Frontispiece. Plate 1.

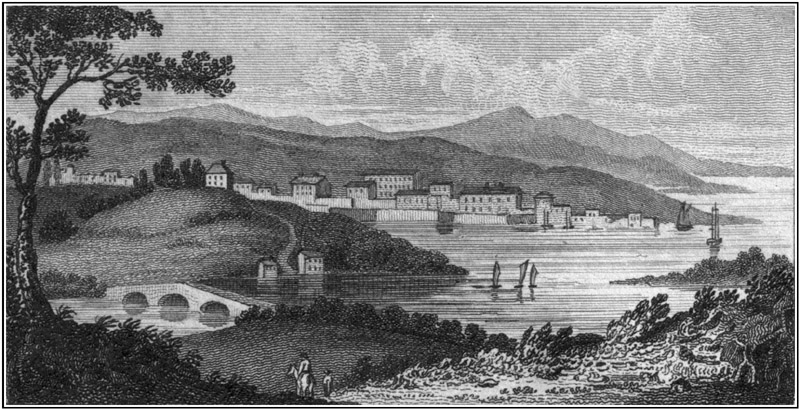

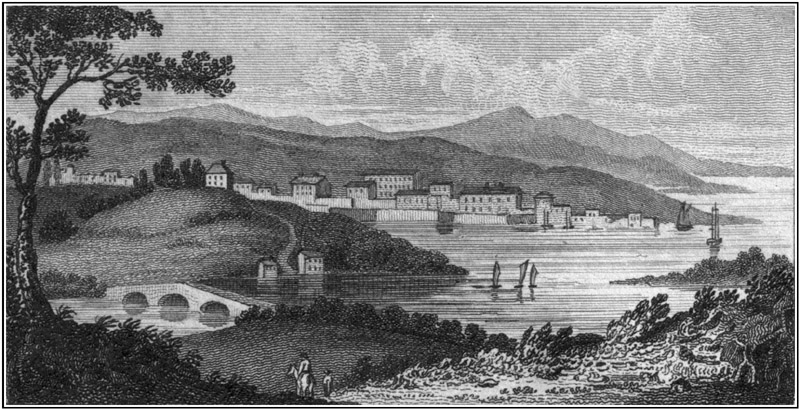

WASHINGTON.

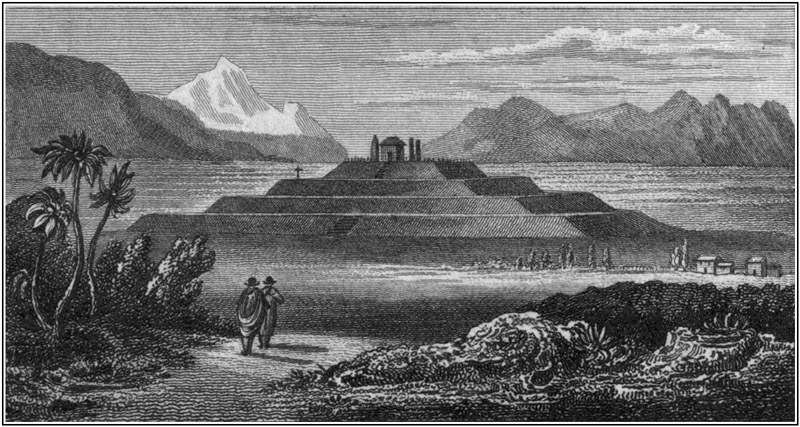

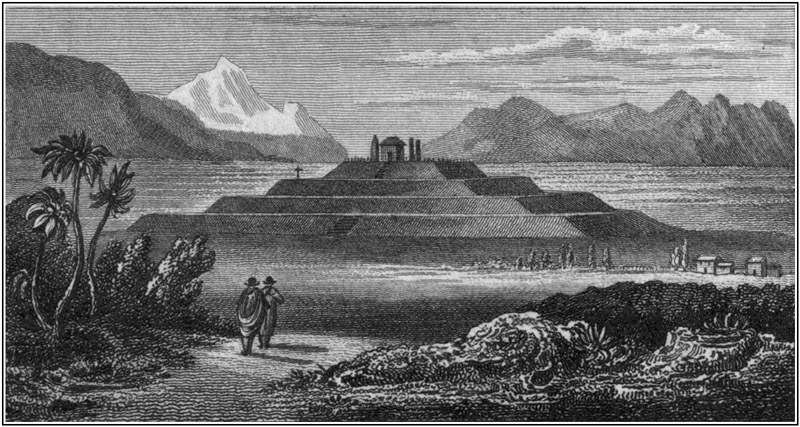

PYRAMID OF CHOLULA.

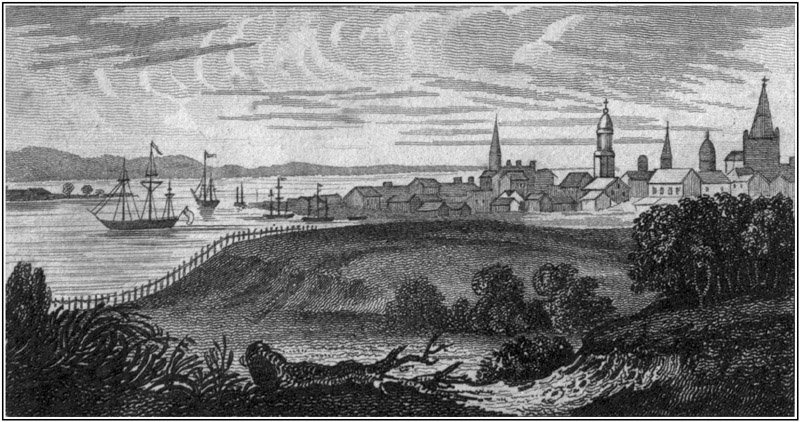

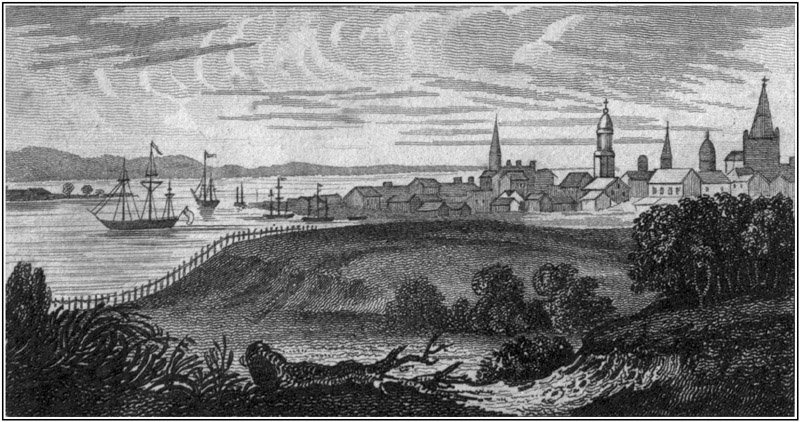

NEW YORK.

Pubd. by Harvey & Darton,

Jany. 1, 1823.

Title: Travels in North America, From Modern Writers

Author: William Bingley

Release date: March 13, 2009 [eBook #28323]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Julia Miller, Barbara Kosker and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from scans of public domain material

produced by Microsoft for their Live Search Books site.)

Frontispiece. Plate 1.

WASHINGTON.

PYRAMID OF CHOLULA.

NEW YORK.

Pubd. by Harvey & Darton,

Jany. 1, 1823.

DESIGNED FOR THE USE OF YOUNG PERSONS.

In the preparation of this, and of the preceding volumes, of Travels in the South of Europe, in South America, and in Africa; as well as in the Biographical Conversations on Celebrated Voyagers and Travellers, it has been the design of the author, by a detail of anecdotes of extraordinary adventures, connected by illustrative remarks and observations, to allure young persons to a study of geography, and to the attainment of a knowledge of the character, habits, customs, and productions of foreign nations. The whole is supposed to be related in a series of daily instructions, from a parent to his children.

The "Biographical Conversations on Celebrated Travellers," contain a further account of the United States and of Canada, in Professor's Kalm's Travels through those countries; and of the northern regions of America, in the Narratives of Hearne's Journeys from Hudson's Bay, to the Northern Ocean.

The vignette represents the natural arch, called Rockbridge, described in page 102.

