Title: The Book of the National Parks

Author: Robert Sterling Yard

Release date: December 12, 2008 [eBook #27513]

Most recently updated: January 4, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist and The Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note

The punctuation and spelling from the original text have been faithfully preserved. Only obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

The photograph "The Rainbow Natural Bridge, Utah", facing page 8, is missing from the source document even though presented in the List of Illustrations.

THE BOOK OF

THE NATIONAL PARKS

BY

ROBERT STERLING YARD

CHIEF, EDUCATIONAL DIVISION, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, DEPARTMENT

OF THE INTERIOR

AUTHOR OF "THE NATIONAL PARKS PORTFOLIO"

"THE TOP OF THE CONTINENT," ETC.

WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1919

In offering the American public a carefully studied outline of its national park system, I have two principal objects. The one is to describe and differentiate the national parks in a manner which will enable the reader to appreciate their importance, scope, meaning, beauty, manifold uses and enormous value to individual and nation. The other is to use these parks, in which Nature is writing in large plain lines the story of America's making, as examples illustrating the several kinds of scenery, and what each kind means in terms of world building; in other words, to translate the practical findings of science into unscientific phrase for the reader's increased profit and pleasure, not only in his national parks but in all other scenic places great and small.

At the outset I have been confronted with a difficulty because of this double objective. The rôle of the interpreter is not always welcome. If I write what is vaguely known as a "popular" book, wise men have warned me that any scientific intrusion, however lightly and dramatically rendered, will displease its natural audience. If I write the simplest of scientific books, I am warned that a large body of warm-blooded, wholesome, enthusiastic Americans, the very ones above all others whose keen enjoyment[Pg viii] I want to double by doubling their sources of pleasure, will have none of it. The suggestion that I make my text "popular" and carry my "science" in an appendix I promptly rejected, for if I cannot give the scientific aspects of nature their readable values in the text, I cannot make them worth an appendix.

Now I fail to share with my advisers their poor opinion of the taste, enterprise, and intelligence of the wide-awake American, but, for the sake of my message, I yield in some part to their warnings. Therefore I have so presented my material that the miscalled, and, I verily believe, badly slandered "average reader," may have his "popular" book by omitting the note on the Appreciation of Scenery, and the several notes explanatory of scenery which are interpolated between groups of chapters. If it is true, as I have been told, that the "average reader" would omit these anyway, because it is his habit to omit prefaces and notes of every kind, then nothing has been lost.

The keen inquiring reader, however, the reader who wants to know values and to get, in the eloquent phrase of the day, all that's coming to him, will have the whole story by beginning the book with the note on the Appreciation of Scenery, and reading it consecutively, interpolated notes and all. As this will involve less than a score of additional pages, I hope to get the message of the national parks in terms of their fullest enjoyment before much the greater part of the book's readers.

The pleasure of writing this book has many times[Pg ix] repaid its cost in labor, and any helpfulness it may have in advancing the popularity of our national parks, in building up the system's worth as a national economic asset, and in increasing the people's pleasure in all scenery by helping them to appreciate their greatest scenery, will come to me as pure profit. It is my earnest hope that this profit may be large.

A similar spirit has actuated the very many who have helped me acquire the knowledge and experience to produce it; the officials of the National Park Service, the superintendents and several rangers in the national parks, certain zoologists of the United States Biological Survey, the Director and many geologists of the United States Geological Survey, scientific experts of the Smithsonian Institution, and professors in several distinguished universities. Many men have been patient and untiring in assistance and helpful criticism, and to these I render warm thanks for myself and for readers who may benefit by their work.

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | vii | |

| THE BOOK OF THE NATIONAL PARKS | ||

| On the Appreciation of Scenery | 3 | |

| I. | The National Parks of the United States | 17 |

| THE GRANITE NATIONAL PARKS | ||

| Granite's Part in Scenery | 33 | |

| II. | Yosemite, the Incomparable | 36 |

| III. | The Proposed Roosevelt National Park | 69 |

| IV. | The Heart of the Rockies | 93 |

| V. | McKinley, Giant of Giants | 118 |

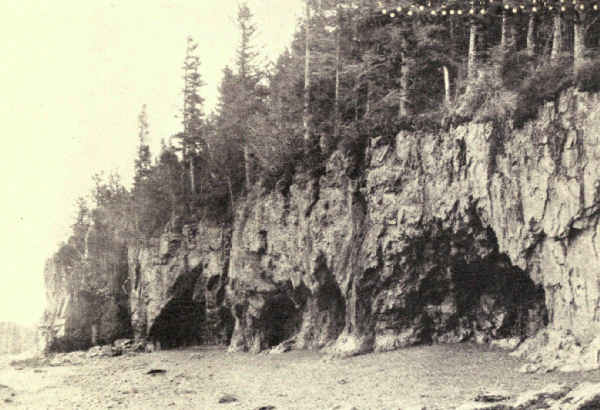

| VI. | Lafayette and the East | 132 |

| THE VOLCANIC NATIONAL PARKS | ||

| On the Volcano in Scenery | 145 | |

| VII. | Lassen Peak and Mount Katmai | 148 |

| VIII. | Mount Rainier, Icy Octopus | 159 |

| IX. | Crater Lake's Bowl of Indigo | 184 |

| X. | Yellowstone, a Volcanic Interlude | 202 |

| XI. | Three Monsters of Hawaii | 229 |

| THE SEDIMENTARY NATIONAL PARKS[Pg xii] | ||

| XII. | On Sedimentary Rock in Scenery | 247 |

| XIII. | Glaciered Peaks and Painted Shales | 251 |

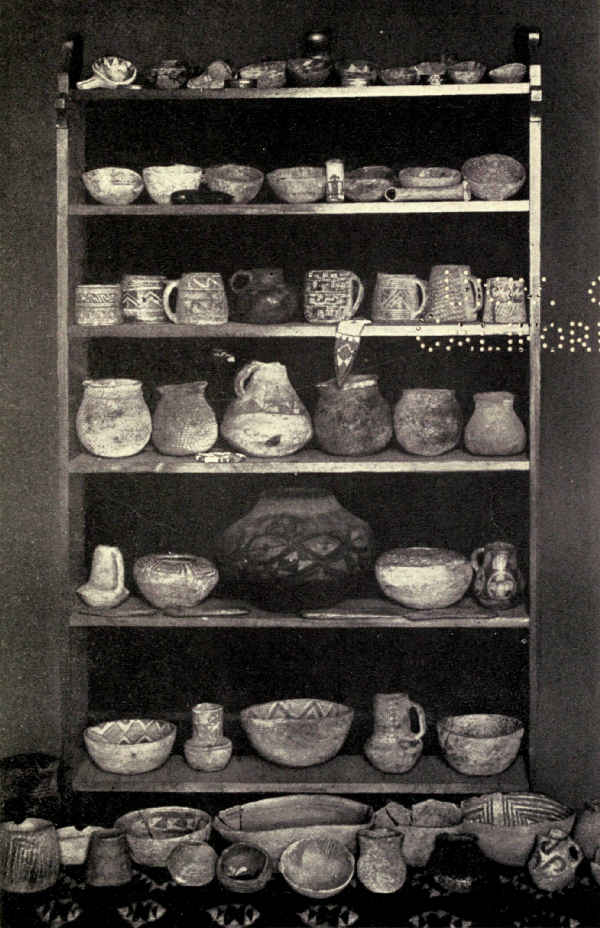

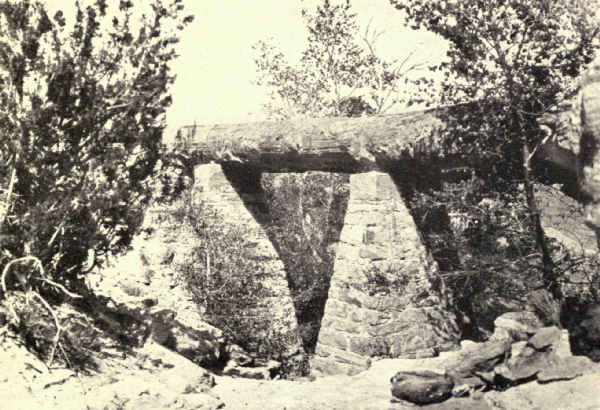

| XIV. | Rock Records of a Vanished Race | 284 |

| XV. | The Healing Waters | 305 |

| THE GRAND CANYON AND OUR NATIONAL MONUMENTS | ||

| On the Scenery of the Southwest | 321 | |

| XVI. | A Pageant of Creation | 328 |

| XVII. | The Rainbow of the Desert | 352 |

| XVIII. | Historic Monuments of the Southwest | 367 |

| XIX. | Desert Spectacles | 385 |

| XX. | The Muir Woods and Other National Monuments | 404 |

| PAGE | |

| Cross-section of Crater Lake showing probable outline of Mount Mazama | 189 |

| Cross-section of Crater Lake | 191 |

| Map of Hawaii National Park | 230 |

| FACING PAGE | |

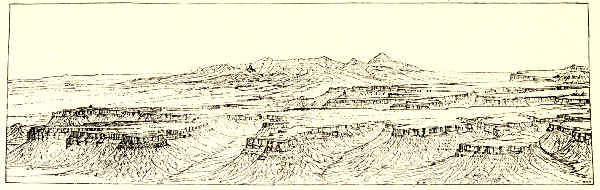

| Outline of the Mesa Verde Formation | 290 |

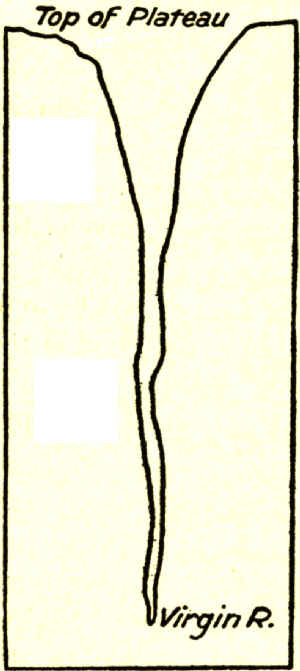

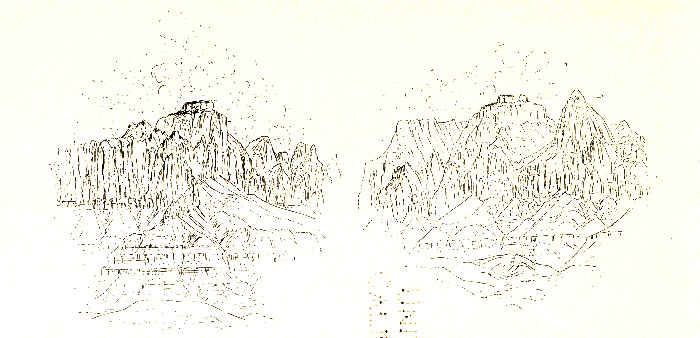

| Outlines of the Western and Eastern Temples, Zion National Monument | 356 |

To the average educated American, scenery is a pleasing hodge-podge of mountains, valleys, plains, lakes, and rivers. To him, the glacier-hollowed valley of Yosemite, the stream-scooped abyss of the Grand Canyon, the volcanic gulf of Crater Lake, the bristling granite core of the Rockies, and the ancient ice-carved shales of Glacier National Park all are one—just scenery, magnificent, incomparable, meaningless. As a people we have been content to wonder, not to know; yet with scenery, as with all else, to know is to begin fully to enjoy. Appreciation measures enjoyment. And this brings me to my proposition, namely, that we shall not really enjoy our possession of the grandest scenery in the world until we realize that scenery is the written page of the History of Creation, and until we learn to read that page.

The national parks of America include areas of the noblest and most diversified scenic sublimity easily accessible in the world; nevertheless it is their chiefest glory that they are among the completest expressions of the earth's history. The American people is waking rapidly to the magnitude of its scenic possession; it has yet to learn to appreciate it.

Nevertheless we love scenery. We are a nation of sightseers. The year before the world war stopped all things, we spent $286,000,000 in going to Europe. That summer Switzerland's receipts from the sale of transportation and board to persons coming from foreign lands to see her scenery was $100,000,000, and more than half, it has been stated apparently with authority, came from America. That same year tourist travel became Canada's fourth largest source of income, exceeding in gross receipts even her fisheries, and the greater part came from the United States; it is a matter of record that seven-tenths of the hotel registrations in the Canadian Rockies were from south of the border. Had we then known, as a nation, that there was just as good scenery of its kind in the United States, and many more kinds, we would have gone to see that; it is a national trait to buy the best. Since then, we have discovered this important fact and are crowding to our national parks.

"Is it true," a woman asked me at the foot of Yosemite Falls, "that this is the highest unbroken waterfall in the world?"

She was the average tourist, met there by chance. I assured her that such was the fact. I called attention to the apparent deliberation of the water's fall, a trick of the senses resulting from failure to realize height and distance.

