1920

Tennant and Ward, New York

Publisher's Agents

1920

Illustrations

- APRIL FLURRIESBy W. A. Alcock, Brooklyn, N.Y.

- PUCKACHIPE—SEAGULLBy Elizabeth R. Allen, Moorestown, N.J.

- MY LITTLE GRAY HOME IN THE WESTBy George M. Allen, Portland, Ore.

- THE BUDDHABy Fred R. Archer, Los Angeles, Cal.

- ISLANDERSBy Laura Adams Armer, Berkeley, Cal.

- ANN SPENCERBy Jessie Tarbox Beals, New York

- EARLY MORNINGBy David W. Bonnar, Buffalo, N. Y.

- A BIT OF HOME LIFEBy Will D. Brodhun, Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

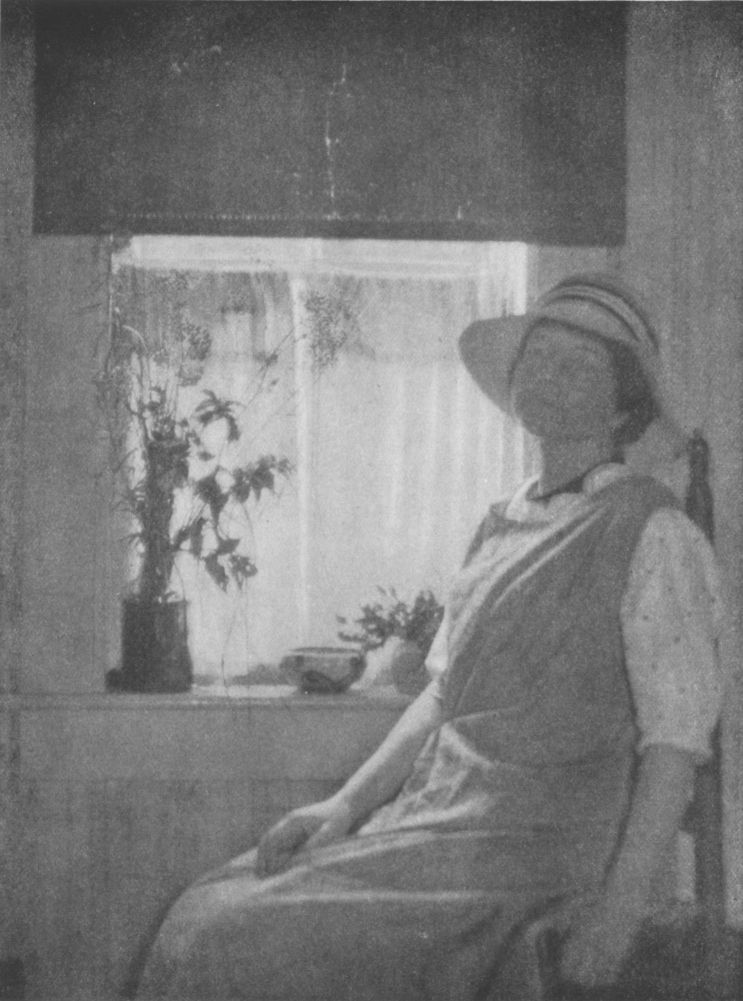

- A MOMENT'S RESTBy Gertrude L. Brown, Evanston, Ill.

- DANCERSBy John C. Burkhardt, Portland, Ore.

- DOUARNENEZ, FINISTÈREBy Dr. A. D. Chaffee, New York

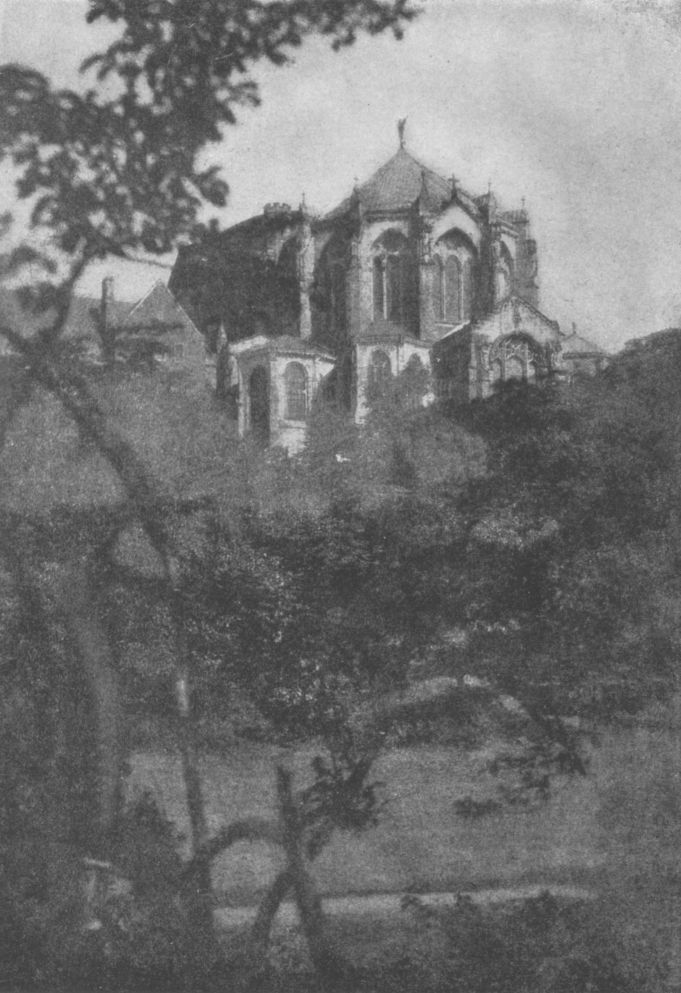

- RHEIMSBy Arthur D. Chapman, New York

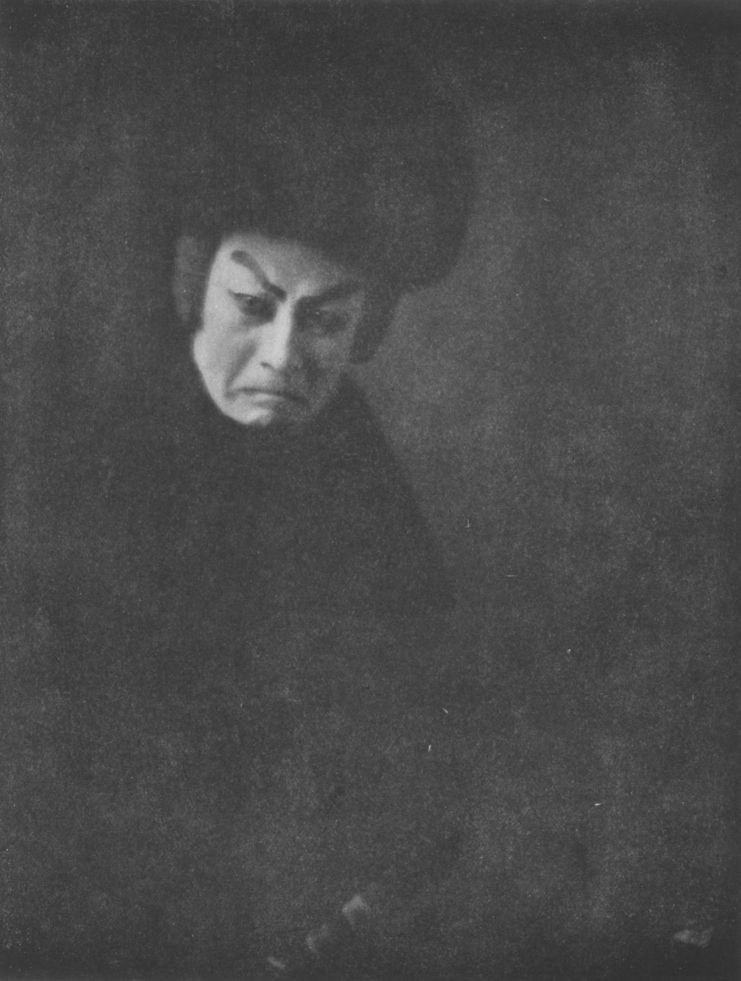

- MICHIO ITOROBy Alvin Langdon Colburn, New York

- THE STREETBy Alfred Cohn, Brooklyn, N. Y.

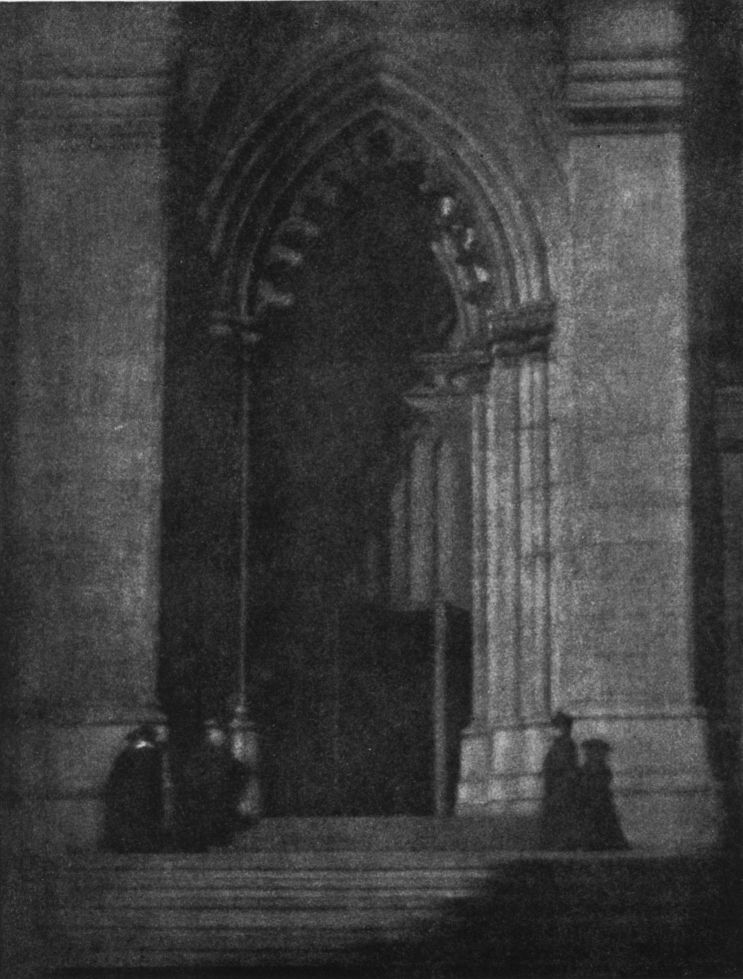

- ST. JOHN'S CATHEDRALBy James Copella, New York

- MR. MATSUMOTO KOSHIRO AS “TCHIKAWA GOYEMON” (THE ROBIN HOOD OF JAPAN)By C. P. Crowther, Kobe, Japan

- SPRING O' THE YEARBy Helen W. Drew, Montclair, N. J.

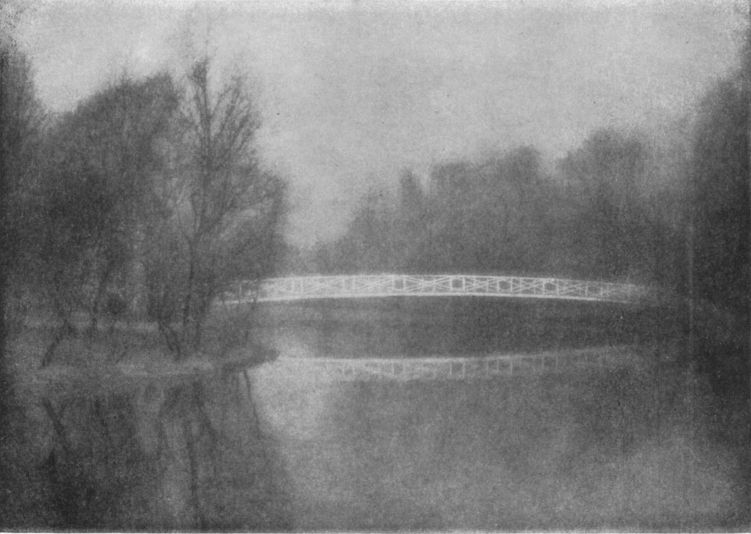

- THE LIFTING MISTBy Jerry D. Drew, Montclair, N. J.

