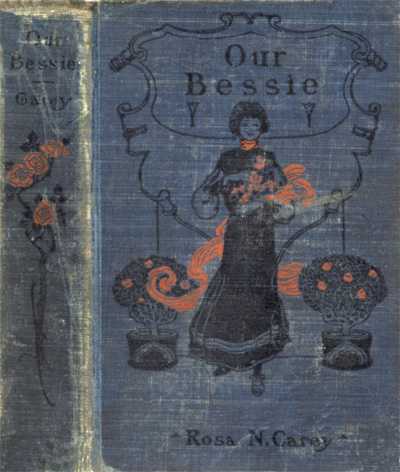

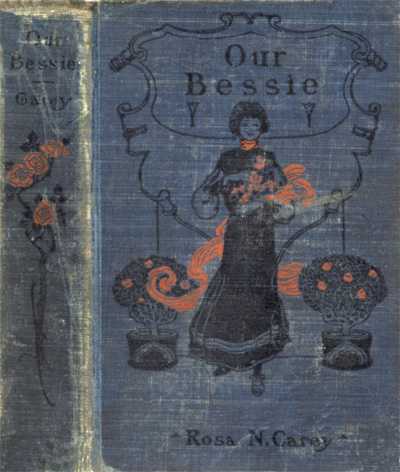

Title: Our Bessie

Author: Rosa Nouchette Carey

Release date: May 1, 2009 [eBook #28651]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

OUR BESSIE

BY

ROSA NOUCHETTE CAREY

AUTHOR OF “MERLE’S CRUSADE,” “NOT LIKE OTHER GIRLS,” “ONLY THE GOVERNESS,” ETC.

THE MERSHON COMPANY

RAHWAY, N. J. NEW YORK

| Page | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Bessie Meets with an Adventure | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| “Here Is Our Bessie” | 16 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Hatty | 31 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| A Cosy Morning | 46 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Oatlands Post-mark | 61 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Little Miss Much-afraid | 74 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| In the Kentish Lanes | 87 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| At the Grange | 101 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Richard Sefton | 115 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Bessie Is Introduced to Bill Sykes | 129 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Edna Has a Grievance | 148 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The First Sunday at the Grange | 156 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Whitefoot in Requisition | 171 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Bessie Snubs A Hero | 183 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| “She Will Not Come” | 197 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| A Note From Hatty | 209 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| “Trouble May Come To Me One Day” | 222 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| “Farewell, Night” | 236 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| “I Must Not Think of Myself” | 249 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| “Bessie’s Second Flitting” | 263 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| On the Parade | 276 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Bessie Buys A Japanese Fan | 289 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Mrs. Sefton Has Another Visitor | 303 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| In the Coombe Woods | 318 |

It was extremely tiresome!

It was vexatious; it was altogether annoying!

Most people under similar circumstances would have used stronger expressions, would have bemoaned themselves loudly, or at least inwardly, with all the pathos of self-pity.

To be nearly at the end of one’s journey, almost within sight and sound of home fires and home welcomes, and then to be snowed up, walled, imprisoned, kept in durance vile in an unexpected snowdrift—well, most human beings, unless gifted with angelic patience, and armed with special and peculiar fortitude, would have uttered a few groans under such depressing circumstances.

Fortunately, Bessie Lambert was not easily depressed. She was a cheerful young person, an optimist by nature; and, thanks to a healthy organization,[2] good digestion, and wholesome views of duty, was not given to mental nightmares, nor to cry out before she was hurt.

Bessie would have thought it faint-hearted to shrink at every little molehill of difficulty; she had plenty of what the boys call pluck (no word is more eloquent than that), and a fund of quiet humor that tided her safely over many a slough of despond. If any one could have read Bessie’s thoughts a few minutes after the laboring engine had ceased to work, they would have been as follows, with little staccato movements and pauses:

“What an adventure! How Tom would laugh, and Katie too! Katie is always longing for something to happen to her; but it would be more enjoyable if I had some one with me to share it, and if I were sure father and mother would not be anxious. An empty second-class compartment is not a particularly comfortable place on a cold afternoon. I wonder how it would be if all the passengers were to get out and warm themselves with a good game of snowballing. There is not much room, though; we should have to play it in a single file, or by turns. Supposing that, instead of that, the nice, white-haired old gentleman who got in at the last station were to assemble us all in the third-class carriage and tell us a story about Siberia; that would be[3] nice and exciting. Tom would suggest a ghost story, a good creepy one; but that would be too dismal. The hot-water tin is getting cold, but I have got a rug, I am thankful to say, so I shall not freeze for the next two hours. If I had only a book, or could go to sleep—oh!” in a tone of relief, as the guard’s face was suddenly thrust in at the open window.

“I beg your pardon, miss; I hope I did not startle you; but there is a young lady in the first-class compartment who, I take it, would be the better for a bit of company; and as I saw you were alone, I thought you might not object to change your carriage.”

“No, indeed; I shall be delighted to have a companion,” returned Bessie briskly. “How long do you think we shall be detained here, guard?”

“There is no knowing, miss; but one of our men is working his way back to the signals. We have not come more than three miles since we left Cleveley. It is only a bit of a drift that the snow-plow will soon clear, and it will be a matter of two or three hours, I dare say; but it has left off snowing now.”

“Will they telegraph to Cliffe the reason of the delay?” asked Bessie, a little anxiously.

“Oh, yes, they will do that right enough; you[4] needn’t be uneasy. The other young lady is in a bit of a fuss, too, but I told her there was no danger. Give a good jump, miss; there, now you are all right. I will take care of your things. Follow me, please; it is only a step or so.”

“This is more of an adventure than ever,” thought Bessie, as she followed the big, burly guard. “What a kind man he is! Perhaps he has daughters of his own.” And she thanked him so warmly and so prettily as he almost lifted her into the carriage, that he muttered, as he turned away:

“That’s a nice, pleasant little woman. I like that sort.”

The first-class compartment felt warm and snug. Its only tenant was a fair, pretty-looking girl, dressed very handsomely in a mantle trimmed with costly fur, and a fur-lined rug over her knees.

“Oh, thank you! How good of you to come!” she exclaimed eagerly; and Bessie saw at once that she had been crying. “I was feeling so frightened and miserable all by myself. I got it into my head that another train would run into us, and I was quite in a panic until the guard assured me there was no danger. He told me that there was another young lady alone, and that he would bring her to me.”

“Yes, that was so nice of him; and of course it is pleasanter to be able to speak to somebody,” returned[5] Bessie cheerfully; “and it is so much warmer here.”

“Take some of my rug; I do not need it all myself; and we may as well be as comfortable as we can, under the miserable circumstances.”

“Well, do you know I think it might be worse?”

“Worse! how can you talk so?” with a shudder.

“Why, it can hardly be a great hardship to sit for another two hours in this nice warm carriage, with this beautiful rug to cover us. It certainly was a little dull and cold in the other compartment, and I longed to get out and have a game of snowballing to warm myself.” But here her companion gave a little laugh.

“What a funny idea! How could you think of such a thing?” And here she looked, for the first time, rather scrutinizingly at Bessie. Oh, yes, she was a lady—she spoke nicely and had good manners; but how very shabbily she was dressed—at least, not shabbily; that was not the right word—inexpensively would have been the correct term.

Bessie’s brown tweed had evidently seen more seasons than one; her jacket fitted the trim figure, but was not made in the last fashion; and the brown velvet on her hat was decidedly worn. How was the young lady to know that Bessie was wearing her oldest things from a sense of economy, and that her new[6] jacket and best hat—a very pretty one—were in the neat black box in the luggage-van?

Certainly the two girls were complete opposites. Bessie, who, as her brother Tom often told her, was no beauty, was, notwithstanding, a bright, pleasant-looking girl, with soft gray eyes that could express a great deal of quiet sympathy on occasions, or could light up with fun. People who loved her always said Bessie’s face was better than a beautiful one, for it told nothing but the truth about itself. It did not say, “Come, admire me,” as some faces say, but, “Come, trust me if you can.”

The fashionably dressed young stranger had a very different type of face. In the first place, it was undeniably pretty; no one ever thought of contradicting that fact, though a few people might have thought it a peculiar style of beauty, for she had dark-brown eyes and fair hair—rather an uncommon combination.

She was small, too, and very pale, and yet not fragile-looking; on the contrary, she had a clear look of health, but there was a petulant curve about the mouth that spoke of quick temper, and the whole face seemed capable of great mobility, quick changes of feeling that were perfectly transparent.

