Title: James Madison

Author: Sydney Howard Gay

Release date: May 29, 2009 [eBook #28992]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Suzanne Shell, Carla Foust, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Suzanne Shell, Carla Foust,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

Minor punctuation errors have been corrected without notice. Printer's errors have been corrected, and they are indicated with a mouse-hover and listed at the end of this book. All other inconsistencies are as in the original.

Giants of America

The Founding Fathers

James Madision

James Madision

The Home of James Madison

The Home of James Madison

SYDNEY HOWARD GAY

ARLINGTON HOUSE New Rochelle, N.Y.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Virginia Madisons | 1 |

| II. | The Young Statesman | 15 |

| III. | In Congress | 28 |

| IV. | In the State Assembly | 45 |

| V. | In the Virginia Legislature | 61 |

| VI. | Public Disturbances and Anxieties | 73 |

| VII. | The Constitutional Convention | 84 |

| VIII. | "The Compromises" | 94 |

| IX. | Adoption of the Constitution | 110 |

| X. | The First Congress | 122 |

| XI. | National Finances—Slavery | 144 |

| XII. | Federalists and Republicans | 164 |

| XIII. | French Politics | 185 |

| XIV. | His Latest Years in Congress | 207 |

| XV. | At Home—"Resolutions of '98 AND '99" | 225 |

| XVI. | Secretary of State | 242 |

| XVII. | The Embargo | 254 |

| XVIII. | Madison As President | 272 |

| XIX. | War With England | 290 |

| XX. | Conclusion | 309 |

| Index | 325 |

| James Madison | Frontispiece |

From the painting by Sully in the Corcoran Gallery of Art,

Washington, D. C.

Autograph from a MS. in the New York Public Library, Lenox

Building.

The vignette of "Montpelier," Madison's home at Montpelier, Va.,

is from a photograph.

| PAGE |

| Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | facing 98 |

From the original painting by Gilbert Stuart in the possession of

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, D. D., LL. D., Charleston, S. C.

Autograph from a MS. in the New York Public Library, Lenox

Building.

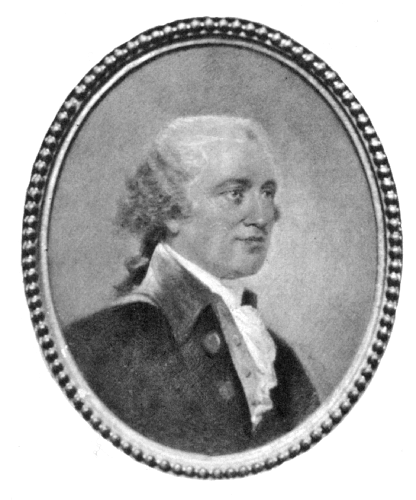

| Fisher Ames | facing 162 |

From the miniature painted by John Trumbull in 1792, now in the

Art Gallery of Yale University.

Autograph from the Chamberlain Collection, Boston Public Library.

| Dolly P. Madison | facing 222 |

From a miniature in the possession of Dr. H. M. Cutts,

Brookline, Mass.

Autograph from a letter kindly loaned by Dr. Cutts.

| Battle of Lake Erie | facing 310 |

From the painting by W. H. Powell in the Capitol at Washington.

James Madison was born on March 16, 1751, at Port Conway, Virginia; he died at Montpellier, in that State, on June 28, 1836. Mr. John Quincy Adams, recalling, perhaps, the death of his own father and of Jefferson on the same Fourth of July, and that of Monroe on a subsequent anniversary of that day, may possibly have seen a generous propriety in finding some equally appropriate commemoration for the death of another Virginian President. For it was quite possible that Virginia might think him capable of an attempt to conceal, what to her mind would seem to be an obvious intention of Providence: that all the children of the "Mother of Presidents" should be no less distinguished in their deaths than in their lives—that the "other dynasty," which John Randolph was wont to talk about, should no longer pretend to an equality with them, not merely in this world, but in the manner of going out of it. At any rate,[2] he notes the date of Madison's death, the twenty-eighth day of June, as "the anniversary of the day on which the ratification of the Convention of Virginia in 1788 had affixed the seal of James Madison as the father of the Constitution of the United States, when his earthly part sank without a struggle into the grave, and a spirit, bright as the seraphim that surround the throne of Omnipotence, ascended to the bosom of his God." There can be no doubt of the deep sincerity of this tribute, whatever question there may be of its grammatical construction and its rhetoric, and although the date is erroneous. The ratification of the Constitution of the United States by the Virginia Convention was on June 25, not on June 28. It is the misfortune of our time that we have no living great men held in such universal veneration that their dying on common days like common mortals seems quite impossible. Half a century ago, however, the propriety of such providential arrangements appears to have been recognized almost as one of the "institutions." It was the newspaper gossip of that time that a "distinguished physician" declared that he would have kept a fourth ex-President alive to die on a Fourth of July, had the illustrious sick man been under his treatment. The patient himself, had he been consulted, might, in that case, possibly have declined to have a fatal illness prolonged a week to gratify the public fondness for patriotic coincidence. But Mr. Adams's appropriation of another anniversary answered all[3] the purpose, for that he made a mistake as to the date does not seem to have been discovered.

It was accidental that Port Conway was the birthplace of Madison. His maternal grandfather, whose name was Conway, had a plantation at that place, and young Mrs. Madison happened to be there on a visit to her mother when her first child, James, was born. In the stately—not to say stilted—biography of him by William C. Rives, the christened name of this lady is given as Eleanor. Mr. Rives may have thought it not in accordance with ancestral dignity that the mother of so distinguished a son should have been burdened with so commonplace and homely a name as Nelly. But we are afraid it is true that Nelly was her name. No other biographer than Mr. Rives, that we know of, calls her Eleanor. Even Madison himself permits "Nelly" to pass under his eyes and from his hands as his mother's name.

In 1833-34 there was some correspondence between him and Lyman C. Draper, the historian, which includes some notes upon the Madison genealogy. These, the ex-President writes, were "made out by a member of the family," and they may be considered, therefore, as having his sanction. The first record is, that "James Madison was the son of James Madison and Nelly Conway." On such authority Nelly, and not Eleanor, must be accepted as the mother's name. This, of course, is to be regretted from the Rives point of view; but perhaps the name had a less[4] familiar sound a century and a half ago; and no doubt it was chosen by her parents without a thought that their daughter might go into history as the mother of a President, or that any higher fortune could befall her than to be the respectable head of a tobacco planter's family on the banks of the Rappahannock.

This genealogical record further says that "his [Madison's] ancestors, on both sides, were not among the most wealthy of the country, but in independent and comfortable circumstances." If this comment was added at the ex-President's own dictation, it was quite in accordance with his unpretentious character.[1] One might venture to say [5]as much of a Northern or a Western farmer. But they did not farm in Virginia; they planted. Mr. Rives says that the elder James was "a large landed proprietor;" and he adds, "a large landed estate in Virginia ... was a mimic commonwealth, with its foreign and domestic relations, and its regular administrative hierarchy." The "foreign relations" were the shipping, once a year, a few hogsheads of tobacco to a London factor; the "mimic commonwealths" were clusters of negro huts; and the "administrative hierarchy" was the priest, who was more at home at the tavern or a horse-race than in the discharge of his clerical duties.

