New York

1922

Illustrations

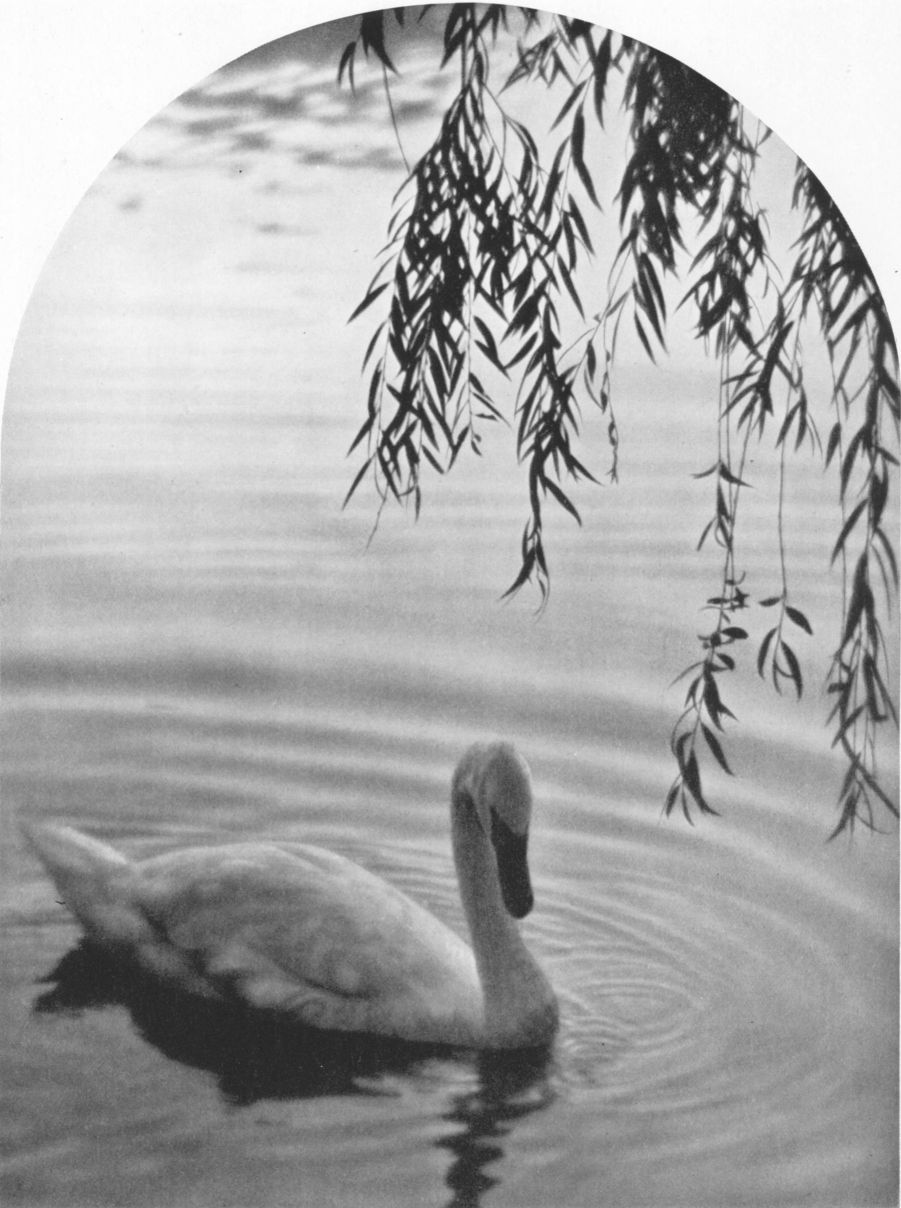

- A DECORATIVE PANELBy Thos. O. Sheckell, Salt Lake City, Utah

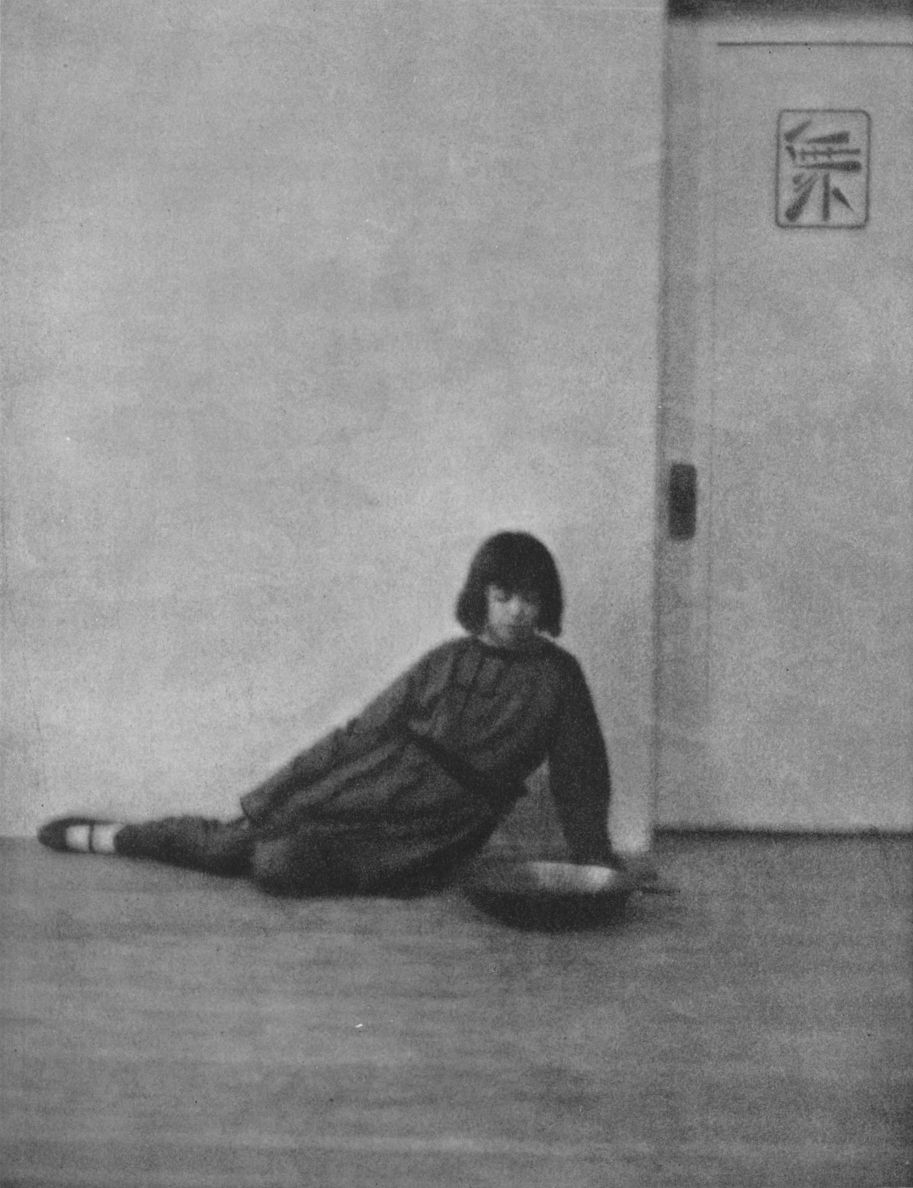

- IN A DANCER'S STUDIOBy Wayne Albee, Seattle, Washington

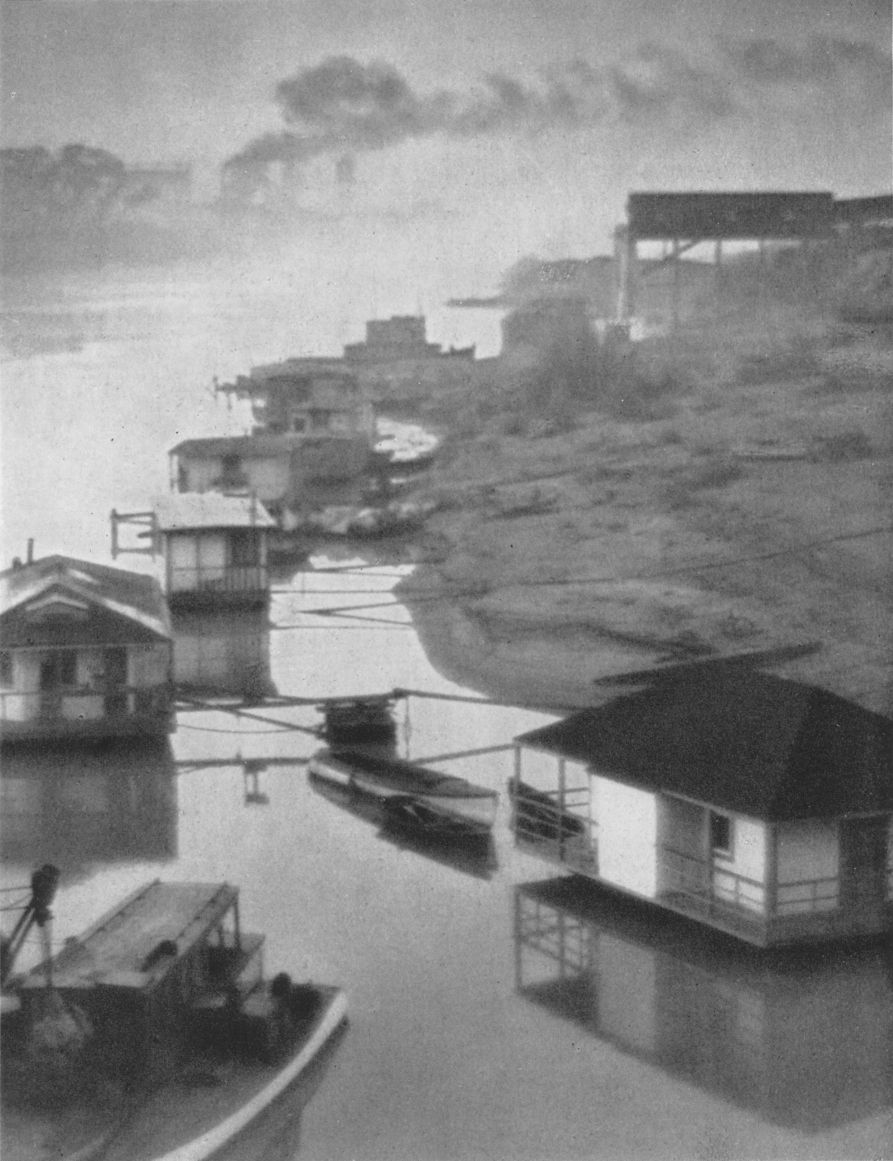

- HOUSE-BOATSBy Ernest M. Pratt, Los Angeles, Calif.

- MAY I COME IN?By Robert R. McGeorge, Buffalo, N. Y.

- THE DISTANT SAILBy William Gordon Shields, New York City

- GATEWAY, DINANBy Dr. Chas. H. Jaeger, New York City

- SILHOUETTES—EGYPTBy Julia Marshall, Duluth, Minn.

- MOUNT EVERETTBy Robert B. Montgomery, Brooklyn, N. Y.

- THE BACK FENCEBy C. R. Herzler, New York City

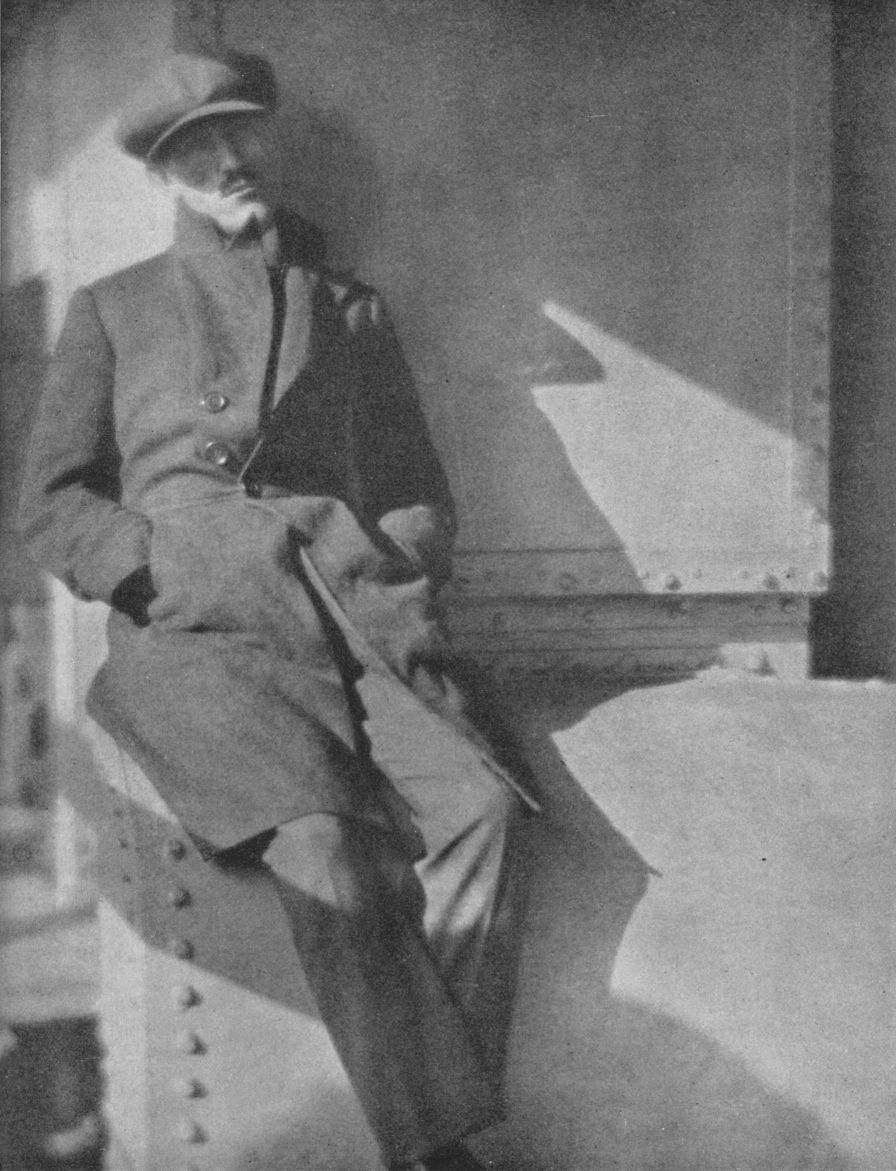

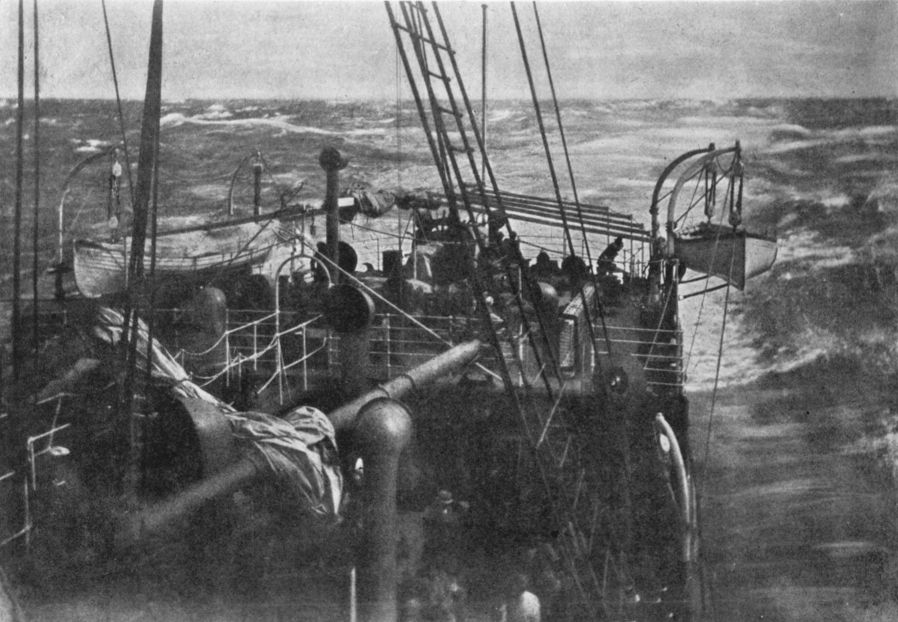

- ON DECK OF THE METAGAMABy Johan Hagemeyer, San Francisco, Calif.

