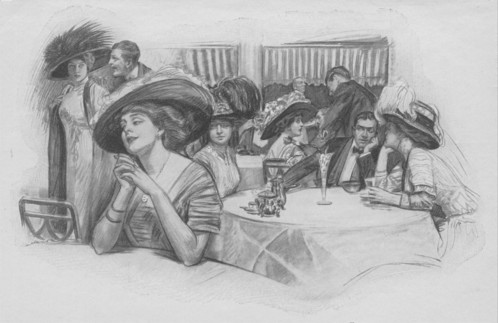

“‘Sisters? Do we look it?’ says Maisie”

Title: Odd Numbers

Author: Sewell Ford

Release date: September 4, 2008 [eBook #26528]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Roger Frank

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

“‘Sisters? Do we look it?’ says Maisie”

ODD NUMBERS

BEING FURTHER CHRONICLES

OF SHORTY McCABE

BY

SEWELL FORD

AUTHOR OF

TRYING OUT TORCHY, ETC.

Illustrations by

F. VAUX WILSON

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1908, 1909, 1910, 1911, by

SEWELL FORD

Copyright, 1912, by

EDWARD J. CLODE

Contents

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Goliah and the Purple Lid | 1 |

| II. | How Maizie Came Through | 17 |

| III. | Where Spotty Fitted In | 35 |

| IV. | A Grandmother Who Got Going | 50 |

| V. | A Long Shot on DeLancey | 67 |

| VI. | Playing Harold Both Ways | 84 |

| VII. | Cornelia Shows Some Class | 100 |

| VIII. | Doping Out an Odd One | 116 |

| IX. | Handing Bobby a Blank | 134 |

| X. | Marmaduke Slips One Over | 151 |

| XI. | A Look In on the Goat Game | 167 |

| XII. | Mrs. Truckles’ Broad Jump | 183 |

| XIII. | Heiney Takes the Gloom Cure | 199 |

| XIV. | A Try-Out for Toodleism | 214 |

| XV. | The Case of the Tiscotts | 230 |

| XVI. | Classing Tutwater Right | 246 |

| XVII. | How Hermy Put It Over | 262 |

| XVIII. | Joy Riding with Aunty | 279 |

| XIX. | Turning a Trick for Beany | 294 |

ODD NUMBERS

One of my highbrow reg’lars at the Physical Culture Studio, a gent that mixes up in charity works, like organizin’ debatin’ societies in the deaf and dumb asylums, was tellin’ me awhile back of a great scheme of his to help out the stranger in our fair village. He wants to open public information bureaus, where a jay might go and find out anything he wanted to know, from how to locate a New Thought church, to the nearest place where he could buy a fresh celluloid collar.

“Get the idea?” says he. “A public bureau where strangers in New York would be given courteous attention, friendly advice, and that sort of thing.”

“What’s the use?” says I. “Ain’t I here?”

Course, I was just gettin’ over a josh. But say, it ain’t all a funny dream, either. Don’t a lot of ’em come my way? Maybe it’s because I’m so apt to lay myself open to the confidential 2 tackle. But somehow, when I see one of these tourist freaks sizin’ me up, and lookin’ kind of dazed and lonesome, I can’t chuck him back the frosty stare. I’ve been a stray in a strange town myself. So I gen’rally tries to seem halfway human, and if he opens up with some shot on the weather, I let him get in the follow-up questions and take the chances.

Here the other day, though, I wa’n’t lookin’ for anything of the kind. I was just joltin’ down my luncheon with a little promenade up the sunny side of Avenue V, taking in the exhibits—things in the show windows and folks on the sidewalks—as keen as if I’d paid in my dollar at some ticket office.

And say, where can you beat it? I see it ’most every day in the year, and it’s always new. There’s different flowers in the florists’ displays, new flags hung out on the big hotels, and even the chorus ladies in the limousines are changed now and then.

I can’t figure out just what it was landed me in front of this millinery window. Gen’rally I hurry by them exhibits with a shudder; for once I got gay and told Sadie to take her pick, as this one was on me; and it was months before I got over the shock of payin’ that bill. But there I finds myself, close up to the plate glass, gawpin’ at a sample of what can be done in the hat line when the Bureau of Obstructions 3 has been bought off and nobody’s thought of applyin’ the statute of limitations.

It’s a heliotrope lid, and the foundation must have used up enough straw to bed down a circus. It has the dimensions and general outlines of a summerhouse. The scheme of decoration is simple enough, though. The top of this heliotrope summerhouse has been caught in a heliotrope fog, that’s all. There’s yards and yards of this gauzy stuff draped and puffed and looped around it, with only a wide purple ribbon showin’ here and there and keepin’ the fog in place.

Well, all that is restin’ careless in a box, the size of a quarter-mile runnin’ track, with the cover half off. And it’s a work of art in itself, that box,—all Looey Cans pictures, and a thick purple silk cord to tie it up with. Why, one glimpse of that combination was enough to make me clap my hand over my roll and back away from the spot!

Just then, though, I notices another gent steppin’ up for a squint at the monstrosity, and I can’t help lingerin’ to see if he gets the same kind of a shock. He’s sort of a queer party, too,—short, stoop shouldered, thin faced, wrinkled old chap, with a sandy mustache mixed some with gray, and a pair of shrewd little eyes peerin’ out under bushy brows. Anybody could spot him as a rutabaga delegate by 4 the high crowned soft hat and the back number ulster that he’s still stickin’ to, though the thermometer is way up in the eighties.

But he don’t seem to shy any at the purple lid. He sticks his head out first this way and then that, like a turtle, and then all of a sudden he shoots over kind of a quizzin’ glance at me. I can’t help but give him the grin. At that his mouth corners wrinkle up and the little gray eyes begin to twinkle.

“Quite a hat, eh?” he chuckles.

“It’s goin’ some in the lid line,” says I.

“I expect that’s a mighty stylish article, though,” says he.

“That’s the bluff the store people are makin’,” says I, “and there’s no law against it.”

“What would be your guess on the price of that there, now?” says he, edging up.

“Ah, let’s leave such harrowin’ details to the man that has to pay for it,” says I. “No use in our gettin’ the chilly spine over what’s marked on the price ticket; that is, unless you’re thinking of investin’,” and as I tips him the humorous wink I starts to move off.

But this wa’n’t a case where I was to get out so easy. He comes right after me. “Excuse me, neighbor,” says he; “but—but that’s exactly what I was thinking of doing, if it wasn’t too infernally expensive.” 5

“What!” says I, gazin’ at him; for he ain’t the kind of citizen you’d expect to find indulgin’ in such foolishness. “Oh, well, don’t mind my remarks. Go ahead and blow yourself. You want it for the missus, eh?”

“Ye-e-es,” he drawls; “for—for my wife. Ah—er—would it be asking too much of a stranger if I should get you to step in there with me while I find out the price?”

“Why,” says I, lookin’ him over careful,—“why, I don’t know as I’d want to go as far as—— Well, what’s the object?”

“You see,” says he, “I’m sort of a bashful person,—always have been,—and I don’t just like to go in there alone amongst all them women folks. But the fact is, I’ve kind of got my mind set on having that hat, and——”

“Wife ain’t in town, then?” says I.

“No,” says he, “she’s—she isn’t.”

“Ain’t you runnin’ some risks,” says I, “loadin’ up with a lid that may not fit her partic’lar style of beauty?”

“That’s so, that’s so,” says he. “Ought to be something that would kind of jibe with her complexion and the color of her hair, hadn’t it?”

“You’ve surrounded the idea,” says I. “Maybe it would be safer to send for her to come on.”

“No,” says he; “couldn’t be done. But see 6 here,” and he takes my arm and steers me up the avenue, “if you don’t mind talking this over, I’d like to tell you a plan I’ve just thought out.”

Well, he’d got me some int’rested in him by that time. I could see he wa’n’t no common Rube, and them twinklin’ little eyes of his kind of got me. So I tells him to reel it off.

“Maybe you never heard of me,” he goes on; “but I’m Goliah Daggett, from South Forks, Iowy.”

“Guess I’ve missed hearin’ of you,” says I.

“I suppose so,” says he, kind of disappointed, though. “The boys out there call me Gol Daggett.”

“Sounds most like a cussword,” says I.

“Yes,” says he; “that’s one reason I’m pretty well known in the State. And there may be other reasons, too.” He lets out a little chuckle at that; not loud, you know, but just as though he was swallowin’ some joke or other. It was a specialty of his, this smothered chuckle business. “Of course,” he goes on, “you needn’t tell me your name, unless——”

“It’s a fair swap,” says I. “Mine’s McCabe; Shorty for short.”

“Yes?” says he. “I knew a McCabe once. He—er—well, he——”

“Never mind,” says I. “It’s a big fam’ly, and there’s only a few of us that’s real credits 7 to the name. But about this scheme of yours, Mr. Daggett?”

“Certainly,” says he. “It’s just this: If I could find a woman who looked a good deal like my wife, I could try the hat on her, couldn’t I? She’d do as well, eh?”

“I don’t know why not,” says I.

“Well,” says he, “I know of just such a woman; saw her this morning in my hotel barber shop, where I dropped in for a haircut. She was one of these—What do you call ’em now?”

