Title: Harper's Young People, June 29, 1880

Author: Various

Release date: May 31, 2009 [eBook #29016]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire

| Vol. I.—No. 35. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | Price Four Cents. |

| Tuesday, June 29, 1880. | Copyright, 1880, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

It was a terrific storm. The wind swept down the river, raising a ridge of white water in its path. The rain came down harder, so the boys thought, than they had ever seen it come down before, and the glare of the lightning and the crash of the thunder were frightful.

"What luck it is that we got the tent pitched in time!" exclaimed Joe. "We're as dry and comfortable here as if we were in a house."

"Pick your blankets up quick, boys," cried Harry. "Here's the water coming in under the tent."

Joe had boasted a little too soon. The water running down the side of the hill was making its way in large quantities into the tent. To save their clothes and blankets the boys had to stand up and hold them in their arms, which was by no means a pleasant occupation, especially as the cold rain-water was bathing their feet.

"It can't last long," remarked Tom. "We're all right if the lightning doesn't strike us."

"Where's the powder?" asked Harry.

"Oh, it's in the flask," replied Joe, "and I've got the flask in my pocket."

"So, if the lightning strikes the tent, we'll all be blown up!" exclaimed Harry. "This is getting more and more pleasant."

The boys were not yet at the end of their troubles. The rain had loosened the earth, and the tent-pins, of which only four had been used, could no longer hold the tent. So, while they were talking about the powder, the tent suddenly blew down, upsetting the boys as it fell, and burying them under the wet canvas.

"Lie still, fellows," said Tom, as the other boys tried to wriggle out from under the tent. "We've got to get wet now, anyway; but perhaps, if we stay as we are, we can manage to keep the blankets dry."

The wet tent felt miserably cold as it clung to their heads and shoulders, but the boys kept under it, and held their blankets and spare shirts wrapped tightly in their arms. Luckily the storm was nearly at an end when the tent blew down, and a few moments later the rain ceased, and the crew of the Whitewing, in a very damp condition, crept out and congratulated themselves that they had escaped with no worse injury than a wet skin.

"Where are the rubber blankets?" asked Harry.

"Rolled up with the other blankets," answered everybody.

"It won't do to tell when we get home," remarked Harry, "that instead of using the water-proof blankets to keep ourselves dry, we used ourselves to keep the water-proofs dry. It's the most stupid thing we've done yet; and I'm as bad as anybody else."

"It was a good deal worse to pitch a tent without digging a trench around it," said Tom. "If I'd dug a trench two inches deep just back of that tent, not a drop of water would have run into it."

"And I don't think much of the plan of using only four pins to hold a tent down when a hurricane is coming on," said Joe.

"And I think the least said by a fellow who carries two pounds of powder in his pocket in a thunder-storm, the better," added Jim.

It took some time to bail the water out of the boat, for the rain and the spray from the river had half filled it. But the shower had cooled the air, and the boys were glad to be at work again after their confinement in the tent. They were soon ready to start; and rowing easily and steadily, they passed through the Highlands, and reached a nice camping spot, on the east bank of the river below Poughkeepsie, before half past five.

This time they selected a place to pitch the tent with great care. It was easy to find the high-water mark on the shore, and the tent was pitched a little above it, so as to be safe from a disaster like that of the previous night. Harry wanted it pitched on the top of a high bank; but the others insisted that, as long as they were safe from the tide, there was no need of putting the tent a long distance from the water, and that they had selected the only spot where they could have a bed of sand to sleep on.

This important business being settled, supper was the next subject of attention.

"We haven't been as regular about our meals as we ought to be," said Harry, "but it hasn't been our fault. We'll have a good supper to-night, at any rate. How would you like some hot turtle soup?"

"Just the thing," said Joe. "The bread is beginning to get a little dry; but we can soak it in the soup."

"About going for milk," continued Harry; "we ought to arrange that and the other regular duties. Suppose after this we take turns. One fellow can pitch the tent, another can go for milk, another can get the fire-wood, and the other can cook. We can arrange it according to alphabetical order. For instance, Tom Schuyler pitches the tent to-night, Jim Sharpe goes for milk, Joe gets the fire-wood, and I cook. The next time we camp, Jim will pitch the tent, Joe will get the milk, I will get the wood, and Tom will cook. Is that fair?"

The boys said it was, and they agreed to adopt Harry's proposal. Jim went off with the milk pail, and when the fire was ready, Harry took a can of soup and put it on the coals to be heated.

Jim found a house quite near at hand, where he bought two quarts of milk and a loaf of bread, and was back again at the camp before the soup was ready. He found the boys lying near the fire, waiting for the soup to heat and the coffee to boil.

"That soup takes a long time to heat through," said Tom. "There isn't a bit of steam coming out of it yet."

"How can any steam come out of it when it's soldered up tight?" replied Harry.

"You don't mean to tell me that you've put the can on the fire without punching a hole in the top?"

"Of course I have. What on earth should I punch a hole in it for?"

"Because—" cried Tom, hastily springing up.

But he was interrupted by a report like that of a small cannon: a cloud of ashes rose over the fire, and a shower of soup fell just where Tom had been lying.

"That's the reason why," resumed Tom. "The steam has burst the can, and the soup has gone up."

"We've got another can," said Harry, "and we'll punch a hole in that one. What an idiot I was not to think of its bursting! It's a good thing that it didn't hurt us. I should hate to have the newspapers say that we had been blown up and awfully mangled by soup."

The other can of soup was safely heated, and the boys made a comfortable supper. They drove a stake in the sand, and fastened the boat's painter securely to it, and then "turned in."

"No tide to rouse us up to-night, boys," said Harry, as he rolled himself in his blanket. "I sha'n't wake up till daylight."

"We'd better take an early start," remarked Tom. "We haven't got on very far, because we started so late this morning. If we get off by six every morning, we can lie off in the middle of the day, and start again about three o'clock. It's no fun rowing with the sun right overhead."

"Well, it isn't more than eight o'clock now; and if we take eight hours' sleep, we can turn out at four o'clock," said Harry. "But who is going to wake us up? Joe and Jim are sound asleep already, and I'm awful sleepy myself. I don't believe one of us will wake up before seven o'clock anyway."

Tom made no answer, for he had dropped asleep while Harry was talking. The latter thought he must be pretending to sleep, and was just resolving to tell Tom that it wasn't very polite to refuse to answer a civil question, when he found himself muttering something about a game of base-ball, and awoke, with a start, to discover that he could not possibly keep awake another moment.

The boys slept on. The moon came out, and shone in at the open tent flap, and the tide rose to high-water mark, but not quite high enough to reach the tent. By-and-by the wheezing of a tow-boat broke the stillness, and occasionally a hoarse steam-whistle echoed among the hills; but the boys slept so soundly that they would not have heard a locomotive had it whistled its worst within a rod of the tent.

The river had been like a mill-pond since the thunder-storm, but about midnight a heavy swell rolled in toward the shore. It came on, growing larger and larger, and rushing up the little beach with a fierce roar, dashed into the tent and overwhelmed the sleeping boys without the slightest warning.

"Mamma," said one of my boys to me (they are "grown-up boys," but they take great pleasure in the weekly arrival of the Young People), "why don't you write a communication to the editor, and tell him how papa once saw a live toad in a slab of rock that had just been blasted?"

"Perhaps the editor would not believe me," I replied. "It seems a doubtful point among geologists and naturalists, and he says the fact has never been certified to by any scientific man."

"Well, wasn't papa a man of science?"

"No; he was a young civil engineer, with only science enough to be employed on the first surveys and construction of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. But he is one of the most accurate observers I have ever seen, and so careful in his statements that, as you know, he relates even a common fact as cautiously as if he were giving evidence in a court of justice."

"Well, I should like to hear it over again. Tell me the story."

"Your father was, as I said, a young engineer superintending the construction of the line of road west from Sir John's Run, near Berkeley Springs, in West Virginia. His men were engaged in blasting a mass of very hard rock—gneiss, he called it—which ran across the line. Coming up to where they were at work, immediately after a fresh blast, he found the block that had just been detached lying on the ground. It was a mass of stone about as large as the chair you are sitting on; the surface where it had just been severed from the parent rock was perfectly smooth, except that about the middle of it appeared a reddish blister, about the size of half an egg. This attracted your father's notice. He was curious to see what it could mean, and taking up a hammer that was lying near, he tapped upon it gently. It cracked like an egg-shell, and out came a toad, which moved rather feebly, was very weak, extraordinarily thin, and covered with a sort of red rust. He did not, however, live more than a few minutes. Whether the blow with the hammer had hurt him, or whether the fresh air was too much for him, nobody ever knew. He died, and there being no professional naturalist on the spot, his body was not preserved. The men of the gang gathered around his death-bed, and the contractor had some marvellous stories to tell of things of the kind he had met with in his experience.

