SEVENTH ANNUAL

REPORT

OF THE

BUREAU OF ETHNOLOGY.

By J. W. Powell, Director.

INTRODUCTION.

The prosecution of ethnologic researches among the North American Indians, in accordance with act of Congress, was continued during the fiscal year 1885–’86.

The general plan upon which the work has been prosecuted in former years, and which has been explained in earlier reports, was continued in operation.

General lines of investigation were indicated by the Director, and the details intrusted to selected persons trained in their several pursuits, the results of whose labors are published from time to time in the manner provided for by law. A brief statement of the work upon which each of these special students was engaged during the year, with its condensed result, is presented below. This, however, does not specify in detail all of the studies undertaken or services rendered by them, as particular lines of research have been temporarily suspended in order to accomplish immediately objects regarded as of superior importance. From this cause the publication of several treatises and monographs has been delayed, although in some instances they have been heretofore reported as substantially completed, and, indeed, as partly in type.

The present opportunity is used to invite and urge again the assistance of explorers, writers, and students, who are not and XVI may not desire to be officially connected with this Bureau. Their contributions, whether in the shape of suggestion or of extended communications, will be gratefully acknowledged and carefully considered. If published in whole or in part, either in the series of reports or in monographs or bulletins, as the liberality of Congress may in future allow, the contributors will always receive proper credit.

The items which form the subject of the present report are presented in two principal divisions. The first relates to the work prosecuted in the field, and the second to the office work, which consists largely of the preparation for publication of the results of the field work, complemented and extended by study of the literature of the several subjects and by correspondence relating to them.

FIELD WORK.

This heading may be divided into, first, Mound Explorations; second, Explorations in Stone Villages; and, third, General Field Studies, among which those upon mythology, linguistics, and customs have been during the year the most prominent.

MOUND EXPLORATIONS.

WORK OF PROF. CYRUS THOMAS.

The work of the mound-exploring division, under the charge of Prof. Cyrus Thomas, was carried on during the fiscal year with the same success that had attended its earlier operations.

It is proper to explain that the title given above to the division does not fully indicate the extent of its work. The simple exploration of mounds is but a part of its scope, which embraces, as contemplated in its organization, a careful examination and study of the archeologic remains in the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. The limitation of the force engaged on this work renders it necessary that the investigations should be conducted along but one or two selected lines at a time.

Before and even during some portion of the year now XVII reported upon attention had been devoted almost exclusively to the exploration of individual mounds, with a view of ascertaining the different types of tumuli, as regards form, construction, and other particulars and the vestiges of art and human remains found in them. The study of these works in their relation to each other and their segregation into groups, and of the mural works, inclosures, and works of defense, is important in the attempt to obtain indications of the social life and customs of the builders. This plan of study had not received the attention desirable and involved the necessity of careful surveys. It was thought best to make a commencement this year in this branch of investigation.

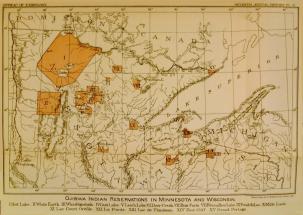

During the summer of 1885 Prof. Thomas was in Wisconsin, engaged in investigating and studying the effigy mounds and other ancient works of that section.

Messrs. James D. Middleton, John P. Rogan, and John W. Emmert were permanent assistants during the year; Mr. Charles M. Smith, Rev. S. D. Peet, and Mr. H. L. Reynolds were employed for short periods as temporary assistants.

During the summer and autumn of 1885 Messrs. Middleton and Emmert were at work on the mounds and ancient monuments of southwestern Wisconsin, the former surveying the groups of effigy mounds and the latter exploring the conical tumuli. When the weather became too cold for operations in that section they were transferred to east Tennessee, where Mr. Emmert continued at work throughout the remainder of the fiscal year.

When it had been decided to commence the preparation of a report on the field work of the division, in the hope of its early publication, Mr. Middleton was called to the office to assist in that preparation, where he remained, preparing maps and plats and making a catalogue of the collections, until the latter part of April, 1886, when he again entered upon field work in the southern part of Illinois, among the graves of that neighborhood.

Mr. Rogan was in charge of the office work from the 1st of July until the latter part of August, during which time Prof. Thomas was in the field, as before mentioned. He was engaged XVIII during the remainder of the year in exploring the mounds of northern Georgia and east Tennessee.

Rev. S. D. Peet was employed for a few months in preparing a preliminary map showing the localities of the antiquarian remains of Wisconsin and the areas formerly occupied by the several Indian tribes which are known to have inhabited that region. In addition he prepared for use in the report notes on the distribution and character of the mounds and other ancient works of Wisconsin.

Mr. Smith was engaged during the month of June, 1886, in exploring mounds and investigating the ancient works in southwestern Pennsylvania; and Mr. Reynolds, during the same time, in tracing and exploring the monumental remains of western New York.

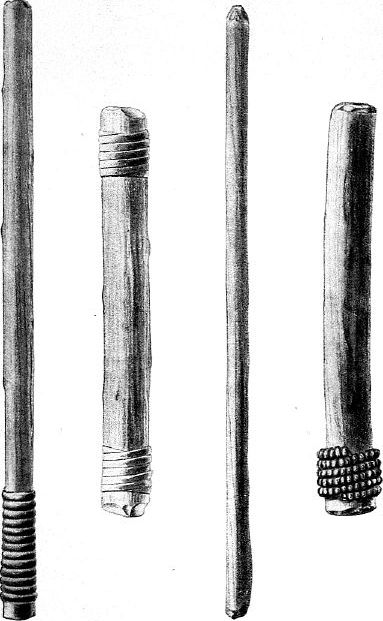

Notwithstanding the details necessary for office work in the preparation of maps and plats for the report, and cataloguing the collection, the amount of field work accomplished was equal to that done in previous years. Although, as before stated, one of the assistants, Mr. Middleton, was chiefly engaged, while in the field, in surveying, about 3,500 specimens were collected and a large number of drawings obtained illustrating the different modes of construction of the mounds.

EXPLORATIONS IN STONE VILLAGES.

WORK OF DIRECTOR J. W. POWELL.

During the summer of 1885 the Director, accompanied by Mr. James Stevenson, revisited portions of Arizona and New Mexico in which many structures are found which have greatly interested travelers and anthropologists, and about which various theories have grown. The results of the investigation have been so much more distinct and comprehensive than any before obtained that they require to be reported with some detail.

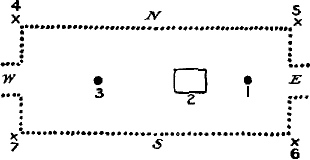

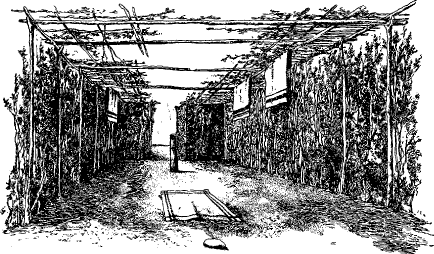

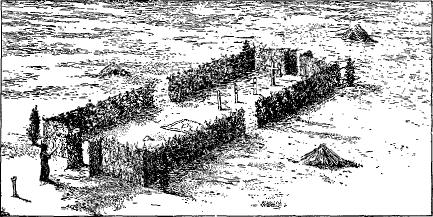

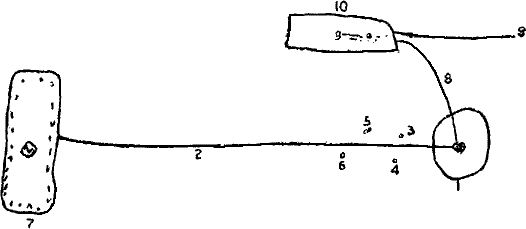

On the plain to the west of the Little Colorado River and north of the San Francisco Mountain there are many scattered ruins, usually having one, two, or three rooms each, all of which are built of basaltic cinders and blocks. Through the plain a valley runs to the north, and then east to the Little Colorado. XIX Down the midst of the valley there is a wash, through which, in seasons of great rainfall, a stream courses. Along this stream there are extensive ruins built of sandstone and limestone. At one place a village site was discovered, in which several hundred people once found shelter. To the north of this and about twenty-five miles from the summit of San Francisco Peak there is a volcanic cone of cinder and basalt. This small cone had been used as the site of a village, a pueblo having been built around the crater. The materials of construction were derived from a great sandstone quarry near by, and the pit from which they were taken was many feet in depth and extended over two or three acres of ground. The cone rises on the west in a precipitous cliff from the valley of an intermittent creek. The pueblo was built on that side at the summit of the cliff, and extending on the north and south sides along the summit of steep slopes, was inclosed on the east, so that the plaza was entered by a covered way. The court, or plaza, was about one-third of an acre in area. The little pueblo contained perhaps sixty or seventy rooms. Southward of San Francisco Mountain many other ruins were found.

East of the San Francisco Peak, at a distance of about twelve miles, another cinder cone was found. Here the cinders are soft and friable, and the cone is a prettily shaped dome. On the southern slope there are excavations into the indurated and coherent cinder mass, constituting chambers, often ten or twelve feet in diameter and six to ten feet in height. The chambers are of irregular shape, and occasionally a larger central chamber forms a kind of vestibule to several smaller ones gathered about it. The smaller chambers are sometimes at the same altitude as the central or principal one, and sometimes at a lower altitude. About one hundred and fifty of these chambers have been excavated. Most of them are now partly filled by the caving in of the walls and ceilings, but some of them are yet in a good state of preservation. In these chambers, and about them on the summit and sides of the cinder cone, many stone implements were found, especially metates. Some bone implements also were discovered. At the very summit of the little cone there is a plaza, inclosed by a rude wall made XX of volcanic cinders, the floor of which was carefully leveled. The plaza is about forty-five by seventy-five feet in area. Here the people lived in underground houses—chambers hewn from the friable volcanic cinders. Before them, to the south, west, and north, stretched beautiful valleys, beyond which volcanic cones are seen rising amid pine forests. The people probably cultivated patches of ground in the low valleys.

