Title: Harper's Young People, July 6, 1880

Author: Various

Release date: June 3, 2009 [eBook #29026]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire

| Vol. I.—No. 36. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | Price Four Cents. |

| Tuesday, July 6, 1880. | Copyright, 1880, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

"Hello, Foster, what's that you're doing?—shooting with a bow and arrows?"

"Yes, Stuart made 'em for me. Come in and try 'em."

Harry came into the yard, where Foster was shooting at a collar box placed on a grassy bank, and made a few unsuccessful shots at twenty yards, when Foster took the bow, and hit the box frequently, to Harry's wonder and envy.

"Stuart made 'em for me, and taught me how to handle 'em. He has a bow taller than himself, over six feet long; and up in the mountains he killed a deer a week ago—killed a deer with an arrow."

"Do arrows go hard enough to kill? Say, Foster, will Stuart make a bow for me? Won't you ask him?"

"We've got a better thing than that. Stuart wants us to get up an archery club, and he will show us how to make our own bows and arrows, just as the Indians do. Henry, Fred, Will, and Ned will join, I know, and then we will have six—just enough to go off hunting on Saturdays, and have a jolly time. And we'll have a name for the club, and make a regular camp somewhere near the Glen, and have our dinners there, and our meetings, just as Robin Hood and his men did in England. How's that, Harry?"

"Best thing out, Foster. But how are we to make our bows, and what shall we make them of?"

"Oh, Stuart has told me all about it. You must pick out the straightest, cleanest sassafras pole in the hen-house, and get Preston to saw it up into sticks one inch square and five and a quarter feet long. Then bring them over here, and Stuart will show you how to make a bow. Stuart will have a lot of pine and spruce sawed up for arrows, and you must get all the goose and turkey feathers you can, and bring them over too, and he will tell us about arrow-making. Now go and tell the rest of the boys, and get your sassafras to Preston's as soon as you can. Perhaps we can get ready to go out Saturday."

After school the next day six eager boys stood around Stuart as he took a sassafras stick, and showed them how to make a hunting bow, talking as he worked.

"Now look close, youngsters. First plane one side of the stick straight and smooth. This is to be the 'back' of the bow, and mustn't be touched again. Next mark the middle of the stick, and lay off four and a half inches to one side for a handle. Then turn the stick on its back, and plane away the 'belly' of the bow, tapering it truly from handle to 'tip.' Do the same to the sides, leaving each tip about three-eighths of an inch square. Now take a file or a spokeshave, and round off the 'sides' and 'belly' carefully, taking care not to touch the 'back' of the bow. There, the bow is in good shape, but it may not bend truly; so file a notch with a small round file in each tip half an inch from each extremity, running the groove straight across the 'back,' and slanting it across the sides away from the tips toward the middle or handle of the bow. Make a strong string of slack-twisted shoe-maker's thread, with a loop in each end, so that when the string is put on the bow by slipping the loops into the nocks, it will bend the bow so much that the middle of the string is five inches from the handle. If the bow when thus bent is too stiff in any spot, file it a little there till it bends right; and when it finally bends truly from tip to tip, put on a piece of plush for a handle, and smooth and polish your bow ready for exhibition. There, Harry, that is your bow. Now one of you may go to work at another stick, while I go and feather some arrows."

At it Henry went, eager and enthusiastic; but it was a bothersome job for young and inexperienced hands. The stick would slip, and the plane would stick, in spite of him, and his face grew very red and his eyes very bright. With Stuart's aid, however, he finally completed a very fair bow before dark, and when he had actually shot an arrow from it, his worry all vanished, and he felt very proud of his new weapon.

The following afternoon they all came together, and more bows were made. Under Stuart's direction arrow shafts were rounded and smoothed, the vanes were cut from the quills, and several fair arrows completed before separating for their homes, where all, even the staid old grandpas and grandmas, were infected by the enthusiasm of the boy archers, and Indian stories were told by the kitchen fire.

By Friday night all the six were armed with sassafras bows, and nicely feathered spruce arrows, with pewter heads, blunt, that they might not stick into and be lost in the trees. Their quivers were of pasteboard rolled in glue, upon a tapering form, and their arm-guards of hard thick leather, securely fastened to their left fore-arms by small straps and buckles. And when, early Saturday morning, they came together at Foster's house, never was a more gallant squad of young archers seen. Stumps, trees, late apples, and one or two wandering mice served as marks for their ready arrows while waiting for the start.

"Here, you boys! shoot them arrers t'other way. They'll spile more'n they're wuth," called out the good-natured hired man; and Foster raised grandma's ire by driving a shaft up to the feathers in a golden pumpkin she had selected for seed, and placed on the well curb to "sun."

By the time their haversacks were filled with potatoes, bread, doughnuts, meat, etc., and they had started for the Glen across lots, shooting as they went, all the family were relieved for the moment, only to worry the rest of the day lest some unlucky arrow, glancing, should hurt one of them; and mother's anxiety wasn't relieved when Stuart wickedly told her how Walter Tyrrel killed King William Rufus with a glancing arrow from his bow while hunting.

The birds and the squirrels that our boys met that day were treated to many a close hissing arrow, though not many of them suffered, because of the boys' lack of skill with the long-bow.

"Sh-h-h! boys," suddenly whispered Foster, as the little band paused for a moment in a clump of spruces; and springing noiselessly up, his bow was braced, his arrow fitted, and a stricken bird was fluttering at their feet in a few seconds. The flutterings of the fallen bird were more than equalled by those of Foster's heart, as he held the still quivering crow-blackbird which his arrow had brought from the highest twig of a tall spruce. Proud and exultant, yet tears glistened in his eyes as he silently gazed upon the soiled plumage of the bird's beautiful neck and breast, and felt its last faint gaspings as its reproachful eyes became glassy in death.

"The beautiful bird! Oh, I won't shoot another bird," he declared, with quivering lips. "How pretty it is, and how warm! I'll ask Stuart to stuff it, so that I can keep it forever."

By this time Will's hunger was too much for his archery enthusiasm, and he began to grumble.

"Say, boys, isn't it about time to get to the Glen, and make our camp? I'm getting hungry. It's hard work drawing this bow of mine, and my arms are tired."

"Yes, let's go to the Glen," said their captain, Foster; and half an hour's silent tramping in the underbrush and up the rising ground—for they were now pretty tired—brought them to the spot known as the Glen.

The Glen was a lovely place. A sparkling spring, rising at the base of a giant hemlock at the head of a long deep gully, had in the course of ages filled in the hollow, till a broad level floor was made, surrounded by close-growing hemlocks, pines, and spruces, and carpeted with fine turf and pine needles. The water from the spring, flowing in a shallow brook through the middle of this[Pg 507] floor, lost itself in the dark recesses of the gully further down. At the very top of the great hemlock by the spring was a rude eyrie, built by the boys, called the Crow's Nest, and from its swaying, breezy height they had a magnificent view of the country for miles around. Here, rocking gently and safely, seventy-five feet above the spring, they picked out their homes, the pretty white villages nestling among the forest masses of green, and the slender streams glistening among the cultivated fields and neat mowings.

Near the spring was a rude hut that Stuart and his mates had built a few years before. Taking possession of this, they took off their haversacks, hung their bows and quivers about on projecting limbs, gathered dry leaves and sticks, and soon had a fire started in a rude stone fireplace.

"Well, my merry bowmen, how do the twanging bow-string and the hissing arrow suit the greenwood?" asked Stuart, who came up as they lay picturesquely about, waiting for a bed of coals.

"Oh, it is splendid. Isn't it, boys?" answered Will, the oldest of the young archers. "Just see how pretty the bows and quivers look, hanging among the green branches. How nice this all is! But what name shall we give our club?"

"Woodland Archers," suggested Ned.

"Mohawk Foresters," added Henry. "We want our river in the name, and the Mohawks were great warriors."

"Let's call it the Mohawk Bowmen," continued Ned. "That's just the thing." And all agreed to it, and so Mohawk Bowmen was decided upon as the club name.

"Who'll be captain?" asked Stuart.

"Oh, Foster, of course," answered all at once. "He's the best shot, and ought to be."

By this time the coals were ready, so the potatoes and corn and meat were roasted, amid much fun and gay talk, and were eaten by the hungry archers. Then, after a rest, the Mohawk Bowmen ranged the woods and fields till sunset found them at home again, tired, indeed, but enthusiastic over archery and their day's sport. They agreed it was the happiest day they had ever seen, and arranged for a grand woodchuck hunt on the following Saturday.

