Title: Sintram and His Companions

Author: Freiherr de Friedrich Heinrich Karl La Motte-Fouqué

Author of introduction, etc.: Charlotte M. Yonge

Illustrator: Gordon Browne

Release date: September 1, 2001 [eBook #2824]

Most recently updated: January 27, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sandra Laythorpe, and David Widger

CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Four tales are, it is said, intended by the Author to be appropriate to the Four Seasons: the stern, grave “Sintram”, to winter; the tearful, smiling, fresh “Undine”, to Spring; the torrid deserts of the “Two Captains”, to summer; and the sunset gold of “Aslauga’s Knight”, to autumn. Of these two are before us.

The author of these tales, as well as of many more, was Friedrich, Baron de la Motte Fouque, one of the foremost of the minstrels or tale-tellers of the realm of spiritual chivalry—the realm whither Arthur’s knights departed when they “took the Sancgreal’s holy quest,”—whence Spenser’s Red Cross knight and his fellows came forth on their adventures, and in which the Knight of la Mancha believed, and endeavoured to exist.

La Motte Fouque derived his name and his title from the French Huguenot ancestry, who had fled on the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. His Christian name was taken from his godfather, Frederick the Great, of whom his father was a faithful friend, without compromising his religious principles and practice. Friedrich was born at Brandenburg on February 12, 1777, was educated by good parents at home, served in the Prussian army through disaster and success, took an enthusiastic part in the rising of his country against Napoleon, inditing as many battle-songs as Korner. When victory was achieved, he dedicated his sword in the church of Neunhausen where his estate lay. He lived there, with his beloved wife and his imagination, till his death in 1843.

And all the time life was to him a poet’s dream. He lived in a continual glamour of spiritual romance, bathing everything, from the old deities of the Valhalla down to the champions of German liberation, in an ideal glow of purity and nobleness, earnestly Christian throughout, even in his dealings with Northern mythology, for he saw Christ unconsciously shown in Baldur, and Satan in Loki.

Thus he lived, felt, and believed what he wrote, and though his dramas and poems do not rise above fair mediocrity, and the great number of his prose stories are injured by a certain monotony, the charm of them is in their elevation of sentiment and the earnest faith pervading all. His knights might be Sir Galahad—

“My strength is as the strength of ten,

Because my heart is pure.”

Evil comes to them as something to be conquered, generally as a form of magic enchantment, and his “wondrous fair maidens” are worthy of them. Yet there is adventure enough to afford much pleasure, and often we have a touch of true genius, which has given actual ideas to the world, and precious ones.

This genius is especially traceable in his two masterpieces, Sintram and Undine. Sintram was inspired by Albert Durer’s engraving of the “Knight of Death,” of which we give a presentation. It was sent to Fouque by his friend Edward Hitzig, with a request that he would compose a ballad on it. The date of the engraving is 1513, and we quote the description given by the late Rev. R. St. John Tyrwhitt, showing how differently it may be read.

“Some say it is the end of the strong wicked man, just overtaken by Death and Sin, whom he has served on earth. It is said that the tuft on the lance indicates his murderous character, being of such unusual size. You know the use of that appendage was to prevent blood running down from the spearhead to the hands. They also think that the object under the horse’s off hind foot is a snare, into which the old oppressor is to fall instantly. The expression of the faces may be taken either way: both good men and bad may have hard, regular features; and both good men and bad would set their teeth grimly on seeing Death, with the sands of their life nearly run out. Some say they think the expression of Death gentle, or only admonitory (as the author of “Sintram”); and I have to thank the authoress of the “Heir of Redclyffe” for showing me a fine impression of the plate, where Death certainly had a not ungentle countenance—snakes and all. I think the shouldered lance, and quiet, firm seat on horseback, with gentle bearing on the curb-bit, indicate grave resolution in the rider, and that a robber knight would have his lance in rest; then there is the leafy crown on the horse’s head; and the horse and dog move on so quietly, that I am inclined to hope the best for the Ritter.”

Musing on the mysterious engraving, Fouque saw in it the life-long companions of man, Death and Sin, whom he must defy in order to reach salvation; and out of that contemplation rose his wonderful romance, not exactly an allegory, where every circumstance can be fitted with an appropriate meaning, but with the sense of the struggle of life, with external temptation and hereditary inclination pervading all, while Grace and Prayer aid the effort. Folko and Gabrielle are revived from the Magic Ring, that Folko may by example and influence enhance all higher resolutions; while Gabrielle, in all unconscious innocence, awakes the passions, and thus makes the conquest the harder.

It is within the bounds of possibility that the similarities of folk- lore may have brought to Fouque’s knowledge the outline of the story which Scott tells us was the germ of “Guy Mannering”; where a boy, whose horoscope had been drawn by an astrologer, as likely to encounter peculiar trials at certain intervals, actually had, in his twenty-first year, a sort of visible encounter with the Tempter, and came off conqueror by his strong faith in the Bible. Sir Walter, between reverence and realism, only took the earlier part of the story, but Fouque gives us the positive struggle, and carries us along with the final victory and subsequent peace. His tale has had a remarkable power over the readers. We cannot but mention two remarkable instances at either end of the scale. Cardinal Newman, in his younger days, was so much overcome by it that he hurried out into the garden to read it alone, and returned with traces of emotion in his face. And when Charles Lowder read it to his East End boys, their whole minds seemed engrossed by it, and they even called certain spots after the places mentioned. Imagine the Rocks of the Moon in Ratcliff Highway!

May we mention that Miss Christabel Coleridge’s “Waynflete” brings something of the spirit and idea of “Sintram” into modern life?

“Undine” is a story of much lighter fancy, and full of a peculiar grace, though with a depth of melancholy that endears it. No doubt it was founded on the universal idea in folk-lore of the nixies or water-spirits, one of whom, in Norwegian legend, was seen weeping bitterly because of the want of a soul. Sometimes the nymph is a wicked siren like the Lorelei; but in many of these tales she weds an earthly lover, and deserts him after a time, sometimes on finding her diving cap, or her seal-skin garment, which restores her to her ocean kindred, sometimes on his intruding on her while she is under a periodical transformation, as with the fairy Melusine, more rarely if he becomes unfaithful.

There is a remarkable Cornish tale of a nymph or mermaiden, who thus vanished, leaving a daughter who loved to linger on the beach rather than sport with other children. By and by she had a lover, but no sooner did he show tokens of inconstancy, than the mother came up from the sea and put him to death, when the daughter pined away and died. Her name was Selina, which gives the tale a modern aspect, and makes us wonder if the old tradition can have been modified by some report of Undine’s story.

There was an idea set forth by the Rosicrucians of spirits abiding in the elements, and as Undine represented the water influences, Fouque’s wife, the Baroness Caroline, wrote a fairly pretty story on the sylphs of fire. But Undine’s freakish playfulness and mischief as an elemental being, and her sweet patience when her soul is won, are quite original, and indeed we cannot help sharing, or at least understanding, Huldbrand’s beginning to shrink from the unearthly creature to something of his own flesh and blood. He is altogether unworthy, and though in this tale there is far less of spiritual meaning than in Sintram, we cannot but see that Fouque’s thought was that the grosser human nature is unable to appreciate what is absolutely pure and unearthly.

C. M. YONGE.

In the high castle of Drontheim many knights sat assembled to hold council for the weal of the realm; and joyously they caroused together till midnight around the huge stone table in the vaulted hall. A rising storm drove the snow wildly against the rattling windows; all the oak doors groaned, the massive locks shook, the castle-clock slowly and heavily struck the hour of one. Then a boy, pale as death, with disordered hair and closed eyes, rushed into the hall, uttering a wild scream of terror. He stopped beside the richly carved seat of the mighty Biorn, clung to the glittering knight with both his hands, and shrieked in a piercing voice, “Knight and father! father and knight! Death and another are closely pursuing me!”

An awful stillness lay like ice on the whole assembly, save that the boy screamed ever the fearful words. But one of Biorn’s numerous retainers, an old esquire, known by the name of Rolf the Good, advanced towards the terrified child, took him in his arms, and half chanted this prayer: “O Father, help Thy servant! I believe, and yet I cannot believe.” The boy, as if in a dream, at once loosened his hold of the knight; and the good Rolf bore him from the hall unresisting, yet still shedding hot tears and murmuring confused sounds.

