Title: Harper's Young People, June 22, 1880

Author: Various

Release date: May 31, 2009 [eBook #29009]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/29009

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire

| Vol. I.—No. 34. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | Price Four Cents. |

| Tuesday, June 22, 1880. | Copyright, 1880, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

RECESS AT THE ACADEMY.—Drawn by A. B. Shults.

RECESS AT THE ACADEMY.—Drawn by A. B. Shults.

aby, Bee, and Butterfly,

Underneath the summer sky.

Baby, bees, and birds together,

Happy in the pleasant weather;

Sunshine over all around,

In the sky, and on the ground;

Hiding, too, in Baby's eyes,

As he looks in mute surprise

At the sunbeams tumbling over

Merrily amid the clover,

Where the bees, at work all day,

Never find the time for play.

Happy little baby boy!

Tiny heart all full of joy;

Loving everything on earth,

As love welcomed him at birth;

Ever learning new delights,

Ever seeing pleasant sights;

Taking each day one step more

Than he ever took before.

Shine out, sunbeams, warm and bright,

Lengthen daytime, shorten night,

Till so wise he grows that he

Spells baby with a great big B.

One hundred and twenty years ago there lived a plain, honest farmer in the beautiful town of Woodstock, in the province of Connecticut, by the name of Eaton. He belonged to the fine, intelligent New England stock, and did his duty like a man in the state of life to which God had been pleased to call him, working on his farm in summer, and teaching school in winter; for he needed all he could earn to put bread in the mouths of his thirteen children, who were taught early to help themselves, after the fashion of their stalwart Anglo-Saxon forefathers. One of Farmer Eaton's boys, named William, was born February 23, 1764, and was a high-spirited, clever, reckless little chap, keeping his mother continually in a state of anxiety on his account; indeed, if she had not been so used to boys with their pranks and unlimited thirst for adventures, I think Bill would have been the death of her, for she never knew what he would be about next. For all his love of sport and out-door amusement, the boy was so fond of reading that he nearly always managed to conceal a book in his pocket when he went out to work in the fields or woods, and often, when left alone, or when his companions stopped for rest or meals, Bill would steal time to read. When his elders caught him at it he would often get soundly scolded for not being better employed, but the very next chance he would be at it again.

One Sunday, when he was ten years old, he was returning from church, and passing a tree laden with tempting red cherries, climbed up in his usual reckless fashion to help himself; but either the branch broke or he lost his footing, for he fell to the ground with such violence that he dislocated his shoulder, besides being so stunned that he lay senseless for several days after he was picked up and carried home. The neighbors came in to offer their services when they heard of the accident, for though they no doubt shook their heads and remarked, "I told you so," "I knew how it would be," they were, all the same, very kind to the poor little chap who lay there, white and death-like, for so many long hours.

A neighbor, who was a tanner by trade, was sitting by his bed when at last he opened his eyes. I suppose the tanner was glad enough to see the boy come to life again; but all he said was, "Do you love cherries, Bill?"

"Do you love hides?" spoke up Bill, as quick as a flash.

You see, he came to the full possession of his senses at once after his long sleep, and wasn't going to let himself be taken at a disadvantage by any tanner in the land.

When Eaton was twelve our country declared itself free and independent, and all true patriots rose up to defend, by sword or whatever other means was in their power, the sacred cause of liberty.

Our young friend Bill fairly burned with desire to go off and do something great. His soul was on fire with patriotic ardor. How could he stay quietly in Woodstock, and lead a humdrum life, when the soldiers of the tyrant were threatening all the Americans held most dear? But his friends at home did not encourage his practical patriotism. He was told that he must stay at home, and work on the farm, and get ready for college; the country would get on very well without him; and so he did stay for four years, and the war seemed no nearer an end than ever. At last one night he could stand it no longer; so he ran away, and joined the nearest camp, where he enlisted. But the pride of the sixteen-year-old boy received a blow: they made him servant to one of the officers, and in this menial position he was obliged to stay. He found that he was far from being his own master now. He behaved so well, though, that he was placed in the ranks after a while, and in 1783 was made a sergeant, and discharged.

He went home, and taught, to support himself, while he prepared for college; for he had no father now to help him along. He entered Dartmouth College, and graduated honorably, though he had lost five years for study out of his young life. Not long after his graduation, while he was teaching again, he was given a captain's commission in the army for his service during the Revolution. A soldier's life suited his bold character far better than the quiet occupation of country teacher. Then he married, and went first west, then south, on military service, and saw plenty of wild life, and made enemies as well as friends, for the best of us can not expect to please everybody, and Captain Eaton had too strong a character not to make some people, who did not think as he did, very angry.

When he was about thirty-five years old, trouble rose between the United States government and some of the countries of Africa, and the President sent Eaton out to Tunis as consul. Tunis is one of the Moorish kingdoms of Africa that border on the Mediterranean Sea, and were called "Barbary States." The other Barbary States were Morocco, Algiers, and Tripoli. For a long time these countries had been nests of pirates, who made their living by preying on the commerce of Christian nations, and making slaves of their seamen, so that the black flags of their ships were the terror of the Mediterranean. These robbers had the daring to demand tribute of European nations, which many of them paid annually for the sake of not being molested, and lately they had tried to extort money from the United States on the same plea. Eaton managed so cleverly and successfully with the Bey, or ruler, of Tunis, that he made a very satisfactory arrangement with him, and then returned home: but the other agents did not manage so well, and at last war was declared, for the United States had no idea of being[Pg 475] cowed and threatened by these pirates and murderers—far otherwise! The memory of her recent successful struggle with the greatest nation of the earth was too fresh to make it possible that an American ship should voluntarily lower its flag before a Moorish marauder. But what we would not do voluntarily we had to do by compulsion. The frigate Philadelphia, sailing in African waters, under Captain Bainbridge, was captured by the Bey of Tripoli, and towed into the harbor of that town. Her crew was carried off into slavery by the pirates, some languishing in hopeless imprisonment, others toiling their lives away under the burning sun of Africa.

Captain Decatur soon after sailed into the harbor in a vessel that he had captured from the Tripolitans, and retook and burned the Philadelphia; but, alas! hero as he was, he could not rescue his unfortunate countrymen. A few months later, in 1805, Eaton was sent back to the Barbary States as Naval Agent, and first stopped in Egypt. Here he made up his mind that he would bend all his energies toward rescuing the captives at Tripoli. He found that the rightful ruler of Tripoli, named Hamet Caramelli, had been driven away from his dominions by his brother Yusef, and was in Alexandria. Eaton offered to assist him to recover his throne, and collected a little army of five hundred men, most of them Mussulmans, a few Greek Christians, and nine Americans. With these followers he and Hamet marched across the desert toward Derne, in the kingdom of Tripoli. Eaton had not lost his boyish love of adventure yet, you see. This was just one of the bold, daring undertakings that he may have dreamed of in those early days when he stole away from his work to read with eager delight stories of wild venture and perilous escape in the peaceful shades of the forest around Woodstock. Doubtless these desert marches now entered upon far exceeded all his young imagination had pictured them.

It was a perilous journey, for the Arab sheiks and their followers, who made up most of his army, sometimes behaved in a very mutinous manner, and it took all Eaton's force of will and strict discipline to keep them in any sort of order, for Hamet showed very little decision of character, and proved that he was not very well fitted to be a ruler of men.

They were liable to be attacked by brigands from the mountains, too, so that ceaseless vigilance was needed. Some friendly Arab bands joined them on the road; so, when they reached Derne, Eaton found himself at the head of quite an army. Here he was met by two American ships, and with their help he bombarded the town, and took it by assault, driving the wild Arabs who were defending it back to the mountains. Now Eaton was in a situation to dictate his own terms to the usurper Yusef Bey, since he had brought Hamet Caramelli triumphantly into his own city of Derne, and had driven all enemies before him. He had laid his plans to march on Tripoli, drive off the usurper, and deliver his poor captive countrymen at the edge of the sword, when suddenly his successful career was brought to an end in rather a mortifying way. Yusef, frightened out of his defiance, consented to come to terms with Colonel Lear, American Consul-General at Algiers. If Colonel Lear had not been too hasty in concluding a treaty which forced the United States to pay sixty thousand dollars ransom money, when not a cent should have been given, and left the cruel Yusef safe on his throne, General Eaton might have marched on Tripoli with his victorious army, restored Hamet, and let the captives go in triumph.

Most people agreed that but for Eaton's promptness and bravery the troubles might have lasted much longer; and when he returned to America, soon after, he was received with great distinction by his countrymen, who made him quite an ovation. The Massachusetts Legislature voted him ten thousand acres of land in the district of Maine. The remainder of his life was passed in his pleasant home at Brimfield, Massachusetts, where he died June 1, 1811, at the age of forty-seven.