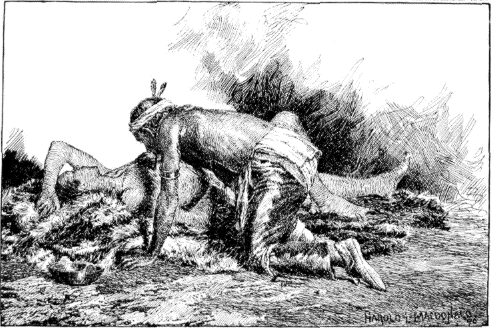

About eighteen miles still farther to the east of San Francisco Mountain another ruined village was discovered, built about the crater of a volcanic cone. This volcanic peak is of much greater magnitude. The crater opens to the eastward. On the south many stone dwellings have been built of the basaltic and cinder-like rocks. Between the ridge on the south and another on the northwest there is a low saddle in which other buildings have been erected, and in which a great plaza was found, much like the one previously described. But the most interesting part of this village was on the cliff which rose on the northwest side of the crater. In this cliff are many natural caves, and the caves themselves were utilized as dwellings by inclosing them in front with walls made of volcanic rocks and cinders. These cliff dwellings are placed tier above tier, in a very irregular way. In many cases natural caves were thus utilized; in other cases cavate chambers were made; that is, chambers have been excavated in the friable cinders. On the very summit of the ridge stone buildings were erected, so that this village was in part a cliff village, in part cavate, and in part the ordinary stone pueblo. The valley below, especially to the southward, was probably occupied by their gardens. In the chambers among the overhanging cliffs a great many interesting relics were found, of stone, bone, and wood, and many potsherds.

About eight miles southeast of Flagstaff, a little town on the southern slope of San Francisco Mountain, Oak Creek enters a canyon, which runs to the eastward and then southward for a distance of about ten miles. The gorge is a precipitous box canyon for the greater part of this distance. It is cut through carboniferous rocks—sandstones and limestones—which are here nearly horizontal. The softer sandstones rapidly disintegrate, XXI and the harder sandstones and limestones remain. Thus broad shelves are formed on the sides of the cliffs, and these shelves, or the deep recesses between them, were utilized, so that here is a village of cliff dwellings. There are several hundred rooms altogether. The rooms are of sandstone, pretty carefully worked and laid in mortar, and the interior of the rooms was plastered. The opening for the chimney was usually by the side of the entrance, and the ceilings of the rooms are still blackened with soot and smoke. Around this village, on the terrace of the canyon, great numbers of potsherds, stone implements, and implements of bone, horn, and wood were found; and here, as in all of the other ruins mentioned, corncobs in great abundance were discovered.

In addition to the four principal ruins thus described many others are found, most of them being of the ordinary pueblo type. From the evidence presented it would seem that they had all been occupied at a comparatively late date. They were certainly not abandoned more than three or four centuries ago.

Later in the season the Director visited the Supai Indians of Cataract Canyon, and was informed by them that their present home had been taken up not many generations ago, and that their ancestors occupied the ruins which have been described; and they gave such a circumstantial account of the occupation and of their expulsion by the Spaniards, that no doubt can be entertained of the truth of their traditions in this respect. The Indians of Cataract Canyon doubtless lived on the north, east, and south of San Francisco Mountain at the time this country was discovered by the Spaniards, and they subsequently left their cliff and cavate dwellings and moved into Cataract Canyon, where they now live. It is thus seen that these cliff and cavate dwellings are not of an ancient prehistoric time, but that they were occupied by a people still existing, who also built pueblos of the common type.

Later in the season the party visited the cavate ruins near Santa Clara, previously explored by Mr. Stevenson. Here, on the western side of the Rio Grande del Norte, was found a system of volcanic peaks, constituting what is known as the XXII Valley Range. To the east of these peaks, stretching far beyond the present channel of the Rio Grande, there was once a great Tertiary lake, which was gradually filled with the sands washed into it on every hand and by the ashes blown out of the adjacent volcanoes. This great lake formation is in some places a thousand feet in thickness. When the lake was filled the Rio Grande cut its channel through the midst to a depth of many hundreds of feet. The volcanic mountains to the westward send to the Rio Grande a number of minor streams, which in a general way are parallel with one another. The Rio Grande itself, and all of these lateral streams, have cut deep gorges and canyons, so that there are long, irregular table-lands, or mesas, extending from the Rio Grande back to the Valley Mountains, each mesa being severed from the adjacent one by a canyon or canyon valley; and each of these long mesas rises with a precipitous cliff from the valley below. The cliffs themselves are built of volcanic sands and ashes, and many of the strata are exceedingly light and friable. The specific gravity of some of these rocks is so low that they will float on water. Into the faces of these cliffs, in the friable and easily worked rock, many chambers have been excavated; for mile after mile the cliffs are studded with them, so that altogether there are many thousands. Sometimes a chamber or series of chambers is entered from a terrace, but usually they were excavated many feet above any landing or terrace below, so that they could be reached only by ladders. In other places artificial terraces were built by constructing retaining walls and filling the interior next to the cliff with loose rock and sand. Very often steps were cut into the face of a cliff and a rude stairway formed by which chambers could be reached. The chambers were very irregularly arranged and very irregular in size and structure. In many cases there is a central chamber, which seems to have been a general living room for the people, back of which two, three, or more chambers somewhat smaller are found. The chambers occupied by one family are sometimes connected with those occupied by another family, so that two or three or four sets of chambers have interior communication. Usually, however, the communication from one system of XXIII chambers to another was by the outside. Many of the chambers had evidently been occupied as dwellings. They still contained fireplaces and evidences of fire; there were little caverns or shelves in which various vessels were placed, and many evidences of the handicraft of the people were left in stone, bone, horn, and wood, and in the chambers and about the sides of the cliffs potsherds are abundant. On more careful survey it was found that many chambers had been used as stables for asses, goats, and sheep. Sometimes they had been filled a few inches, or even two or three feet, with the excrement of these animals. Ears of corn and corncobs were also found in many places. Some of the chambers were evidently constructed to be used as storehouses or caches for grain. Altogether it is very evident that the cliff houses have been used in comparatively modern times; at any rate since the people owned asses, goats, and sheep. The rock is of such a friable nature that it will not stand atmospheric degradation very long, and there is abundant evidence of this character testifying to the recent occupancy of these cavate dwellings.

Above the cliffs, on the mesas, which have already been described, evidences of more ancient ruins were found. These were pueblos built of cut stone rudely dressed. Every mesa had at least one ancient pueblo upon it, evidently far more ancient than the cavate dwellings found in the face of the cliffs. It is, then, very plain that the cavate dwellings are not of great age; that they have been occupied since the advent of the white man, and that on the summit of the cliffs there are ruins of more ancient pueblos.

Now, the pottery of Santa Clara had been previously studied by Mr. Stevenson, who made a large collection there two or three years ago, and it was at once noticed that the potsherds of these cliff dwellings are, both in shape and material, like those now made by the Santa Clara Indians. The peculiar pottery of Santa Clara is readily distinguished, as may be seen by examining the collection now in the National Museum. While encamped in the valley below, the party met a Santa Clara Indian and engaged him in conversation. From him the history of the cliff dwellings was soon obtained. His statement was that originally his people lived in six pueblos, built of cut stone, XXIV upon the summit of the mesas; that there came a time when they were at war with the Apaches and Navajos, when they abandoned their stone pueblos above and for greater protection excavated the chambers in the cliffs below; that when this war ended part of them returned to the pueblos above, which were rebuilt; that there afterward came another war, with the Comanche Indians, and they once more resorted to cliff dwellings. At the close of this war they built a pueblo in the valley of the Rio Grande, but at the time of the invasion of the Spaniards their people refused to be baptized, and a Spanish army was sent against them, when they abandoned the valley below and once more inhabited the cliff dwellings above. Here they lived many years, until at last a wise and good priest brought them peace, and persuaded them to build the pueblo which they now occupy—the village of Santa Clara. The ruin of the pueblo which they occupied previous to the invasion of the Spaniards is still to be seen about a mile distant from the present pueblo.

The history thus briefly given was repeated by the governor and by other persons, all substantially to the same effect. It is therefore evident that the cavate dwellings of the Santa Clara region belong to a people still extant; that they are not of great antiquity, and do not give evidence of a prehistoric and now extinct race.

Plans and measurements were made of some of the villages with sufficient accuracy to prepare models. Photographic views and sketches were also procured with which to illustrate a detailed report of the subject to be published by the Bureau.

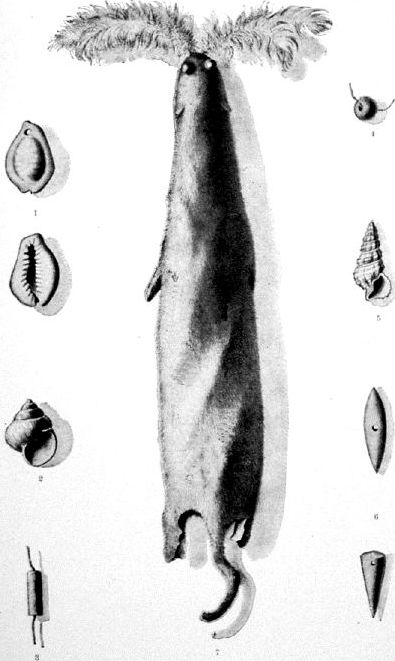

WORK OF MR. JAMES STEVENSON.

After the investigations made in company with the Director, as mentioned above, Mr. Stevenson proceeded with a party to the ancient province of Tusayan, in Arizona, to study the characteristics of the Moki tribes, its inhabitants, and to make collections of such implements and utensils as illustrate their arts and industries. Several months were spent among the villages, resulting in a large collection of rare objects, all of which were selected with special reference to their anthropologic XXV importance. This collection contains many articles novel in character and with uses differing from any heretofore obtained, and forms an important addition to the collections in the National Museum.

A study of their religious ceremonials and mythology was made, of which full notes were taken. Sketches were made of their masks and other objects which could not be obtained for the collection.

Mrs. Stevenson was also enabled to obtain a minute description of the celebrated dance, or medicine ceremony, of the Navajos, called the Yéibit-cai. She made complete sketches of the sand altars, masks, and other objects employed in this ceremonial.

