Title: My New Home

Author: Mrs. Molesworth

Illustrator: L. Leslie Brooke

Release date: August 14, 2008 [eBook #26310]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Annie McGuire, Lindy Walsh and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note

Spelling, punctuation and inconsistencies in the original book have been retained.

CHAPTER I | |

| Windy Gap | 1 |

CHAPTER II | |

| At the Foot of the Ladder | 15 |

CHAPTER III | |

| One and Seven | 28 |

CHAPTER IV | |

| New Friends and a Plan | 43 |

CHAPTER V | |

| A Happy Day | 58 |

CHAPTER VI | |

| 'Waving View' | 71 |

CHAPTER VII | |

| The Beginning of Troubles | 83 |

CHAPTER VIII | |

| Two Letters | 96 |

CHAPTER IX | |

| A Great Change | 111 |

CHAPTER X | |

| No. 29 Chichester Square | 125 |

CHAPTER XI | |

| An Arrival | 139 |

CHAPTER XII | |

| A Catastrophe | 153 |

CHAPTER XIII | |

| Harry | 168 |

CHAPTER XIV | |

| Kezia's Counsel | 183 |

CHAPTER XV | |

| 'Happy ever since' | 195 |

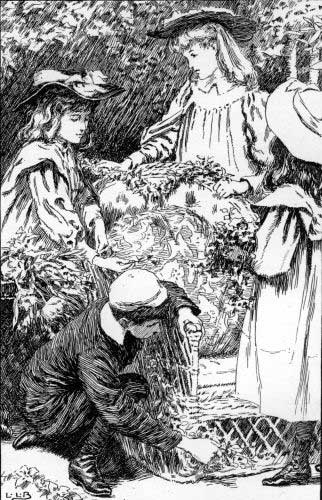

| 'I'd like to know your sisters that are as little as me's names.' | Frontispiece |

| Grandmamma's chair was still waiting to be decorated, so the next hour was spent very happily. | 67 |

| 'I do wonder why they are so late'. | 82 |

| A nice-looking oldish man came forward and bowed respectfully to grandmamma. | 126 |

| It was the portrait of a young girl. | 139 |

| Up rushed two or three ... men, Cousin Cosmo the first. | 160 |

| It was all uphill too. | 173 |

My name is Helena, and I am fourteen past. I have two other Christian names; one of them is rather queer. It is 'Naomi.' I don't mind having it, as I am never called by it, but I don't sign it often because it is such an odd name. My third name is not uncommon. It is just 'Charlotte.' So my whole name is 'Helena Charlotte Naomi Wingfield.'

I have never been called by any short name, like 'Lena,' or 'Nellie.' I think the reason must be that I am an only child. I have never had any big brother to shout out 'Nell' all over the house, or dear baby sisters who couldn't say 'Helena' properly. And what seems still sadder than having no brothers or sisters, I have never had a mother that I could remember. For mamma died when I was not much[Pg 2] more than a year old, and papa six months before that.

But my history has not been as sad as you might think from this. I was very happy indeed when I was quite a little child. Till I was nine years old I really did not know what troubles were, for I lived with grandmamma, and she made up to me for everything I had not got: we loved each other so very dearly.

I will tell you about our life.

Grandmamma was not at all the sort of person most children think of when they hear of a grandmother in a story. She was not old, with white hair and spectacles and always a shawl on, even in the house, and very old-fashioned in her ways. She did wear caps, at least I think she always did, for, of course, she was not young. But her hair was very nicely done under them, and they were pretty fluffy things. She made them herself, and she made a great many other things herself—for me too. For, you will perhaps wonder more than ever at my saying what a happy child I was, when I tell you that we were really very poor.

I cannot tell you exactly how much or how little we had to live upon, and most children would not[Pg 3] understand any the better if I did. For a hundred pounds a year even, sounds a great deal to a child, and yet it is very little indeed for one lady by herself to live upon, and of course still less for two people. And I don't think we had much more than that. Grandmamma told me when I grew old enough to understand better, that when I first came to live with her, after both papa and mamma were dead, and she found that there was no money for me—that was not poor papa's fault; he had done all that could be done, but the money was lost by other people's wrong-doing—well, as I was saying, when grandmamma found how it was, she thought over about doing something to make more. She was very clever in many ways; she could speak several languages, and she knew a lot about music, though she had given up playing, and she might have begun a school as far as her cleverness went. But she had no savings to furnish a large enough house with, and she did not know of any pupils. She could not bear the thought of parting with me, otherwise she might perhaps have gone to be some grand sort of housekeeper, which even quite, quite ladies are sometimes, or she might have joined somebody in having a shop. But after a lot of thinking, she settled she would[Pg 4] rather try to live on what she had, in some quiet, healthy, country place, though I believe she did earn some money by doing beautiful embroidery work, for I remember seeing her make lovely things which were never used in our house. This could not have gone on for long, however, as granny's eyes grew weak, and then I think she did no sewing except making our own clothes.

Now I must tell you about our home. It was quite a strange place to grandmamma when we first came there, but I can never feel as if it had been so. For it was the first place I can remember, as I was only a year old, or a little more—and children very seldom remember anything before they are three—when we settled down at Windy Gap.

That was the name of our cottage. It is a nice breezy name, isn't it? though it does sound rather cold. And in some ways it was cold, at least it was windy, and quite suited its name, though at some seasons of the year it was very calm and sheltered. Sheltered on two sides it always was, for it stood in a sort of nest a little way up the Middlemoor Hills, with high ground on the north and on the east, so that the only winds really to be feared could never do us much harm. It was more a nest than a 'gap,'[Pg 5] for inside, it was so cosy, so very cosy, even in winter. The walls were nice and thick, built of rather gloomy-looking, rough gray stone, and the windows were deep—deep enough to have window-seats in them, where granny and I used often to sit with our books or work, as the inner part of the rooms, owing to the shape of the windows, was rather dark, and the rooms of course were small.

We had a little drawing-room, which we always sat in, and a still smaller dining-room, which was very nice, though in reality it was more a kitchen than a dining-room. It had a neat kitchen range and an oven, and some things had to be cooked there, though there was another little kitchen across the passage where our servant Kezia did all the messy work—peeling potatoes, and washing up, and all those sorts of things, you know. The dining-room-kitchen was used as little as possible for cooking, and grandmamma was so very, very neat and particular that it was almost as pretty and cosy as the drawing-room.

Upstairs there were three bedrooms—a good-sized one for grandmamma, a smaller one beside it for me, and a still smaller one with a rather sloping roof for Kezia. The house is very easy to understand, you[Pg 6] see, for it was just three and three, three upstairs rooms over three downstairs ones. But there was rather a nice little entrance hall, or closed-in porch, and the passages were pretty wide. So it did not seem at all a poky or stuffy house though it was so small. Indeed, one could scarcely fancy a 'Windy Gap Cottage' anything but fresh and airy, could one?

I was never tired of hearing the story of the day that grandmamma first came to Middlemead to look for a house. She told it me so often that I seem to know all about it just as if I had been with her, instead of being a stupid, helpless little baby left behind with my nurse—Kezia was my nurse then—while poor granny had to go travelling all about, house-hunting by herself!

What made her first think of Middlemead she has never been able to remember. She did not know any one there, and she had never been there in her life. She fancies it was that she had read in some book or advertisement perhaps, that it was so very healthy, and dear grandmamma's one idea was to make me as strong as she could; for I was rather a delicate child. But for me, indeed, I don't think she would have cared where she lived, or to live at all, except that she was so very good.[Pg 7]

'As long as any one is left alive,' she has often said to me, 'it shows that there is something for them to be or to do in the world, and they must try to find out what it is.'

But there was not much difficulty for grandmamma to find out what her principal use in the world was to be! It was all ready indeed—it was poor, little, puny, delicate, helpless me!