- THE DOORWAYBy Dwight A. Davis, Worcester, Mass.

- HIGH BRIDGEBy Edward R. Dickson, New York City

- MRS. VERNON CASTLEBy De Meyer, New York

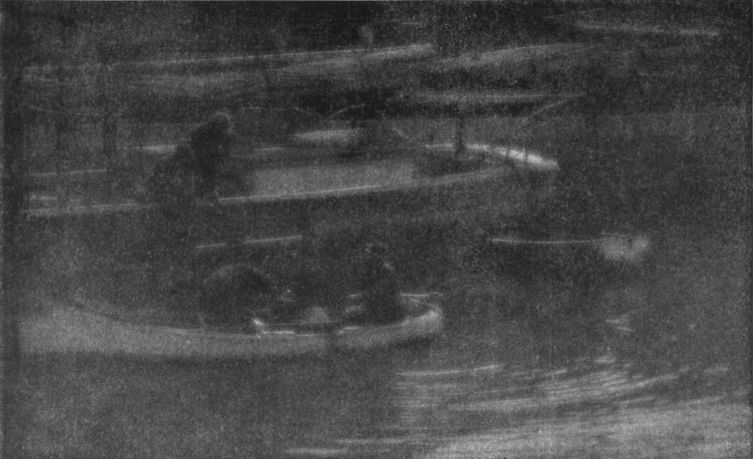

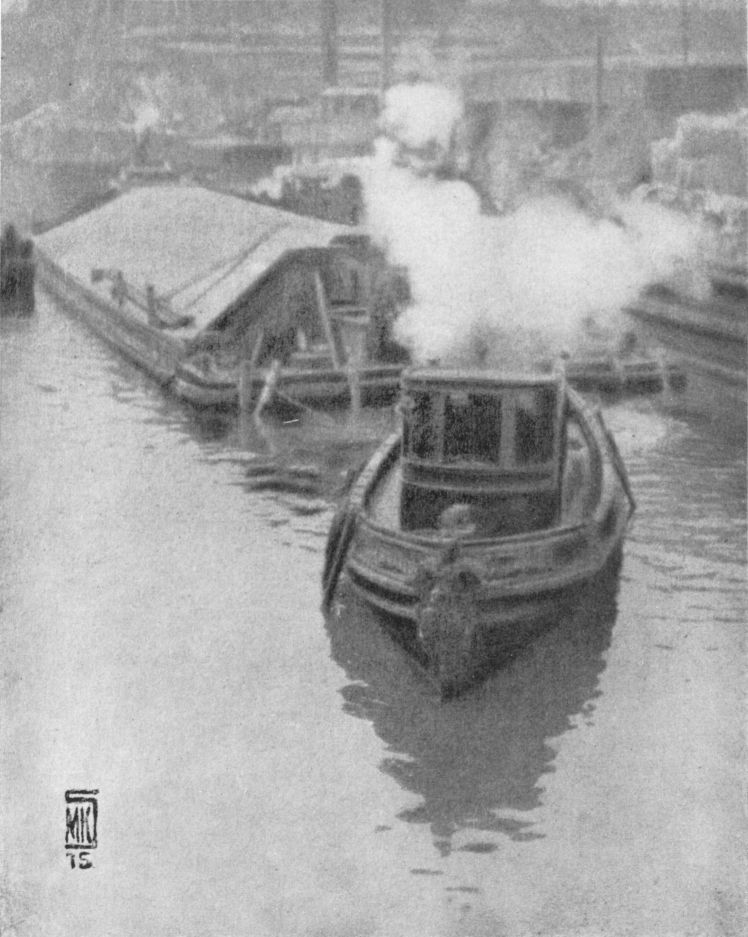

- BOATSBy E. G. Dunning, New York

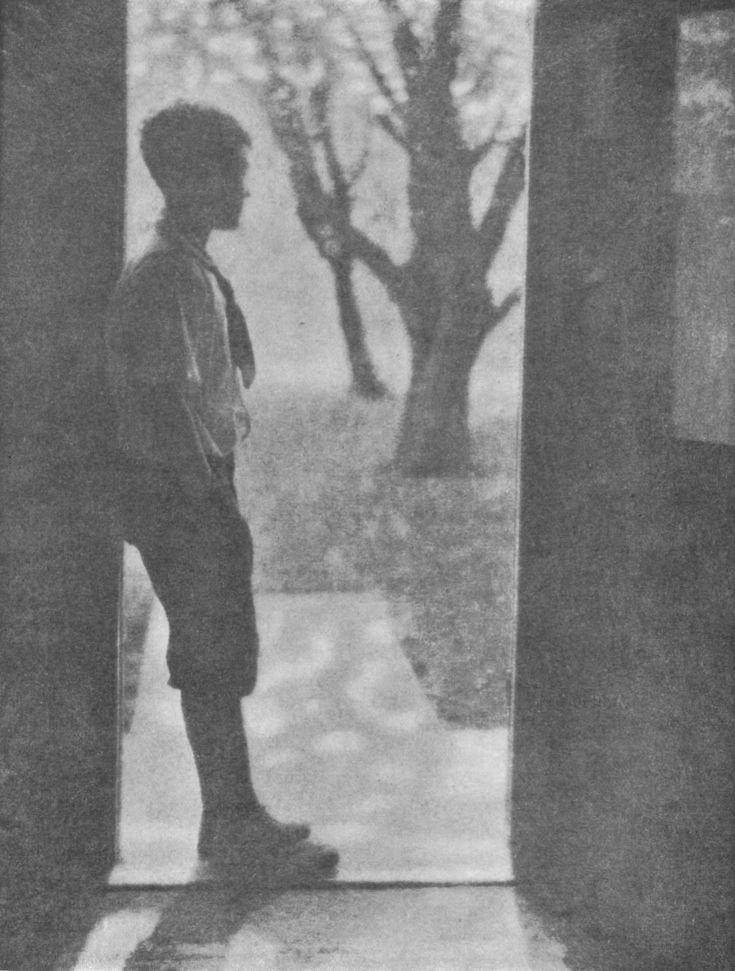

- COMING TO SCHOOLBy Vernon Everett Duroc, Brooklyn, N. Y.

- STUDYBy William B. Dyer, Portland, Ore.

- DESIGN FOR A TAPESTRYBy John Paul Edwards, Sacramento, Cal.

- STUDYBy Adelaide Wallach Ehrich, New York

- LANDSCAPEBy Eleanor C. Erving, Albany, N. Y.

- SUGARLOAF MOUNTAINBy W. H. Evans, Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

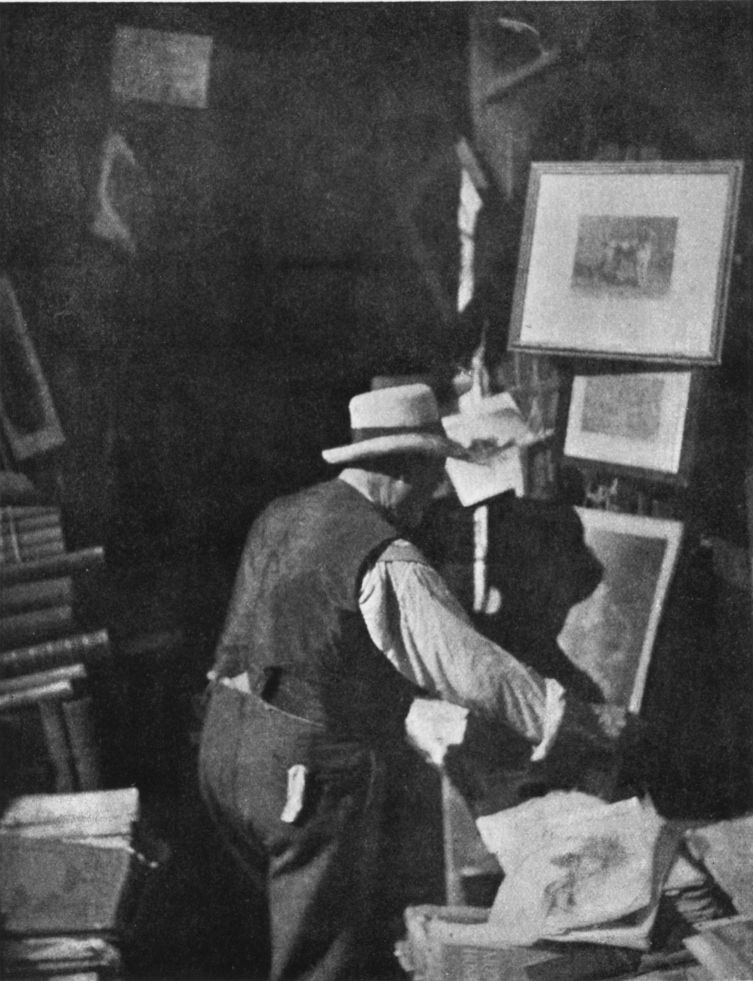

- SIDEWALK TREASURESBy O. E. Fischer, M. D., Detroit, Mich.

- THE GIRL FROM DELHIBy Louis Fleckenstein, Los Angeles, Cal.

- FIFTY YEARSBy Frederick Frittita, Baltimore, Md.

- WATER SCENEBy John Wallace Gillies, New York

- THE MARBLE CUTTERSBy Laura Gilpin, Colorado Springs, Col.

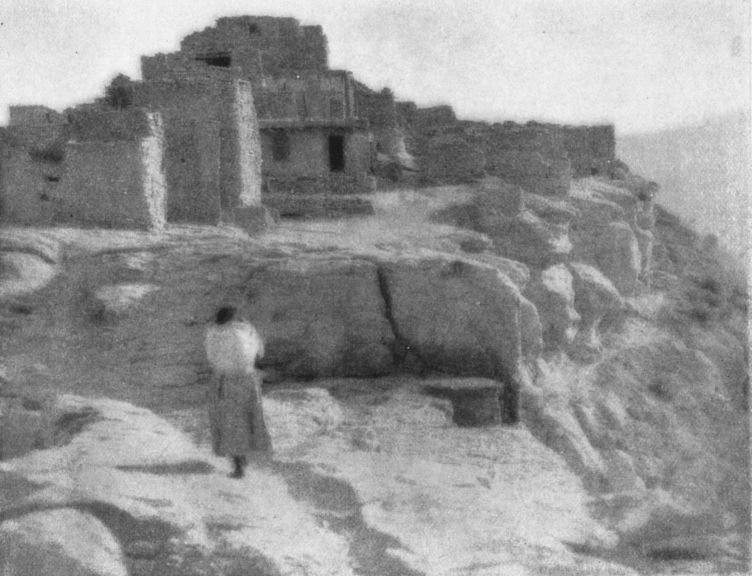

- WALPIBy Forman Hanna, Globe, Ariz.

- THE SHORE LINEBy G. H. S. Harding, Berkeley, Cal.

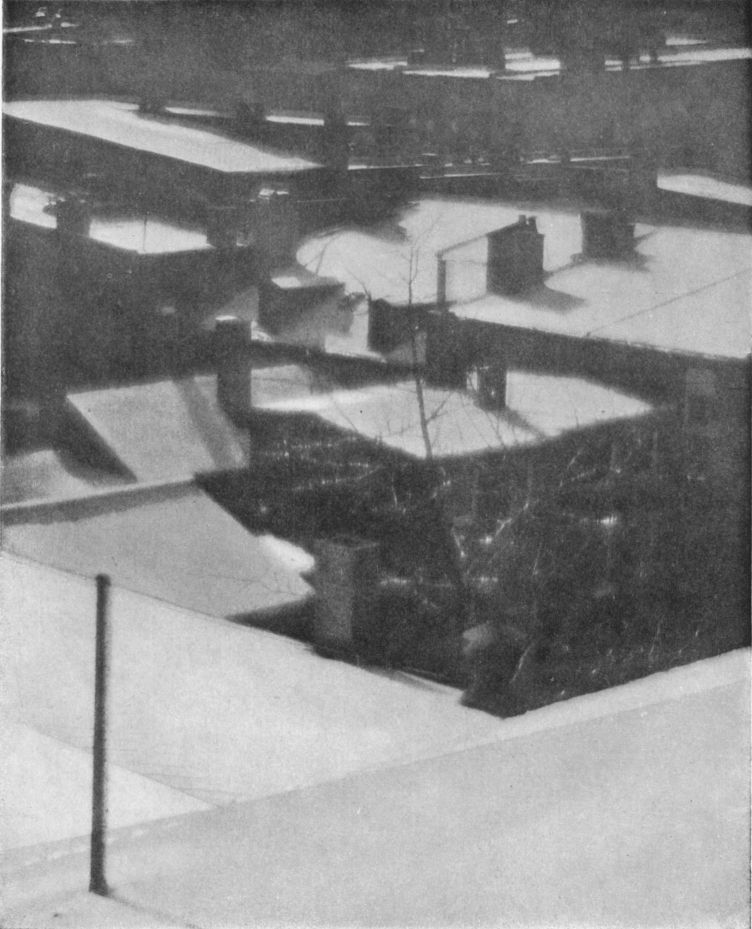

- APRIL SNOWBy Edward Heim, New York

- DAY DREAMSBy G. W. Harting, New York

- IN THE ARBORBy Antoinette B. Hervey, New York

- MISS H.By George Henry High, Chicago, Ill.