Aaron Burr tried to draw Eaton into his famous conspiracy, but Eaton was a firm patriot, and refused with horror to play the traitor. Wishing to make his true sentiments known, once for all, he gave this toast at a public banquet, in Burr's presence: "The United States—palsy to the brain that shall plot to dismember, and leprosy to the hand that will not draw to defend our Union!"

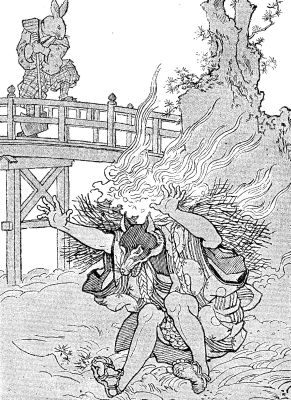

A good while ago there lived near the Clack-clack Mountains an old man and his wife, who, having no child, made a great deal of a pet hare. Every day the old man cut up food and set it out on a plate for his pet.

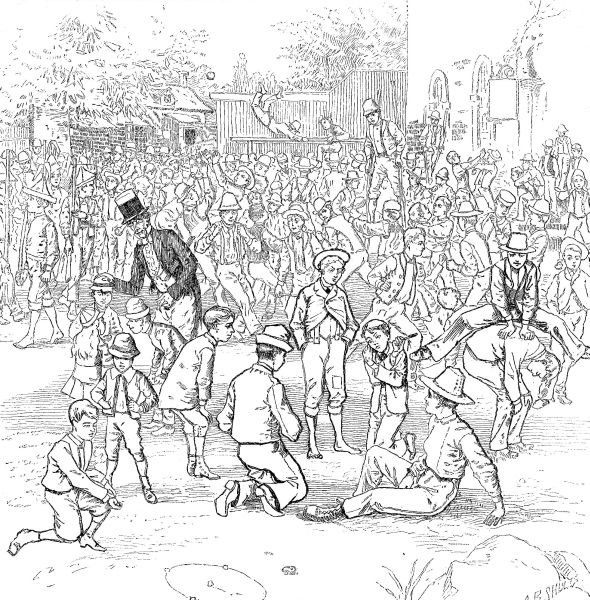

One day a badger came out of the forest, and in a trice drove away the hare, and eating up his dinner, licked the plate clean. Then, standing on his hind-legs, the badger blew out his belly until it was as round as a bladder and tight as a drum, and beating on it with his paws to show his victory, scampered off to the woods. But the old man, who was very angry, caught the badger, and tying him by the legs, hung him up head downward under the edges of the thatch in the shed where his old woman pounded millet. He then strapped a wooden frame to hold fagots on his back, and went out to the mountains to cut wood.

The badger, finding his legs pain him, began to cry, and begged the old woman to untie him, promising to help her pound the millet. The tired old dame, believing the sly beast, like a good-hearted soul laid down her pestle and loosened the cords round the beast's legs. The badger was so cramped at first that he could not stand; but when well able to move, he seized a knife to kill the old woman. The hare, seeing this, ran away to find the old man, if possible, and tell him. The badger, after stabbing the old woman, crushed her to death by upsetting the bureau upon her, and then threw her body into the mortar, and pounded her into a jelly. Setting the pot on to boil, he made the woman's flesh into a mess of soup, and ate all he could of it. Then the badger, by turning three double somersaults, turned himself into an old woman, looking exactly like the one he had just eaten. All being ready, he waited till the husband came home tired and hungry.

Soon the old man came back, thinking of nothing more than the hot supper he was soon to enjoy. Throwing down his fagots, he came into the house, and while he warmed his hands at the hearth, his wife (as he supposed) set the mess of soup and millet, with a slice of radish, before him on a tray. He fell to, and ate heartily, his wife (as he supposed) waiting dutifully near by till her lord was served. When the meal was finished he pulled out a sheet of soft mulberry paper from his bosom and wiped his old chops, smacking them well, as he thought what a good supper he had so much enjoyed. Just then the badger took on his real shape, and yelled out: "Old fool, you've eaten your own wife. Look in the drain, and you'll find her bones." And he puffed out his body, beat it like a drum, whisked his tail scornfully, and ran off.

Almost dead with grief and horror, the old man gathered up the bones of his wife, and decently buried them. Then he made a vow to take revenge on the badger. Just then the hare came back from the mountains, and after condoling with the old man, said he would also take revenge on the badger.[Pg 476]

So the hare buckled on his belt, in which he kept his flint and steel, and made ready a plaster of red peppers.

Going into the forest, he saw Mr. Badger walking home with a load of fagots and brush on his back. Creeping up softly behind him, the hare set the bundle on fire. The badger kept on, until he heard the crackling of the burning twigs. Then he jumped wildly, and cried out, "Oh, I wonder what that noise is!"

"Oh, this is the Clack-clack Mountain; it always is crackling here," said the hare, looking down from the top of the hill.

The fire grew more lively, and the badger became scared. He fell down, and threw out his fore-paws wildly.

"Katchi-katchi" (clack-clack), went the dry fagots, as the red-hot coals flew about.

"What can it be?" said Mr. Badger.

"This mountain is called Katchi-katchi (Clack-clack); don't you know that?" said the hare, coolly standing on the bridge, and leaning on his axe.

"Oh! oh! oh! help me!" howled the badger, as the blazing twigs began to burn the hair off his back. And running through the woods to a stream near by, he plunged in, and the fire was put out. But his running had only increased the fire and burning, and his back was all raw. When the hare found the badger at home in his house, he was howling in misery, and expecting to die from his burn.

"Let me take a look at your burn, Mr. Badger," said the hare; "I have some famous salve to cure it"—as he pretended to be very pitiful, and held up a bowl of what seemed to be fine salve in one paw, while in the other was a soft brush of fine hair. Then the hare clapped on the red-pepper plaster, and ran away, while the badger rolled in pain.

By-and-by, when the badger got well, he went to see the hare, to have it out with him. He found the hare building a boat. "Where are you going in that boat?" said the badger.

"I'm going to the moon," said the hare. "Come along with me. There's another boat."

So the badger, thinking to catch some fish by going on the water, got into the boat, and both launched away.

Now the boat in which Mr. Badger rowed was made of clay, which soon began to melt away in the water. Seeing this, the hare lifted his paddle, and with one blow sunk the boat, and the badger was drowned.

The hare went back and told the old man, who was glad that his wife had been revenged, and more than ever petted the hare to the end of his life.[Pg 477]

Some time in the middle of the night Joe Sharpe woke up from a dream that he had fallen into the river, and could not get out. He thought that he had caught hold of the supports of a bridge, and had drawn himself partly out of the water, but that he had not strength enough to drag his legs out, and that, on the contrary, he was slowly sinking back. When he awoke he found that he was very cold, and that his blanket felt particularly heavy. He put his hand down to move the blanket, when, to his great surprise, he found that he was lying with his legs in a pool of water.

Joe instantly shouted to the other boys, and told them to wake up, for it was raining, and the tent was leaking. As each boy woke up he found himself as wet as Joe, and at first all supposed that it was raining heavily. They soon found, however, that no rain-drops were pattering on the outside of the tent, and that the stars were shining through the open nap.

"There's water in this tent," said Tom, with the air of having made a grand discovery.

"If any of you fellows have been throwing water on me, it was a mean trick," said Jim.

All at once an idea struck Harry. "Boys," he exclaimed, "it's the tide! We've got to get out of this place mighty quick, or the tide will wash the tent away."

The boys sprung up, and rushed out of the tent. They had gone to bed at low tide, and as the tide rose it had gradually invaded the tent. The boat was still safe, but the water had surrounded it, and in a very short time would be deep enough to float it. The tide was still rising, and it was evident that no time should be lost if the tent was to be saved.

Two of the boys hurriedly seized the blankets and other articles which were in the tent, and carried them on to the higher ground, while the other two pulled up the pins, and dragged the tent out of reach of the water. Then they pulled the boat farther up the beach, and having thus made everything safe, had leisure to discover that they were miserably cold, and that their clothes, from the waist down, were wet through.

Luckily, their spare clothing, which they had used for pillows, was untouched by the water, so that they were able to put on dry shirts and trousers. Their blankets, however, had been thoroughly soaked, and it was too cold to think of sleeping without them. There was nothing to be done but to build a fire, and sit around it until daylight. It was by no means easy to collect fire-wood in the dark; and as soon as a boy succeeded in getting an armful of driftwood, he usually stumbled and fell down with it. There was not very much fun in this; but when the fire finally blazed up, and its pleasant warmth conquered the cold night air, the boys began to regain their spirits.

"I wonder what time it is?" said one.

