Title: Art in Needlework: A Book about Embroidery

Author: Lewis F. Day

active 1900 Mary Buckle

Release date: March 7, 2009 [eBook #28269]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Constanze Hofmann and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note:

A number of typographical errors have been corrected. They are shown in the text with mouse-hover popups.

All greyscale images have been provided as thumbnails. A larger version of those images is available by clicking on the link below the image.

The numerous full page images have been moved to the nearest paragraph break, the page numbers for these pages have been omitted. Where the index links to such a page, the link goes directly to the image in question.

TEXT-BOOKS OF ORNAMENTAL DESIGN

A BOOK ABOUT EMBROIDERY

BY

LEWIS F. DAY

AUTHOR OF 'WINDOWS,' 'ALPHABETS,'

'NATURE IN ORNAMENT' AND OTHER

TEXT-BOOKS OF ORNAMENTAL DESIGN

& MARY BUCKLE

LONDON:

B. T. BATSFORD 94 HIGH HOLBORN

1900

BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO. LD., PRINTERS,

LONDON AND TONBRIDGE.

Embroidery may be looked at from more points of view than it would be possible in a book like this to take up seriously. Merely to hover round the subject and glance casually at it would serve no useful purpose. It may be as well, therefore, to define our standpoint: we look at the art from its practical side, not, of course, neglecting the artistic, for the practical use of embroidery is to be beautiful.

The custom has been, since woman learnt to kill time with the needle, to think of embroidery too much as an idle accomplishment. It is more than that. At the very least it is a handicraft: at the best it is an art. This contention may be to take it rather seriously; but if one esteemed it less it would hardly be worth writing about, and the book, when written, would not be worth the attention of students of embroidery, needleworkers, and designers of needlework to whom it is addressed. It sets forth to show what decorative stitching is, how it is done, and what it can do. It is illustrated by samplers of stitches;[vi] by diagrams, to explain the way stitches are done; and by examples of old and modern work, to show the artistic application of the stitches.

A feature in the book is the series of samplers designed to show not only what are the available stitches, but the groups into which they naturally gather themselves, as well as the use to which they may be put: and the back of the sampler is given too: the reader has only to turn the page to see the other side of the stitching—which to a needlewoman is often the more helpful. Lest that should not be enough, the stitches are described in the text, and a marginal note shows at a glance where the description is given. This should be read needle and thread in hand—or skipped. Samplers and other examples of needlework are uniformly on a scale large enough to show the stitch quite plainly. The examples of old work illustrate always, in the first place, some point of workmanship; still they are chosen with some view to their artistic interest.

In other respects Art is not overlooked; but it is Art in harness. Design is discussed with reference to stitch and stuff, and stitch and stuff with reference to their use in ornament. It has been endeavoured also to show the effect needlework has had upon pattern, and the ways in which design is affected by the circumstance that it is to be embroidered.

The joint authorship of the work needs, perhaps,[vii] a word of explanation. This is not just a man's book on a woman's subject. The scheme of it is mine, and I have written it, but with the co-operation throughout of Miss Mary Buckle. Our classification of the stitches is the result of many a conference between us. The description of the way the stitches are worked, and so forth, is my rendering of her description, supplemented by practical demonstration with the needle. She has primed me with technical information, and been always at hand to keep me from technical error. With reference to design and art I speak for myself.

My thanks are due to the authorities at South Kensington for allowing us to handle the treasures of the national collection, and to photograph them for illustration; to Mrs. Walter Crane, Miss Mabel Keighley, and Miss C. P. Shrewsbury, for permission to reproduce their handiwork; to Miss Argles, Mrs. Buxton Morrish, Colonel Green, R.E., and Messrs. Morris and Co., for the loan of work belonging to them; and to Miss Chart for working the cross-stitch sampler.

I must also acknowledge the part my daughter has had in the production of this book: without her constant help it could never have been written.

LEWIS F. DAY.

January 1st, 1900.

A. COUNTER-CHANGE PATTERN, INLAY OR APPLIQUÉ.—Yellow satin and crimson velvet. The outline, which is in gold, falls chiefly upon the yellow, so as not to disturb the exact balance of light and dark, which it is essential to preserve in counter-change. Part of a stole. Spanish. 16th century (V. & A. M.)

B. APPLIQUÉ, of deep crimson velvet upon white satin, outlined with paler red cord. The outlines, meeting together, form a stem of double cord. Italian. 17th century. (V. & A. M.)[xviii]

Page 30. Diagram belongs to G (Stem-Stitch) described on page 32, not C (Thick Crewel-Stitch).

Page 125, 2nd line. For "lower" read "upper."

Embroidery begins with the needle, and the needle (thorn, fish-bone, or whatever it may have been) came into use so soon as ever savages had the wit to sew skins and things together to keep themselves warm—modesty, we may take it, was an afterthought—and if the stitches made any sort of pattern, as coarse stitching naturally would, that was embroidery.

The term is often vaguely used to denote all kinds of ornamental needlework, and some with which the needle has nothing to do. That is misleading; though it is true that embroidery does touch, on the one side, tapestry, which may be described as a kind of embroidery with the shuttle, and, on the other, lace, which is needlework pure and simple, construction "in the air" as the Italian name has it.

The term is used in common parlance to express any kind of superficial or superfluous ornamentation. A poet is said to embroider the truth.[2] But such metaphorical use of the word hints at the real nature of the work—embellishment, enrichment, added. If added, there must first of all be something it is added to—the material, that is to say, on which the needlework is done. In weaving (even tapestry weaving) the pattern is got by the inter-threading of warp and weft. In lace, too, it is got out of the threads which make the stuff. In embroidery it is got by threads worked on a fabric first of all woven on the loom, or, it might be, netted.

There is inevitably a certain amount of overlapping of the crafts. For instance, take a form of embroidery common in all countries, Eastern, Hungarian, or nearer home, in which certain of the weft threads of the linen are drawn out, and the needlework is executed upon the warp threads thus revealed. This is, strictly speaking, a sort of tapestry with the needle, just as, it was explained, tapestry itself may be described as a sort of embroidery with the shuttle. That will be clearly seen by reference to Illustration 1, which shows a fragment of ancient tapestry found in a Coptic tomb in Upper Egypt. In the lower portion of it the pattern appears light on dark. As a matter of fact, it was wrought in white and red upon a linen warp; but, as it happened, only the white threads were of linen, like the warp, the red were woollen, and in the course of fifteen hundred years or so much of this red wool has perished, leaving the[4] white pattern intact on the warp, the threads of which are laid bare in the upper part of the illustration.

It is on just such upright lines of warp that all tapestry, properly so called, is worked—whether with the shuttle or with the needle makes no matter—and there is good reason, therefore, for the name of "tapestry stitch" to describe needlework upon the warp threads only of a material (usually linen) from which some of the weft threads have been withdrawn.

The only difference between true tapestry and drawn work, an example of which is here given, is, that the one is done on a warp that has not before been woven upon, and the other on a warp from which the weft threads have been drawn. The distinction, therefore, between tapestry and embroidery is, that, worked on a warp, as in Illustration 1, it is tapestry; worked on a mesh, as in Illustration 3, it is embroidery.

With regard, again, to lace. That is itself a web, independent of any groundwork or foundation[6] to support it. But it is possible to work it over a silken or other surface; and there is a kind of embroidery which only floats on the surface of the material without penetrating it. A fragment of last century silk given in Illustration 35 shows plainly what is meant.

Embroidery is enrichment by means of the needle. To embroider is to work on something: a groundwork is presupposed. And we usually understand by embroidery, needlework in thread (it may be wool, cotton, linen, silk, gold, no matter what) upon a textile material, no matter what. In short, it is the decoration of a material woven in thread by means still of thread. It is thus the consistent way of ornamenting stuff—most consistent of all when one kind of thread is employed throughout, as in the case of linen upon linen, silk upon silk. The enrichment may, however, rightly be, and oftenest is, perhaps, in a material nobler than the stuff enriched, in silk upon linen, in wool upon cotton, in gold upon velvet. The advisability of working upon a precious stuff in thread less precious is open to question. It does not seem to have been satisfactorily done; but if it were only the background that was worked, and the pattern were so schemed as almost to cover it, so that, in fact, very little of the more beautiful texture was sacrificed, and you had still a sumptuous pattern on a less attractive background—why not? But then it would be because you wanted that less[7] precious texture there. The excuse of economy would scarcely hold good.

