Title: Bibliomania; or Book-Madness

Author: Thomas Frognall Dibdin

Release date: April 8, 2009 [eBook #28540]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Suzanne Lybarger, Brian Janes, Linda Cantoni, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Suzanne Lybarger, Brian Janes, Linda Cantoni,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

Transcriber's Notes

Thomas Frognall Dibdin's Bibliomania was originally published in 1809 and was re-issued in several editions, including one published by Chatto & Windus in 1876. This e-book was prepared from a reprint of the 1876 edition, published by Thoemmes Press and Kinokuniya Company Ltd. in 1997. Where the reprint was unclear, the transcriber consulted the actual 1876 edition. All color images were scanned from the 1876 edition.

The original contains numerous footnotes, denoted by numbers in the section entitled The Bibliomania, and by symbols in the remainder of the book. All of the footnotes are consecutively numbered in this e-book; footnotes within footnotes are lettered.

Some phrases are rendered in the original in blackletter; they are rendered in bold italic in this e-book.

This e-book contains passages in ancient Greek, which may not display properly in some browsers, depending on what fonts the reader has installed. Hover the mouse over the Greek to see a pop-up transliteration, e.g. βιβλος.

Spelling and typographical errors are retained as they appear in the original. They are underlined in red, with a popup Transcriber's Note containing the correct spelling. Minor punctuation and font errors have been corrected without note. Inconsistent diacriticals and hyphenation have been retained as they appear in the original.

There are frequent inconsistencies in the spelling of certain proper names. These have been retained as they appear in the original, for example:

The original pagination used two sets of Roman numerals and two sets of Arabic numerals. To distinguish between them, in this e-book the Roman-numeral pages in the Indexes are preceded by "I." The Arabic-numeral pages in the section entitled The Bibliomania are preceded by "B." Some page numbers are skipped due to blank pages.

Page references, including those in the Indexes, do not distinguish between references appearing in the main text and those appearing in footnotes. Therefore, in this e-book, where the referenced matter does not appear in the main text on the linked page, it can be found in the nearest footnote.

Link to CONTENTS.

BIBLIOMANIA.

|

Libri quosdam ad Scientiam, quosdam ad insaniam, deduxêre. Geyler: Navis Stultifera: sign. B. iiij. rev. |

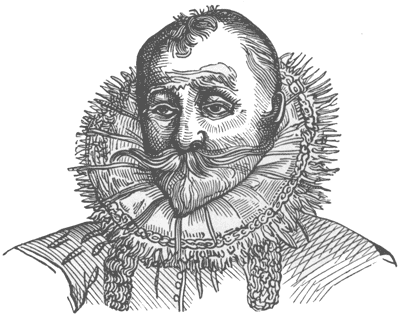

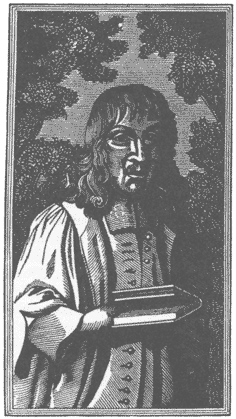

T.F. DIBDIN, D.D.

Engraved by James Thomson from the

Original Painting by T. Phillips, Esqr. R.A.

PUBLISHED BY THE PROPRIETORS (FOR THE NEW EDITION) OF THE REV. Dr. DIBDINS BIBLIOMANIA 1840.

[Enlarge]

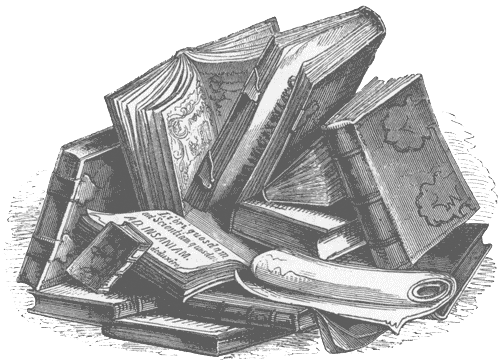

BIBLIOMANIA;

OR

Book-Madness;

A BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ROMANCE.

ILLUSTRATED WITH CUTS.

BY THOMAS FROGNALL DIBDIN, D.D.

New and improved Edition,

TO WHICH ARE ADDED

PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS, AND A SUPPLEMENT INCLUDING A KEY

TO THE ASSUMED CHARACTERS IN THE DRAMA.

London:

CHATTO & WINDUS, PICCADILLY.

MDCCCLXXVI.

[Enlarge]

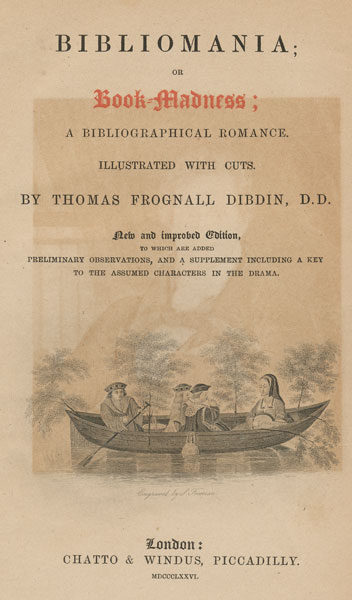

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

THE EARL OF POWIS,

PRESIDENT OF

The Roxburgh Club,

THIS

NEW EDITION

OF

BIBLIOMANIA

IS

RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY

THE AUTHOR.

HE

public may not be altogether unprepared for the re-appearance of

the Bibliomania in a more attractive garb than heretofore;—and, in

consequence, more in uniformity with the previous publications of the

Author.

HE

public may not be altogether unprepared for the re-appearance of

the Bibliomania in a more attractive garb than heretofore;—and, in

consequence, more in uniformity with the previous publications of the

Author.

More than thirty years have elapsed since the last edition; an edition, which has become so scarce that there seemed to be no reasonable objection why the possessors of the other works of the Author should beviii deprived of an opportunity of adding the present to the number: and although this re-impression may, on first glance, appear something like a violation of contract with the public, yet, when the length of time which has elapsed, and the smallness of the price of the preceding impression, be considered, there does not appear to be any very serious obstacle to the present republication; the more so, as the number of copies is limited to five hundred.

Another consideration deeply impressed itself upon the mind of the Author. The course of thirty years has necessarily brought changes and alterations amongst "men and things." The dart of death has been so busy during this period that, of the Bibliomaniacs so plentifully recorded in the previous work, scarcely three,—including the Author—have survived. This has furnished a monitory theme for the Appendix; which, to the friends both of the dead and the living, cannot be perused without sympathising emotions—

"A sigh the absent claim, the dead a tear."

The changes and alterations in "things,"—that is to say in the Bibliomania itself—have been equally capricious and unaccountable: our countrymen being, in these days, to the full as fond of novelty and variety as in those of Henry the Eighth. Dr. Board, who wrote his Introduction of Knowledge in the year 1542, and dedicated it to the Princess Mary, thus observes of our countrymen:ix

|

I am an Englishman, and naked do I stand here, Musing in my mind what raiment I shall wear; For now I will wear this, and now I will wear that, Now I will wear—I cannot tell what. |

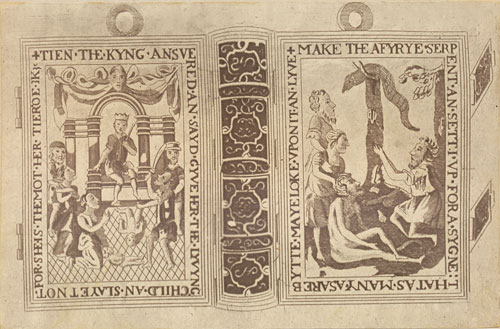

This highly curious and illustrative work was reprinted, with all its wood-cut embellishments, by Mr. Upcott. A copy of the original and most scarce edition is among the Selden books in the Bodleian library, and in the Chetham Collection at Manchester. See the Typographical Antiquities, vol. iii. p. 158-60.

But I apprehend the general apathy of Bibliomaniacs to be in a great measure attributable to the vast influx of Books, of every description, from the Continent—owing to the long continuance of peace; and yet, in the appearance of what are called English Rarities, the market seems to be almost as barren as ever. The wounds, inflicted in the Heberian contest, have gradually healed, and are subsiding into forgetfulness; excepting where, from collateral causes, there are too many striking reasons to remember their existence.

Another motive may be humbly, yet confidently, assigned for the re-appearance of this Work. It was thought, by its late proprietor,—Mr. Edward Walmsley[1]—to whose cost and liberality this edition owes itsx appearance—to be a volume, in itself, of pleasant and profitable perusal; composed perhaps in a quaint and original style, but in accordance with the characters of the Dramatis Personæ. Be this as it may, it is a work divested of all acrimonious feeling—is applicable to all classes of society, to whom harmless enthusiasm cannot be offensive—and is based upon a foundation not likely to be speedily undermined.

T.F. DIBDIN.

May 1, 1842.

