Transcriber's Notes:

Obvious mistakes and punctuation errors have been corrected, but

inconsistent spelling, punctuation and hyphenation has been retained.

At the end of the text there is a list of the corrections that were

made.

The footnotes in the introduction have been moved to the end of the

chapter, and have been renumbered for clarity.

Note links for the poem have been added to this version.

The Lake English Classics

REVISED EDITION WITH HELPS TO STUDY

THE

LADY OF THE LAKE

BY

SIR WALTER SCOTT

EDITED FOR SCHOOL USE

BY

WILLIAM VAUGHN MOODY

SOMETIME ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

SCOTT, FORESMAN AND COMPANY

CHICAGO ATLANTA NEW YORK

Copyright 1899, 1919

By Scott, Foresman and Company

292.46

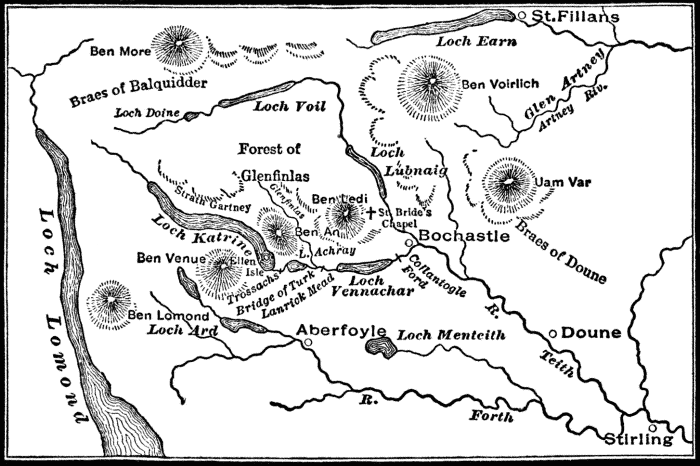

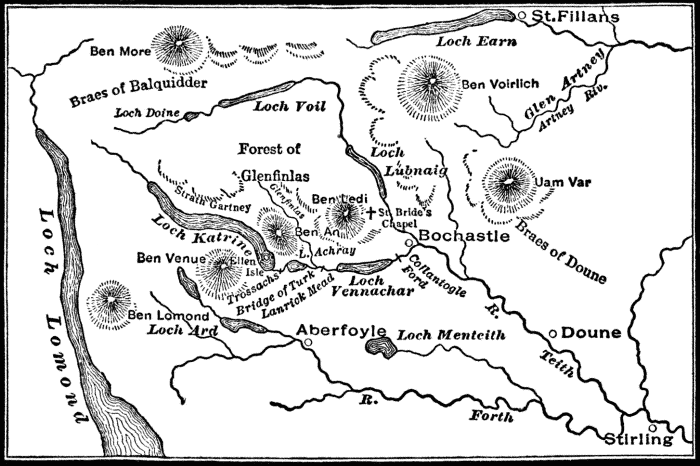

THE SCENE OF "THE LADY OF THE LAKE"

THE SCENE OF "THE LADY OF THE LAKE"

CONTENTS

|

|

|

|

PAGE |

| Map |

6 |

| Introduction |

|

I. |

Life of Scott |

9 |

|

II. |

Scott's Place in the Romantic Movement |

39 |

|

III. |

The Lady of the Lake |

|

|

|

|

Historical Setting |

46 |

|

|

|

General Criticism and Analysis |

48 |

| Text |

59 |

| Notes |

251 |

| Appendix |

|

Helps to Study |

265 |

|

Theme Subjects |

269 |

|

Selections for Class Reading |

270 |

|

Classes of Poetry |

271 |

[Pg 9]

I. LIFE OF SCOTT

I

Walter Scott was born in Edinburgh, August 15, 1771, of an ancient

Scotch clan numbering in its time many a hard rider and good fighter,

and more than one of these petty chieftains, half-shepherd and

half-robber, who made good the winter inroads into their stock of beeves

by spring forays and cattle drives across the English Border. Scott's

great-grandfather was the famous "Beardie" of Harden, so called because

after the exile of the Stuart sovereigns he swore never to cut his beard

until they were reinstated; and several degrees farther back he could

point to a still more famous figure, "Auld Wat of Harden," who with his

fair dame, the "Flower of Yarrow," is mentioned in The Lay of the Last

Minstrel. The first member of the clan to abandon country life and take

up a sedentary profession, was Scott's father, who settled in Edinburgh

as Writer to the Signet, a position corresponding in Scotland to that of

attorney or solicitor in England. The character of this father, stern,

scrupulous, Calvinistic, with a high sense of ceremonial dignity and a

punctilious regard for the honorable conventions of life, united with

the wilder ancestral strain to make Scott what he was. From "Auld Wat"

and[Pg 10] "Beardie" came his high spirit, his rugged manliness, his chivalric

ideals; from the Writer to the Signet came that power of methodical

labor which made him a giant among the literary workers of his day, and

that delicate sense of responsibility which gave his private life its

remarkable sweetness and beauty.

At the age of eighteen months, Scott was seized with a teething fever

which settled in his right leg and retarded its growth to such an extent

that he was slightly lame for the rest of his life. Possibly this

affliction was a blessing in disguise, since it is not improbable that

Scott's love of active adventure would have led him into the army or the

navy, if he had not been deterred by a bodily impediment; in which case

English history might have been a gainer, but English literature would

certainly have been immeasurably a loser. In spite of his lameness, the

child grew strong enough to be sent on a long visit to his grandfather's

farm at Sandyknowe; and here, lying among the sheep on the windy downs,

playing about the romantic ruins of Smailholm Tower,[1] scampering

through the heather on a tiny Shetland pony, or listening to stories of

the thrilling past told by the old women of the farm, he drank in

sensations which strengthened both the hardiness and the romanticism of

his nature. A story is told of his being found in the fields during a

thunder[Pg 11] storm, clapping his hands at each flash of lightning, and

shouting "Bonny! Bonny!"—a bit of infantile intrepidity which makes

more acceptable a story of another sort illustrative of his mental

precocity. A lady entering his mother's room found him reading aloud a

description of a shipwreck, accompanying the words with excited comments

and gestures. "There's the mast gone," he cried, "crash it goes; they

will all perish!" The lady entered into his agitation with tact, and on

her departure, he told his mother that he liked their visitor, because

"she was a virtuoso, like himself." To her amused inquiry as to what a

virtuoso might be, he replied: "Don't ye know? why, 'tis one who wishes

to and will know everything."

As a boy at school in Edinburgh and in Kelso, and afterwards as a

student at the University and apprentice in his father's law office,

Scott took his own way to become a "virtuoso"; a rather queer way it

must sometimes have seemed to his good preceptors. He refused

point-blank to learn Greek, and cared little for Latin. His scholarship

was so erratic that he glanced meteor-like from the head to the foot of

his classes and back again, according as luck gave or withheld the

question to which his highly selective memory had retained the answer.

But outside of school hours he was intensely at work to "know

everything," so far as "everything" came within the bounds of his

special tastes. Before[Pg 12] he was ten years old he had begun to collect

chap-books and ballads. As he grew older he read omnivorously in romance

and history; at school he learned French for the sole purpose of knowing

at first hand the fascinating cycles of old French romance; a little

later he mastered Italian in order to read Dante and Ariosto, and to his

schoolmaster's indignation stoutly championed the claim of the latter

poet to superiority over Homer; a little later he acquired Spanish and

read Don Quixote in the original. With such efforts, however,

considerable as they were for a boy who passionately loved a "bicker" in

the streets and who was famed among his comrades for bravery in climbing

the perilous "kittle nine stanes" on Castle Rock, he was not content.

