Title: The Scholfield Wool-Carding Machines

Author: Grace Rogers Cooper

Release date: November 3, 2008 [eBook #27137]

Most recently updated: January 4, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Greg Bergquist

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

Contributions from

The Museum of History and Technology:

Paper 1

The Scholfield Wool-Carding Machines

Grace L. Rogers

| PRIMITIVE CARDING | 3 |

| THE FIRST MECHANICAL CARDS | 5 |

| JOHN AND ARTHUR SCHOLFIELD | 8 |

| THE NEWBURYPORT WOOLEN MANUFACTORY | 9 |

| THE SCHOLFIELD MACHINES | 12 |

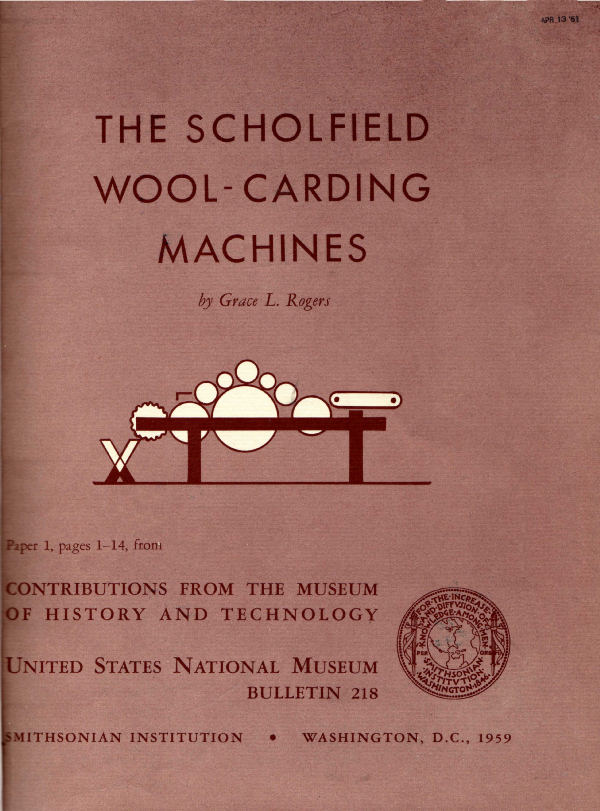

Figure 1.—An Original Scholfield Wool-Carding

Machine, built by Arthur Scholfield or under

his immediate direction between 1803 and 1814, as

exhibited in the hall of textiles of the U.S. National

Museum (cat. no. T11100). The exhibits in this

hall are part of those being prepared for the enlarged

hall of textiles in the new Museum of History and

Technology now under construction. (Smithsonian

photo 45396.)

Figure 1.—An Original Scholfield Wool-Carding

Machine, built by Arthur Scholfield or under

his immediate direction between 1803 and 1814, as

exhibited in the hall of textiles of the U.S. National

Museum (cat. no. T11100). The exhibits in this

hall are part of those being prepared for the enlarged

hall of textiles in the new Museum of History and

Technology now under construction. (Smithsonian

photo 45396.)

By Grace L. Rogers

First to appear among the inventions that sparked the industrial revolution in textile making was the flying shuttle, then various devices to spin thread and yarn, and lastly machines to card the raw fibers so they could be spun and woven. Carding is thus the important first step. For processing short-length wool fibers its mechanization proved most difficult to achieve.

To the United States in 1793 came John and Arthur Scholfield, bringing with them the knowledge of how to build a successful wool-carding machine. From this contribution to the technology of our then infant country developed another new industry.

The Author: Grace L. Rogers is curator of textiles, Museum of History and Technology, in the Smithsonian Institution's United States National Museum.

Carding is the necessary preliminary step by which individual short fibers of wool or cotton are separated and cleaned of foreign materials so they can be spun into yarn. The thoroughness of the carding determines the quality of the yarn, while the position in which the carded fibers are laid determines its type. The fibers are laid parallel in order to spin a smooth compact yarn, or they are crossed and intermingled to produce a soft bulky yarn.