As Mr. Madison had only to say of his immediate ancestors—which seems to be all he knew about them—that they were in "independent and comfortable circumstances," so he was, apparently, as little inclined to talk about himself; even at that age when it is supposed that men who have enjoyed celebrity find their own lives the most agreeable of subjects. In answer to Dr. Draper's inquiries he wrote this modest letter, now for the first time published:[6]—

Dear Sir,—Since your letter of the 3d of June came to hand, my increasing age and continued maladies, with the many attentions due from me, had caused a delay in acknowledging it, for which these circumstances must be an apology, in your case, as I have been obliged to make them in others.

You wish me to refer you to sources of printed information on my career in life, and it would afford me pleasure to do so; but my recollection on the subject is very defective. It occurs [to me] that there was a biographical volume in an enlarged edition compiled by General or Judge Rodgers of Pennsylvania, and which may perhaps have included my name, among others. When or where it was published I cannot say. To this reference I can only add generally the newspapers at the seat of government and elsewhere during the electioneering periods, when I was one of the objects under review. I need scarcely remark that a life, which has been so much a public life, must of course be traced in the public transactions in which it was involved, and that the most important of them are to be found in documents already in print, or soon to be so.

Lyman C. Draper, Lockport, N. Y.

The genealogical statement, it will be observed, does not go farther back than Mr. Madison's great-grandfather, John. Mr. Rives supposes that this John was the son of another John who, as "the pious researches of kindred have ascertained," took out a patent for land about 1653 between the North and York rivers on the shores of Chesa[7]peake Bay. The same writer further assumes that this John was descended from Captain Isaac Madison, whose name appears "in a document in the State Paper Office at London containing a list of the Colonists in 1623." From Sainsbury's Calendar[2] we learn something more of this Captain Isaac than this mere mention. Under date of January 24, 1623, there is this record: "Captain Powell, gunner, of James City, is dead; Capt. Nuce (?), Capt. Maddison, Lieut. Craddock's brother, and divers more of the chief men reported dead." But either the report was not altogether true or there was another Isaac Maddison, for the name appears among the signatures to a letter dated about a month later—February 20—from the governor, council, and Assembly of Virginia to the king. It is of record, also, that four months later still, on June 4, "Capt. Isaac and Mary Maddison" were before the governor and council as witnesses in the case of Greville Pooley and Cicely Jordan, between whom there was a "supposed contract of marriage," made "three or four days after her husband's death." But the lively widow, it seems, afterward "contracted herself to Will Ferrar before the governor and council, and disavowed the former contract," and the case therefore became so complicated that the court was "not able to decide [8]so nice a difference." What Captain Isaac and Mary Maddison knew about the matter the record does not tell us; but the evidence is conclusive that if there was but one Isaac Maddison in Virginia in 1623 he did not die in January of that year. Probably there was but one, and he, as Rives assumes, was the Captain Madyson of whose "achievement," as Rives calls it, there is a brief narrative in John Smith's "General History of Virginia."

Besides the record in Sainsbury's Calendar of the rumor of the death of this Isaac in Virginia, in January, 1623, his signature to a letter to the king in February, and his appearance as a witness before the council in the case of the widow Jordan, in June, it appears by Hotten's Lists of colonists, taken from the Records in the English State Paper Department, that Captain Isacke Maddeson and Mary Maddeson were living in 1624 at West and Sherlow Hundred Island. The next year, at the same place, he is on the list of dead; and there is given under the same date "The muster of Mrs. Mary Maddison, widow, aged 30 years." Her family consisted of "Katherin Layden, child, aged 7 years," and two servants. Katherine, it may be assumed, was the daughter of the widow Mary and Captain Isaac, and their only child. These "musters," it should be said, appear always to have been made with great care, and there is therefore hardly a possibility that a son, if there were one, was omitted in the numer[9]ation of the widow's family, while the name and age of the little girl, and the names and ages of the two servants, the date of their arrival in Virginia, and the name of the ship that each came in, are all carefully given. The conclusion is inevitable: Isaac Maddison left no male descendants, and President Madison's earliest ancestor in Virginia, if it was not his great-grandfather John, must be looked for somewhere else.

Mr. Rives knew nothing of these Records. His first volume was published before either Sainsbury's Calendar or Hotten's Lists; and the researches on which he relied, "conducted by a distinguished member of the Historical Society of Virginia" in the English State Paper Office, were, so far as they related to the Madisons, incomplete and worthless. The family was not, apparently, "coeval with the foundation of the Colony," and did not arrive "among the earliest of the emigrants in the New World." That distinction cannot be claimed for James Madison, nor is there any reason for supposing that he believed it could be. He seemed quite content with the knowledge that so far back as his great-grandfather his ancestors had been respectable people, "in independent and comfortable circumstances."

Of his own generation there were seven children, of whom James was the eldest, and alone became of any note, except that the rest were reputable and contented people in their stations of life. A hundred years ago the Arcadian Virginia, for which[10] Governor Berkeley had thanked God so devoutly,—when there was not a free school nor a press in the province,—had passed away. The elder Madison resolved, so Mr. Rives tells us, that his children should have advantages of education which had not been within his own reach, and that they should all enjoy them equally. James was sent to a school where he could at least begin the studies which should fit him to enter college. Of the master of that school we know nothing except that he was a Scotchman, of the name of Donald Robertson, and that many years afterward, when his son was an applicant for office to Madison, then secretary of state, the pupil gratefully remembered his old master, and indorsed upon the application that "the writer is son of Donald Robertson, the learned Teacher in King and Queen County, Virginia."

The preparatory studies for college were finished at home under the clergyman of the parish, the Rev. Thomas Martin, who was a member of Mr. Madison's family, perhaps as a private tutor, perhaps as a boarder. It is quite likely that it was by the advice of this gentleman—who was from New Jersey—that the lad was sent to Princeton instead of to William and Mary College in Virginia. At Princeton, at any rate, he entered at the age of eighteen, in 1769; or, to borrow Mr. Rives's eloquent statement of the fact, "the young Virginian, invested with the toga virilis of anticipated manhood, we now see launched on that[11] disciplinary career which is to form him for the future struggles of life."

One of his biographers says that he shortened his collegiate term by taking in one year the studies of the junior and senior years, but that he remained another twelve-month at Princeton for the sake of acquiring Hebrew. On his return home he undertook the instruction of his younger brothers and sisters, while pursuing his own studies. Still another biographer asserts that he began immediately to read law, but Rives gives some evidence that he devoted himself to theology. This and his giving himself to Hebrew for a year point to the ministry as his chosen profession. But if we rightly interpret his own words, he had little strength or spirit for a pursuit of any sort. His first "struggle of life" was apparently with ill-health, and the career he looked forward to was a speedy journey to another world. In a letter to a friend (November, 1772) he writes: "I am too dull and infirm now to look out for extraordinary things in this world, for I think my sensations for many months have intimated to me not to expect a long or healthy life; though it may be better with me after some time; but I hardly dare expect it, and therefore have little spirit or elasticity to set about anything that is difficult in acquiring, and useless in possessing after one has exchanged time for eternity." In the same letter he assures his friend that he approves of his choice of history and morals as the subjects of his winter studies;[12] but, he adds, "I doubt not but you design to season them with a little divinity now and then, which, like the philosopher's stone in the hands of a good man, will turn them and every lawful acquirement into the nature of itself, and make them more precious than fine gold."

The bent of his mind at this time seems to have been decidedly religious. He was a diligent student of the Bible, and, Mr. Rives says, "he explored the whole history and evidences of Christianity on every side, through clouds of witnesses and champions for and against, from the fathers and schoolmen down to the infidel philosophers of the eighteenth century." So wide a range of theological study is remarkable in a youth of only two or three and twenty years of age; but, remembering that he was at this time living at home, it is even more remarkable that in the house of an ordinary planter in Virginia a hundred and twenty years ago could be found a library so rich in theology as to admit of study so exhaustive. But in Virginia history nothing is impossible.

