|

Transcriber's note:

|

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek or Hebrew will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Volume and page numbers are displayed in

the margin as: v.03 p.0001

|

THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

A DICTIONARY OF ARTS, SCIENCES, LITERATURE AND GENERAL INFORMATION

ELEVENTH EDITION

VOLUME III

AUSTRIA LOWER to BISECTRIX

[E-Text Edition of Volume III - Part 1 of 2, Slice 1 of 3 - AUSTRIA LOWER to BACON]

INITIALS USED IN VOLUME III. TO IDENTIFY INDIVIDUAL

CONTRIBUTORS,[1] WITH THE HEADINGS OF THE

ARTICLES IN THIS VOLUME SO SIGNED.

|

A. C. P.

|

Anna C. Paues, Ph.D.

Lecturer in Germanic Philology at Newnham College, Cambridge.

Formerly Fellow of Newnham College. Author of A Fourteenth Century

Biblical Version; &c.

|

Bible, English.

|

|

A. C. S.

|

Algernon Charles Swinburne.

See biographical article: Swinburne, Algernon

C.

|

Beaumont and Fletcher.

|

|

A. F. P.

|

Albert Frederick Pollard, M.A.,

F.R.Hist.Soc.

Professor of English History in the University of London. Fellow of

All Souls' College, Oxford. Assistant Editor of the Dictionary of

National Biography, 1893-1901. Lothian prizeman (Oxford), 1892;

Arnold prizeman, 1898. Author of England under the Protector

Somerset; Henry VIII.; Life of Thomas Cranmer;

&c.

|

Balnaves; Barnes, Robert; Bilney.

|

|

A. Go.*

|

Rev. Alexander Gordon, M.A.

Lecturer on Church History in the University of Manchester.

|

Beza.

|

|

A. G. G.

|

Sir Alfred George Greenhill, M.A.,

F.R.S.

Formerly Professor of Mathematics in the Ordnance College, Woolwich.

Author of Differential and Integral Calculus with

Applications; Hydrostatics; Notes on Dynamics;

&c.

|

Ballistics.

|

|

A. Hl.

|

Arthur Hassall, M.A.

Student and Tutor of Christ Church, Oxford. Author of A Handbook

of European History; The Balance of Power; &c. Editor

of the 3rd edition of T. H. Dyer's History of Modern

Europe.

|

Austria-Hungary: History (in part).

|

|

A. H. N.

|

Albert Henry Newman, LL.D., D.D.

Professor of Church History, Baylor University, Texas. Professor at

McMaster University, Toronto, 1881-1901. Author of The Baptist

Churches in the United States; Manual of Church History;

A Century of Baptist Achievement.

|

Baptists: American.

|

|

A. H.-S.

|

Sir A. Houtum-Schindler, C.I.E.

General in the Persian Army. Author of Eastern Persian

Irak.

|

Azerbāijān; Bakhtiari; Bander Abbāsi;

Barfurush.

|

|

A. H. S.

|

Rev. Archibald Henry Sayce, D.Litt.,

LL.D.

See the biographical article: SAYCE, A. H.

|

Babylon; Babylonia and Assyria; Belshazzar; Berossus.

|

|

A. J. L.

|

Andrew Jackson Lamoureux.

Librarian, College of Agriculture, Cornell University. Editor of the

Rio News (Rio de Janeiro), 1879-1901.

|

Bahia: State; Bahia: City.

|

|

A. L.

|

Andrew Lang.

See the biographical article: Lang,

Andrew.

|

Ballads.

|

|

A. N.

|

Alfred Newton, F.R.S.

See the biographical article: Newton,

Alfred.

|

Birds of Paradise.

|

|

A. P. H.

|

Alfred Peter Hillier, M.D., M.P.

President, South African Medical Congress, 1893. Author of South

African Studies; &c. Served in Kaffir War, 1878-1879. Partner

with Dr L. S. Jameson in medical practice in South Africa till 1896.

Member of Reform Committee, Johannesburg, and Political Prisoner at

Pretoria, 1895-1896. M.P. for Hitchin division of Herts, 1910.

|

Basutoland: History (in part); Bechuanaland

(in part).

|

|

A. Sp.

|

Archibald Sharp.

Consulting Engineer and Chartered Patent Agent.

|

Bicycle.

|

|

A. St H. G.

|

Alfred St Hill Gibbons.

Major, East Yorkshire Regiment. Explorer in South Central Africa.

Author of Africa from South to North through Marotseland.

|

Barotse, Barotseland.

|

|

A. W.*

|

Arthur Willey, F.R.S., D.Sc.

Director of Colombo Museum, Ceylon.

|

Balanoglossus.

|

|

A. W. H.*

|

Arthur William Holland.

Formerly Scholar of St John's College, Oxford. Bacon Scholar of

Gray's Inn, 1900.

|

Austria-Hungary: History (in part); Bavaria:

History (in part).

|

|

A. W. Po.

|

Alfred William Pollard, M.A.

Assistant Keeper of Printed Books, British Museum. Fellow of King's

College, London. Hon. Secretary Bibliographical Society. Editor of

Books about Books; and Bibliographica. Joint-editor of

the Library. Chief Editor of the "Globe" Chaucer.

|

Bibliography and Bibliology.

|

|

B. K.

|

Prince Bojidar Karageorgevitch (d.

1908).

Artist, art critic, designer and goldsmith. Contributor to the Paris

Figaro, the Magazine of Art, &c. Author of

Enchanted India. Translator of the works of Tolstoi and Jokai,

&c.

|

Bashkirtseff.

|

|

C.

|

The Earl of Crewe, K.G., F.S.A.

See the biographical article: Crewe, 1st Earl

of.

|

Banville.

|

|

C. A. C.

|

Charles Arthur Conant.

Member of Commission on International Exchange of U.S., 1903.

Treasurer, Morton Trust Co., New York, 1902-1906. Author of

History of Modern Banks of Issue; The Principles of Money

and Banking; &c.

|

Banks and Banking: American.

|

|

C. B.*

|

Charles Bémont, D. ès L., Litt.D.

(Oxon.).

See the biographical article: Bémont, C.

|

Baluze; Béarn.

|

|

C. F. A.

|

Charles Francis Atkinson.

Formerly Scholar of Queen's College, Oxford. Captain, 1st City of

London (Royal Fusiliers). Author of The Wilderness and Cold

Harbour.

|

Austrian Succession War: Military.

|

|

C. F. B.

|

Charles Francis Bastable, M.A., LL.D.

Regius Professor of Laws and Professor of Political Economy in the

University of Dublin. Author of Public Finance; Commerce of

Nations; Theory of International Trade; &c.

|

Bimetallism.

|

|

C. H. T.

|

Cuthbert Hamilton Turner, M.A.

Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford; Fellow of the British Academy.

Speaker's Lecturer in Biblical Studies in the University of Oxford,

1906-1909. First Editor of the Journal of Theological Studies,

1899-1902. Author of "Chronology of the New Testament," and "Greek

Patristic Commentaries on the Pauline Epistles" in Hastings'

Dictionary of the Bible, &c.

|

Bible: New Testament Chronology.

|

|

C. H. W. J.

|

Rev. Claude Hermann Walter Johns, M.A.,

Litt.D.

Master of St Catharine's College, Cambridge. Lecturer in Assyriology,

Queens' College, Cambridge, and King's College, London. Author of

Assyrian Deeds and Documents of the 7th Century B.C.; The Oldest Code of Laws;

Babylonian and Assyrian Laws; Contracts and Letters;

&c.

|

Babylonian Law.

|

|

C. J. L.

|

Sir Charles James Lyall, K.C.S.I., C.I.E.,

LL.D. (Edin.).

Secretary, Judicial and Public Department, India Office. Fellow of

King's College, London. Secretary to Government of India in Home

Department, 1889-1894. Chief Commissioner, Central Provinces, India,

1895-1898. Author of Translations of Ancient Arabic Poetry;

&c.

|

Bihārī Lāl.

|

|

C. Mi.

|

Chedomille Mijatovich.

Senator of the Kingdom of Servia. Envoy Extraordinary and Minister

Plenipotentiary of the King of Servia to the Court of St James's,

1895-1900, and 1902-1903.

|

Belgrade.

|

|

C. Pl.

|

Rev. Charles Plummer, M.A.

Fellow and Chaplain of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Ford's

Lecturer, 1901. Author of Life and Times of Alfred the Great;

&c.

|

Bede.

|

|

C. R. B.

|

Charles Raymond Beazley, M.A., D.Litt., F.R.G.S.,

F.R.Hist.S.

Professor of Modern History in the University of Birmingham. Formerly

Fellow of Merton College, Oxford, and University Lecturer in the

History of Geography. Lothian prizeman (Oxford), 1889. Lowell

Lecturer, Boston, 1908. Author of Henry the Navigator; The

Dawn of Modern Geography; &c.

|

Beatus; Behaim.

|

|

C. W. W.

|

Sir Charles William Wilson, K.C.B., K.C.M.G.,

F.R.S. (1836-1907).

Major-General, Royal Engineers. Secretary to the North American

Boundary Commission, 1858-1862. British Commissioner on the Servian

Boundary Commission. Director-General of the Ordnance Survey,

1886-1894. Director-General of Military Education, 1895-1898. Author

of From Korti to Khartoum; Life of Lord Clive;

&c.

|

Beirut (in part)

|

|

D. B. Ma.

|

Duncan Black Macdonald, D.D.

Professor of Semitic Languages, Hartford Theological Seminary,

U.S.A.

|

Bairam

|

|

D. C. B.

|

Demetrius Charles Boulger.

Author of England and Russia in Central Asia; History of

China; Life of Gordon; India in the 19th Century;

History of Belgium; Belgian Life in Town and Country;

&c.

|

Belgium: Geography and Statistics.

|

|

D. F. T.

|

Donald Francis Tovey.

Balliol College, Oxford. Author of Essays in Musical

Analysis—comprising The Classical Concerto, The

Goldberg Variations, and analyses of many other classical

works.

|

Bach, J. S.; Beethoven.

|

|

D. G. H.

|

David George Hogarth, M.A.

Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Fellow of Magdalen College,

Oxford. Fellow of the British Academy. Excavated at Paphos, 1888;

Naukratis, 1899 and 1903; Ephesus, 1904-1905; Assiut, 1906-1907.