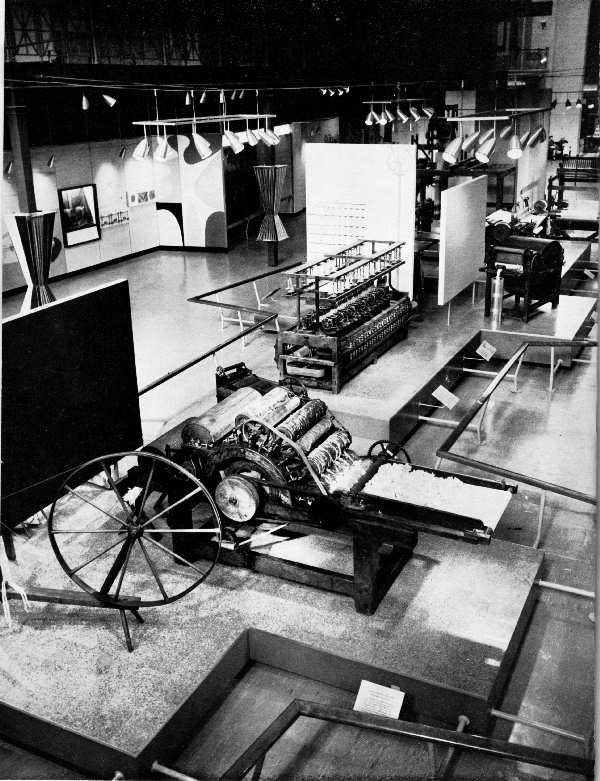

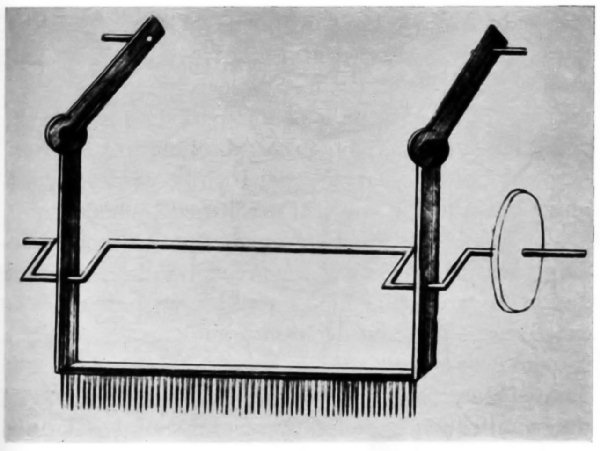

The earliest method of carding wool was probably one in which, by use of the fingers alone, the tufts were pulled apart, the foreign particles loosened and extracted, and the fibers blended. Fuller's teasels (thistles with hooked points, Dispasacus fullonum), now better known for raising the nap on woven woolens, were also used at a very early date for carding. The teasels were mounted on a pair of small rectangular frames with handles; and from this device developed the familiar small hand card (see fig. 2), measuring about 8 inches by 5 inches, in which card clothing (wire teeth embedded in leather) was mounted on a board with the wire teeth bent and angled toward the handle. The wool was placed on one card and a second card was dragged across it, the two hands pulling away from each other. This action separated the fibers and laid them parallel to the handle, in a thin film. After the fibers had been carded in this way several times, the cards were turned so that the handles were together and once again they were pulled across each other. With the wire teeth now angled in the same direction, the action rolled the carded fibers into a sliver (a loose roll of untwisted fibers) that was the length of the hand card and about the diameter of the finger. This placed the wool fibers crosswise in relation to the length of the sliver, their best position for spinning.[1] Until the mid-18th century hand cards were the only type of implement available for carding.

Figure 2.—Hand Cards "Used on Plantation of Mary C. Purvis," Nelson County, Virginia,

during early 1800's and now in U.S. National Museum (cat. no. T2848; Smithsonian

photo 37258).

Figure 2.—Hand Cards "Used on Plantation of Mary C. Purvis," Nelson County, Virginia,

during early 1800's and now in U.S. National Museum (cat. no. T2848; Smithsonian

photo 37258).

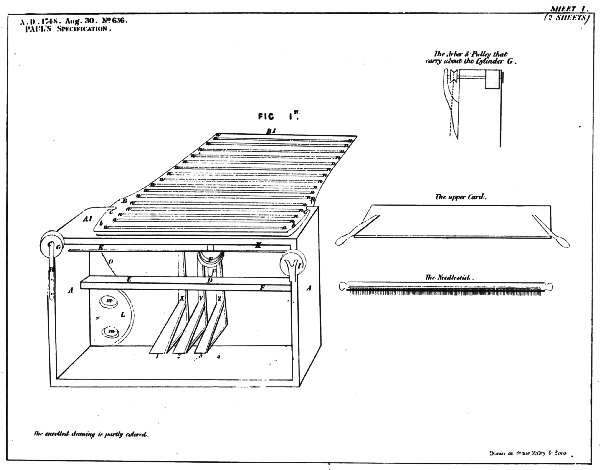

Figure 3.—The First Machine in Lewis Paul's British Patent 636, Issued August 30, 1748.

The treadle move the card-covered board B1, in a horizontal direction as necessary to perform

the carding operation. With the aid of the needlestick the fibers were removed separately

from each of the 16 cards N. The carded fibers were placed on a narrow cloth band, which

unrolled from the small cylinder G, on the left, and was rolled up with the fibers on the cylinder

I, at the right.

Figure 3.—The First Machine in Lewis Paul's British Patent 636, Issued August 30, 1748.

The treadle move the card-covered board B1, in a horizontal direction as necessary to perform

the carding operation. With the aid of the needlestick the fibers were removed separately

from each of the 16 cards N. The carded fibers were placed on a narrow cloth band, which

unrolled from the small cylinder G, on the left, and was rolled up with the fibers on the cylinder

I, at the right.

