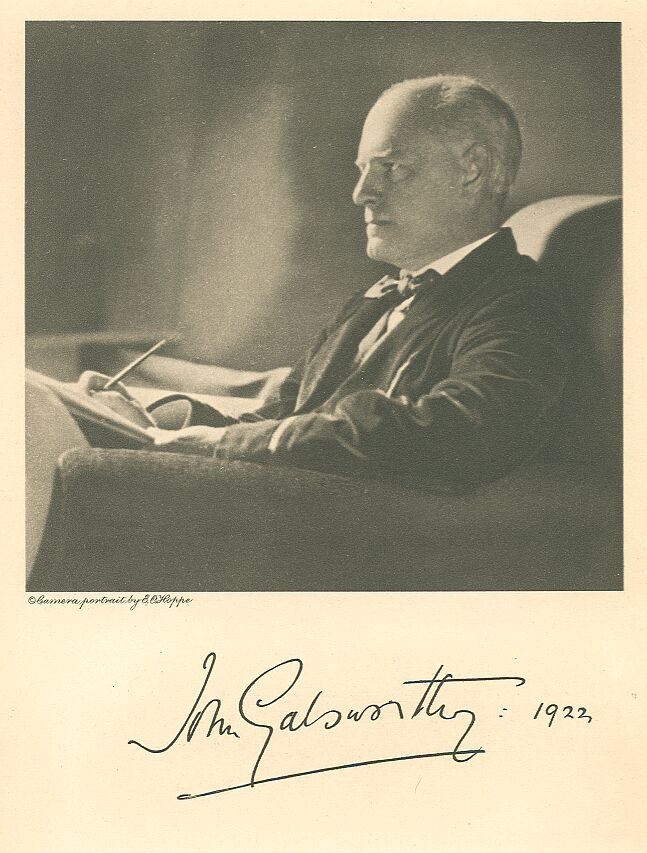

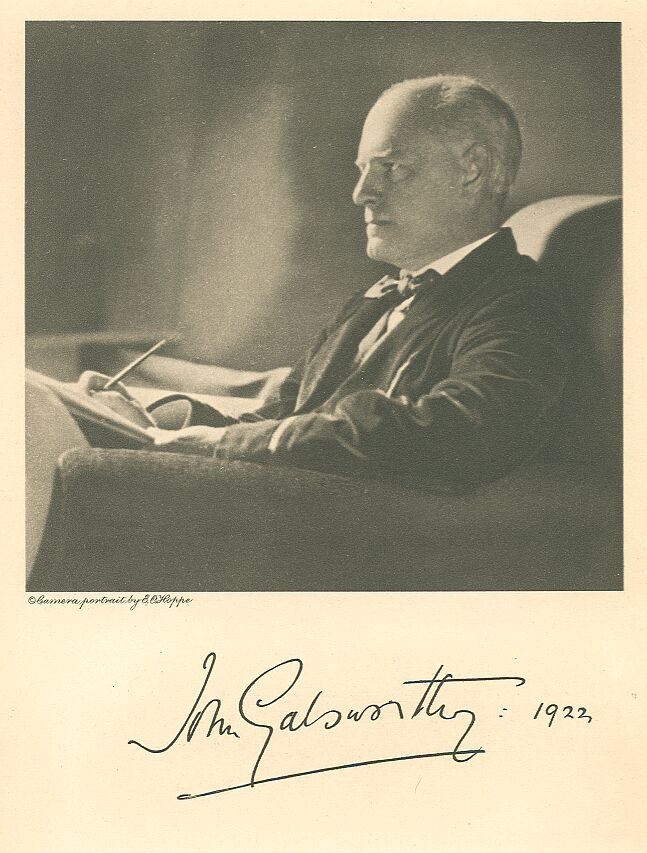

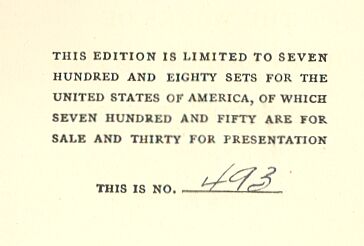

Title: The Works of John Galsworthy

Author: John Galsworthy

Editor: David Widger

Release date: May 11, 2009 [eBook #28760]

Most recently updated: November 3, 2023

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

| THE FIRST SERIES: | The Silver Box | Joy | Strife |

| THE SECOND SERIES: | The Eldest Son | Little Dream | Justice |

| THE THIRD SERIES: | The Fugitive | The Pigeon | The Mob |

| THE FOURTH SERIES: | A Bit O'Love | The Foundations | The Skin Game |

| THE FIFTH SERIES: | A Family Man | Loyalties | Windows |

| THE SIXTH SERIES: | The First and Last | The Little Man | Four Short Plays |

CHAPTER I—'AT HOME' AT OLD JOLYON'S

CHAPTER II—OLD JOLYON GOES TO THE OPERA

CHAPTER III—DINNER AT SWITHIN'S

CHAPTER IV—PROJECTION OF THE HOUSE

CHAPTER VII—OLD JOLYON'S PECCADILLO

CHAPTER VIII—PLANS OF THE HOUSE

CHAPTER I—PROGRESS OF THE HOUSE

CHAPTER III—DRIVE WITH SWITHIN

CHAPTER IV—JAMES GOES TO SEE FOR HIMSELF

CHAPTER V—SOAMES AND BOSINNEY CORRESPOND

CHAPTER VI—OLD JOLYON AT THE ZOO

CHAPTER VII—AFTERNOON AT TIMOTHY'S

CHAPTER IX—EVENING AT RICHMOND

CHAPTER X—DIAGNOSIS OF A FORSYTE

CHAPTER XII—JUNE PAYS SOME CALLS

CHAPTER XIII—PERFECTION OF THE HOUSE

CHAPTER XIV—SOAMES SITS ON THE STAIRS

CHAPTER I—MRS. MACANDER'S EVIDENCE

CHAPTER III—MEETING AT THE BOTANICAL

CHAPTER IV—VOYAGE INTO THE INFERNO

CHAPTER VI—SOAMES BREAKS THE NEWS

CHAPTER VIII—BOSINNEY'S DEPARTURE

CHAPTER II—EXIT A MAN OF THE WORLD

CHAPTER III—SOAMES PREPARES TO TAKE STEPS

CHAPTER VI—NO-LONGER-YOUNG JOLYON AT HOME

CHAPTER VII—THE COLT AND THE FILLY

CHAPTER VIII—JOLYON PROSECUTES TRUSTEESHIP

CHAPTER X—SOAMES ENTERTAINS THE FUTURE

CHAPTER XI—AND VISITS THE PAST

CHAPTER XII—ON FORSYTE 'CHANGE

CHAPTER XIII—JOLYON FINDS OUT WHERE HE IS

CHAPTER XIV—SOAMES DISCOVERS WHAT HE WANTS

CHAPTER I—THE THIRD GENERATION

CHAPTER II—SOAMES PUTS IT TO THE TOUCH

CHAPTER IV—WHERE FORSYTES FEAR TO TREAD

CHAPTER V—JOLLY SITS IN JUDGMENT

CHAPTER VI—JOLYON IN TWO MINDS

CHAPTER VII—DARTIE VERSUS DARTIE

CHAPTER X—DEATH OF THE DOG BALTHASAR

CHAPTER XI—TIMOTHY STAYS THE ROT

CHAPTER XII—PROGRESS OF THE CHASE

CHAPTER XIII—'HERE WE ARE AGAIN!'

CHAPTER XI—SUSPENDED ANIMATION

CHAPTER XII—BIRTH OF A FORSYTE

VIII.—THE BIT BETWEEN THE TEETH

TO MY WIFE:

I DEDICATE THE FORSYTE SAGA IN ITS ENTIRETY,

BELIEVING IT TO BE OF ALL MY WORKS THE LEAST

UNWORTHY OF ONE WITHOUT WHOSE ENCOURAGEMENT,

SYMPATHY AND CRITICISM I COULD NEVER HAVE

BECOME EVEN SUCH A WRITER AS I AM.

“The Forsyte Saga” was the title originally destined for that part of it which is called “The Man of Property”; and to adopt it for the collected chronicles of the Forsyte family has indulged the Forsytean tenacity that is in all of us. The word Saga might be objected to on the ground that it connotes the heroic and that there is little heroism in these pages. But it is used with a suitable irony; and, after all, this long tale, though it may deal with folk in frock coats, furbelows, and a gilt-edged period, is not devoid of the essential heat of conflict. Discounting for the gigantic stature and blood-thirstiness of old days, as they have come down to us in fairy-tale and legend, the folk of the old Sagas were Forsytes, assuredly, in their possessive instincts, and as little proof against the inroads of beauty and passion as Swithin, Soames, or even Young Jolyon. And if heroic figures, in days that never were, seem to startle out from their surroundings in fashion unbecoming to a Forsyte of the Victorian era, we may be sure that tribal instinct was even then the prime force, and that “family” and the sense of home and property counted as they do to this day, for all the recent efforts to “talk them out.”