In the case of a material in itself unsightly, the one course is to cover it entirely with stitching, as did the Persian and other untireable people of the East. But not they only. The famous Syon cope is so covered. Much of the work so done, all-over work that is to say, competes in effect with tapestry or other weaving; and its purpose was similar: it is a sort of amateur way of working your own stuff. But in character it is no more nearly related to the work of the loom than other needlework—it is still work on stuff. For all-over embroidery one chooses, naturally, a coarse canvas ground to work on; but it more often happens that one chooses canvas because one means to cover it, than that one works all over a ground because it is unpresentable.

Embroidery is merely an affair of stitching; and the first thing needful alike to the worker in it and the designer for it is, a thorough acquaintance with the stitches; not, of course, with every modification of a modification of a stitch which individual ingenuity may have devised—it would need the space of an encyclopædia to chronicle them all—but with the broadly marked varieties of stitch which have been employed to best purpose in ornament.

They are derived, naturally, from the stitches first used for quite practical and prosaic purposes—buttonhole[8] stitch, for example, to keep the edges of the stuff from fraying; herring-bone, to strengthen and disguise a seam; darning, to make good a worn surface; and so on.

The difficulty of discussing them is greatly increased by the haphazard way in which they are commonly named. A stitch is called Greek, Spanish, Mexican, or what not, according to the country whence came the work in which some one first found it. Each names it after his or her individual discovery, or calls it, perhaps, vaguely Oriental; and so we have any number of names for the same stitch, names which to different people stand often for quite different stitches.

When this confusion is complicated by the invention of a new name for every conceivable combination of thread-strokes, or for each slightest variation upon an old stitch, and even for a stitch worked from left to right instead of from right to left, or for a stitch worked rather longer than usual, the task of reducing them to order seems almost hopeless.

Nor do the quasi-learned descriptions of old stitches help us much. One reads about opus this and opus that, until one begins to wonder where, amidst all this parade of science, art comes in. But you have not far to go in the study of the authorities to discover that, though they may concur in using certain high-sounding Latin terms, they are not of the same mind as to their meaning.[9] In one thing they all agree, foreign writers as well as English, and that is, as to the difficulty of identifying the stitch referred to by ancient writers, themselves probably not acquainted with the technique of stitching, and as likely as not to call it by a wrong name. It is easier, for example, to talk of Opus Anglicanum than to say precisely what it was, further than that it described work done in England; and for that we have the simple word—English. There is nothing to show that mediæval English work contained stitches not used elsewhere. The stitches probably all come from the East.

Nomenclature, then, is a snare. Why not drop titles, and call stitches by the plainest and least mistakable names? It will be seen, if we reduce them to their native simplicity, that they fall into fairly-marked groups, or families, which can be discussed each under its own head.

Stitches may be grouped in all manner of arbitrary ways—according to their provenance, according to their effect, according to their use, and so on. The most natural way of grouping them is according to their structure; not with regard to whence they came, or what they do, but according to what they are, the way they are worked. This, at all events, is no arbitrary classification, and this is the plan it is proposed here to adopt.[10]

The use of such classification hardly needs pointing out.

A survey of the stitches is the necessary preliminary, either to the design or to the execution of needlework. How else suit the design to the stitch, the stitch to the design? In order to do the one the artist must be quite at home among the stitches; in order to do the other the embroidress must have sympathy enough with a design to choose the stitch or stitches which will best render it. An artist who thinks the working out of his sketch none of his business is no practical designer; the worker who thinks design a thing apart from her is only a worker.

This is not the moment to urge upon the needlewoman the study of design, but to urge upon the designer the study of stitches. Nothing is more impractical than to make a design without realising the labour involved in its execution. Any one not in sympathy with stitching may possibly design a beautiful piece of needlework, but no one will get all that is to be got out of the needle without knowing all about it. One must understand the ways in which work can be done in order to determine the way it shall in any particular case be done.

Certain stitches answer certain purposes, and strictly only those. The designer must know which stitch answers which purpose, or he will in the first place waste the labour of the embroidress,[11] and in the second miss his effect, which is to waste his own pains too. The effective worker (designer or embroiderer) is the one who works with judgment—and you cannot judge unless you know. When it is remembered that the character of needlework, and by rights also the character of its design, depends upon the stitch, there will be no occasion to insist further upon the necessity of a comprehensive survey of the stitches.

A stitch may be defined as the thread left on the surface of the cloth or what not, after each ply of the needle.

And the simple straightforward stitches of this kind are not so many as one might suppose. They may be reduced indeed to a comparatively few types, as will be seen in the following chapters.

The simplest, as it is most likely the earliest used, stitch-group is what might best be called Canvas stitch—of which cross-stitch is perhaps the most familiar type, the class of stitches which come of following, as it is only natural to do, the mesh of a coarse canvas, net, or open web upon which the work is done.

A stitch bears always, or should bear, some relation to the material on which it is worked; but canvas or very coarse linen almost compels a stitch based upon the cross lines of its woof, and indeed suggests designs of equally rigid construction. That is so in embroidery no matter where. In ancient Byzantine or Coptic work, in modern Cretan work, and in peasant embroidery all the world over, pattern work on coarse linen has run persistently into angular lines—in which, because of that very angularity, the plain outcome of a way of working, we find artistic character. Artistic design is always expressive of its mode of workmanship.

Work of this kind is not too lightly to be dismissed. There is art in the rendering of form by means of angular outlines, art in the choice of[13] forms which can be expressed by such lines. It is not uncharitable to surmise that one reason why such work (once so universal and now quite out of fashion) is not popular with needlewomen may be, the demand it makes upon the designer's draughtmanship: it is much easier, for example, to draw a stag than to render the creature satisfactorily within jagged lines determined by a linen mesh.

The piquancy about natural or other forms thus reduced to angularity argues, of course, no affectation of quaintness on the part of the worker, but was the unavoidable outcome of her way of work. There is a pronounced and early limit to art of this rather naïve kind, but that there is art in some of the very simplest and most modest peasant work built up on those lines no artist will deny. The art in it is usually in proportion to its modesty. Nothing is more futile than to put it to anything[14] like pictorial purpose. The wonderfully wrought pictures in tent-stitch, for example, bequeathed to us by the 17th century, are painful object lessons in what not to do.

The origin of the term cross-stitch is not far to seek: the stitches worked upon the square mesh do cross. But, falling naturally into the lines of the mesh which governs them, they present not so much the appearance of crosses as of squares, reminding one of the tesseræ employed in mosaic.

To explain the process of working cross-stitch would be teaching one's grandmother indeed. It is simply, as its name implies, crossing one stitch by another, following always the lines of the canvas. But the important thing about it is that the stitches must cross always in the same way; and, more than that, they must be worked in the same direction, or the mere fact that the stitches at the back of the work do not run in the same way will disturb the evenness of the surface. What looks like a seam on the sampler opposite is the result of filling up a gap in the ground with stitches necessarily worked in vertical, whereas the ground generally is in horizontal, lines. On the face of the work the stitches cross all in the same way.

The common use of cross-stitch and the somewhat geometric kind of pattern to which it lends itself are shown in the sampler, Illustration 5.

The broad and simple leafage, worked solid (A) or left in the plain canvas upon a groundwork of[16] solid stitching (B), and the fretted diaper on vertical and horizontal lines (C), show the most straightforward ways of using it.

The criss-cross of alternating cross-stitches and open canvas framed by the key pattern (C) shows a means of getting something like a tint halfway between solid work and plain ground. The mere work line—or "stroke-stitch," not crossed (D), is a perfectly fair way of getting a delicate effect; but the design has a way of working out rather less happily than it promised.

