Japanese Prints

By John Gould Fletcher

Japanese Prints

Goblins and Pagodas

Irradiations: Sand and Spray

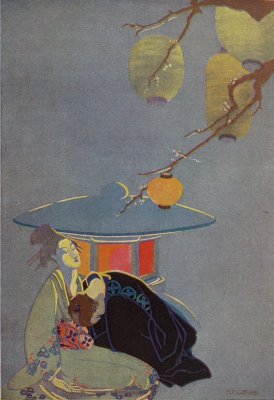

"Of what is she dreaming?

Of long nights lit with orange lanterns,

Of wine-cups and compliments and kisses of the two-sword men."

Japanese Prints

By

John Gould Fletcher

With Illustrations By

Dorothy Pulis Lathrop

Boston

The Four Seas Company

1918

Copyright, 1918, by

The Four Seas Company

The Four Seas Press

Boston, Mass., U.S.A.

To My Wife

Granted this dew-drop world be but a dew-drop world,

This granted, yet—

Table of Contents

| Preface | | 11 |

| Part I. |

| Lovers Embracing | 21 |

| A Picnic Under the Cherry Trees | 22 |

| Court Lady Standing Under Cherry Tree | 23 |

| Court Lady Standing Under a Plum Tree | 24 |

| A Beautiful Woman | 25 |

| A Reading | 26 |

| An Actor as a Dancing Girl | 27 |

| Josan No Miya | 28 |

| An Oiran and Her Kamuso | 29 |

| Two Ways Of Love | 30 |

| Kurenai-ye or "Red Picture" | 31 |

| A Woman Standing by a Gate with an Umbrella | 32 |

| Scene from a Drama | 33 |

| A Woman in Winter Costume | 34 |

| A Pedlar | 35 |

| Kiyonobu and Kiyomasu Contrasted | 36 |

| An Actor | 37 |

| Part II. |

| Memory and Forgetting | 41 |

| Pillar-Print, Masonobu | 42 |

| The Young Daimyo | 43 |

| Masonubu—Early | 44 |

| The Beautiful Geisha | 45 |

| A Young Girl | 46 |

| The Heavenly Poetesses | 47 |

| The Old Love and The New | 48 |

| Fugitive Thoughts | 49 |

| Disappointment | 50 |

| The Traitor | 51 |

| The Fop | 52 |

| Changing Love | 53 |

| In Exile | 54 |

| The True Conqueror | 55 |

| Spring Love | 56 |

| The Endless Lament | 57 |

| Toyonobu. Exile's Return | 58 |

| Wind and Chrysanthemum | 59 |

| The Endless Pilgrimage | 60 |

| Part III. |

| The Clouds | 63 |

| Two Ladies Contrasted | 64 |

| A Night Festival | 65 |

| Distant Coasts | 66 |

| On the Banks of the Sumida | 67 |

| Yoshiwara Festival | 68 |

| Sharaku Dreams | 69 |

| A Life | 70 |

| Dead Thoughts | 71 |

| A Comparison | 72 |

| Mutability | 73 |

| Despair | 74 |

| The Lonely Grave | 75 |

| Part IV. |

| Evening Sky | 79 |

| City Lights | 80 |

| Fugitive Beauty | 81 |

| Silver Jars | 82 |

| Evening Rain | 83 |

| Toy-Boxes | 84 |

| Moods | 85 |

| Grass | 86 |

| A Landscape | 87 |

| Terror | 88 |

| Mid-Summer Dusk | 89 |

| Evening Bell from a Distant Temple | 90 |

| A Thought | 91 |

| The Stars | 92 |

| Japan | 93 |

| Leaves | 94 |

List of Illustrations

"Of what is she dreaming?