WORK OF MESSRS. VICTOR MINDELEFF AND COSMOS MINDELEFF.

Mr. Victor Mindeleff, who had been engaged for several years in investigating the architecture of the pueblos and the ruins of the southwest, was at the beginning of the fiscal year at work among the Moki towns in Arizona, in charge of a party. Mr. Cosmos Mindeleff left Washington on July 6 for the same locality. He was placed in charge of the surveying necessary in the Stone Village region, and the result of his work is included in the general report of that division.

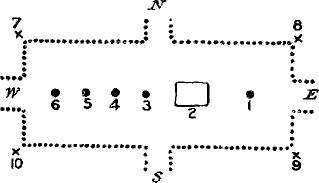

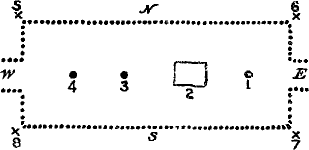

Visits were paid to the Moki villages in succession, obtaining drawings of some constructional details, and also traditions bearing on the ruins in that vicinity. The main camp was established near Mashongnavi, one of the Moki villages. A large ruined pueblo, formerly occupied by the Mashongnavi, was here surveyed. No standing walls are found at the present time, and many portions of the plan are entirely obliterated. Typical fragments of pottery were collected.

Following this work, four other ruined pueblos were surveyed, and such portions of them as clearly indicated dividing walls were drawn on the ground plans.

Many of the ruins in this vicinity, according to the traditions of the Mokis, have been occupied in comparatively recent times—-a number of them having been abandoned since the Spanish conquest of the country. In several cases the villages XXVI now occupied are not upon the same sites as those first visited by the Spaniards, although retaining the same names.

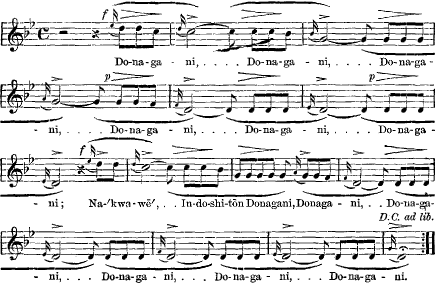

While the work of surveying was in progress, in charge of Mr. Cosmos Mindeleff, Mr. Victor Mindeleff made a visit of several days at Keam Canyon, there to meet a number of the Navajo Indians to explain the purpose of the work and allay the suspicions of these Indians, a necessary precaution, as some of the proposed work was laid out in Canyon de Chelly, in the heart of their reservation. Recent restrictions to which they had been subjected, as a consequence of new surveys of the reservation line, had made them especially distrustful of parties equipped with instruments for surveying. Incidental to explanations of the purpose of the work, an opportunity was afforded of obtaining a number of mythologic notes, and also interesting data regarding the construction of their “hogans,” with the rules prescribing the arrangement of each part of the frame and other particulars. A number of ceremonial songs are sung at the building of these houses, but of these only one could be secured, which was obtained in the original and translated. Whenever opportunity occurred, during the progress of the work, photographs and diagrams of construction of “hogans” were procured.

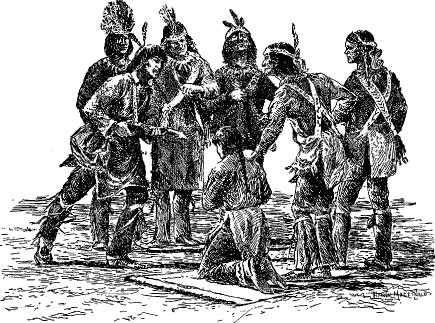

On August 17 the ceremony of the snake-dance took place at Mashongnavi, similar in every detail to that performed at Walpi, and differing only in the number of participants. Several instantaneous negatives of the various phases of the dance were secured. On the following day the same ceremony was performed on a larger scale at Walpi, the easternmost of the Moki villages.

Mr. Cosmos Mindeleff assisted in collecting from the present inhabitants of the region legendary information bearing upon ruins and in observing the snake-dances, a description of which was prepared for publication.

While the surveys of the ruins were in progress many detailed studies were made of special features in the modern villages, particularly among the “kivas” or religious chambers. In several instances the large roofing timbers of the “kiva” were found to be the old beams from the Spanish churches, XXVII hewn square, and decorated with the characteristic rude carving of the old Spanish work. A number of legends connected with the ruined pueblos were recorded.

On closing this work in the vicinity of the Moki villages, late in August, the party moved into Keam Canyon, en route for Canyon de Chelly. A day was devoted to the survey of a small pueblo of irregular elliptical outline, situated about eighteen miles northeast from Keam Canyon. This ruin is in excellent state of preservation and exhibits in the masonry some stones of remarkably large size. The early part of September was employed in making a close survey of the Mummy Cave group of ruins in Canyon de la Muerte, this work including a five-foot contour map of the ground and the rocky ledge over which the houses were distributed. Detailed drawings of a number of special features were made here, particularly in connection with the circular ceremonial chambers. The latter were so buried under the accumulated debris of fallen walls that much excavation was required to lay bare the details of internal arrangement. A high class of workmanship is here exhibited, both in the execution of the constructional features and in the interior decoration of these chambers. Later the White House group, in the Canyon de Chelly, comprising a village and cliff houses, was examined and platted in the same manner.

The drawings and plans were supplemented with a series of photographs. Some negatives of Navajo houses were also made.

On closing this work the party went into Fort Defiance, en route for Zuñi, and thence to Ojo Caliente, a modern farming pueblo of the Zuñi, about twelve miles south of the principal village. Here two ruins of villages, thought to belong to the ancient Cibola group, were platted. One of these villages had been provided with a circular reservoir of large size, partially walled in with masonry. Here, also, the well preserved walls of a stone church can be seen. The other contains the remains of a large church, built of adobe. A series of widely scattered house-clusters, occurring two miles west of Ojo Caliente, was also examined, but the earth had drifted over the fallen walls XXVIII and so covered them that the arrangement of rooms could scarcely be traced at all.

The modern village of Ojo Caliente was also surveyed and diagrams and photographs made.

Towards the end of September camp was moved to the vicinity of Zuñi. Here four other villages of the Cibola group and the old villages on the mesa of Ta-ai-ya-lo-ne were examined. Camp was then moved to Nutria, a farming pueblo of Zuñi. From this camp Nutria was surveyed and photographed, and also the village of Pescado, which is occupied only during the farming season. Both of these modern farming pueblos appear to be built on the ruins of more ancient villages, the remains of which were especially noticeable in the case of Pescado, where the very carefully executed masonry, characteristic of the ancient methods of construction, could be seen outcropping at many points.

WORK OF MR. E. W. NELSON.

Following the return of the main party to Washington, some preliminary exploration was carried on by Mr. E. W. Nelson, who made an examination of the headwaters of the South Fork of Salt River, but did not find any ruins. Thence the Blue Ridge was crossed, and the valley of the Blue Fork of the San Francisco River visited. Here ruins were frequently increasing in number toward the south. Farther south three sets of cliff ruins were also located.

GENERAL FIELD STUDIES.

WORK OF DR. H. C. YARROW.

During the summer and fall of 1885, Dr. H. C. Yarrow, acting assistant surgeon U.S. Army, examined points in Arizona and Utah. In the vicinity of Springerville, Apache County, Arizona, in company with Mr. E. W. Nelson, he visited a number of ancient pueblos and discovered that the people formerly occupying the towns had followed the custom of burying their dead immediately outside the walls of their habitations, marking the places of sepulcher with circles of stones. XXIX The graves were four or five feet in depth, and various household utensils had been deposited with the dead. Mr. Nelson, who had made a careful search for these cemeteries, informed him of the locality of hundreds. Unfortunately for anthropometric science, most of the bones are too much decayed to be of practical value. The places of burial selected at these pueblos are similar to the burial places discovered in 1874 near the large ruined pueblo of Abiquiu, in the valley of the Chama, New Mexico.

Dr. Yarrow also visited the Moki pueblos in Arizona, and obtained from one of the principal men a clear and succinct account of their burial customs. While there he witnessed the famous snake dance, which occurs every two years, and is supposed to have the effect of producing rain. From his knowledge of the reptilian fauna of the country he was able to identify the species of serpents used in the dance, and from personal examination satisfied himself that the fangs had not been extracted from the poisonous varieties. He thinks, however, that the reptiles are somewhat tamed by handling during the four days that they are kept in the estufas and possibly are made to eject the greater part of the venom contained in the sacs at the roots of the teeth, by being teased and forced to strike at different objects held near them. He does not think that a vegetable decoction in which they are washed has a stupefying effect, as has been supposed by some. He also obtained from a Moki high priest a full account of the ceremonies attending the dance. Through the assistance of Mr. Thomas V. Keam, of Keam Canyon, Arizona, and Mr. A. M. Stephen, he was able to procure from a noted Navajo wise man an exact account of the burial customs of his people, as well as valuable information regarding their medical practices, especially such as relate to obstetrics.

From Arizona Dr. Yarrow proceeded to Utah, and made an examination of an old rock cemetery near Farmington, finding it similar to the one he discovered in 1872 near the town of Fillmore. The bodies had been carried far up the side of the mountain; cavities had been prepared in a rock slide, and the bodies placed therein. Branches of cottonwood were then laid XXX over and large boulders piled on top. In several of these graves the skeletons were in a fair state of preservation, and were removed, as well as the articles found with them.

Through the kindness of Mr. William Young, of Grantsville, a skeleton of a Gosiute, in excellent preservation, was obtained, and has been presented to the Army Medical Museum. It may be stated that the examination of the rock cemetery at Farmington showed that the inhabitants of the eastern slope of the Wahsatch Range, in Great Salt Lake Valley, followed the mode of rock sepulture from this, the most northern point visited, to below Parowan, a distance of at least two hundred miles southward, and it seems that these people occupied the valley long subsequent to those living near the water courses who constructed the small mounds on top of which were the rude adobe dwellings, and in some instances used these huts for burial purposes.

WORK OF MR. J. C. PILLING.

