No

species of poetry is more ancient than the lyrical, and yet none shows

so little sign of having outlived the requirements of human passion. The

world may grow tired of epics and of tragedies, but each generation, as

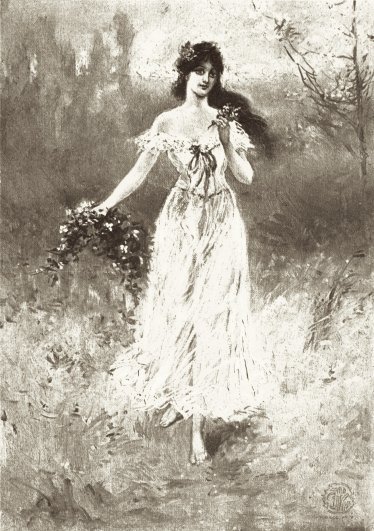

it sees the hawthorns blossom and the freshness of girlhood expand,

xxiv

is seized with a pang which nothing but the spasm of verse will relieve.

Each youth imagines that spring-tide and love are wonders which he is

the first of human beings to appreciate, and he burns to alleviate his

emotion in rhyme. Historians exaggerate, perhaps, the function of music

in awakening and guiding the exercise of lyrical poetry. The lyric

exists, they tell us, as an accompaniment to the lyre; and without the

mechanical harmony the spoken song is an artifice. Quite as plausibly

might it be avowed that music was but added to verse to concentrate and

emphasize its rapture, to add poignancy and volume to its expression.

But the truth is that these two arts, though sometimes happily allied,

are, and always have been, independent. When verse has been innocent

enough to lean on music, we may be likely to find that music also has

been of the simplest order, and that the pair of them, like two

delicious children, have tottered and swayed together down the flowery

meadows of experience. When either poetry or music is adult, the

presence of each is a distraction

xxv

to the other, and each prefers, in the elaborate ages, to stand alone,

since the mystery of the one confounds the complexity of the other. Most

poets hate music; few musicians comprehend the nature of poetry; and the

combination of these arts has probably, in all ages, been contrived, not

for the satisfaction of artists, but for the convenience of their

public.

This divorce between poetry and music has been more frankly accepted

in the present century than ever before, and is nowadays scarcely

opposed in serious criticism. If music were a necessary ornament of

lyrical verse, the latter would nowadays scarcely exist; but we hear

less and less of the poets devotion (save in a purely conventional

sense) to the lute and the pipe. What we call the Victorian lyric is

absolutely independent of any such aid. It may be that certain songs of

Tennyson and Christina Rossetti have been with great popularity “set,”

as it is called, “to music.” So far as the latter is in itself

successful, it stultifies the former; and we admit at last that the idea

of one art aiding another in this

xxvi

combination is absolutely fictitious. The beauty—even the beauty

of sound—conveyed by the ear in such lyrics as “Break, break,

break,” or “When I am dead, my dearest,” is obscured, is exchanged for

another and a rival species of beauty, by the most exquisite musical

setting that a composer can invent.

The age which has been the first to accept this condition, then,

should be rich in frankly lyrical poetry; and this we find to be the

case with the Victorian period. At no time has a greater mass of this

species of verse been produced, not even in the combined Elizabethan and

Jacobean age. But when we come to consider the quality of this later

harvest of song, we observe in it a far less homogeneous character. We

can take a piece of verse, and decide at sight that it must be

Elizabethan, or of the age of the Pléiade in France, or of a particular

period in Italy. Even an ode of our own eighteenth century is hardly to

be confounded with a fragment from any other school. The great Georgian

age introduced a wide variety into English poetry; and yet we have but

to examine the

xxvii

selected jewels strung into so exquisite a carcanet by Mr. Palgrave in

his “Golden Treasury” to notice with surprise how close a family

likeness exists between the contributions of Shelley, Wordsworth, Keats,

and Byron. The distinctions of style, of course, are very great; but the

general character of the diction, the imagery, even of the rhythm, is

more or less identical. The stamp of the same age is upon

them,—they are hall-marked 1820.