His studies on this subject, however, whether wide or limited, bore good fruit. Religious intolerance was at that time common in his immediate neighborhood, and it aroused him to earnest and open opposition; nor did that opposition cease till years afterward, when freedom of conscience was established by law in Virginia, largely by his labors and influence. Even in 1774, when all the colonies were girding themselves for the coming[13] revolutionary conflict, he turned aside from a discussion of the momentous question of the hour, in a letter to his friend[3] in Philadelphia, and exclaimed with unwonted heat:—

"But away with politics!... That diabolical, hell-conceived principle of persecution rages among some; and, to their eternal infamy, the clergy can furnish their quota of imps for such purposes. There are at this time in the adjacent country not less than five or six well-meaning men in close jail for publishing their religious sentiments, which in the main are very orthodox. I have neither patience to hear, talk, or think of anything relative to this matter; for I have squabbled and scolded, abused and ridiculed so long about it to little purpose that I am without common patience."

These are stronger terms than the mild-tempered Madison often indulged in. But he felt strongly. Probably he, no more than many other wiser and older men, understood what was to be the end of the political struggle which was getting so earnest; but evidently in his mind it was religious rather than civil liberty which was to be guarded. "If the Church of England," he says in the same letter, "had been the established and general religion in all the Northern colonies, as it has been among us here, and uninterrupted harmony had prevailed throughout the continent, it is [14]clear to me that slavery and subjection might and would have been gradually insinuated among us."

He congratulated his friend that they had not permitted the tea-ships to break cargo in Philadelphia; and Boston, he hoped, would "conduct matters with as much discretion as they seem to do with boldness." These things were interesting and important; but "away with politics! Let me address you as a student and philosopher, and not as a patriot." Shut off from any contact with the stirring incidents of that year in the towns of the coast, he lost something of the sense of proportion. To a young student, solitary, ill in body, perhaps a trifle morbid in mind, a little discontented that all the learning gained at Princeton could find no better use than to save schooling for the six youngsters at home,—to him it may have seemed that liberty was more seriously threatened by that outrage, under his own eyes, of "five or six well-meaning men in close jail for publishing their religious sentiments," than by any tax which Parliament could contrive. Not that he overestimated the importance of this wrong, but that he underestimated the importance of that. He was not long, however, in getting the true perspective.

Madison's place, both from temperament and from want of physical vigor, was in the council, not in the field. One of his early biographers says that he joined a military company, raised in his own county, in preparation for war; but this, there can hardly be a doubt, is an error. He speaks with enthusiasm of the "high-spirited" volunteers, who came forward to defend "the honor and safety of their country;" but there is no intimation that he chose for himself that way of showing his patriotism. But of the Committee of Safety, appointed in his county in 1774, he was made a member,—perhaps the youngest, for he was then only twenty-three years old.

Eighteen months afterward he was elected a delegate to the Virginia Convention of 1776, and this he calls "my first entrance into public life." It gave him also an opportunity for some distinction, which, whatever may have been his earlier plans, opened public life to him as a career. The first work of the convention was to consider and adopt a series of resolutions instructing the Virginian delegates in the Continental Congress, then[16] in session at Philadelphia, to urge an immediate declaration of independence. The next matter was to frame a Bill of Rights and a Constitution of government for the province. Madison was made a member of the committee to which this latter subject was referred. One question necessarily came up for consideration which had for him a peculiar interest, and in any discussion of which he, no doubt, felt quite at ease. This was concerning religious freedom. An article in the proposed Declaration of Rights provided that "all men should enjoy the fullest toleration in the exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience, unpunished and unrestrained by the magistrate, unless, under color of religion, any man disturb the peace, happiness, or safety of society." It does not appear that Mr. Madison offered any objection to the article in the committee; but when the report was made to the convention he moved an amendment. He pointed out the distinction between the recognition of an absolute right and the toleration of its exercise; for toleration implies the power of jurisdiction. He proposed, therefore, instead of providing that "all men should enjoy the fullest toleration in the exercise of religion," to declare that "all men are equally entitled to the full and free exercise of it according to the dictates of conscience;" and that "no man or class of men ought, on account of religion, to be invested with peculiar emoluments or privileges, nor subjected to any penalties or disabilities, unless, under color of[17] religion, the preservation of equal liberty and the existence of the state be manifestly endangered." This distinction between the assertion of a right and the promise to grant a privilege only needed to be pointed out. But Mr. Madison evidently meant more; he meant not only that religious freedom should be assured, but that an Established Church, which, as we have already seen, he believed to be dangerous to liberty, should be prohibited. Possibly the convention was not quite ready for this latter step; or possibly its members thought that, as the greater includes the less, should freedom of conscience be established a state church would be impossible, and the article might therefore be stripped of supererogation and verbiage. At any rate, it was reduced one half, and finally adopted in this simpler form: "That religion, or the duty we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and, therefore, all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion according to the dictates of conscience." Thus it stands to this day in the Bill of Rights of Virginia, and of other States which subsequently made it their own, possessing for us the personal interest of being the first public work of the coming statesman.

Madison was thenceforth for the next forty years a public man. Of the first Assembly under the new Constitution he was elected a member. For the next session also he was a candidate, but[18] failed to be returned for a reason as creditable to him as it was uncommon then, whatever it may be now, in Virginia. "The sentiments and manners of the parent nation," Mr. Rives says, still prevailed in Virginia, "and the modes of canvassing for popular votes in that country were generally practiced. The people not only tolerated, but expected and even required, to be courted and treated. No candidate who neglected those attentions could be elected." But the times, Mr. Madison thought, seemed "to favor a more chaste mode of conducting elections," and he "determined to attempt, by an example, to introduce it." He failed signally; "the sentiments and manners of the parent nation" were too much for him. He solicited no votes; nobody got drunk at his expense; and he lost the election. An attempt was made to contest the return of his opponent on the ground of corrupt influence, but, adds Mr. Rives, in his sesquipedalian measure, "for the want of adequate proof to sustain the allegations of the petition which in such cases it is extremely difficult to obtain with the requisite precision, the proceeding was unavailing except as a perpetual protest, upon the legislative records of the country, against a dangerous abuse, of which one of her sons, so qualified to serve her, and destined to be one of her chief ornaments, was the early though temporary victim." Mr. Rives does not mean that Mr. Madison was for a little while in early life the victim of a vicious habit, but that he lost votes because he would do nothing to encourage it in others.

[19]The country lost a good representative, but their loss was his gain. The Assembly immediately elected him a member of the governor's council, and in this position he so grew in public favor that, two years afterward (1780), he was chosen as a delegate to the Continental Congress. He was still under thirty, and had he been even a more brilliant young man than he really was, it would not have been to his discredit had he only been seen for the next year or two, if seen at all, in the background. He had taken his seat among men, every one of whom, probably, was his senior, and among whom were many of the wisest men in the country, not "older" merely, but "better soldiers."