Nothing more conclusively shows the genuineness of Scott's romantic

feeling than his willingness to undergo severe mental drudgery in

pursuit of knowledge concerning the old storied days which had

enthralled his imagination. It was no moonshine sentimentality which

kept him hour after hour and day after day in the Advocate's Library,

poring over musty manuscripts, deciphering heraldic devices, tracing

genealogies, and unraveling obscure points of Scottish history. By the

time he was twenty-one he had made himself, almost unconsciously, an

expert paleographer and antiquarian, whose assistance was sought by

professional workers in those branches of knowledge. Carlyle has charged

against Scott that he poured out his vast[Pg 13] floods of poetry and romance

without preparation or forethought; that his production was always

impromptu, and rooted in no sufficient past of acquisition. The charge

cannot stand. From his earliest boyhood until his thirtieth year, when

he began his brilliant career as poet and novelist, his life was one

long preparation—very individual and erratic preparation, perhaps, but

none the less earnest and fruitful.

In 1792, Scott, then twenty-one years old, was admitted a member of the

faculty of advocates of Edinburgh. During the five years which elapsed

between this date and his marriage, his life was full to overflowing of

fun and adventure, rich with genial companionship, and with experience

of human nature in all its wild and tame varieties. Ostensibly he was a

student of law, and he did, indeed, devote some serious attention to the

mastery of his profession. But the dry formalities of legal life his

keen humor would not allow him to take quite seriously. On the day when

he was called to the bar, while waiting his turn among the other young

advocates, he turned to his friend, William Clark, who had been called

with him, and whispered, mimicking the Highland lasses who used to stand

at the Cross of Edinburgh to be hired for the harvest: "We've stood here

an hour by the Tron, hinny, and deil a ane has speered[2] our price."

Though Scott never made a legal reputation, either[Pg 14] as pleader at the

bar or as an authority upon legal history and principles, it cannot be

doubted that his experience in the Edinburgh courts was of immense

benefit to him. In the first place, his study of the Scotch statutes,

statutes which had taken form very gradually under the pressure of

changing national conditions, gave him an insight into the politics and

society of the past not otherwise to have been obtained. Of still more

value, perhaps, was the association with his young companions in the

profession, and daily contact with the racy personalities which

traditionally haunt all courts of law, and particularly Scotch courts of

law: the first association kept him from the affectation and

sentimentality which is the bane of the youthful romanticist; and the

second enriched his memory with many an odd figure afterward to take its

place, clothed in the colors of a great dramatic imagination, upon the

stage of his stories.

Added to these experiences, there were others equally calculated to

enlarge his conception of human nature. Not the least among these he

found in the brilliant literary and artistic society of Edinburgh, to

which his mother's social position gave him entrance. Here, when only a

lad, he met Robert Burns, then the pet and idol of the fashionable

coteries of the capital. Here he heard Henry Mackenzie deliver a lecture

on German literature which turned his attention to the[Pg 15] romantic poetry

of Germany and led directly to his first attempts at ballad-writing. But

much more vital than any or all of these influences, were those endless

walking-tours which alone or in company with a boon companion he took

over the neighboring country-side—care-free, roystering expeditions,

which he afterwards immortalized as Dandie Dinmont's "Liddesdale raids"

in Guy Mannering. Thirty miles across country as the crow flies, with

no objective point and no errand, a village inn or a shepherd's hut at

night, with a crone to sing them an old ballad over the fire, or a group

of hardy dalesmen to welcome them with stories and carousal—these were

blithe adventurous days such as could not fail to ripen Scott's already

ardent nature, and store his memory with genial knowledge. The account

of Dandie Dinmont given by Mr. Shortreed may be taken as a picture, only

too true in some of its touches, of Scott in these youthful escapades:

"Eh me, ... sic an endless fund of humor and drollery as he had then wi'

him. Never ten yards but we were either laughing or roaring and singing.

Wherever we stopped how brawlie he suited himsel' to everybody! He aye

did as the lave did; never made himsel' the great man or took ony airs

in the company. I've seen him in a' moods in these jaunts, grave and

gay, daft and serious, sober and drunk—(this, however, even in our

wildest rambles, was but rare)—but drunk or sober, he was aye the[Pg 16]

gentleman. He looked excessively heavy and stupid when he was fou, but

he was never out o' gude humor." After this, we are not surprised to

hear that Scott's father told him disgustedly that he was better fitted

to be a fiddling peddler, a "gangrel scrape-gut," than a respectable

attorney. As a matter of fact, however, behind the mad pranks and the

occasional excesses there was a very serious purpose in all this

scouring of the country-side. Scott was picking up here and there, from

the old men and women with whom he hobnobbed, antiquarian material of an

invaluable kind, bits of local history, immemorial traditions and

superstitions, and, above all, precious ballads which had been handed

down for generations among the peasantry. These ballads, thus

precariously transmitted, it was Scott's ambition to gather together and

preserve, and he spared no pains or fatigue to come at any scrap of

ballad literature of whose existence he had an inkling. Meanwhile, he

was enriching heart and imagination for the work that was before him. So

that here also, though in the hair-brained and heady way of youth, he

was engaged in his task of preparation.

Scott has told us that it was his reading of Don Quixote which

determined him to be an author, but he was first actually excited to

composition in another way. This was by hearing recited a ballad of the

German poet Bürger, entitled Lenore, in which a skeleton lover carries

off his bride to a[Pg 17] wedding in the land of death. Mr. Hutton remarks

upon the curiousness of the fact that a piece of "raw supernaturalism"

like this should have appealed so strongly to a mind as healthy and sane

as Scott's. So it was, however. He could not rid himself of the

fascination of the piece until he had translated it, and published it,

together with another translation from the same author. One stanza at

least of this first effort of Scott sounds a note characteristic of his

poetry:

Tramp! tramp! along the land they rode,

Splash! splash! along the sea;

The scourge is red, the spur drops blood,

The flashing pebbles flee.

Here we catch the trumpet-like clang and staccato tramp of verse which

he was soon to use in a way to thrill his generation. This tiny pamphlet

of verse, Scott's earliest publication, appeared in 1796. Soon after, he

met Monk Lewis, then famous as a purveyor to English palates of the

crude horrors which German romanticism had just ceased to revel in.

Lewis was engaged in compiling a book of supernatural stories and poems

under the title of Tales of Wonder, and asked Scott to contribute.

Scott wrote for this book three long ballads—"Glenfinlas," "Cadyow

Castle," and "The Gray Brother." Though tainted with the conventional

diction of eighteenth century verse, these ballads are not unimpressive

pieces of work; the second named, especially, shows a kind and degree of

romantic[Pg 18] imagination such as his later poetry rather substantiated than

newly revealed.

II

In the following year, 1797, Scott married a Miss Charpentier, daughter

of a French refugee. She was not his first love, that place having been

usurped by a Miss Stuart Belches, for whom Scott had felt perhaps the

only deep passion of his life, and memory of whom was to come to the

surface touchingly in his old age. Miss Charpentier, or Carpenter, as

she was called, with her vivacity and quaint foreign speech "caught his

heart on the rebound"; there can be no doubt that, in spite of a certain

shallowness of character, she made him a good wife, and that his

affection for her deepened steadily to the end. The young couple went to

live at Lasswade, a village near Edinburgh, on the Esk. Scott, in whom

the proprietary instinct was always very strong, took great pride in the

pretty little cottage. He made a dining-table for it with his own hands,

planted saplings in the yard, and drew together two willow-trees at the

gate into a kind of arch, surmounted by a cross made of two sticks.

"After I had constructed this," he says, "mamma (Mrs. Scott) and I both

of us thought it so fine that we turned out to see it by moonlight, and

walked backwards from it to the cottage door, in admiration of our

magnificence and its picturesque effect." It would have been well[Pg 19]

indeed for them both if their pleasures of proprietorship could always

have remained so touchingly simple.

Now that he was married, Scott was forced to look a little more sharply

to his fortunes. He applied himself with more determination to the law.