So many people have written and claimed that their families were the originals of the Forsytes that one has been almost encouraged to believe in the typicality of an imagined species. Manners change and modes evolve, and “Timothy's on the Bayswater Road” becomes a nest of the unbelievable in all except essentials; we shall not look upon its like again, nor perhaps on such a one as James or Old Jolyon. And yet the figures of Insurance Societies and the utterances of Judges reassure us daily that our earthly paradise is still a rich preserve, where the wild raiders, Beauty and Passion, come stealing in, filching security from beneath our noses. As surely as a dog will bark at a brass band, so will the essential Soames in human nature ever rise up uneasily against the dissolution which hovers round the folds of ownership.

“Let the dead Past bury its dead” would be a better saying if the Past ever died. The persistence of the Past is one of those tragi-comic blessings which each new age denies, coming cocksure on to the stage to mouth its claim to a perfect novelty.

But no Age is so new as that! Human Nature, under its changing pretensions and clothes, is and ever will be very much of a Forsyte, and might, after all, be a much worse animal.

Looking back on the Victorian era, whose ripeness, decline, and 'fall-of' is in some sort pictured in “The Forsyte Saga,” we see now that we have but jumped out of a frying-pan into a fire. It would be difficult to substantiate a claim that the case of England was better in 1913 than it was in 1886, when the Forsytes assembled at Old Jolyon's to celebrate the engagement of June to Philip Bosinney. And in 1920, when again the clan gathered to bless the marriage of Fleur with Michael Mont, the state of England is as surely too molten and bankrupt as in the eighties it was too congealed and low-percented. If these chronicles had been a really scientific study of transition one would have dwelt probably on such factors as the invention of bicycle, motor-car, and flying-machine; the arrival of a cheap Press; the decline of country life and increase of the towns; the birth of the Cinema. Men are, in fact, quite unable to control their own inventions; they at best develop adaptability to the new conditions those inventions create.

But this long tale is no scientific study of a period; it is rather an intimate incarnation of the disturbance that Beauty effects in the lives of men.

The figure of Irene, never, as the reader may possibly have observed, present, except through the senses of other characters, is a concretion of disturbing Beauty impinging on a possessive world.

One has noticed that readers, as they wade on through the salt waters of the Saga, are inclined more and more to pity Soames, and to think that in doing so they are in revolt against the mood of his creator. Far from it! He, too, pities Soames, the tragedy of whose life is the very simple, uncontrollable tragedy of being unlovable, without quite a thick enough skin to be thoroughly unconscious of the fact. Not even Fleur loves Soames as he feels he ought to be loved. But in pitying Soames, readers incline, perhaps, to animus against Irene: After all, they think, he wasn't a bad fellow, it wasn't his fault; she ought to have forgiven him, and so on!

And, taking sides, they lose perception of the simple truth, which underlies the whole story, that where sex attraction is utterly and definitely lacking in one partner to a union, no amount of pity, or reason, or duty, or what not, can overcome a repulsion implicit in Nature. Whether it ought to, or no, is beside the point; because in fact it never does. And where Irene seems hard and cruel, as in the Bois de Boulogne, or the Goupenor Gallery, she is but wisely realistic—knowing that the least concession is the inch which precedes the impossible, the repulsive ell.

A criticism one might pass on the last phase of the Saga is the complaint that Irene and Jolyon those rebels against property—claim spiritual property in their son Jon. But it would be hypercriticism, as the tale is told. No father and mother could have let the boy marry Fleur without knowledge of the facts; and the facts determine Jon, not the persuasion of his parents. Moreover, Jolyon's persuasion is not on his own account, but on Irene's, and Irene's persuasion becomes a reiterated: “Don't think of me, think of yourself!” That Jon, knowing the facts, can realise his mother's feelings, will hardly with justice be held proof that she is, after all, a Forsyte.

But though the impingement of Beauty and the claims of Freedom on a possessive world are the main prepossessions of the Forsyte Saga, it cannot be absolved from the charge of embalming the upper-middle class. As the old Egyptians placed around their mummies the necessaries of a future existence, so I have endeavoured to lay beside the figures of Aunts Ann and Juley and Hester, of Timothy and Swithin, of Old Jolyon and James, and of their sons, that which shall guarantee them a little life here-after, a little balm in the hurried Gilead of a dissolving “Progress.”

If the upper-middle class, with other classes, is destined to “move on” into amorphism, here, pickled in these pages, it lies under glass for strollers in the wide and ill-arranged museum of Letters. Here it rests, preserved in its own juice: The Sense of Property. 1922.

“........You will answer

The slaves are ours.....”

—Merchant of Venice.

Those privileged to be present at a family festival of the Forsytes have seen that charming and instructive sight—an upper middle-class family in full plumage. But whosoever of these favoured persons has possessed the gift of psychological analysis (a talent without monetary value and properly ignored by the Forsytes), has witnessed a spectacle, not only delightful in itself, but illustrative of an obscure human problem. In plainer words, he has gleaned from a gathering of this family—no branch of which had a liking for the other, between no three members of whom existed anything worthy of the name of sympathy—evidence of that mysterious concrete tenacity which renders a family so formidable a unit of society, so clear a reproduction of society in miniature. He has been admitted to a vision of the dim roads of social progress, has understood something of patriarchal life, of the swarmings of savage hordes, of the rise and fall of nations. He is like one who, having watched a tree grow from its planting—a paragon of tenacity, insulation, and success, amidst the deaths of a hundred other plants less fibrous, sappy, and persistent—one day will see it flourishing with bland, full foliage, in an almost repugnant prosperity, at the summit of its efflorescence.

On June 15, eighteen eighty-six, about four of the afternoon, the observer who chanced to be present at the house of old Jolyon Forsyte in Stanhope Gate, might have seen the highest efflorescence of the Forsytes.

This was the occasion of an 'at home' to celebrate the engagement of Miss June Forsyte, old Jolyon's granddaughter, to Mr. Philip Bosinney. In the bravery of light gloves, buff waistcoats, feathers and frocks, the family were present, even Aunt Ann, who now but seldom left the corner of her brother Timothy's green drawing-room, where, under the aegis of a plume of dyed pampas grass in a light blue vase, she sat all day reading and knitting, surrounded by the effigies of three generations of Forsytes. Even Aunt Ann was there; her inflexible back, and the dignity of her calm old face personifying the rigid possessiveness of the family idea.

When a Forsyte was engaged, married, or born, the Forsytes were present; when a Forsyte died—but no Forsyte had as yet died; they did not die; death being contrary to their principles, they took precautions against it, the instinctive precautions of highly vitalized persons who resent encroachments on their property.

About the Forsytes mingling that day with the crowd of other guests, there was a more than ordinarily groomed look, an alert, inquisitive assurance, a brilliant respectability, as though they were attired in defiance of something. The habitual sniff on the face of Soames Forsyte had spread through their ranks; they were on their guard.

The subconscious offensiveness of their attitude has constituted old Jolyon's 'home' the psychological moment of the family history, made it the prelude of their drama.

The Forsytes were resentful of something, not individually, but as a family; this resentment expressed itself in an added perfection of raiment, an exuberance of family cordiality, an exaggeration of family importance, and—the sniff. Danger—so indispensable in bringing out the fundamental quality of any society, group, or individual—was what the Forsytes scented; the premonition of danger put a burnish on their armour. For the first time, as a family, they appeared to have an instinct of being in contact, with some strange and unsafe thing.

Over against the piano a man of bulk and stature was wearing two waistcoats on his wide chest, two waistcoats and a ruby pin, instead of the single satin waistcoat and diamond pin of more usual occasions, and his shaven, square, old face, the colour of pale leather, with pale eyes, had its most dignified look, above his satin stock. This was Swithin Forsyte. Close to the window, where he could get more than his fair share of fresh air, the other twin, James—the fat and the lean of it, old Jolyon called these brothers—like the bulky Swithin, over six feet in height, but very lean, as though destined from his birth to strike a balance and maintain an average, brooded over the scene with his permanent stoop; his grey eyes had an air of fixed absorption in some secret worry, broken at intervals by a rapid, shifting scrutiny of surrounding facts; his cheeks, thinned by two parallel folds, and a long, clean-shaven upper lip, were framed within Dundreary whiskers. In his hands he turned and turned a piece of china. Not far off, listening to a lady in brown, his only son Soames, pale and well-shaved, dark-haired, rather bald, had poked his chin up sideways, carrying his nose with that aforesaid appearance of 'sniff,' as though despising an egg which he knew he could not digest. Behind him his cousin, the tall George, son of the fifth Forsyte, Roger, had a Quilpish look on his fleshy face, pondering one of his sardonic jests. Something inherent to the occasion had affected them all.

Seated in a row close to one another were three ladies—Aunts Ann, Hester (the two Forsyte maids), and Juley (short for Julia), who not in first youth had so far forgotten herself as to marry Septimus Small, a man of poor constitution. She had survived him for many years. With her elder and younger sister she lived now in the house of Timothy, her sixth and youngest brother, on the Bayswater Road. Each of these ladies held fans in their hands, and each with some touch of colour, some emphatic feather or brooch, testified to the solemnity of the opportunity.