"To think they are the highest in the world!" she mused.

I told her that the soft fingers of water had carved[Pg 5] this valley three thousand feet into the solid granite, and that ice had polished its walls, and I estimated for her the ages since the Merced River flowed at the level of the cataract's brink.

"I've seen the tallest building in the world," she replied dreamily, "and the longest railroad, and the largest lake, and the highest monument, and the biggest department store, and now I see the highest waterfall. Just think of it!"

If one has illusions concerning the average tourist, let him compare the hundreds who gape at the paint pots and geysers of Yellowstone with the dozens who exult in the sublimated glory of the colorful canyon. Or let him listen to the table-talk of a party returned from Crater Lake. Or let him recall the statistical superlatives which made up his friend's last letter from the Grand Canyon.

I am not condemning wonder, which, in its place, is a legitimate and pleasurable emotion. As a condiment to sharpen and accent an abounding sense of beauty it has real and abiding value.

Love of beauty is practically a universal passion. It is that which lures millions into the fields, valleys, woods, and mountains on every holiday, which crowds our ocean lanes and railroads. The fact that few of these rejoicing millions are aware of their own motive, and that, strangely enough, a few even would be ashamed to make the admission if they became aware of it, has nothing to do with the fact. It's a wise man that knows his own motives. The fact that still[Pg 6] fewer, whether aware or not of the reason of their happiness, are capable of making the least expression of it, also has nothing to do with the fact. The tourist woman whom I met at the foot of Yosemite Falls may have felt secretly suffocated by the filmy grandeur of the incomparable spectacle, notwithstanding that she was conscious of no higher emotion than the cheap wonder of a superlative. The Grand Canyon's rim is the stillest crowded place I know. I've stood among a hundred people on a precipice and heard the whir of a bird's wings in the abyss. Probably the majority of those silent gazers were suffering something akin to pain at their inability to give vent to the emotions bursting within them.

I believe that the statement can not be successfully challenged that, as a people, our enjoyment of scenery is almost wholly emotional. Love of beauty spiced by wonder is the equipment for enjoyment of the average intelligent traveller of to-day. Now add to this a more or less equal part of the intellectual pleasure of comprehension and you have the equipment of the average intelligent traveller of to-morrow. To hasten this to-morrow is one of the several objects of this book.

To see in the carved and colorful depths of the Grand Canyon not only the stupendous abyss whose terrible beauty grips the soul, but also to-day's chapter in a thrilling story of creation whose beginning lay untold centuries back in the ages, whose scene covers three hundred thousand square miles of our wonderful[Pg 7] southwest, whose actors include the greatest forces of nature, whose tremendous episodes shame the imagination of Doré, and whose logical end invites suggestions before which finite minds shrink—this is to come into the presence of the great spectacle properly equipped for its enjoyment. But how many who see the Grand Canyon get more out of it than merely the beauty that grips the soul?

So it is throughout the world of scenery. The geologic story written on the cliffs of Crater Lake is more stupendous even than the glory of its indigo bowl. The war of titanic forces described in simple language on the rocks of Glacier National Park is unexcelled in sublimity in the history of mankind. The story of Yellowstone's making multiplies many times the thrill occasioned by its world-famed spectacle. Even the simplest and smallest rock details often tell thrilling incidents of prehistoric tunes out of which the enlightened imagination reconstructs the romances and the tragedies of earth's earlier days.

How eloquent, for example, was the small, water-worn fragment of dull coal we found on the limestone slope of one of Glacier's mountains! Impossible companionship! The one the product of forest, the other of submerged depths. Instantly I glimpsed the distant age when thousands of feet above the very spot upon which I stood, but then at sea level, bloomed a Cretaceous forest, whose broken trunks and matted foliage decayed in bogs where they slowly turned to coal; coal which, exposed and disintegrated during[Pg 8] intervening ages, has long since—all but a few small fragments like this—washed into the headwaters of the Saskatchewan to merge eventually in the muds of Hudson Bay. And then, still dreaming, my mind leaped millions of years still further back to lake bottoms where, ten thousand feet below the spot on which I stood, gathered the pre-Cambrian ooze which later hardened to this very limestone. From ooze a score of thousand feet, a hundred million years, to coal! And both lie here together now in my palm! Filled thus with visions of a perspective beyond human comprehension, with what multiplied intensity of interest I now returned to the noble view from Gable Mountain!

In pleading for a higher understanding of Nature's method and accomplishment as a precedent to study and observation of our national parks, I seek enormously to enrich the enjoyment not only of these supreme examples but of all examples of world making. The same readings which will prepare you to enjoy to the full the message of our national parks will invest your neighborhood hills at home, your creek and river and prairie, your vacation valleys, the landscape through your car window, even your wayside ditch, with living interest. I invite you to a new and fascinating earth, an earth interesting, vital, personal, beloved, because at last known and understood!

It requires no great study to know and understand the earth well enough for such purpose as this. One does not have to dim his eyes with acres of maps,[Pg 9] or become a plodding geologist, or learn to distinguish schists from granites, or to classify plants by table, or to call wild geese and marmots by their Latin names. It is true that geography, geology, physiography, mineralogy, botany and zoology must each contribute their share toward the condition of intelligence which will enable you to realize appreciation of Nature's amazing earth, but the share of each is so small that the problem will be solved, not by exhaustive study, but by the selection of essential parts. Two or three popular books which interpret natural science in perspective should pleasurably accomplish your purpose. But once begun, I predict that few will fail to carry certain subjects beyond the mere essentials, while some will enter for life into a land of new delights.

Let us, for illustration, consider for a moment the making of America. The earth, composed of countless aggregations of matter drawn together from the skies, whirled into a globe, settled into a solid mass surrounded by an atmosphere carrying water like a sponge, has reached the stage of development when land and sea have divided the surface between them, and successions of heat and frost, snow, ice, rain, and flood, are busy with their ceaseless carving of the land. Already mountains are wearing down and sea bottoms are building up with their refuse. Sediments carried by the rivers are depositing in strata, which some day will harden into rock.

We are looking now at the close of the era which[Pg 10] geologists call Archean, because it is ancient beyond knowledge. A few of its rocks are known, but not well enough for many definite conclusions. All the earth's vast mysterious past is lumped under this title.

The definite history of the earth begins with the close of the dim Archean era. It is the lapse from then till now, a few hundred million years at most out of all infinity, which ever can greatly concern man, for during this time were laid the only rocks whose reading was assisted by the presence of fossils. During this time the continents attained their final shape, the mountains rose, and valleys, plains, and rivers formed and re-formed many times before assuming the passing forms which they now show. During this time also life evolved from its inferred beginnings in the late Archean to the complicated, finely developed, and in man's case highly mentalized and spiritualized organization of To-day.

Surely the geologist's field of labor is replete with interest, inspiration, even romance. But because it has become so saturated with technicality as to become almost a popular bugaboo, let us attempt no special study, but rather cull from its voluminous records those simple facts and perspectives which will reveal to us this greatest of all story books, our old earth, as the volume of enchantment that it really is.

With the passing of the Archean, the earth had not yet settled into the perfectly balanced sphere which Nature destined it to be. In some places the rock was more compactly squeezed than in others,[Pg 11] and these denser masses eventually were forced violently into neighbor masses which were not so tightly squeezed. These movements far below the surface shifted the surface balance and became one of many complicated and little known causes impelling the crust here to slowly rise and there to slowly fall. Thus in places sea bottoms lifted above the surface and became land, while lands elsewhere settled and became seas. There are areas which have alternated many times between land and sea; this is why we find limestones which were formed in the sea overlying shales which were formed in fresh water, which in turn overlie sandstones which once were beaches—all these now in plateaus thousands of feet above the ocean's level.

Sometimes these mysterious internal forces lifted the surface in long waves. Thus mountain chains and mountain systems were created. Often their summits, worn down by frosts and rains, disclose the core of rock which, ages before, then hot and fluid, had underlain the crust and bent it upward into mountain form. Now, cold and hard, these masses are disclosed as the granite of to-day's landscape, or as other igneous rocks of earth's interior which now cover broad surface areas, mingled with the stratified or water-made rocks which the surface only produces. But this has not always been the fate of the under-surface molten rocks, for sometimes they have burst by volcanic vents clear through the crust of earth, where, turned instantly to pumice and lava by release[Pg 12] from pressure, they build great surface cones, cover broad plains and fill basins and valleys.

Thus were created the three great divisions of the rocks which form the three great divisions of scenery, the sediments, the granites, and the lavas.

During these changes in the levels of enormous surface areas, the frosts and water have been industriously working down the elevations of the land. Nature forever seeks a level. The snows of winter, melting at midday, sink into the rocks' minutest cracks. Expanded by the frosts, the imprisoned water pries open and chips the surface. The rains of spring and summer wash the chippings and other débris into rivulets, which carry them into mountain torrents, which rush them into rivers, which sweep them into oceans, which deposit them for the upbuilding of the bottoms. Always the level! Thousands of square miles of California were built up from ocean's bottom with sediments chiselled from the mountains of Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah, and swept seaward through the Grand Canyon.

These mills grind without rest or pause. The atmosphere gathers the moisture from the sea, the winds roll it in clouds to the land, the mountains catch and chill the clouds, and the resulting rains hurry back to the sea in rivers bearing heavy freights of soil. Spring, summer, autumn, winter, day and night, the mills of Nature labor unceasingly to produce her level. If ever this earth is really finished to Nature's liking, it will be as round and polished as a billiard ball.

Years mean nothing in the computation of the prehistoric past. Who can conceive a thousand centuries, to say nothing of a million years? Yet either is inconsiderable against the total lapse of time even from the Archean's close till now.

And so geologists have devised an easier method of count, measured not by units of time, but by what each phase of progress has accomplished. This measure is set forth in the accompanying table, together with a conjecture concerning the lapse of time in terms of years.

The most illuminating accomplishment of the table, however, is its bird's-eye view of the procession of the evolution of life from the first inference of its existence to its climax of to-day; and, concurrent with this progress, its suggestion of the growth and development of scenic America. It is, in effect, the table of contents of a volume whose thrilling text and stupendous illustration are engraved immortally in the rocks; a volume whose ultimate secrets the scholarship of all time perhaps will never fully decipher, but whose dramatic outlines and many of whose most thrilling incidents are open to all at the expense of a little study at home and a little thoughtful seeing in the places where the facts are pictured in lines so big and graphic that none may miss their meanings.

Man's colossal egotism is rudely shaken before the Procession of the Ages. Aghast, he discovers that the billions of years which have wrought this earth from star dust were not merely God's laborious preparation of a habitation fit for so admirable an occupant; that man, on the contrary, is nothing more or less than the present master tenant of earth, the highest type of hundreds of millions of years of succeeding tenants only because he is the latest in evolution.

PROGRESS OF CREATION

Chart of the Divisions of Geologic Time, and an Estimate in Years based on the assumption that a hundred million years have elapsed since the close of the Archean Period, together with a condensed table of the Evolution of Life from its Inferred Beginnings in the Archean to the Present Time. Read from the bottom up. Read the footnote upon the opposite page concerning the Estimate of Time.

| ERA | PERIOD | EPOCH | LIFE DEVELOPMENT | ESTIMATED TIME |

| Cenozoic Era of Recent Life |

Quaternary | Recent Pleistocene (Ice Age) |

The Age of Man

Animals and plants of the modern type. First record of man occurs in the early Pleistocene. |

6 millions of years. |

| Tertiary | Pliocene Miocene Oligocene Eocene |

The Age of Mammals

Rise and development of the highest orders of plants and animals. |

||

| Mesozoic Era of Intermediate Life |

Cretaceous | The Age of Reptiles

Shellfish with complex shells. Enormous land reptiles. Flying reptiles and the evolution

therefrom of birds. First palms. First hardwood trees. First mammals. |

16 millions of years. |

|

| Jurassic | ||||

| Triassic | ||||

| Carboniferous | Permian Pennsylvanian Mississippian |

The Age of Amphibians. The Coal Age

Sharks and sea animals with nautilus-like shells. Evolution of land plants in many complex

forms. First appearance of land vertebrates. First flowering plants. First cone-bearing

trees. Club mosses and ferns highly developed. |

||

| Paleozoic Era of Old Life |

Devonian | The Age of Fishes

Evolution of many forms. Fish of great size. First appearance of amphibians and land plants. |

45 millions of years. |

|

| Silurian | Shellfish develop fully. Appearance and culmination of crinoids or sea-lilies, and large scorpion-like crustaceans. First appearance of reef-building corals. Development of fishes. | |||

| Ordovician | Sea animals develop shells, especially cephalopods and mollusk-like brachiopods. Trilobites at their height. First appearance of insects. First appearance of fishes. | |||

| Cambrian | More highly developed forms of water life. Trilobites and brachiopods most abundant. Algæ. | |||

| Proterozoic | Algonkian | The first life which left a distinct record. Very primitive forms of water life, crustaceans, brachiopods and algæ. | 33 millions of years. |

|

| Archeozoic | Archean | No fossils found, but life inferred from the existence of iron ores and limestones, which are generally formed in the presence of organisms. |

Who can safely declare that the day will not come when a new Yellowstone, hurled from reopened volcanoes, shall found itself upon the buried ruin of the present Yellowstone; when the present Sierra shall have disappeared into the Pacific and the deserts of the Great Basin become the gardens of the hemisphere; when a new Rocky Mountain system shall have grown upon the eroded and dissipated granites of the present; when shallow seas shall join anew Hudson Bay with the Gulf of Mexico; when a new and lofty Appalachian Range shall replace the rounded summits of to-day; when a race of beings as superior to man, intellectually and spiritually, as man is superior to the ape, shall endeavor to reconstruct a picture of man from the occasional remnants which floods may wash into view?

