Battle of Lake Champlain.

Title: The Naval History of the United States. Volume 2

Author: Willis J. Abbot

Illustrator: W. C. Jackson

H. W. McVickar

Release date: August 24, 2008 [eBook #26416]

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/26416

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Christine P. Travers and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.

Page 993: "they were fired upon the Coreans" has been replaced by "they were fired upon by the Coreans".

Page 997: "the rescued part arrived in New York" has been replaced by "the rescued party arrived in New York".

The Table of Contents and the List of Illustration were not present in the original.

BY

With Many Illustrations

BY H. W. McVICAR AND W. C. JACKSON

New York:

PETER FENELON COLLIER, PUBLISHER.

Capture of the "Surveyor."—Work of the Gunboat Flotilla.—Operations on Chesapeake Bay.—Cockburn's Depredations.—Cruise of the "Argus."—Her Capture by the "Pelican."—Battle Between the "Enterprise" and "Boxer."—End of the Year 1813 on the Ocean.

On the Lakes.—Close of Hostilities on Lakes Erie and Huron.—Desultory Warfare on Lake Ontario in 1813.—Hostilities on Lake Ontario in 1814.—The Battle of Lake Champlain.—End of the War upon the Lakes.

On the Ocean.—The Work of the Sloops-of-War.—Loss of the "Frolic."—Fruitless Cruise of the "Adams."—The "Peacock" Takes the "Épervier."—The Cruise of the "wasp."—She Captures the "Reindeer."—Sinks the "Avon."—Mysterious End of the "Wasp".

Operations on the New England Coast.—The Bombardment of Stonington.—Destruction Of the United States Corvette "Adams."—Operations on Chesapeake Bay.—Work of Barney's Barge Flotilla.—Advance of the British Upon Washington.—Destruction of the Capitol.—Operations Against Baltimore.—Bombardment of Fort McHenry.

Desultory Hostilities on the Ocean.—Attack Upon Fort Bowyer.—Lafitte the Pirate.—British Expedition Against New Orleans.—Battle of the Rigolets.—Attack On New Orleans, and Defeat of the British.—Work of the Blue-jackets.—Capture Of the Frigate "President."—The "Constitution" takes The "Cyane" and "Levant."—The "Hornet" Takes the "Penguin."—End of the War.

Privateers and Prisons of the War.—The "Rossie."—Salem Privateers.—The "Gen. Armstrong" Gives Battle To a British Squadron, and Saves New Orleans.—Narrative of a British Officer.—The "Prince de Neufchatel."—Experiences Of American Prisoners of War.—The End.

The Long Peace Broken by the War With Mexico.—Activity of the Navy.—Captain Stockton's Stratagem.—The Battle at San Jose.—The Blockade.—Instances of Personal Bravery.—The Loss of the "Truxton."—Yellow Fever in the Squadron.—The Navy at Vera Cruz.—Capture of Alvarado.

The Navy in Peace.—Surveying the Dead Sea.—Suppressing the Slave Trade.—The Franklin Relief Expedition.—Commodore Perry in Japan.—Signing of the Treaty.—Trouble in Chinese Waters.—The Koszta Case.—The Second Franklin Relief Expedition.—Foote at Canton.—"Blood is Thicker Than Water".

The Opening of the Conflict.—The Navies of the Contestants.—Dix's Famous Despatch.—The River-gunboats.

Fort Sumter Bombarded.—Attempt of the "Star of the West" to Re-enforce Anderson.—The Naval Expedition to Fort Sumter.—The Rescue of the Frigate "Constitution."—Burning the Norfolk Navy-Yard.

Difficulties of the Confederates in Getting a Navy.—Exploit of the "French Lady."—Naval Skirmishing on the Potomac.—The Cruise of the "Sumter"

The Potomac Flotilla.—Capture of Alexandria.—Actions at Matthias Point.—Bombardment of the Hatteras Forts.

The "Trent" Affair.—Operations in Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds.—Destruction of the Confederate Fleet.

Reduction of Newbern.—Exploits of Lieut. Cushing.—Destruction of the Ram "Albemarle".

The Blockade-runners.—Nassau and Wilmington.—Work of the Cruisers.

Du Pont's Expedition to Hilton Head and Port Royal.—The Fiery Circle.

The First Ironclad Vessels in History.—The "Merrimac" Sinks the "Cumberland," and Destroys the "Congress."—Duel between the "Monitor" and "Merrimac".

The Navy in the Inland Waters.—The Mississippi Squadron.—Sweeping the Tennessee River.

Famous Confederate Privateers,—The "Alabama," the "Shenandoah," the "Nashville".

Work of the Gulf Squadron.—The Fight at the Passes of the Mississippi.—Destruction of the Schooner "Judah."—The Blockade of Galveston, and Capture of the "Harriet Lane".

The Capture of New Orleans.—Farragut's Fleet passes Fort St. Philip and Fort Jackson.

Along the Mississippi.—Forts Jackson and St. Philip Surrender.—The Battle at St. Charles.—The Ram "Arkansas."—Bombardment and Capture of Port Hudson.

On To Vicksburg.—Bombardment of the Confederate Stronghold.—Porter's Cruise in the Forests.

Vicksburg Surrenders, and the Mississippi is opened.—Naval Events along the Gulf Coast.

Operations About Charleston.—The Bombardment, the Siege, and the Capture.

The Battle of Mobile Bay.

The Fall of Fort Fisher.—The Navy ends its Work.

Police Service on the High Seas.—War Service in Asiatic Ports.—Losses by the Perils of the Deep.—A Brush With the Pirates.—Admiral Rodgers at Corea.—Services in Arctic Waters.—The Disaster at Samoa.—The Attack on the "Baltimore's" Men at Valparaiso.—Loss of the "Kearsarge."—The Naval Review.

The Naval Militia.—A Volunteer Service which in Time of War will be Effective.—How Boys are Trained for the Life of a Sailor.—Conditions of Enlistment in the Volunteer Branch of the Service.—The Work of the Seagoing Militia in Summer.

How the Navy Has Grown.—The Cost and Character of Our New White Ships of War.—Our Period of Naval Weakness and our Advance to a Place among the Great Naval Powers.—The New Devices of Naval Warfare.—The Torpedo, the Dynamite Gun, and the Modern Rifle.—Armor and its Possibilities.

The State of Cuba.—Pertinacity of the Revolutionists.—Spain's Sacrifices and Failure.—Spanish Barbarities.—The Policy of Reconcentration.—American Sympathy Aroused.—The Struggle in Congress.—The Assassination of the "Maine."—Report of the Commission.—The Onward March to Battle.

The Opening Days of the War.—The First Blow Struck in the Pacific.—Dewey and his Fleet.—The Battle at Manila.—An Eye-witness' Story.—Delay and Doubt in the East.—Dull Times for the Blue-jackets.—The Discovery of Cervera.—Hobson's Exploit.—The Outlook.

The Spanish Fleet makes a Dash from the Harbor.—Its total Destruction.—Admiral Cervera a Prisoner.—Great Spanish Losses.—American Fleet Loses but one Man.

CHAPTER XII.

CAPTURE OF THE "SURVEYOR." — WORK OF THE GUNBOAT FLOTILLA. — OPERATIONS ON CHESAPEAKE BAY. — COCKBURN'S DEPREDATIONS. — CRUISE OF THE "ARGUS." — HER CAPTURE BY THE "PELICAN." — BATTLE OF THE "ENTERPRISE" AND "BOXER." — END OF THE YEAR 1813 ON THE OCEAN.

ith

the capture of the "Chesapeake" in June, 1813, we abandoned our

story of the naval events along the coast of the United States, to

follow Capt. Porter and his daring seamen on their long cruise into

far-off seas. But while the men of the "Essex" were capturing whalers

in the Pacific, chastising insolent savages at Nookaheevah, and

fighting a gallant but unsuccessful fight at Valparaiso, other

blue-jackets were as gallantly serving their country nearer home. From

Portsmouth to Charleston the coast was watched by British ships, and

collisions between the enemies were of almost daily occurrence. In

many of these actions great bravery was shown on both (p. 538) sides.