The first sound I heard at daybreak, through the window, was the Moslem's call to prayer, from the minaret, "La Illahâ illa Allah"—"There is no other God but God"—breaking clear and solemn over the stillness of the early dawn, and waking the echoes of the empty streets. Presently I heard a footstep in the distance; as it approached nearer, it made the arches resound. I looked out, and saw a pious Mohammedan hastening to prayer. As he passed under the window I heard him muttering in a low voice, and caught some sentences of his prayer: "Ya Rahim, ya Allah" ("O God, the merciful!"). Scarcely had his footsteps died out when I heard the soft silvery sound of a bell, whose melodious music seemed to roll out like billows into space, and as the reverberations were carried away to a more distant region, a chime of bells rang out merrily; these were the matin bells calling the Christians to prayers. The streets and arches again re-echoed hurrying footsteps, which were those of the Catholic monks hastening to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. As they passed the window I could hear the clicking of their rosaries, and distinguish the words "Dominus, Dominus," muttered in a low voice.

Another sound broke the stillness: "Ya Karim, ya Allah" ("O bountiful God!"). This was a cake vender, carrying on his head a large wooden tray containing cakes and baked eggs. He uses this exclamation as an acknowledgment that God is the giver of our daily bread.

"Karim" was still sounding, when I heard a different strain, "Chai chai kirna cha-ee," which was sung in a sonorous nasal voice. This was a tea man. In one hand he carried a bright brass tea-urn of boiling water; in the other, several glasses, which he continually jingled against one another. Fastened round his waist he wore a circular tin case, containing glasses, a tea-pot, sugar, lemons, and tea-spoons. The tea man continues his walk through the streets till the day is far advanced, and he meets with a great many customers, for quite a number of Arabs consider a cup of tea a good remedy for a headache in the morning.

The passers now increased, and they exchanged salutations such as "Nihar saïd!" ("May your morning be enriched!")

There was a coffee shop opposite the window. This was the earliest opened. The waiters came out of the store carrying low stools, which they placed outside the shop along the sidewalk. Their dress was navy blue baggy trousers, which reached a little below the knee; white shirts, the sleeves of which were rolled over their elbows; crimson girdles, and white skull-caps. A couple were barefoot, and the others had red shoes on. They moved about lightly as they arranged the stools for customers.

A tall young man came toward his store, which was a grocery, and next the coffee shop; but before opening it he sat down on one of the low stools, and was at once served by one of the waiters with an "argillé," or hubble-bubble, and a cup of coffee. He wore a suit of dark green cloth, a crimson satin vest, silk girdle of many colors, and a red tarboosh. Another gentleman came up, dressed in a similar costume, only of a bluish-gray. Before seating himself he saluted the other by a graceful wave of the hand, saying, "Issalaâm alêk," or "Peace be on you."

"Ou alêk Issalaâm" ("And unto you be peace"), responded the other.

These two are Christians, as can be seen by their dress. Two Mohammedans, dressed very much like the others, but each wearing a long loose "Jubè" (which is a cloak) over his suit, and a white turban of fine Swiss muslin wound round his tarboosh, came and took seats, after having saluted the others with the same beautiful salutations. Many others in various costumes seated themselves, and conversation became general as they smoked their pipes and sipped their small cups of coffee.

The sparrows were chirping merrily in the green caper bushes which grew out of the walls of the old gray houses. From this window I had also an excellent view of the Mount of Olives, over which I now observed the rosy tint of the rising sun. I watched it, and gradually the rose deepened into a glowing hue; then the sun rose like a ball of living fire. The towering minarets and mountain-tops caught the golden rays. The magnificent blue hue of the distant mountains of Moab reflected the gorgeous gold. The rays were also reflected in the window-panes of the old gray houses, making them look like molten gold, and the dewy domed roofs like glistening silver; and as the sun rose higher, he brightened up the fine old stone houses. A majestic palm-tree, whose green branches were being waved by the soft morning breeze, glittered as the dew on them was touched by the warm rays.

My notice was now attracted to view the passers. Emerging from under an arch was a grave old turbaned Turk. He had a long white beard, and wore a suit of dark blue cloth, red silk girdle, lemon-colored pointed leather shoes, and a tarboosh wound round by a large green turban. This green turban is a sign that he is a Haj, or one who has been on a pilgrimage to Mohammed's grave at Mecca.

He moved along slowly and majestically, for in the Orient one never sees an Effendi hurrying along the[Pg 508] streets. However busy men may be, they always walk calmly and leisurely, as if quite at their ease. Behind this Effendi his slave carried his master's pipe.

Donkeys, mules, horses, and camels were passing, some of the donkeys laden with wood, others with vegetables, and driven by peasants who were dressed in white shirts reaching below the knee, their waists encircled by broad red leather belts, while on their heads they wore large striped silk turbans of bright colors. Their shoes were made of undressed camel's leather, bound round the edge with yellow leather, and fastened by a latchet made of the same. Probably this was the same kind of shoe that was worn in the days of John, when he said of our Lord, "Whose shoe's latchet I am not worthy to unloose."

The mules had small brass bells hung round their necks, which, as they moved along, rung quite merrily. They were laden with tents and canteens belonging to camp life. Probably some travellers had arrived from a trip up the country. The camels roared and bellowed, as if they did not approve coming into the city; they were laden with charcoal, which was in long black sacks.

The gentlemen, after sipping their coffee and smoking their pipes, proceeded to open their stores, and while doing so, they uttered this prayer, "Bismillah ir ruhman ir raheem" ("In the name of God, the most merciful").

Peasant women came up, carrying on their heads large brown circular baskets, made of twigs, about eight inches deep, filled with tempting fruits and salads. It was wonderful how well they balanced them, for they were walking erect, and very briskly, without holding them. Stopping under the window, they took the baskets off their heads, and placed them on the ground, sat down with their backs against the wall, and put them in front of them for sale. They looked picturesque in their long dark blue gowns, red silk girdles, wide open sleeves displaying their arms, adorned with bracelets and armlets.

Another young peasant woman came up, not only with a basket of fruit on her head, but a baby dangling in a hammock down her back. This hammock is an oblong piece of red and white striped coarse cloth, made out of camel's hair. She placed her basket alongside of the others, and took out her baby. Soon the baskets were surrounded by eager customers, who had to stoop down in order to pick out what they wanted. The baby meanwhile fell asleep, and the mother, finding it an incumbrance while serving her customers, placed it again in its hammock, on which she had been sitting, and hung it up on the door of one of the neighboring stores.

People passed to and fro, jostling each other as the passers increased; the street looked lively and gay with such a variety of costumes. Among them were several figures walking slowly along; they were enveloped in white sheets from head to foot, their faces covered with thick colored veils, so that it is impossible to distinguish the person. They were Oriental city women. An Oriental city woman never hurries through the streets, as that would be considered an impropriety.

Oh! the beautiful bright summer,

Ev'rywhere wild flowers springing;

Honeysuckles to the roses

All day long sweet kisses flinging.

Brooklets sparkling through the meadows,

Humming-birds their glad way winging

With gold-brown bees and butterflies

Where lily-bells are ringing,

Ringing, ringing—

Where lily-bells are ringing.

Sunbeams on the greensward dancing,

Gentle breezes perfume bringing;

In the cedar-tree five birdies

To their wee nest closely clinging;

Peeping over at the children,

(Five of them too) laughing, singing.

In nest most wonderful to see,

Between the branches swinging,

Swinging, swinging—

Between the branches swinging.

The wave receded as suddenly as it came. The boys sprang up in a terrible fright, and indeed there are few men who in their place would not have been frightened. The shock of the cold water was enough to startle the strongest nerves, and as the boys rushed to the door of the tent, in a blind race for life, they fully believed that their last hour had come. Before they could get out of the tent, a second wave swept up and rose above their knees. With wild cries of terror, the two younger boys caught hold of Tom, and losing their footing, dragged him down. Harry caught at Tom impulsively, with a vague idea of saving him from drowning, but the only result of his effort was that he went down with the rest. Fortunately the wave receded before the boys had time to drown, and left them struggling in a heap on the wet sand. There was no return of the water, and in a few moments the boys were outside of the tent, and on the top of the bluff above the river.

"It must have been a tidal wave," said Jim. "Oh, I'd give anything if I was home! The water will come up again, and we'll all be drowned!"

"It was the swell of a steamboat," said Tom. "There's the boat now, just going around that point."

"You're right," said Harry. "It was nothing but the swell of the night boat. What precious fools we were not to think of it before! To-morrow night we'll pitch the tent about a thousand feet above the water."

"Then there'll be a water-spout or something," said Jim. "We're bound to get wet whatever we do. We only started yesterday, and here we've been wet through three times."

TRYING TO KEEP WARM.

TRYING TO KEEP WARM.

"And Harry has been wet four times, counting the time he jumped into the Harlem for me," added Joe.

"It won't do to stand here and talk about it," said Tom. "We've got to have a fire, or we'll freeze. Look at the way Joe's teeth are chattering. The blankets and clothes are all wet, and the sooner we dry them, the better."

