and truth; now I perceive that these weigh little with him. Truly did they say that Sigismund would deliver me up to my adversaries: he has condemned [Pg 46]me before they did. Would that he could have shown me as much moderation as the heathen Pilate."

He wrote a touching farewell letter to his beloved flock in the Bethlehem Chapel and another to the University at Prag.

After Hus had left Prag, Jacobellus of Mies began to give the cup as well as the bread to the lay communicants. The General Council on June 15, admitted Christ had instituted the Lord's Supper in the two species of bread and wine, yet it decreed to burn as heretics all who did as Christ commanded.

Hus on June 21, writes to Gallus (Havlik), preacher at the Bethlehem Chapel: "What wickedness! Behold, they condemn Christ's institutions as heresy!"

Till the end of June they made many efforts to get Hus to recant; he firmly refused: "I cannot recant; in the first place, I would thereby recant many truths, and in the second place, I would commit perjury and give offence to pious souls. I stand at the judgment-seat of Christ, to whom I have appealed, knowing that He will judge every man, not according to false witness, but according to the truth and each one's [Pg 47]deserts." Against the authority of men Hus asserted the authority of his conscience enlightened by the Holy Scriptures.

On July 1, Hus was brought out again to recant his heresies. He replied in writing: "I, John Hus, fearing to sin against God, and fearing to commit perjury, am not willing to abjure ... any of them."

On July 5, a deputation of some of the most eminent members of the Council made a final effort to get Hus to recant. Wenzel of Duba said: "Behold Master John, I am a layman and cannot give advice. Consider then if thou feelest thyself guilty of any of the things of which thou art accused. If so, do not hesitate to accept instruction and recant. But if thou dost not feel guilty of these things that are brought forward against thee, be guided by thy conscience, do nothing against thy conscience, nor lie before the face of God; rather hold unto death to the truth as thou hast understood it."

Hus answered in tears: "Be it known to you that if I knew I had written or preached anything against the law and holy Mother Church, I would humbly recant; may God be my witness to this; but I always desired [Pg 48]that they should show me doctrines better and more credible than those I have written and taught. If such be shown me, I will gladly recant."

A bishop sneered: "Wilt thou then be wiser than the whole Council?"

Master Hus replied: "I do not claim to be wiser than the whole Council, but, I beg you, give me the least man at the Council that he may instruct me out of the word of God, and I am ready to recant at once."

"Behold, how obstinate he is in his heresy!"

On Saturday, July 6, the Council had great scruples in condemning the Duke of Burgundy, a self-confessed would-be assassin, but it had absolutely no scruples in condemning the blameless patriot reformer of Bohemia.

"Dressed in black with a handsome silver girdle, and wore his robes as a Magister"—Hus was led after Mass before the whole Council in the cathedral. He kneeled and prayed fervently for several minutes. James Arigoni, Bishop of Lodi, preached from [Pg 49]Rom. 6:6—"That the body of sin might be destroyed." Henry de Piro proposed that Hus be delivered to the civil power for burning.

Sixteen charges from Wiclif's writings were read. When Hus tried to explain, he was brutally refused. Thirty articles from Hus' own works were then read. He attempted to speak, but was stopped by loud cries, despite the admonition of the Bishop of Constance.

Hus knelt down and cried: "I beg you, in the name of God, to grant me a hearing, that those who are present may not think I am a heretic. After that deal with me as you see fit."

They threatened to silence him forcibly by the soldiers. He continued to kneel and pray with uplifted face to God, the just Judge.

Hus was next charged with saying, "that he was and would be a Fourth Person in the Trinity."

Even the Roman Catholic Hefele admits the absolute falsehood of this infamous accusation.

When his appeal to Christ was condemned as a damnable heresy, Hus cried out: "O [Pg 50]God and Lord, now the Council condemns even Thine own act and Thy law as heresy, for Thou Thyself didst commend Thy case into the hands of Thy Father as the righteous judge."

Charged with treating the papal excommunication with contempt, Hus replied he had three times sent representatives to the papal court and had never had a hearing. "For this reason I came freely to this Council, relying upon the public faith of the Emperor, who is here present, assuring me that I should be safe from all violence, so that I might attest my innocence and give a reason of my faith to the whole Council."

As he spoke of the safe-conduct, the prisoner looked straight at the Emperor; the Emperor blushed. That blush was never forgotten. Urged to betray Luther at Worms, the Emperor Charles V said: "I should not like to blush like Sigismund."

"A bald and old Italian priest" then read the two decrees of the Council that all the writings of Hus, both Latin and Bohemian, should be destroyed, and that Hus as a true and manifest heretic was to be burned.

Hus loudly protested: "Up to now you [Pg 51]have not proved that my books contain any heresies. As to my Bohemian writings, which you have never seen, why do you condemn them?"