Charlotte Street, Bloomsbury,

London, 22d July, 1821.

| Page | ||

| North America in General | 1 | |

| United States in General | 3 | |

| Account of New York and its vicinity. | ||

| Inhabitants of New York, 12—Situation, Streets, Population, Hotels, 13—Stores, Public Buildings, Columbia College, 14—Town Hall, Trades and Professions, 15—House-rent, Provisions, Religion, Courts of Law, 16—Long Island, New Jersey, River Hudson, Newark, Fishkill, Steam-boats, 17—Emigrants, 18. | ||

| Narrative of Fearon's Journey from New York to Boston. | ||

| New Haven, 18—New London, Norwich, New Providence, 19— Pawtucket, Boston, 20—Bunker's Hill, Cambridge, Harvard College, 21. | ||

| Weld's Voyage up the River Hudson, from New

York to Lake Champlain. |

||

| River Hudson, 22—West Point, Albany, 23—River Mohawk, Cohoz Waterfall, Saratoga, 25—Skenesborough, Lake Champlain, 26—Ticonderoga, Crown Point, 27. | ||

| Hall's Journey from Canada to the Cataract of Niagara. | ||

| Prescott, 28—River St. Lawrence, Lake Ontario, Kingston, 29—Sackett's Harbour, Watertown, Utica, 30—Skaneactas, Waterloo, Geneva, Canandaigua, Burning Spring, 32—Rochester, 33—Lewistown, Queenston, 34—York, Ancaster, Mohawk Indians, 35—Mohawk Village, 36—Falls of Niagara, 37. | ||

| Hall's Journey from Niagara to Philadelphia. | ||

| Fort Erie, Buffalo, Batavia, Caledonia, 41—Genesee River, Bath, Painted Post, 42—Susquehanna River, Wilksbarre, 43—Wyoming, Blue Ridge, Bethlehem, Nazareth, 44—Moravians, 45—Lehigh Mountain, German Town, 46. | ||

| Description of Philadelphia. | ||

| Streets, Houses, 46—Shops, Wharfs, Water-Street, Public Buildings, 47—State-house, University, Prison, 48—Markets, Inhabitants, 49—Funerals, Climate, 50—Carriages, 51— Taverns, 52—Delaware River, Schuylkil River, 53. | ||

| Trenton, College, 53—Residence of Joseph Buonaparte, 54. | ||

| Fearon's Journey from Philadelphia to Pittsburg. | ||

| Great Valley, Mines, 54—Lancaster, Harrisburgh, Carlisle, Chambersburgh, 55—London, Waggons, North Mountain, 56—Bloody Run, Bedford, Dry Ridge, Alleghany Mountains, Inhabitants, Log-houses, 57—Laurel Hill, Little Chesnut Ridge, Greensburg, Turtle Creek Hill, Inhabitants, 58— Pittsburg, 59—Manufactures, 60—Climate, American Population, 61—Farms, Emigration, 62. | ||

| Birkbeck's Expedition from Pittsburg into the Illinois Territory. | ||

| Travelling, 63—Cannonsburg, Washington in Pennsylvania, State of Ohio, Wheeling, 64—St. Clairsville, 65—Farms, Zanesville, Rushville, Lancaster, 66—Chillicothe, Pike Town, 67—Hurricane tract, 68—Lebanon, Cincinnati, Schools, 69— State of Indiana, 70—Camp Tavern, 71—Vincennes, Indians, 72—Princeton, 74—Harmony, Mount Vernon, Big Prairie, 75— Woods, and Farms, 76—Hunters, Little Wabash, Skillet Fork, 77—Shawnee Town, 78—Harmony, 79—Animals, 80—English Prairie, 81. | ||

| Weld's Excursion from Philadelphia to Washington. | ||

| Schuylkil River, Chester, Brandywine River, Wilmington, 82—Elkton, Susquehannah River, Havre de Grace, Baltimore, 83. | ||

| Description of Washington. | ||

| Origin, situation, form, Streets, Inhabitants, Capitol, 85—President's House, Post-Office, River Potomac, Tiber, 86—Markets, Shops, Inhabitants, Congress, Senate, 87—Representative Chamber, George Town, 88—Alexandria, Mount Vernon, 89. | ||

| Weld's Journey from Washington to Richmond in Virginia. | ||

| Country, 89—Hoe's Ferry, Rappahannoc River, Plantations in Virginia, 90—Tappahannoc or Hob's Hole, Urbanna, 91—Fires in the Woods, 92—Gloucester, York, Williamsburgh, College, 93—Hampton, Chesapeak, Norfolk, 94—Dismal Swamp, James River, 95—Taverns, Petersburgh, Richmond, 96—Falls of the James River, Inhabitants of Virginia, 97. | ||

| Weld's Return from Richmond to Philadelphia. | ||

| South-west or Green Mountains, Country and Animals, 98— Fire-flies, 99—Seat of Mr. Jefferson, Lynchburgh, 100—Peaks of Otter, Fincastle, Soil and Climate, 101—Sweet Springs, Jackson's Mountains, Rockbridge, 102—Maddison's Cave, Emigrants, 103—Lexington, Staunton, Winchester, Potomac River, Stupendous Scene, 104—Frederic, Philadelphia, 105. | ||

| Michaux's Journey from Pittsburgh to Lexington. | ||

| Wheeling, River Ohio, 106—Marietta, Point Pleasant, 107—Gallipoli, Alexandria, 108—Limestone, Kentucky, 109—Inhabitants, 110—Mays Lick, Lexington, 111— Louisville, 112—Caverns in Kentucky, 114. | ||

| Michaux's Journey from Lexington to Charleston. | ||

| Vineyards, 114—Kentucky River, Harrodsburgh, Mulder Hill, Barrens or Kentucky Meadows, 115—Nasheville, 117—Cairo, Fort Blount, 118—West Point, Cherokee Indians, 119— Kingstown, 120—Knoxville, Holstein River, Tavern, Macby, 121—Woods, Log-houses, Greenville, Jonesborough, 122— Alleghany Mountains, Linneville Mountains, Morganton, 123—Lincolnton, 124—Chester, Winesborough, Columbia, 125—Charleston, 126. | ||

| Description of Charleston. | ||

| Situation, Quays, 126—Streets, Houses, 127—Public Buildings, Trees in the Streets, Inhabitants, 128—Vauxhall, Hotels, Market, Provisions, 129—Marshes, 130. | ||

| Adjacent country, 130—Raleigh, Newbern, Savannah, in Georgia, 131. | ||

| Bartram's Excursion from Charleston into Georgia and West. | ||

| Augusta, 133—Country, fossil shells, Fort James, Dartmouth, 134—Indian monuments, 135—Cherokee Settlements, Sinica, 135 —Keowe, Tugilo river, 136—Sticoe, Cowe, 137—Cherokee Indians, 138—Fort James, 140—Country near the Oakmulge and Flint rivers, Uche, 141—Apalachula, Coweta, Talasse, Coloome, 142—Alabama river, Mobile, Pensacola, 144—Mobile, Pearl river, Manchac, Mississippi river, 145—Mobile, Taensa, 146—Tallapoose river, Alabama, Mucclasse, Apalachula river, Chehau, Usseta, 147—Oakmulge, Ocone river, Ogeche, Augusta, Savannah, 148. | ||

| Mr. Bartram's Journey from Savannah into East Florida. | ||

| Sunbury, 148—Fort Barrington, St. Ille's, 149—Savannahs near river St. Mary, River St. Juan, or St. John, Cowford, 150—Plantation, 151—Indian Village, 152 Charlotia or Rolle's Town, Mount Royal, 153—Lake George, Spalding's Upper Store, 154—Adventure with Alligators, 155—Alligators' nests, 157—Lake, Forests, Plantation, Hot Fountain, Upper Store, Cuscowilla, 159—Sand-hills, Half-way Pond, Turtles, Lake of Cuscowilla, 160—Alachuas and Creek or Siminole Indians, 161—Talahasochte, Little St. John's River, 162. | ||

| The River Mississippi. | ||

| Source, Length, Banks, 165—Tides, New Orleans, 166—Adjacent Country, Natchez, 167—Navigation of the Mississippi, 168— New Madrid, the Ohio, Illinois Territory, Kaskaski, 169—St. Louis, 170. | ||

| Pike's Voyage from St. Louis to the Source of the Mississippi. | ||

| St. Louis, 170—Illinois River, Buffalo River, Sac Indians, Salt River, 171—Rapids des Moines, Jowa River, Jowa Indians, Rock River, 172—Turkey River, Reynard Indians, Ouisconsin River, Pecant or Winebagoe Indians, 173—Sioux Indians, Prairie des Chiens, 174—Sauteaux or Chippeway River, Scenery of the Mississippi, Sioux village, Canoe. River, St. Croix River, 176—Cannon River, Indian Burying-place, Falls of St. Anthony, 177—Rum River, Red Cedar Lake, Beaver Islands, Corbeau or Raven River, 178—Pine Creek, Lake Clear, Clear River, Winter Quarters, Indians, 179—Falls of the Painted Rock, Pine River, Chippeway Indians, 180—Leech Lake, Pine Creek, 181—Indians, Falls of St. Anthony, Prairie des Chiens, 182—Sioux and Puant Indians, Salt River, 183. | ||

| Western Territory of America | 184 | |

| The River Missouri. Lewis and Clarke's Voyage from St. Louis to the Source o f the Missouri. |

||

| St. Louis, Osage River, Osage Indians, Big Manitou Creek, 185—Kanzes River, Platte River, 186—Pawnee Indians, Ottoe and Missouri Indians, 187—Indian Villages 188—Water of the Missouri, Fruit, Yankton Indians, 189—Teton Indians, 191— Ricara Indians, Chayenne River, 194—Le Boulet or Cannon-ball River, Mandan Indians, 196—Winter Quarters, 197—Fort Mandan, Ahanaway and Minnetaree Indians, 198—Knife River, 199—Little Missouri, Indian Burying-place, 201—Yellow Stone River, 202 —Porcupine River, Muscle-shell River, 203—Great Falls of the Missouri, 205—Maria's River, 207—Three Forks of the Missouri, 209—Source of the Missouri, 210. | ||