In the spring of 1886 Mr. James C. Pilling made a trip to Europe in the interest of his work on the Bibliography of the Languages of the North American Indians, and spent many days in the library of the British Museum, the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris, and several extensive private libraries in England and France. The results of this trip are highly satisfactory and valuable.

WORK OF MR. JEREMIAH CURTIN.

Mr. Jeremiah Curtin continued to collect vocabularies and myths in California. The whole number of myths obtained in California and Oregon was over three hundred. The number of vocabularies was eight, being the Yana, Atsugëi (Hat Creek), Wasco, Miléblama (Warm Springs), Pai Ute, Shasta, Maidu, and Wintu. Texts were also obtained in Yana, Wasco, Warm Spring, and Shasta.

OFFICE WORK.

Prof. Cyrus Thomas was engaged during the year, except the few weeks he was in the field, in the preparation of his general report and in correspondence relating to the archeology XXXI of the district before specified. He also finished a paper published in the Sixth Annual Report of this Bureau under the title, “Aids to the study of the Maya Codices,” and a special report on the “Burial mounds of the northern sections of the United States.” The latter has appeared in the Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau.

Mrs. V. L. Thomas, in addition to her duties as clerk, has been employed in preparing a catalogue of the ancient works in that part of the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. This catalogue, now nearly complete, is intended to give the localities and character of all the antiquities in the region mentioned, including discoveries which have been noted in publications, as well as those mentioned in the reports of work done under the Bureau.

Mr. James C. Pilling continued to give a large share of his time and attention throughout the year to the “Bibliography of the languages of the North American Indians,” which has been adverted to in previous reports. The advance “proofsheets” of this work, printed in the last fiscal year, were distributed to collaborators and have been the means of obtaining the active cooperation of many persons throughout this and other countries who are interested in linguistic and bibliographic science. They have thus elicited a large number of additions, corrections, suggestions, and criticisms, all of which have received careful consideration.

Mr. Frank H. Cushing was engaged in the preparation, from the large amount of Zuñi material collected by him during several years, of papers upon the language, mythology, and institutions of that people.

Mrs. Erminnie A. Smith continued her study of the Iroquoian languages. The first part of her final contribution on the subject was intended to be a Tuscarora grammar and dictionary. The first portion of the dictionary was completed, and had been forwarded to the Bureau when her sudden and lamented death occurred on June 9, 1886, at her home in Jersey City. Her former assistant, Mr. J. N. B. Hewitt, of Tuscarora descent, has been engaged to complete the work she so successfully began, and it is expected that the results of her long labors in the field will be published without delay.

XXXIIMr. Charles C. Royce resigned his connection with the Bureau in the early part of the year, thereby delaying the completion of the work upon the primal title of the Indian tribes to lands within the United States and the methods of procuring their relinquishment, the scope and value of which have before been explained. Mr. Royce, before his departure from Washington, completed a paper on the “Cherokee Nation of Indians,” which has appeared in the Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau.

Dr. H. C. Yarrow was still engaged in preparing the material for the final volume upon the mortuary customs of the North American Indians, in the prosecution of which the large amount of information received and obtained from various sources has been carefully classified and arranged under proper divisions, so that the manuscript is now being rapidly put into shape for publication.

Dr. Washington Matthews, U.S. Army, continued to prepare for publication the copious notes obtained by him during former years in the Navajo country, his chief work being upon a grammar and dictionary of the Navajo language. He also wrote several papers, one of which, a “Chant upon the Mountains,” has been published in the Fifth Annual Report.

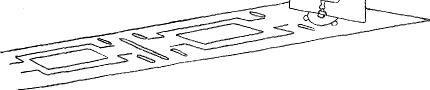

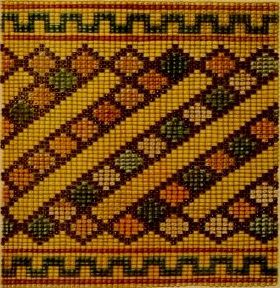

Mr. W. H. Holmes continued his work in the office during the year, superintending the illustration of the various publications of the Bureau. His scientific studies have been confined principally to the field of American archeologic art. Two fully illustrated papers have been finished and have appeared in the Sixth Annual Report of the Bureau. They are upon “Ancient art of the province of Chiriqui, Colombia,” and “A study of the textile art in its relations to the development of form and ornament.” Mr. Holmes has, in addition, continued his duties as curator of aboriginal pottery in the National Museum.

Mr. Victor Mindeleff, when not in the field, prepared reports on the Tusayan and Cibola architectural groups. These, when completed, are to be fully illustrated by a series of plans and drawings now being prepared from the field-notes and other material. In this work it is proposed to discuss the architecture XXXIII in detail, particularly in the case of the modern pueblos, where many of the constructional devices of the old builders still survive. The examination of these details will be found to throw light on obscure features of many ruined pueblos whose state of preservation is such as to exhibit but little detail in themselves.

In connection with the classification and arrangement of new material from Canyon de Chelly, a paper was prepared on the cliff ruins of that region.

Mr. Cosmos Mindeleff has been in charge of the modeling room during the last year. Upon his return from the field a series of models to illustrate the Chaco ruins, architecturally the most important in the Southwest, was commenced. Two of these, viz, the ruin of Wejegi and that of a small pueblo near Pueblo Alto, have been finished and duplicates have been deposited in the National Museum. The third, a large model of Peñasco Blanco, is still uncompleted. All of these models are made from entirely new surveys made in the summer of 1884. The scale used in the previous series—the inhabited pueblos and the cliff ruins—though larger than usually adopted for this class of work, has shown so much more detail and has proved generally so satisfactory, that it has been continued in the Chaco Ruin group, bringing the entire series of models made by the Bureau to a uniform scale of 1:60, or one inch to five feet. In addition to this the work of duplicating the existing models of the Bureau for purposes of exchange was commenced. Three of these have been completed, and two others are about half finished.

Mr. E. W. Nelson was engaged upon a report of his investigations among the Eskimo tribes of Alaska. A part of this report, consisting of an English-Eskimo dictionary, he has already forwarded.

As hereinafter explained, the year was principally devoted to the synonymy of the Indian tribes, the special studies of several officers of the Bureau being suspended so that their whole time might be employed in that direction. In the year XXXIV 1885, however, and at subsequent intervals, their work was as follows:

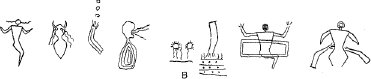

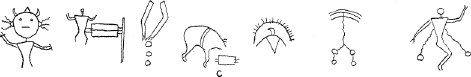

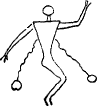

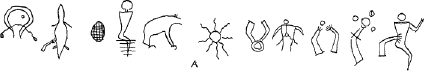

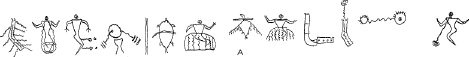

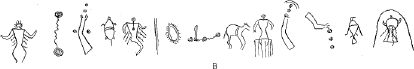

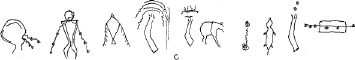

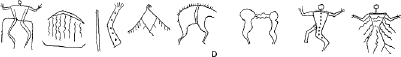

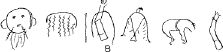

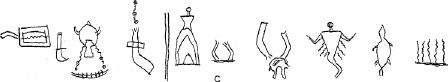

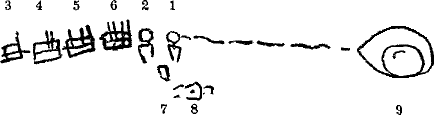

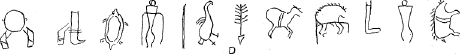

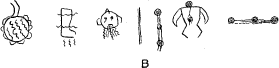

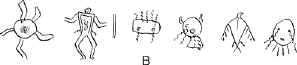

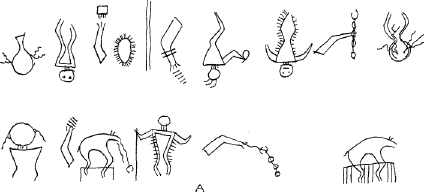

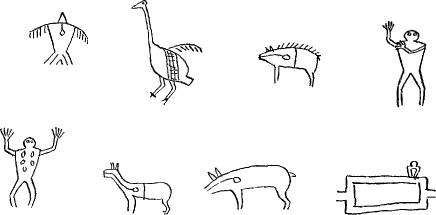

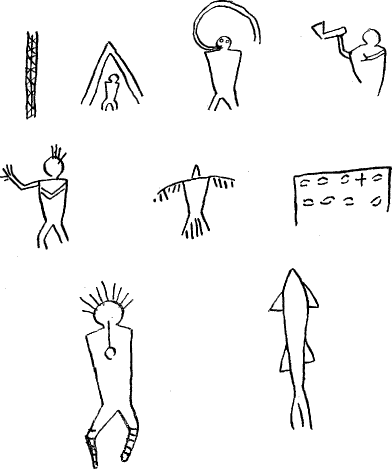

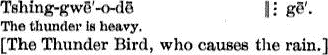

Col. Garrick Mallery, U.S. Army, continued the study, by researches and correspondence, of sign language and pictography. A comprehensive, though preliminary, paper on the latter subject has been printed, with copious illustrations, in the Fourth Annual Report.

Mr. H. W. Henshaw was engaged during the year in work upon the synonymy of Indian tribes, as specified below.

Mr. Albert S. Gatschet continued to revise and perfect his grammar and dictionary of the Klamath language, a large part of which work is in print. He also took down vocabularies from Indian delegates present in this city on tribal business, and thus succeeded in incorporating into the collections of the Bureau of Ethnology linguistic material from the Alibamu, Hitchiti, Muskoki, and Seneca languages.

Rev. J. Owen Dorsey pursued his work on the Ȼegiha language. Having the aid of a Winnebago Indian for some time he enlarged his vocabulary of that language and recorded grammatical notes. He also reported upon works submitted to his examination upon the Tuscarora, Micmac, and Cherokee languages.

Mr. James Mooney, who had been officially connected with the Bureau since the early part of the fiscal year, was also engaged upon linguistic work.

SYNONYMY OF INDIAN TRIBES.

