Title: The Joyous Adventures of Aristide Pujol

Author: William John Locke

Illustrator: Alec Ball

Release date: July 31, 2008 [eBook #26154]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Audrey Longhurst, Anne Storer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber’s Note: Table of Contents added.

Idols

Septimus

Derelicts

The Usurper

Where Love Is

The White Dove

Simon the Jester

A Study in Shadows

A Christmas Mystery

The Belovèd Vagabond

At the Gate of Samaria

The Morals of Marcus Ordeyne

The Demagogue and Lady Phayre

The Glory of Clementina

at the beginning of the fourth kiss

out came her father

See page 34

NEW YORK

JOHN LANE COMPANY

MCMXII

| I | THE ADVENTURE OF THE FAIR PATRONNE |

| II | THE ADVENTURE OF THE ARLÉSIENNE |

| III | THE ADVENTURE OF THE KIND MR. SMITH |

| IV | THE ADVENTURE OF THE FOUNDLING |

| V | THE ADVENTURE OF THE PIG’S HEAD |

| VI | THE ADVENTURE OF FLEURETTE |

| VII | THE ADVENTURE OF THE MIRACLE |

| VIII | THE ADVENTURE OF THE FICKLE GODDESS |

| IX | THE ADVENTURE OF A SAINT MARTIN’S SUMMER |

| At the Beginning of the Fourth Kiss Out Came Her Father | Frontispiece |

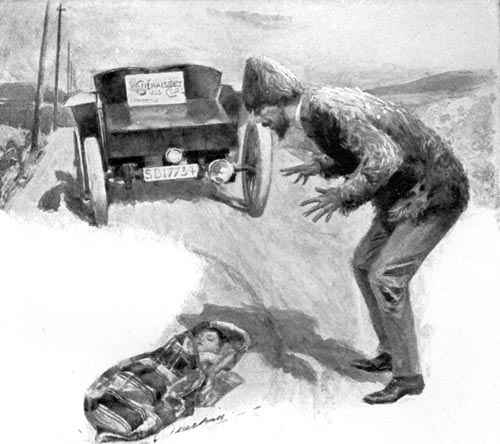

| I Had Knocked Him Down on Purpose. He Was Crippled for Life |

14 |

| Anything Less Congruous as the Bride-Elect of the Debonair Aristide Pujol it Was Impossible to Imagine |

22 |

| Had Straightway Poured His Grievances into a Feminine Ear | 32 |

| I Found Both Tyres Had Been Punctured in a Hundred Places | 40 |

| “Madame,” said Aristide, “You Are Adorable, and I Love You to Distraction” |

50 |

| “The Villain Was a Traveller in Buttons—Buttons!” | 60 |

| He Burst into Shrieks of Laughter | 64 |

| “And You!” shouted Bocardon, Falling on Aristide; “I Must Embrace You Also” |

68 |

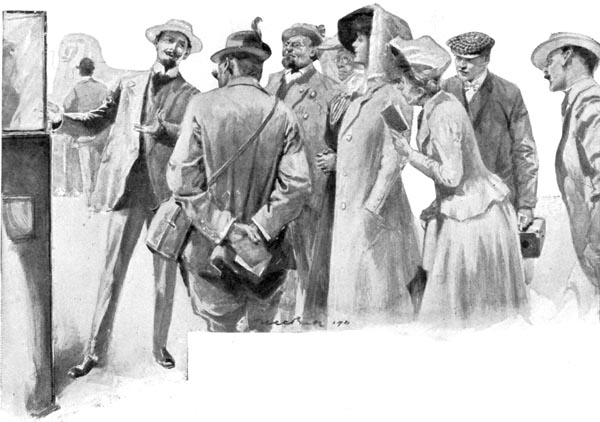

| Standing on the Arrival Platform of Euston Station | 78 |

| “Ah! the Pictures,” cried Aristide, with a Wide Sweep of His Arms | 88 |

| “I’ll Take Five Hundred Pounds,” said He, “to Stay in” | 96 |

| Between the Folds of a Blanket Peeped the Face of a Sleeping Child | 110 |

| He Demonstrated the Proper Application of the Cure | 120 |

| It is a Fearsome Thing for a Man to be Left Alone in the Dead of Night with a Young Baby |

124 |

| One of the Little Girls in Pigtails Was Holding Him, While Miss Anne Administered the Feeding-Bottle |

134 |

| He Must Have Dealt Out Paralyzing Information | 180 |

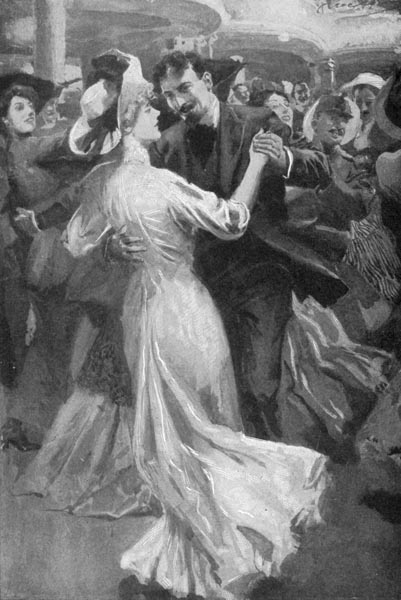

| Fleurette Danced with Aristide, as Light as an Autumn Leaf Tossed by the Wind |

188 |

| Aristide Practised His Many Queer Accomplishments | 200 |

| He Read It, and Blinked in Amazement | 208 |

| He Might as Well Have Pointed Out the Marvels of Kubla Khan’s Pleasure-Dome to a Couple of Guinea-Pigs |

216 |

| “I’ve Caught You! At Last, After Twenty Years, I’ve Caught You” | 234 |

| There He Saw a Sight Which for a Moment Paralyzed Him | 238 |

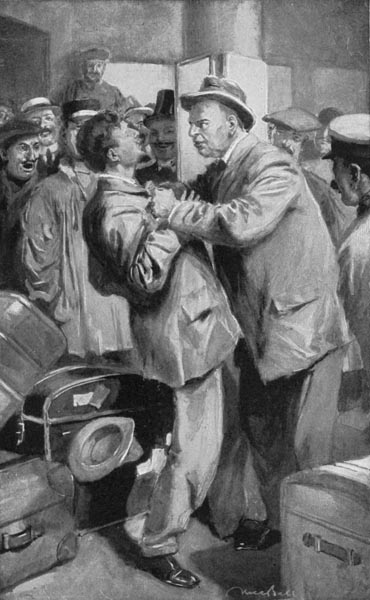

| Mr. Ducksmith Seized Him by the Lapels of His Coat | 242 |

THE ADVENTURE OF THE FAIR PATRONNE

In narrating these few episodes in the undulatory, not to say switchback, career of my friend Aristide Pujol, I can pretend to no chronological sequence. Some occurred before he (almost literally) crossed my path for the first time, some afterwards. They have been related to me haphazard at odd times, together with a hundred other incidents, just as a chance tag of association recalled them to his swift and picturesque memory. He would, indeed, make a show of fixing dates by reference to his temporary profession; but so Protean seem to have been his changes of fortune in their number and rapidity that I could never keep count of them or their order. Nor does it matter. The man’s life was as disconnected as a pack of cards.

[Pg 12] My first meeting with him happened in this wise.

I had been motoring in a listless, solitary fashion about Languedoc. A friend who had stolen a few days from anxious business in order to accompany me from Boulogne through Touraine and Guienne had left me at Toulouse; another friend whom I had arranged to pick up at Avignon on his way from Monte Carlo was unexpectedly delayed. I was therefore condemned to a period of solitude somewhat irksome to a man of a gregarious temperament. At first, for company’s sake, I sat in front by my chauffeur, McKeogh. But McKeogh, an atheistical Scotch mechanic with his soul in his cylinders, being as communicative as his own differential, I soon relapsed into the equal loneliness and greater comfort of the back.

In this fashion I left Montpellier one morning on my leisurely eastward journey, deciding to break off from the main road, striking due south, and visit Aigues-Mortes on the way.

Aigues-Mortes was once a flourishing Mediterranean town. St. Louis and his Crusaders sailed thence twice for Palestine; Charles V. and Francis I. met there and filled the place with glittering state. But now its glory has departed. The sea has receded three or four miles, and left it high and dry in the middle of bleak salt marshes, useless, dead and desolate, swept by the howling mistral and scorched by the blazing sun. The straight [Pg 13] white ribbon of road which stretched for miles through the plain, between dreary vineyards—some under water, the black shoots of the vines appearing like symmetrical wreckage above the surface—was at last swallowed up by the grim central gateway of the town, surmounted by its frowning tower. On each side spread the brown machicolated battlements that vainly defended the death-stricken place. A soft northern atmosphere would have invested it in a certain mystery of romance, but in the clear southern air, the towers and walls standing sharply defined against the blue, wind-swept sky, it looked naked and pitiful, like a poor ghost caught in the daylight.