The lords and knights looked at one another much amazed, until the mighty Biorn said, wildly and fiercely laughing, “Marvel not at that strange boy. He is my only son; and has been thus since he was five years old: he is now twelve. I am therefore accustomed to see him so; though, at the first, I too was disquieted by it. The attack comes upon him only once in the year, and always at this same time. But forgive me for having spent so many words on my poor Sintram, and let us pass on to some worthier subject for our discourse.”

Again there was silence for a while; then whisperingly and doubtfully single voices strove to renew their broken-off discourse, but without success. Two of the youngest and most joyous began a roundelay; but the storm howled and raged so wildly without, that this too was soon interrupted. And now they all sat silent and motionless in the lofty hall; the lamp flickered sadly under the vaulted roof; the whole party of knights looked like pale, lifeless images dressed up in gigantic armour.

Then arose the chaplain of the castle of Drontheim, the only priest among the knightly throng, and said, “Dear Lord Biorn, our eyes and thoughts have all been directed to you and your son in a wonderful manner; but so it has been ordered by the providence of God. You perceive that we cannot withdraw them; and you would do well to tell us exactly what you know concerning the fearful state of the boy. Perchance, the solemn tale, which I expect from you, might do good to this disturbed assembly.”

Biorn cast a look of displeasure on the priest, and answered, “Sir chaplain, you have more share in the history than either you or I could desire. Excuse me, if I am unwilling to trouble these light- hearted warriors with so rueful a tale.”

But the chaplain approached nearer to the knight, and said, in a firm yet very mild tone, “Dear lord, hitherto it rested with you alone to relate, or not to relate it; but now that you have so strangely hinted at the share which I have had in your son’s calamity, I must positively demand that you will repeat word for word how everything came to pass. My honour will have it so, and that will weigh with you as much as with me.”

In stern compliance Biorn bowed his haughty head, and began the following narration. “This time seven years I was keeping the Christmas feast with my assembled followers. We have many venerable old customs which have descended to us by inheritance from our great forefathers; as, for instance, that of placing a gilded boar’s head on the table, and making thereon knightly vows of daring and wondrous deeds. Our chaplain here, who used then frequently to visit me, was never a friend to keeping up such traditions of the ancient heathen world. Such men as he were not much in favour in those olden times.”

“My excellent predecessors,” interrupted the chaplain, “belonged more to God than to the world, and with Him they were in favour. Thus they converted your ancestors; and if I can in like manner be of service to you, even your jeering will not vex me.”

With looks yet darker, and a somewhat angry shudder, the knight resumed: “Yes, yes; I know all your promises and threats of an invisible Power, and how they are meant persuade us to part more readily with whatever of this world’s goods we may possess. Once, ah, truly, once I too had such! Strange!—Sometimes it seems to me as though ages had passed over since then, and as if I were alone the survivor, so fearfully has everything changed. But now I bethink me, that the greater part of this noble company knew me in my happiness, and have seen my wife, my lovely Verena.”

He pressed his hands on his eyes, and it seemed as though he wept. The storm had ceased; the soft light of the moon shone through the windows, and her beams played on his wild features. Suddenly he started up, so that his heavy armour rattled with a fearful sound, and he cried out in a thundering voice, “Shall I turn monk, as she has become a nun? No, crafty priest; your webs are too thin to catch flies of my sort.”

“I have nothing to do with webs,” said the chaplain. “In all openness and sincerity have I put heaven and hell before you during the space of six years; and you gave full consent to the step which the holy Verena took. But what all that has to do with your son’s sufferings I know not, and I wait for your narration.”

“You may wait long enough,” said Biorn, with a sneer. “Sooner shall—”

“Swear not!” said the chaplain in a loud commanding tone, and his eyes flashed almost fearfully.

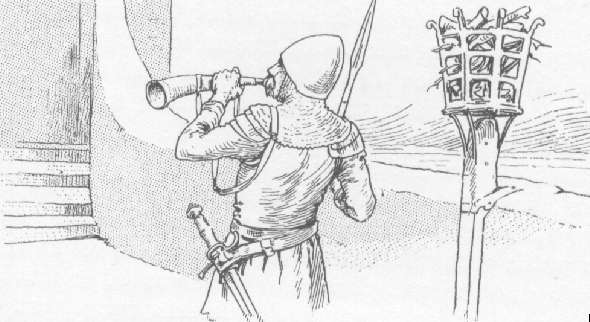

“Hurra!” cried Biorn, in wild affright; “hurra! Death and his companion are loose!” and he dashed madly out of the chamber and down the steps. The rough and fearful notes of his horn were heard summoning his retainers; and presently afterwards the clatter of horses’ feet on the frozen court-yard gave token of their departure. The knights retired, silent and shuddering; while the chaplain remained alone at the huge stone table, praying.

After some time the good Rolf returned with slow and soft steps, and started with surprise at finding the hall deserted. The chamber where he had been occupied in quieting and soothing the unhappy child was in so distant a part of the castle that he had heard nothing of the knight’s hasty departure. The chaplain related to him all that had passed, and then said, “But, my good Rolf, I much wish to ask you concerning those strange words with which you seemed to lull poor Sintram to rest. They sounded like sacred words, and no doubt they are; but I could not understand them. ‘I believe, and yet I cannot believe.’”

“Reverend sir,” answered Rolf, “I remember that from my earliest years no history in the Gospels has taken such hold of me as that of the child possessed with a devil, which the disciples were not able to cast out; but when our Saviour came down from the mountain where He had been transfigured, He broke the bonds wherewith the evil spirit had held the miserable child bound. I always felt as if I must have known and loved that boy, and been his play-fellow in his happy days; and when I grew older, then the distress of the father on account of his lunatic son lay heavy at my heart. It must surely have all been a foreboding of our poor young Lord Sintram, whom I love as if he were my own child; and now the words of the weeping father in the Gospel often come into my mind,—‘Lord, I believe; help Thou my unbelief;’ and something similar I may very likely have repeated to-day as a chant or a prayer. Reverend father, when I consider how one dreadful imprecation of the father has kept its withering hold on the son, all seems dark before me; but, God be praised! my faith and my hope remain above.”

“Good Rolf,” said the priest, “I cannot clearly understand what you say about the unhappy Sintram; for I do not know when and how this affliction came upon him. If no oath or solemn promise bind you to secrecy, will you make known to me all that is connected with it?”

“Most willingly,” replied Rolf. “I have long desired to have an opportunity of so doing; but you have been almost always separated from us. I dare not now leave the sleeping boy any longer alone; and to-morrow, at the earliest dawn, I must take him to his father. Will you come with me, dear sir, to our poor Sintram?”

The chaplain at once took up the small lamp which Rolf had brought with him, and they set off together through the long vaulted passages. In the small distant chamber they found the poor boy fast asleep. The light of the lamp fell strangely on his very pale face. The chaplain stood gazing at him for some time, and at length said: “Certainly from his birth his features were always sharp and strongly marked, but now they are almost fearfully so for such a child; and yet no one can help having a kindly feeling towards him, whether he will or not.”