There happened to be a dead tree near by, and it was soon converted into fire-wood. The boys built a roaring fire on a large flat rock, and after it had burned for a little while, they pushed it about six feet from the place where they had started it, and after piling fresh fuel on it, lay down on the hot rock with their feet to the flames. The fire had heated the rock so that they could hardly bear to touch it; but the heat dried their wet clothes rapidly, and kept them from taking severe colds. Meanwhile their blankets had been spread out near the fire, and in half an hour were very nearly dry, and pretty severely scorched. Two large logs were then rolled on the fire, and when they were in a blaze the boys wrapped themselves in their blankets, and lying as near to the fire as they could without actually burning, resumed their interrupted sleep. They found the rock rather a hard bed, and it offered no temptation to laziness; so it happened that they were all broad awake at half past four; and though somewhat stiff from lying on a rocky bed, were none the worse for their night's adventure.

"There's one thing I'm going to do this very day," said Harry, as they were dressing themselves after their morning swim. "I'm going to write to the Department to send us a big rubber bag that we can put our spare clothes in and keep them dry. There's no fun in being wet and having nothing dry to put on."

"If we have the bag sent to Albany, it will get there by the time we do," said Tom. "You write the letter while we are getting breakfast."

So Harry wrote to the Department as follows;

"Dear Uncle John,—We've been wet through with a steamboat once, and the tide wet us the first night, and we got rained on, and I jumped in to get Joe out, and we've had a gorgeous time. Please send us a big water-proof bag to put our spare clothes in, so that we can have something dry. Please send it to Albany, and we will stop there at the Post-office for it. Please send it right away. You said the Department furnished everything. We've been dry twice since we started, but it didn't last long. There never was such fun. All the boys send their love to you. Please don't forget the bag. From your affectionate nephew,

"Harry."

[Pg 510]

"This was the morning that you were going to sleep till eight o'clock without waking up, Harry," said Tom, as they were eating their breakfast.

"There's nothing that will wake a fellow up so quick as the Hudson River rolling in on him. I hadn't expected to wake up in that way," answered Harry.

"So far we have done nothing but find out how stupid we are," said Tom. "Seems to me we must have found it pretty near all out by this time. There can't be many more stupid things that we haven't done."

"There won't any accident happen to-night," replied Harry; "for I'll make sure that the tent is pitched so far from the water that we can't be wet again. I wonder if every fellow learns to camp out by getting into scrapes as we do. It is very certain that we won't forget what we learn on this cruise."

"I'm beginning to get tired of ham," exclaimed Joe. "We've been eating ham ever since we started. Let's get some eggs to-day."

"And some raspberries," suggested Jim. "It's the season for them."

"And let's catch some fish," said Tom.

"That's what we'll do," said Harry. "We'll sail till eleven o'clock, and then we'll go fishing, and catch our dinner."

This suggestion pleased everybody; and when, at about six o'clock, they set sail, with a nice breeze from the south, everybody kept a look-out for a good fishing ground, and wondered why they had not thought of fishing before.

It had been arranged for weeks beforehand, and the whole family were delighted with the novelty of the proposition. Mrs. Rovering suggested it on the evening of Decoration-day, as she and Mr. Rovering and Edward and Edgar sat at the supper table, with patriotic appetites after their long tramp to and from the soldiers' graves.

"I think," Mrs. Rovering began, as she buttered a biscuit for Edgar—"I think we had better commemorate the Fourth in a manner that will not so weary us as to-day has done."

The good lady always made use of those words which it seemed she must have gone to the dictionary and picked out before she began to speak.

"Oh, pa, how many crackers will you give us this year?" burst out Edward.

Mr. Rovering was in the fire-works business, which fact had always been a source of the greatest satisfaction to his sons, and an awful trial to his wife, who every night expected to see him brought home in a scattered condition on a stretcher.

"What do you say to our not participating in the annual picnic, as it always rains, and the silver-plated ware's mislaid, the ants get into the sugar, and the boys into the pond?—what do you say to foregoing the enjoyment of these sylvan delights, and spending the day in town? We should thus have an opportunity of observing to how great an extent explosives are used here, and you could then gauge your manufacture of the articles accordingly. Aha! I have it!" added the inventive lady, after a moment's reflection. "We'll take the line of cars running entirely around the city, and so we'll be sure of viewing all sides of the question."

"The very thing!" exclaimed her husband.

In due course the famous national holiday arrived, and at about nine o'clock in the morning the family sallied forth on their memorable expedition. The two Eds went first, hurling torpedoes as if they were trade-marks, and now and then touching off a cracker, after having assured themselves that there was no policeman near. Then came the father and mother, arm in arm, under a great cotton umbrella, which Mrs. Rovering always insisted should be carried during their excursions, for fear rain might come on and spoil the silk one.

On reaching the corner where they were to take the car, a discussion arose as to which direction they should go.

"It doesn't make a particle of difference, so long as we get off," affirmed Mr. Rovering.

"Well, then," rejoined the originator of the expedition, "let's take whichever car comes first." And this decision would certainly have finally disposed of the matter if at that instant Edward had not shouted, "Oh, ma, here's a car coming up!" and Edgar, "Oh, pa, here's a car coming down!" and if, moreover, these two cars had not arrived at that identical corner at one and the same moment.

They both stopped, and Mr. Rovering cried, "Dear me, Dolly, which shall we take?—which shall we take?" while Edward hopped up and down on the step of one, and Edgar practiced jumping on and off the platform of the other.

"Take the one that isn't a 'bobtail,'" returned Mrs. Rovering, composedly.

"But they're both 'bobtails!'" exclaimed her poor husband, in an agony of apprehension lest the cars should start off, and cause his sons to fall on their pocketfuls of torpedoes.

Finally Mrs. Rovering said, quietly, "We shall ride in the empty one," and this proving to be the up-bound conveyance, they got in and were off.

"Now, Robert," Mrs. Rovering began, as soon as they had recovered from the shock of starting, which had sent them all down on the seat like a row of bricks, "don't make a mistake in putting our fares in the box. Let me see, five, five—yes, both the boys are over five. Have you got it right?"

But sad to relate, Mr. Rovering had not got it right, for, owing to his wife's constant repetition of the word five, he had become so confused as to drop twenty-five cents into the box, thinking there were five in the party.

"Make the driver extricate it for us," suggested Mrs. Rovering; but that individual promptly replied that he couldn't do it, and coolly proceeded to let the money down into the safe before their very eyes. But upon this his passengers raised such an outcry of indignation that the knight of the brake was forced to open the door again, and pacify them by saying they might take the fare from the next passenger. This appeared to be such a brilliant idea that Mrs. Rovering was almost inclined to envy the driver's genius.

These cars, although "bobtails," were drawn by two horses, and therefore went along at quite a respectable rate, but this did not prevent evil-minded youth from hanging on behind in all the blissful enjoyment of a free ride, and the efforts of the driver to dislodge these highway boys amused the two Eds not a little. One of his stratagems was to suddenly brake up the car as though he were going to stop and personally chastise the offenders, while another was to ring the bell and pretend one of his passengers was about to alight.

But on this occasion there were two boys who persisted in sticking on in spite of everything, and at last they so exasperated the poor driver that he threw down his reins, and rushed around to the rear platform with his whip raised.

Now it so happened that the two Eds had been long waiting for this opportunity, and as the man cut the air with his lash—and the air only, for the young rascals were already half a block away—Edward and Edgar simultaneously threw down six torpedoes apiece on the front platform, the effects of which were to send the horses off at a gallop, with the lines about their feet, and the driver tearing after them in vain.

"Whoa!" shouted Mr. Rovering and the boys.

"Which—where—what shall we do?" groaned Mrs.[Pg 511] Rovering, sinking back on the seat, and covering her face with her hands.

"Stop 'em, somebody. And oh, boys, why did you start 'em?" and Mr. Rovering remained standing motionless on the platform, casting longing looks at the reins trailing in the street.

"Remember," exclaimed Mrs. Rovering, "we're on the continuous line, and so we'll keep on going round and round, and never stop! Oh, why did you ever force me to set out upon this unhappy expedition?"

At this Mr. Rovering grew almost beside himself with despair; and determined on doing something, he seized the two Eds, and extracting from their pockets every torpedo he could find, flung the latter, in the heat of his passion, out of the window, which naturally resulted in a report much louder than the first one, and thus materially quickened the pace of the poor, bewildered animals.

And now a new danger arose. What if they should catch up to the car ahead?

But, luckily for all concerned, the stables of the company were not far off, and when the horses reached the car-house they slowed up, and the Roverings were rescued.

"But why didn't you put on the brake?" asked the superintendent.

Sure enough, why hadn't they?

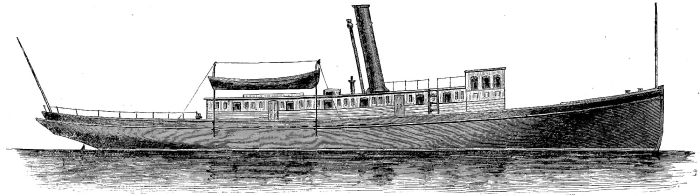

Most of you boys know enough about boats to have built your sloop and schooner yacht, and perhaps a canoe; now why not go a little farther, and build a steam-yacht? Don't worry about your engine, boiler, and propeller; these can be bought complete at a low figure—an engine that will reverse, stop, and send your boat ahead at the rate of two miles an hour.