At some distance from the gate appeared the usual notice as to speed-limit. McKeogh, most scrupulous of drivers, obeyed. As there was a knot of idlers underneath and beyond the gate he slowed down to a crawl, sounding a patient and monotonous horn. We advanced; the peasant folk cleared the way sullenly and suspiciously. Then, deliberately, an elderly man started to cross the road, and on the sound of the horn stood stock still, with resentful defiance on his weather-beaten face. McKeogh jammed on the brakes. The car halted. But the infinitesimal fraction of a second before it came to a dead stop the wing over the near front wheel touched the elderly person and down he went on the ground. I leaped from the car, to be [Pg 14] instantly surrounded by an infuriated crowd, which seemed to gather from all the quarters of the broad, decaying square. The elderly man, helped to his feet by sympathetic hands, shook his knotted fists in my face. He was a dour and ugly peasant, of splendid physique, as hard and discoloured as the walls of Aigues-Mortes; his cunning eyes were as clear as a boy’s, his lined, clean-shaven face as rigid as a gargoyle; and the back of his neck, above the low collar of his jersey, showed itself seamed into glazed irregular lozenges, like the hide of a crocodile. He cursed me and my kind healthily in very bad French and apostrophized his friends in Provençal, who in Provençal and bad French made responsive clamour. I had knocked him down on purpose. He was crippled for life. Who was I to go tearing through peaceful towns with my execrated locomotive and massacring innocent people? I tried to explain that the fault was his, and that, after all, to judge by the strength of his lungs, no great damage had been inflicted. But no. They would not let it go like that. There were the gendarmes—I looked across the square and saw two gendarmes striding portentously towards the scene—they would see justice done. The law was there to protect poor folk. For a certainty I would not get off easily.

i had knocked him down on purpose. he was crippled for life

i had knocked him down on purpose. he was crippled for life

I knew what would happen. The gendarmes would submit McKeogh and myself to a [Pg 15] procès-verbal. They would impound the car. I should have to go to the Mairie and make endless depositions. I should have to wait, Heaven knows how long, before I could appear before the juge de paix. I should have to find a solicitor to represent me. In the end I should be fined for furious driving—at the rate, when the accident happened, of a mile an hour—and probably have to pay a heavy compensation to the wilful and uninjured victim of McKeogh’s impeccable driving. And all the time, while waiting for injustice to take its course, I should be the guest of a hostile population. I grew angry. The crowd grew angrier. The gendarmes approached with an air of majesty and fate. But just before they could be acquainted with the brutal facts of the disaster a singularly bright-eyed man, wearing a hard felt hat and a blue serge suit, flashed like a meteor into the midst of the throng, glanced with an amazing swiftness at me, the car, the crowd, the gendarmes and the victim, ran his hands up and down the person of the last mentioned, and then, with a frenzied action of a figure in a bad cinematograph rather than that of a human being, subjected the inhabitants to an infuriated philippic in Provençal, of which I could not understand one word. The crowd, with here and there a murmur of remonstrance, listened to him in silence. When he had finished they hung their heads, the gendarmes shrugged their majestic [Pg 16] and fateful shoulders and lit cigarettes, and the gargoyle-visaged ancient with the neck of crocodile hide turned grumbling away. I have never witnessed anything so magical as the effect produced by this electric personage. Even McKeogh, who during the previous clamour had sat stiff behind his wheel, keeping expressionless eyes fixed on the cap of the radiator, turned his head two degrees of a circle and glanced at his surroundings.

The instant peace was established our rescuer darted up to me with the directness of a dragon-fly and shook me warmly by the hand. As he had done me a service, I responded with a grateful smile; besides, his aspect was peculiarly prepossessing. I guessed him to be about five-and-thirty. He had a clear olive complexion, black moustache and short silky vandyke beard, and the most fascinating, the most humorous, the most mocking, the most astonishingly bright eyes I have ever seen in my life. I murmured a few expressions of thanks, while he prolonged the handshake with the fervour of a long-lost friend.

“It’s all right, my dear sir. Don’t worry any more,” he said in excellent English, but with a French accent curiously tinged with Cockney. “The old gentleman’s as sound as a bell—not a bruise on his body.” He pushed me gently to the step of the car. “Get in and let me guide you to the only place where you can eat in this accursed town.”

[Pg 17] Before I could recover from my surprise, he was by my side in the car shouting directions to McKeogh.

“Ah! These people!” he cried, shaking his hands with outspread fingers in front of him. “They have no manners, no decency, no self-respect. It’s a regular trade. They go and get knocked down by automobiles on purpose, so that they can claim indemnity. They breed dogs especially and train them to commit suicide under the wheels so that they can get compensation. There’s one now—ah, sacrée bête!” He leaned over the side of the car and exchanged violent objurgation with the dog. “But never mind. So long as I am here you can run over anything you like with impunity.”

“I’m very much obliged to you,” said I. “You’ve saved me from a deal of foolish unpleasantness. From the way you handled the old gentleman I should guess you to be a doctor.”

“That’s one of the few things I’ve never been,” he replied. “No; I’m not a doctor. One of these days I’ll tell you all about myself.” He spoke as if our sudden acquaintance would ripen into life-long friendship. “There’s the hotel—the Hôtel Saint-Louis,” he pointed to the sign a little way up the narrow, old-world, cobble-paved street we were entering. “Leave it to me; I’ll see that they treat you properly.”

The car drew up at the doorway. My electric [Pg 18] friend leaped out and met the emerging landlady.

“Bonjour, madame. I’ve brought you one of my very good friends, an English gentleman of the most high importance. He will have déjeuner—tout ce qu’il y a de mieux. None of your cabbage-soup and eels and andouilles, but a good omelette, some fresh fish, and a bit of very tender meat. Will that suit you?” he asked, turning to me.

“Excellently,” said I, smiling. “And since you’ve ordered me so charming a déjeuner, perhaps you’ll do me the honour of helping me to eat it?”

“With the very greatest pleasure,” said he, without a second’s hesitation.

We entered the small, stuffy dining-room, where a dingy waiter, with a dingier smile, showed us to a small table by the window. At the long table in the middle of the room sat the half-dozen frequenters of the house, their napkins tucked under their chins, eating in gloomy silence a dreary meal of the kind my new friend had deprecated.

“What shall we drink?” I asked, regarding with some disfavour the thin red and white wines in the decanters.

“Anything,” said he, “but this piquette du pays. It tastes like a mixture of sea-water and vinegar. It produces the look of patient suffering that you see on those gentlemen’s faces. You, who are not used to it, had better not venture. It would excoriate your throat. It would dislocate your [Pg 19] pancreas. It would play the very devil with you. Adolphe”—he beckoned the waiter—“there’s a little white wine of the Côtes du Rhone——” He glanced at me.

“I’m in your hands,” said I.

As far as eating and drinking went I could not have been in better. Nor could anyone desire a more entertaining chance companion of travel. That he had thrust himself upon me in the most brazen manner and taken complete possession of me there could be no doubt. But it had all been done in the most irresistibly charming manner in the world. One entirely forgot the impudence of the fellow. I have since discovered that he did not lay himself out to be agreeable. The flow of talk and anecdote, the bright laughter that lit up a little joke, making it appear a very brilliant joke indeed, were all spontaneous. He was a man, too, of some cultivation. He knew France thoroughly, England pretty well; he had a discriminating taste in architecture, and waxed poetical over the beauties of Nature.

“It strikes me as odd,” said I at last, somewhat ironically, “that so vital a person as yourself should find scope for your energies in this dead-and-alive place.”

He threw up his hands. “I live here? I crumble and decay in Aigues-Mortes? For whom do you take me?”

[Pg 20] I replied that, not having the pleasure of knowing his name and quality, I could only take him for an enigma.

He selected a card from his letter-case and handed it to me across the table. It bore the legend:—

Aristide Pujol,

Agent.

213 bis, Rue Saint-Honoré, Paris.

“That address will always find me,” he said.

Civility bade me give him my card, which he put carefully in his letter-case.

“I owe my success in life,” said he, “to the fact that I have never lost an opportunity or a visiting-card.”

“Where did you learn your perfect English?” I asked.

“First,” said he, “among English tourists at Marseilles. Then in England. I was Professor of French at an academy for young ladies.”

“I hope you were a success?” said I.

He regarded me drolly.

“Yes—and no,” said he.

The meal over, we left the hotel.

“Now,” said he, “you would like to visit the towers on the ramparts. I would dearly love to accompany you, but I have business in the town. [Pg 21] I will take you, however, to the gardien and put you in his charge.”

He raced me to the gate by which I had entered. The gardien des remparts issued from his lodge at Aristide Pujol’s summons and listened respectfully to his exhortation in Provençal. Then he went for his keys.

“I’ll not say good-bye,” Aristide Pujol declared, amiably. “I’ll get through my business long before you’ve done your sight-seeing, and you’ll find me waiting for you near the hotel. Au revoir, cher ami.”

He smiled, lifted his hat, waved his hand in a friendly way, and darted off across the square. The old gardien came out with the keys and took me off to the Tour de Constance, where Protestants were imprisoned pell-mell after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes; thence to the Tour des Bourguignons, where I forget how many hundred Burgundians were massacred and pickled in salt; and, after these cheery exhibitions, invited me to walk round the ramparts and inspect the remaining eighteen towers of the enceinte. As the mistral, however, had sprung up and was shuddering across the high walls, I declined, and, having paid him his fee, descended to the comparative shelter of the earth.