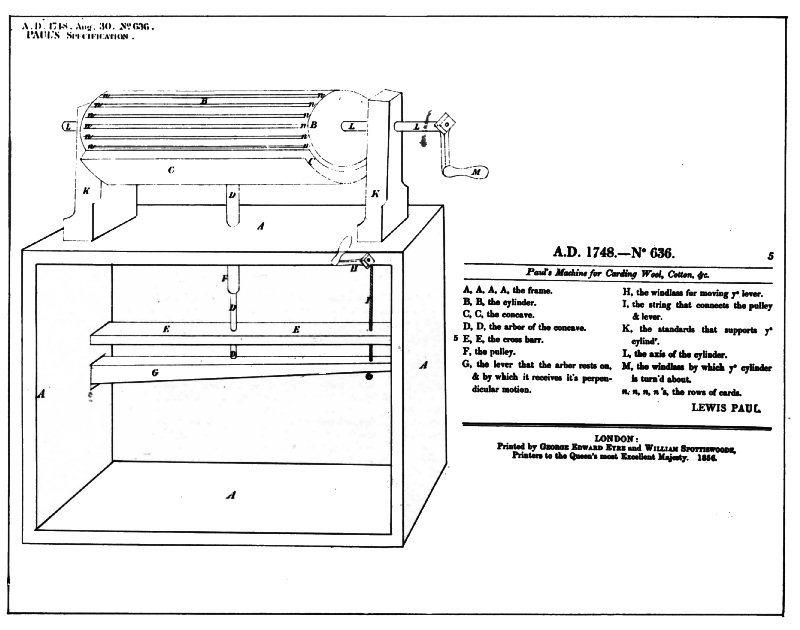

The earliest mechanical device for carding fibers was invented by Lewis Paul in England in 1738 but not patented until August 30, 1748. The patent described two machines. The first, and less important, machine consisted of 16 narrow cards mounted on a board; a single card held in the hand performed the actual carding operation (see fig. 3). The second machine utilized a horizontal cylinder covered with parallel rows of card clothing. Under the cylinder was a concave frame lined with similar card clothing. As the cylinder was turned, the cards on it worked against those on the concave frame, separating and straightening the fibers (see fig. 4). After the fibers were carded, the concave section was lowered and the fibers were stripped off by hand with a needle stick, an implement resembling a comb with very fine needlelike metal teeth. Though his machine was far from perfect. Lewis Paul had invented the carding cylinder working with stationary cards and the stripping comb.

Figure 4.—The Patent Description of Paul's

Second Machine suggested that the fibers be carded

by a cylinder action, but be removed in the same

manner as directed in the first patent.

Figure 4.—The Patent Description of Paul's

Second Machine suggested that the fibers be carded

by a cylinder action, but be removed in the same

manner as directed in the first patent.

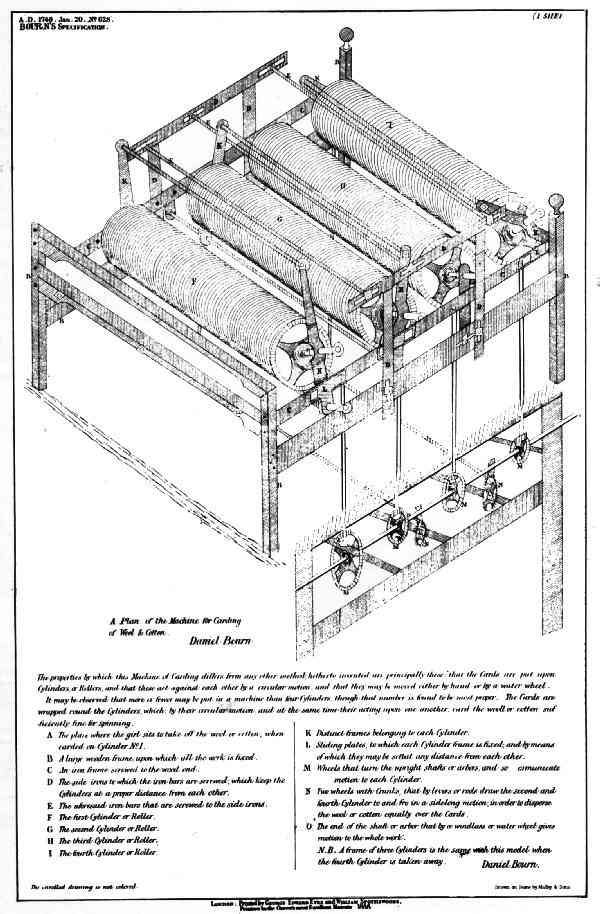

Figure 5.—Illustrations From British Patent 628, Issued January 20, 1748,

to Daniel Bourn for a roller card machine.

Figure 5.—Illustrations From British Patent 628, Issued January 20, 1748,

to Daniel Bourn for a roller card machine.

Figure 6.—The Most Important Single Feature

Illustrated in Richard Arkwright's British patent 1111

of December 16, 1775, provided "a crank and a

frame of iron with teeth" to remove the carded fibers

from the cylinder.