"The spot where the toad lay in the slab of rock was probably, your father thought, about five feet from the surface, but he could not say with certainty. He was sure there was no fissure or opening in it communicating with the outer air."

"I should think, mamma, you would be glad the readers of Young People seem to be taking an interest in your friends the toads."

"So I am. I liked and protected them, for the sake of their beautiful eyes, long before I found out how useful they are in a garden. You recollect I used to tell you of a lady who had a splendid bed of mignonette one year, and the next had no mignonette at all, because her cruel gardener had killed off all the toads?

"A toad's eyes are the only things in nature which could not be represented without using gold. I fancy that the toad's eyes are the origin of the superstition about the 'precious jewel in his head.' As to their being poisonous, as the French peasants say, or making warts, as the old mammies tell us, that is pure nonsense. I have handled hundreds of them. Their tongues are as curious as their eyes are beautiful. The root of the tongue is just behind the under lip, and it folds backward.

"When Mr. Toad sees a fly, he darts his long and active tongue out so quickly that it is hard to see him do it, and jerks the fly alive down his wide gullet.

"Do you remember watering Darby and Joan, who have lived twenty years under our porch, when you were little boys? You thought they seemed to enjoy a rain so much that you would give them a shower. Poor Darby and his wife realized the proverb, 'It never rains but it pours.' A gentle, steady rain was agreeable enough; but you floated them out of house and home, and I do not think they ever resettled in the same spot.

"There is a charming story about a toad, called Monsieur le Vicomte."

Now is the time when hither and yon

Our city-people run

Seeking a home. And here, close by,

Is the prettiest under the sun.

So dainty it is, so cozy and fresh,

Its walls in a marvellous way

Are covered all over with tapestry

In yellow and green and gray.

The ceiling is frescoed in light and shade,

And the cottage stands so high

That the view extends to the mountains dim,

Whose peaks are lost in the sky.

No window it has, but an open door

Invites one to sweetest rest;

For my wee house, perched on a swaying elm,

Is only an oriole's nest.

LITTLE JENNIE AND THE GARDENER.

LITTLE JENNIE AND THE GARDENER.

While the children were waiting for the Professor one bright summer morning, they overheard through the open window little Jennie asking John Grant, the gardener, "Where do the flowers come from?"

"Why, don't you see?" said he; "they grow up out of the ground."

"How do they grow?" continued the little questioner, whose curiosity was clearly on the increase.

Before John could collect his wits sufficiently to frame an answer, the Professor made his appearance with a pretty rose-bud in his hand.

"Will you not tell us," said Gus, "how flowers grow? There's John out there digging among them all day, but he seems to know nothing about them, after all."

"Oh yes, he does," said the Professor; "I presume he knows more about them, in a practical way, than either you or I. He can take care of them through the winter, and train them, and get them early into bloom, far better than I could, I am sure. But very likely I know more of what the books have to say on the subject, and can more readily find words to express what is called the theory in the case. The growth of plants has given rise, perhaps you know, to the science of botany."

"Please don't be very scientific," pleaded Gus, "but tell us in a plain way how they grow."

"Well, let us begin with the seed. In the first place, the sun warms the ground in which the seed lies buried. Then the seed swells and bursts, and sends downward a little root; the root drinks in the water from the soil, and so gets larger, and spreads around; and by-and-by it sends up a stem above the ground. As soon as the sunlight falls on the little plant, it gets stronger, and is able to take food as well as drink from the soil, so as to get its full shape and size and green color."

"Has it a mouth to eat and drink with?" asked Gus, in some doubt.

"Yes, a great many mouths scattered all over the root, or on very little branches reaching out from it. While it is under-ground in the dark, it is thirsty, and cares only to drink water; but as soon as it comes up, and has enjoyed the light and heat of the sun, it begins to get hungry, and takes in solid food with the water. The fresh air and sunshine sharpen its appetite, just as they do in our case."

"The little spring flowers seem to come up so suddenly," said Joe, "as if they did all their growing in one night. We don't see them at all until they are standing in full bloom."

"It takes them some days to develop and blossom," said the Professor. "The stem rises slowly from a little point, getting longer and longer, until it reaches its full size. Shrubs and trees begin in the same way, mounting upward until they reach their proper height. If you examine the ground closely, you will find plenty of little plants just peeping out. Most of them are grass, and keep on about the same as they begin; but some change very greatly, and take all kinds of shapes and directions. They soon put out their leaves, one by one, or two by two, along the stem, short spaces apart. Just above the leaves, in the larger plants, branches start out, and grow much like the stem, with their own leaves."

"How do the flowers come?" asked Gus.

"Sometimes they grow on a little stem of their own, called a scape, that springs up separately from the root. But usually the main stem or one of the branches is changed into a flower-stem. Now suppose we cut this rose-bud in two, and then I can show you."

"Please, Professor," said May, "don't cut the poor rose-bud. There is a book down stairs with one in it cut in two."

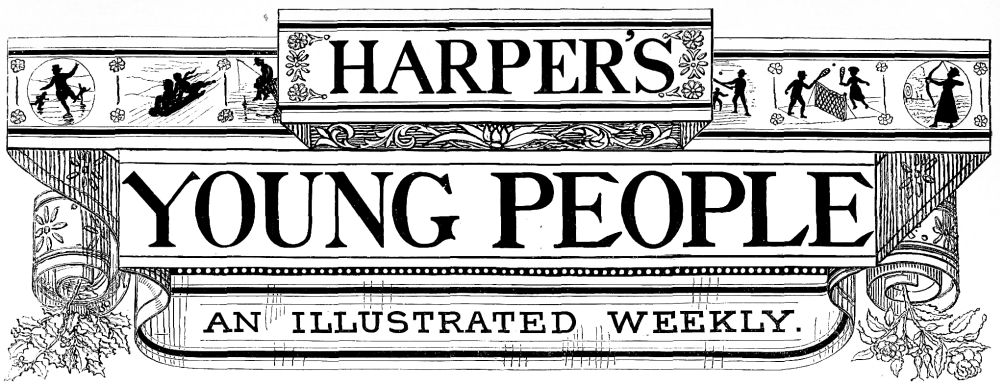

ROSE-BUD CUT VERTICALLY.

ROSE-BUD CUT VERTICALLY.

Gus brings the book, and the Professor exclaims, "That is what I want exactly. Here are lines pointing to the parts; and now I'll explain them. You see, S is the sepals."

"What are they?" asked Joe.

"The sepals are the outer covers of the flower. They lie all over and hide it when it is in the bud, but are folded back when the bud opens. There are five, which is a very common number for flowers to have. Some have only two or three, others none at all. The petals are marked L. They are the gayly colored parts that lie next to the sepals, and inside of them. Sometimes the petals are separate from each other, and sometimes all fastened together. They are also called the corolla, which means a little crown, and are the showiest portion of the flower. Wild flowers are apt to have only one row of petals, but those cultivated in gardens often have a large number. The good care that they get has the effect to make them deck themselves out with more petals, which are the parts chiefly admired for their brilliancy."

"What are these little threads near the middle?" asked Joe.

"They are called stamens. In the picture they are marked P. Inside of them, in the very centre, is what are called the pistils, T. Down below them are the seeds, in the middle of what becomes the fruit, as you have noticed in an apple or pear, which is somewhat like a rose when ripe, though very much larger. After the petals have fallen off the rose, the part that is left gets ripe with the seeds inside, just as if it were an apple or a pear."

FISHERMAN'S LUCK.

FISHERMAN'S LUCK.

"What do you say to Ned's taking a ride up to Miss Pamela's to-morrow?" said Mr. Weatherby to his wife.

"How? All by himself? A ride of twenty miles?"

"On horseback. Yes. Yes. Does that answer your three questions satisfactorily? Now I'll ask one. Why not?"

"Oh, I suppose there is no objection, only he has never taken such a long ride alone."

"Why, mother! I, a great fellow of fourteen! Of course I can go—that is, please let me. What for, father?"

"I have had a little dividend of fifty dollars paid in on Miss Pamela's morsel of horse-railway stock, and I know she always wants money as soon as it comes."

"Probably much sooner, poor soul—" said Mrs. Weatherby.

"Unlike most other people, eh, ma'am?" interrupted Mr. Weatherby.

"—and more than ever now, since she has taken those two girls of her good-for-nothing brother's. If they had been boys, they might have been some use on her mite of a farm. When I said so to her, she said: 'Yes, my dear, that's just the reason their mother's family don't want them; but, you know, girls have to live as well as boys. We're pretty sure of getting enough to eat, and as for the rest, I believe the Lord will provide.'"