[1] Mr. Edward Walmsley, who died in 1841, at an advanced age, had been long known to me. He had latterly extensive calico-printing works at Mitcham, and devoted much of his time to the production of beautiful patterns in that fabrication; his taste, in almost every thing which he undertook, leant towards the fine arts. His body was in the counting-house; but his spirit was abroad, in the studio of the painter or engraver. Had his natural talents, which were strong and elastic, been cultivated in early life, he would, in all probability, have attained a considerable reputation. How he loved to embellish—almost to satiety—a favourite work, may be seen by consulting a subsequent page towards the end of this volume. He planned and published the Physiognomical Portraits, a performance not divested of interest—but failing in general success, from the prints being, in many instances, a repetition of their precursors. The thought, however, was a good one; and many of the heads are powerfully executed. He took also a lively interest in Mr. Major's splendid edition of Walpole's Anecdotes of Painting in England, a work, which can never want a reader while taste has an abiding-place in one British bosom.

Mr. Walmsley possessed a brave and generous spirit; and I scarcely knew a man more disposed to bury the remembrance of men's errors in that of their attainments and good qualities.

[Enlarge]

THE BIBLIOMANIA;

OR

Book-Madness;

CONTAINING SOME ACCOUNT OF THE

HISTORY, SYMPTOMS, AND CURE OF

THIS FATAL DISEASE.

IN AN EPISTLE ADDRESSED TO

RICHARD HEBER, Esq.

BY THE

REV. THOMAS FROGNALL DIBDIN, F.S.A.

|

Styll am I besy bokes assemblynge, For to have plenty it is a pleasaunt thynge In my conceyt, and to have them ay in honde: But what they mene I do nat understonde. Pynson's Ship of Fools. Edit. 1509. |

LONDON:

REPRINTED FROM THE FIRST EDITION, PUBLISHED IN

1809.

In laying before the public the following brief and superficial account of a disease, which, till it arrested the attention of Dr. Ferriar, had entirely escaped the sagacity of all ancient and modern physicians, it has been my object to touch chiefly on its leading characteristics; and to present the reader (in the language of my old friend Francis Quarles) with an "honest pennyworth" of information, which may, in the end, either suppress or soften the ravages of so destructive a malady. I might easily have swelled the size of this treatise by the introduction of much additional, and not incurious, matter; but I thought it most prudent to wait the issue of the present "recipe," at once simple in its composition and gentle in its effects.

Some apology is due to the amiable and accomplished character to whom my epistle is addressed, as well as to the public, for the apparently conxivfused and indigested manner in which the notes are attached to the first part of this treatise; but, unless I had thrown them to the end (a plan which modern custom does not seem to warrant), it will be obvious that a different arrangement could not have been adopted; and equally so that the perusal, first of the text, and afterwards of the notes, will be the better mode of passing judgment upon both.

T.F.D.

Kensington, June 5, 1809.

SHORT time after the publication of the first edition of this work,

a very worthy and shrewd Bibliomaniac, accidentally meeting me,

exclaimed that "the book would do, but that there was not gall

enough in it." As he was himself a Book-Auction-loving Bibliomaniac,

I was resolved, in a future edition, to gratify him and similar

Collectors by writing Part III. of the present impression; the motto

of which may probably meet their approbation.

SHORT time after the publication of the first edition of this work,

a very worthy and shrewd Bibliomaniac, accidentally meeting me,

exclaimed that "the book would do, but that there was not gall

enough in it." As he was himself a Book-Auction-loving Bibliomaniac,

I was resolved, in a future edition, to gratify him and similar

Collectors by writing Part III. of the present impression; the motto

of which may probably meet their approbation.

It will be evident, on a slight inspection of the present edition, that it is so much altered and enlarged as to assume the character of a new work. This has not been done without mature reflection; and a long-cherished hope of making it permanently useful to a large class of General Readers, as well as to Book-Collectors and Bibliographers.xvi

It appeared to me that notices of such truly valuable, and oftentimes curious and rare, books, as the ensuing pages describe; but more especially a Personal History of Literature, in the characters of Collectors of Books; had long been a desideratum even with classical students: and in adopting the present form of publication, my chief object was to relieve the dryness of a didactic style by the introduction of Dramatis Personæ.

The worthy Gentlemen, by whom the Drama is conducted, may be called, by some, merely wooden machines or pegs to hang notes upon; but I shall not be disposed to quarrel with any criticism which may be passed upon their acting, so long as the greater part of the information, to which their dialogue gives rise, may be thought serviceable to the real interests of Literature and Bibliography.

If I had chosen to assume a more imposing air with the public, by spinning out the contents of this closely-printed book into two or more volumes—which might have been done without violating the customary mode of publication—the expenses of the purchaser, and the profits of the author, would have equally increased: but I was resolved to bring forward as much matter as I could impart, in a convenient and not inelegantly executed form; and, if my own emoluments are less, I honestly hope the reader's advantage is greater.

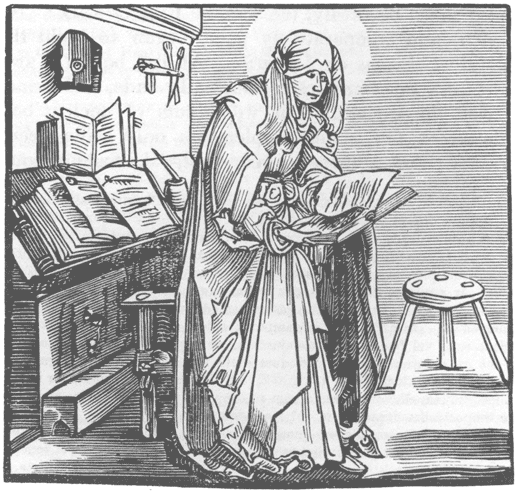

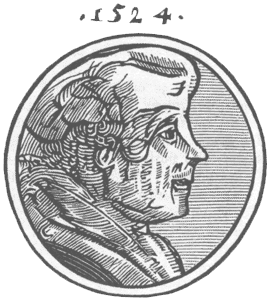

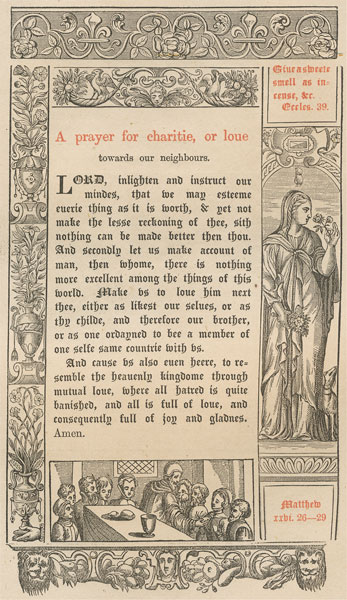

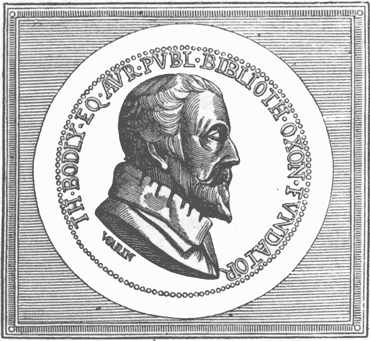

The Engraved Ornaments of Portraits, Vignettes, and Borders, were introduced, as well to gratify the eyes of tasteful Bibliomaniacs, as to impress, uponxvii the minds of readers in general, a more vivid recollection of some of those truly illustrious characters by whom the History of British Literature has been preserved.

It remains only to add that the present work was undertaken to relieve, in a great measure, the anguish of mind arising from a severe domestic affliction; and if the voice of those whom we tenderly loved, whether parent or child, could be heard from the grave, I trust it would convey the sound of approbation for thus having filled a part of the measure of that time which, every hour, brings us nearer to those from whom we are separated.

And now, Benevolent Reader, in promising thee as much amusement and instruction as ever were offered in a single volume, of a nature like to the present, I bid thee farewell in the language of Vogt,[2] who thus praises the subject of which we are about to treat:—"Quis non amabilem eam laudabit insaniam, quæ universæ rei litterariæ non obfuit, sed profuit; historiæ litterariæ doctrinam insigniter locupletavit; ingentemque exercitum voluminum, quibus alias aut in remotiora Bibliothecarum publicarum scrinia commigrandum erat, aut plane pereundum, a carceribus et interitu vindicavit, exoptatissimæque luci et eruditorum usui multiplici felicitur restituit?"

T.F.D.

Kensington, March 25, 1811.

[2] Catalogus Librorum Rariorum, præf. ix. edit. 1793.

| Part I. | The Evening Walk. On the right uses of Literature | p. 3-20. |

| II. | The Cabinet. Outline of Foreign and Domestic Bibliography | p. 23-92. |

| III. | The Auction-Room. Character of Orlando. Of ancient Prices of Books, and of Book-Binding. Book-Auction Bibliomaniacs | p. 103-139. |

| IV. | The Library. Dr. Henry's History of Great Britain. A Game at Chess. Of Monachism and Chivalry. Dinner at Lorenzo's. Some Account of Book Collectors in England | p. 143-207. |

| V. | The Drawing Room. History of the Bibliomania, or Account of Book Collectors, concluded | p. 211-463. |

| VI. | The Alcove. Symptoms of the Disease called the Bibliomania. Probable Means of its Cure | p. 467-565. |

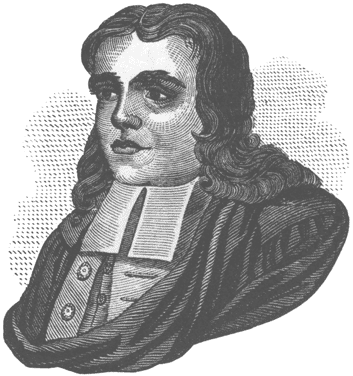

LUTHER. |

MELANCTHON. |

PUBLISHED BY THE PROPRIETOR (FOR THE NEW EDITION) OF THE REV. Dr. DIBDINS BIBLIOMANIA, 1840.