Hus again knelt and prayed with a loud voice: "Lord Jesus Christ, forgive all my enemies, I entreat Thee, because of Thy great mercy. Thou knowest that they have falsely accused me, brought forth false witnesses against me, devised false articles against me. Forgive them because of Thy boundless mercy."

This touching prayer was greeted with derisive laughter by the foremost ecclesiastical dignitaries.

The priestly robes were now put on Hus, and the sacramental cup into his hands. When the white robe, the alb, was put on, Hus said: "My Master Christ, when He was sent away by Herod to Pilate, was clothed in a white robe."

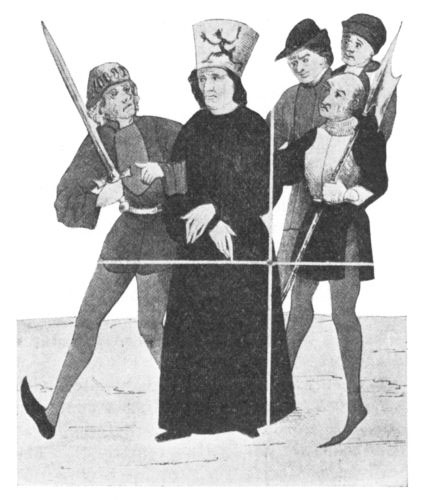

HUS DEGRADED, BY MARTERSTEIG

HUS DEGRADED, BY MARTERSTEIG

He was once more urged to swear off his errors. Turning to the people with tears in his eyes and emotion in his trembling[Pg 53] voice—"How could I thus sin against my conscience and divine truth alike?"

As they took off his priestly robes, the Archbishop of Milan said: "O cursed Judas, who hast left the realms of peace and allied thyself with the Jews, we today take from thee the chalice of salvation."

"I hope to drink of the chalice in the heavenly kingdom this day."

The holy fathers of the General Council of all Christendom then gravely and learnedly debated whether to use shears or a razor to remove the tonsure. Finally they decided for the shears, and his hair was cut to leave bare the form of a cross. Next his head was washed, to remove the oil of anointing, by which he had been consecrated to the priesthood.

A paper cap, two feet high, painted with three ghastly devils tormenting a soul, and with the words, "This is a heretic," was placed on his head; Hus remarked: "My Lord Jesus Christ wore for me a crown of thorns; why should I not for His sake wear this easier though shameful badge?"

HUS WITH THE HERETIC'S CAP

HUS WITH THE HERETIC'S CAP

Doomed by the Church, Hus was now made over to the Emperor, with the usual hypocritical prayer that he might not be put to death.

Sigismund said: "Sweet Cousin, Duke Louis, Elector of the Holy Roman Empire and our High Steward, since I bear the temporal sword, take thou this man in my stead and treat him as a heretic."

The "sweet cousin" called the warden of Constance: "Warden, take this man, because of the judgment against him, and burn him as a heretic." Others added: "And we give thy soul over to the devil."

"And I commit my soul to the Lord Jesus Christ."

The Warden made him over to the executioner, who led Hus out under a strong guard, escorted by eight hundred armed men, followed by an immense multitude of people curious to see the final scene.

In the church-yard they were just burning the books of Hus; he smiled sadly.[Pg 57] With a firm step, singing and praying, Hus went to the "Bruehl," a quarter of a mile north of the Schnetz gate. There he knelt, spread out his hands, lifted up his face, and prayed with a loud voice: "Into Thy hands I commit my spirit."

HUS LED TO DEATH, BY HELLQUIST

HUS LED TO DEATH, BY HELLQUIST

The paper cap, "the crown of blasphemy," as it was called, fell to the ground, and Hus noticed the three painted devils; smiling sadly, he said: "Lord Jesus Christ, I will bear patiently and humbly this horrible and shameful and cruel death for the sake of Thy Gospel and the preaching of Thy word."

He was stripped of his clothes, his hands roped behind his back, his neck chained to the stake, wood and straw were piled around him neck-high. They say as an old woman brought her few fagots to the funeral pile, Hus cried out: "O sancta simplicitas!"—O holy simplicity. Another story goes Hus said: "Today you are burning a goose (hus in Bohemian); in a hundred years will come a swan you will not burn." This came true in Luther.

In the last moment the Marshal of the realm, Pappenheim, called on Hus to recant and save his life. "God is my witness [Pg 58]that I never taught of what false witnesses accuse me. In the truth of the Gospel, that I have written, taught, and preached, I will today joyfully die."

The fagots were lighted. With raised voice Hus sang: "O Christ, Thou Son of the living God, have mercy on me." When he sang that and continued, "Thou that art born of the Virgin Mary," the wind drove the flames into his face; his lips and head still moved; then he choked without a sound.