In the centre of the room, under the chandelier, as became a host, stood the head of the family, old Jolyon himself. Eighty years of age, with his fine, white hair, his dome-like forehead, his little, dark grey eyes, and an immense white moustache, which drooped and spread below the level of his strong jaw, he had a patriarchal look, and in spite of lean cheeks and hollows at his temples, seemed master of perennial youth. He held himself extremely upright, and his shrewd, steady eyes had lost none of their clear shining. Thus he gave an impression of superiority to the doubts and dislikes of smaller men. Having had his own way for innumerable years, he had earned a prescriptive right to it. It would never have occurred to old Jolyon that it was necessary to wear a look of doubt or of defiance.

Between him and the four other brothers who were present, James, Swithin, Nicholas, and Roger, there was much difference, much similarity. In turn, each of these four brothers was very different from the other, yet they, too, were alike.

Through the varying features and expression of those five faces could be marked a certain steadfastness of chin, underlying surface distinctions, marking a racial stamp, too prehistoric to trace, too remote and permanent to discuss—the very hall-mark and guarantee of the family fortunes.

Among the younger generation, in the tall, bull-like George, in pallid strenuous Archibald, in young Nicholas with his sweet and tentative obstinacy, in the grave and foppishly determined Eustace, there was this same stamp—less meaningful perhaps, but unmistakable—a sign of something ineradicable in the family soul. At one time or another during the afternoon, all these faces, so dissimilar and so alike, had worn an expression of distrust, the object of which was undoubtedly the man whose acquaintance they were thus assembled to make. Philip Bosinney was known to be a young man without fortune, but Forsyte girls had become engaged to such before, and had actually married them. It was not altogether for this reason, therefore, that the minds of the Forsytes misgave them. They could not have explained the origin of a misgiving obscured by the mist of family gossip. A story was undoubtedly told that he had paid his duty call to Aunts Ann, Juley, and Hester, in a soft grey hat—a soft grey hat, not even a new one—a dusty thing with a shapeless crown. “So, extraordinary, my dear—so odd,” Aunt Hester, passing through the little, dark hall (she was rather short-sighted), had tried to 'shoo' it off a chair, taking it for a strange, disreputable cat—Tommy had such disgraceful friends! She was disturbed when it did not move.

Like an artist for ever seeking to discover the significant trifle which embodies the whole character of a scene, or place, or person, so those unconscious artists—the Forsytes had fastened by intuition on this hat; it was their significant trifle, the detail in which was embedded the meaning of the whole matter; for each had asked himself: “Come, now, should I have paid that visit in that hat?” and each had answered “No!” and some, with more imagination than others, had added: “It would never have come into my head!”

George, on hearing the story, grinned. The hat had obviously been worn as a practical joke! He himself was a connoisseur of such. “Very haughty!” he said, “the wild Buccaneer.”

And this mot, the 'Buccaneer,' was bandied from mouth to mouth, till it became the favourite mode of alluding to Bosinney.

Her aunts reproached June afterwards about the hat.

“We don't think you ought to let him, dear!” they had said.

June had answered in her imperious brisk way, like the little embodiment of will she was: “Oh! what does it matter? Phil never knows what he's got on!”

No one had credited an answer so outrageous. A man not to know what he had on? No, no! What indeed was this young man, who, in becoming engaged to June, old Jolyon's acknowledged heiress, had done so well for himself? He was an architect, not in itself a sufficient reason for wearing such a hat. None of the Forsytes happened to be architects, but one of them knew two architects who would never have worn such a hat upon a call of ceremony in the London season.

Dangerous—ah, dangerous! June, of course, had not seen this, but, though not yet nineteen, she was notorious. Had she not said to Mrs. Soames—who was always so beautifully dressed—that feathers were vulgar? Mrs. Soames had actually given up wearing feathers, so dreadfully downright was dear June!

These misgivings, this disapproval, and perfectly genuine distrust, did not prevent the Forsytes from gathering to old Jolyon's invitation. An 'At Home' at Stanhope Gate was a great rarity; none had been held for twelve years, not indeed, since old Mrs. Jolyon had died.

Never had there been so full an assembly, for, mysteriously united in spite of all their differences, they had taken arms against a common peril. Like cattle when a dog comes into the field, they stood head to head and shoulder to shoulder, prepared to run upon and trample the invader to death. They had come, too, no doubt, to get some notion of what sort of presents they would ultimately be expected to give; for though the question of wedding gifts was usually graduated in this way: 'What are you givin'. Nicholas is givin' spoons!'—so very much depended on the bridegroom. If he were sleek, well-brushed, prosperous-looking, it was more necessary to give him nice things; he would expect them. In the end each gave exactly what was right and proper, by a species of family adjustment arrived at as prices are arrived at on the Stock Exchange—the exact niceties being regulated at Timothy's commodious, red-brick residence in Bayswater, overlooking the Park, where dwelt Aunts Ann, Juley, and Hester.

The uneasiness of the Forsyte family has been justified by the simple mention of the hat. How impossible and wrong would it have been for any family, with the regard for appearances which should ever characterize the great upper middle-class, to feel otherwise than uneasy!

The author of the uneasiness stood talking to June by the further door; his curly hair had a rumpled appearance, as though he found what was going on around him unusual. He had an air, too, of having a joke all to himself. George, speaking aside to his brother, Eustace, said:

“Looks as if he might make a bolt of it—the dashing Buccaneer!”

This 'very singular-looking man,' as Mrs. Small afterwards called him, was of medium height and strong build, with a pale, brown face, a dust-coloured moustache, very prominent cheek-bones, and hollow checks. His forehead sloped back towards the crown of his head, and bulged out in bumps over the eyes, like foreheads seen in the Lion-house at the Zoo. He had sherry-coloured eyes, disconcertingly inattentive at times. Old Jolyon's coachman, after driving June and Bosinney to the theatre, had remarked to the butler:

“I dunno what to make of 'im. Looks to me for all the world like an 'alf-tame leopard.” And every now and then a Forsyte would come up, sidle round, and take a look at him.

June stood in front, fending off this idle curiosity—a little bit of a thing, as somebody once said, 'all hair and spirit,' with fearless blue eyes, a firm jaw, and a bright colour, whose face and body seemed too slender for her crown of red-gold hair.

A tall woman, with a beautiful figure, which some member of the family had once compared to a heathen goddess, stood looking at these two with a shadowy smile.

Her hands, gloved in French grey, were crossed one over the other, her grave, charming face held to one side, and the eyes of all men near were fastened on it. Her figure swayed, so balanced that the very air seemed to set it moving. There was warmth, but little colour, in her cheeks; her large, dark eyes were soft.

But it was at her lips—asking a question, giving an answer, with that shadowy smile—that men looked; they were sensitive lips, sensuous and sweet, and through them seemed to come warmth and perfume like the warmth and perfume of a flower.

The engaged couple thus scrutinized were unconscious of this passive goddess. It was Bosinney who first noticed her, and asked her name.

June took her lover up to the woman with the beautiful figure.

“Irene is my greatest chum,” she said: “Please be good friends, you two!”

At the little lady's command they all three smiled; and while they were smiling, Soames Forsyte, silently appearing from behind the woman with the beautiful figure, who was his wife, said:

“Ah! introduce me too!”

He was seldom, indeed, far from Irene's side at public functions, and even when separated by the exigencies of social intercourse, could be seen following her about with his eyes, in which were strange expressions of watchfulness and longing.

At the window his father, James, was still scrutinizing the marks on the piece of china.

“I wonder at Jolyon's allowing this engagement,” he said to Aunt Ann. “They tell me there's no chance of their getting married for years. This young Bosinney” (he made the word a dactyl in opposition to general usage of a short o) “has got nothing. When Winifred married Dartie, I made him bring every penny into settlement—lucky thing, too—they'd ha' had nothing by this time!”

Aunt Ann looked up from her velvet chair. Grey curls banded her forehead, curls that, unchanged for decades, had extinguished in the family all sense of time. She made no reply, for she rarely spoke, husbanding her aged voice; but to James, uneasy of conscience, her look was as good as an answer.

“Well,” he said, “I couldn't help Irene's having no money. Soames was in such a hurry; he got quite thin dancing attendance on her.”

Putting the bowl pettishly down on the piano, he let his eyes wander to the group by the door.

“It's my opinion,” he said unexpectedly, “that it's just as well as it is.”

Aunt Ann did not ask him to explain this strange utterance. She knew what he was thinking. If Irene had no money she would not be so foolish as to do anything wrong; for they said—they said—she had been asking for a separate room; but, of course, Soames had not....

James interrupted her reverie:

“But where,” he asked, “was Timothy? Hadn't he come with them?”

Through Aunt Ann's compressed lips a tender smile forced its way:

“No, he didn't think it wise, with so much of this diphtheria about; and he so liable to take things.”

James answered:

“Well, HE takes good care of himself. I can't afford to take the care of myself that he does.”