The addition of such stroke-stitches to solid cross-stitch (E) is not at best a very happy device. It strikes one always as a confession of dissatisfaction on the part of the worker with the simple means of her choice. As a device for, as it were, correcting the stepped outline it is at its worst. Timid workers are always afraid of the stepped outline which a coarse mesh gives. In that they are wrong. One should employ canvas stitch only where there is no objection to a line which keeps step with the canvas; then there is a positive charm (for frank people at least) in the frank confession of the way the work is done.

There are many degrees in the frankness with which this convention has been accepted, according perhaps to the coarseness of the canvas ground, perhaps to the personality of the worker. The animal forms at the top of Illustration 6 are uncompromisingly square; the floral devices on[18] the same page, though they fall, as it were inevitably, into square lines, are less rigidly formal. The inevitableness of the square line is apparent in the sprig below (7). It was evidently meant to be freely drawn, but the influence of the mesh betrays itself; and the design, if it loses something in grace, gains also thereby in character.

There is literally no end to the variety of stitches, as they are called, belonging to this group, and their names are a babel of confusion. Florentine, Parisian, Hungarian, Spanish, Moorish, Cashmere, Milanese, Gobelin, are only a few of them; but they stand, as a rule, rather for stitch arrangements than for stitches. A small selection of them is given in Illustration 8.

What is known as tent-stitch (A in the sampler opposite) is a sort of half cross-stitch; its peculiarity is that it covers only one thread of the[20] canvas at a stroke, and is therefore on a more minute scale than stitches which are two or three threads wide, as cross-stitch may, and cushion-stitch must, be. It derives its name from the old word tenture, or tenter (tendere, to stretch), the frame on which the embroidress distended her canvas. The word has gone out of use, but we still speak of tenter-hooks. The stitch is serviceable enough in its way, but is discredited by the monstrous abuse of it referred to already. A picture in tent-stitch is even more foolish than a picture in mosaic. It cannot come anywhere near to pictorial effect; the tesseræ will pronounce themselves, and spoil it.

This kind of half cross-stitch worked on the larger scale of ordinary cross-stitch would look[21] meagre. It is filled out, therefore (B), by horizontal lines of the thread laid across the canvas, and over these the stitch is worked.

Cushion-stitch consists of diagonal lines of upright stitches, measuring in the sampler (C) six threads of the canvas, so that after each stitch the needle may be brought out just three threads lower than where it was put in. By working in zigzag instead of diagonal lines, a familiar pattern is produced, more often described as "Florentine;" but the stitch is in any case the same.

The stitch at D (sometimes called Moorish stitch) is begun by working a row of short vertical stitches, slightly apart, and completed by diagonal stitches joining them.

Unless the silk employed is full and soft, this may not completely cover the canvas, in which case the diagonal stitches must further be crossed as shown on Illustration 89.

If the linen is loosely woven and the thread is tightly drawn in the working, the mesh is pulled apart, giving the effect of an open lattice of the kind shown at B, on Illustration 10, in which the threads of the linen are not drawn out but drawn together.

The way of working the stitch at E is described on page 51, under the name of "fish-bone." Worked on canvas it has somewhat the effect of plaiting, and goes by the name of "plait-stitch."[22] It is worked in horizontal rows alternately from left to right and from right to left.

The stitch at F is a sort of couching (see page 124). Diagonal lines of thread are first laid from edge to edge of the ground space, and these are sewn down by short overcasting stitches in the cross direction.

Admirable canvas stitch work has been done upon linen in silk of one colour—red, green, or blue—and it was a common practice to work the background leaving the pattern in the bare stuff. It prevailed in countries lying far apart, though probably not without inter-communication. In fact, the influence of Oriental work upon European has been so great that even experts hesitate sometimes to say whether a particular piece of work is Turkish or Italian. In Italian work, at least, it was usual to get over the angularity of silhouette inherent in canvas stitches by working an outline separately. When that is thin, the effect is proportionately feeble. The broader outline (shown at A, Illustration 10) justifies itself, and in the case of a stitch which falls into horizontal lines, it appears to be necessary. This is plait stitch, known also by the name of Spanish stitch—not that it is in any way peculiar to Spain. It is allied to herring-bone-stitch, to which a special chapter is devoted.

Darning is also employed as a canvas stitch. There is beautiful 16th century Italian work (in[24] coloured silks on dark net of the very open square mesh of the period), which is most effective, and in which there is no pretence of disguising the stepped outline; and in the very early days of Christian art in Egypt and Byzantium, linen was darned in little square tufts of wool upstanding on its surface, which look so much like the tesseræ of mosaic that it seems as if they must have been worked in deliberate imitation of it.

Again, in the 15th century satin-stitch was worked on fine linen with strict regard to the lines of its web; and the Persians, ancient and modern, embroider white silk upon linen, also in satin-stitch, preserving piously the rectangular and diagonal lines given by the material. They have their reward in producing most characteristic needlework. The diapered ground in Illustration 9 (page 20) is satin-stitch upon coarse linen.

The filling-in patterns used to such delicate and dainty purpose in the marvellous work on fine cambric (Illustration 73) which competes in effect with lace, though it is strictly embroidery, all follow in their design the lines of the fabric, and are worked thread by thread according to its woof: they afford again instances of perfect adaptation of stitch to material and of design to stitch.

Satin and other stitches were worked by the old Italians (Illustration 3) on square-meshed canvas, frankly on the square lines given by it, for the filling in of ornamental details, though the[25] outline might be much less formal. That is to say, the surface of freely-drawn leaves, &c., instead of being worked solid, was diapered over with more or less open pattern work constructed on the lines of the weaving.

A cunning use of the square mesh of canvas has sometimes been made to guide the worker upon other fabrics, such as velvet. This was first faced with net: the design was then worked, over that, on to and into the velvet, and the threads of the canvas were then drawn out. That is a device which may serve on occasion. The design may even be traced upon the net.

For work in the hand, Crewel-Stitch is perhaps, on the whole, the easiest and most useful of stitches; whence it comes that people sometimes vaguely call all embroidery crewel work; though, as a matter of fact, the stitch properly so called was never very commonly employed, even when the work was done in "crewel," the double thread of twisted wool from which it takes its name.

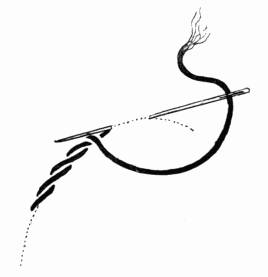

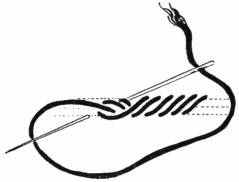

the working of A on crewel-stitch sampler.

Crewel-Stitch proper is shown at A on the sampler opposite, where it is used for line work. It is worked as follows:—Having made a start in the usual way, keep your thread downwards under your left thumb and below your needle—that is,[29] to the right; then take up with the needle, say ⅛th of an inch of the stuff, and bring it out through the hole made in starting the stitch, taking care not to pierce the thread. This gives the first half stitch. If you proceed in the same way your next stitch will be full length. The test of good workmanship is that at the back it should look like back-stitch (Illustration 12), described on page 30.

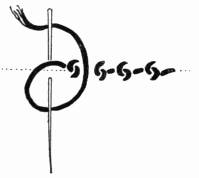

the working of B on crewel-stitch sampler.

Outline-Stitch (B on sampler) differs from crewel-stitch only in that the thread is always kept upwards above the needle, that is to the left. In so doing the thread is apt to untwist itself, and wants constantly re-twisting. The stitch is useful for single lines and for outlining solid work. The muddled effect of much crewel work is due to the confusion of this stitch with crewel-stitch proper.

Thick Crewel-Stitch (C on sampler) is only a little wider than ordinary crewel-stitch, but gives a heavier line, in higher relief. In effect it resembles rope-stitch, but it is more simply worked. You begin as in ordinary crewel-stitch, but after the first half-stitch you take up ⅛th of[30] an inch of the material in advance of the last stitch, and bring out your needle at the point where the first half-stitch began. You proceed, always putting your needle in ⅛th of an inch in front of, and bringing it out ⅛th of an inch behind, the last stitch, so as to have always ¼th of an inch of the stuff on your needle.