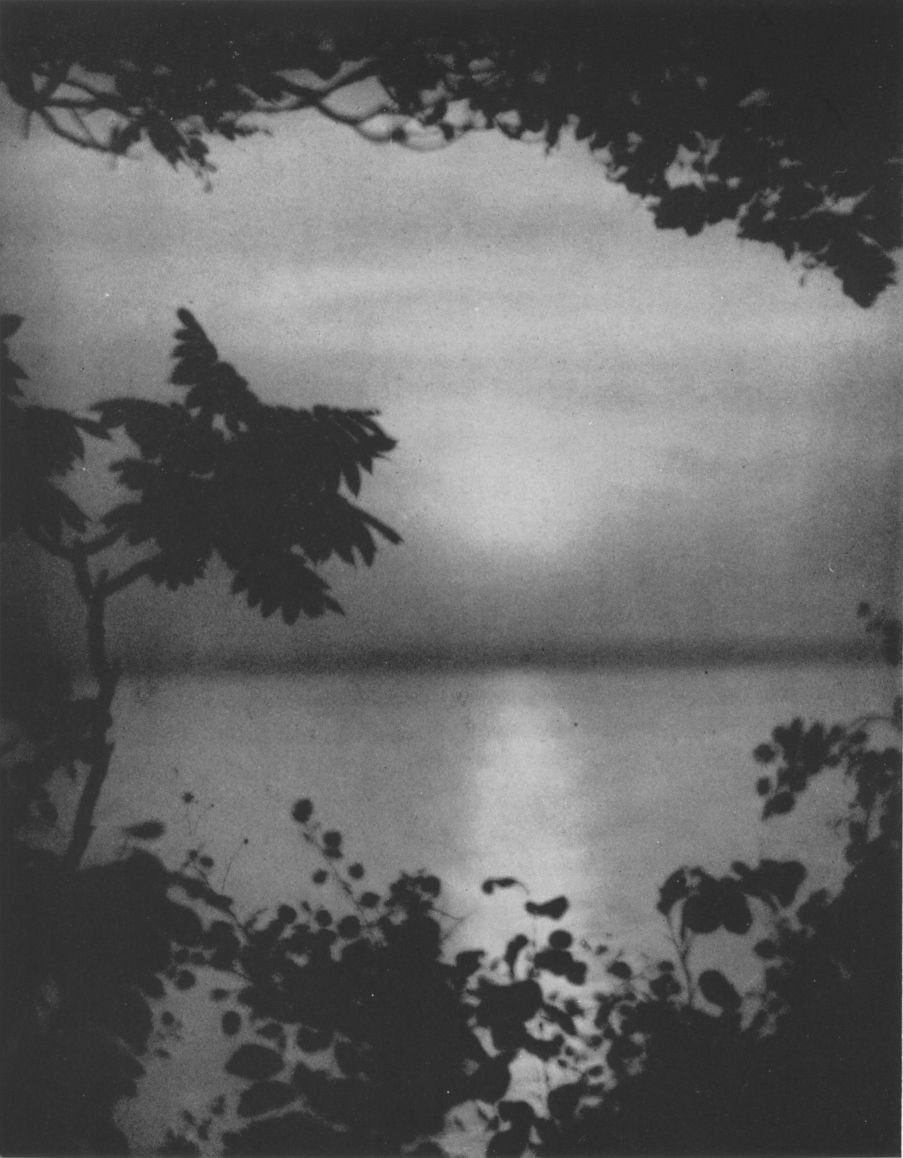

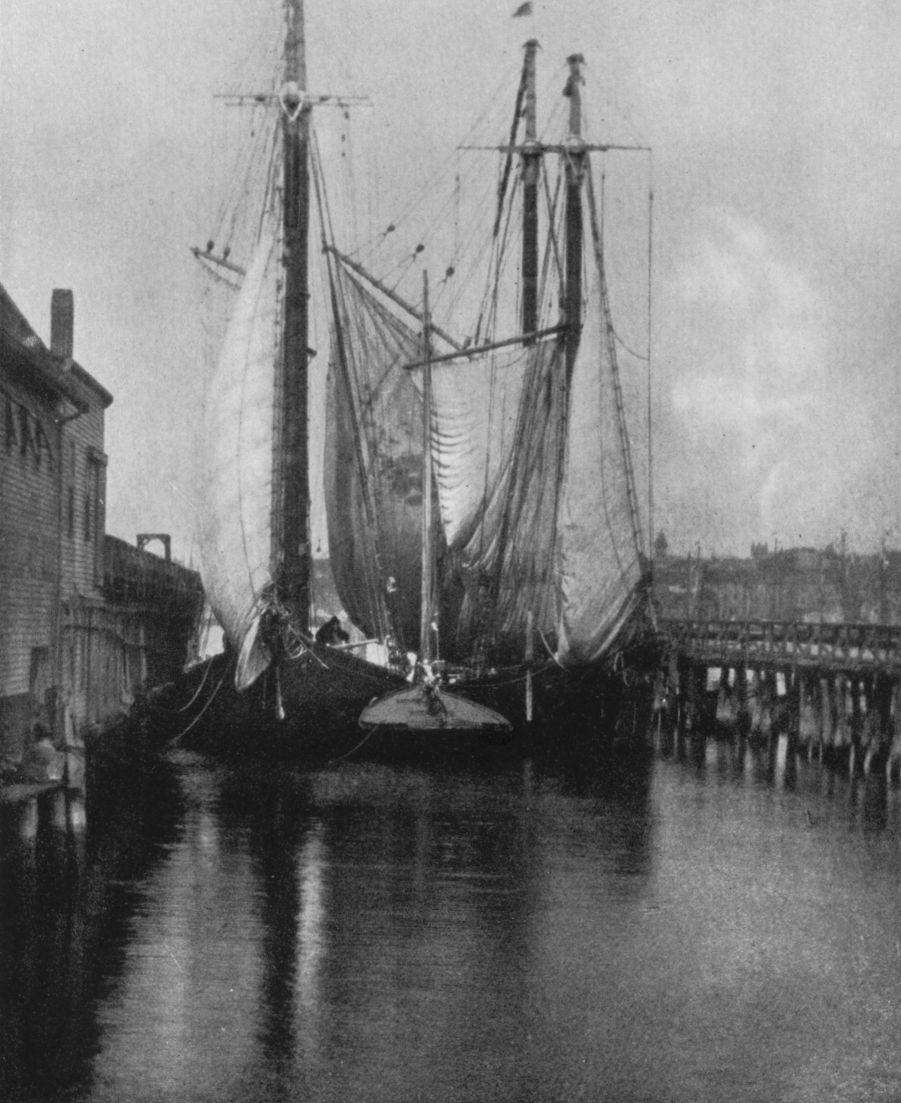

- TIDEWATERBy Amelia H. McLean, Bronxville, N. Y.

- STREET VENDORS—ROME, ITALYBy H. A. Latimer, Boston, Mass.

- SUMMERTIMEBy Paul Wierum, Chicago, Ill.

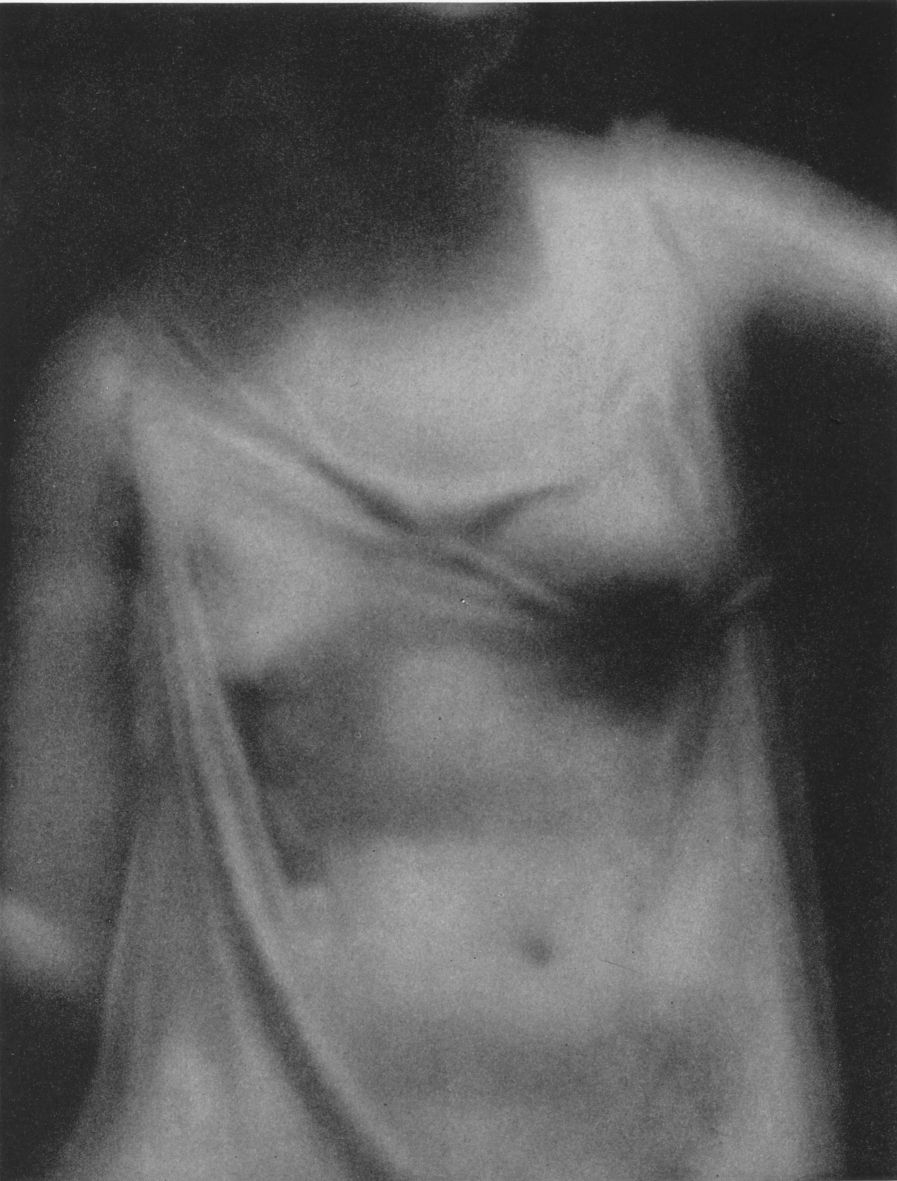

- TORSO OF A DANCERBy Arnold Genthe, New York City

- A MAINE FISHING VILLAGEBy Eugene P. Henry, Brooklyn, N. Y.

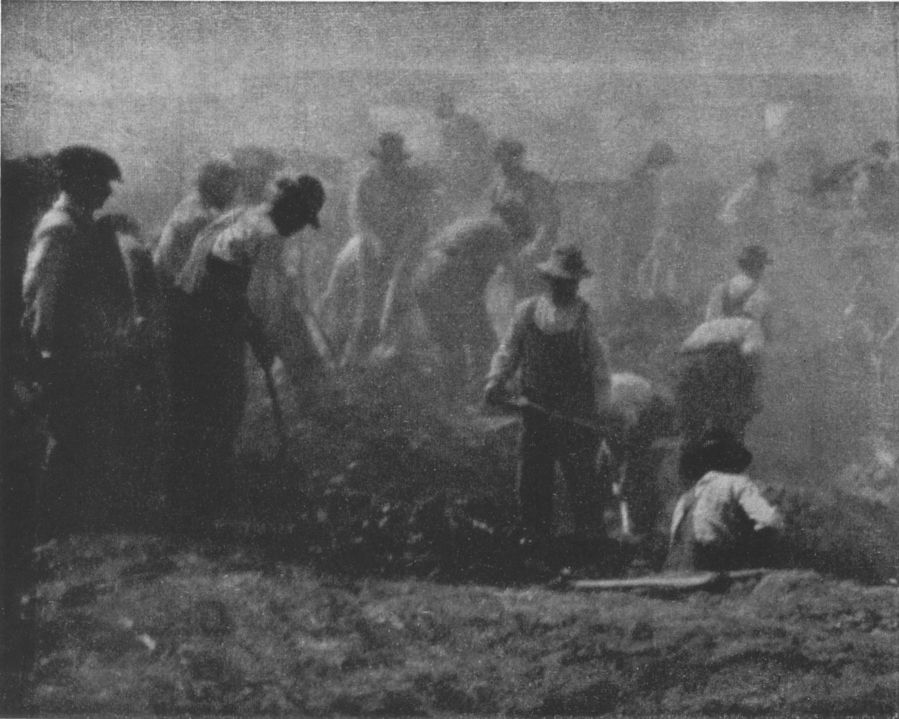

- SMOKE EATERSBy W. H. Zerbe, Richmond Hill, N. Y.

- PUEBLO DWELLINGBy Ernest Williams, Los Angeles, Calif.

- IN THE BERKSHIRESBy William Elbert Macnaughton, New York City

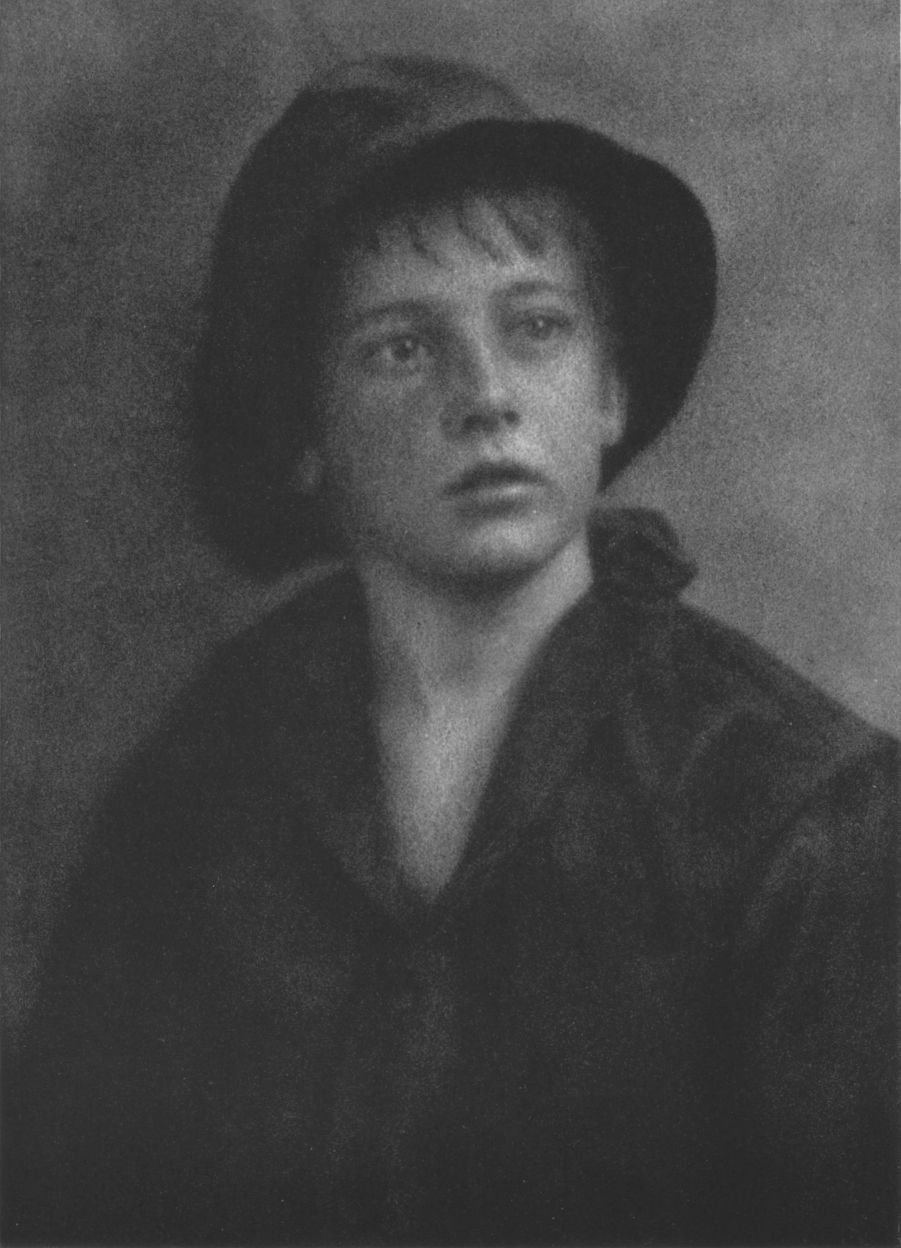

- BEPPYBy Helen W. Drew, Montclair, N. J.

- EMPTIESBy K. B. Lambert, Glen Ridge, N. J.

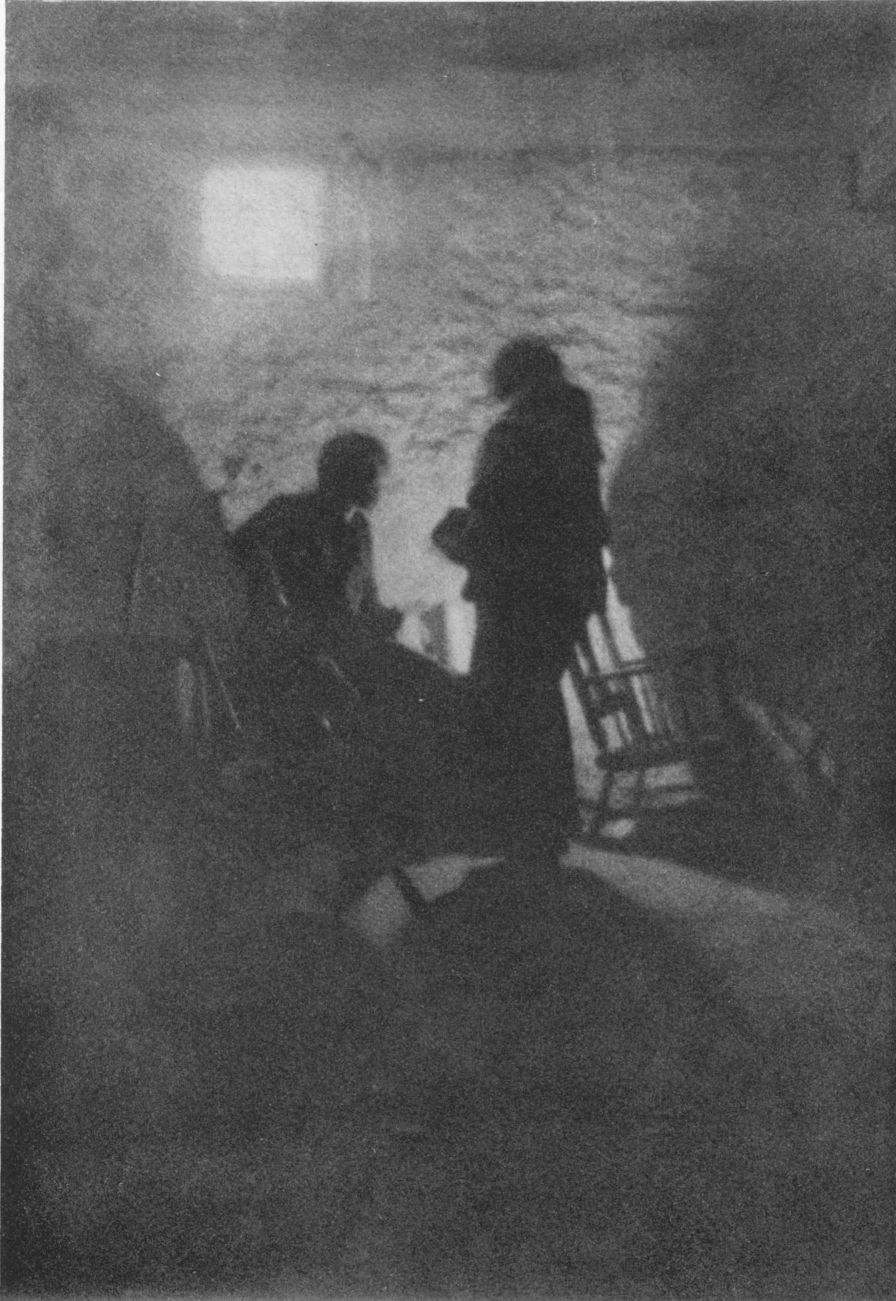

- THE WOODCHOPPER'S WOMANBy Harry C. Phipps, Chicago, Ill.