MY DEAR SIR,

When the poetical Epistle of Dr. Ferriar, under the popular title of "The Bibliomania," was announced for publication, I honestly confess that, in common with many of my book-loving acquaintance, a strong sensation of fear and of hope possessed me: of fear, that I might have been accused, however indirectly, of having contributed towards the increase of this Mania; and of hope, that the true object of book-collecting, and literary pursuits, might have been fully and fairly developed. The perusal of this elegant epistle dissipated alike my fears and my hopes; for, instead of caustic verses, and satirical notes,[3] I found a smooth,B. 2 melodious, and persuasive panegyric; unmixed, however, with any rules for the choice of books, or the regulation of study.

[3] There are, nevertheless, some satirical allusions which one could have wished had been suppressed. For instance:

|

He turns where Pybus rears his atlas-head, Or Madoc's mass conceals its veins of lead; |

What has Mr. Pybus's gorgeous book in praise of the late Russian Emperor Paul I. (which some have called the chef-d'œuvre of Bensley's press[A]) to do with Mr. Southey's fine Poem of Madoc?—in which, if there are "veins of lead," there are not a few "of silver and gold." Of the extraordinary talents of Mr. Southey, the indefatigable student in ancient lore, and especially in all that regards Spanish Literature and Old English Romances, this is not the place to make mention. His "Remains of Henry Kirk White," the sweetest specimen of modern biography, has sunk into every heart, and received an eulogy from every tongue. Yet is his own life

"The more endearing song."

Dr. Ferriar's next satirical verses are levelled at Mr. Thomas Hope.

|

"The lettered fop now takes a larger scope, With classic furniture, design'd by Hope. (Hope, whom upholsterers eye with mute despair, The doughty pedant of an elbow chair.") |

It has appeared to me that Mr. Hope's magnificent volume on "Household Furniture" has been generally misunderstood, and, in a few instances, criticised upon false principles.—The first question is, does the subject admit of illustration? and if so, has Mr. Hope illustrated it properly? I believe there is no canon of criticism which forbids the treating of such a subject; and, while we are amused with archæological discussions on Roman tiles and tesselated pavements, there seems to be no absurdity in making the decorations of our sitting rooms, including something more than the floor we walk upon, a subject at least of temperate and classical disquisition. Suppose we had found such a treatise in the volumes of Gronovius and Montfaucon? (and are there not a few, apparently, as unimportant and confined in these rich volumes of the Treasures of Antiquity?) or suppose something similar to Mr. Hope's work had been found among the ruins of Herculaneum? Or, lastly, let us suppose the author had printed it only as a private book, to be circulated as a present! In each of these instances, should we have heard the harsh censures which have been thrown out against it? On the contrary, is it not very probable that a wish might have been expressed that "so valuable a work ought to be made public."

Upon what principle, a priori, are we to ridicule and condemn it? I know of none. We admit Vitruvius, Inigo Jones, Gibbs, and Chambers, into our libraries: and why not Mr. Hope's book? Is decoration to be confined only to the exterior? and, if so, are works, which treat of these only, to be read and applauded? Is the delicate bas-relief, and beautifully carved column, to be thrust from the cabinet and drawing room, to perish on the outside of a smoke-dried portico? Or, is not that the most deserving of commendation which produces the most numerous and pleasing associations of ideas? I recollect, when in company with the excellent Dr. Jenner,

|

——[clarum et venerabile nomen Gentibus, et multum nostræ quod proderat urbi] |

and a half dozen more friends, we visited the splendid apartments in Duchess Street, Portland Place, we were not only struck with the appropriate arrangement of every thing, but, on our leaving them, and coming out into the dull foggy atmosphere of London, we acknowledged that the effect produced upon our minds was something like that which might have arisen had we been regaling ourselves on the silken couches, and within the illuminated chambers, of some of the enchanted palaces described in the Arabian Nights' Entertainments. I suspect that those who have criticised Mr. Hope's work with asperity have never seen his house.

These sentiments are not the result of partiality or prejudice, for I am wholly unacquainted with Mr. Hope. They are delivered with zeal, but with deference. It is quite consolatory to find a gentleman of large fortune, of respectable ancestry, and of classical attainments, devoting a great portion of that leisure time which hangs like a leaden weight upon the generality of fashionable people, to the service of the Fine Arts, and in the patronage of merit and ingenuity. How much the world will again be indebted to Mr. Hope's taste and liberality may be anticipated from the "Costume of the Ancients," a work which has recently been published under his particular superintendence.

[A] This book is beautifully executed, undoubtedly, but being little more than a thin folio pamphlet devoid of typographical embellishment—it has been thought by some hardly fair to say this of a press which brought out so many works characterized by magnitude and various elegance. B.B.

To say that I was not gratified by the perusal of it would be a confession contrary to the truth; but to say how ardently I anticipated an amplification of the subject, how eagerly I looked forward to a number ofB. 3 curious, apposite, and amusing anecdotes, and found them not therein, is an avowal of which I need not fear the rashness, when the known talents of the detector of Stern's plagiarisms[4] are considered. I will not, however, disguise to you that I read it with uniform delight, and that I rose from the perusal with a keener appetite for

|

"The small, rare volume, black with tarnished gold." Dr. Ferriar's Ep. v. 138. |

[4] In the fourth volume of the Transactions of the Manchester Literary Society, part iv., p. 45-87, will be found a most ingenious and amusing Essay, entitled "Comments on Sterne," which excited a good deal of interest at the time of its publication. This discovery may be considered, in some measure, as the result of the Bibliomania. In my edition of Sir Thomas More's Utopia, a suggestion is thrown out that even Burton may have been an imitator of Boisatuau: see vol. II. 143.

Whoever undertakes to write down the follies which grow out of an excessive attachment to any particularB. 4 pursuit, be that pursuit horses,[5] hawks, dogs, guns, snuff boxes,[6] old china, coins, or rusty armour, mayB. 5 be thought to have little consulted the best means of ensuring success for his labours, when he adopts theB. 6 dull vehicle of Prose for the commnication of his ideas not considering that from Poetry ten thousand bright scintillations are struck off, which please and convince while they attract and astonish. Thus when Pope talks of allotting for

|

"Pembroke[7] Statues, dirty Gods and Coins; Rare monkish manuscripts for Hearne[8] alone; And books to Mead[9] and butterflies to Sloane,"[10] |

when he says that

These Aldus[11] printed, those Du Sūeil has bound[12]

moreover that

|

For Locke or Milton[13] 'tis in vain to look; These shelves admit not any modern book; |

he not only seems to illustrate the propriety of theB. 7 foregoing remark, by shewing the immense superiority of verse to prose, in ridiculing reigning absurdities, but he seems to have had a pretty strong foresight of theB. 8 Bibliomania which rages at the present day. However, as the ancients tell us that a Poet cannot be a manufactured creature, and as I have not the smallestB. 9 pretensions to the "rhyming art," [although in former times[14] I did venture to dabble with it] I must of necessity have recourse to Prose; and, at the same time, to your candour and forbearance in perusing the pages which ensue.

[5] It may be taken for granted that the first book in this country which excited a passion for the Sports of the field was Dame Juliana Berners, or Barnes's, work, on Hunting and Hawking, printed at St. Alban's, in the year 1486; of which Lord Spencer's copy is, I believe, the only perfect one known. It was formerly the Poet Mason's, and is mentioned in the quarto edition of Hoccleve's Poems, p. 19, 1786. See too Bibl. Mason. Pt. iv. No. 153. Whether the forementioned worthy lady was really the author of the work has been questioned. Her book was reprinted by Wynkyn de Worde in 1497, with an additional Treatise on Fishing. The following specimen, from this latter edition, ascertains the general usage of the French language with our huntsmen in the 15th century.

Beasts of Venery.

|

Where so ever ye fare by frith or by fell, My dear child, take heed how Trystram do you tell. How many manner beasts of Venery there were: Listen to your dame and she shall you lere. Four manner beasts of Venery there are. The first of them is the Hart; the second is the Hare; The Horse is one of them; the Wolf; and not one mo. |

Beasts of the Chace.

|

And where that ye come in plain or in place I shall tell you which be beasts of enchace. One of them is the Buck; another is the Doe; The Fox; and the Marteron, and the wild Roe; And ye shall see, my dear child, other beastes all: Where so ye them find Rascal ye shall them call. |

Of the hunting of the Hare.

|

How to speke of the haare how all shall be wrought: When she shall with houndes be founden and sought. The fyrst worde to the hoūdis that the hunter shall out pit Is at the kenell doore whan he openeth it. That all maye hym here: he shall say "Arere!" For his houndes would come to hastily. That is the firste worde my sone of Venery. And when he hath couplyed his houndes echoon And is forth wyth theym to the felde goon, And whan he hath of caste his couples at wyll Thenne he shall speke and saye his houndes tyll "Hors de couple avant, sa avant!" twyse soo: And then "So ho, so ho!" thryes, and no moo. |

And then say "Sacy avaunt, so how," I thou praye, etc. The following are a few more specimens—"Ha cy touz cy est yll—Venez ares sa how sa—La douce la eit a venuz—Ho ho ore, swet a lay, douce a luy—So how, so how, venez acoupler!!!"