Of long nights lit with orange lanterns,

Of wine-cups and compliments and kisses

of the two-sword men." | Frontispiece |

| Headpiece—Part I | 19 |

| Tailpiece—Part I | 37 |

| Headpiece—Part II | 39 |

"Out of the rings and the bubbles,

The curls and the swirls of the water,

Out of the crystalline shower of drops shattered in play,

Her body and her thoughts arose." | 46 |

"The cranes have come back to the temple,

The winds are flapping the flags about,

Through a flute of reeds

I will blow a song." | 58 |

| Tailpiece—Part II | 60 |

| Headpiece—Part III | 61 |

"Then in her heart they grew,

The snows of changeless winter,

Stirred by the bitter winds of unsatisfied desire." | 70 |

| Tailpiece—Part III | 75 |

| Headpiece—Part IV | 77 |

| Headpiece—Part IV | 94 |

"The green and violet peacocks

Through the golden dusk

Stately, nostalgically,

Parade." | Endleaf |

[11]

Preface

At the earliest period concerning which we have any accurate

information, about the sixth century A. D., Japanese poetry already

contained the germ of its later development. The poems of this early

date were composed of a first line of five syllables, followed by a

second of seven, followed by a third of five, and so on, always ending

with a line of seven syllables followed by another of equal number. Thus

the whole poem, of whatever length (a poem of as many as forty-nine

lines was scarce, even at that day) always was composed of an odd number

of lines, alternating in length of syllables from five to seven, until

the close, which was an extra seven syllable line. Other rules there

were none. Rhyme, quantity, accent, stress were disregarded. Two vowels

together must never be sounded as a diphthong, and a long vowel counts

for two syllables, likewise a final "n", and the consonant "m" in some

cases.

This method of writing poetry may seem to the reader to suffer from

serious disadvantages. In reality this was not the case. Contrast it for

a moment with the undignified welter of undigested and ex parte[12]

theories which academic prosodists have tried for three hundred years to

foist upon English verse, and it will be seen that the simple Japanese

rule has the merit of dignity. The only part of it that we Occidentals

could not accept perhaps, with advantage to ourselves, is the peculiarly

Oriental insistence on an odd number of syllables for every line and an

odd number of lines to every poem. To the Western mind, odd numbers

sound incomplete. But to the Chinese (and Japanese art is mainly a

highly-specialized expression of Chinese thought), the odd numbers are

masculine and hence heavenly; the even numbers feminine and hence

earthy. This idea in itself, the antiquity of which no man can tell,

deserves no less than a treatise be written on it. But the place for

that treatise is not here.

To return to our earliest Japanese form. Sooner or later this

crystallized into what is called a tanka or short ode. This was always

five lines in length, constructed syllabically 5, 7, 5, 7, 7, or

thirty-one syllables in all. Innumerable numbers of these tanka were

written. Gradually, during the feudal period, improvising verses became

a pastime in court circles. Some one would utter the first three lines

of a tanka and some one else would cap the composition by adding the

last two. This division persisted. The first hemistich which was

composed of 17 syllables grew to be called the hokku, the second or

finishing hemistich [13]of 14 syllables was called ageku. Thus was born the

form which is more peculiarly Japanese than any other, and which only

they have been able to carry to perfection.

Composing hokku might, however, have remained a mere game of elaborate

literary conceits and double meanings, but for the genius of one man.

This was the great Bashō (1644-1694) who may be called certainly the

greatest epigrammatist of any time. During a life of extreme and

voluntary self-denial and wandering, Bashō contrived to obtain over a

thousand disciples, and to found a school of hokku writing which has

persisted down to the present day. He reformed the hokku, by introducing

into everything he wrote a deep spiritual significance underlying the

words. He even went so far as to disregard upon occasion the syllabic

rule, and to add extraneous syllables, if thereby he might perfect his

statement. He set his face sternly against impromptus, poemes

d'occasion, and the like. The number of his works were not large, and

even these he perpetually sharpened and polished. His influence

persisted for long after his death. A disciple and priest of Zen

Buddhism himself, his work is permeated with the feeling of that

doctrine.

Zen Buddhism, as Bashō practised it, may be called religion under the

forms of nature. Everything on earth, from the clouds in the sky to the[14]

pebble by the roadside, has some spiritual or ethical significance for

us. Blake's words describe the aim of the Zen Buddhist as well as any

one's:

"To see a World in a grain of sand,

And a Heaven in a wild flower;

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,

And Eternity in an hour."

