Captain Mayne Reid

"The Ocean Waifs"

Chapter One.

The Albatross.

The “vulture of the sea,” borne upon broad wing, and wandering over the wide Atlantic, suddenly suspends his flight to look down upon an object that has attracted his attention.

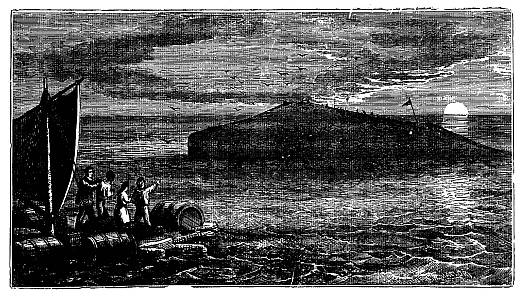

It is a raft, with a disc not much larger than a dining-table, constructed out of two small spars of a ship,—the dolphin-striker and spritsail yard,—with two broad planks and some narrower ones lashed crosswise, and over all two or three pieces of sail-cloth carelessly spread.

Slight as is the structure, it is occupied by two individuals,—a man and a boy. The latter is lying along the folds of the sail-cloth, apparently asleep. The man stands erect, with his hand to his forehead, shading the sun from his eyes, and scanning the surface of the sea with inquiring glances.

At his feet, lying among the creases of the canvas, are a handspike, a pair of boat oars, and an axe. Nothing more is perceptible of the raft, even to the keen eye of the albatross.

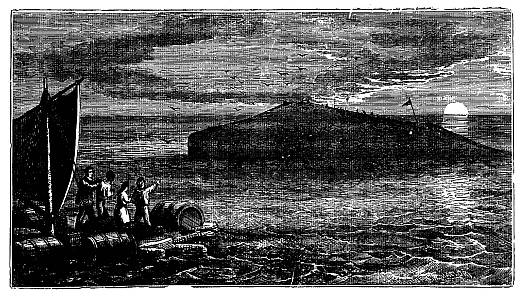

The bird continues its flight towards the west. Ten miles farther on it once more poises itself on soaring wing, and directs its glance downward.

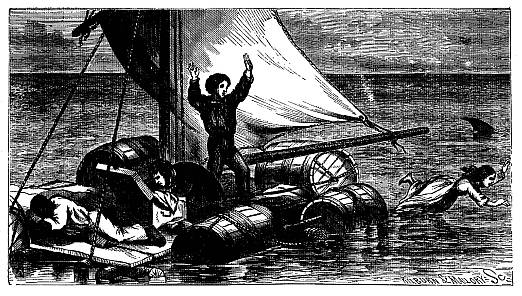

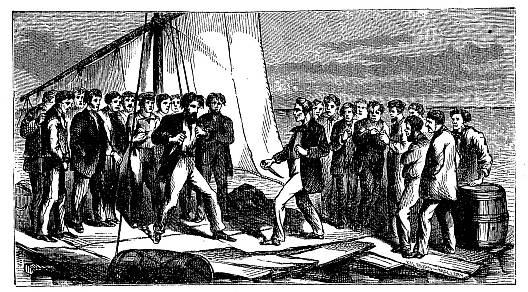

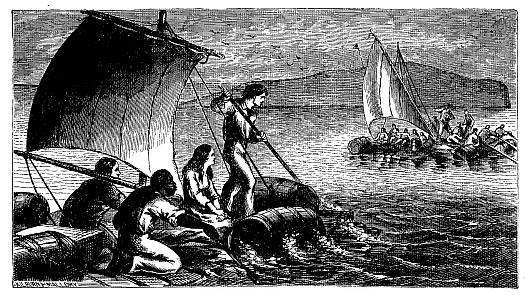

Another raft is seen motionless upon the calm surface of the sea, but differing from the former in almost everything but the name. It is nearly ten times as large; constructed out of the masts, yards, hatches, portions of the bulwarks, and other timbers of a ship; and rendered buoyant by a number of empty water-casks lashed along its edges. A square of canvas spread between two extemporised masts, a couple of casks, an empty biscuit-box, some oars, handspikes, and other maritime implements, lie upon the raft; and around these are more than thirty men, seated, standing, lying,—in short, in almost every attitude.

Some are motionless, as if asleep; but there is that in their prostrate postures, and in the wild expression of their features, that betokens rather the sleep of intoxication. Others, by their gestures and loud, riotous talk, exhibit still surer signs of drunkenness; and the tin cup, reeking with rum, is constantly passing from hand to hand. A few, apparently sober, but haggard and hungry-like, sit or stand erect upon the raft, casting occasional glances over the wide expanse, with but slight show of hope, fast changing to despair.

Well may the sea-vulture linger over this group, and contemplate their movements with expectant eye. The instincts of the bird tell him, that ere long he may look forward to a bountiful banquet!

Ten miles farther to the west, though unseen to those upon the raft, the far-piercing gaze of the albatross detects another unusual object upon the surface of the sea. At this distance it appears only a speck not larger than the bird itself, though in reality it is a small boat,—a ship’s gig,—in which six men are seated. There has been no attempt to hoist a sail; there is none in the gig. There are oars, but no one is using them. They have been dropped in despair; and the boat lies becalmed just as the two rafts. Like them, it appears to be adrift upon the ocean.

Could the albatross exert a reasoning faculty it would know that these various objects indicated a wreck. Some vessel has either foundered and gone to the bottom, or has caught fire and perished in the flames.

Ten miles to the eastward of the lesser raft might be discovered truer traces of the lost ship. There might be seen the débris of charred timbers, telling that she has succumbed, not to the storm, but to fire; and the fragments, scattered over the circumference of a mile, disclose further that the fire ended abruptly in some terrible explosion.

Upon the stern of the gig still afloat may be read the name Pandora. The same word may be seen painted on the water-casks buoying up the big raft; and on the two planks forming the transverse pieces of the lesser one appears Pandora in still larger letters: for these were the boards that exhibited the name of the ship on each side of her bowsprit, and which had been torn off to construct the little raft by those who now occupy it.

Beyond doubt the lost ship was the Pandora.

Chapter Two.

Ship on Fire.

The story of the Pandora has been told in all its terrible details. A slave-ship, fitted out in England, and sailing from an English port,—alas! not the only one by scores,—manned by a crew of ruffians, scarce two of them owning to the same nationality. Such was the bark Pandora.

Her latest and last voyage was to the slave coast, in the Gulf of Guinea. There, having shipped five hundred wretched beings with black skins,—“bales” as they are facetiously termed by the trader in human flesh,—she had started to carry her cargo to that infamous market,—ever open in those days to such a commodity,—the barracoons of Brazil.

In mid-ocean she had caught fire,—a fire that could not be extinguished. In the hurry and confusion of launching the boats the pinnace proved to be useless; and the longboat, stove in by the falling of a cask, sank to the bottom of the sea. Only the gig was found available; and this, seized upon by the captain, the mate, and four others, was rowed off clandestinely in the darkness.

The rest of the crew, over thirty in number, succeeded in constructing a raft; and but a few seconds after they had pushed off from the sides of the ship, a barrel of gunpowder ignited by the flames, completed the catastrophe.

But what became of the cargo? Ah! that is indeed a tale of horror.

Up to the last moment those unfortunate beings had been kept under hatches, under a grating that had been fastened down with battens. They would have been left in that situation to be stifled in their confinement by the suffocating smoke, or burnt alive amid the blazing timbers, but for one merciful heart among those who were leaving the ship. An axe uplifted by the arm of a brave youth—a mere boy—struck off the confining cleats, and gave the sable sufferers access to the open air.

Alas! it was scarce a respite to these wretched creatures,—only a choice between two modes of death. They escaped from the red flames but to sink into the dismal depths of the ocean,—hundreds meeting with a fate still more horrible: for there were not less than that number, and all became the prey of those hideous sea-monsters, the sharks.

Of all that band of involuntary emigrants, in ten minutes after the blowing up of the bark, there was not one above the surface of the sea! Those of them that could not swim had sunk to the bottom, while a worse fate had befallen those that could,—to fill the maws of the ravenous monsters that crowded the sea around them! At the period when our tale commences, several days had succeeded this tragical event; and the groups we have described, aligned upon a parallel of latitude, and separated one from another by a distance of some ten or a dozen miles, will be easily recognised.

The little boat lying farthest west was the gig of the Pandora, containing her brutal captain, his equally brutal mate, the carpenter, and three others of the crew, that had been admitted as partners in the surreptitious abstraction. Under cover of the darkness they had made their departure; but long before rowing out of gun-shot they had heard the wild denunciations and threats hurled after them by their betrayed associates.

The ruffian crew occupied the greater raft; but who were the two individuals who had intrusted themselves to that frail embarkation,—seemingly so slight that a single breath of wind would scatter it into fragments, and send its occupants to the bottom of the sea? Such in reality would have been their fate, had a storm sprung up at that moment; but fortunately for them the sea was smooth and calm,—as it had been ever since the destruction of the ship.

But why were they thus separated from the others of the crew: for both man and boy had belonged to the forecastle of the Pandora?