There I found Aristide Pujol awaiting me at the corner of the narrow street in which the hotel was [Pg 22] situated. He was wearing—like most of the young bloods of Provence in winter-time—a short, shaggy, yet natty goat-skin coat, ornamented with enormous bone buttons, and a little cane valise stood near by on the kerb of the square.

He was not alone. Walking arm in arm with him was a stout, elderly woman of swarthy complexion and forbidding aspect. She was attired in a peasant’s or small shopkeeper’s rusty Sunday black and an old-fashioned black bonnet prodigiously adorned with black plumes and black roses. Beneath this bonnet her hair was tightly drawn up from her forehead; heavy eyebrows overhung a pair of small, crafty eyes, and a tuft of hair grew on the corner of a prognathous jaw. She might have been about seven-and-forty.

Aristide Pujol, unlinking himself from this unattractive female, advanced and saluted me with considerable deference.

“Monseigneur——” said he.

As I am neither a duke nor an archbishop, but a humble member of the lower automobiling classes, the high-flown title startled me.

“Monseigneur, will you permit me,” said he, in French, “to present to you Mme. Gougasse? Madame is the patronne of the Café de l’Univers, at Carcassonne, which doubtless you have frequented, and she is going to do me the honour of marrying me to-morrow.”

anything less congruous as the bride-elect of the

debonair aristide pujol it was impossible to imagine

anything less congruous as the bride-elect of the

debonair aristide pujol it was impossible to imagine

[Pg 23] The unexpectedness of the announcement took my breath away.

“Good heavens!” said I, in a whisper.

Anyone less congruous as the bride-elect of the debonair Aristide Pujol it was impossible to imagine. However, it was none of my business. I raised my hat politely to the lady.

“Madame, I offer you my sincere felicitations. As an entertaining husband I am sure you will find M. Aristide Pujol without a rival.”

“Je vous remercie, monseigneur,” she replied, in what was obviously her best company manner. “And if ever you will deign to come again to the Café de l’Univers at Carcassonne we will esteem it a great honour.”

“And so you’re going to get married to-morrow?” I remarked, by way of saying something. To congratulate Aristide Pujol on his choice lay beyond my power of hypocrisy.

“To-morrow,” said he, “my dear Amélie will make me the happiest of men.”

“We start for Carcassonne by the three-thirty train,” said Mme. Gougasse, pulling a great silver watch from some fold of her person.

“Then there is time,” said I, pointing to a little weather-beaten café in the square, “to drink a glass to your happiness.”

“Bien volontiers,” said the lady.

“Pardon, chère amie,” Aristide interposed, [Pg 24] quickly. “Unless monseigneur and I start at once for Montpellier, I shall not have time to transact my little affairs before your train arrives there.”

Parenthetically, I must remark that all trains going from Aigues-Mortes to Carcassonne must stop at Montpellier.

“That’s true,” she agreed, in a hesitating manner. “But——”

“But, idol of my heart, though I am overcome with grief at the idea of leaving you for two little hours, it is a question of four thousand francs. Four thousand francs are not picked up every day in the street. It’s a lot of money.”

Mme. Gougasse’s little eyes glittered.

“Bien sûr. And it’s quite settled?”

“Absolutely.”

“And it will be all for me?”

“Half,” said Aristide.

“You promised all to me for the redecoration of the ceiling of the café.”

“Three thousand will be sufficient, dear angel. What? I know these contractors and decorators. The more you pay them, the more abominable will they make the ceiling. Leave it to me. I, Aristide, will guarantee you a ceiling like that of the Sistine Chapel for two thousand francs.”

She smiled and bridled, so as to appear perfectly well-bred in my presence. The act of smiling [Pg 25] caused the tuft of hair on her jaw to twitch horribly. A cold shiver ran down my back.

“Don’t you think, monseigneur,” she asked, archly, “that M. Pujol should give me the four thousand francs as a wedding-present?”

“Most certainly,” said I, in my heartiest voice, entirely mystified by the conversation.

“Well, I yield,” said Aristide. “Ah, women, women! They hold up their little rosy finger, and the bravest of men has to lie down with his chin on his paws like a good old watch-dog. You agree, then, monseigneur, to my giving the whole of the four thousand francs to Amélie?”

“More than that,” said I, convinced that the swarthy lady of the prognathous jaw was bound to have her own way in the end where money was concerned, and yet for the life of me not seeing how I had anything to do with the disposal of Aristide Pujol’s property—“More than that,” said I; “I command you to do it.”

“C’est bien gentil de votre part,” said madame.

“And now the café,” I suggested, with chattering teeth. We had been standing all the time at the corner of the square, while the mistral whistled down the narrow street. The dust was driven stingingly into our faces, and the women of the place who passed us by held their black scarves over their mouths.

“Alas, monseigneur,” said Mme. Gougasse, [Pg 26] “Aristide is right. You must start now for Montpellier in the automobile. I will go by the train for Carcassonne at three-thirty. It is the only train from Aigues-Mortes. Aristide transacts his business and joins me in the train at Montpellier. You have not much time to spare.”

I was bewildered. I turned to Aristide Pujol, who stood, hands on hips, regarding his prospective bride and myself with humorous benevolence.

“My good friend,” said I in English, “I’ve not the remotest idea of what the two of you are talking about; but I gather you have arranged that I should motor you to Montpellier. Now, I’m not going to Montpellier. I’ve just come from there, as I told you at déjeuner. I’m going in the opposite direction.”

He took me familiarly by the arm, and, with a “Pardon, chère amie,” to the lady, led me a few paces aside.

“I beseech you,” he whispered; “it’s a matter of four thousand francs, a hundred and sixty pounds, eight hundred dollars, a new ceiling for the Café de l’Univers, the dream of a woman’s life, and the happiest omen for my wedded felicity. The fair goddess Hymen invites you with uplifted torch. You can’t refuse.”

He hypnotized me with his bright eyes, overpowered my will by his winning personality. He seemed to force me to desire his companionship. I [Pg 27] weakened. After all, I reflected, I was at a loose end, and where I went did not matter to anybody. Aristide Pujol had also done me a considerable service, for which I felt grateful. I yielded with good grace.

He darted back to Mme. Gougasse, alive with gaiety.

“Chère amie, if you were to press monseigneur, I’m sure he would come to Carcassonne and dance at our wedding.”

“Alas! That,” said I, hastily, “is out of the question. But,” I added, amused by a humorous idea, “why should two lovers separate even for a few hours? Why should not madame accompany us to Montpellier? There is room in my auto for three, and it would give me the opportunity of making madame’s better acquaintance.”

“There, Amélie!” cried Aristide. “What do you say?”

“Truly, it is too much honour,” murmured Mme. Gougasse, evidently tempted.

“There’s your luggage, however,” said Aristide. “You would bring that great trunk, for which there is no place in the automobile of monseigneur.”

“That’s true—my luggage.”

“Send it on by train, chère amie.”

“When will it arrive at Carcassonne?”

“Not to-morrow,” said Pujol, “but perhaps next week or the week after. Perhaps it may never come [Pg 28] at all. One is never certain with these railway companies. But what does that matter?”

“What do you say?” cried the lady, sharply.

“It may arrive or it may not arrive; but you are rich enough, chère amie, not to think of a few camisoles and bits of jewellery.”

“And my lace and my silk dress that I have brought to show your parents. Merci!” she retorted, with a dangerous spark in her little eyes. “You think one is made of money, eh? You will soon find yourself mistaken, my friend. I would give you to understand——”. She checked herself suddenly. “Monseigneur”—she turned to me with a resumption of the gracious manner of her bottle-decked counter at the Café de l’Univers—“you are too amiable. I appreciate your offer infinitely; but I am not going to entrust my luggage to the kind care of the railway company. Merci, non. They are robbers and thieves. Even if it did arrive, half the things would be stolen. Oh, I know them.”

She shook the head of an experienced and self-reliant woman. No doubt, distrustful of banks as of railway companies, she kept her money hidden in her bedroom. I pitied my poor young friend; he would need all his gaiety to enliven the domestic side of the Café de l’Univers.

The lady having declined my invitation, I expressed my regrets; and Aristide, more emotional, [Pg 29] voiced his sense of heart-rent desolation, and in a resigned tone informed me that it was time to start. I left the lovers and went to the hotel, where I paid the bill, summoned McKeogh, and lit a companionable pipe.

The car backed down the narrow street into the square and took up its position. We entered. McKeogh took charge of Aristide’s valise, tucked us up in the rug, and settled himself in his seat. The car started and we drove off, Aristide gallantly brandishing his hat and Mme. Gougasse waving her lily hand, which happened to be hidden in an ill-fitting black glove.

“To Montpellier, as fast as you can!” he shouted at the top of his lungs to McKeogh. Then he sighed as he threw himself luxuriously back. “Ah, this is better than a train. Amélie doesn’t know what a mistake she has made!”

The elderly victim of my furious entry was lounging, in spite of the mistral, by the grim machicolated gateway. Instead of scowling at me he raised his hat respectfully as we passed. I touched my cap, but Aristide returned the salute with the grave politeness of royalty.

“This is a place,” said he, “which I would like never to behold again.”