"Her faith will be rewarded just now," said Mr. Weatherby, "for this is an unlooked-for dividend. The road has been doing better than usual of late."

"I'm very glad," said his wife. "I dare say it will be a real godsend to them all."

"I'll be off early in the morning," said Ned.

"All alone, and carrying money!" said his brother Tom, with an ominous shake of the head.

Ned did feel a little like a hero as he started on his long ride through a thinly settled country, and over a road passing through miles of thick woods. His suggestion that it might be well to carry a revolver had been smiled at by his father, and frowned down by his mother, and he had to confess to himself that he felt a little safer without it. His half-desire for just a trifling adventure was not to be gratified, for as noon approached he drew near Miss Pamela Plumstone's quaint old farm-house, and was soon warmly welcomed by that sprightly lady.

"Why, Master Ned, I am delighted! How good of you! Didn't you find the roads very bad? And how is your mother and the twins? And has your father quite got over his rheumatism? And when is she going to get out to see us again?"

"Very well, thank you. Yes, ma'am. No'm. Just as soon as the roads get settled, she says," said Ned, attempting to answer her rather mixed questions, as he perceived by her pause that she expected a reply.

"And what a fine big fellow you've grown to be, Master Ned! I am astonished to see how you improve."

Ned fully agreed with her, but modestly refrained from saying so, and made known his errand. How poor Miss Pamela's face shone!

"Oh, my dears, come here," she cried, running to a door. "Do come here and see what has come to us."

Ned looked curiously at the two girls who came in answer to her call. They had become inmates of Miss Pamela's home since his last visit to her, and he had never seen them before.

"The youngest one looks as if she might be pretty," he said to himself; "but how funny they do look!"

They did look funny. Miss Pamela's only ideas on the subject of dressing little girls were drawn from her memories of what she herself had worn forty years ago. Their pantalets reached almost to their heels, and their gingham aprons were almost as long, and cut without a gore. Their hair was drawn tightly back, and braided in two tails, those of the older one being long and dangly, and of the other short and stubby.

"See here, my dears," again exclaimed Miss Pamela, "here is some money I didn't expect. Didn't I tell you, Kitty Plumstone, that Providence would send you some new music somehow? She plays on the piano, Master Ned; I really do think she is going to make quite a musician. I teach her myself, you know. I can't play any more because of the stiffness in my fingers, but Kitty can play 'Days of Absence,' and 'Come, Haste to the Wedding,' already."

Ned was expressing pleasure at this pleasing proficiency, when Miss Pamela bustled away with a few words about dinner, which sounded agreeably to him after his ride.

A long ramble afterward on the farm, in company with the funny-looking girls, proved them to be as genial and companionable as they could have been had their dress included all the modern improvements, although Ned, who was rather critical in such matters, still thought it a pity they could not have blue streaks on their stockings, ruffles somewhere about them, and wear their hair loose.

They knew where the late wild flowers and the wild strawberries grew, and where the birds built their nests. They gathered early cherries, and promised Ned plenty of nuts if he would come in October. They had tame squirrels and rabbits penned up in the wonderful old ramshackle building which did duty as barn, stable, carriage-house, granary, and general receptacle for all kinds of queer old-fashioned lumber, the accumulations of many years. They were poultry-fanciers, too, in a small way; had a tiny duck-pond at one corner of the barn, where the great sweep of roof sloped down almost to the ground, forming a shed, and they all climbed upon it, and watched a quacking mother as she introduced her first brood of downy little yellow lumps to their lawful privileges as ducklings. And all agreed (the girls and boy, that is) that it was much nicer to be young ducks than young chickens; and there is no reason to doubt that the young ducks thought so too, as they realized the delights of the cold-water system.

But all agreed that nothing came up to the bantams—the proud little strutting "gamy" (Ned said that) roosters, all bright color and ambitious crow, and the darling wee brown mothers, scarcely larger than quails, whose cunning babies were no bigger than a good-sized marble. Kitty promised Ned a pair when they should be grown.

After tea he was called upon to admire Kitty's playing, but his praises of her performance were interrupted by Miss Pamela's profuse apologies for the condition of the piano.

"It is so terribly out of tune, you see, Master Ned." He was evidently looked upon as something of a critic in music. He rather liked to be so considered, and thought it unnecessary to assure them he knew nothing about it. The old piano sounded to him very much like the bottom of two tin pans mildly banged together; but if it had been a much better instrument, it would have been all the same to his unmusical ear.

"Oh, it sounds very well, I assure you, Miss Pamela," he said.

"You see," went on the lady, "it hasn't been tuned for four years or more. Mr. Scrutite went about the country for many a year tuning pianos; but he got old, and the last time he came he left his tuning key, or whatever you call it, saying he'd be round again if he could; but he never came. It's such an expensive thing, you know, to bring a man twenty miles to do it, that I've been putting it off, and putting it off. But we'll have it done now, eh, Kitty?"

"Why, Miss Pamela," said Ned, "I'll do it for you, if you have the thing they do it with."

"You, Master Ned? Can you tune a piano?"

"Well, I never did tune one, but I know exactly how they do it. I've seen Professor Seaflatt tune my mother's ever so many times."

"Oh, I'm sure you could do it, if you really feel as if you could take so much trouble; it would be a great kindness to us."

"Of course I'll do it, with the greatest pleasure in the world, ma'am. Let me see— I am to go home to-morrow afternoon; I'll do it the first thing in the morning." And rash Ned went to rest on Miss Pamela's feather-bed, in a room smelling of withered rose leaves. The bed was hung with old chintz curtains; the wall-paper displayed a pattern of large faded flowers. The swallows made a soft twittering in the wide chimney, as he closed his eyes with a glow of satisfaction at the thought of the kind action (and very clever one, too!) he had undertaken to perform.

He found it harder than he had expected. The screws were rusty and hard to move, and the tuning key was old, and would slip. But before noon he announced his task completed, and Miss Pamela and her two nieces gathered near, their faces beaming with interest.

The piano was small and narrow, with legs so thin as to suggest to Ned that it needed pantaloons. It had been the pride and glory of Miss Pamela's girlhood, and was still, in her eyes, an excellent and valuable instrument, although she, being of a modest turn of mind, was willing to acknowledge that it had probably seen its best days.

"It will be so nice to have it in good tune again!" she said, in a tone of great satisfaction. "I declare, Master Ned, what a thing it is to have such advantages as you boys are having!—to be able to turn your hand to 'most anything! Now, then, Kitty, play 'Days of Absence.'"

Kitty played it. But what could be the meaning of that fearful jumble of strange sounds? Surely that time-honored melody (modern hymn-book, "Greenville") never sounded so before. What was the matter? Miss Pamela's face fell a little, but she still smiled, and said,

"You had better get your notes, Kitty; you are playing carelessly."

Kitty got her notes, and played carefully, but the result was still, to say the least, most astonishing and unsatisfactory.

"Try 'Come, Haste to the Wedding,' then." But the jig ran riot to such an extent that Kitty lost her place, stumbled, and finally came to a dead stop.

Poor Miss Pamela listened with a face of deepening dismay, while Ned stood still, with cold chills running down his back, as he was suddenly struck with the appalling idea that he might have undertaken something entirely beyond his abilities, and that the ruin of the cherished old piano might be the possible dreadful result.

"Try a scale, Kitty," again suggested Miss Pamela, with a polite effort to look tranquil.

Oh, that scale—what capers it cut! what unheard-of combinations of fearful sounds it was guilty of! Up and down it jumped and flourished, careering about in a manner as far as possible removed from that of a sober, well-conducted scale. Bass notes and treble notes ran against each other; high notes and low notes played leap-frog—they groaned, shrieked, and wheezed in a horrid discord, which could not have been worse if a thousand imps had been let loose in the old oaken case.

Did you ever see an intelligent dog with a rustling paper ruffle tied round his tail, paper shoes on, and a fool's cap on his head? and as everybody laughed at him, and he knew they were doing so, do you remember his reproachful look of helpless, indignant protest against being made to appear ridiculous in spite of himself?

Just such an expression we may imagine that poor old piano would have worn, to any one who could have taken in the full absurdity of the position. A venerable instrument like itself, after thirty-five years of honorable service, thus to be forced to exhibit a levity so unbefitting its age and dignity!

"Well," and Miss Pamela sank into a chair, "it's very strange—very strange indeed."

Poor Ned was red-hot with mortification and chagrin. He certainly was to be pitied. It was very trying indeed to have been led into such a scrape by his boyish over-confidence in his own powers, and a real desire to do a favor. Even through her own surprise, and her distress at what she feared might prove a lasting injury to her precious old piano, Miss Pamela felt sorry for his embarrassment.