NOTE EXPLANATORY OF THE ESTIMATE OF GEOLOGIC TIME IN THE TABLE ON THE OPPOSITE PAGE

The general assumption of modern geologists is that a hundred million years have elapsed since the close of the Archean period; at least this is a round number, convenient for thinking and discussion. The recent tendency has been greatly to increase conceptions of geologic time over the highly conservative estimates of a few years ago, and a strong disposition is shown to regard the Algonkian period as one of very great length, extremists even suggesting that it may have equalled all time since. For the purposes of this popular book, then, let us conceive that the earth has existed for a hundred million years since Archean times, and that one-third of this was Algonkian; and let us apportion the two-thirds remaining among succeeding eras in the average of the proportions adopted by Professor Joseph Barrell of Yale University, whose recent speculations upon geologic time have attracted wide attention.

Fantastic, you may say. It is fantastic. So far as I know there exists not one fact upon which definite predictions such as these may be based. But also there exists not one fact which warrants specific denial of predictions such as these. And if any inference whatever may be made from earth's history it is the inevitable inference that the period in which man lives is merely one step in an evolution of matter, mind and spirit which looks forward to changes as mighty or mightier than those I have suggested.

With so inspiring an outline, the study to which I invite you can be nothing but pleasurable. Space does not permit the development of the theme in the pages which follow, but the book will have failed if it does not, incidental to its main purposes, entangle the reader in the charm of America's adventurous past.

The National Parks of the United States are areas of supreme scenic splendor or other unique quality which Congress has set apart for the pleasure and benefit of the people. At this writing they number eighteen, sixteen of which lie within the boundaries of the United States and are reached by rail and road. Those of greater importance have excellent roads, good trails, and hotels or hotel camps, or both, for the accommodation of visitors; also public camp grounds where visitors may pitch their own tents. Outside the United States there are two national parks, one enclosing three celebrated volcanic craters, the other conserving the loftiest mountain on the continent.

The starting point for any consideration of our national parks necessarily is the recently realized fact of their supremacy in world scenery. It was the sensational force of this realization which intensely attracted public attention at the outset of the new movement; many thousands hastened to see these wonders, and their reports spread the tidings throughout the land and gave the movement its increasing impetus.

The simple facts are these:

The Swiss Alps, except for several unmatchable individual features, are excelled in beauty, sublimity and variety by several of our own national parks, and these same parks possess other distinguished individual features unrepresented in kind or splendor in the Alps.

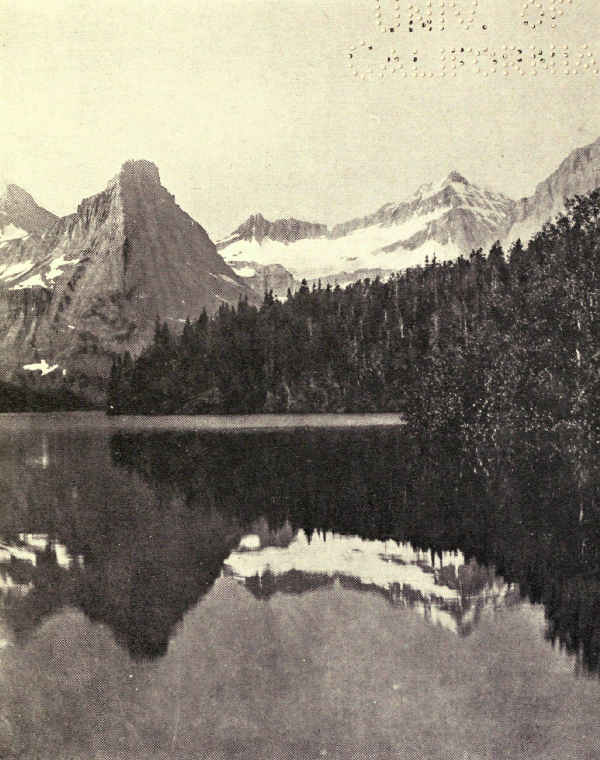

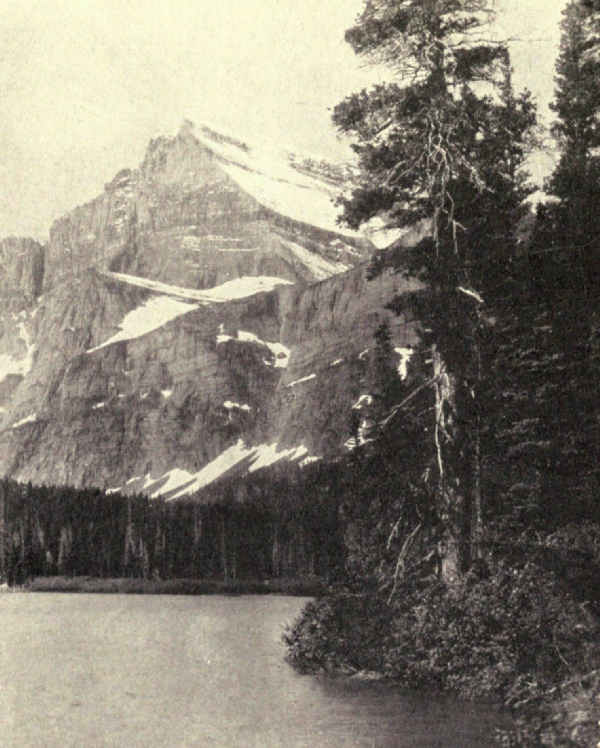

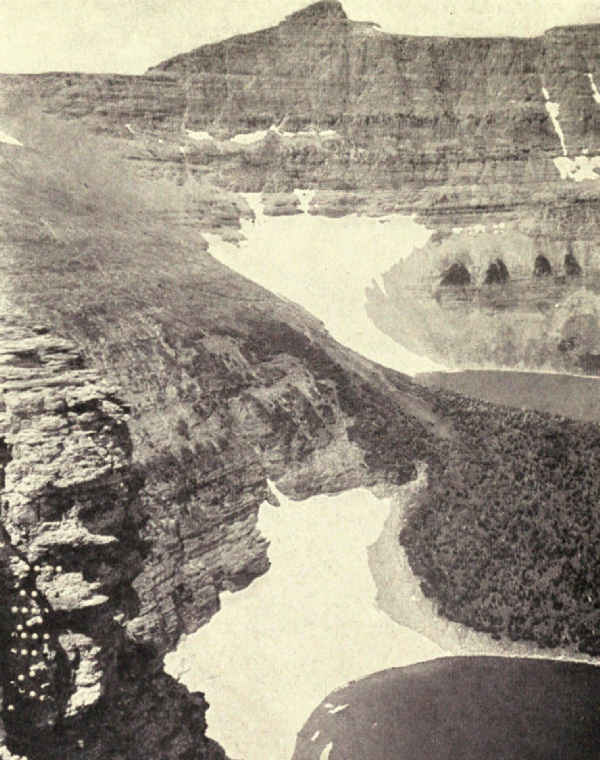

The Canadian Rockies are more than matched in rich coloring by our Glacier National Park. Glacier is the Canadian Rockies done in Grand Canyon colors. It has no peer.

The Yellowstone outranks by far any similar volcanic area in the world. It contains more and greater geysers than all the rest of the world together; the next in rank are divided between Iceland and New Zealand. Its famous canyon is alone of its quality of beauty. Except for portions of the African jungle, the Yellowstone is probably the most populated wild animal area in the world, and its wild animals are comparatively fearless, even sometimes friendly.

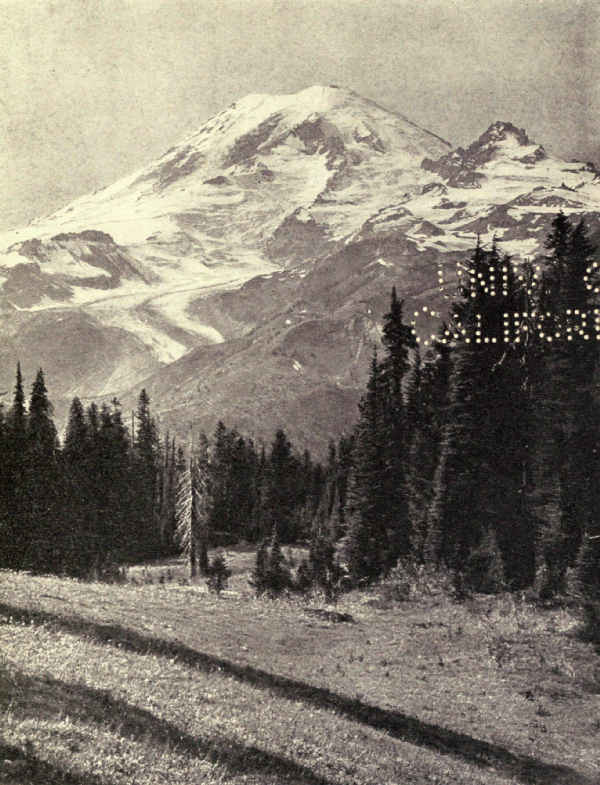

Mount Rainier has a single-peak glacier system whose equal has not yet been discovered. Twenty-eight living glaciers, some of them very large, spread, octopus-like, from its centre. It is four hours by rail or motor from Tacoma.

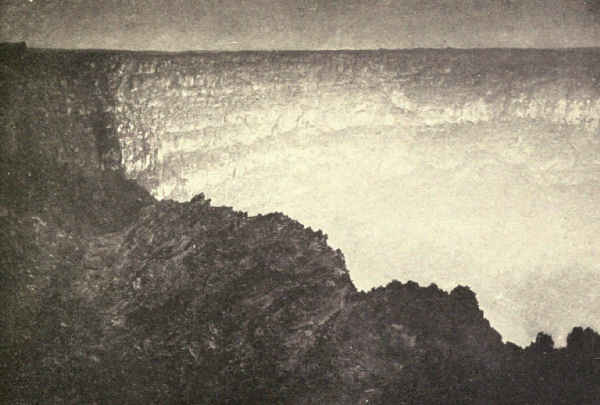

Crater Lake is the deepest and bluest accessible lake in the world, occupying the hole left after one of our largest volcanoes had slipped back into earth's interior through its own rim.

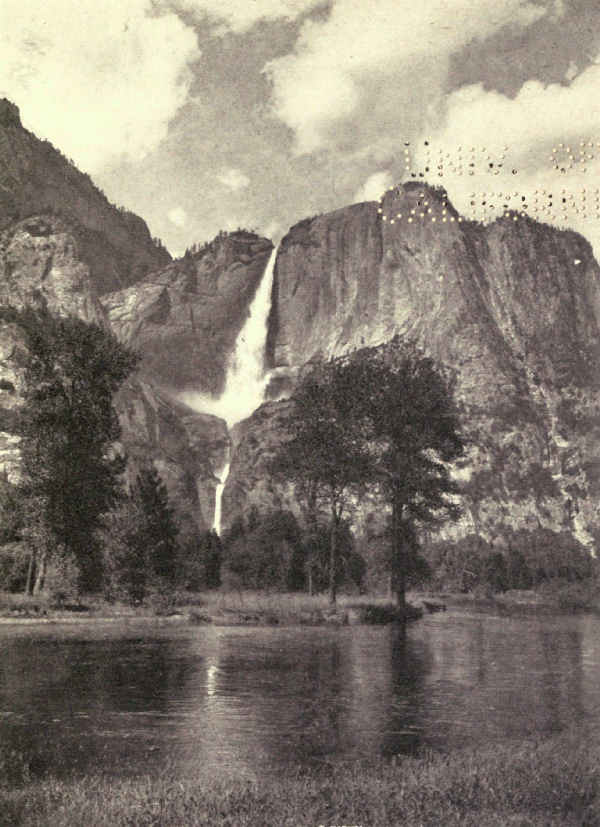

Yosemite possesses a valley whose compelling beauty the world acknowledges as supreme. The valley is the centre of eleven hundred square miles of high altitude wilderness.