The circumstance requires explanation, and it shall be briefly given. The man was Ben Brace,—the bravest and best sailor on board the slave-bark, and one who would not have shipped in such a craft but for wrongs he had suffered while in the service of his country, and that had inducted him into a sort of reckless disposition, of which, however, he had long since repented.

The boy had also been the victim of a similar disposition. Longing to see foreign lands, he had run away to sea; and by an unlucky accident, through sheer ignorance of her character, had chosen the Pandora in which to make his initiatory voyage. From the cruel treatment he had been subjected to on board the bark, he had reason to see his folly. Irksome had been his existence from the moment he set foot on the deck of the Pandora; and indeed it would have been scarce endurable but for the friendship of the brave sailor Brace, who, after a time, had taken him under his especial protection. Neither of them had any feelings in common with the crew with whom they had become associated; and it was their intention to escape from such vile companionship as soon as an opportunity should offer.

The destruction of the bark would not have given that opportunity. On the contrary, it rendered it all the more necessary to remain with the others, and share the chances of safety offered by the great raft. Slight as these might be, they were still better than those that might await them, exposed on such a frail fabric as that they now occupied. It is true, that upon this they had left the burning vessel separate from the others; but immediately after they had rowed up alongside the larger structure, and made fast to it.

In this companionship they had continued for several days and nights, borne backward and forward by the varying breezes; resting by day on the calm surface of the ocean; and sharing the fate of the rest of the castaway crew.

What had led to their relinquishing the companionship? Why was Ben Brace and his protégé separated from the others and once more alone upon their little raft?

The cause of that separation must be declared, though one almost shudders to think of it. It was to save the boy from being eaten that Ben Brace had carried him away from his former associates; and it was only by a cunning stratagem, and at the risk of his own life, that the brave sailor had succeeded in preventing this horrid banquet from being made!

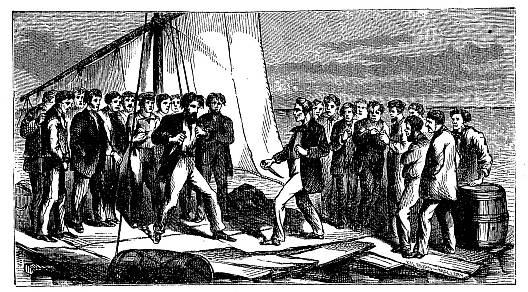

The castaway crew had exhausted the slender stock of provisions received from the wreck. They were reduced to that state of hunger which no longer revolts at the filthiest of food; and without even resorting to the customary method adopted in such terrible crises, they unanimously resolved upon the death of the boy,—Ben Brace alone raising a voice of dissent!

But this voice was not heeded. It was decided that the lad should die: and all that his protector was able to obtain from the fiendish crew, was the promise of a respite for him till the following morning.

Brace had his object in procuring this delay. During the night, the united rafts made way under a fresh breeze; and while all was wrapped in darkness, he cut the ropes which fastened the lesser one to the greater, allowing the former to fall astern. As it was occupied only by him and his protégé, they were thus separated from their dangerous associates; and when far enough off to run no risk of being heard, they used their oars to increase the distance.

All night long did they continue to row against the wind; and as morning broke upon them, they came to a rest upon the calm sea, unseen by their late comrades, and with ten miles separating the two rafts from each other.

It was the fatigue of that long spell of pulling—with many a watchful and weary hour preceding it—that had caused the boy to sink down upon the folded canvas, and almost on the instant fall asleep; and it was the apprehension of being followed that was causing Ben Brace to stand shading his eyes from the sun, and scan with uneasy glance the glittering surface of the sea.

Chapter Three.

The Lord’s Prayer.

After carefully scrutinising the smooth water towards every point of the compass,—but more especially towards the west,—the sailor ceased from his reconnoissance, and turned his eyes upon his youthful companion, still soundly slumbering.

“Poor lad!” muttered he to himself; “he be quite knocked up. No wonder, after such a week as we’ve had o’t. And to think he war so near bein’ killed and ate by them crew o’ ruffians. I’m blowed if that wasn’t enough to scare the strength out o’ him! Well, I dare say he’s escaped from that fate; but as soon as he has got a little more rest, we must take a fresh spell at the oars. It ’ud never do to drift back to them. If we do, it an’t only him they’ll want to eat, but me too, after what’s happened. Blowed if they wouldn’t.”

The sailor paused a moment, as if reflecting upon the probabilities of their being pursued.

“Sartin!” he continued, “they could never fetch that catamaran against the wind; but now that it’s turned dead calm, they might clap on wi’ their oars, in the hope of overtakin’ us. There’s so many of them to pull, and they’ve got oars in plenty, they might overhaul us yet.”

“O Ben! dear Ben! save me,—save me from the wicked men!”

This came from the lips of the lad, evidently muttered in his sleep.

“Dash my buttons, if he an’t dreaming!” said the sailor, turning his eyes upon the boy, and watching the movements of his lips. “He be talkin’ in his sleep. He thinks they’re comin’ at him just as they did last night on the raft! Maybe I ought to rouse him up. If he be a dreamin’ that way he’ll be better awake. It’s a pity, too, for he an’t had enough sleep.”

“Oh! they will kill me and eat me. Oh, oh!”

“No, they won’t do neyther,—blow’d if they do. Will’m, little Will’m! rouse yourself, my lad.”

And as he said this he bent down and gave the sleeper a shake.

“O Ben! is it you? Where are they,—those monsters?”

“Miles away, my boy. You be only a dreamin’ about ’em. That’s why I’ve shook you up.”

“I’m glad you have waked me. Oh! it was a frightful dream! I thought they had done it, Ben.”

“Done what, Will’m?”

“What they were going to do.”

“Dash it, no, lad! they an’t ate you yet; nor won’t, till they’ve first put an end o’ me,—that I promise ye.”

“Dear Ben,” cried the boy, “you are so good,—you’ve risked your life to save mine. Oh! how can I ever show you how much I am sensible of your goodness?”

“Don’t talk o’ that, little Will’m. Ah! lad, I fear it an’t much use to eyther o’ us. But if we must die, anything before a death like that. I’d rather far that the sharks should get us than to be eat up by one’s own sort.—Ugh! it be horrid to think o’t. But come, lad, don’t let us despair. For all so black as things look, let us put our trust in Providence. We don’t know but that His eye may be on us at this minute. I wish I knew how to pray, but I never was taught that ere. Can you pray, little Will’m?”

“I can repeat the Lord’s Prayer. Would that do, Ben?”

“Sartain it would. It be the best kind o’ prayer, I’ve heerd say. Get on your knees, lad, and do it. I’ll kneel myself, and join with ye in the spirit o’ the thing, tho’ I’m shamed to say I disremember most o’ the words.”

The boy, thus solicited, at once raised himself into a kneeling position, and commenced repeating the sublime prayer of the Christian. The rough sailor knelt alongside of him, and with hands crossed over his breast in a supplicating attitude, listened attentively, now and then joining in the words of the prayer, whenever some phrase recurred to his remembrance.

When it was over, and the “Amen” had been solemnly pronounced by the voices of both, the sailor seemed to have become inspired with a fresh hope; and, once more grasping an oar, he desired his companion to do the same.

“We must get a little farther to east’ard,” said he, “so as to make sure o’ bein’ out o’ their way. If we only pull a couple of hours afore the sun gets hot, I think we’ll be in no danger o’ meetin’ them any more. So let’s set to, little Will’m! Another spell, and then you can rest as long’s you have a mind to.”

The sailor seated himself close to the edge of the raft, and dropped his oar-blade in the water, using it after the fashion of a canoe-paddle. “Little Will’m,” taking his place on the opposite side, imitated the action; and the craft commenced moving onward over the calm surface of the sea.

The boy, though only sixteen, was skilled in the use of an oar, and could handle it in whatever fashion. He had learnt the art long before he had thought of going to sea; and it now stood him in good stead. Moreover, he was strong for his age, and therefore his stroke was sufficient to match that of the sailor, given more gently for the purpose.

Propelled by the two oars, the raft made way with considerable rapidity,—not as a boat would have done, but still at the rate of two or three knots to the hour.

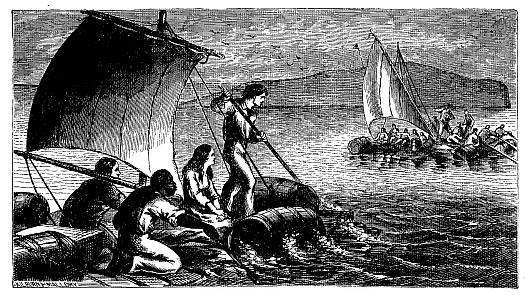

They had not been rowing long, however, when a gentle breeze sprung up from the west, which aided their progress in the direction in which they wished to go. One would have thought that this was just what they should have desired. On the contrary, the sailor appeared uneasy on perceiving that the breeze blew from the west. Had it been from any other point he would have cared little about it.