"Never mind, Master Ned," she said, in a kindly tone. "I dare say the tuning key was too old, or perhaps you understand modern pianos better. I don't believe any real harm is done, and you know I was going to have it tuned with some of the money you were so good as to bring me, so you see I am no worse off than I was before."

As she left the room, Kitty buried her face in her big gingham apron.

"Oh, Kitty, don't cry!" exclaimed Ned, his trouble greatly increased, if that were possible, by her evident emotion. "Kitty, I'll have it fixed the first thing—you see if I don't! I know it can be fixed."

Kitty raised her head, and Ned was wonderfully relieved at seeing that the tears in her eyes were caused by suppressed laughter.

"Oh, Ned, it's so funny!" she half whispered. "If Aunt Pamela knew I laughed, though, she would never forgive me."

"Kitty, what is the matter, anyhow?" asked Ned, pointing to the piano.

"Why, I don't know. Don't you know? I thought you knew all about music and pianos."

"No, I don't, Kitty," said Ned, in a burst of remorseful frankness. "I'm the only one of the family that don't. The only things I could ever sing were 'Greenland's Icy Mountains' and 'Oh, Susannah' (that's a song mother used to sing to us children), and I always got them mixed up, because they begin just alike; so I never dare to sing 'Greenland's Icy' in church."

Kitty's words of comfort were as kind as those of her aunt, but Ned felt very anxious to get away from the scene of his discomfiture, and was glad to find himself at last on the road home, where he arrived in due season, finding the family at tea. It was not until he was alone with his father and mother that he unburdened himself.

"Father," he began, with some effort, "will you allow me to send a person at your expense to tune Miss Pamela's piano?"

"At my expense? Well, I should want first to know why you ask it."

"The fact of it is, sir, I undertook to tune it myself, and—well, I'm afraid I made a bad business of it."

"You did what?" asked his mother, turning on him a look of such comical amazement that he could not help laughing, although he turned redder than before.

"I tuned her piano."

"Where did you ever learn to tune a piano? I always thought you had no ear for music."

"I didn't do it with my ears, I did it with my hands, and it was hard enough work, too. They are all blistered, and my wrists ache, and I am as lame all over as if I had been sawing wood all day."

"How did you do it? and, in the name of all that is ridiculous, why?" gasped his mother.

"Well, I did it just as I've seen Seaflatt do yours. I screwed every wire up as tight as I could, and kept on fiddling with the other hand on the key to see if it kept on sounding, just exactly as he always does."

Ned never forgot the peal of laughter which came from his parents. Both keenly relished the joke, and when Ned learned that what he had done could easily be undone, he felt so much relieved as to be able to laugh with them.

"Yes," said his father, emphatically, when he could recover his voice, "I think you had better send Seaflatt up to Miss Pamela's as soon as possible, and set her mind at rest."

"And, oh, Ned," said his mother, "if ever you tune another piano, may I be there to see—and hear!"

"If ever I do, ma'am," he answered, with a vigorous shake of the head, "I hope you may."

At three o'clock Tuesday morning, December 11, 1688, James II., King of England, rose noiselessly from his bed, passed with stealthy steps from his palace, entered a carriage in waiting, and was driven rapidly to the bank of the Thames, where he stepped into a boat, and was rowed swiftly down the stream. As the boat shot past the old palace of Lambeth, he flung into the river the Great Seal of England, used in stamping all the royal documents to give them validity. He was fleeing from his palace, his throne, his kingdom, and from people whom he had outraged in his attempt to set up an absolute and personal government—to do just as he pleased without regard to law. He believed that the King had the right to be above all laws. The people had risen against him, and had invited his son-in-law, William of Orange, to come over from Holland to aid them in overthrowing James. William had landed at Torbay, and had been so warmly welcomed that James was seeking refuge in France with Louis XIV., whose adopted daughter, Mary of Modena, as she was called, was James's wife.

"You are still King of England, and I will aid you in securing your throne," said Louis XIV.

It was not simply a generous act on the part of Louis to a fellow-sovereign who was in trouble, but there were ideas behind it. Louis XIV. believed with James in the absolute right of kings to do just as they pleased: that the people must do their bidding.

"The state—it is me!" said Louis, striking his hand upon his breast, to indicate that there was nobody else who had a right to say or do anything in regard to law and government.

The people of England, on the other hand, believed that they had the right to make their own laws through a Parliament of their own choosing, and that it was the duty of the King to obey and execute those laws.

James had done what he could to crush out the Protestant religion in England; Louis had driven the Huguenots, who were Protestants, from France, waging a cruel war upon them. Thousands had been killed. More than eight hundred thousand had been compelled to flee to other countries. The war was waged not merely that James might regain his crown, but it was a great struggle for civil and religious freedom. It extended to other countries: battles were fought on the banks of the Rhine, the Danube, the Po; in the meadows of Holland; on the plains of Germany; amid the vineyards of Italy; in the wilderness of North America; on the Penobscot, Piscataqua, Merrimac, and Mohawk.

All through the years Jesuit priests had been laboring to convert the Indians of Canada to Christianity, and had made them the allies of France. When the war broke out, all the Indians in Maine and New Hampshire sided with the French.

The English, especially the men who bought furs of the Indians, had not always treated them justly.

The traders cheated them when buying their beaver skins. They would put the furs on one side of the balance, and bear down the other with their hands, saying a man's hand weighed a pound. The Dutch fur-traders on the Hudson used their feet instead of their hands. The simple-hearted red men, knowing nothing of balances and weights, could only look on in astonishment, wondering at the lightness of the skins. The Indians of Maine and New Hampshire had a grudge against Major Waldron, who lived at Dover, New Hampshire.

"His hand weighs too much," they said.

But they had another and greater grievance. To understand it we must go back a little.[Pg 496]

In 1675, Philip, who lived on a hill overlooking the peaceful waters of Narragansett Bay, begun war upon the English, which lasted nearly two years, during which the New Hampshire Indians murdered some of the settlers. The Governor of Massachusetts sent Captain Sill and Captain Hathorn, with their two companies of soldiers, to seize all the Indians, although only a few had taken any part in the murders. Major Waldron invited the Indians to come to Dover; and they, regarding him as their friend, came from their wigwams along the lakes and rivers, to see what he wanted.

"Let us have a sham fight," he said.

The Indians agreed to it. They ranged themselves on one side, their guns loaded with powder only, and the white men on the other.

"You fire first," said Major Waldron.

The Indians fired their guns in the air, and the next moment found themselves surrounded by the white men, who made them prisoners, taking away their guns, putting them on board a vessel, sending them to Boston, and selling two hundred of them into slavery.

One Indian made his escape from the soldiers, ran into Elizabeth Heard's house, and the good woman secreted him in the cellar, and saved him from being sold into slavery.

The war between England and France began. The Jesuit fathers were making their influence felt among the tribes, winning them to the side of France.

Previous to this the Indians had made themselves at home in Dover, coming and going as they pleased. There were five strongly fortified houses in the town, in which the settlers slept at night.

It was the evening of the 27th of June, 1688, when two squaws called at Major Waldron's garrison, and asked if they might sleep there.

"Indians are coming to trade to-morrow," they said.

Major Waldron was pleased to hear it, for trade with the Indians always meant a good bargain to the white man.

"Supposing we should want to go out in the night, how shall we open the door?" asked the squaws.

They are shown how to undo the fastenings.

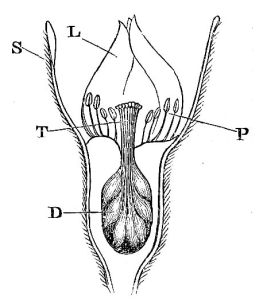

MAJOR WALDRON'S TERRIBLE FIGHT.

MAJOR WALDRON'S TERRIBLE FIGHT.

Major Waldron is eighty years of age, white-haired, wrinkled, but there is force yet left in his arm, and he is as courageous as ever. He has no fear of any Indian that walks the earth, and the vague rumors and whisperings of an uprising are as idle as the wind to him. He lies down to sleep. The lights in all the houses are extinguished. No sentinel walks the street. In the darkness dusky forms glide noiselessly through the town. The doors of the houses open. The terrible war-whoop breaks the stillness of the summer night. A half-dozen Indians burst into the room where the brave old man is sleeping. He springs from the bed, seizes his sword, and single-handed drives them from his chamber into the large room. In the darkness one steals behind him, strikes a blow, and he falls. It is their hour of triumph. He has been a ruler and a judge. The Indians can be sarcastic. They seat him in his arm-chair, lift him upon the table. It is his throne.