“Most true, dear sir,” answered Rolf. And it was evident how his whole heart rejoiced at any word which betokened affection for his beloved young lord. Thereupon he placed the lamp where its light could not disturb the boy, and seating himself close by the priest, he began to speak in the following terms:—“During that Christmas feast of which my lord was talking to you, he and his followers discoursed much concerning the German merchants, and the best means of keeping down the increasing pride and power of the trading-towns. At length Biorn laid his impious hand on the golden boar’s head, and swore to put to death without mercy every German trader whom fate, in what way soever, might bring alive into his power. The gentle Verena turned pale, and would have interposed—but it was too late, the bloody word was uttered. And immediately afterwards, as though the great enemy of souls were determined at once to secure with fresh bonds the vassal thus devoted to him, a warder came into the hall to announce that two citizens of a trading-town in Germany, an old man and his son, had been shipwrecked on this coast, and were now within the gates, asking hospitality of the lord of the castle. The knight could not refrain from shuddering; but he thought himself bound by his rash vow and by that accursed heathenish golden boar. We, his retainers, were commanded to assemble in the castle-yard, armed with sharp spears, which were to be hurled at the defenceless strangers at the first signal made to us. For the first, and I trust the last time in my life, I said ‘No’ to the commands of my lord; and that I said in a loud voice, and with the heartiest determination. The Almighty, who alone knows whom He will accept and whom He will reject, armed me with resolution and strength. And Biorn might perceive whence the refusal of his faithful old servant arose, and that it was worthy of respect. He said to me, half in anger and half in scorn: ‘Go up to my wife’s apartments; her attendants are running to and fro, perhaps she is ill. Go up, Rolf the Good, I say to thee, and so women shall be with women.’ I thought to myself, ‘Jeer on, then;’ and I went silently the way that he had pointed out to me. On the stairs there met me two strange and right fearful beings, whom I had never seen before; and I know not how they got into the castle. One of them was a great tall man, frightfully pallid and thin; the other was a dwarf-like man, with a most hideous countenance and features. Indeed, when I collected my thoughts and looked carefully at him, it appeared to me—”

Low moanings and convulsive movements of the boy here interrupted the narrative. Rolf and his chaplain hastened to his bedside, and perceived that his countenance wore an expression of fearful agony, and that he was struggling in vain to open his eyes. The priest made the Sign of the Cross over him, and immediately peace seemed to be restored, and his sleep again became quiet: they both returned softly to their seats.

“You see,” said Rolf, “that it will not do to describe more closely those two awful beings. Suffice it to say, that they went down into the court-yard, and that I proceeded to my lady’s apartments. I found the gentle Verena almost fainting with terror and overwhelming anxiety, and I hastened to restore her with some of those remedies which I was able to apply by my skill, through God’s gift and the healing virtues of herbs and minerals. But scarcely had she recovered her senses, when, with that calm holy power which, as you know, is hers, she desired me to conduct her down to the court-yard, saying that she must either put a stop to the fearful doings of this night, or herself fall a sacrifice. Our way took us by the little bed of the sleeping Sintram. Alas! hot tears fell from my eyes to see how evenly his gentle breath then came and went, and how sweetly he smiled in his peaceful slumbers.”

The old man put his hands to his eyes, and wept bitterly; but soon he resumed his sad story. “As we approached the lowest window of the staircase, we could hear distinctly the voice of the elder merchant; and on looking out, the light of the torches showed me his noble features, as well as the bright youthful countenance of his son. ‘I take Almighty God to witness,’ cried he, ‘that I had no evil thought against this house! But surely I must have fallen unawares amongst heathens; it cannot be that I am in a Christian knight’s castle; and if you are indeed heathens, then kill us at once. And thou, my beloved son, be patient and of good courage; in heaven we shall learn wherefore it could not be otherwise.’ I thought I could see those two fearful ones amidst the throng of retainers. The pale one had a huge curved sword in his hand, the little one held a spear notched in a strange fashion. Verena tore open the window, and cried in silvery tones through the wild night, ‘My dearest lord and husband, for the sake of your only child, have pity on those harmless men! Save them from death, and resist the temptation of the evil spirit.’ The knight answered in his fierce wrath—but I cannot repeat his words. He staked his child on the desperate cast; he called Death and the Devil to see that he kept his word:—but hush! the boy is again moaning. Let me bring the dark tale quickly to a close. Biorn commanded his followers to strike, casting on them those fierce looks which have gained him the title of Biorn of the Fiery Eyes; while at the same time the two frightful strangers bestirred themselves very busily. Then Verena called out, with piercing anguish, ‘Help, O God, my Saviour!’ Those two dreadful figures disappeared; and the knight and his retainers, as if seized with blindness, rushed wildly one against the other, but without doing injury to themselves, or yet being able to strike the merchants, who ran so close a risk. They bowed reverently towards Verena, and with calm thanksgivings departed through the castle- gates, which at that moment had been burst open by a violent gust of wind, and now gave a free passage to any who would go forth. The lady and I were yet standing bewildered on the stairs, when I fancied I saw the two fearful forms glide close by me, but mist-like and unreal. Verena called to me: ‘Rolf, did you see a tall pale man, and a little hideous one with him, pass just now up the staircase?’ I flew after them; and found, alas, the poor boy in the same state in which you saw him a few hours ago. Ever since, the attack has come on him regularly at this time, and he is in all respects fearfully changed. The lady of the castle did not fail to discern the avenging hand of Heaven in this calamity; and as the knight, her husband, instead of repenting, ever became more truly Biorn of the Fiery Eyes, she resolved, in the walls of a cloister, by unremitting prayer, to obtain mercy in time and eternity for herself and her unhappy child.”

Rolf was silent; and the chaplain, after some thought, said: “I now understand why, six years ago, Biorn confessed his guilt to me in general words, and consented that his wife should take the veil. Some faint compunction must then have stirred within him, and perhaps may stir him yet. At any rate it was impossible that so tender a flower as Verena could remain longer in so rough keeping. But who is there now to watch over and protect our poor Sintram?”

“The prayer of his mother,” answered Rolf. “Reverend sir, when the first dawn of day appears, as it does now, and when the morning breeze whispers through the glancing window, they ever bring to my mind the soft beaming eyes of my lady, and I again seem to hear the sweet tones of her voice. The holy Verena is, next to God, our chief aid.”

“And let us add our devout supplications to the Lord,” said the chaplain; and he and Rolf knelt in silent and earnest prayer by the bed of the pale sufferer, who began to smile in his dreams.

The rays of the sun shining brightly into the room awoke Sintram, and raising himself up, he looked angrily at the chaplain, and said, “So there is a priest in the castle! And yet that accursed dream continues to torment me even in his very presence. Pretty priest he must be!”

“My child,” answered the chaplain in the mildest tone, “I have prayed for thee most fervently, and I shall never cease doing so—but God alone is Almighty.”

“You speak very boldly to the son of the knight Biorn,” cried Sintram. “‘My child!’ If those horrible dreams had not been again haunting me, you would make me laugh heartily.”

“Young Lord Sintram,” said the chaplain, “I am by no means surprised that you do not know me again; for in truth, neither do I know you again.” And his eyes filled with tears as he spoke.

The good Rolf looked sorrowfully in the boy’s face, saying, “Ah, my dear young master, you are so much better than you would make people believe. Why do you that? Your memory is so good, that you must surely recollect your kind old friend the chaplain, who used formerly to be constantly at the castle, and to bring you so many gifts— bright pictures of saints, and beautiful songs?”

“I know all that very well,” replied Sintram thoughtfully. “My sainted mother was alive in those days.”

“Our gracious lady is still living, God be praised,” said the good Rolf.

“But she does not live for us, poor sick creatures that we are!” cried Sintram. “And why will you not call her sainted? Surely she knows nothing about my dreams?”

“Yes, she does know of them,” said the chaplain; “and she prays to God for you. But take heed, and restrain that wild, haughty temper of yours. It might, indeed, come to pass that she would know nothing about your dreams, and that would be if your soul were separated from your body; and then the holy angels also would cease to know anything of you.”

Sintram fell back on his bed as if thunderstruck; and Rolf said, with a gentle sigh, “You should not speak so severely to my poor sick child, reverend sir.”

The boy sat up, and with tearful eyes he turned caressingly towards the chaplain: “Let him do as he pleases, you good, tender-hearted Rolf; he knows very well what he is about. Would you reprove him if I were slipping down a snow-cleft, and he caught me up roughly by the hair of my head?”

The priest looked tenderly at him, and would have spoken his holy thoughts, when Sintram suddenly sprang off the bed and asked after his father. As soon as he heard of the knight’s departure, he would not remain another hour in the castle; and put aside the fears of the chaplain and the old esquire, lest a rapid journey should injure his hardly restored health, by saying to them, “Believe me, reverend sir, and dear old Rolf, if I were not subject to these hideous dreams, there would not be a bolder youth in the whole world; and even as it is, I am not so far behind the very best. Besides, till another year has passed, my dreams are at an end.”

On his somewhat imperious sign Rolf brought out the horses. The boy threw himself boldly into the saddle, and taking a courteous leave of the chaplain, he dashed along the frozen valley that lay between the snow-clad mountains. He had not ridden far, in company with his old attendant, when he heard a strange indistinct sound proceeding from a neighbouring cleft in the rock; it was partly like the clapper of a small mill, but mingled with that were hollow groans and other tones of distress. Thither they turned their horses, and a wonderful sight showed itself to them.