So very likely it was as she thought—just the hearing how splendidly healthy the place was—that made her travel down to Middlemead in those early spring days, that first sad year after mamma's death, to look for a nest for her little fledgling. She arrived there in pretty good spirits; she had written to a house-agent and had got the names of two or three 'to let' houses, which she at once tramped off from the station to look at, for she was very anxious not to spend a penny more than she could help. But, oh dear, how her spirits went down! The houses were dreadful; one was a miserable sort of genteel cottage in a row of others all exactly the same, with lots of messy-looking children playing about in the untidy strips of garden in front. That would certainly not do, for even if the house itself had been the least nice, grandmamma felt sure I[Pg 8] would catch measles and scarlet-fever and hooping-cough every two or three days! The next one was a still more genteel 'semi-detached' villa, but it was very badly built, the walls were like paper, and it faced north and east, and had been standing empty, no doubt, for these reasons, for years. It would not do. Then poor granny plodded back to the house agent's again. He isn't only a house agent, he has a stationer's and bookseller's shop, and his name is Timbs. I know him quite well. He is rather a nice man, and though she was a stranger of course, he seemed sorry for grandmamma's disappointment.

'There are several very good little houses that I am sure you would like,' he said to her, 'and one or two of them are very small—but it is the rent. For though Middlemead is scarcely more than a village it is much in repute for its healthiness, and the rents are rising.'

'What are the rents of the smallest of the houses you speak of?' grandmamma asked.

'Forty pounds is the cheapest,'.Mr. Timbs answered, 'and the situation of that is not so good. Rather low and chilly in winter, and somewhat lonely.'

'I don't mind about the loneliness,' said grandmamma,[Pg 9] 'but a low or damp situation would never do.'

Mr. Timbs was looking over his lists as she spoke. Her words seemed to strike him, and he suddenly peered up through his spectacles.

'You don't mind about loneliness,' he repeated. 'Then I wonder——' and he turned over the leaves of his book quickly. 'There is another house to let,' he said; 'to tell the truth I had forgotten about it, for it has never been to let unfurnished before; and it would be considered too lonely for all the year round by most people.'

'Are there no houses near?' asked grandmamma. 'I don't fancy Middlemead is the sort of place where one need fear burglars, and besides,' she went on with a little smile, 'we should not have much of value to steal. The silver plate that I have I shall leave for the most part in London. But in case of sudden illness or any alarm of that kind, I should not like to be out of reach of everybody.'

'There are two or three small cottages close to the little house I am thinking of,' said Mr. Timbs, 'and the people in them are very respectable. I leave the key with one of them.'

Then he went on to tell grandmamma exactly[Pg 10] where it was, how to get there, and all about it, and with every word, dear granny said her heart grew lighter and lighter. She really began to hope she had found a nest for her poor little homeless bird—that was me, you understand—especially when Mr. Timbs finished up by saying that the rent was only twelve pounds a year, one pound a month. And she had made up her mind to give as much as twenty pounds if she could find nothing nice and healthy for less.

She looked at her watch; yes, there was still time to go to see Windy Gap Cottage and yet get back to the station in time for the train she had fixed to go back by—that is to say, if she took a fly. She has often told me how she stood and considered about that fly. Was it worth while to go to the expense? Yes, she decided it was, for after all if she found nothing to suit us at Middlemead she would have to set off on her travels again to house-hunt somewhere else. It would be penny wise and pound foolish to save that fly.

Mr. Timbs seemed pleased when she said she would go at once—I suppose so many people go to house agents asking about houses which they never take, that when anybody comes who is quite in earnest they feel like a fisherman when he has really[Pg 11] hooked a fish. He grew quite eager and excited and said he would go with the lady himself, if she would allow him to take a seat beside the driver to save time. And of course granny was very glad for him to come.

It was getting towards evening when she saw Windy Gap for the first time, and it happened to be a very still evening—the name hardly seemed suitable, and she said so to Mr. Timbs. He smiled and shook his head and answered that he only hoped if she did come there to live that she would not find the name too suitable. Still, though there was a good deal of wind to be heard, he went on to explain that the cottage was, as I have already said, well sheltered on the cold sides, and also well and strongly built.

'None of your "paper-mashy," one brick thick, run-up-to-tumble-down houses,' said Mr. Timbs with satisfaction, which was certainly quite true.

The end of it was, as of course you know already, that grandmamma fixed to take it. She talked it all over with Mr. Timbs, who 'made notes,' and promised to write to her about one or two things that could not be settled at once, and then 'with a very thankful heart,' as she always says when she talks of that day, she drove away again off to the station.

The sun was just beginning to think about setting[Pg 12] when she walked down the little steep garden path and a short way over the rough, hill cart-track—for nothing on wheels can come quite close up to the gate of Windy Gap—and already she could see what a beautiful show there was going to be over there in the west. She stood still for a minute to look at it.

'Yes, madam,' said old Timbs, though she had not spoken, 'yes, that is a sight worth adding a five pound note on to the rent of the cottage for, in my opinion. The sunsets here are something wonderful, and there's no house better placed for seeing them than Windy Gap. "Sunset View" it might have been called, I have often thought.'

'I can quite believe what you say,' grandmamma replied, 'and I am very glad to have had a glimpse of it on this first visit.'

Many and many a time since then have we sat or stood together there, granny and I, watching the sun's good-night. I think she must have begun to teach me to look at it while I was still almost a baby. For these wonderful sunsets seem mixed up in my mind with the very first things I can remember. And still more with the most solemn and beautiful thoughts I have ever had. I always fancied when I was very tiny that if only we could have pushed away the[Pg 13] long low stretch of hills which prevented our seeing the very last of the dear sun, we should have had an actual peep into heaven, or at least that we should have seen the golden gates leading there. And I never watched the sun set without sending a message by him to papa and mamma. Only in my own mind, of course. I never told grandmamma about it for years and years. But I did feel sure he went there every night and that the beautiful colours had to do with that somehow.

Grandmamma felt as if the lovely glow in the sky was a sort of good omen for our life at Windy Gap, and she felt happier on her journey back in the railway that evening than she had done since papa and mamma died.

She told Kezia and me all about it—you will be amused at my saying she told me, for of course I was only a baby and couldn't understand. But she used to fancy I did understand a little, and she got into the way of talking to me when we were alone together especially, almost as if she was thinking aloud. I cannot remember the time when she didn't talk to me 'sensibly,' and perhaps that made me a little old for my age. Granny says I used to grow quite grave when she talked seriously, and that I[Pg 14] would laugh and crow with pleasure when she seemed bright and happy. And this made her try more than anything else to be bright and happy.

Dear, dear grandmamma—how very, exceedingly unselfish she was! For I now see what a really sad life most people would have thought hers. All her dearest ones gone; her husband, her son and her son's wife—mamma, I mean—whom she had loved nearly, if not quite as much, as if she had been her own daughter; and she left behind when she was getting old, to take care of one tiny little baby girl—and to be so poor, too. I don't think even now I quite understand her goodness, but every day I am getting to see it more and more, even though at one time I was both ungrateful and very silly, as you will hear before you come to the end of this little history.

And now that I have explained as well as I can about grandmamma and myself, and how and why we came to live in the funny little gray stone cottage perched up among the Middlemoor Hills, I will go on with what I can remember myself; for up till now, you see, all I have written has been what was told to me by other people, especially of course by granny.[Pg 15]

No, perhaps I was rather hasty in saying I could now go straight on about what I remember myself. There are still a few things belonging to the time before I can remember, which I had better explain now, to keep it all in order.

I have spoken of grandmamma as being alone in the world, and so she was—as far as having no one very near her—no other children, and not any brothers or sisters of her own. And on my mother's side I had no relations worth counting. Mamma was an only child, and her father had married again after her mother died, and then, some years after, he died himself, and mamma's half-brothers and sisters had never even seen her, as they were out in India. So none of her relations have anything to do with my story or with me.

But grandmamma had one nephew whom she had[Pg 16] been very fond of when he was a boy, and whom she had seen a good deal of, as he and papa were at school together. His name was not the same as ours, for he was the son of a sister of grandpapa's, not of a brother. It was Vandeleur, Mr. Cosmo Vandeleur.