Whoever wishes to see these subjects brought down to later times, and handled with considerable dexterity, may consult the last numbers of the Censura Literaria, with the signature J.H. affixed to them. Those who are anxious to procure the rare books mentioned in these bibliographical treatises, may be pretty safely taxed with being infected by the Bibliomania. What apology my friend Mr. Haslewood, the author of them, has to offer in extenuation of the mischief committed, it is his business, and not mine, to consider; and what the public will say to his curious forthcoming reprint of the ancient edition of Wynkyn De Worde on Hunting, Hawking, and Fishing, 1497 (with wood cuts), I will not pretend to divine!

In regard to Hawking, I believe the enterprising Colonel Thornton in the only gentleman of the present day who keeps up this custom of "good old times."

The Sultans of the East seem not to have been insensible to the charms of Falconry, if we are to judge from the evidence of Tippoo Saib having a work of this kind in his library; which is thus described from the Catalogue of it just published in a fine quarto volume, of which only 250 copies are printed.

"Shābbār Nāmeh, 4to. a Treatise on Falcony; containing Instructions for selecting the best species of Hawks, and the method of teaching them; describing their different qualities; also the disorders they are subject to, and method of cure. Author unknown."—Oriental Library of Tippoo Saib, 1809, p. 96.

[6] Of Snuff boxes every one knows what a collection the great Frederick, King of Prussia, had—many of them studded with precious stones, and decorated with enamelled portraits. Dr. C. of G——, has been represented to be the most successful rival of Frederick, in this "line of collection," as it is called; some of his boxes are of uncommon curiosity. It may gratify a Bibliographer to find that there are other Manias besides that of the book; and that even physicians are not exempt from these diseases.

Of Old China, Coins, and Rusty Armour, the names of hundreds present themselves in these departments; but to the more commonly-known ones of Rawle and Grose, let me add that of the late Mr. John White, of Newgate-Street; a catalogue of whose curiosities [including some very uncommon books] was published in the year 1788, in three parts, 8vo. Dr. Burney tells us that Mr. White "was in possession of a valuable collection of ancient rarities, as well as natural productions, of the most curious and extraordinary kind; no one of which however was more remarkable than the obliging manner in which he allowed them to be viewed and examined by his friends."—History of Music, vol. II. 539, note.

[7] The reader will find an animated eulogy on this great nobleman in Walpole's Anecdotes of Painters, vol. iv. 227: part of which was transcribed by Joseph Warton for his Variorum edition of Pope's Works, and thence copied into the recent edition of the same by the Rev. W.L. Bowles. But Pembroke deserved a more particular notice. Exclusively of his fine statues, and architectural decorations, the Earl contrived to procure a number of curious and rare books; and the testimonies of Maittaire [who speaks indeed of him with a sort of rapture!] and Palmer shew that the productions of Jenson and Caxton were no strangers to his library. Annales Typographici, vol. I. 13. edit. 1719. History of Printing, p. v. "There is nothing that so surely proves the pre-eminence of virtue more than the universal admiration of mankind, and the respect paid it even by persons in opposite interests; and more than this, it is a sparkling gem which even time does not destroy: it is hung up in the Temple of Fame, and respected for ever." Continuation of Granger, vol. I. 37, &c. "He raised, continues Mr. Noble, a collection of Antiques that were unrivalled by any subject. His learning made him a fit companion for the literati. Wilton will ever be a monument of his extensive knowledge; and the princely presents it contains, of the high estimation in which he was held by foreign potentates, as well as by the many monarchs he saw and served at home. He lived rather as a primitive christian; in his behaviour, meek: in his dress, plain: rather retired, conversing but little." Burnet, in the History of his own Times, has spoken of the Earl with spirit and propriety.

[8] In the recent Variorum Edition of Pope's Works, all that is annexed to Hearne's name, as above introduced by the Poet, is, "well known as an Antiquarian."

Alas, Poor Hearne!

thy merits, which are now fully appreciated, deserve an ampler notice! In spite of Gibbon's unmerciful critique [Posthumous Works, vol. II. 711.], the productions of this modest, erudite, and indefatigable antiquary are rising in price proportionably to their worth. If he had only edited the Collectanea and Itinerary of his favourite Leland, he would have stood on high ground in the department of literature and antiquities; but his other and numerous works place him on a much loftier eminence. Of these, the present is not the place to make mention; suffice it to say that, for copies of his works, on Large Paper, which the author used to advertise as selling for 7s. or 10s., or about which placards, to the same effect, used to be stuck on the walls of the colleges,—these very copies are now sometimes sold for more than the like number of guineas! It is amusing to observe that the lapse of a few years only has caused such a rise in the article of Hearne; and that the Peter Langtoft on large paper, which at Rowe Mores's sale [Bibl. Mores. No. 2191.] was purchased for £1. 2s. produced at a late sale, [A.D. 1808] £37! A complete list of Hearne's Pieces will be found at the end of his Life, printed with Leland's, &c., at the Clarendon Press, in 1772, 8vo. Of these the "Acta Apostolorum, Gr. Lat;" and "Aluredi Beverlacensis Annales," are, I believe, the scarcest. It is wonderful to think how this amiable and excellent man persevered "through evil report and good report," in illustrating the antiquities of his country. To the very last he appears to have been molested; and among his persecutors, the learned editor of Josephus and Dionysius Halicarnasseus, Dr. Hudson, must be ranked, to the disgrace of himself and the party which he espoused. "Hearne was buried in the church yard of St. Peter's (at Oxford) in the East, where is erected over his remains, a tomb, with an inscription written by himself,

|

Amicitiæ Ergo. Here lyeth the Body of Thomas Hearne, M.A. Who studied and preserved Antiquities. He dyed June 10, 1735. Aged 57 years. Deut. xxxii: 7. Remember the days of old; consider the years of many generations; ask thy Father and he will shew thee; thy elders and they will tell thee. Job. viii. 8, 9, 10. Enquire I pray thee." Life of Hearne, p. 34. |

[9] Of Dr. Mead and his Library a particular account is given in the following pages.

[10] For this distinguished character consult Nichols's Anecdotes of Bowyer, 550, note*; which, however, relates entirely to his ordinary habits and modes of life. His magnificent collection of Natural Curiosities and MSS. is now in the British Museum.

[11] The annals of the Aldine Press have had ample justice done to them in the beautiful and accurate work published by Renouard, under the title of "Annales de L'Imprimerie des Alde," in two vols., 8vo. 1804. One is rather surprised at not finding any reference to this masterly piece of bibliography in the last edition of Mr. Roscoe's Leo X., where there is a pleasing account of the establishment of the Aldine Press.

[12] I do not recollect having seen any book bound by this binder. Of Padaloup, De Rome, and Baumgarten, where is the fine collection that does not boast of a few specimens? We will speak "anon" of the Roger Paynes, Kalthoebers, Herrings, Stagemiers, and in Macklays of the day!

[13] This is not the reproach of the age we live in; for reprints of Bacon, Locke, and Milton have been published with complete success. It would be ridiculous indeed for a man of sense, and especially a University man, to give £5 or £6 for "Gosson's School of Abuse, against Pipers and Players," or £3. 3s. for a clean copy of "Recreation for Ingenious Head Pieces, or a Pleasant Grove for their Wits to walk in," and grudge the like sum for a dozen handsome octavo volumes of the finest writers of his country.

[14] About twelve years ago I was rash enough to publish a small volume of Poems, with my name affixed. They were the productions of my juvenile years; and I need hardly say, at this period, how ashamed I am of their author-ship. The monthly and Analytical Reviews did me the kindness of just tolerating them, and of warning me not to commit any future trespass upon the premises of Parnassus. I struck off 500 copies, and was glad to get rid of half of them as waste paper; the remaining half has been partly destroyed by my own hands, and has partly mouldered away in oblivion amidst the dust of Booksellers' shelves. My only consolation is that the volume is exceedingly rare!

If ever there was a country upon the face of the globe—from the days of Nimrod the beast, to Bagford[15] the book-hunter—distinguished for the variety, the justness, and magnanimity of its views; if ever there was a nation which really and unceasingly "felt for another's woe" [I call to witness our Infirmaries, Hospitals, Asylums, and other public and privateB. 10 Institutions of a charitable nature, that, like so many belts of adamant, unite and strengthen us in the great cause of Humanity]; if ever there was a country and a set of human beings pre-eminently distinguished for all the social virtues which soften and animate the soul of man, surely Old England and Englishmen are they! The common cant, it may be urged, of all writers in favour of the country where they chance to live! And what, you will say, has this to do with Book Collectors and Books?—Much, every way: aB. 11 nation thus glorious is, at this present eventful moment, afflicted not only with the Dog[16], but the Book, disease—

|

Fire in each eye, and paper in each hand They rave, recite,—— |

[15] "John Bagford, by profession a bookseller, frequently travelled into Holland and other parts, in search of scarce books and valuable prints, and brought a vast number into this kingdom, the greatest part of which were purchased by the Earl of Oxford. He had been in his younger days a shoemaker; and, for the many curiosities wherewith he enriched the famous library of Dr. John Moore, Bishop of Ely, his Lordship got him admitted into the Charter House. He died in 1706, aged 65: after his death Lord Oxford purchased all his collections and papers, for his library: these are now in the Harleian collection in the British Museum. In 1707 were published, in the Philosophical Transactions, his Proposals for a General History of Printing."—Bowyer and Nichols's Origin of Printing, p. 164, 189, note.