If not the darkest, at least there was no darker year in the Revolution than that of 1780. Within a few days of his arrival at Philadelphia, Madison wrote to Jefferson—then governor of Virginia—his opinion of the state of the country. It was gloomy but not exaggerated. The only bright spot he could see was the chance that Clinton's expedition to South Carolina might be a failure; but within little more than a month from the date of his letter, Lincoln was compelled to surrender Charleston, and the whole country south of Virginia seemed about to fall into the hands of the enemy. Could he have foreseen that calamity, his apprehensions might have been changed to despair; for he writes:[20]—

"Our army threatened with an immediate alternative of disbanding or living on free quarter; the public treasury empty; public credit exhausted, nay, the private credit of purchasing agents employed, I am told, as far as it will bear; Congress complaining of the extortion of the people, the people of the improvidence of Congress, and the army of both; our affairs requiring the most mature and systematic measures, and the urgency of occasions admitting only of temporary expedients, and these expedients generating new difficulties; Congress recommending plans to the several States for execution, and the States separately rejudging the expediency of such plans, whereby the same distrust of concurrent exertions that had damped the ardor of patriotic individuals must produce the same effect among the States themselves; an old system of finance discarded as incompetent to our necessities, an untried and precarious one substituted, and a total stagnation in prospect between the end of the former and the operation of the latter. These are the outlines of the picture of our public situation. I leave it to your own imagination to fill them up."

He saw more clearly, perhaps, after the experience of one session of Congress, the true cause of all these troubles; at any rate, he was able, in a letter written in November of that year (1780), to state it tersely and explicitly. The want of money, he wrote to a friend, "is the source of all our public difficulties and misfortunes. One or two millions of guineas properly applied would diffuse vigor and satisfaction throughout the whole military department, and would expel the enemy from every part of the United States."

[21]But nobody knew better than he the difficulty of raising funds except by borrowing abroad, and that this was a precarious reliance. There must be some sort of substitute for money. In specific taxation he had no faith. Such taxes, if paid at all, would be paid, virtually, in the paper currency or certificates of the States, and these had already fallen to the ratio of one hundred to one; they kept on falling till they reached the rate of a thousand to one, and then soon became altogether worthless. When the estimate for the coming year was under consideration, he proposed to Congress that the States should be advised to abandon the issue of this paper currency. "It met," he says, "with so cool a reception that I did not much urge it." The sufficient answer to the proposition was, that "the practice was manifestly repugnant to the Acts of Congress," and as these were disregarded and could not be enforced, a mere remonstrance would be quite useless. The Union was little more than a name under the feeble bonds of the Confederation, and each State was a law unto itself. Not that in this case there was much reasonable ground for complaint; for what else could the States do? Where there was no money there must be something to take its place; a promise to pay must be accepted instead of payment. The paper answered a temporary purpose, though it was plain that in the end it would be good for nothing.

The evil, however, was manifestly so great that[22] there was only the more reason for trying to mitigate it, if it could not be cured. Madison, like the rest, had his remedy. He proposed, in a letter to one of his colleagues, that the demand for army supplies should be duly apportioned among the people, their collection rigorously enforced, and payment made in interest-bearing certificates, not transferable, but to be redeemed at a specified time after the war was over. The plan would undoubtedly have put a stop to the circulation of a vast volume of paper money if the producers would have exchanged the products of their labor for certificates, useless at the time of exchange, and having only a possible prospective value in case of the successful termination of an uncertain war. Patriotic as the people were, they neither would nor could have submitted to such a law, nor had Congress the power to enforce it. But Mr. Madison did not venture apparently to urge his plan beyond its suggestion to his colleague.

Why the Assembly of Virginia should have proposed to elect an extra delegate to Congress, early in 1781, is not clear, unless it be that one of the number, Joseph Jones, being also a member of the Assembly, passed much of his time in Richmond. It does not appear, however, that the delegate extraordinary was ever sent, perhaps because it was known to Mr. Madison's friends that it would be a mortification to him. There was certainly no good reason for any distrust of either his ability or his industry. One could hardly be otherwise[23] than industrious who had it in him—if the story be true—to take but three hours out of the twenty-four for sleep during the last year of his college course, that he might crowd the studies of two years into one. He seemed to love work for its own sake, and he was a striking example of how much virtue there is in steadiness of pursuit. Not that he had at this time any special goal for his ambition. His aim seemed to be simply to do the best he could wherever he might be placed; to discharge faithfully, and to the best of such ability as he had, whatever duty was intrusted to him. His report of the proceedings in the congressional session of 1782-83, and the letters written during those years and the year before, show that he was not merely diligent but absorbed in the duties of his office.

He was more faithful to his constituents than his constituents sometimes were to him. Anything that might happen at that period for want of money can hardly be a matter of surprise; but Virginia, even then, should have been able, it would seem, to find enough to enable its members of Congress to pay their board-bills. He complains gently in his Addisonian way of the inconvenience to which he was put for want of funds. "I cannot," he writes to Edmund Randolph, "in any way make you more sensible of the importance of your kind attention to pecuniary remittances for me, than by informing you that I have for some time past been a pensioner on the favor of Hayne[24] Solomon, a Jew broker." A month later he writes, that to draw bills on Virginia has been tried, "but in vain;" nobody would buy them; and he adds, "I am relapsing fast into distress. The case of my brethren is equally alarming." Within a week he again writes: "I am almost ashamed to reiterate my wants so incessantly to you, but they begin to be so urgent that it is impossible to suppress them." But the Good Samaritan, Solomon, is still an unfailing reliance. "The kindness of our little friend in Front Street, near the coffee house, is a fund which will preserve me from extremities; but I never resort to it without great mortification, as he obstinately rejects all recompense. The price of money is so usurious that he thinks it ought to be extorted from none but those who aim at profitable speculations. To a necessitous delegate he gratuitously spares a supply out of his private stock." It is a pretty picture of the simplicity of the early days of the Republic. Between the average modern member and the money-broker, under such circumstances, there would lurk, probably, a contract for carrying the mails or for Indian supplies.

Relief, however, came at last. An appeal was made in a letter to the governor of Virginia, which was so far public that anybody about the executive office might read it. The answer to this letter, says Mr. Madison, "seems to chide our urgency." But there soon came a bill for two hundred dollars, which, he adds, "very seasonably enabled me to replace a loan by which I had an[25]ticipated it. About three hundred and fifty more (not less) would redeem me completely from the class of debtors." It is to be hoped it came without further chiding.[4]

The young member was not less attentive to his congressional duties because of these little difficulties in the personal ways and means. Military movements seem, without altogether escaping his attention, to have interested him the least. In his letters to the public men at home, which were meant in some degree to give such information as in later times the newspapers supplied, questions relating to army affairs, even news directly from the army, occupy the least space. They are not always, for that reason, altogether entertaining reading. One would be glad, occasionally, to exchange their sonorous and rounded periods for any expression of quick, impulsive feeling. "I return you," he writes to Pendleton, "my fervent congratulations on the glorious success of the combined armies at York and Gloucester. We have had from the Commander-in-Chief an official report of the fact,"—and so forth and so forth; and then for a page or more is a discussion of the condition of British possessions in the East Indies, that "rich [26]source of their commerce and credit, severed from them, perhaps forever;" of "the predatory conquest of Eustatia;" and of the "relief of Gibraltar, which was merely a negative advantage;"—all to show that "it seems scarcely possible for them much longer to shut their ears against the voice of peace." There is not a word in all this that is not quite true, pertinent, reflective, and becoming a statesman; but neither is there a word of sympathetic warmth and patriotic fervor which at that moment made the heart of a whole people beat quicker at the news of a great victory, and in the hope that the cause was gained at last.