After taking a good look at the plates, and having made up your mind that you are equal to the task, go and see your friend the carpenter, and tell him you want a piece of white pine, free of knots, grain running lengthwise, well seasoned, thirty inches long, seven wide, and six deep. I speak of white pine, for the reason that it is easy to get, inexpensive, and cuts easily. Plane the four sides smooth; mark a centre line, AB, on both top and bottom.

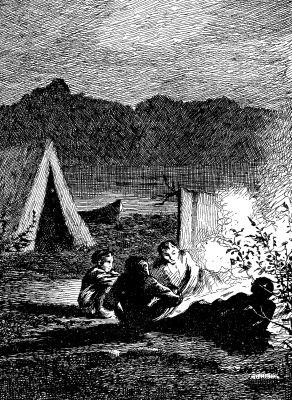

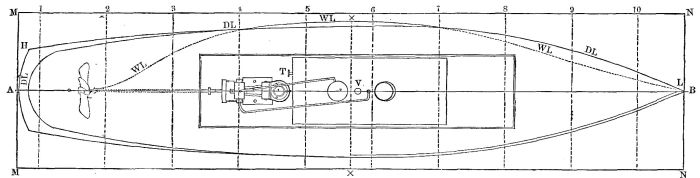

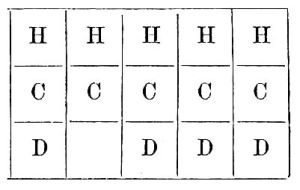

PLATE I.

PLATE I.

PLATE II.

PLATE II.

The centre of your block must now be marked at right angles to the line AB on top and bottom; carry this line down the sides as well. This is the line marked X in Plates I. and II. Now for the first cutting of the block—the sheer line SH on Plate I. The dotted lines marked from 1 to 10 must be drawn, beginning at 1, just one inch from the left-hand end of block, No. 2 three inches from this, and so on, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10; the last number will be just two inches from the right-hand end. These are to be marked on top and on both sides. These lines are very important, as the shape of your boat depends upon them. With a pair of compasses take distances from the line AB, Plate I., at numbers 1 to 10 respectively, to the line marked SH, and join the points with a straight-edge. This is your sheer. Work from the bow to about the centre of the block, and then from the stern; if you attempt to cut from end to end, you will certainly split off too much. Finish this sheer line with a spokeshave. The lines having been cut off the top of the block, draw them again on your new surface, as well as the line X and the centre line AB.

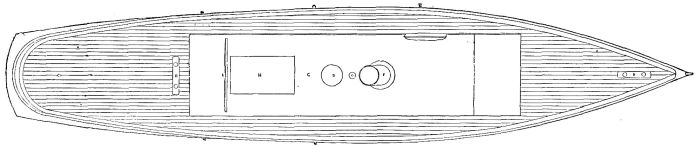

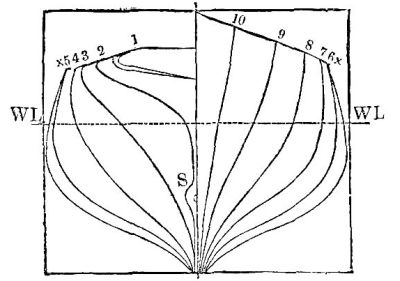

PLATE III.

PLATE III.

PLATE IV.

PLATE IV.

Now for Plate II. This gives the shape on deck. Using your compasses again, take the distances from the line AB on the subdivisions from stem to stern, and join with a curved rule, making the line HL. Before cutting away the sides of the block, look at Plate IV.; this gives the shape of the boat amidships. At the line X on deck it is but six inches wide, but it gradually widens to seven inches. Cut away with a draw-knife from 6 on the line MN to L, Plate II., and from 5 on MN to H, striking the line HL at 8 in the former, and at 3 in the latter case. The other side must be cut in the same way. The block had better be put in a bench vise to do this. You have now your boat in the rough. With a spokeshave round up the sides of the hull to HL. Turn your boat over, and cut with a saw three and three-quarter inches from the left-hand end, to a depth of three inches, and split off with a chisel.

Plate IV. gives the lines of the hull from the centre, to bow and stern. Make careful and separate tracings of the curves marked from 1 to 10 and X, paste on thin pieces of wood, cut them out with a knife or jig-saw, and number them. Cut away the sides of the hull, testing with your patterns at the respective subdivisions, and finish with a spokeshave. Be careful near the stern-post of the swell where the shaft comes through. In cutting the bow take the pattern of the curve BK, Plate I., and shape accordingly. Now you may begin to dig out the hull. Fit your boat firmly to a table, or put it in a bench vise; but be careful not to mar the sides. Allow half an inch inside of the deck line for the thickness of the sides. Don't go too deep, but between the numbers 7 and 4 get the right depth or bed for your engine and boiler; place a straight-edge across the boat at these points, and get just the depth; the width necessary you will see in Plate V.

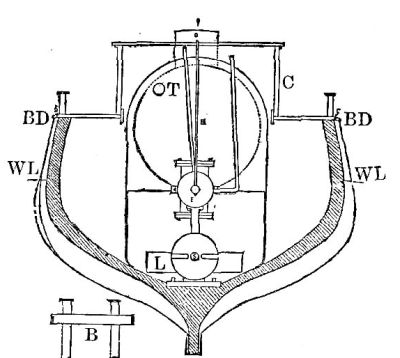

PLATE V.

PLATE V.

Plate II. For the deck use white pine one-eighth of an inch thick, straight-grained, and free from knots. Follow the line DL in cutting the deck. Allow the deck to project one-eighth of an inch all around; this will serve as a beading around the hull. Section of vessel Plate V. shows this at BD.

Plate III. shows deck finished, planking, top of cabin, bitts, etc. Mark the planking with an awl and straight-edge—not too deep, however, or you will split your deck. The double lines in the opening of the deck, Plate II., represent a coping to fit the cabin on, and at the same time to strengthen it. Make it of pine one-sixteenth of an inch thick, and fasten with good-sized pins having points clipped off diagonally by nippers or scissors: a better nail you will not want; use these wherever it is necessary.

The motive power consists of a single oscillating cylinder, half-inch bore, one-inch stroke; copper boiler, with lamp, shaft, and propeller; which will cost you ten dollars. A double oscillating engine costs fifteen dollars. The engine is controlled from the top of the cabin. The lever, if pressed to the right, will start the engine ahead; if left vertical, will stop, and to the left, will reverse it. What more can you want than that? The lamp holds just so much alcohol, and when that is burned out, the water in the boiler is used too. Never refill the lamp without doing the same to the boiler. The boiler is to be filled through the safety-valve, and provided with three steam-taps; these will show the height of water in the boiler. The coupling or connection between the shaft and engine is made so that you may take engine and boiler out, and use them for anything else.

There are three things we've forgotten, the stem, stern-post, and keel. Use the pattern you made for your bow, and cut out one-eighth inch stuff for your cut-water, or stem; the dotted lines at BK, Plate I., will show the shape; fasten on with cut pins. The stern-post, with the exception of the swell for the shaft, should be about the same thickness, and fitted in as shown in Plate I. The keel should be of lead, tapering from half an inch in the centre to one-eighth at the bow and stern: cut a small hole at Z, and let the rudder-post rest in it. Now fasten in your engine; two screws through the bed-plate will do it. Try the boat in water; if she is down by the stern, tack a piece of sheet lead in the bow inside. Nail your deck in with cut pins. Use one-eighth inch strips one-half inch high for the gunwale as far as the rounding of the stern; this must be cut out of a solid piece. Finish the gunwale with a top piece of Spanish cedar lapping over on either side of it.

Your cabin may be made of Spanish cedar one and a[Pg 512] half inches high, one-eighth thick; make this wide enough to fit outside of the coping; your sheer pattern will give the necessary curve to fit it to the deck. The pilot-house is made separate, two inches high. Before putting the cabin together, cut all openings, windows, etc., and mark with an awl the panellings and plank lines. The doors are simply marked in, not cut out.

Leave the front windows in the pilot-house unglazed, so as to serve as ventilators for the lamp. The top of the cabin overlaps the sides one-eighth of an inch all around. Cut a hatch in the cabin roof abaft the steam-drum; this is intended to oil the engine through, and try the steam-taps, without taking off the whole of the cabin. The cabin is kept in place by the funnel, which slips off just above the roof. The slit in the cabin top just back of the hatch is where your engine lever comes through. The bitts, B, fore and aft, are made of Spanish cedar, running through the deck to the hull. Your tiller may be made of steel wire running through the head of the rudder-post, which is made of iron wire; the man who makes your engine will do this for you.

MODEL OF A STEAM-YACHT.

MODEL OF A STEAM-YACHT.