It has been my fortune (whether good or bad remains to be proved) not only to transcribe the slender memorial of Printing in the Philosophical Transactions, drawn up by Wanley for Bagford, but to wade through forty-two folio volumes, in which Bagford's materials for a History of Printing are incorporated, in the British Museum: and from these, I think I have furnished myself with a pretty fair idea of the said Bagford. He was the most hungry and rapacious of all book and print collectors; and, in his ravages, spared neither the most delicate nor costly specimens. His eyes and his mouth seem to have been always open to express his astonishment at, sometimes, the most common and contemptible productions; and his paper in the Philosophical Transactions betrays such simplicity and ignorance that one is astonished how my Lord Oxford and the learned Bishop of Ely could have employed so credulous a bibliographical forager. A modern collector and lover of perfect copies will witness, with shuddering, among Bagford's immense collection of Title Pages, in the Museum, the frontispieces of the Complutensian Polyglot, and Chauncy's History of Hertfordshire, torn out to illustrate a History of Printing. His enthusiasm, however, carried him through a great deal of laborious toil; and he supplied, in some measure, by this qualification, the want of other attainments. His whole mind was devoted to book-hunting; and his integrity and diligence probably made his employers overlook his many failings. His hand-writing is scarcely legible, and his orthography is still more wretched; but if he was ignorant, he was humble, zealous, and grateful; and he has certainly done something towards the accomplishment of that desirable object, an accurate General History of Printing. In my edition of Ames's Typographical Antiquities, I shall give an analysis of Bagford's papers, with a specimen or two of his composition.

[16] For an eloquent account of this disorder consult the letters of Dr. Mosely inserted in the Morning Herald of last year. I have always been surprised, and a little vexed, that these animated pieces of composition should be relished and praised by every one—but the Faculty!

Let us enquire, therefore, into the origin and tendency of the Bibliomania.

In this enquiry I purpose considering the subject under three points of view: I. The History of the Disease; or an account of the eminent men who have fallen victims to it: II. The Nature, or Symptoms of the Disease: and III. The probable means of its Cure. We are to consider, then,

1. The History of the Disease. In treating of the history of this disease, it will be found to have been attended with this remarkable circumstance; namely, that it has almost uniformly confined its attacks to the male sex, and, among these, to people in the higher and middling classes of society, while the artificer, labourer, and peasant have escaped wholly uninjured. It has raged chiefly in palaces, castles, halls, and gay mansions; and those things which in general are supposed not to be inimical to health, such as cleanliness, spaciousness, and splendour, are only so many inducements towards the introduction and propagation of the Bibliomania! What renders it particularly formidable is that it rages in all seasons of the year, and at all periods of human existence. The emotions of friendship or of love are weakened or subdued as old age advances; but the influence of this passion, orB. 12 rather disease, admits of no mitigation: "it grows with our growth, and strengthens with our strength;" and is oft-times

——The ruling passion strong in death.[17]

[17] The writings of the Roman philologers seem to bear evidence of this fact. Seneca, when an old man, says that, "if you are fond of books, you will escape the ennui of life; you will neither sigh for evening, disgusted with the occupations of the day—nor will you live dissatisfied with yourself, or unprofitable to others." De Tranquilitate, ch. 3. Cicero has positively told us that "study is the food of youth, and the amusement of old age." Orat. pro Archia. The younger Pliny was a downright Bibliomaniac. "I am quite transported and comforted," says he, "in the midst of my books: they give a zest to the happiest, and assuage the anguish of the bitterest, moments of existence! Therefore, whether distracted by the cares or the losses of my family, or my friends, I fly to my library as the only refuge in distress: here I learn to bear adversity with fortitude." Epist. lib. viii. cap. 19. But consult Cicero De Senectute. All these treatises afford abundant proof of the hopelessness of cure in cases of the Bibliomania.

We will now, my dear Sir, begin "making out the catalogue" of victims to the Bibliomania! The first eminent character who appears to have been infected with this disease was Richard De Bury, one of the tutors of Edward III., and afterwards Bishop of Durham; a man who has been uniformly praised for the variety of his erudition, and the intenseness of his ardour in book-collecting.[18] I discover no otherB. 13 notorious example of the fatality of the Bibliomania until the time of Henry VII.; when the monarch himself may be considered as having added to the number. Although our venerable typographer, Caxton, lauds and magnifies, with equal sincerity, the whole line of British Kings, from Edward IV. to Henry VII. [under whose patronage he would seem, in some measure, to have carried on his printing business], yet, of all these monarchs, the latter alone was so unfortunate as to fall a victim to this disease. His library must haveB. 14 been a magnificent one, if we may judge from the splendid specimens of it which now remain.[19] It would appear, too, that, about this time, the Bibliomania was increased by the introduction of foreign printed books; and it is not very improbable that a portion of Henry's immense wealth was devoted towards the purchase of vellum copies, which were now beginning to be published by the great typographical triumvirate, Verard, Eustace, and Pigouchet.

[18] It may be expected that I should notice a few book-lovers, and probably Bibliomaniacs, previously to the time of Richard De Bury; but so little is known with accuracy of Johannes Scotus Erigena, and his patron Charles the Bald, King of France, or of the book tête-a-têtes they used to have together—so little, also, of Nennius, Bede, and Alfred [although the monasteries at this period, from the evidence of Sir William Dugdale, in the first volume of the Monasticon were "opulently endowed,"—inter alia, I should hope, with magnificent MSS. on vellum, bound in velvet, and embossed with gold and silver], or the illustrious writers in the Norman period, and the fine books which were in the abbey of Croyland—so little is known of book-collectors, previously to the 14th century, that I thought it the most prudent and safe way to begin with the above excellent prelate.

Richard De Bury was the friend and correspondent of Petrarch; and is said by Mons. de Sade, in his Memoires pour la vie de Petrarque, "to have done in England what Petrarch did all his life in France, Italy, and Germany, towards the discovery of MSS. of the best ancient writers, and making copies of them under his own superintendence." His passion for book-collecting was unbounded ["vir ardentis ingenii," says Petrarch of him]; and in order to excite the same ardour in his countrymen, or rather to propagate the disease of the Bibliomania with all his might, he composed a bibliographical work under the title of Philobiblion; concerning the first edition of which, printed at Spires in 1483, Clement (tom. v. 142) has a long gossiping account; and Morhof tells us that it is "rarissima et in paucorum manibus versatur." It was reprinted in Paris in 1500, 4to., by the elder Ascensius, and frequently in the subsequent century, but the best editions of it are those by Goldastus in 1674, 8vo., and Hummius in 1703. Morhof observes that, "however De Bury's work savours of the rudeness of the age, it is rather elegantly written, and many things are well said in it relating to Bibliothecism." Polyhist. Literar. vol. i. 187, edit. 1747.

For further particulars concerning De Bury, read Bale, Wharton, Cave, and Godwin's Episcopal Biography. He left behind him a fine library of MSS. which he bequeathed to Durham, now Trinity, College, Oxford.

It may be worth the antiquary's notice, that, in consequence (I suppose) of this amiable prelate's exertions, "in every convent was a noble library and a great: and every friar, that had state in school, such as they be now, hath an hugh Library." See the curious Sermon of the Archbishop of Armagh, Nov. 8, 1387, in Trevisa's works among the Harleian MSS. No. 1900. Whether these Friars, thus affected with the frensy of book-collecting, ever visited the "old chapelle at the Est End of the church of S. Saink [Berkshire], whither of late time resorted in pilgrimage many folkes for the disease of madness," [see Leland's Itinerary, vol. ii. 29, edit. 1770] I have not been able, after the most diligent investigation, to ascertain.

[19] The British Museum contains a great number of books which bear the royal stamp of Henry VII.'s arms. Some of these printed by Verard, upon vellum, are magnificent memorials of a library, the dispersion of which is for ever to be regretted. As Henry VIII. knew nothing of, and cared less for, fine books, it is not very improbable that some of the choicest volumes belonging to the late king were presented to Cardinal Wolsey.

During the reign of Henry VIII., I should suppose that the Earl of Surrey[20] and Sir Thomas Wyatt were a little attached to book-collecting; and that Dean Colet[21] and his friend Sir Thomas More andB. 15 Erasmus were downright Bibliomaniacs. There can be little doubt but that neither the great Leland[22] norB. 16 his Biographer Bale,[23] were able to escape the contagion; and that, in the ensuing period, Rogar Ascham became notorious for the Book-disease. He purchasedB. 17 probably, during his travels abroad[24] many a fine copy of the Greek and Latin Classics, from which he readB. 18 to his illustrious pupils, Lady Jane Grey, and Queen Elizabeth: but whether he made use of an EditioB. 19 Princeps, or a Large paper copy, I have hitherto not been lucky enough to discover. This learned chaB. 20racter died in the vigour of life, and in the bloom of reputation: and, as I suspect, in consequence of the Bibliomania—for he was always collecting books, and always studying them. His "Schoolmaster" is a work which can only perish with our language.