Bashō would have subscribed to this as the sole rule of poetry and

imagination. The only difference between the Western and the Eastern

mystic is that where one sees the world in the grain of sand and tells

you all about it, the other sees and lets his silence imply that he

knows its meaning. Or to quote Lao-tzu: "Those who speak do not know,

those who know do not speak." It must always be understood that there is

an implied continuation to every Japanese hokku. The concluding

hemistich, whereby the hokku becomes the tanka, is existent in the

writer's mind, but never uttered.

Let us take an example. The most famous hokku that Bashō wrote, might

be literally translated thus:

"An old pond

And the sound of a frog leaping

Into the water."

This means nothing to the Western mind. But to the Japanese it means all

the beauty of such a life of retirement and contemplation as Bashō

practised. If we permit our minds to supply the detail Bashō

deliberately [15]omitted, we see the mouldering temple enclosure, the sage

himself in meditation, the ancient piece of water, and the sound of a

frog's leap—passing vanity—slipping into the silence of eternity. The

poem has three meanings. First it is a statement of fact. Second, it is

an emotion deduced from that. Third, it is a sort of spiritual allegory.

And all this Bashō has given us in his seventeen syllables.

All of Bashō's poems have these three meanings. Again and again we

get a sublime suggestion out of some quite commonplace natural fact. For

instance:

"On the mountain-road

There is no flower more beautiful

Than the wild violet."

The wild violet, scentless, growing hidden and neglected among the rocks

of the mountain-road, suggested to Bashō the life of the Buddhist

hermit, and thus this poem becomes an exhortation to "shun the world, if

you would be sublime."

I need not give further examples. The reader can now see for himself

what the main object of the hokku poetry is, and what it achieved. Its

object was some universalized emotion derived from a natural fact. Its

achievement was the expression of that emotion in the fewest possible

terms. It is therefore necessary, if poetry in the English tongue is

ever to attain again to the vitality and strength of its beginnings,

that we sit once more at the feet of the[16] Orient and learn from it how

little words can express, how sparingly they should be used, and how

much is contained in the meanest natural object. Shakespeare, who could

close a scene of brooding terror with the words: "But see, the morn in

russet mantle clad, Walks o'er the dew of yon high eastern hill" was

nearer to the oriental spirit than we are. We have lost Shakespeare's

instinct for nature and for fresh individual vision, and we are

unwilling to acquire it through self-discipline. If we do not want art

to disappear under the froth of shallow egotism, we must learn the

lesson Bashō can teach us.

That is not to say, that, by taking the letter for the spirit, we should

in any way strive to imitate the hokku form. Good hokkus cannot be

written in English. The thing we have to follow is not a form, but a

spirit. Let us universalize our emotions as much as possible, let us

become impersonal as Shakespeare or Bashō was. Let us not gush about

our fine feelings. Let us admit that the highest and noblest feelings

are things that cannot be put into words. Therefore let us conceal them

behind the words we have chosen. Our definition of poetry would then

become that of Edwin Arlington Robinson, that poetry is a language which

tells through a reaction upon our emotional natures something which

cannot be put into words. Unless we set ourselves seriously to the task

of understanding that language is only a means and never an[17] end, poetic

art will be dead in fifty years, from a surfeit of superficial

cleverness and devitalized realism.

In the poems that follow I have taken as my subjects certain designs of

the so-called Uki-oye (or Passing World) school. These prints, made and

produced for purely popular consumption by artists who, whatever their

genius, were despised by the literati of their time, share at least one

characteristic with Japanese poetry, which is, that they exalt the most

trivial and commonplace subjects into the universal significance of

works of art. And therefore I have chosen them to illustrate my

doctrine, which is this: that one must learn to do well small things

before doing things great; that the universe is just as much in the

shape of a hand as it is in armies, politics, astronomy, or the

exhortations of gospel-mongers; that style and technique rest on the

thing conveyed and not the means of conveyance; and that though

sentiment is a good thing, understanding is a better. As for the poems

themselves they are in some cases not Japanese at all, but all

illustrate something of the charm I have found in Japanese poetry and

art. And if they induce others to seek that charm for themselves, my

purpose will have been attained.

