Punch, or the London Charivari

Volume 104, May 27th 1893

edited by Sir Francis Burnand

AN APPEAL FOR INSPIRATION.

[Mr. Lewis Morris has been

requested to write an ode on the

approaching Royal Marriage.]

Awake my Muse, inspire your Lewis Morris

To pen an ode! to be another Horris!

"Horace" I should have written, but in place of it

You see the word—well, I'm within an ace of it.

Awake my muse! strike up! your bard inspire

To write this—"by particular desire."

Wet towels! Midnight oil! Here! Everything

That can induce the singing bard to sing.

Shake me, Ye Nine! I'm resolute, I'm bold!

Come, Inspiration, lend thy furious hold!

Morris on Pegasus! Plank money down!

I'll back myself to win the Laureate's Crown!

The Chief Secretary's

Musical Performance, with

Accompaniment.—Mr. John

Morley arrived last Friday

at Kingston. He went to

Bray. He was "accompanied"

by the Under Secretary.

Surely the Leader of the Opposition,

now at Belfast, won't

lose such a chance as this item

of news offers.

The "Water-Carnival."—Good

idea! But a very

large proportion of those whom

the show attracts would be all

the better for a Soap-and-Water

Carnival. Old Father

Thames might be considerably

improved by the process.

A RESERVED SEAT.

Mistress. "Well, James, how did you like the Show? I hope you

got a good view."

Jim. "Yes thankye, M'm; I saw it first-rate. There was room

fur Four or Five more where I was."

Mistress (surprised). "Indeed!—where was that?"

Jim. "In the Park, M'm,—up a Ches'nut

Tree."

ODDS BOBBILI!

(The Rajah of Bobbili arrived by

P.& O. at Marseilles, where he

was received by Col. Humphrey

on behalf of the Queen.)

There was a gay Rajah of Bobbili

Who felt when a steamer on wobblely,

"Delighted," says he,

"Colonel Humphrey to see,"

So they dined and they drank hobby-nobbeley.

Is the Times also among

the Punsters?—In its masterly,

or rather school-masterly,

article last Saturday, on "The

Divisions on the Home-Rule

Bill," written with the special

intention of whipping up the

Unionist absentees, the Times

said, "There is an opinion that,

with a measure so far-reaching

in its character as the

Home-Rule Bill, pairing should

be resorted to as sparingly as

possible." The eye gifted with

a three-thousand-joke-search-light

power sees the pun at

once, and reproduces it italicised,

to be read aloud, thus—"Pairing

should be resorted

to as pairingly as possible."

What shall he have who makes

a pun in the Times? Our congratulations.

Henceforth, to

the jest-detectors this new

development may prove most

interesting.

Imperial Institute Notice

at the Reception.—"Guests

must retain their wraps and

Head Coverings." Evidently

no bald men admitted.

Australian Song in

Minor Key for any Number

of Voices.—"I Know a

Bank!"

A BUSINESS LETTER.

["Marriage is daily becoming a more commercial

affair."—A Society Paper.]

Dear Fred,—Your favour of the 3rd,

Has had my very best attention,

But yet I cannot, in a word,

Accept you on the terms you mention;

Indeed, wherever you may try,

According to the last advices

You'll meet, I fear, the same reply—

"It can't be done, at current prices!"

In vain an ancient name you show,

In vain for intellect are noted,

Blue blood and brains, you surely know,

At nominal amounts are quoted;

And then, I see, you're weak enough

To offer "love, sincere, unstudied,"—

Why, Sir, with such Quixotic stuff

The market's absolutely flooded!

But—every day this fact confirms—

The time is over for romances,

And whether we can come to terms

Depends alone on your finances.

So, would you think me over-bold

If I, with deference, requested

A statement of what funds you hold?

In what securities invested?

For, candidly, in such affairs

A speedy bid your only chance is,

A boom in Yankee millionnaires

May soon result in marked advances;

With you I'd willingly be wed,

To like you well enough I'm able,

But first submit your bank-book, Fred,

To your (perhaps) devoted Mabel!

SUSPIRIA.

(By a Fogey.)

I would I were a boy!

Not for the tarts we once were fain to eat,

The penny ice, the jumble sticky-sweet,

The tip's deciduous joy—

Not; for the keen delight

Of break-neck 'scapes, the charm of getting wet,

The joy of battle (strongest when you get

Two other chaps to fight).

No! times have changed since then.

The social whirlpool has engulfed the boys;

Robb'd of their simple, hardy, rowdy joys,

They start from scratch as men.

The winners in the race!

Secure of worship, each his triumphs tells,

Weighing with faintly-praising syllables

The fairest form and face.

Once, in the mazy crush,

Ingenuous youth, half timid, and half proud,

By girlhood's pity had its claims allow'd,

And worshipp'd with a blush.

Time was when tender years

Would hug sweet sorrow to the heart, and blur

The cross-barr'd bliss of the confectioner

With crushed affection's tears.

That humbleness is sped,

The vivid blazon of self-conscious youth,

The unwilling witness to whole-hearted truth,

Ne'er troubles boyhood's head.

Now with a solemn pride,

Lord of the future's limitless expanse,

The Stoic stripling tolerates the dance

Weary, yet dignified.

Propping the mirror'd wall,

No joy of motion, no desire to please,

Thaws those high-collar'd Caryatides,

Inane, imperial.

Girls, with their collars too,

Their mannish maskings, and their unveil'd eyes,

Would feel, if girls can be surprised, surprise

Should courteous worship woo.

From their exalted place

The boys their favours dole, as seems them well,

Woman's calm tyrants, showing, truth to tell,

More tolerance than grace.

Double Riddle.—Why is a whist-player,

fast asleep after his fifth game, like one of

the latest-patented cabs? Because he can be

briefly alluded to as "Rubber Tires." (Riddle

adaptable also to exhausted manipulator in

Turkish Bath after a hard day's work.)

THE MONEY-BOXING KANGAROO.

(Knocked-Out—for the Time!)

Pity the sorrows of a poor "Old Man,"

Whose pouch is emptied of its golden store;

Whose girth seems dwindling to its shortest span,

Who needs relief, and needs it more and more.

Punch's appeal for the marsupial martyr

Is based upon an ancient nursery model;

But he will find that he has caught a Tartar,

Who hints that Punch is talking heartless twaddle.

Knocked out this round, and verily no wonder!

The Money-boxing Kangaroo is plucky:

But when a chance-blow smites the jaw like thunder,

A champion may succumb to fluke unlucky.