All the letters have this preternatural solemnity, as if each was a study in style after the favorite Addisonian model. One wonders if he did not, in the privacy of his own room and with the door locked, venture to throw his hat to the ceiling and give one hurrah under his breath at the discomfiture of the vain and self-sufficient Cornwallis. But he seems never to have been a young man. At one and twenty he gravely warned his friend Bradford not "to suffer those impertinent fops that abound in every city to divert you from your business and philosophical amusements.... You will make them respect and admire you more by showing your indignation at their follies, and by keeping them at a becoming distance." It was his loss, however, and our gain. He was one of the men the times demanded, and without whom they would have been quite different times and followed[27] by quite different results. The sombre hue of his life was due partly, no doubt, to natural temperament; partly to the want of health in his earlier manhood, which led him to believe that his days were numbered; but quite as much, if not more than either, to a keen sense of the responsibility resting upon those to whom had fallen the conduct of public affairs.

Madison had grown steadily in the estimation of his colleagues, as is shown, especially in 1783, by the frequency of his appointment upon important committees. He was a member of that one to which was intrusted the question of national finances, and it is plain, even in his own modest report of the debates of that session, that he took an important part in the long discussions of the subject, and exercised a marked influence upon the result. The position of the government was one of extreme difficulty. To tide over an immediate necessity, a further loan had been asked of France in 1782, and bills were drawn against it without waiting for acceptance. It was not very likely, but it was not impossible, that the bills might go to protest; but even should they be honored, so irregular a proceeding was a humiliating acknowledgment of poverty and weakness, to which some of the delegates, Mr. Madison among them, were extremely sensitive.

The national debt altogether was not less than forty million dollars. To provide for the interest on this debt, and a fund for expenses, it was[29] necessary to raise about three million dollars annually. But the sum actually contributed for the support of the confederate government in 1782 was only half a million dollars. This was not from any absolute inability on the part of the people to pay more; for the taxes before the war were more than double that sum, and for the first three or four years of the war it was computed that, with the depreciation of paper money, the people submitted to an annual tax of about twenty million dollars. The real difficulty lay in the character of the Confederation. Congress might contrive but it could not command. The States might agree, or they might disagree, or any two or more of them might only agree to disagree; and they were more likely to do either of the last two than the first. There was no power of coercion anywhere. All that Congress could do was to try to frame laws that would reconcile differences, and bring thirteen supreme governments upon some common ground of agreement. To distract and perplex it still more, it stood face to face with a well-disciplined and veteran army which might at any moment, could it find a leader to its mind, march upon Philadelphia and deal with Congress as Cromwell dealt with the Long Parliament. There were some men, probably, in that body, who would not have been sorry to see that precedent followed. Washington might have done it if he would. Gates probably would have done it if he could.

To avert this threatened danger; to contrive[30] taxation that should so far please the taxed that they would refrain from using the power in their hands to escape altogether any taxation for general purposes,—was the knotty problem this Congress had to solve in order to save the Confederacy from dissolution. There was no want of plans and expedients; neither were there wanting men in that body who clearly understood the conditions of the problem, and how it might be solved, and whose aim was direct and unfaltering. Chief among them were Hamilton, Wilson, Ellsworth, and Madison. However wrong-headed, or weak, or intemperate others may have been, these men were usually found together on important questions; differing sometimes in details, but unmoved by passion or prejudice, and strong from reserved force, they overwhelmed their opponents at the right moment with irresistible argument and by weight of character.

In the discussion of the more important questions Mr. Madison is conspicuous—conspicuous without being obtrusive. A reader of the debates can hardly fail to be struck with his familiarity with English constitutional law, and its application to the necessities of this offshoot of the English people in setting up a government for themselves. The stores of knowledge he drew upon must needs have been laid up in the years of quiet study at home before he entered upon public life. For there was no congressional library then where a member could "cram" for debate; and—though[31] Philadelphia already had a fair public library—the member who was armed at all points must have equipped himself before entering Congress. In this respect Madison probably had no equal, except Hamilton, and possibly Ellsworth. To the need of such a library, however, he and others were not insensible. As chairman of a committee he reported a list of books "proper for the use of Congress," and advised their purchase. The report declared that certain authorities upon international law, treaties, negotiations, and other questions of legislation were absolutely indispensable, and that the want of them "was manifest in several Acts of Congress." But the Congress was not to be moved by a little thing of that sort.

The attitude of his own State sometimes embarrassed him in the satisfactory discharge of his duty as a legislator. The earliest distinction he won after entering Congress was as chairman of a committee to enforce upon Mr. Jay, then minister to Spain, the instructions to adhere tenaciously to the right of navigation on the Mississippi in his negotiations for an alliance with that power. Mr. Madison, in his dispatch, maintained the American side of the question with a force and clearness to which no subsequent discussion of the subject ever added anything. He left nothing unsaid that could be said to sustain the right either on the ground of expediency, of national comity, or of international law; and his arguments were not only in accordance with his own convictions, but[32] with the instructions of the Assembly of his own State. It was a question of deep interest to Virginia, whose western boundary at that time was the Mississippi. But Virginia soon afterward shifted her position. The course of the war in the Southern States in the winter of 1780-81 aroused in Georgia and the Carolinas renewed anxiety for an alliance with Spain. The fear of their people was that, in case of the necessity for a sudden peace while the British troops were in possession of those States or parts of them, they might be compelled to remain as British territory under the application of the rule of uti possidetis. It was urged, therefore, that the right to the Mississippi should be surrendered to Spain, if it were made the condition of an alliance. In deference to her neighbors, Virginia proposed that Mr. Jay should be reinstructed accordingly.

Mr. Madison was not in the least shaken in his conviction. With him, the question was one of right rather than of expediency. But not many at that time ventured to doubt that representatives must implicitly obey the instructions of their constituents. He yielded; but not till he had appealed to the Assembly to reconsider their decision. The scale was turned; in deference to the wishes of the Southern States new orders were sent to Mr. Jay. Mr. Madison, however, had not long to wait for his justification. When the immediate danger, which had so alarmed the South, had passed away, Virginia returned to her original[33] position. New instructions were again sent to her representatives, and Mr. Jay was once more advised by Congress that on the Mississippi question his government would yield nothing.

On another question, two years afterward, Mr. Madison refused to accept a position of inconsistency in obedience to instructions which his State attempted to force upon him. No one saw more clearly than he how absolutely necessary to the preservation of the Confederacy was the settlement of its financial affairs on some sound and just basis; and no one labored more earnestly and more intelligently than he to bring about such a settlement. Congress had proposed in 1781 a tax upon imports, each State to appoint its own collectors, but the revenue to be paid over to the federal government to meet the expenses of the war. Rhode Island alone, at first, refused her assent to this scheme. An impost law of five per cent. upon certain imports and a specific duty upon others for twenty-five years were an essential part of the plan of 1783 to provide a revenue to meet the interest on the public debt and for other general purposes. That Rhode Island would continue obstinate on this point was more than probable; and the only hope of moving her was that she should be shamed or persuaded into compliance by the combined influence of all the other States.

Mr. Madison was as bitter as he could ever be in his reflections upon that State, whose course,[34] he thought, showed a want of any sense of honor or of patriotism. Virginia, he argued, should rebuke her by making her own compliance with the law the more emphatic, as an example for all the rest. But Virginia did exactly the other thing. At the moment when debate upon the revenue law was the most earnest, and the prospect of carrying it the most hopeful; when a committee appointed by Congress had already started on their journey northward to expostulate with, and if possible conciliate, Rhode Island,—at that critical moment came news from Virginia that she had revoked her assent of a previous session to the impost law. This was equivalent to instructing her delegates in Congress to oppose any such measure. The situation was an awkward one for a representative who had put himself among the foremost of those who were pushing this policy, and who had been making invidious reflections upon a State which opposed it. The rule that the will of the constituents should govern the representative, he now declared, had its exceptions, and here was a case in point. He continued to enforce the necessity of a general law to provide a revenue, though his arguments were no longer pointed with the selfishness and want of patriotism shown by the people of Rhode Island. In the end his firmness was justified by Virginia, who again shifted her position when the new act was submitted to her.