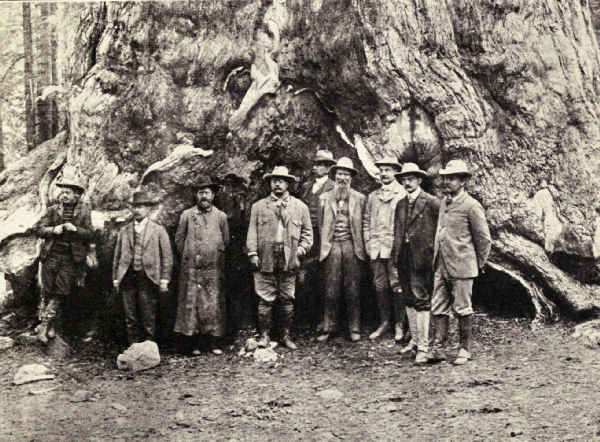

The Sequoia contains more than a million sequoia trees, twelve thousand of which are more than ten feet in diameter, and some of which are the largest and oldest living things in the wide world.

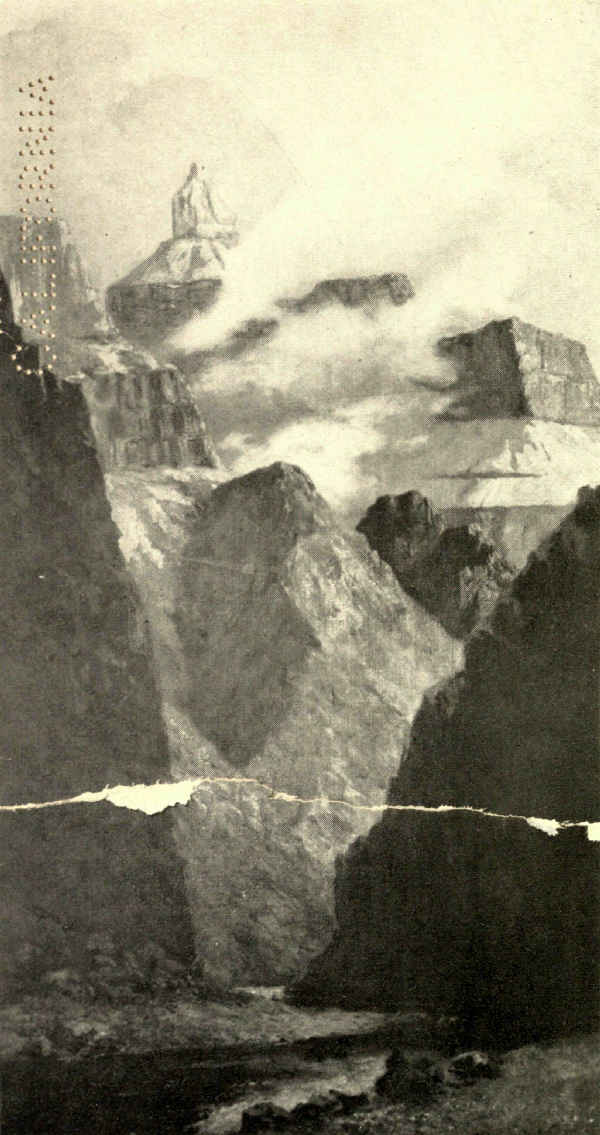

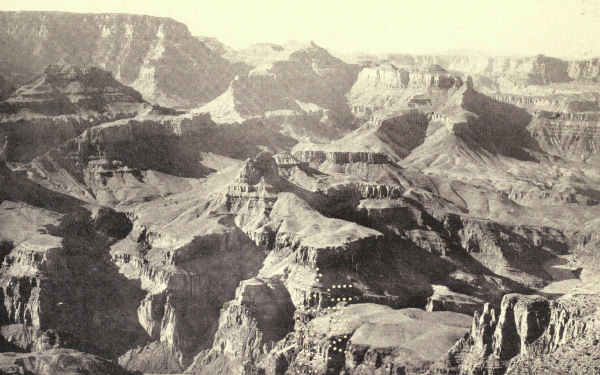

The Grand Canyon of Arizona is by far the hugest and noblest example of erosion in the world. It is gorgeously carved and colored. In sheer sublimity it offers an unequalled spectacle.

Mount McKinley stands more than 20,000 feet above sea level, and 17,000 feet above the surrounding valleys. Scenically, it is the world's loftiest mountain, for the monsters of the Andes and the Himalayas which surpass it in altitude can be viewed closely only from valleys from five to ten thousand feet higher than McKinley's northern valleys.

The Hawaii National Park contains the fourth greatest dead crater in the world, the hugest living volcano, and the Kilauea Lake of Fire, which is unique and draws visitors from the world's four quarters.

These are the principal features of America's world supremacy. They are incidental to a system of scenic wildernesses which in combined area as well as variety exceed the combined scenic wilderness playgrounds of similar class comfortably accessible elsewhere. No wonder, then, that the American public is overjoyed with its recently realized treasure, and that the Government looks confidently to the rapid development of its new-found economic asset. The[Pg 20] American public has discovered America, and no one who knows the American public doubts for a moment what it will do with it.

The idea still widely obtains that our national parks are principally playgrounds. A distinguished member of Congress recently asked: "Why make these appropriations? More people visited Rock Creek Park here in the city of Washington last Sunday afternoon than went to the Yosemite all last summer. The country has endless woods and mountains which cost the Treasury nothing."

This view entirely misses the point. The national parks are recreational, of course. So are state, county and city parks. So are resorts of every kind. So are the fields, the woods, the seashore, the open country everywhere. We are living in an open-air age. The nation of outdoor livers is a nation of power, initiative, and sanity. I hope to see the time when available State lands everywhere, when every square mile from our national forest reserve, when even many private holdings are made accessible and comfortable, and become habited with summer trampers and campers. It is the way to individual power and national efficiency.

But the national parks are far more than recreational areas. They are the supreme examples. They are the gallery of masterpieces. Here the visitor enters in a holier spirit. Here is inspiration. They are[Pg 21] also the museums of the ages. Here nature is still creating the earth upon a scale so vast and so plain that even the dull and the frivolous cannot fail to see and comprehend.

This is no distinction without a difference. The difference is so marked that few indeed even of those who visit our national parks in a frivolous or merely recreational mood remain in that mood. The spirit of the great places brooks nothing short of silent reverence. I have seen men unconsciously lift their hats. The mind strips itself of affairs as one sheds a coat. It is the hour of the spirit. One returns to daily living with a springier step, a keener vision, and a broader horizon for having worshipped at the shrine of the Infinite.

The Pacific Coast Expositions of 1915 marked the beginning of the nation's acquaintance with its national parks. In fact, they were the occasion, if not the cause, of the movement for national parks development which found so quickly a country-wide response, and which is destined to results of large importance to individual and nation alike. Because thousands of those whom the expositions were expected to draw westward would avail of the opportunity to visit national parks, Secretary Lane, to whom the national parks suggested neglected opportunity requiring business experience to develop, induced Stephen T. Mather, a Chicago business man with[Pg 22] mountain-top enthusiasms, to undertake their preparation for the unaccustomed throngs. Mr. Mather's vision embraced a correlated system of superlative scenic areas which should become the familiar playgrounds of the whole American people, a system which, if organized and administered with the efficiency of a great business, should even become, in time, the rendezvous of the sightseers of the world. He foresaw in the national parks a new and great national economic asset.

The educational and other propaganda by which this movement was presented to the people, which the writer had the honor to plan and execute, won rapidly the wide support of the public. To me the national parks appealed powerfully as the potential museums and classrooms for the popular study of the natural forces which made, and still are making, America, and of American fauna and flora. Here were set forth, in fascinating picture and lines so plain that none could fail to read and understand, the essentials of sciences whose real charm our rapid educational methods impart to few. This book is the logical outgrowth of a close study of the national parks, beginning with the inception of the new movement, from this point of view.

How free from the partisan considerations common in governmental organization was the birth of the movement is shown by an incident of Mr. Mather's inauguration into his assistant secretaryship. Secretary Lane had seen him at his desk and had started back to his own room. But he returned, looked in at the door, and asked:

"Oh, by the way, Steve, what are your politics?"

This book considers our national parks as they line up four years after the beginning of this movement. It shows them well started upon the long road to realization, with Congress, Government, and the people united toward a common end, with the schools and the universities interested, and, for the first time, with the railroads, the concessioners, the motoring interests, and many of the public-spirited educational and outdoor associations all pulling together under the inspiration of a recognized common motive.

Of course this triumph of organization, for it is no less, could not have been accomplished nearly so quickly without the assistance of the closing of Europe by the great war. Previous to 1915, Americans had been spending $300,000,000 a year in European travel. Nor could it have been accomplished at all if investigation and comparison had not shown that our national parks excel in supreme scenic quality and variety the combined scenery which is comfortably accessible in all the rest of the world together.

To get the situation at the beginning of our book into full perspective, it must be recognized that, previous to the beginning of our propaganda in 1915, the national parks, as such, scarcely existed in the public consciousness. Few Americans could name more than two or three of the fourteen existing parks. The Yosemite Valley and the Yellowstone alone were [Pg 24]generally known, but scarcely as national parks; most of the school geographies which mentioned them at all ignored their national character. The advertising folders of competing railroads were the principal sources of public knowledge, for few indeed asked for the compilation of rates and charges which the Government then sent in response to inquiries for information. The parks had practically no administration. The business necessarily connected with their upkeep and development was done by clerks as minor and troublesome details which distracted attention from more important duties; there was no one clerk whose entire concern was with the national parks. The American public still looked confidently upon the Alps as the supreme scenic area in the world, and hoped some day to see the Canadian Rockies.

Originally the motive in park-making had been unalloyed conservation. It is as if Congress had said: "Let us lock this up where no one can run away with it; we don't need it now, but some day it may be valuable." That was the instinct that led to the reservation of the Hot Springs of Arkansas in 1832, the first national park. Forty years later, when official investigation proved the truth of the amazing tales of Yellowstone's natural wonders, it was the instinct which led to the reservation of that largely unexplored area as the second national park. Seventeen years after Yellowstone, when newspapers and [Pg 25]scientific magazines recounted the ethnological importance of the Casa Grande Ruin in Arizona, it resulted in the creation of the third national park, notwithstanding that the area so conserved enclosed less than a square mile, which contained nothing of the kind and quality which to-day we recognize as essential to parkhood. This closed what may be regarded as the initial period of national parks conservation. It was wholly instinctive; distinctions, objectives, and policies were undreamed of.

Less than two years after Casa Grande, which, by the way, has recently been re-classed a national monument, what may be called the middle period began brilliantly with the creation, in 1890, of the Yosemite, the Sequoia, and the General Grant National Parks, all parks in the true sense of the word, and all of the first order of scenic magnificence. Nine years later Mount Rainier was added, and two years after that wonderful Crater Lake, both meeting fully the new standard.

What followed was human and natural. The term national park had begun to mean something in the neighborhoods of the parks. Yellowstone and Yosemite had long been household words, and the introduction of other areas to their distinguished company fired local pride in neighboring states. "Why should we not have national parks, too?" people asked. Congress, always the reflection of the popular will, and therefore not always abreast of the moment, was unprepared with reasons. Thus, during 1903 and[Pg 26] 1904, there were added to the list areas in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Oklahoma, which were better fitted for State parks than for association with the distinguished company of the nation's noblest.

A reaction followed and resulted in what we may call the modern period. Far-sighted men in and out of Congress began to compare and look ahead. No hint yet of the splendid destiny of our national parks, now so clearly defined, entered the minds of these men at this time, but ideas of selection, of development and utilization undoubtedly began to take form. At least, conservation, as such, ceased to become a sole motive. Insensibly Congress, or at least a few men of vision in Congress, began to take account of stock and figure on realization.

This healthy growth was helped materially by the public demand for the improvement of several of the national parks. No thought of appropriating money to improve the bathing facilities of Hot Springs had affected Congressional action for nearly half a century; it was enough that the curative springs had been saved from private ownership. Yellowstone was considered so altogether extraordinary, however, that Congress began in 1879 to appropriate yearly for its approach by road, and for the protection of its springs and geysers; but this was because Yellowstone appealed to the public sense of wonder. It took twenty years more for Congress to understand that the public sense of beauty was also worth appropriations. Yosemite had been a national park for nine years before it received a dollar, and then only when public demand for roads, trails, and accommodations became insistent.

But, once born, the idea took root and spread. It was fed by the press and magazine reports of the glories of the newer national parks, then attracting some public attention. It helped discrimination in the comparison of the minor parks created in 1903 and 1904 with the greater ones which had preceded. The realization that the parks must be developed at public expense sharpened Congressional judgment as to what areas should and should not become national parks.