Tom had a watch, but he had forgotten to wind it up for two or three nights, and it had stopped at eight o'clock. The boys were quite sure, however, that they could not have been asleep more than half an hour.

"It's about one o'clock," said Harry, presently.

"I don't believe it's more than nine," said Joe.

"We must have gone into the tent about an hour after sunset," continued Harry, "and the sun sets between six and seven. It was low tide then, and it's pretty near high tide now; and since the tide runs up for about six hours, it must be somewhere between twelve and one."

"You're right," exclaimed Jim. "Look at the stars. That bright star over there in the west was just rising when we went to bed."[Pg 478]

"You ought to say 'turned in,'" said Joe. "Sailors never go to bed; they always 'turn in.'"

"Well, we can't turn in any more to-night," replied Tom. "What do you say, boys? suppose we have breakfast—it'll pass away the time, and we can have another breakfast by-and-by."

Now that the boys thought of it, they began to feel hungry, for they had had a very light supper. Everybody felt that hot coffee would be very nice; so they all went to work, made coffee, fried a piece of ham, and, with a few slices of bread, made a capital breakfast. They wrung out the wet blankets and clothes, and hung them up by the fire to dry. Then they had to collect more fire-wood; and gradually the faint light of the dawn became visible before they really had time to find the task of waiting for daylight tiresome.

They decided that it would not do to start with wet blankets, since they could not dry them in the boat. They therefore continued to keep up a brisk fire, and to watch the blankets closely, in order to see that they did not get scorched. After a time the sun came out bright and hot, and took the drying business in charge. The boys went into the river, and had a nice long swim, and then spent some time in carefully packing everything into the boat. By the time the blankets were dry, and they were ready to start, the tide had fallen so low that the boat was high and dry; and in spite of all their efforts they could not launch her while she was loaded.

"We'll have to take all the things out of her," said Harry.

"It reminds me," remarked Joe, "of Robinson Crusoe that time he built his big canoe, and then couldn't launch it."

"Robinson wasn't very sharp," said Jim. "Why didn't he make a set of rollers, and put them on the boat?"

"Much good rollers would have been," replied Joe. "Wasn't there a hill between the boat and the water? He couldn't roll a heavy boat up hill, could he?"

"He could have made a couple of pulleys, and rigged a rope through them, and then made a windlass, and put the rope round it," argued Jim.

"Yes, and he could have built a steam-engine and a railroad, and dragged the boat down to the shore that way, just about as easy."

"He couldn't dig a canal, for he thought about that, and found it would take too much work," said Jim.

"But we can," cried Harry. "If we just scoop out a little sand, we can launch the boat with everything in her."

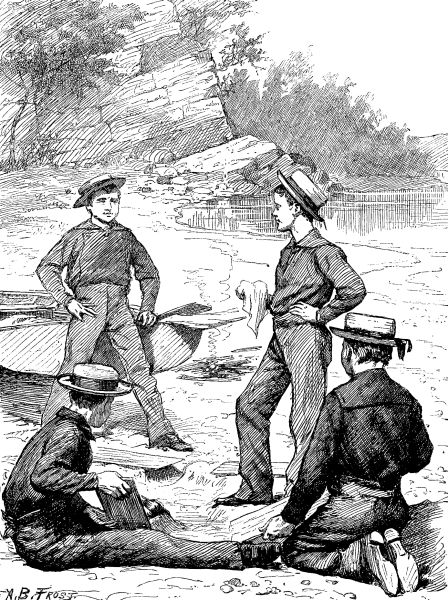

TOM MAKES A CALCULATION.

TOM MAKES A CALCULATION.

The boys liked the idea of a canal; and they each found a large shingle on the beach, and began to dig. They dug for nearly an hour, but the boat was no nearer being launched than when they began. Tom stopped digging, and made a calculation. "It will take about two days of hard work to dig a canal deep enough to float that boat. If you want to dig, dig; I don't intend to do any more digging."

When the other boys considered the matter, they saw that Tom was right, and they gave up the idea of making a canal. It was now about ten o'clock, and they were rather tired and very hungry. A second breakfast was agreed to be necessary, and once more the fire was built up and a meal prepared. Then the boat was unloaded and launched, and the boys, taking off their shoes and rolling up their trousers, waded in the water and reloaded her. It was noon by the sun before they finally had everything in order, and resumed their cruise.

There was no wind, and it was necessary to take to the oars. The disadvantage of starting at so late an hour soon became painfully evident. The sun was so nearly overhead that the heat was almost unbearable, and there was not a particle of shade. The boys had not had a full night's sleep, and had tired themselves before starting by trying to dig a canal. Of course the labor of rowing in such circumstances was very severe; and it was not long before first one and then another proposed to go ashore and rest in the shade.

"Hadn't we better keep on till we get into the Highlands? We can do it in a quarter of an hour," said Tom.

As Tom was pulling the stroke oar, and doing rather more work than any one else, the others agreed to row on as long as he would row. They soon reached the entrance to the Highlands, and landed at the foot of the great hill called St. Anthony's Nose. They were very glad to make the boat fast to a tree that grew close to the water, and to clamber a little way up the hill into the shade.

"What will we do to pass away the time till it gets cooler?" said Harry, after they had rested awhile.

"I can tell you what I'm going to do," said Tom; "I'm going to get some of the sleep that I didn't get last night, and you'd better follow my example."

All the boys at once found that they were sleepy; and having brought the tent up from the boat, they spread it on the ground for a bed, and presently were sleeping soundly. The mosquitoes came and feasted on them, and the innumerable insects of the summer woods crawled over them, and explored their necks, shirt sleeves, and trousers legs, as is the pleasant custom of insects of an inquiring turn of mind.

"What's that?" cried Harry, suddenly sitting up, as the sound of a heavy explosion died away in long, rolling echoes.

"I heard it," said Joe; "it's a cannon. The cadets up at West Point are firing at a mark with a tremendous big cannon."

"Let's go up and see them," exclaimed Jim. "It's a great deal cooler than it was."

With the natural eagerness of boys to be in the neighborhood of a cannon, they made haste to gather up the tent and carry it to the boat. As they came out from under the thick trees, they saw that the sky in the north was as black as midnight, and that a thunder-storm was close at hand.

"Your cannon, Joe, was a clap of thunder," said Harry. "We're going to get wet again."

"We needn't get wet," said Tom. "If we hurry up, we can get the tent pitched and put the things in it, so as to keep them dry."

They worked rapidly, for the rain was approaching fast, but it was not easy to pitch the tent on a side-hill. It was done, however, after a fashion, and the blankets and other things that were liable to be injured by the wet were safely under shelter before the storm reached them.

On the Long Island shore, where the Navy-yard now extends its shops and vessels around Wallabout Bay, there was in the time of the Revolution a large and fertile farm. A number of flour mills, moved by water, then stood there. The flat fields glowed with rich crops of grain, roots, and clover. Their Dutch owners still kept up the customs and language of Holland; at Christmas the kettles hissed and bubbled over the huge fires, laden with olycooks, doughnuts, crullers; at Paas, or Easter, the colored eggs were cracked by whites and blacks, and all was merriment. The war no doubt brought its difficulties to the Dutch farmers; they were sometimes plundered by both parties, and they had little love for King George. They lived on in decorous silence, waiting for the coming of peace, remembering how their ancestors in Holland had once fought successfully for freedom against the Spaniards and the French. But in front of the quiet farm at Wallabout, and anchored in the bay, were seen several vessels,[Pg 479] decayed, unseaworthy, and repulsive. They were the prison-ships of New York. Here from the year 1776 a large number of American prisoners were confined until the close of the war, and the tragic tales of their sufferings and fate lend a melancholy interest to the Wallabout shore.

The largest of the prison-ships—the old Jersey—was crowded with miserable captives. She was an old man-of-war, worthless, decayed; her low decks and dismal hold were converted into a jail; her crowded inmates were only thinned by the hand of death. The old Jersey may well be taken as one of the best symbols of the terrors of war. Her miserable captives pined away for months and years, deprived of all that makes life tolerable. In the chill and bitter frosts of winter no fires warmed her half-clad inmates; in the hot summer they faded away beneath the pitiless heat. Disease preyed upon them, yet no physician, it is said, was suffered to visit them. They were clothed in rags and tatters; their food was so scanty and often so repulsive that they lived in continual starvation. The fair youth of Connecticut and Rhode Island, the young sailors of New York and New Jersey, confined in these floating dungeons, were the sacrifices to the ambition of King George. They died by hundreds and even thousands during the war; the whole shore was lined with the unmarked graves of the patriot dead; the prison-ships were the scandal of the time, and their starved inmates seldom bore long the pains of the merciless imprisonment. It is said that the bones of eleven thousand dead were found upon the shore, and reverently buried in a common tomb.