- SUNSHINEBy L. Willis Hoops, New York

- THE WHITE HATBy G. B. Hollister, Corning, N. Y.

- DESIGNBy Bernard S. Horne, Princeton, N. J.

- CITY STREETBy Blanche C. Hungerford (Mrs. Latimer), High Bridge, N. J.

- COLUMBIA UNIVERSITYBy Dr. Charles H. Jaeger, New York

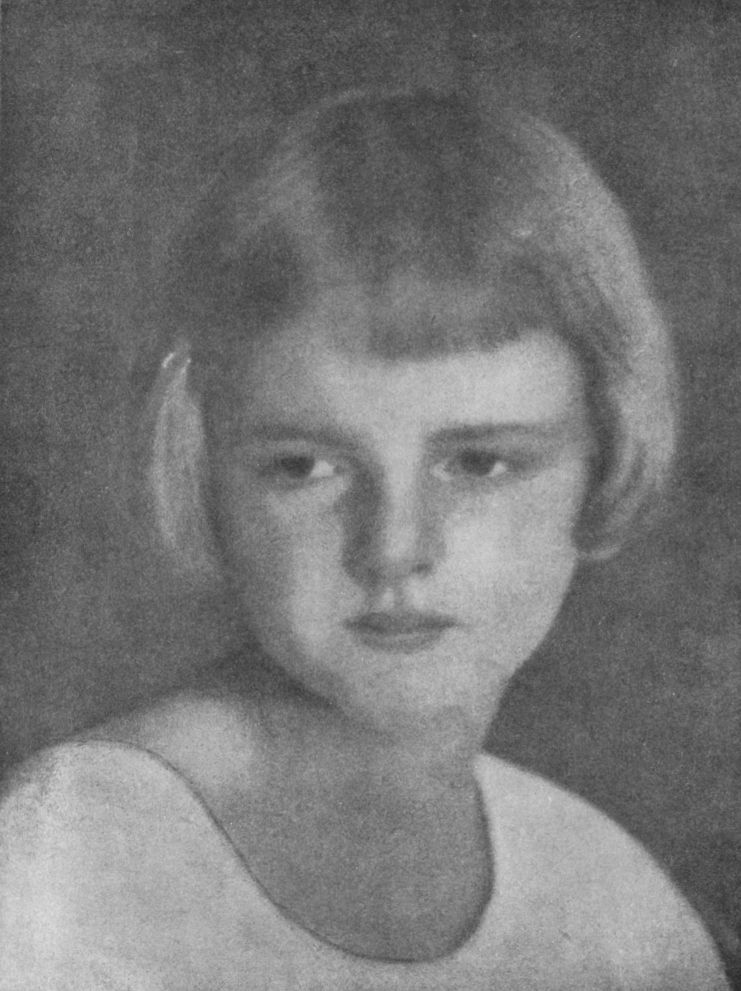

- PORTRAIT OF A CHILDBy Doris U. Jaeger, New York

- THE VALE OF THE SHADOWBy Arthur F. Kales, Los Angeles, Cal.

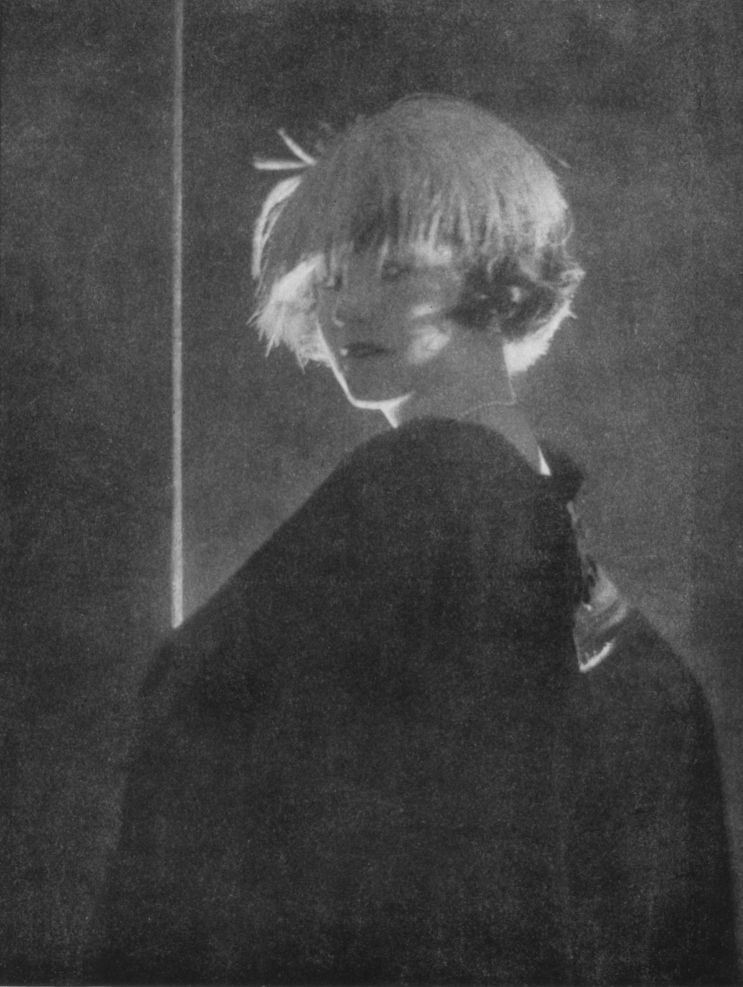

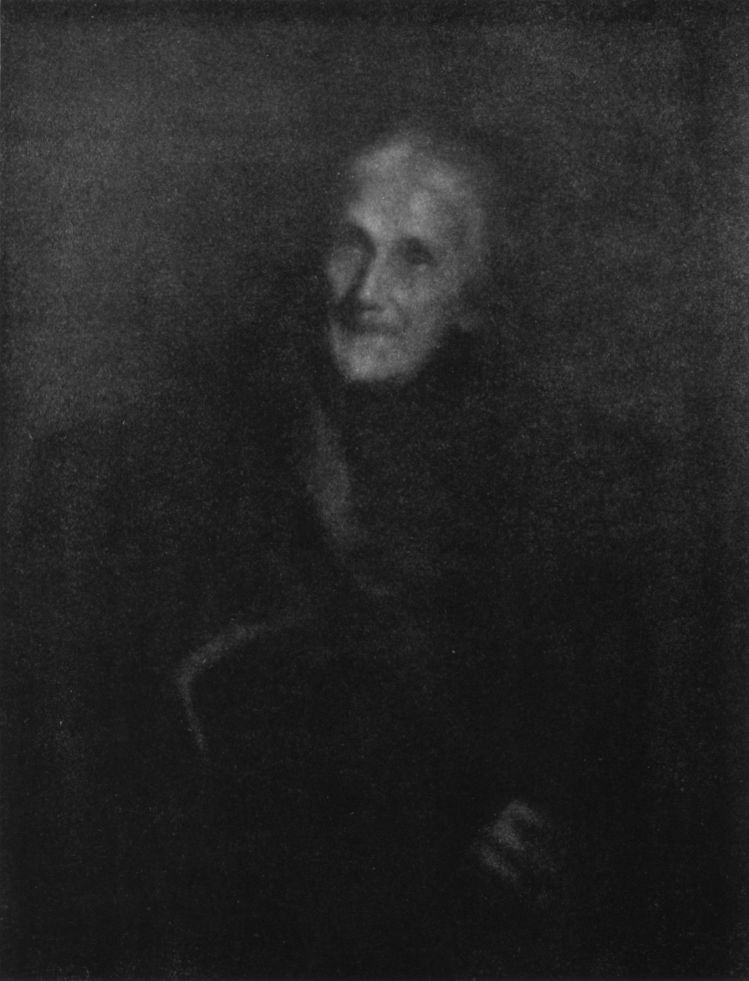

- PORTRAITBy Gertrude Kasebier, New York

- OLD HILL TOWNBy William Kriebel, Philadelphia, Pa.

- SOLITUDEBy W. R. Latimer, High Bridge, N. J.

- ELLENBy Sophie L. Lauffer, Brooklyn, N. Y.

- MASTER JOHN SPEERBy George P. Lester, Bloomfield, N. J.

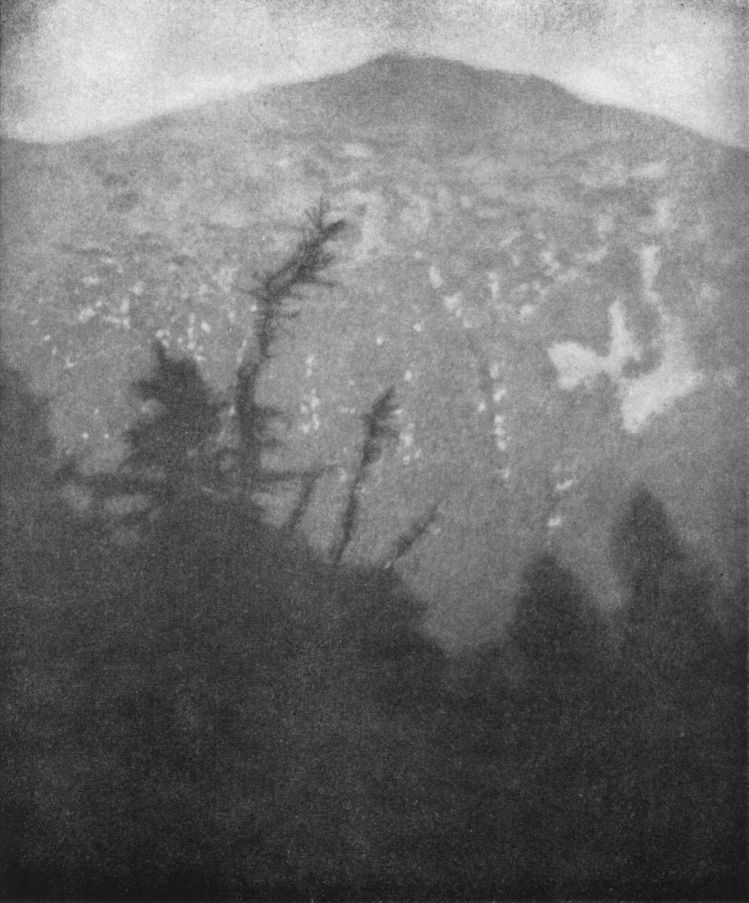

- MOUNT ADAMS OF THE NORTHERN LAKESBy Francis Orville Libby, Portland, Me.

- MISTS TO-DAY—CLEAR ANONBy Edwin Loker, St. Louis, Mo.