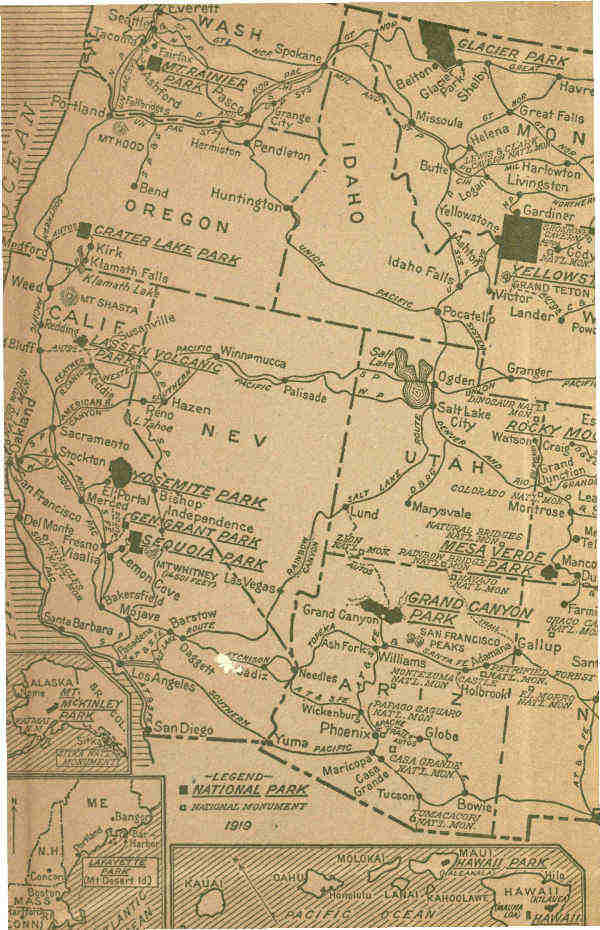

From that time on Congress has made no mistakes in selecting national parks. Mesa Verde became a park in 1905, Glacier in 1910, Rocky Mountain in 1915, Hawaii and Lassen Volcanic in 1916, Mount McKinley in 1917, and Lafayette and the Grand Canyon in 1919. From that time on Congress, most conservatively, it is true, has backed its judgment with increasing appropriations. And in 1916 it created the National Park Service, a bureau of the Department of the Interior, to administer them in accordance with a definite policy.

The distinction between the national forests and the national parks is essential to understanding. The national forests constitute an enormous domain [Pg 28]administered for the economic commercialization of the nation's wealth of lumber. Its forests are handled scientifically with the object of securing the largest annual lumber output consistent with the proper conservation of the future. Its spirit is commercial. The spirit of national park conservation is exactly opposite. It seeks no great territory—only those few spots which are supreme. It aims to preserve nature's handiwork exactly as nature made it. No tree is cut except to make way for road, trail or hotel to enable the visitor to penetrate and live among nature's secrets. Hunting is excellent in some of our national forests, but there is no game in the national parks; in these, wild animals are a part of nature's exhibits; they are protected as friends.

It follows that forests and parks, so different in spirit and purpose, must be handled wholly separately. Even the rangers and scientific experts have objects so opposite and different that the same individual cannot efficiently serve both purposes. High specialization in both services is essential to success.

THE NATIONAL PARKS AT A GLANCE

[Number, 18; total area, 10,739 square miles]

| NATIONAL PARKS IN ORDER OF CREATION |

LOCATION | AREA IN SQUARE MILES |

DISTINCTIVE CHARACTERISTICS |

| Hot Springs, 1832 | Middle Arkansas | 1-1⁄2 | 46 hot springs possessing curative properties—Many hotels and boarding houses—20 bath-houses under public control. |

| Yellowstone, 1872 | Northwestern Wyoming | 3,348 | More geysers than in all rest of world together—Boiling springs—Mud volcanoes—Petrified forests—Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, remarkable for gorgeous coloring—Large lakes—Many large streams and waterfalls—Greatest wild bird and animal preserve in world. |

| Sequoia, 1890 | Middle eastern California | 252 | The Big Tree National Park—12,000 sequoia trees over 10 feet in diameter, some 25 to 36 feet in diameter—Towering mountain ranges—Startling precipices—Large limestone cave. |

| Yosemite, 1890 | Middle eastern California | 1,125 | Valley of world-famed beauty—Lofty cliffs—Romantic vistas—Many waterfalls of extraordinary height—3 groves of big trees—High Sierra—Waterwheel falls. |

| General Grant, 1890 | Middle eastern California | 4 | Created to preserve the celebrated General Grant Tree, 35 feet in diameter—6 miles from Sequoia National Park. |

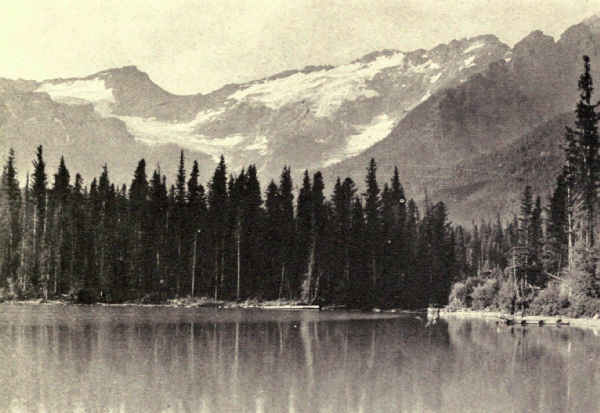

| Mount Rainier, 1899 | West central Washington | 324 | Largest accessible single peak glacier system—28 glaciers, some of large size—48 square miles of glacier, 50 to 500 feet thick—Wonderful subalpine wild flower fields. |

| Crater Lake, 1902 | Southwestern Oregon | 249 | Lake of extraordinary blue in crater of extinct volcano—Sides 1,000 feet high—Interesting lava formations. |

| Wind Cave, 1903 | South Dakota | 17 | Cavern having many miles of galleries and numerous chambers containing peculiar formations. |

| Platt, 1904 | S. Oklahoma | 1-1⁄3 | Many sulphur and other springs possessing medicinal value. |

| Sullys Hill, 1904 | North Dakota | 1-1⁄5 | Small park with woods, streams, and a lake—Is an important wild animal preserve. |

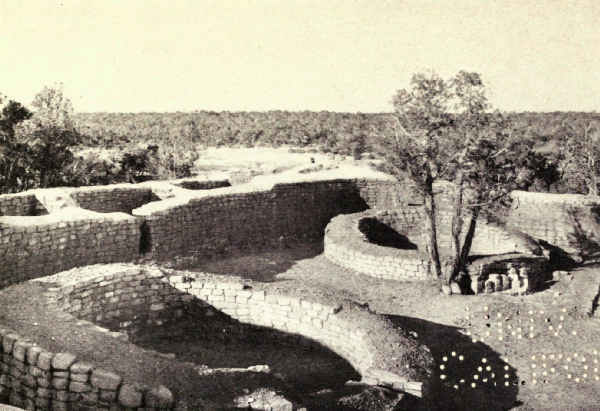

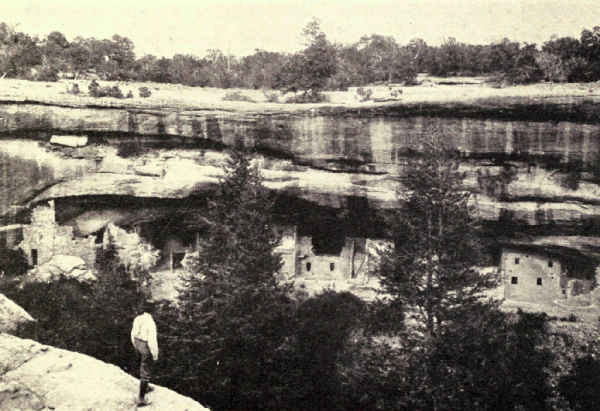

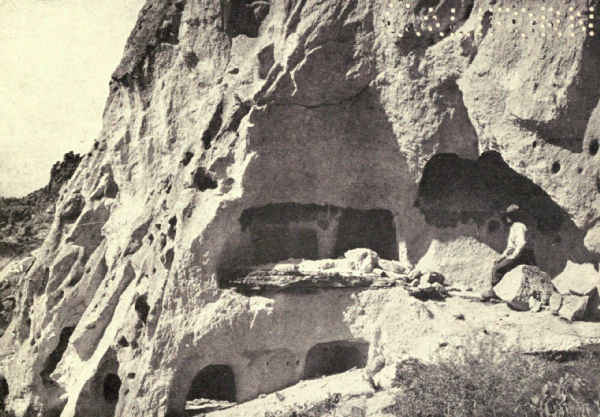

| Mesa Verde, 1906 | S.W. Colorado | 77 | Most notable and best preserved prehistoric cliff dwellings in United States, if not in the world. |

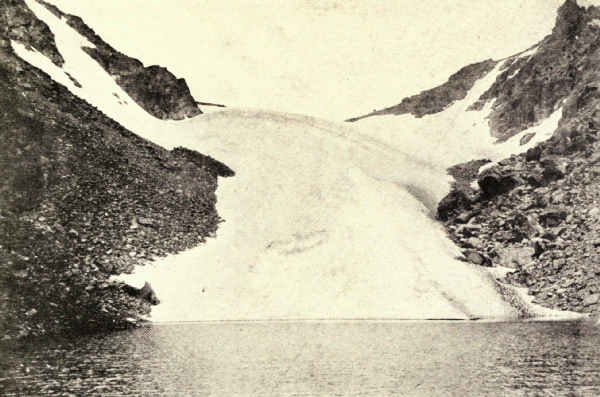

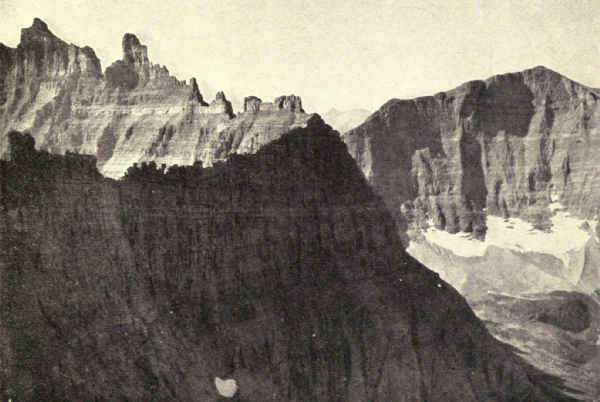

| Glacier, 1910 | Northwestern Montana | 1,534 | Rugged mountain region of unsurpassed Alpine character—250 glacier-fed lakes of romantic beauty—60 small glaciers—Sensational scenery of marked individuality. |

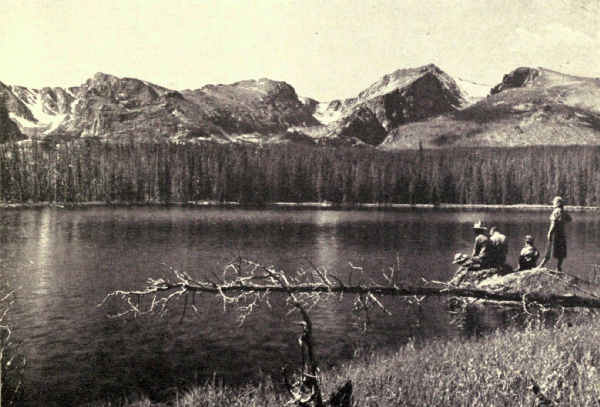

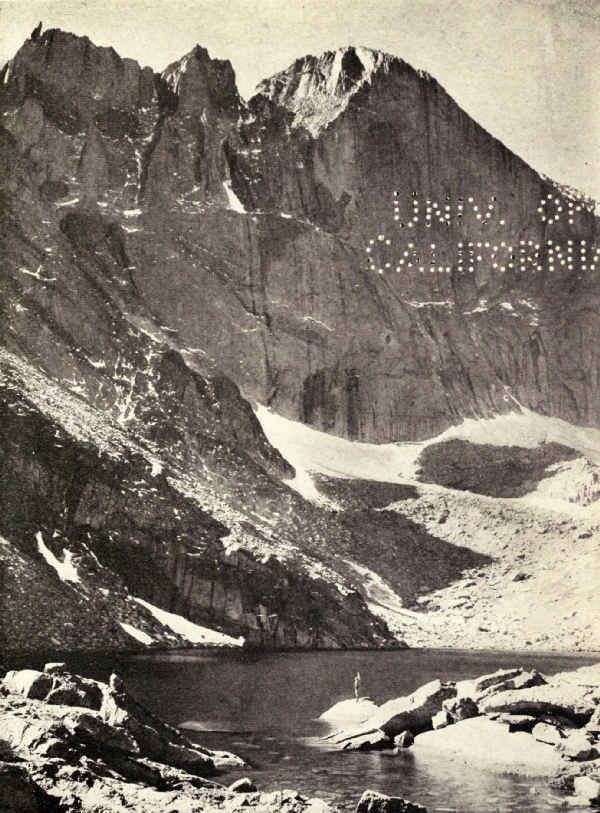

| Rocky Mountain, 1915 | North middle Colorado | 398 | Heart of the Rockies—Snowy range, peaks 11,000 to 14,250 feet altitude—Remarkable records of glacial period. |

| Hawaii, 1916 | Hawaiian Islands | 118 | Three separate volcanic areas—Kilauea and Mauna Loa on Hawaii; Haleakala on Maui. |

| Lassen Volcanic, 1916 | Northern California | 124 | Only active volcano in United States proper—Lassen Peak 10,465 feet—Cinder Cone 6,879 feet—Hot springs—Mud geysers. |

| Mount McKinley, 1917 | South central Alaska | 2,200 | Highest mountain in North America—Rises higher above surrounding country than any other mountain in world. |