Bessie was quite aware that her new acquaintance was taking stock of her; she was quietly amused, but she took no apparent notice.

[7]“Is Cliffe-on-Sea your destination?” she asked presently.

“No; is it yours?” with a quick note of alarm in her voice. “Oh, I am so sorry!” as Bessie nodded. “I hoped we should have travelled together to London. I do dislike travelling alone, but my friend was too ill to accompany me, and I did not want to stay at Islip another day; it was such a stupid place, so dull; so I said I must come, and this is the result.”

“And you are going to London? Why, your journey is but just beginning. Cliffe-on-Sea is where I live, and we cannot be more than two miles off. Oh, what will you do if we are detained here for two or three hours?”

“I am sure I don’t know,” returned the other girl disconsolately, and her eyes filled with tears again. “It is nearly five now, and it will be too late to go on to London; but I dare not stay at a hotel by myself. What will mamma say? She will be dreadfully vexed with me for not waiting for Mrs. Moultrie—she never will let me travel alone, and I have disobeyed her.”

“That is a great pity,” returned Bessie gravely; but politeness forbade her to say more. She was old-fashioned enough to think that disobedience to parents was a heinous offence. She did not understand the[8] present code, that allows young people to set up independent standards of duty. To her the fifth commandment was a very real commandment, and just as binding in the nineteenth century as when the young dwellers in tents first listened to it under the shadow of the awful Mount.

Bessie’s gravely disapproving look brought a mocking little smile to the other girl’s face; her quick comprehension evidently detected the rebuke, but she only answered flippantly:

“Mamma is too much used to my disobedience to give it a thought; she knows I will have my way in things, and she never minds; she is sensible enough to know grown-up girls generally have wills of their own.”

“I think I must have been brought up differently,” returned Bessie simply. “I recollect in our nursery days mother used to tell us that little bodies ought not to have grown-up wills; and when we got older, and wanted to get the reins in our own hands, as young people will, she would say, ‘Gently, gently, girls; you may be grown up, but you will never be as old as your parents—’” But here Bessie stopped, on seeing that her companion was struggling with suppressed merriment.

“It does sound so funny, don’t you know! Oh, I don’t mean to be rude, but are not your people just[9] a little bit old-fashioned and behind the times? I don’t want to shock you; I am far too grateful for your company. Mamma and I thoroughly understand each other. I am very fond of her, and I am as sorry as possible to vex her by getting into this mess;” and here the girl heaved a very genuine sigh.

“And you live in London?” Bessie was politely changing the subject.

“Oh, no; but we have some friends there, and I was going to break my journey and do a little shopping. Our home is in Kent; we live at Oatlands—such a lovely, quiet little place—far too quiet for me; but since I came out mamma always spends the season in town. The Grange—that is our house—is really Richard’s—my brother’s, I mean.”

“The Grange—Oatlands? I am sure I know that name,” returned Bessie, in a puzzled tone; “and yet where could I have heard it?” She thought a moment, and then added quickly, “Your name cannot be Sefton?”

“To be sure it is,” replied the other girl, opening her brown eyes rather wildly; “Edna Sefton; but how could you have guessed it?”

“Then your mother’s name is Eleanor?”

“I begin to think this is mysterious, and that you must be a witch, or something uncanny. I know all[10] mamma’s friends, and I am positive not one of them ever lived at Cliffe-on-Sea.”

“And you are quite sure of that? Has your mother never mentioned the name of a Dr. Lambert?”

“Dr. Lambert! No. Wait a moment, though. Mamma is very fond of talking about old days, when she was a girl, don’t you know, and there was a young doctor, very poor, I remember, but his name was Herbert.”

“My father’s name is Herbert, and he was very poor once, when he was a young man; he is not rich now. I think, many years ago, he and your mother were friends. Let me tell you all I know about it. About a year ago he asked me to post a letter for him. I remember reading aloud the address in an absent sort of way: ‘Mrs. Sefton, The Grange, Oatlands, Kent;’ and my father looked up from his writing, and said, ‘That is only a business letter, Bessie, but Mrs. Sefton and I are old correspondents. When she was Eleanor Sartoris, and I was a young fellow as poor as a church mouse, we were good friends; but she married, and then I married; but that is a lifetime ago; she was a handsome girl, though.’”

“Mamma is handsome now. How interesting it all is! When I get home I shall coax mamma to[11] tell me all about it. You see, we are not strangers after all, so we can go on talking quite like old friends. You have made me forget the time. Oh dear, how dark it is getting! and the gas gives only a glimmer of light.”

“It will not be quite dark, because of the snow. Do not let us think about the time. Some of the passengers are walking about. I heard them say just now the man must have reached Cleveley, so the telegram must have gone—we shall soon have help. Of course, if the snow had not ceased falling, it would have been far more serious.”

“Yes,” returned Miss Sefton, with a shiver; “but it is far nicer to read of horrid things in a cheerful room and by a bright fire than to experience them one’s self. Somehow one never realizes them.”

“That is what father says—that young people are not really hard-hearted, only they do not realize things; their imagination just skims over the surface. I think it is my want of imagination helps me. I never will look round the corner to try and find out what disagreeable thing is coming next. One could not live so and feel cheerful.”

“Then you are one of those good people, Miss Lambert, who think it their duty to cultivate cheerfulness. I was quite surprised to see you look so tranquil, when I had been indulging in a babyish fit[12] of crying, from sheer fright and misery; but it made me feel better only to look at you.”

“I am so glad,” was Bessie’s answer. “I remember being very much struck by a passage in an essay I once read, but I can only quote it from memory; it was to the effect that when a cheerful person enters a room it is as though fresh candles are lighted. The illustration pleases me.”

“True, it was very telling. Yes, you are cheerful, and you are very fond of talking.”

“I am afraid I am a sad chatterbox,” returned Bessie, blushing, as though she were conscious of an implied reproof.

“Oh, but I like talking people. People who hold their tongues and listen are such bores. I do detest bores. I talk a great deal myself.”

“I think I have got into the way for Hatty’s sake. Hatty is the sickly one of our flock; she has never been strong. When she was a tiny, weeny thing she was always crying and fretful. Father tells us that she cannot help it, but he never says so to her; he laughs and calls her ‘Little Miss Much-Afraid.’ Hatty is full of fear. She cannot see a mouse, as I tell her, without looking round the corner for pussy’s claws.”

“Is Hatty your only sister, Miss Lambert?”

“Oh, no; there are three more. I am the eldest[13]—‘Mother’s crutch,’ as they call me. We are such a family for giving each other funny names. Tom comes next. I am three-and-twenty—quite an old person, as Tom says—and he is one-and-twenty. He is at Oxford; he wants to be a barrister. Christine comes next to Tom—she is nineteen, and so pretty; and then poor Hatty—‘sour seventeen,’ as Tom called her on her last birthday; and then the two children, Ella and Katie; though Ella is nearly sixteen, and Katie fourteen, but they are only school-girls.”

“What a large family!” observed Miss Sefton, stifling a little yawn. “Now, mamma has only got me, for we don’t count Richard.”

“Not count your brother?”

“Oh, Richard is my step-brother; he was papa’s son, you know; that makes a difference. Papa died when I was quite a little girl, so you see what I mean by saying mamma has only got me.”

“But she has your brother, too,” observed Bessie, somewhat puzzled by this.

“Oh, yes, of course.” But Miss Sefton’s tone was enigmatical, and she somewhat hastily changed the subject by saying, plaintively, “Oh, dear, do please tell me, Miss Lambert, what you think I ought to do when we reach Cliffe, if we ever do reach it. Shall I telegraph to my friends in London, and go[14] to a hotel? Perhaps you could recommend me one, or——”

“No; you shall come home with me,” returned Bessie, moved to this sudden inspiration by the weary look in Miss Sefton’s face. “We are not strangers; my father and your mother were friends; that is sufficient introduction. Mother is the kindest woman in the world—every one says so. We are not rich people, but we can make you comfortable. To be sure, there is not a spare room; our house is not large, and there are so many of us; but you shall have my room, and I will have half of Chrissy’s bed. You are too young”—and here Bessie was going to add “too pretty,” only she checked herself——“to go alone to a hotel. Mother would be dreadfully shocked at the idea.”

“You are very kind—too kind; but your people might object,” hesitated Miss Sefton.

“Mother never objects to anything we do; at least, I might turn it the other way about, and say we never propose anything to which she is likely to object. When my mother knows all about it, she will give you a hearty welcome.”