Director, British School at Athens, 1897-1900; Director, Cretan

Exploration Fund, 1899.

|

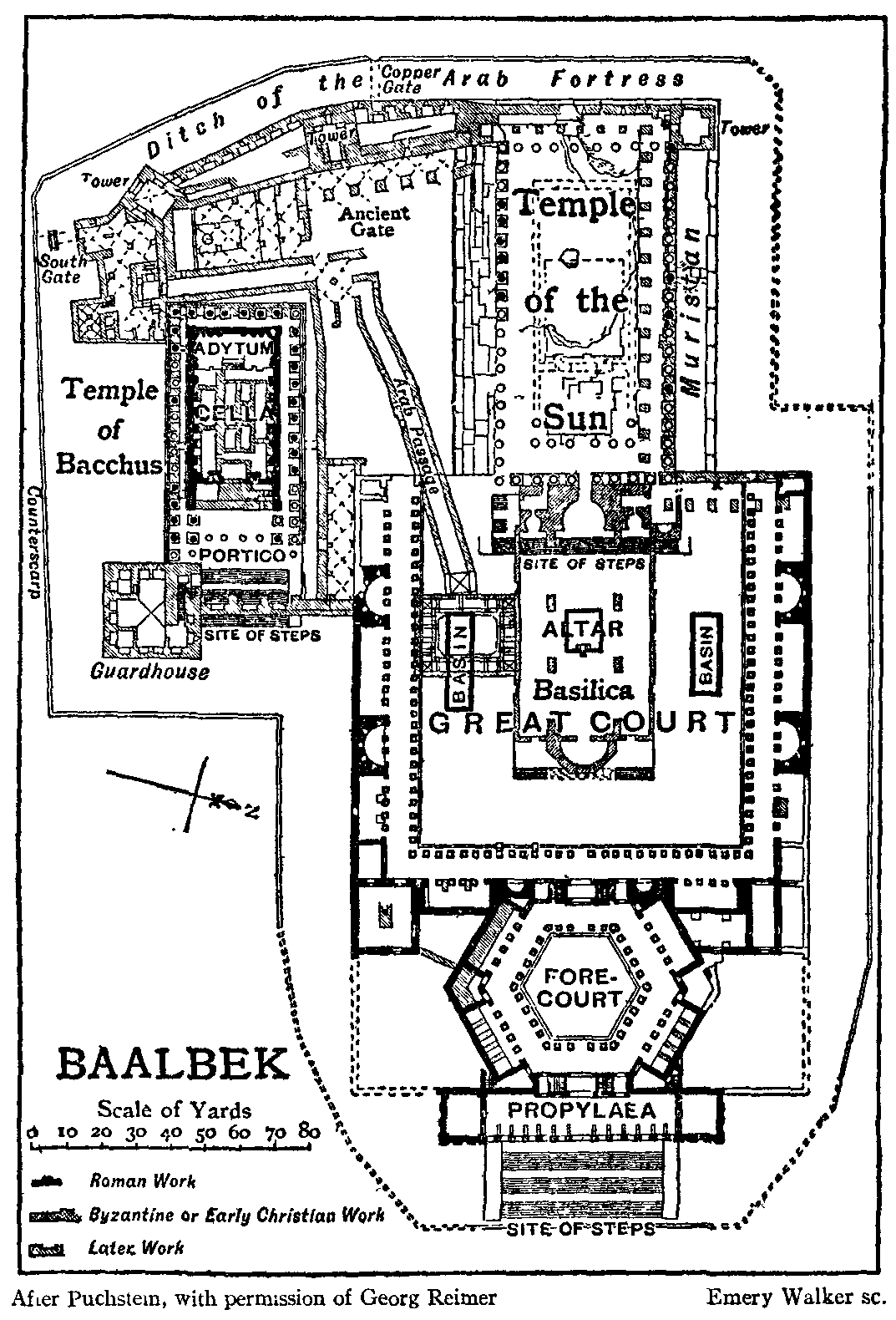

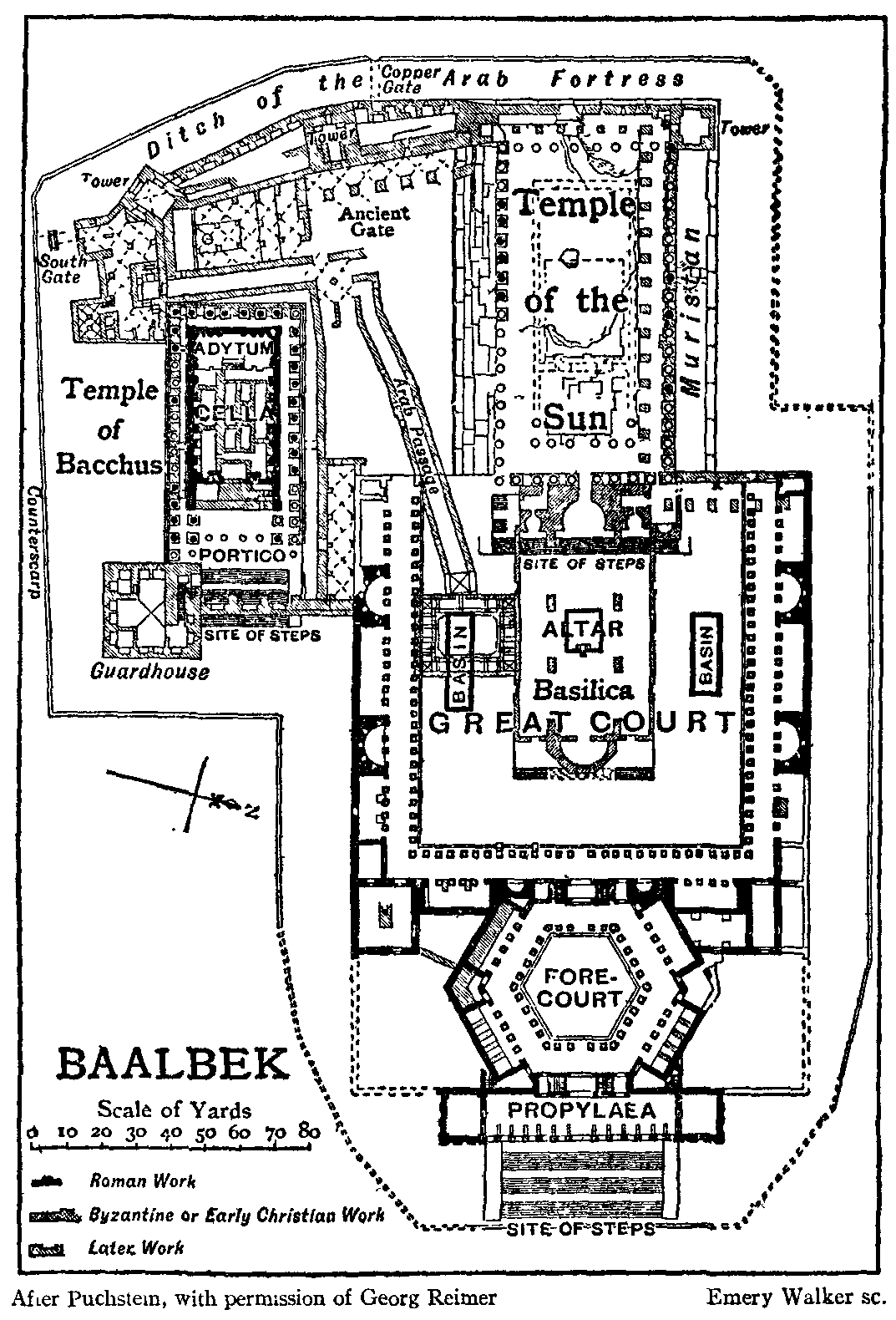

Baalbek; Barca; Beirut (in part); Bengazi.

|

|

D. H.

|

David Hannay.

Formerly British Vice-Consul at Barcelona. Author of Short History

of Royal Navy, 1217-1688; Life of Emilio Castelar;

&c.

|

Austrian Succession War: Naval; Avilés; Bainbridge,

William; Barbary Pirates.

|

|

D. Mn.

|

Rev. Dugald Macfadyen, M.A.

Minister of South Grove Congregational Church, Highgate. Director of

the London Missionary Society.

|

Berry, Charles Albert.

|

|

D. S. M.*

|

David Samuel Margoliouth, M.A., D.Litt.

Laudian Professor of Arabic, Oxford; Fellow of New College. Author of

Arabic Papyri of the Bodleian Library; Mohammed and the

Rise of Islam; Cairo, Jerusalem and Damascus.

|

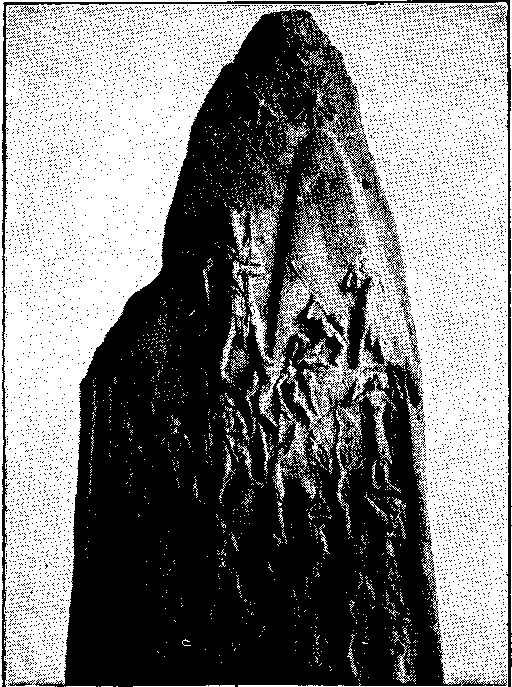

Axum.

|

|

D. S.-S.

|

David Seth-Smith, F.Z.S.

Curator of Birds to the Zoological Society of London. Formerly

President of the Avicultural Society. Author of Parrakeets, a

Practical Handbook to those Species kept in Captivity.

|

Aviary.

|

|

E. B.

|

Edward Breck, Ph.D.

Formerly Foreign Correspondent of the New York Herald and the

New York Times. Author of Wilderness Pets.

|

Base-Ball.

|

|

E. Br.

|

Ernest Barker, M.A.

Fellow and Lecturer of St John's College, Oxford. Formerly Fellow and

Tutor of Merton College. Craven Scholar (Oxford), 1895.

|

Baldwin I. to IV. of Jerusalem.

|

|

E. Cl.

|

Edward Clodd.

Vice-President of the Folk-Lore Society. Author of Story of

Primitive Man; Primer of Evolution; Tom Tit Tot;

Animism; Pioneers of Evolution.

|

Baer.

|

|

E. C. B.

|

Right Rev. Edward Cuthbert Butler, O.S.B.,

D.Litt. (Dubl.).

Abbot of Downside Abbey, Bath.

|

Basilian Monks; Benedict of Nursia; Benedictines; St Bernardin

of Siena.

|

|

E. F. S.

|

Edward Fairbrother Strange.

Assistant-Keeper, Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington.

Member of Council, Japan Society. Author of numerous works on art

subjects; Joint-editor of Bell's "Cathedral" Series.

|

Beardsley, Aubrey Vincent.

|

|

E. G.

|

Edmund Gosse, LL.D.

See the biographical article: Gosse,

Edmund.

|

Baggesen; Ballade; Barnfield; Beaumont, Sir John; Belgium:

Literature; Biography.

|

|

E. G. B.

|

Edward Granville Browne, M.A., M.R.C.S.,

M.R.A.S.

Sir Thomas Adams's Professor of Arabic and Fellow of Pembroke

College, Cambridge. Fellow of the British Academy. Author of A

Traveller's Narrative, written to Illustrate the Episode of the

Báb; The New History of Mirzá Ali Muhammed the Báb;

Literary History of Persia; &c.

|

Bábiism.

|

|

E. H. M.

|

Ellis Hovell Minns, M.A.

Lecturer and Assistant Librarian, and formerly Fellow of Pembroke

College, Cambridge. University Lecturer in Palaeography.

|

Bastarnae.

|

|

Ed. M.

|

Eduard Meyer, D.Litt. (Oxon.), LL.D., Ph.D.

Professor of Ancient History in the University of Berlin. Author of

Geschichte des Alterthums; Geschichte des alten

Ägyptens; Die Israeliten und ihre Nachbarstamme;

&c.

|

Bactria; Bagoas; Bahran; Balash; Behistun.

|

|

E. Ma.

|

Edward Manson.

Barrister-at-Law. Joint-editor of Journal of Comparative

Legislation, Author of Short View of the Law of

Bankruptcy; &c.

|

Bankruptcy: Comparative Law

|

|

E. M. T.

|

Sir Edward Maunde Thompson, G.C.B., D.C.L.,

LL.D., Litt.D.