John Gould Fletcher.[18]

[19]

[20]

Part I

[21]

Lovers Embracing

Force and yielding meet together:

An attack is half repulsed.

Shafts of broken sunlight dissolving

Convolutions of torpid cloud.

[22]

A Picnic Under the Cherry Trees

The boat drifts to rest

Under the outward spraying branches.

There is faint sound of quavering strings,

The reedy murmurs of a flute,

The soft sigh of the wind through silken garments;

All these are mingled

With the breeze that drifts away,

Filled with thin petals of cherry blossom,

Like tinkling laughter dancing away in sunlight.

[23]

Court Lady Standing Under Cherry Tree

She is an iris,

Dark purple, pale rose,

Under the gnarled boughs

That shatter their stars of bloom.

She waves delicately

With the movement of the tree.

Of what is she dreaming?

Of long nights lit with orange lanterns,

Of wine cups and compliments and kisses of the two-sword men.

And of dawn when weary sleepers

Lie outstretched on the mats of the palace,

And of the iris stalk that is broken in the fountain.

[24]

Court Lady Standing Under a Plum Tree

Autumn winds roll through the dry leaves

On her garments;

Autumn birds shiver

Athwart star-hung skies.

Under the blossoming plum-tree,

She expresses the pilgrimage

Of grey souls passing,

Athwart love's scarlet maples

To the ash-strewn summit of death.

[25]

A Beautiful Woman

Iris-amid-clouds

Must be her name.

Tall and lonely as the mountain-iris,

Cold and distant.

She has never known longing:

Many have died for love of her.

[26]

A Reading

"And the prince came to the craggy rock

But saw only hissing waves

So he rested all day amid them."

He listens idly,

He is content with her voice.

He dreams it is the murmur

Of distant wave-caps breaking

Upon the painted screen.

[27]

An Actor as a Dancing Girl

The peony dancer

Swirls orange folds of dusty robes

Through the summer.

They are spotted with thunder showers,

Falling upon the crimson petals.

Heavy blooms

Breaking and spilling fiery cups

Drowsily.

[28]

Josan No Miya

She is a fierce kitten leaping in sunlight

Towards the swaying boughs.

She is a gust of wind,

Bending in parallel curves the boughs of the willow-tree.

[29]

An Oiran and her Kamuso

Gilded hummingbirds are whizzing

Through the palace garden,

Deceived by the jade petals

Of the Emperor's jewel-trees.

[30]

Two Ways of Love

The wind half blows her robes,

That subside

Listlessly

As swaying pines.

The wind tosses hers

In circles

That recoil upon themselves:

How should I love—as the swaying or tossing wind?

[31]

Kurenai-ye or "Red Picture"

She glances expectantly

Through the pine avenue,

To the cherry-tree summit

Where her lover will appear.

Faint rose anticipation colours her,

And sunset;

She is a cherry-tree that has taken long to bloom.

[32]

A Woman Standing by a Gate with an Umbrella

Late summer changes to autumn:

Chrysanthemums are scattered

Behind the palings.

Gold and vermilion

The afternoon.

I wait here dreaming of vermilion sunsets:

In my heart is a half fear of the chill autumn rain.

[33]

Scene from a Drama

The daimyo and the courtesan

Compliment each other.

He invites her to walk out through the maples,

She half refuses, hiding fear in her heart.

Far in the shadow

The daimyo's attendant waits,

Nervously fingering his sword.

[34]

A Woman in Winter Costume

She is like the great rains

That fall over the earth in winter-time.

Wave on wave her heavy robes collapse

In green torrents

Lashed with slaty foam.

Downward the sun strikes amid them

And enkindles a lone flower;

A violet iris standing yet in seething pools of grey.

[35]

A Pedlar

Gaily he offers

Packets of merchandise.

He is a harlequin of illusions,

His nimble features

Skip into smiles, like rainbows,

Cheating the villagers.

But in his heart all the while is another knowledge,

The sorrow of the bleakness of the long wet winter night.