The Director has before reported in general terms that the most serious source of perplexity to the student of the history of the North American Indians is the confusion existing among their tribal names. The causes of this confusion are various. The Indian names for themselves have been understood and recorded in diverse ways by the earlier authors, and have been variously transmitted by the latter. Nicknames arising from trivial causes, and often without apparent cause, have been imposed upon many tribes. Names borne by one tribe at some period of its history have been transferred to another, or to several other distinct tribes. Typographical errors, and improved XXXV spelling on assumed phonetic grounds, have swelled the number of synonyms until the investigator of a special tribe often finds himself in a maze of nomenclatural perplexity.

It has long been the intention of the Director to prepare a work on tribal names, which so far as possible should refer their confusing titles to a correct and systematic standard. Delay has been occasioned chiefly by the fundamental necessity of defining linguistic stocks or families into which all tribes must be primarily divided; and to accomplish this, long journeys and laborious field and office investigations have been required during the whole time since the establishment of the Bureau. Though a few points still remained in an unsatisfactory condition, it was considered that a sufficient degree of accuracy had been attained to allow of the publication for the benefit of students of a volume devoted to the subject. The preparation of the plan of such a volume was intrusted to Mr. H. W. Henshaw, late in the spring of 1885, and in June of that year the work was energetically begun in accordance with the plans submitted. The preparation of this work, which to a great extent underlies and is the foundation for every field of ethnologic investigation among Indians, was considered of such prime importance that nearly all the available force of the Bureau was placed upon it, to the suspension of the particular investigations in which the several officers had been engaged.

In addition to the general charge of the whole work, Mr. Henshaw gave special attention to the families of the northwest coast from Oregon northward, including the Eskimo, and also several in California. To Mr. Albert S. Gatschet the tribes of the southeastern United States, together with the Pueblo and Yuman tribes, were assigned. The Algonkian family in all its branches—by far the most important part of the whole, so far as the great bulk of literature relating to it is concerned—was intrusted to Col. Garrick Mallery and Mr. James Mooney. They also took charge of the Iroquoian family. Rev. J. O. Dorsey’s intimate acquaintance with the tribes of the Siouan and Caddoan families peculiarly fitted him to cope with that part of the work, and he also undertook the Athapascan tribes. XXXVI Dr. W. J. Hoffman worked upon the Shoshonean tribes, aided by the Director’s personal supervision. Mr. Jeremiah Curtin, to whom was assigned the California tribes, also gave assistance in other sections.

Each of the gentlemen named has been able to contribute largely to the results by his personal experience and investigations in the field, there being numerous regions concerning which published accounts are meager and unsatisfactory. The main source of the material to be dealt with has, however, been necessarily derived from books. A vast amount of the current literature pertaining to the North American Indians has been examined, amounting to over one thousand volumes, with a view to the extraction of the tribal names and the historical data necessary to fix their precise application.

The work at the present time is well advanced toward completion. The examination of literature for the collation of synonyms may be regarded as practically done. The tables of synonymy and the accounts of the tribes have been completed for more than one-half the number of linguistic families.

ACCOMPANYING PAPERS.

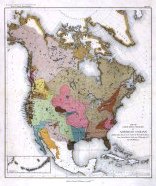

LINGUISTIC FAMILIES OF NORTH AMERICA.

In harmony with custom, three scientific papers accompany this report, designed to illustrate the nature, methods and spirit of the researches conducted by the Bureau. The first is on the “Classification of the North American Languages.” It is by no means a final paper on the subject, but is intended rather to give an account of the present status of the subject, and to place before the workers in this field of scholarship the data now existing and the conclusions already reached, so as to constitute a point of departure for new work. With this end in view Mr. Pilling is engaged upon the bibliography of the subject and is rapidly publishing the same, and Mr. Henshaw is employed on the tribal synonymy. Altogether it is hoped that this work will inaugurate a new era in the investigation of the subject by making available the vast body of XXXVII material scattered broadcast through the literature relating to the North American Indians.

In the course of these ethnic researches an interesting field of facts has been brought to view relating to the superstitions of the Indians. Already a very large body of mythology has been collected—stories from a great number of tongues which embody the rude philosophy of tribal thought. Such philosophy or opinion finds its expression not only in the mythic tales, but in the organization of the people into society, in their daily life and in their habits and customs. There is a realm of anthropology in this lower state of mankind which we call savagery, that is hard to understand from the standpoint of modern civilization, where science, theology, religion, medicine and the esthetic arts are developed as more or less discrete subjects. In savagery these great subjects are blended in one, as they are interwoven into a vast plexus of thought and action, for mythology is the basis of philosophy, religion, medicine, and art. In savagery the observed facts of the universe, relating alike to physical nature and to the humanities, are explained mythologically, and these mythic conceptions give rise to a great variety of practices. The acts of life are born of the opinions held as explanations of the environing world. Thus it is that philosophy finds expression in a complex system of superstitions, ceremonies and practices, which together constitute the religion of the people. The purpose of these practices is to avert calamity and to secure prosperity in the present life. It is astonishing to find how little the condition of a life to come is involved. The future beyond the grave is scarcely heeded, or when recognized it seems not to affect the daily life of the people to any appreciable degree. That which occupies the attention of the savage mind relates to the pleasures and pains, the joys and sorrows of present existence.

Perhaps the chief motive is derived from the consideration of health and disease, as the pleasures and pains arising therefrom are forever present to the experience or observation. Good and evil are also involved in those gifts of nature to man by which his biotic life is sustained, his food, drink, clothing XXXVIII and shelter. These bounties come not in a never-changing stream, but are apparently fitful and capricious. Seasons of plenty are accented by seasons of scarcity, and thus prosperity and adversity are strangely commingled in the history of the people. To secure this prosperity and avert this adversity seems to be the second great motive in the development of the superstitious practices of the people. A third occasion for the development of this primitive religion inheres in the social organization of mankind, primarily expressed in the love of man and woman for each other, but finally expressed in all the relations of kin and kith and in the relations of tribe with tribe. This gives rise to a very important development of primitive religion, for the savage man seeks to discover by occult agencies the power of controlling the love and good will of his kind and the power of averting the effect of enmity. To attain these ends he invents a vast system of devices, from love philters to war dances. A fourth region of exploitation in the realm of the esoteric relates to the origin of life itself, as many of their practices are designed to secure perpetuity of life by frequent births and less painful throes.

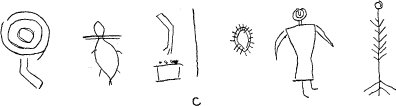

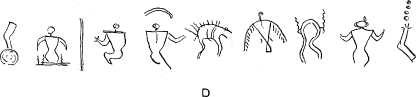

It will thus be seen that life, health, prosperity, and peace are the ends sought in all this region of human activity as they are presented in the study of savage life. The opinions held by the people on these subjects are primarily expressed in speech and organized into tales, which constitute mythology, and they are expressed in acts, as ceremonies and observances, which constitute their religion, their medicine, and their esthetic arts. These arts consist of sculpture and painting, by which their mythic beings are represented, and they also consist of dancing, by which religious fervor is produced, and they give rise to music, romance, poetry, and drama. Thus it is that the esthetic arts have their origin in mythology. The epic poem and the symphony are lineal descendants of the dance, and the dance arises as the first form of worship, born of the mythic conception of the powers of nature.