Director and Principal Librarian, British Museum, 1888-1909. Fellow

of the British Academy. Corresponding Member of the Institute of

France and of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences. Author of

Handbook of Greek and Latin Palaeography. Editor of the

Chronicon Angliae, &c. Joint-editor of Publications of

the Palaeographical Society.

|

Autographs.

|

|

E. N. S.

|

E. N. Stockley.

Captain, Royal Engineers. Instructor in Construction at the School of

Military Engineering, Chatham. For some time in charge of the

Barracks Design Branch of the War Office.

|

Barracks.

|

|

E. Pr.

|

Edgar Prestage.

Special Lecturer in Portuguese Literature in the University of

Manchester. Commendador, Portuguese Order of S. Thiago. Corresponding

Member of Lisbon Royal Academy of Sciences and Lisbon Geographical

Society.

|

Azurara; Barros.

|

|

E. Tn.

|

Rev. Ethelred Leonard Taunton (d.

1907).

Author of The English Black Monks of St Benedict; History

of the Jesuits in England.

|

Baronius.

|

|

E. V.

|

Rev. Edmund Venables, M.A., D.D.

(1819-1895).

Canon and Precentor of Lincoln. Author of Episcopal Palaces of

England.

|

Basilica (in part).

|

|

F. C. B.

|

Francis Crawford Burkitt, M.A., D.D.

Norrisian Professor of Divinity, Cambridge. Fellow of the British

Academy. Part-editor of The Four Gospels in Syriac transcribed

from the Sinaitic Palimpsest. Author of The Gospel History and

its Transmission; Early Eastern Christianity; &c.

|

Bible: New Testament, Higher Criticism.

|

|

F. C. C.

|

Frederick Cornwallis Conybeare, M.A.,

D.Th. (Giessen).

Fellow of the British Academy. Formerly Fellow of University College,

Oxford. Author of The Ancient Armenian Texts of Aristotle;

Myth, Magic and Morals; &c.

|

Baptism.

|

|

F. G.

|

Frederick Greenwood.

See the biographical article: Greenwood,

Frederick.

|

Beaconsfield, Earl of.

|

|

F. G. M. B.

|

Frederick George Meeson Beck, M.A.

Fellow and Lecturer of Clare College, Cambridge.

|

Bernicia.

|

|

F. Ll. G.

|

Francis Llewelyn Griffith, M.A., Ph.D.,

F.S.A.

Reader in Egyptology, Oxford. Editor of the Archaeological

Survey and Archaeological Reports of the Egypt Exploration

Fund. Fellow of the Imperial German Archaeological Institute.

|

Bes.

|

|

F. L. L.

|

Lady Lugard.

See the biographical article: Lugard, Sir F. J.

D.

|

Bauchi.

|

|

F. P.

|

Frank Podmore, M.A. (d. 1910).

Pembroke College, Oxford. Author of Studies in Psychical

Research; Modern Spiritualism; &c.

|

Automatic Writing.

|

|

F. R. C.

|

Frank R. Cana.

Author of South Africa from the Great Trek to the Union.

|

Basutoland (in part); Bahr-el-Ghazal (in part);

Bechuanaland (in part).

|

|

F. R. M.

|

Francis Richard Maunsell, C.M.G.

Lieut.-Col., Royal Artillery. Military Vice-Consul, Sivas, Trebizond,

Van (Kurdistan), 1897-1898. Military Attaché, British Embassy,

Constantinople, 1901-1905. Author of Central Kurdistan;

&c.

|

Baiburt; Bashkala.

|

|

F. W. R.*

|

Frederick William Rudler, I.S.O.,

F.G.S.

Curator and Librarian of the Museum of Practical Geology, London,

1879-1902. President of the Geologists' Association, 1887-1889.

|

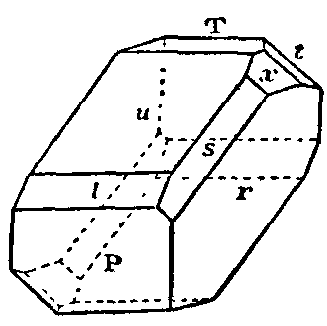

Aventurine; Beryl.

|

|

G. A. B.

|

George A. Boulenger, F.R.S., D.Sc.,

Ph.D.

In charge of the Collections of Reptiles and Fishes, Department of

Zoology, British Museum. Vice-President of the Zoological Society of

London.

|

Axolotl; Batrachia.

|

|

G. A. Gr.

|

George Abraham Grierson, C.I.E., Ph.D.

D.Litt. (Dublin).

Member of the Indian Civil Service, 1873-1903. In charge of

Linguistic Survey of India, 1898-1902. Gold Medallist, Asiatic

Society, 1909. Vice-President of the Royal Asiatic Society. Formerly

Fellow of Calcutta University. Author of The Languages of

India; &c.

|

Bengali; Bihari.

|

|

G. B. B.

|

Gerard Baldwin Brown, M.A.

Professor of Fine Arts, University of Edinburgh. Formerly Fellow of

Brasenose College, Oxford. Author of From Schola to Cathedral;

The Fine Arts; &c.

|

Basilica (in part).

|

|

G. B. G.*

|

George Buchanan Gray, M.A., D.D., D.Litt.

(Oxon.)

Professor of Hebrew and Old Testament Exegesis, Mansfield College,

Oxford. Examiner in Hebrew, University of Wales. Author of The

Divine Discipline of Israel; &c.

|

Bible: Old Testament, Textual Criticism, and Higher

Criticism

|

|

G. E.

|

Rev. George Edmundson, M.A.,

F.R.Hist.S.

Formerly Fellow and Tutor of Brasenose College, Oxford. Ford's

Lecturer, 1909. Hon. Member Dutch Historical Society, and Foreign

Member, Netherlands Association of Literature.

|

Belgium: History.

|

|

G. F. Z.

|

G. F. Zimmer, A.M.Inst.C.E.

Author of Mechanical Handling of Material.

|

Biscuit.

|

|

G. G. S.

|

George Gregory Smith, M.A.

Professor of English Literature, Queen's University, Belfast. Author

of The Days of James IV.; The Transition Period;

Specimens of Middle Scots; &c.

|

Barbour, John.

|

|

G. H. C.

|

George Herbert Carpenter, B.Sc.

Professor of Zoology in the Royal College of Science, Dublin.

President of the Association of Economic Biologists. Member of the

Royal Irish Academy. Author of Insects: their Structure and

Life; &c.

|

Bee.

|

|

G. Sa.

|

George Edward Bateman Saintsbury, LL.D.,

D.Litt.

See the biographical article: Saintsbury, G. E.

B.

|

Balzac, H. de.

|

|

G. W. T.

|

Rev. Griffithes Wheeler Thatcher, M.A.,

B.D.

Warden of Camden College, Sydney, N.S.W. Formerly Tutor in Hebrew and

Old Testament History at Mansfield College, Oxford.

|

Avempace; Averroes; Avicenna; Baidāwī;

Balādhurī; Behā ud-Dīn; Behā ud-Din

Zuhair; Bīrūnī.

|

|

H. Br.

|

Henry Bradley, M.A., Ph.D.

Joint-editor of the New English Dictionary (Oxford). Fellow of

the British Academy. Author of The Story of the Goths; The

Making of English; &c.

|

Beowulf.

|

|

H. Ch.

|

Hugh Chisholm, M.A.

Formerly Scholar of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Editor of the

11th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Co-editor of the

10th edition.

|

Balfour, A. J.

|

|

H. C. R.

|

Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, Bart.,

K.C.B.

See the biographical article: Rawlinson, Sir H.

C.

|

Bagdad: City.

|

|

H. Fr.

|

Henri Frantz.

Art Critic, Gazette des Beaux Arts (Paris).

|

Barye; Bastien-Lepage; Baudry, P. J. A.

|

|

H. F. G.

|

Hans Friedrich Gadow, F.R.S., Ph.D.

Strickland Curator and Lecturer on Zoology in the University of

Cambridge. Author of "Amphibia and Reptiles" in the Cambridge

Natural History.

|

Bird.

|

|

H. H. H.*

|

Herbert Hensley Henson, M.A., D.D.

Canon of Westminster Abbey and Rector of St Margaret's, Westminster.

Proctor in Convocation since 1902. Formerly Fellow of All Souls'

College, Oxford. Select Preacher (Oxford), 1895-1896; (Cambridge),

1901. Author of Apostolic Christianity; Moral Discipline in

the Christian Church; The National Church; Christ and

the Nation; &c.

|

Bible, English: Revised Version.

|

|

H. H. J.

|

Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston, D.Sc., G.C.M.G.,

K.C.B.

See the biographical article: Johnston, Sir H.

H.

|

Bantu Languages.

|

|

H. M. R.

|

Hugh Munro Ross.

Formerly Exhibitioner of Lincoln College, Oxford. Editor of The

Times Engineering Supplement. Author of British

Railways.

|

Bell: House Bell.

|

|

H. M. W.

|

H. Marshall Ward, M.A., F.R.S., D.Sc. (d.

1905).

Formerly Professor of Botany, Cambridge. President of the British

Mycological Society. Author of Timber and some of its

Diseases; The Oak; Sach's Lectures the Physiology of

Plants; Grasses; Disease in Plants; &c.

|

Bacteriology (in part); Berkeley, Miles Joseph.

|

|

H. N. D.

|

Henry Newton Dickson, M.A., D.Sc.,

F.R.G.S.

Professor of Geography, University College, Reading. Author of

Elementary Meteorology; Papers on Oceanography;

&c.

|

Baltic Sea.

|

|

H. W. C. D.

|

Henry William Carless Davis, M.A.

Fellow and Tutor of Balliol College, Oxford. Fellow of All Souls',

Oxford, 1895-1902. Author of Charlemagne; England under the

Normans and Angevins, 1066-1272.

|

Becket; Benedictus Abbas.

|

|

H. W. S.

|

H. Wickham Steed.

Correspondent of The Times at Rome (1897-1902) and Vienna.

|

Austria-Hungary: History (in part);

Bertani.

|

|

I. A.

|

Israel Abrahams, M.A.

Reader in Talmudic and Rabbinic Literature, University of Cambridge.

President, Jewish Historical Society of England. Author of A Short

History of Jewish Literature; Jewish Life in the Middle

Ages; &c.

|

Bahya.

|

|

J. An.

|

Joseph Anderson, LL.D.

Keeper of the National Museum of Antiquities, Edinburgh, and

Assistant Secretary of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Honorary Professor of Antiquities to the Royal Scottish Academy.

Author of Scotland in Early Christian and Pagan Times.

|

Barrow.

|

|

J. A. H.

|

John Allen Howe, B.Sc.

Curator and Librarian at the Museum of Practical Geology, London.

|

Avonian; Bajocian; Barton Beds; Bathonian Series; Bed:

Geology.

|

|

J. B. B.

|

John Bagnell Bury, LL.D., Litt.D.

See the biographical article: Bury, J. B.

|

Baldwin I. and II.: of Romania; Basil I. and II.:

Emperors; Belisarius.

|

|

J. D. B.

|

James David Bourchier, M.A., F.R.G.S.

King's College, Cambridge. Correspondent of The Times in

South-Eastern Europe. Commander of the Orders of Prince Danilo of

Montenegro and of the Saviour of Greece, and Officer of the Order of

St Alexander of Bulgaria.

|

Balkan Peninsula.

|

|

J. F.-K.

|

James Fitzmaurice-Kelly, Litt.D.,

F.R.Hist.S.

Gilmour Professor of Spanish Language and Literature, Liverpool

University. Norman McColl Lecturer, Cambridge University. Fellow of

the British Academy. Member of the Council of the Hispanic Society of

America. Knight Commander of the Order of Alphonso XII. Author of

A History of Spanish Literature.

|

Ayala y Herrera; Bello.

|

|

J. F. St.

|

John Frederick Stenning, M.A.