Noticeably was this the case in the action between the cutter

"Surveyor" and the British frigate "Narcissus," on the night of June

12. The "Surveyor," a little craft manned by a crew of fifteen men,

and mounting six twelve-pound carronades, was lying in the York River

near Chesapeake Bay. From the masthead of the "Narcissus," lying

farther down the bay, the spars of the cutter could be seen above the

tree-tops; and an expedition was fitted out for her capture. Fifty

men, led by a veteran officer, attacked the little vessel in the

darkness, but were met with a most determined resistance. The

Americans could not use their carronades, but with their muskets they

did much execution in the enemy's ranks. But they were finally

overpowered, and the little cutter was towed down under the frigate's

guns. The next day Mr. Travis, the American commander, received his

sword which he had surrendered, with a letter from the British

commander, in which he said, "Your gallant and desperate attempt to

defend your vessel against more than double your number, on the night

of the 12th inst., excited such admiration on the part of your

opponents as I have seldom witnessed, and induced me to return you the

sword you had so nobly used, in testimony of mine.... In short, I am

at a loss which to admire most, the previous arrangement on board the

'Surveyor,' or the determined manner in which her deck was disputed,

inch by inch."

ith

the capture of the "Chesapeake" in June, 1813, we abandoned our

story of the naval events along the coast of the United States, to

follow Capt. Porter and his daring seamen on their long cruise into

far-off seas. But while the men of the "Essex" were capturing whalers

in the Pacific, chastising insolent savages at Nookaheevah, and

fighting a gallant but unsuccessful fight at Valparaiso, other

blue-jackets were as gallantly serving their country nearer home. From

Portsmouth to Charleston the coast was watched by British ships, and

collisions between the enemies were of almost daily occurrence. In

many of these actions great bravery was shown on both (p. 538) sides.

Noticeably was this the case in the action between the cutter

"Surveyor" and the British frigate "Narcissus," on the night of June

12. The "Surveyor," a little craft manned by a crew of fifteen men,

and mounting six twelve-pound carronades, was lying in the York River

near Chesapeake Bay. From the masthead of the "Narcissus," lying

farther down the bay, the spars of the cutter could be seen above the

tree-tops; and an expedition was fitted out for her capture. Fifty

men, led by a veteran officer, attacked the little vessel in the

darkness, but were met with a most determined resistance. The

Americans could not use their carronades, but with their muskets they

did much execution in the enemy's ranks. But they were finally

overpowered, and the little cutter was towed down under the frigate's

guns. The next day Mr. Travis, the American commander, received his

sword which he had surrendered, with a letter from the British

commander, in which he said, "Your gallant and desperate attempt to

defend your vessel against more than double your number, on the night

of the 12th inst., excited such admiration on the part of your

opponents as I have seldom witnessed, and induced me to return you the

sword you had so nobly used, in testimony of mine.... In short, I am

at a loss which to admire most, the previous arrangement on board the

'Surveyor,' or the determined manner in which her deck was disputed,

inch by inch."

During the summer of 1813, the little gunboats, built in accordance with President Jefferson's plan for a coast guard of single-gun vessels, did a great deal of desultory fighting, which resulted in little or nothing. They were not very seaworthy craft, the heavy guns mounted amidships causing them to careen far over in even a sailor's "capfull" of wind. When they went into action, the first shot from the gun set the gunboat rocking so that further fire with any precision of aim was impossible. The larger gunboats carried sail enough to enable them to cruise about the coast, keeping off privateers and checking the marauding expeditions of the British. Many of the gunboats, however, were simply large gallies propelled with oars, and therefore confined in their operations to bays and inland waters. The chief scene of their operations was Chesapeake Bay.

This noble sheet of water had been, since the very opening of the year 1813, under the control of the British, who had gathered there their most powerful vessels under the command of Admiral Cockburn, whose (p. 539) name gained an unenviable notoriety for the atrocities committed by his forces upon the defenceless inhabitants of the shores of Chesapeake Bay. Marauding expeditions were continually sent from the fleet to search the adjacent country for supplies. When this method of securing provisions failed, Cockburn hit upon the plan of bringing his fleet within range of a village, and then commanding the inhabitants to supply his needs, under penalty of the instant bombardment of the town in case of refusal. Sometimes this expedient failed, as when Commodore Beresford, who was blockading the Delaware, called upon the people of Dover to supply him at once with "twenty-five large bullocks and a proportionate quantity of vegetables and hay." But the sturdy inhabitants refused, mustered the militia, dragged some old cannon down to the water-side, and, for lack of cannon-balls of their own, valiantly fired back those thrown by the British, which fitted the American ordnance exactly.

Soon after this occurrence, a large party from Cockburn's fleet landed at Havre de Grace, and, having driven away the few militia, captured and burned the town. Having accomplished this exploit, the marauders continued their way up the bay, and turning up into the Sassafras River ravaged the country on both sides of the little stream. After spreading distress far and wide over the beautiful country that borders Chesapeake Bay, the vandals returned to their ships, boasting that they had despoiled the Americans of at least seventy thousand dollars, and injured them to the amount of ten times that sum.

By June, 1813, the Americans saw that something must be done to check the merciless enemy who had thus revived the cruel vandalism, which had ceased to attend civilized warfare since the middle ages. A fleet of fifteen armed gallies was fitted out to attack the frigate of Cockburn's fleet that lay nearest to Norfolk. Urged forward by long sweeps, the gunboats bore down upon the frigate, which, taken by surprise, made so feeble and irregular a response that the Americans thought they saw victory within their grasp. The gunboats chose their distance, and opened a well-directed fire upon their huge enemy, that, like a hawk attacked by a crowd of sparrows, soon turned to fly. But at this moment the wind changed, enabling two frigates which were at anchor lower down the bay to come up to the aid of their consort. The American gunboats drew off slowly, firing as they departed.

(p. 540) This attack infused new energy into the British, and they at once began formidable preparations for an attack upon Norfolk. On the 20th of June they moved forward to the assault,—three seventy-four-gun ships, one sixty-four, four frigates, two sloops, and three transports. They were opposed by the American forces stationed on Craney Island, which commands the entrance to Norfolk Harbor. Here the Americans had thrown up earthworks, mounting two twenty-four, one eighteen, and four six pound cannon. To work this battery, one hundred sailors from the "Constellation," together with fifty marines, had been sent ashore. A large body of militia and a few soldiers of the regular army were also in camp upon the island.

The British set the 22d as the date for the attack; and on the morning of that day, fifteen large boats, filled with sailors, marines, and soldiers to the number of seven hundred, put off from the ships, and dashed toward the batteries. At the same time a larger force tried to move forward by land, but were driven back, to wait until their comrades in the boats should have stormed and silenced the American battery. But that battery was not to be silenced. After checking the advance of the British by land, the Americans waited coolly for the column of boats to come within point-blank range. On they came, bounding over the waves, led by the great barge "Centipede," fifty feet long, and crowded with men. The blue-jackets in the shore battery stood silently at their guns. Suddenly there arose a cry, "Now, boys, are you ready?" "All ready," was the response. "Then fire!" And the great guns hurled their loads of lead and iron into the advancing boats. The volley was a fearful one; but the British still came on doggedly, until the fire of the battery became too terrible to be endured. "The American sailors handled the great guns like rifles," said one of the British officers, speaking of the battle. Before this terrific fire, the advancing column was thrown into confusion. The boats, drifting upon each other, so crowded together that the oars-men could not make any headway. A huge round shot struck the "Centipede," passing through her diagonally, leaving death and wounds in its track. The shattered craft sunk, and was soon followed by four others. The order for retreat was given; and, leaving their dead and some wounded in the shattered barges that lay in the shallow water, the British fled to their ships. Midshipman Tatnall, who, many years later, served in the (p. 541) Confederate navy, waded out with several sailors, and, seizing the "Centipede," drew her ashore. He found several wounded men in her,—one a Frenchman, with both legs shot away. A small terrier dog lay whimpering in the bow. His master had brought him along for a run on shore, never once thinking of the possibility of the flower of the British navy being beaten back by the Americans.

So disastrous a defeat enraged the British, who proceeded to wreak their vengeance upon the little town of Hampton, which they sacked and burned, committing acts of shameful violence, more in accordance with the character of savages than that of civilized white men. The story of the sack of Hampton forms no part of the naval annals of the war, and in its details is too revolting to deserve a place here. It is a narrative of atrocious cruelty not to be paralleled in the history of warfare in the nineteenth century.

Leaving behind him the smoking ruins of Hampton, Cockburn with his fleet dropped down the bay, and, turning southward, cruised along the coast of the Carolinas. Anchoring off Ocracoke Inlet, the British sent a fleet of armed barges into Pamlico Sound to ravage the adjoining coast. Two privateers were found lying at anchor in the sound,—the "Anaconda" of New York, and the "Atlas" of Philadelphia. The British forces, eight hundred in number, dashed forward to capture the two vessels. The "Atlas" fell an easy prey; but the thirteen men of the "Anaconda" fought stoutly until all hope was gone, then, turning their cannon down upon the decks of their own vessel, blew great holes in her bottom, and escaped to the shore. After this skirmish, the British landed, and marched rapidly to Newbern; but, finding that place well defended by militia, made their way back to the coast, desolating the country through which they passed, and seizing cattle and slaves. The latter they are said to have sent to the West Indies and sold. From Pamlico Sound Cockburn went to Cumberland Island, where he established his winter quarters, and whence he continued to send out marauding expeditions during the rest of the year.