“Manicure artists?” says I.

“That’s it,” says he. “Asked me if I didn’t want my fingers manicured; and, by jinks! I let her do it, just to see what it was like. Never felt so blamed foolish in my life! Look at them fingernails, will you? Been parin’ ’em with a jackknife for fifty-seven years; and she soaks ’em out in a bowl of perfumery, jabs under ’em with a little stick wrapped in cotton, cuts off all the hang nails, files ’em round at the ends, and polishes ’em up so they shine as if they were varnished! He, he! Guess the boys would laugh if they could have seen me.”

“It’s one experience you’ve got on me,” says I. “And this manicure lady is a ringer for Mrs. Daggett, eh?”

“Well, now,” says he, scratchin’ his chin, “maybe I ought to put it that she looks a good deal as Mrs. Daggett might have looked ten or 8 fifteen years ago if she’d been got up that way,—same shade of red hair, only not such a thunderin’ lot of it; same kind of blue eyes, only not so wide open and starry; and a nose and chin that I couldn’t help remarking. Course, now, you understand this young woman was fixed up considerable smarter than Mrs. Daggett ever was in her life.”

“If she’s a manicure artist in one of them Broadway hotels,” says I, “I could guess that; specially if Mrs. Daggett’s always stuck to Iowa.”

“Yes, that’s right; she has,” says Daggett. “But if she’d had the same chance to know what to wear and how to wear it——Well, I wish she’d had it, that’s all. And she wanted it. My, my! how she did hanker for such things, Mr. McCabe!”

“Well, better late than never,” says I.

“No, no!” says he, his voice kind of breakin’ up. “That’s what I want to forget, how—how late it is!” and hanged if he don’t have to fish out a handkerchief and swab off his eyes. “You see,” he goes on, “Marthy’s gone.”

“Eh?” says I. “You mean she’s——”

He nods. “Four years ago this spring,” says he. “Typhoid.”

“But,” says I, “how about this hat?”

“One of my notions,” says he,—“just a foolish idea of mine. I’ll tell you. When she 9 was lying there, all white and thin, and not caring whether she ever got up again or not, a new spring hat was the only thing I could get her to take an interest in. She’d never had what you might call a real, bang-up, stylish hat. Always wanted one, too. And it wasn’t because I was such a mean critter that she couldn’t have had the money. But you know how it is in a little place like South Forks. They don’t have ’em in stock, not the kind she wanted, and maybe we couldn’t have found one nearer than Omaha or Chicago; and someway there never was a spring when I could seem to fix things so we could take the trip. Looked kind of foolish, too, traveling so far just to get a hat. So she went without, and put up with what Miss Simmons could trim for her. They looked all right, too, and I used to tell Marthy they were mighty becoming; but all the time I knew they weren’t just—well, you know.”

Say, I never saw any specimens of Miss Simmons’ art works; but I could make a guess. And I nods my head.

“Well,” says Daggett, “when I saw that Marthy was kind of giving up, I used to coax her to get well. ‘You just get on your feet once, Marthy,’ says I, ‘and we’ll go down to Chicago and buy you the finest and stylishest hat we can find in the whole city. More than that, you shall have a new one every spring, the 10 very best.’ She’d almost smile at that, and half promise she’d try. But it wasn’t any use. The fever hadn’t left her strength enough. And the first thing I knew she’d slipped away.”

Odd sort of yarn to be hearin’ there on Fifth-ave. on a sunshiny afternoon, wa’n’t it? And us dodgin’ over crossin’s, and duckin’ under awnin’s, and sidesteppin’ the foot traffic! But he keeps right close to my elbow and gives me the whole story, even to how they’d agreed to use the little knoll just back of the farmhouse as a burial plot, and how she marked the hymns she wanted sung, and how she wanted him to find someone else as soon as the year was out.

“Which was the only thing I couldn’t say yes to,” says Daggett. “‘No, Marthy,’ says I, ‘not unless I can find another just like you.’—‘You’ll be mighty lonesome, Goliah,’ says she, ‘and you’ll be wanting to change your flannels too early.’—‘Maybe so,’ says I; ‘but I guess I’ll worry along for the rest of the time alone.’ Yes, sir, Mr. McCabe, she was a fine woman, and a patient one. No one ever knew how bad she wanted lots of things that she might of had, and gave up. You see, I was pretty deep in the wheat business, and every dollar I could get hold of went to buying more reapers and interests in elevator companies and crop options. I was bound to be a rich man, and they say I got there. Yes, I guess I am fairly well fixed.” 11

It wa’n’t any chesty crow, but more like a sigh, and as we stops on a crossing to let a lady plutess roll by in her brougham, Mr. Daggett he sizes up the costume she wore and shakes his head kind of regretful.

“That’s the way Marthy should have been dressed,” says he. “She’d have liked it. And she’d liked a hat such as that one we saw back there; that is, if it’s the right kind. I’ve been buying ’em kind of careless, maybe.”

“How’s that?” says I.

“Oh!” says he, “I didn’t finish telling you about my fool idea. I’ve been getting one every spring, the best I could pick out in Chicago, and carrying it up there on the knoll where Marthy is—and just leaving it. Go on now, Mr. McCabe; laugh if you want to. I won’t mind. I can almost laugh at myself. Of course, Marthy’s beyond caring for hats now. Still, I like to leave ’em there; and I like to think perhaps she does know, after all. So—so I want to get that purple one, providing it would be the right shade. What do you say?”

Talk about your nutty propositions, eh? But honest, I didn’t feel even like crackin’ a smile.

“Daggett,” says I, “you’re a true sport, even if you have got a few bats in the loft. Let’s go back and get quotations on the lid.”

“I wish,” says he, “I could see it tried on 12 that manicure young woman first. Suppose we go down and bring her up?”

“What makes you think she’ll come?” says I.

“Oh, I guess she will,” says he, quiet and thoughtful. “We’ll try, anyway.”

And say, right there I got a new line on him. I could almost frame up how it was he’d started in as a bacon borrowin’ homesteader, and got to be the John D. of his county. But I could see he was up against a new deal this trip. And as it was time for me to be gettin’ down towards 42d-st. anyway, I goes along. As we strikes the hotel barber shop I hangs up on the end of the cigar counter while Daggett looks around for the young woman who’d put the chappy polish on his nails.

“That’s her,” says he, pointing out a heavyweight Titian blonde in the far corner, and over he pikes.

I couldn’t help admirin’ the nerve of him; for of all the l’ongoline queens I ever saw, she’s about the haughtiest. Maybe you can throw on the screen a picture of a female party with a Lillian Russell shape, hair like Mrs. Leslie Carter’s, and an air like a twelve-dollar cloak model showin’ off a five hundred-dollar lace dress to a bookmaker’s bride.

Just as Daggett tiptoes up she’s pattin’ down some of the red puffs that makes the back of 13 her head look like a burnin’ oil tank, and she swings around languid and scornful to see who it is that dares butt in on her presence. All the way she recognizes him is by a little lift of the eyebrows.

I don’t need to hear the dialogue. I can tell by her expression what Daggett is saying. First there’s a kind of condescendin’ curiosity as he begins, then she looks bored and turns back to the mirror, and pretty soon she sings out, “What’s that?” so you could hear her all over the shop. Then Daggett springs his proposition flat.

“Sir!” says she, jumpin’ up and glarin’ at him.

Daggett tries to soothe her down; but it’s no go.

“Mr. Heinmuller!” she calls out, and the boss barber comes steppin’ over, leavin’ a customer with his face muffled in a hot towel. “This person,” she goes on, “is insulting!”

“Hey?” says Heinmuller, puffin’ out his cheeks. “Vos iss dot?”

And for a minute it looked like I’d have to jump in and save Daggett from being chucked through the window. I was just preparin’ to grab the boss by the collar, too, when Daggett gets in his fine work. Slippin’ a ten off his roll, he passes it to Heinmuller, while he explains that all he asked of the lady was to try 14 on a hat he was thinkin’ of gettin’ for his wife.

“That’s all,” says he. “No insult intended. And of course I expect to make it worth while for the young lady.”

I don’t know whether it was the smooth “young lady” business, or the sight of the fat roll that turned the trick; but the tragedy is declared off. Inside of three minutes the boss tells Daggett that Miss Rooney accepts his apology and consents to go if he’ll call a cab.

“Why, surely,” says he. “You’ll come along, too, won’t you, McCabe? Honest, now, I wouldn’t dare do this alone.”

“Too bad about that shy, retirin’ disposition of yours!” says I. “Afraid she’ll steal you, eh?”

But he hangs onto my sleeve and coaxes me until I give in. And we sure made a fine trio ridin’ up Fifth-ave. in a taxi! But you should have seen ’em in the millinery shop as we sails in with Miss Rooney, and Daggett says how he’d like a view of that heliotrope lid in the window. We had ’em guessin’, all right.

Then they gets Miss Rooney in a chair before the mirror, and fits the monstrosity on top of her red hair. Well, say, what a diff’rence it does make in them freak bonnets whether they’re in a box or on the right head! For Miss Rooney has got just the right kind of a 15 face that hat was built to go with. It’s a bit giddy, I’ll admit; but she’s a stunner in it. And does she notice it any herself? Well, some!