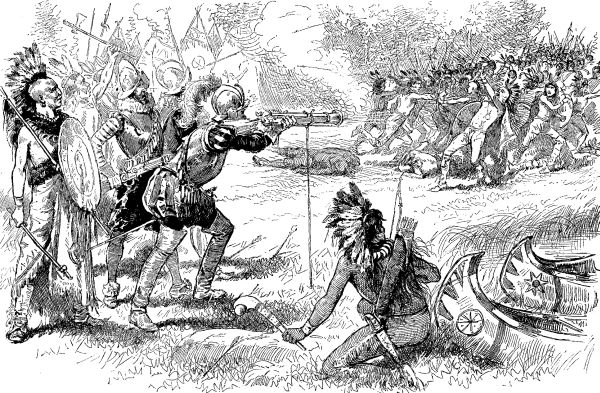

It was a long while ago, in 1535, that Jacques Cartier, of France, discovered the St. Lawrence River. He sailed up the mighty stream to the Indian village of Hochelaga—a cluster of wigwams at the foot of a hill which he named Mount Royal, but which time has changed to Montreal. Seventy-four years rolled away before any other white man visited the spot. In 1609, Samuel Champlain, an officer in the French navy, sailed up the great river. He was a brave adventurer, who was ever taking long looks ahead, and dreaming of what might be in the future—how the unexplored wilderness of America might become a New France. He had built houses at Quebec, and was on his way to discover what might be beyond.

He treated the Indians kindly, gave them presents, and made them his friends. There were many tribes, but all the Indians east of the Mississippi, and between Lake Superior and the Ohio, were divided into two great families, the Algonquins and the Iroquois. The Indians along the St. Lawrence, the Ottawa, and Lake Huron were Algonquins. The Iroquois lived in New York. They were the Mohawks, Onondagas, Oneidas, Senecas, and Cayugas. They called themselves the Five Nations. They had corn fields, and lived in towns. Their language was different from that of the Algonquins, with whom they were ever at war.

The wild flowers were in bloom in June, 1609, when Samuel Champlain sailed up the St. Lawrence to join a war party against the Iroquois. He had resolved to make the Algonquins his allies, and through them, and with the aid of the Jesuit priests, he would lay the foundations of the empire of New France.

The war party sailed up the Richelieu, or the St. John, carried their canoes past the rapids, launched them once more, and came out into the lake which bears the name of the intrepid explorer. Two Frenchmen accompanied Champlain, and there were twenty-four canoes, carrying sixty warriors, who had put on their feathers, and filled their quivers with arrows.

The woods were full of game, and the lake was swarming with fish, so that there was no lack of provisions. At daybreak they hauled their canoes up on the beach, and secreted themselves, so that no Iroquois might discern them; but when the sun went down they launched their canoes, and stole on in silence over the peaceful waters.

It was ten o'clock in the evening. They were near Crown Point, when they heard the dip of other paddles, and beheld a fleet of Iroquois canoes moving northward. A whoop wilder than the howling of a pack of wolves rent the air, and the Iroquois pulled for the shore to prepare for battle. They hacked down trees with their stone hatchets, and built a barricade.

Both parties danced, sang, howled, and yelled through the night, boasting of what they would do.

"We will fight you at daybreak," came from one side.

"You are cowards, and don't dare to fight," was the answer.

The morning sunlight streamed up the eastern sky, revealing the outline of the Green Mountains, and driving the darkness from the wilderness. The air was calm and peaceful as the Algonquins and Iroquois ranged themselves for battle. Many times had they met, and the great world had been no better—nor perhaps any worse—for their fighting; but this was to be a momentous conflict, affecting the welfare of the people of America through all succeeding ages.

Champlain put on a steel breastplate, and an iron casque to protect his head, with a plume waving from the burnished metal, buckled on his sword, loaded his arquebuse, or gun with a bell-shaped muzzle, putting in four balls.[Pg 514] The other two Frenchmen put on their breastplates and loaded their guns, but all three kept themselves concealed from the Iroquois.

The Iroquois had shields of hide stretched on hoop for defensive armor. Like the Algonquins, they had bows, arrows, and tomahawks.

The Algonquins were only sixty-four, while the Iroquois were more than two hundred. In splendid order, which was the admiration of Champlain, the Iroquois advanced to wipe out the Algonquins at a blow.

The Algonquins opened their ranks, and the Iroquois beheld Champlain—a being in human form, with the sunlight gleaming from his breast. They were transfixed with astonishment at the apparition. They see him pointing something at them. There is a lightning flash—a cloud—a roar. A chief falls dead, and one of the warriors is wounded.

The Iroquois are astounded. For a moment the air is filled with their arrows. Another lightning flash, a third, and they flee in terror, running swifter than the deer, to escape from beings which fight with lightning flashes and hurl invisible thunder-bolts! They were shots which are still echoing down the ages.

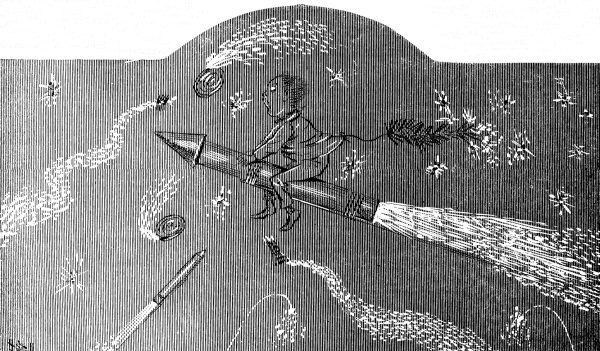

A BATTLE THAT LASTED BUT A MINUTE.

A BATTLE THAT LASTED BUT A MINUTE.

The battle has lasted a minute, but the Iroquois never will forget it. More intense their hate of the Algonquins; and it is the beginning of their implacable enmity to the French: an enmity which is to increase as time goes on, and which will make them the allies of the English through the great struggle which is to take place between France and England—between two races, two languages, two religions, and two civilizations—for supremacy upon this continent.

Seven years passed. Champlain had been back to France, and had returned. He was still thinking of the great empire France would one day control in the Western World. He made his way with a dozen Frenchmen up the Ottawa, past Lake Nippising, to Lake Huron, then turned south to Lake Ontario, sailed along the eastern shore with a great war party of Hurons, to attack their old enemies—the Senecas, tribe of the Iroquois.

It was October. The woods were bright with crimson and magenta hues. The Iroquois had planted corn and pumpkins, and were gathering the harvest when the Hurons burst upon them. They fled to their fortified town on the shore of Lake Canandaigua. It was inclosed by trunks of trees thirty feet high set in the ground. There was a gallery on which they could stand and fire or throw stones upon their assailants.

The Iroquois were the terror of every tribe east of the Mississippi. If Champlain could but conquer them, he would make the power of France felt to the Gulf of Mexico.

All night long the Hurons worked, building a tower of timber upon which the Frenchmen could stand, and pick off with their guns those inside the walls.

Two hundred warriors, with shouts and yells, amid a volley of arrows, drag the tower into position. The Iroquois swarm upon the walls, and the fight begins—the Frenchmen firing from the top of the tower, the Iroquois sending back arrows.

The Hurons light torches, and run up to the palisade with armfuls of dry sticks, and set them on fire; but the Iroquois run with calabashes of water, mount the gallery, and extinguish the flames. Each warrior yells at the top of his voice. They are crazed with excitement. For every whoop of the Hurons, the Iroquois give an angry yell of defiance. Arrows and stones fly. The Iroquois drop one by one before the unseen thunder-bolts from the men in the tower, but seventeen warriors go down before the arrows of the Iroquois. An arrow wounds Champlain in one knee, another pierces his leg. For three hours the fight goes on, when the Hurons, crest-fallen and disheartened, retreat to their camp. They linger five days, and then retire to their canoes, carrying Champlain on a litter all the way to Lake Ontario. The Iroquois steal upon them in their retreat, letting fly volleys of arrows, and yelling like hyenas over the defeat of the Hurons. They have discovered that the white men with their guns, after all, are not invincible.

Humpty Dumpty looked very sober one July morning, as he sat on his mother's door-step, his usually good-natured face screwed into a dozen wrinkles, and his button-hole of a mouth drawn down at the corners in the most dismal manner imaginable.

What could be the matter with the merry lad? For he was known far and wide for his fun and jollity.

So thought Mother Goose as she came up the village street.

"Why, Humpty Dumpty, what has happened to you? have you had another fall?" asked Mother Goose.

"No, Mother Goose, it is not a fall this time, but something worse, for I haven't a penny in the world, nor likely to have, and to-morrow is the Fourth of July, when all the boys and girls will have pistols, gunpowder, and fire-works, while I shall not even be able to get one fire-cracker."

"That is a misfortune for a boy, truly," said Mother Goose, "and I wish I could help you, with all my heart, though I don't see how. But stay! I had forgotten;" and diving to the bottom of a capacious pocket, she drew forth a small box, and from it produced three diminutive fire-crackers.