A tall man, deadly pale, in a pilgrim’s garb, was striving with violent though unsuccessful efforts, to work his way out of the snow and to climb up the mountain; and thereby a quantity of bones, which were hanging loosely all about his garments, rattled one against the other, and caused the mysterious sound already mentioned. Rolf, much terrified, crossed himself, while the bold Sintram called out to the stranger, “What art thou doing there? Give an account of thy solitary labours.”

“I live in death,” replied that other one with a fearful grin.

“Whose are those bones on thy clothes?”

“They are relics, young sir.”

“Art thou a pilgrim?”

“Restless, quietless, I wander up and down.”

“Thou must not perish here in the snow before my eyes.”

“That I will not.”

“Thou must come up and sit on my horse.”

“That I will.” And all at once he started up out of the snow with surprising strength and agility, and sat on the horse behind Sintram, clasping him tight in his long arms. The horse, startled by the rattling of the bones, and as if seized with madness, rushed away through the most trackless passes. The boy soon found himself alone with his strange companion; for Rolf, breathless with fear, spurred on his horse in vain, and remained far behind them. From a snowy precipice the horse slid, without falling, into a narrow gorge, somewhat indeed exhausted, yet continuing to snort and foam as before, and still unmastered by the boy. Yet his headlong course being now changed into a rough irregular trot, Sintram was able to breathe more freely, and to begin the following discourse with his unknown companion.

“Draw thy garment closer around thee, thou pale man, so the bones will not rattle, and I shall be able to curb my horse.”

“It would be of no avail, boy; it would be of no avail. The bones must rattle.”

“Do not clasp me so tight with thy long arms, they are so cold.”

“It cannot be helped, boy; it cannot be helped. Be content. For my long cold arms are not pressing yet on thy heart.”

“Do not breathe on me so with thy icy breath. All my strength is departing.”

“I must breathe, boy; I must breathe. But do not complain. I am not blowing thee away.”

The strange dialogue here came to an end; for to Sintram’s surprise he found himself on an open plain, over which the sun was shining brightly, and at no great distance before him he saw his father’s castle. While he was thinking whether he might invite the unearthly pilgrim to rest there, this one put an end to his doubts by throwing himself suddenly off the horse, whose wild course was checked by the shock. Raising his forefinger, he said to the boy, “I know old Biorn of the Fiery Eyes well; perhaps but too well. Commend me to him. It will not need to tell him my name; he will recognize me at the description.” So saying, the ghastly stranger turned aside into a thick fir-wood, and disappeared rattling amongst the tangled branches.

Slowly and thoughtfully Sintram rode on towards his father’s castle, his horse now again quiet and altogether exhausted. He scarcely knew how much he ought to relate of his wonderful journey, and he also felt oppressed with anxiety for the good Rolf, who had remained so far behind. He found himself at the castle-gate sooner than he had expected; the drawbridge was lowered, the doors were thrown open; an attendant led the youth into the great hall, where Biorn was sitting all alone at a huge table, with many flagons and glasses before him, and suits of armour ranged on either side of him. It was his daily custom, by way of company, to have the armour of his ancestors, with closed visors, placed all round the table at which he sat. The father and son began conversing as follows:

“Where is Rolf?”

“I do not know, father; he left me in the mountains.”

“I will have Rolf shot if he cannot take better care than that of my only child.”

“Then, father, you will have your only child shot at the same time, for without Rolf I cannot live; and if even one single dart is aimed at him, I will be there to receive it, and to shield his true and faithful heart.”

“So!—Then Rolf shall not be shot, but he shall be driven from the castle.”

“In that case, father, you will see me go away also; and I will give myself up to serve him in forests, in mountains, in caves.”

“So!—Well, then, Rolf must remain here.”

“That is just what I think, father.”

“Were you riding quite alone?”

“No, father; but with a strange pilgrim. He said that he knew you very well—perhaps too well.” And thereupon Sintram began to relate and to describe all that had passed with the pale man.

“I know him also very well,” said Biorn. “He is half crazed and half wise, as we sometimes are astonished at seeing that people can be. But do thou, my boy, go to rest after thy wild journey. I give you my word that Rolf shall be kindly received if he arrive here; and that if he do not come soon, he shall be sought for in the mountains.”

“I trust to your word, father,” said Sintram, half humble, half proud; and he did after the command of the grim lord of the castle.

Towards evening Sintram awoke. He saw the good Rolf sitting at his bedside, and looked up in the old man’s kind face with a smile of unusually innocent brightness. But soon again his dark brows were knit, and he asked, “How did my father receive you, Rolf? Did he say a harsh word to you?”

“No, my dear young lord, he did not; indeed he did not speak to me at all. At first he looked very wrathful; but he checked himself, and ordered a servant to bring me food and wine to refresh me, and afterwards to take me to your room.”

“He might have kept his word better. But he is my father, and I must not judge him too hardly. I will now go down to the evening meal.” So saying, he sprang up and threw on his furred mantle.

But Rolf stopped him, and said, entreatingly: “My dear young master, you would do better to take your meal to-day alone here in your own apartment; for there is a guest with your father, in whose company I should be very sorry to see you. If you will remain here, I will entertain you with pleasant tales and songs.”

“There is nothing in the world which I should like better, dear Rolf,” answered Sintram; “but it does not befit me to shun any man. Tell me, whom should I find with my father?”

“Alas!” said the old man, “you have already found him in the mountain. Formerly, when I used to ride about the country with Biorn, we often met with him, but I was forbidden to tell you anything about him; and this is the first time that he has ever come to the castle.”

“The crazy pilgrim!” replied Sintram; and he stood awhile in deep thought, as if considering the matter. At last, rousing himself, he said, “Dear old friend, I would most willingly stay here this evening all alone with you and your stories and songs, and all the pilgrims in the world should not entice me from this quiet room. But one thing must be considered. I feel a kind of dread of that pale, tall man; and by such fears no knight’s son can ever suffer himself to be overcome. So be not angry, dear Rolf, if I determine to go and look that strange palmer in the face.” And he shut the door of the chamber behind him, and with firm and echoing steps proceeded to the hall.

The pilgrim and the knight were sitting opposite to each other at the great table, on which many lights were burning; and it was fearful, amongst all the lifeless armour, to see those two tall grim men move, and eat, and drink.

As the pilgrim looked up on the boy’s entrance, Biorn said: “You know him already: he is my only child, and fellow-traveller this morning.”

The palmer fixed an earnest look on Sintram, and answered, shaking his head, “I know not what you mean.”

Then the boy burst forth, impatiently, “It must be confessed that you deal very unfairly by us! You say that you know my father but too much, and now it seems that you know me altogether too little. Look me in the face: who allowed you to ride on his horse, and in return had his good steed driven almost wild? Speak, if you can!”

Biorn smiled, shaking his head, but well pleased, as was his wont, with his son’s wild behaviour; while the pilgrim shuddered as if terrified and overcome by some fearful irresistible power. At length, with a trembling voice, he said these words: “Yes, yes, my dear young lord, you are surely quite right; you are perfectly right in everything which you may please to assert.”

Then the lord of the castle laughed aloud, and said: “Why, thou strange pilgrim, what is become of all thy wonderfully fine speeches and warnings now? Has the boy all at once struck thee dumb and powerless? Beware, thou prophet-messenger, beware!”

But the palmer cast a fearful look on Biorn, which seemed to quench the light of his fiery eyes, and said solemnly, in a thundering voice, “Between me and thee, old man, the case stands quite otherwise. We have nothing to reproach each other with. And now suffer me to sing a song to you on the lute.” He stretched out his hand, and took down from the wall a forgotten and half-strung lute, which was hanging there; and, with surprising skill and rapidity, having put it in a state fit for use, he struck some chords, and raised this song to the low melancholy tones of the instrument:

“The flow’ret was mine own, mine own,

But I have lost its fragrance

rare,

And knightly name and freedom fair,

Through sin, through

sin alone.

The flow’ret was thine own, thine own,

Why cast away what thou didst

win?