He was abroad when our great troubles came—I forget where, for though he was not a soldier, he moved about the world a good deal to all sorts of out-of-the-way places, and very often for months and months together, grandmamma never heard anything about him. And one of the things that made her still lonelier and sadder when we first came to Windy Gap was that he had never answered her letters, or written to her for a very long time.

She thought it was impossible that he had not got her letters, and almost more impossible that he had not seen poor papa's death in some of the newspapers.

And as it happened he had seen it and he had written to her once, anyway, though she never got the letter. He had troubles of his own that he did not say very much about, for he had married a good while ago, and though his wife was very nice, she was very, very delicate.

Still, his name was familiar to me. I can always[Pg 17] remember hearing grandmamma talk of 'Cosmo,' and when she told me little anecdotes of papa as a boy, his cousin was pretty sure to come into the story.

And Kezia used to speak of him too—'Master Cosmo,' she always called him. For she had been a young under-servant of grandmamma's long ago, when grandpapa was alive and before the money was lost.

That is one thing I want to say—that though Kezia was our only servant, she was not at all common or rough. She turned herself into what is called 'a maid-of-all-work,' from being my nurse, just out of love for granny and me. And she was very good and very kind. Since I have grown older and have seen more of other children and how they live, I often think how much better off I was than most, even though my home was only a cottage and we lived so simply, and even poorly, in some ways. Everything was so open and happy about my life. I was not afraid of anybody or anything. And I have known children who, though their parents were very rich and they lived very grandly, had really a great deal to bear from cross or unkind nurses or maids, whom they were frightened to complain of. For children, unless they are very spoilt, are not so[Pg 18] ready to complain as big people think. I had nothing to complain of, but if I had had anything, it would have been easy to tell grandmamma all about it at once; it would never have entered my head not to tell her. She knew everything about me, and I knew everything about her that it was good for me to know while I was still so young—more, perhaps, than some people would think a child should know—about our not having much money and needing to be careful, and things like that. But it did not do me any harm. Children don't take that kind of trouble to heart. I was proud of being treated sensibly, and of feeling that in many little ways I could help her as I could not have done if she had not explained.

And if ever there was anything she did not tell me about, even the keeping it back was done in an open sort of way. Granny made no mysteries. She would just say simply—

'I cannot tell you, my dear,' or 'You could not understand about it at present.'

So that I trusted her—'always,' I was going to say, but, alas, there came a time when I did not trust her enough, and from that great fault of mine came all the troubles I ever had.[Pg 19]

Now I will go straight on.

Have you ever looked back and tried to find out what is really the very first thing you can remember? It is rather interesting—now and then the b—no, I don't mean to speak of them till they come properly into my story—now and then I try to look back like that, and I get a strange feeling that it is all there, if only I could keep hold of the thread, as it were. But I cannot; it melts into a mist, and the very first thing I can clearly remember stands out the same again.

This is it.

I see myself—those looking backs always are like pictures; you seem to be watching yourself, even while you feel it is yourself—I see myself, a little trot of a girl, in a pale gray merino frock, with a muslin pinafore covering me nearly all over, and a broad sash of Roman colours, with a good deal of pale blue in it (I have the sash still, so it isn't much praise to my memory to know all about it), tied round my waist, running fast down the short steep garden path to where granny is standing at the gate. I go faster and faster, beginning to get a little frightened as I feel I can't stop myself. Then granny calls out—

'Take care, take care, my darling,' and all in a[Pg 20] minute I feel safe—caught in her arms, and held close. It is a lovely feeling. And then I hear her say—

'My little girlie must not try to run so fast alone. She might have fallen and hurt herself badly if granny had not been there.'

There is to me a sort of parable, or allegory, in that first thing I can remember, and I think it will seem to go on and fit into all my life, even if I live to be as old as grandmamma is now. It is like feeling that there are always arms ready to keep us safe, through all the foolish and even wrong things we do—if only we will trust them and run into them. I hope the children who may some day read this won't say I am preaching, or make fun of it. I must tell what I really have felt and thought, or else it would be a pretence of a story altogether. And this first remembrance has always stayed with me.

Then come the sunsets. I have told you a little about them, already. I must often have looked at them before I can remember, but one specially beautiful has kept in my mind because it was on one of my birthdays.

I think it must have been my third birthday, though granny is half inclined to think it was my fourth. I don't, because if it had been my fourth[Pg 21] I should remember some things between it and my third birthday, and I don't—nothing at all, between the running into granny's arms, which she too remembers, and which was before I was three, there is nothing I can get hold of, till that lovely sunset.

I was sitting at the window when it began. I was rather tired—I suppose I had been excited by its being my birthday, for dear granny always contrived to give me some extra pleasures on that day—and I remember I had a new doll in my lap, whom I had been undressing to be ready to be put to bed with me. I almost think I had fallen asleep for a minute or two, for it seems as if all of a sudden I had caught sight of the sky. It must have been particularly beautiful, for I called out—

'Oh, look, look, they're lighting all the beauty candles in heaven. Look, Dollysweet, it's for my birfday.'

Grandmamma was in the room and she heard me. But for a minute or two she did not say anything, and I went on talking to Dolly and pretending or fancying that Dolly talked back to me.

Then granny came softly behind me and stood looking out too. I did not know she was there till I heard her saying some words to herself. Of[Pg 22] course I did not understand them, yet the sound of them must have stayed in my ears. Since then I have learnt the verses for myself, and they always come back to me when I see anything very beautiful—like the trees and the flowers in summer, or the stars at night, and above all, lovely sunsets.

But all I heard then was just—

'Good beyond compare,

If thus Thy meaner works are fair'—

and all I remembered was—

'... beyond compare,

... are fair.'

I said them over and over to myself, and a funny fancy grew out of them, when I got to understand what 'beyond' meant. I took it into my head that 'compare' was the name of the hills, which, as I have said, came between us and the horizon on the west, and prevented our seeing the last of the sunset.

And I used to make wonderful fairy stories to myself about the country beyond or behind those hills—the country I called 'Compare,' where something, or everything—for I had lost the words just before, was 'fair' in some marvellous way I could not even picture to myself. For I soon learnt to know that 'fair' meant beautiful—I think I learnt it[Pg 23] first from some of the old fairy stories grandmamma used to tell me when we sat at work.

That evening she took me up in her arms and kissed me.

'The sun is going to bed,' she said to me, 'and so must my little Helena, even though it is her birthday.'

'And so must Dollysweet,' I said. I always called that doll 'Dollysweet,' and I ran the words together as if it was one name.

'Yes, certainly,' said granny.

Then she took my hand and I trotted upstairs beside her, carrying Dollysweet, of course. And there, up in my little room—I had already begun to sleep alone in my little room, though the door was always left open between it and grandmamma's—there, at the ending of my birthday was another lovely surprise. For, standing in a chair beside my cot was a bed for my doll—so pretty and cosy-looking.

Wasn't it nice of granny? I never knew any one like her for having new sort of ideas. It made me go to bed so very, very happily, and that is not always the case the night of a birthday. I have known children who, even when they are pretty big,[Pg 24] cry themselves to sleep because the long-looked-for day is over.

It did not matter to me that my dolly's bed had cost nothing—except, indeed, what was far more really precious than money—granny's loving thought and work. It was made out of a strong cardboard box—the lid fastened to the box, standing up at one end like the head part of a French bed. And it was all beautifully covered with pink calico, which grandmamma had had 'by her.' Granny was rather old-fashioned in some ways, and fond of keeping a few odds and ends 'by her.' And over that again, white muslin, all fruzzled on, that had once been pinafores of mine, but had got too worn to use any more in that way.

There were little blankets, too, worked round with pink wool, and little sheets, and everything—all made out of nothing but love and contrivance!

It was so delightful to wake the next morning and see Dollysweet in her nest beside me. She slept there every night for several years, and I am afraid after some time she slept there a good deal in the day also. For I gave up playing with dolls rather young—playing with a doll, I should say. I found it more interesting to have lots of little ones,[Pg 25] or of things that did instead of dolls—dressed-up chessmen did very well at one time—that I could make move about and act and be anything I wanted them to be, more easily than one or two big dolls.