“I don’t like it a bit,” said he, speaking across the raft to his companion. “It helps us to get east’ard, that’s true; but it’ll help them as well—and with that broad spread o’ canvas they’ve rigged up, they might come down on us faster than we can row.”

“Could we not rig a sail too?” inquired the boy. “Don’t you think we might, Ben?”

“Just the thing I war thinkin’ o’, lad; I dare say we can. Let me see; we’ve got that old tarpaulin and the lying jib-sail under us. The tarpaulin itself will be big enough. How about ropes? Ah! there’s the sheets of the jib still stickin’ to the sail; and then there’s the handspike and our two oars. The oars ’ll do without the handspike. Let’s set ’em up then, and rig the tarpaulin between ’em.”

As the sailor spoke, he had risen to his feet; and after partially drawing the canvas off from the planks and spars, he soon accomplished the task of setting the two oars upright upon the raft. This done, the tarpaulin was spread between them, and when lashed so as to lie taut from one to the other, presented a surface of several square yards to the breeze,—quite as much sail as the craft was capable of carrying.

It only remained for them to look to the steering of the raft, so as to keep it head on before the wind; and this could be managed by means of the handspike, used as a rudder or steering-oar.

Laying hold of this, and placing himself abaft of the spread tarpaulin, Ben had the satisfaction of seeing that the sail acted admirably; and as soon as its influence was fairly felt, the raft surged on through the water at a rate of not less than five knots to the hour.

It was not likely that the large raft that carried the dreaded crew of would-be cannibals was going any faster; and therefore, whatever distance they might be off, there would be no great danger of their getting any nearer.

This confidence being firmly established, the sailor no longer gave a thought to the peril from which he and his youthful comrade had escaped. For all that, the prospect that lay before them was too terrible to permit their exchanging a word,—either of comfort or congratulation,—and for a long time they sat in a sort of desponding silence, which was broken only by the rippling surge of the waters as they swept in pearly froth along the sides of the raft.

Chapter Four.

Hunger.—Despair.

The breeze proved only what sailors call a catspaw, rising no higher than just to cause a ripple on the water, and lasting only about an hour. When it was over, the sea again fell into a dead calm; its surface assuming the smoothness of a mirror.

In the midst of this the raft lay motionless, and the extemporised sail was of no use for propelling it. It served a purpose, however, in screening off the rays of the sun, which, though not many degrees above the horizon, was beginning to make itself felt in all its tropical fervour.

Ben no longer required his companion to take a hand at the oar. Not but that their danger of being overtaken was as great as ever; for although they had made easterly some five or six knots, it was but natural to conclude that the great raft had been doing the same; and therefore the distance between the two would be about as before.

But whether it was that his energy had become prostrated by fatigue and the hopelessness of their situation, or whether upon further reflection he felt less fear of their being pursued, certain it is he no longer showed uneasiness about making way over the water; and after once more rising to his feet and making a fresh examination of the horizon, he stretched himself along the raft in the shade of the tarpaulin.

The boy, at his request, had already placed himself in a similar position, and was again buried in slumber.

“I’m glad to see he can sleep,” said Brace to himself, as he lay down alongside. “He must be sufferin’ from hunger as bad as I am myself, and as long as he’s asleep he won’t feel it. May be, if one could keep asleep they’d hold out longer, though I don’t know ’bout that bein’ so. I’ve often ate a hearty supper, and woke up in the mornin’ as hungry as if I’m gone to my bunk without a bite. Well, it an’t no use o’ me tryin’ to sleep as I feel now, blow’d if it is! My belly calls out loud enough to keep old Morphis himself from nappin’, and there an’t a morsel o’ anything. More than forty hours have passed since I ate that last quarter biscuit. I can think o’ nothing but our shoes, and they be so soaked wi’ the sea-water, I suppose they’ll do more harm than good. They’ll be sure to make the thirst a deal worse than it is, though the Lord knows it be bad enough a’ready. Merciful Father!—nothin’ to eat!—nothin’ to drink! O God, hear the prayer little Will’m ha’ just spoken and I ha’ repeated, though I’ve been too wicked to expect bein’ heard, ‘Give us this day our daily bread’! Ah! another day or two without it, an’ we shall both be asleep forever!”

The soliloquy of the despairing sailor ended in a groan, that awoke his young comrade from a slumber that was at best only transient and troubled.

“What is it, Ben?” he asked, raising himself on his elbow, and looking inquiringly in the face of his protector.

“Nothing partikler, my lad,” answered the sailor, who did not wish to terrify his companion with the dark thoughts which were troubling himself.

“I heard you groaning,—did I not? I was afraid you had seen them coming after us.”

“No fear o’ that,—not a bit. They’re a long way off, and in this calm sea they won’t be inclined to stir,—not as long as the rum-cask holds out, I warrant; and when that’s empty, they’ll not feel much like movin’ anywhere. ’Tan’t for them we need have any fear now.”

“O Ben! I’m so hungry; I could eat anything.”

“I know it, my poor lad; so could I.”

“True! indeed you must be even hungrier than I, for you gave me more than my share of the two biscuits. It was wrong of me to take it, for I’m sure you must be suffering dreadfully.”

“That’s true enough, Will’m; but a bit o’ biscuit wouldn’t a made no difference. It must come to the same thing in the end.”

“To what, Ben?” inquired the lad, observing the shadow that had overspread the countenance of his companion, which was gloomier than he had ever seen it.

The sailor remained silent. He could not think of a way to evade giving the correct answer to the question; and keeping his eyes averted, he made no reply.

“I know what you mean,” continued the interrogator. “Yes, yes,—you mean that we must die!”

“No, no, Will’m,—not that; there’s hope yet,—who knows what may turn up? It may be that the prayer will be answered. I’d like, lad, if you’d go over it again. I think I could help you better this time; for I once knew it myself,—long, long ago, when I was about as big as you, and hearin’ you repeatin’ it, it has come most o’ it back into my memory. Go over it again, little Will’m.”

The youth once more knelt upon the raft, and in the shadow of the spread tarpaulin repeated the Lord’s Prayer,—the sailor, in his rougher voice, pronouncing the words after him.

When they had finished, the latter once more rose to his feet, and for some minutes stood scanning the circle of sea around the raft.

The faint hope which that trusting reliance in his Maker had inspired within the breast of the rude mariner exhibited itself for a moment upon his countenance, but only for a moment. No object greeted his vision, save the blue, boundless sea, and the equally boundless sky.

A despairing look replaced that transient gleam of hope, and, staggering back behind the tarpaulin, he once more flung his body prostrate upon the raft.

Again they lay, side by side, in perfect silence,—neither of them asleep, but both in a sort of stupor, produced by their unspoken despair.

Chapter Five.

Faith.—Hope.

How long they lay in this half-unconscious condition, neither took note. It could not have been many minutes, for the mind under such circumstances does not long surrender itself to a state of tranquillity.

They were at length suddenly roused from it,—not, however, by any thought from within,—but by an object striking on their external senses, or, rather, upon the sense of sight. Both were lying upon their backs, with eyes open and upturned to the sky, upon which there was not a speck of cloud to vary the monotony of its endless azure.

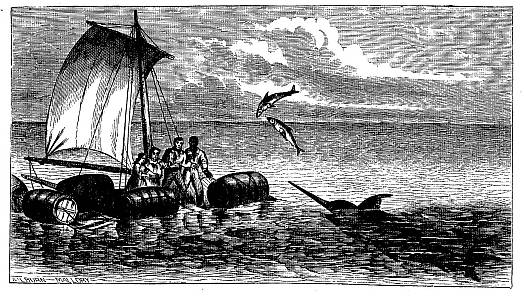

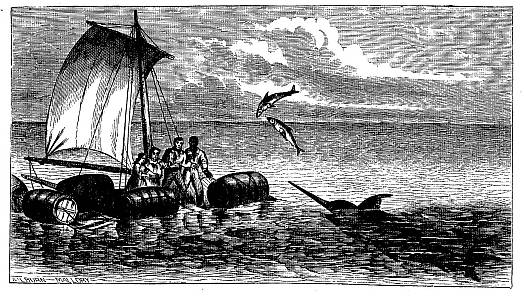

Its monotony, however, was at that moment varied by a number of objects that passed swiftly across their field of vision, shining and scintillating as if a flight of silver arrows had been shot over the raft. The hues of blue and white were conspicuous in the bright sunbeams, and those gay-coloured creatures, that appeared to belong to the air, but which in reality were denizens of the great deep, were at once recognised by the sailor.

“A shoal o’ flyin’-fish,” he simply remarked, and without removing from his recumbent position.

Then at once, as if some hope had sprung up within him at seeing them continue to fly over the raft, and so near as almost to touch the tarpaulin, he added, starting to his feet as he spoke—

“What if I might knock one o’ ’em down! Where’s the handspike?”

The last interrogatory was mechanical, and put merely to fill up the time; for as he gave utterance to it he reached towards the implement that lay within reach of his hands, and eagerly grasping raised it aloft.