Yet the prisoners of the old Jersey and the other ships were not left always without sympathy and aid. Often a boat was seen sailing from the rich farms on the Wallabout, laden with provisions for the famished patriots. The Dutch farmers from their own diminished resources gave bountifully to the sufferers. The ladies of the household worked warm stockings with the busy knitting-needle; the spinning-wheel was never idle; the fair Dutch damsels, demure and prudent, blushing with the rich complexions of Amsterdam, were never weary of their charitable toil; and many a poor prisoner was saved and strengthened by the gifts of his unknown friends. As the war advanced, too, the successes of the Americans seem to have convinced the royal chiefs that they were at least deserving of tolerable treatment. Some of the worst abuses of the system were removed. Hospital-ships were provided; the sick were separated from the healthy; the Whitby, the most infamous of the floating jails, was abandoned. Yet still, an observer relates, the dead were carried away every morning from the old Jersey, and still the horrors of captivity in the prison-ships exceeded all that had been known in every recent European war.

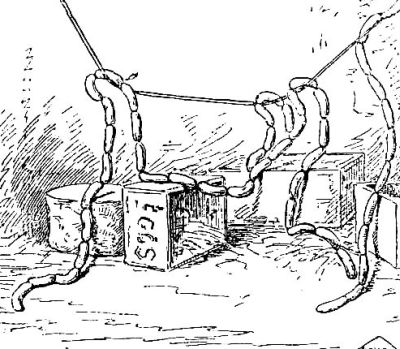

Several curious escapes are related. Once, in 1777, as a boat hung fastened to the old Jersey unnoticed, three or four prisoners let themselves down into it quietly, cast off the rope, and drifted away slowly with the tide. It was evening, and the darkness saved them. Their escape was discovered, and guns were fired at random after them; but they floated unharmed along the East River, passed what are now the Fulton and South ferries, and reached by a miracle the New Jersey shore. Here they found friends, and were safe. At another time, in the cold winter of 1780, fifteen half-clad, half-famished prisoners escaped in the night on the ice; others who followed them turned back, overpowered by the cold. One was frozen to death. It is almost possible to see in fancy the miserable band of shivering fugitives fleeing over the ice of the restless river in the deep cold of the winter's night, chased by the fierce winds, half lost in the blinding snow. They made their way to the Connecticut shore. A very remarkable escape from the Old Sugar-House is related of a Boston prisoner. He dug a passage under Liberty Street from the prison to the cellar of the house on the opposite side of the way. The difficulty of making the excavation will be plain to every one who looks at the labors of a party of workmen opening a trench for gas-pipes or water. Yet the Boston boy burrowed under-ground until he found himself free.

The prison-ships were retained in use until 1783. Several were burned at different times, either by accident or by the prisoners in their despair. At the close of the war the remaining ships were all sunk or burned. A few years ago the wreck of the old Jersey could still be seen on the Wallabout shore.

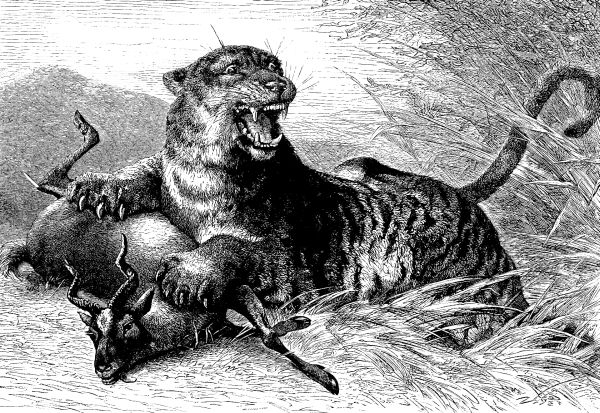

The royal tiger of Asia is an animal celebrated for its beauty and its agility, cunning, and prodigious strength. Its skin is a bright tawny yellow, with glossy black stripes running downward from its back. Its tail, which is long and supple, is ringed with black, and its large head is marked in a very handsome manner. It is like a great cat. Its puffy cheeks are ornamented with white whiskers, and its big paws are like those of a pussy magnified fifty times. Its motions are very graceful, and whether lying down, its nose on its paw, sleeping, or walking through the paths of its native jungle with soft cat-like tread, it appears formed of muscle and sinew, without a bone in its body, so gracefully does it curve and twist itself as it moves.

The tiger is not considered a courageous beast by hunters, who say that if it is faced boldly, it will turn and slink away among the bushes, if it can. But if it can attack a hunter from behind, it will spring upon him, filling the air with its savage growls, and probably kill him with the first blow of its mighty paw.

The strength of this creature is almost incredible. It will break the skull of an ox, or even that of a buffalo, with the greatest ease. A story is told of a buffalo belonging to a peasant in India, which, while passing through a swamp, became helplessly entangled in the mire and underbrush. The peasant left the buffalo, and went to beg his neighbors to assist him in extricating the poor beast. When the rescuing party returned, they found a tiger had arrived before them, and having killed the buffalo, had just shouldered it, and started to march home to its lair with the prey. The tiger was soon dispatched by the peasant and his friends, and his beautiful skin was made to atone in a measure for the murder of the buffalo, which, when weighed, tipped the scales at more than a thousand pounds—a tremendous load for so small an animal as a tiger to shoulder and carry off with ease.

The tiger is very troublesome to the inhabitants of certain localities in India, as it attacks the herds, and makes off with many a fat bullock; and when unable to find other provender it will even attack the huts of the natives, sometimes tearing away the thatch, and springing in with a loud roar on a startled family. Instances are rare, however, of tigers attacking human beings, except when surprised and driven to self-defense. In some portions of the country they are very abundant, and may be heard every night roaring through the jungles in search of deer and other beasts upon which they prey. Even the savage wild boar of India does not terrify this queen of cats, and often bloody battles occur between these two powerful beasts.

As a mother the tiger is very devoted, and will fight for its pretty kittens to the last extremity. A story is told of an English officer who, while hunting in India, came upon the lair of a tiger, in which a tiny kitten, about a fortnight old, was lying all alone. Thinking that the mother was probably among the beasts killed by his party, the officer took the kitten to the camp, where it was chained to a pole, and amused the whole company with its graceful gambols. A few hours later, however, the whole camp was shaken by terrible roars and shrieks of rage,[Pg 480] which came ever nearer and nearer. The kitten heard them, and became a miniature tiger at once, showing its teeth, and answering with a loud wail. Suddenly there leaped into the camp inclosure a furious tigress with glaring eyes. Without deigning to notice the robbers of her baby, she seized the little thing in her teeth, snapped the small chain which held it with one jerk, and briskly trotted off with it into the jungle. Not a man in the camp dared move, and no one was malicious enough to fire at the retreating mother that had risked her life to regain possession of her baby.

A ROYAL BENGAL TIGER.

A ROYAL BENGAL TIGER.

Any one who has watched the feeding of caged tigers in a menagerie can easily imagine how terrible a hungry tiger would be, were he running free in his native jungle. As supper-time approaches, the tigers begin to roar and growl, and march restlessly up and down the cage. When the keeper approaches with the great pieces of raw beef, their roaring makes everything tremble. With ferocity glaring in their eyes, the tigers spring for the food, and begin to devour it eagerly. They often lie down to eat, holding the meat in their fore-paws like a cat, rolling it over and over while they tear it in pieces, growling savagely all the while.

The royal tiger is found only in Asia; for the beast called a tiger in South America and on the Isthmus of Panama is properly the jaguar, and its skin is not ornamented by stripes, but by black spots. It is not so powerful as its royal relative, but very much like it in its habits. Like the tiger, it is an expert swimmer, and as it is very fond of fish, it haunts the heavily wooded banks of the great South American rivers, and is a constant terror to the wood-cutters, who anchor their little vessels along the shore.

The crocodiles and the jaguars are at constant war with each other. If a jaguar catches a crocodile asleep on a sand-bank, it has the advantage, and usually kills its antagonist; but if the crocodile can catch its enemy in the water, the jaguar rarely escapes death by drowning.

Jaguars are not as plentiful on the Isthmus of Panama as formerly, before the scream and rumble of the locomotive disturbed the solitudes of the dense tropical forest. Still, large specimens are occasionally killed there, and their beautiful skins bring a high price when brought to market.