In 1799 he became deputy-sheriff of Selkirkshire, with a salary of three

hundred pounds, which placed him at least beyond the reach of want. He

began to look more and more to literature as a means of supplementing

his income. His ballads in the Tales of Wonder had gained him some

reputation; this he increased in 1802 by the publication, under the

title Border Minstrelsy, of the ballads which he had for several years

been collecting, collating, and richly annotating. Meanwhile he was

looking about for a congenial subject upon which to try his hand in a

larger way than he had as yet adventured. Such a subject came to him at

last in a manner calculated to enlist all his enthusiasm in its

treatment, for it was given him by the Countess of Dalkeith, wife of the

heir-apparent to the dukedom of Buccleugh. The ducal house of Buccleugh

stood at the head of the clan Scott, and toward its representative the

poet always held himself in an attitude of feudal reverence. The Duke of

Buccleugh was his "chief," entitled to demand from him both passive

loyalty and active service; so, at least, Scott loved to interpret their

relationship, making effective in[Pg 20] his own case a feudal sentiment which

had elsewhere somewhat lapsed. He especially loved to think of himself

as the bard of his clan, a modern representative of those rude poets

whom the Scottish chiefs once kept as a part of their household to chant

the exploits of the clan. Nothing could have pleased his fancy more,

therefore, than a request on the part of the lady of his chief to treat

a subject of her assigning—namely, the dark mischief-making of a dwarf

or goblin who had strayed from his unearthly master and attached himself

as page to a human household. The subject fell in with the poet's

reigning taste for strong supernaturalism. Gilpin Horner, the goblin

page, though he proved in the sequel a difficult character to put to

poetic use, was a figure grotesque and eerie enough to appeal even to

Monk Lewis. At first Scott thought of treating the subject in

ballad-form, but the scope of treatment was gradually enlarged by

several circumstances. To begin with, he chanced upon a copy of Goethe's

Götz von Berlichingen, and the history of that robber baron suggested

to him the feasibility of throwing the same vivid light upon the old

Border life of his ancestors as Goethe had thrown upon that of the Rhine

barons. This led him to subordinate the part played by the goblin page

in the proposed story, which was now widened to include elaborate

pictures of medieval life and manners, and to lay the scene in the

castle of Branksome, formerly the[Pg 21] stronghold of Scott's and the Duke of

Buccleugh's ancestors. The verse form into which the story was thrown

was due to a still more accidental circumstance, i.e., Scott's

overhearing Sir John Stoddard recite a fragment of Coleridge's

unpublished poem "Christabel." The placing of the story in the mouth of

an old harper fallen upon evil days, was a happy afterthought; besides

making a beautiful framework for the main poem, it enabled the author to

escape criticism for any violent innovations of style, since these could

always be attributed to the rude and wild school of poetry to which the

harper was supposed to belong. In these ways The Lay of the Last

Minstrel gradually developed in its present form. Upon its publication

in 1805, it achieved an immediate success. The vividness of its

descriptive passages, the buoyant rush of its meter, the deep romantic

glow suffusing all its pages, took by storm a public familiar to

weariness with the decorous abstractions of the eighteenth century

poets. The first edition, a sumptuous quarto, was exhausted in a few

weeks; an octavo edition of fifteen hundred was sold out within the

year; and before 1830, forty-four thousand copies were needed to supply

the popular demand. Scott received in all something under eight hundred

pounds for the Lay, a small amount when contrasted with his gains from

subsequent poems, but a sum so unusual nevertheless that he determined[Pg 22]

forthwith to devote as much time to literature as he could spare from

his legal duties; those he still placed foremost, for until near the

close of his life he clung to his adage that literature was "a good

staff, but a poor crutch."

A year before the publication of the Lay, Scott had removed to the

small country seat of Ashestiel, in Selkirkshire, seven miles from the

nearest town, Selkirk, and several miles from any neighbor. In the

introductions to the various cantos of Marmion he has given us a

delightful picture of Ashestiel and its surroundings—the swift

Glenkinnon dashing through the estate in a deep ravine, on its way to

join the Tweed; behind the house the rising hills beyond which lay the

lovely scenery of the Yarrow. The eight years (1804–1812) at Ashestiel

were the serenest, and probably the happiest, of Scott's life. Here he

wrote his two greatest poems, Marmion and The Lady of the Lake. His

mornings he spent at his desk, always with a faithful hound at his feet

watching the tireless hand as it threw off sheet after sheet of

manuscript to make up the day's stint. By one o'clock he was, as he

said, "his own man," free to spend the remaining hours of light with his

children, his horses, and his dogs, or to indulge himself in his

life-long passion for tree-planting. His robust and healthy nature made

him excessively fond of all out-of-door sports, especially riding, in

which he was daring to foolhardiness. It is a curious fact, noted by

Lockhart,[Pg 23] that many of Scott's senses were blunt; he could scarcely,

for instance, tell one wine from another by the taste, and once sat

quite unconscious at his table while his guests were manifesting extreme

uneasiness over the approach of a too-long-kept haunch of venison, but

his sight was unusually keen, as his hunting exploits proved. His little

son once explained his father's popularity by saying that "it was him

that commonly saw the hare sitting." What with hunting, fishing,

salmon-spearing by torchlight, gallops over the hills into the Yarrow

country, planting and transplanting of his beloved trees, Scott's life

at Ashestiel, during the hours when he was "his own man," was a very

full and happy one.

Unfortunately, he had already embarked in an enterprise which was

destined to overthrow his fortunes just when they seemed fairest. While

at school in Kelso he had become intimate with a school fellow named

James Ballantyne, and later, when Ballantyne set up a small printing

house in Kelso, he had given him his earliest poems to print. After the

issue of the Border Minstrelsy, the typographical excellence of which

attracted attention even in London, he set Ballantyne up in business in

Edinburgh, secretly entering the firm himself as silent partner. The

good sale of the Lay had given the firm an excellent start; but more

matter was presently needed to feed the press. To supply it, Scott

undertook and completed at[Pg 24] Ashestiel four enormous tasks of

editing—the complete works of Dryden and of Swift, the Somers' Tracts,

and the Sadler State Papers. The success of these editions, and the

subsequent enormous sale of Scott's poems and novels, would have kept

the concern solvent in spite of Ballantyne's complete incapacity for

business, but in 1809 Scott plunged recklessly into another and more

serious venture. A dispute with Constable, the veteran publisher and

bookseller, aggravated by the harsh criticism delivered upon Marmion

by Francis Jeffrey, editor of the Edinburgh Review, Constable's

magazine, determined Scott to set up in connection with the Ballantyne

press a rival bookselling concern, and a rival magazine, to be called

the Quarterly Review. The project was a daring one, in view of

Constable's great ability and resources; to make it foolhardy to madness

Scott selected to manage the new business a brother of James Ballantyne,

a dissipated little buffoon, with about as much business ability and

general caliber of character as is connoted by the name which Scott

coined for him, "Rigdumfunnidos." The selection of such a man for such a

place betrays in Scott's eminently sane and balanced mind a curious

strain of impracticality, to say the least; indeed, we are almost

constrained to feel with his harsher critics that it betrays something

worse than defective judgment—defective character. His greatest

failing, if failing it can be called, was[Pg 25] pride. He could not endure

even the mild dictations of a competent publisher, as is shown by his

answer to a letter written by one of them proposing some salaried work;

he replied curtly that he was a "black Hussar" of literature, and not to

be put to such tame service. Probably this haughty dislike of dictation,

this imperious desire to patronize rather than be patronized, led him to

choose inferior men with whom to enter into business relations. If so,

he paid for the fault so dearly that it is hard for a biographer to

press the issue against him.