[pg 243]

The Australian Cricketers in their first game

Went down; but Blackham's bhoys high hopes still foster;

Duffers who think 'twill always be the same,

Reckoned without their Giffen! Just ask Glo'ster!

So our pouched pugilist, though his chance looks poor,

Will come up smiling soon, surviving failure;

And an admiring ring will shout once more,

(Pardon the Cockney rhyme!) "Advance, Australia!!!"

The Arms (and Legs) of the Isle of

Man.—At a discussion on Sunday-trading,

one day last month, there was an attempt

made to raise a question as to breach of

privilege. The Speaker, however, stopped

this at the outset, advising them that they

"hadn't a leg to stand upon." Very little

advantage in having three legs on such an

occasion. The odd part of these Manx-men's

legs is that they are their arms. It

was originally selected as pictorially exhibiting

the innocent character of the Manx

Islanders. For their greatest enemy must

own that "the strange device" of the three

legs is utterly 'armless.

THE END OF THE DROUGHT.

(By a Cab-horse.)

Don't talk to us in praise of rain!

When we are slipping once again;

This beastly shower

Has made wood-pavements thick with slime.

Suppose you try another time,

By mile or hour;

See how you'd like to trot and trip,

To stop and stagger, slide and slip,

Pulled up affrighted,

Urged madly on, then checked once more,

Whilst from some omnibus's door

Some lout alighted.

You would not find much cause to laugh,

Like us, you would not care for chaff

Were you such draggers;

Your shoes would soon be off, or worn,

You'd get, what we don't often, corn,

And end with staggers.

You'd long to be put out to grass,

Infrequent so far with your class—

Nebuchadnezzar

Was quite an isolated case—

You would be tired of life's long-race;

Slaves who in Fez are,

On the Sahara could not bear

Such toil as falleth to our share,

For death would free them.

You say the farmer wants the wet

For meadows; pray do not forget

We never see them.

Philanthropists, why don't you walk?

Of slaves' hard lives you blandly talk,

Like "Uncle Tom"—nay,

You think what your own horses do,

But we—there, get along with you!

Allez vous promener!

Change Its Name!—An estate in the Island

of Fowlness, Essex, of 382 acres, was put up

to auction last week, and, according to the

Daily News there was only one bid at a little

short of eight pounds per acre. "The

property was withdrawn." This step was

judicious and correct. It was an act of fairness

to Fowlness. But then, does it sound

nice for anyone to say, "I'm living in the

midst of Fowlness"? It may be a Paradise,

but it doesn't sound like it.

MISUNDERSTOOD.

Little Girl. "Oh, Mamma, I'm so glad you had such a pleasant Dinner

at the

Vicarage. And—who took you in?"

Mother. "Who took Me in, dear Child! No man ever took

Me in. Not even

your dear Father; for when I married him, I knew all his Faults!"

The Mellor of the C.

Air—"The Miller of the Dee."

There was a jolly Mellor,

The Chairman of Com-mittee;

They worried him from noon till night—

"No lark is this!" sighed he;

And this the burden of his song

For ever seems to be,

"I care for e-ve-rybody,—why

Does nobody care for me?"

Vestries, Please Copy!—Sir Richard

Temple has announced a reduction of the

School-Board Rate by a farthing in the pound.

May he never become a ruined Temple owing

to such economies! The Rate-payers will be

grateful for even a fraction of a penny, so long

as it is not an improper fraction. This sort

of saving is far better than squabbling over

Theology. Says Mr. Punch to Schoolboardmen,

"Rate the public lightly, and don't

rate each other at all!"

New Sarum Version of "Derry Down."—"Derry

up! up! Up, Derry, up!"

Poor Letter H.

Scene—Undergraduate's Room in St. Boniface's

College, Oxford. Breakfast time.

Servant. I see, Sir, you don't like the

butter. Summer hair will get to it this 'ot

weather.

Testy Undergrad. Confound it, Luker,

I don't mind the—ahem—hair, but kindly

let me have my butter bald the next time!

[He had swallowed a hair.

Under the Great Seal is a new work

by Mr. Joseph Hatton. The Busy Baron

hath not yet had time to read it, but,

from answers given to his "fishing interrogatories,"

he gathers that international

piscatorial questions are ably discussed in

the work. Joseph has lost a chance in not

dedicating it to Seale-Hayne, M.P., and,

instead of being brought out by Hutchinson

& Co., it ought to have been published

by Seeley. However, even Josephus

Hattonensis can't think of everything,

though he does write on most things.

AT THE NEW GALLERY.

In the Central Hall.

A Potential Purchaser (meeting a friend). Ha—just come in to

take a look round, eh? So did I. Fact is—(with a mixture of

importance and apology) I rather thought of buying a picture here,

if I see anything that takes my fancy—y' know.

His Friend (impressed). Not many who can afford to throw money

away on pictures, these hard times!

The P. P. (anxious to disclaim any idea of recklessness). Just the

time to pick 'em up cheap, if you know what you're about. And

you see, we've had the drawing-room done up, and the wife wants

something to fill up the space over her writing-table, between the

fireplace and one of the windows. She was to have met me here, but

she couldn't turn up, so I shall have to do it all myself—unless

you'll come and help me through with it?

His Friend. Oh, if I can be of any use—What sort of thing do

you want?

The P. P. Well, that's the difficulty. She says it must match

the new paper. I've brought a bit in my pocket with me.

His Friend. Then you can't

go very far wrong!

The P. P. I don't know. It's

a sort of paper that—here, I'd

better show it you. (He produces

a sample of fiery and

untamed colour.) That'll give

you an idea of it.

His Friend (inspecting it

dubiously). Um—yes. I see

you'll have to be careful.

The P. P. Careful, my dear

fellow! I assure you I've been

all through the Academy, and

there wasn't a thing there that

could stand it for a single

moment—not even the R.A.'s!

[They enter the West Room.

In the West Room.

An Insipid Young Person

(before Mr. Tadema's "Unconscious

Rivals"). Yes, that's

marble, isn't it?

[Smiles with pleasure at her own penetration.

Her Mother (cautiously). I

imagine so. (She refers to

Catalogue.) Oh! I see it's a

Tadema, so of course it's marble.

He's the great man for it, you

know!

First Painter (who had nothing

ready to send in this year).

H'm, yes. Can't say I care

about the way he's placed his

azalea. I should have kept it

more to the left, myself.