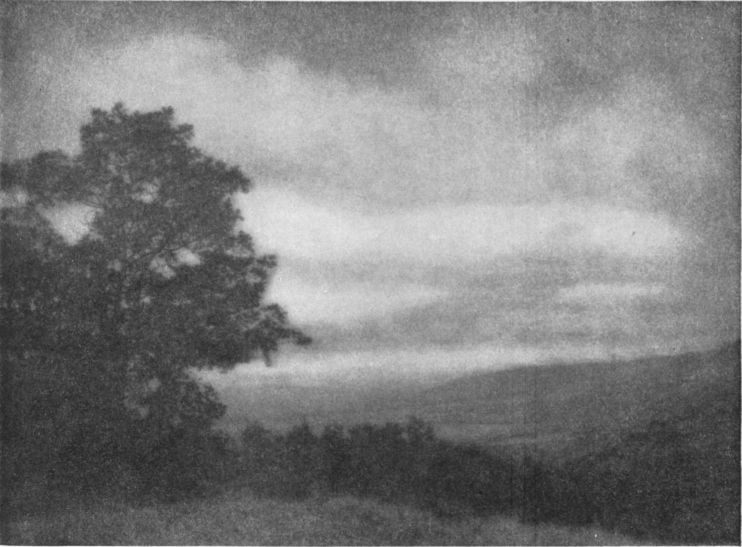

- TREES AND CLOUDSBy Dr. William F. Makk, Los Angeles, Cal.

- PLAYER ON THE YIT-KIMBy Margrethe Mather, Los Angeles, Cal.

- ON LAKE PATZCUARO, MEXICOBy Oscar Maurer, Los Angeles, Cal.

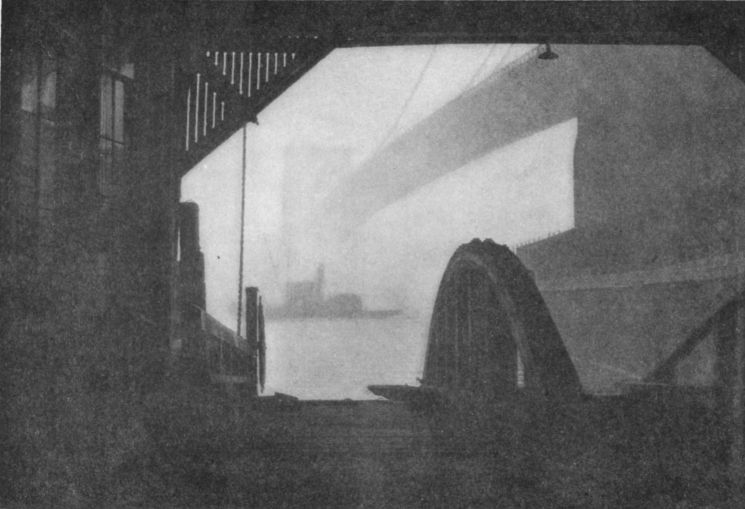

- ALONG THE WHARFBy Holmes I. Mettee, Baltimore, Md.

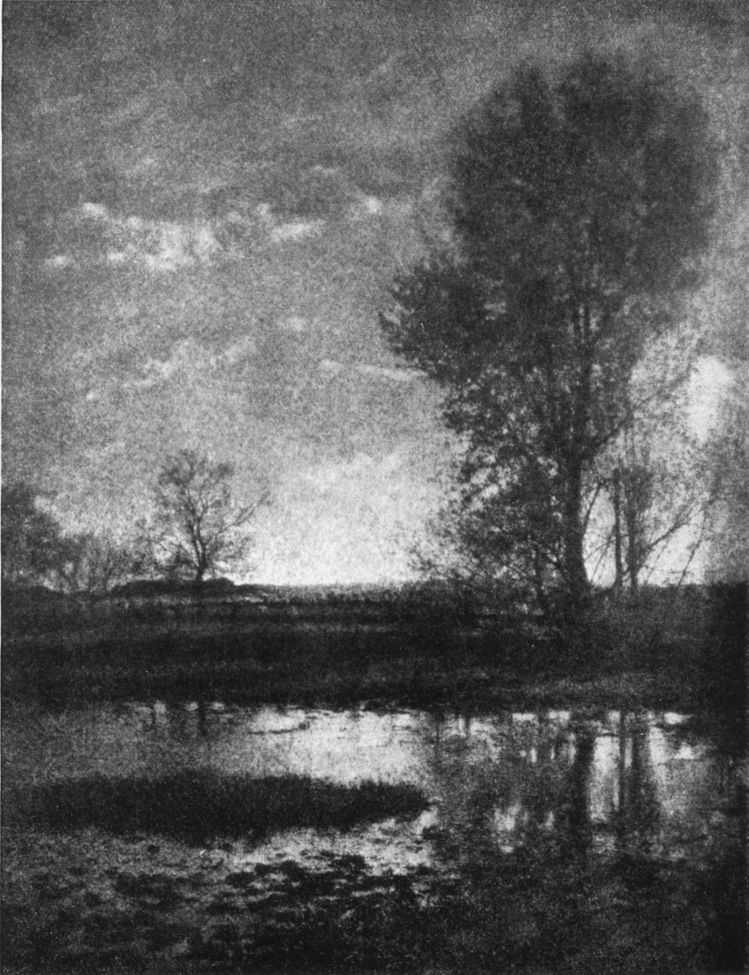

- THE MARSH—EVENINGBy J. George Midgley, Salt Lake City, Utah

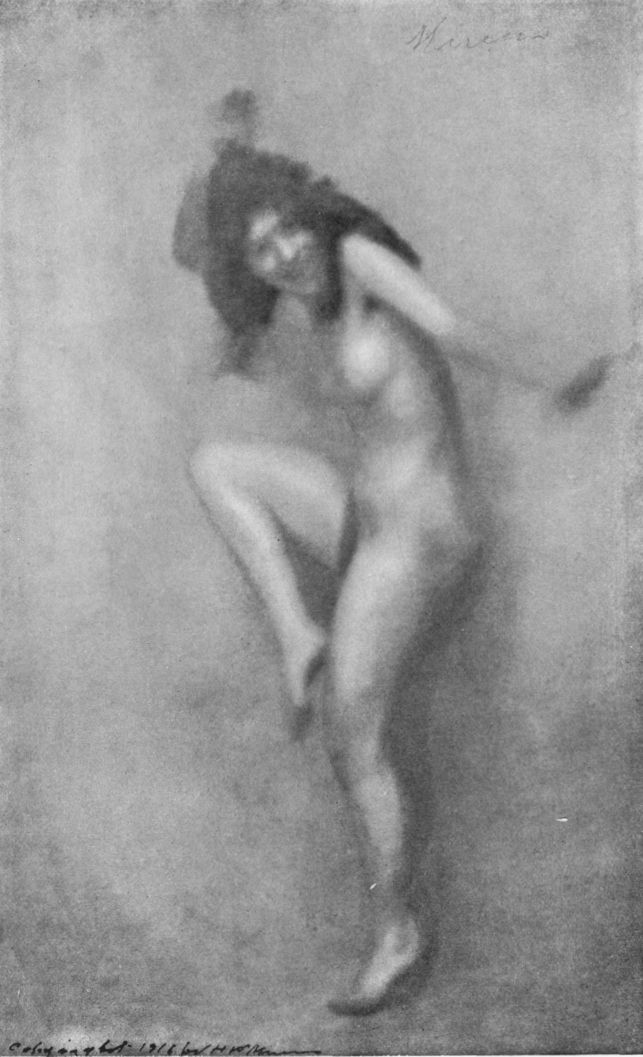

- THE DANCERBy H. W. Minns, Akron, Ohio

- SNOW PATTERNBy H. Remick Neeson, Baltimore, Md.

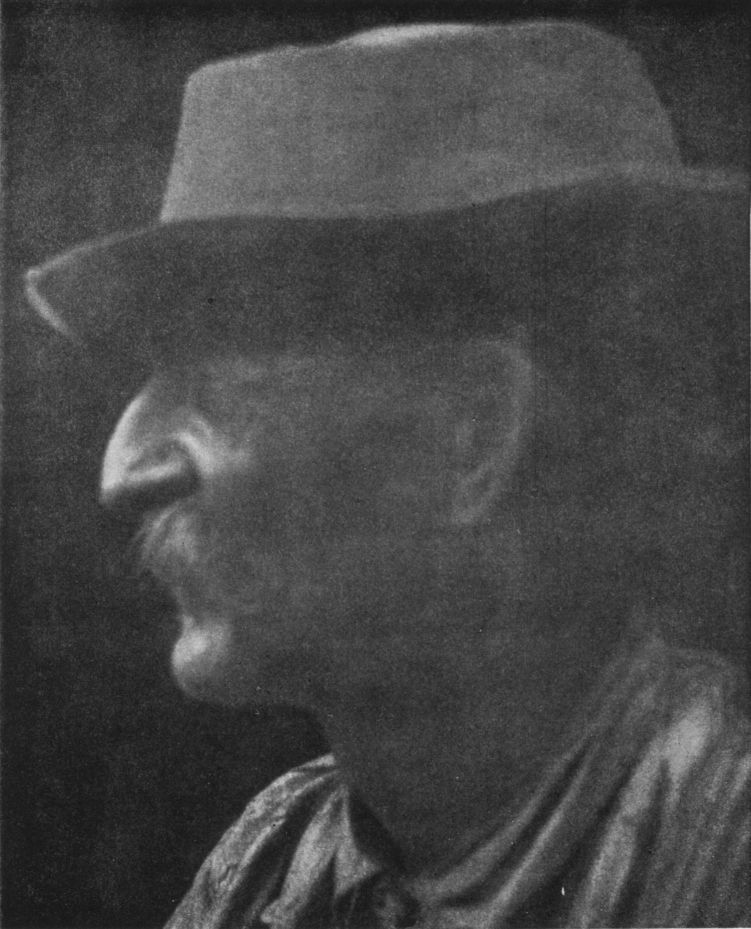

- THE FARMERBy Henry Hoyt Moore, Brooklyn, N. Y.