It is perhaps too early to decide that this will never be the case

with the Victorian lyrics. While we live in an age we see the

distinction of its parts, rather than their co-relation. It is said that

the Japanese Government once sent over a Commission to report upon the

art of Europe; and that, having visited the exhibitions of London,

Paris, Florence, and Berlin, the Commissioners confessed that the works

of the European painters all looked so exactly alike that it was

difficult to distinguish one from another. The Japanese eye, trained in

absolutely opposed conventions, could not tell the difference between a

Watts and a Fortuny, a Théodore Rousseau

xxviii

and a Henry Moore. So it is quite possible, it is even probable, that

future critics may see a close similarity where we see nothing but

divergence between the various productions of the Victorian age. Yet we

can judge but what we discern; and certainly to the critical eye to-day

it is the absence of a central tendency, the chaotic cultivation of all

contrivable varieties of style, which most strikingly seems to

distinguish the times we live in.

We use the word “Victorian” in literature to distinguish what was

written after the decline of that age of which Walter Scott, Coleridge,

and Wordsworth were the survivors. It is well to recollect, however,

that Tennyson, who is the Victorian writer par excellence, had published

the most individual and characteristic of his lyrics long before the

Queen ascended the throne, and that Elizabeth Barrett, Henry Taylor,

William Barnes, and others were by this date of mature age. It is

difficult to remind ourselves, who have lived in the radiance of that

august figure, that some of the most beautiful of Tennyson’s

xxix

lyrics, such as “Mariana” and “The Dying Swan” are now separated from us

by as long a period of years as divided them from Dr. Johnson and the

author of “Night Thoughts.” The reflection is of value only as warning

us of the extraordinary length of the epoch we still call “Victorian.”

It covers, not a mere generation, but much more than half a century.

During this length of time a complete revolution in literary taste might

have been expected to take place. This has not occurred, and the cause

may very well be the extreme license permitted to the poets to adopt

whatever style they pleased. Where all the doors stand wide open, there

is no object in escaping; where there is but one door, and that one

barred, it is human nature to fret for some violent means of evasion.

How divine have been the methods of the Victorian lyrists may easily be

exemplified:—

“Quoth tongue of neither maid nor wife

To heart of neither wife nor maid,

Lead we not here a jolly life

Betwixt the shine and shade?

xxx

“Quoth heart of neither maid nor wife

To tongue of neither wife nor maid,

Thou wagg’st, but I am worn with strife,

And feel like flowers that fade.”

That is a masterpiece, but so is this:—

“Nay, but you who do not love her,

Is she not pure gold, my mistress?

Holds earth aught—speak truth—above her?

Aught like this tress, see, and this tress,

And this last fairest tress of all,

—So fair, see, ere I let it fall?

“Because, you spend your lives in praisings,

To praise, you search the wide world over:

Then why not witness, calmly gazing,

If earth holds aught—speak truth—above

her?

Above this tress, and this I touch,

But cannot praise, I love so much!”

And so is this:—

“Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

xxxi

“This be the verse yon grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.”

But who would believe that the writers of these were

contemporaries?

If we examine more closely the forms which lyric poetry has taken

since 1830, we shall find that certain influences at work in the minds

of our leading writers have led to the widest divergence in the

character of lyrical verse. It will be well, perhaps, to consider in

turn the leading classes of that work. It was not to be expected that in

an age of such complexity and self-consciousness as ours, the pure song,

the simple trill of bird-like melody, should often or prominently be

heard. As civilization spreads, it ceases to be possible, or at least it

becomes less and less usual, that simple emotion should express itself

with absolute naïveté. Perhaps Burns was the latest poet in these

islands whose passion warbled forth in perfectly artless strains; and he

had the advantage of using a dialect still unsubdued and

xxxii

unvulgarized. Artlessness nowadays must be the result of the most

exquisitely finished art; if not, it is apt to be insipid, if not

positively squalid and fusty. The obvious uses of simple words have been

exhausted; we cannot, save by infinite pains and the exercise of a happy

genius, recover the old spontaneous air, the effect of an inevitable

arrangement of the only possible words.