| Lewis and Clarke's Travels from the Source

of the Missouri to the Pacific Ocean. |

||

| Rocky Mountains, 210—Mountainous Country, Indians, 211— Travellers' Rest Creek, Koos-koos-kee River, Chopunnish Indians, 213—Shoshonees and Snake Indians, 214—Pierced-nose Indians, 217—Indian Fisheries, 218—Solkuk Indians, 218— Columbia or Oregan River, Echeloot Indians, 219—The Pacific Ocean, Indians in the Vicinity of the Coast, 221. | ||

| Lewis and Clarke's Return from the Pacific Ocean to St. Louis. | ||

| Rocky Mountains, 225—Travellers' Rest Creek, Clarke's River, Maria's River, Missouri River, 226—Yellow-stone River, Jefferson's River, 227—La Charette, St. Louis, 228. | ||

| Pike's Journey from St. Louis, through Louisiana to Santa Fé, New Spain. | ||

| Missouri River, St. Charles, Osage River, Gravel River, 229 —Yungar River, Grand Fork, Osage Indians, 230—Kanzes River, Pawnee Indians, 231—Arkansaw River, 232—Indians, 233—Grand Pawnees, Rio Colorado, 234—Rio del Norte, 236—Santa Fé, 237. | ||

| Mexico or New Spain in general | 239 | |

| Pike's Journey from Santa Fé to Montelovez | ||

| St. Domingo, Albuquerque, Sibilleta, 247—Passo del Norte, Carracal, Chihuahua, 248—Florida River, Mauperne, Hacienda of Polloss, 249—Montelovez, Durango, 250. | ||

| Description of the City of Mexico. | ||

| Situation, 250—Ancient City, 251—Quarters, Teocallis or Temples, 252—School of Mines, Valley of Mexico, 253—Streets, Aqueducts, Dikes or Embankments, Public Edifices, 254—Public Walk, Markets, Chinampas, 255—Hill of Chapoltepec, Lakes of Tezcuco and Chalco, 256. | ||

| Description of some of the most important Places in Mexico. | ||

| Tlascala, 256—Puebla, Cholula, Vera Cruz, 257—Xalapa, Volcano of Orizaba, Coffre de Perote, Volcano of Tuxtla, Papantla, Indian Pyramid, 259—Acapulco, 260—Guaxaca or Oaxaca, Intendancy of Yucatan, Bay of Campeachy, 261— Merida, Campeachy, Honduras, Balize, 262—Nicaragua, Yare River, 263—Leon de Nicaragua, 264. | ||

| British American Dominions | 264 | |

| Nova Scotia in general | ib. | |

| Halifax | 265 | |

| Canada in general | 265 | |

| Description of Quebec. | ||

| Situation, Cape Diamond, 267—Lower Town, Houses, Streets, Mountain Street, 268—Shops or Stores, Taverns, Public Buildings, Upper Town, 269—Charitable Institutions, Wolf's Cove, Heights of Abram, Markets, 270—Maple Sugar, Fruit, Climate, 271. | ||

| Mr. Hall's Journey from Quebec to Montreal. | ||

| Jacques Cartier Bridge, Cataract, Country Houses, 272— Post-houses, Trois Rivieres, River St. Maurice, Falls of Shawinne Gamme, Belœil Mountain, 273—Belœil, Montreal Mountain, 274. | ||

| Description of Montreal. | ||

| Situation, Buildings, Streets, Square, Upper and Lower Towns, Suburbs, Religious and Charitable Institutions, 275—Public Edifices, Parade, 276—Markets, Climate, 277. | ||

| Route from Montreal to Fort Chepewyan. | ||

| La Chine, 277—St. Ann's, Lake of the two Mountains, Utawas River, Portage de Chaudiere, 278—Lake Nepisingui, Nepisinguis Indians, Riviere de François, Lake Huron, Lake Superior, Algonquin Indians, 279—Grande Portage, River Au Tourt, 280— Lake Winipic, Cedar Lake, Mud Lake, Sturgeon Lake, Saskatchiwine River, Beaver Lake, Lake of the Hills, Fort Chepewyan, 281. | ||

| Account of the Knisteneaux and Chepewyan Indians. | ||

| Knisteneaux, 282—Chepewyans, 285. | ||

| Mackenzie's Voyage from Fort Chepewyan,

along the Rivers to the Frozen Ocean. |

||

| Fort Chepewyan, 288—Lake of the Hills, Slave River, Great Slave Lake, 289—Red-knife Indians, 290—Slave and Dog-rib Indians, 291—Quarreller Indians, 294—North Frozen Ocean, Whale Island, 295. | ||

| Mackenzie's Return from the Frozen Ocean to Fort Chepewyan. | ||

| Indians, 296—Account of the country, 297—Woods and Mountains, 298—Fort Chepewyan. | ||

| Description of the Western Coast of

America, from California to Behring's Strait. |

||

| California, Gulf of California, Missionary Establishment, Indians of California, 299—Monterey, New Albion, Nootka Sound, 300—Indians of Nootka Sound, 301—Port St. François, Indians, Prince William's Sound, 302—Cook's River, Alyaska, Cape Newenham, 303—Behring's Strait, Cape Prince of Wales, 304. | ||

| Davis's Strait and Baffin's Bay | 304 | |

| Ross's Voyage of Discovery, for the purpose of exploring Baffin's Bay, and enquiring into the Probability of a North-west Passage. | ||

| Cape Farewell, Icebergs, Disco Island, 305,—Kron Prin's Island, Danish Settlement, Wayat's or Hare Island, Four Island Point, Danish Factory, 306,—Esquimaux of Greenland, Danger from the Ice, Whales, 307—Arctic Highlanders, 308—Arctic Highlands, Prince Regent's Bay, 315—Sea Fowls, Crimson Snow, Cape Dudley Digges, 317—Wolstenholme and Whale Sounds, Sir Thomas Smith's Sound, Alderman Jones's Sound, Lancaster Sound, Croker Mountains, 318, 319. | ||

| Parry's Voyage for the Discovery of a North-west Passage. | ||

| Lancaster's Sound, Possession Bay, 319—Croker's Bay, Wellington Channel, Barrow's Straits, 320—Bounty Cape, Bay of the Hecla and Griper, Melville Island, 321—Cape Providence, North Georgian Islands, 322—Winter Quarters at Melville Island, 323—Cape Providence, Lancaster's Sound, Baffin's Bay, the Clyde, Esquimaux Indians, 333. | ||

| Labrador in general | 336 | |

| Greenland in general | 339 | |

| Plate | Page | |

| Vignette, Rock Bridge | 102 | |

| 1. | Washington (Frontispiece) | 85 |

| Pyramid of Cholula, near Mexico | 257 | |

| New York | 13 | |

| 2. | Philadelphia, Second Street | 46 |

| Philadelphia, United States Bank | 48 | |

| Philadelphia, High Street | 46 | |

| 3. | Quebec | 268 |

| Cataract of Niagara | 37 | |

| Montreal | 276 | |

The Binder is requested to place the Frontispiece opposite to the Title, and the above Explanation, with the other Plates, together, after the Table of Contents.

This division of the great western continent is more than five thousand miles in length; and, in some latitudes, is four thousand miles wide. It was originally discovered by Europeans, about the conclusion of the fifteenth century; and, a few years afterwards, a party of Spanish adventurers obtained possession of some of the southern districts. The inhabitants of these they treated like wild animals, who had no property in the woods through which they roamed. They expelled them from their habitations, established settlements; and, taking possession of the country in the name of their sovereign, they appropriated to themselves the choicest and most valuable provinces. Numerous other settlements have since been established in different parts of the country; and the native tribes have nearly been exterminated, while the European population and the descendants of Europeans, have so much increased that, in the United States only, there are now more than ten millions of white inhabitants.

The surface of the country is extremely varied. A [Pg 2]double range of mountains extends through the United States, in a direction, from south-west to north-east; and another range traverses nearly the whole western regions, from north to south. No part of the world is so well watered with rivulets, rivers, and lakes, as this. Some of the lakes resemble inland seas. Lake Superior is nearly 300 miles long, and is more than 150 miles wide; and lakes Huron, Michigan, Erie, Ontario, and Champlain, are all of great size. The principal navigable rivers of America are the Mississippi, the Ohio, the Missouri, and the Illinois. Of these the Mississippi flows from the north, and falls into the Gulf of Mexico. The Ohio flows into the Mississippi: it extends in a north-easterly direction, and receives fifteen large streams, all of which are navigable. The Missouri and the Illinois also flow into the Mississippi: and, by means of these several rivers, a commercial intercourse is effected, from the ocean to vast distances into the interior of the country. Other important rivers are the Delaware and the Hudson, in the United States, and the St. Lawrence, in Canada. The bays and harbours of North America are numerous, and many of them are well adapted for the reception and protection of ships. Hudson's Bay is of greater extent than the whole Baltic sea. Delaware Bay is 60 miles long; and, in some parts, is so wide, that a vessel in the middle of it cannot be seen from either bank. Chesapeak Bay extends 270 miles inland. The Bay of Honduras is on the south-eastern side of New Spain, and is noted for the trade in logwood and mahogany, which is carried on upon its banks.