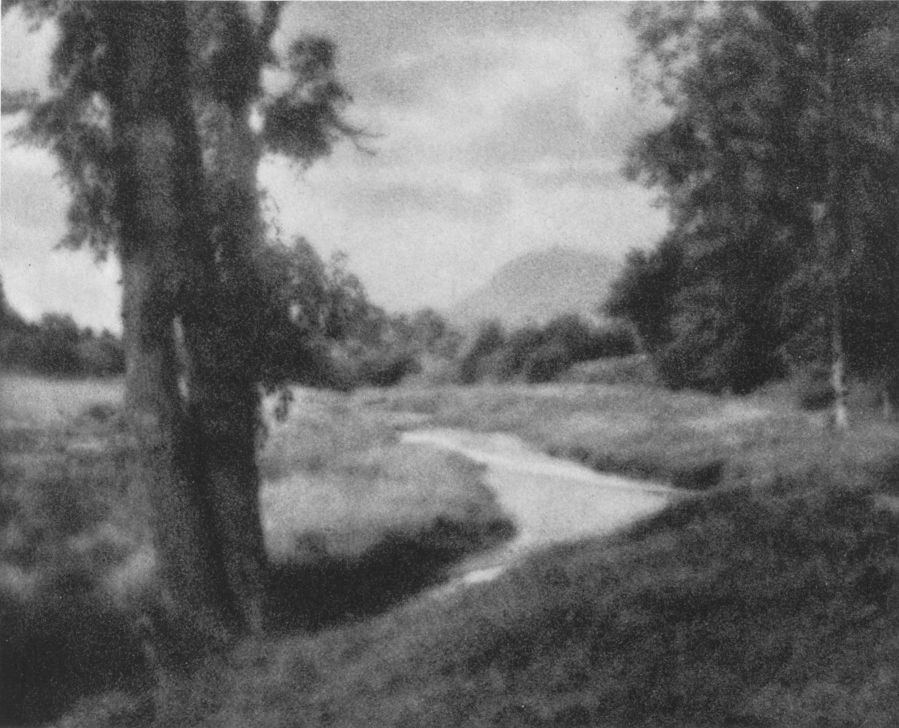

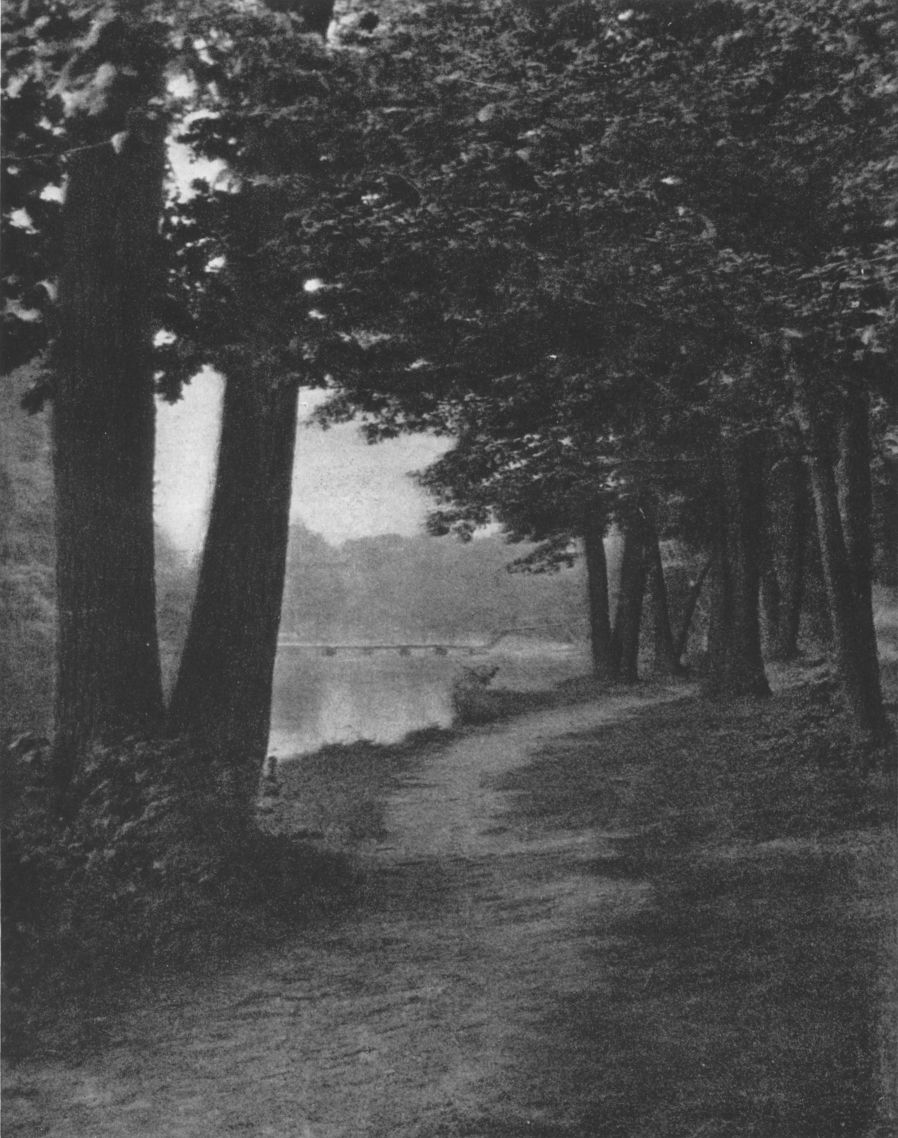

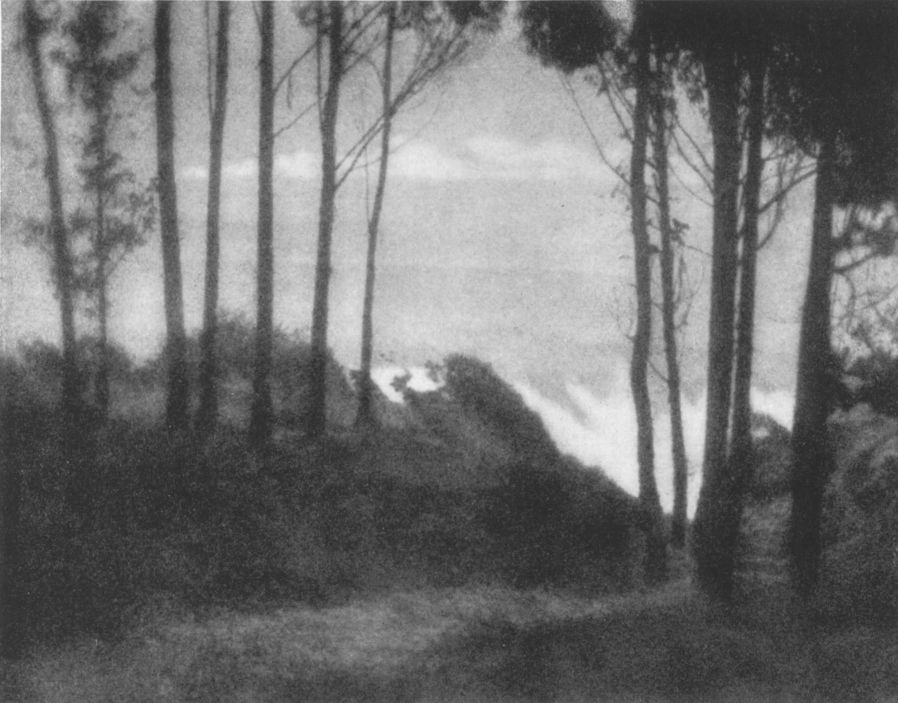

- THE DES PLAINES TRAILBy E. E. Gray, Chicago, Ill.

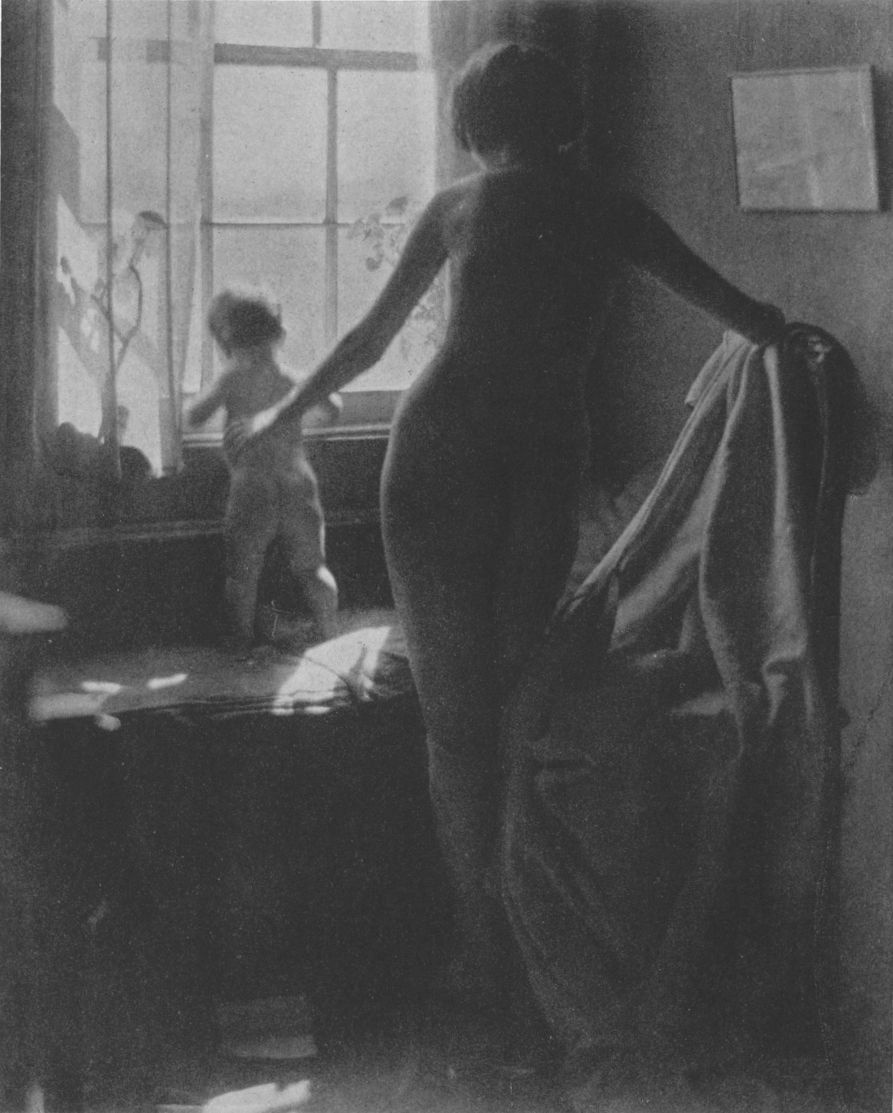

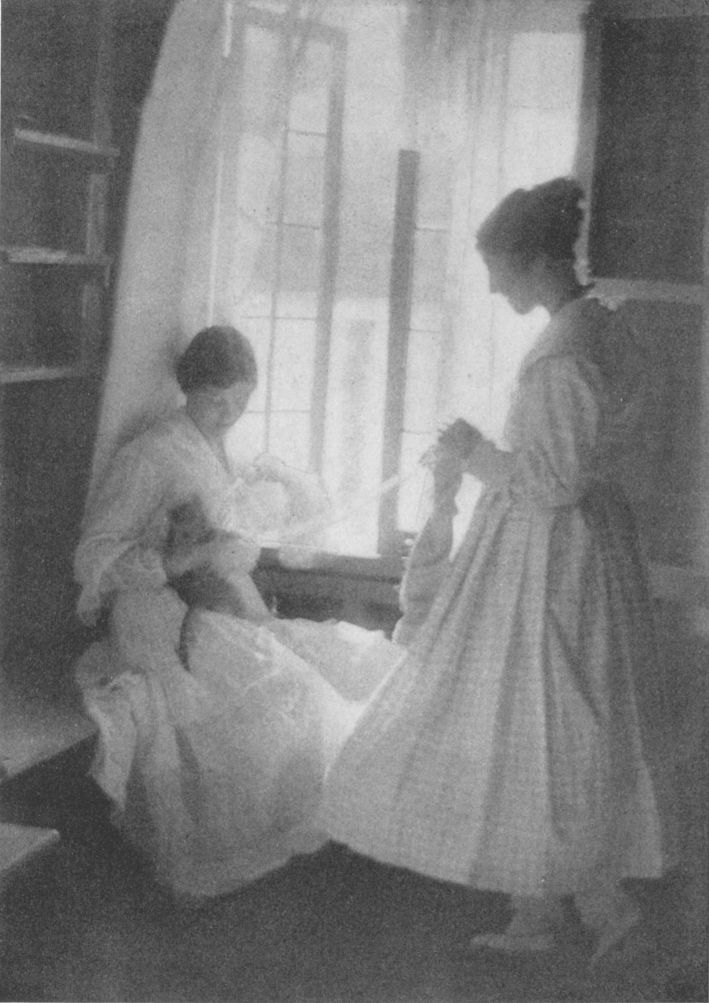

- MOTHER AND CHILDBy Clarence H. White, New York City

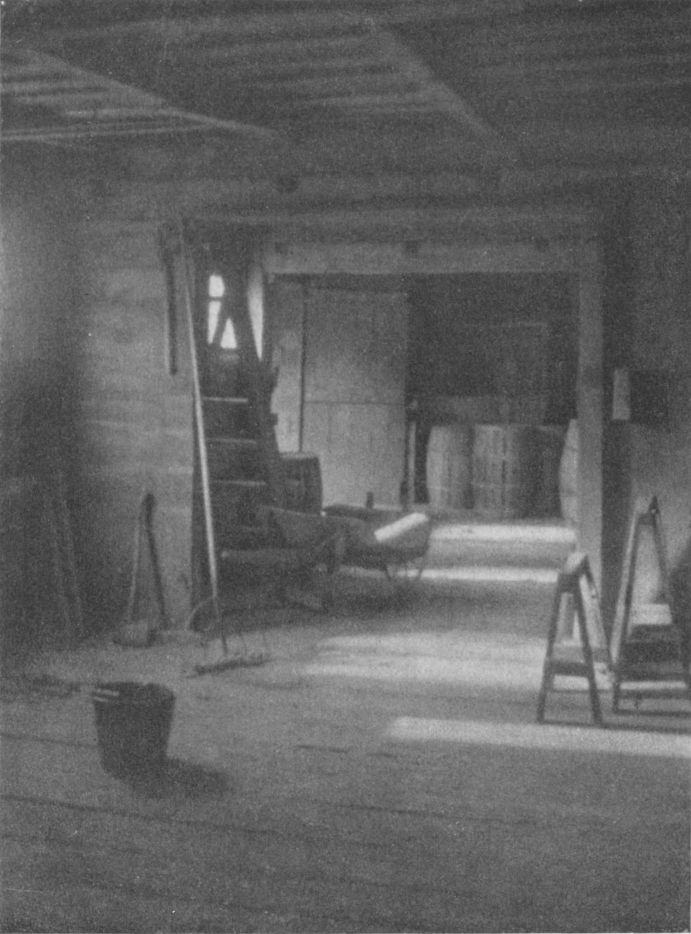

- YE OLD BARNBy Olive Garrison, Yonkers, N. Y.