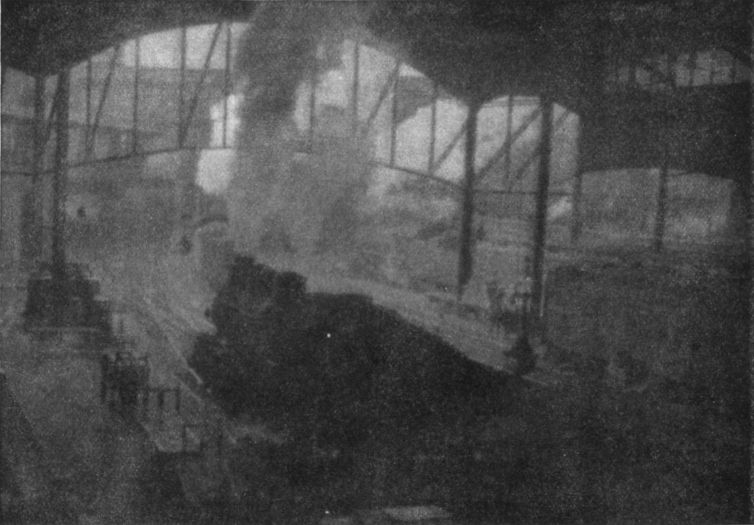

- STEAM UPBy J. W. Newton, Columbus, Ohio

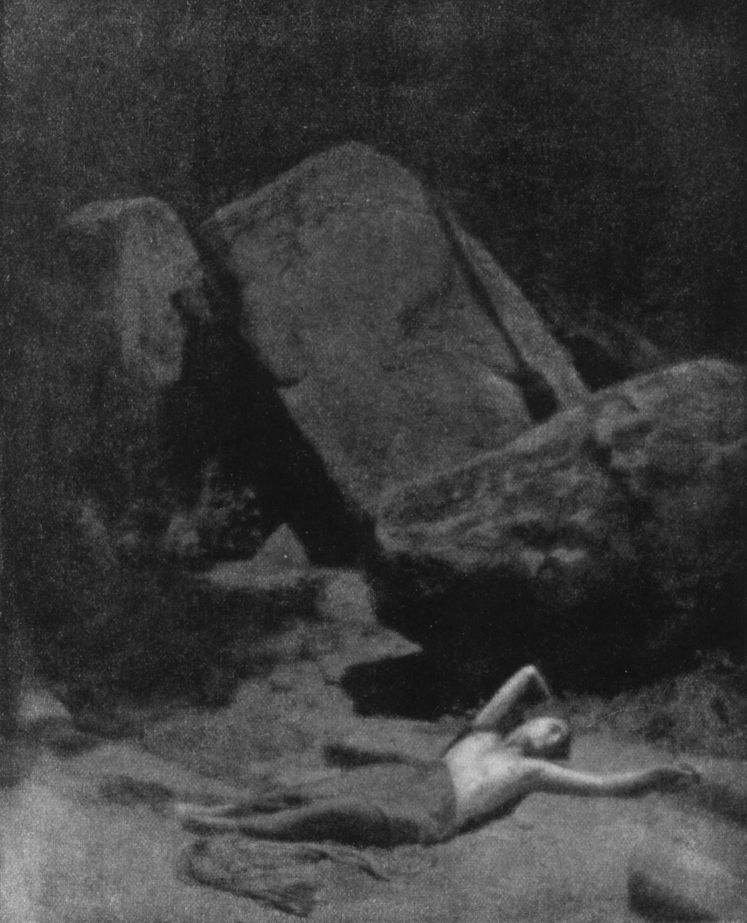

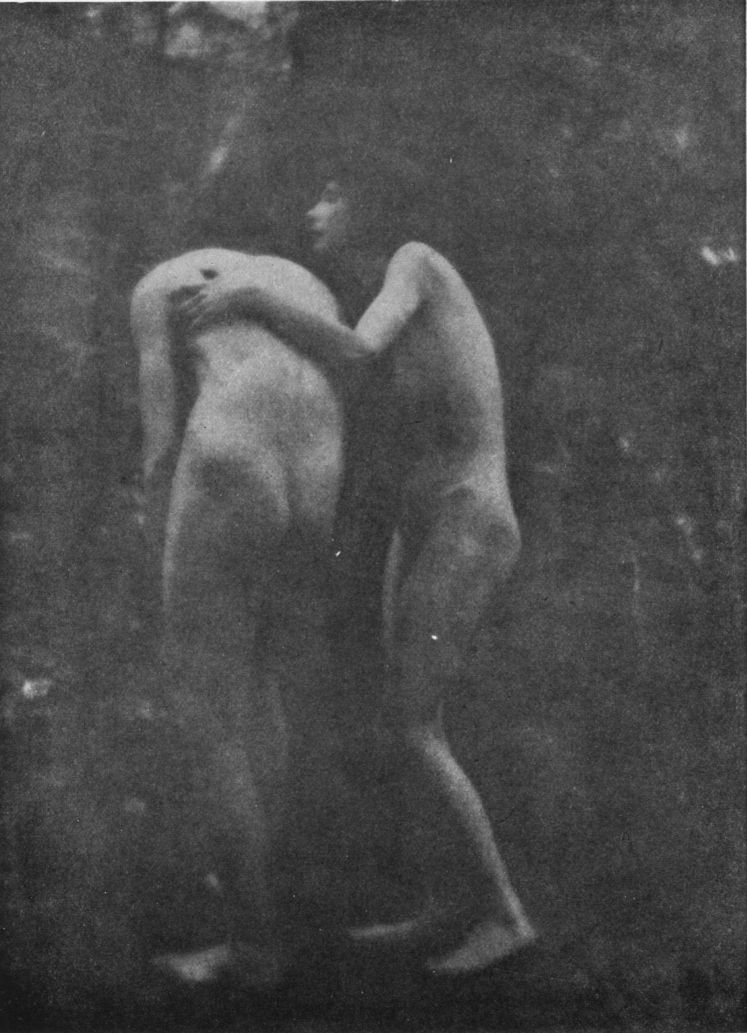

- EVE REPENTENTBy Imogen Cunningham Partridge, San Francisco, Cal.

- SWANSBy G. Houson Payne, Jr., Baltimore, Md.

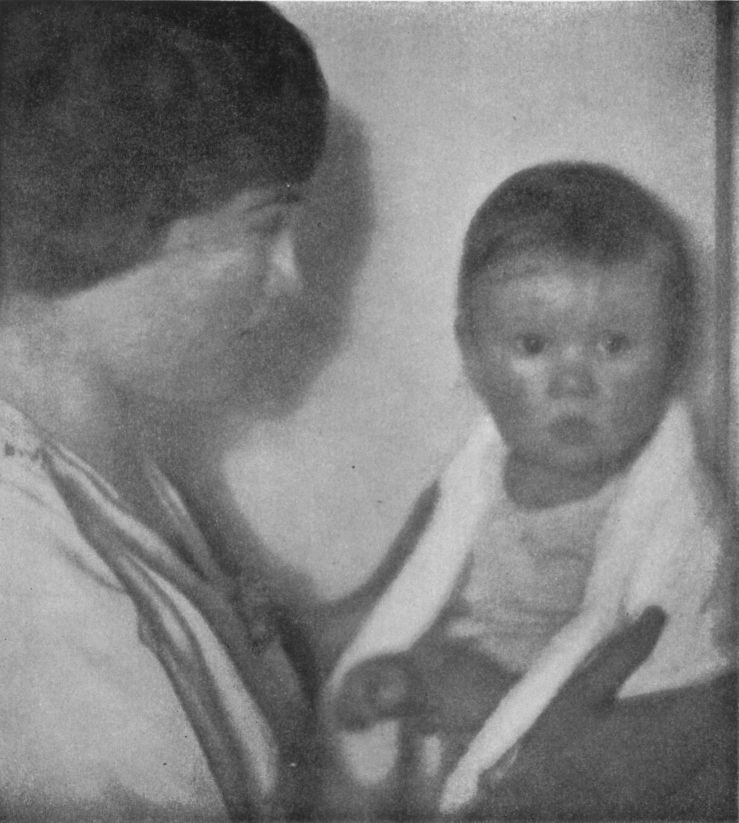

- MOTHER AND CHILDBy Margaret Rhodes Peattie, Chicago, Ill.

- PLACING A PICTUREBy Leo Pokras, Brooklyn, N. Y.

- TWILIGHT'S MYSTERYBy W. H. Porterfield, Buffalo, N. Y.

- THE MORNING BOATBy E. M. Pratt, Tracy, Cal.

- SWEET SIXTEENBy Mrs. William H. Rau, Philadelphia, Pa.

- MOTHERBy Jane Reece, Dayton, Ohio

- THE HUSBANDMANBy O. C. Reiter, Pittsburgh, Pa.

- THE LAST OF HIS RACEBy L. M. A. Roy, La Crosse, Wis.

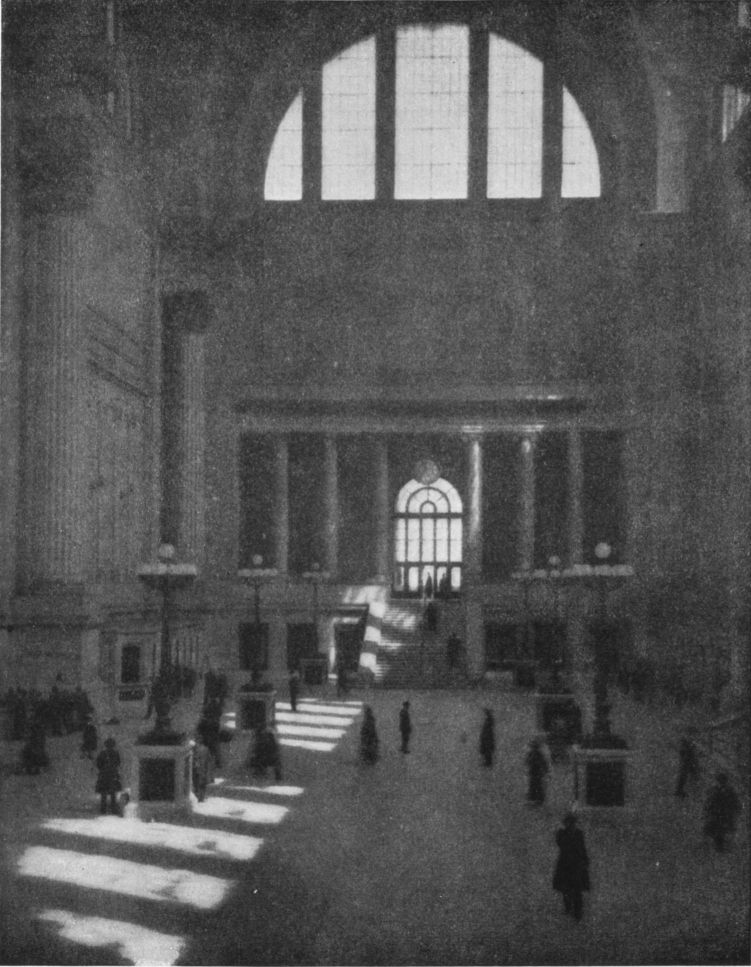

- PENNSYLVANIA STATION, NEW YORKBy Dr. D. J. Ruzicka, New York

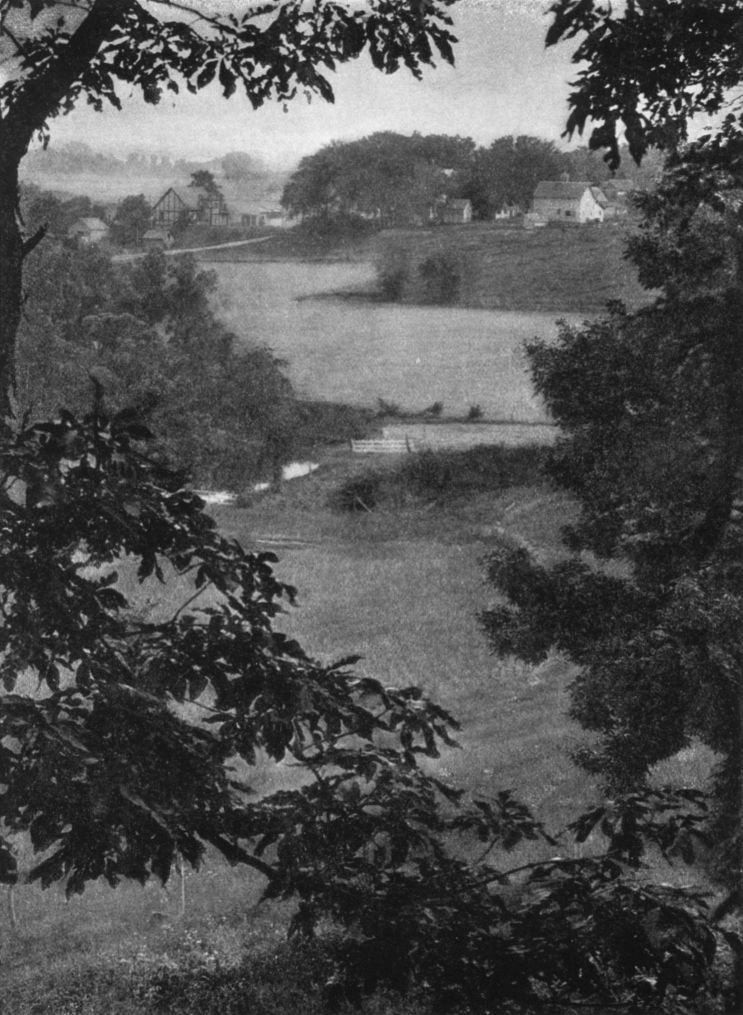

- A GLIMPSE OF PLEASANT VALLEYBy J. G. Sarvent, Kansas City, Mo.

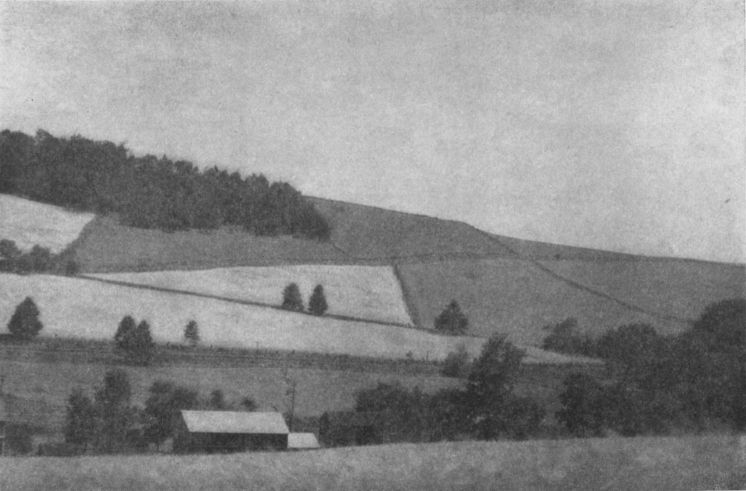

- THE VALLEY BEYOND OUR HILLBy Otto C. Shulte, San Franciso, Cal.