"They are not much," she said, "but such as they are, you are welcome to them, and at least you will not be crackerless. They were given to me, years ago, by the Man in the Moon, when he came down on that trip to Norridge (of which you have learned in your history), and staid overnight at my house, and were part of a pack presented to him by the Man in the South, who dislikes anything that suggests fire. He said they were magic, and you must always make a wish before setting them off."

"Oh, thank you, Mother Goose; they are much better than none at all," said Humpty Dumpty, gratefully; and he looked quite happy once more, as the good old lady nodded "good-by," and proceeded on her way, while the gander waved a yellow webbed foot in farewell.

"I will set off one cracker before breakfast, one at noon, and one to-night," thought Humpty Dumpty, as he tumbled out of bed bright and early next morning; "as I have so few, I must make them go as far as possible."

So as soon as he was dressed he ran into the yard and prepared to salute the "Glorious Fourth."

"Mother Goose said I must make a wish first, so here goes: I wish for a pop-gun, and no end of fire-crackers and torpedoes: now shoot away."

Touching the string with a match, there was a sharp report, and Humpty Dumpty was obliged to dodge, for the air was instantly filled with flying objects. A square package hit him on the nose, a round one landed in his open mouth, while a pop-gun thumped him rudely on the back; and by the time the cracker had burned itself out, he was standing in mute amazement, gazing upon the fulfillment of his wish far beyond his wildest expectations.

"Oh, jolly!" was his first comment, and he soon found courage to stuff his pockets with the crackers and torpedoes until they stood out like balloons, and made him look fatter than ever, when he walked down toward the green, popping at every cat and dog on the way, the envy and admiration of every other boy in Gooseneck.[Pg 515]

Humpty Dumpty was a generous lad, however, and shared his treasures with all his friends, although he would not tell where he got them; and by noon every cracker and torpedo was a thing of the past, and each boy had had a "pop" with the pop-gun.

Meanwhile Humpty Dumpty had been thinking of his second wish, and at last decided to share it with Bo-peep, of whom he was very fond, and for that purpose asked the little shepherdess to walk with him to the large oak-tree on the edge of the village, and while resting in the shade of its green boughs said,

"If you could have whatever you wished for, what would you choose, Bo-peep?"

"Oh, some blue ribbons, and candy," said Bo-peep, "bolivars, and chocolate drops, and such things."

"Then wish for them, and fire off this," said Humpty Dumpty, handing her a cracker.

Bo-peep looked surprised, but did as she was bid; but to the boy's surprise and disappointment, it only "fizzed," and went out.

"It is a poor one," said Bo-peep.

"We will make a squib of it," said Humpty Dumpty; and he quickly broke it in two, and applied a match; and what a squib it was!—for in place of the usual stream of fire, there issued forth a shower of such sugar-plums and bonbons as neither of the children had ever even dreamed of, and yards and yards of blue ribbon, the very color of the summer sky.

Bo-peep clasped her hands, and sat down suddenly on the grass, but Humpty Dumpty calmly heaped her lap with goodies, and twined the ribbon in her sunny hair, and round the neck of her favorite lamb, which had followed them from the village, and while they regaled themselves with the confections under the oak-tree, told her of the wonderful gift given him by dear old Mother Goose.

That afternoon the good people of Gooseneck were startled out of their accustomed quiet by an invitation from Humpty Dumpty to an exhibition of fire-works that evening on the village green; and John Stout, Nimble Dick, and a number of other boys were engaged to build a platform for the occasion.

"The boy must have gone out of his mind," said Mrs. Dumpty, when she heard the news. "I'm afraid that last fall has affected his brain;" and all the villagers shook their heads doubtfully.

They were all on hand, however, at the appointed time, Mother Goose occupying a reserved seat in front; and loud was the laugh and many the jokes made on Humpty Dumpty when he appeared on the platform carrying in his chubby hand one small fire-cracker.

"Have we all come here to see a fat boy set off that little squib?" they asked.

"Wait," said Mother Goose.

And in a few moments their ridicule was turned to wonder; for as the cracker went off, a confused medley of rockets, pin-wheels, Roman candles, blue-lights, and other fire-works fell with a loud noise upon the stage.

"Magic!" "magic!" sounded on all sides, but changed to ohs! and ahs! as a beautiful rocket flew through the air, and burst into a hundred golden balls.

Oh, that was a Fourth of July long to be remembered, for such fire-works had never been seen in Gooseneck before; and when the last piece of all was displayed, showing a figure of Mother Goose herself, surrounded by a rainbow and a shower of silver stars, the delight of the spectators knew no bounds, and cheers for Humpty Dumpty rent the air.

He came forward, his round face all aglow with pleasure, as he bowed and said, "Your thanks, my friends, do not belong to me, but to our beloved Mother Goose, who, to make a poor boy happy, gave him her three magic fire-crackers."

"Au printemps Poiseau nait et chante,

N'avez-vous pas oui sa voix?

Elle est pure, simple, et touchante,

La voix de Poiseau dans les bois."

So sang Julie Garnier, as she trudged with weary little feet up the mountain-side, listening to the birds, and in search of the squaw in charge of the doors of Day and Night. The pretty Indian legend had bewitched her. Here she was wandering away from all who cared for her, to see an old woman who cut up the old moons into stars; and already twilight was making the woods more dusky. The slanting sunbeams made a golden green in the young underbrush; the birds were seeking their nests; night would soon wrap the world in darkness; then what would become of Julie? The good God would protect her, she felt sure. But she was undoubtedly hungry, and yonder, where the road turned, was a great flat stone; on it she might rest, and eat a little ginger cake she happened to have in her pocket. To it she hastened, and what a world of beauty lay before her! It was at the head of a ravine, one of those deep mountain gorges lined with pines and cedars, through which rushed a rapid stream, but beyond this and over it were the dark defiles of the mountain range sweeping away to the north in purple shadows, while the sun tipped the tops of the nearer forest with gold and crimson. Here Julie paused, overcome with the grandeur and beauty her young eyes beheld. She sat down and listened to the noise of the stream beneath, and she watched the birds skimming over the ravine. Then remembering her cake, she took it from her pocket and nibbled it daintily, for it was all the food she had, and she must make it last until she came to the old squaw's wig-wam, where, of course, she would be hospitably regaled. She pushed her daisy-wreathed hat from her head, and leaned against a pine-tree; the soft breeze fanned her hot little head, and played with her brown curls; she drew her knees up and clasped her hands about them, watching the sky change from one bright hue to another. The stream's voice was a lullaby, and slowly, softly fell the fringes of her eyelids; till the bright eyes were closed, and Julie was asleep.

She was so wearied and in so deep a slumber that the approaching stage-coach with its freight of tourists did not disturb her; and so eager was every one to see the famous view, that no one apparently noticed the little sleeping wayfarer, but behind the stage came in a more leisurely manner a private conveyance with only four occupants—a lady and gentleman and two children, all evidently foreigners. The elders were indeed occupied in gazing at the glorious picture Nature here displayed, but the eyes of the children were equally sensitive to smaller objects, and when they beheld a sleeping child, they at once drew the attention of their parents to this interesting incident.

The gentleman bade the driver halt, and assisted his pretty little wife from the carriage. She went hastily forward toward Julie, but as she neared her she stopped, clasped her hands, and turned toward her husband. Her face grew so white that he became alarmed, and asked,

"What is it, ma chère? Are you ill?"

"No, I am not ill; but look at this child—quick! Who is she like?"

The gentleman glanced at Julie, nodded his head, pulled his mustache, and said, briefly, "Yes, I see a resemblance."

"To whom, Max?—say, to whom?"

"To your poor little sister, Marie."

"Yes; is it not strange? Oh, how marvellously like Julie! I must waken her. Is she not lovely, the dear[Pg 516] little creature, sleeping so innocently? Oh, Max, perhaps—perhaps—"

"Waken her, Marie. Ask her name."

The lady touched Julie gently, but the tired child slept too soundly for the light touch to arouse her, and it was not until she had kissed her on the cheek—the little red and brown cheek—that Julie opened her eyes. Then the lady gave a hysterical scream, not very loud, but enough to frighten Julie, whose eyes grew bigger and browner every moment.

"Oh, those eyes are Julie's!" said the lady.

"Of course they are, madame," replied Julie. "And are you the squaw?"

"Am I what? Is the child dreaming? What is your name, mon enfant?"

"My name is— But why do you ask, madame? and where am I? Oh, I know: I am on my way to see the old Indian squaw who lives up here in the mountains, and it is getting late. I was very weary, and I fell asleep."

"Your name, my child—tell me your name, that I may know if you are Julie Garnier's child."

"Yes, madame, I am Julie Garnier." With that the little lady embraced her so warmly, and gave her so many kisses, that Julie strove to get away from her.

"Children," said the lady, "come here; this is your cousin, little Julie Garnier, whose mother is my dear sister, from whom I have long been separated. Max, we must take the child home."