Very different was the character of Sir Thomas Hardy, who commanded the British blockading fleet off the New England coast. A brave and able officer, with the nature and training of a gentleman, he was as much admired by his enemies for his nobility, as Cockburn was hated (p. 542) for his cruelty. It is more than possible, however, that the difference between the methods of enforcement of the blockade on the New England coast and on the Southern seaboard was due to definite orders from the British admiralty: for the Southern States had entered into the war heart and soul; while New England gave to the American forces only a faint-hearted support, and cried eagerly for peace at any cost. So strong was this feeling, that resolutions of honor to the brave Capt. Lawrence were defeated in the Massachusetts Legislature, on the ground that they would encourage others to embark in the needless war in which Lawrence lost his life. Whatever may have been the cause, however, the fact remains, that Hardy's conduct while on the blockade won for him the respect and admiration of the very people against whom his forces were arrayed.

On June 18 the British blockaders off New York Harbor allowed a little vessel to escape to sea, that, before she could be captured, roamed at will within sight of the chalk cliffs of England, and inflicted immense damage upon the commerce of her enemy. This craft was the little ten-gun brig "Argus," which left New York bound for France. She carried as passenger Mr. Crawford of Georgia, who had lately been appointed United States minister to France. After safely discharging her passenger at L'Orient, the "Argus" turned into the chops of the English Channel, and cruised about, burning and capturing many of the enemy's ships. She was in the very highway of British commerce; and her crew had little rest day or night, so plentiful were the ships that fell in their way. It was hard for the jackies to apply the torch to so many stanch vessels, that would enrich the whole crew with prize-money could they but be sent into an American port. But the little cruiser was thousands of miles from any American port, and no course was open to her save to give every prize to the flames. After cruising for a time in the English Channel, Lieut. Allen, who commanded the "Argus," took his vessel around Land's End, and into St. George's Channel and the Irish Sea. For thirty days he continued his daring operations in the very waters into which Paul Jones had carried the American flag nearly thirty-five years earlier. British merchants and shipping owners in London read with horror of the destruction wrought by this one vessel. Hardly a paper appeared without an account of some (p. 545) new damage done by the "Argus." Vessels were kept in port to rot at their docks, rather than fall a prey to the terrible Yankee. Rates of insurance went up to ruinous prices, and many companies refused to take any risks whatever so long as the "Argus" remained afloat. But the hue and cry was out after the little vessel; and many a stout British frigate was beating up and down in St. George's Channel, and the chops of the English Channel, in the hopes of falling in with the audacious Yankee, who had presumed to bring home to Englishmen the horrors of war.

It fell to the lot of the brig-sloop "Pelican" to rid the British waters of the "Argus." On the night of the thirteenth of August, the American vessel had fallen in with a British vessel from Oporto, and after a short chase had captured her. The usual result followed. The prisoners with their personal property were taken out of the prize, and the vessel was set afire. But, before the torch was applied, the American sailors had discovered that their prize was laden with wine; and their resolution was not equal to the task of firing the prize without testing the quality of the cargo. Besides treating themselves to rather deep potations, the boarding-crew contrived to smuggle a quantity of the wine into the forecastle of the "Argus." The prize was then fired, and the "Argus" moved away under easy sail. But the light of the blazing ship attracted the attention of the lookout on the "Pelican," and that vessel came down under full sail to discover the cause.

Day was just breaking, and by the gray morning light the British saw an American cruiser making away from the burning hulk of her last prize. The "Pelican" followed in hot pursuit, and was allowed to come alongside, although the fleet American could easily have left her far astern. But Capt. Allen was ready for the conflict; confident of his ship and of his crew, of whose half-intoxicated condition he knew nothing, he felt sure that the coming battle would only add more laurels to the many already won by the "Argus." He had often declared that the "Argus" should never run from any two-master; and now, that the gage of battle was offered, he promptly accepted.

At six o'clock in the morning, the "Pelican" came alongside, and opened the conflict with a broadside from her thirty-two pound carronades. The "Argus" replied with spirit, and a sharp cannonade began. (p. 546) Four minutes after the battle opened, Capt. Allen was struck by a round shot that cut off his left leg near the thigh. His officers rushed to his side, and strove to bear him to his cabin; but he resisted, saying he would stay on deck and fight his ship as long as any life was left him. With his back to a mast, he gave his orders and cheered on his men for a few minutes longer; then, fainting from the terrible gush of blood from his wound, was carried below. To lose their captain so early in the action, was enough to discourage the crew of the "Argus." Yet the officers left on duty were brave and skilful. Twice the vessel was swung into a raking position, but the gunners failed to seize the advantage. "They seemed to be nodding over their guns," said one of the officers afterward. The enemy, however, showed no signs of nodding. His fire was rapid and well directed, and his vessel manœuvred in a way that showed a practised seaman in command. At last he secured a position under the stern of the "Argus," and lay there, pouring in destructive broadsides, until the Americans struck their flag,—just forty-seven minutes after the opening of the action. The loss on the "Argus" amounted to six killed and seventeen wounded.

No action of the war was so discreditable to the Americans as this. In the loss of the "Chesapeake" and in the loss of the "Essex," there were certain features of the action that redounded greatly to the honor of the defeated party. But in the action between the "Argus" and the "Pelican," the Americans were simply outfought. The vessels were practically equal in size and armament, though the "Pelican" carried a little the heavier metal. It is also stated that the powder used by the "Argus" was bad. It had been taken from one of the prizes, and afterwards proved to be condemned powder of the British Government. In proof of the poor quality of this powder, one of the American officers states that many shot striking the side of the "Pelican" were seen to fall back into the water; while others penetrated the vessel's skin, but did no further damage. All this, however, does not alter the fact that the "Argus" was fairly beaten in a fair fight.

While the British thus snapped up an American man-of-war cruising at their harbors' mouths, the Americans were equally fortunate in capturing a British brig of fourteen guns off the coast of Maine. The captor was the United States brig "Enterprise," a lucky little vessel belonging to a (p. 547) very unlucky class; for her sister brigs all fell a prey to the enemy. The "Nautilus," it will be remembered, was captured early in the war. The "Vixen" fell into the hands of Sir James Yeo, who was cruising in the West Indies, in the frigate "Southampton;" but this gallant officer reaped but little benefit from his prize, for frigate and brig alike were soon after wrecked on one of the Bahama Islands. The "Siren," late in the war, was captured by the seventy-four-gun ship "Medway," and the loss of the "Argus" has just been chronicled. Of all these brigs, the "Argus" alone was able to fire a gun in her own defence, before being captured; the rest were all forced to yield quietly to immensely superior force.

In the war with Tripoli, the "Enterprise" won the reputation of being a "lucky" craft; and her daring adventures and thrilling escapes during the short naval war with France added to her prestige among sailors. When the war with England broke out, the little brig was put in commission as soon as possible, and assigned to duty along the coast of Maine. She did good service in keeping off privateers and marauding expeditions from Nova Scotia. In the early part of September, 1813, she was cruising near Penguin Point, when she sighted a brig in shore that had the appearance of a hostile war-vessel. The stranger soon settled all doubts as to her character by firing several guns, seemingly for the purpose of recalling her boats from the shore. Then, setting sail with the rapidity of a man-of-war, she bore down upon the American vessel. The "Enterprise," instead of waiting for the enemy, turned out to sea, under easy sail; and her crew were set to work bringing aft a long gun, and mounting it in the cabin, where one of the stern windows had been chopped away to make a port. This action rather alarmed the sailors, who feared that their commander, Lieut. Burrows, whose character was unknown to them, intended to avoid the enemy, and was rigging the long gun for a stern-chaser. An impromptu meeting was held upon the forecastle; and, after much whispered consultation, the people appointed a committee to go aft and tell the commander that the lads were burning to engage the enemy, and were confident of whipping her. The committee started bravely to discharge their commission; but their courage failed them before so mighty a potentate as the commander, and they whispered their message to the first lieutenant, who laughed, and sent word forward (p. 548) that Mr. Burrows only wanted to get sea-room, and would soon give the jackies all the fighting they desired.