The natural productions of North America are, in many respects, important. The forests abound in valuable timber-trees; among which are enumerated no fewer than forty-two different species of oaks. Fruit-trees of various kinds are abundant; and, in many places, grapes grow wild: the other vegetable productions are numerous and important. Among the quadrupeds are enumerated some small species of tigers, [Pg 3]deer, elks of immense size, bisons, bears, wolves, foxes, beavers, porcupines, and opossums. The American forests abound in birds; and in those of districts that are distant from the settlements of men, wild turkeys, and several species of grouse are very numerous. In some of the forests of Canada, passenger-pigeons breed in myriads; and, during their periodical flight, from one part of the country to another, their numbers darken the air. The coasts, bays, and rivers, abound in fish; and various species of reptiles and serpents are known to inhabit the interior of the southern districts. Among the mountains most of the important metals are found: iron, lead, and copper, are all abundant; and coals are not uncommon.

THE UNITED STATES.

That part of North America which is under the government of the United States, now constitutes one of the most powerful and most enlightened nations in the world. The inhabitants enjoy the advantage of a vast extent of territory, over which the daily increasing population is able, with facility, to expand itself; and much of this territory, though covered with forests, is capable of being cleared, and many parts of it are every day cleared, for the purposes of cultivation.

The origin of the United States may be dated from the time of the formation of an English colony in Virginia, about the year 1606. Other English colonies were subsequently formed; and, during one hundred and fifty years, these gradually increased in strength and prosperity, till, at length, the inhabitants threw off their dependance upon England, and established an independent republican government. This, after a long and expensive war, was acknowledged by Great Britain, in a treaty signed at Paris on the 30th of November, 1782.

The boundaries of the States were determined by this treaty; but, some important acquisitions of territory have since been made. In April, 1803, Louisiana was [Pg 4]ceded to them by France; and this district, in its most limited extent, includes a surface of country, which, with the exception of Russia, is equal to the whole of Europe. Florida, by its local position, is connected with the United States: it belonged to Spain, but, in the year 1820, it was annexed to the territories of the republic.

Geographical writers have divided the United States into three regions: the lowlands or flat country; the highlands, and the mountains. Of these, the first extend from the Atlantic ocean to the falls of the great rivers. The highlands reach from the falls to the foot of the mountains; and the mountains stretch nearly through the whole country, in a direction from south-west to north-east. Their length is about 900 miles, and their breadth from 60 to 200. They may be considered as separated into two distinct chains; of which the eastern chain has the name of Blue Mountains, and the western is known, at its southern extremity, by the name of Cumberland and Gauley Mountains, and afterwards by that of the Alleghany Mountains. The Alleghanies are about 250 miles distant from the shore of the Atlantic. Towards the north there are other eminences, called the Green Mountains and the White Mountains. The loftiest summits of the whole are said to be about 7000 feet in perpendicular height above the level of the sea.

Few countries can boast a greater general fertility of soil than North America. The soil of the higher lands consists, for the most part, of a brown loamy earth, and a yellowish sandy clay. Marine shells, and other substances, in a fossil state, are found at the depth of eighteen or twenty feet below the surface of the ground. Some of these are of very extraordinary description. In the year 1712, several bones and teeth of a vast nondescript quadruped, were dug up at Albany in the state of New York. By the ignorant inhabitants these were considered to be the remains of gigantic human bodies. In 1799 the bones of other individuals of this animal, [Pg 5]which has since been denominated the Mastodon or American Mammoth, were discovered beneath the surface of the ground, in the vicinity of Newburgh, on the river Hudson. Induced by the hope of being able to obtain a perfect skeleton, a Mr. Peale, of Philadelphia, purchased these bones, with the right of digging for others. He was indefatigable in his exertions, but was unable, for some time, to procure any more. He made an attempt in a morass about twelve miles distant from Newburgh, where an entire set of ribs was found, but unaccompanied by any other remains. In another morass, in Ulster county, he found several bones; among the rest a complete under jaw, and upper part of the head. From the whole of the fragments that he obtained, he was enabled to form two skeletons. One of these, under the name of mammoth, was exhibited in London, about a year afterwards. Its height at the shoulder was eleven feet; its whole length was fifteen feet; and its weight about one thousand pounds. This skeleton was furnished with large and curved ivory tusks, different in shape from those of an elephant, but similar in quality. In 1817 another skeleton was dug up, from the depth of only four feet, in the town of Goshen, near Chester. The tusks of this were more than nine feet in length.

In a region so extensive as the United States, there must necessarily be a great variety of climate. In general, the heat of summer and the cold of winter are more intense, and the transitions, from the one to the other, are more sudden than in the old continent. The predominant winds are from the west; and the severest cold is felt from the north-west. Between the forty-second and forty-fifth degrees of latitude, the same parallel as the south of France, the winters are very severe. During winter, the ice of the rivers is sufficiently strong to bear the passage of horses and waggons; and snow is so abundant, as to admit the use of sledges. In Georgia the winters are mild. South Carolina is subject to immoderate heat, to tremendous [Pg 6]hurricanes, and to terrific storms of thunder and lightning.

The United States are usually classed in three divisions: the northern, the middle, and the southern. The northern states have the general appellation of New England: they are Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. The middle states are New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana. The southern states are Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tenessee, and Louisiana.

Besides these, the United States claim the government of the territories of the Illinois, Alabama, and Mississippi. By a public ordinance, passed in the year 1787, a territory cannot be admitted into the American Union, until its population amounts to 60,000 free inhabitants. In the mean time, however, it is subject to a regular provisional form of government. The administration of this is entrusted to a governor, who is appointed by the president and congress of the United States; and who is invested with extensive powers, for protection of the interests of the States, and the observance of a strict faith towards the Indians, in the exchange of commodities, and the purchase of lands.

The government of the United States is denominated a "Federal Republic." Each state has a constitution for the management of its own internal affairs; and, by the federal constitution, they are all formed into one united body. The legislative power is vested in a congress of delegates from the several states; this congress is divided into two distinct bodies, the senate and the house of representatives. The members of the latter are elected every two years, by the people; and the senators are elected every six years, by the state legislatures. A senator must be thirty years of age, an inhabitant of the state in which he is elected, and must have been nine years a citizen of the United States: the present number of senators is thirty-eight. The executive power is vested in a president, who is chosen [Pg 7]every four years. In the election both of members of congress, and of the president of the United States, it is asserted, that there is much manœuvering, and much corrupt influence exerted. In the electioneering addresses of the defeated parties, these are, perhaps, as often made a subject of complaint and reproach, as they are in those of defeated candidates for the representation of counties or boroughs in the British House of Commons.

Washington is the seat of government; and the president, when there, lives in a house destined for his use, and furnished at the expense of the nation. His annual salary is 25,000 dollars, about £.5600 sterling. The president, in virtue of his office, is commander-in-chief of the army and navy of the United States, and also of the militia, whenever it is called into actual service. He is empowered to make treaties, to appoint ambassadors, ministers, consuls, judges of the supreme court, and all military and other officers whose appointments are not otherwise provided for by the law.

The national council is composed of the President and Vice President; and the heads of the treasury, war, navy, and post-office establishment.

The inhabitants of the United States (says Mr. Warden[1]) have not that uniform character which belongs to ancient nations, upon whom, time and the stability of institutions, have imprinted a particular and individual character. The general physiognomy is as varied as its origin is different. English, Irish, Germans, Scotch, French, and Swiss, all retain some characteristic of their ancient country.

The account given by Mr. Birkbeck is somewhat different from this. He asserts that, as far as he had an opportunity of judging, the native inhabitants of the towns are much alike; nine out of [Pg 8]ten (he says) are tall and long limbed, approaching or even exceeding six feet. They are seen in pantaloons and Wellington boots; either marching up and down, with their hands in their pockets, or seated in chairs poised on the hind feet, and the backs rested against the walls. If a hundred Americans, of any class, were to seat themselves, ninety-nine (observes this gentleman) would shuffle their chairs to the true distance, and then throw themselves back against the nearest prop. The women exhibit a great similarity of tall, relaxed forms, with consistent dress and demeanour; and are not remarkable for sprightliness of manners. Intellectual culture has not yet made much progress among the generality of either sex; but the men, from their habit of travelling, and their consequent intercourse with strangers, have greatly the advantage, in the means of acquiring information. Mr. Birkbeck says that, in every village and town, as he passed along, he observed groups of young able-bodied men, who seemed to be as perfectly at leisure as the loungers of Europe. This love of indolence, where labour is so profitable, is a strange affection. If these people be asked why they so much indulge in it, they answer, that "they live in freedom; and need not work, like the English."

In the interior of the United States, and in the back settlements, land may be purchased, both of individuals and of the government, at very low rates. The price of uncleared land, or of land covered with trees, and not yet in a state fit for cultivation, is, in many instances, as low as two dollars an acre. The public lands are divided into townships of six miles square; each of which is subdivided into thirty-six sections, of one mile square, or 640 acres; and these are usually offered for sale, in quarter sections, of 160 acres. The purchase money may be paid by four equal instalments; the first within forty days, and the others within two, three, and four years after the completion of the purchase.