With such a weapon it was probable that he might have succeeded in striking down one of the winged swimmers that, pursued by the bonitos and albacores, were still leaping over the raft. But there was a surer weapon behind him,—in the piece of canvas spread between the upright oars; and just as the sailor had got ready to wield his huge club, a shining object flashed close to his eyes, whilst his ears were greeted by a glad sound, signifying that one of the vaulting fish had struck against the tarpaulin.

Of course it had dropped down upon the raft: for there it was, flopping and bounding about among the folds of the flying-jib, far more taken by surprise than Ben Brace, who had witnessed its mishap, or even little William, upon whose face it had fallen, with all the weight of its watery carcass. If a bird in the hand be worth two in the bush, by the same rule a fish in the hand should be worth two in the water, and more than that number flying in the air.

Some such calculation as this might have passed through the brain of Ben Brace; for, instead of continuing to hold his handspike high flourished over his head, in the hope of striking another fish, he suffered the implement to drop down upon the raft; and stooping down, he reached forward to secure the one that had voluntarily, or, rather, should we say, involuntarily, offered itself as a victim.

As it kept leaping about over the raft, there was just the danger that it might reach the edge of that limited area, and once more escape to its natural element.

This, however naturally desired by the fish, was the object which the occupants of the raft most desired to prevent; and to that end both had got upon their knees, and were scrambling over the sail-cloth with as much eager earnestness as a couple of terriers engaged in a scuffle with a harvest rat.

Once or twice little William had succeeded in getting the fish in his fingers; but the slippery creature, armed also with its spinous fin-wings, had managed each time to glide out of his grasp; and it was still uncertain whether a capture might be made, or whether after all they were only to be tantalised by the touch and sight of a morsel of food that was never to pass over their palates.

The thought of such a disappointment stimulated Ben Brace to put forth all his energies, coupled with his greatest activity. He had even resolved upon following the fish into the sea if it should prove necessary,—knowing that for the first few moments after regaining its natural element it would be more easy of capture. But just then an opportunity was offered that promised the securing of the prey without the necessity of wetting a stitch of his clothes.

The fish had been all the while bounding about upon the spread sail-cloth, near the edge of which it had now arrived. But it was fated to go no farther, at least of its own accord; for Ben seeing his advantage, seized hold of the loose selvage of the sail, and raising it a little from the raft, doubled it over the struggling captive. A stiff squeeze brought its struggles to a termination; and when the canvas was lifted aloft, it was seen lying underneath, slightly flattened out beyond its natural dimensions, and it is scarcely necessary to say, as dead as a herring.

Whether right or no, the simple-minded seaman recognised in this seasonable supply of provision the hand of an overruling Providence; and without further question, attributed it to the potency of that prayer twice repeated.

“Yes, Will’m, you see it, my lad, ’tis the answer to that wonderful prayer. Let’s go over it once more, by way o’ givin’ thanks. He who has sent meat can also gie us drink, even here, in the middle o’ the briny ocean. Come, boy! as the parson used to say in church,—let us pray!”

And with this serio-comic admonition—meant, however, in all due solemnity—the sailor dropped upon his knees, and, as before, echoed the prayer once more pronounced by his youthful companion.

Chapter Six.

Flying-Fish.

The flying-fish takes rank as one of the most conspicuous “wonders of the sea,” and in a tale essentially devoted to the great deep, it is a subject deserving of more than a passing notice.

From the earliest periods of ocean travel, men have looked with astonishment upon a phenomenon not only singular at first sight, but which still remains unexplained, namely, a fish and a creature believed to be formed only for dwelling under water, springing suddenly above the surface, to the height of a two-storey house, and passing through the air to the distance of a furlong, before falling back into its own proper element!

It is no wonder that the sight should cause surprise to the most indifferent observer, nor that it should have been long a theme of speculation with the curious, and an interesting subject of investigation to the naturalist.

As flying-fish but rarely make their appearance except in warm latitudes, few people who have not voyaged to the tropics have had an opportunity of seeing them in their flight. Very naturally, therefore, it will be asked what kind of fish, that is, to what species and what genus the flying-fish belong. Were there only one kind of these curious creatures the answer would be easier. But not only are there different species, but also different “genera” of fish endowed with the faculty of flying, and which from the earliest times and in different parts of the world have equally received this characteristic appellation. A word or two about each sort must suffice.

First, then, there are two species belonging to the genus Trigla, or the Gurnards, to which Monsieur La Cepède has given the name of Dactylopterus.

One species is found in the Mediterranean, and individuals, from a foot to fifteen inches in length, are often taken by the fishermen, and brought to the markets of Malta, Sicily, and even to the city of Rome. The other species of flying gurnard occur in the Indian Ocean and the seas around China and Japan.

The true flying-fish, however, that is to say, those that are met with in the great ocean, and most spoken of in books, and in the “yarns” of the sailor, are altogether of a different kind from the gurnards. They are not only different in genus, but in the family and even the order of fishes. They are of the genus Exocetus, and in form and other respects have a considerable resemblance to the common pike. There are several species of them inhabiting different parts of the tropical seas; and sometimes individuals, in the summer, have been seen as far north as the coast of Cornwall in Europe, and on the banks of Newfoundland in America. Their natural habitat, however, is in the warm latitudes of the ocean; and only there are they met with in large “schools,” and seen with any frequency taking their aerial flight.

For a long time there was supposed to be only one, or at most two, species of the Exocetus; but it is now certain there are several—perhaps as many as half a dozen—distinct from each other. They are all much alike in their habits,—differing only in size, colour, and such like circumstances.

Naturalists disagree as to the character of their flight. Some assert that it is only a leap, and this is the prevailing opinion. Their reason for regarding it thus is, that while the fish is in the air there cannot be observed any movement of the wings (pectoral fins); and, moreover, after reaching the height to which it attains on its first spring, it cannot afterwards rise higher, but gradually sinks lower till it drops suddenly back into the water.

This reasoning is neither clear nor conclusive. A similar power of suspending themselves in the air, without motion of the wings is well-known to belong to many birds,—as the vulture, the albatross, the petrels, and others. Besides, it is difficult to conceive of a leap twenty feet high and two hundred yards long; for the flight of the Exocetus has been observed to be carried to this extent, and even farther. It is probable that the movement partakes both of the nature of leaping and flying: that it is first begun by a spring up out of the water,—a power possessed by most other kinds of fish,—and that the impulse thus obtained is continued by the spread fins acting on the air after the fashion of parachutes. It is known that the fish can greatly lighten the specific gravity of its body by the inflation of its “swim-bladder,” which, when perfectly extended, occupies nearly the entire cavity of its abdomen. In addition to this, there is a membrane in the mouth which can be inflated through the gills. These two reservoirs are capable of containing a considerable volume of air; and as the fish has the power of filling or emptying them at will, they no doubt play an important part in the mechanism of its aerial movement.

One thing is certain, that the flying-fish can turn while in the air,—that is, diverge slightly from the direction first taken; and this would seem to argue a capacity something more than that of a mere spring or leap. Besides, the wings make a perceptible noise,—a sort of rustling,—often distinctly heard; and they have been seen to open and close while the creature is in the air.

A shoal of flying-fish might easily be mistaken for a flock of white birds, though their rapid movements, and the glistening sheen of their scales—especially when the sun is shining—usually disclose their true character. They are at all times a favourite spectacle, and with all observers,—the old “salt” who has seen them a thousand times, and the young sailor on his maiden voyage, who beholds them for the first time in his life. Many an hour of ennui occurring to the ship-traveller, as he sits upon the poop, restlessly scanning the monotonous surface of the sea, has been brought to a cheerful termination by the appearance of a shoal of flying-fish suddenly sparkling up out of the bosom of the deep.

The flying-fish appear to be the most persecuted of all creatures. It is to avoid their enemies under water that they take fin and mount into the air; but the old proverb, “out of the frying-pan into the fire,” is but too applicable in their case, for in their endeavours to escape from the jaws of dolphins, albicores, bonitos, and other petty tyrants of the sea, they rush into the beaks of gannets, boobies, albatrosses, and other petty tyrants of the sky.

Much sympathy has been felt—or at all events expressed—for these pretty and apparently innocent little victims. But, alas! our sympathy receives a sad shock, when it becomes known that the flying-fish is himself one of the petty tyrants of the ocean,—being, like his near congener, the pike, a most ruthless little destroyer and devourer of any fish small enough to go down his gullet.

Besides the two genera of flying-fish above described, there are certain other marine animals which are gifted with a similar power of sustaining themselves for some seconds in the air. They are often seen in the Pacific and Indian oceans, rising out of the water in shoals, just like the Exoceti: and, like them, endeavouring to escape from the albicores and bonitos that incessantly pursue them. These creatures are not fish in the true sense of the word, but “molluscs,” of the genus Loligo; and the name given to them by the whalers of the Pacific is that of “Flying Squid.”

Chapter Seven.

A Cheering Cloud.

The particular species of flying-fish that had fallen into the clutches of the two starving castaways upon the raft was the Exocetus evolans, or “Spanish flying-fish” of mariners,—a well-known inhabitant of the warmer latitudes of the Atlantic. Its body was of a steel-blue, olive and silvery white underneath, with its large pectoral fins (its wings) of a powdered grey colour. It was one of the largest of its kind, being rather over twelve inches in length, and nearly a pound in weight.