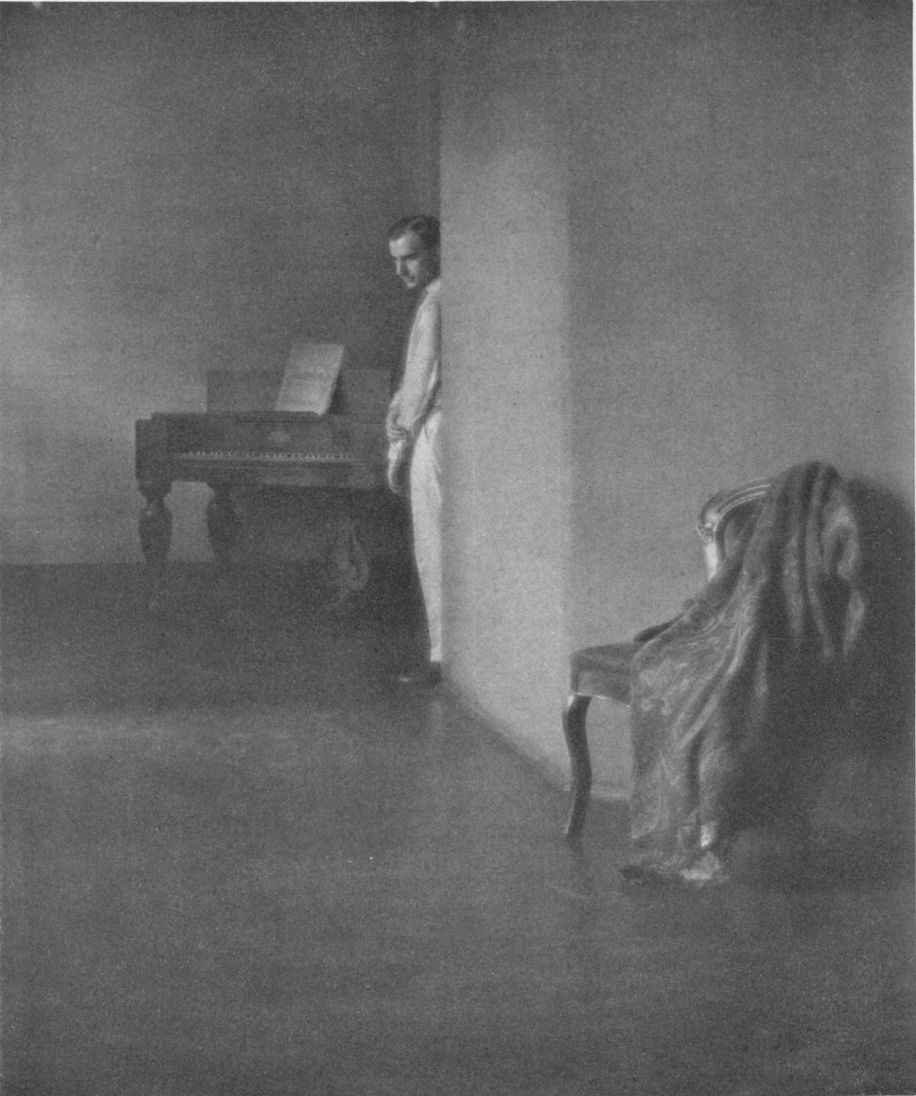

- INTERIORBy Jane Reece, Dayton, Ohio

- PENNSYLVANIA STATIONBy Dr. D. J. Ruzicka, New York City

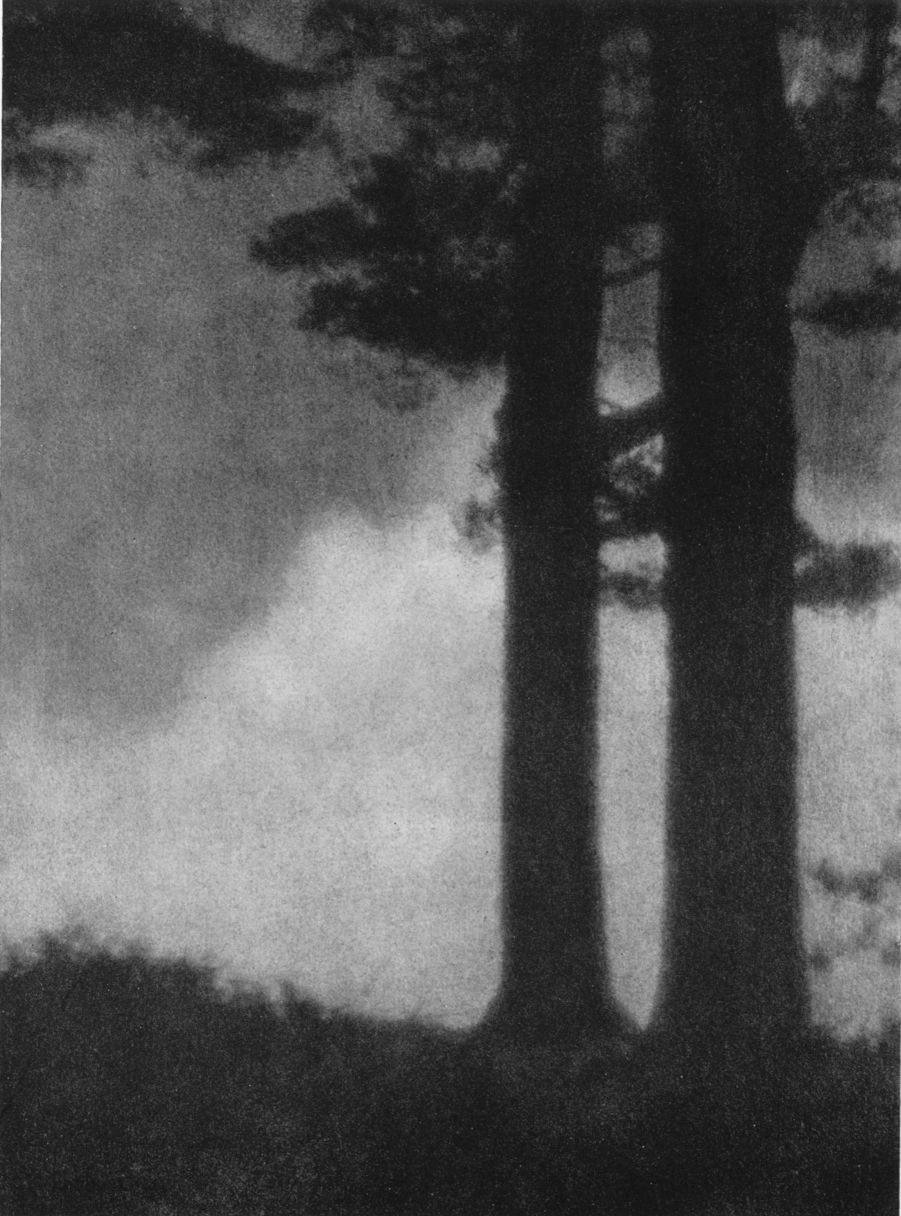

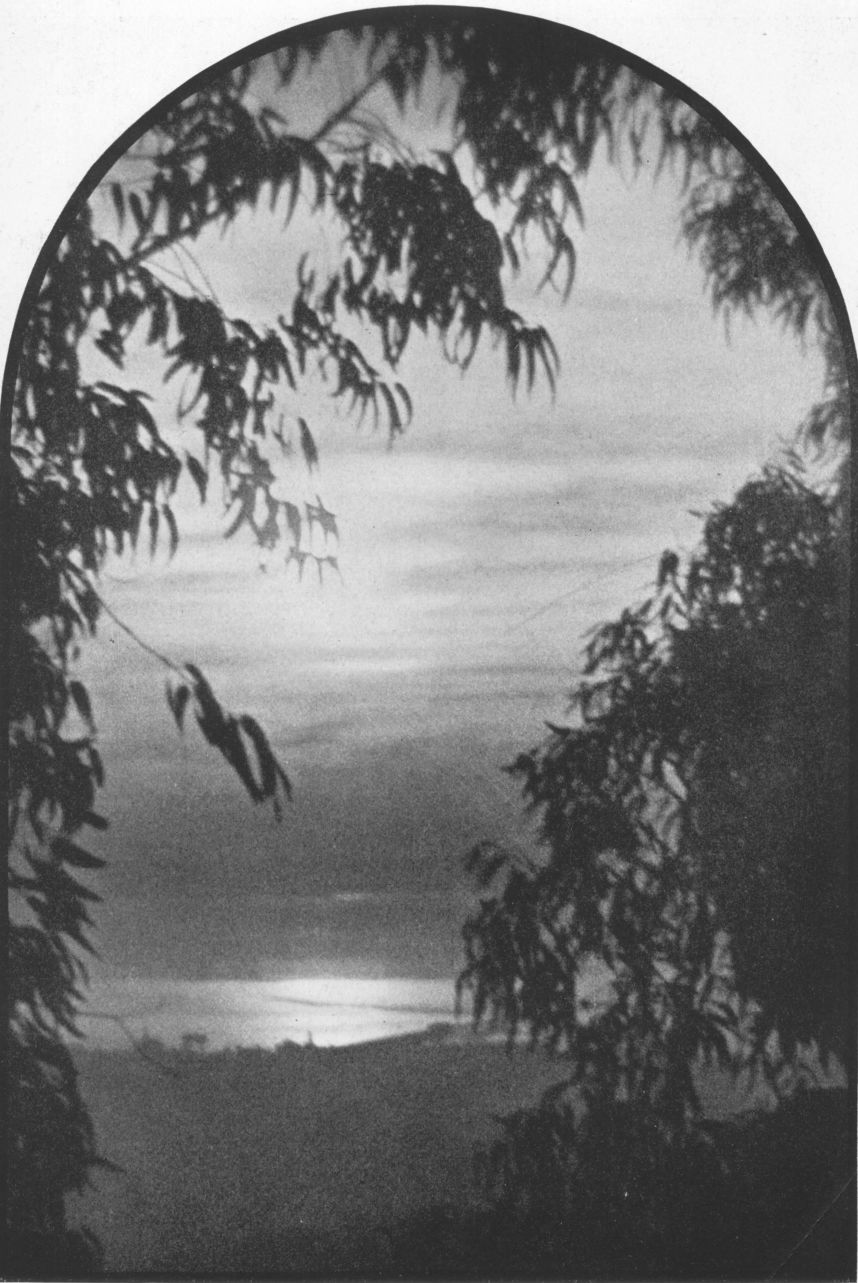

- CLOUDS OF MORNINGBy Francis O. Libby, F.R.P.S., Portland, Me.

- THE CANYONBy Jerry D. Drew, Montclair, N. J.

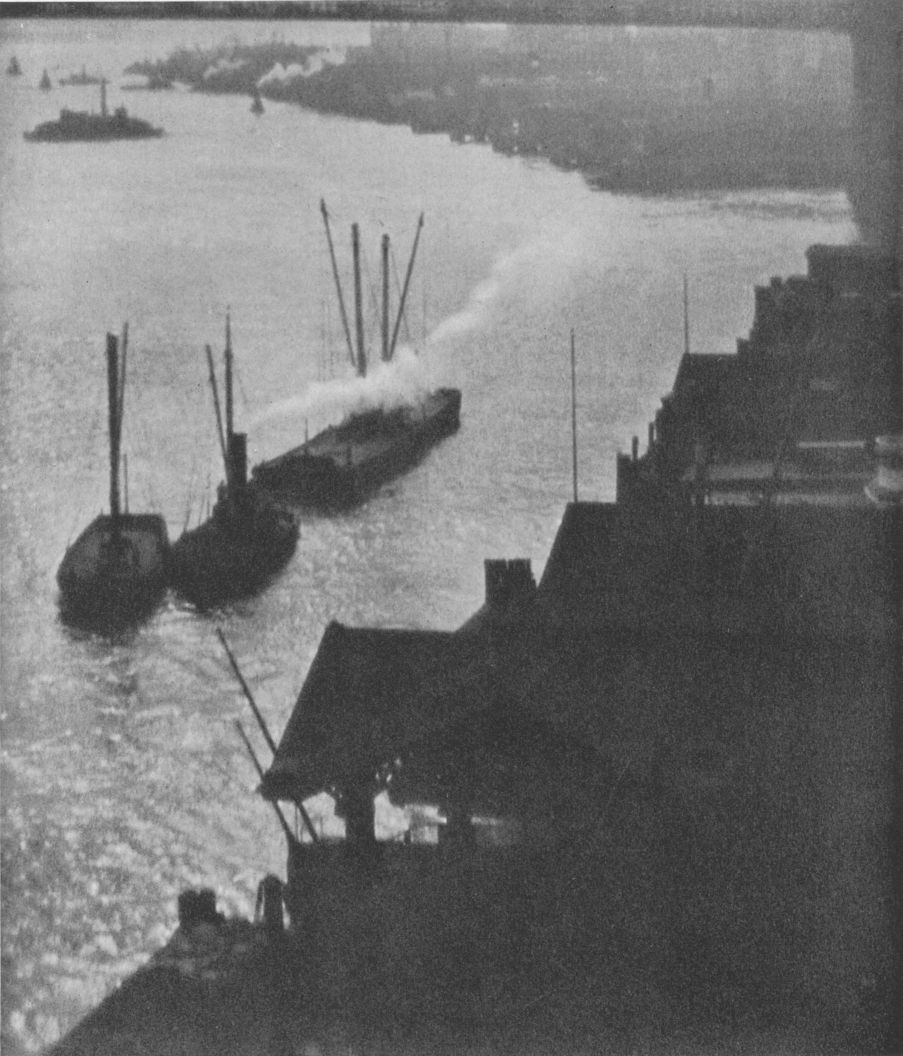

- THE EAST RIVERBy John Paul Edwards, San Francisco, Calif.

- THE TRAIN SHED—PITTSBURGHBy W. W. Zieg, Pittsburgh, Pa.

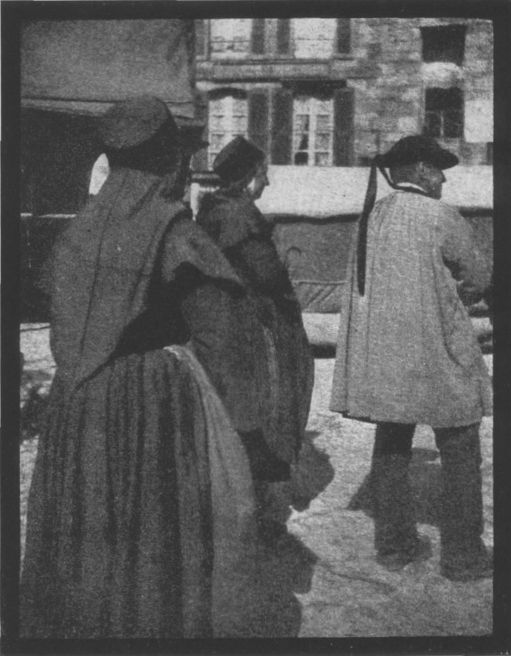

- ODD MOMENTS IN BRITTANYBy George Henry High, Chicago, Ill.

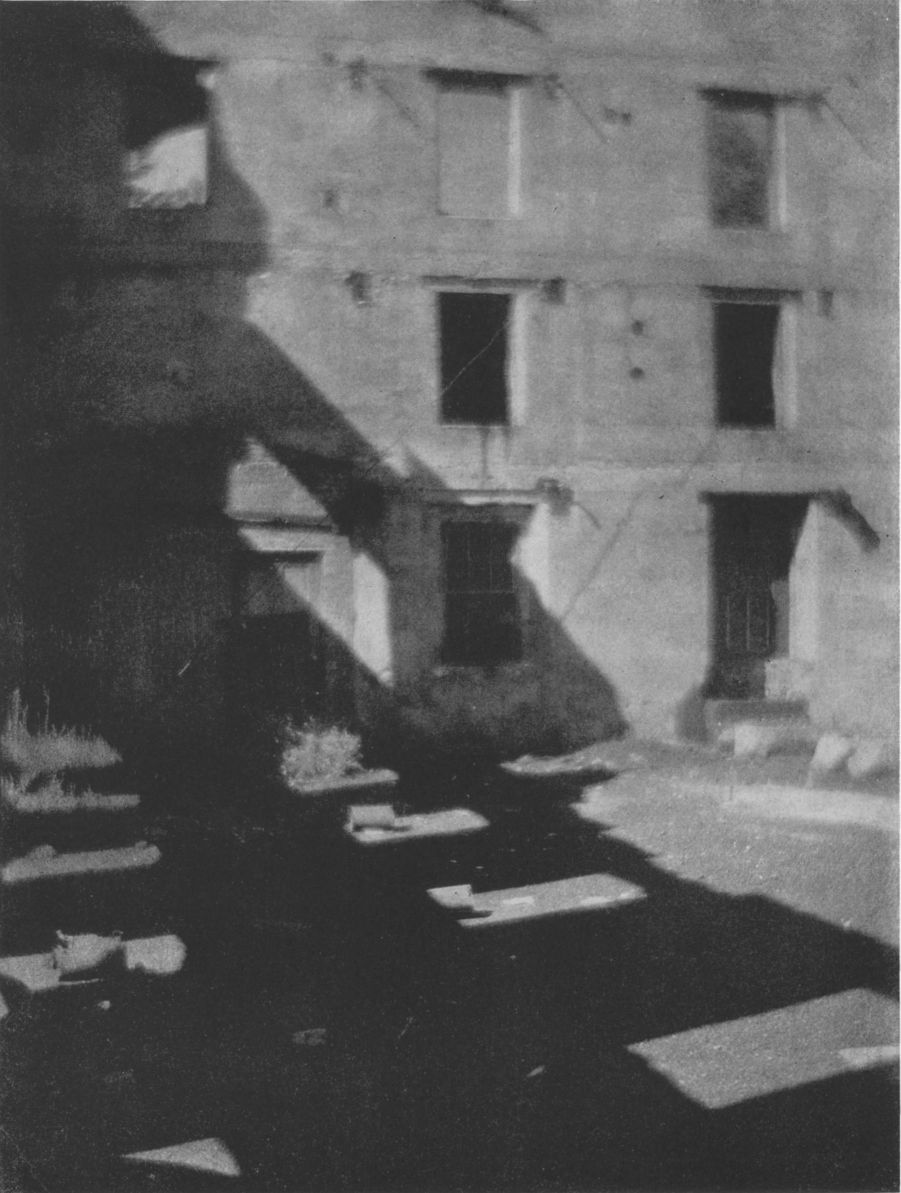

- UZERCHES: "IL FAIT UN BON SOLEIL"By Dr. A. D. Chaffee, New York City

- A MISTY MORNINGBy N. S. Wooldridge, Pittsburgh, Pa.

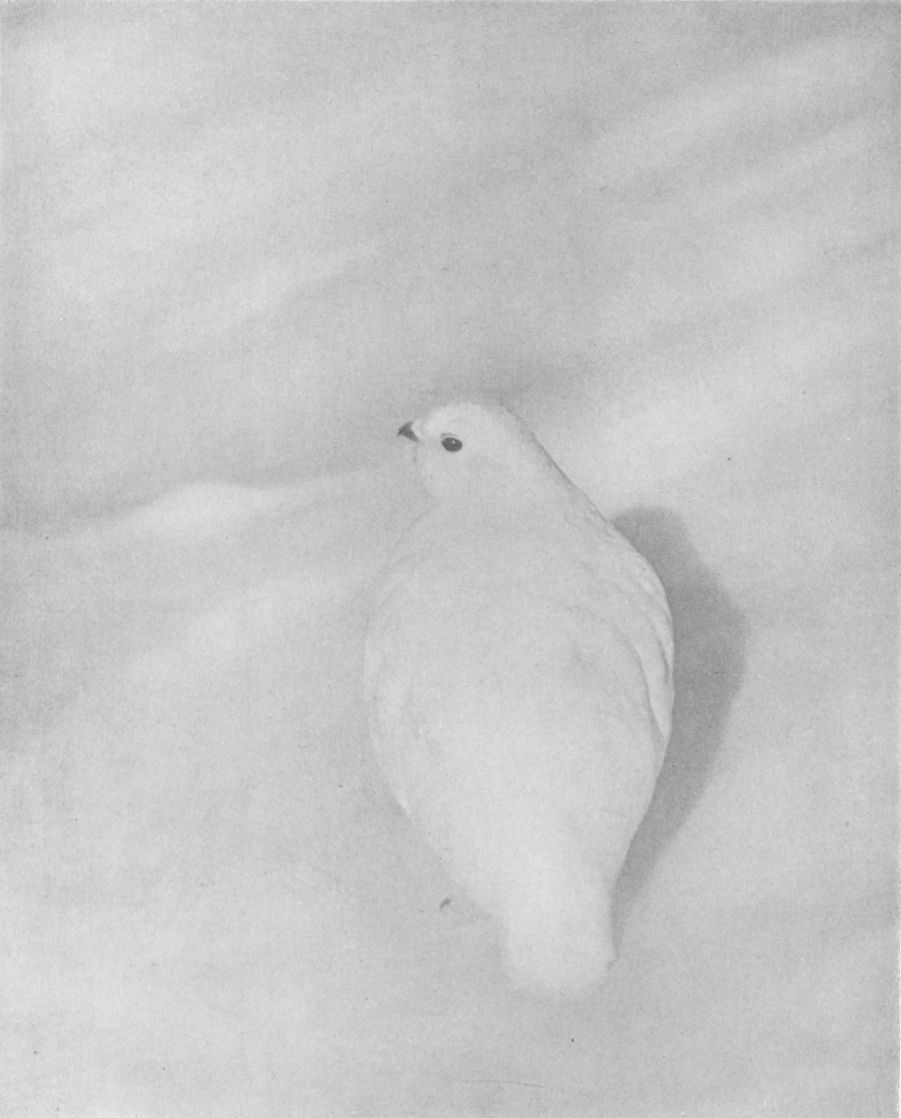

- PTARMIGAN IN WINTERBy Clark Blickensderfer, Denver, Colo.