Mr. Birkbeck thus describes the mode in which towns [Pg 9]are formed in America. On any spot, (says he,) where a few settlers cluster together, attracted by ancient neighbourhood, or by the goodness of the soil, or vicinity to a mill, or by whatever other cause, some enterprising proprietor perhaps finds, in his section, what he deems a good site for a town: he has it surveyed, and laid out in lots, which he sells, or offers to sale by auction. When these are disposed of, the new town assumes the name of its founder: a store-keeper builds a little framed store, and sends for a few cases of goods; and then a tavern starts up, which becomes the residence of a doctor and a lawyer, and the boarding house of the store-keeper, as well as the resort of the traveller. Soon follow a blacksmith, and other handicraftsmen, in useful succession. A school-master, who is also the minister of religion, becomes an important acquisition to this rising community. Thus the town proceeds, if it proceed at all, with accumulating force, until it becomes the metropolis of the neighbourhood. Hundreds of these speculations may have failed, but hundreds prosper; and thus trade begins and thrives, as population increases around favourite spots. The town being established, a cluster of inhabitants, however small it may be, acts as a stimulus on the cultivation of the neighbourhood: redundancy of supply is the consequence, and this demands a vent. Water-mills rise on the nearest navigable streams, and thus an effectual and constant market is secured for the increasing surplus of produce. Such are the elements of that accumulating mass of commerce which may, hereafter, render this one of the most important and most powerful countries in the world.

Though the Americans boast of the freedom which they personally enjoy, they, most inconsistently, allow the importation and employment of slaves; and, with such unjust detestation are these unhappy beings treated, that a negro is not permitted to eat at the same table, nor even to frequent the same place of worship, as a white person. The white servants, on the [Pg 10]contrary, esteem themselves on an equality with their masters. They style themselves "helps," and will not suffer themselves to be called "servants." When they speak to their masters or mistresses, they either call them by their names; or they substitute the term "boss," for that of master. All this, however, is a difference merely of words; for the Americans exhibit no greater degree of feeling, nor are they at all more considerate in their conduct towards this class of society, than the inhabitants of other nations. Indeed the contrary is very often the case. Most persons, in America, engage their servants by the week, and no enquiry is ever made relative to character, as is customary with us.

The constitution of the United States guarantees freedom of speech and liberty of the press. By law all the inhabitants are esteemed equal. The chief military strength of the country is in the militia; and, whenever this is embodied, every male inhabitant beyond a certain age, is compellable either to bear arms, or to pay an equivalent to be excused from this service. Trial by jury is to be preserved inviolate. A republican form of government is guaranteed to all the states, and hereditary titles and distinctions are prohibited by the law. With regard to religion, it is stipulated that no law shall ever be passed to establish any particular form of religion, or to prevent the free exercise of it; and, in the United States, no religious test is required as a qualification to any office of public trust.

In commerce and navigation the progress of the States has been rapid beyond example. Besides the natural advantages of excellent harbours, extensive inland bays, and navigable rivers, the Americans assert that their trade is not fettered by monopolies, nor by exclusive privileges of any description. Goods or merchandise circulate through the whole country free of duty; and a full drawback, or restitution of the duties of importation, is granted upon articles exported to a foreign port, in the course of the year in which they have been [Pg 11]imported. Commerce is here considered a highly honourable employment; and, in the sea-port towns, all the wealthiest members of the community are merchants. Nearly all the materials for manufactures are produced in this country. Fuel is inexhaustible; and the high wages of the manufacturers, and the want of an extensive capital, alone prevent the Americans from rivalling the English in trade. The produce of cultivation in America is of almost every variety that can be named: wheat, maize, rye, oats, barley, rice, and other grain; apples, pears, cherries, peaches, grapes, currants, gooseberries, plums, and other fruit, and a vast variety of vegetables. Lemons, oranges, and tropical fruits are raised in the southern States. Hops, flax, and hemp are abundant. Tobacco is an article of extensive cultivation in Virginia, Maryland, and some other districts. Cotton and sugar are staple commodities in several of the states. The northern and eastern states are well adapted for grazing, and furnish a great number of valuable horses, and of cattle and sheep; and an abundance of butter and cheese.

It will be possible to describe nearly all the most important places within the limits of the United States, by reciting, in succession, the narratives of different travellers through this interesting country. In so doing, however, it may perhaps be found requisite, in a few instances, to separate the parts of their narrations, for the purpose of more methodical illustration; but this alteration of arrangement will not often occur.

[1] Statistical, political, and historical account of the United States.

An account of New York and its vicinity. From Sketches of America by Henry Bradshaw Fearon.

Mr. Fearon was deputed by several friends in England, to visit the United States, for the purpose of obtaining information, by which they should regulate their conduct, in emigrating from their native country, to settle in America. He arrived in the bay of New York, about the beginning of August, 1817.

Here every object was interesting to him. The pilot brought on board the ship the newspapers of the morning. In these, many of the advertisements had, to Mr. Fearon, the character of singularity. One of them, announcing a play, terminated thus: "gentlemen are informed that no smoking is allowed in the theatre." Several sailing boats passed, with respectable persons in them, many of whom wore enormously large straw hats, turned up behind. At one o'clock, the vessel was anchored close to the city; and a great number of persons were collected on the wharf to witness her arrival. Many of these belonged to the labouring class; others were of the mercantile and genteeler orders. Large straw hats prevailed, and trowsers were universal. The general costume of these persons was inferior to that of men in the same rank of life in England: their whole appearance was loose, slovenly, careless, and not remarkable for cleanliness. The wholesale stores, which front the river, had not the most attractive appearance imaginable. The carts were long and narrow, and each was drawn by one horse. The hackney-coaches were open at the sides, an arrangement well suited to this warm climate; and the charge was about one fourth higher than in London.

[Pg 13]This city, when approached from the sea, presents an appearance that is truly beautiful. It stands at the extreme point of Manhattan, or York island, which is thirteen miles long, and from one to two miles wide; and the houses are built from shore to shore. Vessels of any burden can come close up to the town, and lie there in perfect safety, in a natural harbour formed by the East and Hudson's rivers. New York contains 120,000 inhabitants, and is, indisputably, the most important commercial city in America.

The streets through which Mr. Fearon passed, to a boarding-house in State-street, were narrow and dirty. The Battery, however, is a delightful walk, at the edge of the bay; and several of the houses in State-street are as large as those in Bridge-street, Blackfriars, London. At the house in which Mr. Fearon resided, the hours of eating were, breakfast, eight o'clock; dinner half-past three, tea seven, and supper ten; and the whole expence of living amounted to about eighteen dollars per week.

The street population of New York has an aspect very different from that of London, or the large towns in England. One striking feature of it is formed by the number of blacks, many of whom are finely dressed: the females are ludicrously so, generally in white muslin, with artificial flowers and pink shoes. Mr. Fearon saw very few well-dressed white ladies; but this was a time of the year when most of them were absent at the springs of Balston and Saratoga, places of fashionable resort, about 200 miles from New York.

All the native inhabitants of this city have sallow complexions. To have colour in the cheeks is here considered a criterion by which a person is known to be an Englishman. The young men are tall, thin, and solemn: they all wear trowsers, and most of them walk about in loose great coats.

There are, in New York, many hotels; some of which are on an extensive scale. The City Hotel is as large as the London Tavern. The dining-room and [Pg 14]some of the private apartments seem to have been fitted up regardless of expense. The shops, or stores, as they are here called, have nothing in their exterior to recommend them to notice: there is not even an attempt at tasteful display. In this city the linen and woollen-drapers expose great quantities of their goods, loose on boxes, in the street, without any precaution against theft. This practice, a proof of their carelessness, is at the same time an evidence as to the political state of society which is worthy of attention. Great masses of the population cannot be unemployed, or robbery would be inevitable.

There are, in New York, many excellent private dwellings, built of red painted brick, which gives them a peculiarly neat and clean appearance. In Broadway and Wall-street, trees are planted along the side of the pavement. The City Hall is a large and elegant building, in which the courts of law are held. Most of the streets are dirty: in many of them sawyers prepare their wood for sale, and all are infested with pigs.

On the whole, a walk through New York will disappoint an Englishman: there is an apparent carelessness, a laziness, an unsocial indifference, which freezes the blood and disgusts the judgment. An evening stroll along Broadway, when the lamps are lighted, will please more than one at noonday. The shops will look rather better, but the manners of the proprietors will not greatly please an Englishman: their cold indifference may be mistaken, by themselves, for independence, but no person of thought and observation will ever concede to them that they have selected a wise mode of exhibiting that dignified feeling.

[There is, in New York, a seminary for education, called Columbia College. This institution was originally named "King's College," and was founded in the year 1754. Its annual revenue is about 4000 dollars. A botanic garden, situated about four miles from the city, was, not long ago, purchased by the state, of Dr. Hosach, for 73,000 dollars, and given to the [Pg 15]college. The faculty of medicine, belonging to this institution, has been incorporated under the title of "The College of Physicians and Surgeons of the University of New York."]

The Town Hall of this city is a noble building, of white marble; and the space around it is planted and railed off. The interior appears to be well arranged. In the rooms of the mayor and corporation, are portraits of several governors of this state, and of some distinguished officers. The state rooms and courts of justice are on the first floor. In the immediate vicinity of the hall is an extensive building, appropriated to the "New York Institution," the "Academy of fine Arts," and the "American Museum." There are also a state prison, an hospital, and many splendid churches.

When a traveller surveys this city, and recollects that, but two centuries since, the spot on which it stands was a wilderness, he cannot but be surprised at its present comparative extent and opulence.