The operation of the law was limited to five and twenty years. This Hamilton opposed and Madi[35]son supported; and in this difference some of the biographers of both see the foreshadowing of future parties. But it is more likely that neither of those statesmen thought of their difference of opinion as difference of principle. The question was, whether anything could be gained by a deference to that party which, both felt at that time, threatened to throw away, in adhering to the state-rights doctrine, all that was gained by the Revolution. They were agreed upon the necessity of a general law, supreme in all the States, to meet the obligation of a debt contracted for the general good. Unless—wrote Madison in February—"unless some amicable and adequate arrangements be speedily taken for adjusting all the subsisting accounts and discharging the public engagements, a dissolution of the Union will be inevitable." He was willing, therefore, to temporize, that the necessary assent of the State to such a law might be gained. Nobody hoped that the public debt would be paid off in twenty-five years; but to assume to levy a federal tax in the States for a longer period, or till the debt should be discharged, might so arouse state jealousy that it would be impossible to get an assent to the law anywhere. If the law for twenty-five years should be accepted, the threatened destruction of the government would be escaped for the present, and it might, at the end of a quarter of a century, be easy to reënact the law. At any rate, the evil day would be put off. This was Madison's reasoning.

[36]But Hamilton did not believe in putting off a crisis. He had no faith in the permanency of the government as then organized. If he were right, what was the use or the wisdom of postponing a catastrophe till to-morrow? A possible escape from it might be even more difficult to-morrow than to-day. The essential difference between the two men was, that Madison only feared what Hamilton positively knew, or thought he knew. It was a difference of faith. Madison hoped something would turn up in the course of twenty-five years. Hamilton did not believe that anything good could turn up under the feeble rule of the Confederation. He would have presented to the States, then and there, the question, Would they surrender to the confederate government the right of taxation so long as that government thought it necessary? If not, then the Confederation was a rope of sand, and the States had resolved themselves into thirteen separate and independent governments. Therefore he opposed the condition of twenty-five years, and voted against the bill.

Nevertheless, when it became the law he gave it his heartiest support, and was appointed one of a committee of three to prepare an address, which Madison wrote, to commend it to the acceptance of the States. Indeed, the last serious effort made on behalf of the measure was made by Hamilton, who used all his eloquence and influence to induce the legislature of his own State to ratify it. It was the law against his better judgment; but[37] being the law, he did his best to secure its recognition. But it failed of hearty support in most of the States, while in New York and Pennsylvania compliance with it was absolutely refused. Nothing, therefore, would have been lost had Hamilton's firmness prevailed in Congress; and nothing was gained by Madison's deference to the doctrine of state rights, unless it was that the question of a "more perfect Union" was put off to a more propitious time, when a reconstruction of the government under a new federal Constitution was possible. Meanwhile Congress borrowed the money to pay the interest on money already borrowed; the confederate government floundered deeper and deeper into inextricable difficulties; the thirteen ships of state drifted farther and farther apart, with a fair promise of a general wreck.

But the bill contained another compromise which was not temporary, and once made could not be easily unmade. Agreed to now, it became a condition of the adoption of the federal Constitution four years later; and there, as nobody now is so blind as not to see, it was the source of infinite mischief for nearly a century, till a third reconstruction of the Union was brought about by the war of 1861-65. The Articles of Confederation required that "all charges of war and all other expenses that shall be incurred for the common defense or general welfare" should be borne by the States in proportion to the value of their lands. It was proposed to amend this provision[38] of the Constitution, and for lands substitute population, exclusive of Indians not taxed, as the basis for taxation. But here arose at once a new and perplexing question. There were, chiefly in one portion of the country, about 750,000 "persons held to service or labor,"—the euphuism for negro slaves which, evolved from some tender and sentimental conscience, came into use at this period. Should these, recognized only as property by state law, be counted as 750,000 persons by the laws of the United States?[5] Or should they, in the enumeration of population, be reckoned, in accordance with the civil law, as pro nullis, pro mortuis, pro quadrupedibus, and therefore not to be counted at all? Or should they, as those who owned them insisted, be counted, if included in the basis of taxation, as fractions of persons only?

The South contended that black slaves were not equal to white men as producers of wealth, and that, by counting them as such, taxation would be unequal and unjust. But whether counted as units or as fractions of units, the slaveholders insisted that representation should be according to that enumeration. The Northern reply was that, if representation was to be according to population, the slaves being included, then the slave States would have a representation of property, for which there would be no equivalent in States where there were no slaves; but if slaves were enumerated as [39]a basis of representation, then that enumeration should also be taken to fix the rate of taxation.

Here, at any rate, was a basis for an interesting deadlock. One simple way out of it would have been to insist upon the doctrine of the civil law; to count the slaves only as pro quadrupedibus, to be left out of the enumeration of population as being no part of the State, as horses and cattle were left out. But the bonds of union hung loosely upon the sisters a hundred years ago; there was not one of them who did not think she was able to set up for herself and take her place among the nations as an independent sovereign; and it is more than likely that half of them would have refused to wear those bonds any longer on such a condition. There was no apprehension then that slavery was to become a power for evil in the State; but there was intense anxiety lest the States should fly asunder, form partial and local unions among neighbors, or become entangled in alliances with foreign nations, at the sacrifice of all, or much, that was gained by the Revolution. To make any concession, therefore, to slavery for the sake of the Union was hardly held to be a concession.

The curious student of history, however, who loves to study those problems of what might have happened if events that did not happen had come to pass, will find ample room for speculation in the possibilities of this one. Had there been no compromise, it is as easy to see now, as it was easy[40] to foresee then, how quickly the feeble bond of union would have snapped asunder. But nevertheless, if the North had insisted that the slaves should neither be counted nor represented at all, or else should be reckoned in full and taxes levied accordingly, the consequent dissolution of the Confederacy might have had consequences which then nobody dreamed of. For it is not impossible, it is not even improbable, that, in that event, the year 1800 would have seen slavery in the process of rapid extinction everywhere except in South Carolina and Georgia. Had the event been postponed in those States to a later period, it would only have been because they had already found in the cultivation of indigo and rice a profitable use for slave-labor, which did not exist in the other slave States, where the supply of slaves was rapidly exceeding the demand. There can hardly be a doubt that, in case of the dissolution of the Confederacy, the Northern free-labor States would soon have consolidated into a strong union of their own. There was every reason for hastening it, and none so strong for hindering it as those which were overborne in the union which was actually formed soon afterward between the free-labor and slave-labor States. To such a Northern union the border States, as they sloughed off the old system, would have been naturally attracted; nor can there be a doubt that a federal union so formed would ultimately have proved quite as strong, quite as prosperous, quite as happy, and quite as[41] respectable among the nations, as one purchased by compromises with slavery, followed, as those compromises were, by three quarters of a century of bitter political strife ending in a civil war.