“If you are quite sure of that, I will accept your invitation thankfully, for I am tired to death. You are goodness itself to me, but I shall not like turning you out of your room.”

[15]“Nonsense. Chriss and I will think it a bit of fun—oh, you don’t know us yet. So little happens in our lives that your coming will be quite an event; so that is settled.” And Bessie extended a plump little hand in token of her good will, which Miss Sefton cordially grasped.

An interruption occurred at this moment. The friendly guard made his appearance again, accompanied by the same white-haired old clergyman whom Bessie had noticed. He came to offer his services to the young ladies. He cheered Miss Sefton’s drooping spirits by reiterating the guard’s assurance that they need only fear the inconvenience of another hour’s delay.

The sight of the kind, benevolent countenance was reassuring and comforting, and after their new friend had left them the girls resumed their talk with fresh alacrity.

Miss Sefton was the chief speaker. She began recounting the glories of a grand military ball at Knightsbridge, at which she had been present, and some private theatricals and tableaux that had followed. She had a vivid, picturesque way of describing things, and Bessie listened with a sort of dreamy fascination that lulled her into forgetfulness of her parents’ anxiety.[17]

In spite of her alleged want of imagination, she was conscious of a sort of weird interest in her surroundings. The wintry afternoon had closed into evening, but the whiteness of the snow threw a dim brightness underneath the faint starlight, while the gleam of the carriage lights enabled them to see the dark figures that passed and repassed underneath their window.

It was intensely cold, and in spite of her furs Miss Sefton shivered and grew perceptibly paler. She was evidently one of those spoiled children of fortune who had never learned lessons of endurance, who are easily subdued and depressed by a passing feeling of discomfort; even Bessie’s sturdy cheerfulness was a little infected by the unnatural stillness outside. The line ran between high banks, but in the mysterious twilight they looked like rocky defiles closing them in.

After a time Bessie’s attention wandered, and her interest flagged. Military balls ceased to interest her as the temperature grew lower and lower. Miss Sefton, too, became silent, and Bessie’s mind filled with gloomy images. She thought of ships bedded in ice in Arctic regions; of shipwrecked sailors on frozen seas; of lonely travellers laying down their weary heads on pillows of snow, never to rise again; of homeless wanderers, outcasts from society, many[18] with famished babes at their breasts, cowering under dark arches, or warming themselves at smoldering fires.

“Thank God that, as father says, we cannot realize what people have to suffer,” thought Bessie. “What would be the use of being young and happy and free from pain, if we were to feel other people’s miseries? Some of us, who are sympathetic by nature, would never smile again. I don’t think when God made us, and sent us into the world to live our own lives, that He meant us to feel like that. One can’t mix up other people’s lives with one’s own; it would make an awful muddle.”

“Miss Lambert, are you asleep, or dreaming with your eyes open? Don’t you see we are moving? There was such a bustle just now, and then they got the steam up, and now the engine is beginning to work. Oh! how slowly we are going! I could walk faster. Oh! we are stopping again—no, it is only my fancy. Is not the shriek of the whistle musical for once?”

“I was not asleep; I was only thinking; but my thoughts had travelled far. Are we really moving? There, the snow-plow has cleared the line; we shall go on faster presently.”

“I hope so; it is nearly eight. I ought to have reached London an hour ago. Poor Neville, how[19] disappointed he will be. Oh, we are through the drift now and they are putting on more steam.”

“Yes, we shall be at Cliffe in another ten minutes;” and Bessie roused in earnest. Those ten minutes seemed interminable before the lights of the station flashed before their eyes.

“Here she is—here is our Bessie!” exclaimed a voice, and a fine-looking young fellow in an ulster ran lightly down the platform as Bessie waved her handkerchief. He was followed more leisurely by a handsome, gray-haired man with a quiet, refined-looking face.

“Tom—oh, Tom!” exclaimed Bessie, almost jumping into his arms, as he opened the carriage door. “Were mother and Hattie very frightened? Why, there is father!” as Dr. Lambert hurried up.

“My dear child, how thankful I am to see you! Why, she looks quite fresh, Tom.”

“As fit as possible,” echoed Tom.

“Yes, I am only cold. Father, the guard put me in with a young lady. She was going to London, but it is too late for her to travel alone, and she is afraid of going to a hotel. May I bring her home? Her name is Edna Sefton. She lives at The Grange, Oatlands.”

Dr. Lambert seemed somewhat taken aback by his daughter’s speech.

[20]“Edna Sefton! Why, that is Eleanor Sefton’s daughter! What a strange coincidence!” And then he muttered to himself, “Eleanor Sartoris’ daughter under our roof! I wonder what Dora will say?” And then he turned to the fair, striking-looking girl whom Tom was assisting with all the alacrity that a young man generally shows to a pretty girl: “Miss Sefton, you will be heartily welcome for your mother’s sake; she and I were great friends in the ’auld lang syne.’ Will you come with me? I have a fly waiting for Bessie; my son will look after the luggage;” and Edna obeyed him with the docility of a child.

But she glanced at him curiously once or twice as she walked beside him. “What a gentlemanly, handsome man he was!” she thought. Yes, he looked like a doctor; he had the easy, kindly manner which generally belongs to the profession. She had never thought much about her own father, but to-night, as they drove through the lighted streets, her thoughts, oddly enough, recurred to him. Dr. Lambert was sitting opposite the two girls, but his eyes were fixed oftenest on his daughter.

“Your mother was very anxious and nervous,” he said, “and so was Hatty, when Tom brought us word that the train was snowed up in Sheen Valley I had to scold Hatty, and tell her she was a goose; but mother was nearly as bad; she can’t do without[21] her crutch, eh, Bessie?” with a gleam of tenderness in his eyes, as they rested on his girl.

Edna felt a little lump in her throat, though she hardly knew why; perhaps she was tired and over-strained; she had never missed her father before, but she fought against the feeling of depression.

“I am so sorry your son has to walk,” she said politely; but Dr. Lambert only smiled.

“A walk will not hurt him, and our roads are very steep.”

As he spoke, the driver got down, and Bessie begged leave to follow his example.

“We live on the top of the hill,” she said apologetically; “and I cannot bear being dragged up by a tired horse, as father knows by this time;” and she joined her brother, who came up at that moment.

Tom had kept the fly well in sight.

“That’s an awfully jolly-looking girl, Betty,” he observed, with the free and easy criticism of his age. “I don’t know when I have seen a prettier girl; uncommon style, too—fair hair and dark eyes; she is a regular beauty.”

“That is what boys always think about,” returned Bessie, with good-humored contempt. “Girls are different. I should be just as much interested in Miss Sefton if she were plain. I suppose you mean[22] to be charmed with her conversation, and to find all her remarks witty because she has les beaux yeux.”

“I scorn to take notice of such spiteful remarks,” returned Tom, with a shrug. “Girls are venomous to each other. I believe they hate to hear one another praised, even by a brother.”

“Hold your tongue, Tom,” was the rejoinder. “It takes my breath away to argue with you up this hill. I am not too ill-natured to give up my own bed to Miss Sefton. Let us hurry on, there’s a good boy, or they will arrive before us.”

As this request coincided with Tom’s private wishes, he condescended to walk faster; and the brother and sister were soon at the top of the hill, and had turned into a pretty private road bordered with trees, with detached houses standing far back, with long, sloping strips of gardens. The moon had now risen, and Bessie could distinctly see a little group of girls, with shawls over their heads, standing on the top of a flight of stone steps leading down to a large shady garden belonging to an old-fashioned house. The front entrance was round the corner, but the drawing-room window was open, and the girls had gained the road by the garden way, and stood shivering and expectant; while the moon illumined the grass terraces that ran steeply from the house, and shone on the meadow that skirted the garden.

[23]“Run in, girls; you will catch cold,” called out Bessie; but her prudent suggestion was of no avail, for a tall, lanky girl rushed into the road with the rapturous exclamation, “Why, it is our Bessie after all, though she looked so tall in the moonlight, and I did not know Tom’s new ulster.” And here Bessie was fallen upon and kissed, and handed from one to another of the group, and then borne rapidly down the steps and across the terrace to the open window.

“Here she is, mother; here is our Bessie, not a bit the worse. And Hatty ought to be ashamed of herself for making us all miserable!” exclaimed Katie.

“My Hatty sha’n’t be scolded. Mother, dear, if you only knew how sweet home looks after the Sheen Valley! Don’t smother me any more, girls. I want to tell you something that will surprise you;” and Bessie, still holding her mother’s hand, but looking at Hatty, gave a rapid and somewhat indistinct account of her meeting with Edna Sefton.