Dean and Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford. University Lecturer in

Aramaic. Lecturer in Divinity and Hebrew at Wadham College.

|

Bible: Old Testament: Texts and Versions.

|

|

J. H. R.

|

John Horace Round, M.A., LL.D. (Edin.).

Author of Feudal England; Studies in Peerage and Family

History; Peerage and Pedigree; &c.

|

Baron; Baronet; Battle Abbey Roll; Bayeux Tapestry;

Beauchamp.

|

|

J. Hl. R.

|

John Holland Rose, M.A., Litt.D.

Christ's College, Cambridge. Lecturer on Modern History to the

Cambridge University Local Lectures Syndicate. Author of Life of

Napoleon I.; Napoleonic Studies; The Development of the

European Nations; The Life of Pitt; &c.

|

Barras; Beauharnais, Eugène de.

|

|

J. M. M.

|

John Malcolm Mitchell.

Sometime Scholar of Queen's College, Oxford. Lecturer in Classics,

East London College (University of London). Joint editor of Grote's

History of Greece.

|

Bacon, Francis (in part); Berkeley, George (in

part).

|

|

J. P.-B.

|

James George Joseph Penderel-Brodhurst.

Editor of the Guardian (London).

|

Bed: Furniture; Bérain.

|

|

J. G. Sc.

|

Sir James George Scott, K.C.I.E.

Superintendent and Political Officer, Southern Shan States. Author of

Burma, a Handbook; The Upper Burma Gazetteer,

&c.

|

Bhamo.

|

|

J. P. E.

|

Jean Paul Hippolyte Emmanuel Adhémar

Esmein.

Professor of Law in the University of Paris. Officer of the Legion of

Honour. Member of the Institute of France. Author of Cours

eléméntaire d'histoire du droit français; &c.

|

Bailiff: Bailli; Basoche.

|

|

J. P. Pe.

|

Rev. John Punnett Peters, Ph.D., D.D.

Canon Residentiary, Cathedral of New York. Formerly Professor of

Hebrew, University of Pennsylvania. In charge of Expedition of

University of Pennsylvania conducting excavations at Nippur,

1888-1895. Author of Scriptures, Hebrew and Christian;

Nippur, or Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates;

&c.

|

Bagdad: Vilayet; Bagdad: City; Basra.

|

|

J. R. P.

|

Sir John Rahere Paget, Bart., K.C.

Bencher of the Inner Temple. Formerly Gilbart Lecturer on Banking.

Author of The Law of Banking; &c.

|

Banks and Banking: English Law.

|

|

J. Sm.*

|

John Smith, C.B.

Formerly Inspector-General in Companies' Liquidation, 1890-1904, and

Inspector-General in Bankruptcy.

|

Bankruptcy.

|

|

J. S. F.

|

John Smith Flett, D.Sc., F.G.S.

Petrographer to the Geological Survey. Formerly Lecturer on Petrology

in Edinburgh University. Neill Medallist of the Royal Society of

Edinburgh. Bigsby Medallist of the Geological Society of London.

|

Basalt; Batholite.

|

|

J. T. Be.

|

John T. Bealby.

Joint author of Stanford's Europe. Formerly Editor of the

Scottish Geographical Magazine. Translator of Sven Hedin's

Through Asia, Central Asia and Tibet, &c.

|

Baikal; Bessarabia (in part)

|

|

J. Vn.

|

Julien Vinson.

Formerly Professor of Hindustani and Tamil at the École des Langues

Orientales, Paris. Author of Le Basque et les langues

mexicaines; &c.

|

Basques (in part).

|

|

J. V. B.

|

James Vernon Bartlet, M.A., D.D. (St

Andrews).

Professor of Church History, Mansfield College, Oxford. Author of

The Apostolic Age; &c.

|

Barnabas.

|

|

J. W. He.

|

James Wycliffe Headlam, M.A.

Staff Inspector of Secondary Schools under the Board of Education.

Formerly Fellow of King's College, Cambridge. Professor of Greek and

Ancient History at Queen's College, London. Author of Bismarck and

the Foundation of the German Empire; &c.

|

Austria-Hungary: History; Bamberger; Bebel; Benedetti;

Beust.

|

|

K. L.

|

Rev. Kirsopp Lake, M.A.

Lincoln College, Oxford. Professor of Early Christian Literature and

New Testament Exegesis in the University of Leiden. Author of The

Text of the New Testament; The Historical Evidence for the

Resurrection of Jesus Christ; &c.

|

Bible: New Testament: Texts and Versions and Textual

Criticism.

|

|

K. S.

|

Kathleen Schlesinger.

Author of The Instruments of the Orchestra.

|

Bagpipe; Banjo; Barbiton; Barrel-organ; Bass Clarinet; Basset

Horn; Bassoon; Batyphone.

|

|

L. A.

|

Lyman Abbott, D.D.

See the biographical article: Abbott, L.

|

Beecher, Henry Ward.

|

|

L. P.*

|

Louis Marie Olivier Duchesne.

See the biographical article: Duchesne, L. M.

O.

|

Benedict (I.-X.)

|

|

L. J. S.

|

Leonard James Spencer, M.A., F.G.S.

Assistant, Department of Mineralogy, Natural History Museum, South

Kensington. Formerly Scholar of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, and

Harkness Scholar. Editor of the Mineralogical Magazine.

|

Autunite; Axinite; Azurite; Barytes; Bauxite; Biotite.

|

|

L. V.*

|

Luigi Villari.

Italian Foreign Office (Emigration Dept.). Formerly Newspaper

Correspondent in East of Europe. Author of Italian Life in Town

and Country; &c.

|

Azeglio; Bandiera, A. and E.; Bassi, Ugo; Bentivoglio,

Giovanni.

|

|

L. W. K.

|

Leonard William King, M.A., F.S.A.

Assistant to the Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities, British

Museum. Lecturer in Assyrian at King's College, London. Conducted

Excavations at Kuyunjik (Nineveh) for British Museum. Author of

Assyrian Chrestomathy; Annals of the Kings of Assyria;

Studies in Eastern History; Babylonian Magic and

Sorcery; &c.

|

Babylonia and Assyria: Chronology.

|

|

M. A. C.

|

Maurice A. Canney, M.A.

Assistant Lecturer in Semitic Languages in the University of

Manchester. Formerly Exhibitioner of St John's College, Oxford. Pusey

and Ellerton Hebrew Scholar (Oxford), 1892; Kennicott Hebrew Scholar,

1895; Houghton Syriac Prize, 1896.

|

Baur.

|

|

M. Br.

|

Margaret Bryant.

|

Beaumont and Fletcher: Appendix.

|

|

M. D. Ch.

|

Sir Mackenzie Dalzell Chalmers, K.C.B., C.S.I.,

M.A.

Trinity College, Oxford. Barrister-at-Law. Formerly Permanent

Under-Secretary of State for Home Department. Author of Digest of

the Law of Bills of Exchange; &c.

|

Bill of Exchange.

|

|

M. G.

|

Moses Gaster, Ph.D. (Leipzig).

Chief Rabbi of the Sephardic Communities of England. Vice-President,

Zionist Congress, 1898, 1899, 1900. Ilchester Lecturer at Oxford on

Slavonic and Byzantine Literature, 1886 and 1891. Author of A New

Hebrew Fragment of Ben-Sira; The Hebrew Version of the

Secretum Secretorum of Aristotle.

|

Bassarab.

|

|

M. H. C.

|

Montague Hughes Crackanthorpe, K.C.,

D.C.L.

Honorary Fellow, St John's College, Oxford. Bencher of Lincoln's Inn.

President of the Eugenics Education Society. Formerly Member of the

General Council of the Bar and of the Council of Legal Education, and

Standing Counsel to the University of Oxford.

|

Bering Sea Arbitration.

|

|

M. Ja.

|

Morris Jastrow, Ph.D.

Professor of Semitic Languages, University of Pennsylvania. Author of

Religion of the Babylonians and Assyrians; &c.

|

Babylonia and Assyria: Proper Names; Babylonian and

Assyrian Religion; Bel; Belit.

|

|

M. P.*

|

Léon Jacques Maxime Prinet.

Auxiliary of the Institute of France (Academy of Moral and Political

Sciences), Author of L'Industrie du sel en Franche-Comté.

|

Avaray; Bar-le-Duc; Batarnay; Bauffremont; Beauharnais;

Beaujeu; Beauvillier; Bellegarde: Family.

|

|

N. B. W.

|

N. B. Wagle.

Formerly Lecturer on Sanskrit at the Robert Money Institution,

Bombay. Vice-President of the London Indian Society. Author of

Industrial Development of India; &c.

|

Bhau Daji.

|

|

N. H. M.

|

Rev. Newton Herbert Marshall., M.A., Ph.D.

(Halle).

Minister of Heath Street Baptist Church, Hampstead, London. Author of

Gegenwartige Richtungen der Religionsphilosophie in England;

Theology and Truth.

|

Baptists.

|

|

N. M.

|

Norman McLean, M.A.

Fellow, Lecturer and Librarian of Christ's College, Cambridge.

University Lecturer in Aramaic. Examiner for the Oriental Languages

Tripos and the Theological Tripos at Cambridge.

|

Bardaisān; Bar-Hebraeus; Bar-Salībī.

|

|

N. V.

|

Joseph Marie Noel Valois.

Member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. Honorary

Archivist at the Archives Nationales. Formerly President of the

Société de l'Histoire de France and of the Société de l'École de

Chartes.

|

Basel, Council of; Benedict XIII. (anti-pope).

|

|

N. W. T.

|

Northcote Whitbridge Thomas, M.A.

Government Anthropologist to Southern Nigeria. Corresponding Member

of the Société d'Anthropologie de Paris. Author of Thought

Transference; Kinship and Marriage in Australia;

&c.

|

Automatism.

|

|

O. Ba.

|

Oswald Barron, F.S.A.

Editor of The Ancestor, 1902-1905.

|

Beard; Berkeley (Family); Bill (Weapon).

|

|

O. Br.

|

Oscar Briliant.

|

Austria-Hungary: Statistics.

|

|

O. Hr.

|

Otto Henker, Ph.D.

On the Staff of the Carl Zeiss Factory, Jena, Germany.

|

Binocular Instrument.

|

|

P. A.

|

Paul Daniel Alphandéry.

Professor of the History of Dogma, École Pratique des Hautes Études,

Sorbonne, Paris. Author of Les Idées morales chez les hétérodoxes

latines au début du XIIIe siècle.

|

Auto-da-Fé.

|

|

P. A. A.

|

Philip A. Ashworth, M.A., Doc.Juris.

New College, Oxford. Barrister-at-Law. Translator of H. R. von

Gneist's History of the English Constitution.

|

Bavaria: Statistics; Berlin.

|

|

P. A. K.

|

Prince Peter Alexeivitch Kropotkin.

See the biographical article: Kropotkin, P.

A.

|

Baikal; Baku; Bessarabia (in part).

|

|

P. C. M.

|

Peter Chalmers Mitchell, M.A., F.R.S., F.Z.S.,

D.Sc., LL.D.

Secretary to the Zoological Society of London. University

Demonstrator in Comparative Anatomy and Assistant to Linacre

Professor at Oxford, 1888-1891. Examiner in Zoology to the University

of London, 1903. Author of Outlines of Biology; &c.

|

Biogenesis; Biology.

|

|

P. C. Y.

|

Philip Chesney Yorke, M.A.

Magdalen College, Oxford.

|

Balfour, Sir James.

|

|

P. Gi.

|

Peter Giles, M.A., Litt.D., LL.D.

Fellow and Classical Lecturer of Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

University Reader in Comparative Philology. Formerly Secretary of the

Cambridge Philological Society. Author of Manual of Comparative

Philology; &c.

|

B.

|

|

P. S.

|

Philip Schidrowitz, Ph.D., F.C.S.