Second Painter (who sent in,

but is not exhibiting). Composition

wants bringing together,

and the colour scheme is a little

unfortunate, but—(generously)

I shouldn't call it altogether

bad.

First Painter (more grudgingly).

Oh, you can see what

he was trying for—only—well, it's not the way I should have

gone about it.

[They pass on tolerantly.

"There, you see—knocks it all to pieces at once!"

The I. Y. P. Can you make this picture out, Mamma? "The

Track of the Strayed?" The Strayed what?

Her Mother. Sheep, I should suppose, my dear—but it would

have been more satisfactory certainly if the animal had been shown

in the picture.

The I. Y. P. Yes, ever so much. Oh, here's a portrait of

Mr. Gladstone reading the Lessons in Hawarden Church. I do

like that—don't you?

Her Mother. I'm not sure that I do, my dear. I wonder they

permitted the Artist to paint any portrait—even Mr.

Gladstone's—during

service!

The P. P. (before another canvas). Now that's about the size

I want; but I'm not sure that my wife would quite care about the

subject.

His Friend. I'm rather fond of these allegorical affairs myself—for

a drawing-room, you know.

The P. P. Well, I'll just try the paper against it. (He applies

the test, and shakes his head.) "There, you see—knocks it all to

pieces at once!"

His Friend. I was afraid it would, y' know. How will this do

you—"A Naiad"?

The P. P. I shouldn't object to it myself, but there's the Wife

to be considered—and then, a Naiad—eh?

His friend. She's half in the water.

The P. P. Yes, but then—those lily-leaves in her hair, you

know, and—and coming up all dripping like that—no, it's hardly

worth while bringing out the paper again!

The I. Y. P. Isn't this queer—"Neptune's Horses"?—They

can't be intended to represent waves, surely!

Her Mother. It's impossible to tell what the Painter intended,

my dear, but I never saw waves so like horses as that.

In the North Room.

The I. Y. P. "Cain's First Crime." Why, he's only feeding a

stork! I don't see any crime in that.

Her Mother. He's giving it a live lizard, my dear.

The I. Y. P. But storks like live lizards, don't they? And

Adam

and Eve are looking on, and

don't seem to mind.

Her Mother. I expect that's

the moral of it. If they'd taken

it away from him, and punished

him at the time, he wouldn't

have turned out so badly as he

did—but it's too late to think

of that now!

A Matter-of-fact Person

(behind). I wonder, now,

where he got his authority

for that incident. It's new

to me.

In the Balcony.

The Mother of the I. Y. P.

Oh, Caroline, you've got the

Catalogue—just see what No.

288 is, there's a dear. It seems

to be a country-house, and

they're having dinner in the

garden, and some of the guests

have come late, and without

dressing, and there's the hostess

telling them it's of no consequence.

What's the title—"The

Uninvited Guests," or

"Putting them at their Ease,"

or what?

The I. Y. P. It only says,

"The Rose-Garden at Ashridge

(containing portraits of the

Earls of Pembroke and

Brownlow, the Countesses

of ——").

[She reads out the list to the end.

Her Mother. What a nice

picture! Though one would

have thought such smart folks

wouldn't have come to dinner

in riding-boots, and shawls, and

things—but of course they can

afford to be less particular.

And the dessert is beautifully

done!

In the South Room.

The I. Y. P. Why, here are "Neptune's Horses" again! Don't

you remember we saw a picture of them before? But I like this

better, because here you get Neptune and his chariot.

Her Mother. He's made his horses a little too like fish, for my

taste.

The I. Y. P. I suppose they were a sort of fish—and after all,

one

isn't expected to believe in all that nowadays, is one? So it doesn't

really matter.

First Horsey Man. Tell you what, Old Neptune'll come to

awful grief with that turn-out of his in another second.

Second H. M. Rather—regular bolt—and no ribbons to hold 'em

by, either!

First H. M. Rummy idea, having cockleshells on the traces.

Second H. M. Oh, I don't know—one of the Hussar regiments

has 'em.

First H. M. Ah, so they have. I suppose that's where he got the

idea.

[They go out, feeling that the picture is satisfactorily accounted for.

The P. P. (before a small

canvas). Yes, this is the right

thing at last. The paper

doesn't seem to put it out in

the least, and the sort of subject,

you know, that no one

can object to. I've quite

fallen in love with it. I don't

care what it costs—I positively

must have it. I'm sure the wife

will be as fond of it as I am.

I only hope it's not sold—here,

let's go and see.

[They go.

At the Secretary's Table.

The P. P. (turning over the

priced Catalogue). Ah, here

it is! It's unsold—it's

marked down at—(his face

falls)—eleven—eleven—that's

rather over my limit. (To his

Friend.) Do you mind waiting

while I try the paper on

it once more? (His Friend

consents; the P. P. returning,

after an interval.) No,

I had my doubts from the beginning—it

won't do, after all!

His Friend. But I thought

you said the paper didn't put

it out?

The P. P. It doesn't—but

the picture takes all the shine

out of the paper.

His Friend. I suppose you

couldn't very well change the

paper—eh?

The P. P. Change the

paper?—when it's only been

up a week, and cost seven-and-six

the piece! My dear

fellow, what are you talking

about? No, no—I must see if

I can't get a picture to match

it at Maple's, that's all.

His Friend (vaguely). Yes,

I suppose they understand all

that sort of thing there.

[They go out, relieved at having arrived at a decision.

CARNIVOROUS.

(On Hospitable Thoughts intent.)

"Oh, they're too many to have to Eat all together, Papa!

Let's knock off the Children for Tea."

"Yes; and we can do with the Father and Mother for Dinner,

you know!"

SHAKSPEARE ON ULSTER.

To Mr. Punch, Sirr,—You're

a patriot, divil a less.

Is it fair, I ask you, Sirr, is

it fair to quote the Universal

Bard against us Ulster, et ne

plus Ulster, Loyalists? Yet

this is the line which a man

who used to call himself "a

friend of mine" sends me, and

he puts a drawing with it,

which I can't, and won't reproduce,

representing a moon

up in the sky, labelled "Home

Rule," and a pack of wolves

(a pack of idiots, for all

they're like wolves, for that

matter), on which he writes

"Ulster," with their mouths

open, looking up at it. And

this, he says, is an illustration

of a line in Shakspeare,

"The howling of Irish wolves

against the moon,"

which you'll find in As You

Like It (whether you like it

or not), Act V., Sc. 2. If the

O'Chamberlain, or the

O'Saunderson, or any of 'em,

can make use of this, they're

welcome to it.