"Get us supper," is their command to the family.

They eat, and then turn to their bloody work. One by one they slash their knives across his breast.

"So I cross out my account," they say. They are settling an account that has been standing thirteen long years.

An Indian cuts off one hand. "Where are the scales? Let us see if it weighs a pound."

One cuts off his nose, another his ears. The old man's strength is gone, and as he falls, one holds his sword, so that it pierces his body.

In one of the garrisons is a faithful dog, whose barking awakes the inmates. The Indians rush upon the door. Elder Wentworth throws himself upon the floor, holds[Pg 497] his feet against it, and braces himself with all his might. The bullets whistle over him, but do him no harm, and he holds it fast, keeping the Indians at bay, and saving the lives of those within.

Elizabeth Heard and her children on this evening have come from Portsmouth in a boat. They are belated, and the Indians are at their bloody work when they arrive. Her children flee, while she sinks in terror upon the ground. An Indian with a pistol runs up and stands over her, but he does not fire.

"No harm shall come to you," he says. He permits no one to touch her. It is the Indian whom she befriended thirteen years ago.

When the morning dawns it is upon the smouldering ruins of burning dwellings, upon the mangled bodies of twenty-three men and women, and upon twenty-nine women and children going into captivity—a long weary march through the woods to Canada to be sold as slaves to the French, or kept as prisoners by the savages. Yet amid the ghastly scene, through the blood and flame and smoke and desolation, there is this brightness—the remembrance of the kindness of Elizabeth Heard, and its reward.

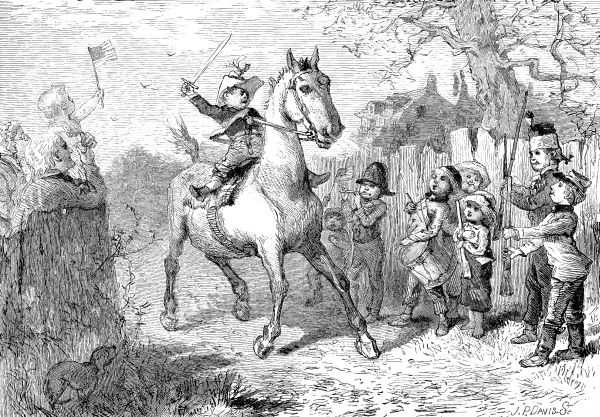

REVIEW OF THE CAVALRY BY THE INFANTRY.—Drawn by Sol.

Eytinge, Jun.

REVIEW OF THE CAVALRY BY THE INFANTRY.—Drawn by Sol.

Eytinge, Jun.

"What did George Washington do, I wonder, on the Fourth of July?" said Harper Smith, rattling his tin money bank with an awful din.

"Mercy! I don't know," said Aunt Nancy, shielding her ears, and thinking twice as much about the noise as she did about the question. "Do pray be still! I'm sure I wish there wasn't any Fourth of July."

"Oh, Harp, you ninny!" cried his brother Joe. "There wasn't any Fourth at all till George Washington made it."

"You better study up," said Aunt Nancy, coming to her senses, as Harper, very much confused, stopped the rattling. "You don't begin to realize what the guns and the fire-crackers and the torpedoes, and all the other dreadful things that blow up people and knock off boys' fingers and toes, are for. It would be a great deal better if boys had more history in their heads and less money in their pockets. That's the way to celebrate, I think; and I mean to ask your father about it."

"Oh, don't, don't, Aunt Nancy—please don't!" cried both boys, in the greatest dismay, while Lucy ran in from the next room, with wide-open eyes, at the uproar. "Don't make father take away our money; we always have it, you know."

"You can have your money," said Aunt Nancy, putting up her spectacles to look at their distressed faces, and beginning to laugh at the sight; "but you ought to know what you're spending it for. I would, I know, be able to tell something about my country, and who fought for it."

When Mr. Smith came home the boys were both out in the barn, looking at a very new colony of kittens in an old barrel. So Aunt Nancy had about five minutes of peace and quiet, which she speedily made the most of, I can assure you—talking away so fast that Mr. Smith had to follow her pretty closely, with eyes as well as ears on the alert.

When she had finished, "Capital," was all he said. And then the boys came tearing in, and they had tea.

After supper, "Now for a story," cried Joe, getting possession of the chair next to Mr. Smith, while Harper flew for another.

"When does Fourth of July come?" asked Mr. Smith, abruptly.

"It's three weeks from day after to-morrow," cried Joe, springing up, and running for the almanac.[Pg 498]

"Weill, what are you going to do on the Fourth?" said their father.

"Oh, everything," cried Joe, while Harper came in on the chorus; and Lucy beat a soft little tune on her father's shoulder with her hand.

"You said you'd give us more money this Fourth," cried Harper, seeing his chance. "Don't you remember? 'Cause we're bigger, you know."

"And so you'll try to blow off your heads harder than ever, I suppose," said Mr. Smith, with a twinkle in the eye next to Harper. "And then who's to pay the doctor's bills, I wonder?"

"If our heads were off, we wouldn't have to have the doctor," suggested Joe, dreadfully afraid the money wasn't coming.

"True enough," laughed his father. "Well, heads stand for everything else—all the hurts, I mean."

"I ain't goin' to blow off my head," declared Harper, getting up in an anxious way, and standing in front of his father. "Say, father, I promise you I won't. Do give us the money—do."

"Do you want more than you had before?" asked his father, pulling his ear.

"Yes, sir," emphatically declared Harper, all out of breath from his exercise; "I want forty cannons."

"Mercy!" ejaculated Aunt Nancy, in smothered accents, over in the corner by the window, with her mending basket.

"Well, then, I'll tell you how you can get it," said Mr. Smith, speaking very earnestly, and fastening his eyes intently on their faces.

"Really, papa?" cried Lucy, sitting up straight on his knee.

"Really," said Mr. Smith, bringing his hand down on the arm of his chair with convincing emphasis. "And I don't mind paying money for such an object—it's well spent, I can tell you. Now, boys, see here—and Lucy too;" and he leaned forward and began to talk in a way that made the children see that this was no funning, but sober earnest, every word of it. "If you all go to work for three weeks, beginning to-morrow morning—all the time you get out of school, I mean—and study up everything you can get hold of that concerns the history of our country: what Fourth-of-July's for, and all that; who made the country what it is, so that we can celebrate and bang away, and play with powder and guns— Stop! I haven't got through," as he saw both boys' mouths fly open to launch numberless questions at him. "Begin at the very foundation; get all the information you possibly can; find out all the names of the Presidents, for one thing, and all about the establishing of Congress; most of the principal battles, and all that—why, then, three weeks from to-morrow night, the one who knows the most, and can tell it in a sensible way that shows he knows what he's learned, and not like a parrot, he shall have the most money. And it shall be a large sum, I promise you, compared to what you had last year. That's all. Now you may speak." And Mr. Smith leaned back in his chair, and burst into a hearty laugh at the tumult he had raised around his ears.

At last Harper, in a lull of questions and answers that were flying back and forth, turned and fixed a reproachful glance over in the direction of the big mending basket. "'Twas all Aunt Nancy," he cried. "Oh dear! And she wasn't never a boy. And she don't know how we want things, she don't."

"We never can do it," cried Joe, in despair.

"Never's a long word," cried Mr. Smith, briskly. "Begin to-night. Come, boys, get out the maps, and we'll start right off, now, this very minute;" and he jumped up, and began to roll the big table up closer to the window.

"And I'm goin' to get that awful old history," cried Harper, rushing out, full of enthusiasm; "that'll tell lots."

"Do," cried his father, approvingly. "Go along too, Joe and Lucy, and get all the books you can; then we'll see."

So in two or three minutes three happy and excited children sat around the table, while their father showed them how to begin, explained the hard parts, and pointed out places on the map, while Aunt Nancy, over in the corner, smiled and nodded to herself more than ever.

All of a sudden a voice broke in on the absorbed group: "And I'm going to have a finger in this Fourth-of-July pie; so you needn't think you can keep me out."

Everybody looked up and stared.

"Yes, I am; so there, now!" repeated Aunt Nancy, decisively. "And the one that I find knows the most when you all get through in three weeks, why, there's some stray dollars in my purse that I don't know what to do with, and they might as well go along with your father's as anywhere else."

At this there was such excitement over by the table that nobody could hear anything, till Harper's voice finally got the high key. "And if anybody sees a bigger Fourth of July than we'll have, I'd like to know it, that's all."

"Three cheers for Christopher Columbus, and the whole lot!" cried Joe. "I wish 'twas Fourth twice a year, I do."