For the present, however, the wind of fortune was blowing fair, and all

the storm clouds were below the horizon. In 1808 Marmion appeared, and

was greeted with an enthusiasm which made the unprecedented reception of

the Lay seem lukewarm in comparison. Marmion contains nothing which

was not plainly foreshadowed in the Lay, but the hand of the poet has

grown more sure, his descriptive effects are less crude and amateurish,

the narrative proceeds with a steadier march, the music has gained in

volume and in martial vigor. An anecdote is told by Mr. Hutton which

will serve as a type of a hundred others illustrative of the

extraordinary hold which this poetry took upon the minds of ordinary

men. "I have heard," he says, "of two old men—complete

strangers—passing each other on a dark London night, when one of them

happened to be repeating to himself, just as[Pg 26] Campbell did to the

hackney coachman of the North Bridge of Edinburgh, the last lines of the

account of Flodden Field in Marmion, 'Charge, Chester, charge,' when

suddenly a reply came out of the darkness, 'On, Stanley, on,' whereupon

they finished the death of Marmion between them, took off their hats

to each other, and parted, laughing." The Lady of the Lake, which

followed in little more than a year, was received with the same popular

delight, and with even greater respect on the part of the critics. Even

the formidable Jeffrey, who was supposed to dine off slaughtered authors

as the Giant in "Jack and the Beanstalk" dined off young Englishmen,

keyed his voice to unwonted praise. The influx of tourists into the

Trossachs, where the scene of the poem was laid, was so great as

seriously to embarrass the mail coaches, until at last the posting

charges had to be raised in order to diminish the traffic. Far away in

Spain, at a trying moment of the Peninsular campaign, Sir Adam Ferguson,

posted on a point of ground exposed to the enemy's fire, read to his men

as they lay prostrate on the ground the passage from The Lady of the

Lake describing the combat between Roderick Dhu's Highlanders and the

forces of the Earl of Mar; and "the listening soldiers only interrupted

him by a joyous huzza when the French shot struck the bank close above

them." Such tributes—and they were legion—to the power of his poetry

to move adventurous and[Pg 27] hardy men, must have been intoxicating to

Scott; there is small wonder that the success of his poems gave him, as

he says, "such a heeze as almost lifted him off his feet."

III

Scott's modesty was not in danger, but so far as his prudence was

concerned, his success did really lift him off his feet. In 1812, still

more encouraged thereto by entering upon the emoluments of the office of

Clerk of Sessions, the duties of which he had performed for six years

without pay, he purchased Abbotsford, an estate on the Tweed, adjoining

that of the Duke of Buccleugh, his kinsman, and near the beautiful ruins

of Melrose Abbey. Here he began to carry out the dream of his life, to

found a territorial family which should augment the power and fame of

his clan. Beginning with a modest farm house and a farm of a hundred

acres, he gradually bought, planted, and built, until the farm became a

manorial domain and the farm house a castle. He had not gone far in this

work before he began to realize that the returns from his poetry would

never suffice to meet such demands as would thus be made upon his purse.

Byron's star was in the ascendant, and before its baleful magnificence

Scott's milder and more genial light visibly paled. He was himself the

first to declare, with characteristic generosity,[Pg 28] that the younger poet

had "bet"[3] him at his own craft. As Carlyle says, "he had held the

sovereignty for some half-score of years, a comparatively long lease of

it, and now the time seemed come for dethronement, for abdication. An

unpleasant business; which, however, he held himself ready, as a brave

man will, to transact with composure and in silence."

But, as it proved, there was no need for resignation. The reign of

metrical romance, brilliant but brief, was past, or nearly so. But what

of prose romance, which long ago, in picking out Don Quixote from the

puzzling Spanish, he had promised himself he would one day attempt? With

some such questioning of the Fates, Scott drew from his desk the sheets

of a story begun seven years before, and abandoned because of the

success of The Lay of the Last Minstrel. This story he now completed,

and published as Waverley in the spring of 1814—an event "memorable

in the annals of British literature; in the annals of British

bookselling thrice and four times memorable." The popularity of the

metrical romances dwindled to insignificance before the enthusiasm with

which this prose romance was received. A moment before quietly resolved

to give up his place in the world's eye, and to live the life of an

obscure country gentleman, Scott found himself launched once more on the

tide of brave fortunes.[Pg 29] The Ballantyne publishing and printing houses

ceased to totter, and settled themselves on what seemed the firmest of

foundations. At Abbotsford, buying, planting, and building began on a

greater scale than had ever been planned in its owner's most sanguine

moments.

The history of the next eleven years in Scott's life is the history, on

the one hand, of the rapidly-appearing novels, of a fame gradually

spreading outward from Great Britain until it covered the civilized

world—a fame increased rather than diminished by the incognito which

the "author of Waverley" took great pains to preserve even after the

secret had become an open one; on the other hand, of the large-hearted,

hospitable life at Abbotsford, where, in spite of the importunities of

curious and ill-bred tourists, bent on getting a glimpse of the "Wizard

of the North," and in spite of the enormous mass of work, literary and

official, which Scott took upon himself to perform, the atmosphere of

country leisure and merriment was somehow miraculously preserved. This

life of the hearty prosperous country laird was the one toward the

realization of which all Scott's efforts were directed; it is worth

while, therefore, to see as vividly as may be, what kind of life that

was, that we may the better understand what kind of man he was who cared

for it. The following extract from Lockhart's Life of Scott gives us

at least one very characteristic aspect of the Abbotsford world:

[Pg 30]"It was a clear, bright September morning, with a sharpness in the

air that doubled the animating influence of the sunshine; and all

was in readiness for a grand coursing-match on Newark Hill. The

only guest who had chalked out other sport for himself was the

staunchest of anglers, Mr. Rose; but he, too, was there on his

shelty, armed with his salmon-rod and landing-net.... This little

group of Waltonians, bound for Lord Somerville's preserve, remained

lounging about, to witness the start of the main cavalcade. Sir

Walter, mounted on Sibyl, was marshalling the order of procession

with a huge hunting-whip; and among a dozen frolicsome youths and

maidens, who seemed disposed to laugh at all discipline, appeared,

each on horseback, each as eager as the youngest sportsman in the

troop, Sir Humphrey Davy, Dr. Wollaston, and the patriarch of

Scottish belles-lettres, Henry Mackenzie.... Laidlow (the steward

of Abbotsford) on a strong-tailed wiry Highlander, yclept Hoddin

Grey, which carried him nimbly and stoutly, although his feet

almost touched the ground, was the adjutant. But the most

picturesque figure was the illustrious inventor of the safety-lamp

(Sir Humphrey Davy) ... a brown hat with flexible brim, surrounded

with line upon line of catgut, and innumerable fly-hooks; jackboots

worthy of a Dutch smuggler, and a fustian surtout dabbled with the

blood of salmon, made a fine contrast with the smart jacket,

white-cord breeches, and well-polished jockey-boots of the less

distinguished cavaliers about him. Dr. Wollaston was in black; and

with his noble serene dignity of countenance might have passed for

a sporting archbishop. Mr. Mackenzie, at this time in the

seventy-sixth year of his age, with a hat turned up[Pg 31] with green,

green spectacles, green jacket, and long brown leathern gaiters

buttoned upon his nether anatomy, wore a dog-whistle round his

neck.... Tom Purdie (one of Scott's servants) and his subalterns

had preceded us by a few hours with all the grey-hounds that could

be collected at Abbotsford, Darnick, and Melrose; but the giant

Maida had remained as his master's orderly, and now gamboled about

Sibyl Grey barking for mere joy like a spaniel puppy.

"The order of march had all been settled, when Scott's daughter

Anne broke from the line, screaming with laughter, and exclaimed,

'Papa, papa, I knew you could never think of going without your

pet!' Scott looked round, and I rather think there was a blush as

well as a smile upon his face, when he perceived a little black pig

frisking about his pony, evidently a self-elected addition to the

party of the day. He tried to look stern, and cracked his whip at

the creature, but was in a moment obliged to join in the general

cheers. Poor piggy soon found a strap round its neck, and was

dragged into the background; Scott, watching the retreat, repeated

with mock pathos, the first verse of an old pastoral song—

What will I do gin my hoggie die?

My joy, my pride, my hoggie!

My only beast, I had na mae,

And wow, but I was vogie!

—the cheers were redoubled—and the squadron moved on."

Let us supplement this with one more picture, from the same hand,

showing Scott in a little more intimate light. The passage was written

in 1821, after Lockhart had married Scott's eldest daughter,[Pg 32] and gone

to spend the summer at Chiefswood, a cottage on the Abbotsford estate:

"We were near enough Abbotsford to partake as often as we liked of

its brilliant and constantly varying society; yet could do so

without being exposed to the worry and exhaustion of spirit which

the daily reception of new-comers entailed upon all the family,

except Scott himself. But in truth, even he was not always proof

against the annoyances connected with such a style of open

house-keeping.... When sore beset at home in this way, he would

every now and then discover that he had some very particular

business to attend to on an outlying part of his estate, and

craving the indulgence of his guests overnight, appear at the cabin

in the glen before its inhabitants were astir in the morning. The

clatter of Sibyl Grey's hoofs, the yelping of Mustard and Spice,

and his own joyous shout of réveillée under our windows, were the

signal that he had burst his toils, and meant for that day to 'take

his ease in his inn.' On descending, he was found to be seated with

all his dogs and ours about him, under a spreading ash that

overshadowed half the bank between the cottage and the brook,

pointing the edge of his woodman's axe, and listening to Tom

Purdie's lecture touching the plantation that most needed thinning.