Yours,

A Pip of the Old Orange.

Hook-y Sailor.—"Inauguration

of a New Service to

the Continent vià Harwich

and the Hook of Holland."

This sounds as if it ought to

catch on. Is the Hook of

Holland any relation to the

Theodore Hook family of

England? Were that eminent

wit now alive, he would be

the first to ask such a question.

The route sounds a

pleasant one. Advice to Tourists,—Keep

your Eye on the

Hook.

A CIVIL NOTE FOR THE MILITARY.

My Dear Mr. Punch,—I observe that in a preliminary notice

that has been sent round to the Press by the Executive Council (I

suppose that that is the proper title of the Governing Body of the

forthcoming Royal Military Tournament), it is said that there is

likely to be some novelty in the mimic warfare known as the Combined

Display of all Arms. The circular informs those whom it may

concern, that "it is intended that, so far as space will allow, the

scene shall be that of one of the more recent conflicts in which

British troops were actually engaged, and special information from

those present on such occasions has been invited, so that the result

is likely to be of more than ordinary interest."

Quite so. I call your particular attention to the last few words in

the above sentence, in which reference is made to "the special

information from those present on such occasions." I thought the idea

so good, that I immediately prepared a scheme for the adoption of

the Royal Military Tournament, founded upon my acquaintance

with the manners and customs of the English army when at

Islington and elsewhere. I give it for what it is worth—not much,

but (to quote the once popular song) "better than nothing at all."

Rough Idea.

A dozen Infantry privates saunter leisurely into their places, half-way

across the arena, and await events.

Enter Bridging Battalion, Royal Engineers. They bridge over an

old cloth river. The dozen Infantry men wait until the erection is

completed, and then fire a volley. The Sappers return the compliment.

No one hurt, and the dozen retire to the tower-like gateway

in the background. The Artillery at this point rush in and trot over

the newly-erected bridge. They then fire in the direction of the

dozen heroes, but without any apparent result.

Grand charge of Colonial Cavalry, with and without additional

men. They act as Mounted Infantry. They are fired upon—in a

half-hearted sort of way—by the dozen of Infantry seeking shelter

in the gateway. The fire seems to agree with them.

Enter an Ambulance Corps to pick up one of the colonists who has

obligingly been wounded by the blank cartridges of the dozen

Infantry.

Sudden appearance of the strength of the entire company. The

gateway is stormed, and the dozen Infantry men are overpowered.

Music on the band—"Rule Britannia!" and the National Anthem.

Great cheering while some one waves the Union Jack. End of the

performances.

There, my dear Mr. Punch, that is what I have sent to the

"powers that are" at Islington. Whether it has been accepted or

rejected I do not know. You will be able to see for yourself when

the proper time arrives.

But then, I can assure you, my sketch is exactly like the real

thing. It is not unsuggestive of the Battle of Waterloo, the siege of

Sebastopol, or the taking of Pekin. This is my "special information,

as one present on such occasions," and it is heartily at the service of

the Executive. To be worthy of my title, I would beg you to send

me, say, a fiver, or even a sov, or (if that is too much) a dollar.

I do not ask for the money as a gift, but as a loan. I prefer the

latter to the former, although a long experience has taught me that

gift and loan have much the same meaning.

Yours truly, A Very Old Soldier.

Inaudible Proceedings at the Hotel Victoria.—We have had

"The Funny Frenchman" over here, at the Albambra, and now we

have "The Calculating Frenchman," M. Jacques Inaudi, who, last

week, at a séance, exhibited his marvellous powers of addition,

multiplication, subtraction, and division. It is an error to suppose

that he was educated for the French Navy, and has been appointed

to a ship, which he was to have adorned as a "wonderful Figure-head."

By the side of this Figure-head the "Calculating Buoy"

would have been quite at sea.

DOWN A PEG.

Mr. Gifted Hopkins (Minor Poet, Essayist, Critic, Golfer, Fin-de-Siècle Idol,

&c.). "Oh, Mrs. Smart—a—I've Been thinking, for

the last Twenty Minutes, of something to say to you!"

Mrs. Smart (cheerfully). "Please go on Thinking, Mr. Hopkins,—and

I'll go on Talking to Professor Brayne in the

meantime!"

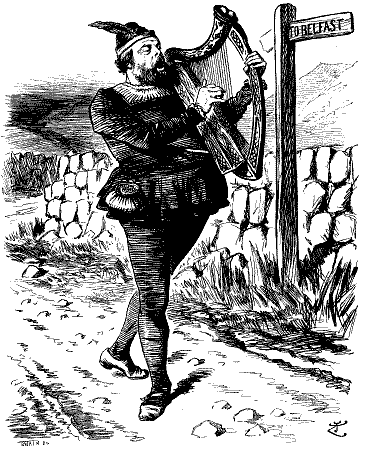

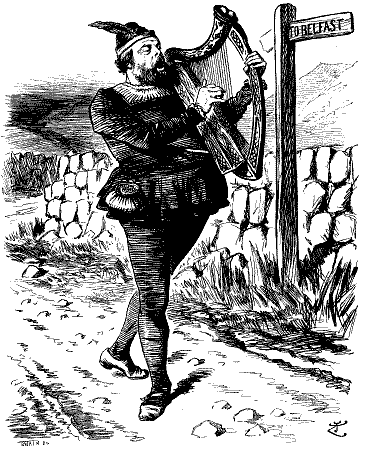

THE MINSTREL BOY.

(Latest Ulsterical Version.)

The Minstrel-boy to the war is gone,

By the Belfast road he's coming;

His Party sword he has girded on

And his wild harp loud he's thrumming.

"Land of bulls!" said the warrior bard,

"Though Gladstone's gang betrays thee,

One sword, at least, thy rights shall guard,

One faithful harp shall praise thee!"

The Minstrel's loud—though a little late;

What he hopes to gain some wonder;

But he swears that harp shall preserve the State,

Which his foes would rend asunder.

He shouts, "Home Rule shall not sully thee,

Ulster, thou soul of bravery!

I'll harp wild war, aye, from sea to sea,

Ere the Loyalists stoop to slavery!"

ENCORE VERSE.

(For use in Clubs and other places where men—and

minstrels—are confidential.)

The Minstrel's hot, and a trifle tired,

For his Whitsun task is a torrid one;

Such holiday-fervour must be admired,

But the precedent's rather a horrid one.