Of course, it afforded but a very slight meal for two hungry stomachs,—such as were those of Ben Brace and his boy companion. Still it helped to strengthen them a little; and its opportune arrival upon the raft—which they could not help regarding as providential—had the further effect of rendering them for a time more cheerful and hopeful.

It is not necessary to say that they ate the creature without cooking it; and although under ordinary circumstances this might be regarded as a hardship, neither was at that moment in the mood to be squeamish. They thought the dish dainty enough. It was its quantity—not the quality—that failed to give satisfaction.

Indeed the flying-fish is (when cooked, of course) one of the most delicious of morsels,—a good deal resembling the common herring when caught freshly, and dressed in a proper manner.

It seemed, however, as if the partial relief from hunger only aggravated the kindred appetite from which the occupants of the raft had already begun to suffer. Perhaps the salt-water, mingled with the saline juices of the fish, aided in producing this effect. In any case, it was not long after they had eaten the Exocetus before both felt thirst in its very keenest agony.

Extreme thirst, under any circumstances, is painful to endure; but under no conditions is it so excruciating as in the midst of the ocean. The sight of water which you may not drink,—the very proximity of that element,—so near that you may touch it, and yet as useless to the assuaging of thirst as if it was the parched dust of the desert,—increases rather than alleviates the appetite. It is to no purpose, that you dip your fingers into the briny flood, and endeavour to cool your lips and tongue by taking it into the mouth. To swallow it is still worse. You might as well think to allay thirst by drinking liquid fire. The momentary moistening of the mouth and tongue is succeeded by an almost instantaneous parching of the salivary glands, which only glow with redoubled ardour.

Ben Brace knew this well enough; and once or twice that little William lifted the sea-water on his palm and applied it to his lips, the sailor cautioned him to desist, saying that it would do him more harm than good.

In one of his pockets Ben chanced to have a leaden bullet, which he gave the boy, telling him to keep it in his mouth and occasionally to chew it. By this means the secretion of the saliva was promoted; and although it was but slight, the sufferer obtained a little relief.

Ben himself held the axe to his lips, and partly by pressing his tongue against the iron, and partly by gnawing the angle of the blade, endeavoured to produce the same effect.

It was but a poor means of assuaging that fearful thirst that was now the sole object of their thoughts,—it might be said their only sensation,—for all other feelings, both of pleasure or pain, had become overpowered by this one. On food they no longer reflected, though still hungry; but the appetite of hunger, even when keenest, is far less painful than that of thirst. The former weakens the frame, so that the nervous system becomes dulled, and less sensible of the affliction it is enduring; whereas the latter may exist to its extremest degree, while the body is in full strength and vigour, and therefore more capable of feeling pain.

They suffered for several hours, almost all the time in silence. The words of cheer which the sailor had addressed to his youthful comrade were now only heard occasionally, and at long intervals, and when heard were spoken in a tone that proclaimed their utterance to be merely mechanical, and that he who gave tongue to them had but slight hope. Little as remained, however, he would rise from time to time to his feet, and stand for a while scanning the horizon around him. Then as his scrutiny once more terminated in disappointment, he would sink back upon the canvas, and half-kneeling, half-lying, give way for an interval to a half stupor of despair.

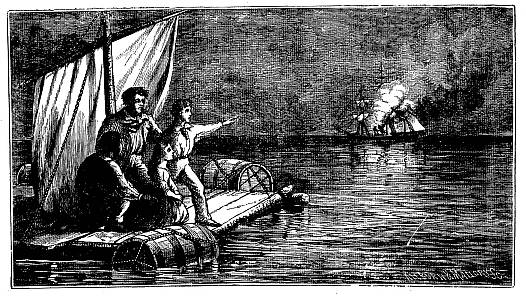

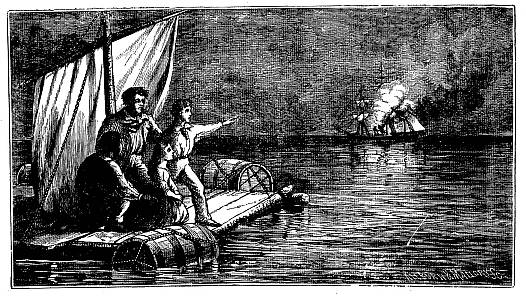

From one of these moods he was suddenly aroused by circumstances which had made no impression on his youthful companion, though the latter had also observed it. It was simply the darkening of the sun by a cloud passing over its disc.

Little William wondered that an incident of so common character should produce so marked an effect as it had done upon his protector: for the latter on perceiving that the sun had become shadowed instantly started to his feet, and stood gazing up towards the sky. A change had come over his countenance. His eyes, instead of the sombre look of despair observable but the moment before, seemed now to sparkle with hope. In fact, the cloud which had darkened the face of the sun appeared to have produced the very opposite effect upon the face of the sailor!

Chapter Eight.

A Canvas Tank.

“What is it, Ben?” asked William, in a voice husky and hoarse, from the parched throat through which it had to pass. “You look pleased like; do you see anything?”

“I see that, boy,” replied the sailor, pointing up into the sky.

“What? I see nothing there except that great cloud that has just passed over the sun. What is there in that?”

“Ay, what is there in’t? That’s just what I’m tryin’ to make out, Will’m; an’ if I’m not mistaken, boy, there’s it ’t the very thing as we both wants.”

“Water!” gasped William, his eyes lighting up with gleam of hope. “A rain-cloud you think, Ben?”

“I’m a’most sure o’t, Will’m. I never seed a bank o’ clouds like them there wasn’t some wet in; and if the wind ’ll only drift ’em this way, we may get a shower ’ll be the savin’ o’ our lives. O Lord! in thy mercy look down on us, and send ’em over us!”

The boy echoed the prayer.

“See!” cried the sailor. “The wind is a fetchin’ them this way. Yonder’s more o’ the same sort risin’ up in the west, an’ that’s the direction from which it’s a-blowin’. Ho! As I live, Will’m, there’s rain. I can see by the mist it’s a-fallin’ on the water yonder. It’s still far away,—twenty mile or so,—but that’s nothing; an’ if the wind holds good in the same quarter, it must come this way.”

“But if it did, Ben,” said William, doubtingly, “what good would it do us? We could not drink much of the rain as it falls, and you know we have nothing in which to catch a drop of it.”

“But we have, boy,—we have our clothes and our shirts. If the rain comes, it will fall like it always does in these parts, as if it were spillin’ out o’ a strainer. We’ll be soakin’ wet in five minutes’ time; and then we can wring all out,—trousers, shirts, and every rag we’ve got.”

“But we have no vessel, Ben,—what could we wring the water into?”

“Into our months first: after that—ah! it be a pity. I never thought o’t. We won’t be able to save a drop for another time. Any rate, if we could only get one good quenchin’, we might stand it several days longer. I fancy we might catch some fish, if we were only sure about the water. Yes, the rain’s a-comin’ on. Look at yon black clouds; and see, there’s lightning forkin’ among ’em. That ’s a sure sign it’s raining. Let’s strip, and spread out our shirts so as to have them ready.”

As Ben uttered this admonition he was about proceeding to pull off his pea-jacket, when an object came before his eyes causing him to desist. At the same instant an exclamatory phrase escaping from his lips explained to his companion why he had thus suddenly changed his intention. The phrase consisted of two simple words, which written as pronounced by Ben were, “Thee tarpolin.”

Little William knew it was “the tarpauling” that was meant. He could not be mistaken about that; for, even had he been ignorant of the sailor’s pronunciation of the words, the latter at that moment stood pointing to the piece of tarred canvas spread upright between the oars; and which had formerly served as a covering for the after-hatch of the Pandora. William did not equally understand why his companion was pointing to it.

He was not left long in ignorance.

“Nothing to catch the water in? That’s what you sayed, little Will’m? What do ye call that, my boy?”

“Oh!” replied the lad, catching at the idea of the sailor. “You mean—”

“I mean, boy, that there’s a vessel big enough to hold gallons,—a dozen o’ ’em.”

“You think it would hold water?”

“I’m sure o’t, lad. For what else be it made waterproof? I helped tar it myself not a week ago. It’ll hold like a rum-cask, I warrant,—ay, an’ it’ll be the very thing to catch it too. We can keep it spread out a bit wi’ a hollow place in the middle, an’ if it do rain, there then,—my boy, we’ll ha’ a pool big enough to swim ye in. Hurrah! it’s sure to rain. See yonder. It be comin’ nearer every minute. Let’s be ready for it. Down wi’ the mainsail. Let go the sheets,—an’ instead o’ spreadin’ our canvas to the wind, as the song says, we’ll stretch it out to the rain. Come, Will’m, let’s look alive!”

William had by this time also risen to his feet; and both now busied themselves in unlashing the cords that had kept the hatch-covering spread between the two oars.