"We haven't got ready for one yet," said Lucy, deep in an atlas. "I'm goin' to make this a good one first."

"Three cheers for Christopher Columbus—and Lucy!" said Harper, taking the hint, and settling down to work.

"It can't be nine o'clock?" cried Joe, when Mr. Smith gave the word "To bed."

"Look at the clock, then," said their father; and all the flushed faces were turned up to the old time-piece in the corner.

"It's dreadfully nice," said Lucy, cuddling up to Aunt Nancy for a good-night kiss. "Oh, I'd love to sit up all night and study."

"Hold out to the end," said Mr. Smith; "that's what will tell." And off the three children flew to their nests, to dream of George Washington dancing a war-dance on Bunker Hill, while Pocahontas read the Declaration of Independence.

It all went very well for two days. The children got up early in the morning, and otherwise made the most of their time. Then Harper's great friend Chuckie Bronson, who had received a wonderful dog from an uncle in the country, waxed so enthusiastic over the various tricks that the little spaniel performed that Harper couldn't help catching the fever. And it came to be quite the natural thing that when the little history class gathered around the big table, one of their number was missing, and Harper's book-mark remained stationary for many a long hour. And then, unfortunately for poor Lucy, who eagerly grasped every second from play-time to spend among the text-books and atlases, which by this time had become exceedingly fascinating, for her came one evening the final hour of study, and the last hope disappeared of her ever winning the coveted "First Prize." Hateful little red spots blossomed all over Lucy's face, as if by magic, so suddenly that no one noticed, until Joe, glancing up to find a word in the dictionary, discovered them, and nudged Aunt Nancy.

"Mercy!" said that individual, looking keenly over her spectacles at the little student—"if you haven't broken out with measles! Shut your book, child; it's dreadfully bad for the eyes. Now you mustn't read another word."

If Lucy was red as a rose before, now she was pale enough. All of the hateful little red spots seemed to run right in at the command, and hide their heads.

No more study! How could she give it up? Oh! and there were still ten days before the glorious Fourth!

With all Joe's sorrow for his little afflicted sister, with all his kindness of disposition, he couldn't help but rejoice[Pg 499] just one wee bit at being sole conqueror—just for one minute, though. The next he said,

"See here, Lucy. I'll read 'em to you—every one of the questions, you know. There, don't cry, puss. And then you can learn the answers, and say 'em over and over; and—goodness me!—why, you'll learn a heap that way."

"I can't," moaned poor Lucy, screwing her fingers into her smarting eyes. "It'll put you back; you might be studying all that while, Joe. Oh dear! dear!"

"That's very true," observed Aunt Nancy, whisking off something very bright from her cheek; "and that wouldn't be quite right, Lucy. It's all the same a good thing in you, Joe, to want to. There are some things better than prizes, or knowledge even. But I'll read to you, Lucy, and if you can have the patience to learn that way—it'll be much harder, you know—but if you can do it, why perhaps you'll come off better than you think—who knows?"

So Lucy, with her father's old silk handkerchief tied over her eyes, sat on her little stool patiently day after day, while Aunt Nancy went over as much ground as could be covered in that slow way; and on the unequal battle waged.

"Of course I don't expect any prize," said Lucy, with a very big sigh, when the eventful evening of the 3d of July arrived; "but I know a little something, and that's nice. But, oh! to think of Joe!"

"Where's Harper?" said Mr. Smith, when the little circle was formed around him.

"Here," said a doleful voice from underneath the table. "I don't know anything, an' I ain't a-comin' out."

"I shouldn't think you did," said Mr. Smith, gravely. "Ah, Harper, my boy, play is pleasant enough at the time, but I tell you it hurts afterward; that is, if it's all play."

"And now," exclaimed Aunt Nancy, bringing them back to order, when a delightful hour of questions, anecdotes, and rapid answers had fairly whirled by—"the result."

"The first prize, of course," said Mr. Smith, smiling down into the two upturned, eager faces before him, "belongs, without doubt, to Joe; but if ever a prize ought to go, as fairly earned under difficulties, there should be one for my little girl!"

He put into Joe's hand a brand-new ten-dollar bill that crinkled delightfully; and then he took hold of Lucy's little hand, and opening it, he laid within one just like it.

"You've got one too!" screamed Joe, perfectly delighted. "Oh, Lucy, do look and see!"

"Have I?" cried Lucy, poking up one corner of the old handkerchief to see. "Oh, Joe, I have, I have!"

"And here is my part of the Fourth-of-July pie," cried Aunt Nancy, rattling down on them a goodly shower of silver quarters. "There! and there! and there!"

"The Fourth of July forever!" sang Joe, jumping up on the table, and swinging his arms. "Three cheers for the Encyclopædia of Events I'll get!"

"That's no better than the Histories I'll have!" crowed Lucy, triumphantly.

"And I," said a dismal voice under the table, "shall begin now for next year. Yes, I will."

After that game of mumble-te-peg that me and Mr. Martin played, he did not come to our house for two weeks. Mr. Travers said perhaps the earth he had to gnaw while he was drawing the peg had struck to his insides and made him sick, but I knew it couldn't be that. I've drawn pegs that were drove into every kind of earth, and it never hurt me. Earth is healthy, unless it is lime; and don't you ever let anybody drive a peg into lime. If you were to swallow the least bit of lime, and then drink some water, it would burn a hole through you just as quick as anything. There was once a boy who found some lime in the closet, and thought it was sugar, and of course he didn't like the taste of it. So he drank some water to take the taste out of his mouth, and pretty soon his mother said: "I smell something burning goodness gracious! the house is on fire." But the boy he gave a dreadful scream, and said, "Ma, it's me!" and the smoke curled up out of his pockets and around his neck, and he burned up and died. I know this is true, because Tom McGinnis went to school with him, and told me about it.

Mr. Martin came to see Susan last night for the first time since we had our game; and I wish he had never come back, for he got me into an awful scrape. This was the way it happened. I was playing Indian in the yard. I had a wooden tomahawk and a wooden scalping-knife and a bownarrow. I was dressed up in father's old coat turned inside out, and had six chicken feathers in my hair. I was playing I was Green Thunder, the Delaware chief, and was hunting for pale-faces in the yard. It was just after supper, and I was having a real nice time, when Mr. Travers came, and he said, "Jimmy, what are you up to now?" So I told him I was Green Thunder, and was on the war-path. Said he, "Jimmy, I think I saw Mr. Martin on his way here. Do you think you would mind scalping him?" I said I wouldn't scalp him for nothing, for that would be cruelty; but if Mr. Travers was sure that Mr. Martin was the enemy of the red man, then Green Thunder's heart would ache for revenge, and I would scalp him with pleasure. Mr. Travers said that Mr. Martin was a notorious enemy and oppressor of the Indians, and he gave me ten cents, and said that as soon as Mr. Martin should come and be sitting comfortably on the piazza, I was to give the war-whoop and scalp him.

Well, in a few minutes Mr. Martin came, and he and Mr. Travers and Susan sat on the piazza, and talked as if they were all so pleased to see each other, which was the highestpocracy in the world. After a while Mr. Martin saw me, and said, "How silly boys are! that boy makes believe he's an Indian, and he knows he is only a little nuisance." Now this made me mad, and I thought I would give him a good scare, just to teach him not to call names if a fellow does beat him in a fair game. So I began to steal softly up the piazza steps, and to get around behind him. When I had got about six feet from him I gave a war-whoop, and jumped at him. I caught hold of his scalp-lock with one hand, and drew my wooden scalping-knife around his head with the other.

I never got such a fright in my whole life. The knife was that dull that it wouldn't have cut butter; but, true as I sit here, Mr. Martin's whole scalp came right off in my hand. I thought I had killed him, and I dropped his scalp, and said, "For mercy's sake! I didn't go to do it, and I'm awfully sorry." But he just caught up his scalp, stuffed it in his pocket, and jammed his hat on his head, and walked off, saying to Susan, "I didn't come here to be insulted by a little wretch that deserves the gallows."

Mr. Travers and Susan never said a word until he had gone, and then they laughed till the noise brought father out to ask what was the matter. When he heard what had happened, instead of laughing, he looked very angry, said that "Mr. Martin was a worthy man. My son, you may come up stairs with me."

If you've ever been a boy, you know what happened up stairs, and I needn't say any more on a very painful subject. I didn't mind it so much, for I thought Mr. Martin would die, and then I would be hung, and put in jail; but before she went to bed Susan came and whispered through the door that it was all right; that Mr. Martin was made that way, so he could be taken apart easy, and that[Pg 500] I hadn't hurt him. I shall have to stay in my room all day to-day, and eat bread and water; and what I say is that if men are made with scalps that may come off any minute if a boy just touches them, it isn't fair to blame the boy.