Still I always took care of Dollysweet. I never neglected her or let her get dirty and untidy, though in time, of course, her pink-and-white complexion faded into pallid yellow, and her bright hair grew dull, and, worst of all—after that I never could bear to look at her—one of her sky-blue eyes dropped, not out, but into her hollow head.

Poor old Dollysweet!

The day after my third birthday grandmamma began to teach me to read. I couldn't have remembered that it was that very day, but she has told me so. I had very short lessons, only a quarter of an hour, I think, but though she was very kind, she was very strict about my giving my attention while I was at them. She says that is the part that really matters with a very little child—the learning to give attention. Not that it would signify if the actual things learnt up to six or seven came to be forgotten—so long as a child knows how to learn.

At first I liked my lessons very much, though I[Pg 26] must have been a rather tiresome child to teach. For I would keep finding out likenesses in the letters, which I called 'little black things,' and I wouldn't try to learn their names. Grandmamma let me do this for a few days, as she thought it would help me to distinguish them, but when she found that every day I invented a new set of likenesses, she told me that wouldn't do.

'You may have one likeness for each,' she said, 'but only if you really try to remember its name too.'

And I knew, by the sound of her voice, that she meant what she said.

So I set to work to fix which of the 'likes,' as I called them, I would keep.

'A' had been already a house with a pointed roof, and a book standing open on its two sides, and a window with curtains drawn at the top, and the wood of the sash running across half-way, and a good many other things which you couldn't see any likeness to it in, I am sure. But just as I was staring at it again, I saw old Tanner, who lived in one of the cottages below our house, settling his double ladder against a wall.

I screamed out with pleasure[Pg 27]—

'I'll have Tan's ladder,' I said, and so I did. 'A' was always Tan's ladder after that. And a year or two later, when I heard some one speak of the 'ladder of learning,' I felt quite sure it had something to do with the opened-out ladder with the bar across the middle.

After all, I have had to get grandmamma's help for some of these baby memories. Still, as I can remember the little events I have now written down, I suppose it is all right.[Pg 28]

I will go on now to the time I was about seven years old. 'Baby' stories are interesting to people who know the baby, or the person that once was the baby, but I scarcely think they are very interesting to people who have never seen you or never will, or, if they do, would not know it was you!

All these years we had gone on quietly living at Windy Gap, without ever going away. Going away never came into my head, and if dear grandmamma sometimes wished for a little change—and, indeed, I am sure she must have done—she never spoke of it to me. Now and then I used to hear other children, for there were a few families living near us, whose little boys and girls I very occasionally played with, speak of going to the sea-side in the summer, or to stay with uncles and aunts or other relations in London in the winter, to see the pantomimes and[Pg 29] the shops. But it never struck me that anything of that sort could come in my way, not more than it ever entered my imagination that I could become a princess or a gipsy or anything equally impossible.

Happy children are made like that, I think, and a very good thing it is for them. And I was a very happy child.

We had our troubles, troubles that even had she wished, grandmamma could not have kept from me. And I do not think she did wish it. She knew that though the background of a child's life should be contented and happy, it would not be true teaching or true living to let it believe any life can be without troubles.

One trouble was a bad illness I had when I was six—though this was really more of a trouble to granny and Kezia than to me. For I did not suffer much pain. Sometimes the illnesses that frighten children's friends the most do not hurt the little people themselves as much as less serious things.

This illness came from a bad cold, and it might have left me delicate for always, though happily it didn't. But it made granny anxious, and after I got better it was a long time before she could feel easy-minded about letting me go out without being[Pg 30] tremendously wrapped up, and making sure which way the wind was, and a lot of things like that, which are rather teasing.

I might not have given in as well as I did had it not happened that the winter which came after my illness was a terribly severe one, and my own sense—for even between six and seven children can have some common sense—told me that nothing would be easier than to get a cough again if I didn't take care. So on the whole I was pretty good.

But those months of anxiety and the great cold were very trying for grandmamma. Her hair got quite, quite white during them.

These severe winters do not come often at Middlemoor; not very often, at least. We had two of them during the time we lived there, 'year in and year out,' as Kezia called it. But between them we had much milder ones, one or two quite wonderfully mild, and others middling—nothing really to complain of. Still, a very tiny cottage house standing by itself is pretty cold during the best of winters, even though the walls were thick. And in wet or stormy days one does get tired of very small rooms and few of them.

But the year that followed that bitter winter[Pg 31] brought a pleasant little change into my life—the first variety of the kind that had come to me. I made real acquaintance at last with some other children.

This was how it began.

I was seven, a little past seven, at the time.

One morning I had just finished my lessons, which of course took more than a quarter of an hour now, and was collecting my books together, to put them away, when I heard a knock at the front door.

I was in the drawing-room—generally, especially in winter, I did my lessons in the dining-room. For we never had two fires at once, and for that reason we sat in the dining-room in the morning if it was cold, though granny was most particular always to have a fire in the drawing-room in the afternoon. I think now it was quite wonderful how she managed about things like that, never to fall into irregular or untidy ways, for as people grow old they find it difficult to be as active and energetic as is easy for younger ones. It was all for my sake, and every day I feel more and more grateful to her for it.

Never once in my life do I remember going into the dining-room to dinner without first meeting grandmamma in the drawing-room, when a glance[Pg 32] would show her if my face and hands had been freshly washed and my hair brushed and my dress tidy, and upstairs again would I be sent in a twinkling if any of these matters were amiss.

But this morning I had had my lessons in the drawing-room; to begin with, it was not winter now, but spring, and not a cold spring either; and in the second place, Kezia had been having a baking of pastry and cakes in the dining-room oven, and granny knew my lessons would have fared badly if my attention had been disturbed every time the cakes had to be seen to.

I was collecting my books, I said, to carry them into the other room, where there was a little shelf with a curtain in front on purpose for them, as we only kept our nicest books in the drawing-room, when this rat-a-tat knock came to the door.

I was very surprised. It was so seldom any one came to the front door in the morning, and, indeed, not often in the afternoon either, and this knock sounded sharp and important somehow. Though I was still quite a little girl I knew it would vex grandmamma if I tried to peep out to see who it was—it was one of the things she would have said 'no lady should ever do'—and I could not bear her[Pg 33] to think I ever forgot how even a very small lady should behave.

The only thing I could do was to look out of the side window, not that I could see the door from there, but I had a good view of the road where it passed the short track, too rough to call a road, leading to our own little gate.

No cart or carriage could come nearer than that point; the tradesmen from Middlemoor always stopped there and carried up our meat or bread or whatever it was—not very heavy basketfuls, I suspect—to the kitchen door, and I used to be very fond of standing at this window, watching the unpacking from the carts.

There was no cart there to-day, but what was there nearly took my breath away.

'Oh, grandmamma,' I called out, quite forgetting that by this time Kezia must have opened the door; 'oh, grandmamma, do look at the lovely carriage and ponies.'

Granny did not answer. She had not heard me, for she was in the dining-room, as I might have known. But I had got into the habit of calling to her whenever I was pleased or excited, and generally, somehow or other, she managed to hear. And[Pg 34] I could not leave the window, I was so engrossed by what I saw.

There was a girl in the carriage, to me she seemed a grown-up lady. She was sitting still, holding the reins. But I did not see the figure of another lady which by this time had got hidden by the house, as she followed the little groom whom she had sent on to ask if Mrs. Wingfield was at home, meaning at first, to wait till he came back. I heard her afterwards explaining to grandmamma that the boy was rather deaf and she was afraid he had not heard her distinctly, so she had come herself.

And while I was still gazing at the carriage and the ponies, the drawing-room door, already a little ajar, was pushed wide open and I heard Kezia saying she would tell Mrs. Wingfield at once.

'Mrs. Nestor; you heard my name?' said some one in a pleasant voice.

I turned round.

There stood a tall lady in a long dark green cloak, she had a hat on, not a bonnet, and I just thought of her as another lady, not troubling myself as to whether she was younger or older than the one in the carriage, though actually she was her mother.[Pg 35]

I was not shy. It sounds contradictory to say so, but still there is truth in it. I had seen too few people in my life to know anything about shyness. And all I ever had had to do with were kind and friendly. And I remembered 'my manners,' as old-fashioned folk say.