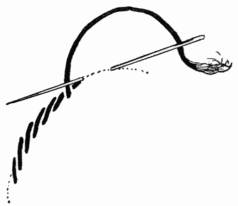

the working of G on crewel-stitch sampler.

Thick Outline-Stitch (D on sampler) is like thick crewel-stitch with the exception that, as in ordinary outline-stitch (B), you keep your thread always above the needle to the left.

In Back-Stitch (E), instead of first bringing the needle out at the point where the embroidery is to begin, you bring it out ⅛th of an inch in advance of it. Then, putting your needle back, you take up this ⅛th together with another ⅛th in advance. For the next stitch you put your needle into the hole made by the last stitch, and so on, taking care not to split the last thread in so doing.

To work the Spots (F) on sampler—having made a back-stitch, bring your needle out through the same hole as before, and make another back-stitch above it, so that you have, in what appears to be one stitch, two thicknesses of thread; then[32] bring your needle out some distance in advance of the last stitch, and proceed as before. The distance between the stitches is determined by the effect you desire to produce. The thread should not be drawn too tight.

You begin Stem-Stitch (G) with the usual half-stitch. Then, holding the thread downwards, instead of proceeding as in crewel-stitch (A) you slant your needle so as to bring it out a thread or two higher up than the half-stitch, but precisely above it. You next put the needle in ⅛th of an inch in advance of the last stitch, and, as before, bring it out again in a slanting direction a thread or two higher. At the back of the work (Illustration 12) the stitches lie in a slanting direction.

To work wider Stem-Stitch (H). After the first two stitches, bring your needle out precisely above and in a line with them, and put it in again ⅛th of an inch in advance of the last stitch, producing a longer stroke, which gives the measure of those following. The slanting stitches at the back (Illustration 12) are only two-thirds of the length of those on the face.

Crewel and Outline Stitches worked (J) side by side give somewhat the effect of a braid. The importance of not confusing them, already referred to, is here apparent.

Crewel-Stitch is worked SOLID in the heart-shape in the centre of the sampler. On the left side the rows of stitching follow the outline of[34] the heart; on the right they are more upright, merely conforming a little to the shape to be filled. This is the better method.

The way to work solid crewel-stitch will be best explained by an instance. Suppose a leaf to be worked. You begin by outlining it; if it is a wide leaf, you further work a centre line where the main rib would be, and then work row within row of stitches until the space is filled. If on arriving at the point of your leaf, instead of going round the edge, you work back by the side of the first row of stitching, there results a streakiness of texture, apparent in the stem on Illustration 13. What you get is, in effect, a combination of crewel and outline stitches, as at J, which in the other case only occurs in the centre of the shape where the files of stitches meet.

To represent shading in crewel-stitch, to which it is admirably suited (A, Illustration 41), it is well to work from the darkest shadows to the highest lights. And it is expedient to map out on the stuff the outline of the space to be covered by each shade of thread. There is no difficulty then in working round that shape, as above explained.

In solid crewel the stitches should quite cover the ground without pressing too closely one against the other.

It does not seem that Englishwomen of the 17th century were ever very faithful to the stitch we know by the name of crewel. Old examples of[36] work done entirely in crewel-stitch, as distinguished from what is called crewel work, are seldom if ever to be met with. The stitch occurs in most of the old English embroidery in wool; but it is astonishing, when one comes to examine the quilts and curtains of a couple of hundred years or so ago, how very little of the woolwork on them is in crewel-stitch. The detail on Illustration 13 was chosen because it contained more of it than any other equal portion of a handsome and typical English hanging; but it is only in the main stem, and in some of the outlines, that the stitch is used. And that appears to have been the prevailing practice—to use crewel-stitch for stems and outlines, and for little else but the very simplest forms. The filling in of the leafage, the diapering within the leaf shapes, and the smaller and more elaborate details generally were done in long-and-short-stitch, or whatever came handiest. In fact, the thing to be represented, fruit, berry, flower, or what not, seems to have suggested the stitch, which it must be confessed was sometimes only a sort of scramble to get an effect.

Of course the artist always chooses her stitch, and she is free to alter it as occasion may demand; but a good workwoman (and the embroidress is a needlewoman first and an artist afterwards, perhaps) adopts in every case a method, and departs from it only for very good reason. It looks as if our ancestors had set to work without system or guiding principle at all. No doubt they[37] got a bold and striking effect in their bed-hangings and the like; but there is in their work a lack of that conscious aim which goes to make art. Theirs is art of the rather artless sort which is just now so popular. Happily it was kept in the way it should go by a strict adherence to traditional pattern, which for the time being seems to have gone completely out of fashion.

Quite in the traditional manner is Illustration 14. One would fancy at first sight that the work was almost entirely in crewel-stitch. As a matter of fact, there is little which answers to the name, as an examination of the back of the work shows plainly enough. What the stitches are it is not easy to say. The mystery of many a stitch is to be unravelled only by literally picking out the threads, which one is not always at liberty to do, although, in the ardour of research, a keen embroidress will do it—not without remorse in the case of beautiful work, but relentlessly all the same.

The only piece of embroidery entirely in crewel-stitch which I could find for illustration (15) is worked, as it happens, in silk; nor was the worker aware that in so working she was doing anything out of the common. Another instance of crewel-stitch is given in the divided skirt, let us call it, of the personage in Illustration 72.

Beautiful back-stitching occurs in the Italian work on Illustration 89, and the stitch is used for sewing down the appliqué in Illustration 94.

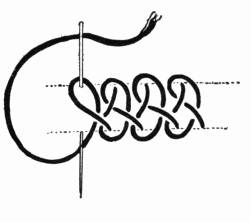

Chain and Tambour Stitch are in effect practically the same, and present the same rather granular surface. The difference between them is that chain-stitch is done in the hand with an ordinary needle, and tambour-stitch in a frame with a hook sharper at the turning point than an ordinary crochet hook. One takes it rather for granted that work which was presumably done in the hand (a large quilt, for example) is chain-stitch, and that what seems to have been done in a frame is tambour work, though it is possible, but not advisable of course, to work chain-stitch in a frame.

Chain-stitch is not to be confounded with split-stitch (see page 105), which somewhat resembles it.

To work chain-stitch (A on the sampler, Illustration 17) bring the needle out, hold the thread[41] down with the left thumb, put the needle in again at the hole through which you brought it out, take up ¼ of an inch of stuff, and draw the thread through: that gives you the first link of the chain. The back of the work (18) looks like back-stitch. In fact, in the quilted coverlet, Illustration 69 (as in much similar work of the period), the outline pattern, which you might take for back-stitching, proves to have been worked from the back in chain-stitch. The same thing occurs in the case of the Persian quilt in Illustration 70.

A playful variation upon chain-stitch (B on the sampler, Illustration 17) is effected by the use of two threads of different colour. Take in your needle a dark and a light thread, say the dark one to the left, and bring them out at the point at which your work begins. Hold the dark thread under your thumb, and, keeping the light one to the right, well out of the way, draw both threads through; this makes a dark link; the light thread disappears, and comes out again to the left of the dark one, ready to be held under the thumb while you make a light link. This "magic stitch," as it has been called, is no new invention. It is to be found in Persian, Indian, and Italian Renaissance work. An instance of it occurs in Illustration 64.

A variety of chain-stitch (C on the sampler, Illustration 17) used often in church work, more solid in appearance, the links not being so open,[42] is rather differently done. Begin a little in advance of the starting point of your work, hold the thread under your thumb, put the needle in again at the starting point slightly to the left, bring your needle out about ⅛th of an inch below where it first went in but precisely on the same line, and you have the first link of your chain.

To work what is known as cable-chain (D on the sampler, Illustration 17) keep your thread to the right, put in your needle, pointing downwards, a little below the starting point, and bring it out about ¼th of an inch below where you put it in; then put it through the little stitch just formed, from right to left, hold your thread towards the left under your thumb, put your needle through the stitch now in process of making from right to left, draw up the thread, and the first two links of your chain are made.