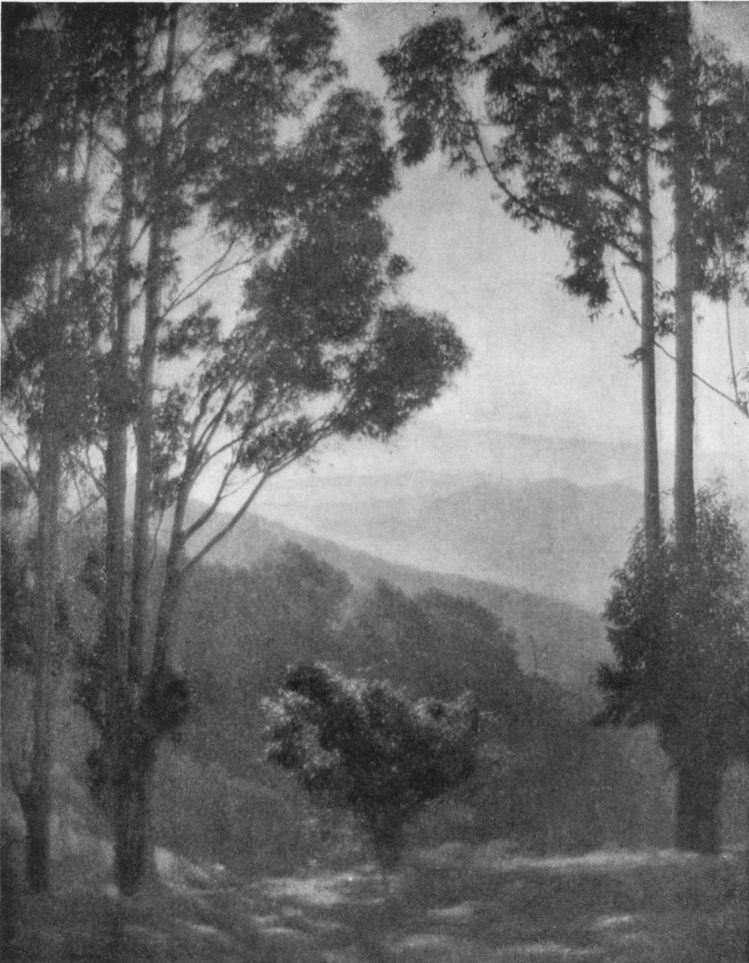

- ELYSIAN PARK VISTABy David J. Sheahan, Los Angeles, Cal.

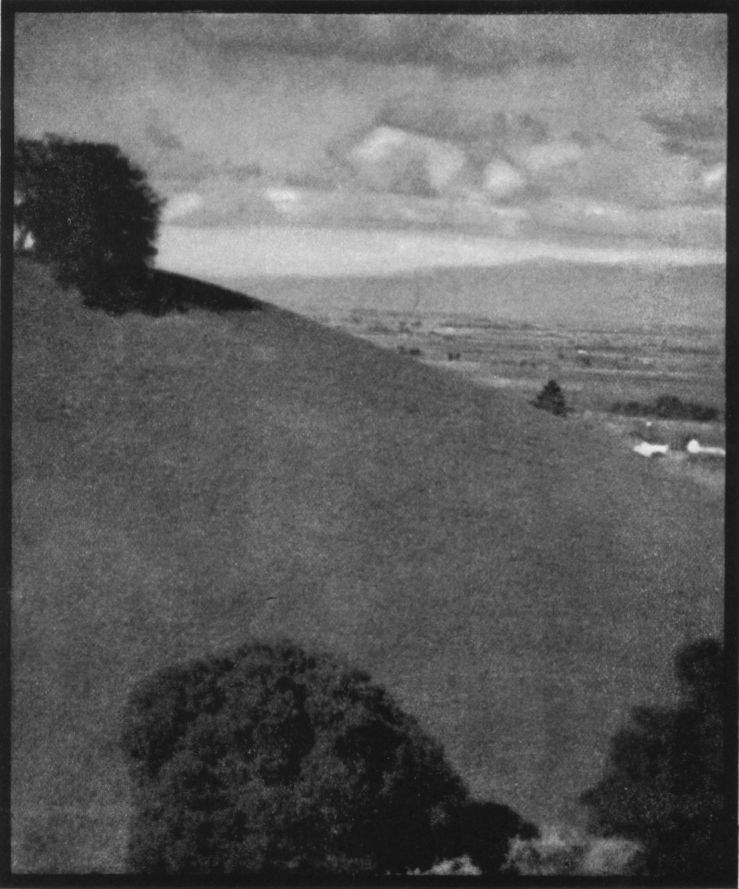

- IN THE FOOTHILLS OF THE WASATCHBy Thomas O. Sheckell, Salt Lake City, Utah

- DOORWAY OF ST. PATRICK'S CATHEDRALBy William Gordon Shields, New York

- PORTRAITBy Mrs. Sterling Smith, San Diego, Cal.

- THE COLUMNSBy E. Radiker Standcliff, Elmira, N. Y.

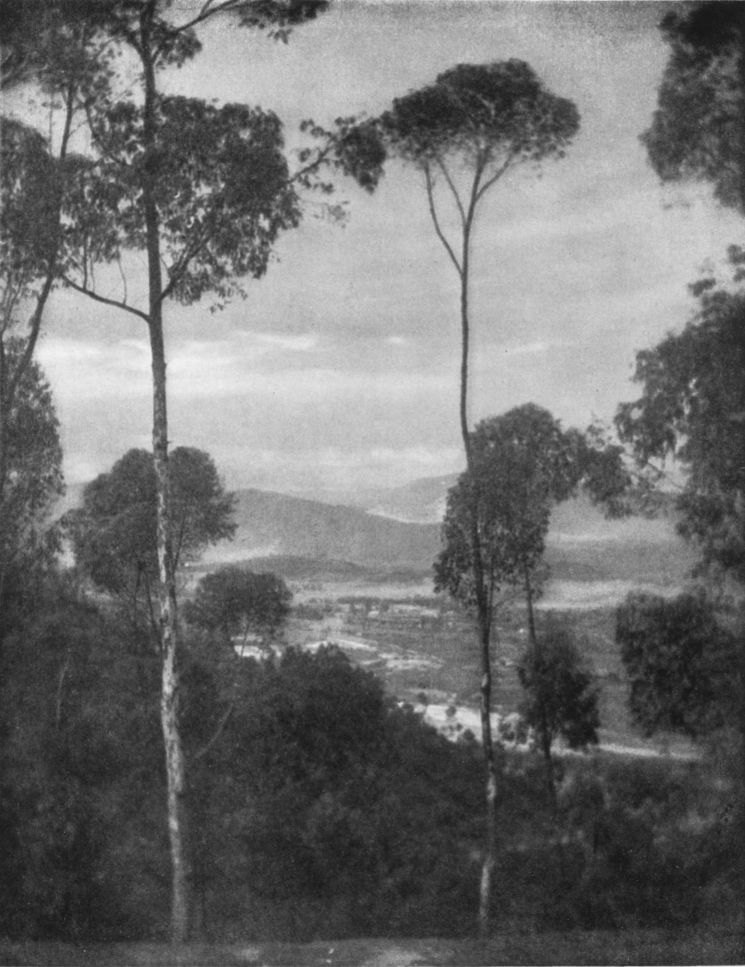

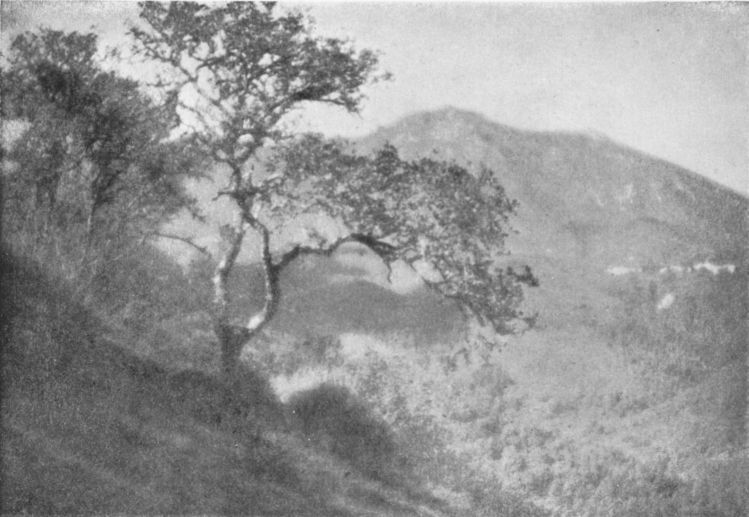

- TOWARD TAMALPAISBy W. H. Stephens, San Franciso, Cal.

- MAE MURRAYBy Ford Sterling, Los Angeles, Cal.

- MARGARETBy John H. Stocksdale, Baltimore, Md.

- THE CANALBy M. Sugimoto, New York

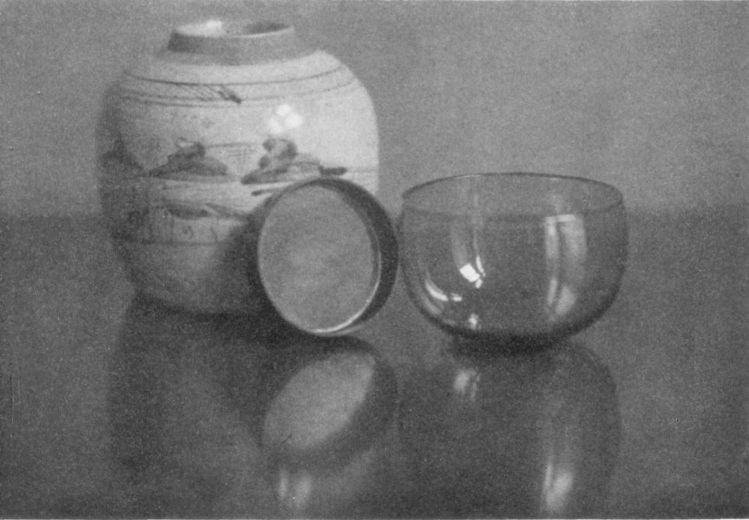

- STILL LIFEBy Elizabeth Talcott, Elmwood, Conn.

- THE HOUSE O' DREAMSBy William H. Thompson, Hartford, Conn.

- WITH FACE SET TOWARD THE WESTERN FRONTBy Lieut. Edward Larocque Tinker, U. S. N., New York

- SHIFTING SANDBy Charles Vandervelde, Grand Rapids, Mich.

- RUTH ST. DENISBy the late Lieut. Luke R. Vickers, Church Creek, Md.

- THE NEW YEAR'S EDITIONBy Will H. Walker, Portland, Ore.

- GIRL WITH THE FANBy Mabel Watson, Pasadena, Cal.

- ELEANORBy Delight Weston, Blue Hill, Me.

- EPILOGUEBy Edward Weston, Glendale, Cal.

- MRS. M.By Leonard Westphalen, Chicago, Ill.

- THE FAMILYBy Clarence H. White, New York

- THE FLOWER GARDENBy Cornelia F. White, New York

- THROUGH THE WINDOWBy Hazel Jane Wiegner, Philadelphia, Pa.

- MARIONETTEBy Edith R. Wilson, Mount Vernon, N. Y.

- JEANBy Mildred R. Wilson, Orange, N. J.