“A triumph!” gurgles the saleslady, lookin’ from one to the other of us, tryin’ to figure out who she ought to play to.

“It’s a game combination, all right,” says I, lookin’ wise.

“I only wish——” begins Daggett, and then swallows the rest of it. In a minute he steps up and says it’ll do, and that the young lady is to pick out one for herself now.

“Oh, how perfectly sweet of you!” says Miss Rooney, slippin’ him a smile that should have had him clear through the ropes. “But if I am to have any, why not this?” and she balances the heliotrope lid on her fingers, lookin’ it over yearnin’ and tender. “It just suits me, doesn’t it?”

Then there’s more of the coy business, aimed straight at Daggett. But Miss Rooney don’t quite put it across.

“That’s going out to Iowy with me,” says he, prompt and decided.

“Oh!” says Miss Rooney, and she proceeds to pick out a white straw with a green ostrich feather a yard long. She was still lookin’ puzzled, though, as we put her into the cab and started her back to the barber shop. 16

“Must have set you back near a hundred, didn’t they?” says I, as Daggett and I parts on the corner.

“Almost,” says he. “But it’s worth it. Marthy would have looked mighty stylish in that purple one. Yes, yes! And when I get back to South Forks, the first thing I do will be to carry it up on the knoll, box and all, and leave it there. I wonder if she’ll know, eh?”

There wa’n’t any use in my tellin’ him what I thought, though. He wa’n’t talkin’ to me, anyway. There was a kind of a far off, batty look in his eyes as he stood there on the corner, and a drop of brine was tricklin’ down one side of his nose. So we never says a word, but just shakes hands, him goin’ his way, and me mine.

“Chee!” says Swifty Joe, when I shows up, along about three o’clock, “you must have been puttin’ away a hearty lunch!”

“It wa’n’t that kept me,” says I. “I was helpin’ hand a late one to Marthy.”

Then again, there’s other kinds from other States, and no two of ’em alike. They float in from all quarters, some on ten-day excursions, and some with no return ticket. And, of course, they’re all jokes to us at first, while we never suspicion that all along we may be jokes to them.

And say, between you and me, we’re apt to think, ain’t we, that all the rapid motion in the world gets its start right here in New York? Well, that’s the wrong dope. For instance, once I got next to a super-energized specimen that come in from the north end of nowhere, and before I was through the experience had left me out of breath.

It was while Sadie and me was livin’ at the Perzazzer hotel, before we moved out to Rockhurst-on-the-Sound. Early one evenin’ we was sittin’, as quiet and domestic as you please, in our twelve by fourteen cabinet finished dinin’ room on the seventh floor. We was gazin’ out of the open windows watchin’ a thunder storm meander over towards Long Island, and Tidson 18 was just servin’ the demitasses, when there’s a ring on the ’phone. Tidson, he puts down the tray and answers the call.

“It’s from the office, sir,” says he. “Some one to see you, sir.”

“Me?” says I. “Get a description, Tidson, so I’ll know what to expect.”

At that he asks the room clerk for details, and reports that it’s two young ladies by the name of Blickens.

“What!” says Sadie, prickin’ up her ears. “You don’t know any young women of that name; do you, Shorty?”

“Why not?” says I. “How can I tell until I’ve looked ’em over?”

“Humph!” says she. “Blickens!”

“Sounds nice, don’t it?” says I. “Kind of snappy and interestin’. Maybe I’d better go down and——”

“Tidson,” says Sadie, “tell them to send those young persons up here!”

“That’s right, Tidson,” says I. “Don’t mind anything I say.”

“Blickens, indeed!” says Sadie, eyin’ me sharp, to see if I’m blushin’ or gettin’ nervous. “I never heard you mention any such name.”

“There’s a few points about my past life,” says I, “that I’ve had sense enough to keep to myself. Maybe this is one. Course, if your curiosity——” 19

“I’m not a bit curious, Shorty McCabe,” she snaps out, “and you know it! But when it comes to——”

“The Misses Blickens,” says Tidson, holdin’ back the draperies with one hand, and smotherin’ a grin with the other.

Say, you couldn’t blame him. What steps in is a couple of drippy females that look like they’d just been fished out of a tank. And bein’ wet wa’n’t the worst of it. Even if they’d been dry, they must have looked bad enough; but in the soggy state they was the limit.

They wa’n’t mates. One is tall and willowy, while the other is short and dumpy. And the fat one has the most peaceful face I ever saw outside of a pasture, with a reg’lar Holstein-Friesian set of eyes,—the round, calm, thoughtless kind. The fact that she’s chewin’ gum helps out the dairy impression, too. It’s plain she’s been caught in the shower and has sopped up her full share of the rainfall; but it don’t seem to trouble her any.

There ain’t anything pastoral about the tall one, though. She’s alive all the way from her runover heels to the wiggly end of the limp feather that flops careless like over one ear. She’s the long-waisted, giraffe-necked kind; but not such a bad looker if you can forget the depressin’ costume. It had been a blue cheviot once, I guess; the sort that takes on seven 20 shades of purple about the second season. And it fits her like a damp tablecloth hung on a chair. Her runnin’ mate is all in black, and you could tell by the puckered seams and the twisted sleeves that it was an outfit the village dressmaker had done her worst on.

Not that they gives us much chance for a close size-up. The lengthy one pikes right into the middle of the room, brushes a stringy lock of hair off her face, and unlimbers her conversation works.

“Gosh!” says she, openin’ her eyes wide and lookin’ round at the rugs and furniture. “Hope we haven’t pulled up at the wrong ranch. Are you Shorty McCabe?”

“Among old friends, I am,” says I, “Now if you come under——”

“It’s all right, Phemey,” says she, motionin’ to the short one. “Sit down.”

“Sure!” says I. “Don’t mind the furniture. Take a couple of chairs.”

“Not for me!” says the tall one. “I’ll stand in one spot and drip, and then you can mop up afterwards. But Phemey, she’s plumb tuckered.”

“It’s sweet of you to run in,” says I. “Been wadin’ in the park lake, or enjoyin’ the shower?”

“Enjoying the shower is good,” says she; “but I hadn’t thought of describing it that 21 way. I reckon, though, you’d like to hear who we are.”

“Oh, any time when you get to that,” says I.

“That’s a joke, is it?” says she. “If it is, Ha, ha! Excuse me if I don’t laugh real hearty. I can do better when I don’t feel so much like a sponge. Maizie May Blickens is my name, and this is Euphemia Blickens.”

“Ah!” says I. “Sisters?”

“Do we look it?” says Maizie. “No! First cousins on the whiskered side. Ever hear that name Blickens before?”

“Why—er—why——” says I, scratchin’ my head.

“Don’t dig too deep,” says Maizie. “How about Blickens’ skating rink in Kansas City?”

“Oh!” says I. “Was it run by a gent they called Sport Blickens?”

“It was,” says she.

“Why, sure,” I goes on. “And the night I had my match there with the Pedlar, when I’d spent my last bean on a month’s trainin’ expenses, and the Pedlar’s backer was wavin’ a thousand-dollar side bet under my nose, this Mr. Blickens chucked me his roll and told me to call the bluff.”

“Yes, that was dad, all right,” says Maizie.

“It was?” says I. “Well, well! Now if there’s anything I can do for——”

“Whoa up!” says Maizie. “This is no 22 grubstake touch. Let’s get that off our minds first, though I’m just as much obliged. It’s come out as dad said. Says he, ‘If you’re ever up against it, and can locate Shorty McCabe, you go to him and say who you are.’ But this isn’t exactly that kind of a case. Phemey and I may look a bit rocky and—— Say, how do we look, anyway? Have you got such a thing as a——”

“Tidson,” says Sadie, breakin’ in, “you may roll in the pier glass for the young lady.” Course, that reminds me I ain’t done the honors.

“Excuse me,” says I. “Miss Blickens, this is Mrs. McCabe.”

“Howdy,” says Maizie. “I was wondering if it wasn’t about due. Goshety gosh! but you’re all to the peaches, eh? And me——”

Here she turns and takes a full length view of herself. “Suffering scarecrows! Say, why didn’t you put up the bars on us? Don’t you look, Phemey; you’d swallow your gum!”

But Euphemia ain’t got any idea of turnin’ her head. She has them peaceful eyes of hers glued to Sadie’s copper hair, and she’s contented to yank away at her cud. For a consistent and perseverin’ masticator, she has our friend Fletcher chewed to a standstill. Maizie is soon satisfied with her survey.

“That’ll do, take it away,” says she. “If I ever get real stuck on myself, I’ll have something 23 to remember. But, as I was sayin’, this is no case of an escape from the poor farm. We wore these Hetty Green togs when we left Dobie.”

“Dobie?” says I.

“Go on, laugh!” says Maizie. “Dobie’s the biggest joke and the slowest four corners in the State of Minnesota, and that’s putting it strong. Look at Phemey; she’s a native.”

Well, we looked at Phemey. Couldn’t help it. Euphemia don’t seem to mind. She don’t even grin; but just goes on workin’ her jaws and lookin’ placid.