A zigzag chain, of a rather fancy description, goes by the name of Vandyke chain (E on the sampler, Illustration 17). To make it, bring your needle out at a point which is to be the left edge of your work, and make a slanting chain-stitch from left to right; then, putting your needle into that, make another slanting stitch, this time from right to left—and so to and fro to the end.

The braid-stitch shown at F on the sampler (Illustration 17) is worked as follows, horizontally from right to left. Bring your needle out at a point which is to be the lower edge of your work,[43] throw your thread round to the left, and, keeping it all the time loosely under your thumb, put your needle under the thread and twist it once round to the right. Then, at the upper edge of your work, put in the needle and slide the thread towards the right, bring the needle out exactly below where you put it in, carry your thread under the needle towards the left, draw the thread tight, and your first stitch is done.

the working of F on chain-stitch sampler.

A yet more fanciful variety of braid-stitch (G on the sampler, Illustration 17) is worked vertically, downwards. Having, as before, put your needle under the thread and twisted it once round, put it in at a point which is to be the left edge of your work, and, instead of bringing it out immediately below that point, slant it to the right, bringing it out on that edge of the work, and finish your stitch as in the case of F.

These braid-stitches look best worked in stout thread of close texture.

In covering a surface with chain-stitch (needlework or tambour) the usual plan is to follow the[44] contour of the design, working chain within chain until the leaf or whatever it may be is filled in. This stitch is rarely worked in lines across the forms, but it has been effectively used in that way, following always the lines of the warp and weft of the stuff. Even in that case the successive lines of stitching should be all in one direction—not running backwards and forwards—or it will result in a sort of pattern of braided lines. The reason for the more usual practice of following the outline of the design is obvious. The stitch lends itself to sweeping, even to perfectly spiral, lines—such as occur in Greek wave patterns: it was, in fact, made use of in that way by the Greeks some four or five centuries B.C.

the working of G on chain-stitch sampler.

We owe the tambour frame, they say, to China; but it has been largely used, and abused indeed, in England. Tambour work, when once you have the trick of it, is very quickly done—in about one-sixth of the time it would take to do it with the needle. It has the further advantage that it serves equally well for embroidery on a light or on a heavy stuff, and that it is most lasting. The misfortune is that the sewing[46] machine has learnt to do something at once so like it and so mechanically even, as to discredit genuine hand-work, whether tambour work or chain-stitch. For all that, neither is to be despised. If they have often a mechanical appearance that is not all the fault of the stitch: the worker is to blame. Indian embroiderers depart sometimes so far from mechanical precision as to shock the admirers of monotonously even work. Artistic use of chain stitch is made in many of our illustrations: for outlines in Illustrations 24 and 72; for surface covering in Mr. Crane's lion, Illustration 74; to represent landscape in Illustration 78, where everything except the faces of the little men is in chain-stitch; and again for figure work in Illustration 81. In Illustration 19 it occurs in association with a curious surface stitch; in Illustration 64 it is used to outline and otherwise supplement inlay. The old Italians did not disdain to use it. In fact, wherever artists have employed it, they show that there is nothing inherently inartistic about the stitch.

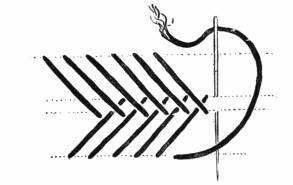

Herring-bone is the name by which it is customary to distinguish a variety of stitches somewhat resembling the spine of a fish such as the herring. It would be simpler to describe them as "fish-bone;" but that term has been appropriated to describe a particular variety of it. One would have thought it more convenient to use fish for the generic term, and a particular fish for the specific. However, it saves confusion to use names as far as possible in their accepted sense.

It will be seen from the sampler, Illustration 20, that this stitch may be worked open or tolerably close; but in the latter case it loses something of its distinctive character. Fine lines may be worked in it, but it appears most suited to the working of broadish bands and other more or less even-sided or, it may be, tapering forms, more feathery in effect than fish-bone-like, such as are shown at E on sampler.

Ordinary herring-bone is such a familiar stitch that the necessity of describing it is rather a matter of literary consistency than of practical importance.[48]

The two simpler forms of herring-bone (it is always worked from left to right, and begun with a half-stitch) marked A and C on the sampler are strikingly different in appearance, and are worked in different ways—as will be seen at once by reference to the back of the sampler (Illustration 21), where the stitches take in the one case a horizontal and in the other a vertical direction.

To work A, bring your needle out about the centre of the line to be worked; put it into the lower edge of the line about ⅛th of an inch further on; take up this much of the stuff, and, keeping the thread to the right, above the needle, draw it through. Then, with the thread below it, to the right, put your needle into the upper edge of the line ¼th of an inch further on, and, turning it backwards, take up again ⅛th of an inch of stuff, bringing it out immediately above where it went in on the lower edge.

What is called "Indian Herring-bone" (B) is merely stitch A worked in longer and more slanting stitches, so that there is room between them for a second row in another colour, the two colours being, of course, properly interlaced.

To work C, bring your needle out as for A, and, putting it in at the upper edge of the line to be worked and pointing it downwards, whilst your thread lies to the right, take up ever so small a piece of the stuff. Then, slightly in advance of the last stitch, the thread still to the right,[51] your needle now pointing upwards, take another similar stitch from the lower edge.

The variety at D is merely a combination of A and C, as may be seen by reference to the back of the sampler (opposite); though the short horizontal stitches there seen meet, instead of being wide apart as in the case of A.

the working of E on herring-bone sampler.

What is known as "fish-bone" is illustrated in the three feathery shapes on the sampler (E), two of which are worked rather open. It is characteristic of this stitch that it has a sort of spine up the centre where the threads cross. Suppose the stitch to be worked horizontally. Bring your needle out on the under edge of the spine about ¼th of an inch from the starting point of the work, and put it in on the upper edge of the work at the starting point, bringing it out immediately below that on the lower edge of the work. Put it in again on the upper edge of the spine, rather in[52] advance of where it came out on the lower edge of it before, and bring it out on the lower edge of this spine immediately below where it entered.

the working of F on herring-bone sampler.

In close herring-bone (F on the sampler, Illustration 20) you have always a long stitch from left to right, crossed by a shorter stitch which goes from right to left. Having made a half stitch, bring the needle out at the beginning of the line to be worked, at the lower edge, and put it in ⅛th of an inch from the beginning of the upper edge. Bring it out again at the beginning of this edge and put it in at the lower edge ¼th of an inch from the beginning, bringing it out on the same edge ⅛th of an inch from the beginning. Put the needle in again on the upper edge ⅛th of an inch in front of the last stitch on that edge, and bring it out again, without splitting the thread, on the same edge as the hole where the last stitch went in.

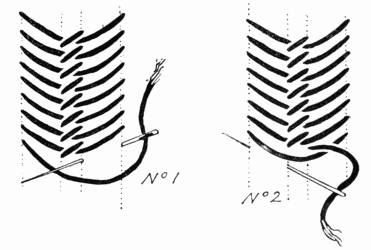

If you wish to cover a surface with herring-bone-stitch, you work it, of course, close, so that each[53] successive stitch touches its foregoer at the point where the needle enters the stuff (F on the sampler, Illustration 20). It will be seen that at the back (21) this looks like a double row of back-stitching. Worked straight across a wide leaf, as in the lower half of sampler, it is naturally very loose. A better method of working is shown in the side leaves, which are worked in two halves, beginning at the base of a leaf on one side and working down to it on the other. There is here just the suggestion of a mid-rib between the two rows.

the working of G on herring-bone sampler.

The stitch at G on sampler, having the effect of higher relief than ordinary close herring-bone (F), is sometimes misleadingly described as tapestry stitch. It is worked, as the back of the sampler (21) clearly shows, in quite a different way. You get there parallel rows of double stitches. Having[54] made a half-stitch entering the material at the upper edge of the work, bring the needle out on the lower edge of it immediately opposite. Then, going back, put it in at the beginning of the upper edge, and bring it out at the beginning of the lower one. Thence take a long slanting stitch upwards from left to right, bring the needle out on the lower edge immediately opposite, cross it by a rather shorter stitch from right to left, entering the stuff at the point where the first half-stitch ended, bring this out on the lower edge, opposite, and the stitch is done.