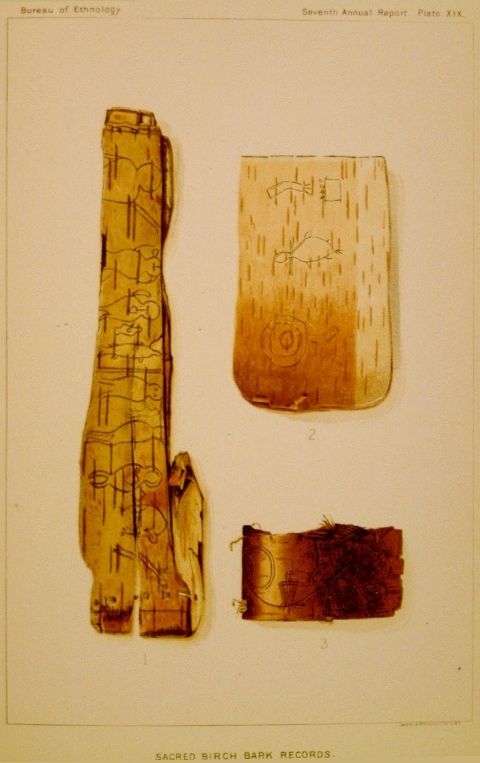

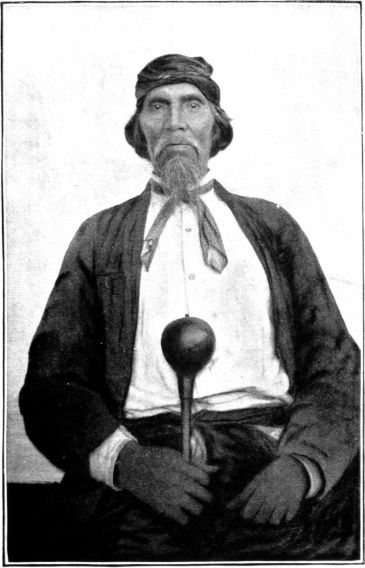

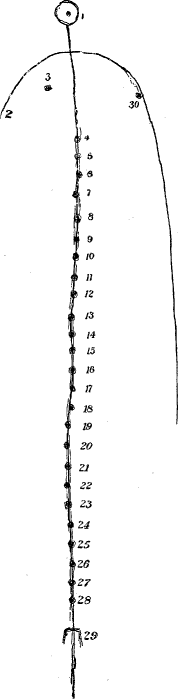

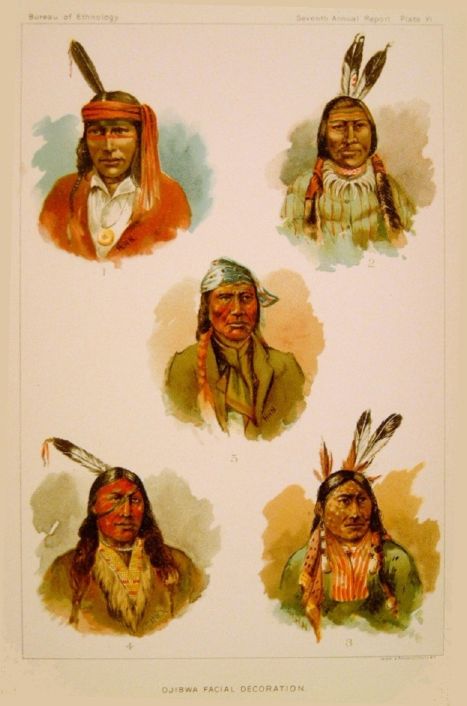

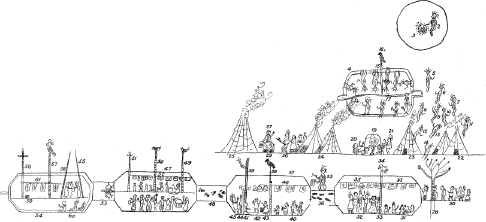

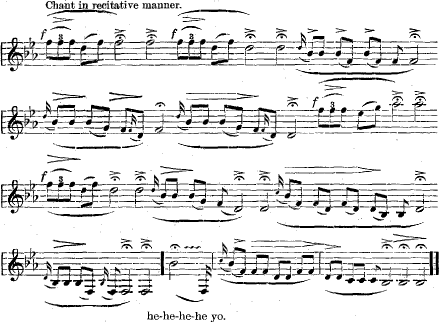

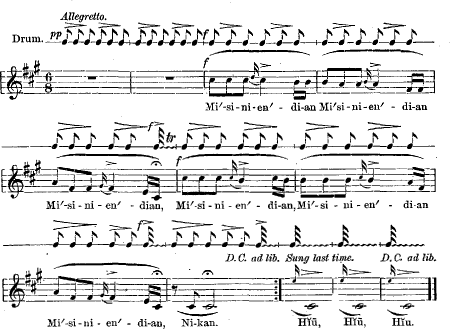

XXXIXTHE MIDĒ´WIWIN, OR GRAND MEDICINE SOCIETY OF THE OJIBWA, BY W. J. HOFFMAN, AND THE SACRED FORMULAS OF THE CHEROKEES, BY JAMES MOONEY.

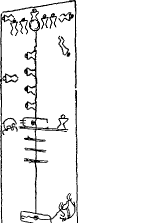

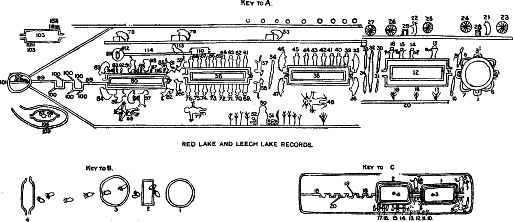

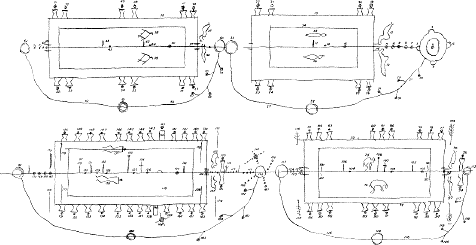

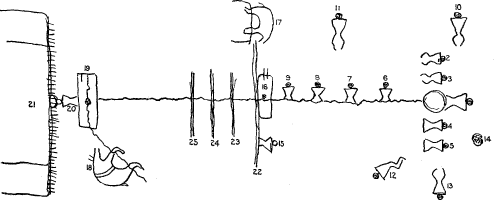

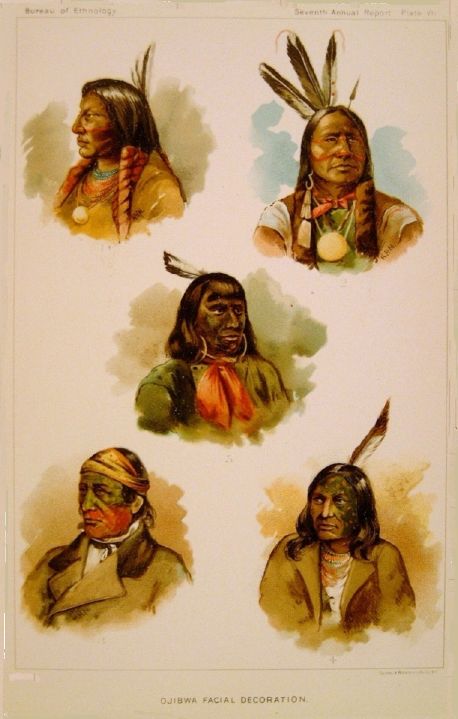

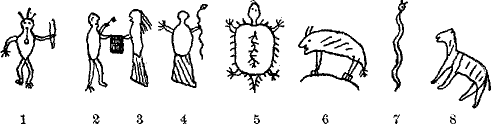

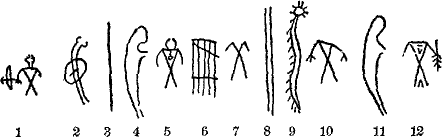

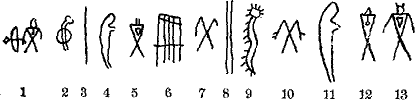

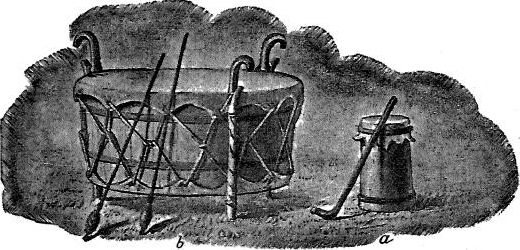

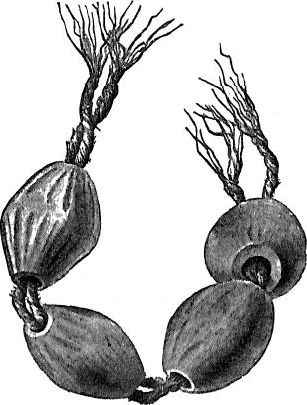

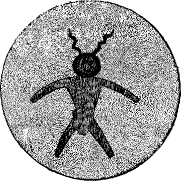

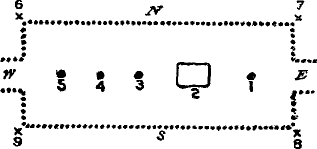

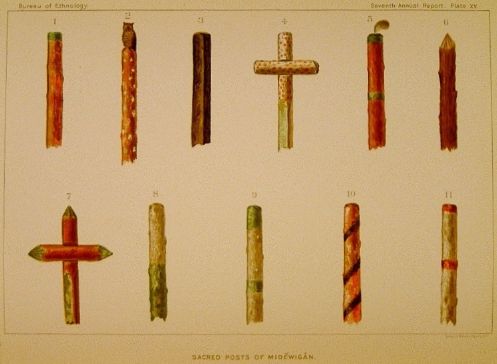

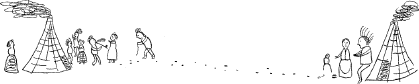

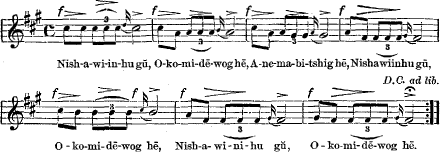

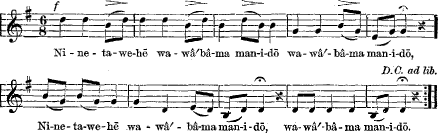

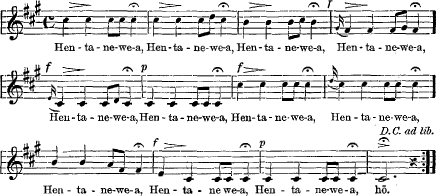

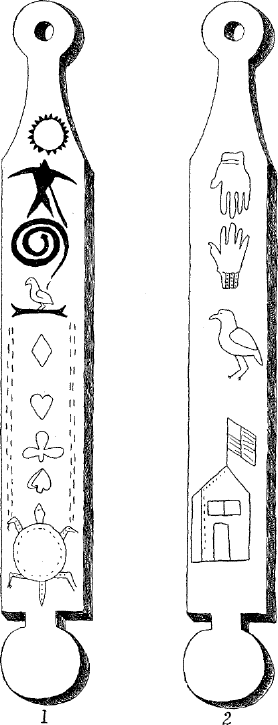

Mr. Hoffman presents a paper on the “Midē´wiwin, or Grand Medicine Society of the Ojibwa,” and sets forth the vestiges of a once powerful organization existing among these people. Mr. Mooney has made a study of the Cherokee with the same end in view. In the opinion of the Director they are important contributions to this subject. The same lines of investigation have been carried on by other members of the Bureau with other tribes where societies and practices have been but little modified by the contact of the white man, and where the subject is therefore much more plainly arrayed. In due time these additional researches will be published.

In Mr. Hoffman’s paper it is seen that two and a half centuries of association with the white man has not only served to break down this organization to some extent, but has also inculcated in the minds of the Ojibwa a clearer conception of a Great Spirit and a future life than is normal to the savage mind. Mr. Mooney, whose paper largely deals with the use of plants by the Indians for the healing of disease, naïvely compares the pharmacopoeia of savagery with that of civilization, assuming that the latter is a standard of scientific truth. Perchance scientific men will make one step in advance of this position, and will be interested in discovering the extent to which savage philosophy is still represented in civilized materia medica as expressed in officinal formulas.