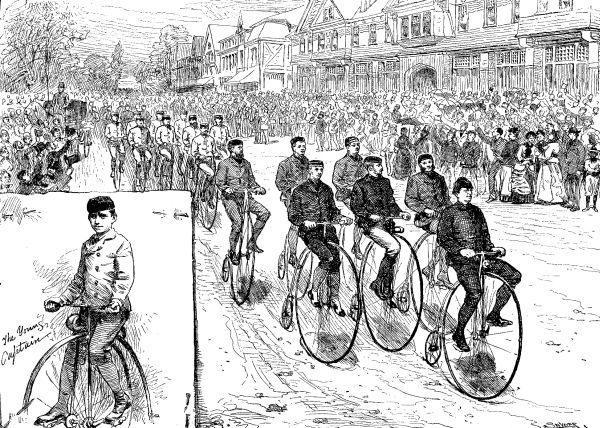

One of the prettiest and most interesting sights ever seen in the gay city of Newport was the parade of bicyclers last Decoration-day, where, among the one hundred and fifty riders, were to be seen the uniforms of twenty-five crack clubs.

The illustration of the procession on next page shows it on Bellevue Avenue while passing the quaint and beautiful Casino Building. First of all rides the commander, Captain Hodges, of the Boston Bicycle Club, and directly behind him, riding three abreast, are the six marshals of the procession, who act as his aides. Then come the men of the New York Club, in gray and scarlet, riding in column of fours, and followed by the long line of glittering steel and gay uniforms that stretches for nearly a mile along the pleasant street.

Crowds of people have gathered to watch the procession, and their cheers, as some particularly well-drilled club passes, cause the men to ride with great care, and to preserve their lines so well that they move with the steadiness and precision of a body of cavalry.

Of all the riders in this long procession, the youngest was probably the best. Theodore R——, or "the young captain," as he is called, is but fourteen years old, and looks much younger. He lives in Philadelphia, and has practiced riding the bicycle in a rink in that city until his performances upon it are as wonderful as those of a circus rider on his horse.

In the picture of "the young captain" he is represented as mounted on his own machine, of which the driving-wheel is but forty-two inches in diameter. His most wonderful riding is, however, done upon a bicycle twelve or fourteen inches higher than this, and of which he can[Pg 481] but barely touch the pedals as they come up. Thus he keeps the machine in motion by a succession of little kicks or pushes. He rides bicycles so tall that to gain the saddle he has actually to climb up the backbone of the machine after he has set it in motion with a vigorous push.

"The young captain" is a very bright boy, and excels in all games and feats of skill, while at the same time he is a good scholar, and stands well in all his classes.

Since the great Newport meet of bicyclers, or "wheelmen," as they are now generally called in this country, a number of letters containing questions about bicycles have been written by boys anxious to become riders, and sent to Young People. In the following hints to young riders I will try and answer all these questions:

Any active boy of ten years of age and upward may become a wheelman.

It is best to learn to ride on an old-fashioned wooden machine, or "bone-shaker," or on a bicycle so low that the rider may touch the ground with his toes. By this means he will learn to maintain his balance without getting any serious falls.

Anybody who can ride a "bone-shaker" can ride a bicycle, though in the latter case he must learn to mount his machine before he can ride it.

To learn the "mount" take your machine by the handles, give it a running push, place your left foot on the step, and, rising from the ground, maintain your balance as long as possible in that position without attempting to gain the saddle. After trying this a dozen times or more, try to take your seat in the saddle, not with a spring, but slide in easily, and do not let your body lean forward or you may pitch over the handles.

A beginner should have his saddle set well back on the spring. Although this position gives less power, it is much safer.

In going up hill lean well forward, and transfer the entire weight from the saddle to the pedals. Do not be ashamed to dismount in going up hill, but do so in every case rather than exhaust yourself.

In going down hill lean back as far as possible, and keep your machine under control. A little practice in back-pedalling, or pushing against the pedal as it comes up rather than as it goes down, will enable you to take your machine down very steep hills at ordinary walking pace. If your machine does escape from your control, throw your legs over the handles, and "coast," as you are less liable to get a bad fall while in this position than in any other.

Keep to the right of the road as much as possible. Always keep to the right when you meet a team, foot-passenger, or other bicycle, and in overtaking any of these always pass to the left. Dismount and walk past any horse that becomes frightened at your bicycle.

Always carry a light when riding at night.

Be careful not to use your whistle or bell more than is absolutely necessary, otherwise you will become a nuisance, and as such will not be a welcome addition to the ranks of wheelmen.

Remember that while you have rights for which you are bound to stand up, others have equal rights, which you are equally bound to respect.

In selecting a bicycle, be sure that it fits you perfectly. Do not gratify a mistaken ambition by trying to ride a wheel that is too large for you. The larger the wheel, the more difficulty you will find in driving it up hill.

As soon as you own a bicycle, make yourself familiar with every part of it, and especially with all its adjustments.

Never lend your bicycle.

Always clean and adjust it yourself. If it gets broken, send it to none but a first-class machinist for repairs.

FIRST GRAND MEET OF AMERICAN WHEELMEN.—Drawn by W. P.

Snyder.

FIRST GRAND MEET OF AMERICAN WHEELMEN.—Drawn by W. P.

Snyder.

It was the pig did it.

The bigger that pig grew, the more he squealed, and the less he seemed to like his pen.

Ben knew it, but for all that he wondered how it came to pass that he should find that pig in the village street, half way down to the tavern.

"Out of the pen into the barn-yard, and out of that into the street when the gate was open. Won't I have a time getting him home!"

There was little doubt of that, for the pig felt that it was his duty to root as he went, and he refused to walk quietly past any good opportunity to thrust his snub-nose into something.

Ben worked, and so did the pig.

"Hullo! What's that?"

The pig had turned up a clod of earth with something sticking on it, and Ben sprang forward to pick it up.

"It's a cent!"

It was round; it was made of copper; it was a coin of some kind; but it was black and grimy, and Ben rubbed hard to clean it.

"I never saw a cent like that before. I can't even read what it says on it."

"What have you found, Ben, my boy?"

"Guess it's a kind of a cent. The pig found it."

All the boys in the village knew old Squire Burchard, only they were half afraid of him. It was said he could read almost any kind of book, and that was a wonderful sort of man for any man to be.

"The pig found it? I declare! I guess I'll have to buy it of you."

"Don't you s'pose it'll pass?"

"Well, yes, it might; but it'll only buy a cent's worth. I'll give you more than that for it."

"Going to melt it over and make a new cent of it?"

"No, Ben, not so bad as that. I'll keep it to look at. It's a very old German coin, and I'm what they call a numismatist."

Ben listened hard over that word for a moment, and tried to repeat it.

"Rumismatics—I know; it's a good deal like what father says he has sometimes. Gets into his back and legs."

"Not quite, Ben; but it makes me gather up old coins, and put them in a glass case, and look at them."

"Father's is worse 'n that; it takes him bad in rainy weather."

"Well, Ben, I'll give the pig or you, just as you say, a quarter of a dollar for that cent."

Ben's eyes fairly danced, but all he could manage to say was, "Yes, sir. Thank you, sir. Guess I will."

"There it is, Ben. It's a new one. I don't care much for new ones. What'll you do with it?"

Ben hesitated only a moment, for he was turning the quarter over and over, and thinking of just the answer to the squire's question.

"It's a puppy, sir. Mrs. Malone said I might have it for a quarter, and father said I couldn't buy it unless I found the money."

"It'll be the pig's puppy, then? All right; but you can't make pork of him."

The pig was driven home in a good deal of a hurry, without another chance given him to root for old coins; and when Ben's father came in from the corn field that night, there was Ben ready to meet him with the puppy.

"Got him, have you?"

Ben had to explain twice over about the old cent and the Squire.

"Oh, the pig did it. Well, Ben, I don't see what we want of another dog; though that is a real pretty one. Too many dogs in this village, anyhow."

The next day Ben's father went to town with a load of wheat, and Ben went with him.

He had not owned that puppy long enough to feel like leaving him at home, so the little lump of funny black curls and clumsiness had to go to town with him.

Ben's father was in the store, selling his wheat, and Ben was sitting on top of the load in the wagon, when a carriage with a lady in it was pulled up in the street beside it.

"Is that your puppy, my boy?"

"Yes, ma'am."

"Will you sell it? I want one for my little boy."

"It's a real nice puppy—"

"What will you sell him for?"

Ben did not feel at all like parting with his new pet, but he knew very well what his father thought about it. Still, it might save him the puppy if he asked a tremendous price for it.

"I'll take five dollars, ma'am."

"Bring him to me, then. It's just such a dog as I thought of buying."

It seemed to Ben a good deal as if he were dreaming; but he did as he was told, and climbed back to his perch on the heaped-up bags of wheat to wait for his father.

It was not long before he had sold the wheat and came out.

"Why, Ben, where's your puppy?"

"There he is, father."

"Why, if that ain't a five-dollar bill! You don't say so!"

Ben explained, and added, "The pig did it, father."

"Well, yes, the pig did it. It just beats me, though."

"He won't know what to do with a five-dollar bill."

"Nor you either. But soon's I can throw off this load we must drive on up town. There's to be a horse auction."