“And she will have my room, mother,” continued Bessie, a little incoherently, for she was tired and breathless, and the girl’s exclamations were so bewildering.

Mrs. Lambert, a pale, care-worn woman, with a sweet pathetic sort of face, was listening with much[24] perplexity, which was not lessened by the sight of her husband ushering into the room a handsome-looking girl, dressed in the most expensive fashion.

“Dora, my dear, this is Bessie’s fellow-sufferer in the snowdrift; we must make much of her, for she is the daughter of my old friend, Eleanor Sartoris—Mrs. Sefton now. Bessie has offered her her own room to-night, as it is too late for her to travel to London.”

A quick look passed between the husband and wife, and a faint color came to Mrs. Lambert’s face, but she was too well-bred to express her astonishment.

“You are very welcome, my dear,” she said quietly. “We will make you as comfortable as we can. These are all my girls,” and she mentioned their names.

“What a lot of girls,” thought Edna. She was not a bit shy by nature, and somehow the situation amused her. “What a comfortable, homelike room, and what a lovely fire! And—well, of course, they were not rich; any one could see that; but they were nice, kind people.”

“This is better than the snowdrift,” she said, with a beaming smile, as Dr. Lambert placed her in his own easy chair, and Tom brought her a footstool and handed her a screen, and her old acquaintance Bessie helped her to remove her wraps. The whole family gathered round her, intent on hospitality to the bewitching[25] stranger—only the “Crutch,” as Tom called her, tripped away to order Jane to light a fire in her room, and to give out the clean linen for the unexpected guest, and to put a few finishing touches to the supper-table.

The others did not miss her at first. Christine, a tall, graceful girl who had inherited her father’s good looks, was questioning Edna about the journey, and the rest were listening to the answers.

Hatty, a pale, sickly-looking girl, whose really fine features were marred by unhealthy sullenness and an anxious, fretful expression, was hanging on every word; while the tall schoolgirl Ella, and the smaller, bright-eyed Katie, were standing behind their mother, trying to hide their awkwardness and bashfulness, till Tom came to the rescue by finding them seats, with a whispered hint to Katie that it was not good manners to stare so at a stranger. Edna saw everything with quiet, amused eyes; she satisfied Christine’s curiosity, and found replies to all Mrs. Lambert’s gentle, persistent questioning. Tom, too, claimed her attention by all sorts of dexterous wiles. She must look at him, and thank him, when he found that screen for her; she could not disregard him when he was so solicitous about the draft from the window, so anxious to bring her another cushion.

“I did not know you were such a ladies’ man,[26] Tom,” observed Dr. Lambert presently, in a tone that made Tom retreat with rather a foolish expression.

With all his love for his children, Dr. Lambert was sometimes capable of a smooth sarcasm. Tom felt as though he had been officious; had, in fact, made a fool of himself, and drew off into the background. His father was often hard on him, Tom said to himself, in an aggrieved way, and yet he was only doing his duty, as a son of the house, in waiting on this fascinating young lady.

“Poor boy, he is very young!” thought Edna, who noticed this by-play with some amusement; “but he will grow older some day, and he is very good-looking;” and then she listened with a pretty show of interest to a story Dr. Lambert was telling her of when he was snowed up in Scotland as a boy.

When Bessie returned she found them all in good spirits, and her fellow-traveller laughing and talking as though she had known them for years; even Tom’s brief sulkiness had vanished, and, unmindful of his father’s caustic tongue, he had again ventured to join the charmed circle.

It was quite late before the girls retired to rest, and as Edna followed Bessie up the broad, low staircase, while Tom lighted them from below, she called out gayly. “Good-night, Mr. Lambert; it was worth[27] while being snowed up in the Sheen Valley to make such nice friends, and to enjoy such a pleasant evening.”

Edna really meant what she said, for the moment; she was capable of these brief enthusiasms. Pleasantness of speech, that specious coinage of conventionality, was as the breath of life to her. Her girlish vanity was gratified by the impression she had made on the Lambert family, and even Tom’s crude, boyish admiration was worth something.

“To be all things to all men” is sometimes taken by vain, worldly people in a very different sense from that the apostle intended. Girls of Edna Sefton’s caliber—impressionable, vivacious, egotistical, and capable of a thousand varying moods—will often take their cue from other people, and become grave with the grave, and gay with the gay, until they weary of their role, and of a sudden become their true selves. And yet there is nothing absolutely wrong in these swift, natural transitions; many sympathetic natures act in the same way, by very reason and force of their sympathy. For the time being they go out of themselves, and, as it were, put themselves in other people’s places. Excessive sympathy is capable of minor martyrdom; their reflected suffering borders upon real pain.

When Bessie ushered Edna into her little room, she[28] looked round proudly at the result of her own painstaking thoughtfulness. A bright fire burned in the small grate, and her mother’s easy chair stood beside it—heavy as it was, Bessie had carried it in with her own hands. The best eider-down quilt, in its gay covering, was on the bed, and the new toilet-cover that Christine had worked in blue and white cross-stitch was on the table. Bessie had even borrowed the vase of Neapolitan violets that some patient had sent her father, and the sweet perfume permeated the little room.

Bessie would willingly have heard some encomium on the snug quarters provided for the weary guest, but Edna only looked round her indifferently, and then stifled a yawn.

“Is there anything you want? Can I help you? Oh, I hope you will sleep comfortably!” observed Bessie, a little mortified by Edna’s silence.

“Oh, yes: I am so tired that I am sure I shall sleep well,” returned Edna; and then she added quickly, “but I am so sorry to turn you out of your room.”

“Oh, that does not matter at all, thank you,” replied Bessie, stirring the fire into a cheerful blaze, and then bidding her guest good-night; but Edna, who had taken possession of the easy chair, exclaimed:

[29]“Oh, don’t go yet—it is only eleven, and I am never in bed until twelve. Sit down a moment, and warm yourself.”

“Mother never likes us to be late,” hesitated Bessie; but she lingered, nevertheless. This was not an ordinary evening, and there were exceptions to every rule, so she knelt down on the rug a moment, and watched Edna taking down the long plaits of fair hair that had crowned her shapely head. “What lovely hair!” thought Bessie; “what a beautiful young creature she is altogether!”

Edna was unconscious of the admiration she was exciting. She was looking round her, and trying to realize what her feelings would be if she had to inhabit such a room. “Why, our servants have better rooms,” she thought.

To a girl of Edna’s luxurious habits Bessie’s room looked very poor and mean. The little strips of faded carpet, the small, curtainless bedstead, the plain maple washstand and drawers, the few simple prints and varnished bookcase were shabby enough in Edna’s eyes. She could not understand how any girl could be content with such a room; and yet Bessie’s happiest hours were spent there. What was a little shabbiness, or the wear and tear of homely furniture, to one who saw angels’ footprints even in the common ways of life, and who dreamed sweet, innocent dreams of the splendors[30] of a heavenly home? To these sort of natures even threadbare garments can be worn proudly, for to these free spirits even poverty loses its sting. It is not “how we live,” but “how we think about life,” that stamps our characters, and makes us the men and women that we are.

The brief silence was broken by Edna.

“What a nice boy your brother is!” she observed, in rather a patronizing tone.

Bessie looked up in some surprise.

“Tom does not consider himself a boy, I assure you; he is one-and-twenty, and ever since he has gone to Oxford he thinks himself of great consequence. I dare say we spoil him among us, as he is our only brother now. If Frank had lived,” and here Bessie sighed, “he would have been five-and-twenty by this time; but he died four years ago. It was such a blow to poor father and mother; he was so good and clever, and he was studying for a doctor; but he caught a severe chill, and congestion of the lungs came on, and in a few days he was dead. I don’t think mother has ever been quite the same since his death—Frank was so much to her.”

“How very sad!” returned Edna sympathetically, for Bessie’s eyes had grown soft and misty as she[32] touched this chord of sadness; “it must be terrible to lose any one whom one loves.” And then she added, with a smile, “I did not mean to hurt your feelings by calling your brother a boy, but he seemed very young to me. You see, I am engaged, and Mr. Sinclair (that is my fiancé) is nearly thirty, and he is so grave and quiet that any one like your brother seems like a boy beside him.”

“You are engaged?” ejaculated Bessie, in an awestruck tone.

“Yes; it seems a pity, does it not? at least mamma says so; she thinks I am too young and giddy to know my own mind; and yet she is very fond of Neville—Mr. Sinclair, I mean. She will have it that we are not a bit suited to each other, and I dare say she is right, for certainly we do not think alike on a single point.”