I clambered down from the window-seat, and stroked my pinafore, which had got ruffled up, and came forward towards the lady, holding out my hand. I had no need to go far, for she had come straight in my direction.

'Well, dear?' she said, and again I liked her voice, though I did not exactly think about it, 'and are you Mrs. Wingfield's little girl?'

'My name is Helena Charlotte Naomi Wingfield,' I said, very gravely and distinctly, 'and grandmamma is Mrs. Wingfield.'

Mrs. Nestor was smiling still more by this time, but she smiled in a nice way that did not at all give me any feeling that she was making fun of what I said.

'And how old are you, my dear?—let me see, you have so many names! which are you called by, or have you any short name?'

I shook my head.[Pg 36]

'No, only "girlie," and that is just for grandmamma to say. I am always called "Helena."'

'It is a very pretty name,' said my new friend. 'And how old are you, Helena?'

'I am past seven,' I said. 'My birthday comes in the spring, in March. Have you any little girls, and are any of them seven? I would like to know some little girls as big as me.'

'I have lots,' said Mrs. Nestor. 'One of them is in the pony-carriage outside. I daresay you can see her from the window.'

I think my face must have fallen.

'Oh,' I said, disappointedly. 'She's a lady.'

'No, indeed,' said Mrs. Nestor, now laughing outright; 'if you knew her, or when you know her, as I hope you will soon, I'm afraid you will think her much more of a tomboy than a lady. Sharley is only eleven, though she is tall. Her name is Charlotte, like one of yours, but we call her Sharley; we spell it with an "S" to prevent people calling her "Charley," for she is boyish enough already, I am afraid. Then I have three girls younger—nine, six, and three, and two boys of——'

I was so interested—my eyes were very wide open, and I shouldn't wonder if my mouth was too—that[Pg 37] for once in my life I was almost sorry to see grandmamma, who at that moment opened the door and came in.

'I hope Helena has been a good hostess?' she said, after she had shaken hands with Mrs. Nestor, whom she had met before once or twice. 'We have been having a cake baking this morning, and I was just giving some directions about a special kind of gingerbread we want to try.'

'I should apologise for coming in the morning,' said Mrs. Nestor, but grandmamma assured her it was quite right to have chosen the morning. 'Helena and I go out in the afternoon whenever the weather is fine enough, and I should have been sorry to miss you. Now, my little girl, you may run off to Kezia. Say good-bye to Mrs. Nestor.'

I felt very disappointed, but I was accustomed to obey at once. But Mrs. Nestor read the disappointment in my eyes: that was one of the nice things about her. She was so 'understanding.'

She turned to grandmamma.

'One of my daughters is in the pony-carriage,' she said. 'Would you allow Helena to go out to her? She would be pleased to see your garden, I am sure.'[Pg 38]

'Certainly,' said grandmamma. 'Put on your hat and jacket, Helena, and ask Miss'—she had caught sight of the girl from the window and saw that she was pretty big—'Miss Nestor to walk about with you a little.'

I flew off—too excited to feel at all timid about making friends by myself.

'Call her Sharley,' said Mrs. Nestor, as I left the room. 'She would not know herself by any other name.'

In a minute or two I was running down the garden-path. When I found myself fairly out at the gate, and within a few steps of the girl, I think a feeling of shyness did come over me, though I did not myself understand what it was. I hung back a little and began to wonder what I should say. I had so seldom spoken to a child belonging to my own rank in life. And I had not often spoken to any of the poorer children about, as there happened to be none in the cottages near us, and grandmamma was perhaps a little too anxious about me, too afraid of my catching any childish illness. She says herself that she thinks she was. But of course I am now so strong and big that it makes it rather different.[Pg 39]

I had not much time left in which to grow shy, however. As soon as the girl saw that I was plainly coming towards her she sprang out of the carriage.

'Has mother sent you to fetch me?' she said.

I looked at her. Now that she was out of the carriage and standing, I could see that she was not as tall as grandmamma, or as her own mother, and that her frock was a good way off the ground. And her hair was hanging down her back. Still she seemed to me almost a grown-up lady.

I am afraid her first impression of me must have been that I was extremely stupid. For I went on staring at her for a moment or two before I answered. She was indeed opening her lips to repeat the question when I at last found my voice.

'I don't know,' I said. And if she did not think me stupid before I spoke, she certainly must have done so when I did.

'I don't know,' I repeated, considering over what her question exactly meant. 'No, I don't think it was fetching you. I was to ask you—would you like to walk round our garden? And p'raps—your mamma was going to tell me all your names, but grandmamma told me to run away. I'd like to know your sisters that are as little as me's names.'[Pg 40]

I remember exactly what I said, for Sharley has often told me since how difficult it was for her not to burst out laughing at the funny way I spoke. But tomboy though she was in some respects, she had a very tender heart, and like her mother she was quick at understanding. So she answered quite soberly—

'Thank you. I should like very much to walk round your garden—though running would be even nicer. I'm not very fond of walking if I can run, and you have got such jolly steep paths and banks.'

I eyed the steep paths doubtfully.

'You hurt yourself a good deal if you run too fast down the paths,' I said. 'The stones are so sharp.'

Sharley laughed.

'You speak from experience,' she said. 'That grass bank would be lovely for tobogganing.'

'I don't know what that is,' I replied.

'We'll show you if you come to see us at home,' she said. 'But I suppose I'd better not try anything like that to-day. You want to know my sisters' names? They are Anna and Valetta and Baby——'

'Never mind about Baby,' I interrupted, rather abruptly, I fear. 'How big is Anna, and—the other one?'

Sharley stood still and looked me well over.[Pg 41]

'Do you really mean "big"?' she said, 'or "old"? Anna is nine and Val is six; but as for bigness—Anna is nearly as tall as I am, and Val is a good bit bigger than you.'

I felt and looked nearly ready to cry.

'And I'm past seven,' I said, 'I wish I wasn't so little. It's like being a baby, and I don't care for babies.'

'Never mind,' replied Sharley consolingly, 'you needn't be at all babyish because you're little. One of our boys is very little, but he's not a bit of a baby. I'm sure Val will like to play with you, and so will Anna—and all of us, for that matter.'

I began to think Sharley a very nice girl. I put my hand in hers confidingly.

'I'd like to come,' I said, 'and I'd like to play that funny name down the grass-bank here, if you'll show me how.'

'All right,' she said. 'We'll have to ask leave, I suppose. But you haven't told me your name yet. The children are sure to ask me.'

I repeated it—or them—solemnly.

'"Charlotte"—that's my name,' Sharley remarked.

'I'm never called it,' I said. 'I'm always called Helena.'[Pg 42]

Sharley looked rather surprised.

'Fancy!' she said. 'We all call each other by short names and nicknames and all kinds of absurd names. Anna is generally Nan, and the boys are Pert and Quick—at least those are the names that have lasted longest. I daresay it's partly because they are just a little like their real names—Percival and Quintin.'

'What a great many of you there are!' I said, but Sharley took my remark in perfectly good part, even though I went on to add—'It's like the baker's children—I counted them once, but I couldn't get them right; sometimes they came to nine and sometimes to eleven.'

'Do you mean the baker's on the way to High Middlemoor?' said Sharley. 'Oh yes, it must be them—papa calls them the baker's dozen always. No, we're not as many as that. We are only seven—us four girls, and Pert and Quick, and Jerry, our big brother, who's at school. Dear me, it must be dull to be only one!'

Just then we heard the voices of grandmamma and Sharley's mother coming towards us. And a minute or two later the pony-carriage drove away again, Sharley nodding back friendly farewells.[Pg 43]

I stood looking after it as long as it was in sight. I felt quite strange, almost a little dazed, as if I had more than I could manage to think over in my head. Grandmamma, who was standing behind me, put her hand on my shoulder.

I looked up at her, and I saw that her face seemed pleased.

'Is that a nice lady, grandmamma?' I said.