The Americans now had leisure to examine, through their marine-glasses, the vessel which was so boldly following them to the place of battle. She was a man-of-war brig, flying the British ensign from both mastheads and at the peak. Her armament consisted of twelve eighteen-pound carronades and two long sixes, as against the fourteen eighteen-pound carronades and two long nines of the "Enterprise." The Englishman carried a crew of sixty-six men, while the quarter-rolls of the American showed a total of one hundred and (p. 549) two. But in the battle which followed the British fought with such desperate bravery as to almost overcome the odds against them.

For some time the two vessels fought shy of each other, manœuvring for a windward position. Towards three o'clock in the afternoon, the Americans gained this advantage, and at once shortened sail, and edged down toward the enemy. As the ships drew near, a sailor was seen to climb into the rigging of the Englishman, and nail the colors to the mast, giving the lads of the "Enterprise" a hint as to the character of the reception they might expect. As the vessels came within range, both crews cheered lustily, and continued cheering until within pistol-shot, when the two broadsides were let fly at almost exactly the same moment. With the first fire, both commanders fell. Capt. Blyth of the English vessel was almost cut in two by a round shot as he stood on his quarter-deck. He died instantly. Lieut. Burrows was struck by a canister-shot, which inflicted a mortal wound. He refused to be carried below, and was tenderly laid upon the deck, where he remained during the remainder of the battle, cheering on his men, and crying out that the colors of the "Enterprise" should never be struck. The conflict was sharp, but short. For ten minutes only the answering broadsides rung out; then the colors of the British ship were hauled down. She proved to be the sloop-of-war "Boxer," and had suffered severely from the broadsides of the "Enterprise." Several shots had taken effect in her hull, her foremast was almost shot away, and several guns were dismounted. Three men beside her captain were killed, and seventeen wounded. But she had not suffered these injuries without inflicting some in return. The "Enterprise" was much cut up aloft. Her foremast and mainmast had each been pierced by an eighteen-pound ball. Her captain lay upon the deck, gasping in the last agonies of death, but stoutly protesting that he would not be carried below until he received the sword of the commander of the "Boxer." At last this was brought him; and grasping it he cried, "Now I am satisfied. I die contented."

The two shattered brigs were taken into Portland, where the bodies of the two slain commanders were buried with all the honors of war. The "Enterprise" was repaired, and made one more cruise before the close of the war; but the "Boxer" was found to be forever ruined for a vessel of war, and she was sold into the merchant-service. The fact that she (p. 550) was so greatly injured in so short a time led a London paper, in speaking of the battle, to say, "The fact seems to be but too clearly established, that the Americans have some superior mode of firing; and we cannot be too anxiously employed in discovering to what circumstances that superiority is owing."

This battle practically closed the year's naval events upon the ocean. The British privateer "Dart" was captured near Newport by some volunteers from the gunboats stationed at that point. But, with this exception, nothing noteworthy in naval circles occurred during the remainder of the year. Looking back over the annals of the naval operations of 1813, it (p. 551) is clear that the Americans were the chief sufferers. They had the victories over the "Peacock," "Boxer," and "Highflyer" to boast of; but they had lost the "Chesapeake," "Argus," and "Viper." But, more than this, they had suffered their coast to be so sealed up by British blockaders that many of their best vessels were left to lie idle at their docks. The blockade, too, was growing stricter daily, and the outlook for the future seemed gloomy; yet, as it turned out, in 1814 the Americans regained the ground they had lost the year before.[Back to Contents]

CHAPTER XIII.

ON THE LAKES. — CLOSE OF HOSTILITIES ON LAKES ERIE AND HURON. — DESULTORY WARFARE ON LAKE ONTARIO IN 1813. — HOSTILITIES ON ONTARIO IN 1814. — THE BATTLE OF LAKE CHAMPLAIN. — END OF THE WAR UPON THE LAKES.

n

considering the naval operations on the Great Lakes, it must be

kept in mind, that winter, which checked but little naval activity on

the ocean, locked the great fresh-water seas in an impenetrable

barrier of ice, and effectually stopped all further hostilities

between the hostile forces afloat. The victory gained by Commodore

Perry on Lake Erie in September, 1813, gave the Americans complete

command of that lake; and the frozen season soon coming on, prevented

any attempts on the part of the enemy to contest the American

supremacy. But, indeed, the British showed little ability, throughout

the subsequent course of the war, to snatch from the Americans the

fruits of the victory at Put-in-Bay. They embarked upon no more

offensive expeditions; and the only notable naval contest between the

two belligerents during the remainder of the war occurred Aug. 12,

1814, when a party of seventy-five British seamen and marines

attempted to cut out three American schooners that lay at the foot of

the lake near Fort Erie. (p. 553) The British forces were at

Queenstown, on the Niagara River; but by dint of carrying their boats

twenty miles through the woods, then poling down a narrow and shallow

stream, with a second portage of eight miles, the adventurers managed

to reach Lake Erie. Embarking here, they pulled down to the schooners.

To the hail of the lookout, they responded, "Provision boats." And, as

no British were thought to be on Lake Erie, the response satisfied the

officer of the watch. He quickly discovered his mistake, however, when

he saw his cable cut, and a party of armed men scrambling over his

bulwarks. This first prize, the "Somers," was quickly in the hands of

the British, and was soon joined in captivity by the "Ohio," whose

people fought bravely but unavailingly against the unexpected foe.

While the fighting was going on aboard the vessels, they were drifting

down the stream; and, by the time the British victory (p. 554) was

complete, both vessels were beyond the range of Fort Erie's guns, and

safe from recapture. This successful enterprise certainly deserves a

place as the boldest and best executed cutting-out expedition of the

war.

n

considering the naval operations on the Great Lakes, it must be

kept in mind, that winter, which checked but little naval activity on

the ocean, locked the great fresh-water seas in an impenetrable

barrier of ice, and effectually stopped all further hostilities

between the hostile forces afloat. The victory gained by Commodore

Perry on Lake Erie in September, 1813, gave the Americans complete

command of that lake; and the frozen season soon coming on, prevented

any attempts on the part of the enemy to contest the American

supremacy. But, indeed, the British showed little ability, throughout

the subsequent course of the war, to snatch from the Americans the

fruits of the victory at Put-in-Bay. They embarked upon no more

offensive expeditions; and the only notable naval contest between the

two belligerents during the remainder of the war occurred Aug. 12,

1814, when a party of seventy-five British seamen and marines

attempted to cut out three American schooners that lay at the foot of

the lake near Fort Erie. (p. 553) The British forces were at

Queenstown, on the Niagara River; but by dint of carrying their boats

twenty miles through the woods, then poling down a narrow and shallow

stream, with a second portage of eight miles, the adventurers managed

to reach Lake Erie. Embarking here, they pulled down to the schooners.

To the hail of the lookout, they responded, "Provision boats." And, as

no British were thought to be on Lake Erie, the response satisfied the

officer of the watch. He quickly discovered his mistake, however, when

he saw his cable cut, and a party of armed men scrambling over his

bulwarks. This first prize, the "Somers," was quickly in the hands of

the British, and was soon joined in captivity by the "Ohio," whose

people fought bravely but unavailingly against the unexpected foe.

While the fighting was going on aboard the vessels, they were drifting

down the stream; and, by the time the British victory (p. 554) was

complete, both vessels were beyond the range of Fort Erie's guns, and

safe from recapture. This successful enterprise certainly deserves a

place as the boldest and best executed cutting-out expedition of the

war.

Long before this occurrence, Capt. Arthur Singleton, who had succeeded to Perry's command, despairing of any active service on Lake Erie, had taken his squadron of five vessels into Lake Huron, where the British still held the supremacy. His objective point was the Island of Michilimackinac (Mackinaw), which had been captured by the enemy early in the war. On his way, he stopped and burned the British fort and barracks of St. Joseph. At Mackinaw he was repulsed, with the loss of seventy men; after which he returned to Lake Erie, leaving two vessels, the "Scorpion" and "Tigress," to blockade the Nattagawassa River. The presence of these vessels irritated the British, and they at once set about preparations for their capture. On the night of the 3d of September the "Tigress" was captured after a sharp struggle, which, as the British commanding officer said, "did credit to her officers, who were all severely wounded." At the time of the attack, the "Scorpion" was several miles away, and knew nothing of the misfortune of her consort. Knowing this, the British sent their prisoners ashore, and, hoisting the American flag over the captured vessel, waited patiently for their game to come to them. They were not disappointed in their expectations. On the 5th the "Scorpion" came up, and anchored, unsuspectingly, within two miles of her consort. At early dawn the next morning the "Tigress" weighed anchor; and, with the stars and stripes still flying, dropped down alongside the unsuspecting schooner, poured in a sudden volley, and, instantly boarding, carried the vessel without meeting any resistance.