A word in relation to the dramatis personæ of Indian mythology. In all those mythologies which have been studied with any degree of care up to the present time zoic deities greatly prevail, the progenitors and prototypes of the animals of the land, air, and water; yet there are other deities. Chief among these are the sun, moon, stars, fire, and the spirits of mountains and other geographical and natural phenomena. Yet these beings are largely zoomorphic, being considered rather as mythic animals than as mythic men; but it must be understood that the line of demarcation between man and the lower animals is not so clearly presented to the savage mind XL as to the civilized mind. In speaking of the theology of the North American Indians as being zoomorphic it must therefore be understood to mean that such is its chief characteristic, but not its exclusive characteristic; and further, it must be understood that it contains by survival many elements from an earlier condition in which hecastotheism prevailed, that is, that the form of philosophy known as animism was generally accepted, and that psychic life, with feeling, thought, and will, was attributed to inanimate things. But more than this, zootheism is not a permanent state of philosophy, but only a stepping-stone to something higher. That something higher may be denominated physitheism, or the worship of the powers and more obtrusive phenomena of nature. In this higher state the sun, the planets, the stars, the winds, the storms, the rainbow, and fire take the leading part. The beginnings of this higher state are to be observed in many of the mythologies of North America. It is worthy of remark that a mythology with its religion subject to the influences of an overwhelming civilization yields first in its zoomorphic elements. Zoic mythology soon degenerates into folk tales of beasts, to be recited by crones to children or told by garrulous old men as amusing stories inherited from past generations; while physitheism is more often incorporated into the compound of paganism and Christianity now held by the more advanced tribes. Notwithstanding this general tendency, zootheism is often, though not to so great an extent, compounded in the same way. The study of this stage of mythology, and of the arts and customs arising therefrom, as they are exhibited among the North American Indians, will ultimately throw a flood of light upon that later stage known as physitheism, or nature worship, now the subject of investigation by an army of Aryan scholars.

XLIFINANCIAL STATEMENT.

Table showing amounts appropriated and expended for North American ethnology for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1886.

| Expenses. | Amount expended. |

Amount appropriated. |

|---|---|---|

| Services | $31,287.93 | |

| Traveling expenses | 2,070.71 | |

| Transportation of property | 478.91 | |

| Field subsistence | 284.99 | |

| Field expenses and supplies | 360.32 | |

| Field material | 163.61 | |

| Modeling material | 63.11 | |

| Photographic material | 34.44 | |

| Books and maps | 469.69 | |

| Stationery and drawing material | 169.44 | |

| Illustrations for reports | 289.65 | |

Goods for distribution to Indians |

767.82 | |

| Office furniture | 12.00 | |

| Office supplies and repairs | 63.56 | |

| Correspondence | 13.87 | |

| Specimens | 800.00 | |

Bonded railroad accounts forwarded to Treasury for settlement |

103.84 | |

Balance on hand to meet outstanding liabilities |

2,566.11 | |

| Total | 40,000.00 | $40,000.00 |

ACCOMPANYING PAPERS.

INDIAN LINGUISTIC FAMILIES OF AMERICA

NORTH OF MEXICO.

BY

J. W. POWELL.

CONTENTS.

| Page | |

| Nomenclature of linguistic families | 7 |

Literature relating to the classification of Indian languages |

12 |

| Linguistic map | 25 |

| Indian tribes sedentary | 30 |

| Population | 33 |

| Tribal land | 40 |

| Village sites | 40 |

| Agricultural land | 41 |

| Hunting claims | 42 |

| Summary of deductions | 44 |

| Linguistic families | 45 |

| Adaizan family | 45 |

| Algonquian family | 47 |

| Algonquian area | 47 |

| Principal Algonquian tribes | 48 |

| Population | 48 |

| Athapascan family | 51 |

| Boundaries | 52 |

| Northern group | 53 |

| Pacific group | 53 |

| Southern group | 54 |

| Principal tribes | 55 |

| Population | 55 |

| Attacapan family | 56 |

| Beothuakan family | 57 |

| Geographic distribution | 58 |

| Caddoan family | 58 |

| Northern group | 60 |

| Middle group | 60 |

| Southern group | 60 |

| Principal tribes | 61 |

| Population | 62 |

| Chimakuan family | 62 |

| Principal tribes | 63 |

| Chimarikan family | 63 |

| Principal tribes | 63 |

| Chimmesyan family | 63 |

| Principal tribes or villages | 64 |

| Population | 64 |

| Chinookan family | 65 |

| Principal tribes | 66 |

| Population | 66 |

| 4 Chitimachan family | 66 |

| Chumashan family | 67 |

| Population | 68 |

| Coahuiltecan family | 68 |

| Principal tribes | 69 |

| Copehan family | 69 |

| Geographic distribution | 69 |

| Principal tribes | 70 |

| Costanoan family | 70 |

| Geographic distribution | 71 |

| Population | 71 |

| Eskimauan family | 71 |

| Geographic distribution | 72 |

| Principal tribes and villages | 74 |

| Population | 74 |

| Esselenian family | 75 |

| Iroquoian family | 76 |

| Geographic distribution | 77 |

| Principal tribes | 79 |

| Population | 79 |

| Kalapooian family | 81 |

| Principal tribes | 82 |

| Population | 82 |

| Karankawan family | 82 |

| Keresan family | 83 |

| Villages | 83 |

| Population | 83 |

| Kiowan family | 84 |

| Population | 84 |

| Kitunahan family | 85 |

| Tribes | 85 |

| Population | 85 |

| Koluschan family | 85 |

| Tribes | 87 |

| Population | 87 |

| Kulanapan family | 87 |

| Geographic distribution | 88 |

| Tribes | 88 |

| Kusan family | 89 |

| Tribes | 89 |

| Population | 89 |

| Lutuamian family | 89 |

| Tribes | 90 |

| Population | 90 |

| Mariposan family | 90 |

| Geographic distribution | 91 |

| Tribes | 91 |

| Population | 91 |

| Moquelumnan family | 92 |

| Geographic distribution | 93 |

| Principal tribes | 93 |

| Population | 93 |

| 5 Muskhogean family | 94 |

| Geographic distribution | 94 |

| Principal tribes | 95 |

| Population | 95 |

| Natchesan family | 95 |

| Principal tribes | 97 |

| Population | 97 |

| Palaihnihan family | 97 |

| Geographic distribution | 98 |

| Principal tribes | 98 |

| Piman family | 98 |

| Principal tribes | 99 |

| Population | 99 |

| Pujunan family | 99 |

| Geographic distribution | 100 |

| Principal tribes | 100 |

| Quoratean family | 100 |

| Geographic distribution | 101 |

| Tribes | 101 |

| Population | 101 |

| Salinan family | 101 |

| Population | 102 |

| Salishan family | 102 |

| Geographic distribution | 104 |

| Principal tribes | 104 |

| Population | 105 |

| Sastean family | 105 |

| Geographic distribution | 106 |

| Shahaptian family | 106 |

| Geographic distribution | 107 |

| Principal tribes and population | 107 |

| Shoshonean family | 108 |

| Geographic distribution | 109 |

| Principal tribes and population | 110 |

| Siouan family | 111 |

| Geographic distribution | 112 |

| Principal tribes | 114 |

| Population | 116 |

| Skittagetan family | 118 |

| Geographic distribution | 120 |

| Principal tribes | 120 |

| Population | 121 |

| Takilman family | 121 |

| Geographic distribution | 121 |

| Tañoan family | 121 |

| Geographic distribution | 122 |

| Population | 123 |

| Timuquanan family | 123 |

| Geographic distribution | 123 |

| Principal tribes | 124 |

| Tonikan family | 125 |

| Geographic distribution | 125 |

| 6 Tonkawan family | 125 |

| Geographic distribution | 126 |

| Uchean family | 126 |

| Geographic distribution | 126 |

| Population | 127 |

| Waiilatpuan family | 127 |

| Geographic distribution | 127 |

| Principal tribes | 127 |

| Population | 128 |

| Wakashan family | 128 |

| Geographic distribution | 130 |

| Principal Aht tribes | 130 |

| Population | 130 |

| Principal Haeltzuk tribes | 131 |

| Population | 131 |

| Washoan family | 131 |

| Weitspekan family | 131 |

| Geographic distribution | 132 |

| Tribes | 132 |

| Wishoskan family | 132 |

| Geographic distribution | 133 |

| Tribes | 133 |

| Yakonan family | 133 |

| Geographic distribution | 134 |

| Tribes | 134 |

| Population | 135 |

| Yanan family | 135 |

| Geographic distribution | 135 |

| Yukian family | 135 |

| Geographic distribution | 136 |

| Yuman family | 136 |

| Geographic distribution | 137 |

| Principal tribes | 138 |

| Population | 138 |

| Zuñian family | 138 |

| Geographic distribution | 139 |

| Population | 139 |

| Concluding remarks | 139 |

ILLUSTRATION

Plate I. Map. Linguistic stocks of North America north of Mexico. In pocket at end of volume

small format: 615×732 pixel

(about 9×11 in / 23×28 cm, 168K)

large format: 1521×1818 pixel

(about 22×27 in / 56×70 cm, 1MB)

This map is also available in very high resolution, zoomable form at the Library of Congress (link valid at time of posting).

7

INDIAN LINGUISTIC FAMILIES.

By J. W. Powell.

NOMENCLATURE OF LINGUISTIC FAMILIES.

The languages spoken by the pre-Columbian tribes of North America were many and diverse. Into the regions occupied by these tribes travelers, traders, and missionaries have penetrated in advance of civilization, and civilization itself has marched across the continent at a rapid rate. Under these conditions the languages of the various tribes have received much study. Many extensive works have been published, embracing grammars and dictionaries; but a far greater number of minor vocabularies have been collected and very many have been published. In addition to these, the Bible, in whole or in part, and various religious books and school books, have been translated into Indian tongues to be used for purposes of instruction; and newspapers have been published in the Indian languages. Altogether the literature of these languages and that relating to them are of vast extent.

While the materials seem thus to be abundant, the student of Indian languages finds the subject to be one requiring most thoughtful consideration, difficulties arising from the following conditions:

(1) A great number of linguistic stocks or families are discovered.

(2) The boundaries between the different stocks of languages are not immediately apparent, from the fact that many tribes of diverse stocks have had more or less association, and to some extent linguistic materials have been borrowed, and thus have passed out of the exclusive possession of cognate peoples.

(3) Where many peoples, each few in number, are thrown together, an intertribal language is developed. To a large extent this is gesture speech; but to a limited extent useful and important words are adopted by various tribes, and out of this material an intertribal “jargon” is established. Travelers and all others who do not thoroughly study a language are far more likely to acquire this jargon speech than the real speech of the people; and the tendency to base relationship upon such jargons has led to confusion.