- MARJORIEBy Sophie L. Lauffer, New York City

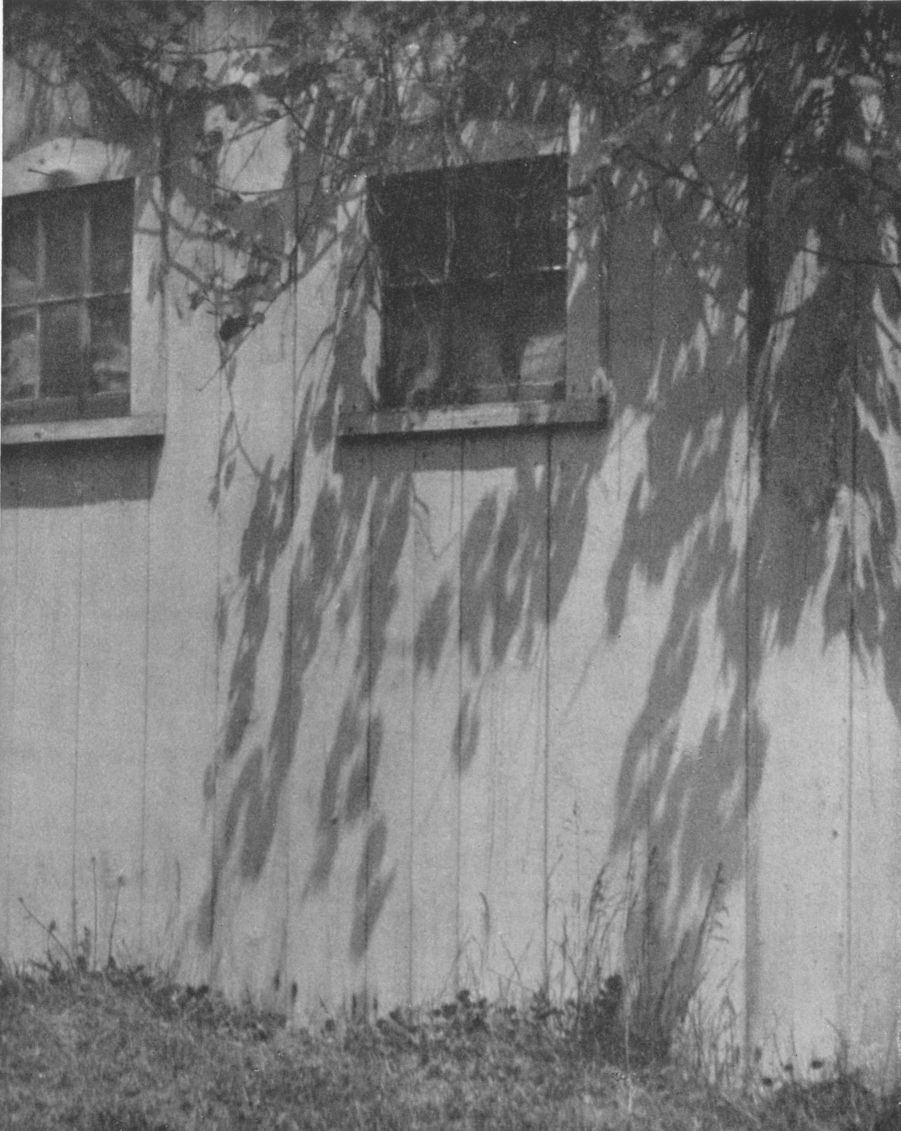

- THE PATTERNED WALLBy Mildred Ruth Wilson, Montclair, N. J.

- THE SUNNY WINDOWBy Mary F. Boyd, Chambersburg, Pa.

- AT CLARENCE WHITE'S, CANAAN, CONN.By Florence Burton Livingston, Mohegan Lake, N. Y.

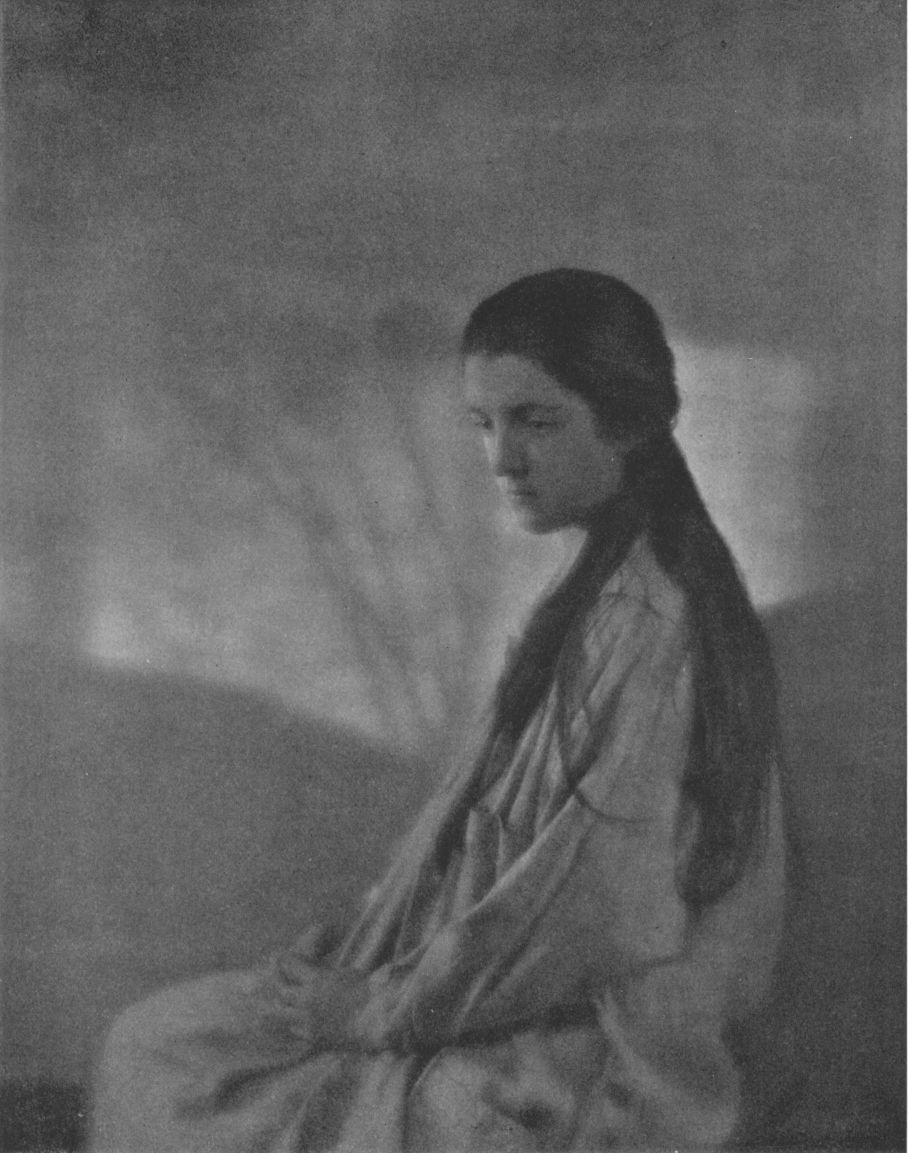

- STUDY OF A YOUNG GIRLBy charles H. Brown, Santa Barbara, Calif.

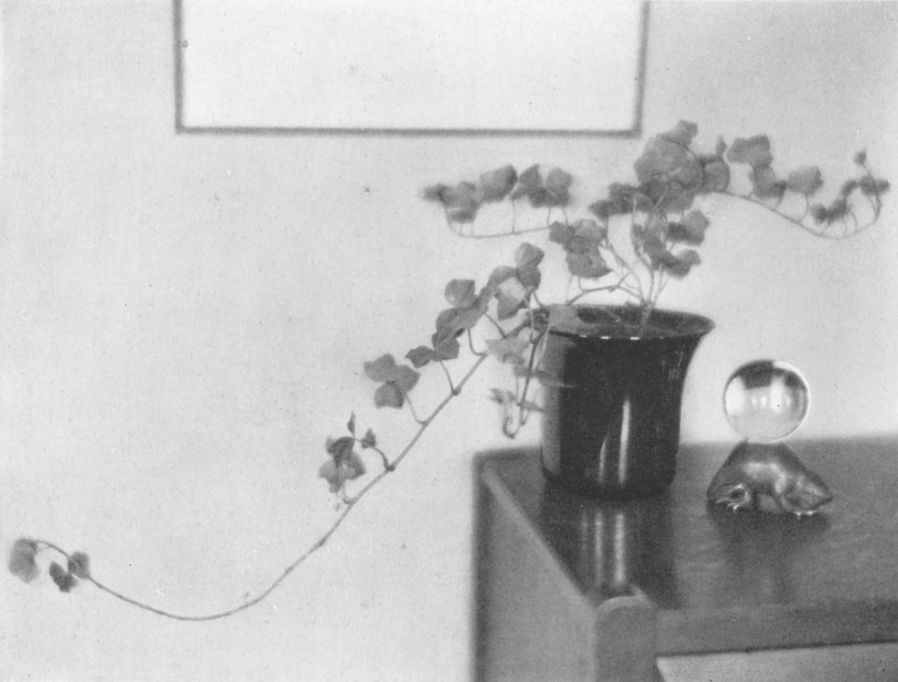

- IVY AND OLD GLASSBy Clara E. Sipprell, New York City

- ROSE DANCEBy J. Anthony Bull, Cincinnati, Ohio

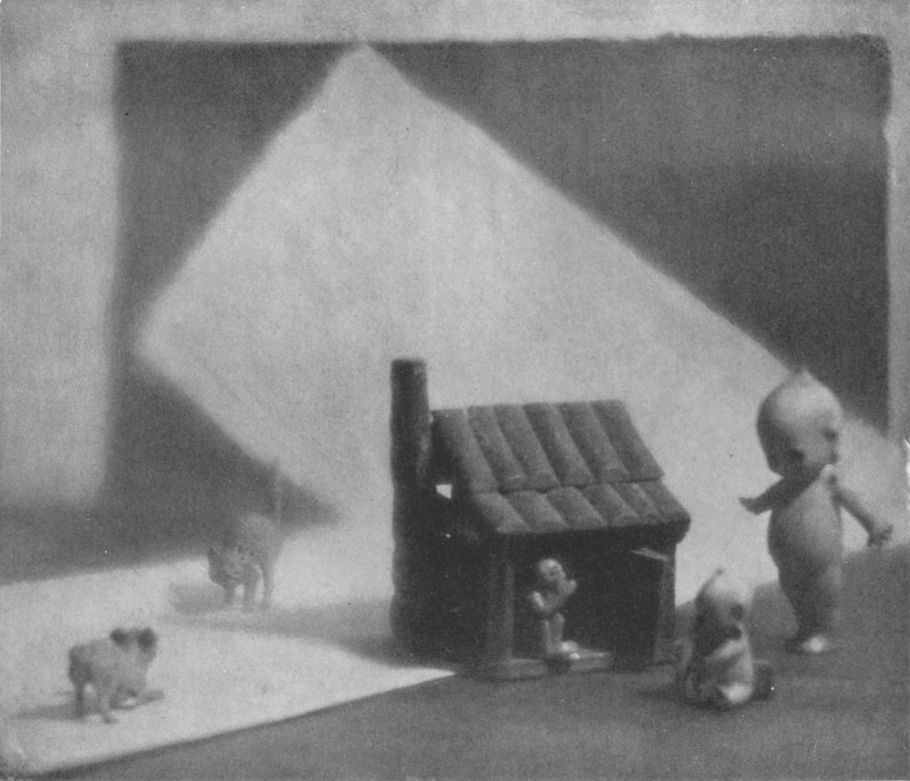

- A CONCERT IN THE NURSERYBy Frank R. Nivison, Fall River, Mass.

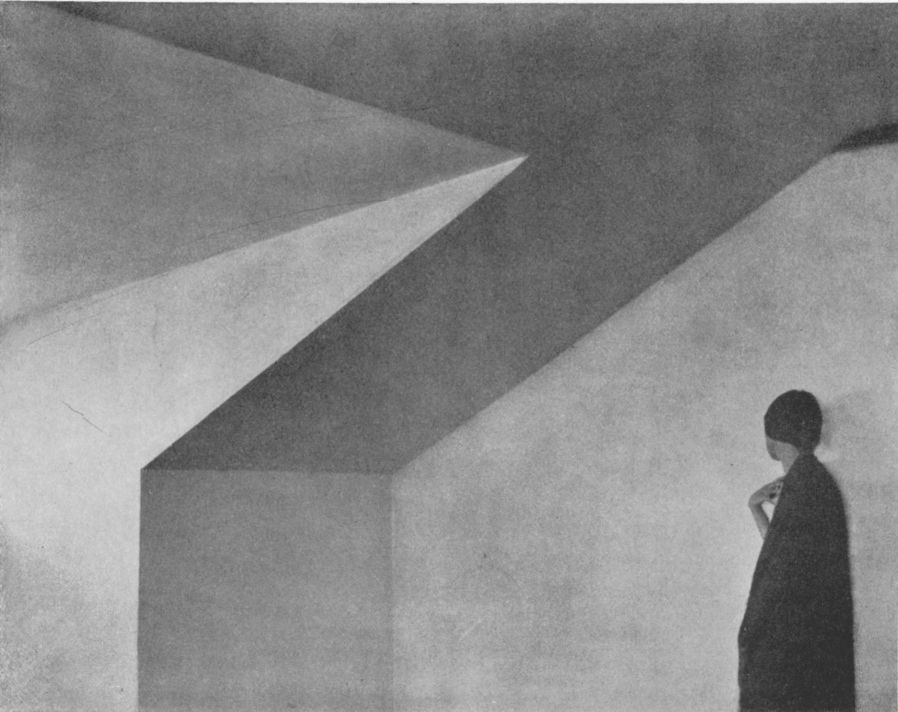

- GREY ATTICBy Edward Weston, Glendale, Calif.

- MUD-PIESBy Cornelia F. White, New York City

- CARVED WITH THE TOOLS OF TIME, THE SCULPTORBy Edith R. Wilson, Mt. Vernon, N. Y.

- MORNING GLORYBy Otis Williams, Los Angeles, Calif.

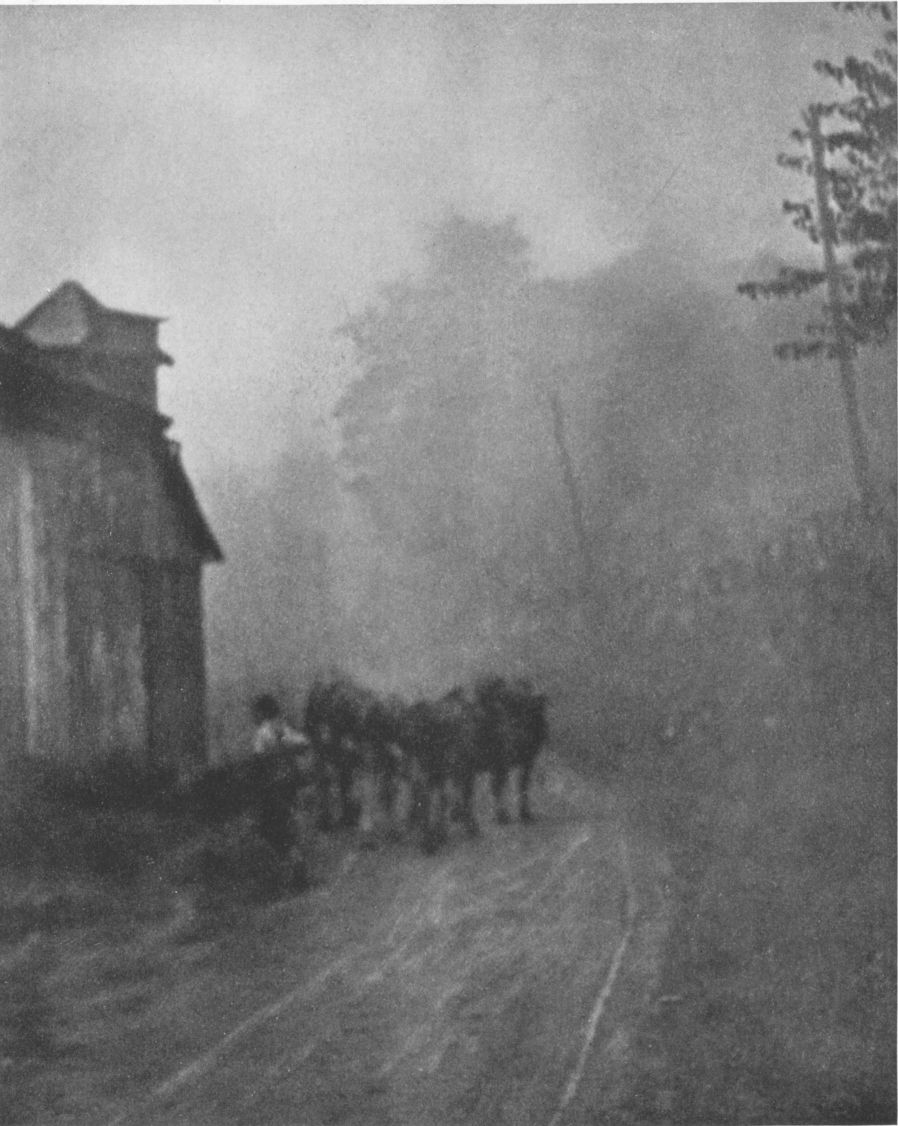

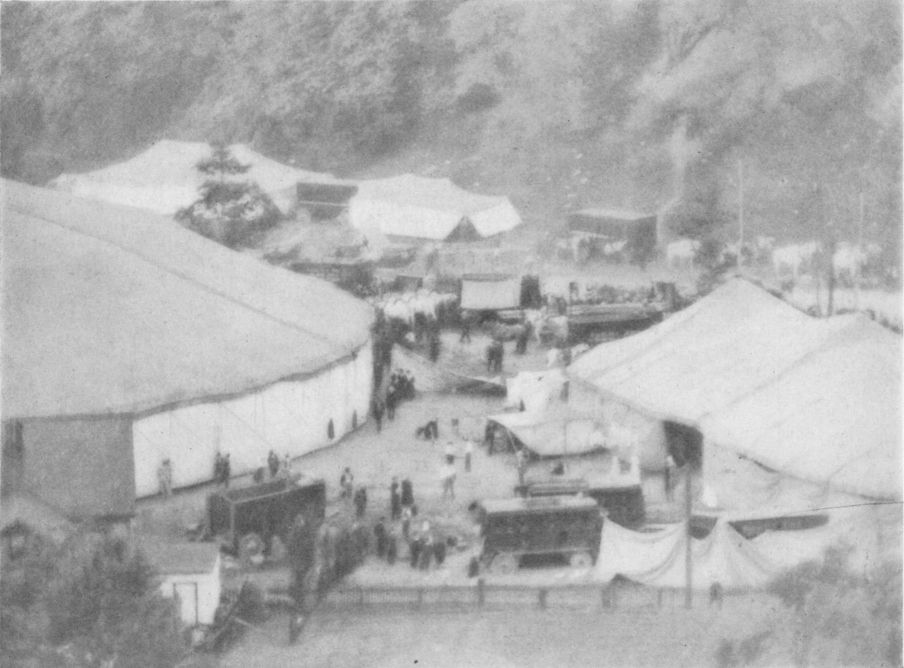

- THE CIRCUS COMES TO TOWNBy Thomas R. Hartley, Pittsburgh, Pa.