With these two skirmishes, the war upon Lake Erie and Lake Huron was ended. But on Lake Ontario the naval events, though in no case comparable with Perry's famous victory, were numerous and noteworthy.

In our previous discussion of the progress of the war upon Lake Ontario, we left Commodore Chauncey in winter quarter at Sackett's Harbor, building new ships, and making vigorous efforts to secure sailors to man them. His energy met with its reward; for, when the melting ice left the lake open for navigation in the spring of 1813, the American fleet was ready for active service, while the best vessels belonging to the (p. 555) British were still in the hands of the carpenters and riggers. The first service performed by the American fleet was aiding Gen. Pike in his attack upon York, where the Americans burned an almost completed twenty-four-gun ship, and captured the ten-gun brig "Gloucester." The land forces who took part in this action were terribly injured by the explosion of the powder-magazine, to which the British had applied a slow-match when they found they could no longer hold their position. This battle was fought April 27, 1813. One month later, the naval forces co-operated with the soldiery in driving the British from Fort George, on the Canada side of the Niagara River, near Lake Ontario. Perry came from Lake Erie to take part in this action, and led a landing party under the fire of the British artillery with that dashing courage which he showed later at the battle of Put-in-Bay. The work of the sailors in this action was cool and effective. Their fire covered the advance of the troops, and silenced more than one of the enemy's guns. "The American ships," writes a British historian, "with their heavy discharges of round and grape, too well succeeded in thinning the British ranks."

But by this time the British fleet was ready for sea, and left Kingston on the 27th of May; while Chauncey was still at the extreme western end of the lake. The enemy determined to make an immediate assault upon Sackett's Harbor, and there destroy the corvette "Gen. Pike," which, if completed, would give Chauncey supremacy upon the lake. Accordingly the fleet under Sir James Lucas Yeo, with a large body of troops under Sir George Prescott, appeared before the harbor on the 29th. Although the forces which rallied to the defence of the village were chiefly raw militia, the British attack was conducted with so little spirit that the defenders won the day; and the enemy retreated, leaving most of his wounded to fall into the hands of the Americans. Yeo then returned to Kingston; and the American fleet came up the lake, and put into Sackett's Harbor, there to remain until the completion of the "Pike" should give Chauncey control of the lake. While the Americans thus remained in port, the British squadron made brief incursions into the lake, capturing a few schooners and breaking up one or two encampments of the land forces of the United States.

Not until the 21st of July did the Americans leave their anchorage. On that day, with the formidable corvette "Pike" at the head of the (p. 556) line, Chauncey left Sackett's Harbor, and went up to Niagara. Some days later, Yeo took his squadron to sea; and on the 7th of August the two hostile fleets came in sight of one another for the first time. Then followed a season of manœuvring,—of challenging and counter-challenging, of offering battle and of avoiding it,—terminating in so inconclusive an engagement that one is forced to believe that neither commander dared to enter the battle for which both had been so long preparing. The American squadron consisted largely of schooners armed with long guns. In smooth weather these craft were valuable adjuncts to the larger vessels, while in rough weather they were useless. Yeo's squadron was mostly square-rigged, and was therefore equally serviceable in all kinds of weather. It seems likely, therefore, that the Americans strove to bring on the conflict in smooth weather; while the British were determined to wait until a heavy sea should lessen the force of their foes. In this dilemma several days passed away.

On the night of the 7th of August the wind came up to blow, and the rising waves soon demonstrated the uselessness of schooners for purposes of war. At early dawn a fierce gust of wind caused the schooners "Hamilton" and "Scourge" to careen far to leeward. Their heavy guns broke loose; then, crashing down to the submerged beams of the schooners, pulled them still farther over; and, the water rushing in at their hatches, they foundered, carrying with them to the bottom all their officers, and all but sixteen of the men. This loss reduced Chauncey's force to more of an equality with that of the British; yet for two days longer the manœuvring continued, without a shot being fired. On the night of the 10th the two squadrons formed in order of battle, and rapidly approached each other. At eleven o'clock a cannonade was begun by both parties, and continued for about an hour; though the shot did little material damage on either side. At midnight the British, by a quick movement, cut out and captured two American schooners, and sailed away, without suffering any damage.

A month then intervened before the next hostile meeting. In his despatches to his superior authorities, each commander stoutly affirms that he spent the time in chasing the enemy, who refused to give him battle. Whether it was the British or the Americans that avoided the battle, it is impossible to decide; but it seems reasonable to believe, that, had (p. 557) either party been really determined upon bringing matters to an issue, the other could have been forced into giving battle.

On the 11th of September, the enemies met near the mouth of the Genesee River, and exchanged broadsides. A few of the British vessels were hulled, and, without more ado, hauled off into the shallow waters of Ambert Bay, whither the Americans could not follow them. Then ensued another long period of peace, broken at last by a naval action in York Bay, on the 28th, in which the British were worsted and obliged to fly, though none of their ships were destroyed or captured. On Oct. 2, Chauncey accomplished a really important work, by capturing five British transports, with two hundred and sixty-four men, seven naval and ten army officers. With this achievement, the active work of the Ontario squadron ended for the year, as Chauncey remained blockading Yeo at Kingston, until the approach of winter rendered that precaution no longer necessary.

The navigable season of 1814 opened with the British first upon the lake. The long winter had been employed by the belligerents in adding to their fleets; a work completed first by Yeo, who put out upon the lake on the 3d of May, with eight square-rigged vessels, of which two were new frigates. The Americans had given up their unseaworthy schooners, and had a fleet of eight square-rigged vessels nearly ready, but still lacking the cordage and guns for the three new craft. Yeo thus had the lake to himself for a time, and began a vigorous campaign by an attack upon Oswego, aided by a large body of British troops. Succeeding in this enterprise, he set sail for Sackett's Harbor, and, taking up his position just outside the bar, disposed his vessels for a long and strict blockade. This action was particularly troublesome to the Americans at that time; for their new frigates were just ready for their guns and cables, which could not be brought overland, and the arrival of which by water was seemingly prevented by the blockade. It was in this emergency that the plan, already described, for transporting the great cable for the "Niagara" overland, on the backs of men, was decided upon. Yeo remained on guard at the mouth of the harbor until the 6th of June, then raised the blockade, and disappeared down the lake. For six weeks the Americans continued working on their fleet, to get the ships ready for service. During this time the British gunboat "Black Snake" was brought into the harbor, a (p. 558) prize to Lieut. Gregory, who had captured it by a sudden assault, with a score of sailors at his back. On the 1st of July, the same officer made a sudden descent upon Presque Isle, where he found a British vessel pierced for fourteen guns on the stocks, ready for launching. The raiders hastily set fire to the ship, and retreated before the enemy could get his forces together.

It was July 31 before Chauncey set sail from Sackett's Harbor. He now had under his command a squadron of eight vessels, two of which were frigates, two ship sloops-of-war, and eight brig-sloops of no mean power. Yeo had, to oppose this force, a fleet of no less respectable proportions. Yet, for the remainder of the year, these two squadrons cruised about the lake, or blockaded each other in turn, without once coming to battle. As transports, the vessels were of some service to their respective governments; but, so far as any actual naval operations were concerned, they might as well never have been built. The war closed, leaving the two cautious commanders still waiting for a satisfactory occasion for giving battle.