Ben knew what that meant, for his father knew all about horses, and was all the while buying and selling them. So it was not long before the wagon was empty, and Ben and his father made their way to where the horses were to be sold.

"There's a good many of 'em," said Ben's father, "but the whole lot isn't worth much. I guess there isn't anything here I want."

Not many people were bidding for the horses, and they were indeed a poor-looking lot; but pretty soon a gray horse was led out that limped badly, and was as thin as if he had been fed on wind. One man bid a dollar for him, and another bid two, and there was a good deal of fun made about it; but Ben's father had very quietly slipped down from the wagon, and taken a careful look at the lame horse.

For all that, Ben was a little surprised when the auctioneer's hammer fell, and he shouted, "Sold! for five dollars, to—What's your name, mister?"

"Ben Whittlesey."

Ben's father said that. But it wasn't his name. His name was Robert.

"Ben," said his father, when he came back to the wagon, "hand me that five-dollar bill. If I can get that horse home, I'll cure him in a fortnight. There's no great thing the matter with him."

There was trouble enough in making the poor lame animal limp so many miles, and they got home after dark; but that was just as well, for nobody saw the new horse, or had a chance to laugh at him or his owner.

"It's the pig's horse," said Ben.

Ben's father was as good as his word about curing the lameness, and plenty of oats and hay, and no work, and good care, did the rest. The man who sold the gray for five dollars would not have known him at the end of two weeks.

It was just about two weeks after that that Ben's father[Pg 483] drove the pig's horse to town and back in a buggy, and with a nice new harness on. He stopped at the blacksmith's shop on his way home, and Mr. Corrigan, the blacksmith, seemed to take a great fancy to the gray.

"Just the nag I want, Mr. Whittlesey; only I've no ready cash to pay for him."

"I don't sell on credit, you know," said Mr. Whittlesey. "Anything to trade?"

"Nothing that I know of. Unless you care to take that vacant lot of mine, next the tavern. Tisn't doing me any good. I had to take it for a debt, and I've paid taxes for it these three years."

"Will you swap even?"

"Yes, I might as well."

There was more talk, of course, before the trade was finished, but it came out all right in the end. Before the next day at noon Mr. Corrigan owned the pig's horse; but the deed of the town lot was made out in the name of Ben Whittlesey, and not of the pig.

"Father," said Ben, at the tea table, "mayn't I let that pig out into the road every day?"

"No, Ben; all the pigs in the village can't root up another cent like that."

"He did it."

"Well, Ben, he did and he didn't. Do you know how he got the town lot for you?"

"Why, yes. Don't I?"

"Not quite. You saw him turn up the cent, and knew what to do with it; he didn't."

"Yes, father."

"And Squire Burchard saw the cent, and knew what to do with it; you didn't."

"Yes, father."

"And the lady saw your puppy, and knew what to do with it, and you didn't, nor I either. And I saw the gray horse, and knew what to do with him; the rest didn't."

"But I don't know what to do with the pig's town lot."

"No, nor Mr. Corrigan didn't, nor I either; but the man from town that's just bought the old tavern is going to build it over new, and wants to buy that lot to build on. I tell you what, Ben, my boy, there isn't much in this world that's worth having unless somebody comes along that knows what to do with it."

"Ben!" suddenly exclaimed his mother, as she looked out of the window, "there's that pig out in the garden!"

"Jump, Ben," said his father. "If he gets into your patch of musk-melons, he'll know just exactly what to do with them."

Before Ben got the pig out of the garden, the pig learned that Ben knew exactly what to do with a big stick.

"Mamma, will you please listen a moment?"

"How can I, Quillie dear? just see how busy I am," answered mamma, turning over a letter she was writing, while a man was bringing in trunks from the store-room, and another man was waiting for orders, and through a vista of open doorways was seen a dress-maker at work upon gingham slips and linen blouses.

"If you please, ma'am, a bit of edging will look none the worse on these cambrics, and the flannels need a touch of scarlet; even the wild flowers have vanity enough for a little color of their own."

"True enough, Ellen. Well, get your samples ready. Now, Quillie, I am going to address this letter, and then I promise to listen to you."

Quillie sighed—she found it so difficult to wait when she had so much to say. But she only fidgeted a little as mamma scrawled off an address in letters which Quillie thought would cover half her copy-book, then the little taper was lighted, the wax was melted, the pretty crest was imprinted on the seal, and mamma turned with a relieved smile to the little girl.

"Well, Quillie, what is it?"

"It's only this, mamma," began Quillie, impetuously: "I want to take a friend to the country with us."

"Who is the friend? why can not she go with her own people?" said mamma.

"Now, mammy dear, please don't hurry me; you know madame, our French teacher at school, has a little girl about my age—eight and a half. Well, if it wasn't for her, madame says she could go with some pupils to their country-seat, and teach them all summer, but they will not have her child, which is very hateful and disobliging, I think; and it popped into my head that perhaps you would let us have Julie with us, for the madame says she can not leave her alone in the city, and she has no relatives—hardly any friends—and I think it would make madame so happy not to lose this chance of giving lessons, and yet to have Julie, and—and—"

Mamma stooped down and kissed her little girl. "There," she said, in her quick, decisive way, "that will do. It was a kind thought, and I will consider it. Now run off and dig in the garden; your seeds are coming up nicely."

"But, mamma," said Quillie, not quite satisfied, "are you sure you won't forget?"

"I promise not to," was the answer, and she arose to change the coquettish cap and morning-gown for her street costume. Then she took out her pencil, and jotted down two or three errands in her memorandum-book, and gathering up the samples to match for Ellen's work, out she went.

It was a warm day, a balmy air, but one which induces languor, and as Mrs. Coit stopped at a street corner and bought a bunch of roses, she thought she would get the children out of town as soon as possible. Her eye was next attracted by some exquisite laces. She wanted a few yards, and stopped to price them. They were thread, filmy as cobwebs; they were costly; and as she held them in her hand, debating the purchase, she thought of Quillie's request: the cost of the lace would more than meet the expense of sending little Julie away. She concluded not to buy the laces. And so she went on with her errands.

At last she had finished, and turned off into a side street, got into a car, and was whisked away to a quiet place in the old part of the city. She stopped before a house which had in its day been fine; now it looked like a person who is keeping up appearances—a little shabby and worn, and wanting freshness. She rang the bell, and asked if Madame Garnier lived there. She was directed by a slovenly maid to a room on an upper floor, and left there. The air was redolent of garlic. She knocked at the door, and a little pattering of feet was heard, the door was opened on a crack, and a small head was to be seen, covered with a tiny handkerchief tied under the chin; a large checked apron concealed the rest of the small person. When the small person saw that the visitor was a lady, she no longer kept the door more than half closed, but throwing it wide open, she made a profound courtesy, and said, "Pardon, madame; please to enter."

Mrs. Coit paused, smilingly taking in the background of this interior. A sunny window full of plants, a bed with ruffled pillow-cases, a gilt clock, a canary, a table set out for two, a writing-desk and books in a corner, and a cooking stove, with a bubbling saucepan sending the cover dancing up and down. It was very close and warm, and the little hostess was pale, despite the heat.

Mrs. Coit had no time to spare. She asked the child if she were Julie Garnier, and if she wanted to spend two or three months in the country.[Pg 484]

The child opened her eyes in silent wonder. "Could madame be in earnest? Was it possible?"

Mrs. Coit explained, and in addition took out her pencil, and with rapidity wrote a note to madame.

The little Julie fairly wept with delight. To be in the country, with birds and bees and brooks—ah! it was too much felicity. Her mother would be wild with pleasure.

Then Mrs. Coit was going; but Julie could not let her depart without a taste of her pot au feu, which she was cooking for her dear pauvre petite maman—just one sip, if madame could take no more; and pushing a chair to the table, and hurriedly wiping off an old cracked faience bowl, pretty enough in its day, the little eager hands dipped out a ladleful of soup. Mrs. Coit found it delicious. Warm as was the room and the repast, it was yet refreshing; so thanking the child for her hospitality, she at last took her departure.

A week from this time behold an eager group of little ones on the deck of a Hudson River night boat kissing their hands to Mr. and Mrs. Coit on the wharf. Nurse is on guard, and counts the heads to see if all are with her. Quillie's yellow locks are beside Julie's dark tresses; Fred and Willie come next; and little Artie, who scorns being the baby, waves in great dignity, as color-bearer, a small American flag. Long before the stars are out they beg to go to their state-rooms. They creep into the little beds, and imagine themselves on the tossing ocean. Nurse hears them discussing who shall be in the upper and who in the lower berths, and whether they shall be able to remain in them at all, for the vessel may pitch them all out; then Julie silences all with a vivid account of her travels. She gesticulates as she talks, occasionally rolls those dark eyes of hers, speaks of the great steam-ships, the mighty waves, the roar of the wind, the scream of the fog-whistle, and the terrible mal de mer. Instinctively they yield to her vast experience, and offer no more remarks, but silently prepare for their slumbers.