Member of Council, Institute of Brewing; Member of Committee of

Society of Chemical Industry. Author of numerous articles on the

Chemistry and Technology of Brewing, Distilling, &c.

|

Beer.

|

|

R. A.*

|

Robert Anchel.

Archivist of the Département de l'Eure.

|

Billaud-Varenne.

|

|

R. Ad.

|

Robert Adamson, M.A., LL.D.

See the biographical article: Adamson,

Robert.

|

Bacon, Francis; Bacon, Roger; Beneke; Berkeley, Bishop.

|

|

R. A. S. M.

|

Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister, M.A.,

F.S.A.

St John's College, Cambridge. Director of Excavations for the

Palestine Exploration Fund. Joint author of Excavations in

Palestine, 1898-1900.

|

Bashan; Bethlehem.

|

|

R. C. J.

|

Sir Richard Claverhouse Jebb, LL.D., D.C.L.,

Litt.D.

See the biographical article: Jebb, Sir Richard

C.

|

Bacchylides.

|

|

R. Gn.

|

Sir Robert Giffen, F.R.S.

See the biographical article: Giffen, Sir

R.

|

Bagehot; Balance Of Trade.

|

|

R. H. C.

|

Rev. Robert Henry Charles, M.A., D.D.,

Litt.D. (Oxon.).

Grinfield Lecturer and Lecturer in Biblical Studies, Oxford. Fellow

of the British Academy. Formerly Senior Moderator of Trinity College,

Dublin. Author and Editor of Book of Enoch; Book of

Jubilees; Apocalypse of Baruch; Assumption of

Moses; Ascension of Isaiah; Testaments of XII.

Patriarchs; &c.

|

Baruch.

|

|

R. H. I. P.

|

Sir Robert Harry Inglis Palgrave,

F.R.S.

Director of Barclay & Co., Ltd., Bankers. Editor of the

Economist, 1871-1883. Author of Notes on Banking in Great

Britain and Ireland, Sweden, Denmark and Hamburg; &c. Editor

of Dictionary of Political Economy.

|

Banks and Banking: General.

|

|

R. J. M.

|

Ronald John McNeill, M.A.

Christ Church, Oxford. Barrister-at-Law. Formerly Editor of the St

James's Gazette (London).

|

Beresford, John.

|

|

R. L.*

|

Richard Lydekker, F.R.S., F.G.S.,

F.Z.S.

Trinity College, Cambridge. Member of the Staff of the Geological

Survey of India, 1874-1882. Author of Catalogues of Fossil

Mammals, Reptiles and Birds in British Museum; The Deer of all

Lands; &c.

|

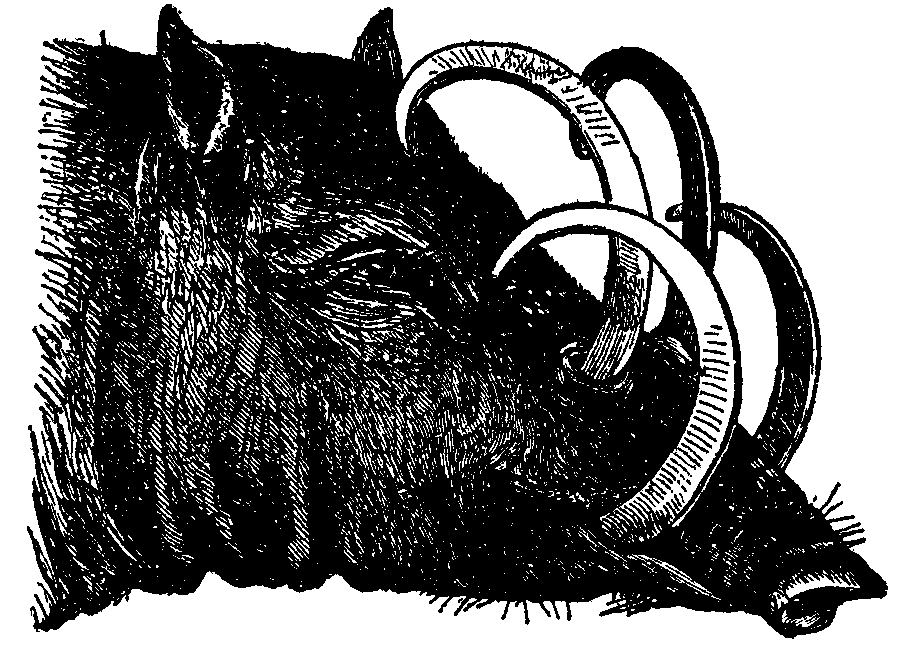

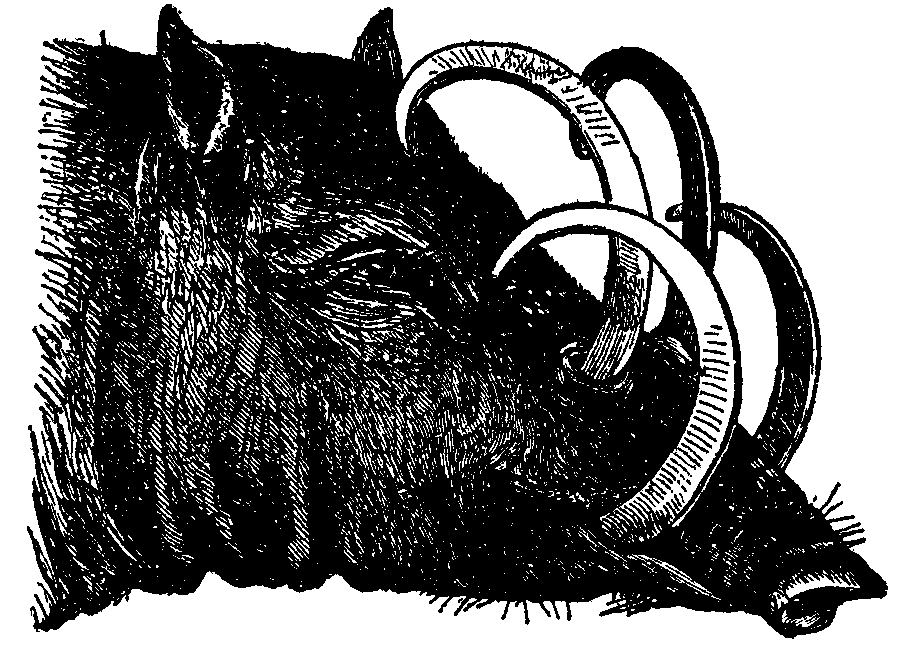

Avahi; Aye-Aye; Babirusa; Baboon; Beaver.

|

|

R. L. S.

|

Robert Louis Stevenson.

See the biographical article: Stevenson, R. L.

B.

|

Béranger.

|

|

R. M.*

|

Robert Muir, M.A., M.D., F.R.C.P.

(Edin.).

Professor of Pathology, University of Glasgow. Professor of Pathology

at St Andrews, 1898-1899. Author of Manual of Bacteriology;

&c.

|

Bacteriology: Pathological Aspects.

|

|

R. N. B.

|

Robert Nisbet Bain (d. 1909).

Assistant Librarian, British Museum, 1883-1909. Author of

Scandinavia: the Political History of Denmark, Norway and Sweden,

1513-1900; The First Romanovs, 1613-1725; Slavonic

Europe: the Political History of Poland and Russia from 1469 to

1796; Charles XII. and the Collapse of the Swedish Empire;

Gustavus III. and his Contemporaries; The Pupils of Peter

the Great; &c.

|

Bakócz; Balassa; Bánffy; Bar, Confederation of; Baross; Basil;

Báthory; Batthyany; Bela III. and IV; Bern; Beöthy; Bernstorff;

Bestuzhev-Ryumin; Bethlen; Bezborodko; Biren.

|

|

S. A. C.

|

Stanley Arthur Cook, M.A.

Editor for Palestine Exploration Fund. Lecturer and formerly Fellow,

Gonville and Caius College. Author of Glossary of Aramaic

Inscriptions; The Laws of Moses and Code of Hammurabi;

Critical Notes on Old Testament History; &c.

|

Baal; Benjamin.

|

|

S. C.

|

Sidney Colvin, M.A., Litt.D.

See the biographical article: Colvin,

Sidney.

|

Baldovinetti; Bellini.

|

|

S. R. D.

|

Samuel Rolles Driver, D.D., Litt.D.

See the biographical article: Driver, S.

R.

|

Bible: Old Testament: Canon and

Chronology.

|

|

T. A. J.

|

Thomas Athol Joyce, M.A.

Assistant in Department of Ethnography, British Museum. Hon. Sec.,

Royal Anthropological Institute.

|

Bechuana.

|

|

T. As.

|

Thomas Ashby, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon.),

F.S.A.

Director of British School of Archaeology at Rome. Formerly Scholar

of Christ Church, Oxford. Craven Fellow (Oxford). Corresponding

Member of the Imperial German Archaeological Institute. Author of the

Classical Topography of the Roman Campagna; &c.

|

Auximum; Avella; Avellino; Avernus; Baiae; Bari; Barletta;

Bassano; Belluno; Benevento; Bergamo; Bertinoro.

|

|

T. A. I.

|

Thomas Allan Ingram, M.A., LL.D.

Trinity College, Dublin.

|

Bailiff; Bill (law); Bill of Sale.

|

|

T. Ba.

|

Sir Thomas Barclay, M.P.

Member of the Institute of International Law. Member of the Supreme

Council of the Congo Free State. Officer of the Legion of Honour.

Author of Problems of International Practice and Diplomacy;

&c. M.P. for Blackburn, 1910.

|

Belligerency.

|

|

T. E. H.

|

Thomas Erskine Holland, K.C., D.C.L.,

LL.D.

Fellow of the British Academy. Fellow of All Souls' College, Oxford.

Formerly Professor of International Law in the University of Oxford.

Bencher of Lincoln's Inn. Author of Studies in International

Law; The Elements of Jurisprudence; Alberici Gentilis

de jure belli; The Laws of War on Land; Neutral Duties

in a Maritime War; &c.

|

Bentham, Jeremy.

|

|

T. G. C.

|

Thomas G. Carver, M.A., K.C. (d. 1906).

Formerly Scholar of St John's College, Cambridge. 8th Wrangler, 1871.

Author of On the Law Relating to the Carriage of Goods by

Sea.

|

Average.

|

|

T. H. D.

|

Rev. Thomas Herbert Darlow, M.A.

Literary Superintendent of the British and Foreign Bible Society.

Sometime Scholar of Clare College, Cambridge. Author of Historical

Catalogue of Printed Editions of Holy Scriptures (vol. i. with H.

G. Moule); &c.

|

Bible Societies.

|

|

T. H. H.

|

Thomas Henry Huxley, F.R.S.

See the biographical article: Huxley, Thomas

H.

|

Biology (in part).

|

|

T. H. H.*

|

Sir Thomas Hungerford Holdich K.C.M.G., K.C.I.E.,

D.Sc., F.R.G.S.

Colonel in the Royal Engineers. Superintendent, Frontier Surveys,

India, 1892-1898. Gold Medallist, R.G.S. (London), 1887. H. M.

Commissioner for the Persa-Beluch Boundary, 1896. Author of The

Indian Borderland; The Gates of India; &c.

|

Badakshan; Bahrein Islands; Bajour; Balkh; Baluchistan; Bamian;

Bela; Bhutan.

|

|

T. L. P.

|

Rev. Thomas Leslie Papillon, M.A.

Hon. Canon of St Albans. Formerly Fellow, Dean and Tutor of New

College, Oxford. Fellow of Merton College. Author of Manual of

Comparative Philology; &c.

|

Bell.

|

|

T. O.

|

Thomas Okey.