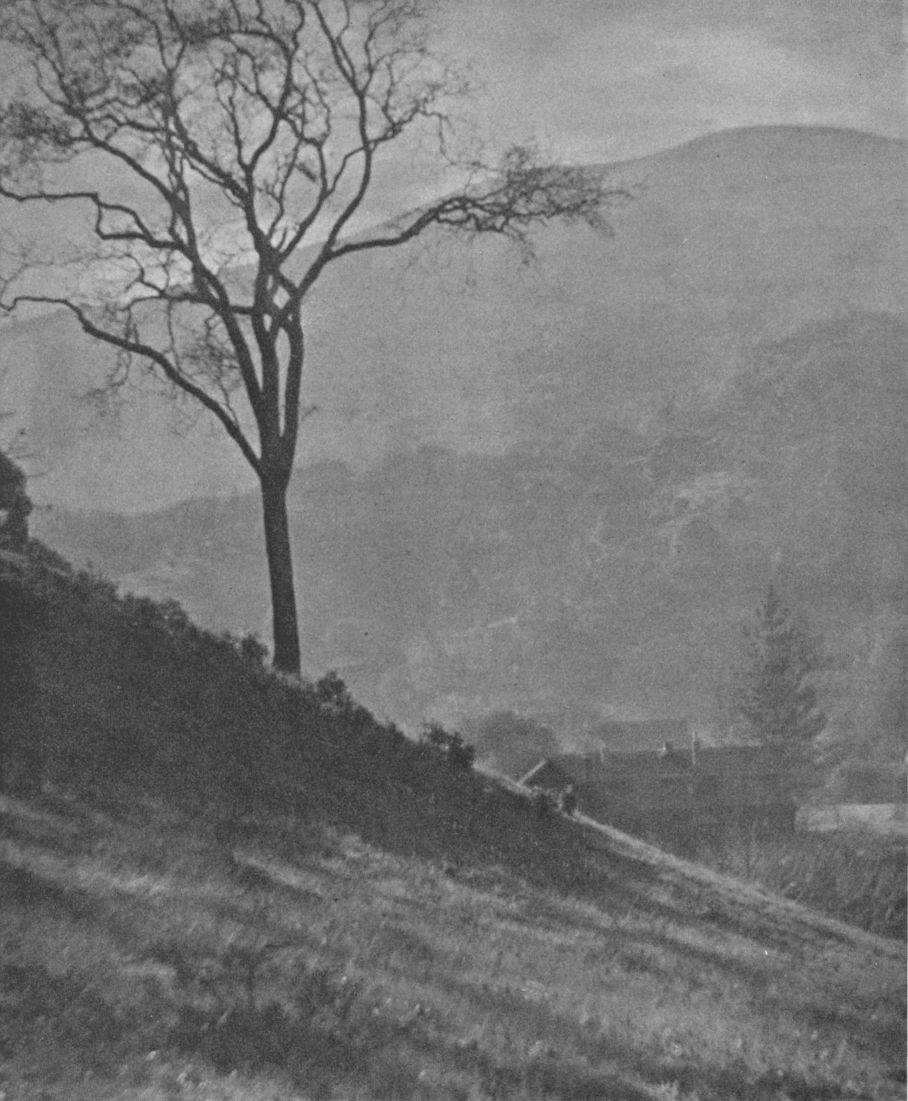

- SEAR AUTUMNBy Anson Herrick, San Francisco, Cal.

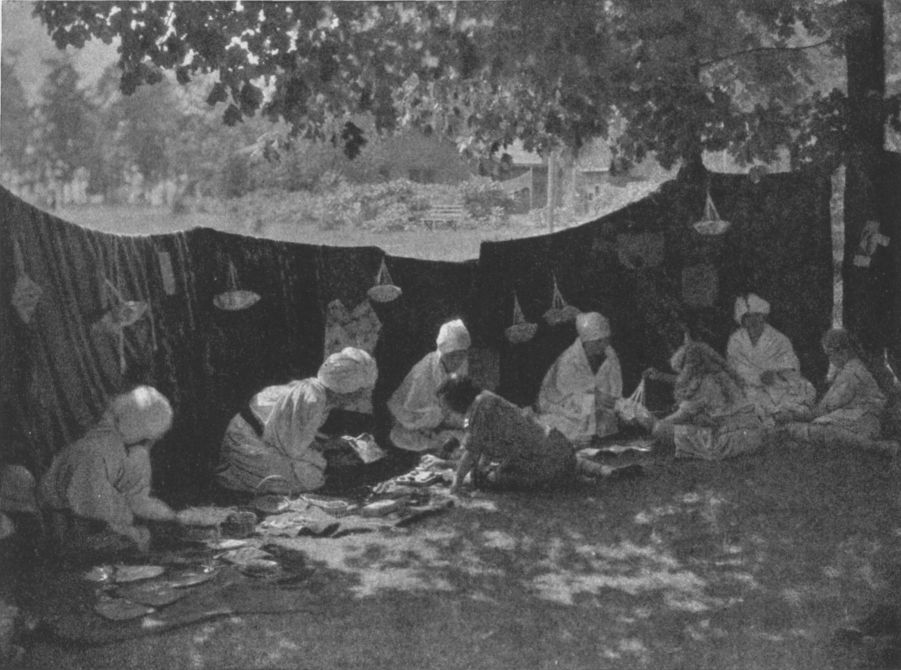

- THE BAZARBy Margaret D. M. Brown, Arlington, Poughkeepsie, N. Y.

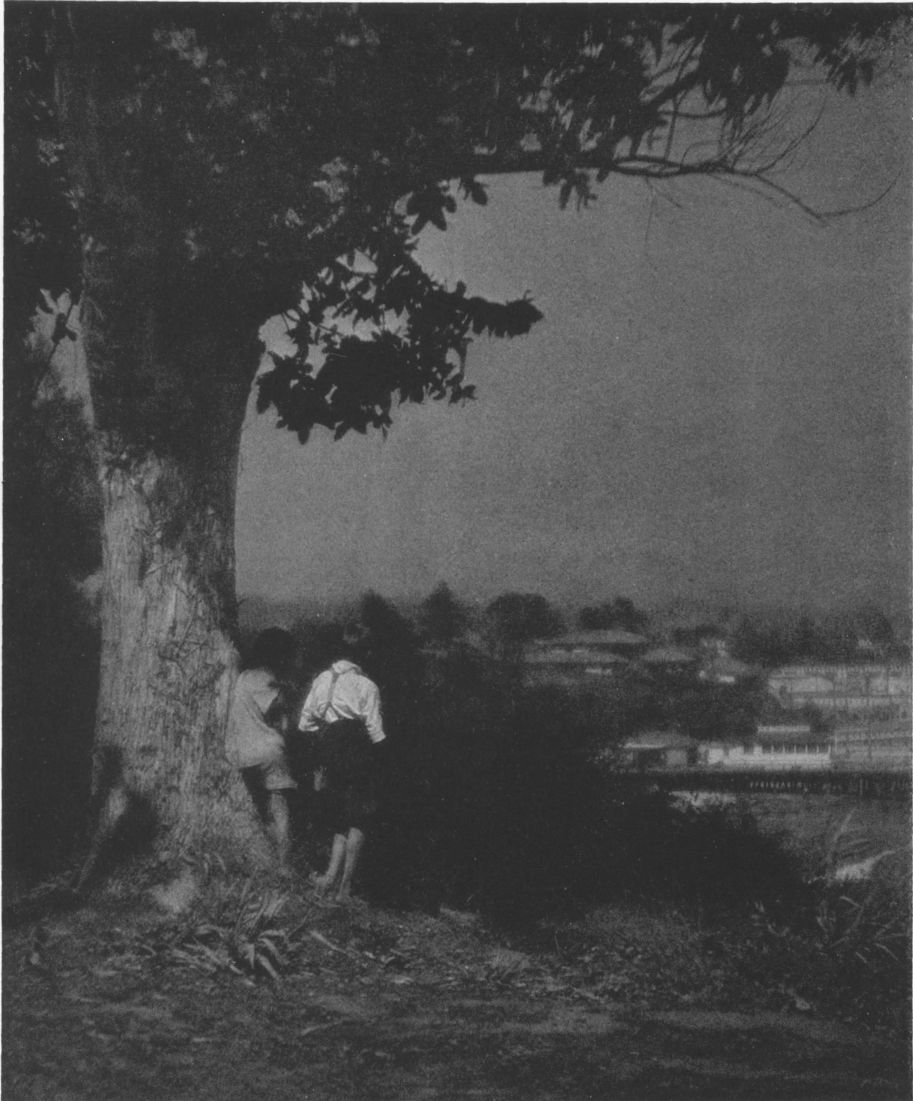

- WANDERERS FROM HOMEBy P. Douglas Anderson, San Francisco, Calif.

- DECORATIVE STUDYBy Henry A. Hussey, Berkeley, Calif.

- THE WAY UPBy Folsom Rich, Chicago, Ill.

- COLONEL MARSHBy E. L. Mix, New York City

- SHADOW DESIGNBy G. W. Harting, New York City

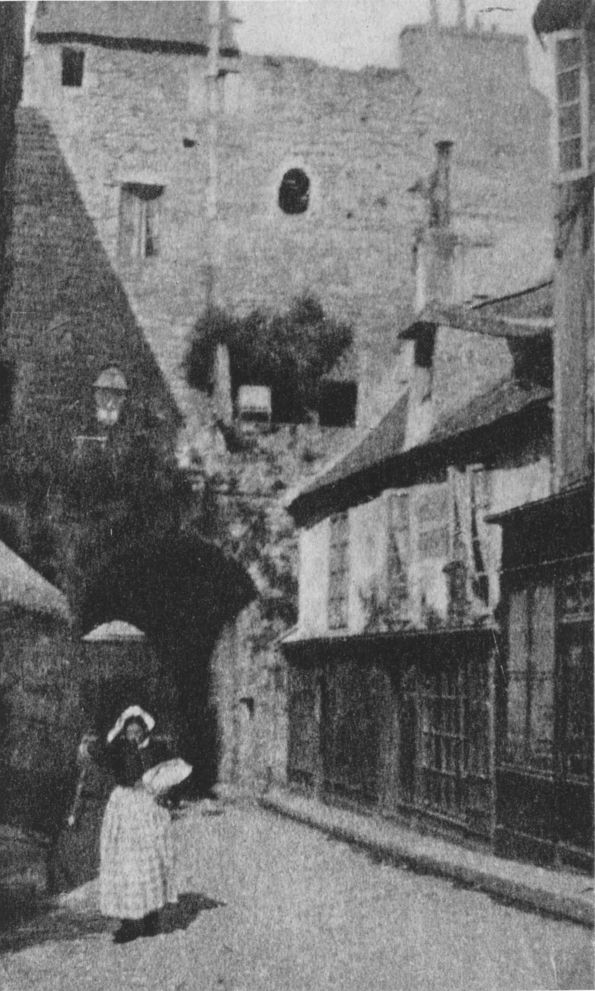

- AT GUINGAMPBy Mrs. Antoinette B. Hervey, New York City

- KISSING THE PADRE'S HANDBy Myers R. Jones, Brooklyn, N. Y.

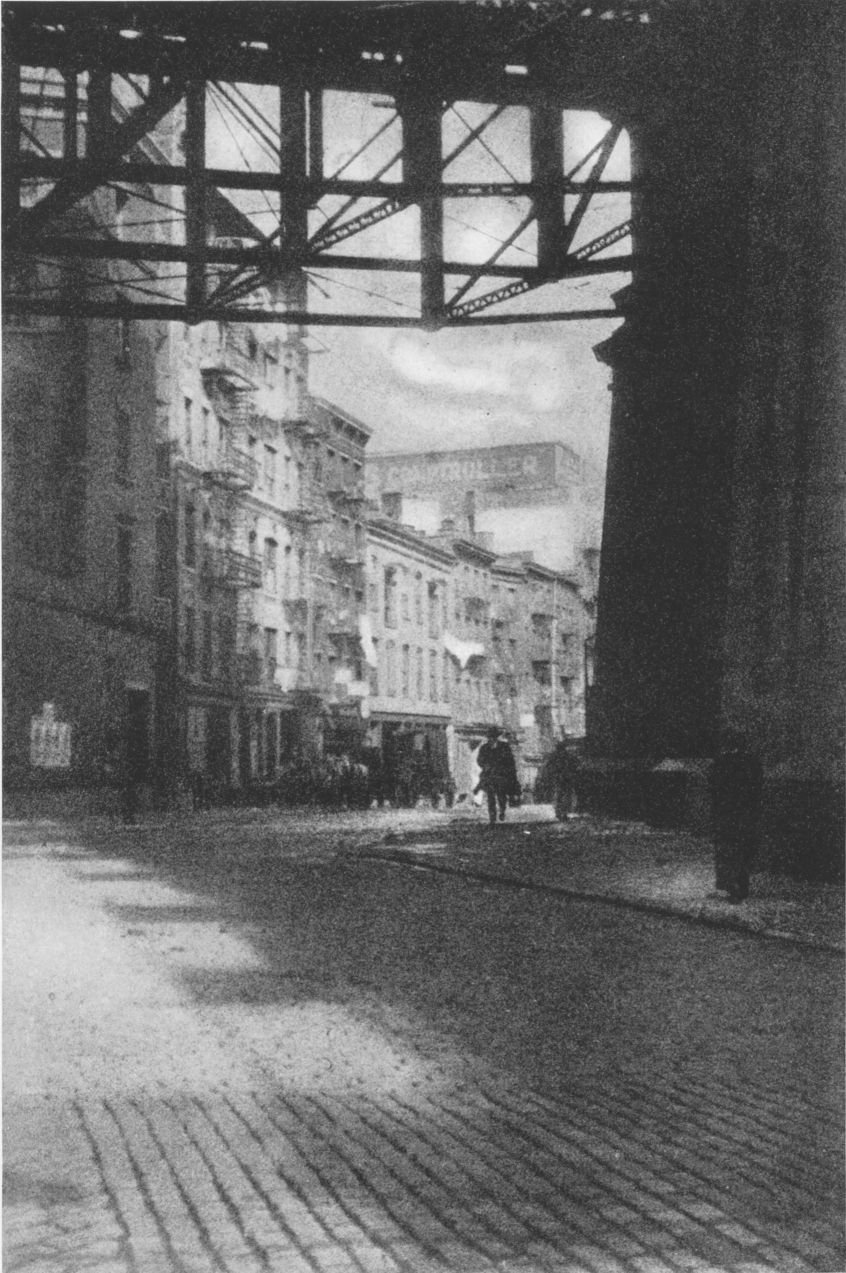

- UNDER BROOKLYN BRIDGEBy A. E. Schaaf, Cleveland, Ohio

- THE BRIDGESBy Henry Hoyt Moore, Brooklyn, N. Y.

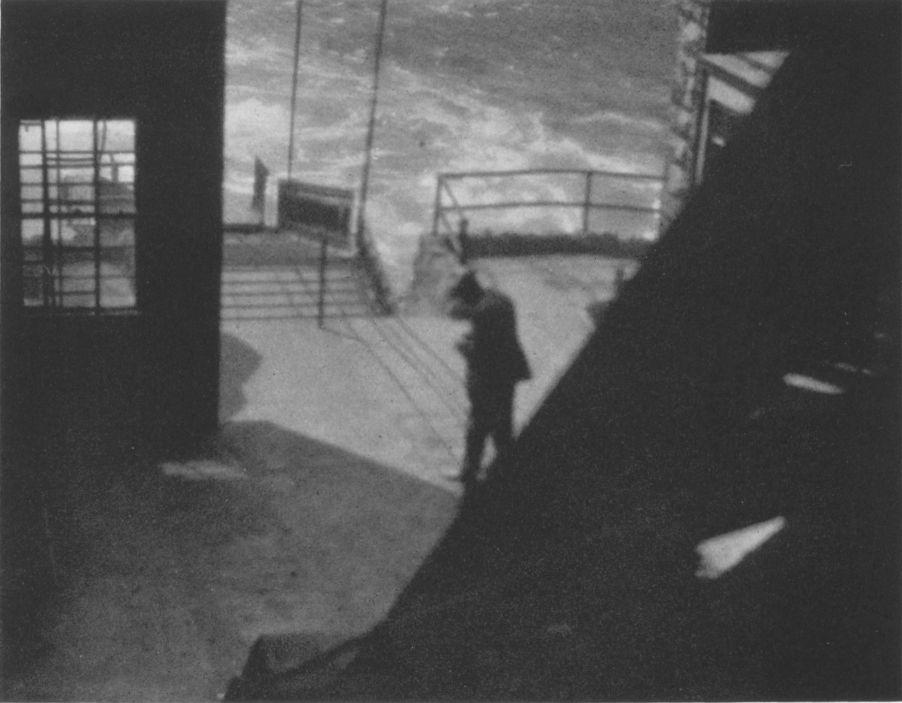

- WHIRLPOOL RAPIDS, NIAGARABy William A. Alcock, New York City

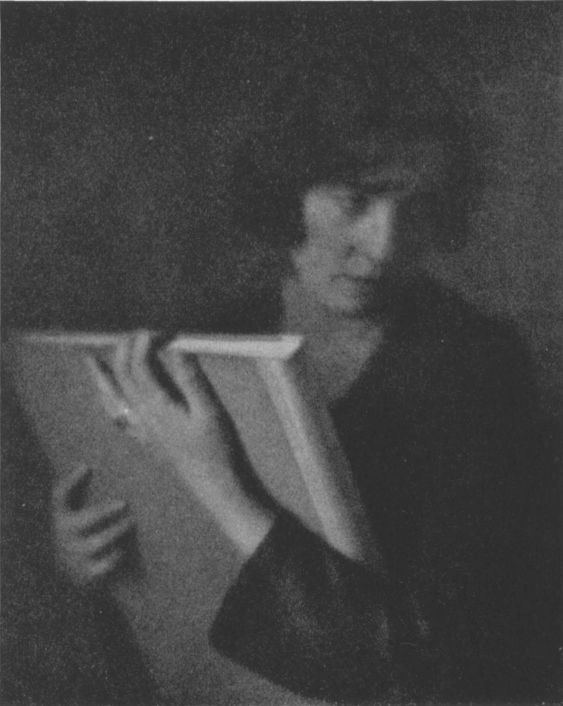

- STUDYBy A. Ralph Steiner, New York City

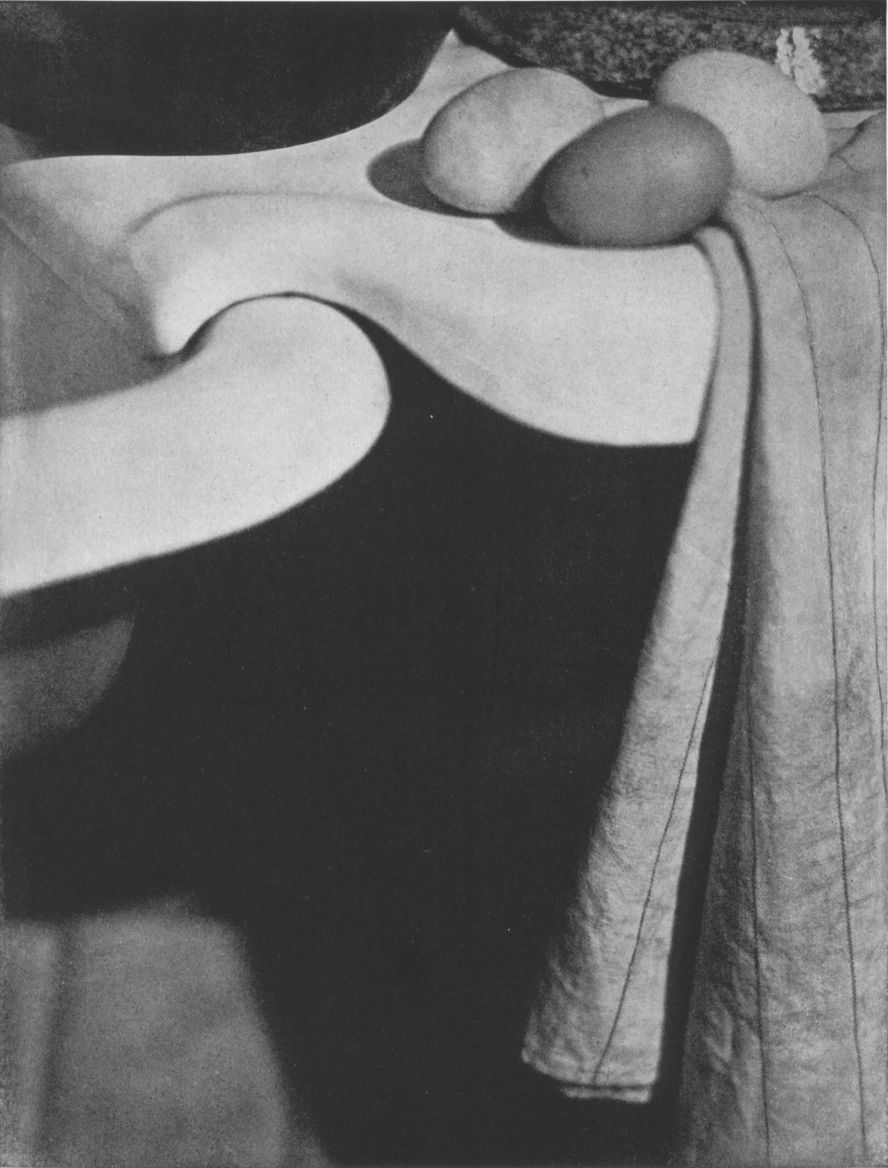

- DOMESTIC SYMPHONYBy Margaret Watkins, New York City

- MORNING SUNLIGHTBy Ira W. Martin, New York City

- L'ESPRIT DE MANDALAYBy J. Ludger Rainville, Portland, Me.