In a few moments we were whirling along the straight, white road between the interminable black vineyards, and past the dilapidated homesteads of [Pg 30] the vine-folk and wayside cafés that are scattered about this unjoyous corner of France.

“Well,” said he, suddenly, “what do you think of my fiancée?”

Politeness and good taste forbade expression of my real opinion. I murmured platitudes to the effect that she seemed to be a most sensible woman, with a head for business.

“She’s not what we in French call jolie, jolie; but what of that? What’s the good of marrying a pretty face for other men to make love to? And, as you English say, there’s none of your confounded sentiment about her. But she has the most flourishing café in Carcassonne; and, when the ceiling is newly decorated, provided she doesn’t insist on too much gold leaf and too many naked babies on clouds—it’s astonishing how women love naked babies on clouds—it will be the snuggest place in the world. May I ask for one of your excellent cigarettes?”

I handed him the case from the pocket of the car.

“It was there that I made her acquaintance,” he resumed, after having lit the cigarette from my pipe. “We met, we talked, we fixed it up. She is not the woman to go by four roads to a thing. She did me the honour of going straight for me. Ah, but what a wonderful woman! She rules that café like a kingdom; a Semiramis, a Queen Elizabeth, [Pg 31] a Catherine de’ Medici. She sits enthroned behind the counter all day long and takes the money and counts the saucers and smiles on rich clients, and if a waiter in a far corner gives a bit of sugar to a dog she spots it, and the waiter has a deuce of a time. That woman is worth her weight in thousand-franc notes. She goes to bed every night at one, and gets up in the morning at five. And virtuous! Didn’t Solomon say that a virtuous woman was more precious than rubies? That’s the kind of wife the wise man chooses when he gives up the giddy ways of youth. Ah, my dear sir, over and over again these last two or three days my dear old parents—I have been on a visit to them in Aigues-Mortes—have commended my wisdom. Amélie, who is devoted to me, left her café in Carcassonne to make their acquaintance and receive their blessing before our marriage, also to show them the lace on her dessous and her new silk dress. They are too old to take the long journey to Carcassonne. ‘My son,’ they said, ‘you are making a marriage after our own hearts. We are proud of you. Now we can die perfectly content.’ I was wrong, perhaps, in saying that Amélie has no sentiment,” he continued, after a short pause. “She adores me. It is evident. She will not allow me out of her sight. Ah, my dear friend, you don’t know what a happy man I am.”

For a brilliant young man of five-and-thirty, who [Pg 32] was about to marry a horrible Megæra ten or twelve years his senior, he looked unhealthily happy. There was no doubt that his handsome roguery had caught the woman’s fancy. She was at the dangerous age, when even the most ferro-concrete-natured of women are apt to run riot. She was comprehensible, and pardonable. But the man baffled me. He was obviously marrying her for her money; but how in the name of Diogenes and all the cynics could he manage to look so confoundedly joyful about it?

The mistral blew bitterly. I snuggled beneath the rug and hunched up my shoulders so as to get my ears protected by my coat-collar. Aristide, sufficiently protected by his goat’s hide, talked like a shepherd on a May morning. Why he took for granted my interest in his unromantic, not to say sordid, courtship I knew not; but he gave me the whole history of it from its modest beginnings to its now penultimate stage. From what I could make out—for the mistral whirled many of his words away over unheeding Provence—he had entered the Café de l’Univers one evening, a human derelict battered by buffeting waves of Fortune, and, finding a seat immediately beneath Mme. Gougasse’s comptoir, had straightway poured his grievances into a feminine ear and, figuratively speaking, rested his weary heart upon a feminine bosom. And his buffetings and grievances and [Pg 33] wearinesses? Whence came they? I asked the question point-blank.

had straightway poured his grievances into a feminine ear

had straightway poured his grievances into a feminine ear

“Ah, my dear friend,” he answered, kissing his gloved finger-tips, “she was adorable!”

“Who?” I asked, taken aback. “Mme. Gougasse?”

“Mon Dieu, no!” he replied. “Not Mme. Gougasse. Amélie is solid, she is virtuous, she is jealous, she is capacious; but I should not call her adorable. No; the adorable one was twenty—delicious and English; a peach-blossom, a zephyr, a summer night’s dream, and the most provoking little witch you ever saw in your life. Her father and herself and six of her compatriots were touring through France. They had circular tickets. So had I. In fact, I was a miniature Thomas Cook and Son to the party. I provided them with the discomforts of travel and supplied erroneous information. Que voulez-vous? If people ask you for the history of a pair of Louis XV. corsets, in a museum glass case, it’s much better to stimulate their imagination by saying that they were worn by Joan of Arc at the Battle of Agincourt than to dull their minds by your ignorance. Eh bien, we go through the châteaux of the Loire, through Poitiers and Angoulême, and we come to Carcassonne. You know Carcassonne? The great grim cité, with its battlements and bastions and barbicans and fifty towers on the hill looking over the rubbishy modern [Pg 34] town? We were there. The rest of the party were buying picture postcards of the gardien at the foot of the Tour de l’Inquisition. The man who invented picture postcards ought to have his statue on the top of the Eiffel Tower. The millions of headaches he has saved! People go to places now not to exhaust themselves by seeing them, but to buy picture postcards of them. The rest of the party, as I said, were deep in picture postcards. Mademoiselle and I promenaded outside. We often promenaded outside when the others were buying picture postcards,” he remarked, with an extra twinkle in his bright eyes. “And the result? Was it my fault? We leaned over the parapet. The wind blew a confounded mèche—what do you call it——?”

“Strand?”

“Yes—strand of her hair across her face. She let it blow and laughed and did not move. Didn’t I say she was a little witch? If there’s a Provençal ever born who would not have kissed a girl under such provocation I should like to have his mummy. I kissed her. She kept on laughing. I kissed her again. I kissed her four times. At the beginning of the fourth kiss out came her father from the postcard shop. He waited till the end of it and then announced himself. He announced himself in such ungentlemanly terms that I was forced to let the whole party, including the adorable little witch, go [Pg 35] on to Pau by themselves, while I betook my broken heart to the Café de l’Univers.”

“And there you found consolation?”

“I told my sad tale. Amélie listened and called the manager to take charge of the comptoir, and poured herself out a glass of Frontignan. Amélie always drinks Frontignan when her heart is touched. I came the next day and the next. It was pouring with rain day and night—and Carcassonne in rain is like Hades with its furnaces put out by human tears—and the Café de l’Univers like a little warm corner of Paradise stuck in the midst of it.”

“And so that’s how it happened?”

“That’s how it happened. Ma foi! When a lady asks a galant homme to marry her, what is he to do? Besides, did I not say that the Café de l’Univers was the most prosperous one in Carcassonne? I’m afraid you English, my dear friend, have such sentimental ideas about marriage. Now, we in France—— Attendez, attendez!” He suddenly broke off his story, lurched forward, and gripped the back of the front seat.

“To the right, man, to the right!” he cried excitedly to McKeogh.

We had reached the point where the straight road from Aigues-Mortes branches into a fork, one road going to Montpellier, the other to Nîmes. Montpellier being to the west, McKeogh had naturally taken the left fork.

[Pg 36] “To the right!” shouted Aristide.

McKeogh pulled up and turned his head with a look of protesting inquiry. I intervened with a laugh.

“You’re wrong in your geography, M. Pujol. Besides, there is the signpost staring you in the face. This is the way to Montpellier.”

“But, my dear, heaven-sent friend, I no more want to go to Montpellier than you do!” he cried. “Montpellier is the last place on earth I desire to visit. You want to go to Nîmes, and so do I. To the right, chauffeur.”

“What shall I do, sir?” asked McKeogh.

I was utterly bewildered. I turned to the goat-skin-clad, pointed-bearded, bright-eyed Aristide, who, sitting bolt upright in the car, with his hands stretched out, looked like a parody of the god Pan in a hard felt hat.

“You don’t want to go to Montpellier?” I asked, stupidly.

“No—ten thousand times no; not for a king’s ransom.”

“But your four thousand francs—your meeting Mme. Gougasse’s train—your getting on to Carcassonne?”

“If I could put twenty million continents between myself and Carcassonne I’d do it,” he explained, with frantic gestures. “Don’t you understand? The good Lord who is always on my side [Pg 37] sent you especially to deliver me out of the hands of that unspeakable Xantippe. There are no four thousand francs. I’m not going to meet her train at Montpellier, and if she marries anyone to-morrow at Carcassonne it will not be Aristide Pujol.”

I shrugged my shoulders.

“We’ll go to Nîmes.”

“Very good, sir,” said McKeogh.

“And now,” said I, as soon as we had started on the right-hand road, “will you have the kindness to explain?”

“There’s nothing to explain,” he cried, gleefully. “Here am I delivered. I am free. I can breathe God’s good air again. I’m not going to marry Yum-Yum, Yum-Yum. I feel ten years younger. Oh, I’ve had a narrow escape. But that’s the way with me. I always fall on my feet. Didn’t I tell you I’ve never lost an opportunity? The moment I saw an Englishman in difficulties, I realized my opportunity of being delivered out of the House of Bondage. I took it, and here I am! For two days I had been racking my brains for a means of getting out of Aigues-Mortes, when suddenly you—a Deus ex machina—a veritable god out of the machine—come to my aid. Don’t say there isn’t a Providence watching over me.”