Figure 6.—The Most Important Single Feature

Illustrated in Richard Arkwright's British patent 1111

of December 16, 1775, provided "a crank and a

frame of iron with teeth" to remove the carded fibers

from the cylinder.

Another important British patent was granted in 1748 to Daniel Bourn, who invented a machine with four carding rollers set close together, the first of the roller-card type (see fig. 5). To produce a practical carding machine, however, several additional mechanical improvements were necessary. The first of these did not appear until more than two decades later, in 1772, when John Lees of Manchester is reported to have invented a machine featuring "a perpetual revolving cloth, called a feeder," that fed the fibers into the machine.[2] Shortly afterward, the stripper rollers[3] and the doffer comb[4] (a mechanical utilization of Paul's hand device) were added. Both James Hargreaves and Richard Arkwright claimed to be the inventor of these improvements, but it was Arkwright who, in 1775, first patented these ideas. His comb and crank (see fig. 6) provided a mechanical means by which the carded fibers could be removed from the cylinder. With this, the cylinder card became a practical machine. Arkwright continued the modification of the doffing end by drawing the carded fibers through a funnel and then passing them through two rollers. This produced a continuous sliver, a narrow ribbon of fibers ready to be spun into yarn. However, it was soon realized that the bulk characteristic desired in woolen yarns (but not desired in the compact types such as worsted yarns or cotton yarns) required that the wool be carded in a machine that would help produce this.

Figure 7.—Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1796, an Engraving From John J. Currier's

History of Newburyport, Massachusetts, 1764–1909, vol. 2, Newburyport, 1906–09.

Figure 7.—Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1796, an Engraving From John J. Currier's

History of Newburyport, Massachusetts, 1764–1909, vol. 2, Newburyport, 1906–09.

In carding wool it was found more effective to omit the flat stationary cards and to use only rollers to work the fibers. The method of preparing the sliver also had to be changed. Since it was necessary to remove the wool fibers crosswise in the sliver, a fluted wooden cylinder called a roller-bowl was used in conjunction with an under board or shell. As a given section of the carded wool was fed between the fluted cylinder and the board, the action of the cylinder rolled the fibers into a sliver about the diameter of the finger and the length of the cylinder. Although these were only 24-inch lengths as compared to the continuous sliver produced by the Arkwright cotton-carding machine,[5] wool could still be carded with much more speed and thoroughness than with the small hand cards. This then was the state of mechanical wool carding in England in the 1790's as two experienced wool manufacturers, John and Arthur Scholfield, planned their trip to America.

The Scholfields, however, were not to be the first to introduce mechanical wool carding into America. Several attempts had been made prior to their arrival. In East Hartford, Connecticut, "about 1770 Elisha Pitkin had built a mill on the east side of Main Street near the old meeting-house and Hockanum Bridge, which was run by water-power, supplied by damming the Hockanum River. Here, beside grinding grain and plaster, was set up the first wool-carding machine in the state, and, it is believed, in the country."[6] Samual Mayall in Boston, about 1788 or 1789, set up a carding machine operated by horse power. In 1791 he moved to Gray, Maine, where he operated a shop for wool carding and cloth dressing.[7] Of the machines used at the Hartford Woolen Manufactory, organized in 1788, a viewer reported he saw "two carding-engines, working by water, of a very inferior construction." They were further described as having "two large center cylinders in each, with two doffers, and only two working cylinders, of the breadth of bare sixteen inches, said to be invented by some person there."[8] But these were isolated examples; most of the woolen mills of this period were like the one built in 1792 by John Manning in Ipswich, Massachusetts, where all the work of carding, spinning, and weaving was still performed by hand.

The Scholfields' knowledge of mechanical wool-processing was to find a welcome reception in this young nation now struggling for economic independence. The exact reason for their decision to embark for America is unknown. However, it may well be that they, like Samuel Slater[9] some three years earlier, had learned of the bounties being offered by several state legislatures for the successful introduction of new textile machines.

Both John and Arthur were experienced in the manufacture of woolens. They were the sons of a clothier (during the 18th century, a person who performed the several operations in finishing cloth) and had been apprenticed to the trade. Arthur was 36 and a bachelor; John, a little younger, was married and had six children. Arthur and John, with his family, sailed from Liverpool in March 1793 and arrived in Boston some two months later. Upon arrival, their immediate concern was to find a dwelling place for John's family. Finally they were accommodated by Jedediah Morse, well-known author of Morse's geography and gazetteer, in a lodging in Charlestown, near Bunker Hill. In less than a month John began to build a spinning jenny and a hand loom, and soon the Scholfields started to produce woolen cloth. The two brothers were joined in the venture by John Shaw, a spinner and weaver who had migrated from England with them. Morse, being much impressed with some of the broadcloth they produced, was especially interested to find that John and Arthur understood the actual construction of the textile machines. Morse immediately recommended the Scholfields to some wealthy persons of Newburyport (see fig. 7), who were interested in sponsoring a new textile mill.