- THE GORGE BELOW THE WHIRLPOOL, NIAGARABy W. H. Porterfield, Buffalo, N. Y.

- PORTRAIT—GIRL IN BLACKBy Rabinovitch, New York City

- THE TOILERSBy Edward Ostrom, Jr., Brooklyn, N. Y.

- FROM MY WINDOWBy Betty Gresh, Norristown, Penn.

- YOUNG AMERICANBy Louis Fleckenstein, Long Beach, Calif.

- MESA DEL MARBy G. H. S. Harding, Berkeley, Calif.

- SEINE BOATSBy William B. Imlach, New York City

- THE MOON OF THE RED GODSBy Laura Gilpin, Colorado Springs, Colo.

- HIGH SEASBy Joseph Petrocelli, New York City

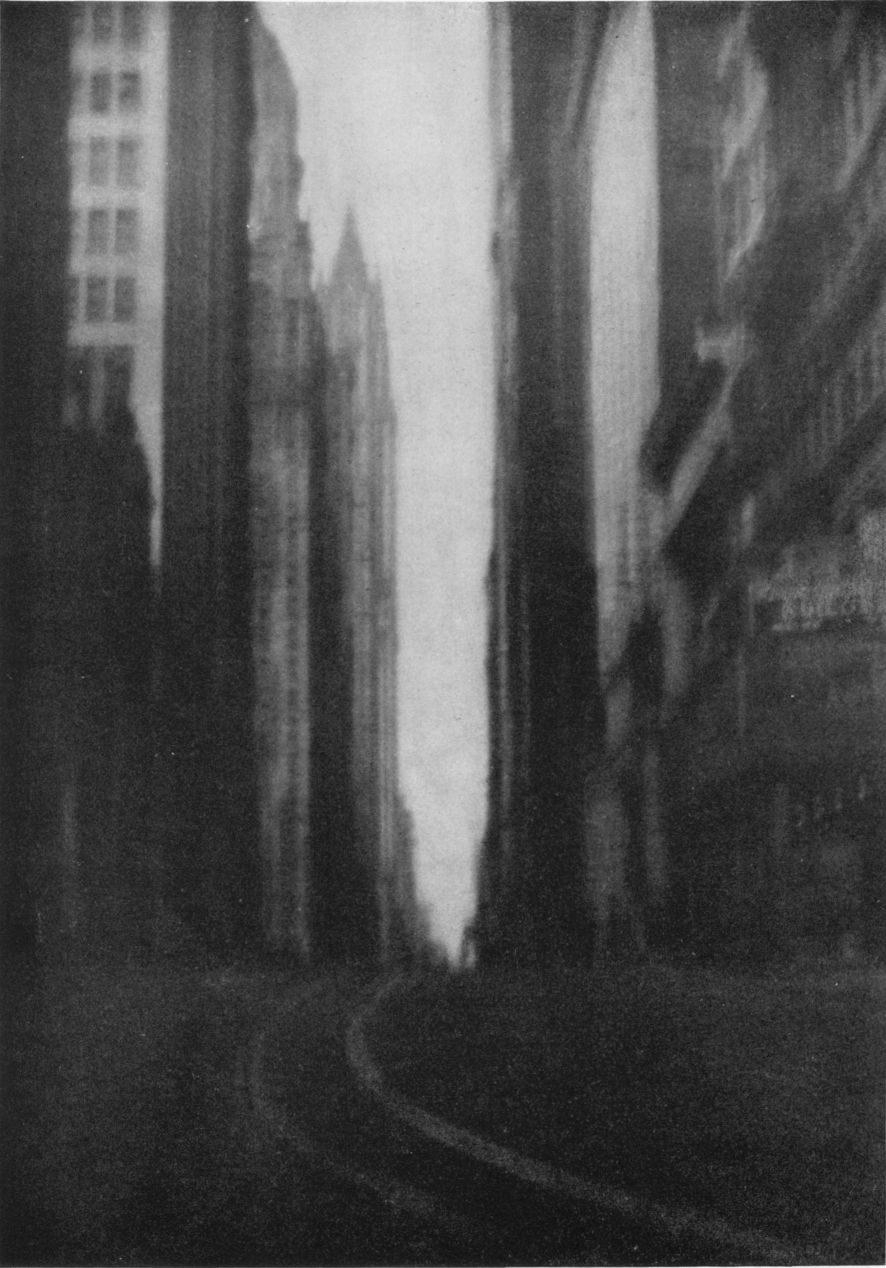

- SIXTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITYBy Ben J. Lubschez, New York City

- HILLSIDE SHADOWSBy Charles K. Archer, Pittsburgh, Pa.

- MOTHER CAREY'S CHICKENS COME HOME TO ROOSTBy Herbert B. Turner, Boston, Mass.

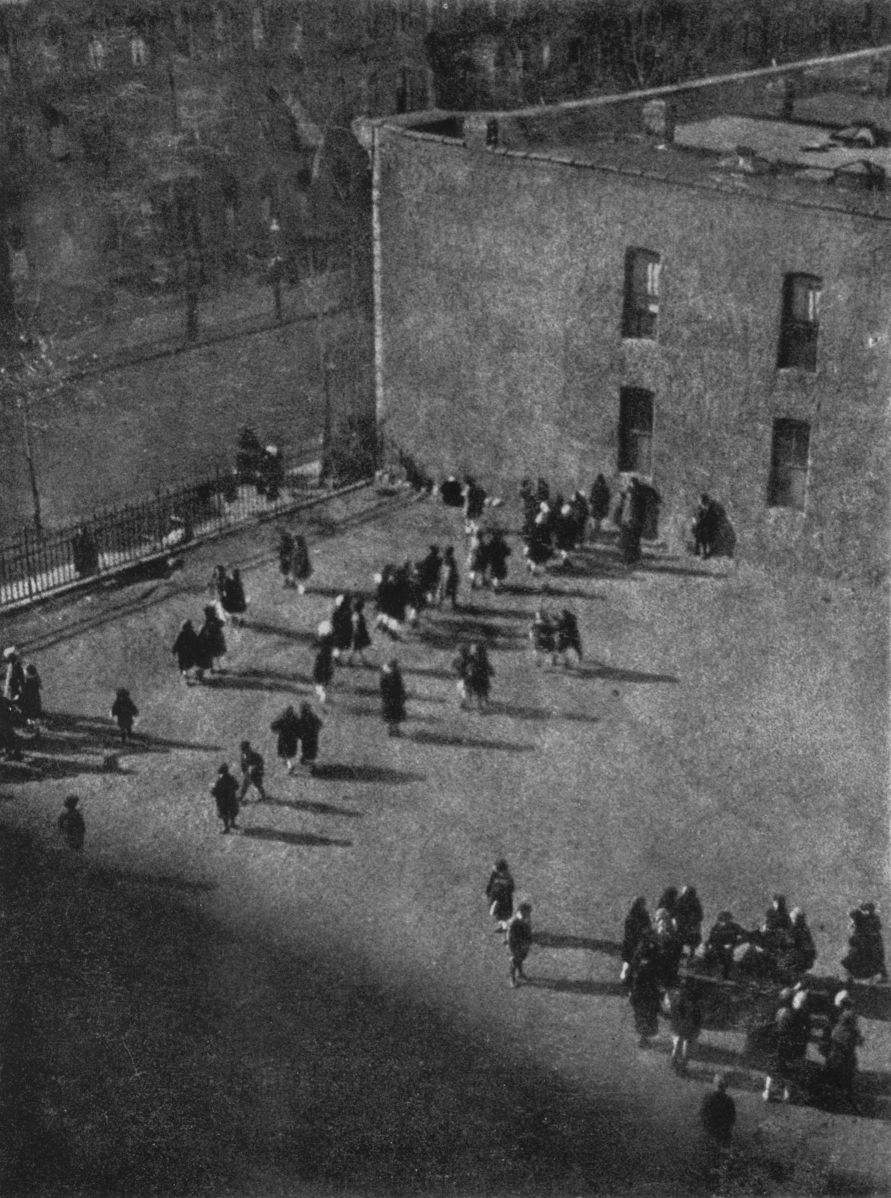

- THE SCHOOL YARDBy Vernon E. Duroe, Brooklyn, N. Y.

SINCERITY

Art that endures is sincere. It is universal in its appeal though it may have been produced in a remote corner of the world by one who was unacquainted with the work of artists.

I remember going with a friend into a picture gallery in Chicago, where an artist—I think his name was Bradford—was showing some sketches he had brought back from the arctic regions. “How true these are” I exclaimed. “How do you know?” said my companion, “you have never been to the North Pole.” “That is not necessary” I rejoined. “These studies have the truth written in every inch of them.” The work proclaimed the sincerity of its maker.

He who reverently observes life and wrests from its verities those elements which are in tune with his “ego”—transposes these into some concrete form without the damning desire for self aggrandizement, pretense, or mere seeking for originality—is building on good foundations. It is from an over-weening desire for originality that most of the affectations of so called “Modern Art” proceed.

Natural individuality—the sincere personal vision of the artist—is an inherited asset. His work is the acquiring of a technique, the constant patient practice and experiment in his particular craft. This unending exercise gives the artist power to state his message clearly—in the simplest way.

The graphic artist is concerned with “pictorial” ideas. These are necessarily limited; they must be ideas possible of expression by light and shade, by line, by form, by color. The artist's vision includes his point of view. He receives an impression and simultaneously determines how he will express it. He has, as it were, analyzed his subject and decided at once on the form of its presentation—in the clay, on the canvas, in the drawing or photograph.

Given the most favorable mechanical contrivances which science places today at the disposal of the painter or photographer, the latter may proceed in his work under the same maxims, the same theories, that guide the painter. His design may be as interesting, his key as aptly chosen, his black and white (values) as colorful, his composition in the space as distinguished.

[pg 8] If over and above his technical skill the photographer starts with a “vital idea,” he may like the painter convey with his photograph “the moving thrill” which is the final test of any work of art.

Then perchance, working patiently along the lines here barely indicated, the artist may one day unconsciously achieve that coveted note of true originality which marks a forward step to be hailed and recorded in the great tradition.

THE YEAR'S PROGRESS

We cannot claim for our art any outstanding phenomenon like the interest in the radio that has swept the country this year, or any remarkable development in the science of photography like the invention a few years ago of the Lumière plate. The day may come when our exhibitions will show masses of color on their walls which will make the water-colorists and the miniaturists green with envy, but that day is not yet. And I for one would be sorry to see it come. There is to me a charm about good monotone photography that is all its own and that puts it on a plane with etching, engraving, lithography, and other monotone processes. Of course some artists, strictly so called, object to regarding photography as anything but a mechanical process, but the number of those who would make art a close corporation is happily diminishing.

In fact, the recognition that photography is receiving from accredited representatives of the fine arts makes its position no longer a doubtful one. Any of the arts may be used for commercial purposes, but that fact does not take away from them their rightful place when they are used by competent hands for aesthetic purposes. The increasing number of museums that are opening their exhibition halls to good photography is an evidence that is obvious to all observers. Caustic critics like Joseph Pennell may decry photography, but many able artists and critics, attending exhibitions of photography that are being held in many of our centers of art, are having their eyes opened to the beauty of lens work in the hands of men and women who use the camera with feeling and insight. Then, too, we must not forget the fact that some well-known artists, beginning with D. O. Hill and continuing with Mrs. Kasebier, Frank Eugene, Steichen, and others, have found in the practice of photography a more lasting fame than in any other line of their effort.

Among notable exhibitions of the past year several should be mentioned. Of course there are what might be called the historic exhibitions that have won an established place, like the London Salon, the Royal Photographic Exhibition, the Pittsburgh Salon, the Los Angeles Salon, the Portland Exhibition, and others. [pg 10] More recently established exhibitions that are to be noted are those of the San Francisco Pictorialists, the Oakland Salon, the Canadian National at Toronto, the Buffalo Salon, and that of the Pictorial Photographers of America at the opening of the Art Center in New York City. At many of these exhibitions pictures from the same exhibitors were hung, and as the judges at practically all of them were different men (and women), including professional artists, it is evident that there was a consensus among the competent critics that these exhibitors at least are doing worthy work. But in that fact there is no cause for discouragement to the novice, for new names are to be found in the catalogues of all the exhibitions, and there is no league to keep out any individual's pictures anywhere. That is one of the triumphs of our art—that, while judges may sometimes err and exclude a good picture or select a poor one, there is a general open-mindedness in recognizing merit wherever it exists. A well-known worker is pretty sure to have his photographs declined by the judges in most of the photographic exhibitions if he falls below his standard, and, on the other hand, a gifted beginner will quickly get a place in the seats of the mighty if he can produce the photographs that entitle him to distinction.

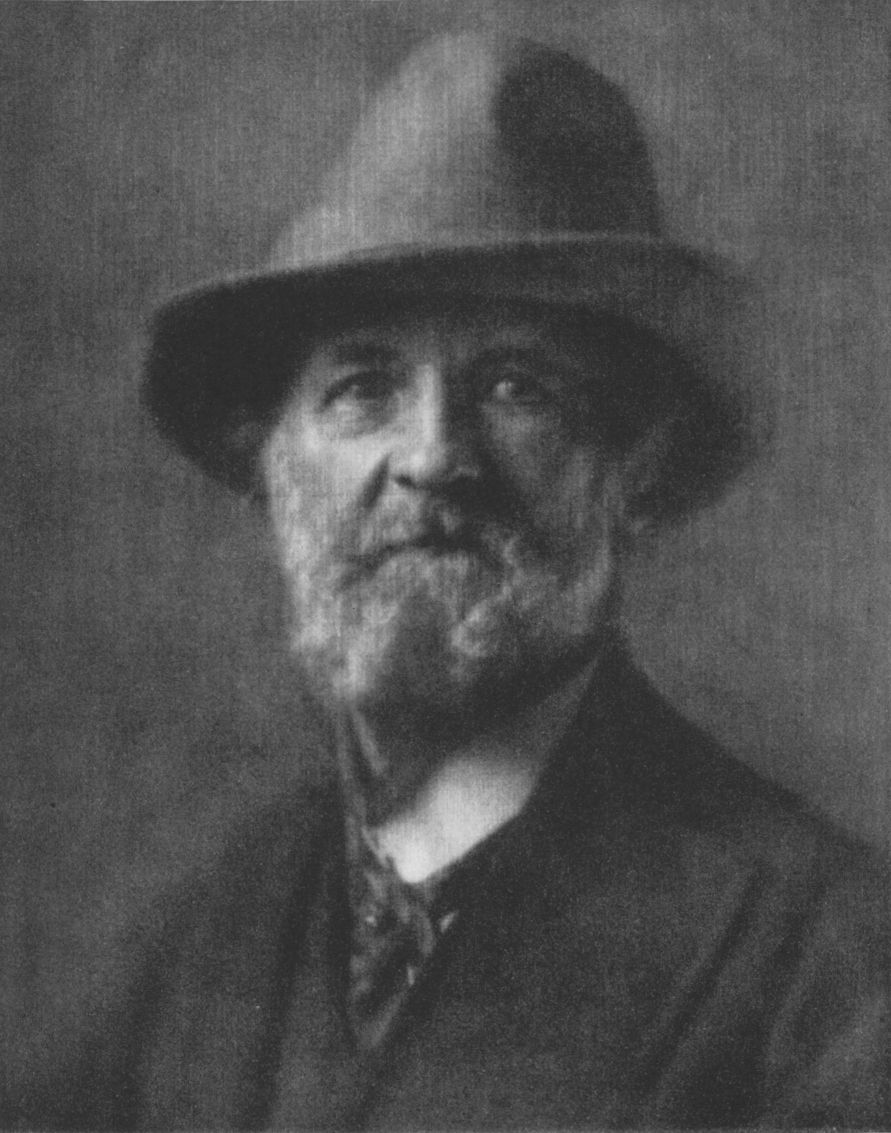

Some notable one-man exhibitions have been held since our last Annual was published. Among them should be mentioned those of the veterans Alfred Stieglitz and Rudolph Eickemeyer in the Anderson Galleries in New York—and it is a significant testimony to the lure of our art that these masters of it have “come back”; those of Dr. H. B. Goodwin, of Stockholm, at the Brown-Robertson Gallery, and E. O. Hoppe, of England, at Wanamaker's, in New York; that of Clarence H. White, of New York, at the Art Center; the joint exhibition of prints of W. E. Macnaughtan and William A. Alcock, of Brooklyn, at the New York Camera Club, and of F. J. Mortimer and Alexander Keighley of England at the same place; and by Mrs. Antoinette B. Hervey, Miss Sophie Lauffer, Nicholas Muray, and F. O. Libby, with numerous others, that show the popularity of this method of placing good work before the public. Such exhibitions should be encouraged, for not only do they stimulate the exhibitor to show worthy work, but they are in the nature of spurs to the activity of every serious worker who has the privilege of seeing them.