Nor was it easy to say which, of admiration, envy, or contempt, was dominant in that remark.

Timothy, indeed, was seldom seen. The baby of the family, a publisher by profession, he had some years before, when business was at full tide, scented out the stagnation which, indeed, had not yet come, but which ultimately, as all agreed, was bound to set in, and, selling his share in a firm engaged mainly in the production of religious books, had invested the quite conspicuous proceeds in three per cent. consols. By this act he had at once assumed an isolated position, no other Forsyte being content with less than four per cent. for his money; and this isolation had slowly and surely undermined a spirit perhaps better than commonly endowed with caution. He had become almost a myth—a kind of incarnation of security haunting the background of the Forsyte universe. He had never committed the imprudence of marrying, or encumbering himself in any way with children.

James resumed, tapping the piece of china:

“This isn't real old Worcester. I s'pose Jolyon's told you something about the young man. From all I can learn, he's got no business, no income, and no connection worth speaking of; but then, I know nothing—nobody tells me anything.”

Aunt Ann shook her head. Over her square-chinned, aquiline old face a trembling passed; the spidery fingers of her hands pressed against each other and interlaced, as though she were subtly recharging her will.

The eldest by some years of all the Forsytes, she held a peculiar position amongst them. Opportunists and egotists one and all—though not, indeed, more so than their neighbours—they quailed before her incorruptible figure, and, when opportunities were too strong, what could they do but avoid her!

Twisting his long, thin legs, James went on:

“Jolyon, he will have his own way. He's got no children”—and stopped, recollecting the continued existence of old Jolyon's son, young Jolyon, June's father, who had made such a mess of it, and done for himself by deserting his wife and child and running away with that foreign governess. “Well,” he resumed hastily, “if he likes to do these things, I s'pose he can afford to. Now, what's he going to give her? I s'pose he'll give her a thousand a year; he's got nobody else to leave his money to.”

He stretched out his hand to meet that of a dapper, clean-shaven man, with hardly a hair on his head, a long, broken nose, full lips, and cold grey eyes under rectangular brows.

“Well, Nick,” he muttered, “how are you?”

Nicholas Forsyte, with his bird-like rapidity and the look of a preternaturally sage schoolboy (he had made a large fortune, quite legitimately, out of the companies of which he was a director), placed within that cold palm the tips of his still colder fingers and hastily withdrew them.

“I'm bad,” he said, pouting—“been bad all the week; don't sleep at night. The doctor can't tell why. He's a clever fellow, or I shouldn't have him, but I get nothing out of him but bills.”

“Doctors!” said James, coming down sharp on his words: “I've had all the doctors in London for one or another of us. There's no satisfaction to be got out of them; they'll tell you anything. There's Swithin, now. What good have they done him? There he is; he's bigger than ever; he's enormous; they can't get his weight down. Look at him!”

Swithin Forsyte, tall, square, and broad, with a chest like a pouter pigeon's in its plumage of bright waistcoats, came strutting towards them.

“Er—how are you?” he said in his dandified way, aspirating the 'h' strongly (this difficult letter was almost absolutely safe in his keeping)—“how are you?”

Each brother wore an air of aggravation as he looked at the other two, knowing by experience that they would try to eclipse his ailments.

“We were just saying,” said James, “that you don't get any thinner.”

Swithin protruded his pale round eyes with the effort of hearing.

“Thinner? I'm in good case,” he said, leaning a little forward, “not one of your thread-papers like you!”

But, afraid of losing the expansion of his chest, he leaned back again into a state of immobility, for he prized nothing so highly as a distinguished appearance.

Aunt Ann turned her old eyes from one to the other. Indulgent and severe was her look. In turn the three brothers looked at Ann. She was getting shaky. Wonderful woman! Eighty-six if a day; might live another ten years, and had never been strong. Swithin and James, the twins, were only seventy-five, Nicholas a mere baby of seventy or so. All were strong, and the inference was comforting. Of all forms of property their respective healths naturally concerned them most.

“I'm very well in myself,” proceeded James, “but my nerves are out of order. The least thing worries me to death. I shall have to go to Bath.”

“Bath!” said Nicholas. “I've tried Harrogate. That's no good. What I want is sea air. There's nothing like Yarmouth. Now, when I go there I sleep....”

“My liver's very bad,” interrupted Swithin slowly. “Dreadful pain here;” and he placed his hand on his right side.

“Want of exercise,” muttered James, his eyes on the china. He quickly added: “I get a pain there, too.”

Swithin reddened, a resemblance to a turkey-cock coming upon his old face.

“Exercise!” he said. “I take plenty: I never use the lift at the Club.”

“I didn't know,” James hurried out. “I know nothing about anybody; nobody tells me anything....”

Swithin fixed him with a stare:

“What do you do for a pain there?”

James brightened.

“I take a compound....”

“How are you, uncle?”

June stood before him, her resolute small face raised from her little height to his great height, and her hand outheld.

The brightness faded from James's visage.

“How are you?” he said, brooding over her. “So you're going to Wales to-morrow to visit your young man's aunts? You'll have a lot of rain there. This isn't real old Worcester.” He tapped the bowl. “Now, that set I gave your mother when she married was the genuine thing.”

June shook hands one by one with her three great-uncles, and turned to Aunt Ann. A very sweet look had come into the old lady's face, she kissed the girl's check with trembling fervour.

“Well, my dear,” she said, “and so you're going for a whole month!”

The girl passed on, and Aunt Ann looked after her slim little figure. The old lady's round, steel grey eyes, over which a film like a bird's was beginning to come, followed her wistfully amongst the bustling crowd, for people were beginning to say good-bye; and her finger-tips, pressing and pressing against each other, were busy again with the recharging of her will against that inevitable ultimate departure of her own.

'Yes,' she thought, 'everybody's been most kind; quite a lot of people come to congratulate her. She ought to be very happy.' Amongst the throng of people by the door, the well-dressed throng drawn from the families of lawyers and doctors, from the Stock Exchange, and all the innumerable avocations of the upper-middle class—there were only some twenty percent of Forsytes; but to Aunt Ann they seemed all Forsytes—and certainly there was not much difference—she saw only her own flesh and blood. It was her world, this family, and she knew no other, had never perhaps known any other. All their little secrets, illnesses, engagements, and marriages, how they were getting on, and whether they were making money—all this was her property, her delight, her life; beyond this only a vague, shadowy mist of facts and persons of no real significance. This it was that she would have to lay down when it came to her turn to die; this which gave to her that importance, that secret self-importance, without which none of us can bear to live; and to this she clung wistfully, with a greed that grew each day! If life were slipping away from her, this she would retain to the end.

She thought of June's father, young Jolyon, who had run away with that foreign girl. And what a sad blow to his father and to them all. Such a promising young fellow! A sad blow, though there had been no public scandal, most fortunately, Jo's wife seeking for no divorce! A long time ago! And when June's mother died, six years ago, Jo had married that woman, and they had two children now, so she had heard. Still, he had forfeited his right to be there, had cheated her of the complete fulfilment of her family pride, deprived her of the rightful pleasure of seeing and kissing him of whom she had been so proud, such a promising young fellow! The thought rankled with the bitterness of a long-inflicted injury in her tenacious old heart. A little water stood in her eyes. With a handkerchief of the finest lawn she wiped them stealthily.

“Well, Aunt Ann?” said a voice behind.

Soames Forsyte, flat-shouldered, clean-shaven, flat-cheeked, flat-waisted, yet with something round and secret about his whole appearance, looked downwards and aslant at Aunt Ann, as though trying to see through the side of his own nose.

“And what do you think of the engagement?” he asked.

Aunt Ann's eyes rested on him proudly; of all the nephews since young Jolyon's departure from the family nest, he was now her favourite, for she recognised in him a sure trustee of the family soul that must so soon slip beyond her keeping.

“Very nice for the young man,” she said; “and he's a good-looking young fellow; but I doubt if he's quite the right lover for dear June.”

Soames touched the edge of a gold-lacquered lustre.

“She'll tame him,” he said, stealthily wetting his finger and rubbing it on the knobby bulbs. “That's genuine old lacquer; you can't get it nowadays. It'd do well in a sale at Jobson's.” He spoke with relish, as though he felt that he was cheering up his old aunt. It was seldom he was so confidential. “I wouldn't mind having it myself,” he added; “you can always get your price for old lacquer.”

“You're so clever with all those things,” said Aunt Ann. “And how is dear Irene?”

Soames's smile died.

“Pretty well,” he said. “Complains she can't sleep; she sleeps a great deal better than I do,” and he looked at his wife, who was talking to Bosinney by the door.

Aunt Ann sighed.

“Perhaps,” she said, “it will be just as well for her not to see so much of June. She's such a decided character, dear June!”

Soames flushed; his flushes passed rapidly over his flat cheeks and centered between his eyes, where they remained, the stamp of disturbing thoughts.

“I don't know what she sees in that little flibbertigibbet,” he burst out, but noticing that they were no longer alone, he turned and again began examining the lustre.