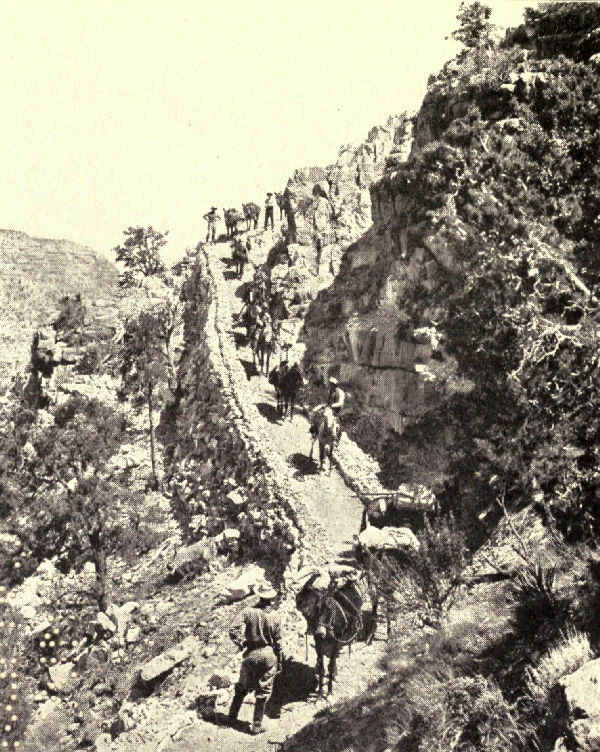

| Grand Canyon, 1919 | North central Arizona | 958 | The greatest example of erosion and the most sublime spectacle in the world—One mile deep and eight to twelve miles wide—Brilliantly colored. |

| Lafayette, 1919 | Maine Coast | 8 | The group of granite mountains on Mount Desert Island. |

Another distinction which should be made is the difference between a national park and a national monument. The one is an area of size created by Congress upon the assumption that it is a supreme example of its kind and with the purpose of developing it for public occupancy and enjoyment. The other is made by presidential proclamation to conserve an area or object which is historically, ethnologically, or scientifically important. Size is not considered, and development is not contemplated. The distinction is often lost in practice. Casa Grande is essentially a national monument, but had the status of a national park until 1918. The Grand Canyon, from every point of view a national park, was created a national monument and remained such until 1919.

The granite national parks are Yosemite, Sequoia, including the proposed Roosevelt Park, General Grant, Rocky Mountain, and Mount McKinley. Granite, as its name denotes, is granular in texture and appearance. It is crystalline, which means that it is imperfectly crystallized. It is composed of quartz, feldspar, and mica in varying proportions, and includes several common varieties which mineralogists distinguish scientifically by separate names.

Because of its great range and abundance, its presence at the core of mountain ranges where it is uncovered by erosion, its attractive coloring, its massiveness and its vigorous personality, it figures importantly in scenery of magnificence the world over. In color granite varies from light gray, when it shines like silver upon the high summits, to warm rose or dark gray, the reds depending upon the proportion of feldspar in its composition.

It produces scenic effects very different indeed from those resulting from volcanic and sedimentary rocks. While it bulks hugely in the higher mountains, running to enormous rounded masses below the level of the glaciers, and to jagged spires and pinnacled walls upon the loftiest peaks, it is found also in many regions of hill and plain. It is one of our commonest American rocks.

Much of the loftiest and noblest scenery of the world is wrought in granite. The Alps, the Andes, and the Himalayas, all of which are world-celebrated for their lofty grandeur, are prevailingly granite. They abound in towering peaks, bristling ridges, and terrifying precipices. Their glacial cirques are girt with fantastically toothed and pinnacled walls.

This is true of all granite ranges which are lofty enough to maintain glaciers. These are, in fact, the very characteristics of Alpine, Andean, Himalayan, Sierran, Alaskan, and Rocky Mountain summit landscape. It is why granite mountains are the favorites of those daring climbers whose ambition is to equal established records and make new ones; and this in turn is why some mountain neighborhoods become so much more celebrated than others which are quite as fine, or finer—because, I mean, of the publicity given to this kind of mountain climbing, and of the unwarranted assumption that the mountains associated with these exploits necessarily excel others in sublimity. As a matter of fact, the accident of fashion has even more to do with the fame of mountains than of men.

But by no means all granite mountains are lofty. The White Mountains, for example, which parallel our northeastern coast, and are far older than the Rockies and the Sierra, are a low granite range, with few of the characteristics of those mountains which lift their heads among the perpetual snows. On the contrary, they tend to rounded forested summits and knobby peaks. This results in part from a longer subjection[Pg 35] of the rock surface to the eroding influence of successive frosts and rains than is the case with high ranges which are perpetually locked in frost. Besides, the ice sheets which planed off the northern part of the United States lopped away their highest parts.

There are also millions of square miles of eroded granite which are not mountains at all. These tend to rolling surfaces.

The scenic forms assumed by granite will be better appreciated when one understands how it enters landscape. The principal one of many igneous rocks, it is liquefied under intense heat and afterward cooled under pressure. Much of the earth's crust was once underlaid by granites in a more or less fluid state. When terrific internal pressures caused the earth's crust to fold and make mountains, this liquefied granite invaded the folds and pushed close up under the highest elevations. There it cooled. Thousands of centuries later, when erosion had worn away these mountain crests, there lay revealed the solid granite core which frost and glacier have since transformed into the bristling ramparts of to-day's landscape.

Yosemite National Park, Middle Eastern California. Area, 1,125 Square Miles

The first emotion inspired by the sight of Yosemite is surprise. No previous preparation makes the mind ready for the actual revelation. The hardest preliminary reading and the closest study of photographs, even familiarity with other mountains as lofty, or loftier, fail to dull one's first astonishment.

Hard on the heels of astonishment comes realization of the park's supreme beauty. It is of its own kind, without comparison, as individual as that of the Grand Canyon or the Glacier National Park. No single visit will begin to reveal its sublimity; one must go away and return to look again with rested eyes. Its devotees grow in appreciative enjoyment with repeated summerings. Even John Muir, life student, interpreter, and apostle of the Sierra, confessed toward the close of his many years that the Valley's quality of loveliness continued to surprise him at each renewal.

And lastly comes the higher emotion which is born of knowledge. It is only when one reads in these inspired rocks the stirring story of their making[Pg 37] that pleasure reaches its fulness. The added joy of the collector upon finding that the unsigned canvas, which he bought only for its beauty, is the lost work of a great master, and was associated with the romance of a famous past is here duplicated. Written history never was more romantic nor more graphically told than that which Nature has inscribed upon the walls of these vast canyons, domes and monoliths in a language which man has learned to read.

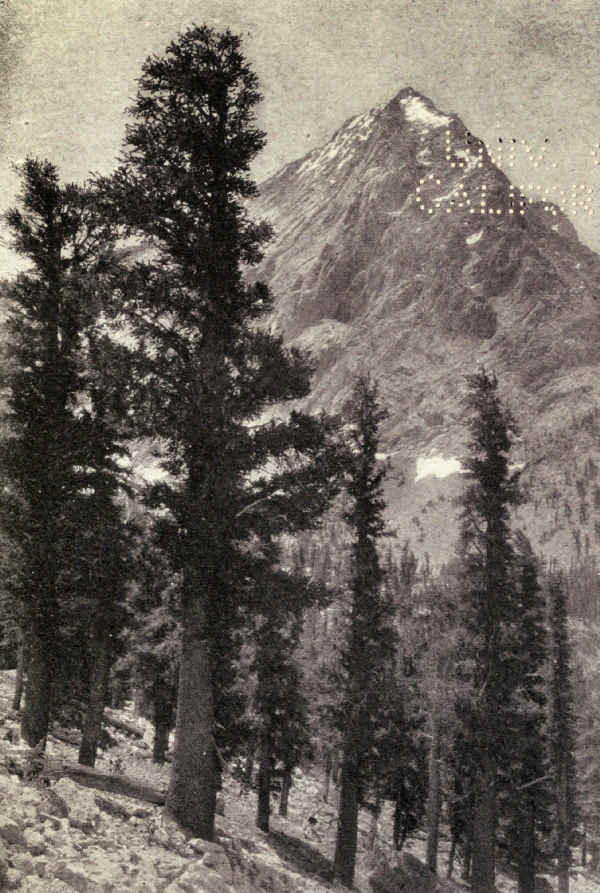

The Yosemite National Park lies on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, nearly east of San Francisco. The snowy crest of the Sierra, bellying irregularly eastward to a climax among the jagged granites and gale-swept glaciers of Mount Lyell, forms its eastern boundary. From this the park slopes rapidly thirty miles or more westward to the heart of the warm luxuriant zone of the giant sequoias. This slope includes in its eleven hundred and twenty-five square miles some of the highest scenic examples in the wide gamut of Sierra grandeur. It is impossible to enter it without exaltation of spirit, or describe it without superlative.

A very large proportion of Yosemite's visitors see nothing more than the Valley, yet no consideration is tenable which conceives the Valley as other than a small part of the national park. The two are inseparable. One does not speak of knowing the Louvre who[Pg 38] has seen only the Venus de Milo, or St. Mark's who has looked only upon its horses.

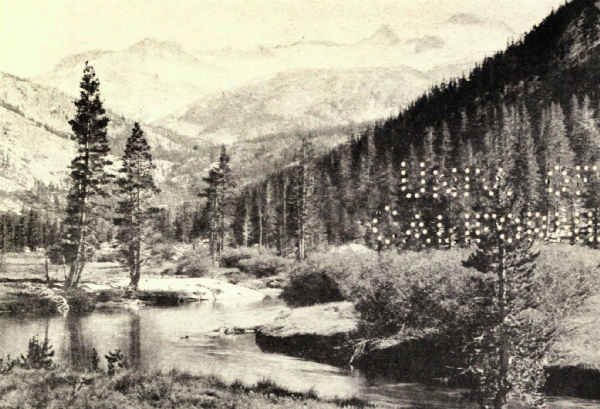

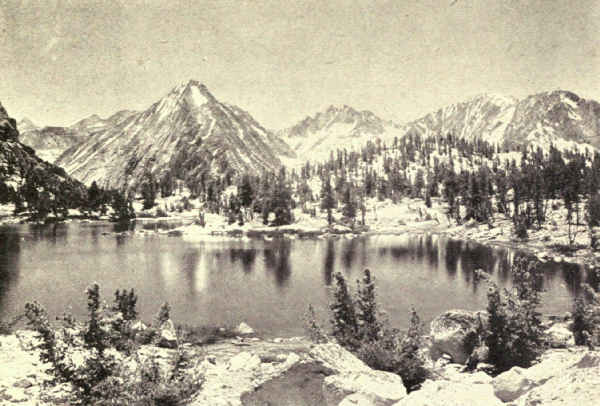

Considered as a whole, the park is a sagging plain of solid granite, hung from Sierra's saw-toothed crest, broken into divides and transverse mountain ranges, punctured by volcanic summits, gashed and bitten by prehistoric glaciers, dotted near its summits with glacial lakes, furrowed by innumerable cascading streams which combine in singing rivers, which, in turn, furrow greater canyons, some of majestic depth and grandeur. It is a land of towering spires and ambitious summits, serrated cirques, enormous isolated rock masses, rounded granite domes, polished granite pavements, lofty precipices, and long, shimmering waterfalls.

Bare and gale-ridden near its crest, the park descends in thirty miles through all the zones and gradations of animal and vegetable life through which one would pass in travelling from the ice-bound shores of the Arctic Ocean the continent's length to Mariposa Grove. Its tree sequence tells the story. Above timber-line there are none but inch-high willows and flat, piney growths, mingled with tiny arctic flowers, which shrink in size with elevation; even the sheltered spots on Lyell's lofty summit have their colored lichens, and their almost microscopic bloom. At timber-line, low, wiry shrubs interweave their branches to defy the gales, merging lower down into a tangle of many stunted growths, from which spring twisted pines and contorted spruces, which the winds curve to leeward[Pg 39] or bend at sharp angles, or spread in full development as prostrate upon the ground as the mountain lion's skin upon the home floor of his slayer.