E'en Minstrel-boys of Ulsterical zeal,

Might now and then like a jolly-day;

And the brave bard's harp, and the warrior's steel,

Take, together, occasional holiday.

A WYLDE VADE MECUM.

(By Professor H-xl-y.)

Question. What is rest?

Answer. Unperceived activity.

Q. Which is the best way of keeping

awake?

A. By falling off to sleep.

Q. What is sleep?

A. Concealed consciousness.

Q. What is strength?

A. Weakness in excess.

Q. What is pessimism?

A. Optimism developed to its utmost possibilities.

Q. What are possibilities?

A. Impossibilities carried into action.

Q. What is selfishness?

A. Pity in the concrete.

Q. What is the summit of civilisation?

A. The commencement of barbarism.

Q. What is nature?

A. Art in its initial form.

Q. What is the survival of the fittest?

A. The Romanes Lecture.

Q. What was its comparative commencement?

A. Mr. Gladstone.

Q. And what has been its absolute end?

A. Positive ... bosh.

"The World's Fair."—Yes, so it is,

perhaps, occasionally, to some people; but

"The World's Unfair" to those on whom it

chooses to sit in judgment.

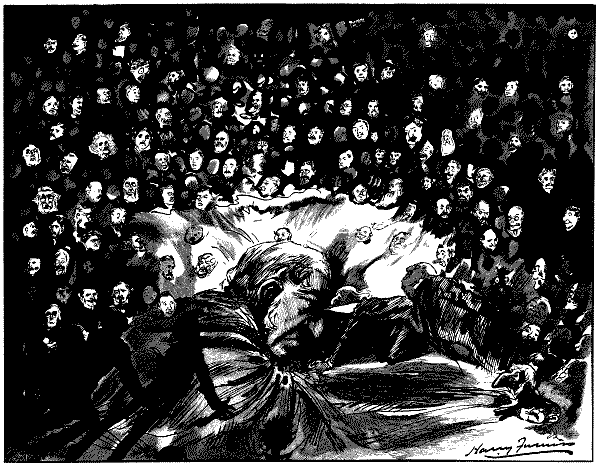

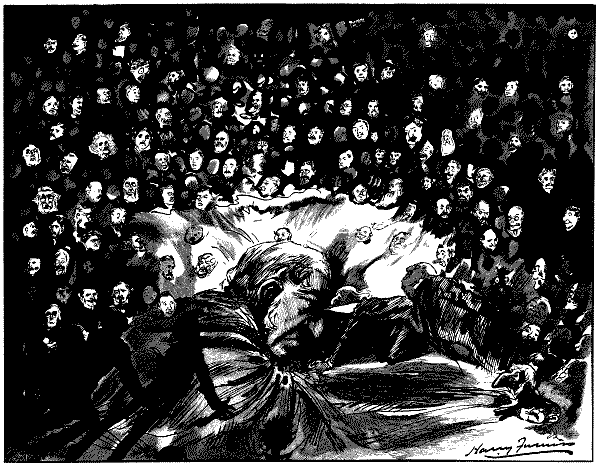

MANNERS.

[Some indignation has been expressed at the

manners of many of the "well-dressed mob" at

the Prince of Wales's Reception at the Imperial

Institute on Wednesday night last, manners displayed

in rudely "mobbing" the Royal party, and

hissing, hooting, and shouting "Traitor!" at

Mr. Gladstone, one of the Prince's guests.]

Eh? Indignation? Why such passion waste?

Gladstoneophobia has destroyed Good Taste;

And rowdy rudeness does not shock, but please,

"The mob of gentlemen who hoot with ease.

As for the ladies, bless their angry hearts!

They've Primrosed into playing fish-wife parts;

And now 'tis one of Patriotism's tests

That you should hiss and hoot your fellow-guests.

Should they dare don a rival party vesture;

Billingsgate rhetoric and Borough gesture

Invade the (party) precincts of Mayfair—

To express the vulgar wrath now raging there.

We are Mob-ruled indeed—when Courtly Nob

Apes, near his Prince, the manners of the Mob!

The hoot is owlish; there are just two things

That hiss—one venom-fanged, one graced with wings.

Anserine or serpentine, ye well-dressed rowdies?

Dainty-draped dames, or duffel-skirted dowdies,

They who in rudeness thus their spite would slake,

Have plainly head of goose, and heart of snake!

So why indulge in indignation blind

'Gainst those who hiss or hoot—after their kind?

"THE MINSTREL BOY."

Lord S-l-sb-ry (sings). "I'LL HARP WILD WAR, AYE, FROM SEA TO

SEA,

ERE THE LOYALISTS STOOP TO SLAVERY!"

"O SINO SAN!"

A Truthful Japanese Idyll.

O Sino San! O Sino San! Who waketh me at morn!

Why is it that I feel of thee unutterable scorn?

When I behold thy greasy poll and little piggy eyes,

I fear that they have told of thee unwarrantable lies!

They told me when I wandered forth to seek thee in Japan,

That I should find a priceless girl, too beautiful for man.

They told me of thy cherry cheeks, thy hair of night-dark sable,

And how you squatted on the floor—the Japanese for table;

They gushed about your merry ways, your manners without flaw,

In thee, the girl idealised, you little fraud, we saw.

But now in wind-swept bleak Japan as our sore throats we muffle,

We see thy senseless pudding face and irritating shuffle;

As you go slopping thro' the streets of your foul-smelling city,

You're far too common to be rare, too brainless to be witty.

Your senseless, everlasting grin, your squatting monkey shape,

Proclaim your Ma marsupial, your ancestor an ape!

A curio they promised us to drive a lover crazy,

With little soft canoodling ways, and sweetness of a daisy.

We read of thee in tea-house neat, in cherry-blossomed pages,

But find a girl of gin-saloon and Yoshiwara cages.

You lure the European on, admire his rings and collars,

But never really love his lips, invariably his dollars;

We'd all forgive thy grin, guffaw, and rancid-smelling tresses,

If we could trace thy fraud, O San, in half-a-dozen guesses.

It's lasted long, it's lasted strong, it cannot last much longer,

For if the crank be competent, my common sense is stronger.

The English woman flashes scorn from all her comely features,

To be compared by any man with such "disgusting creatures."

And all the fair Americans, who roam the wide world over,

Will trample down this windy chaff and Japaneesy clover.

'Tis not thy fault, O Sino San—we find the truth and strike it,

Farewell, thou Audrey of the East—grin on then "As you Like It!"

But never more by writer bold be canonised or sainted,

Deluded Doll! O Sino San, you're blacker than you're painted!