Examiner in Basket Work for the City of London Guilds and

Institute.

|

Basket.

|

|

T. W. R. D.

|

T. W. Rhys Davids, M.A., LL.D., Ph.D.

Professor of Comparative Religion in the University of Manchester.

Formerly Professor of Pali and Buddhist Literature, University

College, London. Fellow of the British Academy. Secretary and

Librarian of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1885-1902. Author of Early

Buddhism; Buddhist India; &c.

|

Bharahat.

|

|

V. H. B.

|

Vernon Herbert Blackman, M.A., D.Sc.

Professor of Botany in the University of Leeds. Formerly Fellow of St

John's College, Cambridge.

|

Bacteriology: Botany

|

|

W. A. B. C.

|

Rev. William Augustus Brevoort Coolidge, M.A.,

F.R.G.S., Ph.D.

Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford. Professor of English History, St

David's College Lampeter, 1880-1881. Author of Guide to

Switzerland; The Alps in Nature and in History; &c.

Editor of the Alpine Journal, 1880-1889.

|

Baden: Switzerland; Barcelonnette; Basel; Basses-Alpes;

Beaulieu; Bellinzona; Bern; Bienne.

|

|

W. A. G.

|

Walter Armstrong Graham.

His Siamese Majesty's Resident Commissioner for the Siamese Malay

State of Kelantan. Commander, Order of the White Elephant. Member of

the Burma Civil Service, 1889-1903. Author of The French Roman

Catholic Mission in Siam; Kelantan, a Handbook;

&c.

|

Bangkok.

|

|

W. A. P.

|

Walter Alison Phillips, M.A.

Formerly Exhibitioner of Merton College and Senior Scholar of St

John's College, Oxford. Author of Modern Europe; The War of

Greek Independence; &c.

|

Austria-Hungary: History (in part); Babeuf;

Balance of Power; Baron; Bates; Bavaria: History; Béguines;

Berlin: Congress and Treaty of; Bernard, St.; Biretta.

|

|

W. Bo.

|

Wilhelm Bousset, D.Th.

Professor of New Testament Exegesis in the University of Gottingen.

Author of Das Wesen der Religion; The Antichrist

Legend; &c.

|

Basilides.

|

|

W. B. Ca.

|

W. Broughton Carr.

Formerly Editor of the British Bee Journal and the

Bee-Keepers' Record.

|

Bee: Bee-keeping.

|

|

W. C. P.

|

William Charles Popplewell, M.Sc.,

A.M.I.C.E.

Lecturer in Engineering in Manchester School of Technology

(University of Manchester). Author of Compressed Air; Heat

Engines; &c.

|

Bellows and Blowing Machines.

|

|

W. E. D.

|

William Ernest Dalby, M.A., M.Inst.C.E.,

M.I.M.E.

Professor of Civil and Mechanical Engineering at the City and Guilds

of London Institute Central Technical College, South Kensington.

Associate Member of the Institute of Naval Architects. Author of

The Balancing of Engines; Valves and Valve Gear

Mechanisms; &c.

|

Bearings.

|

|

W. E. G.

|

Sir William Edmund Garstin, G.C.M.G.

Governing Director, Suez Canal Co. Formerly Inspector-General of

Irrigation, Egypt. Adviser to the Ministry of Public Works in Egypt,

1904-1908.

|

Bahr-el-Ghazal (in part).

|

|

W. H. Be.

|

William Henry Bennett, M.A., D.D., D.Litt.

(Cantab.).

Professor of Old Testament Exegesis in New and Hackney Colleges,

London. Formerly Fellow of St John's College, Cambridge. Lecturer in

Hebrew at Firth College, Sheffield. Author of Religion of the

Post-Exilic Prophets; &c.

|

Balaam; Beelzebub.

|

|

W. H. Ha.

|

William Henry Hadow, M.A., Mus.Doc.

Principal, Armstrong College, Newcastle-on-Tyne. Formerly Fellow and

Tutor of Worcester College, Oxford. Member of Council, Royal College

of Music. Editor Oxford History of Music. Author of Studies

in Modern Music; &c.

|

Bach, K. P. E.

|

|

W. J. H.*

|

William James Hughan.

Past Senior Grand Deacon of Freemasons of England, 1874. Hon. Senior

Warden of Grand Lodges of Egypt, Quebec and Iona, &c.

|

Banker-Marks.

|

|

W. L. D.

|

William Leslie Davidson, LL.D.

Professor of Logic and Metaphysics, Aberdeen University. Author of

The Logic of Definition; Christian Ethics; &c.

Editor of Alexander Bain's Autobiography.

|

Bain, Alexander.

|

|

W. M. S.

|

William Milligan Sloane, Ph.D., LL.D.

Professor of History, Columbia University, New York. Secretary to

George Bancroft while American Ambassador in Berlin, 1872-1875.

Author of Life of Napoleon Bonaparte.

|

Bancroft, George.

|

|

W. P. C.

|

William Prideaux Courtney.

See the article: Courtney, L. H., Baron.

|

Bath, William Pulteney, Marquess of.

|

|

W. P. J.

|

William Price James.

University College, Oxford. Barrister-at-Law. High Bailiff of County

Courts, Cardiff. Author of Romantic Professions; &c.

|

Barrie, J. M.

|

|

W. P. R.

|

Hon. William Pember Reeves.

Director of London School of Economics. Agent-General and High

Commissioner for New Zealand, 1896-1909. Minister of Education,

Labour and Justice, New Zealand, 1891-1896. Author of The Long

White Cloud, a History of New Zealand; &c.

|

Ballance, John.

|

|

W. R. L.

|

W. R. Lethaby, F.S.A.

Principal of the Central School of Arts and Crafts under the London

County Council. Author of Architecture, Mysticism and Myth;

&c.

|

Baptistery.

|

|

W. Sa.

|

William Sanday, D.D., LL.D., Litt.D.

Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity, arid Canon of Christ Church,

Oxford. Chaplain in Ordinary to His Majesty the King. Hon. Fellow of

Exeter College, Oxford. Fellow of the British Academy. Author of

Inspiration (Bampton Lecture, 1893); Commentary on the

Epistle to the Romans; &c.

|

Bible: New Testament: Canon.

|

|

W. T. Ca.

|

William Thomas Calman, D.Sc., F.Z.S.

Assistant in charge of Crustacea, Natural History Museum, South

Kensington. Author of "Crustacea" in Lankester's Treatise on

Zoology.

|

Barnacle.

|

|

W. T. T.-D.

|

Sir William Turner Thiselton-Dyer, F.R.S.,

K.C.M.G., C.I.E., D.Sc. LL.D., Ph.D., F.L.S.

Hon. Student of Christ Church, Oxford. Director, Royal Botanic

Gardens, Kew, 1885-1905. Botanical Adviser to Secretary of State for

Colonies, 1902-1906. Joint-author of Flora of Middlesex.

Editor of Flora Capenses and Flora of Tropical

Africa.

|

Bentham, George.

|

|

W. W.

|

William Wallace, M.A.

See the biographical article: Wallace,

William (1844-1897).

|

Averroes; Avicenna.

|

|

W. We.

|

Rev. Wentworth Webster (d. 1906).

Author of Basque Legends; &c.

|

Basque Provinces; Basques.

|

|

W. Wr.

|

Williston Walker, Ph.D., D.D.

Professor of Church History, Yale University. Author of History of

the Congregational Churches in the United States; The

Reformation; John Calvin; &c.

|

Bacon, Leonard.

|

|

W. R. S.

|

W. Robertson Smith, LL.D.

See the biographical article: Smith, William

Robertson.

|

Baal.

|

|

W. W. R.*

|

William Walker Rockwell, Lic.Theol.

Assistant Professor of Church History, Union Theological Seminary,

New York. Author of Die Doppeleke des Landgrafen Philipp von

Hessen.

|

Benedict XI., XII., XIII., XIV.

|

PRINCIPAL UNSIGNED ARTICLES

|

Azo Compounds.

Azoimide.

Azores.

Baader, F. X.

Baber.

Baby-Farming.

Bachelor.

Backgammon.

Baden: Grand Duchy.

Badger.

Badminton.

Bagatelle.

Bahamas.

Balaklava.

Bale, John.

Baliol.

Ballet.

Ballot.

Balneotherapeutics.

Bamboo.

Ban.

Banana.

Bank-notes.

Barbados.

Barbarossa.

Barbed Wire.

Barcelona.

Barclay, Alexander.

Barère de Vieuzac.

Barium.

Barlaam and Josaphat.

Barley.

|

Barnes, William.

Barometer.

Barrister.

Barrow, Isaac.

Bastiat, F.

Bastille.

Baths.

Battery.

Baudelaire.

Bautzen.

Baxter, Richard.

Bayard, P. T.

Bazaine.

Bean.

Bear.

Bear-Baiting and Bull-Baiting.

Beaton.

Beaufort: Family.

Beaufort, Henry.

Beaumarchais.

Beaumont: Family.

Becher.

Beddoes, Thomas Lovell.

Bedford, Earls and Dukes of.

Bedfordshire.

Bedouins.

Beecher, Lyman.

Behar.

Beheading.

Béjart.

Belfast: Ireland

|

Belfort: Town.

Bell, Sir Charles.

Belladonna.

Bellarmine.

Bellary.

Belle-Isle, C. L. A. F., Duc de.

Benares.

Benedek.

Benediction.

Benefice.

Benevolence.

Bengal.

Bengel.

Benin.

Benjamin (Judah Philip).

Benson (Archbishop of Canterbury).

Bentley, Richard.

Benton.

Benzaldehyde.

Benzene.

Benzoic Acid.

Berar.

Berbers.

Berengarius.

Beresford, Lord Charles.

Beresford, Viscount.

Bergen.

Beri-Beri.

Berkshire.

Berlioz.

Bermondsey.

|

Bermudas.

Bernhardt, Sarah.

Bernouilli.

Berthelot.

Berwick (Duke of).

Berwickshire.

Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Beryllium.

Besançon.

Bessemer, Sir Henry.

Bet and Betting.

Betrothal.

Beyle.

Bézique.

Bhagalpur.

Bible Christians.

Bichromates and Chromates.

Bidder.

Bigamy.

Bijapur.

Bikanir.

Bilaspur.

Bilbao.

Billiards.

Binomial.

Birch.

Birkenhead.

Birmingham.

Birney, James G.

Biron, Armand de Gontaut.

Birth.

Biscay (Vizcaya).

|

A complete list,

showing all individual contributors, appears in the final volume.

[v.03 p.0001]

ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

ELEVENTH EDITION

VOLUME III

AUSTRIA, LOWER (Ger. Niederösterreich or Österreich

unter der Enns, "Austria below the river Enns"), an archduchy and

crownland of Austria, bounded E. by Hungary, N. by Bohemia and Moravia,

W. by Bohemia and Upper Austria, and S. by Styria. It has an area of 7654

sq. m. and is divided into two parts by the Danube, which enters at its

most westerly point, and leaves it at its eastern extremity, near

Pressburg. North of this line is the low hilly country, known as the

Waldviertel, which lies at the foot and forms the continuation of

the Bohemian and Moravian plateau. Towards the W. it attains in the

Weinsberger Wald, of which the highest point is the Peilstein, an

altitude of 3478 ft., and descends towards the valley of the Danube

through the Gföhler Wald (2368 ft.) and the Manhartsgebirge (1758 ft.).