Bessie’s eyes opened rather widely at this candid statement. She was a simple little soul, and had not yet learned the creed of emancipation. She held the old-fashioned views that her mother had held before her. Her mother seldom talked on these subjects, and Bessie had inherited this reticence. She listened with a sort of wondering disgust when her girl acquaintances chattered flippantly about their lovers, and boasted openly of their power over them.

[33]“If this sort of thing ever comes to me,” thought Bessie on these occasions, “I shall think it too wonderful and precious to make it the subject of idle conversation. How can any one take upon themselves the responsibility of another human being’s happiness—for that is what it really means—and turn it into a jest? It is far too sacred and beautiful a thing for such treatment. I think mother is right when she says, ‘Girls of the present day have so little reticence.’”

She hardly knew what to make of Edna’s speech; it was not exactly flippant, but it seemed so strange to hear so young a creature speak in that cool, matter-of-fact way.

“I don’t see how people are to get on together, if they do not think alike,” she observed, in a perplexed voice; but Edna only laughed.

“I am afraid we don’t get on. Mother says she never saw such a couple; that we are always quarrelling and making up like two children; but I put it to you, Miss Lambert, how are things to be better? I am used to my own way, and Mr. Sinclair is used to his. I like fun and plenty of change, and dread nothing so much as being bored—ennuyée, in fact, and he is all for quiet. Then he is terribly clever, and has every sort of knowledge at his fingers’ end. He is a barrister, and rising in his[34] profession, and I seldom open a book unless it be a novel.”

“I wonder why he chose you,” observed Bessie naïvely, and Edna seemed much amused by her frankness.

“Oh, how deliciously downright you are, Miss Lambert. Well, do you know I have not the faintest notion why Neville asked me to marry him, any more than I know why I listened to him. I tell him sometimes that it was the most ridiculous mistake in the world, and that either he or I, or both of us, must have been bewitched. I am really very sorry for him sometimes; I do make him so unhappy; and sometimes I am sorry for myself. But there, the whole thing is beyond my comprehension. If I could alter myself or alter Neville, things would be more comfortable and less unpleasantly exciting.” And here Edna laughed again, and then stifled another yawn; and this time Bessie declared she would not stop a moment longer. Christine would be asleep.

“Well, perhaps I should only talk nonsense if you remained, and I can see you are easily shocked, so I will allow you to wish me good-night.” But, to Bessie’s surprise, Edna kissed her affectionately.

“You have been a Good Samaritan to me,” she said quietly, “and I am really very grateful.[35]” And Bessie withdrew, touched by the unexpected caress.

“What a strange mixture she is!” she thought, as she softly closed the door. “I think she must have been badly brought up; perhaps her mother has spoiled her. I fancy she is affectionate by nature, but she is worldly, and cares too much for pleasure; anyhow, one cannot help being interested in her.” But here she broke off abruptly as she passed a half-opened door, and a voice from within summoned her.

“Oh, Hatty, you naughty child, are you awake? Do you know it is nearly twelve o’clock?”

“What does that matter?” returned Hatty fretfully, as Bessie groped her way carefully toward the bed. “I could not sleep until you had said good-night to me. I suppose you had forgotten me; you never thought I was lying here waiting for you, while you were talking to Miss Sefton.”

“Now, Hatty, I hope you are not going to be tiresome;” and Bessie’s voice was a little weary; and then she relented, and said gently, “You know I never forget you, Hatty dear.”

“No, of course not,” returned the other eagerly. “I did not mean to be cross. Put your head down beside me on the pillow, Bessie darling, for I know you are just as tired as possible. You don’t mind[36] stopping with me for a few minutes, do you? for I have not spoken to you for three weeks.”

“No, I am not so tired as all that, and I am quite comfortable,” as a thin, soft cheek laid itself against her’s in the darkness. “What has gone wrong, Hatty dear? for I know by your tone you have been making yourself miserable about something. You have wanted me back to scold you into cheerfulness.”

“I have wanted you dreadfully,” sighed Hatty. “Mother and Christine have been very kind, but they don’t help me as you do, and Tom teases me dreadfully. What do you think he said yesterday to mother? I was in the room and heard him myself. He actually said, ‘I wonder my father allows you all to spoil Hatty as you do. You all give in to her, however cross and unreasonable she is, and so her temper gets worse every day.’”

“Well, you are very often cross, you know,” returned Bessie truthfully.

“Yes, but I try not to be,” replied Hatty, with a little sob. “Tom would have been cross too if his head and back had ached as mine were aching, but he always feels well and strong. I think it is cruel of him to say such things to mother, when he knows how much I have to suffer.”

“Tom did not mean to be unkind, Hatty; you[37] are always finding fault with the poor boy. It is difficult for a young man, who does not know what an ache means, nor what it is to wake up tired, to realize what real suffering all your little ailments cause you. Tom is really very kind and good-natured, only your sharp little speeches irritate him.”

“I am always irritating some one,” moaned Hatty. “I can’t think how any of you can love me. I often cry myself to sleep, to think how horrid and disagreeable I have been in the day. I make good resolutions then, but the next morning I am as bad as ever, and then I think it is no use trying any more. Last night Tom made me so unhappy that I could not say my prayers.”

“Poor little Hatty!”

“Yes, I know you are sorry for me; you are such a dear that I cannot be as cross with you as I am with Tom; but, Bessie, I wish you would comfort me a little; if you would only tell me that I am not so much to blame.”

“We have talked that over a great many times before. You know what I think, Hatty; you are not to blame for your weakness; that is a trial laid upon you; but you are to blame if that weakness is so impatiently borne that it leads you to sin.”

[38]“I am sure father thinks that I cannot help my irritability; he will never let Tom scold me if he is in the room.”

“That is because father is so kind, and he knows you have such a hard time of it, you poor child, and that makes us all so sorry for you; but, Hatty, you must not let all this love spoil you; we are patient with you because we know your weakness, but we cannot help you if you do not help yourself. Don’t you recollect what dear Mr. Robertson said in his sermon? that ‘harassed nerves must be striven against, as we strive against anything that hinders our daily growth in grace.’ He said people were more tolerant of this form of weakness than of any other, and yet it caused much misery in homes, and he went on to tell us that every irritable word left unspoken, every peevish complaint hushed, was as real a victory as though we had done some great thing. ‘If we must suffer,’ he said, ‘at least let us suffer quietly, and not spend our breath in fruitless complaint. People will avoid a fretful person as though they were plague-tainted; and why? because they trouble the very atmosphere round them, and no one can enjoy peace in their neighborhood.’”

“I am sure Mr. Robertson must have meant me, Bessie.”

“No, darling, no; I won’t have you exaggerate or[39] judge yourself too harshly. You are not always cross, or we should not be so fond of you. You make us sad sometimes, when you sit apart, brooding over some imaginary grievance; that is why father calls you Little Miss Much-Afraid.”

“Yes, you all laugh at me, but indeed the darkness is very real. Sometimes I wonder why I have been sent into the world, if I am not to be happy myself, nor to make other people happy. You are like a sunbeam yourself, Bessie, and so you hardly understand what I mean.”

“Oh, yes, I do; but I never see any good in putting questions that we cannot answer; only I am quite sure you have your duty to do, quite as much as I have mine, only you have not found it out.”

“Perhaps I am the thorn in the flesh to discipline you all into patience,” returned Hatty quaintly, for she was not without humor.

“Very well, then, my thorn; fulfil your mission,” returned Bessie, kissing her. “But I cannot keep awake and speak words of wisdom any longer.” And she scrambled over the bed, and with another cheerful “good-night,” vanished; but Hatty’s troubled thoughts were lulled by sisterly sympathy, and she soon slept peacefully. Late as it was before Bessie laid her weary head on the pillow beside her sleeping sister, it was long before her eyes closed[40] and she sunk into utter forgetfulness. Her mind seemed crowded with vague images and disconnected thoughts. Recollections of the hours spent in Sheen Valley, the weird effect of the dusky figures passing and repassing in the dim, uncertain light, the faint streaks of light across the snow, the dull winter sky, the eager welcome of the lonely girl, the long friendly talk ripening into budding intimacy, all passed vividly before her, followed by Hatty’s artless confession.