[20] The Earl of Surrey and Sir Thomas Wyatt were among the first who taught their countrymen to be charmed with the elegance and copiousness of their own language. How effectually they accomplished this laudable object, will be seen from the forthcoming beautiful and complete edition of their works by the Rev. Dr. Nott.[B]

[B] It fell to the lot of the printer of this volume, during his apprenticeship to his father, to correct the press of nearly the whole of Dr. Nott's labours, which were completed, after several years of toil, when in the extensive conflagration of the printing-office at Bolt Court, Fleet-street, in 1819, all but two copies were totally destroyed!

[21] Colet, More, and Erasmus [considering the latter when he was in England] were here undoubtedly the great literary triumvirate of the early part of the 16th century. The lives of More and Erasmus are generally read and known; but of Dean Colet it may not be so generally known that his ardour for books and for classical literature was keen, and insatiable; that, in the foundation of St. Paul's School, he has left behind a name which entitles him to rank in the foremost of those who have fallen victims to the Bibliomania. How anxiously does he seem to have watched the progress, and pushed the sale, of his friend Erasmus's first edition of the Greek Testament! "Quod scribis de Novo Testamento intelligo. Et libri novæ editionis tuæ hic avide emuntur et passim leguntur!" The entire epistle (which may be seen in Dr. Knight's dry Life of Colet, p. 315) is devoted to an account of Erasmus's publications. "I am really astonished, my dear Erasmus [does he exclaim], at the fruitfulness of your talents; that, without any fixed residence, and with a precarious and limited income, you contrive to publish so many and such excellent works." Adverting to the distracted state of Germany at this period, and to the wish of his friend to live secluded and unmolested, he observes—"As to the tranquil retirement which you sigh for, be assured that you have my sincere wishes for its rendering you as happy and composed as you can wish it. Your age and erudition entitle you to such a retreat. I fondly hope, indeed, that you will choose this country for it, and come and live amongst us, whose disposition you know, and whose friendship you have proved."

There is hardly a more curious picture of the custom of the times, relating to the education of boys, than the Dean's own Statutes for the regulation of St. Paul's School, which he had founded. These shew, too, the popular books then read by the learned. "The children shall come unto the School in the morning at seven of the clock, both winter and summer, and tarry there until eleven; and return against one of the clock, and depart at five, &c. In the school, no time in the year, they shall use tallow candle in no wise, but only wax candle, at the costs of their friends. Also I will they bring no meat nor drink, nor bottle, nor use in the school no breakfasts, nor drinkings, in the time of learning, in no wise, &c. I will they use no cockfightings, nor riding about of victory, nor disputing at Saint Bartholomew, which is but foolish babbling and loss of time." The master is then restricted, under the penalty of 40 shillings, from granting the boys a holiday, or "remedy," [play-day,] as it is here called "except the King, an Archbishop, or a Bishop, present in his own person in the school, desire it." The studies for the lads were, "Erasmus's Copia & Institutum Christiani Hominis (composed at the Dean's request) Lactantius, Prudentius, Juvencus, Proba and Sedulius, and Baptista Mantuanus, and such other as shall be thought convenient and most to purpose unto the true Latin speech: all barbary, all corruption, all Latin adulterate, which ignorant blind fools brought into this world, and with the same hath distained and poisoned the old Latin speech, and the veray Roman tongue, which in the time of Tully and Sallust and Virgil and Terence was used—I say that filthiness, and all such abusion, which the later blind world brought in, which more rather may be called Bloterature that [] Literature, I utterly banish and exclude out of this school." Life of Knight's Colet, 362-4.

What was to be expected, but that boys, thus educated, would hereafter fall victims to the Bibliomania?

[22] The history of this great men, and of his literary labours, is most interesting. He was a pupil of William Lilly, the first head-master of St. Paul's School; and, by the kindness and liberality of a Mr. Myles, he afterwards received the advantage of a College education, and was supplied with money in order to travel abroad, and make such collections as he should deem necessary for the great work which even then seemed to dawn upon his young and ardent mind. Leland endeavoured to requite the kindness of his benefactor by an elegant copy of Latin verses, in which he warmly expatiates on the generosity of his patron, and acknowledges that his acquaintance with the Almæ Matres [for he was of both Universities] was entirely the result of such beneficence. While he resided on the continent, he was admitted into the society of the most eminent Greek and Latin Scholars, and could probably number among his correspondents the illustrious names of Budæus, Erasmus, the Stephani, Faber and Turnebus. Here, too, he cultivated his natural taste for poetry; and from inspecting the fine books which the Italian and French presses had produced, as well as fired by the love of Grecian learning, which had fled, on the sacking of Constantinople, to take shelter in the academic bowers of the Medici, he seems to have matured his plans for carrying into effect the great work which had now taken full possession of his mind. He returned to England, resolved to institute an inquiry into the state of the Libraries, Antiquities, Records and Writings then in existence. Having entered into holy orders, and obtained preferment at the express interposition of the King, (Henry VIII.), he was appointed his Antiquary and Library Keeper, and a royal commission was issued in which Leland was directed to search after "England's Antiquities, and peruse the libraries of all Cathedrals, Abbies, Priories, Colleges, etc., as also all the places wherein Records, Writings, and Secrets of Antiquity were reposited." "Before Leland's time," says Hearne, in the Preface to the Itinerary, "all the literary monuments of Antiquity were totally disregarded; and Students of Germany, apprised of this culpable indifference, were suffered to enter our libraries unmolested, and to cut out of the books deposited there whatever passages they thought proper—which they afterwards published as relics of the ancient literature of their own country."

Leland was occupied, without intermission, in this immense undertaking, for the space of six years; and, on its completion, he hastened to the metropolis to lay at the feet of his Sovereign the result of his researches. This was presented to Henry under the title of A New Year's Gift; and was first published by Bale in 1549, 8vo. "Being inflamed," says the author, "with a love to see thoroughly all those parts of your opulent and ample realm, in so much that all my other occupations intermitted, I have so travelled in your dominions, both by the sea coasts and the middle parts, sparing neither labour nor costs, by the space of six years past, that there is neither cape nor bay, haven, creek, or pier, river, or confluence of rivers, breeches, wastes, lakes, moors, fenny waters, mountains, vallies, heaths, forests, chases, woods, cities, burghes, castles, principal manor places, monasteries and colleges, but I have seen them; and noted, in so doing, a whole world of things very memorable." Leland moreover tells his Majesty—that "By his laborious journey and costly enterprise, he had conserved many good authors, the which otherwise had been like to have perished; of the which, part remained in the royal palaces, part also in his own custody, &c."

As Leland was engaged six years in this literary tour, so he was occupied for a no less period of time in digesting and arranging the prodigious number of MSS. he had collected. But he sunk beneath the immensity of the task! The want of amanuenses, and of other attentions and comforts, seems to have deeply affected him; in this melancholy state, he wrote to Archbishop Cranmer a Latin epistle, in verse, of which the following is the commencement—very forcibly describing his situation and anguish of mind.

|

Est congesta mihi domi supellex Ingens, aurea, nobilis, venusta Qua totus studeo Britanniarum Vero reddere gloriam nitori. Sed fortuna meis noverca cœptis Jam felicibus invidet maligna. Quare, ne pereant brevi vel hora Multarum mihi noctium labores Omnes—— Cranmere, eximium decus piorum! Implorare tuam benignitatem Cogor. |

The result was that Leland lost his senses; and, after lingering two years in a state of total derangement, he died on the 18th of April, 1552. "Prôh tristes rerum humanarum vices! prôh viri optimi deplorandam infelicissimamque sortem!" exclaims Dr. Smith, in his preface to Camden's Life, 1691, 4to.

The precious and voluminous MSS. of Leland were doomed to suffer a fate scarcely less pitiable than that of their owner. After being pilfered by some, and garbled by others, they served to replenish the pages of Stow, Lambard, Camden, Burton, Dugdale, and many other antiquaries and historians. Polydore Virgil, who had stolen from them pretty freely, had the insolence to abuse Leland's memory—calling him "a vain glorious man;" but what shall we say to this flippant egotist? who, according to Caius's testimony [De Antiq. Cantab. head. lib. 1.] "to prevent a discovery of the many errors of his own History of England, collected and burnt a greater number of ancient histories and manuscripts than would have loaded a waggon." The imperfect remains of Leland's MSS. are now deposited in the Bodleian Library, and in the British Museum.

Upon the whole, it must be acknowledged that Leland is a melancholy, as well as illustrious, example of the influence of the Bibliomania!