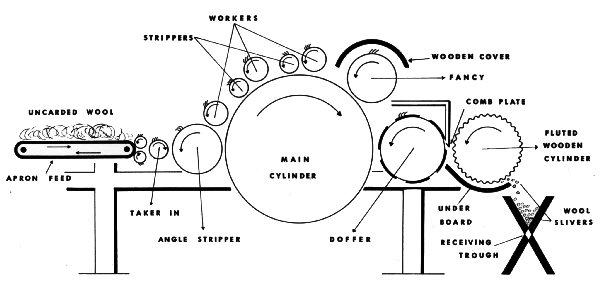

Figure 8.—Cross-Section of a Scholfield Wool-Carding Machine. The wool was fed

into the machine from a moving apron, locked in by a pair of rollers, and passed from the

taker-in roller to the angle stripper. This latter roller transferred the wool on to the main

cylinder and acted as a stripper for the first worker roller. After passing through two more

workers and strippers, the wool was prepared for leaving the main cylinder by the fancy, a

roller with longer wire teeth set to reach into the card clothing of the large cylinder. Then

the doffer roller picked up the carded fibers from the main cylinder in 4-inch widths the length

of the roller. These sections were freed by the comb plate, passed between the fluted wooden

cylinder and an under board, where they were converted into slivers, and deposited into a

small wooden trough.

Figure 8.—Cross-Section of a Scholfield Wool-Carding Machine. The wool was fed

into the machine from a moving apron, locked in by a pair of rollers, and passed from the

taker-in roller to the angle stripper. This latter roller transferred the wool on to the main

cylinder and acted as a stripper for the first worker roller. After passing through two more

workers and strippers, the wool was prepared for leaving the main cylinder by the fancy, a

roller with longer wire teeth set to reach into the card clothing of the large cylinder. Then

the doffer roller picked up the carded fibers from the main cylinder in 4-inch widths the length

of the roller. These sections were freed by the comb plate, passed between the fluted wooden

cylinder and an under board, where they were converted into slivers, and deposited into a

small wooden trough.

A Newburyport philanthropist, Timothy Dexter, contributed the use of his stable. There, beginning in December 1793, the Scholfields built a 24-inch, single-cylinder, wool-carding machine. They completed it early in 1794, the first Scholfield wool-carding machine in America. The group was so impressed that they organized the Newburyport Woolen Manufactory. Arthur was hired as overseer of the carding and John as overseer of the weaving and also as company agent for the purchase of raw wool. A site was chosen on the Parker River in Byfield Parish, Newbury, where a building 100 feet long, about half as wide, and three stories high was constructed. To the new factory were moved the first carding machine, two double-carding machines, as well as spinning, weaving and fulling machines. The carding machines were built by Messrs. Standring, Armstrong, and Guppy, under the Scholfields' immediate direction. All the machinery with the exception of the looms was run by water-power; the weaving was done by hand. The enterprise was in full operation by 1795.

John and Arthur Scholfield (and John's 11-year-old son, James) worked at the Byfield factory for several years. During a wool-buying trip to Connecticut in 1798, John observed a valuable water-power site at the mouth of the Oxoboxo River, in the town (i.e., township) of Montville, Connecticut. Here, the brothers decided, would be a good place to set up their own mill, and on April 19, 1799, they signed a 14-year lease for the water site, a dwelling house, a shop, and 17 acres of land. As soon as arrangements could be completed, Arthur, John, and the latter's family left for Montville.

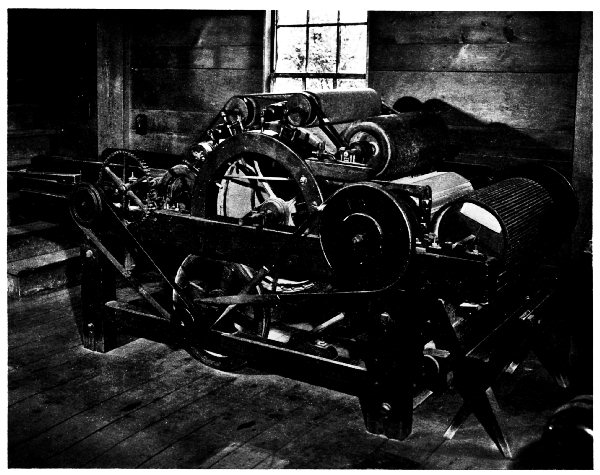

Figure 9.—In the Collection of the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, Michigan, Is This

Original Scholfield Wool-Carding Machine of the early 19th century. (Photo courtesy of

the Henry Ford Museum.)

Figure 9.—In the Collection of the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, Michigan, Is This

Original Scholfield Wool-Carding Machine of the early 19th century. (Photo courtesy of

the Henry Ford Museum.)