OPERATIC NOTES.

Monday, May 15.—First Night of Italian-Opera Season no longer

exclusively Italian. A great deal, though not everything, in a good

start, so Sir Druriolanus leads off with Warbling Wagner's

Lohengrin, Signor Vignas for first time being White Knight.

Crowded House at once takes to Vignas; applauds, and recalls him

to bow before the curtain. So, as the now popular song might

have it,

"Tenor came and made us a bow-wow!"

Madame Melba good as ever as Elsa, and Mlle.

Meisslinger most

dramatic as Somebody Elser, i.e., Ortruda, the Intruder. Mons.

Dufriche's style is exactly suited to the light and airy part of

Federico

di Telramondo, while Castelmary is quite the gay Enrico.

Treat

to see Vaschetti as smiling Herald, with a lot to say for somebody

else,

and pleasant to note that the last person in the dramatis personæ

included

in the cast of the Opera is "Conductor, Signor Mancinelli,"

who beats time, winning easily. Bevignani conducts National

Anthem, and all conduct themselves loyally on the occasion.

Delightful, in Lohengrin, Act II., to observe how four players of

trumps, each with one trump in his hand,—quite a pleasant whist

party—(have they the other trumps up their sleeves?)—arouse the

guests in the early morning, and marvellous is the rapidity with

which all the gentlemen sleeping in the Castle are up and dressed

in full armour, freshly burnished,—"gents suit complete,"—within

the space of a couple of minutes!

Signor Vignas as Turiddu,—so

called because he tells

Lola, "I should like Turid-you

of your husband."

But he didn't.

General excellence of performance greatly assisted by Duke of Teck

enthusiastically beating time with his dexter

band. Such auxiliary conducting must be

of unspeakable service to Signor Mancinelli.

Tuesday Night.—Orfeo, with Giulia

Ravogli charming as ever in her representation

of "Orpheus with his loot,"—his

"loot" being Eurydice, who had become

the private property of that infernal monarch

Pluto. Welcome to Mlle. Bauermeister

as the Meister of Cupid's Bower,

Cupid himself. Cavalleria Rusticana to

follow, with Madame Calvé's grand impersonation

of the simple and sad Santuzza.

Notably good is Vignas as the Rustic Swell,

with the comic-chorus name of Turiddu.

Beautiful intermezzo heartily encored. The

thanks of Signors Bevignani and Mancinelli

again due to the dexterous assistance

rendered to them by the Duke of Teck, who

is evidently well up in the Teck-nique of

the musical craft. Crowded House. Forecast

of season, full of promise and performance.

Thursday.—Carmen. Always "good

Bizet-ness." But on this occasion Madame

Calvé being indisposed, Mlle. Sigrid

Arnoldson appears as heroine. A most captivating

Carmen, but so deftly does she

dissemble her wickedness that the audience

do not realise how heartless is this artful

little cigarette-maker. Mons. Alvarez a fine

Don José. The premières danseuses lively and picturesque in Act

II.,

with dresses long and dance short; but in Last Act, when reverse

of this is the case, a pretty general feeling that skirts might have

been longer, and dance shorter. Chorus and Orchestra all that could

be desired; absence of the musical Duke much regretted.

Santuzza, Madame Calvé. Grand tragédienne:

gloomy as an Operatic Calvé-nist.

Friday.—First, Gounod's charming burletta of Philemon et

Baucis.

Mlle. Sigrid Arnoldson

charming and childlike as

Baucis—evidently the

classic original of Bo-peep—and

Mons. Plançon

excellent as Jupiter

Amans. At first afraid

lest crowded house had

expended all its enthusiasm

before quarter past

ten, when the event of

the evening was to come

off. "Not a bit of it,"

says Sir Druriolanus,

who knows his operatic public; "they've just warmed up for

Leoncavallo's Pagliacci. Leoncavallo," he continues,

"is the

composer for my money; and my advice is, Lay-on-cavallo's

Pagliacci." So saying, the Musical Manager lightly touches his

nasal organ with the index finger of his right hand, and, at the

same time "winking the other eye," he marches in a procession of

one down the lobby and disappears.

Great as is the success to-night of new Opera, I feel sure that

Cavalleria, with its simple story, and its marvellous intermezzo,

is

still at the head of the poll. Yet is Pagliacci melodious and dramatic.

Madame Melba at her best in Nedda, and the dramatic power,

specially

of Signor de Lucia as Canio and of Mons. Ancona as

Tonio, would

have carried the piece, as a piece, even without the musical setting.

To-night De Lucia shows himself a great actor. There were encores

in plenty. Ancona Tonio interrupts the overture in order to sing a

prologue. This he does admirably, both vocally and histrionically. But

cui bono? It is as pointless as is nowadays the prologue of

Christopher

Sly to the Taming of the Shrew. It seems as if Leoncavallo

said to himself, "Mascagni gave 'em a novelty in his intermezzo;

I'll give 'em something new in the shape of a prologue." Pagliacci

and Cavalleria will assist each other, and Sir Druriolanus is

fortunate

in being able to run two winners. The new Opera is

admirably rendered in every respect, and when Mr. Richard Green,

as the gallant young farmer, is matured—that is, has less of the

Green about him and more of the ripeness of artistic perfection—there

will not be a single fault to find with the representation.

To-night second Opera didn't end till just on twelve. Too late; but

the hospitable Rule's in Maiden Lane is open to exceptions for half

an hour or so, and, "after the Opera is over," a little supper chez

Bayliss is a B(ay)lissful idea.

Saturday.—Faust to finish. Melba as Marguerite. First

week

augurs well for the season.