"Now, nurse, what is it?" cried Quillie and Fred and Will and Artie, as they rushed from the deck of their odd craft, and after a hasty brushing, and a dip into the clear spring water, they made their way to the breakfast table.

"Yes, nurse chérie," echoed gypsy Julie, "please be so good as to inform—describe— Oh, what is the word?"

"Tell, tell—that is the word, little Frenchie," said Fred.

"Thanks, monsieur," said Julie, gravely.

Quillie whispered softly to Fred that his manner was rude, whereupon Fred, with a nonsensical bow, turned to Julie.

"My sister 'informs, describes' me as rude; am I?"

"A little, I think," said Julie; but she turned eagerly to hear what nurse had to say.

"Mr. Brown says that he will bring in his first load of hay to-day, and as many as choose can go to the 'Look-out' field and help him, and afterward he will give you all a ride."

"Splendid!" "Glorious!" said the boys.

"Won't it be nice?" said Quillie to Julie.

"Charming!" replied Julie; "but why is it called the Look-out field?"

"Because there is so fine a view from it of the mountains."

"The Catskills?"

"Yes, where old Rip Van Winkle slept for twenty years."

"Did he, truly?"

"So the story goes. Every time it thunders, we think the queer old mountain men are playing nine-pins."

"Do you?" said Julie, with eyes still wider open. "I should like to see them."

"The Indians used to say that an old squaw lived on the highest peak of the Catskills, and had charge of the doors of Day and Night. She hung up the new moons in the skies, and cut up the old ones into stars."

"Oh, Quillie, would it not be lovely to seek her, and find out more about the moon and stars?"

"Pshaw!" said Quillie, with scorn. "Do you believe such nonsense, Julie?"

"I don't know," said Julie, "but I think I should like to believe it."

Then they all concluded that they wanted no more breakfast, and there was another rush; for the trunks had come, and each desired some particular treasure—a garden tool, an old hat, a sun-bonnet, a tin pail, or a fishing-rod.

Nurse was too good-natured to refuse, and so the trunks were opened, and ransacked very thoroughly, until Mr. Brown summoned them; then, like swallows at twilight, they were again all on the wing, darting hither and thither. But in one little brain was a thought like a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis.

To Julie this jaunt from the city to the country had been the realization of a dream, or as if she had walked into a page of her story-books, and found the things and people all living and true. The scent of the sweet clover, the twittering of the birds, the deep blue of the sky and the deeper blue of the mountains, the snow-white daisies and the yellow buttercups, were things she had read about in the many lonely moments she had spent while her mother was out giving lessons; but in all her little life she had no actual experience of these things; and now here they were, and in addition it was the land of romance—a place where people could sleep for twenty years, a place where queer hobgoblin people played nine-pins. That squaw Quillie had told her about was fascinating; perhaps it was true that she still was living, and oh! how she should like to see her! Perhaps if she walked all day, she might reach the top of that great blue peak, and find in some strange little wigwam that old creature who cut up the old moons into stars, and then what a wonderful tale Julie would have to tell! It would be like visiting the old woman who swept the cobwebs from the sky. There would be no harm in trying. She had often been on errands alone in the great city, where everything was so confusing. Perhaps the squaw would be pleased, and give her some wonderful talisman; or she might relate to her stories of Indian life, which she (Julie) would write down and make into a book; and then no one, not even nurse, would be angry with her for daring to do so courageous a thing.

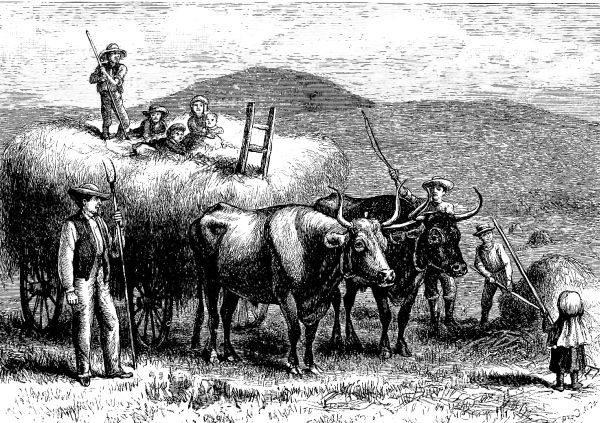

RIDING HOME FROM THE HAY FIELD.—Drawn by W. M. Cary.

RIDING HOME FROM THE HAY FIELD.—Drawn by W. M. Cary.

Who would have imagined that, as the children tossed about the heaps of fragrant hay, this wild scheme was brewing beneath the brim of a tiny straw hat wreathed with daisies? And who thought to count the merry ones on the top of the wagon-load as it turned homeward? Not nurse, who was sewing beneath a tree, and who gathered up her work and went after her charge in blissful ignorance[Pg 501] that one lamb had strayed from the fold.

With eager, hurrying steps Julie had left the meadow and sought a clump of trees; from these she emerged upon a road which seemed much travelled. It was very steep and dusty where it was not rocky, but she was not to be daunted at the outset; so on she went as rapidly as possible, for fear that, being missed, she might be over-taken, and prevented from accomplishing this great feat. At first she could hear the voices in the field beneath her, but as she hastened on all became silent but the stirring of the summer breeze in the tree-tops, and the far-away cackle of an industrious hen. The road, at first very sunny, had now wound itself beside huge crags, which made a welcome shade, and Julie saw with delight a little water-fall come tumbling down a narrow fissure, plunging into a pool below, and crossing the path. Warm and thirsty, she stopped to refresh herself and listen to the gurgling of the brook. But she must not dawdle, or night might come on, and then it would be hard to find the old squaw, who was perhaps at this moment cutting glittering stars out of the old moons. The difficulty of hanging them up did not once occur to her. Possibly the moon and the stars were not like tinsel, but she had no doubt of the squaw. She had heard that squaws made baskets: would it not be a nice thing to buy a little one for Quillie, and a great big one for nurse?—she would pick out the very prettiest. And so she scrambled on, getting very much heated and soiled, catching her clothes on the briers, getting bits of stone in her shoes, but neither frightened nor concerned about those from whom she had wandered.

Meanwhile Quillie, from her high perch on the hay, began wondering why her little companion was so silent. She supposed Julie was behind her, but, fearful of tumbling, she had been still as a mouse. She twisted about now, a little uneasily, and called Julie, but there was no response. Then Mr. Brown helped her to dismount, and still no Julie was to be seen. So she went into the house, procured a book, and sat on the piazza. Presently nurse came in.

"Where's Julie?" cried Quillie.

"Where?—was she not with you?"

"No, she was not on the hay-cart."

"Then she must be with the boys."

"No; they are in the barn."

"Then she is hiding. Go and look for her. I must get your rooms in order now." So nurse went in.

Quillie tried to read, but her thoughts were like thistle-down. Where could Julie be? She sought her all about the house; peeped into all sorts of corners. Then she went to the barn. Had the boys seen Julie? No; and they were whittling, making a boat, and couldn't be bothered.

"I wish, Fred, that you had not been so rude to Julie."

Fred looked up, surprised. "Rude! when was I rude?"

"You called her 'little Frenchy,' and imitated her."

"Did I? Oh yes, I remember something of that sort. But she isn't huffy, you know; she's a bright little chick."

Quillie thought so too, and was getting very lonely.

As the afternoon shadows lengthened, and the great conch shell was blown for the men to come in to their early supper, nurse came down to summon the children in to tidy themselves; and when she found Quillie crying in a corner, and no Julie yet to be seen, she too became uneasy. Where could the child have gone? She questioned everybody. No one had seen her. All remembered the little brown hat with its wreath of daisies. Fortunately the farm was a safe place; there was no water to fear. Perhaps she had fallen asleep somewhere. All would hunt for her after supper. And all did hunt, but no one found her.

The moon, like a silver sickle, hung in the sky; the frogs croaked; the soft sweet air puffed out the muslin curtains, and brought in the fragrance of the new-mown hay. The children, too tired to be much alarmed, went to their beds without their usual gambols. Mr. Brown hitched his weary horses, and declared his intention of remaining out all night unless he found Julie. Poor nurse was in a fever of anxiety. She reproached herself in many quite unnecessary ways. She had talked the matter over with Mrs. Brown until both were exhausted, and now she was pacing the piazza in weary restlessness.

Quillie, unable to sleep, came trotting out in her night-gown, and seeing poor nurse's sad face, went up to her, and whispered something about "God being able to take care of little Julie wherever she might be," when far away came the sound of wheels.

"Hark!" said nurse, "is that wagon coming here?"