With regard to trades in New York, Mr. Fearon remarks that building appeared to be carried on to a considerable extent, and was generally performed by contract. There were many timber, or lumber-yards, (as they are here called,) but not on the same large and compact scale as in England. Cabinet-work was neatly executed, and at a reasonable price. Chair-making was an extensive business. Professional men, he says, literally swarm in the United States; and lawyers are as common in New York as paupers are in England. A gentleman, walking in the Broadway, seeing a friend pass, called out to him, "Doctor!" and immediately sixteen persons turned round, to answer the call. It is estimated that there are, in New York, no fewer than 1500 spirit shops, yet the Americans have not the character of being drunkards. There are several large carvers' and gilders' shops; and glass-mirrors and picture-frames are executed with taste and elegance. Plate-glass is imported from France, [Pg 16]Holland, and England. Booksellers' shops are extensive; but English novels and poetry are the primary articles of a bookseller's business. Many of the popular English books are here reprinted, but in a smaller size, and on worse paper than the original. There are, in this city, a few boarding-schools for ladies; but, in general, males and females, of all ages, are educated at the same establishment. No species of correction is allowed. Children, even at home, are perfectly independent; subordination being foreign to the comprehension of all persons in the United States.

The rents of houses are here extremely high. Very small houses, in situations not convenient for business, and containing, in the whole, only six rooms, are worth from £.75 to £.80 per annum; and for similar houses, in first-rate situations, the rents as high as from £.160 to £.200 are paid. Houses like those in Oxford-street and the best part of Holborn, are let for £.500 or £.600 pounds per annum.

Provisions are somewhat cheaper than in London; but most of the articles of clothing are dear, being chiefly of British manufacture. With regard to religion in the United States, there is legally the most unlimited liberty. There is no established religion; but the professors of the presbyterian and the episcopalian, or church of England tenets, take the precedence, both in numbers and respectability. Their ministers receive each from two to eight thousand dollars per annum. All the churches are said to be well filled. The episcopalians, though they do not form any part of the state, have their bishops and other orders, as in England.

Mr. Fearon remarks, generally, respecting the United States, that every industrious man may obtain a living; but that America is not the political elysium which it has been so floridly described, and which the imaginations of many have fondly anticipated.

In the courts of law there appears to be a perfect equality between the judge, the counsel, the jury, the [Pg 17]tipstaff, and the auditors; and Mr. Fearon was informed that great corruption exists in the minor courts.

New York is called a "free state;" and it may perhaps be so termed theoretically, or in comparison with its southern neighbours; but, even here, there are multitudes of negroes in a state of slavery, and who are bought and sold as cattle would be in England. And so degrading do the white inhabitants consider it, to associate with blacks, that the latter are absolutely excluded from all places of public worship, which the whites attend. Even the most degraded white person will neither eat nor walk with a negro.

Long Island is a part of the state of New York, one hundred and twenty miles in length, and twelve in breadth. It is chiefly occupied by farmers; and is divided into two counties.

Mr. Fearon made several excursions into the state of New Jersey, situated opposite to that of New York, and on the southern side of the river Hudson. The valleys abound in black oaks, ash, palms, and poplar trees. Oak and hickory-nut trees grow in situations which are overflowed. The soil is not considered prolific. Newark is a manufacturing town, in this province, of considerable importance, and delightfully situated. It contains many excellent houses, and a population of about eight thousand persons, including slaves. Carriages and chairs are here made in great numbers, chiefly for sale in the southern markets.

For the purpose of visiting the property of a gentleman who resided in the vicinity of Fishkill, a creek somewhat more than sixty miles from New York, Mr. Fearon took his passage in a steam-boat. He paid for his fare three dollars and a half, and the voyage occupied somewhat more than eight hours. The vessel was of the most splendid description. It contained one hundred and sixty beds; and the ladies had a distinct cabin. On the deck were numerous conveniences, such as baggage-rooms, smoking-rooms, &c. The general [Pg 18]occupation, during the voyage, was card-playing. In the houses of two gentlemen whom Mr. Fearon visited near Fishkill, he was much gratified by the style of living, the substantial elegance of the furniture, and the mental talents of the company. Here he found both comfort and cleanliness, requisites which are scarcely known in America.

In a general summary of his opinion respecting persons desirous of emigrating from England to America, Mr. Fearon says, that the capitalist may obtain, for his money, seven per cent. with good security. The lawyer and the doctor will not succeed. An orthodox minister would do so. The proficient in the fine arts will find little encouragement. The literary man must starve. The tutor's posts are all occupied. The shopkeeper may do as well, but not better than in London, unless he be a man of superior talent, and have a large capital: for such requisites there is a fine opening. The farmer must labour hard, and be but scantily remunerated. The clerk and shopman will get but little more than their board and lodging. Mechanics, whose trades are of the first necessity, will do well: but men who are not mechanics, and who understand only the cotton, linen, woollen, glass, earthenware, silk, or stocking manufactories, cannot obtain employment. The labouring man will do well; particularly if he have a wife and children who are capable of contributing, not merely to the consuming, but also to the earning of the common stock.

Narrative of Mr. Fearon's Journey from New York to Boston.

ON the 8th of September this gentleman left New York for Boston. After a passage of twelve hours, the vessel in which he sailed arrived at New Haven, a city in Connecticut, distant from New York, by water, about ninety miles. This place has a population of about five [Pg 19]thousand persons, and has the reputation of ranking among the most beautiful towns in the United States. [It is situated at the head of a bay, between two rivers, and contains about five hundred houses, which are chiefly built of wood, but on a regular plan: it has also several public edifices, and about four thousand inhabitants. The harbour is spacious, well protected, and has good anchorage. There is at New Haven a college, superintended by a president, a professor in divinity, and three tutors.]

From this place Mr. Fearon proceeded to New London, a small town on the west side of the river Thames. Here he took a place in the coach for Providence. American stages are a species of vehicles with which none in England can be compared. They carry twelve passengers: none outside. The coachman, or driver, sits inside with the company. In length they are nearly equal to two English stages. Few of them go on springs. The sides are open; the roof being supported by six small posts. The luggage is carried behind, and in the inside. The seats are pieces of plain board; and there are leathers which can be let down from the top, and which, though useful as a protection against wet, are of little service in cold weather.

The passengers breakfasted at Norwich, a manufacturing and trading town, about fourteen miles from New London; and, at six o'clock in the evening, they arrived at New Providence, the capital of Rhode Island, having occupied thirteen hours in travelling only fifty miles. In the general appearance of the country, Mr. Fearon had been somewhat disappointed. All the houses within sight from the road were farm-houses. He remarks that, in Connecticut and Rhode Island, the land was stony, and the price of produce was not commensurate to that of labour.

On entering Providence, Mr. Fearon was much pleased with the beauty of the place. In appearance, it combined the attractions of Southampton and Doncaster, in England. There are, in this town, an [Pg 20]excellent market-house, a workhouse, four or five public schools, an university with a tolerable library, and an hospital. Several of the churches are handsome, but they, as well as many private houses, are built of wood painted white, and have green Venetian shutters. Mr. Fearon had not seen a town either in America or Europe which bore the appearance of general prosperity, equal to Providence. Ship and house-builders were fully occupied, as indeed were all classes of mechanics. The residents of this place are chiefly native Americans; for foreign emigrants seem never to think of New England. Rent and provisions are here much lower than in New York.

At Pawtucket, four miles from Providence, are thirteen cotton manufactories; six of which are on a large scale. Mr. Fearon visited three of them. They had excellent machinery; but not more than one half of this was in operation, and the persons employed in all the manufactories combined, were not equal in number to those at one of moderate size in Lancashire.

The road from Providence to Boston is much better than that which Mr. Fearon had already passed from New London. The aspect of the country also was improved; but there was nothing in either, as to mere appearance, which would be inviting to an inhabitant of England.

From its irregularity, and from other circumstances, Boston is much more like an English town than New York. The names are English, and the inhabitants are by no means so uniformly sallow, as they are in many other parts of America. This town is considered the head quarters of Federalism in politics, and of Unitarianism in religion. It contains many rich families. The Bostonians are also the most enlightened, and the most hospitable people whom Mr. Fearon had yet seen in America: they, however, in common with all New Englanders, have the character of being greater sharpers, and more generally dishonourable, than the natives of other sections of the Union.

[Pg 21]The Athæneum public library, under the management of Mr. Shaw, is a valuable establishment. It contained, at this time, 18,000 volumes, four thousand of which were the property of the secretary of state.

The society in Boston is considered better than that in New York. Many of the richer families live in great splendour, and in houses little inferior to those of Russell-square, London. Distinctions here exist to an extent rather ludicrous under a free and popular government: there are the first class, second class, third class, and the "old families." Titles, too, are diffusely distributed.

Boston is not a thriving, that is, not an increasing town. It wants a fertile back country; and it is too far removed from the western states to have much trade.

On an eminence, in the Mall, (a fine public walk,) is built the State House, in which the legislature holds its meetings. The view from the top of this building is peculiarly fine. The islands, the shipping, the town, the hill and dale scenery, for a distance of thirty miles, present an assemblage of objects which are beautifully picturesque. Boston was the birth-place of Dr. Franklin, and in this town the first dawnings of the American revolution broke forth. The heights of Dorchester and Bunker's Hill are in its immediate vicinity.

On the 20th of September Mr. Fearon walked to Bunker's Hill. It is of moderate height. The monument, placed here in commemoration of the victory obtained by the English over the Americans, on the 17th of June, 1776, is of brick and wood, and without inscription.