“Out in Dobie that would pass for hysterics,” says Maizie. “The only way they could account for me was by saying that I was born crazy in another State. I’ve had a good many kinds of hard luck; but being born in Dobie wasn’t one of the varieties. Now can you stand the story of my life?”

“Miss Blickens,” says I, “I’m willin’ to pay you by the hour.”

“It isn’t so bad as all that,” says she, “because precious little has ever happened to me. It’s what’s going to happen that I’m living for. But, to take a fair start, we’ll begin with dad. When they called him Sport Blickens, they didn’t stretch their imaginations. He was all that—and not much else. All I know about maw is that she was one of three, and that I was 24 born in the back room of a Denver dance hall. I’ve got a picture of her, wearing tights and a tin helmet, and dad says she was a hummer. He ought to know; he was a pretty good judge.

“As I wasn’t much over two days old when they had the funeral, I can’t add anything more about maw. And the history I could write of dad would make a mighty slim book. Running roller skating rinks was the most genteel business he ever got into, I guess. His regular profession was faro. It’s an unhealthy game, especially in those gold camps where they shoot so impetuous. He got over the effects of two .38’s dealt him by a halfbreed Sioux; but when a real bad man from Taunton, Massachusetts, opened up on him across the table with a .45, he just naturally got discouraged. Good old dad! He meant well when he left me in Dobie and had me adopted by Uncle Hen. Phemey, you needn’t listen to this next chapter.”

Euphemia, she misses two jaw strokes in succession, rolls her eyes at Maizie May for a second, and then strikes her reg’lar gait again.

“Excuse her getting excited like that,” says Maizie; “but Uncle Hen—that was her old man, of course—hasn’t been planted long. He lasted until three weeks ago. He was an awful good man, Uncle Hen was—to himself. He had the worst case of ingrowing religion you ever saw. Why, he had a thumb felon once, and 25 when the doctor came to lance it Uncle Hen made him wait until he could call in the minister, so it could be opened with prayer.

“Sundays he made us go to church twice, and the rest of the day he talked to us about our souls. Between times he ran the Palace Emporium; that is, he and I and a half baked Swede by the name of Jens Torkil did. To look at Jens you wouldn’t have thought he could have been taught the difference between a can of salmon and a patent corn planter; but say, Uncle Hen had him trained to make short change and weigh his hand with every piece of salt pork, almost as slick as he could do it himself.

“All I had to do was to tend the drygoods, candy, and drug counters, look after the post-office window, keep the books, and manage the telephone exchange. Euphemia had the softest snap, though. She did the housework, planted the garden, raised chickens, fed the hogs, and scrubbed the floors. Have I got the catalogue right, Phemey?”

Euphemia blinks twice, kind of reminiscent; but nothin’ in the shape of words gets through the gum.

“She has such an emotional nature!” says Maizie. “Uncle Hen was like that too. But let’s not linger over him. He’s gone. The last thing he did was to let go of a dollar fifty in 26 cash that I held him up for so Phemey and I could go into Duluth and see a show. The end came early next day, and whether it was from shock or enlargement of the heart, no one will ever know.

“It was an awful blow to us all. We went around in a daze for nearly a week, hardly daring to believe that it could be so. Jens broke the spell for us. One morning I caught him helping himself to a cigar out of the two-fer box. ‘Why not?’ says he. Next Phemey walks in, swipes a package of wintergreen gum, and feeds it all in at once. She says, ‘Why not?’ too. Then I woke up. ‘You’re right,’ says I. ‘Enjoy yourself. It’s time.’ Next I hints to her that there are bigger and brighter spots on this earth than Dobie, and asks her what she says to selling the Emporium and hunting them up. ‘I don’t care,’ says she, and that was a good deal of a speech for her to make. ‘Do you leave it to me?’ says I. ‘Uh-huh,’ says she. ‘We-e-e-ough!’ says I,” and with that Maizie lets out one of them backwoods college cries that brings Tidson up on his toes.

“I take it,” says I, “that you did.”

“Did I?” says she. “Inside of three days I’d hustled up four different parties that wanted to invest in a going concern, and before the week was over I’d buncoed one of ’em 27 out of nine thousand in cash. Most of it’s in a certified check, sewed inside of Phemey, and that’s why we walked all the way up here in the rain. Do you suppose you could take me to some bank to-morrow where I could leave that and get a handful of green bills on account? Is that asking too much?”

“Considering the way you’ve brushed up my memory of Sport Blickens,” says I, “it’s real modest. Couldn’t you think of something else?”

“If that had come from Mrs. McCabe,” says she, eyin’ Sadie kind of longin’, “I reckon I could.”

“Why,” says Sadie, “I should be delighted.”

“You wouldn’t go so far as to lead two such freaks as us around to the stores and help us pick out some New York clothes, would you?” says she.

“My dear girl!” says Sadie, grabbin’ both her hands. “We’ll do it to-morrow.”

“Honest?” says Maizie, beamin’ on her. “Well, that’s what I call right down decent. Phemey, do you hear that? Oh, swallow it, Phemey, swallow it! This is where we bloom out!”

And say, you should have heard them talkin’ over the kind of trousseaus that would best help a girl to forget she ever came from Dobie. 28

“You will need a neat cloth street dress, for afternoons,” says Sadie.

“Not for me!” says Maizie. “That’ll do all right for Phemey; but when it comes to me, I’ll take something that rustles. I’ve worn back number cast-offs for twenty-two years; now I’m ready for the other kind. I’ve been traveling so far behind the procession I couldn’t tell which way it was going. Now I’m going to give the drum major a view of my back hair. The sort of costumes I want are the kind that are designed this afternoon for day after to-morrow. If it’s checks, I’ll take two to the piece; if it’s stripes, I want to make a circus zebra look like a clipped mule. And I want a change for every day in the week.”

“But, my dear girl,” says Sadie, “can you afford to——”

“You bet I can!” says Maizie. “My share of Uncle Hen’s pile is forty-five hundred dollars, and while it lasts I’m going to have the lilies of the field looking like the flowers you see on attic wall paper. I don’t care what I have to eat, or where I stay; but when it comes to clothes, show me the limit! But say, I guess it’s time we were getting back to our boarding-house. Wake up, Phemey!”

Well, I pilots ’em out to Fifth-ave., stows ’em into a motor stage, and heads ’em down town.

“Whew!” says Sadie, when I gets back. “I 29 suppose that is a sample of Western breeziness.”

“It’s more’n a sample,” says I. “But I can see her finish, though. Inside of three months all she’ll have left to show for her wad will be a trunk full of fancy regalia and a board bill. Then it will be Maizie hunting a job in some beanery.”

“Oh, I shall talk her out of that nonsense,” says Sadie. “What she ought to do is to take a course in stenography and shorthand.”

Yes, we laid out a full programme for Maizie, and had her earnin’ her little twenty a week, with Phemey keepin’ house for both of ’em in a nice little four-room flat. And in the mornin’ I helps her deposit the certified check, and then turns the pair over to Sadie for an assault on the department stores, with a call at a business college as a finish for the day, as we’d planned.

When I gets home that night I finds Sadie all fagged out and drinkin’ bromo seltzer for a headache.

“What’s wrong?” says I.

“Nothing,” says Sadie; “only I’ve been having the time of my life.”

“Buying tailor made uniforms for the Misses Blickens?” says I.

“Tailor made nothing!” says Sadie. “It was no use, Shorty, I had to give in. Maizie wanted the other things so badly. And then 30 Euphemia declared she must have the same kind. So I spent the whole day fitting them out.”

“Got ’em something sudden and noisy, eh?” says I.

“Just wait until you see them,” says Sadie.

“But what’s the idea?” says I. “How long do they think they can keep up that pace? And when they’ve blown themselves short of breath, what then?”

“Heaven knows!” says Sadie. “But Maizie has plans of her own. When I mentioned the business college, she just laughed, and said if she couldn’t do something better than pound a typewriter, she’d go back to Dobie.”

“Huh!” says I. “Sentiments like that has got lots of folks into trouble.”

“And yet,” says Sadie, “Maizie’s a nice girl in her way. We’ll see how she comes out.”

We did, too. It was a couple of weeks before we heard a word from either of ’em, and then the other day Sadie gets a call over the ’phone from a perfect stranger. She says she’s a Mrs. Herman Zorn, of West End-ave., and that she’s givin’ a little roof garden theater party that evenin’, in honor of Miss Maizie Blickens, an old friend of hers that she used to know when she lived in St. Paul and spent her summers near Dobie. Also she understood we were 31 friends of Miss Blickens too, and she’d be pleased to have us join.

“West End-ave.!” says I. “Gee! but it looks like Maizie had been able to butt in. Do we go, Sadie?”

“I said we’d be charmed,” says she. “I’m dying to see how Maizie will look.”

I didn’t admit it, but I was some curious that way myself; so about eight-fifteen we shows up at the roof garden and has an usher lead us to the bunch. There’s half a dozen of ’em on hand; but the only thing worth lookin’ at was Maizie May.