This occupied only a few seconds of time; and the tarpauling soon lay detached between the extemporised masts, that were still permitted to remain as they had been “stepped.”

At first the sailor had thought of holding the piece of tarred canvas in their hands; but having plenty of time to reflect, a better plan suggested itself. So long as it should be thus held, they would have no chance of using their hands for any other purpose; and would be in a dilemma as to how they should dispose of the water after having “captured it.”

It did not require much ingenuity to alter their programme for the better. By means of the flying-jib that lay along the raft, they were enabled to construct a ridge of an irregular circular shape; and then placing the tarpauling upon the top, and spreading it out so that its edges lapped over this ridge, they formed a deep concavity or “tank” in the middle, which was capable of holding many gallons of water.

It only remained to examine the canvas, and make sure there were no rents or holes by which the water might escape. This was done with all the minuteness and care that the circumstances called for; and when the sailor at length became satisfied that the tarpauling was waterproof, he took the hand of his youthful protégé in his own, and both kneeling upon the raft, with their faces turned towards the west watched the approach of those dark, lowering clouds, as if they had been bright-winged angels sent from the far sky to deliver them from destruction.

Chapter Nine.

A Pleasant Shower-Bath.

They had not much longer to wait. The storm came striding across the ocean; and, to the intense gratification of both man and boy, the rain was soon falling upon them, as if a water-spout had burst over their heads.

A single minute sufficed to collect over a quart within the hollow of the spread tarpauling; and before that minute had transpired, both might have been seen lying prostrate upon their faces with their heads together, near the centre of the concavity, and their lips close to the canvas, sucking up the delicious drops, almost as fast as they fell.

For a long time they continued in this position, indulging in that cool beverage sent them from the sky,—which to both appeared the sweetest they had ever tasted in their lives. So engrossed were they in its enjoyment, that neither spoke a word until several minutes had elapsed, and both had drunk to a surfeit.

They were by this time wet to the skin; for the tropic rain, falling in a deluge of thick heavy drops, soon saturated their garments through and through. But this, instead of being an inconvenience, was rather agreeable than otherwise, cooling their skins so long parched by the torrid rays of the sun.

“Little Will’m,” said Ben, after swallowing about a gallon of the rain-water, “didn’t I say that He ’as sent us meat, in such good time too, could also gi’ us som’at to drink? Look there! water enow to last us for days, lad!”

“’Tis wonderful!” exclaimed the boy. “I am sure, Ben, that Providence has done this. Indeed, it must be true what I was often told in the Sunday school,—that God is everywhere. Here He is present with us in the midst of this great ocean. O, dear Ben, let’s hope He will not forsake us now. I almost feel sure, after what has happened to us, that the hand of God will yet deliver us from our danger.”

“I almost feel so myself,” rejoined the sailor, his countenance resuming its wonted expression of cheerfulness. “After what’s happened, one could not think otherwise; but let us remember, lad, that He is up aloft, an’ has done so much for us, expecting us to do what we can for ourselves. He puts the work within our reach, an’ then leaves us to do it. Now here’s this fine supply o’ water. If we was to let that go to loss, it would be our own fault, not his, an’ we’d deserve to die o’ thirst for it.”

“What is to be done, Ben? How are we to keep it?”

“That’s just what I’m thinkin’ about. In a very short while the rain will be over. I know the sort o’ it. It be only one o’ these heavy showers as falls near the line, and won’t last more than half an hour,—if that. Then the sun ’ll be out as hot as ever, an’ will lick up the water most as fast as it fell,—that is, if we let it lie there. Yes, in another half o’ an hour that tarpolin would be as dry as the down upon a booby’s back.”

“O dear! what shall we do to prevent evaporating?”

“Jest give me a minute to consider,” rejoined the sailor, scratching his head, and putting on an air of profound reflection; “maybe afore the rain quits comin’ down, I’ll think o’ some way to keep it from evaporating; that’s what you call the dryin’ o’ it up.”

Ben remained for some minutes silent, in the thoughtful attitude he had assumed,—while William, who was equally interested in the result of his cogitations, watched his countenance with an eager anxiety.

Soon a joyful expression revealed itself to the glance of the boy, telling him that his companion had hit upon some promising scheme.

“I think I ha’ got it, Will’m,” said he; “I think I’ve found a way to stow the water even without a cask.”

“You have!” joyfully exclaimed William. “How, Ben?”

“Well, you see, boy, the tarpolin holds water as tight as if ’twere a glass bottle. I tarred it myself,—that did I, an’ as I never did my work lubber-like, I done that job well. Lucky I did, warn’t it, William?”

“It was.”

“That be a lesson for you, lad. Schemin’ work bean’t the thing, you see. It comes back to cuss one; while work as be well did be often like a blessin’ arterward,—just as this tarpolin be now. But see! as I told you, the rain would soon be over. There be the sun again, hot an’ fiery as ever. There ain’t no time to waste. Take a big drink, afore I put the stopper into the bottle.”

William, without exactly comprehending what his companion meant by the last words, obeyed the injunction; and stretching forward over the rim of the improvised tank, once more placed his lips to the water, and drank copiously. Ben did the same for himself, passing several pints of the fluid into his capacious stomach.

Then rising to his feet with a satisfied air, and directing his protégé to do the same, he set about the stowage of the water.

William was first instructed as to the intended plan, so that he might be able to render prompt and efficient aid; for it would require both of them, and with all their hands, to carry it out.

The sailor’s scheme was sufficiently ingenious. It consisted in taking up first the corners of the tarpauling, then the edges all around, and bringing them together in the centre. This had to be done with great care, so as not to jumble the volatile fluid contained within the canvas, and spill it over the selvage. Some did escape, but only a very little; and they at length succeeded in getting the tarpauling formed into a sort of bag, puckered around the mouth.

While Ben with both arms held the gathers firm and fast, William passed a loop of strong cord, that had already been made into a noose for the purpose, around the neck of the bag, close under Ben’s wrists, and then drawing the other end round one of the upright oars, he pulled upon the cord with all his might.

It soon tightened sufficiently to give Ben the free use of his hands; when with a fresh loop taken around the crumpled canvas, and after a turn or two to render it more secure, the cord was made fast.

The tarpauling now rested upon the raft, a distended mass, like the stomach of some huge animal coated with tar. It was necessary, however, lest the water should leak out through the creases, to keep the top where it was tied, uppermost; and this was effected by taking a turn or two of the rope round the uppermost end of one of the oars, that had served for masts, and there making a knot. By this means the great water-sack was held in such a position that, although the contents might “bilge” about at their pleasure, not a drop could escape out either at the neck or elsewhere.

Altogether they had secured a quantity of water, not less than a dozen gallons, which Ben had succeeded in stowing to his satisfaction.

Chapter Ten.

The Pilot-Fish.

This opportune deliverance from the most fearful of deaths had inspired the sailor with a hope that they might still, by some further interference of Providence, escape from their perilous position. Relying on this hope, he resolved to leave no means untried that might promise to lead to its realisation. They were now furnished with a stock of water which, if carefully hoarded, would last them for weeks. If they could only obtain a proportionate supply of food, there would still be a chance of their sustaining life until some ship might make its appearance,—for, of course, they thought not of any other means of deliverance.

To think of food was to think of fishing for it. In the vast reservoir of the ocean under and around them there was no lack of nourishing food, if they could only grasp it; but the sailor well knew that the shy, slippery denizens of the deep are not to be captured at will, and that, with all the poor schemes they might be enabled to contrive, their efforts to capture even a single fish might be exerted in vain.

Still they could try; and with that feeling of hopeful confidence which usually precedes such trials, they set about making preparations.

The first thing was to make hooks and lines. There chanced to be some pins in their clothing; and with these Ben soon constructed a tolerable set of hooks. A line was obtained by untwisting a piece of rope, and respinning it to the proper thickness; and then a float was found by cutting a piece of wood to the proper dimensions. And for a sinker there was the leaden bullet with which little William had of late so vainly endeavoured to allay the pangs of thirst. The bones and fins of the flying-fish—the only part of it not eaten—would serve for bait. They did not promise to make a very attractive one; for there was not a morsel of flesh left upon them; but Ben knew that there are many kinds of fish inhabiting the great ocean that will seize at any sort of bait,—even a piece of rag,—without considering whether it be good for them or not.

They had seen fish several times near the raft, during that very day; but suffering as they were from thirst more than hunger, and despairing of relief to the more painful appetite, they had made no attempt to capture them. Now, however, they were determined to set about it in earnest.

The rain had ceased falling; the breeze no longer disturbed the surface of the sea. The clouds had passed over the canopy of the heavens,—the sky was clear, and the sun bright and hot as before.

Ben standing erect upon the raft, with the baited hook in his hand, looked down into the deep blue water.

Even the smallest fish could have been seen many fathoms below the surface, and far over the ocean.

William on the other side of the raft was armed with hook and line, and equally on the alert.

For a long time their vigil was unrewarded. No living thing came within view. Nothing was under their eyes save the boundless field of ultramarine,—beautiful, but to them, at that moment, marked only by a miserable monotony.