[At Cambridge, four miles from Boston, is a college, called Harvard College, in honour of the Rev. John Harvard of Charleston, who left to it his library, and a considerable sum of money. This college is upon a scale so large and liberal, as to consist of seven spacious buildings, and to contain two hundred and fifty apartments for officers and students. It has an excellent library of about [Pg 22]17,000 volumes, a philosophical apparatus, and a museum of natural history. The average number of students is about two hundred and sixty. Admission into this college requires a previous knowledge of mathematics, Latin, and Greek. All the students have equal rights; and each class has peculiar instructors. Degrees are here conferred, as in the English universities; and the period of study requisite for the degree of bachelor of arts is four years. The professorships are numerous. Harvard College furnishes instructors and teachers to the most distant parts of the union; and, in general, for the extent of its funds, the richness of its library, the number and character of its establishments, and the means it affords of acquiring, not only an academical, but a professional education, it is considered to be without an equal in the country. It is, however, remarked, that this college is somewhat heretical in matters of religion; as most of the theological students leave it disaffected towards the doctrine of the Trinity.]

From this place we must return to New York, for the purpose of accompanying Mr. Weld on a voyage up the river Hudson to Lake Champlain.

Narrative of a Voyage up the River Hudson, from New York to Lake

Champlain.

By Isaac Weld, Esq.

Mr. Weld, having taken his passage in one of the sloops which trade on the North or Hudson's river, betwixt New York and Albany, embarked on the second of July. Scarcely a breath of air was stirring, and the tide carried the vessel along at the rate of about two [Pg 23]miles and a half an hour. The prospects that were presented to his view, in passing up this magnificent stream, were peculiarly grand and beautiful. In some places the river expands to the breadth of five or six miles, in others it narrows to that of a few hundred yards; and, in various parts, it is interspersed with islands. From several points of view its course can be traced to a great distance up the Hudson, whilst in others it is suddenly lost to the sight, as it winds between its lofty banks. Here mountains, covered with rocks and trees, rise almost perpendicularly out of the water; there a fine champaign country presents itself, cultivated to the very margin of the river, whilst neat farm-houses and distant towns embellish the charming landscapes.

After sunset a brisk wind sprang up, which carried the vessel at the rate of six or seven miles an hour for a considerable part of the night; but for some hours it was requisite for her to lie at anchor, in a place where the navigation of the river was intricate.

Early the next morning the voyagers found themselves opposite to West Point, a place rendered remarkable in the history of the American war, by the desertion of General Arnold, and the consequent death of the unfortunate Major André. The fort stands about one hundred and fifty feet above the level of the water, and on the side of a barren hill. It had, at this time, a most melancholy aspect. Near West Point the Highlands, as they are called, commence, and extend along the river, on each side, for several miles.

About four o'clock in the morning of the 4th of July, the vessel reached Albany, the place of its destination, one hundred and sixty miles distant from New York. Albany is a city which, at this time, contained about eleven hundred houses; and the number was fast increasing. In the old part of the town, the streets were very narrow, and the houses bad. The latter were all in the old Dutch taste, with the gable ends towards the street, and ornamented at the top with large iron weather-cocks; but in that part of the [Pg 24]town which had been lately erected, the streets were commodious, and many of the houses were handsome. Great pains had been taken to have the streets well paved and lighted. In summer time Albany is a disagreeable place; for it stands in a low situation on the margin of the river, which here runs very slowly, and which, towards the evening, often exhales clouds of vapour.

[In 1817, Albany is described, by Mr. Hall, to have had a gay and thriving appearance, and nothing Dutch about it, except the names of some of its inhabitants. Being the seat of government for New York, it has a parliament-house, dignified with the name of Capitol. This stands upon an eminence, and has a lofty columnar porch; but, as the building is small, it seems to be all porch. There is a miserable little museum here, which contains a group of waxen figures brought from France, representing the execution of Louis the Sixteenth. Albany is now a place of considerable trade; and, if a canal be completed betwixt this town and Lake Erie, it will become a town of great importance.]

The 4th of July, the day of Mr. Weld's arrival at Albany, was the anniversary of the declaration of American independence. About noon a drum and trumpet gave notice that the rejoicings would immediately commence; and, on walking to a hill, about a quarter of a mile from the town, Mr. Weld saw sixty men drawn up, partly militia, partly volunteers, partly infantry, partly cavalry. The last were clothed in scarlet, and were mounted on horses of various descriptions. About three hundred spectators attended. A few rounds from a three-pounder were fired, and some volleys of small-arms. When the firing ceased, the troops returned to the town, a party of militia officers, in uniform, marching in the rear, under the shade of umbrellas, as the day was excessively hot. Having reached the town, the whole body dispersed. The volunteers and militia officers afterwards dined together, and thus ended the rejoicings of the day.

Mr. Weld remained in Albany for a few days, and [Pg 25]then set off for Skenesborough, upon Lake Champlain, in a carriage hired for the purpose. In about two hours he arrived at the small village of Cohoz, close to which is a remarkable cataract in the Mohawk River. This river takes its rise to the north-east of Lake Oneida, and, after a course of one hundred and forty miles, joins the Hudson about ten miles above Albany. The Cohoz fall is about three miles from the mouth of this river, and at a place where its width is about three hundred yards: a ledge of rocks extends quite across the stream, and from the top of these the water falls about fifty feet perpendicular: the line of the fall, from one side of the river to the other, is nearly straight. The appearance of this cataract varies much, according to the quantity of water: when the river is full, the water descends in an unbroken sheet from one bank to the other; but, at other times, the greater part of the rocks is left uncovered.

From this place Mr. Weld proceeded along the banks of the Hudson River, and, late in the evening, reached Saratoga, thirty-five miles from Albany. This place contained about forty houses; but they were so scattered, that it had not the least appearance of a town.

Near Saratoga, on the borders of a marsh, are several remarkable mineral springs: one of these, in the crater of a rock, of pyramidical form, and about five feet in height, is particularly curious. This rock seems to have been formed by the petrifaction of the water; and all the other springs are surrounded by similar petrifactions.

Of the works thrown up at Saratoga, during the war, by the British and American armies, there were now scarcely any remains. The country around was well cultivated, and most of the trenches had been levelled by the plough. Mr. Weld here crossed the Hudson River, and proceeded, for some distance, along its eastern shore. After this the road was most wretched, particularly over a long causeway, which had been formed originally [Pg 26]for the transporting of cannon. This causeway consisted of large, trees laid side by side. Some of them being decayed, great intervals were left, in which the wheels of the carriage were sometimes locked so fast, that the horses alone could not possibly extricate them. The woods on each side of the road had a much more majestic appearance than any that Mr. Weld had seen since he had left Philadelphia. This, however, was owing more to the great height than to the thickness of the trees, for he could not see one that appeared more than thirty inches in diameter. The trees here were chiefly oaks, hiccory, hemlock, and beech; intermixed with which appeared great numbers of smooth-barked, or Weymouth pines. A profusion of wild raspberries were growing in the woods.

After having experienced almost inconceivable difficulty, in consequence of the badness of the road; and having occupied five hours in travelling only twelve miles, Mr. Weld arrived at Skenesborough. This is a little town, which stands near the southern extremity of Lake Champlain. It consisted, at this time, of only twelve houses, and was dreadfully infested with musquitoes, a large kind of gnats, which abound in the swampy parts of all hot countries. Such myriads of these insects attacked Mr. Weld, the first night of his sleeping there, that, when he rose in the morning, his face and hands were covered with large pustules, like those of a person in the small-pox. The situation of Skenesborough, on the margin of a piece of water which is almost stagnant, and which is shaded by thick woods, is peculiarly favourable to the increase of these insects.

Shortly after their arrival in Skenesborough, Mr. Weld, and two gentlemen by whom he was accompanied, hired a boat of about ten tons burden, for the purpose of crossing Lake Champlain. The vessel sailed at one o'clock in the day; but, as the channel was narrow, and the wind adverse, they were only able to proceed about six miles before sunset. Having brought the vessel [Pg 27]to an anchor, the party landed and walked to some adjacent farm-houses, in the hope of obtaining provisions; but they were not able to procure any thing except milk and cheese. The next day they reached Ticonderoga. Here the only dwelling was a tavern, a large house built of stone. On entering it, the party was shown into a spacious apartment, crowded with boatmen and other persons, who had just arrived from St. John's in Canada. The man of the house was a judge; a sullen, demure old gentleman, who sate by the fire, with tattered clothes and dishevelled locks, reading a book, and was totally regardless of every person in the house.

The old fort and barracks of Ticonderoga, are on the top of a rising ground, just behind the tavern: they were at this time in ruins, and it is not likely that they ever will be rebuilt; for the situation is a very insecure one, being commanded by a lofty hill, called Mount Defiance. During the great American war, the British troops obtained possession of this place, by dragging cannon and mortars up the hill, and firing down upon the fort.

Mr. Weld and his friends, on leaving Ticonderoga, pursued their voyage to Crown Point: Here they landed to inspect the old fort. Nothing, however, was to be seen but a heap of ruins; for, shortly before it was surrendered by the British troops, the powder-magazine blew up, and a great part of the works was destroyed; and, since the final evacuation of the place, the people of the neighbourhood have been continually digging in different parts, in the hope of procuring lead and iron shot. At the south side only the ditches remain perfect: they are wide and deep, and are cut through immense rocks of limestone; and, from being overgrown, towards the top, with different kinds of shrubs, they have a grand and picturesque appearance.