[36]

Kiyonobu and Kiyomasu Contrasted

One life is a long summer;

Tall hollyhocks stand proud upon its paths;

Little yellow waves of sunlight,

Bring scarlet butterflies.

Another life is a brief autumn,

Fierce storm-rack scrawled with lightning

Passed over it

Leaving the naked bleeding earth,

Stabbed with the swords of the rain.

[37]

An Actor

He plots for he is angry,

He sneers for he is bold.

He clinches his fist

Like a twisted snake;

Coiling itself, preparing to raise its head,

Above the long grasses of the plain.

[38]

[39]

Part II

[40]

[41]

Memory and Forgetting

I have forgotten how many times he kissed me,

But I cannot forget

A swaying branch—a leaf that fell

To earth.

[42]

Pillar-Print, Masonobu

He stands irresolute

Cloaking the light of his lantern.

Tonight he will either find new love or a sword-thrust,

But his soul is troubled with ghosts of old regret.

Like vines with crimson flowers

They climb

Upwards

Into his heart.

[43]

The Young Daimyo

When he first came out to meet me,

He had just been girt with the two swords;

And I found he was far more interested in the glitter of their hilts,

And did not even compare my kiss to a cherry-blossom.

[44]

Masonubu—Early

She was a dream of moons, of fluttering handkerchiefs,

Of flying leaves, of parasols,

A riddle made to break my heart;

The lightest impulse

To her was more dear than the deep-toned temple bell.

She fluttered to my sword-hilt an instant,

And then flew away;

But who will spend all day chasing a butterfly?

[45]

The Beautiful Geisha

Swift waves hissing

Under the moonlight;

Tarnished silver.

Swaying boats

Under the moonlight,

Gold lacquered prows.

Is it a vision

Under the moonlight?

No, it is only

A beautiful geisha swaying down the street.

[46]

A Young Girl

Out of the rings and the bubbles,

The curls and the swirls of the water,

Out of the crystalline shower of drops shattered in play,

Her body and her thoughts arose.

She dreamed of some lover

To whom she might offer her body

Fresh and cool as a flower born in the rain.

[47]

The Heavenly Poetesses

In their bark of bamboo reeds

The heavenly poetesses

Float across the sky.

Poems are falling from them

Swift as the wind that shakes the lance-like bamboo leaves;

The stars close around like bubbles

Stirred by the silver oars of poems passing.

[48]

The Old Love and the New

Beware, for the dying vine can hold

The strongest oak.

Only by cutting at the root

Can love be altered.

Late in the night

A rosy glimmer yet defies the darkness.

But the evening is growing late,

The blinds are being lowered;

She who held your heart and charmed you

Is only a rosy glimmer of flame remembered.

[49]

Fugitive Thoughts

My thoughts are sparrows passing

Through one great wave that breaks

In bubbles of gold on a black motionless rock.

[50]

Disappointment

Rain rattles on the pavement,

Puddles stand in the bluish stones;

Afar in the Yoshiwara

Is she who holds my heart.

Alas, the torn lantern of my hope

Trembles and sputters in the rain.

[51]

The Traitor

I saw him pass at twilight;

He was a dark cloud travelling

Over palace roofs

With one claw drooping.

In his face were written ages

Of patient treachery

And the knowledge of his hour.

One dainty thrust, no more

Than this, he needs.

[52]

The Fop

His heart is like a wind

Torn between cloud and butterfly;

Whether he will roll passively to one,

Or chase endlessly the other.

[53]

Changing Love

My love for her at first was like the smoke that drifts

Across the marshes

From burning woods.

But, after she had gone,

It was like the lotus that lifts up

Its heart shaped buds from the dim waters.

[54]

In Exile

My heart is mournful as thunder moving

Through distant hills

Late on a long still night of autumn.

My heart is broken and mournful

As rain heard beating

Far off in the distance

While earth is parched more near.

On my heart is the black badge of exile;

I droop over it,

I accept its shame.

[55]

The True Conqueror

He only can bow to men

Lofty as a god

To those beneath him,

Who has taken sins and sorrows

And whose deathless spirit leaps

Beneath them like a golden carp in the torrent.