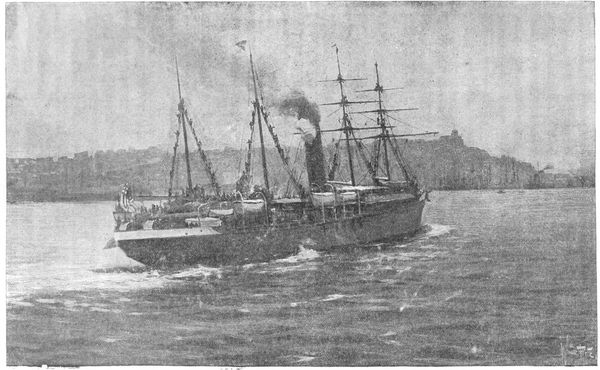

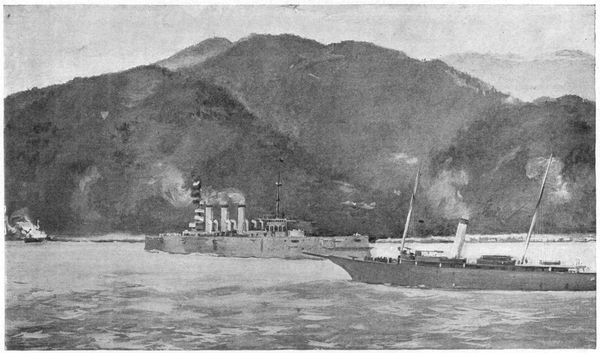

Such was the course of the naval war upon the Great Lakes; but the thunder of hostile cannon and the cheers of sailors were heard upon yet another sheet of fresh water, before the quarrel between England and the United States was settled. In the north-east corner of New York State, and slightly overlapping the Canada line, lies Lake Champlain,—a picturesque sheet of water, narrow, and dotted with wooded islands. From the northern end of the lake flows the Richelieu River, which follows a straight course through Canada to the St. Lawrence, into which it empties. The long, navigable water-way thus open from Canada to the very heart of New York was to the British a most tempting path for an invading expedition. By the shore of the lake a road wound along; thus smoothing the way for a land force, whose advance might be protected by the fire of the naval force that should proceed up the lake. Naturally, so admirable an international highway early attracted the attention of the military authorities of both belligerents; and, while the British pressed forward their preparations for an invading expedition, the Americans hastened to make such arrangements as should give them control of the lake. Her European wars, however, made so great a demand for soldiers upon Great Britain, that not until 1814 could she send to America a (p. 559) sufficient force to undertake the invasion of the United States from the north. In the spring of that year, a force of from ten thousand to fifteen thousand troops, including several thousand veterans who had served under Wellington, were massed at Montreal; and in May a move was made by the British to get control of the lake, before sending their invading forces into New York. The British naval force already in the Richelieu River, and available for service, consisted of a brig, two sloops, and twelve or fourteen gunboats. The American flotilla included a large corvette, a schooner, a small sloop, and ten gunboats, or galleys, propelled with oars. Seeing that the British were preparing for active hostilities, the Americans began to build, with all possible speed, a large brig; a move which the enemy promptly met by pushing forward with equal energy the construction of a frigate. While the new vessels were on the stocks, an irregular warfare was carried on by those already in commission. At the opening of the season, the American vessels lay in Otter Creek; and, just as they were ready to leave port, the enemy appeared off the mouth of the creek with a force consisting of the brig "Linnet" and eight or ten galleys. The object of the British was to so obstruct the mouth of the creek that the Americans should be unable to come out. With this end in view, they had brought two sloops laden with stones, which they intended to sink in the narrow channel. But, luckily, the Americans had thrown up earthworks at the mouth of the river; and a party of sailors so worked the guns, that, after much manœuvring, the British were forced to retire without effecting their purpose.

About the middle of August, the Americans launched their new brig, the "Eagle;" and the little squadron put out at once into the lake, under command of Capt. Thomas Macdonough. Eight days later, the British got their new ship, the "Confiance," into the water. She possessed one feature new to American naval architecture,—a furnace in which to heat cannon-balls.

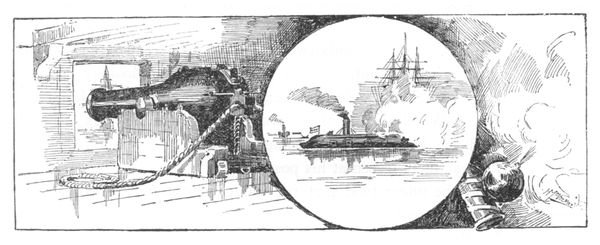

By this time (September, 1814), the invading column of British veterans, eleven thousand strong, had begun its march into New York along the west shore of the lake. Two thousand Americans only could be gathered to dispute their progress; and these, under the command of Brigadier-Gen. Macomb, were gathered at Plattsburg. To this point, accordingly, Macdonough took his fleet, and awaited the coming of the (p. 560) enemy; knowing that if he could beat back the fleet of the British, their land forces, however powerful, would be forced to cease their advance. The fleet that he commanded consisted of the flagship "Saratoga," carrying eight long twenty-four-pounders, six forty-two-pound and twelve thirty-two-pound carronades; the brig "Eagle," carrying eight long eighteens, and twelve thirty-two-pound carronades; schooner "Ticonderoga," with eight long twelve-pounders, four long eighteen-pounders, and five thirty-two-pound carronades; sloop "Preble," with seven long nines; and ten galleys. The commander who ruled over this fleet was a man still in his twenty-ninth year. The successful battles of the War of 1812 were fought by young officers, and the battle of Lake Champlain was no exception to the rule.

The British force which came into battle with Macdonough's fleet was slightly superior. It was headed by the flagship "Confiance," a frigate of the class of the United States ship "Constitution," carrying thirty long twenty-fours, a long twenty-four-pounder on a pivot, and six thirty-two or forty-two pound carronades. The other vessels were the "Linnet," a brig mounting sixteen long twelves; and the "Chubb" and "Finch" (captured from the Americans under the names of "Growler" and "Eagle"),—sloops carrying respectively ten eighteen-pound carronades and one long six; and six eighteen-pound carronades, four long sixes, and one short eighteen. To these were added twelve gunboats, with varied armaments, but each slightly heavier than the American craft of the same class.

The 11th of September had been chosen by the British for the combined land and water attack upon Plattsburg. With the movements of the land forces, this narrative will not deal. The brunt of the conflict fell upon the naval forces, and it was the success of the Americans upon the water that turned the faces of the British invaders toward Canada.

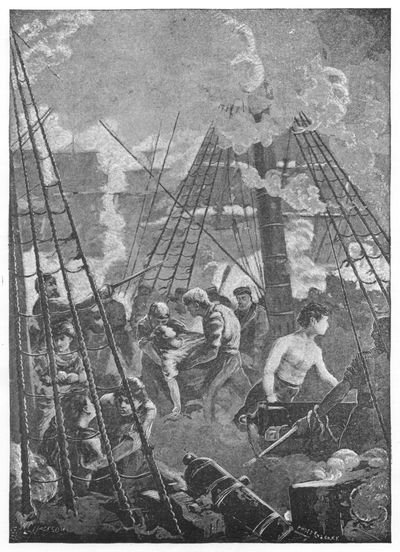

The village of Plattsburg stands upon the shore of a broad bay which communicates with Lake Champlain by an opening a mile and a half wide, bounded upon the north by Cumberland Head, and on the south by Crab Island. In this bay, about two miles from the western shore, Macdonough's fleet lay anchored in double line, stretching north and south. The four large vessels were in the front rank, prepared to meet the brunt of the conflict; while the galleys formed a second line in the rear. The morning of the day of battle dawned clear, with a brisk north-east (p. 561) wind blowing. The British were stirring early, and at daybreak weighed anchor and came down the lake. Across the low-lying isthmus that connected Cumberland Head with the mainland, the Americans could see their adversaries' topmasts as they came down to do battle. At this sight, Macdonough called his officers about him, and, kneeling upon the quarter-deck, besought Divine aid in the conflict so soon to come. When the little group rose from their knees, the leading ship of the enemy was seen swinging round Cumberland Head; and the men went to their quarters to await the fiery trial that all knew was impending.

The position of the American squadron was such that the British were forced to attack "bows on," thus exposing themselves to a raking fire. By means of springs on their cables, the Americans were enabled to keep their broadsides to the enemy, and thus improve, to the fullest, the advantage gained by their position. The British came on gallantly, and were greeted by four shots from the long eighteens of the "Eagle," that had no effect. But, at the sound of the cannon, a young game-cock that was running at large on the "Saratoga" flew upon a gun, flapped his wings, and crowed thrice, with so lusty a note that he was heard far over the waters. The American seamen, thus roused from the painful revery into which the bravest fall before going into action, cheered lustily, and went into the fight, encouraged as only sailors could be by the favorable omen.

Soon after the defiant game-cock had thus cast down the gage of battle, Macdonough sighted and fired the first shot from one of the long twenty-four pounders of the "Saratoga." The heavy ball crashed into the bow of the "Confiance," and cut its way aft, killing and wounding several men, and demolishing the wheel. Nothing daunted, the British flagship came on grandly, making no reply, and seeking only to cast anchor alongside the "Saratoga," and fight it out yard-arm to yard-arm. But the fire of the Americans was such that she could not choose her distance; but after having been badly cut up, with both her port anchors shot away, was forced to anchor at a distance of a quarter of a mile. But her anchor had hardly touched bottom, when she suddenly flashed out a sheet of flames, as her rapid broadsides rung out and her red-hot shot sped over the water toward the American flagship. Her first broadside killed or wounded forty of the Americans; while many more were (p. 562) knocked down by the shock, but sustained no further injury. So great was the carnage, that the hatches were opened, and the dead bodies passed below, that the men might have room to work the guns. Among the slain was Mr. Gamble, the first lieutenant, who was on his knees sighting a gun, when a shot entered the port, split the quoin, drove a great piece of metal against his breast, and stretched him dead upon the deck without breaking his skin. By a singular coincidence, fifteen minutes later a shot from one of the "Saratoga's" guns struck the muzzle of a twenty-four on the "Confiance," and, dismounting it, hurled it against Capt. Downie's groin, killing him instantly without breaking the skin; a black mark about the size of a small plate was the sole visible injury.