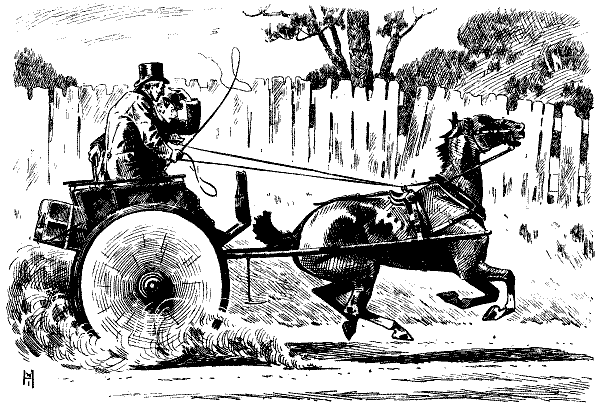

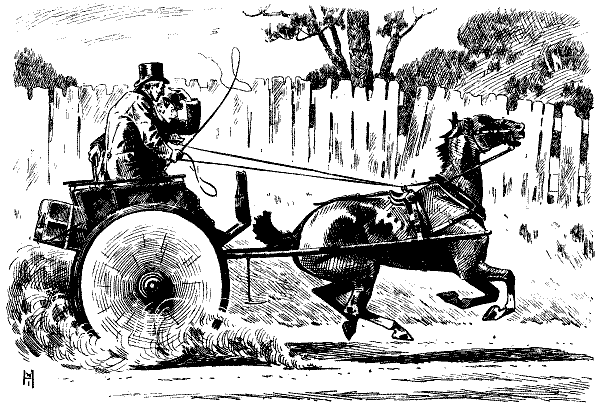

DELIGHTFUL!

Smithson, having read and heard much of the pleasures of a Driving Tour,

determines to indulge in that luxury during his Whitsuntide Holidays.

He therefore engages a Trap, with a Horse that can "get over the ground," and

securing the services of an experienced Driver, he sets forth.

Smithson. "A—a—isn't he—a—a—hadn't I better help you to Pull at

him?"

Driver. "Pull at 'im? Why yer'd set 'im crazed! Jist you let me keep

'is 'Ead straight. Lor bless yer, there

ain't no cause to be affeared, as long as we don't meet nothing, and the Gates

ain't shut at Splinterbone Crossing,

jist round the Bend!"

THE LITIGANTS VADE MECUM.

Q. What is your opinion about Chancery?

A. That, thanks to work being given to Solicitors in preference to

Barristers, litigation is more expensive in that branch of the science

than in any other.

Q. How comes it that this should be so?

A. A Barrister is forced to do his best for his client, but a Solicitor

is not. As a rule the Solicitor deputes to his Chief Clerk if he has one,

or somebody in the office if he has not, the duties of conducting a

suit through Chambers.

Q. What is the practical result of this arrangement?

A. That a suit when it once gets into Chambers takes a precious

long time in coming out.

Q. But making allowance for these little drawbacks, what is your

opinion of the Law in England?

A. That emphatically it consists of the best forensic regulations in

the universe.

A New Clause in the Home-Rule Bill.—Instead of a Parliament

in Dublin, let the Governing Body be called "A Diet," as it

is in Bohemia. There would be a First House, to be called the

"High Diet," and a Second House, to be called "Short Commons, or

Low Diet." There would be no "Parliamentary Rules," but everything

would be ordered according to a "Dietary." Perhaps

Dr. Robson Roose might be induced to take a leading part in

suggesting some of these arrangements. The "Orders of the Day"

would be "Prescriptions," the Bills "Dinner-Bills," or "Menus."

A Chairman, not a Speaker, would preside, and the subordinates—such

as Clerks, Sergeant-at-Arms, and Assistants—would be

Stewards, Head Waiters, and other Waiters. Prayers would be

said by "The Ordinary."

Odds in favour of Australian Cricketing Team—"Giffen" and

taken.

ESSENCE OF PARLIAMENT.

EXTRACTED FROM THE DIARY OF TOBY, M.P.

Home of Commons, Monday, May 15.—Mr. G. reminded of

advance of time by appearance on Parliamentary scene of new generations.

All remember when Joey C. arrived from Birmingham,

and have watched his meteoric flight from level of Provincial

Mayor to loftiest height of Parliamentary position. Only the other

week Mr. G. was paying well-deserved compliment to a younger

Chamberlain making his maiden speech; to-day he has a kindly,

fatherly word of friendly recognition of maiden speech of youngest

Cavendish. No mere compliment this, extorted by old associations

and personal predilections. Young Victor went about his work in

style reminiscent of middle-aged Hartington. Abstained from

oratorical effort. Neither exordium nor peroration. Got some

business in hand, and plodded on till it was finished. Modest mien,

simple, unaffected manner, instantly won friendly attention of

crowded House.

"Ay de mi! Toby," said Mr. G. "These things make me

think I'm not so young as I was."

"Younger Sir," I said. "Pup and dog, I've known you twenty

years; heard most of your speeches in that time; honestly declare

that for lightness of touch, swiftness of attack, wariness of defence,

not to speak of eloquence, I've never heard you excel some of your

speeches this Session."

"Well, well, Toby," said Mr. G., blushing in fashion never

learned by youth of to-day, "that's due to your too friendly way

of looking at things. What I was about to say is, that ever since

I entered public life I have always known a Cavendish to the fore.

Ministries may rise and fall; the Cavendishes remain. Curious

thing is they have not—at least in recent times—personally a

passion for politics, as Pitt had, or such as, in some degree,

influences

me. They would, if they had their own way, be out of it.

THE CHAIRMAN OF COMMITTEE'S HOLIDAY DREAM.

Victor, or Vig-Tory-ish,

Cavendish.

In the Spring Unionist Time

of his Youth.

But the Cavendishes have had their place in English public life

throughout the Century, and, it being their duty to fill it, they fill it.

Young Victor's speech on Friday night carried me back over space

of thirty-four years. I remember another Cavendish coming out.

He moved resolution which

defeated Derby's Government

in 1859. I remember the difficulty

we had in bringing him

up to the scratch. It was

Bright who finally succeeded.

Bright always had great

opinion of Hartington's

ability, a view, as we have

seen, amply justified. A great

deal has happened since 1859,

and now here's another

Cavendish moving another

Amendment, and, oddly enough"—here

Mr. G.'s face wrinkled into smile of

delighted humour—"it's ME who would

be turned out of office if the Amendment

were carried."

Being thus in melting mood, Mr. G.

suddenly turned upon inoffensive Jesse

Collings, who had been saying a few

words, and almost literally rent him into,

fragments. Scarcely anything left of

him but benevolent though feeble smile.

Business Done.—Very little in Committee

on Home-Rule Bill.

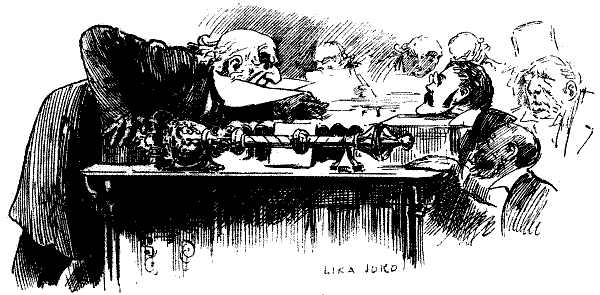

Tuesday Night.—Ambrose, Q.C.,

roused at last. House known him for

eight years; only to-night learned that

it has been cherishing upon its bosom a

sleeping volcano. Following fortunes

of Conservative leaders, Ambrose has

crossed and re-crossed floor, always

taking up seat about centre of Bench immediately behind Prince

Arthur; has occasionally risen thence and offered a few observations.