Quite with the early dawn they awake again, refreshed, eager, and taking in long draughts of the pure air into which they have come. Where are the docks and wharves and shipping? where the scenes of the night before? In the rosy flush of the morning lie the green hills and meadows. The birds are straining their throats with melody, the cocks are crowing, the geese cackling, and they hear the lowing of cows and the bleating of sheep.

"Is it paradise?" asks Julie.

"No, it is only Catskill," responds Quillie, tossing back her yellow locks.

"Hallo! there is Mr. Brown's wagon," screams Fred; and Will shouts till the farmer responds with a smiling nod.

FRED'S STEAMBOAT.—Drawn by W. M. Cary.

FRED'S STEAMBOAT.—Drawn by W. M. Cary.

Soon they are all safely stowed in the wagon, and jolting over the well-remembered roads, an hour or more bringing them to the comfortable farm. Then what savages more wild than they in their gambols! They roam from one haunt to the other, visit the cattle and the poultry, and expect a welcome from all. Breakfast waits, but no one comes. Nurse has to go after them. There they are on an old hay wagon, which Fred has made into a steamboat by dragging out of the lumber-room of the barn a piece of stove-pipe, and Artie's flag at the stern. Julie has her doll, and Will has the puppy he claims already, but Quillie emerges from some other corner with two darling kittens. What can nurse do to get them in to Mrs. Brown's table, with its wild strawberries, its crisp radishes, its cream, and golden butter, and piles of brown-bread? She hits upon a happy plan.

"Children, if you will all come in this moment, I will tell you something splendid."

Their ears were pricked at once. "What is it, nurse? what is it?"

"Not a word more till you obey me."

They scrambled down at that, and hastened into the house.

Leadville, Colorado.

We live 'way up in Leadville, in the Rocky Mountains, ten thousand feet above the level of the sea. Although it is very cold here, some people live in tents all the year round. We live where we can see the snow on the range of the Rocky Mountains all summer. We have a little shepherd dog that eats candy. We like Young People very much, and watch eagerly for its coming. I am eleven years old, and Susie is ten.

Clara and Susie J.

Omaha, Nebraska.

We have a great many pets. We have a nice gray mare and a pony, both named Nell, and a little colt a week old that we call Cyclone. He is a cunning little fellow, and pretends to eat hay like his mother. We have lots of chickens of all kinds. I have some little white bantams, and my brother has some game bantams. My oldest brother keeps fancy chickens.

S. V. B.

Petaluma, California.

I read the letter of Arthur N. T. about gophers. They are very numerous where I live. I kill them sometimes, but they are very shy. I have a large gray cat that catches a great many of them. The wild flowers bloom here about the first of March. I take Young People, and like it very much. I learn lots of things from it, too. I live so far away that I do not get it till almost two weeks after it is published.

O. A. H.

Windsor, Connecticut.

I found a great number of flowers in May, but I do not think you will print my list of names, for mamma says it is too long, and would take up too much space in Young People. One day when I was hunting for flowers in the woods, I found a turtle marked "L. E. 1816."

Harry H. M.

We are pleased to see that you take such an interest in botany, for it is a beautiful study, but as your list contains the names of thirty-seven different flowers, it is a little too long to print, especially as many of them are given in the paper on "Easy Botany," in No. 29.

Laredo, Texas.

I live 'way out on the Rio Grande. I like to read the letters in Young People. I have two pet pigeons, one blue and one white. I would like to know how to catch and tame birds. My kite, which you told me how to make, was a success.

William C.

Troy, Ohio.

I had a water turtle that I wanted to pet. I kept it in a bucket of water, and it would swim round and round, and try to get out. When I would take it out, it would creep toward the river. I felt sorry for it, and my brother put it back in the river again. I tried Puss Hunter's recipe, and think it real nice. I am going to send a recipe for her club some time.

Bertha D. A.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Papa takes Young People for me, and I like it so much! I have a little sister who is very much interested in fancy-work, and she wishes to know if you will not give some instructions for making some fancy and at the same time useful articles for an old lady. I had some rabbits, and one bit me. I have tried Fanny S.'s recipe for caramels, and I like it very much. I have a little dog, but he eats very little. Can any one tell me what is the matter with him?

Tom G.

Lexington, Kentucky.

I take great pleasure in letting you know that I am one of the many readers of Young People. I am a little Scotch girl, but can remember nothing of my country. I have become crippled since coming to America, and I enjoy reading very much indeed. I wish Young People much success.

Maggie C.

Helena, Arkansas.

I wish to tell you of an entertainment which was given by our Sunday-school. We called it a Bazar, because we had ever so many pretty things, made by the Sunday-school children, to sell. There was a nice stage in the hall where we had the Bazar, and we had a pretty little exhibition. Some of us represented an art gallery. We had pictures and statues. I represented a statue. We made over one hundred dollars, and we are going to buy a new library for the Sunday-school with the money.

Julia S.

New London, New York.

I like the letters in Our Post-office Box best of all, and read every one of them myself, but as I am only six years old, I can not write very well, so I have asked mamma to write for me. My father has taken Harper's big paper many years, and when the first Young People came, I coaxed him to subscribe for it for me.

We live on a nice, pleasant farm in Oneida County, and have all kinds of domestic animals. My pets are a pair of pure white twin calves, just alike. My brother climbed a tall tree in the woods yesterday, and brought down four young crows, which he killed, and hung in the corn field to scare away the big crows.

Walter C. R.

The following letter will be welcome to the many inquirers for this little flower girl of the Pacific coast:

When my letter was published in Young People, I was away from home, and I have only just now seen it in print. I am sorry the prettiest flowers of the valley are gone, but I have a few pressed that I will send to each address, and I will ask some of my friends to send me some of the mountain flowers.

Genevieve Harvey,

Galt, Sacramento County, California.

My father has a nice cabinet of minerals, corals, shells, Indian relics, and other things. I would like to exchange spar of different colors, iron ore, and other minerals, with some little girls, for pressed flowers and shells. I have a great many flowers, and this fall, when the seed gets ripe, I would like to exchange flower seeds.

There is an abundance of lovely ferns here. Will you please tell me the best way to press ferns and flowers?

Edith Lowry,

Elizabethtown, Hardin County, Illinois.

Ferns and flowers should be laid carefully between two sheets of clean paper, the leaves artistically arranged in graceful shape, and placed under heavy pressure until they are dry. If the ferns are to be used for decoration, a warm iron, not too hot, must be passed over them, always putting clean paper between them and the iron, otherwise the heat of the room will curl them as soon as they are placed upon the wall. It is better not to iron them until they are dry, as the suddenly applied heat is liable to change the color of fresh ferns, causing them to look dull and faded. The sugar-maple leaf you send is well pressed, and beautifully varnished. What kind of varnish did you use? No doubt some little girls who are preserving leaves would like to know.

I would like to exchange postage stamps of foreign countries with some other boys who are readers of Harper's Young People.

Sidney St. W.,

326 East Fifty-seventh Street, New York city.

May 31, 1880.

I am making a collection of birds' eggs, and as soon as I collect a few more, I would like to exchange some with Samuel P. Higgins, if he will send me his full address. I have seen morning-glories in blossom this year, and would like to know if any other correspondents have seen them so early.

Thomas Horton,

Care of Benjamin J. Horton, Lawrence, Kansas.

If Mary Wright will send me some leaves, I will be very happy to send her some. And I would like to exchange flowers with Mabel Sharp, if she will send me some as soon as possible. I will send her some in return as soon as I receive hers. I would like to exchange leaves or flowers with any others who would like to do so. Those sending any will please mark each specimen distinctly, so that I may know the name. I am fourteen years old, and my pets are birds and flowers, which I will write about another time.

Ida P. Smith,

P. O. Box 380, Holyoke, Massachusetts.

I take Young People, and like it very much. I have two pigeons that laid eggs and hatched two little ones. I am making a collection of birds' eggs, and would like to exchange eggs with any of the correspondents of Young People. My address is No. 308 Carlton Avenue, Brooklyn, New York; but after the 25th of June I will be at Glen Cove, where I get almost all of my eggs. My name is T. Augustus Simpson, and my address this summer will be care of S. M. Cox, Glen Cove, Long Island.

T. A. S.

Rochester, New York.