And say, I thought I could make a guess as to somewhere near how she would frame up. The picture I had in mind was a sort of cross between a Grand-st. Rebecca and an Eighth-ave. Lizzie Maud,—you know, one of the near style girls, that’s got on all the novelties from ten bargain counters. But, gee! The view I gets has me gaspin’. Maizie wa’n’t near; she was two jumps ahead. And it wa’n’t any Grand-st. fashion plate that she was a livin’ model of. It was Fifth-ave. and upper Broadway. Talk about your down-to-the-minute costumes! Say, maybe they’ll be wearin’ dresses like that a year from now. And that hat! It wa’n’t a dream; it was a forecast.

“We saw it unpacked from the Paris case,” whispers Sadie. 32

All I know about it is that it was the widest, featheriest lid I ever saw in captivity, and it’s balanced on more hair puffs than you could put in a barrel. But what added the swell, artistic touch was the collar. It’s a chin supporter and ear embracer. I thought I’d seen high ones, but this twelve-inch picket fence around Maizie’s neck was the loftiest choker I ever saw anyone survive. To watch her wear it gave you the same sensations as bein’ a witness at a hanging. How she could do it and keep on breathin’, I couldn’t make out; but it don’t seem to interfere with her talkin’.

Sittin’ close up beside her, and listenin’ with both ears stretched and his mouth open, was a blond young gent with a bristly Bat Nelson pompadour. He’s rigged out in a silk faced tuxedo, a smoke colored, open face vest, and he has a big yellow orchid in his buttonhole. By the way he’s gazin’ at Maizie, you could tell he approved of her from the ground up. She don’t hesitate any on droppin’ him, though, when we arrives.

“Hello!” says she. “Ripping good of you to come. Well, what do you think? I’ve got some of ’em on, you see. What’s the effect?”

“Stunning!” says Sadie.

“Thanks,” says Maizie. “I laid out to get somewhere near that. And, gosh! but it feels good! These are the kind of togs I was born to 33 wear. Phemey? Oh, she’s laid up with arnica bandages around her throat. I told her she mustn’t try to chew gum with one of these collars on.”

“Say, Maizie,” says I, “who’s the Sir Lionel Budweiser, and where did you pick him up?”

“Oh, Oscar!” says she. “Why, he found me. He’s from St. Paul, nephew of Mrs. Zorn, who’s visiting her. Brewer’s son, you know. Money? They’ve got bales of it. Hey, Oscar!” says she, snappin’ her finger. “Come over here and show yourself!”

And say, he was trained, all right. He trots right over.

“Would you take him, if you was me?” says Maizie, turnin’ him round for us to make an inspection. “I told him I wouldn’t say positive until I had shown him to you, Mrs. McCabe. He’s a little under height, and I don’t like the way his hair grows; but his habits are good, and his allowance is thirty thousand a year. How about him? Will he do?”

“Why—why——” says Sadie, and it’s one of the few times I ever saw her rattled.

“Just flash that ring again, Oscar,” says Maizie.

“O-o-oh!” says Sadie, when Oscar has pulled out the white satin box and snapped back the cover. “What a beauty! Yes, Maizie, I 34 should say that, if you like Oscar, he would do nicely.”

“That goes!” says Maizie. “Here, Occie dear, slide it on. But remember: Phemey has got to live with us until I can pick out some victim of nervous prostration that needs a wife like her. And for goodness’ sake, Occie, give that waiter an order for something wet!”

“Well!” says Sadie afterwards, lettin’ out a long breath. “To think that we ever worried about her!”

“She’s a little bit of all right, eh?” says I. “But say, I’m glad I ain’t Occie, the heir to the brewery. I wouldn’t know whether I was engaged to Maizie, or caught in a belt.”

Also we have a few home-grown varieties that ain’t listed frequent. And the pavement products are apt to have most as queer kinks to ’em as those from the plowed fields. Now take Spotty.

“Gee! what a merry look!” says I to Pinckney as he floats into the studio here the other day. He’s holdin’ his chin high, and he’s got his stick tucked up under his arm, and them black eyes of his is just sparklin’. “What’s it all about?” I goes on. “Is it a good one you’ve just remembered, or has something humorous happened to one of your best friends?”

“I have a new idea,” says he, “that’s all.”

“All!” says I. “Why, that’s excuse enough for declarin’ a gen’ral holiday. Did you go after it, or was it delivered by mistake? Can’t you give us a scenario of it?”

“Why, I’ve thought of something new for Spotty Cahill,” says he, beamin’.

“G’wan!” says I. “I might have known it was a false alarm. Spotty Cahill! Say, do 36 you want to know what I’d advise you to do for Spotty next?”

No, Pinckney don’t want my views on the subject. It’s a topic we’ve threshed out between us before; also it’s one of the few dozen that we could debate from now until there’s skatin’ on the Panama Canal, without gettin’ anywhere. I’ve always held that Spotty Cahill was about the most useless and undeservin’ human being that ever managed to exist without work; but to hear Pinckney talk you’d think that long-legged, carroty-haired young loafer was the original party that philanthropy was invented for.

Now, doing things for other folks ain’t one of Pinckney’s strong points, as a rule. Not that he wouldn’t if he thought of it and could find the time; but gen’rally he has too many other things on his schedule to indulge much in the little deeds of kindness game. When he does start out to do good, though, he makes a job of it. But look who he picks out!

Course, I knew why. He’s explained all that to me more’n once. Seems there was an old waiter at the club, a quiet, soft-spoken, bald-headed relic, who had served him with more lobster Newburg than you could load on a scow, and enough highballs to float the Mauretania in. In fact, he’d been waitin’ there as long as Pinckney had been a member. They’d 37 been kind of chummy, in a way, too. It had always been “Good morning, Peter,” and “Hope I see you well, sir,” between them, and Pinckney never had to bother about whether he liked a dash of bitters in this, or if that ought to be served frappe or plain. Peter knew, and Peter never forgot.

Then one day when Pinckney’s just squarin’ off to his lunch he notices that he’s been given plain, ordinary salt butter instead of the sweet kind he always has; so he puts up a finger to call Peter over and have a swap made. When he glances up, though, he finds Peter ain’t there at all.

“Oh, I say,” says he, “but where is Peter?”

“Peter, sir?” says the new man. “Very sorry, sir, but Peter’s dead.”

“Dead!” says Pinckney. “Why—why—how long has that been?”

“Over a month, sir,” says he. “Anything wrong, sir?”

To be sure, Pinckney hadn’t been there reg’lar; but he’d been in off and on, and when he comes to think how this old chap, that knew all his whims, and kept track of ’em so faithful, had dropped out without his ever having heard a word about it—why, he felt kind of broke up. You see, he’d always meant to do something nice for old Peter; but he’d never got round to it, 38 and here the first thing he knows Peter’s been under the sod for more’n a month.

That’s what set Pinckney to inquirin’ if Peter hadn’t left a fam’ly or anything, which results in his diggin’ up this Spotty youth. I forgot just what his first name was, it being something outlandish that don’t go with Cahill at all; but it seems he was born over in India, where old Peter was soldierin’ at the time, and they’d picked up one of the native names. Maybe that’s what ailed the boy from the start.

Anyway, Peter had come back from there a widower, drifted to New York with the youngster, and got into the waiter business. Meantime the boy grows up in East Side boardin’-houses, without much lookin’ after, and when Pinckney finds him he’s an int’restin’ product. He’s twenty-odd, about five feet eleven high, weighs under one hundred and thirty, has a shock of wavy, brick-red hair that almost hides his ears, and his chief accomplishments are playin’ Kelly pool and consumin’ cigarettes. By way of ornament he has the most complete collection of freckles I ever see on a human face, or else it was they stood out more prominent because the skin was so white between the splotches. We didn’t invent the name Spotty for him. He’d already been tagged that.

Well, Pinckney discovers that Spotty has been livin’ on the few dollars that was left after 39 payin’ old Peter’s plantin’ expenses; that he didn’t know what he was goin’ to do after that was gone, and didn’t seem to care. So Pinckney jumps in, works his pull with the steward, and has Spotty put on reg’lar in the club billiard room as an attendant. All he has to do is help with the cleanin’, keep the tables brushed, and set up the balls when there are games goin’ on. He gets his meals free, and six dollars a week.

Now that should have been a soft enough snap for anybody, even the born tired kind. There wa’n’t work enough in it to raise a palm callous on a baby. But Spotty, he improves on that. His idea of earnin’ wages is to curl up in a sunny windowseat and commune with his soul. Wherever you found the sun streamin’ in, there was a good place to look for Spotty. He just seemed to soak it up, like a blotter does ink, and it didn’t disturb him any who was doin’ his work.

Durin’ the first six months Spotty was fired eight times, only to have Pinckney get him reinstated, and it wa’n’t until the steward went to the board of governors with the row that Mr. Cahill was given his permanent release. You might think Pinckney would have called it quits then; but not him! He’d started out to godfather Spotty, and he stays right with the game. Everybody he knew was invited to help along the good work of givin’ Spotty a lift. He 40 got him into brokers’ offices, tried him out as bellhop in four diff’rent hotels, and even jammed him by main strength into a bank; but Spotty’s sun absorbin’ habits couldn’t seem to be made useful anywhere.

For one while he got chummy with Swifty Joe and took to sunnin’ himself in the studio front windows, until I had to veto that.