“Poor little thing!” thought Bessie compassionately, for there was a specially soft place in her heart for Hatty. She had always been her particular charge. All Hatty’s failures, her miserable derelictions of duty, her morbid self-accusations and nervous fancies, bred of a sickly body and over-anxious temperament, were breathed into Bessie’s sympathizing ear. Hatty’s feebleness borrowed strength and courage from Bessie’s vigorous counsels. She felt braced by mere contact with such a strong, healthy organization. She was always less fretful and impatient when Bessie was near; her cheery influence cleared away many a cloud that threatened to obscure Hatty’s horizon.

“Bear ye one another’s burdens,” was a command literally obeyed by Bessie in her unselfish devotion to Hatty, her self-sacrificing efforts to cheer and[41] rouse her; but she never could be made to understand that there was any merit in her conduct.

“I know Hatty is often cross, and ready to take offence,” she would say; “but I think we ought to make allowances for her. I don’t think we realize how much she has to bear—that she never feels well.”

“Oh, that is all very well,” Christine would answer, for she had a quick temper too, and would fire up after one of Hatty’s sarcastic little speeches; “but it is time Hatty learned self-control. I dare say you are often tired after your Sunday class, but no one hears a cross word from you.”

“Oh, I keep it all in,” Bessie returned, laughing. “But I dare say I feel cross all the same. I don’t think any of us can guess what it must be to wake depressed and languid every morning. A louder voice than usual does not make our heads ache, yet I have seen Hatty wince with pain when Tom indulged in one of his laughs.”

“Yes, I know,” replied Christine, only half convinced by this. “Of course it is very trying, but Hatty must be used to it by this time, for she has never been strong from a baby; and yet she is always bemoaning herself, as though it were something fresh.”

“It is not easy to get used to this sort of trouble,[42]” answered Bessie, rather sadly. “And I must say I always feel very sorry for Hatty,” and so the conversation closed.

But in her heart Bessie said: “It is all very well to preach patience, and I for one am always preaching it to Hatty, but it is not so easy to practice it. Mother and Christine are always praising me for being so good tempered; but if one feels strong and well, and has a healthy appetite and good digestion, it is very easy to keep from being cross; but in other ways I am not half so good as Hatty; she is the purest, humblest little soul breathing.”

In spite of late hours, Bessie was downstairs the next morning at her usual time; she always presided at the breakfast-table. Since her eldest son’s death, Mrs. Lambert had lost much of her strength and energy, and though her husband refused to acknowledge her as an invalid, or to treat her as one, yet most of her duties had devolved upon Bessie, whose useful energy supplemented her mother’s failing powers.

Bessie had briefly hinted at her family sorrow; she was not one at any time to dwell upon her feelings, nor to indulge in morbid retrospection, but it was true that the loss of that dearly loved son and brother had clouded the bright home atmosphere. Mrs. Lambert had borne her trouble meekly, and had striven to comfort her husband who had broken[43] down under the sudden blow. She spoke little, even to her daughters, of the grief that was slowly consuming her; but as time went on, and Dr. Lambert recovered his cheerfulness, he noticed that his wife drooped and ailed more than usual; she had grown into slow quiet ways that seemed to point to failing strength.

“Bessie, your mother is not as young as she used to be,” he said abruptly, one morning, “She does not complain, but then she is not one of the complaining sort; she was always a quiet creature; but you girls must put your shoulders to the wheel, and spare her as much as possible.” And from that day Bessie had become her mother’s crutch.

It was a wonderful relief to the harassed mother when she found a confidante to whom she could pour out all her anxieties.

Dr. Lambert was not a rich man; his practice was large, but many of his patients were poor, and he had heavy expenses. The hilly roads and long distances obliged him to keep two horses. He had sent both his sons to Oxford, thinking a good education would be their best inheritance, and this had obliged him to curtail domestic expenses. He was a careful man, too, who looked forward to the future, and thought it his duty to lay aside a yearly sum to make provision for his wife and children.

[44]“I have only one son now, and Hatty will always be a care, poor child,” he said more than once.

So, though there was always a liberal table kept in the doctor’s house, it being Dr. Lambert’s theory that growing girls needed plenty of nourishing food, the young people were taught economy in every other matter. The girls dressed simply and made their own gowns. Carpets and furniture grew the worse for wear, and were not always replaced at once. Tom grumbled sometimes when one of his Oxford friends came to dinner. He and Christine used to bewail the shabby covers in the drawing-room.

“It is such a pretty room if it were only furbished off a bit,” Tom said once. “Why don’t you girls coax the governor to let you do it up?” Tom never used the word governor unless he was in a grumbling mood, for he knew how his father hated it.

“I don’t think father can afford anything this year, Tom,” Bessie returned, in her fearless way. “Why do you ask your grand friends if you think they will look down on us? We don’t pretend to be rich people. They will find the chairs very comfortable if they will condescend to sit on them, and the tables as strong as other people’s tables; and though the carpet is a little faded, there are no holes to trip your friends up.”

[45]“Oh, shut up, Betty!” returned Tom, restored to good humor by her honest sarcasm. “Ferguson will come if I ask him. I think he is a bit taken with old Chrissy.” And so ended the argument.

Breakfast was half over before Miss Sefton made her appearance; but her graceful apology for her tardiness was received by Dr. Lambert in the most indulgent manner. In spite of his love of punctuality, and his stringent rules for his household in this respect, he could not have found it in his heart to rebuke the pretty, smiling creature who told him so naïvely that early rising disagreed with her and put her out for the day.

“I tell mamma that I require a good deal of sleep, and, fortunately, she believes me,” finished Edna complacently.

Well, it was not like the doctor to hold his peace at this glaring opposition to his favorite theory, and yet, to Tom’s astonishment, he forebore to quote that threadbare and detestable adage, “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise”—proverbial and uncomfortable philosophy that Tom hated with all his foolish young heart. Tom,[47] in his budding manhood, often thought fit to set this domestic tyranny at defiance, and would argue at some length that his father was wrong in laying down rules for the younger generation.

“If my father likes to get up early, no one can find any fault with him for doing it,” Tom would say; “but he need not impose his venerable and benighted opinions upon us. Great men are not always wise; even intellectual veterans like Dr. Johnson, and others I can mention, if you only give me time, have their hallucinations, fads, fancies, and flummeries. For example, every one speaks of Dr. Johnson with respect; no one hints that he had a bee in his bonnet, and yet a man who could make a big hole for a cat and a little one for a kitten—was it Johnson or Newton who did that?—must have had a screw loose somewhere. And so it is with my father; early rising is his hobby—his pet theory—the keystone that binds the structure of health together. Well, it is a respectable theory, but my father need not expect an enlightened and progressive generation to subscribe to it. The early hours of the morning are not good for men and mice, only for birds and bricklayers, and worms weary of existence.”

Tom looked on, secretly amused, as his father smiled indulgently at Miss Sefton’s confession of indolence. He asked her how she had slept, and[48] made room for her beside him, and then questioned her about her intended journey, and finally arranged to drive her to the station before he went on his usual round.

An hour afterward the whole family collected in the hall to see Miss Sefton off. Edna bid them good-bye in her easy, friendly fashion, but as she took Bessie’s hand, she said:

“Good-bye, dear. I have an idea that we shall soon meet again. I shall not let you forget me;” and then she put up her face to be kissed.

“I am not likely to forget you,” thought Bessie, as Edna waved her little gloved hand to them all; “one could soon get fond of her.”

“How nice it must be to be rich,” sighed Christine, who was standing beside Bessie. “Miss Sefton is very little older than we are, and yet she has lovely diamond and emerald rings. Did you see her dressing bag? It was filled up so beautifully; its bottles silver mounted; it must have cost thirty guineas, at least. And then her furs; I should like to be in her place.”

“I should not envy Miss Sefton because she is rich,” retorted Hatty disdainfully. “I would rather change places with her because she is so strong and so pretty. I did like looking at her so much, and so did Tom. Didn’t you, Tom?”

[49]“I say, I wish you girls would shut up or clear off,” responded Tom crossly; for things felt a little flat this morning. “How is a fellow to work with all this chattering going on round him?”

“Why, you haven’t opened your books yet,” replied Hatty, in an aggrieved voice; but Bessie hastily interposed:

“Tom is quite right to want the room to himself. Come along, girls, let us go to mother in the morning-room; we might do some of our plain sewing, and then I can tell you about Aunt Charlotte. It is so long since we have been cosy together, and our needles will fly while we talk—eh, Hatty?”

“There are those night shirts to finish,” said Christine disconsolately; “they ought to have been done long ago, but Hatty was always saying her back ached when I wanted her help, and I could not get on with them by myself.”