8 (4) This tendency to the establishment of intertribal jargons was greatly accelerated on the advent of the white man, for thereby many tribes were pushed from their ancestral homes and tribes were mixed with tribes. As a result, new relations and new industries, especially of trade, were established, and the new associations of tribe with tribe and of the Indians with Europeans led very often to the development of quite elaborate jargon languages. All of these have a tendency to complicate the study of the Indian tongues by comparative methods.

The difficulties inherent in the study of languages, together with the imperfect material and the complicating conditions that have arisen by the spread of civilization over the country, combine to make the problem one not readily solved.

In view of the amount of material on hand, the comparative study of the languages of North America has been strangely neglected, though perhaps this is explained by reason of the difficulties which have been pointed out. And the attempts which have been made to classify them has given rise to much confusion, for the following reasons: First, later authors have not properly recognized the work of earlier laborers in the field. Second, the attempt has more frequently been made to establish an ethnic classification than a linguistic classification, and linguistic characteristics have been confused with biotic peculiarities, arts, habits, customs, and other human activities, so that radical differences of language have often been ignored and slight differences have been held to be of primary value.

The attempts at a classification of these languages and a corresponding classification of races have led to the development of a complex, mixed, and inconsistent synonymy, which must first be unraveled and a selection of standard names made therefrom according to fixed principles.

It is manifest that until proper rules are recognized by scholars the establishment of a determinate nomenclature is impossible. It will therefore be well to set forth the rules that have here been adopted, together with brief reasons for the same, with the hope that they will commend themselves to the judgment of other persons engaged in researches relating to the languages of North America.

A fixed nomenclature in biology has been found not only to be advantageous, but to be a prerequisite to progress in research, as the vast multiplicity of facts, still ever accumulating, would otherwise overwhelm the scholar. In philological classification fixity of nomenclature is of corresponding importance; and while the analogies between linguistic and biotic classification are quite limited, many of the principles of nomenclature which biologists have adopted having no application in philology, still in some important particulars the requirements of all scientific classifications are alike, 9 and though many of the nomenclatural points met with in biology will not occur in philology, some of them do occur and may be governed by the same rules.

Perhaps an ideal nomenclature in biology may some time be established, as attempts have been made to establish such a system in chemistry; and possibly such an ideal system may eventually be established in philology. Be that as it may, the time has not yet come even for its suggestion. What is now needed is a rule of some kind leading scholars to use the same terms for the same things, and it would seem to matter little in the case of linguistic stocks what the nomenclature is, provided it becomes denotive and universal.

In treating of the languages of North America it has been suggested that the names adopted should be the names by which the people recognize themselves, but this is a rule of impossible application, for where the branches of a stock diverge very greatly no common name for the people can be found. Again, it has been suggested that names which are to go permanently into science should be simple and euphonic. This also is impossible of application, for simplicity and euphony are largely questions of personal taste, and he who has studied many languages loses speedily his idiosyncrasies of likes and dislikes and learns that words foreign to his vocabulary are not necessarily barbaric.

Biologists have decided that he who first distinctly characterizes and names a species or other group shall thereby cause the name thus used to become permanently affixed, but under certain conditions adapted to a growing science which is continually revising its classifications. This law of priority may well be adopted by philologists.

By the application of the law of priority it will occasionally happen that a name must be taken which is not wholly unobjectionable or which could be much improved. But if names may be modified for any reason, the extent of change that may be wrought in this manner is unlimited, and such modifications would ultimately become equivalent to the introduction of new names, and a fixed nomenclature would thereby be overthrown. The rule of priority has therefore been adopted.

Permanent biologic nomenclature dates from the time of Linnæus simply because this great naturalist established the binominal system and placed scientific classification upon a sound and enduring basis. As Linnæus is to be regarded as the founder of biologic classification, so Gallatin may be considered the founder of systematic philology relating to the North American Indians. Before his time much linguistic work had been accomplished, and scholars owe a lasting debt of gratitude to Barton, Adelung, Pickering, and others. But Gallatin’s work marks an era in American linguistic science from the fact that he so thoroughly introduced comparative methods, and because he circumscribed the boundaries of many 10 families, so that a large part of his work remains and is still to be considered sound. There is no safe resting place anterior to Gallatin, because no scholar prior to his time had properly adopted comparative methods of research, and because no scholar was privileged to work with so large a body of material. It must further be said of Gallatin that he had a very clear conception of the task he was performing, and brought to it both learning and wisdom. Gallatin’s work has therefore been taken as the starting point, back of which we may not go in the historic consideration of the systematic philology of North America. The point of departure therefore is the year 1836, when Gallatin’s “Synopsis of Indian Tribes” appeared in vol. 2 of the Transactions of the American Antiquarian Society.

It is believed that a name should be simply a denotive word, and that no advantage can accrue from a descriptive or connotive title. It is therefore desirable to have the names as simple as possible, consistent with other and more important considerations. For this reason it has been found impracticable to recognize as family names designations based on several distinct terms, such as descriptive phrases, and words compounded from two or more geographic names. Such phrases and compound words have been rejected.

There are many linguistic families in North America, and in a number of them there are many tribes speaking diverse languages. It is important, therefore, that some form should be given to the family name by which it may be distinguished from the name of a single tribe or language. In many cases some one language within a stock has been taken as the type and its name given to the entire family; so that the name of a language and that of the stock to which it belongs are identical. This is inconvenient and leads to confusion. For such reasons it has been decided to give each family name the termination “an” or “ian.”

Conforming to the principles thus enunciated, the following rules have been formulated:

I. The law of priority relating to the nomenclature of the systematic philology of the North American tribes shall not extend to authors whose works are of date anterior to the year 1836.

II. The name originally given by the founder of a linguistic group to designate it as a family or stock of languages shall be permanently retained to the exclusion of all others.

III. No family name shall be recognized if composed of more than one word.

IV. A family name once established shall not be canceled in any subsequent division of the group, but shall be retained in a restricted sense for one of its constituent portions.

V. Family names shall be distinguished as such by the termination “an” or “ian.”

11VI. No name shall be accepted for a linguistic family unless used to designate a tribe or group of tribes as a linguistic stock.

VII. No family name shall be accepted unless there is given the habitat of tribe or tribes to which it is applied.

VIII. The original orthography of a name shall be rigidly preserved except as provided for in rule III, and unless a typographical error is evident.

The terms “family” and “stock” are here applied interchangeably to a group of languages that are supposed to be cognate.

A single language is called a stock or family when it is not found to be cognate with any other language. Languages are said to be cognate when such relations between them are found that they are supposed to have descended from a common ancestral speech. The evidence of cognation is derived exclusively from the vocabulary. Grammatic similarities are not supposed to furnish evidence of cognation, but to be phenomena, in part relating to stage of culture and in part adventitious. It must be remembered that extreme peculiarities of grammar, like the vocal mutations of the Hebrew or the monosyllabic separation of the Chinese, have not been discovered among Indian tongues. It therefore becomes necessary in the classification of Indian languages into families to neglect grammatic structure, and to consider lexical elements only. But this statement must be clearly understood. It is postulated that in the growth of languages new words are formed by combination, and that these new words change by attrition to secure economy of utterance, and also by assimilation (analogy) for economy of thought. In the comparison of languages for the purposes of systematic philology it often becomes necessary to dismember compounded words for the purpose of comparing the more primitive forms thus obtained. The paradigmatic words considered in grammatic treatises may often be the very words which should be dissected to discover in their elements primary affinities. But the comparison is still lexic, not grammatic.

A lexic comparison is between vocal elements; a grammatic comparison is between grammatic methods, such, for example, as gender systems. The classes into which things are relegated by distinction of gender may be animate and inanimate, and the animate may subsequently be divided into male and female, and these two classes may ultimately absorb, in part at least, inanimate things. The growth of a system of genders may take another course. The animate and inanimate may be subdivided into the standing, the sitting, and the lying, or into the moving, the erect and the reclined; or, still further, the superposed classification may be based upon the supposed constitution of things, as the fleshy, the woody, the rocky, the earthy, the watery. Thus the number of genders may increase, while further on in the history of a language the genders may 12 decrease so as almost to disappear. All of these characteristics are in part adventitious, but to a large extent the gender is a phenomenon of growth, indicating the stage to which the language has attained. A proper case system may not have been established in a language by the fixing of case particles, or, having been established, it may change by the increase or diminution of the number of cases. A tense system also has a beginning, a growth, and a decadence. A mode system is variable in the various stages of the history of a language. In like manner a pronominal system undergoes changes. Particles may be prefixed, infixed, or affixed in compounded words, and which one of these methods will finally prevail can be determined only in the later stage of growth. All of these things are held to belong to the grammar of a language and to be grammatic methods, distinct from lexical elements.

With terms thus defined, languages are supposed to be cognate when fundamental similarities are discovered in their lexical elements. When the members of a family of languages are to be classed in subdivisions and the history of such languages investigated, grammatic characteristics become of primary importance. The words of a language change by the methods described, but the fundamental elements or roots are more enduring. Grammatic methods also change, perhaps even more rapidly than words, and the changes may go on to such an extent that primitive methods are entirely lost, there being no radical grammatic elements to be preserved. Grammatic structure is but a phase or accident of growth, and not a primordial element of language. The roots of a language are its most permanent characteristics, and while the words which are formed from them may change so as to obscure their elements or in some cases even to lose them, it seems that they are never lost from all, but can be recovered in large part. The grammatic structure or plan of a language is forever changing, and in this respect the language may become entirely transformed.

LITERATURE RELATING TO THE CLASSIFICATION OF INDIAN LANGUAGES.

While the literature relating to the languages of North America is very extensive, that which relates to their classification is much less extensive. For the benefit of future students in this line it is thought best to present a concise account of such literature, or at least so much as has been consulted in the preparation of this paper.

1836. Gallatin (Albert).

A synopsis of the Indian tribes within the United States east of the Rocky Mountains, and in the British and Russian possessions in North America. In Transactions and Collections of the American Antiquarian Society (Archæologia Americana) Cambridge, 1836, vol. 2.