The Scholfields quite probably did not take any of the textile machinery from the Byfield factory with them to Connecticut—first because the machines were built while the brothers were under hire and so were the property of the sponsors, and second because their knowledge of how to build the machines would have made it unnecessary to incur the inconvenience and expense of transporting machines the hundred odd miles to Montville. However, John Scholfield's sons reported[10] that they had taken a carding engine with them when they moved to Connecticut in 1799 and had later transferred it to a factory in Stonington. The sons claimed that the frame, cylinders, and lags of the machine were made of mahogany and that it had originally been imported from England. However, it would have been most uncommon for a textile machine, even an English one, to have been constructed of mahogany; and having built successful carding machines, the men at Byfield would have found it unnecessary to attempt the virtually impossible feat of importing an English one. If it ever existed and was taken to Connecticut, therefore, this machine was probably not a carding machine manufactured by the Scholfields. It is more probable that the first Scholfield carding machine remained in the Byfield mill as the property of the Newburyport Woolen Manufactory.

Figure 10.—An Original Scholfield Wool-Carding Machine at Old Sturbridge Village,

Sturbridge, Massachusetts. It is now run by electricity. (Photo courtesy of Old Sturbridge Village.)

Figure 10.—An Original Scholfield Wool-Carding Machine at Old Sturbridge Village,

Sturbridge, Massachusetts. It is now run by electricity. (Photo courtesy of Old Sturbridge Village.)

During the next half century, this mill was held by a number of individuals. William Bartlett and Moses Brown, two of the leading stockholders of the company, sold it in 1804 to John Lees, the English overseer who succeeded the Scholfields, and he continued to operate it for about 20 years. On August 24, 1824, the mill was purchased at a Sheriff's sale by Gorham Parsons, who sold a part interest to Paul Moody, a machinist from the textile town of Lowell. Moody operated the mill for the next 5 years and at his death in 1831 his heirs sold their interest back to Parsons. In 1832 it was leased for 7 years by William N. Cleveland and Solomon Wilde under the name of William N. Cleveland & Co. Following the expiration of the lease in 1839, a portion of the mill was occupied for 3 or 4 years by Enoch Pearson, believed to have been a descendant of the John Pearson who had been a clothier in Rowley in 1643, and subsequently various industries occupied other portions and later the entire building, which burned with all its contents on October 29, 1859.

If the first Scholfield carding machine remained a part of the property, therefore it must have been lost in that fire. However, the Scholfields' importance to American wool manufacture was not contingent on the building of one successful carding machine, regardless of whether it was the first. It was the change in the scope of their business ventures after their move to Connecticut that synonymized the name of Scholfield with mechanical wool carding in America.

John and Arthur had built their woolen mill at Uncasville, a village in the town of Montville, and there Arthur remained with his brother until 1801, when he married, sold his interest to John, and moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts. John and his sons continued to operate the mill until 1806, when difficulties over water privileges spurred him to purchase property in Stonington, Connecticut, where he built a new mill containing two double-cylinder carding machines.[11] In 1813, leaving one son in charge at Stonington, John returned to Montville and purchased another factory and water privileges. He continued in the woolen manufacture until his death in 1820.

Arthur, soon after arriving in Pittsfield, constructed a carding machine and opened a Pittsfield mill. The following advertisement appeared in the Pittsfield Sun, November 2, 1801:

Arthur Scholfield respectfully informs the inhabitants of Pittsfield and the neighboring towns, that he has a carding-machine half a mile west of the meeting-house, where they may have their wool carded into rolls for 12-1⁄2 cents per pound; mixed 15-1⁄2 cents per pound. If they find the grease, and pick and grease it, it will be 10 cents per pound, and 12-1⁄2 cents mixed. They are requested to send their wool in sheets as they will serve to bind up the rolls when done. Also a small amount of woolens for sale.

The people around Pittsfield soon realized that the mechanically carded wool was not only much easier to spin but enabled them to produce twice as much yarn from the same amount of wool. Although many brought their wool to be carded at his factory, Arthur was not without problems. These were evident in his advertisement of May 1802, in which he stated that if the wool was not properly "sorted, clipped, and cleansed" he would charge an extra penny per pound. He also added that he would issue no credit. Shortly after this, recognizing the need for additional carding machines in other localities, Arthur Scholfield undertook the work of manufacturing such machines for sale. Through this venture he was to spread his knowledge of mechanical wool carding throughout the country.

The first record of Arthur's sale of carding machines appeared in the Pittsfield Sun in September 1803. The next year, in May 1804, his advertisement informed the readers that A. Scholfield continued to card wool, and also that:

He has carding-machines for sale, built under his immediate inspection, upon a new and improved plan, which he is determined to sell on the most liberal terms, and will give drafts and other instructions to those who wish to build for themselves; and cautions all whom it may concern to beware how they are imposed upon by uninformed speculating companies, who demand more than twice as much for machines as they are really worth.

Scholfield must have felt that some of his competitors were charging much more for their carding machines than they were worth. Also, others were producing inferior machines that did not card the wool properly. Both factors encouraged Arthur to continue the commercial production of wool-carding machines. In April 1805 he again advertised:

Good news for farmers, only eight cents per pound for picking, greasing, and carding white wool, and twelve and a half cents for mixed. For sale, Double Carding-machines, upon a new and improved plan, good and cheap.