“Never mind, we will all set to work vigorously,” and Bessie tripped away to find her work basket. The morning-room, as they called it, was a small room leading out of the drawing-room, with an old-fashioned bay window looking out on the garden.

There was a circular cushioned seat running round the bay, with a small table in the middle, and this was the place where the girls loved to sit and sew, while their tongues kept pace with their needles. When[50] Hatty’s back ached, or the light made her head throb with pain, she used to bring her low chair and leave the recess to Bessie and Christine.

The two younger girls went to school.

As Hatty brought her work (she was very skilful with the needle, and neither of her sisters could vie with her in delicate embroidery), she slipped a cold little hand into Bessie’s.

“It is so lovely to have you back, Betty, dear,” she whispered. “I woke quite happy this morning to know I should see you downstairs.”

“I think it is lovely to be home,” returned Bessie, with a beaming smile. “I am sure that is half the pleasure of going away—the coming back again. I don’t know how I should feel if I went to stay at any grand place; but it always seems to me now that home is the most delicious place in the world; it never looks shabby to me as it does to Tom; it is just homelike.”

Mrs. Lambert, who was sitting apart from the girls, busy with her weekly accounts, looked up at hearing her daughter’s speech.

“That is right, dear,” she said gently, “that is just how I like to hear you speak; it would grieve me if my girls were to grow discontented with their home, as some young ladies do.”

“Bessie is not like that, mother,” interposed Hatty eagerly.[51]

“No, Hatty, we know that, do we not? What do you think father said the other day, Bessie? He said, ‘I shall be glad when we get Bessie back, for the place does not seem like itself when she is away.’ That was a high compliment from father.”

“Indeed it was,” returned Bessie; and she blushed with pleasure. “Every one likes to be missed; but I hope you didn’t want me too much, mother.”

“No, dear; but, like father, I am glad to get you back again.” And the mother’s eyes rested fondly on the girl’s face. “Now you must not make me idle, for I have all these accounts to do, and some notes to write. Go on with your talking; it will not interrupt me.”

It spoke well for the Lambert girls that their mother’s presence never interfered with them; they talked as freely before her as other girls do in their parent’s absence. From children they had never been repressed nor unnaturally subdued; their childish preferences and tastes had been known and respected; no thoughtless criticism had wounded their susceptibility; imperceptibly and gently maternal advice had guided and restrained them.

“We tell mother everything, and she likes to hear it,” Ella and Katie would say to their school-fellows.

“We never have secrets from her,” Ella added.[52] “Katie did once, and mother was so hurt that she cried about it. Don’t you recollect, Katie?”

“Yes, and it is horrid of you to remind me,” returned Katie wrathfully, and she walked away in high dudgeon; the recollection was not a pleasant one. Katie’s soft heart had been pierced by her mother’s unfeigned grief and tender reproaches.

“You are the only one of all my little girls who ever hid anything from me. No, I am not angry with you, Katie, and I will kiss you as much as you like,” for Katie’s arms were round her neck in a moment; “but you have made mother cry, because you do not love her as she does you.”

“Mother shall never cry again on my account,” thought Katie; and, strange to say, the tendency to secretiveness in the child’s nature seemed cured from that day. Katie ever afterward confessed her misdemeanors and the accidents that happen to the best-regulated children with a frankness that bordered on bluntness.

“I have done it, mother,” she would say, “but somehow I don’t feel a bit sorry. I rather liked hurting Ella’s feelings; it seemed to serve her right.”

“Perhaps when we have talked about it a little you will feel sorry,” her mother would reply quietly; “but I have no time for talking just now.”

Mrs. Lambert was always very busy; on these occasions[53] she never found time for a heated and angry discussion. When Katie’s hot cheeks had cooled a little, and her childish wrath had evaporated, she would quietly argue the point with her. It was an odd thing that Katie generally apologized of her own accord afterward—generally owned herself the offender.

“Somehow you make things look different, mother,” she would say, “I can’t think why they all seem topsy-turvy to me.”

“When you are older I will lend you my spectacles,” her mother returned, smiling. “Now run and kiss Ella, and pray don’t forget next time that she is two years older; it can’t possibly be a younger sister’s duty to contradict her on every occasion.”

It was in this way that Mrs. Lambert had influenced her children, and she had reaped a rich harvest for her painstaking, patient labors with them, in the freely bestowed love and confidence with which her grown-up daughters regarded her. Now, as she sat apart, the sound of their fresh young voices was the sweetest music to her; not for worlds would she have allowed her own inward sadness to damp their spirits, but more than once the pen rested in her hand, and her attention wandered.

Outside the wintry sun was streaming on the leafless[54] trees and snowy lawns; some thrushes and sparrows were bathing in the pan of water that Katie had placed there that morning.

“Let us go for a long walk this afternoon,” Christine was saying, “through the Coombe Woods, and round by Summerford, and down by the quarry.”

“Even Bessie forgets that it will be Frank’s birthday to-morrow,” thought Mrs. Lambert. “My darling boy, I wonder if he remembers it there; if the angels tell him that his mother is thinking of him. That is just what one longs to know—if they remember;” and then she sighed, and pushed her papers aside, and no one saw the sadness of her face as she went out. Meanwhile Bessie was relating how she had spent the last three weeks.

“I can’t think how you could endure it,” observed Christine, as soon as she had finished. “Aunt Charlotte is very nice, of course; she is father’s sister, and we ought to think so; but she leads such a dull life, and then Cronyhurst is such an ugly village.”

“It is not dull to her, but then you see it is her life. People look on their own lives with such different eyes. Yes, it was very quiet at Cronyhurst; the roads were too bad for walking, and we had a great deal of snow; but we worked and talked, and[55] sometimes I read aloud, and so the days were not so long after all.”

“I should have come home at the end of a week,” returned Christine; “three weeks at Cronyhurst in the winter is too dreadful. It was real self-sacrifice on your part, Bessie; even father said so; he declared it was too bad of Aunt Charlotte to ask you at such a season of the year.”

“I don’t see that. Aunt Charlotte liked having me, and I was very willing to stay with her, and we had such nice talks. I don’t see that she is to be pitied at all. She has never married, and she lives alone, but she is perfectly contented with her life. She has her garden and her chickens, and her poor people. We used to go into some of the cottages when the weather allowed us to go out, and all the people seemed so pleased to see her. Aunt Charlotte is a good woman, and good people are generally happy. I know what Tom says about old maids,” continued Bessie presently, “but that is all nonsense. Aunt Charlotte says she is far better off as she is than many married people she knows. ‘Married people may double their pleasures,’ as folks say, ‘but they treble their cares, too,’ I have heard her remark; ‘and there is a great deal to be said in favor of freedom. When there is no one to praise there is no one to blame, and if there is no one to love there is no one[56] to lose, and I have always been content myself with single blessedness.’ Do you remember poor Uncle Joe’s saying, ‘The mare that goes in single harness does not get so many kicks?’”

“Yes, I know Aunt Charlotte’s way of talking; but I dare say no one wanted to marry her, so she makes the best of her circumstances.”

Bessie could not help laughing at Christine’s bluntness.

“Well, you are right, Chrissy; but Aunt Charlotte is not the least ashamed of the fact. She told me once that no one had ever fallen in love with her, ‘I could not expect them to do so,’ she remarked candidly. ‘As a girl I was plain featured, and so shy and awkward that your Uncle Joe used to tell me that I was the only ugly duckling that would never turn into a swan.’”

“What a shame of Uncle Joe!”

“I don’t think Aunt Charlotte took it much to heart. She says her hard life and many troubles drove all nonsense thoughts out of her head. Why, grandmamma was ill eight years, you know, and Aunt Charlotte nursed her all that time. I am sure when she used to come to my bedside of a night, and tuck me up with a motherly kiss, I used to think her face looked almost beautiful, it was so full of kindness. Somehow I fancy when I am old,” added[57] Bessie pensively, “I shall not care so much about my looks nor my wrinkles, if people will only think I am a comfortable, kind-hearted sort of a person.”

“You will be the dearest old lady in the world,” returned Hatty, dropping her work with an adoring look at her Betty. “You are cosier than other people now, so you are sure to be nicer than ever when you are old. No wonder Aunt Charlotte loved to have you.”

“What a little flatterer you are, Hatty! It is a comfort that I don’t grow vain. Do you know, I think Aunt Charlotte taught me a great deal. When you get over her little mannerisms and odd ways, you soon find out what a good woman she really is. She is always thinking of other people; what she can do to lighten their burdens; and little things give her so much pleasure. She says the first violet she picks in the hedgerow, or the sight of a pair of thrushes building their nest in the acacia tree, makes her feel as happy as a child; ‘for in spring,’ she said once, ‘all the world is full of young life, and the buds are bursting into flowers, and they remind me that one day I shall be young and beautiful too.’”