This beautiful direct simplicity, however, was not infrequently

secured by Tennyson, and scarcely less often by Christina Rossetti, both

of whom have left behind them jets of pure emotional melody which

compare to advantage with the most perfect specimens of Greek and

Elizabethan song. Tennyson did not very often essay this class of

writing, but when he did, he rarely failed; his songs combine, with

extreme naturalness and something of a familiar sweetness, a felicity of

workmanship hardly to be excelled. In her best songs, Miss Rossetti is

scarcely, if at all, his inferior; but her judgment was far less sure,

and she was more ready to look with complacency on her failures. The

songs of Mr. Aubrey de

xxxiii

Vere are not well enough known; they are sometimes singularly charming.

Other poets have once or twice succeeded in catching this clear natural

treble,—the living linnet once captured in the elm, as Tusitala

puts it; but this has not been a gift largely enjoyed by our Victorian

poets.

The richer and more elaborate forms of lyric, on the contrary, have

exactly suited this curious and learned age of ours. The species of

verse which, originally Italian or French, have now so abundantly and so

admirably been practised in England that we can no longer think of them

as exotic, having found so many exponents in the Victorian period that

they are pre-eminently characteristic of it. “Scorn not the Sonnet,”

said Wordsworth to his contemporaries; but the lesson has not been

needed in the second half of the century. The sonnet is the most solid

and unsingable of the sections of lyrical poetry; it is difficult to

think of it as chanted to a musical accompaniment. It is used with great

distinction by writers to whom skill in the lighter divisions

xxxiv

of poetry has been denied, and there are poets, such as Bowles and

Charles Tennyson-Turner, who live by their sonnets alone. The practice

of the sonnet has been so extended that all sense of monotony has been

lost. A sonnet by Elizabeth Barrett Browning differs from one by D.

G. Rossetti or by Matthew Arnold to such excess as to make it difficult

for us to realize that the form in each case is absolutely

identical.

With the sonnet might be mentioned the lighter forms of elaborate

exotic verse; but to these a word shall be given later on. More closely

allied to the sonnet are those rich and somewhat fantastic

stanza-measures in which Rossetti delighted. Those in which Keats and

the Italians have each their part have been greatly used by the

Victorian poets. They lend themselves to a melancholy magnificence, to

pomp of movement and gorgeousness of color; the very sight of them gives

the page the look of an ancient blazoned window. Poems of this class are

“The Stream’s Secret” and the choruses in “Love is enough.” They satisfy

the appetite of our time for subtle and

xxxv

vague analysis of emotion, for what appeals to the spirit through the

senses; but here, again, in different hands, the “thing,” the metrical

instrument, takes wholly diverse characters, and we seek in vain for a

formula that can include Robert Browning and Gabriel Rossetti, William

Barnes and Arthur Hugh Clough.

From this highly elaborated and extended species of lyric the

transition is easy to the Ode. In the Victorian age, the ode, in its

full Pindaric sense, has not been very frequently used. We have

specimens by Mr. Swinburne in which the Dorian laws are closely adhered

to. But the ode, in a more or less irregular form, whether pæan or

threnody, has been the instrument of several of our leading lyrists. The

genius of Mr. Swinburne, even to a greater degree than that of Shelley,

is essentially dithyrambic, and is never happier than when it spreads

its wings as wide as those of the wild swan, and soars upon the very

breast of tempest. In these flights Mr. Swinburne attains to a volume of

sonorous melody such as no other poet, perhaps, of the world

xxxvi

has reached, and we may say to him, as he has shouted to the Mater

Triumphalis:—

“Darkness to daylight shall lift up thy pæan,

Hill to hill thunder, vale cry back to vale,

With wind-notes as of eagles Æschylean,

And Sappho singing in the nightingale.”

Nothing could mark more picturesquely the wide diversity permitted in

Victorian lyric than to turn from the sonorous and tumultuous odes of

Mr. Swinburne to those of Mr. Patmore, in which stateliness of

contemplation and a peculiar austerity of tenderness find their

expression in odes of iambic cadence, the melody of which depends, not

in their headlong torrent of sound, but in the cunning variation of

catalectic pause. A similar form has been adopted by Lord De Tabley for

many of his gorgeous studies of antique myth, and by Tennyson for his

“Death of the Duke of Wellington.” It is an error to call these iambic

odes “irregular,” although they do not follow the classic rules with

strophe, antistrophe, and epode. The enchanting “I have led her

home,” in

xxxvii

“Maud,” is an example of this kind of lyric at its highest point of

perfection.