The artistic use of herring-bone-stitch is shown in the leaves of the tulip (84), and a closer variety of it in the pink, or whatever the flower may be, in the hand of the little figure on Illustration 72.

Buttonhole is more useful in ornament than one might expect a stitch with such a very utilitarian name to be. It is, as its common use would lead one to suppose, pre-eminently a one-edged stitch, a stitch with which to mark emphatically the outside edge of a form. There is, however, a two-edged variety known as ladder-stitch, shown in the two horn shapes on the sampler, Illustration 22.

By the use of two rows back to back, leaf forms may be fairly expressed. In the leaves on the sampler, the edge of the stitch is used to emphasise the mid rib, leaving a serrated edge to the leaves. The character of the stitch would have been better preserved by working the other way about, and marking the edge of the leaves by a clear-cut line, as in the case of the solid leaves in Illustration 73.

The stitch may be used for covering a ground or other broad surface, as in the pot shape (J) on the sampler, where the diaper pattern produced by its means explains itself the better for being worked in two shades of colour.

The simpler forms of the stitch are the more[56] useful. Worked in the form of a wheel, as in the rosettes at the side of the vase shape (A), the ornamental use of the stitch is obvious.

One need hardly describe Buttonhole Stitch. The simple form of it (A) is worked by (when you have brought your needle out) keeping the thread under your thumb to the right, whilst you put the needle in again at a higher point slightly to the right, and bring it out immediately below, close to where it came out before. This and other one-edged stitches of the kind are sometimes called "blanket-stitch."

The only difference between versions such as B and C on the sampler, and simple buttonhole, is that the stitches vary in length according to the worker's fancy.

The Crossed Buttonhole Stitch at E is worked by first making a stitch sloping to the right, and then a smaller buttonhole-stitch across this from the left.

The border marked D in sampler consists merely of two rows of slanting buttonhole-stitch worked one into the other. Needlewomen have wilful ways of making what should be upright stitches slant awkwardly in all manner of ways, with the result that they look as if they had been pulled out of the straight.

The border at F, known as "Tailor's Buttonhole," is worked with the firm edge from you, instead of towards you, as you work ordinary[59] buttonhole. Bringing the thread out at the upper edge of the work to the left, and letting it lie on that side, you put your needle in again still on the same edge, and bring it out, immediately below, on the lower one. You then, before drawing the thread quite through, put your needle into the loop from behind, and tighten it upwards.

the working of H on buttonhole sampler.

In order to make your ladder-stitch (G) square at the end, you begin by making a bar of the width the stitch is to be. Then, holding the thread under your thumb to the right, you put the needle in at the top of the bar and, slanting it towards the right, bring it out on a level with the other end of the bar somewhat to the right. This makes a triangle. With the point of your needle, pull the slanting thread out at the top, to form a square; insert the needle; slant it again to the right; draw it out as before, and you have your second triangle.

The difference between the working of the lattice-like band at H, and ladder-stitch G, is that, having completed your first triangle, you make, by buttonholing a stitch, a second triangle pointing the other way, which completes a rectangular shape.

In the solid work shown at J, you make five[61] buttonhole-stitches, gathering them to a point at the base, then another five, and so on. Repeat the process, this time point upwards, and you have the first band of the pot shape.

Characteristic and most beautiful use is made of buttonhole stitch in the piece of Indian work in Illustration 24, where it is outlined with chain stitch, which goes most perfectly with it.

Cut work, such as that on Illustration 65, is strengthened by outlining it in buttonhole-stitch.

Ladder-stitch occurs in the cusped shapes framing certain flowers in Illustration 72, embroidered all in blue silk on linen. It is not infrequent in Oriental work, and, in fact, goes sometimes by the name of Cretan-stitch on that account.

Feather-stitch is simply buttonholing in a slanting direction, first to the right side and then to the left, keeping the needle strokes in the centre closer together or farther apart according to the effect to be produced.

It owes its name, of course, to the more or less feathery effect resulting from its rather open character. Like buttonhole, it may be worked solid, as in the leaf and petal forms on the sampler, Illustration 25, but it is better suited to cover narrow than broad surfaces. The jagged outline which it gives makes it useful in embroidering plumage, but it is not to be confounded with what is called "plumage-stitch," which is not feather-stitch at all, but a version of satin-stitch.

The feathery stem (A) on the sampler is simply a buttonholing worked alternately from right to left and left to right.

The border line at B requires rather more explanation. Presume it to be worked vertically. Bring your needle out at the left edge of the band; put it in at the right edge immediately opposite, keeping your thread under the needle to the right;[65] bring it out again still on the right edge a little lower down, and then, keeping your thread to the left, put the needle in on the left edge, opposite to where you last brought it out, and bring it out again on the same edge a little lower down.

The border at C is merely an elaboration of the above, with three slanting stitches on each edge instead of a single one in the direction of the band.

the working of G G on feather-stitch sampler.

Bands D, E, F, G, are variations of ordinary feather-stitch, requiring no further explanation than the back view of the work (26) affords. On the face of the sampler it will be noticed that lines have been drawn for the guidance of the worker. These are always four in number, indicating at once, that the stitch is made with four strokes of the needle, and the points at which it is put in and out of the stuff.

In working G G, suppose four guiding lines to have been drawn as above—numbered, 1, 2, 3, 4, from left to right. Bring your needle out at the top of line 1. Make a chain-stitch slanting downwards from line 1 to line 2. Put your needle into line 3 about ⅛th of an inch lower down, and, slanting it upwards,[66] bring it out on line 4 level with the point where you last brought it out. Make a chain-stitch slanting downwards this time from right to left, and bring your needle out on line 3. Lastly, put your needle into line 2, ⅛th of an inch below the last stitch, and, slanting it upwards, bring it out on line 1.

Feather-stitch is not adapted to covering broad surfaces solidly, but may be used for narrow ones.

Oriental-stitch is the name given to a close kind of feather-stitch much used in Eastern work. The difference at once apparent to the eye between the two is that, whereas for the mid-rib of a band or leaf of feather-stitching (25) you have cross lines, in Oriental-stitch (27) you have a straight line—longer or shorter as the case may be.

Oriental-stitch, sometimes called "Antique-stitch," is a stitch in three strokes, just as feather-stitch is a stitch in four. It is usually worked horizontally, though shown upright on the sampler, Illustration 27. Like feather-stitch (see diagram), it is worked on four guiding lines, faintly visible on the sampler.

Stitches A, B, and C are worked in precisely the same way. Bring your needle out at the top of line 1. Keep the thread under your thumb to the right and put your needle in at the top of line 4, bringing it out into line 3 on the same level. Then put it in again at line 2, just on the other side of the thread, and bring it out on line 1 ready to begin the next stitch.

[69]It will be seen that the length of the central part (or mid-rib, as it was called above) makes the whole difference between the three varieties of stitch. In A the three parts are equal: in B the mid-rib is narrow: in C it is broad, as is most plainly seen on the back of the sampler (28). The difference is only a difference of proportion.

the working of A, B, C on oriental-stitch sampler.

The sloping stitch at D is worked in the same way as A, B, C, except that instead of straight strokes with the needle you make slanting ones.

Stitch E differs from D in that the side strokes slant both in the same direction. It is worked from right to left instead of from left to right.

Stitch F is a combination of buttonhole and Oriental stitches. Between two rows of buttonholing[70] (dark on sampler) a single row of Oriental-stitch is worked.

The stitch employed for the central stalk, G, has really no business on this sampler, except that it has something of the appearance of a continuous Oriental-stitch.

Oriental-stitch is one of the stitches used in Illustration 72.

A single sampler is devoted to Rope and Knotted Stitches, more nearly akin than they look, for rope-stitch is all but knotted as it is worked.

Rope-stitch is so called because of its appearance. It takes a large amount of silk or wool to work it, but the effect is correspondingly rich. It is worked from right to left, and is easier to work in curved lines than in straight.

Lines A on the sampler, Illustration 29, represent the ordinary appearance of the stitch; its construction is more apparent in the central stalk B, which is a less usual form of the same stitch, worked wider apart.