“They tell me Jolyon's bought another house,” said his father's voice close by; “he must have a lot of money—he must have more money than he knows what to do with! Montpellier Square, they say; close to Soames! They never told me, Irene never tells me anything!”

“Capital position, not two minutes from me,” said the voice of Swithin, “and from my rooms I can drive to the Club in eight.”

The position of their houses was of vital importance to the Forsytes, nor was this remarkable, since the whole spirit of their success was embodied therein.

Their father, of farming stock, had come from Dorsetshire near the beginning of the century.

'Superior Dosset Forsyte, as he was called by his intimates, had been a stonemason by trade, and risen to the position of a master-builder.

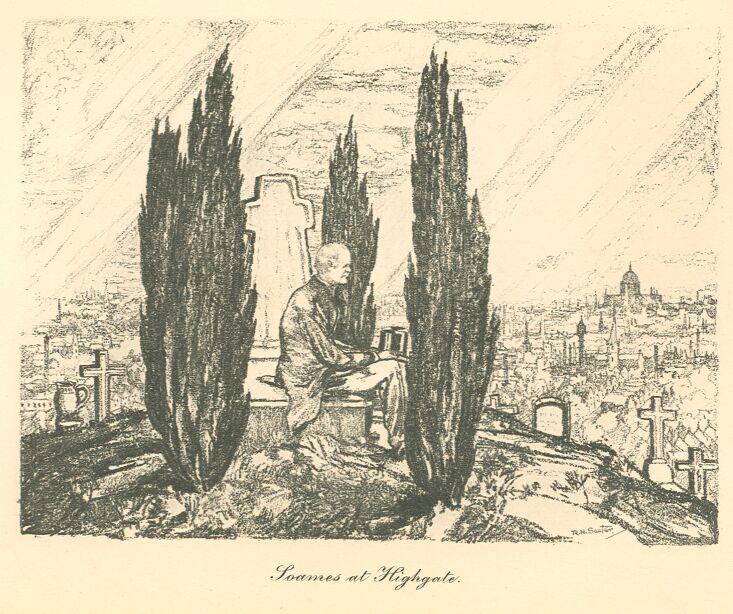

Towards the end of his life he moved to London, where, building on until he died, he was buried at Highgate. He left over thirty thousand pounds between his ten children. Old Jolyon alluded to him, if at all, as 'A hard, thick sort of man; not much refinement about him.' The second generation of Forsytes felt indeed that he was not greatly to their credit. The only aristocratic trait they could find in his character was a habit of drinking Madeira.

Aunt Hester, an authority on family history, described him thus: “I don't recollect that he ever did anything; at least, not in my time. He was er—an owner of houses, my dear. His hair about your Uncle Swithin's colour; rather a square build. Tall? No—not very tall” (he had been five feet five, with a mottled face); “a fresh-coloured man. I remember he used to drink Madeira; but ask your Aunt Ann. What was his father? He—er—had to do with the land down in Dorsetshire, by the sea.”

James once went down to see for himself what sort of place this was that they had come from. He found two old farms, with a cart track rutted into the pink earth, leading down to a mill by the beach; a little grey church with a buttressed outer wall, and a smaller and greyer chapel. The stream which worked the mill came bubbling down in a dozen rivulets, and pigs were hunting round that estuary. A haze hovered over the prospect. Down this hollow, with their feet deep in the mud and their faces towards the sea, it appeared that the primeval Forsytes had been content to walk Sunday after Sunday for hundreds of years.

Whether or no James had cherished hopes of an inheritance, or of something rather distinguished to be found down there, he came back to town in a poor way, and went about with a pathetic attempt at making the best of a bad job.

“There's very little to be had out of that,” he said; “regular country little place, old as the hills....”

Its age was felt to be a comfort. Old Jolyon, in whom a desperate honesty welled up at times, would allude to his ancestors as: “Yeomen—I suppose very small beer.” Yet he would repeat the word 'yeomen' as if it afforded him consolation.

They had all done so well for themselves, these Forsytes, that they were all what is called 'of a certain position.' They had shares in all sorts of things, not as yet—with the exception of Timothy—in consols, for they had no dread in life like that of 3 per cent. for their money. They collected pictures, too, and were supporters of such charitable institutions as might be beneficial to their sick domestics. From their father, the builder, they inherited a talent for bricks and mortar. Originally, perhaps, members of some primitive sect, they were now in the natural course of things members of the Church of England, and caused their wives and children to attend with some regularity the more fashionable churches of the Metropolis. To have doubted their Christianity would have caused them both pain and surprise. Some of them paid for pews, thus expressing in the most practical form their sympathy with the teachings of Christ.

Their residences, placed at stated intervals round the park, watched like sentinels, lest the fair heart of this London, where their desires were fixed, should slip from their clutches, and leave them lower in their own estimations.

There was old Jolyon in Stanhope Place; the Jameses in Park Lane; Swithin in the lonely glory of orange and blue chambers in Hyde Park Mansions—he had never married, not he—the Soamses in their nest off Knightsbridge; the Rogers in Prince's Gardens (Roger was that remarkable Forsyte who had conceived and carried out the notion of bringing up his four sons to a new profession. “Collect house property, nothing like it,” he would say; “I never did anything else”).

The Haymans again—Mrs. Hayman was the one married Forsyte sister—in a house high up on Campden Hill, shaped like a giraffe, and so tall that it gave the observer a crick in the neck; the Nicholases in Ladbroke Grove, a spacious abode and a great bargain; and last, but not least, Timothy's on the Bayswater Road, where Ann, and Juley, and Hester, lived under his protection.

But all this time James was musing, and now he inquired of his host and brother what he had given for that house in Montpellier Square. He himself had had his eye on a house there for the last two years, but they wanted such a price.

Old Jolyon recounted the details of his purchase.

“Twenty-two years to run?” repeated James; “The very house I was after—you've given too much for it!”

Old Jolyon frowned.

“It's not that I want it,” said James hastily; “it wouldn't suit my purpose at that price. Soames knows the house, well—he'll tell you it's too dear—his opinion's worth having.”

“I don't,” said old Jolyon, “care a fig for his opinion.”

“Well,” murmured James, “you will have your own way—it's a good opinion. Good-bye! We're going to drive down to Hurlingham. They tell me June's going to Wales. You'll be lonely tomorrow. What'll you do with yourself? You'd better come and dine with us!”

Old Jolyon refused. He went down to the front door and saw them into their barouche, and twinkled at them, having already forgotten his spleen—Mrs. James facing the horses, tall and majestic with auburn hair; on her left, Irene—the two husbands, father and son, sitting forward, as though they expected something, opposite their wives. Bobbing and bounding upon the spring cushions, silent, swaying to each motion of their chariot, old Jolyon watched them drive away under the sunlight.

During the drive the silence was broken by Mrs. James.

“Did you ever see such a collection of rumty-too people?”

Soames, glancing at her beneath his eyelids, nodded, and he saw Irene steal at him one of her unfathomable looks. It is likely enough that each branch of the Forsyte family made that remark as they drove away from old Jolyon's 'At Home!'

Amongst the last of the departing guests the fourth and fifth brothers, Nicholas and Roger, walked away together, directing their steps alongside Hyde Park towards the Praed Street Station of the Underground. Like all other Forsytes of a certain age they kept carriages of their own, and never took cabs if by any means they could avoid it.

The day was bright, the trees of the Park in the full beauty of mid-June foliage; the brothers did not seem to notice phenomena, which contributed, nevertheless, to the jauntiness of promenade and conversation.

“Yes,” said Roger, “she's a good-lookin' woman, that wife of Soames's. I'm told they don't get on.”

This brother had a high forehead, and the freshest colour of any of the Forsytes; his light grey eyes measured the street frontage of the houses by the way, and now and then he would level his, umbrella and take a 'lunar,' as he expressed it, of the varying heights.

“She'd no money,” replied Nicholas.

He himself had married a good deal of money, of which, it being then the golden age before the Married Women's Property Act, he had mercifully been enabled to make a successful use.

“What was her father?”

“Heron was his name, a Professor, so they tell me.”

Roger shook his head.

“There's no money in that,” he said.

“They say her mother's father was cement.”

Roger's face brightened.

“But he went bankrupt,” went on Nicholas.

“Ah!” exclaimed Roger, “Soames will have trouble with her; you mark my words, he'll have trouble—she's got a foreign look.”

Nicholas licked his lips.

“She's a pretty woman,” and he waved aside a crossing-sweeper.

“How did he get hold of her?” asked Roger presently. “She must cost him a pretty penny in dress!”

“Ann tells me,” replied Nicholas, “he was half-cracked about her. She refused him five times. James, he's nervous about it, I can see.”

“Ah!” said Roger again; “I'm sorry for James; he had trouble with Dartie.” His pleasant colour was heightened by exercise, he swung his umbrella to the level of his eye more frequently than ever. Nicholas's face also wore a pleasant look.

“Too pale for me,” he said, “but her figures capital!”

Roger made no reply.