"Where are you staying, little one?" asked the gentleman, in a heavy voice, which made Julie shrink toward the lady.

"I am staying with Quillie Coit at Mr. Brown's," was Julie's answer, for she dared not now urge her errand, and was much perplexed by all this agitation. The children were standing beside her, gazing curiously, but not unkindly; the little lady was wiping her eyes; the gentleman was holding a consultation with the driver. It ended by their all getting again into the vehicle, Madame Von Boden taking Julie in her arms, and pouring into her astonished ears sweet caressing words, in her own beloved language, about Julie's own dear mother; their home in France; her marriage to a Prussian; the marriage of Julie's mother to a Frenchman; the dreadful war; a separation; a long silence, in which they had heard nothing about Madame Garnier, who was so proud in her poverty; fears that she was dead; the certain knowledge that her husband, Julie's father, was really dead; and now this happy discovery. It was almost too much for Julie, coming as it did in the midst of her own strange adventure, and she could hardly believe it to be all true; but she submitted with a good grace, stifling her regret at not accomplishing her purpose, since this kind little aunt seemed to be so overjoyed. The driver knew where Mr. Brown lived, and just as Mr. Brown's tired horses were being harnessed, and nurse in weariful anxiety was listening to the comfort which Quillie was trying to whisper to her, this strange vehicle was heard coming down the lane. Every one rushed to the gate—Mr. and Mrs. Brown, the farm hands, the kitchen folk, nurse, and even Quillie in her night-gown; for there was Julie at last—poor tired little Julie—drooping, faint, and tearful.

No one scolded, not even nurse, who had been most sorely tried; and Madame Von Boden, with many mistakes in her use of English, and with much excitement, related her adventure. Of course it was considered wonderful, and the travellers were prevailed upon to remain at Mr. Brown's overnight.

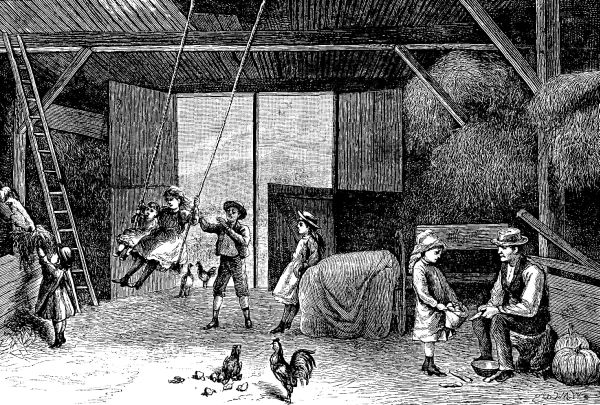

A GOOD TIME IN THE BARN.

A GOOD TIME IN THE BARN.

You would not have supposed that following day, when all the children were having a good time in the barn—swinging, feeding the horses, gathering eggs, giving the hens a double supply of corn, and in every way making the most of a barn's generous resources—that one little maiden among them was a heroine of romance, a very tired little heroine, quite contented to watch the swallows and pigeons, and gaze at the far-away mountain-tops. But so it was, and so it often is; for, as the French say, "'tis the unexpected that happens;" and when Madame Garnier heard that her little Julie had found her aunt Marie, and that the little cousins were all housed under one roof, and having much happiness together, her own joy was great.

Julie promised faithfully never to undertake any more expeditions without the consent of her guardians, and she begged Quillie never to say anything more about the squaw; but Fred was allowed, by special grace, to call her Miss Van Winkle; for Fred had a funny way peculiar to himself which seldom excited wrath.

Later in the season, when Madame Garnier was able to join Julie, and Mr. and Mrs. Coit came up from the city, the Von Bodens gave a pretty fête to all the children, and at the conclusion of it Quillie was invited to accompany Julie and her cousins, and spend the winter in Paris, which was so nice an opportunity for Quillie to acquire a good French accent that her father and mother felt obliged to accept.

Artie and Will had a great talk about this, and Fred said he wished Miss Van Winkle would just take another nap in the woods, to see what else might happen; possibly next time he would get an invitation from the Prince of Wales to go yachting.

But Miss Van Winkle took her naps at home after that, though she still thinks of the old squaw every time she looks at the moon.

The following gratifying communication comes from the librarian of a large public library in Illinois:

May prosperity attend your most excellent Young People! I keep it on file in the reading-room, and it is pleasant to note the eagerness with which its pages are devoured by the boys and girls who daily throng our rooms. The paper is doing a noble work among them, not only in amusing them, but by giving them solid information upon a great variety of subjects in a most delightful way, thus giving them a taste for a class of reading almost always pronounced "dry" by the youngsters. It supplies a long-felt want in juvenile literature. Again I say, success to your noble enterprise!

Sunderland, Vermont.

I am eleven years old, and I live in the country. Papa has a very large farm.

I have three sisters. The oldest is in Philadelphia at school. I am next to the oldest. My sister Annie and I have the care of the chickens and turkeys. We have doves which are so tame they will fly and alight on our hands to get corn. We had a little pet crow, but it died last night. We are going to get another one. We have wild strawberries. They are very plenty this year.

Jennie G.

Thompsonville, Connecticut.

I take Young People. I think the engravings are so pretty. After I went to bed last night, I could hear the people down stairs talking. After a while papa began to read to mamma. I listened, and soon made out that he was reading from Young People about "The Boys and Uncle Josh." Papa laughed so that he had to stop reading several times. I am twelve years old.

Minnie S.

Sweetwater, Tennessee.

I like Young People very much, and I read all the letters from the children. I have been going to school, but we have a vacation now. I am not as well read as S. Cassius E——, but I am a year younger. I have read some poems of Tennyson and other poets, and the whole of Goodrich's History of Rome and Greece. I have a crippled sister who has read a great deal, and she tries to make me read more, but I spend most of my leisure time in practicing music. I am learning to cook, and I am going to try some of the recipes sent to the cooking club. I am going to my grandma's soon, and I expect to have a nice time. She lives in a shady dell, and we call it "Dell Delight."

Susan M.

Chapel Hill, Georgia.

I am a little boy eleven years old. My aunt in New York sends me Young People. I like the stories and the letter-box very much. I live twenty-five miles from the city of Atlanta. We have had whortleberries, plums, and mulberries this summer. I go to school, and I walk there every morning. It is a mile and a half away. I have but one pet, a dog named Rover. My sister Addie has three cats. One of them catches chickens, and my dog sucks eggs.

G. F. A. V.

East Cambridge, Massachusetts.

You can hardly imagine how much I like Young People, and how anxiously I wait till it comes. I have two canaries. Dick is yellow, and Bill is linnet green. Dick is tamer than Bill.

Fred L. Z.

Newport, Kentucky.

I am eight years old. I go to school, and am in the Second Reader. We have all the numbers of the Young People, and papa is going to have the first twenty-six bound. Mamma liked it so much that New-Year's she took it for my cousins.

When we lived in Illinois papa was Adams Express agent, and we had a horse named Adam. When my brother Charlie was four years old he went to Sunday-school, and once when the teacher asked the class who was the first man, Charlie yelled out, "Adams Express man!"

The first thing I read when my paper comes, are the little letters in the Post-office Box.

Willie W.

New York City.

If any of the readers of Young People have pet turtles, this is what they can feed them with: Mine eat flies, bugs, worms, and fish. One of mine is so small that a large three-cent piece would cover it. Bull-frogs will eat these same things too.

I think Young People is splendid. The story of "The Moral Pirates" is the best yet.

Lyman C.

Schuylersville, New York.

Young People is the best paper I ever saw. I like the story of "The Moral Pirates" best of all, and I hope it will be a long one. I have two brothers, both younger than I am. We do not go to school, but study at home. I would like to know whether you are going to have a binding for Young People. I read the letters in the Post-office Box over and over, and enjoy them very much. We raise a good many chickens, and I have lots of pet ones, all of which have names.

Keble D.

We have already stated in the Post-office Box that an ornamental cover will be ready when the first volume is concluded.

Niagara Falls, New York.

I like Young People very much, especially the story of "The Moral Pirates." I always read it the minute it comes from the post-office.

J. M. P.

New York City.

I am twelve years old, and a constant reader of Young People. I am the boy who was buried under the snow, in the story called "Ned's Snow-House," in Young People No. 18. I was very much surprised when I read it, and it was some time before papa found out who wrote it. I was nine years old when it happened.

Warren S. B.

Taiohae, Nukahiva, Marquesas Islands.

I am the only white girl in this place that can talk English. I have two brothers and one little sister. I am the eldest, and am nearly twelve years old. It is very wild out here. In one of these islands the people eat each other. There is no school here, and mamma teaches me my lessons. Papa gets Harper's Weekly, and Young People came with it. I send now to subscribe for it.

Isabella F. H.

New Orleans, Louisiana.