- CITY BEYONDBy N. S. Wooldridge, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Contents

- FOREWORD

- The Pictorial Photographers of America

- Pictorial Photography in New Jersey

- Pictorial Photograpny in Maine

- Pictorial Photography in Massachusetts

- Pictorial Photograpky in Maryland

- Middle West Activities and the Pittsburgh Salon

- Pictorial Photography in the Far West

- Illustrations

- The following is a partial list of photographic organizations in America which are encouraging pictorial Photography

FOREWORD

[pg 5]To many people photography is merely a mechanical process. To an increasing number, however, photography is being seen as an art, by which personal impressions of nature or human life may be expressed as truly as by the brush. These workers in photography see in it a medium by which the action of light upon sensitive surfaces may be so controlled as really to interpret scenes and persons in the individualistic spirit of a true art. From every part of our country come evidences of the growing appreciation of photography as a pictorial medium. Exhibitions in many museums which have hitherto been indifferent to pictures made with the lens have opened the eyes of the public to the possibilities of the camera. Clubs of photographic workers in various cities have maintained or fostered the movement. The lure of the moving picture has stimulated the interest of countless multitudes in photography, and the occasional presentation of fine pictorial work in this direction has given a prophecy of better things to come. The time, therefore, seems ripe to present in this book a collection of the work of American pictorial photographers in all sections of the country. Many of these workers are members of the organization known as the Pictorial Photographers of America; but the appeal for photographic material for this book has been confined to no one society or club, but has been widely inclusive of associations and individuals, and it is believed that the work here presented is fairly representative of the best American effort along these lines at the present time.

It is the hope and intention of the organization that publishes this book to stimulate interest in this branch of pictorial art. This is believed to be the first attempt in America to give a comprehensive presentation of the status of pictorial photography as illustrated by the product of many of its best workers. As such it is commended to the consideration of photographers both professional and amateur, of artists and art lovers, and of the public generally.

The Pictorial Photographers of America

The Association's Work and Aim

The Pictorial Photographers of America is an association having in mind solely the development of the art of photography from a standpoint of educational value. Its position is unique, since the worker is afforded not only an opportunity to exhibit his pictures in various museums and art galleries, but is made to feel that maintaining photographic standards and studying the arts for breadth of view are of chief importance.

Some of the advantages which photography offers are worth restating. It helps to draw one closer to nature and to seek fresh air. Through the exercise and cultivation of choice, it teaches how to decorate the home, to dress with taste, and to keep an alert eye and mind on the passing events of the world. Because the Association knows that photography is able to teach these things, it sought the aid of art museums and public libraries to conduct photographic exhibitions so that children and adults may not only see fine examples of the work of the camera in the hands of artists, but be led thereby to appreciate more fully the value of photography as an aid to interesting composition and a quickening of the eye in realizing the beauty of sunlight and shadows which flit around us much unrecognized at times. Succeeding in gaining the sympathetic co-operation of seventeen museums, in the winter of 1917-18 the Association collected, from many of the most important workers in this country, more than two hundred prints, which were divided into two groups and exhibited as follows:

Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Milwaukee Art Institute, Art Institute of Chicago, City Art Museum (St. Louis), Toledo Museum of Art, Detroit Museum of Art, Cleveland Art Museum, Cincinnati Museum of Art, Morristown Library, Newark Museum Association, New Britain (Conn.) Institute, Worcester Art Museum, Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts, Guild of Allied Arts (Buffalo), Grand Rapids Art Association, University of Oklahoma, New Orleans Art Association.

There was also held in New York City an exhibition of the work of the New England, New Jersey and Connecticut photographers, and among the immediate activities of the Association will be the holding in New York of exhibitions of the work of members of the Pacific Coast and other places, so that there may be established a fuller understanding of the points of view among the various pictorialists throughout the country.

The Association hopes to establish, in designated cities, pictorial centers where photographs may always be seen, and centers for intercourse and for exchange of views among workers. As a result of its plans, there will soon be opened a branch of the Pictorial Photographers of America, which will be called the Pacific Coast [pg 7] Chapter, embracing workers in the following States: Oregon, California, Wyoming, Nevada, and Utah. Meetings will be held monthly, and lectures and exhibitions arranged in co-operation with the parent body in New York. As soon as this chapter has begun active work, another will be opened in the New England and Middle West States, modeled after the California chapter. In this way the Association hopes to be of national service in the advancement of photography on educational lines, and it asks the sympathy of the public as well as that of every worker of the camera in America.

Among other of its plans are: honoring those who have given valued service to photography; the formation of a library; the establishment of a home headquarters; the distribution of knowledge tending toward the making of better catalogues; the art of hanging pictures so that their individual beauty may be enhanced; the application of the motion picture to pictorial expression; the recommendation of books on the development of the individual, as well as others relating to the study of contemporary arts, so that, through an acquaintance with all these, there may be brought to the student a new and an individual approach in his photographic work.

The Association holds monthly meetings at the National Arts Club, 119 East 19th Street, New York, where exhibitions and lectures are given. Admission is free. The Association now publishes its first annual “Pictorial Photography in America,” which comprises the work of important pictorialists in this country, whether or not members of the Association. And in following out so broad a plan the Association has demonstrated to its friends that its main interests lie in the presentation of fine work, little caring who the individual may be. As soon as the world has resumed its normal stride, the Association will extend invitations for an exhibition of foreign work to be shown in America. In turn, the Association will be glad to send an exhibition of American work abroad to those who desire to see, more intimately than we are able to do by the process of reproduction, what American pictorialists are doing. In another volume we hope to present the work of foreign pictorialists.

Plans are now being made whereby the original prints selected for this Annual will be exhibited, under the direction of the American Federation of Arts, in the galleries of many art museums throughout the country.

Herewith we list the names of the present officers and executive members of the Association, as well as those who are members of the Council having to do with pictorial activities in the different States. Membership in the Association is open to men and women of good character and ambitious intentions, including those who, though not photographers, are interested in the development of the art.

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

COUNCIL

Pictorial Photography in New Jersey

In New Jersey, as well as in other States, pictorial photography was at its lowest ebb during the period of the war. The official ban on the use of the camera in places that presented just the sort of material which stirs the enthusiasm of the amateur photographer tended so to dampen his ardor that his trusty “box” was left at home to accumulate dust.

But not for long, for a New Jersey cameraist, with the vision of a seer, saw an opportunity to use his beloved instrument in a far-reaching service. His enthusiasm was soon imparted to fellow members of the Newark Camera Club, and there quickly followed the birth of the Red Triangle Camera Club, affiliated with the local Y. M. C. A. Its object was pithily expressed in its slogan, “A picture of home to every soldier overseas”—at least to every Newark soldier in service.

While the members of the Camera Club were prompted solely by a desire to serve, it was not long before there came responses in the form of letters of gratitude from the soldier boys that heartened them to renewed activity. The written messages frequently attested that the pictures of the home folks sent by the Camera Club members were the only ones that had reached foreign shores.

As a stepping stone to something even greater, we have organized the Associated Camera Clubs of America, with a view to linking the activities of camera clubs and societies, the end to be sought being the creating of greater interest in exhibitions, [pg 9] and interchanges of lantern slides and prints. The prime object, of course, is to promote and cultivate the art-sense through the science of photography.

If a camera club does not exist in the community in which the reader resides, lend your services to the formation of one. The members of the Associated Camera Clubs of America stand ready to do their utmost to assist an infant organization on its way to success.

Pictorial Photograpny in Maine

Maine, the State of forest and lakes, does not hold the position in pictorial photography warranted by her natural beauties. It would not be unreasonable, considering the advantages of the land and the opportunities offered by the varying atmospheric conditions, particularly along the coast, to expect that there would be many pictorialists of high rank in the State; but it is a lamentable fact that there are not. After all, the making of pictures with a camera is to a large extent a matter of education and training—not so much in the way of overcoming the technical difficulties of the medium, though of course this must be learned too, but in such vital matters as composition, choice of subject matter, unity, simplicity, and the like. Then, given the vision, the pictorial photographer is born.

This preliminary training and the art education of the beginner can best be obtained in clubs; and in Maine the two centers of photographic activity are Portland and Bangor, in both of which cities are active camera clubs, each affiliated with the local art society and each holding annual exhibitions in the spring of the year, at which workers from all parts of the country show their pictures. During the war these clubs have been doing little more than marking time, but now that at last days of peace have come again, we feel that the future holds prospects of great promise to us. For one reason or another the men whose names were known ten or fifteen years ago seem to have dropped out and their places are being filled by new blood, men with high ideals and aspirations, who are not content merely with reproducing, by means of their cameras, pretty scenes and places, but who believe that photography is capable of much more—of showing not only the physical facts, but the very spirit of nature herself—a true impressionism; and it is the task of these men to place Maine in the position she should hold in pictorial work.

During the past year much has been accomplished by a very few men, and through these men Maine has been represented at all the largest and best salons, not only in this country and Canada, but also in England at the London Salon. Prints by the multiple gum process are favored by some of the Portland workers, but the use of this process as a medium of expression is limited to a few men, [pg 10] and the most of the large prints produced are enlargements on bromide paper, as is probably the case generally throughout the country. This is perhaps somewhat to be regretted, for although bromide paper is capable of producing very fine prints when the subject is exactly adapted to it, still it does not permit of the personal control afforded by some of the other processes, and of course this is a handicap to the pictorial worker.

As before stated, the pictorial output of the State during the past year has been limited to the work of a few men, but this condition is not going to continue for long. The clubs and societies are bending every effort toward the encouragement of the new workers, and already some very creditable work has been produced, and the coming year should see a worthy showing from Maine at all the salons.

Pictorial Photography in Massachusetts

In Massachusetts, as in other parts of the country, war-time activities interfered to a noticeable extent with the cause of pictorial photography. The interference was perhaps less marked than in some other sections, where more of the prominent workers were actively engaged at the front. The difficulty in securing materials, amounting now and then to utter impossibility, was, however, the same, and there was the same falling off in enthusiasm, due to the demands on one's heart and pocketbook from across the sea. In this crisis organized effort might have been especially helpful, but it is just in this respect that Massachusetts has always been weak. Her workers have been widely scattered from the Berkshires to the shore, and such local clubs as have here and there existed have not been deeply or permanently influential. In Boston there was the once famous Photo Clan, with Garo, Eicheim, and Schuman as its leading spirits, but that has long since ceased to be an active force. On the other hand, the Boston Young Men's Christian Union Camera Club and the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts have lately come into new prominence through their efforts to stimulate interest and afford frequent opportunities to view exhibitions of the best in photographic art. The former held, during the past winter, excellent one-man exhibits, in which work of such prominent pictorialists as John Paul Edwards, Dr. Rupert Lovejoy, Dwight A. Davis, Francis O. Libby, John H. Garo, Edward H. Weston, and Arthur Hammond was shown.

But, in spite of these various influences, the workers of Massachusetts for the most part pursue solitary ways, with little enough—all too little, some would say—of the advantages that come from intimate association. There is, however, another side of the shield. It is at least questionable whether such strongly marked personality as appears in the work of Seeley, Garo, Davis, Hammond, Eicheim, [pg 11] Buttler, the Allen sisters, and a dozen others who might be mentioned, would be possible if the workers of this section were under the closely dominating influence of a centralized group, itself dominated by a single individual of exceptional powers. Such a state of affairs has sometimes been observed in other parts of the country, and the results have not always been advantageous to the interests of the individual workers. Under such conditions as exist in Massachusetts, the Pictorial Photographers of America has come as a boon, since it affords just the kind of stimulus most needed. Massachusetts has been swift to avail herself of the advantages thus offered. At the recent exhibition of the work of New England and New Jersey pictorialists, held in New York, Massachusetts was represented by 16 out of a total of 27 exhibitors, with 64 out of a total of 107 prints—a showing decidedly creditable to the old Bay State.

Pictorial Photograpky in Maryland

The progress of pictorial photography in Maryland is to be ascertained by an examination of the progress of the amateur in Baltimore, for aside from the local exhibitions we have no record of anything done in the State. While this condition is regrettable and hard to comprehend in an art-loving center of such population, there is none the less an improvement over former times.

The shops and the “finishers” have prospered, while the club—the old organization in which the reason of being has been lost in a maze of constitutional amendments, by-laws, and such like red tape—has declined in influence and popularity. In the world at large, pictorial photography has grown amazingly. This has led to a more pronounced line of demarkation between the dilettante and the intelligent worker of appreciation, with the balance of influence inclining strongly to the latter. In Maryland there has been an upheaval, a photographic revolution, so to speak, and out of the wreckage has sprung the Photographic Guild of Baltimore, which has done more to put Maryland photographically to the fore in its five years of activity than had been done in all the years previous. It was due almost entirely to Guilders that Maryland stood fourth at the recent Pittsburgh Salon. Two prerequisites to membership in the Guild are ability in keeping with the highest standards and productiveness, as a consequence of which it has only six members, who may be said to comprise the representative pictorialists of the State.