They had stood thus for a full hour, when an exclamation escaping from the lad, caused his companion to turn and look to the other side of the raft.

A fish was in sight. It was that which had drawn the exclamation from the boy, who was now swinging his line in the act of casting it out.

The ejaculation had been one of joy. It was checked on his perceiving that the sailor did not share it. On the contrary, a cloud came over the countenance of the latter on perceiving the fish,—whose species he at once recognised.

And why? for it was one of the most beautiful of the finny tribe. A little creature of perfect form,—of a bright azure blue, with transverse bands of deeper tint, forming rings around its body. Why did Ben Brace show disappointment at its appearance?

“You needn’t trouble to throw out your line, little Will’m,” said he, “that ere takes no bait,—not it.”

“Why?” asked the boy.

“Because it’s something else to do than forage for itself. I dare say its master an’t far off.”

“What is it?”

“That be the pilot-fish. See! turns away from us. It gone back to him as has sent it.”

“Sent it! Who, Ben?”

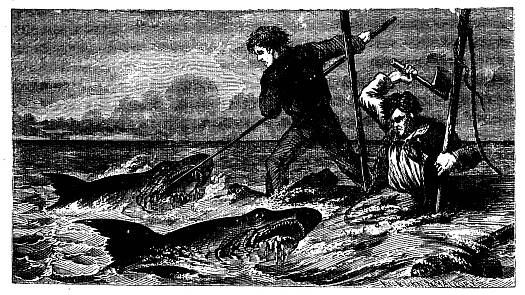

“A shark, for sarten. Didn’t I tell ye? Look yonder. Two o’ them, as I live; and the biggest kind they be. Slash my timbers if I iver see such a pair! They have fins like lug-sails. Look! the pilot’s gone to guide ’em. Hang me if they bean’t a-comin’ this way!”

William had looked in the direction pointed out by his companion. He saw the two great dorsal fins standing several feet above the water. He knew them to be those of the white shark: for he had already seen these dreaded monsters of the deep on more than one occasion.

It was true, as Ben had hurriedly declared. The little pilot-fish, after coming within twenty fathoms of the raft, had turned suddenly in the water, and gone back to the sharks; and now it was seen swimming a few feet in advance of them, as if in the act of leading them on!

The boy was struck with something in the tone of his companion’s voice, that led him to believe there was danger in the proximity of these ugly creatures; and to say the truth, Ben did not behold them without a certain feeling of alarm. On the deck of a ship they might have been regarded without any fear; but upon a frail structure like that which supported the castaways—their feet almost on a level with the surface of the water—it was not so very improbable that the sharks might attack them!

In his experience the sailor had known cases of a similar kind. It was no matter of surprise, that he should feel uneasiness at their approach, if not actual fear.

But there was no time left either for him to speculate as to the probabilities of such an attack, or for his companion to question him about them.

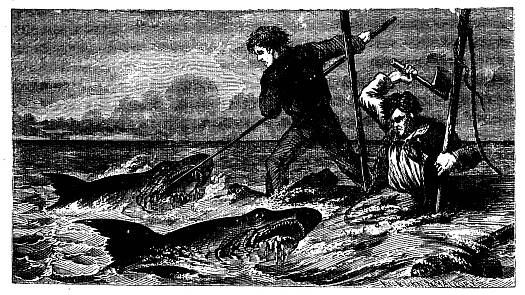

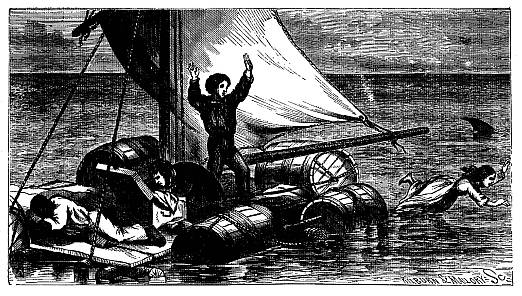

Scarcely had the last words parted from his lips, when the foremost of the two sharks was seen to lash the water with  its broad forked tail,—and then coming on with a rush, it struck the raft with such a force as almost to capsize it.

its broad forked tail,—and then coming on with a rush, it struck the raft with such a force as almost to capsize it.

The other shark shot forward in a similar manner; but glancing a little to one side, caught in its huge mouth the end of the dolphin-striker, grinding off a large piece of the spar as if it had been cork-wood!

This it swallowed almost instantaneously; and then turning once more in the water appeared intent upon renewing the attack.

Ben and the boy had dropped their hooks and lines,—the former instinctively arming himself with the axe, while the latter seized upon the spare handspike. Both stood ready to receive the second charge of the enemy.

It was made almost on the instant. The shark that had just attacked was the first to return; and coming on with the velocity of an arrow, it sprang clear above the surface, projecting its hideous jaws over the edge of the raft.

For a moment the frail structure was in danger of being either capsized or swamped altogether, and then the fate of its occupants would undoubtedly have been to become “food for sharks.”

But it was not the intention of Ben Brace or his youthful comrade to yield up their lives without striking a blow in self-defence, and that given by the sailor at once disembarrassed him of his antagonist.

Throwing one arm around a mast, in order to steady himself, and raising the light axe in the other, he struck outward and downward with all his might. The blade of the axe, guided with an unswerving arm, fell right upon the snout of the shark, just midway between its nostrils, cleaving the cartilaginous flesh to the depth of several inches, and laying it open to the bones.

There could not have been chosen a more vital part upon which to inflict a wound; for, huge as is the white shark, and strong and vigorous as are all animals of this ferocious family, a single blow upon the nose with a handspike or even a billet of wood, if laid on with a heavy hand, will suffice to put an end to their predatory courses.

And so was it with the shark struck by the axe of Ben Brace. As soon as the blow had been administered, the creature rolled over on its back; and after a fluke or two with its great forked tail, and a tremulous shivering through its body, it lay floating upon the water motionless as a log of wood.

William was not so fortunate with his antagonist, though he had succeeded in keeping it off. Striking wildly out with the handspike in a horizontal direction, he had poked the butt end of the implement right between the jaws of the monster, just as it raised its head over the raft with the mouth wide open.

The shark, seizing the handspike in its treble row of teeth, with one shake of its head whipped it out of the boy’s hands: and then rushing on through the water, was seen grinding the timber into small fragments, and swallowing it as if it had been so many crumbs of bread or pieces of meat.

In a few seconds not a bit of the handspike could be seen,—save some trifling fragments of the fibrous wood that floated on the surface of the water; but what gave greater gratification to those who saw them, was the fact that the shark which had thus made “mince-meat” of the piece of timber was itself no longer to be seen.

Whether because it had satisfied the cravings of its appetite by that wooden banquet, or whether it had taken the alarm at witnessing the fate of its companion,—by much the larger of the two,—was a question of slight importance either to Ben Brace or to William. For whatever reason, and under any circumstances, they were but too well pleased to be disembarrassed of its hideous presence; and as they came to the conclusion that it had gone off for good, and saw the other one lying with its white belly turned upwards upon the surface of the water—evidently dead as a herring—they could no longer restrain their voices, but simultaneously raised them in a shout of victory.

Chapter Eleven.

A Lenten Dinner.

The shark struck upon the snout, though killed by the blow, continued to float near the surface of the water its fins still in motion as if in the act of swimming.

One unacquainted with the habits of these sea-monsters might have supposed that it still lived, and might yet contrive to escape. Not so the sailor, Ben Brace. Many score of its kind had Ben coaxed to take a bait, and afterwards helped to haul over the gangway of a ship and cut to pieces upon the deck; and Ben knew as much about the habits of these voracious creatures as any sailor that ever crossed the wide ocean, and much more than any naturalist that never did. He had seen a shark drawn aboard with a great steel hook in its stomach,—he had seen its belly ripped up with a jack-knife, the whole of the intestines taken out, then once more thrown into the sea; and after all this rough handling he had seen the animal not only move its fins, but actually swim off some distance from the ship! He knew, moreover, that a shark may be cut in twain,—have the head separated from the body,—and still exhibit signs of vitality in both parts for many hours after the dismemberment! Talk of the killing of a cat or an eel!—a shark will stand as much killing as twenty cats or a bushel of eels, and still exhibit symptoms of life.

The shark’s most vulnerable part appears to be the snout,—just where the sailor had chosen to make his hit; and a blow delivered there with an axe, or even a handspike, usually puts a termination to the career of this rapacious tyrant of the great deep.

“I’ve knocked him into the middle o’ next week,” cried Ben, exultingly, as he saw the shark heel over on its side. “It ain’t goin’ to trouble us any more. Where’s the other un?”

“Gone out that way,” answered the boy, pointing in the direction taken by the second and smaller of the two sharks. “He whipped the handspike out of my hands, and he’s craunched it to fragments. See! there are some of the pieces floating on the water!”