In the mean time, the smaller vessels had become engaged, and were fighting with no less courage than the flag-ships. The "Chubb" had early been disabled by a broadside from the "Eagle," and drifted helplessly under the guns of the "Saratoga." After receiving a shot from that vessel, she struck, and was taken possession of by Midshipman Platt, who put off from the flagship in an open boat, boarded the prize, and took her into Plattsburg Bay, near the mouth of the Saranac. More than half her people were killed or wounded during the short time she was in the battle. The "Linnet," in the mean time, had engaged the "Eagle," and poured in her broadsides with such effect that the springs on the cables of the American were cut away, and she could no longer bring her broadsides to bear. Her captain therefore cut his cables, and soon gained a position from which he could bring his guns to bear upon the "Confiance." The "Linnet" thereupon dashed in among the American gunboats, and, driving them off, commenced a raking fire upon the "Saratoga." The "Finch," meanwhile, had ranged gallantly up alongside the "Ticonderoga," but was sent out of the fight by two broadsides from the American. She drifted helplessly before the wind, and soon grounded near Crab Island. On the island was a hospital, and an abandoned battery mounting one six-pound gun. Some of the convalescent patients, seeing the enemy's vessel within range, opened fire upon her from the battery, and soon forced her to haul down her flag. Nearly half her crew were killed or wounded. Almost at the same moment, the United States sloop "Preble" was forced out of the fight by the British (p. 563) gunboats, that pressed so fiercely upon her that she cut her cables and drifted inshore.

The "Ticonderoga" fought a gallant fight throughout. After ridding herself of the "Finch," she had a number of the British gunboats to contend with; and they pressed forward to the attack with a gallantry that showed them to be conscious of the fact, that, if this vessel could be carried, the American line would be turned, and the day won by the English. But the American schooner fought stubbornly. Her gallant commander, Lieut. Cassin, walked up and down the taffrail, heedless of the grape and musket-balls that whistled past his head, pointing out to the gunners the spot whereon to train the guns, and directing them to load with canister and bags of bullets when the enemy came too near. The gunners of the schooner were terribly hampered in their work by the lack of matches for the guns; for the vessel was new, and the absence of these very essential articles was unnoticed until too late. The guns of one division were fired throughout the fight by Hiram Paulding, (p. 564) a sixteen-year-old midshipman, who flashed his pistol at the priming of the guns as soon as aim was taken. When no gun was ready for his services, he rammed a ball into his weapon and discharged it at the enemy. The onslaught of the British was spirited and determined. Often they pressed up within a boat-hook's length of the schooner, only to be beaten back by her merciless fire. Sometimes so few were left alive in the galleys that they could hardly man the oars to pull out of the fight. In this way the "Ticonderoga" kept her enemies at bay while the battle was being decided between the "Saratoga" and the "Confiance."

For it was upon the issue of the conflict between these two ships, that victory or defeat depended. Each had her ally and satellite. Under the stern of the "Saratoga" lay the "Linnet," pouring in raking broadsides. The "Confiance," in turn, was suffering from the well-directed fire of the "Eagle." The roar of the artillery was unceasing, and dense clouds of gunpowder-smoke hid the warring ships from the eyes of the eager spectators on shore. The "Confiance" was unfortunate in losing her gallant captain early in the action, while Macdonough was spared to fight his ship to the end. His gallantry and activity, however, led him to expose himself fearlessly; and twice he narrowly escaped death. He worked like a common sailor, loading and firing a favorite twenty-four-pound gun; and once, while on his knees, sighting the piece, a shot from the "Confiance" cut in two the spanker-boom, a great piece of which fell heavily upon the captain's head, stretching him senseless upon the deck. He lay motionless for two or three minutes, and his men mourned him as dead; but suddenly his activity returned, and he leaped to his feet, and was soon again in the thick of the fight. In less than five minutes the cry again arose, that the captain was killed. He had been standing at the breach of his favorite cannon, when a round shot took off the head of the captain of the gun, and dashed it with terrific force into the face of Macdonough, who was driven across the deck, and hurled against the bulwarks. He lay an instant, covered with the blood of the slain man; but, hearing his men cry that he was killed, he rushed among them, to cheer them on with his presence.

And, indeed, at this moment the crew of the "Saratoga" needed the presence of their captain to cheer them on to further exertion. The red-hot shot of the "Confiance" had twice set fire to the American ship. (p. 565) The raking fire from the "Linnet" had dismounted carronades and long guns one by one, until but a single serviceable gun was left in the starboard battery. A too heavy charge dismounted this piece, and threw it down the hatchway, leaving the frigate without a single gun bearing upon the enemy. In such a plight the hearts of the crew might well fail them. But Macdonough was ready for the emergency. He still had his port broadside untouched, and he at once set to work to swing the ship round so that this battery could be brought to bear. An anchor was let fall astern, and the whole ship's company hauled in on the hawser, swinging the ship slowly around. It was a dangerous manœuvre; for, as the ship veered round, her stern was presented to the "Linnet," affording an opportunity for raking, which the gunners on that plucky little vessel immediately improved. But patience and hard pulling carried the day; and gradually the heavy frigate was turned sufficiently for the after gun to bear, and a gun's crew was at once called from the hawsers to open fire. One by one the guns swung into position, and soon the whole broadside opened with a roar.

Meanwhile the "Confiance" had attempted the same manœuvre. But her anchors were badly placed; and, though her people worked gallantly, they failed to get the ship round. She bore for some time the effective fire from the "Saratoga's" fresh broadside, but, finding that she could in no way return the fire, struck her flag, two hours and a quarter after the battle commenced. Beyond giving a hasty cheer, the people of the "Saratoga" paid little attention to the surrender of their chief enemy, but instantly turned their guns upon the "Linnet." In this combat the "Eagle" could take no part, and the thunder of her guns died away. Farther down the bay, the "Ticonderoga" had just driven away the last of the British galleys; so that the "Linnet" now alone upheld the cause of the enemy. She was terribly outmatched by her heavier foe, but her gallant captain Pring kept up a desperate defence. Her masts and rigging were hopelessly shattered; and no course was open to her, save to surrender, or fight a hopeless fight. Capt. Pring sent off a lieutenant, in an open boat, to ascertain the condition of the "Confiance." The officer returned with the report that Capt. Downie was killed, and the frigate terribly cut up; and as by this time the water, pouring in the shot-holes in the "Linnet's" hull, had risen a foot above the lower deck, her flag (p. 566) was hauled down, and the battle ended in a decisive triumph for the Americans.

Terrible was the carnage, and many and strange the incidents, of this most stubbornly contested naval battle. All of the prizes were in a sinking condition. In the hull of the "Confiance" were a hundred and five shot-holes, while the "Saratoga" was pierced by fifty-five. Not a mast that would bear canvas was left standing in the British fleet; those of the flagship were splintered like bundles of matches, and the sails torn to rags. On most of the enemy's vessels, more than half of the crews were killed or wounded. The loss on the British side probably aggregated three hundred. Midshipman William Lee of the "Confiance" wrote home after the battle, "The havoc on both sides was dreadful. I don't think there are more than five of our men, out of three hundred, but what are killed or wounded. Never was a shower of hail so thick as the shot whistling about our ears. Were you to see my jacket, waistcoat, and trousers, you would be astonished to know how I escaped as I did; for they are literally torn all to rags with shot and splinters. The upper part of my hat was also shot away. There is one of the marines who was in the Trafalgar action with Lord Nelson, who says it was a mere flea-bite in comparison with this."