[56]

Spring Love

Through the weak spring rains

Two lovers walk together,

Holding together the parasol.

But the laughing rains of spring

Will break the weak green shoots of their love.

His will grow a towering stalk,

Hers, a cowering flower under it.

[57]

The Endless Lament

Spring rain falls through the cherry blossom,

In long blue shafts

On grasses strewn with delicate stars.

The summer rain sifts through the drooping willow,

Shatters the courtyard

Leaving grey pools.

The autumn rain drives through the maples

Scarlet threads of sorrow,

Towards the snowy earth.

Would that the rains of all the winters

Might wash away my grief!

[58]

Toyonobu. Exile's Return

The cranes have come back to the temple,

The winds are flapping the flags about,

Through a flute of reeds

I will blow a song.

Let my song sigh as the breeze through the cryptomerias,

And pause like long flags flapping,

And dart and flutter aloft, like a wind-bewildered crane.

[59]

Wind and Chrysanthemum

Chrysanthemums bending

Before the wind.

Chrysanthemums wavering

In the black choked grasses.

The wind frowns at them,

He tears off a green and orange stalk of broken chrysanthemum.

The chrysanthemums spread their flattered heads,

And scurry off before the wind.

[60]

The Endless Pilgrimage

Storm-birds of autumn

With draggled wings:

Sleet-beaten, wind-tattered, snow-frozen,

Stopping in sheer weariness

Between the gnarled red pine trees

Twisted in doubt and despair;

Whence do you come, pilgrims,

Over what snow fields?

To what southern province

Hidden behind dim peaks, would you go?

"Too long were the telling

Wherefore we set out;

And where we will find rest

Only the Gods may tell."

[61]

[62]

Part III

[63]

The Clouds

Although there was no sound in all the house,

I could not forbear listening for the cry of those long white rippling waves

Dragging up their strength to break on the sullen beach of the sky.

[64]

Two Ladies Contrasted

The harmonies of the robes of this gay lady

Are like chants within a temple sweeping outwards

To the morn.

But I prefer the song of the wind by a stream

Where a shy lily half hides itself in the grasses;

To the night of clouds and stars and wine and passion,

In a palace of tesselated restraint and splendor.

[65]

A Night Festival

Sparrows and tame magpies chatter

In the porticoes

Lit with many a lantern.

There is idle song,

Scandal over full wine cups,

Sorrow does not matter.

Only beyond the still grey shoji

For the breadth of innumerable countries,

Is the sea with ships asleep

In the blue-black starless night.

[66]

Distant Coasts

A squall has struck the sea afar off.

You can feel it quiver

Over the paper parasol

With which she shields her face;

In the drawn-together skirts of her robes,

As she turns to meet it.

[67]

On the Banks of the Sumida

Windy evening of autumn,

By the grey-green swirling river,

People are resting like still boats

Tugging uneasily at their cramped chains.

Some are moving slowly

Like the easy winds:

Brown-blue, dull-green, the villages in the distance

Sleep on the banks of the river:

The waters sullenly clash and murmur.

The chatter of the passersby,

Is dulled beneath the grey unquiet sky.

[68]

Yoshiwara Festival

The green and violet peacocks

With golden tails

Parade.

Beneath the fluttering jangling streamers

They walk

Violet and gold.

The green and violet peacocks

Through the golden dusk

Showered upon them from the vine-hung lanterns,

Stately, nostalgically,

Parade.

[69]

Sharaku Dreams

I will scrawl on the walls of the night

Faces.

Leering, sneering, scowling, threatening faces;

Weeping, twisting, yelling, howling faces;

Faces fixed in a contortion between a scream and a laugh,

Meaningless faces.

I will cover the walls of night

With faces,

Till you do not know

If these faces are but masks, or you the masks for them.

Faces too grotesque for laughter,

Faces too shattered by pain for tears,

Faces of such ugliness

That the ugliness grows beauty.

They will haunt you morning, evening,

Burning, burning, ever returning.

Their own infamy creating,

Till you strike at life and hate it,

Burn your soul up so in hating.