Characteristic of him that he was born in a Cathedral town; is

a Bencher of the Middle Temple.

Persuasion tips his tongue whene'er he'll talk,

And he has Chambers near the King's Bench Walk.

These things we knew; but not till

to-night came discovery how persuasive

Ambrose can be.

It was the Tenth Clause of the Home-Rule

Bill that roused the (attorney's)

devil in him. Fact that Clause II. was

under discussion, and consequently out

of order to debate Clause X., an incident

of no consequence, except that it indirectly

supplied incentive to his passionate

eloquence, and led to disclosure of the

true Ambrose. When he approached

Clause X., cries of "Order! Order!"

interrupted. The Chairman recalled him

to consideration of Clause II. He came

back, said a few words on amendment,

then was off again at Clause X., pursued

by howls. Had got a start, and kept it

through some moments of thunderous

excitement. Waved his arms, thumped

his papers; shouted at top of voice; House still howling; Chairman on

feet ineffectually protesting. "Glad to see the Solicitor-Gentleman

in his place," he observed, in one of the temporary pauses,

(Rigby usually alluded to as the Solicitor-General, but

Ambrose, once started in new character, was lavish in originality.)

"Need I go further?" he asked, a few moments later. House, with

one accord, shouted "No!" "Now Sir," he added, waving his

notes in face of Chairman, "I've done with the Tenth Clause."

But he hadn't; its mastery over him was irresistible, even uncanny.

"I should like to know what the Solicitor-General" (got it right

this time) "if he were at liberty to speak" (this with a withering

glance at Mr. G.), "would say about the Tenth Clause?"

A roar angrier than ever burst forth; shouts of "Name! Name!"

persistently heard above uproar; Chairman on his feet, with hands

outstretched; crisis evidently arrived; Ambrose will be named to a

dead certainty; suspended, and, perhaps, in addition to his bench at

the Middle Temple, will have one provided for him in Clock Tower.

Would like to have said few more words on Tenth Clause, but

numbers against him overwhelming. So wildly waved his notes

in sort of forlorn despairing farewell, and resumed his seat.

Incident created profound sensation.

"It's all very well Chamberlain insisting on keeping this thing

going," said Prince Arthur, anxiously; "but I have my responsibilities.

If Debate at this comparatively early stage thus affects a

man like Ambrose, where shall we all be in another week?"

Business done.—Still on Clause II.

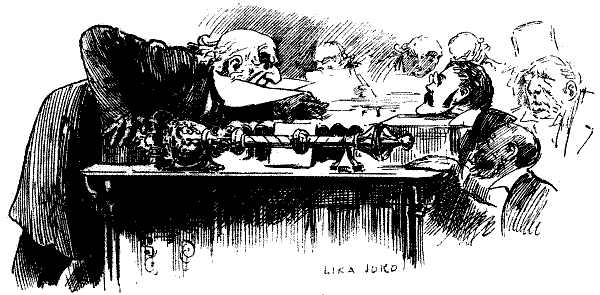

Wednesday.—Pretty to see Gorst just now balancing

Macartney's

hat by brim on tip of his nose. Looks easy enough when done

by an expert; those inclined to scoff at the accomplishment

should try it themselves. Opportunity came suddenly, and unexpectedly.

No ground for supposing Gorst had been practising

the trick in the Cloak-room before entering House. No collusion;

all fair and above-board—or, rather, above nose. Came about as

incident in Committee on Home-Rule Bill. Jokim, taking part in

game of Chairman-baiting, challenged Mellor's ruling on putting

Motion to Report Progress. House being cleared for a Division,

rules of debate require Member to address Chair seated, and wearing

his hat. What would happen to British Constitution if, in such

circumstances, Member rose and addressed Speaker or Chairman

in ordinary fashion, Heaven only knows. No mere man bold enough

to try it. Even Mr. G., who has Disestablished a Church, and now

tampers with Unity of the Empire, shrinks before this temptation.

Jokim, making his complaint, got along all right. Performed

task in due form; Mellor justified his action; Gorst proposed

to

follow. Hadn't got his hat with him; but that of no consequence,

since Jokim was at hand. "Lend me one of your hats," he whispered

hurriedly to his Right Hon. Friend.

"What do you mean?" said Jokim. "I've only one."

"Oh!" said Gorst, raising his eyebrows with polite incredulity.

Macartney, sitting behind, proffered his. Gorst planted it on

his

head; found it three sizes too small; still, if he held on to it, he

might manage. "Mr. Mellor," he commenced, but got no further

with projected speech. Attention of House drawn to him his

dilemma discovered: shout of laughter burst forth as hat gradually

tilted forward, and Gorst, deftly catching it by brim on tip of his

nose, balanced it for fifteen seconds by Westminster Clock. Chairman

seized opportunity of abstracted attention to put question, and

when Gorst, recapturing Macartney's hat, had fixed it again on

summit of his head, division was called; too late for him to speak.

Business done.—Second Clause Home Rule Bill added.

Mr. G.'s "Table-Talk."

Friday.—Treasury Chest Bill on for Third Reading. Has since

introduction wrought singular effect upon Hanbury. Nobody knows

what Bill is about, least of all Hanbury; but he has opposed it at

every stage. Yesterday divided Committee on First Clause; returns

to attack to-day. "Better let us get away for our hardly-earned

holiday," I said.

"That's very well for you, Toby," said Hanbury, beating his

chest in default of getting at the Treasury's; "but there's a dark

mystery under this business which I mean to fathom. You remember

the case of another chest and its weird associations?

'Fifteen men on a dead man's chest—

Ho! Ho! Ho! and a bottle of rum.'

Harcourt may, or may not, have been one of the fifteen. I'm not

quite clear on that point. Indeed I'm somewhat muddled in the

main; but I suspect the Squire is up to some deed of infamy, and

I have done my best to plumb its slimy depths."

Bill passed nevertheless; other business wound up, and so off for

holidays. Business done.—House adjourned for Whitsun Recess.

The Real "Rejected Addresses."—Those that cannot be

deciphered at the General Post Office.