Thou knight no more, but slave of sin,

Thou’rt fearfully

alone!”

“Have a care!” shouted he at the close in a pealing voice, as he pulled the strings so mightily that they all broke with a clanging wail, and a cloud of dust rose from the old lute, which spread round him like a mist.

Sintram had been watching him narrowly whilst he was singing, and more and more did he feel convinced that it was impossible that this man and his fellow-traveller of the morning could be one and the same. Nay, the doubt rose to certainty, when the stranger again looked round at him with the same timid, anxious air, and with many excuses and low reverences hung the lute in its old place, and then ran out of the hall as if bewildered with terror, in strange contrast with the proud and stately bearing which he had shown to Biorn.

The eyes of the boy were now directed to his father, and he saw that he had sunk back senseless in his seat, as if struck by a blow. Sintram’s cries called Rolf and other attendants into the hall; and only by great labour did their united efforts awake the lord of the castle. His looks were still wild and disordered; but he allowed himself to be taken to rest, quiet and yielding.

An illness followed this sudden attack; and during the course of it the stout old knight, in the midst of his delirious ravings, did not cease to affirm confidently that he must and should recover. He laughed proudly when his fever-fits came on, and rebuked them for daring to attack him so needlessly. Then he murmured to himself, “That was not the right one yet; there must still be another one out in the cold mountains.”

Always at such words Sintram involuntarily shuddered; they seemed to strengthen his notion that he who had ridden with him, and he who had sat at table in the castle, were two quite distinct persons; and he knew not why, but this thought was inexpressibly awful to him. Biorn recovered, and appeared to have entirely forgotten his adventure with the palmer. He hunted in the mountains; he carried on his usual wild warfare with his neighbours; and Sintram, as he grew up, became his almost constant companion; whereby each year a fearful strength of body and spirit was unfolded in the youth. Every one trembled at the sight of his sharp pallid features, his dark rolling eyes, his tall, muscular, and somewhat lean form; and yet no one hated him—not even those whom he distressed or injured in his wildest humours. This might arise in part out of regard to old Rolf, who seldom left him for long, and who always held a softening influence over him; but also many of those who had known the Lady Verena while she still lived in the world affirmed that a faint reflection of her heavenly expression floated over the very unlike features of her son, and that by this their hearts were won.

Once, just at the beginning of spring, Biorn and his son were hunting in the neighbourhood of the sea-coast, over a tract of country which did not belong to them; drawn thither less by the love of sport than by the wish of bidding defiance to a chieftain whom they detested, and thus exciting a feud. At that season of the year, when his winter dreams had just passed off, Sintram was always unusually fierce and disposed for warlike adventures. And this day he was enraged at the chieftain for not coming in arms from his castle to hinder their hunting; and he cursed, in the wildest words, his tame patience and love of peace. Just then one of his wild young companions rushed towards him, shouting joyfully: “Be content my dear young lord! I will wager that all is coming about as we and you wish; for as I was pursuing a wounded deer down to the sea-shore, I saw a sail and a vessel filled with armed men making for the shore. Doubtless your enemy purposes to fall upon you from the coast.”

Joyfully and secretly Sintram called all his followers together, being resolved this time to take the combat on himself alone, and then to rejoin his father, and astonish him with the sight of captured foes and other tokens of victory.

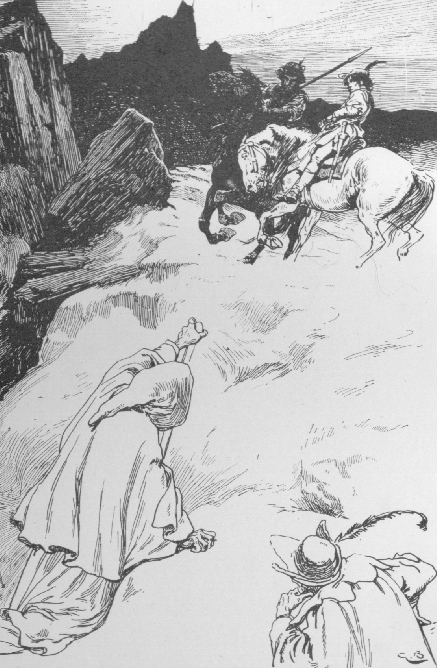

The hunters, thoroughly acquainted with every cliff and rock on the coast, hid themselves round the landing-place; and soon the strange vessel hove nearer with swelling sails, till at length it came to anchor, and its crew began to disembark in unsuspicious security. At the head of them appeared a knight of high degree, in blue steel armour richly inlaid with gold. His head was bare, for he carried his costly golden helmet hanging on his left arm. He looked royally around him; and his countenance, which dark brown locks shaded, was pleasant to behold; and a well-trimmed moustache fringed his mouth, from which, as he smiled, gleamed forth two rows of pearl-white teeth.

A feeling came across Sintram that he must already have seen this knight somewhere; and he stood motionless for a few moments. But suddenly he raised his hand, to make the agreed signal of attack. In vain did the good Rolf, who had just succeeded in getting up to him, whisper in his ear that these could not be the foes whom he had taken them for, but that they were unknown, and certainly high and noble strangers.

“Let them be who they may,” replied the wild youth, “they have enticed me here to wait, and they shall pay the penalty of thus fooling me. Say not another word, if you value your life.” And immediately he gave the signal, a thick shower of javelins followed from all sides, and the Norwegian warriors rushed forth with flashing swords. They found their foes as brave, or somewhat braver, than they could have desired. More fell on the side of those who made than of those who received the assault; and the strangers appeared to understand surprisingly the Norwegian manner of fighting. The knight in steel armour had not in his haste put on his helmet; but it seemed as if he in no wise needed such protection, for his good sword afforded him sufficient defence even against the spears and darts which were incessantly hurled at him, as with rapid skill he received them on the shining blade, and dashed them far away, shivered into fragments.

Sintram could not at the first onset penetrate to where this shining hero was standing, as all his followers, eager after such a noble prey, thronged closely round him; but now the way was cleared enough for him to spring towards the brave stranger, shouting a war-cry, and brandishing his sword above his head.

“Gabrielle!” cried the knight, as he dexterously parried the heavy blow which was descending, and with one powerful sword-thrust he laid the youth prostrate on the ground; then placing his knee on Sintram’s breast, he drew forth a flashing dagger, and held it before his eyes as he lay astonished. All at once the men-at-arms stood round like walls. Sintram felt that no hope remained for him. He determined to die as it became a bold warrior; and without giving one sign of emotion, he looked on the fatal weapon with a steady gaze.

As he lay with his eyes cast upwards, he fancied that there appeared suddenly from heaven a wondrously beautiful female form in a bright attire of blue and gold. “Our ancestors told truly of the Valkyrias,” murmured he. “Strike, then, thou unknown conqueror.”

But with this the knight did not comply, neither was it a Valkyria who had so suddenly appeared, but the beautiful wife of the stranger, who, having advanced to the high edge of the vessel, had thus met the upraised look of Sintram.

“Folko,” cried she, in the softest tone, “thou knight without reproach! I know that thou sparest the vanquished.”

The knight sprang up, and with courtly grace stretched out his hand to the conquered youth, saying, “Thank the noble lady of Montfaucon for your life and liberty. But if you are so totally devoid of all goodness as to wish to resume the combat, here am I; let it be yours to begin.”

Sintram sank, deeply ashamed, on his knees, and wept; for he had often heard speak of the high renown of the French knight Folko of Montfaucon, who was related to his father’s house, and of the grace and beauty of his gentle lady Gabrielle.

The Lord of Montfaucon looked with astonishment at his strange foe; and as he gazed on him more and more, recollections arose in his mind of that northern race from whom he was descended, and with whom he had always maintained friendly relations. A golden bear’s claw, with which Sintram’s cloak was fastened, at length made all clear to him.

“Have you not,” said he, “a valiant and far-famed kinsman, called the Sea-king Arinbiorn, who carries on his helmet golden vulture-wings? And is not your father the knight Biorn? For surely the bear’s claw on your mantle must be the cognisance of your house.”

Sintram assented to all this, in deep and humble shame.