“I don’t mind your friends droppin’ in now and then, Swifty,” says I; “but there ain’t any room here for statuary. I don’t care how gentle you break it to him, only run him out.”

So that’s why I don’t enthuse much when Pinckney says he’s thought up some new scheme for Spotty. “Goin’ to have him probed for hookworms?” says I.

No, that ain’t it. Pinckney, he’s had a talk with Spotty and discovered that old Peter had a brother Aloysius, who’s settled somewhere up in Canada and is superintendent of a big wheat farm. Pinckney’s had his lawyers trace out this Uncle Aloysius, and then he’s written him all about Spotty, suggestin’ that he send for him by return mail.

“Fine!” says I. “He’d be a lot of use on a wheat farm. What does Aloysius have to say to the proposition?”

“Well, the fact is,” says Pinckney, “he doesn’t appear at all enthusiastic. He writes that if the boy is anything like Peter when he 41 knew him he’s not anxious to see him. However, he says that if Spotty comes on he will do what he can for him.”

“It’ll be a long walk,” says I.

“There’s where my idea comes in,” says Pinckney. “I am going to finance the trip.”

“If it don’t cost too much,” says I, “it’ll be a good investment.”

Pinckney wants to do the thing right away, too. First off, though, he has to locate Spotty. The youth has been at large for a week or more now, since he was last handed the fresh air, and Pinckney ain’t heard a word from him.

“Maybe Swifty knows where he roosts,” says I.

It was a good guess. Swifty gives us a number on Fourth-ave. where he’d seen Spotty hangin’ around lately, and he thinks likely he’s there yet.

So me and Pinckney starts out on the trail. It leads us to one of them Turkish auction joints where they sell genuine silk oriental prayer rugs, made in Paterson, N. J., with hammered brass bowls and antique guns as a side line. And, sure enough, camped down in front on a sample rug, with his hat off and the sun full on him, is our friend Spotty.

“Well, well!” says Pinckney. “Regularly employed here, are you, Spotty?”

“Me? Nah!” says Spotty, lookin’ disgusted 42 at the thought. “I’m only stayin’ around.”

“Ain’t you afraid the sun will fade them curly locks of yours?” says I.

“Ah, quit your kiddin’!” says Spotty, startin’ to roll a fresh cigarette.

“Don’t mind Shorty,” says Pinckney. “I have some good news for you.”

That don’t excite Spotty a bit. “Not another job!” he groans.

“No, no,” says Pinckney, and then he explains about finding Uncle Aloysius, windin’ up by askin’ Spotty how he’d like to go up there and live.

“I don’t know,” says Spotty. “Good ways off, ain’t it!”

“It is, rather,” admits Pinckney; “but that need not trouble you. What do you think I am going to do for you, Spotty?”

“Give it up,” says he, calmly lightin’ a match and proceedin’ with the smoke.

“Well,” says Pinckney, “because of the long and faithful service of your father, and the many little personal attentions he paid me, I am going to give you—— Wait! Here it is now,” and hanged if Pinckney don’t fork over ten new twenty-dollar bills. “There!” says he. “That ought to be enough to fit you out well and take you there in good shape. Here’s the address too.” 43

Does Spotty jump up and crack his heels together and sputter out how thankful he is? Nothin’ so strenuous. He fumbles the bills over curious for a minute, then wads ’em up and jams ’em into his pocket. “Much obliged,” says he.

“Come around to Shorty’s with your new clothes on to-morrow afternoon about four o’clock,” says Pinckney, “and let us see how you look. And—er—by the way, Spotty, is that a friend of yours?”

I’d been noticin’ her too, standin’ just inside the doorway pipin’ us off. She’s a slim, big-eyed, black-haired young woman, dressed in the height of Grand-st. fashion, and wearin’ a lot of odd, cheap lookin’ jewelry. If it hadn’t been for the straight nose and the thin lips you might have guessed that her first name was Rebecca.

“Oh, her?” says Spotty, turnin’ languid to see who he meant. “That’s Mareena. Her father runs the shop.”

“Armenian?” says I.

“No, Syrian,” says he.

“Quite some of a looker, eh?” says I, tryin’ to sound him.

“Not so bad,” says Spotty, hunchin’ his shoulders.

“But—er—do I understand,” says Pinckney, “that there is—ah—some attachment between you and—er—the young lady?” 44

“Blamed if I know,” says Spotty. “Better ask her.”

Course, we couldn’t very well do that, and as Spotty don’t seem bubblin’ over with information he has to chop it off there. Pinckney, though, is more or less int’rested in the situation. He wonders if he’s done just right, handin’ over all that money to Spotty in a place like that.

“It wa’n’t what you’d call a shrewd move,” says I. “Seems to me I’d bought his ticket, anyway.”

“Yes; but I wanted to get it off my mind, you know,” says he. “Odd, though, his being there. I wonder what sort of persons those Syrians are!”

“You never can tell,” says I.

The more Pinckney thinks of it, the more uneasy he gets, and when four o’clock comes next day, with no Spotty showin’ up, he begins to have furrows in his brow. “If he’s been done away with, it’s my fault,” says Pinckney.

“Ah, don’t start worryin’ yet,” says I. “Give him time.”

By five o’clock, though, Pinckney has imagined all sorts of things,—Spotty bein’ found carved up and sewed in a sack, and him called into court to testify as to where he saw him last. “And all because I gave him that money!” he groans. 45

“Say, can it!” says I. “Them sensation pictures of yours are makin’ me nervous. Here, I’ll go down and see if they’ve finished wipin’ off the daggers, while you send Swifty out after something soothin’.”

With that off I hikes as a rescue expedition. I finds the red flag still out, the sample rug still in place; but there’s no Spotty in evidence. Neither is there any sign of the girl. So I walks into the store, gazin’ around sharp for any stains on the floor.

Out from behind a curtain at the far end of the shop comes a fat, wicked lookin’ old pirate, with a dark greasy face and shiny little eyes like a pair of needles. He’s wearin’ a dinky gold-braided cap, baggy trousers, and he carries a long pipe in one hand. If he didn’t look like he’d do extemporaneous surgery for the sake of a dollar bill, then I’m no judge. I’ve got in too far to look up a cop, so I takes a chance on a strong bluff.

“Say, you!” I sings out. “What’s happened to Spotty?”

“Spot-tee?” says he. “Spot-tee?” He shrugs his shoulders and pretends to look dazed.

“Yes, Spotty,” says I, “red-headed, freckle-faced young gent. You know him.”

“Ah!” says he, tappin’ his head. “The golden crowned! El Sareef Ka-heel?” 46

“That’s the name, Cahill,” says I. “He’s a friend of a friend of mine, and you might as well get it through your nut right now that if anything’s happened to him——”

“You are a friend of Sareef Ka-heel?” he breaks in, eyin’ me suspicious.

“Once removed,” says I; “but it amounts to the same thing. Now where is he?”

“For a friend—well, I know not,” says the old boy, kind of hesitatin’. Then, with another shrug, he makes up his mind. “So it shall be. Come. You shall see the Sareef.”

At that he beckons me to follow and starts towards the back. I went through one dark room, expectin’ to feel a knife in my ribs every minute, and then we goes through another. Next thing I knew we’re out in a little back yard, half full of empty cases and crates. In the middle of a clear space is a big brown tent, with the flap pinned back.

“Here,” says the old gent, “your friend, the Sareef Ka-heel!”

Say, for a minute I thought it was a trap he’s springin’ on me; but after I’d looked long enough I see who he’s pointin’ at. The party inside is squattin’ cross-legged on a rug, holdin’ the business end of one of these water bottle pipes in his mouth. He’s wearin’ some kind of a long bath robe, and most of his red hair is concealed by yards of white cloth twisted round 47 his head; but it’s Spotty all right, alive, uncarved, and lookin’ happy and contented.

“Well, for the love of soup!” says I. “What is it, a masquerade?”

“That you, McCabe?” says he. “Come in and—and sit on the floor.”

“Say,” says I, steppin’ inside, “this ain’t the costume you’re going to start for Canada in, is it?”

“Ah, forget Canada!” says he. “I’ve got that proposition beat a mile. Hey, Hazzam,” and he calls to the old pirate outside, “tell Mrs. Cahill to come down and be introduced!”

“What’s that?” says I. “You—you ain’t been gettin’ married, have you?”

“Yep,” says Spotty, grinnin’ foolish. “Nine o’clock last night. We’re goin’ to start on our weddin’ trip Tuesday, me and Mareena.”

“Mareena!” I gasps. “Not the—the one we saw out front? Where you going, Niagara?”

“Nah! Syria, wherever that is,” says he. “Mareena knows. We’re goin’ to live over there and buy rugs. That two hundred was just what we needed to set us up in business.”

“Think you’ll like it?” says I.

“Sure!” says he. “She says it’s fine. There’s deserts over there, and you travel for days and days, ridin’ on bloomin’ camels. Here’s the tent we’re goin’ to live in. I’m 48 practisin’ up. Gee! but this pipe is somethin’ fierce, though! Oh, here she is! Say, Mareena, this is Mr. McCabe, that I was tellin’ you about.”