I will scrawl on the walls of the night

Faces,

Pitiless,

Flaring,

Staring.

[70]

A Life

Her life was like a swiftly rushing stream

Green and scarlet,

Falling into darkness.

The seasons passed for her,

Like pale iris wilting,

Or peonies flying to ribbons before the storm-gusts.

The sombre pine-tops waited until the seasons had passed.

Then in her heart they grew

The snows of changeless winter

Stirred by the bitter winds of unsatisfied desire.

[71]

Dead Thoughts

My thoughts are an autumn breeze

Lifting and hurrying

Dry rubbish about in a corner.

My thoughts are willow branches

Already broken

Motionless at twilight.

[72]

A Comparison

My beloved is like blue smoke that rises

In long slow planes,

And wavers

Over the dark paths of old gardens long neglected.

[73]

Mutability

The wind shakes the mists

Making them quiver

With faint drum-tones of thunder.

Out of the crane-haunted mists of autumn,

Blue and brown

Rolls the moon.

There was a city living here long ago,

Of all that city

There is only one stone left half-buried in the marsh,

With characters upon it which no one now can read.

[74]

Despair

Despair hangs in the broken folds of my garments;

It clogs my footsteps,

Like snow in the cherry bloom.

In my heart is the sorrow

Of years like red leaves buried in snow.

[75]

The Lonely Grave

Pilgrims will ascend the road in early summer,

Passing my tombstone

Mossy, long forgotten.

Girls will laugh and scatter cherry petals,

Sometimes they will rest in the twisted pine-trees' shade.

If one presses her warm lips to this tablet

The dust of my body will feel a thrill, deep down in the silent earth.

[76]

[77]

Part IV

[78]

[79]

Evening Sky

The sky spreads out its poor array

Of tattered flags,

Saffron and rose

Over the weary huddle of housetops

Smoking their evening pipes in silence.

[80]

City Lights

The city gleams with lights this evening

Like loud and yawning laughter from red lips.

[81]

Fugitive Beauty

As the fish that leaps from the river,

As the dropping of a November leaf at twilight,

As the faint flicker of lightning down the southern sky,

So I saw beauty, far away.

[82]

Silver Jars

I dreamed I caught your loveliness

In little silver jars:

And when you died I opened them,

And there was only soot within.

[83]

Evening Rain

Rain fell so softly, in the evening,

I almost thought it was the trees that were talking.

[84]

Toy-Boxes

Cities are the toy-boxes

Time plays with:

And there are often many doll-houses

Of which the dolls are lost.

[85]

Moods

A poet's moods:

Fluttering butterflies in the rain.

[86]

Grass

Grass moves in the wind,

My soul is backwards blown.

[87]

A Landscape

Land, green-brown;

Sea, brown-grey;

Island, dull peacock blue;

Sky, stone-grey.

[88]

Terror

Because of the long pallid petals of white chrysanthemums

Waving to and fro,

I dare not go.

[89]

Mid-Summer Dusk

Swallows twittering at twilight:

Waves of heat

Churned to flames by the sun.

[90]

Evening Bell from a Distant Temple

A bell in the fog

Creeps out echoing faintly

The pale broad flashes

Of vibrating twilight,

Faded gold.

[91]

A Thought

A piece of paper ready to toss in the fire,

Blackened, scrawled with fragments of an incomplete song:

My soul.

[92]

The Stars

There is a goddess who walks shrouded by day:

At night she throws her blue veil over the earth.

Men only see her naked glory through the little holes in the veil.

[93]

Japan

An old courtyard

Hidden away

In the afternoon.

Grey walks,

Mossy stones,

Copper carp swimming lazily,

And beyond,

A faint toneless hissing echo of rain

That tears at my heart.

[94]

Leaves

The splaying silhouette of horse-chestnut leaves

Against the tall and delicate, patrician-tinged sky

Like a princess in blue robes behind a grille of bronze.

[95]

[96]

An edition of 1000 copies only, of which 975 copies have been printed

on Olde Style paper, and 25 copies on Japanese Vellum.