A branch of lyrical poetry which has been very widely cultivated in

the Victorian age is the philosophical, or gnomic, in which a serious

chain of thought, often illustrated by complex and various imagery, is

held in a casket of melodious verse, elaborately rhymed. Matthew Arnold

was a master of this kind of poetry, which takes its form, through

Wordsworth, from the solemn and so-called “metaphysical” writers of the

seventeenth century. We class this interesting and abundant section of

verse with the lyrical, because we know not by what other name to

describe it; yet it has obviously as little as possible of the singing

ecstasy about it. It neither pours its heart out in a rapture, nor wails

forth its despair. It has as little of the nightingale’s rich melancholy

as of the lark’s delirium. It hardly sings, but, with infinite decorum

and sobriety, speaks its melodious message to mankind. This sort of

philosophical poetry is really critical; its function is to analyze and

describe; and it approaches,

xxxviii

save for the enchantment of its form, nearer to prose than do the other

sections of the art. It is, however, just this species of poetry which

has particularly appealed to the age in which we live; and how naturally

it does so may be seen in the welcome extended to the polished and

serene compositions of Mr. William Watson.

Almost a creation, or at least a complete conquest, of the Victorian

age is the humorous lyric in its more delicate developments. If the past

can point to Prior and to Praed, we can boast, in their various

departments, of Calverly, of Locker-Lampson, of Mr. Andrew Lang, of Mr.

W. S. Gilbert. The comic muse, indeed, has marvellously extended

her blandishments during the last two generations, and has discovered

methods of trivial elegance which were quite unknown to our forefathers.

Here must certainly be said a word in favor of those French forms of

verse, all essentially lyrical, such as the ballad, the rondel, the

triolet, which have been used so abundantly as to become quite a

xxxix

feature in our lighter literature. These are not, or are but rarely,

fitted to bear the burden of high emotion; but their precision, and the

deftness which their use demands fit them exceedingly well for the more

distinguished kind of persiflage. No one has kept these delicate

butterflies in flight with the agile movement of his fan so admirably as

Mr. Austin Dobson, that neatest of magicians.

Those who write hastily of Victorian lyrical poetry are apt to find

fault with its lack of spontaneity. It is true that we cannot pretend to

discover on a greensward so often crossed and re-crossed as the poetic

language of England many morning dewdrops still glistening on the

grasses. We have to pay the penalty of our experience in a certain lack

of innocence. The artless graces of a child seem mincing affectations in

a grown-up woman. But the poetry of this age has amply made up for any

lack of innocence by its sumptuous fulness, its variety, its magnificent

accomplishment, its felicitous response to a multitude of moods and

apprehensions.

xl

It has struck out no new field for itself; it still remains where the

romantic revolution of 1798 placed it; its aims are not other than were

those of Coleridge and of Keats. But within that defined sphere it has

developed a surprising activity. It has occupied the attention and

become the facile instrument of men of the greatest genius, writers of

whom any age and any language might be proud. It has been tender and

fiery, severe and voluminous, gorgeous and marmoreal, in turns. It has

translated into words feelings so subtle, so transitory, moods so

fragile and intangible, that the rough hand of prose would but have

crushed them. And this, surely, indicates the great gift of Victorian

lyrical poetry to the race. During a time of extreme mental and moral

restlessness, a time of speculation and evolution, when all illusions

are tested, all conventions overthrown, when the harder elements of life

have been brought violently to the front, and where there is a

temptation for the emancipated mind roughly to reject what is not

material and obvious, this art has preserved intact the

xli

lovelier delusions of the spirit, all that is vague and incorporeal and

illusory. So that for Victorian Lyric generally no better final

definition can be given than is supplied by Mr. Robert Bridges in a

little poem of incomparable beauty, which may fitly bring this essay to

a close:—

“I have loved flowers that fade,

Within whose magic tents

Rich hues have marriage made

With sweet immemorial scents:

A joy of love at sight,—

A honeymoon delight,

That ages in an hour:—

My song be like a flower.

“I have loved airs that die

Before their charm is writ

Upon the liquid sky

Trembling to welcome it.

Notes that with pulse of fire

Proclaim the spirit’s desire,

Then die, and are nowhere:—

My song be like an air.”

Edmund Gosse.

![]()

![]()

![]()