Descending into the great area of the Canadian zone, with its thousand wild valleys, its shining lakes, its roaring creeks and plunging rivers, the zone of the angler, the hiker, and the camper-out, we enter forests of various pines, of silver fir, hemlock, aged hump-backed juniper, and the species of white pine which Californians wrongly call tamarack.

This is the paradise of outdoor living; it almost never rains between June and October. The forests fill the valley floors, thinning rapidly as they climb the mountain slopes; they spot with pine green the broad, shining plateaus, rooting where they find the soil, leaving unclothed innumerable glistening areas of polished uncracked granite; a striking characteristic of Yosemite uplands. From an altitude of seven or eight thousand feet, the Canadian zone forests begin gradually to merge into the richer forests of the Transition zone below. The towering sugar pine, the giant yellow pine, the Douglas fir, and a score of deciduous growths—live oaks, bays, poplars, dogwoods, maples—begin to appear and become more frequent with descent, until, two thousand feet or more below, they combine into the bright stupendous forests where, in specially favored groves, King Sequoia holds his royal court.

Wild flowers, birds, and animals also run the gamut of the zones. Among the snows and alpine[Pg 40] flowerets of the summits are found the ptarmigan and rosy finch of the Arctic circle, and in the summit cirques and on the shores of the glacial lakes whistles the mountain marmot.

The richness and variety of wild flower life in all zones, each of its characteristic kind, astonishes the visitor new to the American wilderness. Every meadow is ablaze with gorgeous coloring, every copse and sunny hollow, river bank and rocky bottom, becomes painted in turn the hue appropriate to the changing seasons. Now blues prevail in the kaleidoscopic display, now pinks, now reds, now yellows. Experience of other national parks will show that the Yosemite is no exception; all are gardens of wild flowers.

The Yosemite and the Sequoia are, however, the exclusive possessors among the parks of a remarkably showy flowering plant, the brilliant, rare, snow-plant. So luring is the red pillar which the snow-plant lifts a foot or more above the shady mould, and so easily is it destroyed, that, to keep it from extinction, the government fines covetous visitors for every flower picked.

The birds are those of California—many, prolific, and songful. Ducks raise their summer broods fearlessly on the lakes. Geese visit from their distant homes. Cranes and herons fish the streams. Every tree has its soloist, every forest its grand chorus. The glades resound with the tapping of woodpeckers. The whirr of startled wings accompanies passage through every wood. To one who has lingered in the forests[Pg 41] to watch and to listen, it is hard to account for the wide-spread fable that the Yosemite is birdless. No doubt, happy talkative tourists, in companies and regiments, afoot and mounted, drive bird and beast alike to silent cover—and comment on the lifeless forests. "The whole range, from foothill to summit, is shaken into song every summer," wrote John Muir, to whom birds were the loved companions of a lifetime of Sierra summers, "and, though low and thin in winter, the music never ceases."

There are two birds which the unhurried traveller will soon know well. One is the big, noisy, gaudy Clark crow, whose swift flight and companionable squawk are familiar to all who tour the higher levels. The other is the friendly camp robber, who, with encouragement, not only will share your camp luncheon, but will gobble the lion's share.

Of the many wild animals, ranging in size from the great, powerful, timid grizzly bear, now almost extinct here, whose Indian name, by the way, is Yosemite, to the tiny shrew of the lowlands, the most frequently seen are the black or brown bear, and the deer, both of which, as compared with their kind in neighborhoods where hunting is permitted, are unterrified if not friendly. Notwithstanding its able protection, the Yosemite will need generations to recover from the hideous slaughter which, in a score or two of years, denuded America of her splendid heritage of wild animal life.

Of the several carnivora, the coyote alone is [Pg 42]occasionally seen by visitors. Wolves and mountain lions, prime enemies of the deer and mountain sheep, are hard to find, even when officially hunted in the winter with dogs trained for the purpose.

The Yosemite Valley is the heart of the national park. Not only is it the natural entrance and abiding place, the living-room, so to speak, the central point from which all parts of the park are most comfortably accessible; it is also typical in some sense of the Sierra as a whole, and is easily the most beautiful valley in the world.

It is difficult to analyze the quality of the Valley's beauty. There are, as Muir says, "many Yosemites" in the Sierra. The Hetch Hetchy Valley, in the northern part of the park, which bears the same relation to the Tuolumne River that the Yosemite Valley bears to the Merced, is scarcely less in size, richness, and the height and magnificence of its carved walls. Scores of other valleys, similar except for size, abound north and south, which are, scientifically and in Muir's meaning, Yosemites; that is, they are pauses in their rivers' headlong rush, once lakes, dug by rushing waters, squared and polished by succeeding glaciers, chiselled and ornamented by the frosts and rains which preceded and followed the glaciers. Muir is right, for all these are Yosemites; but he is wrong, for there is only one Yosemite.

It is not the giant monoliths that establish the incomparable Valley's world supremacy; Hetch Hetchy, Tehipite, Kings, and others have their giants, too. It is not its towering, perpendicular, serrated walls; the Sierra has elsewhere, too, an overwhelming exhibit of titanic granite carvings. It is not its waterfalls, though these are the highest, by far, in the world, nor its broad, peaceful bottoms, nor its dramatic vistas, nor the cavernous depths of its tortuous tributary canyons. Its secret is selection and combination. Like all supremacy, Yosemite's lies in the inspired proportioning of carefully chosen elements. Herein is its real wonder, for the more carefully one analyzes the beauty of the Yosemite Valley, the more difficult it is to conceive its ensemble the chance of Nature's functioning rather than the master product of supreme artistry.

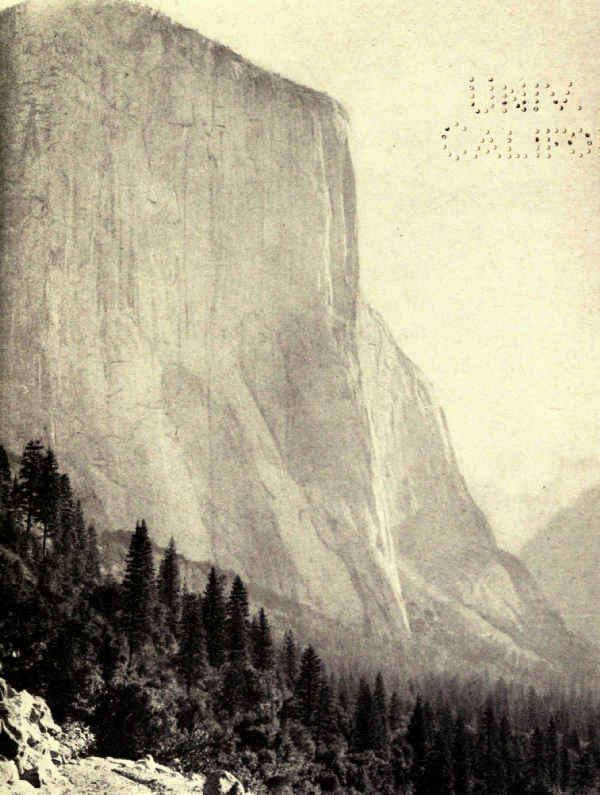

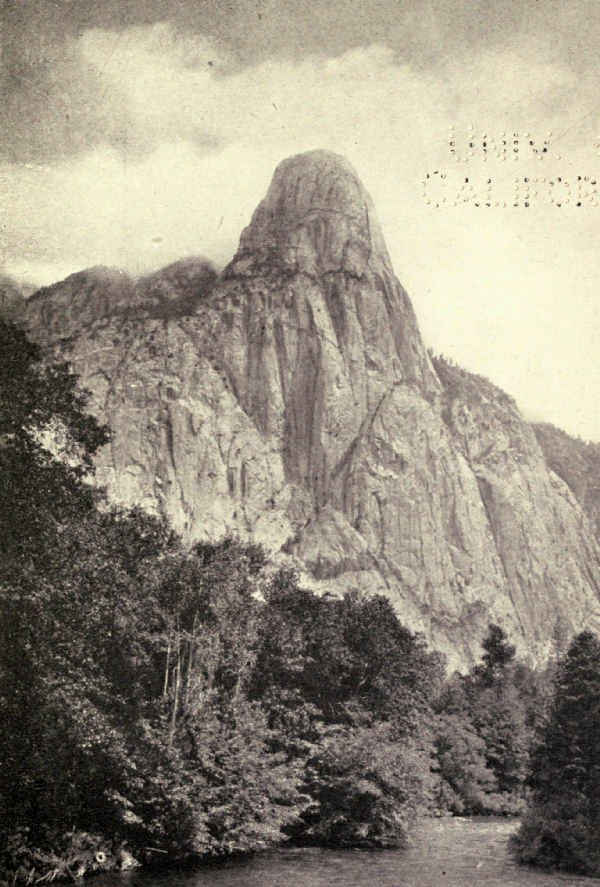

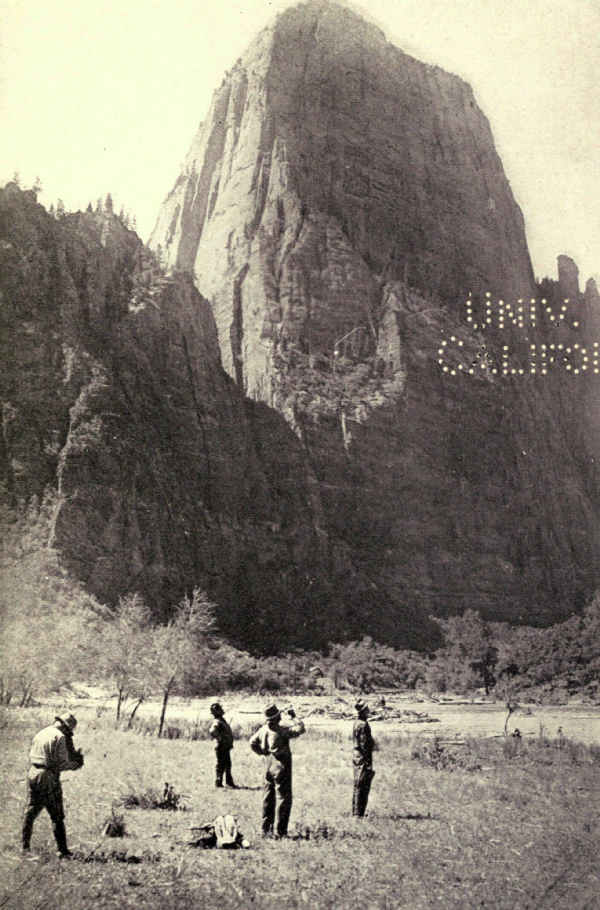

Entrance to the Yosemite by train is from the west, by automobile from east and west both. From whatever direction, the Valley is the first objective, for the hotels are there. It is the Valley, then, which we must see first. Nature's artistic contrivance is apparent even in the entrance. The train-ride from the main line at Merced is a constant up-valley progress, from a hot, treeless plain to the heart of the great, cool forest. Expectation keeps pace. Changing to automobile at El Portal, one quickly enters the park. A few miles of forest and behold—the Gates of the Valley. El Capitan, huge, glistening, rises upon the left, 3,000 feet above the valley floor. At first sight[Pg 44] its bulk almost appalls. Opposite upon the right Cathedral Rocks support the Bridal Veil Fall, shimmering, filmy, a fairy thing. Between them, in the distance, lies the unknown.

Progress up the valley makes constantly for climax. Seen presently broadside on, El Capitan bulks double, at least. Opposite, the valley bellies. Cathedral Rocks and the mediæval towers known as Cathedral Spires, are enclosed in a bay, which culminates in the impressive needle known as Sentinel Rock—all richly Gothic. Meantime the broadened valley, another strong contrast in perfect key, delightfully alternates with forest and meadow, and through it the quiet Merced twists and doubles like a glistening snake. And then we come to the Three Brothers.