As the flames flickered down, the executioners knocked over the stake with the charred body still dangling by the neck, heaped on more wood, poked up the bones with sticks, broke in the skull, ran a sharp stake through the heart, and set the whole ablaze again. The jumbled embers were thrown into a wheelbarrow and tipped into the Rhine.

Like Luther later, Hus placed his conscience above the mighty Emperor, the infallible Pope, and the learning of the world; he would rather die than lie.

JEROME OF PRAG

JEROME OF PRAG

Even Aeneas Sylvius, later Pope Pius II, afterwards said with admiration: "No one[Pg 60] of the ancient Stoics ever met his death more bravely."

A year later, on May 30, on the same spot in the same clover field they burned Jerome of Prag. He went to his death with a smiling face. "You condemn me, though innocent. But after my death I will leave a sting in you. I call on you to answer me before Almighty God within a hundred years."

When the fagots were lighted, he sang the Easter hymn, "Hail, Festal Day," and protested his innocence to the bystanders. His last words were in Bohemian, "God Father, forgive me my sins."

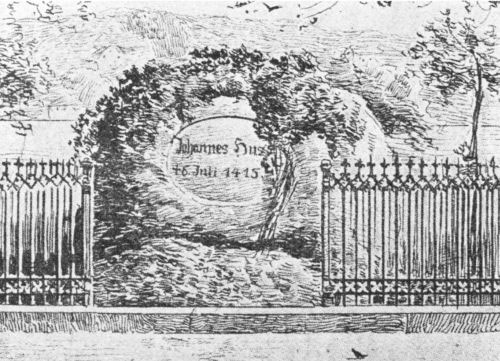

A great stone marks the spot where the two Bohemian saints ascended to heaven in chariots of fire.

The words of Erasmus might well have been his epitaph—"John Hus, burned, not convicted." Lechler says: "To inflict defeat by meeting defeat, that was his lot."

Wiclif and Hus are the constellation "Gemini," or Twins, shining in the papal night till their dim twinkling is swallowed up in the glorious sun bursting from Wittenberg in Luther.

THE BRUEHL, PLACE OF BURNING

THE BRUEHL, PLACE OF BURNING

The Synod of Pisa tried to reform the[Pg 62] Church and failed. The Synod of Constance tried it and failed. The Synod of Basel and Ferrara tried it and failed. The Fifth General Lateran Synod from 1512-1517 tried it and failed. The great Roman Catholic scholar Von Doellinger says: "The last hope of a reformation of the Church was carried to the grave."

What could not be done by all Europe was done by Luther.

Luther's reformation brought liberty for Church and State, and to him we owe it that men like Hus can no longer be burned.

JESUS—His Words and His Works, 20 Art Plates in Colors after Dudley, 195 Half-tones, and 2 maps of Palestine. IX and 481 pages. Size 7-¾ x 10. Beautifully bound. Gilt top. $3.00.

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS Third Edition. 335 Pages. $1.00.

FOLLOW JESUS 300 Pages. Cloth, $1.00.

THE LORD'S PRAYER 271 Pages, $1.00.

PORTRAITS OF JESUS Cloth, 227 Pages. $1.00.

| Christian Science Unchristian. 5th Ed. | 05c | |

| Mission Work. 4th Edition | 05c | |

| What is Christianity? 3d Edition | 05c | |

| Temperance. 2d Edition | 05c | |

| Why Lutheran, not 7 Day Advent. 2d | ||

| Edition | 05c | |

| Why the Name "Lutheran." 2d Ed. | 05c | |

| Infant Baptism. 6th Edition | 05c | |

| Christian Giving No. 2. 3d Thousand | 10c | |

| Why I Believe the Bible. 2d Edition | 15c | |

| The Real Presence. | 10c | |

| The Dance. 5th Edition | 05c | |

| The Theater. 2d Edition | 05c | |

| Opinions on Secret Societies. 2d Ed. | 05c | |

| Freemasonry. 2d Edition | 05c | |

| Oddfellowship. 2d Edition | 05c | |

| Churchgoing. 3d Edition | 05c | |

| What Think Ye of Christ? 2d Ed. | 05c | |

| Wm. Tyndale, Translator Eng. Bible. | 10c | |

| Patrick Hamilton, Scotch Martyr. | 10c | |

| The Pope in Politics. 2d Edition | 05c | |

| Church and State. 2d Edition | 05c | |

| Carlyle's Luther. | leather | 20c |

| paper | 10c | |

| Why Protestant, not Roman Catholic | 05c | |

| Principles of Protestantism. | 02c | |

| Why I am a Lutheran. 5th Edition | 05c | |

| Luther's Catechism. 8th Edition | 10c | |

| The Congregational Meeting. | 05c | |

| Luther and our Fourth of July. | 05c |

Minor changes have been made to correct typesetters' errors; every effort has been made, otherwise, to remain true to the author's words and intent.