“I think I should like to go and stay with Aunt Charlotte,” observed Hatty, “if you think she would care to have me.”

“I am sure she would, dear. Aunt Charlotte loves[58] to take care of people. You most go in the summer, Hatty; the cottage is so pretty then, and you could be out in the garden or in the lanes all day. June is the best month, for they will be making hay in the meadows, and you could sit on the porch and smell the roses, and watch Aunt Charlotte’s bees filling their honey bags. It is just the place for you, Hatty—so still and quiet.”

This sort of talk lasted most of the morning, until Ella and Katie returned from school, and Tom sauntered into the room, flushed with his mental labors, and ready to seek relaxation in his sisters’ company.

Bessie left the room and went in search of her mother; when she returned, a quarter of an hour later, she found Tom sulky and Hatty in tears.

“It is no use trying to keep the peace,” observed Christine, in a vexed tone. “Tom will tease Hatty, and then she gets cross, and there is no silencing either of them.”

“Come with me, Hatty dear, and help me put my room in order. I have to finish my unpacking,” said Bessie soothingly. “You have been working too long, and so has Tom. I shall leave him to you, Chrissy.” And as Hatty only moaned a little in her handkerchief, Bessie took the work forcibly away, and then coaxed her out of the room.

“Why is Tom so horrid to me?” sobbed Hatty[59] “I don’t believe he loves me a bit. I was having such a happy morning, and he came in and spoiled all.”

“Never mind about Tom. No one cares for his teasing, except you, Hatty. I would not let him see you mind everything he chooses to say. He will only think you a baby for crying. Now, do help me arrange this drawer, for dinner will be ready in a quarter of an hour, and the floor is just strewn with clothes. If it makes your head ache to stoop, I will just hand you the things; but no one else can put them away so tidily.”

The artful little bait took. Of all things Hatty loved to be of use to any one. In another moment she had dried her eyes and set to work, her miserable little face grew cheerful, and Tom’s sneering speeches were forgotten.

“Why, I do believe that is Hatty laughing!” exclaimed Christine, as the dinner-bell sounded, and she passed the door with her mother. “It is splendid, the way Bessie manages Hatty. I wish some of us could learn the art, for all this wrangling with Tom is so tiresome.”

“Bessie never loses patience with her,” returned her mother; “never lets her feel that she is a trouble. I think you will find that is the secret of Bessie’s influence. Your father and I are often grateful to[60] her. ‘What would that poor child do without her?’ as your father often says; and I do believe her health would often suffer if Bessie did not turn her thoughts away from the things that were fretting her.[61]”

One day, about three months after her adventure in the Sheen Valley, Bessie was climbing up the steep road that led to the Lamberts’ house. It was a lovely spring afternoon, and Bessie was enjoying the fresh breeze that was blowing up from the bay. Cliffe was steeped in sunshine, the air was permeated with the fragrance of lilac blended with the faint odors of the pink and white May blossoms. The flower-sellers’ baskets in the town were full of dark-red wallflowers and lovely hyacinths. The birds were singing nursery lullabies over their nests in the Coombe Woods, and even the sleek donkeys, dragging up some invalids from the Parade in their trim little chairs, seemed to toil more willingly in the sweet spring sunshine.

“How happy the world looks to-day!” said Bessie to herself; and perhaps this pleasant thought was reflected in her face, for more than one passer-by glanced at her half enviously. Bessie did not notice them; her soft gray eyes were fixed on the blue sky[62] above her, or on the glimpses of water between the houses. Just before she turned into the avenue that led to the house, she stopped to admire the view. She was at the summit of the hill now; below her lay the town; where she stood she could look over the housetops to the shining water of the bay, with its rocky island in the middle. Bessie always called it the bay, but in reality it resembled a lake, it was so landlocked, so closed in by the opposite shore, except in one part; but the smooth expanse of water, shining in the sunlight, lacked the freedom and wild freshness of the open sea, though Bessie would look intently to a distant part, where nothing, as she knew, came between her and the Atlantic. “If we only went far enough, we should reach America; that gives one the idea of freedom and vastness,” she thought.

Bessie held the idea that Cliffe-on-Sea was one of the prettiest places in England, and it was certainly not devoid of picturesqueness.

The houses were mostly built of stone, hewn out of the quarry, and were perched up in surprisingly unexpected places—some of them built against the rock, their windows commanding extensive views of the surrounding country. The quarry was near the Lamberts’ house, and the Coombe Woods stretched above it for miles. Bessie’s favorite walk was the[63] long road that skirted the woods. On one side were the hanging woods, and on the other the bay. Through the trees one could see the gleam of water, and on summer evenings the Lambert girls would often sit on the rocks with their work and books, preferring the peaceful stillness to the Parade crowded with strangers listening to the band. When their mother or Tom was with them, they would often linger until the stars came out or the moon rose. How glorious the water looked then, bathed in silvery radiance, like an enchanted lake! How dark and sombre the woods! What strange shadows used to lurk among the trees! Hatty would creep to Bessie’s side, as they walked, especially if Tom indulged in one of his ghost stories.

“What is the use of repeating all that rubbish, Tom?” Bessie would say, in her sturdy fashion. “Do you think any one would hear us if we sung one of our glees? That will be better than talking about headless bogies to scare Hatty. I like singing by moonlight.”

Well, they were just healthy, happy young people, who knew how to make the most of small pleasures. “Every one could have air and sunshine and good spirits,” Bessie used to say, “if they ailed nothing and kept their consciences in good order. Laughing cost nothing, and talking was the cheapest amusement she knew.”

[64]“That depends,” replied her father oracularly, on overhearing this remark. “Words are dear enough sometimes. You are a wise woman, Bessie, but you have plenty to learn yet. We all have to buy experience ourselves. I don’t want you to get your wisdom second-hand; second-hand articles don’t last; so laugh away, child, as long as you can.”

“I love spring,” thought Bessie, as she walked on. “I always did like bright things best. I wonder why I feel so hopeful to-day, just as though I expected something pleasant to happen. Nothing ever does happen, as Chriss says. Just a letter from Tom, telling us his news, or an invitation to tea with a neighbor, or perhaps a drive out into the country with father. Well, they are not big things, but they are pleasant, for all that. I do like a long talk with father, when he has no troublesome case on his mind, and can give me all his attention. I think there is no treat like it; but I mean Hatty to have the next turn. She has been good lately; but she looks pale and dwindled. I am not half comfortable about her.” And here Bessie broke off her cogitations, for at that moment Katie rushed out of the house and began dancing up and down, waving a letter over her head.

“What a time you have been!” cried the child excitedly. “I have been watching for you for half an hour. Here is a letter for your own self, and it is[65] not from Aunt Charlotte nor Uncle Charles, nor any old fogy at all.”

“Give it to me, please,” returned Bessie. “I suppose it is from Tom, though why you should make such a fuss about it, as though no one ever got a letter, passes my comprehension. No, it is from Miss Sefton; I recognize her handwriting;” which was true, as Bessie had received a note from Edna a few days after she had left them, conveying her own and her mother’s thanks for the kind hospitality she had received.

“Of course it is from Miss Sefton; there’s the Oatlands post-mark. Ella and I were trying to guess what was in it; we thought that perhaps, as Mrs. Sefton is so rich, she might have sent you a present for being so kind to her daughter; that was Ella’s idea. Do open it quickly, Bessie; what is the use of looking at the envelope?”

“I am afraid I can’t satisfy your curiosity just yet, Kitty. Hatty is waiting for the silks I have been matching, and mother will want to know how old Mrs. Wright is. Duty before pleasure,” finished Bessie, with good-humored peremptoriness, as she marched off in the direction of the morning-room.

“Bessie is getting dreadfully old-maidish,” observed Katie, in a sulky voice. “She never used to be so proper. I suppose she thinks it is none of my business.”

[66]When Bessie had got through her list of commissions she sat down to enjoy her letter quietly, but before she had read many lines her color rose, and a half-stifled exclamation of surprise came from her lips; but, in spite of Hatty’s curious questions, she read steadily to the end, and then laid the letter on her mother’s lap.

“Oh, mother, do let me hear it,” implored Hatty, with the persistence of a spoiled child. “I am sure there is something splendid about Bessie, and I do hate mysteries.”