While the party were here, they were agreeably surprised with the sight of a large birch-canoe, upon the [Pg 28]lake, navigated by two or three Indians, in the dresses of their nation. These made for the shore, and soon landed; and, shortly afterwards, another party arrived, that had come by land.

Lake Champlain is about one hundred and twenty miles in length, and is of various breadths: for the first thirty miles it is, in no place, more than two miles wide; beyond this, for the distance of twelve miles, it is five or six miles across; but it afterwards narrows, and again, at the end of a few miles, expands. That part called the Broad Lake, because broader than any other, is eighteen miles across. Here the lake is interspersed with a great number of islands. The soundings of Lake Champlain are, in general, very deep; in many places they are sixty and seventy, and in some even one hundred fathoms in depth.

The scenery, along the shores of the lake, is extremely grand and picturesque; particularly beyond Crown Point. Here they are beautifully ornamented with hanging woods and rocks; and the mountains, on the western side, rise in ranges one behind another, in the most magnificent manner possible.

Crossing from the head of Lake Champlain, westward to the river St. Lawrence, we shall describe the places adjacent to that river, and some of the north-western parts of the state of New York, in

A Narrative of Lieutenant Hall's Journey from Canada to the Cataract of Niagara.

Mr. Hall had travelled from Montreal, in Canada, to Prescott, in a stage-waggon, which carried the mail; and he says that he can answer for its being one of the roughest conveyances on either side of the Atlantic.

The face of the country is invariably flat; and settlements have not, hitherto, spread far from the banks of the St. Lawrence.

[Pg 29]Prescott is remarkable for nothing but a square redoubt, or fort, called Fort Wellington. The accommodations at this place were so bad that Mr. Hall, at midnight, seated himself in a light waggon, in which two gentlemen were proceeding to Brockville. These gentlemen afterwards offered him a passage to Kingston, in a boat belonging to the British navy, which was waiting for them at Brockville.

The banks of the river St. Lawrence, from the neighbourhood of Brockville, are of limestone, and from twenty to fifty feet in height. Immense masses of reddish granite are also scattered along the bed of the stream, and sometimes project from the shore. The numerous islands which crowd the approach to Lake Ontario, have all a granite basis: they are clothed with cedar and pine-trees, and with an abundance of raspberry plants. The bed of the Gananoqua is also of granite. This river is rising into importance, from the circumstance of a new settlement being formed, under the auspices of the British government, on the waters with which it communicates.

This settlement lies at the head of the lakes of the Rideau, and, in case of another American war, is meant to secure a communication betwixt Montreal and Kingston, by way of the Utawa. The settlers are chiefly disbanded soldiers, who clear and cultivate the land, under the superintendance of officers of the quarter-master-general's department. A canal has been cut to avoid the falls of the Rideau; and the communication, either by the Gananoqua, or Kingston, will be improved by locks. Kingston, which is within the Canadian dominions, is admirably situated for naval purposes.

The basis of the soil on which this town is situated is limestone, disposed in horizontal strata. Kingston contains some good houses and stores; a small theatre, built by the military, for private theatricals; a large wooden government house, and all the appendages of an extensive military and naval establishment; with as [Pg 30]much society as can reasonably be expected, in a town but lately created from the "howling desert." The adjacent country is flat, stony, and barren. Mr. Hall says that fleets of ships occasionally lie off Kingston, several of which are as large as any on the ocean. Vessels of large dimensions were at this time building, on the spot where, a few months before, their frame-timbers had been growing.

Mr. Hall left Kingston, in a packet, for the American station of Sackett's harbour. This, after Kingston, has a mean appearance: its situation is low, its harbour is small, and its fortifications are of very different construction, both as to form and materials, from those of the former town. The navy-yard consists merely of a narrow tongue of land, the point of which affords just space sufficient for the construction of one first-rate vessel; with room for work-shops, and stores, on the remaining part of it. One of the largest vessels in the world, was at this time on the stocks. The town consists of a long street, in the direction of the river, with a few smaller streets crossing it at right angles: it covers less ground than Kingston, and has fewer good houses; but it has an advantage which Kingston does not possess, in a broad flagged footway.

The distance from Sackett's harbour to Watertown is about ten miles. This is an elegant village on the Black River. It contains about twelve hundred inhabitants, chiefly emigrants from New England. The houses are, for the most part, of wood, but tastefully finished; and a few are built of bricks.

At Watertown there was a good tavern, which afforded to Mr. Hall and his companions a luxury unusual in America, a private sitting-room, and dinner at an hour appointed by themselves. Within a few miles of Watertown the country rises boldly, and presents a refreshing contrast, of hill and valley, to the flat, heavy woods, through which they had been labouring from Sackett's harbour.

Utica, the town at which the travellers next arrived [Pg 31]stands on the right bank of the River Mohawk, over which it is approached by a covered wooden bridge, of considerable length. The appearance of this town is highly prepossessing: the streets are spacious; the houses are large and well built; and the stores, the name given to shops throughout America, are as well supplied, and as handsomely fitted up, as those of New York or Philadelphia.

There are at Utica two hotels, on a large scale; one of which, the York House, was equal in arrangement and accommodation, to any hotel beyond the Atlantic: it was kept by an Englishman from Bath. The inhabitants, from three to four thousand in number, maintained four churches: one episcopal, one presbyterian, and two Welsh.

This town is laid out on a very extensive scale. A small part of it only is yet completed; but little doubt is entertained that ten years will accomplish the whole. Fifteen years had not passed since there was here no other trace of habitation than a solitary log-house, built for the occasional reception of merchandise, on its way down the Mohawk. The overflowing population of New England, fixing its exertions on a new and fertile soil, has, within a few years, effected this change.

Independently of its soil, Utica has great advantages of situation; for it is nearly at the point of junction betwixt the waters of the lakes and of the Atlantic.

With Utica commences a succession of flourishing villages and settlements, which renders this tract of country the astonishment of travellers. That so large a portion of the soil should, in less than twenty years, have been cleared, brought into cultivation, and have acquired a numerous population, is, in itself, sufficiently surprising; but the surprise is considerably increased, when we consider the character of elegant opulence with which it every where smiles on the eye. Each village teems, like a hive, with activity and employment. The houses, taken in the mass, are on a large scale; [Pg 32]for (except the few primitive log-huts that still survive) there is scarcely one below the appearance of an opulent London tradesman's country box. They are, in general, of wood, painted white, with green doors and shutters; and with porches, or verandas, in front.

The travellers passed through Skaneactas, a village, pleasantly situated, at the head of the lake from which it is named. They then proceeded to Cayuga, which, besides its agreeable site, is remarkable for a bridge, nearly a mile in length, over the head of the Cayuga lake: it is built on piles, and level. Betwixt Cayuga and Geneva is the flourishing little village of Waterloo, formed since the battle so named. Geneva contains many elegant houses, beautifully placed, on the rising shore, at the head of the Geneva lake.

From Geneva to Canandaigua, a tract of hill and vale extends, for sixteen miles, and having (within that space) only two houses. Canandaigua is a town of villas, built on the rising shore of the Canandaigua lake. The lower part of the main street is occupied by stores and warehouses; but the upper part of it, to the length of nearly two miles, consists of ornamented cottages, tastefully finished with colonnades, porches, and verandas; and each within its own garden or pleasure-ground. The prospect, down this long vista, to the lake, is peculiarly elegant.

From Canandaigua the travellers turned from the main road, nine miles, south-west, to visit what is called "the burning spring." On arriving near the place, they entered a small but thick wood, of pine and maple-trees, enclosed within a narrow ravine. Down this glen, the width of which, at its entrance, may be about sixty yards, trickles a scanty streamlet. They had advanced on its course about fifty yards, when, close under the rocks of the right bank, they perceived a bright red flame, burning briskly on the water. Pieces of lighted wood were applied to different adjacent spots, and a space of several yards in extent was immediately in a blaze. Being informed by the guide that a repetition of this phenomenon [Pg 33]might be seen higher up the glen, they scrambled on, for about a hundred yards, and, directed in some degree by a strong smell of sulphur, they applied their match to several places, with similar effect. These fires continue burning unceasingly, unless they are extinguished by accident. The phænomenon was originally discovered by the casual rolling of lighted embers, from the top of the bank, whilst some persons were clearing it for cultivation; and, in the intensity and duration of the flame, it probably exceeds any thing of the kind that is known.

Rochester stands immediately on the great falls of the Genesee, about eight miles above its entrance into lake Ontario. When Mr. Hall was here, this town had been built only four years, yet it contained a hundred good houses, furnished with all the conveniences of life; several comfortable taverns, a cotton-mill, and some large corn-mills. Its site is grand. The Genesee rushes through it, over a bed of limestone, and precipitates itself down three ledges of rock, ninety-three; thirty, and seventy-six feet in height, within the distance of a mile and a half from the town. The immediate vicinity of Rochester is still an unbroken forest, consisting of oak, hickory, ash, beech, bass, elm, and walnut-trees. The wild tenants of the woods have, naturally, retired before the sound of cultivation; but there are a few wolves and bears still in the neighbourhood. One of the latter had lately seized a pig close to the town. Racoons, porcupines, squirrels black and grey, and foxes, are still numerous. The hogs have done good service in destroying the rattlesnakes, which are already becoming rare. Pigeons, quails, and blackbirds abound. At Rochester, the line of settled country, in this direction, terminates; for, from this place to Lewistown, are eighty miles of wilderness.