But the Northern members were no less ready to make compromises than Southern members were to insist upon them, these no more understanding what they conceded than those understood what they gained; for the future was equally concealed from both. A committee reported that two blacks should be rated as one free man. This was unsatisfactory. To some it seemed too large, to others too small. Other ratios, therefore, were proposed,—three to one, three to two, four to one, and four to three. Mr. Madison at last, "in order," as he said, "to give a proof of the sincerity of his professions of liberality,"—and doubtless he meant to be liberal,—proposed "that slaves should be rated as five to three." His motion was adopted, but afterward reconsidered. Four days later—April 1st—Mr. Hamilton renewed the proposition, and it was carried, Madison says, "without opposition."[6] The law on this point was the precedent for the mischievous three fifths rule of the Constitution adopted four years later.

[42]Youth finally overtook the young man during the last winter of his term in Congress, for he fell in love. But it was an unfortunate experience, and the outcome of it doubtless gave a more sombre hue than ever to his life. His choice was not a wise one. Probably Mr. Madison seemed a much older man than he really was at that period of his life, and to a young girl may have appeared really advanced in years. At any rate, it was his unhappy fate to be attached to a young lady of more than usual beauty and of irrepressible vivacity,—Miss Catherine Floyd, a daughter of General William Floyd of Long Island, N. Y., who was one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, and who was a delegate to Congress from 1774 to 1783. Miss Catherine's sixteenth birthday was in April of the latter year; Madison was double her age, as his thirty-second birthday was a month earlier. His suit, however, was accepted, and they became engaged. But it was the father rather than the daughter who admired the suitor; for the older statesman better understood the character, and better appreciated the abilities, of his young colleague, and predicted a brilliant career for him. The girl's wisdom was of another kind. The future career which she foresaw and wanted to share belonged to a young clergyman, who—according to the reminiscences of an aged relative of hers—"hung round her at the harpsichord," and made love in quite another fashion than that of the[43] solemn statesman whom the old general so approved of. It is altogether a pretty love story, and one's sympathy goes out to the lively young beauty, who was thinking of love and not of ambition, as she turned from the old young gentleman, discussing, with her wise father, the public debt and the necessity of an impost, to that really young young gentleman who knew how to hang over the harpsichord, and talked more to the purpose with his eyes than ever the other could with his lips. There is a tradition that she was encouraged to be thus on with the new love before she was off with the old, by a friend somewhat older than herself; and possibly this maturer lady may have thought that Madison would be better mated with one nearer his own age. At any rate, the engagement was broken off before long by the dismissal of the older lover, much to the father's disappointment, and in due time the young lady married the other suitor. There is no reason that I know of for supposing that she ever regretted that her more humble home was in a rectory, when it might have been, in due time, had she chosen differently, in the White House at Washington, and that afterward she might have lived, the remaining sixteen years of her life, the honored wife of a revered ex-President. Perhaps, however, she smiled in those later years at the recollection of having laughed in her gay and thoughtless youth at her solemn lover, and that, when at last she dismissed him, she sealed her[44] letter—conveying to him alone, it may be, some merry but mischievous meaning—with a bit of rye-dough.[7]

Mr. Rives gives a letter from Jefferson to Madison at this time, which shows that he stood in need of consolation from his friends. "I sincerely lament," Mr. Jefferson wrote in his philosophical way, "the misadventure which has happened, from whatever cause it may have happened. Should it be final, however, the world presents the same and many other resources of happiness, and you possess many within yourself. Firmness of mind and unintermitting occupation will not long leave you in pain. No event has been more contrary to my expectations, and these were founded on what I thought a good knowledge of the ground. But of all machines ours is the most complicated and inexplicable." It was Solomon who said, "there be three things which are too wonderful for me, yea, four which I know not." This fourth was, "the way of a man with a maid." He might have added a fifth,—the way of a maid with a man, which, evidently, is what Jefferson meant.

As the election of the same delegate to Congress for consecutive sessions was then forbidden by the law of Virginia, Mr. Madison was not returned to that body in 1784. For a brief interval of three months he made good use of his time, we are told, by continuing his law studies, till in the spring of that year he was chosen to represent his county in the Virginia Assembly. It may be that "the sentiments and manners of the parent nation," which he lamented seven years before, had passed away, and nobody now insisted upon the privilege of getting drunk at the candidate's expense before voting for him. But it is more likely that the electors had not changed. The difference was in the candidate; they did not need to be allured to give their votes to a man whom they were proud to call upon to represent the county. Mr. Madison's reputation was already made by his three years in Congress, and he now easily took a place among the political leaders of his own State.

The position was hardly less conspicuous or less influential than that which he had held in the national Congress. What each State might do[46] was of quite as much importance as anything the federal government might or could do. Congress could neither open nor close a single port in Virginia to commerce, whether domestic or foreign, without the consent of the State; it could not levy a tax of a penny on anything, whether goods coming in or products going out, if the State objected. As a member of Congress, Mr. Madison might propose or oppose any of these things; as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates, he might, if his influence was strong enough, carry or forbid any or all of them, whatever might be the wishes of Congress. It was in the power of Virginia to influence largely the welfare of her neighbors, so far as it depended upon commerce, and indirectly that of every State in the Union.

In the Assembly, as in Congress, Mr. Madison's aim was to increase the powers of the federal government, for want of which it was rapidly sinking into imbecility and contempt. "I acceded," he says, "to the desire of my fellow-citizens of the county that I should be one of its representatives in the legislature," to bring about "a rescue of the Union and the blessings of liberty staked on it from an impending catastrophe." Early in the session the Assembly assented to the amendment to the Articles of Confederation proposed at the late session of Congress, which substituted population for a land valuation as the basis of representation and of taxation. The Assembly also asserted that all requisitions upon the States for[47] the support of the general government and to provide for the public debt should be complied with, and payment of balances on old accounts should be enforced; and it assented to the recommendation of Congress that that body should have power for a limited period to control the trade with foreign nations having no treaty with the United States, in order that it might retaliate upon Great Britain for excluding American ships from her West India colonies. All these measures were designed for "the rescue of the Union," and they had, of course, Madison's hearty support. For it was absolutely essential, as he believed, that something should be done if the Union was to be saved, or to be made worth saving. But there were obstacles on all sides. The commercial States were reluctant to surrender the control over trade to Congress; in the planting States there was hardly any trade that could be surrendered. In Virginia the tobacco planter still clung to the old ways. He liked to have the English ship take his tobacco from the river bank of his own plantation, and to receive from the same vessel such coarse goods as were needed to clothe his slaves, with the more expensive luxuries for his own family,—dry goods for his wife and daughter; the pipe of madeira, the coats and breeches, the hats, boots, and saddles for himself and his sons. He knew that this year's crop went to pay—if it did pay—for last year's goods, and that he was always in debt. But the debt was on running account, and did not[48] matter. The London factor was skillful in charges for interest and commissions, and the account for this year was always a lien on next year's crop. He knew, and the planter knew, that the tobacco could be sold at a higher price in New York or Philadelphia than the factor got, or seemed to get, for it in London; that the goods sent out in exchange were charged at a higher price than they could be bought for in the Northern towns. Nevertheless, the planter liked to see his own hogsheads rolled on board ship by his own negroes at his own wharf, and receive in return his own boxes and bales shipped direct from London at his own order, let it cost what it might. It was a shiftless and ruinous system; but the average Virginia planter was not over-quick at figures, nor even at reading and writing. He was proud of being lord of a thousand or two acres, and one or two hundred negroes, and fancied that this was to rule over, as Mr. Rives called it, "a mimic commonwealth, with its foreign and domestic relations, and its regular administrative hierarchy." He did not comprehend that the isolated life of a slave plantation was ordinarily only a kind of perpetual barbecue, with its rough sports and vacuous leisure, where the roasted ox was largely wasted and not always pleasant to look at. There was a rude hospitality, where food, provided by unpaid labor, was cheap and abundant, and where the host was always glad to welcome any guest who would relieve him of his own tediousness; but there was little luxury and[49] no refinement where there was almost no culture. Of course there were a few homes and families of another order, where the women were refined and the men educated; but these were the exceptions. Society generally, with its bluff, loud, self-confident but ignorant planters, its numerous poor whites destitute of lands and of slaves, and its mass of slaves whose aim in life was to avoid work and escape the whip, was necessarily only one remove from semi-civilization.