I send a recipe for Puss Hunter's Cooking Club. It is for Florentines. Make a rich pie crust, using butter instead of lard; mix with cold sweet milk, roll it thin, spread it with butter, fold it, then roll it again into a sheet one-eighth of an inch thick; now spread it with jam, and place it in the oven. When it is baked, frost it; strew it plentifully with minced almonds or nuts of any kind; sift sugar over it, and place it in the oven a few moments to brown.

Winifred B.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I tried Nellie H.'s recipe for candy, only I used maple sugar instead of molasses, and I liked it very much. Here is another recipe for candy Puss Hunter may like to try: Six dolls' cups of sugar; one of vinegar; one of water; one tea-spoonful of butter, put in last, with a little pinch of saleratus dissolved in hot water. Boil, without stirring, half an hour, or until it crisps in cold water; flavor to taste, and pull it white with the tips of your fingers.

Sadie McB.

Aylett's Post-Office, Virginia.

I have never written to the Post-office Box before, and I thought now I would send Puss Hunter some recipes for her cooking club. I have tried hers, and I liked it very much. One of mine is for nice molasses candy: One quarter of a pound of sugar and one pint of molasses. Boil quickly, and drop a little in water occasionally until it crisps. A small piece of butter is an improvement. When done, cool it in buttered tins. Here is a recipe for Everton taffy: One pound of brown sugar; three ounces of butter; a little lemon flavoring. Boil about twenty minutes, until it crisps, stirring constantly.

Louisa W.

Cloyd D. B.—Write again, and tell us how you amuse yourself while you are sick, and we will try to print it. Your last letter was so much a business communication that we could not put it in the Post-office Box.

Jacksonville, Florida.

I saw a letter from Indian River, so I thought I would write too. I have a little sister, five years old, who goes to a Kindergarten school. I have a little turtle, and I would like to know how to feed it. I am almost nine years old.

Ralph D. P.

Turtles like a diet of flies, and small insects, and fruit. You will find directions for the care of different kinds of turtles in the Post-office Box of Young People No. 5 and No. 18. The "Letter from a Land Turtle," in Young People No. 27, will also give you information.

I thank Zenobia in regard to the whip-poor-wills, but she does not say when was the earliest she heard them this year. The first one I heard was on the morning of March 30, which is the earliest I ever heard one in this locality. Zenobia lives farther north than I do, and probably whip-poor-wills are not so early in her vicinity. I want to learn all I can of this mysterious bird, and would be thankful for any information concerning its habits. If Zenobia will send me her address, I would like to exchange pressed Missouri flowers for Illinois flowers with her. I have pressed flowers from California and Tennessee, and I have been studying botany this spring.

Wroton M. Kenny,

Pineville P. O., McDonald County, Missouri.

The whip-poor-will is a native of North America, and is found from the Pacific to the Atlantic. In winter it travels southward, and spends the cold season in the forests of Central America. It is a brownish-gray bird, and has a large mouth, armed with bristles at the base of the bill, with which it retains the moths and other soft-bodied insects upon which it feeds. It is a very shy bird, and hides itself all day, coming out at evening and early morning to skim along with noiseless flight near the ground, seeking its food. It is sometimes called the night-swallow. It makes no nest, but deposits two greenish eggs, spotted with blue and brown, in some snug corner, among fallen leaves, on the ground.

Elk City, Kansas.

My paper comes on Saturday, and I read all the letters in the Post-office Box first. I have a pet. It is a very funny one. It is a horny toad. I found it near Pocket Creek. I would like to know what to feed it with. Papa found a little bug this morning on the sweet-potato vines. It changes its color very often. Sometimes it is gold, sometimes green, sometimes red. Can any one tell me the name of it?

Mary W. (11 years old).

Your bug is probably one of the small iridescent beetles, of which there are many varieties. As they move about in the light, the color appears to change, like the color of the head and throat of a South American humming-bird. If the appetite of your horny toad is like that of a common toad, it will prefer an insect diet. But it will live weeks without eating anything, and unless you allow it to hunt for itself, it will probably die of starvation some day.

George H. M.—A neat black walnut box, about five inches deep, will make a good case for butterflies. Glue pieces of cork in the bottom, on which to mount your specimens, and have a tightly fitting glass cover. You must scatter bits of camphor in your case, to keep[Pg 487] away moths, as they destroy dried insects, and when your case is full, paste thin paper over the cracks to make it as air-tight as possible.

L. B. Post.—See Post-office Box No. 18.

"Admirer."—The Passion Play, which is celebrated once in ten years in the peasant village of Oberammergau, in the Bavarian Tyrol, is a relic of the ancient Miracle Plays and Mysteries which were so popular among the common people throughout Europe during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The Passion Play represents the closing scenes in the life of Christ, and sometimes includes, as it does this year, tableaux vivants of incidents in the Old Testament. Usually about five hundred performers appear on the stage, although the speaking roles number only a little over two hundred. All the characters are represented by the peasants of the village, the principal ones being selected fully two years previous to the performance, that they may become perfectly drilled in the parts allotted to them, and allow their hair or beards to grow to imitate as nearly as possible the best existing pictures of the various characters they are to represent. The theatre is an immense wooden structure erected for the purpose, capable of containing nine or ten thousand spectators; for, so widespread is the fame of this peasant festival that crowds flock to see it from every part of Germany, and travellers from England and the United States make efforts to be present at this strange performance. You will find a full account of the Passion Play in Harper's Magazine for January, 1871.

In errand. A poisonous reptile. A flower. A vegetable. In errand.

A. H. E.

My first is in May, but not in June.

My second is in lead, but not in copper.

My third is in day, but not in gloom.

My fourth is in ink, but not in water.

My fifth is in season, but not in year.

My sixth is in house, but not in tent.

My seventh is in hound, but not in deer.

My whole was an honored President.

M. B. and M. H.

First, a minute quantity. Second, a kind of tune. Third, wrath. Fourth, thoughts. Fifth, an ancient language.

Willie.

[From each sentence make one word.]

1. Ben has a foil. 2. I harm no cat. 3. I lent a dime. 4. The nice rain. 5. Harry, go past. 6. Shun fat flies.

A boy's name. A city in Japan. A vegetable. To ascend. One of the United States. A household article. A river west of the Rocky Mountains. Answer—Two Territories of the United States.

M. E. N.

My first is in brown, but not in green.

My second in candy is always seen.

My third is in lamb, but not in kid.

My fourth is in kettle, but not in lid.

My fifth is in lean, but not in fat.

My sixth is in rabbit, but not in cat.

My seventh is in modest, but not in meek.

My eighth is in cone, but not in peak.

My ninth is in cold, but not in freeze.

My tenth is in turnips, but not in peas.

My eleventh is in watch, but not in look.

My whole is the author of many a book.

Chesly B. H.

Favors are acknowledged from Philip D. Rice, May S., Matie Greene, J. S., Howard Starrett, Carrie Smith, Walter H., Jennie Hall, Alice G. M., Fannie W. O., Irene V. Over, Willie C. Pattison, Dorsey E. Coate, Charlie Iankes, Willie H. Joyce.

Correct answers to puzzles are received from Rebecca Hedges, Percy T. Jameson, M. S. Brigham, Harry Starr K., Willie Gray Lee, Julia Smith, Anne M. Franklin, Josie and Austin, Louie P. Lord, J. R. Blake, W. H. W., L. B. and R. H. Post, S. V. B., Marion E. Norcross, George S. Schilling, Cora Frost, Anna L. Kuhn, Leon M. Fobes, Mamie E. F., Eddie S. Hequembourg, Eddie A. Leet, "Blue Light."

Bolivar.

| C | O | R | D | O | V | A |

| P | A | R | I | S | ||

| R | E | D | ||||

| S | ||||||

| I | D | A | ||||

| G | H | E | N | T | ||

| G | R | A | N | A | D | A |

| M | ||||

| N | E | D | ||

| M | E | R | R | Y |

| D | R | Y | ||

| Y |

| B | I | D | E |

| I | D | E | A |

| D | E | A | R |

| E | A | R | L |

Raleigh.

| D | um | B |

| E | lih | U |

| F | athe | R |

| O | ttoma | N |

| E | uripide | S |

Defoe, Burns.

Charade on page 440—Courtship.

Harper's Young People will be issued every Tuesday, and may be had at the following rates—payable in advance, postage free:

| Single Copies | $0.04 | |

| One Subscription, one year | 1.50 | |

| Five Subscriptions, one year | 7.00 |

Subscriptions may begin with any Number. When no time is specified, it will be understood that the subscriber desires to commence with the Number issued after the receipt of order.

Remittances should be made by POST-OFFICE MONEY ORDER or DRAFT, to avoid risk of loss.

The extent and character of the circulation of Harper's Young People will render it a first-class medium for advertising. A limited number of approved advertisements will be inserted on two inside pages at 75 cents per line.

Address

HARPER & BROTHERS,

Franklin Square, N. Y.