Well, honest, I wouldn’t have known her for the same girl. She’s changed that Grand-st. uniform for a native outfit, and while it’s a little gaudy in color, hanged if it ain’t becomin’! For a desert bride I should say she had some class.

“Well,” says I, “so you and Spotty are goin’ to leave us, eh?”

“Ah, yes!” says she, them big black eyes of hers lightin’ up. “We go where the sky is high and blue and the sun is big and hot. We go back to the wide white desert where I was born. All day we shall ride toward the purple hills, and sleep at night under the still stars. He knows. I have told him.”

“That’s right,” says Spotty. “It’ll be all to the good, that. Mareena can cook too.”

To prove it, she makes coffee and hands it around in little brass cups. Also there’s cakes, and the old man comes in, smilin’ and rubbin’ his hands, and we has a real sociable time.

And these was the folks I’d suspected of wantin’ to carve up Spotty! Why, by the looks I saw thrown at him by them two, I knew they thought him the finest thing that ever happened. Just by the way Mareena reached out 49 sly to pat his hair when she passed, you could see how it was.

So I wished ’em luck and hurried back to report before Pinckney sent a squad of reserves after me.

“Well!” says he, the minute I gets in. “Let me know the worst at once.”

“I will,” says I. “He’s married.” It was all I could do, too, to make him believe the yarn.

“By Jove!” says he. “Think of a chap like Spotty Cahill tumbling into a romance like that! And on Fourth-ave!”

“It ain’t so well advertised as some other lanes in this town,” says I; “but it’s a great street. Say, what puzzled me most about the whole business, though, was the new name they had for Spotty. Sareef! What in blazes does that mean?”

“Probably a title of some sort,” says Pinckney. “Like sheik, I suppose.”

“But what does a Sareef have to do?” says I.

“Do!” says Pinckney. “Why, he’s boss of the caravan. He—he sits around in the sun and looks picturesque.”

“Then that settles it,” says I. “Spotty’s qualified. I never thought there was any place where he’d fit in; but, if your description’s correct, he’s found the job he was born for.”

Ever go on a grandmother hunt through the Red Ink District? Well, it ain’t a reg’lar amusement of mine, but it has its good points. Maybe I wouldn’t have tackled it at all if I hadn’t begun by lettin’ myself get int’rested in Vincent’s domestic affairs.

Now what I knew about this Vincent chap before we starts out on the grandmother trail wouldn’t take long to tell. He wa’n’t any special friend of mine. For one thing, he wears his hair cut plush. Course, it’s his hair, and if he wants to train it to stand up on top like a clothes brush or a blacking dauber, who am I that should curl the lip of scorn?

Just the same, I never could feel real chummy towards anyone that sported one of them self raisin’ crests. Vincent wa’n’t one of the chummy kind, though. He’s one of these stiff backed, black haired, brown eyed, quick motioned, sharp spoken ducks, that wants what he wants when he wants it. You know. He comes to the studio reg’lar, does his forty-five minutes’ 51 work, and gets out without swappin’ any more conversation than is strictly necessary.

All the information I had picked up about him was that he hailed from up the State somewhere, and that soon after he struck New York he married one of the Chetwood girls. And that takes more or less capital to start with. Guess Vincent had it; for I hear his old man left him quite a wad and that now he’s the main guy of a threshin’ machine trust, or something like that. Anyway, Vincent belongs in the four-cylinder plute class, and he’s beginnin’ to be heard of among the alimony aristocracy.

But this ain’t got anything to do with the way he happened to get confidential all so sudden. He’d been havin’ a kid pillow mix-up with Swifty Joe, just as lively as if the thermometer was down to thirty instead of up to ninety, and he’s just had his rub down and got into his featherweight serge, when in drifts this Rodney Kipp that’s figurin’ so strong on the defense side of them pipe line cases.

“Ah, Vincent!” says he.

“Hello, Rodney!” says Vincent as they passes each other in the front office, one goin’ out and the other comin’ in.

I’d never happened to see ’em meet before, and I’m some surprised that they’re so well acquainted. Don’t know why, either, unless it is that they’re so different. Rodney, you know, 52 is one of these light complected heavyweights, and a swell because he was born so. I was wonderin’ if Rodney was one of Vincent’s lawyers, or if they just belonged to the same clubs; when Mr. Kipp swings on his heel and says:

“Oh, by the way, Vincent, how is grammy?”

“Why!” says Vincent, “isn’t she out with you and Nellie?”

“No,” says Rodney, “she stayed with us only for a couple of days. Nellie said she hadn’t heard from her for nearly two months, and told me to ask you about her. So long. I’m due for some medicine ball work,” and with that he drifts into the gym. and shuts the door.

Vincent, he stands lookin’ after him with a kind of worried look on his face that was comical to see on such a cocksure chap as him.

“Lost somebody, have you?” says I.

“Why—er—I don’t know,” says Vincent, runnin’ his fingers through the bristles that waves above his noble brow. “It’s grandmother. I can’t imagine where she can be.”

“You must have grandmothers to burn,” says I, “if they’re so plenty with you that you can mislay one now and then without missin’ her.”

“Eh?” says he. “No, no! She is really my mother, you know. I’ve got into the way 53 of calling her grammy only during the last three or four years.”

“Oh, I see!” says I. “The grandmother habit is something she’s contracted comparative recent, eh? Ain’t gone to her head, has it?”

Vincent couldn’t say; but by the time he’s quit tryin’ to explain what has happened I’ve got the whole story. First off he points out that Rodney Kipp, havin’ married his sister Nellie, is his brother-in-law, and, as they both have a couple of youngsters, it makes Vincent’s mother a grammy in both families.

“Sure,” says I. “I know how that works out. She stays part of the time with you, and makes herself mighty popular with your kids; then she takes her trunk over to Rodney’s and goes through the same performance there. And when she goes visitin’ other places there’s a great howl all round. That’s it, ain’t it?”

It wa’n’t, not within a mile, and I’d showed up my low, common breedin’ by suggesting such a thing. As gently as he could without hurtin’ my feelin’s too much, Vincent explains that while my programme might be strictly camel’s foot for ordinary people, the domestic arrangements of the upper classes was run on different lines. For instance, his little Algernon Chetwood could speak nothing but French, that bein’ the brand of governess he’d always had, 54 and so he naturally couldn’t be very thick with a grandmother that didn’t understand a word of his lingo.

“Besides,” says Vincent, “mother and my wife, I regret to say, have never found each other very congenial.”

I might have guessed it if I’d stopped to think of how an old lady from the country would hitch with one of them high flyin’ Chetwood girls.

“Then she hangs out with your sister, eh, and does her grandmother act there?” says I.

“Well, hardly,” says Vincent, colorin’ up a little. “You see, Rodney has never been very intimate with the rest of our family. He’s a Kipp, and—— Well, you can’t blame him; for mother is rather old-fashioned. Of course, she’s good and kind-hearted and all that; but—but there isn’t much style about her.”

“Still sticks to the polonaise of ’81, and wears a straw lid she bought durin’ the Centennial, eh?” says I.

Vincent says that about tells the story.

“And where is it she’s been livin’ all this time that you’ve been gettin’ on so well in New York?” says I.

“In our old home, Tonawanda,” says he, shudderin’ some as he lets go of the name. “It’s where she should have stayed, too!”

“So-o-o-o?” says I. I’d been listenin’ just 55 out of politeness up to that point; but from then on I got int’rested, and I don’t let up until I’ve pumped out of him all the details about just how much of a nuisance an old, back number mother could be to a couple of ambitious young folks that had grown up and married into the swell mob.

It was a case that ought to be held up as a warnin’ to lots of superfluous old mothers that ain’t got any better taste than to keep on livin’ long after there’s any use for ’em. Mother Vincent hadn’t made much trouble at first, for she’d had an old maid sister to take care of; but when a bad case of the grip got Aunt Sophrony durin’ the previous winter, mother was left sort of floatin’ around.

She tried visitin’ back and forth between Vincent and Nellie just one consecutive trip, and the experiment was such a frost that it caused ructions in both families. In her Tonawanda regalia mother wa’n’t an exhibit that any English butler could be expected to pass the soup to and still keep a straight face.

So Vincent thinks it’s time to anchor her permanent somewhere. Accordin’ to his notion, he did the handsome thing too. He buys her a nice little farm about a mile outside of Tonawanda, a place with a fine view of the railroad tracks on the west and a row of brick yards to the east, and he lands mother there with a 56 toothless old German housekeeper for company. He tells her he’s settled a good comfortable income on her for life, and leaves her to enjoy herself.

But look at the ingratitude a parent can work up! She ain’t been there more’n a couple of months before she begins complainin’ about bein’ lonesome. She don’t see much of the Tonawanda folks now, the housekeeper ain’t very sociable, the smoke from the brick yards yellows her Monday wash, and the people she sees goin’ by in the cars is all strangers. Couldn’t Vincent swap the farm for one near New York? She liked the looks of the place when she was there, and wouldn’t mind being closer.

“Of course,” says he, “that was out of the question!”

“Oh, sure!” says I. “How absurd! But what’s the contents of this late bulletin about her being a stray?”