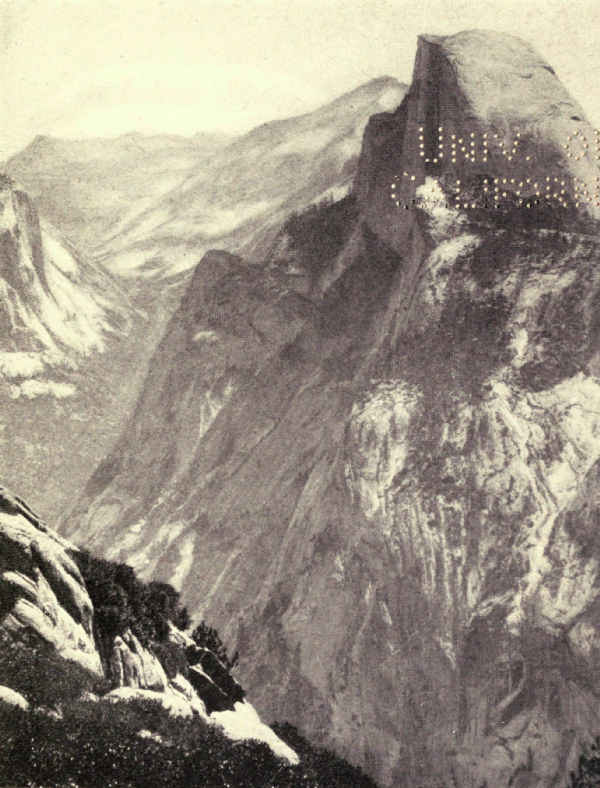

Already some notion of preconception has possessed the observer. It could not have been chance which set off the filmy Bridal Veil against El Capitan's bulk; which designed the Gothic climax of Sentinel Rock; which wondrously proportioned the consecutive masses of the Three Brothers; which made El Capitan, now looked back upon against a new background, a new and appropriate creation, a thing of brilliance and beauty instead of bulk, mighty of mass, powerful in shape and poise, yet mysteriously delicate and unreal. As we pass on with rapidly increasing excitement to the supreme climax at the Valley's head, where gather together Glacier Point, Yosemite Falls of unbelievable height and graciousness, the Royal Arches, manifestly a carving, the gulf-like entrances of Tenaya and the Merced Canyons, and above all, and pervading all, the distinguished mysterious personality of Half Dome, presiding priest of this Cathedral of Beauty, again there steals over us the uneasy suspicion of supreme design. How could Nature have happened upon the perfect composition, the flawless technique, the divine inspiration of this masterpiece of more than human art? Is it not, in fact, the master temple of the Master Architect?

To appreciate the Valley we must consider certain details. It is eight miles long, and from half a mile to a mile wide. Once prehistoric Lake Yosemite, its floor is as level as a ball field, and except for occasional meadows, grandly forested. The sinuous Merced is forested to its edges in its upper reaches, but lower down occasionally wanders through broad, blooming opens. The rock walls are dark pearl-hued granite, dotted with pines wherever clefts or ledges exist capable of supporting them; even El Capitan carries its pine-tree half way up its smooth precipice. Frequently the walls are sheer; they look so everywhere. The valley's altitude is 4,000 feet. The walls rise from 2,000 to 6,000 feet higher; the average is a little more than 3,000 feet above the valley floor; Sentinel Dome and Mount Watkins somewhat exceed 4,000 feet; Half Dome nearly attains 5,000 feet; Cloud's Rest soars nearly 6,000 feet.

Two large trench-like canyons enter the valley at its head, one on either side of Half Dome. Tenaya Canyon enters from the east in line with the valley,[Pg 46] looking as if it were the Valley's upper reach. Merced Canyon enters from the south after curving around the east and south sides of Half Dome. Both are extremely deep. Half Dome's 5,000 feet form one side of each canyon; Mount Watkin's 4,300 feet form the north side of Tenaya Canyon, Glacier Point's 3,200 feet the west side of Merced Canyon. Both canyons are superbly wooded at their outlets, and lead rapidly up to timber-line. Both carry important trails from the Valley floor to the greater park above the rim.

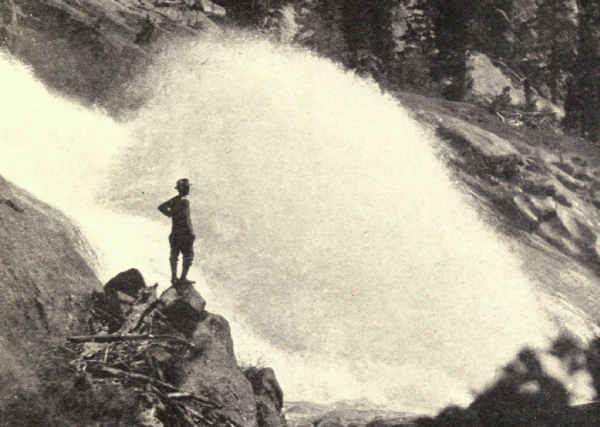

To this setting add the waterfalls and the scene is complete. They are the highest in the world. Each is markedly individualized; no two resemble each other. Yet, with the exception of the Vernal Fall, all have a common note; all are formed of comparatively small streams dropping from great heights; all are wind-blown ribbons ending in clouds of mist. They are so distributed that one or more are visible from most parts of the Valley and its surrounding rim. More than any other feature, they differentiate and distinguish the Yosemite.

The first of the falls encountered, Bridal Veil, is a perfect example of the valley type. A small stream pouring over a perpendicular wall drops six hundred and twenty feet into a volume of mist. The mist, of course, is the bridal veil. How much of the water reaches the bottom as water is a matter of interesting speculation. This and the condensed mists reach the river through a delta of five small brooks. As a spectacle the Bridal Veil Fall is unsurpassed. The delicacy of its beauty, even in the high water of early summer, is unequalled by any waterfall I have seen. A rainbow frequently gleams like a colored rosette in the massed chiffon of the bride's train. So pleasing are its proportions that it is difficult to believe the fall nearly four times the height of Niagara.

The Ribbon Fall, directly opposite Bridal Veil, a little west of El Capitan, must be mentioned because for a while in early spring its sixteen hundred foot drop is a spectacle of remarkable grandeur. It is merely the run of a snow-field which disappears in June. Thereafter a dark perpendicular stain on the cliff marks its position. Another minor fall, this from the south rim, is that of Sentinel Creek. It is seen from the road at the right of Sentinel Rock, dropping five hundred feet in one leap of several which aggregate two thousand feet.

Next in progress come Yosemite Falls, loftiest by far in the world, a spectacle of sublimity. These falls divide with Half Dome the honors of the upper Valley. The tremendous plunge of the Upper Fall, and the magnificence of the two falls in apparent near continuation as seen from the principal points of elevation on the valley floor, form a spectacle of extraordinary distinction. They vie with Yosemite's two great rocks, El Capitan and Half Dome, for leadership among the individual scenic features of the continent.

The Upper Fall pours over the rim at a point nearly twenty-six hundred feet above the valley floor. Its sheer drop is fourteen hundred and thirty feet, the[Pg 48] equal of nine Niagaras. Two-fifths of a mile south of its foot, the Lower Fall drops three hundred and twenty feet more. From the crest of the Upper Fall to the foot of the Lower Fall lacks a little of half a mile. From the foot of the Lower Fall, after foaming down the talus, Yosemite Creek, seeming a ridiculously small stream to have produced so monstrous a spectacle, slips quietly across a half mile of level valley to lose itself in the Merced.

From the floods of late May when the thunder of falling water fills the valley and windows rattle a mile away, to the October drought when the slender ribbon is little more than mist, the Upper Yosemite Fall is a thing of many moods and infinite beauty. Seen from above and opposite at Glacier Point, sideways and more distantly from the summit of Cloud's Rest, straight on from the valley floor, upwards from the foot of the Lower Fall, upwards again from its own foot, and downwards from the overhanging brink toward which the creek idles carelessly to the very step-off of its fearful leap, the Fall never loses for a moment its power to amaze. It draws and holds the eye as the magnet does the iron.

Looking up from below one is fascinated by the extreme leisureliness of its motion. The water does not seem to fall; it floats; a pebble dropped alongside surely would reach bottom in half the time. Speculating upon this appearance, one guesses that the air retards the water's drop, but this idea is quickly dispelled by the observation that the solid inner body[Pg 49] drops no faster than the outer spray. It is long before the wondering observer perceives that he is the victim of an illusion; that the water falls normally; that it appears to descend with less than natural speed only because of the extreme height of the fall, the eye naturally applying standards to which it has been accustomed in viewing falls of ordinary size.

On windy days the Upper Fall swings from the brink like a pendulum of silver and mist. Back and forth it lashes like a horse's tail. The gusts lop off puffy clouds of mist which dissipate in air. Muir tells of powerful winter gales driving head on against the cliff, which break the fall in its middle and hold it in suspense. Once he saw the wind double the fall back over its own brink. Muir, by the way, once tried to pass behind the Upper Fall at its foot, but was nearly crushed.

By contrast with the lofty temperamental Upper Fall, the Lower Fall appears a smug and steady pigmy. In such company, for both are always seen together, it is hard to realize that the Lower Fall is twice the height of Niagara. Comparing Yosemite's three most conspicuous features, these gigantic falls seem to appeal even more to the imagination than to the sense of beauty. El Capitan, on the other hand, suggests majesty, order, proportion, and power; it has its many devotees. Half Dome suggests mystery; to many it symbolizes worship. Of these three, Half Dome easily is the most popular.

Three more will complete the Valley's list of notable[Pg 50] waterfalls. All of these lie up the Merced Canyon. Illilouette, three hundred and seventy feet in height, enters from the west, a frothing fall of great beauty, hard to see. Vernal and Nevada Falls carry the Merced River over steep steps in its rapid progress from the upper levels to the valley floor. The only exception to the valley type, Vernal Fall, which some consider the most beautiful of all, and which certainly is the prettiest, is a curtain of water three hundred and seventeen feet high, and of pleasing breadth. The Nevada Fall, three-fifths of a mile above, a majestic drop of nearly six hundred feet, shoots watery rockets from its brink. It is full-run, powerful, impressive, and highly individualized. With many it is the favorite waterfall of Yosemite.

In sharp contrast with these valley scenes is the view from Glacier Point down into the Merced and Tenaya Canyons, and out over the magical park landscape to the snow-capped mountains of the High Sierra. Two trails lead from the valley up to Glacier Point, and high upon the precipice, three thousand feet above the valley floor, is a picturesque hotel; it is also reached by road. Here one may sit at ease on shady porches and overlook one of the most extended, varied and romantic views in the world of scenery. One may take dinner on this porch and have sunset served with dessert and the afterglow with coffee.

Here again one is haunted by the suggestion of artistic intention, so happy is the composition of this extraordinary picture. The foreground is the dark,[Pg 51] tremendous gulf of Merced Canyon, relieved by the silver shimmer of Vernal and Nevada Falls. From this in middle distance rises, in the centre of the canvas, the looming tremendous personality of Half Dome, here seen in profile strongly suggesting a monk with outstretched arms blessing the valley at close of day. Beyond stretches the horizon of famous, snowy, glacier-shrouded mountains, golden in sunset glow.

Every summer many thousands of visitors gather in Yosemite. Most of them, of course, come tourist-fashion, to glimpse it all in a day or two or three. A few thousands come for long enough to taste most of it, or really to see a little. Fewer, but still increasingly many, are those who come to live a little with Yosemite; among these we find the lovers of nature, the poets, the seers, the dreamers, and the students.

Living is very pleasant in the Yosemite. The freedom from storm during the long season, the dry warmth of the days and the coldness of the nights, the inspiration of the surroundings and the completeness of the equipment for the comfort of visitors make it extraordinary among mountain resorts. There is a hotel in the Valley, and another upon the rim at Glacier Point. There are three large hotel-camps in the Valley, where one may have hotel comforts under canvas at camp prices. Two of these hotel-camps possess swimming pools, dancing pavilions, tennis[Pg 52] courts electrically lighted for night play, hot and cold-water tubs and showers, and excellent table service. One of the hotel-camps, the largest, provides evening lectures, song services, and a general atmosphere suggestive of Chatauqua. Still a third is for those who prefer quiet retirement and the tradition of old-fashioned camp life.

Above the valley rim, besides the excellent hotel upon Glacier Point, there are at this writing hotel-camps equipped with many hotel comforts, including baths, at such outlying points as Merced Lake and Tenaya Lake; the former centering the mountain climbing and trout fishing of the stupendous region on the southwest slope of the park, and the latter the key to the entire magnificent region of the Tuolumne. These camps are reached by mountain trail, Tenaya Lake Camp also by motor road. The hotel-camp system is planned for wide extension as growing demand warrants. There are also hotels outside park limits on the south and west which connect with the park roads and trails.

The roads, by the way, are fair. Three enter from the west, centering at Yosemite Village in the Valley; one from the south by way of the celebrated Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias; one from El Portal, terminus of the Yosemite Railway; and one from the north, by way of several smaller sequoia groves, connecting directly with the Tioga Road.

Above the valley rim and north of it, the Tioga Road crosses the national park and emerges at Mono[Pg 53] Lake on the east, having crossed the Sierra over Tioga Pass on the park boundary. The Tioga Road, which was built in 1881, on the site of the Mono Trail, to connect a gold mine west of what has since become the national park with roads east of the Sierra, was purchased in 1915 by patriotic lovers of the Yosemite and given to the Government. The mine having soon failed, the road had been impassable for many years. Repaired with government money it has become the principal highway of the park and the key to its future development. The increase in motor travel to the Yosemite from all parts of the country which began the summer following the Great War, has made this gift one of growing importance. It affords a new route across the Sierra.