“I call her distinguished-looking,” he said at last—it was the highest praise in the Forsyte vocabulary. “That young Bosinney will never do any good for himself. They say at Burkitt's he's one of these artistic chaps—got an idea of improving English architecture; there's no money in that! I should like to hear what Timothy would say to it.”

They entered the station.

“What class are you going? I go second.”

“No second for me,” said Nicholas;—“you never know what you may catch.”

He took a first-class ticket to Notting Hill Gate; Roger a second to South Kensington. The train coming in a minute later, the two brothers parted and entered their respective compartments. Each felt aggrieved that the other had not modified his habits to secure his society a little longer; but as Roger voiced it in his thoughts:

'Always a stubborn beggar, Nick!'

And as Nicholas expressed it to himself:

'Cantankerous chap Roger—always was!'

There was little sentimentality about the Forsytes. In that great London, which they had conquered and become merged in, what time had they to be sentimental?

At five o'clock the following day old Jolyon sat alone, a cigar between his lips, and on a table by his side a cup of tea. He was tired, and before he had finished his cigar he fell asleep. A fly settled on his hair, his breathing sounded heavy in the drowsy silence, his upper lip under the white moustache puffed in and out. From between the fingers of his veined and wrinkled hand the cigar, dropping on the empty hearth, burned itself out.

The gloomy little study, with windows of stained glass to exclude the view, was full of dark green velvet and heavily-carved mahogany—a suite of which old Jolyon was wont to say: 'Shouldn't wonder if it made a big price some day!'

It was pleasant to think that in the after life he could get more for things than he had given.

In the rich brown atmosphere peculiar to back rooms in the mansion of a Forsyte, the Rembrandtesque effect of his great head, with its white hair, against the cushion of his high-backed seat, was spoiled by the moustache, which imparted a somewhat military look to his face. An old clock that had been with him since before his marriage forty years ago kept with its ticking a jealous record of the seconds slipping away forever from its old master.

He had never cared for this room, hardly going into it from one year's end to another, except to take cigars from the Japanese cabinet in the corner, and the room now had its revenge.

His temples, curving like thatches over the hollows beneath, his cheek-bones and chin, all were sharpened in his sleep, and there had come upon his face the confession that he was an old man.

He woke. June had gone! James had said he would be lonely. James had always been a poor thing. He recollected with satisfaction that he had bought that house over James's head.

Serve him right for sticking at the price; the only thing the fellow thought of was money. Had he given too much, though? It wanted a lot of doing to—He dared say he would want all his money before he had done with this affair of June's. He ought never to have allowed the engagement. She had met this Bosinney at the house of Baynes, Baynes and Bildeboy, the architects. He believed that Baynes, whom he knew—a bit of an old woman—was the young man's uncle by marriage. After that she'd been always running after him; and when she took a thing into her head there was no stopping her. She was continually taking up with 'lame ducks' of one sort or another. This fellow had no money, but she must needs become engaged to him—a harumscarum, unpractical chap, who would get himself into no end of difficulties.

She had come to him one day in her slap-dash way and told him; and, as if it were any consolation, she had added:

“He's so splendid; he's often lived on cocoa for a week!”

“And he wants you to live on cocoa too?”

“Oh no; he is getting into the swim now.”

Old Jolyon had taken his cigar from under his white moustaches, stained by coffee at the edge, and looked at her, that little slip of a thing who had got such a grip of his heart. He knew more about 'swims' than his granddaughter. But she, having clasped her hands on his knees, rubbed her chin against him, making a sound like a purring cat. And, knocking the ash off his cigar, he had exploded in nervous desperation:

“You're all alike: you won't be satisfied till you've got what you want. If you must come to grief, you must; I wash my hands of it.”

So, he had washed his hands of it, making the condition that they should not marry until Bosinney had at least four hundred a year.

“I shan't be able to give you very much,” he had said, a formula to which June was not unaccustomed. “Perhaps this What's-his-name will provide the cocoa.”

He had hardly seen anything of her since it began. A bad business! He had no notion of giving her a lot of money to enable a fellow he knew nothing about to live on in idleness. He had seen that sort of thing before; no good ever came of it. Worst of all, he had no hope of shaking her resolution; she was as obstinate as a mule, always had been from a child. He didn't see where it was to end. They must cut their coat according to their cloth. He would not give way till he saw young Bosinney with an income of his own. That June would have trouble with the fellow was as plain as a pikestaff; he had no more idea of money than a cow. As to this rushing down to Wales to visit the young man's aunts, he fully expected they were old cats.

And, motionless, old Jolyon stared at the wall; but for his open eyes, he might have been asleep.... The idea of supposing that young cub Soames could give him advice! He had always been a cub, with his nose in the air! He would be setting up as a man of property next, with a place in the country! A man of property! H'mph! Like his father, he was always nosing out bargains, a cold-blooded young beggar!

He rose, and, going to the cabinet, began methodically stocking his cigar-case from a bundle fresh in. They were not bad at the price, but you couldn't get a good cigar, nowadays, nothing to hold a candle to those old Superfinos of Hanson and Bridger's. That was a cigar!

The thought, like some stealing perfume, carried him back to those wonderful nights at Richmond when after dinner he sat smoking on the terrace of the Crown and Sceptre with Nicholas Treffry and Traquair and Jack Herring and Anthony Thornworthy. How good his cigars were then! Poor old Nick!—dead, and Jack Herring—dead, and Traquair—dead of that wife of his, and Thornworthy—awfully shaky (no wonder, with his appetite).

Of all the company of those days he himself alone seemed left, except Swithin, of course, and he so outrageously big there was no doing anything with him.

Difficult to believe it was so long ago; he felt young still! Of all his thoughts, as he stood there counting his cigars, this was the most poignant, the most bitter. With his white head and his loneliness he had remained young and green at heart. And those Sunday afternoons on Hampstead Heath, when young Jolyon and he went for a stretch along the Spaniard's Road to Highgate, to Child's Hill, and back over the Heath again to dine at Jack Straw's Castle—how delicious his cigars were then! And such weather! There was no weather now.

When June was a toddler of five, and every other Sunday he took her to the Zoo, away from the society of those two good women, her mother and her grandmother, and at the top of the bear den baited his umbrella with buns for her favourite bears, how sweet his cigars were then!

Cigars! He had not even succeeded in out-living his palate—the famous palate that in the fifties men swore by, and speaking of him, said: “Forsyte's the best palate in London!” The palate that in a sense had made his fortune—the fortune of the celebrated tea men, Forsyte and Treffry, whose tea, like no other man's tea, had a romantic aroma, the charm of a quite singular genuineness. About the house of Forsyte and Treffry in the City had clung an air of enterprise and mystery, of special dealings in special ships, at special ports, with special Orientals.

He had worked at that business! Men did work in those days! these young pups hardly knew the meaning of the word. He had gone into every detail, known everything that went on, sometimes sat up all night over it. And he had always chosen his agents himself, prided himself on it. His eye for men, he used to say, had been the secret of his success, and the exercise of this masterful power of selection had been the only part of it all that he had really liked. Not a career for a man of his ability. Even now, when the business had been turned into a Limited Liability Company, and was declining (he had got out of his shares long ago), he felt a sharp chagrin in thinking of that time. How much better he might have done! He would have succeeded splendidly at the Bar! He had even thought of standing for Parliament. How often had not Nicholas Treffry said to him:

“You could do anything, Jo, if you weren't so d-damned careful of yourself!” Dear old Nick! Such a good fellow, but a racketty chap! The notorious Treffry! He had never taken any care of himself. So he was dead. Old Jolyon counted his cigars with a steady hand, and it came into his mind to wonder if perhaps he had been too careful of himself.

He put the cigar-case in the breast of his coat, buttoned it in, and walked up the long flights to his bedroom, leaning on one foot and the other, and helping himself by the bannister. The house was too big. After June was married, if she ever did marry this fellow, as he supposed she would, he would let it and go into rooms. What was the use of keeping half a dozen servants eating their heads off?

The butler came to the ring of his bell—a large man with a beard, a soft tread, and a peculiar capacity for silence. Old Jolyon told him to put his dress clothes out; he was going to dine at the Club.

How long had the carriage been back from taking Miss June to the station? Since two? Then let him come round at half-past six!

The Club which old Jolyon entered on the stroke of seven was one of those political institutions of the upper middle class which have seen better days. In spite of being talked about, perhaps in consequence of being talked about, it betrayed a disappointing vitality. People had grown tired of saying that the 'Disunion' was on its last legs. Old Jolyon would say it, too, yet disregarded the fact in a manner truly irritating to well-constituted Clubmen.

“Why do you keep your name on?” Swithin often asked him with profound vexation. “Why don't you join the 'Polyglot'. You can't get a wine like our Heidsieck under twenty shillin' a bottle anywhere in London;” and, dropping his voice, he added: “There's only five hundred dozen left. I drink it every night of my life.”

“I'll think of it,” old Jolyon would answer; but when he did think of it there was always the question of fifty guineas entrance fee, and it would take him four or five years to get in. He continued to think of it.