It was nothing more or less than that the old girl had sold up the farm a couple of months back, fired the housekeeper, and quietly skipped for New York. Vincent had looked for her to show up at his house, and when she didn’t he figured she must have gone to Nellie’s. It was only when Rodney Kipp fires the grammy question at him that he sees he’s made a wrong calculation and begins havin’ cold feet. 57

“If she’s here, alone in New York, there’s no knowing what may be happening to her,” says he. “Why, she knows nothing about the city, nothing at all! She might get run over, or fall in with disreputable people, or——” The other pictures was so horrible he passes ’em up.

“Mothers must be a great care,” says I. “I ain’t had one for so long I can’t say on my own hook; but I judge that you and sister has had a hard time of it with yours. Excuse me, though, if I don’t shed any tears of sympathy, Vincent.”

He looks at me kind of sharp at that; but he’s too busy with disturbin’ thoughts to ask what I mean. Maybe he’d found out if he had. It’s just as well he didn’t; for I was some curious to see what would be his next move. From his talk it’s plain Vincent is most worried about the chances of the old lady’s doin’ something that would get her name into the papers, and he says right off that he won’t rest easy until he’s found her and shooed her back to the fields.

“But where am I to look first?” says he. “How am I to begin?”

“It’s a big town to haul a dragnet through, that’s a fact,” says I. “Why don’t you call in Brother-in-Law Rodney, for a starter?”

“No, no,” says Vincent, glancin’ uneasy at 58 the gym. door. “I don’t care to have him know anything about it.”

“Maybe sister might have some information,” says I. “There’s the ’phone.”

“Thanks,” says he. “If you don’t mind, I will call her up at the Kipp country place.”

He does; but Nellie ain’t heard a word from mother; thought she must be with Vincent all this time; and has been too busy givin’ house parties to find out.

“Have her cross examine the maids,” says I. “The old lady may have left some orders about forwardin’ her mail.”

That was the clew. Inside of ten minutes Nellie ’phones back and gives a number on West 21st-st.

“Gee!” says I. “A hamfatters’ boardin’-house, I’ll bet a bag of beans! Grandmother has sure picked out a lively lodgin’-place.”

“Horrible!” says Vincent. “I must get her away from there at once. But I wish there was someone who——Shorty, could I get you to go along with me and——”

“Rescuin’ grandmothers ain’t my long suit,” says I; “but I’ll admit I’m some int’rested in this case. Come on.”

By the time our clockwork cab fetches up in front of the prunery it’s after six o’clock. There’s no mistakin’ the sort of histrionic asylum it was, either. A hungry lookin’ bunch of 59 actorets was lined up on the front steps, everyone of ’em with an ear stretched out for the dinner bell. In the window of the first floor front was a beauty doctor’s sign, a bull fiddle-artist was sawin’ out his soul distress in the hall bedroom above, and up under the cornice the Chicini sisters was leanin’ on the ledge and wishin’ the folks back in Saginaw would send on that grubstake letter before the landlady got any worse. But maybe you’ve seen samples of real dogday tragedy among the profesh, when the summer snaps have busted and the fall rehearsals have just begun. What, Mabel?

“It’s a sure enough double-in-brass roost,” says I. “Don’t say anything that sounds like contract, or you’ll be mobbed.”

But they sizes Vincent up for a real estate broker, and gives him the chilly stare, until he mentions the old lady’s name. Then they thaws out sudden.

“Oh, the Duchess!” squeals a couple in chorus. “Why, she always dines out, you know. You’ll find her around at Doughretti’s, on 27th-st.”

“Duchess!” says Vincent. “I—I’m afraid there’s some mistake.”

“Not at all,” says one of the crowd. “We all call her that. She’s got Little Spring Water with her to-night. Doughretti’s, just in from the avenue, is the place.” 60

And Vincent is the worst puzzled gent you ever saw as he climbs back into the cab.

“It can’t be mother they mean,” says he. “No one would ever think of calling her Duchess.”

“There’s no accountin’ for what them actorines would do,” says I. “Anyway, all you got to do is take a peek at the party, and if it’s a wrong steer we can go back and take a fresh start.”

You know Doughretti’s, if you don’t you know a dozen just like it. It’s one of these sixty-cent table dotty joints, with an electric name sign, a striped stoop awnin’, and a seven-course menu manifolded in pale purple ink. You begin the agony with an imitation soup that looks like Rockaway beach water when the tide’s comin’ in, and you end with a choice of petrified cheese rinds that might pass for souvenirs from the Palisades.

If you don’t want to taste what you eat, you let ’em hand you a free bottle of pure California claret, vatted on East Houston-st. It’s a mixture of filtered Croton, extra quality aniline dyes, and two kinds of wood alcohol, and after you’ve had a pint of it you don’t care whether the milk fed Philadelphia chicken was put in cold storage last winter, or back in the year of the big wind.

Madam Doughretti had just fed the Punk 61 Lady waltz into the pianola for the fourth time as we pulls up at the curb.

“It’s no use,” says Vincent. “She wouldn’t be here. I will wait, though, while you take a look around; if you will, Shorty.”

On the way over he’s given me a description of his missin’ parent; so I pikes up the steps, pushes past the garlic smells, and proceeds to inspect the groups around the little tables. What I’m lookin’ for is a squatty old party with gray hair pasted down over her ears, and a waist like a bag of hay tied in the middle. She’s supposed to be wearin’ a string bonnet about the size of a saucer, with a bunch of faded velvet violets on top, a coral brooch at her neck, and either a black alpaca or a lavender sprigged grenadine. Most likely, too, she’ll be doin’ the shovel act with her knife.

Well, there was a good many kinds of females scattered around the coffee stained tablecloths, but none that answers to these specifications. I was just gettin’ ready to call off the search, when I gets my eye on a couple over in one corner. The gent was one of these studio Indians, with his hair tucked inside his collar.

The old girl facin’ him didn’t have any Tonawanda look about her, though. She was what you might call a frosted pippin, a reg’lar dowager dazzler, like the pictures you see on fans. Her gray hair has been spliced out with 62 store puffs until it looks like a weddin’ cake; her hat is one of the new wash basin models, covered with pink roses that just matches the color of her cheeks; and her peek-a-poo lace dress fits her like it had been put onto her with a shoe horn.

Sure, I wa’n’t lookin’ for any such party as this; but I can’t help takin’ a second squint. I notices what fine, gentle old eyes she has, and while I was doin’ that I spots something else. Just under her chin is one of them antique coral pins. Course, it looked like a long shot, but I steps out to the door and motions Vincent to come in.

“I expect we’re way off the track,” says I; “but I’d like to have you take a careless glance at the giddy old party over under the kummel sign in the corner; the one facin’ this way—there.”

Vincent gives a jump at the first look. Then he starts for her full tilt, me trailin’ along and whisperin’ to him not to make any fool break unless he’s dead sure. But there’s no holdin’ him back. She’s so busy chattin’ with the reformed Sioux in store clothes that she don’t notice Vincent until he’s right alongside, and just as she looks up he lets loose his indignation.

“Why, grandmother!” says he.

She don’t seem so much jarred as you might 63 think. She don’t even drop the fork that she’s usin’ to twist up a gob of spaghetti on. All she does is to lift her eyebrows in a kind of annoyed way, and shoot a quick look at the copper tinted gent across the table.

“There, there, Vincent?” says she. “Please don’t grandmother me; at least, not in public.”

“But,” says he, “you know that you are a——”

“I admit nothing of the kind,” says she. “I may be your mother; but as for being anybody’s grandmother, that is an experience I know nothing about. Now please run along, Vincent, and don’t bother.”

That leaves Vincent up in the air for keeps. He don’t know what to make of this reception, or of the change that happened to her; but he feels he ought to register some sort of a kick.

“But, mother,” says he, “what does this mean? Such clothes! And such—such”—here he throws a meanin’ look at the Indian gent.

“Allow me,” says grandmother, breakin’ in real dignified, “to introduce Mr. John Little Bear, son of Chief Won-go-plunki. I am very sorry to interrupt our talk on art, John; but I suppose I must say a few words to Vincent. Would you mind taking your coffee on the back veranda?” 64

He was a well-trained red man, John was, and he understands the back out sign; so inside of a minute the crockery has been pushed away and I’m attendin’ a family reunion that appears to be cast on new lines. Vincent begins again by askin’ what it all means.

“It means, Vincent,” says she, “that I have caught up with the procession. I tried being the old-fashioned kind of grandmother, and I wasn’t a success. Now I’m learning the new way, and I like it first rate.”

“But your—your clothes!” gasps Vincent.

“Well, what of them?” says she. “You made fun of the ones I used to wear; but these, I would have you know, were selected for me by a committee of six chorus ladies who know what is what. I am quite satisfied with my clothes, Vincent.”

“Possibly they’re all right,” says he; “but how—how long have you been wearing your hair that way?”

“Ever since Madam Montrosini started on my improvement course,” says she. “I am told it is quite becoming. And have you noticed my new waist line, Vincent?”

Vincent hadn’t; but he did then, and he had nothin’ to say, for she has an hourglass lookin’ like a hitchin’ post. Not bein’ able to carry on the debate under them headings, he switches and comes out strong on what an awful thing 65 it was for her to be livin’ among such dreadful people.