Its most south-easterly offshoots are formed by the Bisamberg (1180 ft.),

near Vienna, just opposite the Kahlenberg. The southern division of the

province is, in the main, mountainous and hilly, and is occupied by the

Lower Austrian Alps and their offshoots. The principal groups are: the

Voralpe (5802 ft.), the Dürrenstein (6156 ft.), the Ötscher (6205 ft.),

the Raxalpe (6589 ft.) and the Schneeberg (6806 ft.), which is the

highest summit in the whole province. To the E. of the famous ridge of

Semmering are the groups of the Wechsel (5700 ft.) and the Leithagebirge

(1674 ft.). The offshoots of the Alpine group are formed by the Wiener

Wald, which attains an altitude of 2929 ft. in the Schöpfl and ends N.W.

of Vienna in the Kahlenberg (1404 ft.) and Leopoldsberg (1380 ft.).

Lower Austria belongs to the watershed of the Danube, which with the

exception of the Lainsitz, which is a tributary of the Moldau, receives

all the other rivers of the province. Its principal affluents on the

right are: the Enns, Ybbs, Erlauf, Pielach, Traisen, Wien, Schwechat,

Fischa and Leitha; on the left the Isper, Krems, Kamp, Göllersau and the

March. Besides the Danube, only the Enns and the March are navigable

rivers. Amongst the small Alpine lakes, the Erlaufsee and the Lunzer See

are worth mentioning. Of its mineral springs, the best known are the

sulphur springs of Baden, the iodine springs of Deutsch-Altenburg, the

iron springs of Pyrawarth, and the thermal springs of Vöslau. In general

the climate, which varies with the configuration of the surface, is

moderate and healthy, although subject to rapid changes of temperature.

Although 43.4% of the total area is arable land, the soil is only of

moderate fertility and does not satisfy the wants of this

thickly-populated province. Woods occupy 34.2%, gardens and meadows 13.1%

and pastures 3.2%. Vineyards occupy 2% of the total area and produce a

good wine, specially those on the sunny slopes of the Wiener Wald.

Cattle-rearing is not well developed, but game and fish are plentiful.

Mining is only of slight importance, small quantities of coal and

iron-ore being extracted in the Alpine foothill region; graphite is found

near Mühldorf. From an industrial point of view, Lower Austria stands,

together with Bohemia and Moravia, in the front rank amongst the Austrian

provinces. The centre of its great industrial activity is the capital,

Vienna (q.v.); but in the region of the Wiener Wald up to the

Semmering, owing to its many waters, which can be transformed into motive

power, many factories are spread. The principal industries are, the

metallurgic and textile industries in all their branches, milling,

brewing and chemicals; paper, leather and silk; cloth, objets de

luxe and millinery; physical and musical instruments; sugar, tobacco

factories and foodstuffs. The very extensive commerce of the province has

also its centre in Vienna. The population of Lower Austria in 1900 was

3,100,493, which corresponds to 405 inhabitants per sq. m. It is,

therefore, the most densely populated province of Austria. According to

the language in common use, 95% of the population [v.03 p.0002]was German, 4.66%

was Czech, and the remainder was composed of Poles, Slovaks, Ruthenians,

Croatians and Italians. According to religion 92.47% of the inhabitants

were Roman Catholics; 5.07% were Jews; 2.11% were Protestants and the

remainder belonged to the Greek church. In the matter of education, Lower

Austria is one of the most advanced provinces of Austria, and 99.8% of

the children of school-going age attended school regularly in 1900. The

local diet is composed of 78 members, of which the archbishop of Vienna,

the bishop of St Pölten and the rector of the Vienna University are

members ex officio. Lower Austria sends 64 members, to the

Imperial Reichsrat at Vienna. For administrative purposes, the province

is divided into 22 districts and three towns with autonomous

municipalities: Vienna (1,662,269), the capital (since 1905 including

Floridsdorf, 36,599), Wiener-Neustadt (28,438) and Waidhofen on the Ybbs

(4447). Other principal towns are: Baden (12,447), Bruck on the Leitha

(5134), Schwechat (8241), Korneuburg (8298), Stokerau (10,213), Krems

(12,657), Mödling (15,304), Reichenau (7457), Neunkirchen (10,831), St

Pölten (14,510) and Klosterneuburg (11,595).

The original archduchy, which included Upper Austria, is the nucleus

of the Austrian empire, and the oldest possession of the house of

Habsburg in its present dominions.

See F. Umlauft, Das Erzherzogtum Österreich unter der Enns,

vol. i. of the collection Die Lander Österreich-Ungarns in Wort und

Bild (Vienna, 1881-1889, 15 vols.); Die österreichisch-ungarische

Monarchie in Wort und Bild, vol. 4. (Vienna. 1886-1902, 24 vols.); M.

Vansca, Gesch. Nieder- u. Ober-Österreichs (in Heeren's

Staatengesch., Gotha, 1905).

AUSTRIA, UPPER (Ger. Oberösterreich or Österreich ob

der Enns, "Austria above the river Enns"), an archduchy and

crown-land of Austria, bounded N. by Bohemia, W. by Bavaria, S. by

Salzburg and Styria, and E. by Lower Austria. It has an area of 4631 sq.

m. Upper Austria is divided by the Danube into two unequal parts. Its

smaller northern part is a prolongation of the southern angle of the

Bohemian forest and contains as culminating points the Plöcklstein (4510

ft.) and the Sternstein (3690 ft.). The southern part belongs to the

region of the Eastern Alps, containing the Salzkammergut and Upper

Austrian Alps, which are found principally in the district of

Salzkammergut (q.v.). To the north of these mountains, stretching

towards the Danube, is the Alpine foothill region, composed partly of

terraces and partly of swelling undulations, of which the most important

is the Hausruckwald. This is a wooded chain of mountains, with many

branches, rich in brown coal and culminating in the Göblberg (2950 ft.).

Upper Austria belongs to the watershed of the Danube, which flows through

it from west to east, and receives here on the right the Inn with the

Salzach, the Traun, the Enns with the Steyr and on its left the Great and

Little Mühl rivers. The Schwarzenberg canal between the Great Mühl and

the Moldau establishes a direct navigable route between the Danube and

the Elbe. The climate of Upper Austria, which varies according to the

altitude, is on the whole moderate; it is somewhat severe in the north,

but is mild in Salzkammergut. The population of the duchy in 1900 was

809,918, which is equivalent to 174.8 inhabitants per sq. m. It has the

greatest density of population of any of the Alpine provinces. The

inhabitants are almost exclusively of German stock and Roman Catholics.

For administrative purposes, Upper Austria is divided into two autonomous

municipalities, Linz (58,778) the capital, and Steyr (17,592) and 12

districts. Other principal towns are Wels (12,187), Ischl (9646) and

Gmunden (7126). The local diet, of which the bishop of Linz is a member

ex officio, is composed of 50 members and the duchy sends 22

members to the Reichsrat at Vienna. The soil in the valleys and on the

lower slopes of the hills is fertile, indeed 35.08% of the whole area is

arable. Agriculture is well developed and relatively large quantities of

the principal cereals are produced. Upper Austria has the largest

proportion of meadows in all Austria, 18.54%, while 2.49% is lowland and

Alpine pasturage. Of the remainder, woods occupy 34.02%, gardens 1.99%

and 4.93% is unproductive. Cattle-breeding is also in a very advanced

stage and together with the timber-trade forms a considerable resource of

the province. The principal mineral wealth of Upper Austria is salt, of

which it extracts nearly 50% of the total Austrian production. Other

important products are lignite, gypsum and a variety of valuable stones

and clays. There are about thirty mineral springs, the best known being

the salt baths of Ischl and the iodine waters at Hall. The principal

industries are the iron and metal manufactures, chiefly centred at Steyr.

Next in importance are the machine, linen, cotton and paper manufactures,

the milling, brewing and distilling industries and shipbuilding. The

principal articles of export are salt, stone, timber, live-stock, woollen

and iron wares and paper.

See Edlbacher, Landeskunde von Oberösterreich (Linz, 2nd ed.,

1883); Vansca, op. cit. in the preceding article.