After breakfast he would take possession of a dressing-room

upstairs, and write a chapter of The Pirate; and then, having

made up and despatched his packet for Mr. Ballantyne, away to join

Purdie wherever the foresters were at work ... until it was time to

rejoin his own party at Abbotsford or the quiet circle of the

cottage. When his guests were few and friendly, he often[Pg 33] made them

come over and meet him at Chiefswood in a body towards evening....

He was ready with all sorts of devices to supply the wants of a

narrow establishment; he used to delight particularly in sinking

the wine in a well under the brae ere he went out, and hauling up

the basket just before dinner was announced,—this primitive device

being, he said, what he had always practised when a young

housekeeper, and in his opinion far superior in its results to any

application of ice; and in the same spirit, whenever the weather

was sufficiently genial, he voted for dining out of doors

altogether."

Few events of importance except the successive appearances of "our

buiks" as Tom Purdie called his master's novels, and an occasional visit

to London or the continent, intervened to break the busy monotony of

this Abbotsford life. On one of these visits to London, Scott was

invited to dine with the Prince Regent, and when the prince became King

George IV, in 1820, almost the first act of his reign was to create

Scott a baronet. Scott accepted the honor gratefully, as coming, he

said, "from the original source of all honor." There can well be two

opinions as to whether this least admirable of English kings constituted

a very prime fountain of honor, judged by democratic standards; but to

Scott's mind, such an imputation would have been next to sacrilege. The

feudal bias of his mind, strong to start with, had been strengthened by

his long sojourn among the visions of a feudal past; the ideals of

feudalism were living[Pg 34] realities to him; and he accepted knighthood from

his king's hand in exactly the same spirit which determined his attitude

of humility towards his "chief," the Duke of Buccleugh, and which

impelled him to exhaust his genius in the effort to build up a great

family estate.

There were already signs that the enormous burden of work under which he

seemed to move so lightly, was telling on him. The Bride of

Lammermoor, The Legend of Montrose, and Ivanhoe, had all of them

been dictated between screams of pain, wrung from his lips by a chronic

cramp of the stomach. By the time he reached Redgauntlet and St.

Ronan's Well, there began to be heard faint murmurings of discontent

from his public, hints that he was writing too fast, and that the noble

wine he had poured them for so long was growing at last a trifle watery.

To add to these causes of uneasiness, the commercial ventures in which

he was interested drifted again into a precarious state. He had himself

fallen into the bad habit of forestalling the gains from his novels by

heavy drafts on his publishers, and the example thus set was followed

faithfully by John Ballantyne. Scott's good humor and his partner's bad

judgment saddled the concern with a lot of unsalable books. In 1818 the

affairs of the book-selling business had to be closed up, Constable

taking over the unsalable stock and assuming the outstanding liabilities

in return for copyright privileges covering some of Scott's[Pg 35] novels.

This so burdened the veteran publisher that when, in 1825, a large

London firm failed, it carried him down also—and with him James

Ballantyne, with whom he had entered into close relations. Scott's

secret connection with Ballantyne had continued; accordingly he woke up

one fine day to find himself worse than beggared, being personally

liable for one hundred and thirty thousand pounds.

IV

The years intervening between this calamity and Scott's death form one

of the saddest and at the same time most heroic chapters in the history

of literature. The fragile health of Lady Scott succumbed almost

immediately to the crushing blow, and she died in a few months. Scott

surrendered Abbotsford to his creditors and took up humble lodgings in

Edinburgh. Here, with a pride and stoical courage as quiet as it was

splendid, he settled down to fill with the earnings of his pen the vast

gulf of debt for which he was morally scarcely responsible at all. In

three years he wrote Woodstock, three Chronicles of the Canongate,

the Fair Maid of Perth, Anne of Geierstein, the first series of the

Tales of a Grandfather, and a Life of Napoleon, equal to thirteen

volumes of novel size, besides editing and annotating a complete edition

of his own works. All these together netted his creditors £40,000.

Touched by the efforts he was[Pg 36] making to settle their claims, they now

presented him with Abbotsford, and thither he returned to spend the few

years remaining to him. In 1830 he suffered a first stroke of paralysis;

refusing to give up, however, he made one more desperate rally to

recapture his old power of story-telling. Count Robert of Paris and

Castle Dangerous were the pathetic result; they are not to be taken

into account, in any estimate of his powers, for they are manifestly the

work of a paralytic patient. The gloomy picture is darkened by an

incident which illustrates strikingly one phase of Scott's character.

The great Reform Bill was being discussed throughout Scotland, menacing

what were really abuses, but what Scott, with his intense conservatism,

believed to be sacred and inviolable institutions. The dying man roused

himself to make a stand against the abominable bill. In a speech which

he made at Jedburgh, he was hissed and hooted by the crowd, and he left

the town with the dastardly cry of "Burk Sir Walter!" ringing in his

ears.

Nature now intervened to ease the intolerable strain. Scott's anxiety

concerning his debt gradually gave way to an hallucination that it had

all been paid. His friends took advantage of the quietude which followed

to induce him to make the journey to Italy, in the fear that the severe

winter of Scotland would prove fatal. A ship of His Majesty's fleet was

put at his disposal, and he set[Pg 37] sail for Malta. The youthful

adventurousness of the man flared up again oddly for a moment, when he

insisted on being set ashore upon a volcanic island in the Mediterranean

which had appeared but a few days before and which sank beneath the

surface shortly after. The climate of Malta at first appeared to benefit

him; but when he heard, one day, of the death of Goethe at Weimar, he

seemed seized with a sudden apprehension of his own end, and insisted

upon hurrying back through Europe, in order that he might look once more

on Abbotsford. On the ride from Edinburgh he remained for the first two

stages entirely unconscious. But as the carriage entered the valley of

the Gala he opened his eyes and murmured the name of objects as they

passed, "Gala water, surely—Buckholm—Torwoodlee." When the towers of

Abbotsford came in view, he was so filled with delight that he could

scarcely be restrained from leaping out. At the gates he greeted

faithful Laidlaw in a voice strong and hearty as of old: "Why, man, how

often I have thought of you!" and smiled and wept over the dogs who came

rushing as in bygone times to lick his hand. He died a few days later,

on the afternoon of a glorious autumn day, with all the windows open, so

that he might catch to the last the whisper of the Tweed over its

pebbles.

"And so," says Carlyle, "the curtain falls; and the strong Walter Scott

is with us no more. A[Pg 38] possession from him does remain; widely

scattered; yet attainable; not inconsiderable. It can be said of him,

when he departed, he took a Man's life along with him. No sounder piece

of British manhood was put together in that eighteenth century of Time.

Alas, his fine Scotch face, with its shaggy honesty, sagacity and

goodness, when we saw it latterly on the Edinburgh streets, was all worn

with care, the joy all fled from it—plowed deep with labor and sorrow.

We shall never forget it; we shall never see it again. Adieu, Sir

Walter, pride of all Scotchmen, take our proud and sad farewell."

[Pg 39]

II. SCOTT'S PLACE IN THE ROMANTIC MOVEMENT

In order rightly to appreciate the poetry of Scott it is necessary to

understand something of that remarkable "Romantic Movement" which took

place toward the end of the eighteenth century, and within a space of

twenty-five years completely changed the face of English literature.

Both the causes and the effects of this movement were much more than

merely literary; the "romantic revival" penetrated every crevice and

ramification of life in those parts of Europe which it affected; its

social, political, and religious results were all deeply significant.

But we must here confine ourselves to such aspects of the revival as

showed themselves in English poetry.