It was not easy to indoctrinate such a people, more arrogant than intelligent, with new ideas. By the same token it might be possible to lead them into new ways before they would find out whither they were going. Mr. Madison hoped to change the wretched system of plantation commerce by a port bill, which he brought into the Assembly. Imposts require custom-houses, and obviously there could not be custom-houses nor even custom-officers on every plantation in the State. The bill proposed to leave open two ports of entry for all foreign ships. It would greatly simplify matters if all the foreign trade of the State could be limited to these two ports only. It would then be easy enough to enforce imposts, and the State would have something to surrender to the federal government to help it to a revenue, if, happily, the time should ever come when all the States should assent to that measure of salvation for the Union. Not that this was the primary object of those who favored this port law; but the[50] question of commerce was the question on which everything hinged, and its regulation in each State must needs have an influence, one way or the other, upon the possibility of strengthening, even of preserving, the Union. Everything depended upon reconciling these state interests by mutual concessions. The South was jealous of the North, because trade flourished at the North and did not flourish at the South. It seemed as if this was at the expense of the South, and so, in a certain sense, it was. The problem was to find where the difficulty lay, and to apply the remedy.

If commerce flourished at the North, where each of the States had one or two ports of entry only, why should it not flourish in Virginia if regulated in the same way? If those centres of trade bred a race of merchants, who built their own ships, bought and sold, did their own carrying, competed with and stimulated each other, and encroached upon the trade of the South, why should not similar results follow in Virginia if she should confine her trade to two or three ports? If the buyer and the seller, the importer and the consumer, went to a common place of exchange in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, and prosperity followed as a consequence, why should they not do the same thing at Norfolk? This was what Madison aimed to bring about by the port bill. But it was impossible to get it through the legislature till three more ports were added to the two which the bill at first proposed. When the[51] planters came to understand that such a law would take away their cherished privilege of trade along the banks of the rivers, wherever anybody chose to run out a little jetty, the opposition was persistent. At every succeeding session, till the new federal Constitution was adopted, an attempt was made to repeal the act; and though that was not successful, each year new ports of entry were added. It did not, indeed, matter much whether the open ports of Virginia were two or whether they were twenty. There was a factor in the problem which neither Mr. Madison nor anybody else would take into the account. It was possible, of course, if force enough were used, to break up the traffic with English ships on the banks of the rivers; but when that was done, commerce would follow its own laws, in spite of the acts of the legislature, and flow into channels of its own choosing. It was not possible to transmute a planting State, where labor was enslaved, into a commercial State, where labor must be free.

However desirous Mr. Madison might be to transfer the power over commerce to the federal government, he was compelled, as a member of the Virginia legislature, to care first for the trade of his own State. No State could afford to neglect its own commercial interests so long as the thirteen States remained thirteen commercial rivals. It was becoming plainer and plainer every day that, while that relation continued, the less chance there was that thirteen petty, independent States could[52] unite into one great nation. No foreign power would make a treaty with a government which could not enforce that treaty among its own people. Neither could any separate portion of that people make a treaty, as any other portion, the other side of an imaginary line, need not hold it in respect. What good was there in revenue laws, or, indeed, in any other laws in Massachusetts which Connecticut and Rhode Island disregarded? or in New York, if New Jersey and Pennsylvania laughed at them? or in Virginia, if Maryland held them in contempt?

But Mr. Madison felt that, if he could bring about a healthful state of things in the trade of his own State, there was at least so much done towards bringing about a healthful state of things in the commerce of the whole country. There came up a practical, local question which, when the time came, he was quick to see had a logical bearing upon the general question. The Potomac was the boundary line between Virginia and Maryland; but Lord Baltimore's charter gave to Maryland jurisdiction over the river to the Virginia bank; and this right Virginia had recognized, claiming only for herself the free navigation of the Potomac and the Pocomoke. Of course the laws of neither State were regarded when it was worth while to evade them; and nothing was easier than to evade them, since to the average human mind there is no privilege so precious as a facility for smuggling. Nobody, at any rate, seems to have[53] thought anything about the matter till it came under Madison's observation after his return home from Congress. To him it meant something more than mere evasion of state laws and frauds on the state revenue. The subject fell into line with his reflections upon the looseness of the bonds that held the States together, and how unlikely it was that they would ever grow into a respectable or prosperous nation while their present relations continued. Virtually there was no maritime law on the Potomac, and hardly even the pretense of any. What could be more absurd than to provide ports of entry on one bank of a river, while on the other bank, from the source to the sea, the whole country was free to all comers? If the laws of either State were to be regarded on the opposite bank, a treaty was as necessary between them as between any two contiguous states in Europe.

Madison wrote to Jefferson, who was now a delegate in Congress, pointing out this anomalous condition of things on the Potomac, and suggesting that he should confer with the Maryland delegates upon the subject. The proposal met with Jefferson's approbation; he sought an interview with Mr. Stone, a delegate from Maryland, and, as he wrote to Madison, "finding him of the same opinion, [I] have told him I would, by letters, bring the subject forward on our part. They will consider it, therefore, as originated by this conversation." Why "they" should not have been permitted to "consider it as originated" from[54] Madison's suggestion that Jefferson should have such a conversation is not quite plain; for it was Madison, not Jefferson, who had discovered that here was a wrong that ought to be righted, and who had proposed that each State should appoint commissioners to look into the matter and apply a remedy. So, also, so far as subsequent negotiation on this subject had any influence in bringing about the Constitutional Convention of 1787, it was only because Mr. Madison, having suggested the first practical step in the one case, seized an opportune moment in that negotiation to suggest a similar practical step in the other case. As it is so often said that the Annapolis Convention of 1786 was the direct result of the discussion of the Potomac question, it is worth while to explain what they really had to do with each other.

The Virginia commissioners were appointed early in the session on Mr. Madison's motion. Maryland moved more slowly, and it was not till the spring of 1785 that the commissioners met. They soon found that any efficient jurisdiction over the Potomac involved more interests than they, or those who appointed them, had considered. Existing difficulties might be disposed of by agreeing upon uniform duties in the two States, and this the commissioners recommended. But when the subject came before the Maryland legislature it took a wider range.

The Potomac Company, of which Washington was president, had been chartered only a few[55] months before. The work it proposed to do was to make the upper Potomac navigable, and to connect it by a good road with the Ohio River. This was to encourage the settlement of Western lands. Another company was chartered about the same time to connect the Potomac and Delaware by a canal, where interstate traffic would be more immediate. Pennsylvania and Delaware must necessarily have a deep interest in both these projects, and the Maryland legislature proposed that those States be invited to appoint commissioners to act with those whom Maryland and Virginia had already appointed to settle the conflict between them upon the question of jurisdiction on the Potomac. Then it occurred to somebody: if four States can confer, why should not thirteen? The Maryland legislature thereupon suggested that all the States be invited to send delegates to a convention to take up the whole question of American commerce.