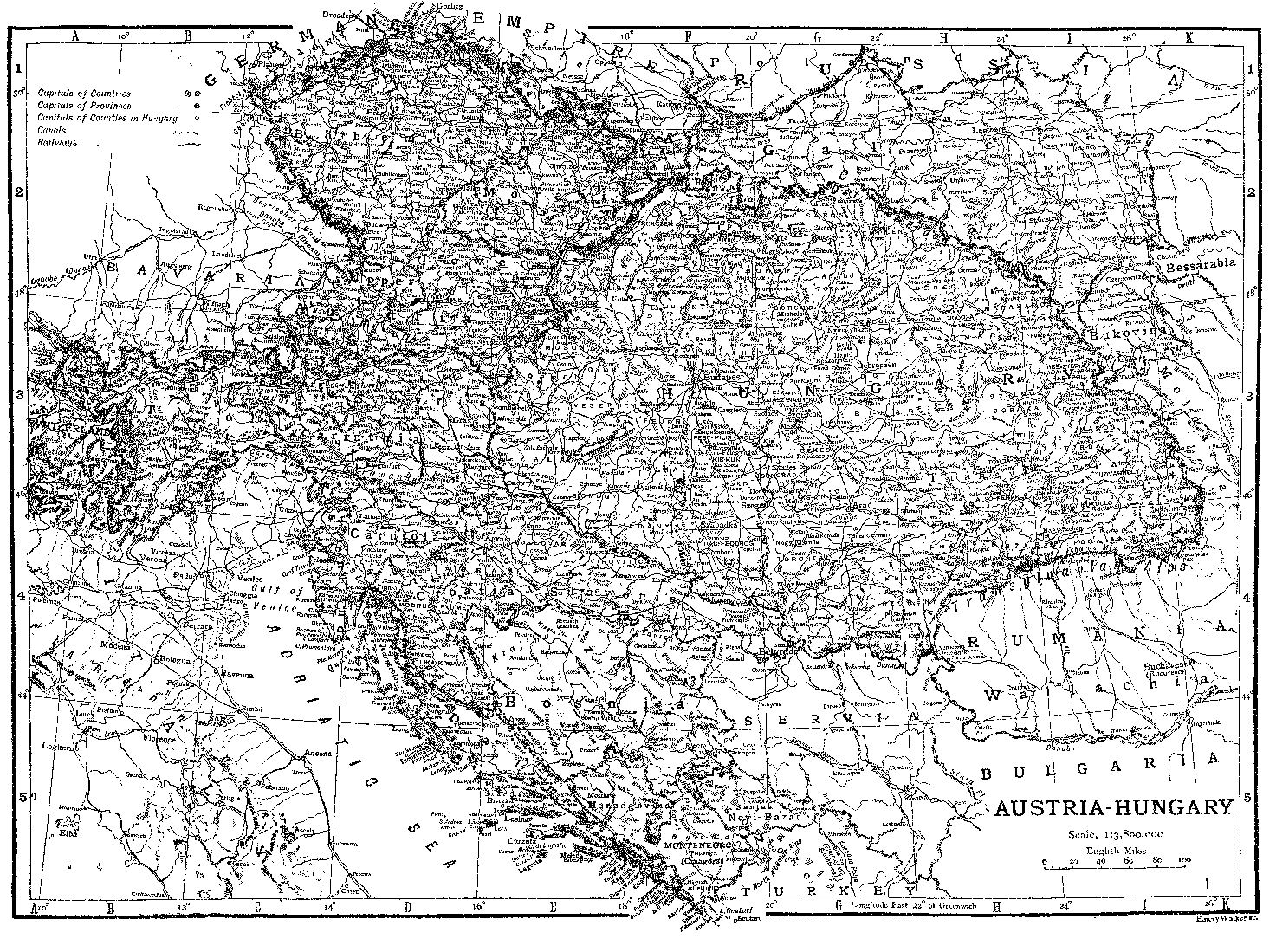

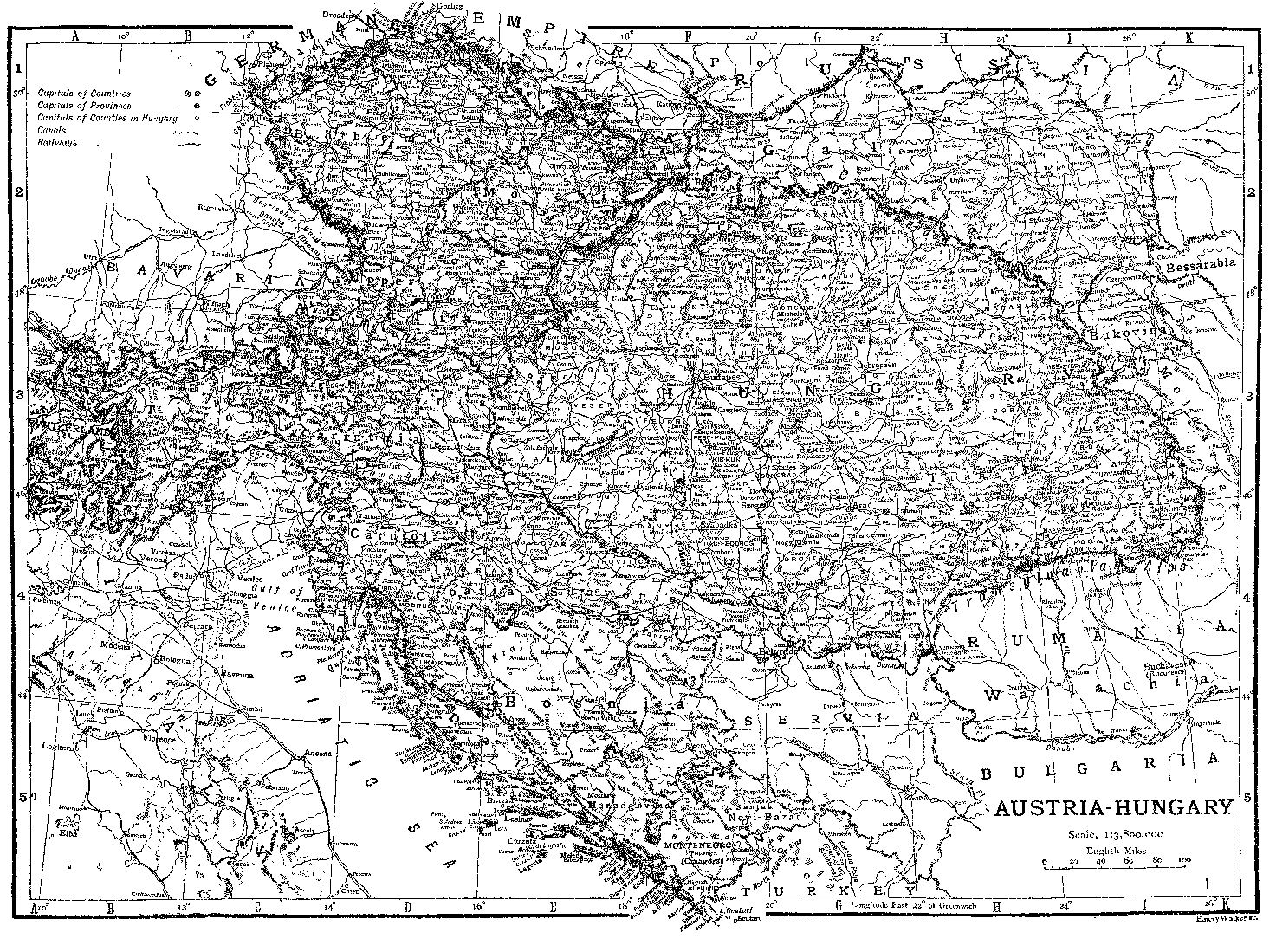

AUSTRIA-HUNGARY, or the Austro-Hungarian

Monarchy (Ger. Österreichisch-ungarische Monarchie or

Österreichisch-ungarisches Reich), the official name of a country

situated in central Europe, bounded E. by Russia and Rumania, S. by

Rumania, Servia, Turkey and Montenegro, W. by the Adriatic Sea, Italy,

Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the German Empire, and N. by the German

Empire and Russia. It occupies about the sixteenth part of the total area

of Europe, with an area (1905) of 239,977 sq. m. The monarchy consists of

two independent states: the kingdoms and lands represented in the council

of the empire (Reichsrat), unofficially called Austria

(q.v.) or Cisleithania; and the "lands of St Stephen's Crown,"

unofficially called Hungary (q.v.) or Transleithania. It received

its actual name by the diploma of the emperor Francis Joseph I. of the

14th of November 1868, replacing the name of the Austrian Empire under

which the dominions under his sceptre were formerly known. The

Austro-Hungarian monarchy is very often called unofficially the Dual

Monarchy. It had in 1901 a population of 45,405,267 inhabitants,

comprising therefore within its borders, about one-eighth of the total

population of Europe. By the Berlin Treaty of 1878 the principalities of

Bosnia and Herzegovina with an area of 19,702 sq. m., and a population

(1895) of 1,591,036 inhabitants, owning Turkey as suzerain, were placed

under the administration of Austria-Hungary, and their annexation in 1908

was recognized by the Powers in 1909, so that they became part of the

dominions of the monarchy.

Government.—The present constitution of the

Austro-Hungarian monarchy (see Austria) is based

on the Pragmatic Sanction of the emperor Charles VI., first promulgated

on the 19th of April 1713, whereby the succession to the throne is

settled in the dynasty of Habsburg-Lorraine, descending by right of

primogeniture and lineal succession to male heirs, and, in case of their

extinction, to the female line, and whereby the indissolubility and

indivisibility of the monarchy are determined; is based, further, on the

diploma of the emperor Francis Joseph I. of the 20th of October 1860,

whereby the constitutional form of government is introduced; and, lastly,

on the so-called Ausgleich or "Compromise," concluded on the 8th

of February 1867, whereby the relations between Austria and Hungary were

regulated.

The two separate states—Austria and Hungary—are completely

independent of each other, and each has its own parliament and its own

government. The unity of the monarchy is expressed in the common head of

the state, who bears the title Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of

Hungary, and in the common administration of a series of affairs, which

affect both halves of the Dual Monarchy. These are: (1) foreign affairs,

including diplomatic and consular representation abroad; (2) the army,

including the navy, but excluding the annual voting of recruits, and the

special army of each state; (3) finance in so far as it concerns joint

expenditure.

For the administration of these common affairs there are three joint

ministries: the ministry of foreign affairs and of the imperial and royal

house, the ministry of war, and the ministry of finance. It must be noted

that the authority of the joint ministers is restricted to common

affairs, and that they are not allowed to direct or exercise any

influence on affairs of government affecting separately one of the halves

of the monarchy. [v.03 p.0003]The minister of foreign affairs

conducts the international relations of the Dual Monarchy, and can

conclude international treaties. But commercial treaties, and such state

treaties as impose burdens on the state, or parts of the state, or

involve a change of territory, require the parliamentary assent of both

states. The minister of war is the head for the administration of all

military affairs, except those of the Austrian Landwehr and of the

Hungarian Honveds, which are committed to the ministries for

national defence of the two respective states. But the supreme command of

the army is vested in the monarch, who has the power to take all measures

regarding the whole army. It follows, therefore, that the total armed

power of the Dual Monarchy forms a whole under the supreme command of the

sovereign. The minister of finance has charge of the finances of common

affairs, prepares the joint budget, and administers the joint state debt.

(Till 1909 the provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina were also administered

by the joint minister of finance, excepting matters exclusively dependent

on the minister of war.) For the control of the common finances, there is

appointed a joint supreme court of accounts, which audits the accounts of

the joint ministries.

Budget.—Side by side with the budget of each state of the

Dual Monarchy, there is a common budget, which comprises the expenditure

necessary for the common affairs, namely for the conduct of foreign

affairs, for the army, and for the ministry of finance. The revenues of

the joint budget consist of the revenues of the joint ministries, the net

proceeds of the customs, and the quota, or the proportional contributions

of the two states. This quota is fixed for a period of years, and

generally coincides with the duration of the customs and commercial

treaty. Until 1897 Austria contributed 70%, and Hungary 30% of the joint

expenditure, remaining after-deduction of the common revenue. It was then

decided that from 1897 to July 1907 the quota should be 66-46/49 for

Austria, and 33-2/49 for Hungary. In 1907 Hungary's contribution was

raised to 36.4%. Of the total charges 2% is first of all debited to

Hungary on account of the incorporation with this state of the former

military frontier.

The Budget estimates for the common administration were as follows in

1905:—

|

Revenue—

|

|

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

|

£21,167

|

|

Ministry of War

|

305,907

|

|

Ministry of Finance

|

4,870

|

|

Board of Control

|

18

|

|

The Customs

|

4,780,000

|

|

Proportional contributions

|

15,650,448

|

|

|

—————

|

|

Total

|

£20,762,410

|

|

|

—————

|

|

|

|

Expenditure—

|

|

|

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

|

£485,480

|

|

Ministry of War:—

|

|

Army

|

12,679,160

|

|

Navy

|

2,306,100

|

|

Ministry of Finance

|

177,000

|

|

Board of Control

|

13,250

|

|

Extraordinary Military Expenditure

|

4,785,500

|

|

Extraordinary Military Expenditure in Bosnia

|

315,920

|

|

|

—————

|

|

Total

|

£20,762,410

|

|

|

—————

|

The following table gives in thousands sterling the joint budget for

the years 1875-1905:—

Expenditure.

|

|

1875.

|

1885.

|

1895.

|

1900.

|

1905.

|

|

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

|

396

|

368.7

|

333

|

433.4

|

493.8

|

|

Ministry of War (Army and Navy)

|

9005.4

|

10,085

|

12,539

|

13,887.5

|

18,087.7

|

|

Ministry of Finance

|

154.2

|

167.2

|

170.4

|

175

|

177.1

|

|

Supreme Court of Accounts

|

10.5

|

10.6

|

10.7

|

12.5

|

13.3

|

|

Total

|

9566.1

|

10,631.5

|

13,053.1

|

14,508.4

|

20,430.3

|

Revenue.

|

For the above Departments

|

432

|

258.2

|

260.7

|

260.3

|

331.9

|

|

Customs

|

997.4

|

402.2

|

4476

|

5202.3

|

4799.7

|

|

Proportional Contributions

|

8136.7

|

9971.1

|

8316.4

|

9045.8

|

15,650.4

|

|

Total

|

9566.1

|

10,631.5

|

13,053.1

|

14,508.4

|

20,430.3

|

Debt.—Besides the debts of each state of the Dual

Monarchy, there is a general debt, which is borne jointly by Austria and

Hungary. The following table gives in millions sterling the amount of the

general debt for the years 1875-1905:—

|

1875.

|

1885.

|

1895.

|

1900.

|

1905.

|

|

232.41

|

231.02

|

229.67

|

226.81

|

224.31

|

Delegations.—The constitutional right of voting money

applicable to the common affairs and of its political control is

exercised by the Delegations, which consist each of sixty members, chosen

for one year, one-third of them by the Austrian Herrenhaus (Upper House)

and the Hungarian Table of Magnates (Upper House), and two-thirds of them

by the Austrian and the Hungarian Houses of Representatives. The

delegations are annually summoned by the monarch alternately to Vienna

and to Budapest. Each delegation has its separate sittings, both alike

public. Their decisions are reciprocally communicated in writing, and, in

case of non-agreement, their deliberations are renewed. Should three such