The Knight of Montfaucon raised him from the ground, and said gravely, yet gently, “We are, then, of kin the one to the other; but I could never have believed that any one of our noble house would attack a peaceful man without provocation, and that, too, without giving warning.”

“Slay me at once,” answered Sintram, “if indeed I am worthy to die by so noble hands. I can no longer endure the light of day.”

“Because you have been overcome?” asked Montfaucon. Sintram shook his head.

“Or is it, rather, because you have committed an unknightly action?”

The glow of shame that overspread the youth’s countenance said yes to this.

“But you should not on that account wish to die,” continued Montfaucon. “You should rather wish to live, that you may prove your repentance, and make your name illustrious by many noble deeds; for you are endowed with a bold spirit and with strength of limb, and also with the eagle-glance of a chieftain. I should have made you a knight this very hour, if you had borne yourself as bravely in a good cause as you have just now in a bad. See to it, that I may do it soon. You may yet become a vessel of high honour.”

A joyous sound of shawms and silver rebecks interrupted his discourse. The lady Gabrielle, bright as the morning, had now come down from the ship, surrounded by her maidens; and, instructed in a few words by Folko who was his late foe, she took the combat as some mere trial of arms, saying, “You must not be cast down, noble youth, because my wedded lord has won the prize; for be it known to you, that in the whole world there is but one knight who can boast of not having been overcome by the Baron of Montfaucon. And who can say,” continued she, sportively, “whether even that would have happened, had he not set himself to win back the magic ring from me, his lady- love, destined to him, as well by the choice of my own heart as by the will of Heaven!”

Folko, smiling, bent his head over the snow-white hand of his lady; and then bade the youth conduct them to his father’s castle.

Rolf took upon himself to see to the disembarking of the horses and valuables of the strangers, filled with joy at the thought that an angel in woman’s form had appeared to soften his beloved young master, and perhaps even to free him from that early curse.

Sintram sent messengers in all directions to seek for his father, and to announce to him the arrival of his noble guests. They therefore found the old knight in his castle, with everything prepared for their reception. Gabrielle could not enter the vast dark-looking building without a slight shudder, which was increased when she saw the rolling fiery eyes of its lord; even the pale, dark-haired Sintram seemed to her very fearful; and she sighed to herself, “Oh! what an awful abode have you brought me to visit, my knight! Would that we were once again in my sunny Gascony, or in your knightly Normandy!”

But the grave yet courteous reception, the deep respect paid to her grace and beauty, and to the high fame of Folko, helped to re-assure her; and soon her bird-like pleasure in novelties was awakened through the strange significant appearance of this new world. And besides, it could only be for a passing moment that any womanly fears found a place in her breast when her lord was near at hand, for well did she know what effectual protection that brave Baron was ever ready to afford to all those who were dear to him, or committed to his charge.

Soon afterwards Rolf passed through the great hall in which Biorn and his guests were seated, conducting their attendants, who had charge of the baggage, to their rooms. Gabrielle caught sight of her favourite lute, and desired a page to bring it to her, that she might see if the precious instrument had been injured by the sea-voyage. As she bent over it with earnest attention, and her taper fingers ran up and down the strings, a smile, like the dawn of spring, passed over the dark countenances of Biorn and his son; and both said, with an involuntary sigh, “Ah! if you would but play on that lute, and sing to it! It would be but too beautiful!” The lady looked up at them, well pleased, and smiling her assent, she began this song:—

“Songs and flowers are returning,

And radiant skies of May,

Earth her choicest gifts is yielding,

But one is past away.

The spring that clothes with tend’rest green

Each grove and sunny

plain,

Shines not for my forsaken heart,

Brings not my joys

again.

Warble not so, thou nightingale,

Upon thy blooming spray,

Thy

sweetness now will burst my heart,

I cannot bear thy lay.

For flowers and birds are come again,

And breezes mild of May,

But treasured hopes and golden hours

Are lost to me for aye!”

The two Norwegians sat plunged in melancholy thought; but especially Sintram’s eyes began to brighten with a milder expression, his cheeks glowed, every feature softened, till those who looked at him could have fancied they saw a glorified spirit. The good Rolf, who had stood listening to the song, rejoiced thereat from his heart, and devoutly raised his hands in pious gratitude to heaven. But Gabrielle’s astonishment suffered her not to take her eyes from Sintram. At last she said to him, “I should much like to know what has so struck you in that little song. It is merely a simple lay of the spring, full of the images which that sweet season never fails to call up in the minds of my countrymen.”

“But is your home really so lovely, so wondrously rich in song?” cried the enraptured Sintram. “Then I am no longer surprised at your heavenly beauty, at the power which you exercise over my hard, wayward heart! For a paradise of song must surely send such angelic messengers through the ruder parts of the world.” And so saying, he fell on his knees before the lady in an attitude of deep humility. Folko looked on all the while with an approving smile, whilst Gabrielle, in much embarrassment, seemed hardly to know how to treat the half-wild, half-tamed young stranger. After some hesitation, however, she held out her fair hand to him, and said as she gently raised him: “Surely one who listens with such delight to music must himself know how to awaken its strains. Take my lute, and let us hear a graceful inspired song.”

But Sintram drew back, and would not take the instrument; and he said, “Heaven forbid that my rough untutored hand should touch those delicate strings! For even were I to begin with some soft strains, yet before long the wild spirit which dwells in me would break out, and there would be an end of the form and sound of the beautiful instrument. No, no; suffer me rather to fetch my own huge harp, strung with bears’ sinews set in brass, for in truth I do feel myself inspired to play and sing.”

Gabrielle murmured a half-frightened assent; and Sintram having quickly brought his harp, began to strike it loudly, and to sing these words with a voice no less powerful:

“Sir knight, sir knight, oh! whither away

With thy snow-white sail on

the foaming spray?"

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of flowers!

“Too long have I trod upon ice and snow;

I seek the bowers where

roses blow."

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of flowers!

He steer’d on his course by night and day

Till he cast his anchor in

Naples Bay.

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of flowers!

There wander’d a lady upon the strand,

Her fair hair bound with a

golden band.

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of flowers!

“Hail to thee! hail to thee! lady bright,

Mine own shalt thou be ere

morning light."

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of flowers!

“Not so, sir knight,” the lady replied,

“For you speak to the

margrave’s chosen bride."

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of

flowers!

“Your lover may come with his shield and spear,

And the victor shall

win thee, lady dear!”

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of flowers!

“Nay, seek for another bride, I pray;

Most fair are the maidens of

Naples Bay."

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of flowers!

“No, lady; for thee my heart doth burn,

And the world cannot now my

purpose turn."

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of flowers!

Then came the young margrave, bold and brave;

But low was he laid in

a grassy grave.

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of flowers!

And then the fierce Northman joyously cried,

“Now shall I possess

lands, castle, and bride!”

Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of

flowers!

Sintram’s song was ended, but his eyes glared wildly, and the vibrations of the harp-strings still resounded in a marvellous manner. Biorn’s attitude was again erect; he stroked his long beard and rattled his sword, as if in great delight at what he had just heard. Much shuddered Gabrielle before the wild song and these strange forms, but only till she cast a glance on the Lord of Montfaucon, sat there smiling in all his hero strength, unmoved, the rough uproar passed by him like an autumnal storm.

Some weeks after this, in the twilight of evening, Sintram, very disturbed, came down to the castle-garden. Although the presence of Gabrielle never failed to soothe and calm him, yet if she left the apartment for even a few instants, the fearful wildness of his spirit seemed to return with renewed strength. So even now, after having long and kindly read legends of the olden times to his father Biorn, she had retired to her chamber. The tones of her lute could be distinctly heard in the garden below; but the sounds only drove the bewildered youth more impetuously through the shades of the ancient elms. Stooping suddenly to avoid some overhanging branches, he unexpectedly came upon something against which he had almost struck, and which, at first sight, he took for a small bear standing on its hind legs, with a long and strangely crooked horn on its head. He drew back in surprise and fear. It addressed him in a grating man’s voice: “Well, my brave young knight, whence come you? whither go you? wherefore so terrified?” And then first he saw that he had before him a little old man so wrapped up in a rough garment of fur, that scarcely one of his features was visible, and wearing in his cap a strange-looking long feather.