[23] In spite of Bale's coarseness, positiveness, and severity, he has done much towards the cause of learning; and, perhaps, towards the propagation of the disease under discussion. His regard for Leland does him great honour; and although his plays are miserably dull, notwithstanding the high prices which the original editions of them bear, (vide ex. gr. Cat. Steevens, No. 1221; which was sold for £12 12s. See also the reprints in the Harleian Miscellany) the lover of literary antiquities must not forget that his "Scriptores Britanniæ" are yet quoted with satisfaction by some of the most respectable writers of the day. That he wanted delicacy of feeling, and impartiality of investigation, must be admitted; but a certain rough honesty and prompt benevolence which he had about him compensated for a multitude of offences. The abhorrence with which he speaks of the dilapidation of some of our old libraries must endear his memory to every honest bibliographer: "Never (says he) had we been offended for the loss of our Libraries, being so many in number, and in so desolate places for the more part, if the chief monuments and most notable works of our excellent writers had been reserved. If there had been in every shire of England, but one solempne Library, to the preservation of those noble works, and preferment of good learning in our posterity, it had been yet somewhat. But to destroy all without consideration, is, and will be, unto England for ever, a most horrible infamy among the grave seniors of other nations. A great number of them which purchased those superstitious mansions, reserved of those library-books, some to serve the jakes, some to scour their candlesticks, and some to rub their boots: some they sold to the grocers and soap-sellers; some they sent over sea to the book-binders, not in small number, but at times whole ships full, to the wondering of the foreign nations. Yea, the Universities of this realm are not all clear of this detestable fact. But cursed is that belly which seeketh to be fed with such ungodly gain, and shameth his natural country. I know a merchant man, which shall at this time be nameless, that bought the contents of two noble libraries for forty shillings price; a shame it is to be spoken! This stuff hath he occupied in the stead of grey paper, by the space of more than ten years, and yet he hath store enough for as many year to come!" Bale's Preface to Leland's "Laboryouse journey, &c." Emprented at London by John Bale. Anno M.D. xlix. 8vo.

After this, who shall doubt the story of the Alexandrian Library supplying the hot baths of Alexandria with fuel for six months! See Gibbon on the latter subject; vol. ix. 440.

[24] Ascham's English letter, written when he was abroad, will be found at the end of Bennet's edition of his works, in 4to. They are curious and amusing. What relates to the Bibliomania I here select from similar specimens. "Oct. 4. At afternoon I went about the town [of Bruxelles]. I went to the frier Carmelites house, and heard their even song: after, I desired to see the Library. A frier was sent to me, and led me into it. There was not one good book but Lyra. The friar was learned, spoke Latin readily, entered into Greek, having a very good wit, and a greater desire to learning. He was gentle and honest, &c." p. 370-1. "Oct. 20. to Spira: a good city. Here I first saw Sturmius de periodis. I also found here Ajax, Electra, and Antigone Sophocles, excellently, by my good judgment, translated into verse, and fair printed this summer by Gryphius. Your stationers do ill, that at least do 'not provide you the register of all books, especially of old authors, &c.'" p. 372. Again: "Hieronimus Wolfius, that translated Demosthenes and Isocrates, is in this town. I am well acquainted with him, and have brought him twice to my Lord's to dinner. He looks very simple. He telleth me that one Borrheus, that hath written well upon Aristot. priorum, &c., even now is printing goodly commentaries upon Aristotle's Rhetoric. But Sturmius will obscure them all." p. 381.

It is impossible to read these extracts without being convinced that Roger Ascham was a book-hunter, and infected with the Bibliomania!

If we are to judge from the beautiful Missal lying open before Lady Jane Grey, in Mr. Copley's elegant picture now exhibiting at the British Institution, it would seem rational to infer that this amiable and learned female was slightly attacked by the disease. It is to be taken for granted that Queen Elizabeth was not exempt from it; and that her great Secretary,[25] Cecil, sympathised with her! In regard to Elizabeth, her Prayer-Book[26] is quite evidence sufficient forB. 21 me that she found the Bibliomania irresistible! During her reign, how vast and how frightful were the ravages of the Book-madness! If we are to credit Laneham's celebrated Letter, it had extended far into the country, and infected some of the worthy inhabitants of Coventry; for one "Captain Cox,[27] by profession a mason, and that right skilful," had "as fair a library of sciences, and as many goodly monuments both in Prose and Poetry, and at afternoon could talk as much without book, as any Innholder betwixt Brentford and Bagshot, what degree soever he be!"

[25] It is a question which requires more time for the solution than I am able to spare, whether Cecil's name stands more frequently at the head of a Dedication, in a printed book, or of State Papers and other political documents in MS. He was a wonderful man; but a little infected—as I suspect—with the book-disease.

|

——Famous Cicill, treasurer of the land, Whose wisedom, counsell, skill of Princes state The world admires—— The house itselfe doth shewe the owners wit, And may for bewtie, state, and every thing, Compared be with most within the land. Tale of Two Swannes, 1590. 4to. |

I have never yet been able to ascertain whether the owner's attachment towards vellum, or large paper, Copies was the more vehement!

[26] Perhaps this conclusion is too precipitate. But whoever looks at Elizabeth's portrait, on her bended knees, struck off on the reverse of the title page to her prayer book (first printed in 1565) may suppose that the Queen thought the addition of her own portrait would be no mean decoration to the work. Every page is adorned with borders, engraved on wood, of the most spirited execution: representing, amongst other subjects, "The Dance of Death." My copy is the reprint of 1608—in high preservation. I have no doubt that there was a presentation copy printed upon vellum; but in what cabinet does this precious gem now slumber?

[27] Laneham gives a splendid list of Romances and Old Ballads possessed by this said Captain Cox; and tells us, moreover, that "he had them all at his fingers ends." Among the ballads we find "Broom broom on Hil; So Wo is me begon twlly lo; Over a Whinny Meg; Hey ding a ding; Bony lass upon Green; My bony on gave me a bek; By a bank as I lay; and two more he had fair wrapt up in parchment, and bound with a whip cord." Edit. 1784, p. 36-7-8. Ritson, in his Historical Essay on Scottish Song, speaks of some of these, with a zest, as if he longed to untie the "whip-cord" packet.

While the country was thus giving proofs of the prevalence of this disorder, the two Harringtons (especially the younger)[28] and the illustrious Spenser[29]B. 22 were unfortunately seized with it in the metropolis.

[28] Sir John Harrington, knt. Sir John, and his father John Harrington, were very considerable literary characters in the 16th century; and whoever has been fortunate enough to read through Mr. Park's new edition of the Nugæ Antiquæ, 1804, 8vo., will meet with numerous instances in which the son displays considerable bibliographical knowledge—especially in Italian literature; Harrington and Spenser seem to have been the Matthias and Roscoe of the day. I make no doubt but that the former was as thoroughly acquainted with the vera edizione of the Giuntæ edition of Boccaccio's Decamerone, 1527, 4to., as either Haym, Orlandi, or Bandini. Paterson, with all his skill, was mistaken in this article when he catalogued Croft's books. See Bibl. Crofts. No. 3976: his true edition was knocked down for 6s.!!!

[29] Spenser's general acquaintance with Italian literature has received the best illustration in Mr. Todd's Variorum edition of the poet's works; where the reader will find, in the notes, a constant succession of anecdotes of, and references to, the state of anterior and contemporaneous literature, foreign and domestic.

In the seventeenth century, from the death of Elizabeth to the commencement of Anne's reign, it seems to have made considerable havoc; yet, such was our blindness to it that we scrupled not to engage in overtures for the purchase of Isaac Vossius's[30] fine library, enriched with many treasures from the Queen of Sweden's, which this versatile genius scrupled not to pillage without confession or apology. During this century our great reasoners and philosophers began to be in motion; and, like the fumes of tobacco, which drive the concealed and clotted insects from the interior to the extremity of the leaves, the infectious particles of the Bibliomania set a thousand busy brains a-thinking, and produced ten thousand capricious works, which, over-shadowed by the majestic remains of Bacon, Locke, and Boyle, perished for want of air, and warmth, and moisture.

[30] "The story is extant, and written in very choice French." Consult Chauffepié's Supplement to Bayle's Dictionary, vol. iv. p. 621. note Q. Vossius's library was magnificent and extensive. The University of Leyden offered not less than 36,000 florins for it. Idem. p. 631.

The reign of Queen Anne was not exempt from the influence of this disease; for during this period, Maittaire[31] began to lay the foundation of his extenB. 23sive library, and to publish some bibliographical works which may be thought to have rather increased, than diminished, its force. Meanwhile, Harley[32] Earl ofB. 24 Oxford watched its progress with an anxious eye; and although he might have learnt experience from the fatal examples of R. Smith,[33] and T. Baker,[34] and theB. 25 more recent ones of Thomas Rawlinson,[35] Bridges,[36] and Collins,[37] yet he seemed resolved to brave and to baffle it; but, like his predecessors, he was suddenlyB. 26 crushed within the gripe of the demon, and fell one of the most splendid of his victims. Even the unrivalledB. 27 medical skill of Mead[38] could save neither his friend nor himself. The Doctor survived his Lordship about twelve years; dying of the complaint called the Bibliomania! He left behind an illustrious character;B. 28 sufficient to flatter and soothe those who may tread in his footsteps, and fall victims to a similar disorder.