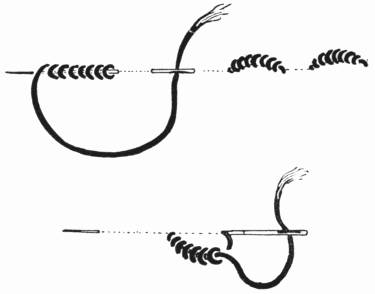

the working of A, B, on rope-stitch sampler.

Having brought out your needle at the right end of the work, hold part of the thread towards the left, under the thumb, the rest of it falling to the right; put your[72] needle in above where it came out, slant it towards you, and bring it out again a little in advance of where it came out before, and just below the thread held under your thumb. Draw the thread through, and there results a stitch which looks rather like a distorted chain stitch (B). The next step is to make another similar stitch so close to the foregoing one that it overlaps it partly. It is this overlapping which gives the stitch the raised and rope-like appearance seen at A.

the working of C on rope-stitch sampler.

A knotted line (C in the sampler, Illustration 29) is produced by what is known as "German Knot-stitch," effective only in thick soft silk or wool. Begin as in rope stitch, keeping your thread in the same position. Then put your needle into the stuff just above the thread stretched under your thumb, and bring it out just below and in a line with where it went in; lastly, keep the needle above the loose end of the thread, draw it through, tightening the thread upwards, and you have the first of your knots: the rest follow at intervals determined by your wants.

The more open stitch at D is practically the same[75] thing, except that in crossing the running thread you take up more of the stuff on each side of it.

What is known by the name of "Old English Knot-stitch" (E) is a much more complicated stitch. Keeping your thread well out of the way to the right, put your needle in to the left, and take up vertically a piece of the stuff the width of the line to be worked at its widest, and draw the thread through. Then, keeping it under the thumb to the left, put your needle, eye first, downwards, through the slanting stitch just made; draw the thread not too tight, and, keeping it as before under the thumb, put your needle, eye first, this time through the upper half only of the slanting stitch, making a kind of buttonhole-stitch round the last, and draw out your thread.

These knotted rope stitches, call them what you will, are rather ragged and fussy—not much more than fancy stitches—of no great importance. Knots used separately are of much more artistic account.

Bullion or Roll-stitch is shown in its simplest form in the petals of the flowers F on the sampler, Illustration 29. To work one such petal, begin by attaching the thread very firmly; bring your needle out at the base of the petal, put it in at the tip, and bring it out once more at the base, only drawing it partly through. With your right hand wind the thread, say seven times, round the projecting point of the needle from left to right. Then,[76] holding the coils under your left thumb, your thread to the right, draw your needle and thread through; and, dropping the needle, and catching the thread round your little finger, take hold of the thread with your thumb and first finger and draw the coiled stitch to the right, tightening it gently until quite firm. Lastly, put the needle through at the tip of the petal, and the stitch is complete and ready to be fastened off.

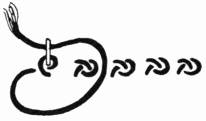

the working of F on knot-stitch sampler.

The leaves of these flowers consist simply of two bullion stitches. The bullion knots at the side of the central stalk are curled by taking up in the first instance only the smallest piece of the stuff.[77]

To work French Knots (G), having brought out your needle at the point where the knot is to be, hold the thread under your thumb, and, letting it lie to the right, put your needle under the stretched part of it. Turn the needle so as to twist the thread once round it. That done, put the needle in again about where it came out, draw it through from the back, and bring it out where the next knot is to be.

For large knots use two or more threads of silk, and do not twist them more than once. With a single thread you may twist twice, but the result of twisting three or four times is never happy.

the working of G on knot-stitch sampler.

The use of knots is shown to perfection in Illustration 24. Worked there in white silk floss upon a dark purple ground, they are quite pearly in appearance, whether in rows between the border lines, or scattered over the ground. They are most useful in holding the design together, giving it mass, and go admirably with chain-stitching, to which, when close together, they have at first sight some likeness. A single line of knots may almost be mistaken for chain-stitch; but of themselves they do not make a good outline, lacking firmness. A happier use of them is to fringe an[78] outline, as for example in the peacock's tail on page 38; but this kind of thing must be used with reticence, or it results in a rather rococo effect. Good use is sometimes made of knots to pearl the inner edge of a pattern worked in outline, or to pattern the ornament (instead of the ground) all over. Differencing of this kind may be an afterthought—and a happy one—affording as it does a ready means of qualifying the colour or texture of ground, or pattern, or part of either, which may not have worked out quite to the embroiderer's liking.

The obvious fitness of knots to represent the stamens of flowers is exemplified in Illustration 93. Worked close together, they represent admirably the eyes of composite flowers, as on the sampler; they give, again, valuable variety of texture to the crest of the stork in Illustration 85.

The effect of knotting in the mass is shown in Illustration 31, embroidered entirely in knots, contradicting, it might seem, what was said above about its unfitness for outline work. The lines, even the voided ones, are here as sharp as could be; but then, it is not many of us who work, knot by knot, with the marvellous precision of a Chinaman. His knotted texture is not, however, always what it seems. He has a way of producing a knotted line by first knotting his thread (it may be done with a netting needle), and then stitching it down on to the surface of the material, which gives a[80] pearled or beaded line not readily distinguishable from knot stitch.

The Japanese embroiderer, instead of knotting his own thread, employed very often a crinkled braid. This is shown in the cloud work in Illustration 85. The only true knotting there is in the top-knot of the bird.

The samplers so far discussed bring us, with the exception of Darning, Satin-stitch, and some stitches presently to be mentioned, practically to the end of the stitches, deserving to be so called, generally in use.

By combining two or more stitches endless complications may be made; and there may be occasions when, for one purpose or another, it may be necessary, as well as amusing, to invent them. In this way stitches are also sometimes worked upon stitches, as shown on the sampler, Illustration 32. You will see, on referring to the back of it (33), that only the white silk is worked into the stuff: the dark is surface work only. There is no end to such possible INTERLACINGS. Those on the sampler do not need much explanation; but it may be as well to say that A starts with crewel-stitching; B and C with back-stitching; D with chain-stitching; E with darning or running; F, G, and H with varieties of herring-bone-stitch; J with Oriental-stitch; and K with feather-stitch. The interlacing on the[84] surface of these is shown in darker silk. C and G undergo a second course of interlacing.

The danger of splitting the first stitches in working the interlacing ones, is avoided by passing the needle eye-first through them.

Other surface work, sometimes called LACE-STITCH, is illustrated in the sampler, Illustration 34. There is really no limit to patterns of this kind. Some are better worked in a frame, but that is very much a matter of personal practice.

the working of F on interlacing-stitch sampler.

In the Surface Darning at H (34) long threads are first carried from edge to edge of the square, there only piercing the stuff, and then darned across by other stitches, again only piercing it at the edges.

An oblique version of this is given at C (34).

The Lace Buttonholing at B (34) is worked as follows:—Buttonhole three stitches into the stuff from left to right, not quite close together, and further on three more; then, working from right to left, make three buttonhole stitches into the thread connecting the stitch groups; but do not stitch into the stuff except at the ends of the rows. The last row must, of course, be worked into the stuff again.

[86]Net Passing, as at F (34), is not very differently worked from A or B. It is much more open, and the first row of horizontal stitches is crossed by two opposite rows of oblique stitches, which are made to interlace.

The square at G is worked by first making rows of short upright stitches worked into the stuff, and then threading loose stitches through them.

The square at D is worked on the open lattice shown; the solid parts are produced by interlacing stitches from side to side, starting at the angle.

In the square at E (Japanese Darning) horizontal lines are first darned, and then zigzag lines are worked between them, much as in G; but, as they penetrate the material, this is scarcely a surface stitch.

The horizontal lines at top and bottom of the square at A are back-stitching, the intermediate ones simply long threads carried from one side to the other; they are laced together by lines looped round them.

The band at L is begun by making horizontal bar stitches. A row of crewel-stitch and one of outline-stitch, worked on to the bars, and not into the stuff, makes the central chain.