I suggested that his mode of escape seemed somewhat elaborate and fantastic. Why couldn’t he have slipped quietly round to the railway station [Pg 38] and taken a ticket to any haven of refuge he might have fancied?

“For the simple reason,” said he, with a gay laugh, “that I haven’t a single penny piece in the world.”

He looked so prosperous and untroubled that I stared incredulously.

“Not one tiny bronze sou,” said he.

“You seem to take it pretty philosophically,” said I.

“Les gueux, les gueux, sont des gens heureux,” he quoted.

“You’re the first person who has made me believe in the happiness of beggars.”

“In time I shall make you believe in lots of things,” he retorted. “No. I hadn’t one sou to buy a ticket, and Amélie never left me. I spent my last franc on the journey from Carcassonne to Aigues-Mortes. Amélie insisted on accompanying me. She was taking no chances. Her eyes never left me from the time we started. When I ran to your assistance she was watching me from a house on the other side of the place. She came to the hotel while we were lunching. I thought I would slip away unnoticed and join you after you had made the tour des remparts. But no. I must present her to my English friend. And then—voyons—didn’t I tell you I never lost a visiting-card? Look at this?”

[Pg 39] He dived into his pocket, produced the letter-case, and extracted a card.

“Voilà.”

I read: “The Duke of Wiltshire.”

“But, good heavens, man,” I cried, “that’s not the card I gave you.”

“I know it isn’t,” said he; “but it’s the one I showed to Amélie.”

“How on earth,” I asked, “did you come by the Duke of Wiltshire’s visiting-card?”

He looked at me roguishly.

“I am—what do you call it?—a—a ‘snapper up of unconsidered trifles.’ You see I know my Shakespeare. I read ‘The Winter’s Tale’ with some French pupils to whom I was teaching English. I love Autolycus. C’est un peu moi, hein? Anyhow, I showed the Duke’s card to Amélie.”

I began to understand. “That was why you called me ‘monseigneur’?”

“Naturally. And I told her that you were my English patron, and would give me four thousand francs as a wedding present if I accompanied you to your agent’s at Montpellier, where you could draw the money. Ah! But she was suspicious! Yesterday I borrowed a bicycle. A friend left it in the courtyard. I thought, ‘I will creep out at dead of night, when everyone’s asleep, and once on my petite bicyclette, bonsoir la compagnie.’ But, would you believe it? When I had dressed and [Pg 40] crept down, and tried to mount the bicycle, I found both tyres had been punctured in a hundred places with the point of a pair of scissors. What do you think of that, eh? Ah, là, là! it has been a narrow escape. When you invited her to accompany us to Montpellier my heart was in my mouth.”

“It would have served you right,” I said, “if she had accepted.”

He laughed as though, instead of not having a penny, he had not a care in the world. Accustomed to the geometrical conduct of my well-fed fellow-Britons, who map out their lives by rule and line, I had no measure whereby to gauge this amazing and inconsequential person. In one way he had acted abominably. To leave an affianced bride in the lurch in this heartless manner was a most ungentlemanly proceeding. On the other hand, an unscrupulous adventurer would have married the woman for her money and chanced the consequences. In the tussle between Perseus and the Gorgon the odds are all in favour of Perseus. Mercury and Minerva, the most sharp-witted of the gods, are helping him all the time—to say nothing of the fact that Perseus starts out by being a notoriously handsome fellow. So a handsome rogue can generally wheedle an elderly, ugly wife into opening her money-bags, and, if successful, leads the enviable life of a fighting-cock. It was very [Pg 41] much to his credit that this kind of life was not to the liking of Aristide Pujol.

“i found both tyres had been punctured in a hundred places”

“i found both tyres had been punctured in a hundred places”

Indeed, speaking from affectionate knowledge of the man, I can declare that the position in which he, like many a better man, had placed himself was intolerable. Other men of equal sensitiveness would have extricated themselves in a more commonplace fashion; but the dramatic appealed to my rascal, and he has often plumed himself on his calculated coup de théâtre at the fork of the roads. He was delighted with it. Even now I sometimes think that Aristide Pujol will never grow up.

“There’s one thing I don’t understand,” said I, “and that is your astonishing influence over the populace at Aigues-Mortes. You came upon them like a firework—a devil-among-the-tailors—and everybody, gendarmes and victim included, became as tame as sheep. How was it?”

He laughed. “I said you were my very old and dear friend and patron, a great English duke.”

“I don’t quite see how that explanation satisfied the pig-headed old gentleman whom I knocked down.”

“Oh, that,” said Aristide Pujol, with a look of indescribable drollery—“that was my old father.”

THE ADVENTURE OF THE ARLÉSIENNE

Aristide Pujol bade me a sunny farewell at the door of the Hôtel du Luxembourg at Nîmes, and, valise in hand, darted off, in his impetuous fashion, across the Place de l’Esplanade. I felt something like a pang at the sight of his retreating figure, as, on his own confession, he had not a penny in the world. I wondered what he would do for food and lodging, to say nothing of tobacco, apéritifs, and other such necessaries of life. The idea of so gay a creature starving was abhorrent. Yet an invitation to stay as my guest at the hotel until he saw an opportunity of improving his financial situation he had courteously declined.

Early next morning I found him awaiting me in the lounge and smoking an excellent cigar. He explained that so dear a friend as myself ought to be the first to hear the glad tidings. Last evening, by the grace of Heaven, he had run across a bare acquaintance, a manufacturer of nougat at Montélimar; had spent several hours in his company, with the result that he had convinced him of two things: [Pg 43] first, that the dry, crumbling, shortbread-like nougat of Montélimar was unknown in England, where the population subsisted on a sickly, glutinous mess whereto the medical faculty had ascribed the prevalent dyspepsia of the population; and, secondly, that the one Heaven-certified apostle who could spread the glorious gospel of Montélimar nougat over the length and breadth of Great Britain and Ireland was himself, Aristide Pujol. A handsome salary had been arranged, of which he had already drawn something on account—hinc ille Colorado—and he was to accompany his principal the next day to Montélimar, en route for the conquest of Britain. In the meantime he was as free as the winds, and would devote the day to showing me the wonders of the town.

I congratulated him on his almost fantastic good fortune and gladly accepted his offer.

“There is one thing I should like to ask you,” said I, “and it is this. Yesterday afternoon you refused my cordially-offered hospitality, and went away without a sou to bless yourself with. What did you do? I ask out of curiosity. How does a man set about trying to subsist on nothing at all?”

“It’s very simple,” he replied. “Haven’t I told you, and haven’t you seen for yourself, that I never lose an opportunity? More than that. It has been my rule in life either to make friends with the Mammon of Unrighteousness—he’s a [Pg 44] muddle-headed ass is Mammon, and you can steer clear of his unrighteousness if you’re sharp enough—or else to cast my bread upon the waters in the certainty of finding it again after many days. In the case in question I took the latter course. I cast my bread a year or two ago upon the waters of the Roman baths, which I will have the pleasure of showing you this morning, and I found it again last night at the Hôtel de la Curatterie.”

In the course of the day he related to me the following artless history.

Aristide Pujol arrived at Nîmes one blazing day in July. He had money in his pocket and laughter in his soul. He had also deposited his valise at the Hôtel du Luxembourg, which, as all the world knows, is the most luxurious hotel in the town. Joyousness of heart impelled him to a course of action which the good Nîmois regard as maniacal in the sweltering July heat—he walked about the baking streets for his own good pleasure.

Aristide Pujol was floating a company, a process which afforded him as much delirious joy as the floating, for the first time, of a toy yacht affords a child. It was a company to build an hotel in Perpignan, where the recent demolition of the fortifications erected by the Emperor Charles V. had set free a vast expanse of valuable building ground on the other side of the little river on which the old [Pg 45] town is situated. The best hotel in Perpignan being one to get away from as soon as possible, owing to restriction of site, Aristide conceived the idea of building a spacious and palatial hostelry in the new part of the town, which should allure all the motorists and tourists of the globe to that Pyrenean Paradise. By sheer audacity he had contrived to interest an eminent Paris architect in his project. Now the man who listened to Aristide Pujol was lost. With the glittering eye of the Ancient Mariner he combined the winning charm of a woman. For salvation, you either had to refuse to see him, as all the architects to the end of the R’s in the alphabetical list had done, or put wax, Ulysses-like, in your ears, a precaution neglected by the eminent M. Say. M. Say went to Perpignan and returned in a state of subdued enthusiasm.

A limited company was formed, of which Aristide Pujol, man of vast experience in affairs, was managing director. But money came in slowly. A financier was needed. Aristide looked through his collection of visiting-cards, and therein discovered that of a deaf ironmaster at St. Étienne whose life he had once saved at a railway station by dragging him, as he was crossing the line, out of the way of an express train that came thundering through. Aristide, man of impulse, went straight to St. Étienne, to work upon the ironmaster’s sense of [Pg 46] gratitude. Meanwhile, M. Say, man of more sober outlook, bethought him of a client, an American millionaire, passing through Paris, who had speculated considerably in hotels. The millionaire, having confidence in the eminent M. Say, thought well of the scheme. He was just off to Japan, but would drop down to the Pyrenees the next day and look at the Perpignan site before boarding his steamer at Marseilles. If his inquiries satisfied him, and he could arrange matters with the managing director, he would not mind putting a million dollars or so into the concern. You must kindly remember that I do not vouch for the literal accuracy of everything told me by Aristide Pujol.