As to processes that are in favor, the bromoil and the bromoil transfer still continue to attract a host of workers. European workers seem still to have access to better and cheaper materials for this work than we in America, as is evidenced by the number and quality of the prints that are produced in the Scandinavian countries and in Germany, where bromoil work has even acquired a commercial status among professional photographers.

[pg 11]The question is sometimes raised whether the general public who attend photographic exhibitions are interested in processes as such. I think the question must be answered in the negative. It is the general effect that interests the outsider, and he cares not whether the print is a gum, a bromoil, a bromide, a platinum, or a palladiotype. We must beware lest we get enamored of a process rather than the result. I say this with no disrespect to the bromoilists, many of whom are gifted workers and endowed with art feeling. But we must remember that we are working to popularize photography as an art as well as to demonstrate our own artistic feeling and technical skill, and we ought not to lay too great stress on a difficult branch of our work, to the discouragement of those who would seek to share the delights of a beautiful recreation. The problem must be left to each individual. The beauty of a bromoil print, for instance, is supreme to its devotee: is its superiority to other processes worth the time and the toil necessary to make it, which might be devoted to the study of composition, of a wider range of subject, or to the mastery of simpler processes? Picture construction and print quality are after all the main things in photography, not the medium we use.

There is no royal road to distinction in photography, but each year sees some helps devised for the earnest worker, whether amateur or professional. For the amateur there is now an increasing variety of cameras and photographic material. New cameras are coming from abroad, among them a small French moving-picture machine, the “Sept,” which can be carried in the hand and with which, it is claimed, good “stills” may be taken as well as good regulation movie pictures. An auto-focus enlarger, at a comparatively small price, has also been put on the market for amateur use; and with the increasing use of small cameras and the adoption of simpler methods this may prove a boon to those who wish to make bromide enlargements more easily than they could by the older methods. It is to be regretted that platinum paper is not being manufactured in America for photographic purposes, for the quality of a choice platinum print is still regarded by many as unsurpassed, and many workers wish to see platinum resume its old place among the photographer's resources. Many “spotlight” machines and artificial illuminating devices have been put on the market, and with these the photographer will be equipped to play on his sitters the “light that never was on sea or land,” if he so desires. But the ingenious photographer who is quick to seize good lighting effects will not need the aid of artificial lighting, anymore than did the early master of photography, D. O. Hill, whose simple effects reached almost the finality of lens art.

Just here I might add a word as to the increasing coalescence of the amateur and the professional photographer in America. Strictly speaking, an amateur may [pg 12] be said to be one who gets no return in money for his work, while the professional's work is mainly financial in its object. The amateur photographer, however, finds his expenses heavy and the temptation strong to sell his pictures; while in America the professional photographer is frequently so much in love with the pictorial possibilities of his work that he loses sight of the financial end of it.

For the worker to get the real enthusiasm and benefit from photography, the thing now necessary to mark a distinct note of progress, or to make an outstanding year, is to have a great international exhibition, similar to the one held in Buffalo in 1910. This, I am glad to say, is already planned for next year, to be held in New York City, which, although the great center of activity, has never had an exhibition of this kind.

ON IDEAS

[pg 13]Thackeray resigned the editorship of a British periodical only because he could not endure the ordeal of rejecting the thousands of submitted manuscripts. This is a distressing phase of an Art Director's duties and to my mind his most sacred obligation. No matter how hardened by experience, a conscientious editor cannot fail to suffer for and with the unhappy authors and artists whose work goes back with the proverbial pink rejection slip. Why are drawings and photographs rejected? What is wrong with the great mass of rejected material? My observation is that they suffer more from a lack of clear thinking and careful execution than from a paucity of ideas.

The weird conceptions and grotesque ideas in back of most of the unsolicited material submitted would make one easily believe that the artists are inmates, or perfectly qualified to be inmates of asylums. I am seldom inclined or required to urge an artist to seek originality of idea. My constant plea, and what to my mind is a prerequisite, is an optimistic point of view, a sound, intelligent thought rendered with, may I say, reverence.

Struggling young artists are constantly advised to cultivate their imagination. What is imagination? Arthur Brisbane defined this in the most compact, tangible statement: “Imagination is nothing more than the power to see and realize what others fail to see and realize.” The illusive idea that we are searching for is nothing hidden or mystic but right before our very eyes. We have only to “see and realize.”

It is conceded, I am sure, that the idea is the prime requisite of a political cartoon. A prominent cartoonist was once asked where he got his ideas. In reply he asked “what ideas?” Men of ideas have brains that function exactly as those of other normal well-ordered citizens. They are not gifted by strange kinks in their brain cells. When the prominent cartoonist is contemplating the banal act of shaving or putting in a new furnace, his thoughts are no more or less exalted or lofty than when creating a cartoon idea intended to sway public opinion. Strange, isn't it, that considering the thousands of earnest thinking [pg 14] diligent-working young students, that there are so few artists whose work reflects real genius? Strange that the standard of the Graphic Arts is as discouragingly low as it is considering this army of talent. But even more strange that this contradiction to the law of averages is also applicable to the field of sports—to a field so practical, tangible and therefore measurable. Every healthy-minded youngster born, has two early ambitions: one to be a great baseball player, another to become President. And yet the scouts and managers for the Big Leagues have difficulty in discovering talent above the average.

In the field of Pictorial Photography, the average is exceedingly high. This volume is a demonstration. To be sure, if one seeks, one can quickly discover atrocities in the galleries and on the printed page; but my conviction is that the progress from the purely aesthetic standpoint has kept pace with the mechanical and scientific strides made in Photography.

Quotations are generally sneered at, but they make excellent conclusions. Some one once said: “All one's life is music if one touched the notes rightly and in tune.” A very happy thought and true. But finding the right note is infinitely more difficult than the striking in tune. Ideas, to be sure, you must seek. But orderly thought, patience and fine craftsmanship in carrying out your idea frequently count for more than the originality or brilliance of the idea itself. Owing to the restlessness of the world situation—wars and rumors of wars, strikes and overtendency towards jazz and slang—there is already, especially in the work of youngsters, too evident an urge to be different; different merely for the sake of being different.

A thought possibly worthy of the deliberation of every artist is that Distinction is a result, never the object, of a great mind.

[pg 16]

By Thos. O. Sheckell, Salt Lake City, Utah

By Wayne Albee, Seattle, Washington

By Ernest M. Pratt, Los Angeles, Calif.

By Robert R. McGeorge, Buffalo, N. Y.

By William Gordon Shields, New York City

By Dr. Chas. H. Jaeger, New York City

By Julia Marshall, Duluth, Minn.

By Robert B. Montgomery, Brooklyn, N. Y.

By C. R. Herzler, New York City

By Johan Hagemeyer, San Francisco, Calif.

By Amelia H. McLean, Bronxville, N. Y.

By H. A. Latimer, Boston, Mass.

By Paul Wierum, Chicago, Ill.

By Arnold Genthe, New York City

By Eugene P. Henry, Brooklyn, N. Y.

By W. H. Zerbe, Richmond Hill, N. Y.

By Ernest Williams, Los Angeles, Calif.

By William Elbert Macnaughton, New York City

By Helen W. Drew, Montclair, N. J.

By K. B. Lambert, Glen Ridge, N. J.

By Harry C. Phipps, Chicago, Ill.

By E. E. Gray, Chicago, Ill.

By Clarence H. White, New York City

By Olive Garrison, Yonkers, N. Y.

By Jane Reece, Dayton, Ohio

By Dr. D. J. Ruzicka, New York City

By Francis O. Libby, F.R.P.S., Portland, Me.

By Jerry D. Drew, Montclair, N. J.

By John Paul Edwards, San Francisco, Calif.

By W. W. Zieg, Pittsburgh, Pa.

By George Henry High, Chicago, Ill.

By Dr. A. D. Chaffee, New York City

By N. S. Wooldridge, Pittsburgh, Pa.

By Clark Blickensderfer, Denver, Colo.

By Sophie L. Lauffer, New York City

By Mildred Ruth Wilson, Montclair, N. J.

By Mary F. Boyd, Chambersburg, Pa.

By Florence Burton Livingston, Mohegan Lake, N. Y.

By charles H. Brown, Santa Barbara, Calif.

By Clara E. Sipprell, New York City

By J. Anthony Bull, Cincinnati, Ohio

By Frank R. Nivison, Fall River, Mass.

By Edward Weston, Glendale, Calif.

By Cornelia F. White, New York City

By Edith R. Wilson, Mt. Vernon, N. Y.

By Otis Williams, Los Angeles, Calif.

By Thomas R. Hartley, Pittsburgh, Pa.

By Anson Herrick, San Francisco, Cal.

By Margaret D. M. Brown, Arlington, Poughkeepsie, N. Y.

By P. Douglas Anderson, San Francisco, Calif.

By Henry A. Hussey, Berkeley, Calif.

By Folsom Rich, Chicago, Ill.

By E. L. Mix, New York City

By G. W. Harting, New York City

By Mrs. Antoinette B. Hervey, New York City

By Myers R. Jones, Brooklyn, N. Y.

By A. E. Schaaf, Cleveland, Ohio

By Henry Hoyt Moore, Brooklyn, N. Y.

By William A. Alcock, New York City

By A. Ralph Steiner, New York City

By Margaret Watkins, New York City

By Ira W. Martin, New York City

By J. Ludger Rainville, Portland, Me.

By W. H. Porterfield, Buffalo, N. Y.

By Rabinovitch, New York City

By Edward Ostrom, Jr., Brooklyn, N. Y.

By Betty Gresh, Norristown, Penn.

By Louis Fleckenstein, Long Beach, Calif.

By G. H. S. Harding, Berkeley, Calif.

By William B. Imlach, New York City

By Laura Gilpin, Colorado Springs, Colo.

By Joseph Petrocelli, New York City

By Ben J. Lubschez, New York City

By Charles K. Archer, Pittsburgh, Pa.

By Herbert B. Turner, Boston, Mass.

By Vernon E. Duroe, Brooklyn, N. Y.

THE PURPOSE OF THE PICTORIAL PHOTOGRAPHERS OF AMERICA

To stimulate and encourage those engaged and interested in the Art of Photography; to honor those who have given valuable service to the advancement of Photography; to form centers for intercourse and for exchange of views; to facilitate the formation of centers where the photographers may be always seen and purchased by the public; to enlist the aid of museums and public libraries in adding photographic prints to their departments; to stimulate public taste through exhibitions, lectures, and publication; to invite exhibits of foreign work and encourage participation in exhibitions held in foreign countries; to promote education in this Art so as to raise the standards of Photography in the United States of America.

THE PICTORIAL PHOTOGRAPHERS OF AMERICA

Some five years ago a small group of photographers in New York City and vicinity formed a nucleus for the institution of a society. Its name was ambitious—The Pictorial Photographers of America; its aims and objects sounded visionary, almost fantastic. Already many times printed, they bear repetition and have been incorporated in a separate page in this book. In one sense these aims were visionary, because they were thought out and formulated by men of vision, who now stand justified: in hardly one of these directions have we failed to make important advance and in many we have pushed far. But we do not rest upon what we have done; in none of these pursuits can we pause and say “It is accomplished”; much remains to be achieved in every line; new activities constantly present themselves; and the maintenance of each of our undertakings implies continuance of effort nearly as strenuous as that of its initiative.

In the Art Center, from its inception as a mere idea, the Pictorial Photographers of America have been active. This Institution, enthusiastically planned and rapidly carried forward, has been since November, 1921, an accomplished fact. It is devoted to the development and association of various Arts and Crafts, to interesting the public therein and, particularly, to bringing producer and user together. It is compounded of the seven following Societies, to wit: Art Alliance of America, Art Directors Club, American Institute of Graphic Arts, New York Society of Craftsmen, Society of Illustrators, the Stowaways and the Pictorial Photographers of America, which together own a fine, large, centrally situated building, completely remodeled for their occupation and divided into galleries, meeting rooms and executive offices. The Pictorial Photographers, besides holding their general meetings in one of the larger rooms and sharing the lounge for social purposes, have now their own room (with attendance) which, accessible day and evening, will be a meeting place for our members, resident and non-resident, and a center from which we may get into touch with one another; a place for the continuous exhibition of prints upon the walls and in portfolios, where art lovers, buyers and advertisers can see and, if they wish, arrange to buy our work or come into communication with our workers; a reading room supplied with recent photographic magazines and literature; and a publicity bureau with a bulletin board displaying announcements of current and future local and national photographic events.

The usual series of monthly meetings has been held throughout the past season, with a larger attendance than heretofore. Our first meeting was the usual informal “get-together” dinner. Our second took place in the opening week of the Art Center: we held an informal reception during the afternoon and in the evening gave a large dinner to our members and friends. Mrs. Ripley Hitchcock was our guest of honor. Our general meeting followed, at which [pg 96] Mr. Ben J. Lubschez addressed a large audience upon the “Story of the Motion Picture,” followed by Mr. Herbert J. Seligman upon “Cinema Plastik.” At our succeeding meetings we have had the pleasure of listening to Mr. William H. Zerbe, Mr. Richard M. Coit, Mr. Ira W. Martin, Mr. Pirie MacDonald, Mr. Edward Penfield, Mr. Fred Dana Marsh and Mr. Alexander P. Milne. Interest in the monthly print contests held at these meetings has been maintained and the value of the feature demonstrated by the gain in number and quality of the entries. We hope during the succeeding year to keep the monthly prints upon exhibition until the following meeting, believing that this measure will both stimulate those who show and benefit those who look.

As a part of the general exhibition of all the conjoined Societies throughout the opening month of the Art Center (November, 1921) we presented a collection of one hundred and sixty-two prints from our own membership, filling one of the large galleries upon the ground floor. This Exhibition, representing all parts of the country, was exceedingly well received and, under the charge of the American Federation of Arts, was afterwards shown in Corvallis, Oregon; Emporia, Kansas; College Station, Texas; and Greeley, Colorado.

During the past summer we have shown at the Art Center a collection of fifty prints from the Copenhagen Photographic Amateur Club. We have thus enjoyed the double privilege of in some measure returning the courtesy of the Copenhagen Club, who invited us to cooperate in their Twenty-fifth Anniversary Exhibition, and of seeing and showing representative and distinguished work from the members of this Club.

A periodical Bulletin of the meetings, activities and news of the Society, long contemplated, has been established, which through the ensuing year we expect to issue monthly in the shape of an eight-page miniature magazine. The Art Center has also undertaken the issue of a monthly Bulletin of the conjoined Societies, in which we shall have our proportionate share.

In conjunction with the Shadowland Magazine we have begun a series of monthly print contests, in which the magazine offers to the winners not only valuable prizes but expert reproduction and wide publicity. Though not many months in operation, entries and awards have been encouraging and interest has been aroused abroad, even so far as China, as well as at home.

We have become affiliated with The Club Photographer of Great Britain, contributing the articles and illustrations of the issue for April, 1922, and have been invited to supply such material in the future for one number per year.

It is interesting to note that, besides satisfactory sales at home, we received from Japan two large orders for Pictorial Photography in America for 1921.

Our year has been shadowed by the death of Edward R. Dickson, one of the Society's most enthusiastic founders and active promoters. We can do no better than to quote the brief memorial account of his life, written at the time of his death by a few of his intimate friends.

“On March 5, 1922, occurred the untimely death of Edward R. Dickson, one of the most eager and gifted workers in the group of men and women devoting themselves to pictorial photography. He was born in Quito, Ecuador, forty-two years ago. According to the custom in Ecuador, he, as the eldest son, was sent abroad, to London, to finish his education. He returned home only to find that he had outgrown the thought and customs of his country. He therefore returned to England, and later, in 1903, came to New York. Here he joined the staff of the Marine Engine Corporation, later merged with the Otis Elevator Company. His chief interest, however, was not in engineering but in art. He was a friend and pupil of Clarence H. White, and for many [pg 97] years devoted every moment of his spare time to artistic creation. In 1917 he cut loose from his his business moorings and embarked on the great adventure of his life. Henceforth until his death he devoted himself wholly to creative work in photography.

“The later years of his life were spent in that part of Manhattan, beyond Dyckman Street, known as Inwood. That section of the Island he very much loved, and many of his pictures were taken in or around those wooded heights overlooking Spuyten Duyvil. These pictures include a series of illustrations to Stephen Phillips' poem, ‘Marpessa.’

“It was in October, 1913, that Mr. Dickson published the first number of Platinum Print, ‘a journal of personal expression.’ Between that date and October, 1917, eleven numbers of this remarkable magazine were published, the last two under the title of Photo-Graphic Art.

“He was one of the founders in 1916 of the Pictorial Photographers of America and was secretary to that organization until 1920. In 1921 he completed the editing of the ‘Poems of the Dance,’ an anthology illustrated by his own photographs, which was published in the same year. At the time of his death he was at work on other projects, which would have been genuine contributions.

We have also been saddened by the death of Richard H. Rice, which occurred last February and cost the country one of its wisest industrial leaders. Becoming manager of the Lynn Works of the General Electric Company during a great strike, he had made them famous for productive cooperation. His methods have been generally copied; and the confidence and support of his twelve thousand workmen and women were due to his devotion and his inviolable sense of justice.

Photography was his refuge from pressing affairs. With the engineer's skill and interest in processes and a keen love of natural beauty, he produced during his last decade half a hundred landscape studies of a reticent and enduring beauty. The scant leisure of his last winter had been spent in preparing these for exhibition, and they remain as a characteristic memorial to an unusual personality.

In this book, our third Pictorial Annual, we offer the choice of our Jury from nearly a thousand prints, selected without regard to membership in the organization and solely with the intention of exhibiting the best that America can produce. We are grateful to all who have contributed, whether successfully or not, for their encouragement and support, often by letter as well as by entries; to the Jury of Selection for their careful, painstaking judgment; to our Committee on Publication for its detailed and arduous work; to our engravers and printers for their preparation and presentation of our material; to all, in fact, who have cooperated in making Pictorial Photography in America for 1922 a good record of current American Photographic Art.

Sixty-five East Fifty-sixth Street,

New York City.