Eighteenth century poetry had been distinguished by its polish, its

formal correctness, or—to use a term in much favor with critics of that

day—its "elegance." The various and wayward metrical effects of the

Elizabethan and Jacobean poets had been discarded for a few

well-recognized verse forms, which themselves in turn had become still

further limited by the application to them of precise rules of

structure. Hand in hand with this restricting process in meter, had gone

a similar[Pg 40] tendency in diction. The simple, concrete phrases of daily

speech had given way to stately periphrases; the rich and riotous

vocabulary of earlier poetry had been replaced by one more decorous,

measured, and high-sounding. A corresponding process of selection and

exclusion was applied to the subject matter of poetry. Passion, lyric

exaltation, delight in the concrete life of man and nature, passed out

of fashion; in their stead came social satire, criticism, generalized

observation. While the classical influence, as it is usually called, was

at its height, with such men as Dryden and Pope to exemplify it, it did

a great work; but toward the end of the eighth decade of the eighteenth

century it had visibly run to seed. The feeble Hayley, the silly Della

Crusca, the arid Erasmus Darwin, were its only exemplars. England was

ripe for a literary revolution, a return to nature and to passion; and

such a revolution was not slow in coming.

It announced itself first in George Crabbe, who turned to paint the life

of the poor with patient realism; in Burns, who poured out in his songs

the passion of love, the passion of sorrow, the passion of conviviality;

in Blake, who tried to reach across the horizon of visible fact to

mystical heavens of more enduring reality. Following close upon these

men came the four poets destined to accomplish the revolution which the

early comers had begun. They were born within four years of each other,

Wordsworth in 1770, Scott in 1771, Coleridge in[Pg 41] 1772, Southey in 1774.

As we look at these four men now, and estimate their worth as poets, we

see that Southey drops almost out of the account, and that Wordsworth

and Coleridge stand, so far as the highest qualities of poetry go, far

above Scott, as, indeed, Blake and Burns do also. But the contemporary

judgment upon them was directly the reverse; and Scott's poetry

exercised an influence over his age immeasurably greater than that of

any of the other three. Let us attempt to discover what qualities this

poetry possessed which gave it its astonishing hold upon the age when it

was written. In so doing, we may discover indirectly some of the reasons

why it still retains a large portion of its popularity, and perhaps

arrive at some grounds of judgment by which we may test its right

thereto.

One reason why Scott's poetry was immediately welcomed, while that of

Wordsworth and of Coleridge lay neglected, is to be found in the fact

that in the matter of diction Scott was much less revolutionary than

they. By nature and education he was conservative; he put The Lay of

the Last Minstrel into the mouth of a rude harper of the North in order

to shield himself from the charge of "attempting to set up a new school

in poetry," and he never throughout his life violated the conventions,

literary or social, if he could possibly avoid doing so. This bias

toward conservatism and conventionality shows itself particularly in

the[Pg 42] language of his poems. He was compelled, of course, to use much

more concrete and vivid terms than the eighteenth century poets had

used, because he was dealing with much more concrete and vivid matter;

but his language, nevertheless, has a prevailing stateliness, and at

times an artificiality, which recommended it to readers tired of the

inanities of Hayley and Mason, but unwilling to accept the startling

simplicity and concreteness of diction exemplified by the Lake poets at

their best.

Another peculiarity of Scott's poetry which made powerfully for its

popularity, was its spirited meter. People were weary of the heroic

couplet, and turned eagerly to these hurried verses, that went on their

way with the sharp tramp of moss-troopers, and heated the blood like a

drum. The meters of Coleridge, subtle, delicate, and poignant, had been

passed by with indifference—had not been heard perhaps, for lack of

ears trained to hear; but Scott's metrical effects were such as a child

could appreciate, and a soldier could carry in his head.

Analogous to this treatment of meter, though belonging to a less formal

side of his art, was Scott's treatment of nature, the landscape setting

of his stories. Perhaps the most obvious feature of the romantic revival

was a reawakening of interest in out-door nature. It was as if for a

hundred years past people had been stricken blind as soon as they passed

from the city streets into[Pg 43] the country. A trim garden, an artfully

placed country house, a well-kept preserve, they might see; but for the

great shaggy world of mountain and sea—it had been shut out of man's

elegant vision. Before Scott began to write there had been no lack of

prophets of the new nature-worship, but none of them of a sort to catch

the general ear. Wordsworth's pantheism was too mystical, too delicate

and intuitive, to recommend itself to any but chosen spirits; Crabbe's

descriptions were too minute, Coleridge's too intense, to please. Scott

was the first to paint nature with a broad, free touch, without raptures

or philosophizing, but with a healthy pleasure in its obvious beauties,

such as appeal to average men. His "scenery" seldom exists for its own

sake, but serves, as it should, for background and setting of his story.

As his readers followed the fortunes of William of Deloraine or Roderick

Dhu, they traversed by sunlight and by moonlight landscapes of wild

romantic charm, and felt their beauty quite naturally, as a part of the

excitement of that wild life. They felt it the more readily because of a

touch of artificial stateliness in the handling, a slight theatrical

heightening of effect—from an absolute point of view a defect, but

highly congenial to the taste of the time. It was the scenic side of

nature which Scott gave, and gave inimitably, while Burns was piercing

to the inner heart of her tenderness in his lines "To a Mountain[Pg 44] Daisy"

and "To a Mouse," while Wordsworth was mystically communing with her

soul, in his "Tintern Abbey." It was the scenic side of nature for which

the perceptions of men were ripe; so they left profounder poets to their

musings, and followed after the poet who could give them a brilliant

story set in a brilliant scene.

Again, the emotional key to Scott's poetry was on a comprehensible

plane. The situations with which he deals, the passions, ambitions,

satisfactions, which he portrays, belong, in one form or another, to all

men, or at least are easily grasped by the imaginations of all men. It

has often been said that Scott is the most Homeric of English poets; so

far as the claim rests on considerations of style, it is hardly to be

granted, for nothing could be farther than the hurrying torrent of

Scott's verse from the "long and refluent music" of Homer. But in this

other respect, that he deals in the rudimentary stuff of human character

in a straightforward way, without a hint of modern complexities and

super-subtleties, he is really akin to the master poet of antiquity.

This, added to the crude wild life which he pictures, the vigorous sweep

of his action, the sincere glow of romance which bathes his story—all

so tonic in their effect upon minds long used to the stuffy decorum of

didactic poetry, completed the triumph of The Lay of the Last

Minstrel, Marmion, and The Lady of the Lake, over their age.

[Pg 45]As has been already suggested, Scott cannot be put in the first rank of

poets. No compromise can be made on this point, because upon it the

whole theory of poetry depends. Neither on the formal nor on the

essential sides of his art is he among the small company of the supreme.

And no one understood this better than himself. He touched the keynote

of his own power, though with too great modesty, when he said, "I am

sensible that if there is anything good about my poetry ... it is a

hurried frankness of composition which pleases soldiers, sailors, and

young people of bold and active dispositions." The poet Campbell, who

was so fascinated by Scott's ballad of "Cadyow Castle" that he used to

repeat it aloud on the North Bridge of Edinburgh until "the whole

fraternity of coachmen knew him by tongue as he passed," characterizes

the predominant charm of Scott's poetry as lying in a "strong, pithy

eloquence," which is perhaps only another name for "hurried frankness of

composition." If this is not the highest quality to which poetry can

attain, it is a very admirable one; and it will be a sad day for the

English-speaking race when there shall not be found persons of every age

and walk of life, to take the same delights in these stirring poems as

their author loved to think was taken by "soldiers, sailors, and young

people of bold and active dispositions."