The Americans, though victorious, had suffered greatly. Their loss amounted to about two hundred men. The "Saratoga" had been cut up beyond the possibility of repair. Her decks were covered with dead and dying. The shot of the enemy wrought terrible havoc in the ranks of the American officers. Lieut. Stansbury of the "Ticonderoga" suddenly disappeared in the midst of the action; nor could any trace of him be found, until, two days later, his body, cut nearly in two by a round shot, rose from the waters of the lake. Lieut. Vallette of the "Saratoga" was knocked down by the head of a sailor, sent flying by a cannon-ball. Some minutes later he was standing on a shot-box giving orders, when a shot took the box from beneath his feet, throwing him heavily upon the deck. Mr. Brum, the master, a veteran man-o'-war's man, was struck by a huge splinter, which knocked him down, and actually stripped every rag of clothing from his body. He was thought to be dead, but soon re-appeared at his post, with a strip of canvas about his waist, and fought bravely until the end of the action. Some days before the battle, a gentleman (p. 567) of Oswego gave one of the sailors a glazed tarpaulin hat, of the kind then worn by seamen. A week later the sailor re-appeared, and, handing him the hat with a semi-circular cut in the crown and brim, made while it was on his head by a cannon-shot, remarked calmly, "Look here, Mr. Sloane, how the damned John Bulls have spoiled my hat!"

The last British flag having been hauled down, an officer was sent to take possession of the "Confiance." In walking along her gun-deck, he accidentally ran against a ratline, by which one of her starboard guns was discharged. At this sound, the British galleys and gunboats, which had been lying quietly with their ensigns down, got out oars and moved off up the lake. The Americans had no vessels fit for pursuing them, and they were allowed to escape. In the afternoon the British officers came to the American flagship to complete the surrender. Macdonough met them courteously; and, on their offering their swords, put them back, saying, "Gentlemen, your gallant conduct makes you worthy to wear your weapons. Return them to their scabbards." By sundown the surrender was complete, and Macdonough sent off to the Secretary of the Navy a despatch, saying, "Sir,—The Almighty has been pleased to grant us a signal victory on Lake Champlain, in the capture of one frigate, one brig, and two sloops-of-war of the enemy."

Some days later, the captured ships, being beyond repair, were taken to the head of the lake, and scuttled. Some of the guns were found to be still loaded; and, in drawing the charges, one gun was found with a canvas bag containing two round shot rammed home, and wadded, without any powder; another gun contained two cartridges and no shot; and a third had a wad rammed down before the powder, thus effectually preventing the discharge of the piece. The American gunners were not altogether guiltless of carelessness of this sort. Their chief error lay in ramming down so many shot upon the powder that the force of the explosion barely carried the missiles to the enemy. In proof of this, the side of the "Confiance" was thickly dotted with round shot, which had struck into, but failed to penetrate, the wood.

The result of this victory was immediate and gratifying. The land forces of the British, thus deprived of their naval auxiliaries, turned about, and retreated to Canada, abandoning forever their projected invasion. New York was thus saved by Macdonough's skill and bravery. Yet the (p. 568) fame he won by his victory was not nearly proportionate to the naval ability he showed, and the service he had rendered to his country. Before the popular adulation of Perry, Macdonough sinks into second place. One historian only gives him the pre-eminence that is undoubtedly his due. Says Mr. Theodore Roosevelt, in his admirable history, "The Naval War of 1812," "But Macdonough in this battle won a higher fame than any other commander of the war, British or American. He had a decidedly superior force to contend against, and it was solely owing to his foresight and resource that we won the victory. He forced the British to engage at a disadvantage by his excellent choice of position, and he prepared beforehand for every possible contingency. His personal prowess had already been shown at the cost of the rovers of Tripoli, and in this action he helped fight the guns as ably as the best sailor. His skill, seamanship, quick eye, readiness of resource, and indomitable pluck are beyond all praise. Down to the time of the civil war, he is the greatest figure in our naval history. A thoroughly religious man, he was as generous and humane as he was skilful and brave. One of the greatest of our sea captains, he has left a stainless name behind him."[Back to Contents]

CHAPTER XIV.

ON THE OCEAN. — THE WORK OF THE SLOOPS-OF-WAR. — LOSS OF THE "FROLIC." — FRUITLESS CRUISE OF THE "ADAMS." — THE "PEACOCK" TAKES THE "ÉPERVIER." — THE CRUISE OF THE "WASP." — SHE CAPTURES THE "REINDEER." — SINKS THE "AVON." — MYSTERIOUS END OF THE "WASP."

he opening of the year 1814 found the American coast still rigidly

blockaded by the British men-of-war. Two or three of the enemy lay off

the mouth of every considerable harbor, and were not to be driven from

their post by the icy winds and storms of midwinter on the American

coast. It was almost impossible for any American vessel to escape to

sea, and a matter of almost equal difficulty for such vessels as were

out to get into a home port. The frigate "President" had put to sea

early in December, 1813, and after a cruise of eight weeks, during

which the traditional ill-luck of the ship pursued her remorselessly,

managed to dash into New York Harbor past the blockading squadron. At

Boston the blockade was broken by the "Constitution." She left port on

the 1st of January, ran off to the southward, and cruised (p. 570)

for some weeks in the West Indies. Here she captured the British

man-of-war schooner "Pictou," fourteen guns, and several

merchant-vessels. She also fell in with the British thirty-six-gun

frigate "Pique," which fled, and escaped pursuit by cutting through a

narrow channel during a dark and squally night. The "Constitution"

then returned to the coast of the United States, and narrowly escaped

falling into the clutches of two British frigates. She managed to gain

the shelter of Marblehead Harbor, and there remained until the latter

part of the year.

he opening of the year 1814 found the American coast still rigidly

blockaded by the British men-of-war. Two or three of the enemy lay off

the mouth of every considerable harbor, and were not to be driven from

their post by the icy winds and storms of midwinter on the American

coast. It was almost impossible for any American vessel to escape to

sea, and a matter of almost equal difficulty for such vessels as were

out to get into a home port. The frigate "President" had put to sea

early in December, 1813, and after a cruise of eight weeks, during

which the traditional ill-luck of the ship pursued her remorselessly,

managed to dash into New York Harbor past the blockading squadron. At

Boston the blockade was broken by the "Constitution." She left port on

the 1st of January, ran off to the southward, and cruised (p. 570)

for some weeks in the West Indies. Here she captured the British

man-of-war schooner "Pictou," fourteen guns, and several

merchant-vessels. She also fell in with the British thirty-six-gun

frigate "Pique," which fled, and escaped pursuit by cutting through a

narrow channel during a dark and squally night. The "Constitution"

then returned to the coast of the United States, and narrowly escaped

falling into the clutches of two British frigates. She managed to gain

the shelter of Marblehead Harbor, and there remained until the latter

part of the year.

But, while the larger vessels were thus accomplishing little or nothing, two or three small sloops-of-war, of a class newly built, slipped through the enemy's lines, and, gaining the open sea, fought one or two notable actions. Of these, the first vessel to get to sea was the new sloop-of-war "Frolic;" but her career was short and inglorious, for she had been at sea but a few weeks when she fell in with the enemy's frigate "Orpheus" and the schooner "Shelburne." A chase ensued, in which the American vessel threw overboard her guns and anchors, and started the water; but to no avail, for she was overhauled, and forced to surrender. Her service afloat was limited to the destruction of a Carthagenian privateer, which sunk before her guns, carrying down nearly a hundred men.

The "Adams," a vessel that had suffered many vicissitudes,—having been built for a frigate, then cut down to a sloop-of-war, and finally been sawed asunder and converted into a corvette,—put to sea on the 18th of January, under the command of Capt. Charles Morris, formerly of the "Constitution." She laid her course straight to the eastward, and for some time cruised off the western coast of Africa and the Canary Isles. She met with but little success in this region, capturing only three brigs,—the cargo of one of which consisted of wine and fruit; and the second, of palm-oil and ivory. Abandoning the African coast, the corvette turned westward along the equator, and made for the West Indies. A large Indiaman fell in her way, and was brought to; but, before the Americans could take possession of their prize, a British fleet of twenty-five sail, with two men-of-war, hove in sight, and the "Adams" was forced to seek safety in flight. She put into Savannah for provisions and water, but, hearing that the enemy was in force near by, worked out to sea, and made sail for another cruise. Capt. Morris took up a position on the limits of the Gulf Stream, near the Florida coast, in the expectation of (p. 571) cutting out an Indiaman from some passing convoy. The expected fleet soon came, but was under the protection of a seventy-four, two frigates, and three brigs,—a force sufficient to keep at bay the most audacious of corvettes. Morris hung about the convoy for two days, but saw no chance of eluding the watchful guards. He then crossed the Atlantic to the coast of Ireland. Here the "Adams" narrowly escaped capture; for she was sighted by a frigate, which gave chase, and would have overhauled her, had not the Americans thrown overboard some small cannon, and cut away their anchors. Thus lightened, the corvette sped away, and soon left her pursuers behind.