“Lucky you let go, lad; else he might ha’ pulled you from the raft. I don’t think he’ll come back again after the reception we’ve gi’ed ’em. As for the other, it’s gone out o’ its senses. Dash my buttons, if’t ain’t goin’ to sink! Ha! I must hinder that. Quick, Will’m, shy me that piece o’ sennit: we must secure him ’fore he gives clean up and goes to the bottom. Talk o’ catching fish wi’ hook an’ line! Aha! This beats all your small fry. If we can secure it, we’ll have fish enough to last us through the longest Lent. There now! keep on the other edge of the craft so as to balance me. So-so!”

While the sailor was giving these directions, he was busy with both hands in forming a running-noose on one end of the sennit-cord, which William on the instant had handed over to him. It was but the work of a moment to make the noose; another to let it down into the water; a third to pass it over the upper jaw of the shark; a fourth to draw it taut, and tighten the cord around the creature’s teeth. The next thing done was to secure the other end of the sennit to the upright oar; and the carcass of the shark was thus kept afloat near the surface of the water.

To guard against a possible chance of the creature’s recovery, Ben once more laid hold of the axe; and, leaning over the edge of the raft, administered a series of smart blows upon its snout. He continued hacking away, until the upper jaw of the fish exhibited the appearance of a butcher’s chopping-block; and there was no longer any doubt of the creature being as “dead as a herring.”

“Now, Will’m,” said the shark-killer, “this time we’ve got a fish that’ll gi’e us a fill, lad. Have a little patience, and I’ll cut ye a steak from the tenderest part o’ his body; and that’s just forrard o’ the tail. You take hold o’ the sinnet, an’ pull him up a bit,—so as I can get at him.”

The boy did as directed; and Ben, once more bending over the edge of the raft, caught hold of one of the caudal fins, and with his knife detached a large flake from the flank of the fish,—enough to make an ample meal for both of them.

It is superfluous to say that, like the little flying-fish, the shark-meat had to be eaten raw; but to men upon the verge of starvation there is no inconvenience in this. Indeed, there are many tribes of South-Sea Islanders—not such savage either—who habitually eat the flesh of the shark—both the blue and white species—without thinking it necessary even to warm it over a fire! Neither did the castaway English sailor nor his young comrade think it necessary. Even had a fire been possible, they were too hungry to have stayed for the process of cooking; and both, without more ado, dined upon raw shark-meat.

When they had succeeded in satisfying the cravings of hunger, and once more refreshed themselves with a draught from their extemporised water-bag, the castaways not only felt a relief from actual suffering, but a sort of cheerful confidence in the future. This arose from a conviction on their part, or at all events a strong impression, that the hand of Providence had been stretched out to their assistance. The flying-fish, the shower, the shark may have been accidents, it is true; but, occurring at such a time, just in the very crisis of their affliction, they were accidents that had the appearance of design,—design on the part of Him to whom in that solemn hour they had uplifted their voices in prayer.

It was under this impression that their spirits became naturally restored; and once more they began to take counsel together about the ways and means of prolonging their existence.

It is true that their situation was still desperate. Should a storm spring up,—even an ordinary gale,—not only would their canvas water-cask be bilged, and its contents spilled out to mingle with the briny billow, but their frail embarkation would be in danger of going to pieces, or of being whelmed fathoms deep under the frothing waves. In a high latitude, either north or south, their chance of keeping afloat would have been slight indeed. A week, or rather only a single day, would have been as long as they could have expected that calm to continue; and the experienced sailor knew well enough that anything in the shape of a storm would expose them to certain destruction. To console him for this unpleasant knowledge, however, he also knew that in the ocean, where they were then afloat, storms are exceedingly rare, and that ships are often in greater danger from the very opposite state of the atmosphere,—from calms. They were in that part of the Atlantic Ocean known among the early Spanish navigators as the Horse Latitudes,—so-called because the horses at that time being carried across to the New World, for want of water in the becalmed ships, died in great numbers, and being thrown overboard were often seen floating upon the surface of the sea.

A prettier and more poetical name have these same Spaniards given to a portion of the same Atlantic Ocean,—which, from the gentleness of its breezes, they have styled “La Mar de las Damas” (the Ladies’ Sea).

Ben Brace knew that in the Horse Latitudes storms were of rare occurrence; and hence the hopefulness with which he was now looking forward to the future.

He was no longer inactive. If he believed in the special Interference of Providence, he also believed that Providence would expect him to make some exertion of himself,—such as circumstances might permit and require.

Chapter Twelve.

Flensing a Shark.

The flesh of the shark, and the stock of water so singularly obtained and so deftly stored away, might, if properly kept and carefully used, last them for many days; and to the preservation of these stores the thoughts of the sailor and his young companion were now specially directed.

For the former they could do nothing more than had been already done,—further than to cover the tarpauling that contained it with several folds of the spare sail-cloth, in order that no ray of the sun should get near it. This precaution was at once adopted.

The flesh of the shark—now dead as mutton—if left to itself, would soon spoil, and be unfit for food, even for starving men. It was this reflection that caused the sailor and his protégé to take counsel together as to what might be done towards preserving it.

They were not long in coming to a decision. Shark-flesh, like that of any other fish—like haddock, for instance, or red herrings—can be dried in the sun; and the more readily in that sun of the torrid zone that shone down so hotly upon their heads. The flesh only needed to be cut into thin slices and suspended from the upright oars. The atmosphere would soon do the rest. Thus cured, it would keep for weeks or months; and thus did the castaways determine to cure it.

No sooner was the plan conceived, than they entered upon its execution. Little William again seized the cord of sennit, and drew the huge carcass close up to the raft; while Ben once more opened the blade of his sailor’s knife, and commenced cutting off the flesh in broad flakes,—so thin as to be almost transparent.

He had succeeded in stripping off most of the titbits around the tail, and was proceeding up the body of the shark to flense it in a similar fashion, when an ejaculation escaped him, expressing surprise or pleasant curiosity.

Little William was but too glad to perceive the pleased expression on the countenance of his companion,—of late so rarely seen.

“What is it, Ben?” he inquired, smilingly.

“Look ’ee theer, lad,” rejoined the sailor, placing his hand upon the back of the boy’s head, and pressing it close to the edge of the raft, so that he could see well down into the water,—“look theer, and tell me what you see.”

“Where?” asked William, still ignorant of the object to which his attention was thus forcibly directed.

“Don’t you see somethin’ queery stickin’ to the belly of the shark,—eh, lad?”

“As I live,” rejoined William, now perceiving “somethin’”, “there’s a small fish pushing his head against the shark,—not so small either,—only in comparison with the great shark himself. It’s about a foot long, I should think. But what is it doing in that odd position?”

“Sticking to the shark,—didn’t I tell ’ee, lad!”

“Sticking to the shark? You don’t mean that, Ben?”

“But I do—mean that very thing, boy. It’s as fast theer as a barnacle to a ship’s copper; an’ ’ll stay, I hope, till I get my claws upon it,—which won’t take very long from now. Pass a piece o’ cord this way. Quick.”

The boy stretched out his hand, and, getting hold of a piece of loose string, reached it to his companion. Just as the snare had been made for the shark with the piece of sennit, and with like rapidity, a noose was constructed on the string; and, having been lowered into the water, was passed around the body of the little fish which appeared adhering to the belly of the shark. Not only did it so appear, but it actually was, as was proved by the pull necessary to detach it, and which required all the strength that lay in the strong arms of the sailor.

He succeeded, however, in effecting his purpose; and with a pluck the parasite fish was separated from the skin to which it had been clinging, and, jerked upwards, was landed alive and kicking upon the raft.

Its kicking was not allowed to continue for long. Lest it might leap back into the water, and, sluggish swimmer as it was, escape out of reach, Ben, with the knife which he still held unclasped in his hand, pinned it to one of the planks, and in an instant terminated its existence.

“What sort of a fish is it?” asked William, as he looked upon the odd creature thus oddly obtained.

“Suckin’-fish,” was Ben’s laconic answer.

“A sucking-fish! I never heard of one before. Why is it so-called?”

“Because it sucks,” replied the sailor.

“Sucks what?”

“Sharks. Didn’t you see it suckin’ at this ’un afore I pulled it from the teat? Ha! ha! ha!”

“Surely it wasn’t that, Ben?” said the lad, mystified by Ben’s remark.

“Well, boy, I an’t, going to bamboozle ye. All I know is that it fastens onto sharks, and only this sort, which are called white sharks; for I never seed it sticking to any o’ the others,—of which there be several kinds. As to its suckin’ anythin’ out o’ them an’ livin’ by that, I don’t believe a word o’ it; though they say it do so, and that’s what’s given it its name. Why I don’t believe it is, because I’ve seed the creature stickin’ just the same way to the coppered bottom o’ a ship, and likewise to the sides o’ rocks under the water. Now, it couldn’t get anything out o’ the copper to live upon, nor yet out o’ a rock,—could it?”

“Certainly not.”

“Then it couldn’t be a suckin’ them. Besides, I’ve seed the stomachs o’ several cut open, and they were full of little water-creepers,—such as there’s thousands o’ kinds in the sea. I warrant if we rip this ’un up the belly, we’ll find the same sort o’ food in it.”

“And why does it fasten itself to sharks and ships,—can you tell that, Ben?”