I do not quite know why I asked about Sharley's mother in that way, for I felt sure she was nice. I think I wanted grandmamma to help me to arrange my ideas a little.

'Very nice, dear,' she said. 'Did you not think she spoke very kindly?'

'Yes, I did, grandmamma,' I replied. I had a rather 'old-fashioned' way of speaking sometimes, I think.[Pg 44]

'And her little girl—well, she is not a little girl, exactly, is she?—seems very bright and kind too,' grandmamma went on.

'Yes,' I replied, but then I hesitated. Grandmamma wanted to find out what I was thinking.

'You don't seem quite sure about it?' she said.

'Yes, grandmamma. She is a very kind girl, but she made me feel funny. She has such a lot of brothers and sisters, and she says it must be so dull to be only one. Grandmamma, is it dull to be only one?'

Grandmamma did not smile at my odd way of asking her what I could have told myself, better than any one else. A little sad look came over her face.

'I hope not, dear,' she answered. 'My little girl does not find her life dull?'

I shook my head.

'I love you, grandmamma, and I love Kezia, but I don't know about "dull" and things like that. I think Sharley thinks I'm a very stupid little girl, grandmamma.'

And all of a sudden, greatly to dear granny's surprise and still more to her distress, I burst into tears.

She led me back into the house, and was very kind to me. But she did not say very much. She[Pg 45] only told me that she was sure Sharley did not think anything but what was nice and friendly about me, and that I must not be a fanciful little woman. And then she sent me to Kezia, who had kept an odd corner of her pastry for me to make into stars and hearts and other shapes with her cutters, as I was very fond of doing. So that very soon I was quite bright and happy again.

But in her heart granny was saying that it would be a very good thing for me to have some companions of my own age, to prevent my getting fanciful and unchildlike, and, worst of all, too much taken up with myself.

A few days after that, grandmamma told me that the three Nestor girls were coming twice a week to read French with her. I think I have said already that grandmamma was very clever, very clever indeed, and that she knew several foreign languages. She had been a great deal in other countries when grandpapa was alive, and she could speak French beautifully. So I wasn't surprised, and only very pleased when she told me about Sharley and her sisters. For I was too little to understand what any one else would have known in a moment, that dear granny was going to do this to make a little[Pg 46] more money. My illness and all the things she had got for me—even the having more fires—had cost a good deal that last winter, and she had asked the vicar of our village to let her know if he heard of any family wanting French or German lessons for their children.

This was the reason of Mrs. Nestor's call, and it was because they were going to settle about the French lessons that grandmamma had sent me out of the room. It was not till long afterwards that I understood all about it.

Just now I was very pleased.

'Oh, how nice!' I said, 'and may I play with them after the lessons are done, do you think, grandmamma? And will they ask me to go to their house to tea sometimes? Sharley said they would—at least she nearly said it.'

'I daresay you will go to their house some day. I think Mrs. Nestor is very kind, and I am sure she would ask you if she thought it would please you,' said grandmamma. But then she stopped a little. 'I want you to understand, Helena dear, that these children are coming here really to learn French. So you must not think about playing with them just at first, that must be as their mother likes.'[Pg 47]

Grandmamma did not say what she felt in her own mind—that she would not wish to seem to try to make acquaintance with the Nestors, who were very rich and important people, through giving lessons to their children. For she was proud in a right way—no, I won't call it proud—I think dignified is a better word.

But Mrs. Nestor was too nice herself not to see at once the sort of person grandmamma was. She was almost too delicate in her feelings, for she was so afraid of seeming to be in the least condescending or patronising to us, that she kept back from showing us as much kindness as she would have liked to do. So it never came about that we grew very intimate with the family at Moor Court—that was the name of their home—I really saw more of the three girls at our own little cottage than in their own grand house.

But as I go on with my story you will see that there was a reason for my telling about them, and about how we came to know them, rather particularly.

The French lessons began the next week. Sharley and her sisters used to come together, sometimes walking with a maid, sometimes driving over in a little pony-cart—not the beautiful carriage[Pg 48] with the two ponies; that was their mother's—but what is called a governess-cart, in which they drove a fat old fellow called Bunch, too fat and lazy to be up to much mischief. When they drove over they brought a young groom with them, but their governess very seldom came. I think Mrs. Nestor thought it would be pleasanter for granny to give the lessons without a grown-up person being there, and Sharley said their governess used that time to give the two boys Latin lessons. Mrs. Nestor would have been very glad if grandmamma would have agreed to teach Pert and Quick French too, but granny did not think she could spare time for it, though a year or two later when Percival had gone to school she did let Quick join what we called the second class.

I should have explained that though I could not read or write French at all well, I could speak it rather nicely, as grandmamma had taken great pains to accustom me to do so since I was quite little.

I think she had a feeling that I might have to be a governess or something of the kind when I was grown-up, and that made her very anxious about my lessons from the beginning of them. And though things have turned out quite differently from that,[Pg 49] I have always been very glad that I was well taught from the first. It is such a comfort to me now that I am really growing big to be able to show grandmamma that I am not far back for my age compared with other girls.

Sharley was the first class all by herself, and Nan and Vallie were the second. I did not do any lessons with them, but after each class had had half an hour's teaching we had conversation for another half hour, and when the conversation time began I was always sent for. Grandmamma had asked Mrs. Nestor if she would like that, and Mrs. Nestor was very pleased.

We had great fun at the 'conversation.' You can scarcely believe what comical things the little girls said when they first began to try to talk. Grandmamma sometimes laughed till the tears came into her eyes—I do love to see her laugh—and I laughed too, partly, I think, because she did, for the funny things they said did not seem quite so funny to me, of course, as to a big person.

But altogether the French lessons were very nice and brought some variety into our lives. I think granny and I looked forward to them as much as the Nestor children did.[Pg 50]

Grandmamma's birthday happened to come about a fortnight after they began. I told Sharley about it one day when she was out in the garden with me, while her sisters were at their lesson. We used to do that way sometimes, only we had to promise to speak French all the time, so that I really had a little to do with teaching them as well as grandmamma, and to tease me, on these occasions Sharley would call me 'mademoiselle,' and make Nan and Vallie do the same. They used in turn, you see, to be with me while Sharley was with granny.

It was rather difficult to make her understand about grandmamma's birthday, I remember, for she could scarcely speak French at all then, and at last she burst out into English, for she got very interested about it.

'I'll tell Mrs. Wingfield we have been talking English,' she said, 'and I'll tell her it was all my fault. But I must understand what you are saying.'

'It's about grandmamma's birthday,' I said. 'I do so want to make a plan for it.'

Sharley's eyes sparkled. She loved making plans, and so did Vallie, who was very quick and bright about everything, while Nan was rather a sleepy little girl, though exceedingly good-natured. I don't think I ever knew her speak crossly.[Pg 51]

'I heard something about "fête,"' said Sharley, 'about fête and grandmamma. Why do you call her birthday her "fête"?'

'I didn't,' I replied. '"Fête" doesn't generally mean birthday—it means something else, something about a saint's day. I said I wanted to "fêter" dear granny on her birthday, and I wondered what I could do. Last year I worked a little case in that stiff stuff with holes in, to keep stamps in, and Kezia made tea-cakes. But I can't think of anything I can work for her this year, and tea-cakes are only tea-cakes,' and I sighed.

'Don't look so unhappy,' said Sharley, 'we'll plan. We're rather short of plans just now, and we always like to have some on hand for first thing in the morning—Val and I do at least. Nan never wakes up properly. Leave it to us, Helena, and the next time we come I'll tell you what we've thought of.'

I had a good deal of faith in Sharley's cleverness in some things, already, though I can't say that it shone out in speaking French. So I promised to wait to see what she and Vallie thought of.

When we went in we told grandmamma that we had been speaking English. I made it up into very[Pg 52] good French, and Sharley said it, which pleased granny.

'And what was it you were so eager about that you couldn't wait to say it, or hear it in French?' she asked Sharley.

We had not expected this, and Sharley got rather red.

'It's a secret,' she blurted out.

Grandmamma looked just a little grave.