The question of the all-important meeting between the millionaire and the managing director then arose. As Aristide was at St. Étienne it was arranged that they should meet at a halfway stage on the latter’s journey from Perpignan to Marseilles. The Hôtel du Luxembourg at Nîmes was the place, and two o’clock on Thursday the time appointed.

Meantime Aristide had found that the deaf ironmaster had died months ago. This was a disappointment, but fortune compensated him. This part of his adventure is somewhat vague, but I gathered that he was lured by a newly made acquaintance into a gambling den, where he won the prodigious sum of two thousand francs. With this [Pg 47] wealth jingling and crinkling in his pockets he fled the town and arrived at Nîmes on Wednesday morning, a day before his appointment.

That was why he walked joyously about the blazing streets. The tide had turned at last. Of the success of his interview with the millionaire he had not the slightest doubt. He walked about building gorgeous castles in Perpignan—which, by the way, is not very far from Spain. Besides, as you shall hear later, he had an account to settle with the town of Perpignan. At last he reached the Jardin de la Fontaine, the great, stately garden laid out in complexity of terrace and bridge and balustraded parapet over the waters of the old Roman baths by the master hand to which Louis XIV. had entrusted the Garden of Versailles.

Aristide threw himself on a bench and fanned himself with his straw hat.

“Mon Dieu! it’s hot!” he remarked to another occupant of the seat.

This was a woman, and, as he saw when she turned her face towards him, an exceedingly handsome woman. Her white lawn and black silk headdress, coming to a tiny crown just covering the parting of her full, wavy hair, proclaimed her of the neighboring town of Arles. She had all the Arlésienne’s Roman beauty—the finely chiselled features, the calm, straight brows, the ripe lips, the [Pg 48] soft oval contour, the clear olive complexion. She had also lustrous brown eyes; but these were full of tears. She only turned them on him for a moment; then she resumed her apparently interrupted occupation of sobbing. Aristide was a soft-hearted man. He drew nearer.

“Why, you’re crying, madame!” said he.

“Evidently,” murmured the lady.

“To cry scalding tears in this weather! It’s too hot! Now, if you could only cry iced water there would be something refreshing in it.”

“You jest, monsieur,” said the lady, drying her eyes.

“By no means,” said he. “The sight of so beautiful a woman in distress is painful.”

“Ah!” she sighed. “I am very unhappy.”

Aristide drew nearer still.

“Who,” said he, “is the wretch that has dared to make you so?”

“My husband,” replied the lady, swallowing a sob.

“The scoundrel!” said Aristide.

The lady shrugged her shoulders and looked down at her wedding-ring, which gleamed on a slim, brown, perfectly kept hand. Aristide prided himself on being a connoisseur in hands.

“There never was a husband yet,” he added, “who appreciated a beautiful wife. Husbands only deserve harridans.”

[Pg 49] “That’s true,” said the Arlésienne, “for when the wife is good-looking they are jealous.”

“Ah, that is the trouble, is it?” said Aristide. “Tell me all about it.”

The beautiful Arlésienne again contemplated her slender fingers.

“I don’t know you, monsieur.”

“But you soon will,” said Aristide, in his pleasant voice and with a laughing, challenging glance in his bright eyes. She met it swiftly and sidelong.

“Monsieur,” she said, “I have been married to my husband for four years, and have always been faithful to him.”

“That’s praiseworthy,” said Aristide.

“And I love him very much.”

“That’s unfortunate!” said Aristide.

“Unfortunate?”

“Evidently!” said Aristide.

Their eyes met. They burst out laughing. The lady quickly recovered and the tears sprang again.

“One can’t jest with a heavy heart; and mine is very heavy.” She broke down through self-pity. “Oh, I am ashamed!” she cried.

She turned away from him, burying her face in her hands. Her dress, cut low, showed the nape of her neck as it rose gracefully from her shoulders. Two little curls had rebelled against being drawn up with the rest of her hair. The back of a dainty ear, set close to the head, was provoking in its [Pg 50] pink loveliness. Her attitude, that of a youthful Niobe, all tears, but at the same time all curves and delicious contours, would have played the deuce with an anchorite.

Aristide, I would have you remember, was a child of the South. A child of the North, regarding a bewitching woman, thinks how nice it would be to make love to her, and wastes his time in wondering how he can do it. A child of the South neither thinks nor wonders; he makes love straight away.

“Madame,” said Aristide, “you are adorable, and I love you to distraction.”

She started up. “Monsieur, you forget yourself!”

“If I remember anything else in the wide world but you, it would be a poor compliment. I forget everything. You turn my head, you ravish my heart, and you put joy into my soul.”

He meant it—intensely—for the moment.

“I ought not to listen to you,” said the lady, “especially when I am so unhappy.”

“All the more reason to seek consolation,” replied Aristide.

“Monsieur,” she said, after a short pause, “you look good and loyal. I will tell you what is the matter. My husband accuses me wrongfully, although I know that appearances are against me. He only allows me in the house on sufferance, and is taking measures to procure a divorce.”

“madame,” said aristide, “you are adorable, and i love you

to distraction”

“madame,” said aristide, “you are adorable, and i love you

to distraction”

[Pg 51] “A la bonne heure!” cried Aristide, excitedly casting away his straw hat, which an unintentional twist of the wrist caused to skim horizontally and nearly decapitate a small and perspiring soldier who happened to pass by. “A la bonne heure! Let him divorce you. You are then free. You can be mine without any further question.”

“But I love my husband,” she smiled, sadly.

“Bah!” said he, with the scepticism of the lover and the Provençal. “And, by the way, who is your husband?”

“He is M. Émile Bocardon, proprietor of the Hôtel de la Curatterie.”

“And you?”

“I am Mme. Bocardon,” she replied, with the faintest touch of roguery.

“But your Christian name? How is it possible for me to think of you as Mme. Bocardon?”

They argued the question. Eventually she confessed to the name of Zette.

Her confidence not stopping there, she told him how she came by the name; how she was brought up by her Aunt Léonie at Raphèle, some five miles from Arles, and many other unexciting particulars of her early years. Her baptismal name was Louise. Her mother, who died when she was young, called her Louisette. Aunt Léonie, a very busy woman, with no time for superfluous syllables, called her Zette.

[Pg 52] “Zette!” He cast up his eyes as if she had been canonized and he was invoking her in rapt worship. “Zette, I adore you!”

Zette was extremely sorry. She, on her side, adored the cruel M. Bocardon. Incidentally she learned Aristide’s name and quality. He was an agent d’affaires, extremely rich—had he not two thousand francs and an American millionaire in his pocket?

“M. Pujol,” she said, “the earth holds but one thing that I desire, the love and trust of my husband.”

“The good Bocardon is becoming tiresome,” said Aristide.

Zette’s lips parted, as she pointed to a black speck at the iron entrance gates.

“Mon Dieu! there he is!”

“He has become tiresome,” said Aristide.

She rose, displaying to its full advantage her supple and stately figure. She had a queenly poise of the head. Aristide contemplated her with the frankest admiration.

“One would say Juno was walking the earth again.”

Although Zette had never heard of Juno, and was as miserable and heavy hearted a woman as dwelt in Nîmes, a flush of pleasure rose to her cheeks. She too was a child of the South, and female children of the South love to be admired, no [Pg 53] matter how frankly. I have heard of Daughters of the Snows not quite averse to it. She sighed.

“I must go now, monsieur. He must not find me here with you. I am suffering enough already from his reproaches. Ah! it is unjust—unjust!” she cried, clenching her hands, while the tears again started into her eyes, and the corners of her pretty lips twitched with pain. “Indeed,” she added, “I know it has been wrong of me to talk to you like this. But que voulez-vous? It was not my fault. Adieu, monsieur.”

At the sight of her standing before him in her woeful beauty, Aristide’s pulses throbbed.

“It is not adieu—it is au revoir, Mme. Zette,” he cried.

She protested tearfully. It was farewell. Aristide darted to his rejected hat and clapped it on the back of his head. He joined her and swore that he would see her again. It was not Aristide Pujol who would allow her to be rent in pieces by the jaws of that crocodile, M. Bocardon. Faith, he would defend her to the last drop of his blood. He would do all manner of gasconading things.

“But what can you do, my poor M. Pujol?” she asked.

“You will see,” he replied.

They parted. He watched her until she became a speck and, having joined the other speck, her husband, passed out of sight. Then he set out [Pg 54] through the burning gardens towards the Hôtel du Luxembourg, at the other end of the town.

Aristide had fallen in love. He had fallen in love with Provençal fury. He had done the same thing a hundred times before; but this, he told himself, was the coup de foudre—the thunderbolt. The beautiful Arlésienne filled his brain and his senses. Nothing else in the wide world mattered. Nothing else in the wide world occupied his mind. He sped through the hot streets like a meteor in human form. A stout man, sipping syrup and water in the cool beneath the awning of the Café de la Bourse, rose, looked wonderingly after him, and resumed his seat, wiping a perspiring brow.