"Yes," said Quillie, listening, "it is coming here."

STABLE TALK—Drawn by Frank Bellew, Jun.

STABLE TALK—Drawn by Frank Bellew, Jun.

Portland, Connecticut.

I have both wild and tame pets. This spring a pair of brown-headed birds built their nest in the Akebia quinata. The old birds have grown so tame that they will come up to my feet to eat crumbs. Their young are fully fledged now. The robins have a brood in the apple-tree, and now another pair of small birds have begun to build in one of our evergreens. My tame pets are a pair of jonquil canaries, Nedy and Barbra. They hatched four eggs, but all the little birds died. Now Barbra has a nest of five eggs, and yesterday one bird was hatched, and to-day another. I have a few choice varieties of roses and other plants. The roses and honeysuckles in the garden are in bloom. I am ten years old.

Altia R. A.

Geneva, New York.

We have four old canaries, and one of them, named Fanny, laid two eggs, and now there are two little birds. They keep Dick busy feeding them all the time. We give them bread and milk and boiled egg. This spring we had a pair of twin lambs, and the mother sheep did not like but one, so we had to feed the other. My brother Herbert is the one who feeds it, and it will follow him everywhere. The other day it walked into the dining-room after him. It will not come to me. We have over forty little chickens, and twelve turkeys. The turkeys are just as pretty as they can be.

Grace Eleanor.

Jersey City, New Jersey.

I am ten years old. I would like you to know how much I like Young People. I do so love to read the letters from the little girls and boys. I have a canary named Beauty, and a cat named Charlie.

Lillie C. L.

Granville, Ohio.

My papa subscribed for Young People for my birthday present. I am just getting over scarlet fever, and I look forward eagerly every week for my paper, for my playmates are afraid to come to see me, and it is the best young friend I have. I am eight years old.

May A.

Port Republic, Maryland.

I saw the letters in Young People about pets, and thought I would write about mine. I have two dogs. One is named Topsy and the other Frank. But best of all is my horse, named Ella. I am eight years old.

"Little Brother."

I live in the northwestern part of Minnesota, in the town of Detroit. I think I must be one of the most northern subscribers to Young People in the United States. This winter has been very severe. The snow staid on the ground nearly five months. We have no spring here, only a winter and a summer, with a very short autumn. Two years ago I saw a flock of Bohemian wax-wings, which are very rare in the United States. I would like to know if any other correspondents have ever seen them. They are pretty birds.

Some honeysuckles and blue, white, and yellow violets grow here in the woods.

Jay H. M.

Crugers, New York.

My aunt sends me Young People, and I like it very much. We have a squirrel round our house that is pure white, but its mother is a common red one. We think that is very odd. Our gardener calls the young one a dandy. The squirrels and rabbits in our yard are very tame, and do not mind people a bit; and a little wren builds its nest in the horse post by the stoop every year. We never frighten or hurt our wild pets.

Philip P. C.

Tullahoma, Tennessee.

I am very sorry we had to leave Frank Austin so soon, and I hope we are going to hear how he went back to his mother and sisters. I think if all Young America had as much pluck as Frank, there would be no such thing as "fail."

I caught a little rabbit a week ago, but it got away before I had made a cage for it. I have a turtle that weighs about ten pounds. But my best pet is a large dog named Andy. He is a good jumper. He can jump a very high fence.

My father has been a subscriber to Harper's Magazine ever since 1859. I think I shall take Young People as long—and longer too. My brothers take Harper's Weekly. The illustrations are so pretty! My brother Abe, who is six years old, says he is going to be a "picture man," like Mr. Nast, when he grows up.

Have any of the correspondents a tame crow? I would like to know how to pet one.

"Lone Star."

West Chester, Pennsylvania.

My brother has a young pet crow. When it is hungry it "caws" till we go out and feed it. The other day it ate three mice and a mole. It can not fly yet. I have a dear little kitty, and if it goes toward the crow, the bird will open its mouth and hop away sideways. I like to make Wiggles and Misfits very much.

Anna M. J.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I caught a dragon-fly the other day. It was three inches long, and its wings spread five inches. Its head was transparent. I have a cat named Lion. My brother takes Young People. I like to read the letters in the Post-office Box.

Care G. De M.

Milton, Vermont.

The last of April, when I went after May-flowers, I brought home some frogs' eggs in my basket. They looked like hemp seed in lemon jelly. In about a week each egg separated from the main part in a little ball. It took two weeks for the pollywogs to hatch, but when they did, it was very comical to see them swimming about. If we scared them, they would run to their balls, or homes, as we called them. I put them in the brook, and afterward when I went to look for them, I could not find them. I suppose they had developed into little frogs, and hopped away. I brought a toad home last night, and put it in the garden. It dug into the ground until it was nearly buried, and this morning I could not find it. Perhaps it got homesick—if toads ever do.

Alice C. H.

Smithfield, North Carolina.

I live one mile from a little village on the east bank of the Neuse. I have three cats, but they have no pretty tricks. I have a goat too. Her name is Philadelphia, but I call her Phila. I have a corn patch in mother's garden, and every two weeks I cut it and give it to my goat to eat. I began to study French last winter, and I finished the introductory course last night. I am ten years old.

Mattie P.

New York City.

I thought perhaps the boys and girls would like to hear about my Polly. It is just beginning to talk. Its only bad habit is that it will learn slang words. The other day a lady came to see us, and Polly cried out, "Bully for you, old fellow, come in!"

We use Young People for a reader in our school.

N. D.

Pleasant Hill, Missouri.

Two little birds have built their nest in a tree in front of our porch. It sounds so much sweeter to hear them sing out of a cage than in one, especially when they are wild birds. When the raspberries get ripe, our missionary society will have a lawn party in our yard, because it is very large. I am eleven years old.

Grace C.

Baltimore, Maryland.

I have a little bird. It is a beautiful singer and a great pet. It is a very funny little fellow. It used to escape from its cage so often that we had to tie the door. We call it Dick. The other day mamma had given Dick a bath, and tied the cage door securely, as she thought. She left it alone in a room with the windows all open, and about an hour afterward she went to put seed in, and the cage was empty, and Dick nowhere to be seen. She hunted about a long while, until at last she found him sitting on the round of a chair. She had only to put the cage down, and Dick hopped in.

Fannie S. M.

Auburn, California.

I have a pet cat named Dido, and our neighbor has a cat named Jacko. Dido and Jacko are great friends, and play together a great deal. Mamma is Dido's "meat man," and one night when she was taking Dido to feed him, Jacko began to cry, as though he did not want to be left. Then Dido ran back and put his nose up to Jacko's, and it looked as if they were kissing each other good-night. Then Dido turned and followed mamma.

Russia L.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I am in the Soldiers' Orphan Institute, and I like to read Young People very much. My Sunday-school teacher made each boy in her class a present of it. We are sorry that the story "Across the Ocean" is ended. It was such an interesting story that we want some more of it.

Charles V. F.

Harmony, New Jersey.

I am a little girl nine years old. We moved here this spring from La Fayette. My papa is a Methodist minister, so we have to move once in a while. I have a brother and sister. We have a beautiful Maltese cat, and twelve little chickens. We live three miles from the Delaware River. My brother takes Young People, and we all like it very much.

Annie Jean H.

Parkville, Long Island.

I have a pet hen, but she does not lay any eggs. She is a very cross hen, and she nips my fingers when I feed her. I had a little goat, but it died. My papa is going to buy me another. We have a little dog-cart, and a doll's house, and we play croquet, and swing in a swing made of chains.

Charlie S. R.

Xenia, Ohio.

I had Young People for a Christmas present, and I like it ever so much. It comes every Wednesday, and I am almost always the first boy at the book-store to get it. I liked the story of Frank Austin very much. He was a very brave boy.

The only pet I have is my little sister, and I pity the fellow who has not so nice a pet. She is the best one in the world. One day at the dinner table, while she was eating a piece of pie, she found a plum seed in it. All of a sudden she exclaimed, "I found a pie seed!" and she rushed out and planted it, thinking it would grow to be a tree with pies on it.

Roscoe E. E.

North Newfield, Maine.

My little cousin sends me Young People. I had a dear little kitty, but it died. Its name was Rose. Do you think it is a pretty name? I am seven years old.

Teenie J. B.

Princeton, Arkansas.

Brother Ben and I take Young People, and we enjoy it very much. It is a splendid paper for little folks, and I find that older people like to read it too. I am eleven years old, and I study music, drawing, and other things. Ben is thirteen, and he studies algebra, geometry, and Latin. I have a beautiful pet dog named Prince. A showman gave him to me. He will not let strangers come in the yard when he is loose. He is black, and very large.

Annie S. D.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.