[Pg 46]

III. THE LADY OF THE LAKE

1. HISTORICAL SETTING

The Lady of the Lake deals with a distinct epoch in the life of King

James V of Scotland, and has lying back of it a considerable amount of

historical fact, an understanding of which will help in the appreciation

of the poem. During his minority the King was under the tutelage of

Archibald Douglas, sixth Earl of Angus, who had married the King's

mother. The young monarch chafed for a long time under this authority,

but the Douglases were so powerful that he was unable to shake it off,

in spite of several desperate attempts on the part of his sympathizers

to rescue him. In 1528 the King, then sixteen years of age, escaped from

his own castle of Falkland to Stirling Castle. The governor of Stirling,

an enemy of the Douglas family, received him joyfully. There soon

gathered about his standard a sufficient number of powerful peers to

enable him to depose the Earl of Angus from the regency and to banish

him and all his family to England. The Douglas who figures in the poem

is an imaginary uncle of the banished regent, and himself under the ban,

compelled to hide away in the shelter provided for him by Roderick Dhu

on the lonely island in Loch[Pg 47] Katrine. He is represented as having been

loved and trusted by King James during the boyhood of the latter, before

the enmity sprang up between the house of Angus and the throne. This

enmity, to quote from the History of the House of Douglas, published

at Edinburgh in 1743, "was so inveterate, that numerous as their allies

were, their nearest friends, even in the most remote parts of Scotland,

durst not entertain them, unless under the strictest and closest

disguise."

The outlawed border chieftain, Roderick Dhu, who gives shelter to the

persecuted Douglas, is a fictitious character, but one entirely typical

of the time and place. The expedition undertaken by the young King

against the Border clans, under the guise of a hunting party, is in

part, at least, historic. Pitscottie's History says: "In 1529 James V

made a convention at Edinburgh for the purpose of considering the best

mode of quelling the Border robbers, who, during the license of his

minority and the troubles which followed, had committed many

exorbitances. Accordingly, he assembled a flying army of ten thousand

men, consisting of his principal nobility and their followers, who were

directed to bring their hawks and dogs with them, that the monarch might

refresh himself with sport during the intervals of military execution.

With this array he swept through Ettrick forest, where he hanged over

the gate of his own castle Piers Cockburn of[Pg 48] Henderland, who had

prepared, according to tradition, a feast for his reception."

2. GENERAL CRITICISM AND ANALYSIS

The Lady of the Lake appeared in 1810. Two years before, Marmion had

vastly increased the popular enthusiasm aroused by The Lay of the Last

Minstrel, and the success of his second long poem had so exhilarated

Scott that, as he says, he "felt equal to anything and everything." To

one of his kinswomen, who urged him not to jeopardize his fame by

another effort in the same kind, he gaily quoted the words of Montrose:

He either fears his fate too much

Or his deserts are small,

Who dares not put it to the touch,

To win or lose it all.

The result justified his confidence; for not only was The Lady of the

Lake as successful as its predecessors, but it remains the most

sterling of Scott's poems. The somewhat cheap supernaturalism of the

Lay appears in it only for a moment; both the story and the characters

are of a less theatrical type than in Marmion; and it has a glow,

animation, and onset, which was denied to the later poems, Rokeby and

The Lord of the Isles.

The following outline abridged from the excellent one given by Francis

Jeffrey in the Edinburgh[Pg 49] Review for August, 1810, will be useful as a

basis for criticism of the matter and style of the poem.

"The first canto begins with a description of a staghunt in the

Highlands of Perthshire. As the chase lengthens, the sportsmen drop

off; till at last the foremost horseman is left alone; and his

horse, overcome with fatigue, stumbles and dies. The adventurer,

climbing up a craggy eminence, discovers Loch Katrine spread out in

evening glory before him. The huntsman winds his horn; and sees, to

his infinite surprise, a little skiff, guided by a lovely woman,

glide from beneath the trees that overhang the water, and approach

the shore at his feet. Upon the stranger's approach, she pushes the

shallop from the shore in alarm. After a short parley, however, she

carries him to a woody island, where she leads him into a sort of

silvan mansion, rudely constructed, and hung round with trophies of

war and the chase. An elderly lady is introduced at supper; and the

stranger, after disclosing himself to be 'James Fitz-James, the

knight of Snowdoun,' tries in vain to discover the name and history

of the ladies.

"The second canto opens with a picture of the aged harper,

Allan-bane, sitting on the island beach with the damsel, watching

the skiff which carries the stranger back to land. A conversation

ensues, from which the reader gathers that the lady is a daughter

of the Douglas, who, being exiled by royal displeasure from court,

had accepted this asylum from Sir Roderick Dhu, a Highland

chieftain long outlawed for deeds of blood; that this dark chief is

in love with his fair protégée, but that her affections are

engaged to Malcolm Graeme, a younger and more amiable mountaineer.

The sound of distant music is heard[Pg 50] on the lake; and the barges of

Sir Roderick are discovered, proceeding in triumph to the island.

Ellen, hearing her father's horn at that instant on the opposite

shore, flies to meet him and Malcolm Graeme, who is received with

cold and stately civility by the lord of the isle. Sir Roderick

informs the Douglas that his retreat has been discovered, and that

the King (James V), under pretence of hunting, has assembled a

large force in the neighborhood. He then proposes impetuously that

they should unite their fortunes by his marriage with Ellen, and

rouse the whole Western Highlands. The Douglas, intimating that his

daughter has repugnances which she cannot overcome, declares that

he will retire to a cave in the neighboring mountains until the

issue of the King's threat is seen. The heart of Roderick is wrung

with agony at this rejection; and when Malcolm advances to Ellen,

he pushes him violently back—and a scuffle ensues, which is with

difficulty appeased by the giant arm of Douglas. Malcolm then

withdraws in proud resentment, plunges into the water, and swims

over by moonlight to the mainland.

"The third canto opens with an account of the ceremonies employed

in summoning the clan. This is accomplished by the consecration of

a small wooden cross, which, with its points scorched and dipped in

blood, is carried with incredible celerity through the whole

territory of the chieftain. The eager fidelity with which this

fatal signal is carried on, is represented with great spirit. A

youth starts from the side of his father's coffin, to bear it

forward, and, having run his stage, delivers it to a young

bridegroom returning from church, who instantly binds his plaid

around him, and rushes[Pg 51] onward. In the meantime Douglas and his

daughter have taken refuge in the mountain cave; and Sir Roderick,

passing near their retreat on his way to the muster, hears Ellen's

voice singing her evening hymn to the Virgin. He does not obtrude

on her devotions, but hurries to the place of rendezvous.

"The fourth canto begins with some ceremonies by a wild hermit of

the clan, to ascertain the issue of the impending war; and this

oracle is obtained—that the party shall prevail which first sheds

the blood of its adversary. The scene then shifts to the retreat of

the Douglas, where the minstrel is trying to soothe Ellen in her

alarm at the disappearance of her father by singing a fairy ballad

to her. As the song ends, the knight of Snowdoun suddenly appears

before her, declares his love, and urges her to put herself under

his protection. Ellen throws herself on his generosity, confesses

her attachment to Graeme, and prevails on him to seek his own

safety by a speedy retreat from the territory of Roderick Dhu.

Before he goes, the stranger presents her with a ring, which he

says he has received from King James, with a promise to grant any

boon asked by the person producing it. As he retreats, his

suspicions are excited by the conduct of his guide, and confirmed

by the warnings of a mad woman whom they encounter. His false guide

discharges an arrow at him, which kills the maniac. The knight

slays the murderer; and learning from the expiring victim that her

brain had been turned by the cruelty of Sir Roderick Dhu, he vows

vengeance. When chilled with the midnight cold and exhausted with

fatigue, he suddenly comes upon a chief reposing by a lonely

watch-fire; and being challenged in the name of[Pg 52] Roderick Dhu,

boldly avows himself his enemy. The clansman, however, disdains to

take advantage of a worn-out wanderer; and pledges him safe escort

out of Sir Roderick's territory, when he must answer his defiance

with his sword. The stranger accepts these chivalrous terms; and

the warriors sup and sleep together. This ends the fourth canto.

"At dawn, the knight and the mountaineer proceed toward the Lowland

frontier. A dispute arises concerning the character of Roderick

Dhu, and the knight expresses his desire to meet in person and do

vengeance upon the predatory chief. 'Have then thy wish!' answers

his guide; and gives a loud whistle. A whole legion of armed men

start up from their mountain ambush in the heath; while the chief

turns proudly and says, 'I am Roderick Dhu!' Sir Roderick then by a

signal dismisses his men to their concealment. Arrived at his

frontier, the chief forces the knight to stand upon his defense.