I am seven years old, and I like Young People so much! I often go out to Spanish Fort, on Lake Pontchartrain. They have a pair of goats and a little carriage there that children can ride in for five cents a round trip.

I have a pet dog named Jack, and four pet chickens; and I had a little canary, but it got sick and died. My dog chases my chickens all day long, so that I have to whip him.

Charlie S.

Butteville, Oregon.

I live on the banks of the Willamette River. We are having lots of rain here now. I thought I would write and tell you how much I liked the story of "Across the Ocean." I liked "The Story of George Washington" too. I am eleven years old.

W. B.

Mexia, Texas.

I have had a present of a little canary, but it does not sing. The lady who gave it to me said it had been a beautiful singer, but it became sick. She gave it castor-oil, and it recovered, but has never sung since that time. The little bird has a nice cage, always fresh water for drinking and bathing, bird seed, fish-bone, and plenty of green leaves and grass. I wish some one could tell me how to make it sing again.

Adele M.

It is not easy to restore song to a silent canary, and as you will see from a letter in this "Post-office Box," you are not the only one seeking a remedy for this trouble. The companionship of a singing-bird will sometimes arouse a canary to display its own musical talent. Your bird may be silent from overfeeding, as too much green food, like lettuce leaves, makes a bird grow fat and stupid, and less likely to sing. Try to place your bird near singing canaries for a few weeks, if you can, and if that does not affect it favorably, we fear nothing will.

Cora R. Price and Mamie E. Evans both send the following legend of the forget-me-not, in answer to the inquiry of "A Constant Reader": Some flower seeds having been cast away by a traveller from a distant country, they fell by the edge of a lake. Some time afterward two lovers were wandering by the lake's side, and the lady, seeing the strange flowers, entreated her companion to gather some. As the gallant knight reached to pluck the blossoms, he fell in a quicksand, and was drawn into the treacherous pool, flinging the flowers at the maiden's feet, and crying, "Forget me not," as he disappeared forever.

Here is still another fanciful legend, sent by Ethel Sophia Mason: When Adam and Eve were driven from Eden, the flowers all shrank away from Eve with the exception of a little blue blossom, which Eve had named "heaven's flower," as its color was so much like the blue sky. As Eve passed, it seemed to murmur, "Forget me not," and she gratefully gathered it, saying, "Henceforth, dear flower, that shall be thy name." It was the only plant transplanted from Paradise, or that survived the flood. It is said to have the power of speaking at midnight, and telling the legend of its sweet name.

Troy, New York.

I am very fond of natural history and botany. The other day I was out walking with my teacher, and I saw a caterpillar, or, as my little friend Ada says, a pillarcat! It had a black body, with a red stripe running along its back. I wish some one would tell me what kind it was. I would like "Wee Tot's" address.

Lena.

The address of "Wee Tot" was given with her letter in Post-office Box No. 26. Walter H. P., who wrote about caterpillars in Post-office Box No. 31, can perhaps tell you the name of the caterpillar, and what kind of butterfly or moth it produces, although you describe only its color. Had you stated its size, length, and other peculiarities, it would be easier to give you its name.

Chicago, Illinois.

I like to read Young People very much, but I like the pictures best of all. I have shown the paper to the boys in our neighborhood, and have got a good many of them to take it. I never drew any Wiggles before, but I like them. I am twelve years old, and I work for a dentist.

Henry B. A.

San Antonio, Texas.

I am very much interested in the Wiggles, and I read all the poetry in Young People. I like the Letter-box better than anything. I get my paper from the bookstore here. I wish you would tell me where I can buy a cannon, a real cannon, so I can shoot on the Fourth of July.

M. L. J.

San Bernardino, California.

I am twelve years old. I have a little dog and a big cat. They play together all the time. Sometimes when they are playing they get so tired that they lie down together and go to sleep. My sister had a wax doll. One day she left it on the table, and my dog got it, and tore off all its hair.

Willard H. H.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

We have three cats. One is black and white, and it jumps into mamma's lap every time it comes into the room. And we have a dear little colt one month old. When the man puts it in the field it races all around, and seems to enjoy itself so much. I am nearly ten years old.

Bertha E.

Sherburne Four Corners, New York.

In Young People No. 32 a little girl asks for a recipe for bread. Here is one: For a small baking of bread take one medium-sized potato, boil it, and mash it fine; add a heaping table-spoonful of flour, and pour over it a tea-cupful of boiling water; let it stand until it is lukewarm, then stir in two table-spoonfuls of yeast—my mamma uses home-made—and set it in a warm place (not too warm) to rise. When it comes up light, add a cup of lukewarm water, a tea-spoonful of salt, and flour enough to make a batter. Let this rise, and then mix in flour until it is stiff: your mamma will tell you when it is right. You must let this rise again, and then make it into loaves, using as little dry flour as possible in this last process. If you wish to make biscuit, a little butter or lard improves it After the mixture is in the pan, you must let it rise again before putting it into the oven.

I was ten years old last Decoration-day. I have never made any bread yet, but mamma is going to let me try soon.

Fannie H.

I tried Nellie H.'s recipe for candy, and I think it is real nice. We have a large Newfoundland dog. He will carry a basket, and will catch a ball, and he will give you his paw. His name is Spot.

I will exchange pressed ferns with Emma Foltz in the fall.

Minta Holman,

Leavenworth, Kansas.

I am making a collection of bugs, and would like to exchange with little boys and girls in the West who take Young People. I have only collected a few bugs yet.

G. Fred Kimberly,

Auburn, New York.

Concord, New Hampshire.

Here is a recipe for very nice Graham bread for Puss Hunter. I make it very often for my papa, and he likes it better than any other bread. I am fourteen years old. Take one quart of lukewarm water, half a coffee-cup of yeast, two table-spoonfuls of lard, two table-spoonfuls of white sugar, one tea-spoonful of salt, one tea-spoonful of soda; melt the sugar and lard in the warm water; stir in very smoothly three pints of flour; then pour in the yeast and the soda. Beat it hard for a few minutes, and then put it in a warm place to rise. This is the sponge, and will take about eight hours, or all day, to rise. Then at night add two quarts of Graham meal and one cup of sugar, and, if it is too stiff, a little more warm water. Let this mixture rise overnight. In the morning stir it down with a spoon to get the air out, and put it in the pans. I[Pg 519] let it rise in the pans about two hours before I put it in the oven. This recipe will make two good-sized loaves. Do all the mixing with a spoon, as it makes it sticky if you touch your hands to it. I wish Puss Hunter, if she tries it, would tell me if she has success.

Rosie W. R.

I am eleven years old. I like Young People very much. I have a flower garden of my own, and two pets—a canary named Phil, and a cat. My bird will not sing. Can any correspondent tell me what to do for it? My papa has a pet crow. It is very funny.

I would like to exchange pressed flowers with any little girl in the West.

Dotty Seaman,

Richmond, Staten Island, New York.

I have been taking Young People from the first number, and I like it ever so much.

I have a little brother named Charlie, and he is a great favorite with everybody. He is very sharp for a little boy three years old. Last year we spent the summer in Cincinnati, and mamma took Charlie to the circus. When the procession came out he said, "Oh, mamma, look at the elephant, and the camel behind him!" Mamma thought he did not know what a camel was, so when they came around again mamma said, "There is the elephant, Charlie; and what is behind him now?" Charlie did not answer, so mamma asked him again. Then he looked up at her, and said, in a very droll tone, "His tail."

I am collecting stamps, and would gladly exchange with any readers of Young People. I am twelve years old.

Harry Starr Kealhofer,

Memphis, Tennessee.

If any birds' egg collector of California or the Western States will exchange eggs with me, I will be much pleased. I will send one dozen different kinds for as many of his. They are as follows: Chaffinch, quail, kingbird, crested jay, brown thrush, mocking-bird, sparrow, cat-bird, bluebird, peewee, swamp blackbird, wren. I will be obliged if any boy will send me his address, and a list of the varieties he is willing to exchange for mine.

Harry Robertson,

P. O. Box 89, Danville, Virginia.

Willie Atkinson.—There are about 225 islands in the Feejee group, of which 140 are inhabited. Viti Levu is the largest and most populous, being 97 miles from east to west, and 64 from north to south. Next to this is Vanua Levu, which is 115 miles long, and about 25 miles wide. The whole group contains, exclusive of coral islets, an area of about 5500 square miles of dry land.

George B.—The stamps you require are somewhat rare, but you may be able to obtain them by means of the exchanges offered by our young correspondents.

Lily B., Mabel C. L., and others.—Your puzzles are very skillfully made, but are rendered unavailable by their solutions, which are precisely the same as those of puzzles published in former numbers of the Young People. Correspondents by taking special notice of the fact, which we have already stated, that we can not repeat solutions, will save themselves from many disappointments.

Favors are acknowledged from Penn W., D. Kopp, Charlie Heyl, Laura Bingham, Walter Willard, Lizzie Brewster, George B. McLaughlin, Louis D. Seaman.