For the past four years there has been an annual exhibition under the auspices of the Guild at the Peabody Gallery, each well attended by the art-loving public, with marked enthusiasm for what is being done with the process. A feature of the Guild exhibitions, beginning with the 1919 portfolio recently hung, is the invited work of out-of-town amateurs, which is giving Baltimoreans a wider and better [pg 12] knowledge. While this exhibition has not assumed salon proportions, it will in a measure bring the salons to Baltimore if help in the way of prints from outside is forthcoming, as we hope and believe will be the case.

On the whole, it may be truly said that the flexibility and responsiveness of the photographic process have been sufficiently demonstrated to fix it firmly among the art mediums.

Middle West Activities and the Pittsburgh Salon

Any article describing the activity in pictorial photography in the United States since 1914 must include a history of the work of the Pittsburgh Salon, and that has been very thoroughly covered in magazine articles immediately succeeding the close of each salon.

At the outbreak of the war, the thoughts and energies of many of our foremost workers were directed toward other fields, and those who still practiced the work for the art side of it did so under difficulties.

The governmental restrictions placed on the use of the camera in ports and about all public buildings, and in many sections of nearly every city, naturally had a tendency to discourage workers, but in spite of all the obstacles in the path of the art photographer the years have not been barren.

Some of the older societies have all but ceased to exist, if one can judge by their contributions to the salons.

Each year has witnessed new names among the exhibitors at Pittsburgh, and to an already formidable list there are annually added more than enough names to fill the vacancies caused by the dropping of former members who have failed to retain their membership due to non-compliance with the rules which automatically eliminate inactives.

After six years of unprecedented success it may safely be said that the Pittsburgh Salon has become a permanent fixture in the world of photographic art and has unquestionably rendered a most valuable service in keeping alive the exhibition spirit.

Mention should also be made of the good work done by the Chicago Photo-Fellows, the Buffalo Camera Club, the Photographic Guild of Baltimore, and the Photographic Section of the Pittsburgh Academy of Fine Arts, each one composed of enthusiasts, who loyally support the American and London Salons as well as being active workers in the Pictorial Photographers of America.

These societies have been continually engaged in the promotion of inter-club exhibitions as well as in encouraging the circulation of work of individual members.

As an educational feature the club interchange has no equal.

[pg 13]Pictorial Photography in the Far West

The progress of pictorial photography in the Far West can be aptly compared with the settlement and growth of this big new country itself. We have had our pictorial pioneers, as it were—our hard-working, enthusiastic, rather crude first settlers in the art; now we have come to the stage of permanent abode, with traditions, albeit young, great enthusiasm, definite ideals, and ambitious hopes for the future.

The one great asset in the upbuilding of the West has been boundless enthusiasm. This characteristic trait dominates the very soul of the Western pictorialist. In it lies his greatest hope for the future progress in his chosen field of art.

It is this live energy and enthusiasm which brings him out afield even before break of day, which leads him over hill and dale, mountain and valley, in his insatiable quest for the pictorial. Miles are as nothing; hunger stays him not; nor rests he at night until his potential treasures are developed and their beauties appraised.

The purpose of this preliminary psychologic analysis is to explain the militant attitude of the Western pictorialist in his pursuit of the art of the camera. His extremely prolific production, manifesting itself in liberal contributions to the salons and exhibitions of the world photographic, rises not from vanity but from super-enthusiasm—from the great joy he derives in making his picture, from the creation of the beautiful, and from the playing of the game as it is best played.

Without losing a whit of the steady enthusiasm which has brought it to its present encouraging stage, Western pictorial photography is, nevertheless, settling down to a more staid and intellectual plane of progress.

The broad average of quality of work is steadily improving. Better standards have been established. The workers are “finding” themselves. Enthusiasm is being beneficently tempered by increased technical skill, and more particularly by the intellectual development of the art side of the work.

And so the future of pictorial photography in the Far West looks exceedingly bright. The salon workers of the past five or ten years are with few exceptions as keen as ever for their art, and a very talented and numerous lot of new workers are coming to the front.

The center, in fact the stronghold, of Western pictorial photography is undoubtedly California. All forms of art seem to flourish mightily in this genial clime of wondrous, colorful beauty. A land of smiling sunshine, of lofty snow-capped peaks, of weird trees, of golden poppy-covered slopes, of sparkling seas—it is small wonder that the young art of the camera should thrive so vigorously there.

There are several active foci of pictorial interest in the State. The most active and most promising of these centers is the Camera Pictorialists of Los Angeles. [pg 14] This club, as we may call it, has a membership of fourteen under the directorship of Louis Fleckenstein. Every member is an active worker of ability and promise. This group has made an imposing representation in nearly every photographic salon of recent years.

They are sponsors for the International Photographic Salon held annually in the municipal art gallery of Los Angeles. This exhibition, with two years of success behind it, must be rated as the premier event of its kind in the West, and, in the quality of its offerings, second to none on the continent.

While this is the only prominent group in California organized for strictly pictorial work, there are a great many independent workers widely scattered about the State. San Francisco and the bay region can claim a score or more whose achievements have been notable.

Oregon has many enthusiastic workers and a strong club in Portland. Washington likewise has many camera artists of talent. Both these States have an untold wealth of pictorial material and many keen pictorialists. All they lack is an active leader or two to bring them to the rank they should hold in the photographic world.

In Salt Lake City we find an active, enthusiastic and very promising group of workers under the able leadership of Thomas O. Sheckell. Through the medium of an extensive series of one-man exhibitions they have brought before the art-loving public of their city the best work of a large number of our leading pictorialists.

One of the most interesting and auspicious developments of the year has been the recent formation of the Pacific Coast Chapter of the Pictorial Photographers of America.

For very logical reasons the chief activities of the parent body of the Pictorial Photographers of America have been centered in the City of New York. An earnest desire to enjoy like activities right at home while still sharing the privileges of direct affiliation with our fellows of the Pictorial Photographers of America led to the formation of the Pacific Coast Chapter. The idea is still young, but the success of the chapter is definitely assured by the strong character of the membership already secured. It is the purpose of the chapter to uphold strongly the purposes and ideals of its parent body and to work continuously for the advancement of pictorial photography in the West. A number of interesting exhibitions are scheduled for the near future, the most important of these being the “All Western” exhibition, which is planned for the fall and winter of 1919-20. The aim is to include the best pictorial photography of the West. It will be shown first in New York by the Pictorial Photographers of America and then routed through some of the more representative clubs of the East and Middle West.

Illustrations

[pg 15]

By W. A. Alcock, Brooklyn, N.Y.

By Elizabeth R. Allen, Moorestown, N.J.

By George M. Allen, Portland, Ore.

By Fred R. Archer, Los Angeles, Cal.

By Laura Adams Armer, Berkeley, Cal.

By Jessie Tarbox Beals, New York

By David W. Bonnar, Buffalo, N. Y.

By Will D. Brodhun, Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

By Gertrude L. Brown, Evanston, Ill.

By John C. Burkhardt, Portland, Ore.

By Dr. A. D. Chaffee, New York

By Arthur D. Chapman, New York

By Alvin Langdon Colburn, New York

By Alfred Cohn, Brooklyn, N. Y.

By James Copella, New York

By C. P. Crowther, Kobe, Japan

By Helen W. Drew, Montclair, N. J.

By Jerry D. Drew, Montclair, N. J.

By Dwight A. Davis, Worcester, Mass.

By Edward R. Dickson, New York City

By De Meyer, New York

By E. G. Dunning, New York

By Vernon Everett Duroc, Brooklyn, N. Y.

By William B. Dyer, Portland, Ore.

By John Paul Edwards, Sacramento, Cal.

By Adelaide Wallach Ehrich, New York

By Eleanor C. Erving, Albany, N. Y.

By W. H. Evans, Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

By O. E. Fischer, M. D., Detroit, Mich.

By Louis Fleckenstein, Los Angeles, Cal.

By Frederick Frittita, Baltimore, Md.

By John Wallace Gillies, New York

By Laura Gilpin, Colorado Springs, Col.

By Forman Hanna, Globe, Ariz.

By G. H. S. Harding, Berkeley, Cal.

By Edward Heim, New York

By G. W. Harting, New York

By Antoinette B. Hervey, New York

By George Henry High, Chicago, Ill.

By L. Willis Hoops, New York

By G. B. Hollister, Corning, N. Y.

By Bernard S. Horne, Princeton, N. J.

By Blanche C. Hungerford (Mrs. Latimer), High Bridge, N. J.

By Dr. Charles H. Jaeger, New York

By Doris U. Jaeger, New York

By Arthur F. Kales, Los Angeles, Cal.

By Gertrude Kasebier, New York

By William Kriebel, Philadelphia, Pa.

By W. R. Latimer, High Bridge, N. J.

By Sophie L. Lauffer, Brooklyn, N. Y.

By George P. Lester, Bloomfield, N. J.

By Francis Orville Libby, Portland, Me.

By Edwin Loker, St. Louis, Mo.

By Dr. William F. Makk, Los Angeles, Cal.

By Margrethe Mather, Los Angeles, Cal.

By Oscar Maurer, Los Angeles, Cal.

By Holmes I. Mettee, Baltimore, Md.

By J. George Midgley, Salt Lake City, Utah

By H. W. Minns, Akron, Ohio

By H. Remick Neeson, Baltimore, Md.

By Henry Hoyt Moore, Brooklyn, N. Y.

By J. W. Newton, Columbus, Ohio

By Imogen Cunningham Partridge, San Francisco, Cal.

By G. Houson Payne, Jr., Baltimore, Md.

By Margaret Rhodes Peattie, Chicago, Ill.

By Leo Pokras, Brooklyn, N. Y.

By W. H. Porterfield, Buffalo, N. Y.

By E. M. Pratt, Tracy, Cal.

By Mrs. William H. Rau, Philadelphia, Pa.

By Jane Reece, Dayton, Ohio

By O. C. Reiter, Pittsburgh, Pa.

By L. M. A. Roy, La Crosse, Wis.

By Dr. D. J. Ruzicka, New York

By J. G. Sarvent, Kansas City, Mo.

By Otto C. Shulte, San Franciso, Cal.

By David J. Sheahan, Los Angeles, Cal.

By Thomas O. Sheckell, Salt Lake City, Utah

By William Gordon Shields, New York

By Mrs. Sterling Smith, San Diego, Cal.

By E. Radiker Standcliff, Elmira, N. Y.

By W. H. Stephens, San Franciso, Cal.

By Ford Sterling, Los Angeles, Cal.

By John H. Stocksdale, Baltimore, Md.

By M. Sugimoto, New York

By Elizabeth Talcott, Elmwood, Conn.

By William H. Thompson, Hartford, Conn.

By Lieut. Edward Larocque Tinker, U. S. N., New York

By Charles Vandervelde, Grand Rapids, Mich.

By the late Lieut. Luke R. Vickers, Church Creek, Md.

By Will H. Walker, Portland, Ore.

By Mabel Watson, Pasadena, Cal.

By Delight Weston, Blue Hill, Me.

By Edward Weston, Glendale, Cal.

By Leonard Westphalen, Chicago, Ill.

By Clarence H. White, New York

By Cornelia F. White, New York

By Hazel Jane Wiegner, Philadelphia, Pa.

By Edith R. Wilson, Mount Vernon, N. Y.

By Mildred R. Wilson, Orange, N. J.

By N. S. Wooldridge, Pittsburgh, Pa.

The following is a partial list of photographic organizations in America which are encouraging pictorial Photography

The reproductions in this Annual were selected from a group of nearly 1100 photographs. Of the 100 artists whose prints are now reproduced:

36 are new workers. 16 were unknown to the judges. 32 are workers of recent years. 16 are old workers.

A further computation shows that 56 are members of the Association, while 44 are non-members.

[pg 118]