He was too old to be a Liberal, had long ceased to believe in the political doctrines of his Club, had even been known to allude to them as 'wretched stuff,' and it afforded him pleasure to continue a member in the teeth of principles so opposed to his own. He had always had a contempt for the place, having joined it many years ago when they refused to have him at the 'Hotch Potch' owing to his being 'in trade.' As if he were not as good as any of them! He naturally despised the Club that did take him. The members were a poor lot, many of them in the City—stockbrokers, solicitors, auctioneers—what not! Like most men of strong character but not too much originality, old Jolyon set small store by the class to which he belonged. Faithfully he followed their customs, social and otherwise, and secretly he thought them 'a common lot.'

Years and philosophy, of which he had his share, had dimmed the recollection of his defeat at the 'Hotch Potch'. and now in his thoughts it was enshrined as the Queen of Clubs. He would have been a member all these years himself, but, owing to the slipshod way his proposer, Jack Herring, had gone to work, they had not known what they were doing in keeping him out. Why! they had taken his son Jo at once, and he believed the boy was still a member; he had received a letter dated from there eight years ago.

He had not been near the 'Disunion' for months, and the house had undergone the piebald decoration which people bestow on old houses and old ships when anxious to sell them.

'Beastly colour, the smoking-room!' he thought. 'The dining-room is good!'

Its gloomy chocolate, picked out with light green, took his fancy.

He ordered dinner, and sat down in the very corner, at the very table perhaps! (things did not progress much at the 'Disunion,' a Club of almost Radical principles) at which he and young Jolyon used to sit twenty-five years ago, when he was taking the latter to Drury Lane, during his holidays.

The boy had loved the theatre, and old Jolyon recalled how he used to sit opposite, concealing his excitement under a careful but transparent nonchalance.

He ordered himself, too, the very dinner the boy had always chosen-soup, whitebait, cutlets, and a tart. Ah! if he were only opposite now!

The two had not met for fourteen years. And not for the first time during those fourteen years old Jolyon wondered whether he had been a little to blame in the matter of his son. An unfortunate love-affair with that precious flirt Danae Thornworthy (now Danae Pellew), Anthony Thornworthy's daughter, had thrown him on the rebound into the arms of June's mother. He ought perhaps to have put a spoke in the wheel of their marriage; they were too young; but after that experience of Jo's susceptibility he had been only too anxious to see him married. And in four years the crash had come! To have approved his son's conduct in that crash was, of course, impossible; reason and training—that combination of potent factors which stood for his principles—told him of this impossibility, and his heart cried out. The grim remorselessness of that business had no pity for hearts. There was June, the atom with flaming hair, who had climbed all over him, twined and twisted herself about him—about his heart that was made to be the plaything and beloved resort of tiny, helpless things. With characteristic insight he saw he must part with one or with the other; no half-measures could serve in such a situation. In that lay its tragedy. And the tiny, helpless thing prevailed. He would not run with the hare and hunt with the hounds, and so to his son he said good-bye.

That good-bye had lasted until now.

He had proposed to continue a reduced allowance to young Jolyon, but this had been refused, and perhaps that refusal had hurt him more than anything, for with it had gone the last outlet of his penned-in affection; and there had come such tangible and solid proof of rupture as only a transaction in property, a bestowal or refusal of such, could supply.

His dinner tasted flat. His pint of champagne was dry and bitter stuff, not like the Veuve Clicquots of old days.

Over his cup of coffee, he bethought him that he would go to the opera. In the Times, therefore—he had a distrust of other papers—he read the announcement for the evening. It was 'Fidelio.'

Mercifully not one of those new-fangled German pantomimes by that fellow Wagner.

Putting on his ancient opera hat, which, with its brim flattened by use, and huge capacity, looked like an emblem of greater days, and, pulling out an old pair of very thin lavender kid gloves smelling strongly of Russia leather, from habitual proximity to the cigar-case in the pocket of his overcoat, he stepped into a hansom.

The cab rattled gaily along the streets, and old Jolyon was struck by their unwonted animation.

'The hotels must be doing a tremendous business,' he thought. A few years ago there had been none of these big hotels. He made a satisfactory reflection on some property he had in the neighbourhood. It must be going up in value by leaps and bounds! What traffic!

But from that he began indulging in one of those strange impersonal speculations, so uncharacteristic of a Forsyte, wherein lay, in part, the secret of his supremacy amongst them. What atoms men were, and what a lot of them! And what would become of them all?

He stumbled as he got out of the cab, gave the man his exact fare, walked up to the ticket office to take his stall, and stood there with his purse in his hand—he always carried his money in a purse, never having approved of that habit of carrying it loosely in the pockets, as so many young men did nowadays. The official leaned out, like an old dog from a kennel.

“Why,” he said in a surprised voice, “it's Mr. Jolyon Forsyte! So it is! Haven't seen you, sir, for years. Dear me! Times aren't what they were. Why! you and your brother, and that auctioneer—Mr. Traquair, and Mr. Nicholas Treffry—you used to have six or seven stalls here regular every season. And how are you, sir? We don't get younger!”

The colour in old Jolyon's eyes deepened; he paid his guinea. They had not forgotten him. He marched in, to the sounds of the overture, like an old war-horse to battle.

Folding his opera hat, he sat down, drew out his lavender gloves in the old way, and took up his glasses for a long look round the house. Dropping them at last on his folded hat, he fixed his eyes on the curtain. More poignantly than ever he felt that it was all over and done with him. Where were all the women, the pretty women, the house used to be so full of? Where was that old feeling in the heart as he waited for one of those great singers? Where that sensation of the intoxication of life and of his own power to enjoy it all?

The greatest opera-goer of his day! There was no opera now! That fellow Wagner had ruined everything; no melody left, nor any voices to sing it. Ah! the wonderful singers! Gone! He sat watching the old scenes acted, a numb feeling at his heart.

From the curl of silver over his ear to the pose of his foot in its elastic-sided patent boot, there was nothing clumsy or weak about old Jolyon. He was as upright—very nearly—as in those old times when he came every night; his sight was as good—almost as good. But what a feeling of weariness and disillusion!

He had been in the habit all his life of enjoying things, even imperfect things—and there had been many imperfect things—he had enjoyed them all with moderation, so as to keep himself young. But now he was deserted by his power of enjoyment, by his philosophy, and left with this dreadful feeling that it was all done with. Not even the Prisoners' Chorus, nor Florian's Song, had the power to dispel the gloom of his loneliness.

If Jo were only with him! The boy must be forty by now. He had wasted fourteen years out of the life of his only son. And Jo was no longer a social pariah. He was married. Old Jolyon had been unable to refrain from marking his appreciation of the action by enclosing his son a cheque for L500. The cheque had been returned in a letter from the 'Hotch Potch,' couched in these words.

'MY DEAREST FATHER,

'Your generous gift was welcome as a sign that you might think worse of me. I return it, but should you think fit to invest it for the benefit of the little chap (we call him Jolly), who bears our Christian and, by courtesy, our surname, I shall be very glad.

'I hope with all my heart that your health is as good as ever.

'Your loving son,

'Jo.'

The letter was like the boy. He had always been an amiable chap. Old Jolyon had sent this reply:

'MY DEAR JO,

'The sum (L500) stands in my books for the benefit of your boy, under the name of Jolyon Forsyte, and will be duly-credited with interest at 5 per cent. I hope that you are doing well. My health remains good at present.

'With love, I am,

'Your affectionate Father,

'JOLYON FORSYTE.'

And every year on the 1st of January he had added a hundred and the interest. The sum was mounting up—next New Year's Day it would be fifteen hundred and odd pounds! And it is difficult to say how much satisfaction he had got out of that yearly transaction. But the correspondence had ended.

In spite of his love for his son, in spite of an instinct, partly constitutional, partly the result, as in thousands of his class, of the continual handling and watching of affairs, prompting him to judge conduct by results rather than by principle, there was at the bottom of his heart a sort of uneasiness. His son ought, under the circumstances, to have gone to the dogs; that law was laid down in all the novels, sermons, and plays he had ever read, heard, or witnessed.

After receiving the cheque back there seemed to him to be something wrong somewhere. Why had his son not gone to the dogs? But, then, who could tell?

He had heard, of course—in fact, he had made it his business to find out—that Jo lived in St. John's Wood, that he had a little house in Wistaria Avenue with a garden, and took his wife about with him into society—a queer sort of society, no doubt—and that they had two children—the little chap they called Jolly (considering the circumstances the name struck him as cynical, and old Jolyon both feared and disliked cynicism), and a girl called Holly, born since the marriage. Who could tell what his son's circumstances really were? He had capitalized the income he had inherited from his mother's father and joined Lloyd's as an underwriter; he painted pictures, too—water-colours. Old Jolyon knew this, for he had surreptitiously bought them from time to time, after chancing to see his son's name signed at the bottom of a representation of the river Thames in a dealer's window. He thought them bad, and did not hang them because of the signature; he kept them locked up in a drawer.