A short while afterwards Aristide, valise in hand, presented himself at the bureau of the Hôtel de la Curatterie. It was a shabby little hotel, with a shabby little oval sign outside, and was situated in the narrow street of the same name. Within, it was clean and well kept. On the right of the little dark entrance-hall was the salle à manger, on the left the bureau and an unenticing hole labelled salon de correspondance. A very narrow passage led to the kitchen, and the rest of the hall was blocked by the staircase. An enormous man with a simple, woe-begone fat face and a head of hair like a circular machine-brush was sitting by the bureau window in his shirt-sleeves. Aristide addressed him.

“M. Bocardon?”

[Pg 55] “At your service, monsieur.”

“Can I have a bedroom?”

“Certainly.” He waved a hand towards a set of black sample boxes studded with brass nails and bound with straps that lay in the hall. “The omnibus has brought your boxes. You are M. Lambert?”

“M. Bocardon,” said Aristide, in a lordly way, “I am M. Aristide Pujol, and not a commercial traveller. I have come to see the beauties of Nîmes, and have chosen this hotel because I have the honour to be a distant relation of your wife, Mme. Zette Bocardon, whom I have not seen for many years. How is she?”

“Her health is very good,” replied M. Bocardon, shortly. He rang a bell.

A dilapidated man in a green baize apron emerged from the dining-room and took Aristide’s valise.

“No. 24,” said M. Bocardon. Then, swinging his massive form halfway through the narrow bureau door, he called down the passage, “Euphémie!”

A woman’s voice responded, and in a moment the woman herself appeared, a pallid, haggard, though more youthful, replica of Zette, with the dark rings of sleeplessness or illness beneath her eyes which looked furtively at the world.

“Tell your sister,” said M. Bocardon, “that a [Pg 56] relation of yours has come to stay in the hotel.”

He swung himself back into the bureau and took no further notice of the guest.

“A relation?” echoed Euphémie, staring at the smiling, lustrous-eyed Aristide, whose busy brain was wondering how he could mystify this unwelcome and unexpected sister.

“Why, yes. Aristide, cousin to your good Aunt Léonie at Raphèle. Ah—but you are too young to remember me.”

“I will tell Zette,” she said, disappearing down the narrow passage.

Aristide went to the doorway, and stood there looking out into the not too savoury street. On the opposite side, which was in the shade, the tenants of the modest little shops sat by their doors or on chairs on the pavement. There was considerable whispering among them and various glances were cast at him. Presently footsteps behind caused him to turn. There was Zette. She had evidently been weeping since they had parted, for her eyelids were red. She started on beholding him.

“You?”

He laughed and shook her hesitating hands.

“It is I, Aristide. But you have grown! Pécaïre! How you have grown!” He swung her hands apart and laughed merrily in her bewildered eyes. “To [Pg 57] think that the little Zette in pigtails and short check skirt should have grown into this beautiful woman! I compliment you on your wife, M. Bocardon.”

M. Bocardon did not reply, but Aristide’s swift glance noticed a spasm of pain shoot across his broad face.

“And the good Aunt Léonie? Is she well? And does she still make her matelotes of eels? Ah, they were good, those matelotes.”

“Aunt Léonie died two years ago,” said Zette.

“The poor woman! And I who never knew. Tell me about her.”

The salle à manger door stood open. He drew her thither by his curious fascination. They entered, and he shut the door behind them.

“Voilà!” said he. “Didn’t I tell you I should see you again?”

“Vous avez un fameux toupet, vous!” said Zette, half angrily.

He laughed, having been accused of confounded impudence many times before in the course of his adventurous life.

“If I told my husband he would kill you.”

“Precisely. So you’re not going to tell him. I adore you. I have come to protect you. Foi de Provençal.”

“The only way to protect me is to prove my innocence.”

“And then?”

[Pg 58] She drew herself up and looked him straight between the eyes.

“I’ll recognize that you have a loyal heart, and will be your very good friend.”

“Mme. Zette,” cried Aristide, “I will devote my life to your service. Tell me the particulars of the affair.”

“Ask M. Bocardon.” She left him, and sailed out of the room and past the bureau with her proud head in the air.

If Aristide Pujol had the rapturous idea of proving the innocence of Mme. Zette, triumphing over the fat pig of a husband, and eventually, in a fantastic fashion, carrying off the insulted and spotless lady to some bower of delight (the castle in Perpignan—why not?), you must blame, not him, but Provence, whose sons, if not devout, are frankly pagan. Sometimes they are both.

M. Bocardon sat in his bureau, pretending to do accounts and tracing columns of figures with a huge, trembling forefinger. He looked the picture of woe. Aristide decided to bide his opportunity. He went out into the streets again, now with the object of killing time. The afternoon had advanced, and trees and buildings cast cool shadows in which one could walk with comfort; and Nîmes, clear, bright city of wide avenues and broad open spaces, instinct too with the grandeur that was Rome’s, is an idler’s Paradise. Aristide knew it [Pg 59] well; but he never tired of it. He wandered round the Maison Carrée, his responsive nature delighting in the splendour of the Temple, with its fluted Corinthian columns, its noble entablature, its massive pediment, its perfect proportions; reluctantly turned down the Boulevard Victor Hugo, past the Lycée and the Bourse, made the circuit of the mighty, double-arched oval of the Arena, and then retraced his steps. As he expected, M. Bocardon had left the bureau. It was the hour of absinthe. The porter named M. Bocardon’s habitual café. There, in a morose corner of the terrace, Aristide found the huge man gloomily contemplating an absurdly small glass of the bitters known as Dubonnet. Aristide raised his hat, asked permission to join him, and sat down.

“M. Bocardon,” said he, carefully mixing the absinthe which he had ordered, “I learn from my fair cousin that there is between you a regrettable misunderstanding, for which I am sincerely sorry.”

“She calls it a misunderstanding?” He laughed mirthlessly. “Women have their own vocabulary. Listen, my good sir. There is infamy between us. When a wife betrays a man like me—kind, indulgent, trustful, who has worshipped the ground she treads on—it is not a question of misunderstanding. It is infamy. If she had anywhere to lay her head, I would turn her out of doors to-night. But she has not. You, who are her relative, know I [Pg 60] married her without a dowry. You alone of her family survive.”

It was on the tip of Aristide’s impulsive tongue to say that he would be only too willing to shelter her, but prudently he refrained.

“She has broken my heart,” continued Bocardon.

Aristide asked for details of the unhappy affair. The large man hesitated for a moment and glanced suspiciously at his companion; but, fascinated by the clear, luminous eyes, he launched with Southern violence into a whirling story. The villain was a traveller in buttons—buttons! To be wronged by a traveller in diamonds might have its compensations—but buttons! Linen buttons, bone buttons, brass buttons, trouser buttons! To be a traveller in the inanity of buttonholes was the only lower degradation. His name was Bondon—he uttered it scathingly, as if to decline from a Bocardon to a Bondon was unthinkable. This Bondon was a regular client of the hotel, and such a client!—who never ordered a bottle of vin cacheté or coffee or cognac. A contemptible creature. For a long time he had his suspicions. Now he was certain. He tossed off his glass of Dubonnet, ordered another, and spoke incoherently of the opening and shutting of doors, whisperings, of a dreadful incident, the central fact of which was a glimpse of Zette gliding wraith-like down a corridor. Lastly, there was the culminating proof, a letter found that [Pg 61] morning in Zette’s room. He drew a crumpled sheet from his pocket and handed it to Aristide.

“the villain was a traveller in buttons—buttons!”

“the villain was a traveller in buttons—buttons!”

It was a crude, flaming, reprehensible, and entirely damning epistle. Aristide turned cold, shivering at the idea of the superb and dainty Zette coming in contact with such abomination. He hated Bondon with a murderous hate. He drank a great gulp of absinthe and wished it were Bondon’s blood. Great tears rolled down Bocardon’s face, and gathering at the ends of his scrubby moustache dripped in splashes on the marble table.

“I loved her so tenderly, monsieur,” said he.

The cry, so human, went straight to Aristide’s heart. A sympathetic tear glistened in his bright eyes. He was suddenly filled with an immense pity for this grief-stricken, helpless giant. An odd feminine streak ran through his nature and showed itself in queer places. Impulsively he stretched out his hand.

“You’re going?” asked Bocardon.

“No. A sign of good friendship.”

They gripped hands across the table. A new emotion thrilled through the facile Aristide.

“Bocardon, I devote myself to you,” he cried, with a flamboyant gesture. “What can I do?”

“Alas, nothing,” replied the other, miserably.

“And Zette? What does she say to it all?”

The mountainous shoulders heaved with a shrug. “She denies everything. She had never seen the [Pg 62] letter until I showed it to her. She did not know how it came into her room. As if that were possible!”

“It’s improbable,” said Aristide, gloomily.