Roderick, after a hard combat is laid wounded on the ground;

Fitz-James, sounding his bugle, brings four squires to his side;

and, after giving the wounded chief into their charge, gallops

rapidly on towards Stirling. As he ascends the hill to the castle,

he descries approaching the same place the giant form of Douglas,

who has come to deliver himself up to the King, in order to save

Malcolm Graeme and Sir Roderick from the impending danger. Before

entering the castle, Douglas is seized with the whim to engage in

the holiday sports which are going forward outside; he wins prize

after prize, and receives his reward from the hand of the prince,

who, however does not condescend to recognize his former favorite.

Roused at last by an insult from one of the royal[Pg 53] grooms, Douglas

proclaims himself, and is ordered into custody by the King. At this

instant a messenger arrives with tidings of an approaching battle

between the clan of Roderick and the King's lieutenant, the Earl of

Mar; and is ordered back to prevent the conflict, by announcing

that both Sir Roderick and Lord Douglas are in the hands of their

sovereign.

"The last canto opens in the guard room of the royal castle at

Stirling, at dawn. While the mercenaries are quarreling and singing

at the close of a night of debauch, the sentinels introduce Ellen

and the minstrel Allan-bane—who are come in search of Douglas.

Ellen awes the ruffian soldiery by her grace and liberality, and is

at length conducted to a more seemly waiting place, until she may

obtain audience with the King. While Allan-bane, in the cell of Sir

Roderick, sings to the dying chieftain of the glorious battle which

has just been waged by his clansmen against the forces of the Earl

of Mar, Ellen, in another part of the palace, hears the voice of

Malcolm Graeme lamenting his captivity from an adjoining turret.

Before she recovers from her agitation she is startled by the

appearance of Fitz-James, who comes to inform her that the court is

assembled, and the King at leisure to receive her suit. He conducts

her to the hall of presence, round which Ellen casts a timid and

eager glance for the monarch. But all the glittering figures are

uncovered, and James Fitz-James alone wears his cap and plume. The

Knight of Snowdoun is the King of Scotland! Struck with awe and

terror, Ellen falls speechless at his feet, pointing to the ring

which he has put upon her finger. The prince raises her with eager

kindness, declares that her father is forgiven, and[Pg 54] bids her ask

for a boon for some other person. The name of Graeme trembles on

her lips, but she cannot trust herself to utter it. The King, in

playful vengeance, condemns Malcolm Graeme to fetters, takes a

chain of gold from his own neck, and throwing it over that of the

young chief, puts the clasp in the hand of Ellen."

From this outline, it will be evident that Scott had gained greatly in

narrative power since the production of The Lay of the Last Minstrel.

Not only are the elements of the "fable" (to use the word in its

old-fashioned sense) harmonious and probable, but the various incidents

grow out of each other in a natural and necessary way. The Lay was at

best a skillful bit of carpentering whereof the several parts were

nicely juxtaposed; The Lady of the Lake is an organism, and its

several members partake of a common life. A few weaknesses may, it is

true, be pointed out in it. The warning of Fitz-James by the mad woman's

song makes too large a draft upon our romantic credulity. Her appearance

is at once so accidental and so opportune that it resembles those

supernatural interventions employed by ancient tragedy to cut the knot

of a difficult situation, which have given rise to the phrase deus ex

machina. The improbability of the episode is further increased by the

fact that she puts her warning in the form of a song. Scott's love of

romantic episode manifestly led him astray here. Further, the story as a

whole shares with all stories which turn upon the[Pg 55] revelation of a

concealed identity, the disadvantage of being able to affect the reader

powerfully but once, since on a second reading the element of suspense

and surprise is lacking. In so far as The Lady of the Lake is a mere

story, or as it has been called, a "versified novelette," this is not a

weakness; but in so far as it is a poem, with the claim which poetry

legitimately makes to be read and reread for its intrinsic beauty, it

constitutes a real defect.

Not only does this poem, with the slight exceptions just mentioned, show

a gain over the earlier poems in narrative power, but it also marks an

advance in character delineation. The characters of the Lay are, with

one or two exceptions, mere lay-figures; Lord Cranstoun and Margaret are

the most conventional of lovers; William of Deloraine is little more

than an animated suit of armor, and the Lady of Branksome, except at one

point, when from her walls she defies the English invaders, is nearly or

quite featureless. With the characters of The Lady of the Lake the

case is very different. The three rivals for Ellen's hand are real men,

with individualities which enhance and deepen the picturesqueness of

each other by contrast. The easy grace and courtly chivalry, of the

disguised King, the quick kindling of his fancy at sight of the

mysterious maid of Loch Katrine, his quick generosity in relinquishing

his suit when he finds that she loves[Pg 56] another, make him one of the most

life-like figures of romance. Roderick Dhu, nursing darkly his clannish

hatreds, his hopeless love, and his bitter jealousy, with a delicate

chivalry sending its bright thread through the tissue of his savage

nature, is drawn with an equally convincing hand. Against his gloomy

figure the boyish magnanimity of Malcolm Graeme, Ellen's brave

faithfulness, made human by a surface play of coquetry, and the quiet

nobility of the exiled Douglas, stand out in varied relief. Judged in

connection with the more conventional character types of Marmion, and

with the draped automatons of the Lay, the characters of The Lady of

the Lake show the gradual growth in Scott of that dramatic imagination

which was later to fill the vast scene of his prose romances with

unforgettable figures.

But the most significant advance which this poem shows over earlier work

is in the greater genuineness of the poetic effect. In the description,

for example, of the approach of Roderick Dhu's boats to the island,

there is a singular depth of race feeling. There is borne in upon us, as

we read, the realization of a wild and peculiar civilization; we get a

breath of poetry keen and strange, like the shrilling of the bag-pipes

across the water. Again, in the speeding of the fiery cross there is a

primitive depth of poetry which carries with it a sense of "old,

unhappy, far-off things"; it appeals to latent memories in us,[Pg 57] which

have been handed down from an ancestral past. There is nothing in either

The Lay of the Last Minstrel or Marmion to compare for natural

dramatic force with the situation in The Lady of the Lake when

Roderick Dhu whistles for his clansmen to appear, and the astonished

Fitz-James sees the lonely mountain side suddenly bristle with tartans

and spears; and the fight which follows at the ford is a real fight, in

a sense not at all to be applied to the tournaments and other

conventional encounters of the earlier poems. Even where Scott still

clung to supernatural devices to help along his story, he handles them

with much greater subtlety than he had done in his earlier efforts. The

dropping of Douglas's sword from its scabbard when his disguised enemy

enters the room, arouses the imagination without burdening it. It has

the same imaginative advantage over such an episode as that in the

Lay, where the ghost of the wizard comes to bear off the goblin page,

as suggestion always has over explicit statement. This gain in subtlety

of treatment will be made still more apparent by comparing with any

supernatural episode of the Lay, the account in The Lady of the Lake

of the unearthly parentage of Brian the Hermit.

The gain in style is less perceptible. Scott was never a great stylist;

he struck out at the very first a nervous, hurrying meter, and a strong

though rather commonplace diction, upon which[Pg 58] he never substantially

improved. Abundant action, rapid transitions, stirring descriptions,

common sentiments and ordinary language heightened by a dash of pomp and

novelty, above all a pervading animation, spirit, intrepidity—these are

the constant elements of Scott's success, present here in their

accustomed measure. In the broader sense of style, however, where the

word is understood to include all the processes leading to a given

poetical effect, The Lady of the Lake has some advantage, even over

Marmion. It contains nothing, to be sure, so fine or so typical of

Scott's peculiar power, as the account of the Battle of Flodden in

Marmion; the minstrel's recital of the battle of Beal' an Duine does

not abide the comparison. The quieter parts of The Lady of the Lake,

moreover, are sometimes disfigured by a sentimentality and "prettiness"

happily unfrequent with Scott. But the description of the approach of

Roderick Dhu's war-boats, already mentioned, the superb landscape

delineation in the fifth canto, and the beautiful twilight ending of

canto third, can well stand as prime types of Scott's stylistic power.

[Pg 59]

THE LADY OF THE LAKE

CANTO FIRST

THE CHASE

Harp of the North! that moldering long hast hung