“But whence come YOU and whither go YOU?” returned the angry Sintram. “For of you such questions should be asked. What have you to do in our domains, you hideous little being?”

“Well, well,” sneered the other one, “I am thinking that I am quite big enough as I am—one cannot always be a giant. And as to the rest, why should you find fault that I go here hunting for snails? Surely snails do not belong to the game which your high mightinesses consider that you alone have a right to follow! Now, on the other hand, I know how to prepare from them an excellent high-flavoured drink; and I have taken enough for to-day: marvellous fat little beasts, with wise faces like a man’s, and long twisted horns on their heads. Would you like to see them? Look here!”

And then he began to unfasten and fumble about his fur garment; but Sintram, filled with disgust and horror, said, “Psha! I detest such animals! Be quiet, and tell me at once who and what you yourself are.”

“Are you so bent upon knowing my name?” replied the little man. “Let it content you that I am master of all secret knowledge, and well versed in the most intricate depths of ancient history. Ah! my young sir, if you would only hear them! But you are afraid of me.”

“Afraid of you!” cried Sintram, with a wild laugh.

“Many a better man than you has been so before now,” muttered the little Master; “but they did not like being told of it any more than you do.”

“To prove that you are mistaken,” said Sintram, “I will remain here with you till the moon stands high in the heavens. But you must tell me one of your stories the while.”

The little man, much pleased, nodded his head; and as they paced together up and down a retired elm-walk, he began discoursing as follows:—

“Many hundred years ago a young knight, called Paris of Troy, lived in that sunny land of the south where are found the sweetest songs, the brightest flowers, and the most beautiful ladies. You know a song that tells of that fair land, do you not, young sir? ‘Sing heigh, sing ho, for that land of flowers.’” Sintram bowed his head in assent, and sighed deeply. “Now,” resumed the little Master, “it happened that Paris led that kind of life which is not uncommon in those countries, and of which their poets often sing—he would pass whole months together in the garb of a peasant, piping in the woods and mountains and pasturing his flocks. Here one day three beautiful sorceresses appeared to him, disputing about a golden apple; and from him they sought to know which of them was the most beautiful, since to her the golden fruit was to be awarded. The first knew how to give thrones, and sceptres, and crowns; the second could give wisdom and knowledge; and the third could prepare philtres and love-charms which could not fail of securing the affections of the fairest of women. Each one in turn proffered her choicest gifts to the young shepherd, in order that, tempted by them, he might adjudge the apple to her. But as fair women charmed him more than anything else in the world, he said that the third was the most beautiful—her name was Venus. The two others departed in great displeasure; but Venus bid him put on his knightly armour and his helmet adorned with waving feathers, and then she led him to a famous city called Sparta, where ruled the noble Duke Menelaus. His young Duchess Helen was the loveliest woman on earth, and the sorceress offered her to Paris in return for the golden apple. He was most ready to have her and wished for nothing better; but he asked how he was to gain possession of her.”

“Paris must have been a sorry knight,” interrupted Sintram. “Such things are easily settled. The husband is challenged to a single combat, and he that is victorious carries off the wife.”

“But Duke Menelaus was the host of the young knight,” said the narrator.

“Listen to me, little Master,” cried Sintram; “he might have asked the sorceress for some other beautiful woman, and then have mounted his horse, or weighed anchor, and departed.”

“Yes, yes; it is very easy to say so,” replied the old man. “But if you only knew how bewitchingly lovely this Duchess Helen was, no room was left for change.” And then he began a glowing description of the charms of this wondrously beautiful woman, but likening the image to Gabrielle so closely, feature for feature, that Sintram, tottering, was forced to lean against a tree. The little Master stood opposite to him grinning, and asked, “Well now, could you have advised that poor knight Paris to fly from her?”

“Tell me at once what happened next,” stammered Sintram.

“The sorceress acted honourably towards Paris,” continued the old man. “She declared to him that if he would carry away the lovely duchess to his own city Troy, he might do so, and thus cause the ruin of his whole house and of his country; but that during ten years he would be able to defend himself in Troy, and rejoice in the sweet love of Helen.”

“And he accepted those terms, or he was a fool!” cried the youth.

“To be sure he accepted them,” whispered the little Master. “I would have done so in his place! And do you know, young sir, the look of things then was just as they are happening to-day. The newly-risen moon, partly veiled by clouds, was shining dimly through the thick branches of the trees in the silence of evening. Leaning against an old tree, as you now are doing, stood the young enamoured knight Paris, and at his side the enchantress Venus, but so disguised and transformed, that she did not look much more beautiful than I do. And by the silvery light of the moon, the form of the beautiful beloved one was seen sweeping by alone amidst the whispering boughs.” He was silent, and like as in the mirror of his deluding words, Gabrielle just then actually herself appeared, musing as she walked alone down the alley of elms.

“Man,—fearful Master,—by what name shall I call you? To what would you drive me?” muttered the trembling Sintram.

“Thou knowest thy father’s strong stone castle on the Moon-rocks?” replied the old man. “The castellan and the garrison are true and devoted to thee. It could stand a ten years’ siege; and the little gate which leads to the hills is open, as was that of the citadel of Sparta for Paris.”

And, in fact, the youth saw through a gate, left open he knew not how, the dim, distant mountains glittering in the moonlight. “And if he did not accept, he was a fool,” said the little Master, with a grin, echoing Sintram’s former words.

At that moment Gabrielle stood close by him. She was within reach of his grasp, had he made the least movement; and a moonbeam, suddenly breaking forth, transfigured, as it were, her heavenly beauty. The youth had already bent forward—

“My Lord and God, I pray,

Turn from his heart away

This world’s

turmoil;

And call him to Thy light,

Be it through sorrow’s

night,

Through pain or toil.”

These words were sung by old Rolf at that very time, as he lingered on the still margin of the castle fish-pond, where he prayed alone to Heaven, full of foreboding care. They reached Sintram’s ear; he stood as if spellbound and made the Sign of the Cross. Immediately the little master fled away, jumping uncouthly on one leg, through the gates and shutting them after him with a yell.

Gabrielle shuddered, terrified at the wild noise. Sintram approached her softly, and said, offering his arm to her: “Suffer me to lead you back to the castle. The night in these northern regions is often wild and fearful.”

They found the two knights drinking wine within. Folko was relating stories in his usual mild and cheerful manner, and Biorn was listening with a moody air, but yet as if, against his will, the dark cloud might pass away before that bright and gentle courtesy. Gabrielle saluted the baron with a smile, and signed to him to continue his discourse, as she took her place near the knight Biorn, full of watchful kindness. Sintram stood by the hearth, abstracted and melancholy; and the embers, as he stirred them, cast a strange glow over his pallid features.

“And of all the German trading-towns,” continued Montfaucon, “the largest and richest is Hamburgh. In Normandy we willingly see their merchants land on our coasts, and those excellent people never fail to prove themselves our friends when we seek their advice and assistance. When I first visited Hamburgh, every honour and respect was paid to me. I found its inhabitants engaged in a war with a neighbouring count, and immediately I used my sword for them, vigorously and successfully.”

“Your sword! your knightly sword!” interrupted Biorn; and the old wonted fire flashed from his eyes. “Against a knight, and for shopkeepers!”

“Sir knight,” replied Folko, calmly, “the barons of Montfaucon have ever used their swords as they chose, without the interference of another; and as I have received this good custom, so do I wish to hand it on. If you agree not to this, so speak it freely out. But I forbid every rude word against the men of Hamburgh, since I have declared them to be my friends.”

Biorn cast down his haughty eyes, and their fire faded away. In a low voice he said, “Proceed, noble baron. You are right, and I am wrong.”