'I am not very fond of secrets,' she said. 'And Helena has never had any.'

'Oh yes, I have, grandmamma,' I said. I did not mean to contradict rudely, and I don't think it sounded like that, though it looks rather rude written down. 'I had one this time last year—don't you remember?—about your little stamp case.'

Granny's face brightened up. It did not take very quick wits to put two and two together, and to guess from what I said that the secret had to do with her birthday. And Sharley was too anxious for grandmamma not to be vexed, to think about her having partly guessed the secret.

'Ah, well!' said granny, 'I think I can trust you both.'

'Yes, indeed, you may,' said Sharley. 'There's[Pg 53] nothing about mischief in it, and the only secrets mother's ever been vexed with me about had to do with mischief.'

'Sharley dressed up a pillow to tumble on Pert's head from the top of his door, once,' said Nan in her slow solemn voice, 'and he screamed and screamed.'

'It was because he was such a boasty boy, about never being frightened,' said Sharley, getting rather red. 'But I never did it again. And this secret is quite, quite a different kind.'

I felt very eager for the next French day, as we called them, to come, to hear what Sharley had thought of. I told Kezia about it, and then I almost wished I had not, for she said she did not know that grandmamma would be pleased at my talking about her birthday and 'such like' to strangers.

I think Kezia forgot sometimes how very little a girl I still was. I did not understand what she meant, and all I could say was that the three girls were not strangers to me. Afterwards I saw what Kezia was thinking of, she was afraid of the Nestors sending some present to grandmamma, and that, she would not have liked.

But Mrs. Nestor was too good and sensible for anything of that kind.[Pg 54]

When Sharley and Nan and Vallie came the next time, I ran to meet them, full of anxiety to know if they had made any 'plans.' They all looked very important, but rather to my disappointment the first thing Sharley said to me was—

'Don't ask us yet, Helena. We've promised mother not to tell. She's going to come to fetch us to-day, and she's made a lovely plan, but first she has to speak about it to your grandmamma.'

'Then it won't be a surprise,' I began, but Vallie answered before I had time to say any more.

'Oh yes, it will. There's to be a surprise mixed up with it, and we're to settle that part of it all ourselves—you and us.'

I found it very difficult to keep to speaking French that day, I can tell you. And it seemed as if the hour and a half of lessons spread out to twice as much before Mrs. Nestor at last came.

We all ran out into the garden while she went in to talk to grandmamma. They were very kind and did not keep us long waiting, and soon we heard granny calling us from the window. Her face was quite pleased and smiling. I saw in a moment that she was not going to say I should not have spoken of her birthday to the little girls.[Pg 55]

'Mrs. Nestor is thinking of a great treat for you—and for me, Helena,' she said. 'And she and I want you to know about it at once, so that you may all talk about it together and enjoy it beforehand as well. Some little bird, it seems, has flown over to Moor Court and told that next Tuesday week will be your old granny's birthday, and Mrs. Nestor has invited us to spend the afternoon of it there. You will like that, will you not?'

I looked up at grandmamma, feeling quite strange. You will hardly believe that I had never in my life paid even a visit of this simple kind.

'Yes,' I whispered, feeling myself getting pink all over, as I knew that Mrs. Nestor was looking at me, 'yes, thank you.'

Then dear little Vallie came close up to me, and said in a low voice—

'Now we can settle about the surprise. Come quick, Helena—the surprise will be the fun.'

And when I found myself alone with the others again, all three of them, even Nan, chattering at once, I soon found my own tongue again, and the strange, unreal sort of feeling went off. They were very simple unspoilt children, though their parents were rich and what I used to call 'grand.' It is quite[Pg 56] a mistake to think that the children who live in very large houses and have ponies and lots of servants and everything they can want are sure to be spoilt. Very often it is quite the opposite. For, if their parents are good and wise, they are extra careful not to spoil them, knowing that the sort of trials that cannot be kept away from poorer children, and which are a training in themselves in some ways, are not likely to come to their children. I even think now, looking back, that there was really more risk of being spoilt, for me myself, than for Sharley and her brothers and sisters.

Being allowed to be selfish is the real beginning and end of being spoilt, I am quite sure.

The 'surprise' they had thought of was a very simple one, and one that I knew grandmamma would like. It was that we should have tea out-of-doors, in an arbour where there was a table and seats all round. And we were to decorate it with flowers, and a wicker arm-chair was to be brought out for granny, and wreathed with greenery and flowers, to show that she was queen of the feast.

'So it will be a "fête," after all, Helena,' said Sharley.

They were nearly as eager and pleased about it[Pg 57] as I was myself, for they had already learnt to love my grandmamma very dearly.

'There's only one thing,' we kept saying to each other every time we met before the great day, 'it mustn't rain. Oh, do let us hope it will be fine,—beautifully fine.'[Pg 58]

And it was a fine day! Things after all do not always go wrong in this world, though some people are fond of talking as if they did.

That day, that happy birthday, stands out in my mind so clearly that I think I must write a good deal about it, even though to most children there would not seem anything very remarkable to tell. But to me it was like a peep into fairyland. To begin with, it was the very first time in my life that I had ever paid a visit of any kind except once or twice when I had had tea in rather a dull fashion at the vicarage, where there were no children and no one who understood much about them. Miss Linden, the vicar's sister, a very old-maid sort of lady, though she meant to be kind, had my tea put out in a corner of the room by myself, while she and grandmamma had theirs in a regular drawing-room way. They[Pg 59] had muffins, I remember, and Miss Linden thought muffins not good for little girls, and my bread-and-butter was cut thicker than I ever had it at the cottage, and the slice of currant-bread was not nearly as good as Kezia's home-made cake—even the plainest kind.

No, my remembrances of going out to tea at the vicarage were not very enlivening.

How different the visit to Moor Court was!

It began—the pleasure of it at least to me—the first thing when I awoke that morning, and saw without getting out of bed—for my room was so little that I could not help seeing straight out of the window, and I never had the blinds drawn down—that it was a perfectly lovely morning. It was the sort of morning that gives almost certain promise of a beautiful day.

In our country, because of the hills, you see, it isn't always easy to tell beforehand what the weather is going to be, unless you really study it. But even while I was quite a child I had learnt to know the signs of it very well. I knew about the lights and shadows coming over the hills, the gray look at a certain side, the way the sun set, and lots of things of that kind which told me a good deal that a stranger[Pg 60] would never have thought of. I knew there were some kinds of bright mornings which were really less hopeful than the dull and gloomy ones, but there was nothing of that sort to-day, so I curled myself round in bed again with a delightful feeling that there was nothing to be feared from the weather.

I did not dare to get up till I heard Kezia's knock at the door—for that was one of grandmamma's rules, and though she had not many rules, those there were had to be obeyed, I can assure you.

I must have fallen asleep again, for the next thing I remember was hearing grandmamma's voice, and there she was, standing beside my bed.

'Oh, granny!' I called out, 'what a shame for you to be the one to wake me on your birthday.'

'No, dear,' said grandmamma, 'it is quite right. Kezia hasn't been yet, it is just about her time.'

I sprang up and ran to the table, where I had put my little present for grandmamma the night before, for of course I had got a present for her all of my own, besides having planned the treat with the Nestors.

I remember what my present was that year. It was a little box for holding buttons, which I had[Pg 61] bought at the village shop, and it had a picture of the old, old Abbey Church at Middlemoor on its lid. Grandmamma has that button-box still, I saw it in her work-basket only yesterday. I was very proud of it, for it was the first year I had saved pennies enough to be able to buy something instead of working a present for grandmamma.

She did seem so pleased with it. I remember now the look in her eyes as she stooped to kiss me. Then she turned and lifted something which I had not noticed from a chair standing near.

'This is my present for my little girl,' she said, and though I was inclined to say that it was not fair for her to give me presents on her birthday, I was so delighted with what she held out for me to see that I really could scarcely speak.

What do you think it was?

A new frock—the prettiest by far I had ever had. The stuff was white, embroidered by grandmamma herself in sky-blue, in such a pretty pattern. She had sat up at night to do it after I was in bed.