And in 1806:

Double carding machines, made and sold by A. Scholfield for $253 each, without the cards, or $400 including the cards. Picking machines at $30 each. Wool carded on the same terms as last year, viz.: eight cents per pound for white, and twelve and a half cents for mixed, no credit given.

With both carpenters and machinists working under his direction, he soon abandoned completely the carding of wool and devoted his full time to producing carding machines. An advertisement in the Pittsfield Sun shows Alexander and Elisha Ely providing carding service there with a Scholfield machine in 1806. Scholfield machines were also set up in Massachusetts at Bethuel Baker, Jr., & Co. in Lanesborough in 1805, at Walker & Worthington in Lenox, at Curtis's Mills in Stockbridge, at Reuben Judd & Co. in Williamstown, in Lee at the falls near the forge, at Bairds' Mills in Bethlehem in 1806, and by John Hart in Cheshire in 1807. Subsequently many more Scholfield machines were set up in many other places as far away as Manchester, New Hampshire, in 1809 and Mason Village, New Hampshire, in about 1810.

One of the difficulties that Arthur encountered in building these early machines was in cutting the comb plates that freed the carded fleece from the cylinder. These plates had to be prepared by hand, the teeth being cut and filed one by one. In 1814 James Standring, an old friend and co-worker, smuggled into this country a "teeth-cutting machine," which he had procured on a trip to England.[12] Standring kept the machine closely guarded, permitting only Scholfield and one other friend to see it. Standring used his machine to make new saws of all descriptions and to re-cut old ones as well as to prepare comb plates for the carding machines. But in spite of this new simplified method of producing comb plates Scholfield's business did not flourish, for the tremendous influx of foreign fabrics after the War of 1812 greatly damaged the domestic textile industries, including the manufacture of carding machines.

By 1818 Scholfield's friends had persuaded him to apply to Congress for relief. To his brother John on April 20, 1818, he wrote:

... I have been advised by my friends to apply to Congress by a petition as we were the first that introduced the woolen Business by Machinery in this country and should that plan be adopted I have but little hopes of success but they say if it does no good it wont doo any harm but at any rate I should like your opinion and advice about it....

Apparently John felt the plan would not succeed, for on the following December 17 Arthur wrote him again:

... With regard to applying to Congress I have given that up for I am of your opinion that it won't succeed what gave me some hopes I was advis'd to it by a member of the Senet who is a very influential man in Congress but he is now out and I think tis best to drop it....

Arthur never applied to Congress for the recognition his contemporaries felt he deserved.[13]

Several changes in the construction of wool-carding machines took place during this period. As early as 1816 John Scholfield, Jr., was reported to have in his mill in Jewett City, Connecticut, a double-cylinder carding machine 3 feet wide. And in 1822 a Worcester, Massachusetts, machine maker advertised that he was "constructing carding machines entirely of iron."[14] Although a few of these iron carding machines were sold, they did not become common until 50 years later.[15]

There is no record that Arthur Scholfield manufactured carding machines of a width greater than 24 inches, or entirely of iron. However, little is known of his last business years except that he remained in Pittsfield until his death, March 27, 1827.

Only three wool-carding machines attributed to the hands of the Scholfields are known to exist today. All are 24-inch, single-cylinder carding machines of the same general description (see fig. 8). They differ only in minor respects that probably result from subsequent changes and additions. One (fig. 9), now located in the Plymouth Carding House, at Greenfield Village, Dearborn, Michigan, was discovered in Ware, Massachusetts. Another (fig. 10), now at Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge, Massachusetts,[16] was uncovered in a barn in northern New Hampshire. The third (fig. 1), is in the U.S. National Museum in the collection of the Division of Textiles.

Both it and the Dearborn machine have in former times been described as "the original Scholfield woolen card." It is a romantic but unsubstantiated idea that either of these is the first Scholfield carding machine set up in the Byfield factory in 1794. The author's opinion is that all three were built by Arthur Scholfield during his years in the Pittsfield factory. Examination of the National Museum machine supports this opinion. The woods used are all native to the New England region. The frame, the large cylinder and the roller called the fancy are constructed of eastern white pine (the Sturbridge machine is also constructed principally of pine). The joints of the main frame are mortised and tenoned. At the doffing end the main frame and cross supports are numbered and matched, I to IIII, and at the feed end they are numbered V to VIII but were mis-matched in the original assembly. Further rigidity is achieved by means of hand-forged lag screws. The arch of the frame is birch and the arch arm maple. The 14-inch doffer roller is made of chestnut.[17] The iron shafts are square and turned down at the bearings. The worker rollers are fitted with sprockets and turned by a hand-forged chain. The comb plate, stamped "Standring," is hand filed, and is undoubtedly one of those made before the "teeth-cutting machine" was smuggled from England, for although one-third of the plate is quite regular, the size and pitch of the teeth in the remaining two-thirds are irregular. Part of this irregularity might be explained as having been caused by the hand-sharpening of a plate originally cut by machine, but the teeth in one 2-inch span not only vary in size but have a pitch that would have been impossible to produce after the original plate had been made.[18]