They talked. Bocardon, in a choking voice, told the simple tale of their married happiness. It had been a love-match, different from the ordinary marriages of reason and arrangement. Not a cloud since their wedding-day. They were called the turtle-doves of the Rue de la Curatterie. He had not even manifested the jealousy justifiable in the possessor of so beautiful a wife. He had trusted her implicitly. He was certain of her love. That was enough. They had had one child, who died. Grief had brought them even nearer each other. And now this stroke had been dealt. It was a knife being turned round in his heart. It was agony.

They walked back to the hotel together. Zette, who was sitting by the desk in the bureau, rose and, without a word or look, vanished down the passage. Bocardon, with a great sigh, took her place. It was dinner-time. The half-dozen guests and frequenters filled for a moment the little hall, some waiting to wash their hands at the primitive lavabo by the foot of the stairs. Aristide accompanied them into the salle à manger, where he dined in solemn silence. The dinner over he went out again, passing by the bureau where Bocardon, in its dim [Pg 63] recesses, was eating a sad meal brought to him by the melancholy Euphémie. Zette, he conjectured, was dining in the kitchen. An atmosphere of desolation impregnated the place, as though a corpse were somewhere in the house.

Aristide drank his coffee at the nearest café in a complicated state of mind. He had fallen furiously in love with the lady, believing her to be the victim of a jealous husband. In an outburst of generous emotion he had taken the husband to his heart, seeing that he was a good man stricken to death. Now he loved the lady, loved the husband, and hated the villain Bondon. What Aristide felt, he felt fiercely. He would reconcile these two people he loved, and then go and, if not assassinate Bondon, at least do him some bodily injury. With this idea in his head, he paid for his coffee and went back to the hotel.

He found Zette taking her turn at the bureau, for clients have to be attended to, even in the most distressing circumstances. She was talking to a new arrival, trying to smile a welcome. Aristide, loitering near, watched her beautiful face, to which the perfect classic features gave an air of noble purity. His soul revolted at the idea of her mixing herself up with a sordid wretch like Bondon. It was unbelievable.

“Eh bien?” she said as soon as they were alone.

[Pg 64] “Mme. Zette, to-day I called your husband a scoundrel and a crocodile. I was wrong. I find him a man with a beautiful nature.”

“You needn’t tell me that, M. Aristide.”

“You are breaking his heart, Mme. Zette.”

“And is he not breaking mine? He has told you, I suppose. Am I responsible for what I know nothing more about than a babe unborn? You don’t believe I am speaking the truth? Bah! And your professions this afternoon? Wind and gas, like the words of all men.”

“Mme. Zette,” cried Aristide, “I said I would devote my life to your service, and so I will. I’ll go and find Bondon and kill him.”

He watched her narrowly, but she did not grow pale like a woman whose lover is threatened with mortal peril. She said dryly:—

“You had better have some conversation with him first.”

“Where is he to be found?”

She shrugged her shoulders. “How do I know? He left by the early train this morning that goes in the direction of Tarascon.”

“Then to-morrow,” said Aristide, who knew the ways of commercial travellers, “he will be at Tarascon, or at Avignon, or at Arles.”

“I heard him say that he had just done Arles.”

“Tant mieux. I shall find him either at Tarascon or Avignon. And by the Tarasque of [Pg 65] Sainte-Marthe, I’ll bring you his head and you can put it up outside as a sign and call the place the ‘Hôtel de la Tête Bondon.’”

he burst into shrieks of laughter

he burst into shrieks of laughter

Early the next morning Aristide started on his quest, without informing the good Bocardon of his intentions. He would go straight to Avignon, as the more likely place. Inquiries at the various hotels would soon enable him to hunt down his quarry; and then—he did not quite know what would happen then—but it would be something picturesque, something entirely unforeseen by Bondon, something to be thrillingly determined by the inspiration of the moment. In any case he would wipe the stain from the family escutcheon. By this time he had convinced himself that he belonged to the Bocardon family.

The only other occupant of the first-class compartment was an elderly Englishwoman of sour aspect. Aristide, his head full of Zette and Bondon, scarcely noticed her. The train started and sped through the sunny land of vine and olive.

They had almost reached Tarascon when a sudden thought hit him between the eyes, like the blow of a fist. He gasped for a moment, then he burst into shrieks of laughter, kicking his legs up and down and waving his arms in maniacal mirth. After that he rose and danced. The sour-faced Englishwoman, in mortal terror, fled into the corridor. She must have reported Aristide’s behaviour [Pg 66] to the guard, for in a minute or two that official appeared at the doorway.

“Qu’est-ce qu’il y a?”

Aristide paused in his demonstrations of merriment. “Monsieur,” said he, “I have just discovered what I am going to do to M. Bondon.”

Delight bubbled out of him as he walked from the Avignon Railway Station up the Cours de la République. The wretch Bondon lay at his mercy. He had not proceeded far, however, when his quick eye caught sight of an object in the ramshackle display of a curiosity dealer’s. He paused in front of the window, fascinated. He rubbed his eyes.

“No,” said he; “it is not a dream. The bon Dieu is on my side.”

He went into the shop and bought the object. It was a pair of handcuffs.

At a little after three o’clock the small and dilapidated hotel omnibus drove up before the Hôtel de la Curatterie, and from it descended Aristide Pujol, radiant-eyed, and a scrubby little man with a goatee beard, pince-nez, and a dome-like forehead, who, pale and trembling, seemed stricken with a great fear. It was Bondon. Together they entered the little hall. As soon as Bocardon saw his enemy his eyes blazed with fury, and, uttering an inarticulate roar, he rushed out of the bureau with clenched fists murderously uplifted. The [Pg 67] terrified Bondon shrank into a corner, protected by Aristide, who, smiling like an angel of peace, intercepted the onslaught of the huge man.

“Be calm, my good Bocardon, be calm.”

But Bocardon would not be calm. He found his voice.

“Ah, scoundrel! Miscreant! Wretch! Traitor!” When his vocabulary of vituperation and his breath failed him, he paused and mopped his forehead.

Bondon came a step or two forward.

“I know, monsieur, I have all the wrong on my side. Your anger is justifiable. But I never dreamt of the disastrous effect of my acts. Let me see her, my good M. Bocardon, I beseech you.”

“Let you see her?” said Bocardon, growing purple in the face.

At this moment Zette came running up the passage.

“What is all this noise about?”

“Ah, madame!” cried Bondon, eagerly, “I am heart-broken. You who are so kind—let me see her.”

“Hein?” exclaimed Bocardon, in stupefaction.

“See whom?” asked Zette.

“My dear dead one. My dear Euphémie, who has committed suicide.”

“But he’s mad!” shouted Bocardon, in his great voice. “Euphémie! Euphémie! Come here!”

At the sight of Euphémie, pale and shivering [Pg 68] with apprehension, Bondon sank upon a bench by the wall. He stared at her as if she were a ghost.

“I don’t understand,” he murmured, faintly, looking like a trapped hare at Aristide Pujol, who, debonair, hands on hips, stood a little way apart.

“Nor I, either,” cried Bocardon.

A great light dawned on Zette’s beautiful face. “I do understand.” She exchanged glances with Aristide. He came forward.

“It’s very simple,” said he, taking the stage with childlike exultation. “I go to find Bondon this morning to kill him. In the train I have a sudden inspiration, a revelation from Heaven. It is not Zette but Euphémie that is the bonne amie of Bondon. I laugh, and frighten a long-toothed English old maid out of her wits. Shall I get out at Tarascon and return to Nîmes and tell you, or shall I go on? I decide to go on. I make my plan. Ah, but when I make a plan, it’s all in a second, a flash, pfuit! At Avignon I see a pair of handcuffs. I buy them. I spend hours tracking that animal there. At last I find him at the station about to start for Lyon. I tell him I am a police agent. I let him see the handcuffs, which convince him. I tell him Euphémie, in consequence of the discovery of his letter, has committed suicide. There is a procès-verbal at which he is wanted. I summon him to accompany me in the name of the law—and there he is.”

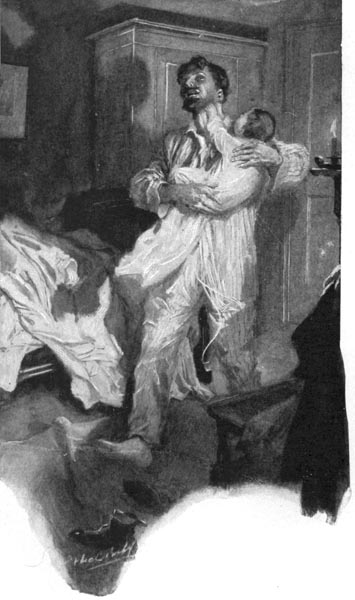

“and you!” shouted bocardon, falling on aristide; “i must

embrace you also”

“and you!” shouted bocardon, falling on aristide; “i must

embrace you also”

[Pg 69] “Then that letter was not for my wife?” said Bocardon, who was not quick-witted.

“But, no, imbecile!” cried Aristide.

Bocardon hugged his wife in his vast embrace. The tears ran down his cheeks.

“Ah, my little Zette, my little Zette, will you ever pardon me?”

“Oui, je te pardonne, gros jaloux,” said Zette.

“And you!” shouted Bocardon, falling on Aristide; “I must embrace you also.” He kissed him on both cheeks, in his expansive way, and thrust him towards Zette.