In the great opera-house a terrible yearning came on him to see his son. He remembered the days when he had been wont to slide him, in a brown holland suit, to and fro under the arch of his legs; the times when he ran beside the boy's pony, teaching him to ride; the day he first took him to school. He had been a loving, lovable little chap! After he went to Eton he had acquired, perhaps, a little too much of that desirable manner which old Jolyon knew was only to be obtained at such places and at great expense; but he had always been companionable. Always a companion, even after Cambridge—a little far off, perhaps, owing to the advantages he had received. Old Jolyon's feeling towards our public schools and 'Varsities never wavered, and he retained touchingly his attitude of admiration and mistrust towards a system appropriate to the highest in the land, of which he had not himself been privileged to partake.... Now that June had gone and left, or as good as left him, it would have been a comfort to see his son again. Guilty of this treason to his family, his principles, his class, old Jolyon fixed his eyes on the singer. A poor thing—a wretched poor thing! And the Florian a perfect stick!

It was over. They were easily pleased nowadays!

In the crowded street he snapped up a cab under the very nose of a stout and much younger gentleman, who had already assumed it to be his own. His route lay through Pall Mall, and at the corner, instead of going through the Green Park, the cabman turned to drive up St. James's Street. Old Jolyon put his hand through the trap (he could not bear being taken out of his way); in turning, however, he found himself opposite the 'Hotch Potch,' and the yearning that had been secretly with him the whole evening prevailed. He called to the driver to stop. He would go in and ask if Jo still belonged there.

He went in. The hall looked exactly as it did when he used to dine there with Jack Herring, and they had the best cook in London; and he looked round with the shrewd, straight glance that had caused him all his life to be better served than most men.

“Mr. Jolyon Forsyte still a member here?”

“Yes, sir; in the Club now, sir. What name?”

Old Jolyon was taken aback.

“His father,” he said.

And having spoken, he took his stand, back to the fireplace.

Young Jolyon, on the point of leaving the Club, had put on his hat, and was in the act of crossing the hall, as the porter met him. He was no longer young, with hair going grey, and face—a narrower replica of his father's, with the same large drooping moustache—decidedly worn. He turned pale. This meeting was terrible after all those years, for nothing in the world was so terrible as a scene. They met and crossed hands without a word. Then, with a quaver in his voice, the father said:

“How are you, my boy?”

The son answered:

“How are you, Dad?”

Old Jolyon's hand trembled in its thin lavender glove.

“If you're going my way,” he said, “I can give you a lift.”

And as though in the habit of taking each other home every night they went out and stepped into the cab.

To old Jolyon it seemed that his son had grown. 'More of a man altogether,' was his comment. Over the natural amiability of that son's face had come a rather sardonic mask, as though he had found in the circumstances of his life the necessity for armour. The features were certainly those of a Forsyte, but the expression was more the introspective look of a student or philosopher. He had no doubt been obliged to look into himself a good deal in the course of those fifteen years.

To young Jolyon the first sight of his father was undoubtedly a shock—he looked so worn and old. But in the cab he seemed hardly to have changed, still having the calm look so well remembered, still being upright and keen-eyed.

“You look well, Dad.”

“Middling,” old Jolyon answered.

He was the prey of an anxiety that he found he must put into words. Having got his son back like this, he felt he must know what was his financial position.

“Jo,” he said, “I should like to hear what sort of water you're in. I suppose you're in debt?”

He put it this way that his son might find it easier to confess.

Young Jolyon answered in his ironical voice:

“No! I'm not in debt!”

Old Jolyon saw that he was angry, and touched his hand. He had run a risk. It was worth it, however, and Jo had never been sulky with him. They drove on, without speaking again, to Stanhope Gate. Old Jolyon invited him in, but young Jolyon shook his head.

“June's not here,” said his father hastily: “went of to-day on a visit. I suppose you know that she's engaged to be married?”

“Already?” murmured young Jolyon'.

Old Jolyon stepped out, and, in paying the cab fare, for the first time in his life gave the driver a sovereign in mistake for a shilling.

Placing the coin in his mouth, the cabman whipped his horse secretly on the underneath and hurried away.

Old Jolyon turned the key softly in the lock, pushed open the door, and beckoned. His son saw him gravely hanging up his coat, with an expression on his face like that of a boy who intends to steal cherries.

The door of the dining-room was open, the gas turned low; a spirit-urn hissed on a tea-tray, and close to it a cynical looking cat had fallen asleep on the dining-table. Old Jolyon 'shoo'd' her off at once. The incident was a relief to his feelings; he rattled his opera hat behind the animal.

“She's got fleas,” he said, following her out of the room. Through the door in the hall leading to the basement he called “Hssst!” several times, as though assisting the cat's departure, till by some strange coincidence the butler appeared below.

“You can go to bed, Parfitt,” said old Jolyon. “I will lock up and put out.”

When he again entered the dining-room the cat unfortunately preceded him, with her tail in the air, proclaiming that she had seen through this manouevre for suppressing the butler from the first....

A fatality had dogged old Jolyon's domestic stratagems all his life.

Young Jolyon could not help smiling. He was very well versed in irony, and everything that evening seemed to him ironical. The episode of the cat; the announcement of his own daughter's engagement. So he had no more part or parcel in her than he had in the Puss! And the poetical justice of this appealed to him.

“What is June like now?” he asked.

“She's a little thing,” returned old Jolyon; “they say she's like me, but that's their folly. She's more like your mother—the same eyes and hair.”

“Ah! and she is pretty?”

Old Jolyon was too much of a Forsyte to praise anything freely; especially anything for which he had a genuine admiration.

“Not bad looking—a regular Forsyte chin. It'll be lonely here when she's gone, Jo.”

The look on his face again gave young Jolyon the shock he had felt on first seeing his father.

“What will you do with yourself, Dad? I suppose she's wrapped up in him?”

“Do with myself?” repeated old Jolyon with an angry break in his voice. “It'll be miserable work living here alone. I don't know how it's to end. I wish to goodness....” He checked himself, and added: “The question is, what had I better do with this house?”

Young Jolyon looked round the room. It was peculiarly vast and dreary, decorated with the enormous pictures of still life that he remembered as a boy—sleeping dogs with their noses resting on bunches of carrots, together with onions and grapes lying side by side in mild surprise. The house was a white elephant, but he could not conceive of his father living in a smaller place; and all the more did it all seem ironical.

In his great chair with the book-rest sat old Jolyon, the figurehead of his family and class and creed, with his white head and dome-like forehead, the representative of moderation, and order, and love of property. As lonely an old man as there was in London.

There he sat in the gloomy comfort of the room, a puppet in the power of great forces that cared nothing for family or class or creed, but moved, machine-like, with dread processes to inscrutable ends. This was how it struck young Jolyon, who had the impersonal eye.

The poor old Dad! So this was the end, the purpose to which he had lived with such magnificent moderation! To be lonely, and grow older and older, yearning for a soul to speak to!

In his turn old Jolyon looked back at his son. He wanted to talk about many things that he had been unable to talk about all these years. It had been impossible to seriously confide in June his conviction that property in the Soho quarter would go up in value; his uneasiness about that tremendous silence of Pippin, the superintendent of the New Colliery Company, of which he had so long been chairman; his disgust at the steady fall in American Golgothas, or even to discuss how, by some sort of settlement, he could best avoid the payment of those death duties which would follow his decease. Under the influence, however, of a cup of tea, which he seemed to stir indefinitely, he began to speak at last. A new vista of life was thus opened up, a promised land of talk, where he could find a harbour against the waves of anticipation and regret; where he could soothe his soul with the opium of devising how to round off his property and make eternal the only part of him that was to remain alive.

Young Jolyon was a good listener; it was his great quality. He kept his eyes fixed on his father's face, putting a question now and then.

The clock struck one before old Jolyon had finished, and at the sound of its striking his principles came back. He took out his watch with a look of surprise:

“I must go to bed, Jo,” he said.

Young Jolyon rose and held out his hand to help his father up. The old face looked worn and hollow again; the eyes were steadily averted.

“Good-bye, my boy; take care of yourself.”

A moment passed, and young Jolyon, turning on his, heel, marched out at the door. He could hardly see; his smile quavered. Never in all the fifteen years since he had first found out that life was no simple business, had he found it so singularly complicated.

In Swithin's orange and light-blue dining-room, facing the Park, the round table was laid for twelve.

A cut-glass chandelier filled with lighted candles hung like a giant stalactite above its centre, radiating over large gilt-framed mirrors, slabs of marble on the tops of side-tables, and heavy gold chairs with crewel worked seats. Everything betokened that love of beauty so deeply implanted in each family which has had its own way to make into Society, out of the more vulgar heart of Nature. Swithin had indeed an impatience of simplicity, a love of ormolu, which had always stamped him amongst his associates as a man of great, if somewhat luxurious taste; and out of the knowledge that no one could possibly enter his rooms without perceiving him to be a man of wealth, he had derived a solid and prolonged happiness such as perhaps no other circumstance in life had afforded him.

Since his retirement from land agency, a profession deplorable in his estimation, especially as to its auctioneering department, he had abandoned himself to naturally aristocratic tastes.