There is no doubt that this carding machine was made by Arthur Scholfield, or under his immediate supervision, sometime between 1803 and 1814. It may well be one of the machines sent to southern New Hampshire in 1809 or 1810, as it is known to have been run in Nashua and Jeffrey, New Hampshire, in the 1820's and 1830's, after which it was run by James Townsend in Marlboro, New Hampshire, from 1837 until 1890, when it was exhibited at the Mechanics Fair in Boston. Mr. Rufus S. Frost purchased the machine and owned it until his death in 1897. When the Frost estate was settled, the old Scholfield wool-carding machine was purchased by the Davis & Furber Machine Co., by which in 1954 it was presented to the National Museum.

The disappearance of the original Scholfield carding machine is regrettable, but fortunately the Scholfields' importance to the American woolen industry does not depend on their having produced this one machine. These brothers, arriving here at a critical time in our nation's history, made important contributions to our economic and to our technological progress—John by his mill operations, Arthur by his ultimate work of constructing wool-carding machines for sale. Of these two aspects, it is the contribution of Arthur that has had the more far-reaching effect, for he spread his expert knowledge of mechanical wool carding, in the form of machines, throughout the New England woolen centers. His machines now stand as monuments to the work of both.

[1] The same type of hand cards were also used for cotton in Colonial America, but because the cotton fibers were not laid parallel in the sliver only coarse yarns could be spun. In ancient Peru the fibers for spinning fine cotton yarns were prepared with the fingers alone. In India the cotton fibers were combed with the fine-toothed jawbone of the boalee fish before the fibers were removed from the seed. (J.F. Watson, The textile manufactures and the costumes of the people of India, London, 1866, p. 64.)

[2] Edward Baines, History of the cotton manufacture in Great Britain, London, 1835, p. 176.

[3] The wire points of the worker roller pick up the fibers from the faster moving main cylinder, carding the fibers on contact. A stripping action takes place when the wires of the worker roller meet the points of the stripper roller in a "point to back" action. This arrangement is used to remove the wool from the worker and put it back on the wire teeth of the main cylinder. Illustrated in W. Van Bergen and H.R. Mauersberger, American wool handbook, New York, 1948, p. 451.

[4] The doffer comb, a serrated metal plate the length of the rollers, removes the carded fibers from the last roller or doffer.

[5] This was no great disadvantage at this time, as wool was still being spun on the spinning wheel. The mechanical spinning of woolen yarns was an obstinate problem that was not solved until 1815–1820. It then was necessary to piece these 24-inch slivers together before they could be spun until 1826, when a device for the doffing of carded wool in a continuous sliver was perfected by an American, John Goulding, and patented by him.

[6] A.P. Pitkin, The Pitkin family of America, Hartford, 1887, p. 75.

[7] From a letter written in 1889 by Mayall's son; A.H. Cole, The American wool manufacture, vol. 1, Cambridge, 1926, p. 90.

[8] From a report of the visit of Henry Wansey in 1794, cited by W.R. Bagnall, The textile industries of the United States, Cambridge, 1893, p. 107.

[9] Slater introduced the Arkwright system of carding and spinning cotton into America in 1790. Bringing neither plans nor models with him from which to build the machines, he relied instead on his detailed knowledge of their construction. England prohibited the export of textile machines, models, and plans, and even attempted to prevent skilled artisans from leaving the country. George S. White, Memoir of Samuel Slater, Philadelphia, 1836, pp. 37 and 71.

[10] R.C. Taft, Some notes upon the introduction of the woolen manufacture into the United States, Providence, 1882, pp. 17–18. The Scholfield sons, of whom three were still living in the 1880's, were quite elderly at the time Taft talked to them; only James, aged 98, would have been able to remember the Connecticut move.

[11] There is no record of the carding machine made of mahogany which John's sons reported had been transferred to the Stonington mill.

[12] This is probably the machine that gave rise to stories of a carding machine having been smuggled from England during the early Byfield days. J.E.A. Smith, The history of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, from the year 1800 to the year 1876, Springfield, 1876, p. 167.

[13] U.S. 15th Congress, 1st and 2nd sessions, The debates and proceedings in the Congress, vols. for 1817–1819 (2).

[14] Worcester Spy, July 10, 1822.

[15] A natural delay. Although the cylinders and the card clothing wore out and had to be replaced, the heavy wooden frames of the early machines remained long in serviceable condition.

[16] Once again in use, it is now powered by electricity. A pound of slivers from it (about 260) may be purchased for $3.00.

[17] The author is indebted to William N. Watkins, U.S. National Museum Curator of Agriculture and Wood Products, Smithsonian Institution, for the identification of the woods in the specimen.

[18] The author is indebted to Mr. Don Berkebile of the Smithsonian's U.S. National Museum staff for his examination of the metal teeth on the comb plate of this machine.