Then Folko stretched out his hand to him across the table, and resumed his narration: “Amongst all my beloved Hamburghers the dearest to me are two men of marvellous experience—a father and son. What have they not seen and done in the remotest corners of the earth, and instituted in their native town! Praise be to God, my life cannot be called unfruitful; but, compared with the wise Gotthard Lenz and his stout-hearted son Rudlieb, I look upon myself as an esquire who has perhaps been some few times to tourneys, and, besides that, has never hunted out his own forests. They have converted, subdued, gladdened, dark men whom I know not how to name; and the wealth which they have brought back with them has all been devoted to the common weal, as if fit for no other purpose. On their return from their long and perilous sea-voyages, they hasten to an hospital which has been founded by them, and where they undertake the part of overseers, and of careful and patient nurses. Then they proceed to select the most fitting spots whereon to erect new towers and fortresses for the defence of their beloved country. Next they repair to the houses where strangers and travellers receive hospitality at their cost; and at last they return to their own abode, to entertain their guests, rich and noble like kings, and simple and unconstrained like shepherds. Many a tale of their wondrous adventures serves to enliven these sumptuous feasts. Amongst others, I remember to have heard my friends relate one at which my hair stood on end. Possibly I may gain some more complete information on the subject from you. It appears that several years ago, just about the time of the Christmas festival, Gotthard and Rudlieb were shipwrecked on the coast of Norway, during a violent winter tempest. They could never exactly ascertain the situation of the rocks on which their vessel stranded; but so much is certain, that very near the sea-shore stood a huge castle, to which the father and son betook themselves, seeking for that assistance and shelter which Christian people are ever willing to afford each other in case of need. They went alone, leaving their followers to watch the injured ship. The castle-gates were thrown open, and they thought all was well. But on a sudden the court-yard was filled with armed men, who with one accord aimed their sharp iron-pointed spears at the defenceless strangers, whose dignified remonstrances and mild entreaties were only heard in sullen silence or with scornful jeerings. After a while a knight came down the stairs, with fire- flashing eyes. They hardly knew whether to think they saw a spectre, or a wild heathen; he gave a signal, and the fatal spears closed around them. At that instant the soft tones of a woman’s voice fell on their ear, calling on the Saviour’s holy name for aid; at the sound, the spectres in the court-yard rushed madly one against the other, the gates burst open, and Gotthard and Rudlieb fled away, catching a glimpse as they went of an angelic woman who appeared at one of the windows of the castle. They made every exertion to get their ship again afloat, choosing to trust themselves to the sea rather than to that barbarous coast; and at last, after manifold dangers, they landed at Denmark. They say that some heathen must have owned the cruel castle; but I hold it to be some ruined fortress, deserted by men, in which hellish spectres were wont to hold their nightly meetings. What heathen could be found so demon- like as to offer death to shipwrecked strangers, instead of refreshment and shelter?”

Biorn gazed fixedly on the ground, as though he were turned into stone but Sintram came towards the table, and said, “Father, let us seek out this godless abode, and lay it level with the dust. I cannot tell how, but somehow I feel quite sure that the accursed deed of which we have just heard is alone the cause of my frightful dreams.”

Enraged at his son, Biorn rose up, and would perhaps again have uttered some dreadful words; but Heaven decreed otherwise, for just at that moment the pealing notes a trumpet were heard, which drowned the angry tones his voice, the great doors opened slowly, and a herald entered the hall. He bowed reverently, and then said, “I am sent by Jarl Eric the Aged. He returned two days ago from his expedition to the Grecian seas. His wish had been to take vengeance on the island which is called Chios, where fifty years ago his father was slain by the soldiers of the Emperor. But your kinsman, the sea- king Arinbiorn, who was lying there at anchor, tried to pacify him. To this Jarl Eric would not listen; so the sea-king said next that he would never suffer Chios to be laid waste, because it was an island where the lays of an old Greek bard, called Homer, were excellently sung, and where more-over a very choice wine was made. Words proving of no avail, a combat ensued; in which Arinbiorn had so much the advantage that Jarl Eric lost two of his ships, and only with difficulty escaped in one which had already sustained great damage. Eric the Aged has now resolved to take revenge on some of the sea- king’s race, since Arinbiorn himself is seldom on the spot. Will you, Biorn of the Fiery Eyes, at once pay as large a penalty in cattle, and money, and goods, as it may please the Jarl to demand? Or will you prepare to meet him with an armed force at Niflung’s Heath seven days hence?”

Biorn bowed his head quietly, and replied in a mild tone, “Seven days hence at Niflung’s Heath.” He then offered to the herald a golden goblet full of rich wine, and added, “Drink that, and then carry off with thee the cup which thou hast emptied.”

“The Baron of Montfaucon likewise sends greeting to thy chieftain, Jarl Eric,” interposed Folko; “and engages to be also at Niflung’s Heath, as the hereditary friend of the sea-king, and also as the kinsman and guest of Biorn of the Fiery Eyes.”

The herald was seen to tremble at the name of Montfaucon; he bowed very low, cast an anxious, reverential look at the baron, and left the hall.

Gabrielle looked on her knight, smiling lovingly and securely, for she well knew his victorious prowess; and she only asked, “Where shall I remain, whilst you go forth to battle, Folko?”

“I had hoped,” answered Biorn, “that you would be well contented to stay in this castle, lovely lady; I leave my son to guard you and attend on you.”

Gabrielle hesitated an instant; and Sintram, who had resumed his position near the fire, muttered to himself as he fixed his eyes on the bright flames which were flashing up, “Yes, yes, so it will probably happen. I can fancy that Duke Menelaus had just left Sparta on some warlike expedition, when the young knight Paris met the lovely Helen that evening in the garden.”

But Gabrielle, shuddering although she knew not why, said quickly, “Without you, Folko? And must I forego the joy of seeing you fight? or the honour of tending you, should you chance to receive a wound?”

Folko bowed, gracefully thanking his lady, and replied, “Come with your knight, since such is your pleasure, and be to him a bright guiding star. It is a good old northern custom that ladies should be present at knightly combats, and no true warrior of the north will fail to respect the place whence beams the light of their eyes. Unless, indeed,” continued he with an inquiring look at Biorn, “unless Jarl Eric is not worthy of his forefather?”

“A man of honour,” said Biorn confidently.

“Then array yourself, my fairest love,” said the delighted Folko; “array yourself and come forth with us to the battle-field to behold and judge our deeds.”

“Come forth with us to the battle,” echoed Sintram in a sudden transport of joy.

And they all dispersed in calm cheerfulness; Sintram betaking himself again to the wood, while the others retired to rest.

It was a wild dreary tract of country that, which bore the name of Niflung’s Heath. According to tradition, the young Niflung, son of Hogni, the last of his race, had there ended darkly a sad and unsuccessful life. Many ancient grave-stones were still standing round about; and in the few oak-trees scattered here and there over the plain, huge eagles had built their nests. The beating of their heavy wings as they fought together, and their wild screams, were heard far off in more thickly-peopled regions; and at the sound children would tremble in their cradles, and old men quake with fear as they slumbered over the blazing hearth.

As the seventh night, the last before the day of combat, was just beginning, two large armies were seen descending from the hills in opposite directions; that which came from the west was commanded by Eric the Aged, that from the east by Biorn of the Fiery Eyes. They appeared thus early in compliance with the custom which required that adversaries should always present themselves at the appointed field of battle before the time named, in order to prove that they rather sought than dreaded the fight. Folko forthwith pitched on the most convenient spot the tent of blue samite fringed with gold, which he carried with him to shelter his gentle lady; whilst Sintram, in the character of herald, rode over to Jarl Eric to announce to him that the beauteous Gabrielle of Montfaucon was present in the army of the knight Biorn, and would the next morning be present as a judge of the combat.

Jarl Eric bowed low on receiving this pleasing message; and ordered his bards to strike up a lay, the words of which ran as follows:—

“Warriors bold of Eric’s band,

Gird your glittering armour on,

Stand beneath to-morrow’s sun,

In your might.

Fairest dame that ever gladden’d

Our wild shores with beauty’s

vision,

May thy bright eyes o’er our combat,

Judge the right!

Tidings of yon noble stranger

Long ago have reach’d our ears,

Wafted upon southern breezes,

O’er the wave.

Now midst yonder hostile ranks,

In his warlike pride he meets us,

Folko comes! Fight, men of Eric,

True and brave!”

These wondrous tones floated over the plain, and reached the tent of Gabrielle. It was no new thing to her to hear her knight’s fame celebrated on all sides; but now that she listened to his praises bursting forth in the stillness of night from the mouth of his enemies, she could scarce refrain from kneeling at the feet of the mighty chieftain. But he with courteous tenderness held her up, and pressing his lips fervently on her soft hand, he said, “My deeds, O lovely lady, belong to thee, and not to me!”