[31] Of Michael Maittaire I have given a brief sketch in my Introduction to the Greek and Latin Classics, vol. I, 148. Mr. Beloe, in the 3rd vol. of his Anecdotes of Literature, p. ix., has described his merits with justice. The principal value of Maittaire's Annales Typographici consists in a great deal of curious matter detailed in the notes; but the absence of the "lucidus ordo" renders the perusal of these fatiguing and dissatisfactory. The author brought a full and well-informed mind to the task he undertook—but he wanted taste and precision in the arrangement of his materials. The eye wanders over a vast indigested mass; and information, when it is to be acquired with excessive toil, is, comparatively, seldom acquired. Panzer has adopted an infinitely better plan, on the model of Orlandi; and, if his materials had been printed with the same beauty with which they appear to have been composed, and his annals had descended to as late a period as those of Maittaire, his work must have made us, eventually, forget that of his predecessor. The bibliographer is, no doubt, aware that of Maittaire's first volume there are two editions. Why the author did not reprint, in the second edition (1733), the facsimile of the epigram and epistle of Lascar prefixed to the edition of the Anthology 1496, and the disquisition concerning the ancient editions of Quintilian (both of which were in the first edition of 1719), is absolutely inexplicable. Maittaire was sharply attacked for this absurdity, in the "Catalogus Auctorum," of the "Annus Tertius Sæcularis Inv. Art. Topog." Harlem, 1741, 8vo. p. 11. "Rara certe Librum augendi methodus (exclaims the author)! Satis patet auctorem hoc eo fecisse consilio, ut et primæ et secundæ Libri sive editioni pretium suum constaret, et una æque ac altera Lectoribus necessaria esset."

The catalogue of Maittaire's library [1748, 2 parts, 8vo.], which affords ample proof of the Bibliomania of its collector, is exceedingly scarce. A good copy of it, even unpriced, is worth a guinea: it was originally sold for 4 shillings; and was drawn up by Maittaire himself.

[32] In a periodical publication called "The Director," to which I contributed under the article of "Bibliographiana" (and of which the printer of this work, Mr. William Savage, is now the sole publisher), there was rather a minute analysis of the famous library of Harley, Earl of Oxford: a library which seems not only to have revived, but eclipsed, the splendour of the Roman one formed by Lucullus. The following is an abridgement of this analysis:

| VOLUMES. | ||

| 1. | Divinity: Greek, Latin, French and Italian—about | 2000 |

| —— English | 2500 | |

| 2. | History and Antiquities | 4000 |

| 3. | Books of Prints, Sculpture, and Drawings— Twenty Thousand Drawings and Prints. Ten Thousand Portraits. | |

| 4. | Philosophy, Chemistry, Medicine, &c. | 2500 |

| 5. | Geography, Chronology, General History | 600 |

| 6. | Voyages and Travels | 800 |

| 7. | Law | 800 |

| 8. | Sculpture and Architecture | 900 |

| 9. | Greek and Latin Classics | 2400 |

| 10. | Books printed upon vellum | 220 |

| 11. | English Poetry, Romances, &c. | 1000 |

| 12. | French and Spanish do. | 700 |

| 13. | Parliamentary Affairs | 400 |

| 14. | Trade and Commerce | 300 |

| 15. | Miscellaneous Subjects | 4000 |

| 16. | Pamphlets—Four Hundred Thousand! |

Mr. Gough says, these books "filled thirteen handsome chambers, and two long galleries." Osborne the bookseller purchased them for £13,000: a sum little more than two thirds of the price of the binding, as paid by Lord Oxford. The bookseller was accused of injustice and parsimony; but the low prices which he afterwards affixed to the articles, and the tardiness of their sale, are sufficient refutations of this charge. Osborne opened his shop for the inspection of the books on Tuesday the 14th of February, 1744; for fear "of the curiosity of the spectators, before the sale, producing disorder in the disposition of the books." The dispersion of the Harleian Collection is a blot in the literary annals of our country: had there then been such a Speaker, and such a spirit in the House of Commons, as we now possess, the volumes of Harley would have been reposing with the marbles of Townley!

[33] "Bibliotheca Smithiana: sive Catalogus Librorum in quavis facultate insigniorum, quos in usum suum et Bibliothecæ ornamentum multo ære sibi comparavit vir clarissimus doctissimusque D. Richardus Smith, &c., Londini, 1682," 4to. I recommend the collector of curious and valuable catalogues to lay hold upon the present one (of which a more particular description will be given in another work) whenever it comes in his way. The address "To the Reader," in which we are told that "this so much celebrated, so often desired, so long expected, library is now exposed to sale," gives a very interesting account of the owner. Inter alia, we are informed that Mr. Smith "was as constantly known every day to walk his rounds through the shops, as to sit down to his meals, &c.;" and that "while others were forming arms, and new-modelling kingdoms, his great ambition was to become master of a good book."

The catalogue itself justifies every thing said in commendation of the collector of the library. The arrangement is good; the books, in almost all departments of literature, foreign and domestic, valuable and curious; and among the English ones I have found some of the rarest Caxtons to refer to in my edition of Ames. What would Mr. Bindley, or Mr. Malone, or Mr. Douce, give to have the creaming of such a collection of "Bundles of Stitcht Books and Pamphlets," as extends from page 370 to 395 of this catalogue! But alas! while the Bibliographer exults in, or hopes for, the possession of such treasures, the physiologist discovers therein fresh causes of disease, and the philanthropist mourns over the ravages of the Bibliomania!

[34] Consult Masters's "Memoirs of the Life and Writings of the late Rev. Thomas Baker," Camb. 1864, 8vo. Let any person examine the catalogue of Forty-two folio volumes of "MS. collections by Mr. Baker," (as given at the end of this piece of biography) and reconcile himself, if he can, to the supposition that the said Mr. Baker did not fall a victim to the Book-disease! For some cause, I do not now recollect what, Baker took his name off the books of St. John's College, Cambridge, to which he belonged; but such was his attachment to the place, and more especially to the library, that he spent a great portion of the ensuing twenty years of his life within the precincts of the same: frequently comforted and refreshed, no doubt, by the sight of the magnificent large paper copies of Walton and Castell, and of Cranmer's Bible upon vellum!

[35] This Thomas Rawlinson, who is introduced in the Tatler under the name Tom Folio, was a very extraordinary character, and most desperately addicted to book-hunting. Because his own house was not large enough, he hired London House, in Aldersgate Street, for the reception of his library; and here he used to regale himself with the sight and the scent of innumerable black letter volumes, arranged in "sable garb," and stowed perhaps "three deep," from the bottom to the top of his house. He died in 1725; and Catalogues of his books for sale continued, for nine succeeding years, to meet the public eye. The following is a list of all the parts which I have ever met with; taken from copies in Mr. Heber's possession.

Part 1. A Catalogue of choice and valuable Books in most Faculties and Languages: being the sixth part of the collection made by Thos. Rawlinson, Esq., &c., to be sold on Thursday, the 2d day of March, 1726; beginning every evening at 5 of the clock, by Charles Davis, Bookseller. Qui non credit, eras credat. Ex Autog. T.R.

2. Bibliotheca Rawlinsoniana; sive Delectus Librorum in omni ferè Linguâ et Facultate præstantium—to be sold on Wednesday 26th April, [1726] by Charles Davis, Bookseller. 2600 Numbers.

3. The Same: January 1727-8. By Thomas Ballard, Bookseller, 3520 Numbers.

4. The Same: March, 1727-8. By the same. 3840 Numbers.

5. The Same: October, 1728. By the same. 3200 Numbers.

6. The Same: November, 1728. By the same. 3520 Numbers.

7. The Same: April, 1729. By the same. 4161 Numbers.

8. The Same: November, 1729. By the same. 2700 Numbers.

9. The Same: [Of Rawlinson's Manuscripts] By the same. March 1733-4. 800 Numbers.

10. Picturæ Rawlinsonianæ. April, 1734. 117 Articles.

At the end, it would seem that a catalogue of his prints, and MSS. missing in the last sale, were to be published the ensuing winter.

N.B. The black-letter books are catalogued in the Gothic letter.

[36] "Bibliothecæ Bridgesianæ Catalogus: or, A Catalogue of the Entire Library of John Bridges, late of Lincoln's Inn, Esq., &c., which will begin to be sold, by Auction, on Monday the seventh day of February, 1725-6, at his chambers in Lincoln's Inn, No. 6."

From a priced copy of this sale catalogue, in my possession, once belonging to Nourse, the bookseller in the Strand, I find that the following was the produce of the sale:

| The Amount of the books | £3730 | 0 | 0 |

| Prints and books of Prints | 394 | 17 | 6 |

| Total Amount of the Sale | £4124 | 17 | 6 |

Two different catalogues of this valuable collection of books were printed. The one was analysed, or a catalogue raisonné; to which was prefixed a print of a Grecian portico, &c., with ornaments and statues: the other (expressly for the sale) was an indigested and extremely confused one—to which was prefixed a print, designed and engraved by A. Motte, of an oak felled, with a number of men cutting down and carrying away its branches; illustrative of the following Greek motto inscribed on a scroll above—Δρυὸς πεσοὺσης πᾶς ἀνὴρ ξυλευεταὶ: "An affecting memento (says Mr. Nichols, very justly, in his Anecdotes of Bowyer, p. 557) to the collectors of great libraries, who cannot, or do not, leave them to some public accessible repository."

[37] In the year 1730-1, there was sold by auction, at St. Paul's Coffee-house, in St. Paul's Church-yard (beginning every evening at five o'clock), the library of the celebrated Free-Thinker,

Anthony Collins, Esq.