'Oh, grandmamma,' I said, 'how beautiful it is! Oh, may I—' but then I stopped short—'may I wear it to-day?' was what I was going to say. But, 'oh no,' I went on, 'it might get dirtied.'[Pg 62]

'You are to wear it to-day, dear,' said grandmamma, 'if that is what you were going to say, so you needn't spoil your pleasure by being afraid of its getting dirtied; it will wash perfectly well, for I steeped the silk I worked it in, in salt and water before using it, to make the colour quite fast. I will leave it here on the back of the chair, and when the time comes for you to get ready I will dress you myself, to be sure that it is all quite right.'

I kept peeping at my pretty frock all the time I was dressing; the sight of it seemed the one thing wanting to complete my happiness. For though Sharley and Nan and Vallie were never too grandly dressed, their things were always fresh and pretty, and I had been thinking to myself that none of my summer frocks were quite as nice or new-looking as theirs.

And to-day, though only May, was really summer.

Grandmamma wouldn't let me do very much that morning, as she did not want me to be tired for the afternoon.

'Is it a very long walk to Moor Court?' I asked her.

Grandmamma smiled, a little funnily, I thought afterwards.[Pg 63]

'Yes,' she said, 'it is between two and three miles.'

'Then we must set off early,' I said, 'so as not to have to go too fast and be tired when we get there. I don't mind for coming back about being tired; there'll be nothing to do then but go to bed, it'll all be over!' and I gave a little sigh, 'but I don't want to think about its being over yet.'

'We must start at half-past two,' said grandmamma. 'That will be time enough.'

Long before half-past two, as you can fancy, I was quite ready. My frock fitted perfectly, and even Kezia, who was rather afraid of praising my appearance for fear of making me conceited, said with a smile that I did look very nice.

I quite thought so myself, but I really think all my pride was for grandmamma's frock.

I settled myself in the window-seat looking towards the road, as I have explained.

'Stay there quietly,' grandmamma said to me, 'till I call you.'

And again I noticed a sort of little twinkle in her eyes, of which before long I understood the reason. I must have been sitting there a quarter of an hour at least when I thought I heard wheels coming. It wasn't the usual time for the butcher or baker, or[Pg 64] any of the cart-people, as I called them, and wheels of any other kind seldom came our way. So I looked out with great curiosity to see what it could be.

To my astonishment, there came trotting along the short bit of level road leading to our own steep path the two ponies and the pretty pony-carriage that had so delighted me the first time I saw them.

Sharley was driving, the little groom behind her. But this time my first feeling was certainly not one of pleasure. On the contrary I started in dismay.

'Oh dear,' I thought, 'there's something the matter, and Sharley has come herself to say we can't go.'

I rushed upstairs, the tears already very near my eyes.

'Granny, granny,' I exclaimed, 'the pony-carriage has come and Sharley's there! I'm sure she's come to tell us we can't go.'

My voice broke down before I could say anything more. Grandmamma was coming out of her room quite ready, and even in the middle of my fright I could not help thinking how nice she looked in her pretty dark gray dress and black lace cloak, which, though she had had it a great, great many years, always seemed to me rich and grand enough for the Queen herself to wear.[Pg 65]

'My dear little girl,' she said, 'you really must not get into the way of fancying misfortunes before they come. It is a very bad habit. Why shouldn't Sharley have come to fetch us? Don't you think it would be nicer to drive to Moor Court than to walk all that way along the dusty road?'

'Oh, granny,' I cried, and my tears, if they were there, vanished away like magic. 'Oh, granny, that would be too lovely. But are you quite sure?'

'Quite,' said grandmamma, 'I promised to keep it a secret to please Sharley, as she is so fond of surprises. Run down now to meet her and tell her we are quite ready.'

How perfectly delightful that drive was! I sat with my back to the ponies, on the low seat opposite grandmamma and Sharley.

'Vallie wanted to come too,' said Sharley, 'but that seat isn't very comfortable for two.'

It was very comfortable for one, at least I found it so. I had hardly ever been in a carriage before, and Sharley drove so nice and fast; she was very proud of being allowed to drive the two ponies. But they were so good, they seemed, like every one and everything else, determined to make that day a perfectly happy one.[Pg 66]

When we got to the lodge of Moor Court Sharley began to drive more slowly, and looked about as if expecting some one.

'The others said they would come to meet us,' she explained, 'and sometimes Pert is rather naughty about startling the ponies, even though he can't bear being startled himself. Oh, there they are!'

As she spoke the four figures appeared at a turn in the drive. Nan and Vallie in the pretty pink frocks, which no longer made me feel discontented with my own, as nothing could be prettier, I was quite firmly convinced, than grandmamma's beautiful work, which Sharley had already admired in her own pleasant and hearty way.

We two got out of the pony-carriage, leaving grandmamma to be driven up to the house by the groom, the little girls saying that their mother was waiting for her on the lawn in front.

I had never seen the boys before. Percival seemed to me quite big, though he was one year younger than Sharley and smaller for his age. Quintin was more like Nan, slow and solemn and rather fat, so his nickname of Quick certainly didn't suit him very well. But they were both very nice and kind to me. I am quite sure Sharley had[Pg 67] talked to them well about it before I came, though it was easy to see that when Pert was not on his best behaviour he was very fond of playing tricks.

I felt very happy, and not at all strange or frightened as I walked along between Sharley and Val, each holding one of my hands and chattering away about all we were going to do, though I had a queer, rather nice feeling as if I must be in a dream, it all seemed so pretty and wonderful.

And indeed many people, far better able to judge of such things than I, think that Moor Court is one of the loveliest places in England. I did not see much of the inside of the house that day, though I learnt to know it well afterwards. It was very old and very large, and everything about it seemed to me quite perfect. But on this day we amused ourselves almost altogether out of doors.

Grandmamma's chair was still waiting to be decorated, so

the next hour was spent very happily.—p. 67.

Grandmamma's chair was still waiting to be decorated, so

the next hour was spent very happily.—p. 67.

The children had already done a good deal to the arbour where we were to have tea; but grandmamma's chair was still waiting to be decorated, so the next hour was spent very happily in gathering branches of ivy and other pretty green things to twine about it, with here and there a bunch of flowers, which Mrs. Nestor had told the gardener we were to have.

Vallie was very anxious to make a wreath for[Pg 68] grandmamma, but though I thought it a very nice idea, I was afraid it would look rather funny, and when Sharley reminded us that wreaths couldn't be worn very well above a bonnet, we quite gave it up.

But we did make the table look very pretty, and at last everything was ready, except the tea itself and the hot cakes, which of course the servants would bring at the very end.

By the time we had finished it was nearly four o'clock, and we were not to have tea till half-past, so there was time for a nice game of hide-and-seek among the trees. I don't think I ever ran so fast or laughed so much in my life. They were all such good-natured children, even if they did have little quarrels they were soon over, and then I think they were all especially kind to me. I suppose they were sorry for me in some ways that did not come into my own mind at all.

Then we all went to the house to be made tidy for tea, and in spite of what grandmamma had said about not minding if my frock was dirtied I was very pleased to find that it was perfectly clean.

Grandmamma and Mrs. Nestor were waiting for us in the drawing-room; and we all went back to the arbour together, Sharley walking first with grandmamma,[Pg 69] which was quite right, as the plan about tea had been all her own.

Grandmamma was pleased. I think she liked to see how fond these children had already got to be of her, though perhaps it would have been as well if Quick had not informed us in the middle of tea that he liked her a great, great deal better than his real grandmamma, whose nose was very big and her hair quite black.

'But she's very kind to us too,' said Sharley, 'only I don't think she cares much for little boys.'

'Nor for tomboys either,' said Pert, who did love teasing Sharley whenever he had a chance.

'Jerry's her favourite,' said Nan.

'And I think he deserves to be,' said her mother.

'I wish he was here to-day, I know that,' said Sharley. 'It's such a long time to the holidays, and it won't be so nice this year when they do come, as most likely a boy's coming with Jerry.'

'Two boys,' corrected Pert, 'their name's Vandeleur, and they're his greatest friends.'