The band at K is merely surface buttonholing over a series of slanting stitches.

The band at J is buttonhole stitching wide apart, the bars filled in with surface crewel-stitch.

Most delicate surface stitching occurs in Illustration[88] 35, the fine net being worked only from edge to edge of the spaces it fills, and not elsewhere entering the stuff; which accounts for most of it being worn away. The flower or scroll-work is bonâ fide embroidery, worked through the stuff. The delicate network of fine stitching, which once covered the whole of the background, is for the most part neither more nor less than a floating gossamer of lacework. One cannot deny that that is embroidery, though it has to be said that lace-stitches are employed in it.

Stern embroiderers would like to deny it. Of course it is frivolous, and in a sense flimsy, but it is also delicate and dainty to a degree. It is suited only to dress, and that of the most exquisite kind. A French marquise of the Regency might have worn it, and possibly did wear it, with entire propriety—if the word is not out of keeping with the period.

The frailty of this kind of thing is too obvious to need mention, and that, of course, is a strong argument against it.

All attempt to give separate names to diapers of this kind, whether worked upon the surface or into the stuff, is futile. They ought not even to be called stitches, being, in fact, neither more nor less than stitch patterns, to which there is no possible limit, unless it be the limit of human invention. Every ingenious workwoman will find out patterns of her own more or less. They are very useful for[89] filling in surfaces (pattern or background) which it may be inexpedient to work more solidly.

The greater part of such patterns are geometric (Illustrations 35 and 73), following, that is to say, the mesh of the material, and making no secret of it. On Illustration 3 you see very plainly how the rectangular diaperings are built up geometrically on the square lines of the mesh, as was practically inevitable working on such a ground. The relation of stitch to stuff is here obvious.

The choice of stitch patterns of this kind is invariably left to the needlewoman. The utmost a designer need do is to indicate on his drawing that a "full," "open," or "intermediate" diaper is to be used. And the alternation of lighter and heavier diapers should be planned, and not left altogether to impulse, though the pattern may be. Moreover, there is room for the exercise of considerable taste in the choice of simpler or more elaborate patterns, freer or more geometric. Many a time the shape of the space to be filled, as well as its extent, will suggest the appropriate ornament. The diaper design is not, of course, drawn on the stuff, but points of guidance may be indicated through a kind of fine stencil plate.

The patterns used for background diapering need not, as a rule, be intrinsically so interesting as those which diaper the design itself, nor are they usually so full. They take more often the form of spot or sprig patterns, not continuous, in which the[90] geometric construction is not so obvious, nor even necessary. In either case the prime object of the stitching is not so much to make ornamental patterns as to give a tint to the stuff without entirely hiding it with work; and the worker chooses a lighter or heavier diaper according to the tint required. If the work is all in white it is texture, instead of tint, that is aimed at.

For a background, simple darning more or less open, in stitches not too regular, is often the best solution of the difficulty. The effect of the ground grinning through is delightful.

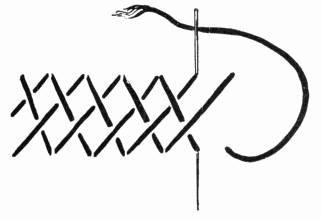

Satin-stitch is par excellence the stitch for fine silkwork. I do not know if the name of "satin-stitch" comes from its being so largely employed upon satin, or from the effect of the work itself, which would certainly justify the title, so smooth and satin-like is its surface. Given a material of which the texture is quite smooth and even, showing no mesh, satin-stitch seems the most natural and obvious way of working upon it. In it the embroidress works with short, straight strokes of the needle, just as a pen draughtsman lays side by side the strokes of his pen; but, as she cannot, of course, leave off her stroke as the penman does, she has perforce to bring back the thread on the under side of the stuff, so that, if very carefully done, the work is the same on both sides.

Satin-stitch, however, need not be, and never was, confined to work upon silk or satin. In fact, it was not only worked upon fine linen, but often followed the lines of its mesh, stepping, as in Illustration 9, to the tune of the stuff. This may be described as satin-stitch in the making—at any[92] rate, it is the elementary form of it, its relation to canvas-stitch being apparent on the face of it. Still, beautiful and most accomplished work has been done in it alike by Mediæval, Renaissance, and Oriental needleworkers.

To cover a space with regular vertical satin stitches (A on the sampler, Illustration 36), the best way of proceeding is to begin in the centre of the space and work from left to right. That half done, begin again in the centre and work from right to left.

In order to make sure of a crisp and even edge to your forms, always let the needle enter the stuff there, as it is not easy to find the point you want from the back.

In working a second row of stitches, proceed as before, only planting your needle between the stitches already done. Fasten off with a few tiny surface stitches and cut off the silk on the right side of the stuff: it will be worked over.

To cover a space with horizontal satin stitches (B on sampler), begin at the top, and work from left to right. The longer stretches there are not, of course, crossed at one stitch; they take several stitches, dovetailed, as it were, so as not to give lines.

The easiest, most satisfactory, and generally most effective way of working flat satin stitch is in oblique or radiating lines (C, D, E), working in those instances, as in the case of A, from the[95] centre, first from left to right and then from right to left.

Stems, narrow leaflets, and the like, are best worked always in stitches which run diagonally and not straight across the form.

In the case of stems or other lines curved and worked obliquely, the stitches must be very much closer on the inner side of the curve than on the outside: occasionally a half-stitch may be necessary to keep the direction of the lines right, in which case the inside end of the half-stitch must be quite covered by the stitch next following.

Satin-stitch is seen at its best when worked in floss. Coarse or twisted silk looks coarse in this stitch, as may be seen by comparing the petal D in the sampler, Illustration 36, with the petal in twisted silk here given (38). Marvellously skilful as are the needle-workers of India (Illustration 39), they get rather broken lines when they work in thick twisted silk. The precision of line a skilled worker can get in floss is wonderful. An Oriental will get sweeping lines as clean and firm as if[96] they had been drawn with a pen, and this not merely in the case of an outline, but in voided lines of which each side has to be drawn with the needle. The voided outline, by the way, as on Illustrations 39, 40, is not only the frankest way of defining form, but seems peculiarly proper to satin-stitch; and it is a test of skill in workmanship: it is so easy to disguise uneven stitching by an outline in some other stitch. The voiding in the wings of the birds in Illustration 40 is perfect; and the softening of the voided line, at the start of the wing in one case and the tail in the other, by cross stitching in threads comparatively wide apart, is quite the right thing to do. It would have been more in keeping to void the veins of the lotus leaves than to plant them on in cord.

Satin-stitch must not be too long, and it is often a serious consideration with the designer how to break up the surfaces to be covered so that only shortish stitches need be used. You might follow the veining of a leaf, for example, and work from vein to vein. But all leaves are not naturally veined in the most accommodating manner. Treatment is accordingly necessary, and so we arrive at a convention appropriate to embroidery of this kind. It takes a draughtsman properly to express form by stitch distribution. The Chinese convention in the lotus flowers (Illustration 40) is admirable.

It is the rule of the game to lay satin-stitch very evenly. Worked in floss, the mere surface of[98] satin-stitch is beautiful. A further charm lies in the way it lends itself to gradation of colour. Beautiful results may be obtained by the use of perfectly flat tints of colour, as in Illustration 40; but the subtlest as well as the most deliberate gradation of tint may be most perfectly rendered in satin-stitch.

Surface Satin-stitch (not the same on both sides), though it looks very much like ordinary satin-stitch, is worked in another way. The needle, that is to say, after each stitch is brought immediately up again, and the silk is carried back on the upper instead of the under side of the stuff. Considerable economy of silk is effected by thus keeping the thread as much as possible on the surface, but the effect is apt to be proportionately poorer. Moreover, the work is not so lasting as when it is solid. The satin-stitch on Illustration 58 is all surface work. It looks loose, which it is always apt to do, unless it is kept stretched on the frame, on which, of course, satin-stitch is for the most part worked. Very effective Indian work is done of this kind—loose and flimsy, but serving a distinct artistic purpose. It is to embroidery of more serious kind what scene painting is to mural decoration.