Title: Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Author: Various

Editor: Harry Bates

Release date: June 27, 2009 [eBook #29255]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

On Sale the First Thursday of Each Month

W. M. CLAYTON, Publisher

HARRY BATES, Editor

DR. DOUGLAS M. DOLD, Consulting Editor

That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid, by leading

writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the

Authors' League of America;

That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS MONTHLY, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE, WESTERN ADVENTURES, and FOREST AND STREAM.

More than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

| VOL. III, No. 3 | CONTENTS | SEPTEMBER, 1930 |

| COVER DESIGN | Painted in Water-Colors from a Scene in "Marooned Under the Sea." | H. W. WESSOLOWSKI |

| A PROBLEM IN COMMUNICATION | MILES J. BREUER, M.D. | 293 |

| The Delivery of His Country into the Clutches of a Merciless, Ultra-Modern Religion Can Be Prevented Only by Dr. Hagstrom's Deciphering an Extraordinary Code. | ||

| JETTA OF THE LOWLANDS | RAY CUMMINGS | 310 |

| Fantastic and Sinister Are the Lowlands into Which Philip Grant Descends on His

Dangerous Assignment. (Beginning a Three-Part Novel.) | ||

| THE TERRIBLE TENTACLES, OF L-472 | SEWELL PEASLEE WRIGHT | 332 |

| Commander John Hanson of the Special Patrol Service Records Another of His Thrilling Interplanetary Assignments. | ||

| MAROONED UNDER THE SEA | PAUL ERNST | 346 |

| Three Men Stick Out a Strange and Desperate Adventure Among the Incredible Monsters of the Dark Sea Floor. | ||

| THE MURDER MACHINE | HUGH B. CAVE | 377 |

| Four Lives Lay Helpless Before the Murder Machine, the Uncanny Device by Which Hypnotic Thought Waves Are Filtered Through Men's Minds to Mold Them Into Murdering Tools. | ||

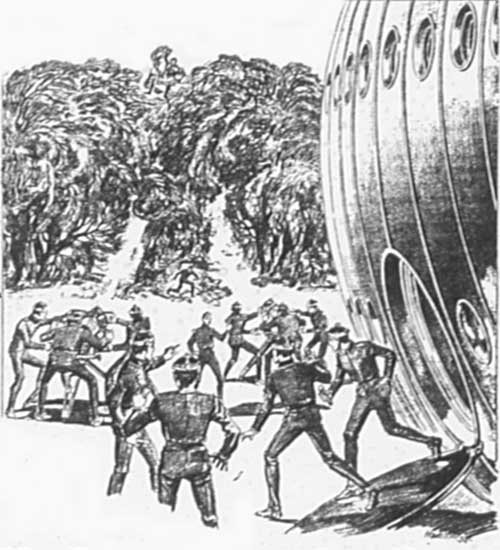

| THE ATTACK FROM SPACE | CAPTAIN S. P. MEEK | 390 |

| From a Far World Came Monstrous Invaders Who Were All the More Terrifying Because Invisible. | ||

| EARTH, THE MARAUDER | ARTHUR J. BURKS | 408 |

| Martian Fire-Balls and the Terrific Moon-Cubes Wreak Tremendous Destruction on

Helpless Earth in the Final Death Struggle of the Warring Worlds. (Conclusion.) | ||

| THE READERS' CORNER | ALL OF US | 423 |

| A Meeting Place for Readers of Astounding Stories. | ||

Issued monthly by Publishers' Fiscal Corporation, 80 Lafayette St., New York, N. Y. W. M. Clayton, President: Nathan Goldmann, Secretary. Entered as second-class matter December 7, 1929, at the Post Office at New York, N. Y., under Act of March 3, 1879. Title registered as a Trade Mark in the U. S. Patent Office. Member Newsstand Group—Men's List. For advertising rates address E. R. Crowe & Co., Inc., 25 Vanderbilt Ave., New York; or 225 North Michigan Ave., Chicago.

I saw the famous Science Temple with its constant stream

of worshippers.

I saw the famous Science Temple with its constant stream

of worshippers.

(This part is related by Peter Hagstrom, Ph.D.)

"

The Ability to communicate ideas from one individual to another," said a professor of sociology to his class, "is the principal distinction between human beings and their brute forbears. The increase and refinement of this ability to communicate is an index of the degree of civilization of a people. The more civilized a people, the more perfect their ability to communicate, especially under difficulties and in emergencies."

As usual, the observation burst harmlessly over the heads of most of the students in the class, who were preoccupied with more immediate things—with the evening's movies and the week-end's dance. But upon two young men in the class, it made a powerful impres[Pg 294]sion. It crystallized within them certain vague conceptions and brought them to a conscious focus, enabling the young men to turn formless dreams into concrete acts. That is why I take the position that the above enthusiastic words of this sociology professor, whose very name I have forgotten, were the prime moving influence which many years later succeeded in saving Occidental civilization from a catastrophe which would have been worse than death and destruction.

One of these young men was myself, and the other was my lifelong friend and chum, Carl Benda, who saved his country by solving a tremendously difficult scientific puzzle in a simple way, by sheer reasoning power, and without apparatus. The sociology professor struck a responsive chord in us: for since our earliest years we had wigwagged to each other as Boy Scouts, learned the finger alphabet of the deaf and dumb so that we might maintain communication during school hours, strung a telegraph wire between our two homes, admired Poe's "Gold Bug" together and devised boyish cipher codes in which to send each other postcards when chance separated us. But we had always felt a little foolish about what we considered our childish hobbies, until the professor's words suddenly roused us to the realization that we were a highly civilized pair of youngsters.

Not only did we then and there cease feeling guilty about our secret ciphers and our dots and dashes, but the determination was born within us to make of communication our life's work. It turned out that both of us actually did devote our lives to the cause of communication; but the passing years saw us engaged in widely and curiously divergent phases of the work. Thirty years later, I was Professor of the Psychology of Language at Columbia University, and Benda was Maintenance Engineer of the Bell Telephone Company of New York City; and on his knowledge and skill depended the continuity and stability of that stupendously complex traffic, the telephone communication of Greater New York.

Since our ambitious cravings were satisfied in our everyday work, and since now ordinarily available methods of communication sufficed our needs, we no longer felt impelled to signal across the house-tops with semaphores nor to devise ciphers that would defy solution. But we still kept up our intimate friendship and our intense interest in our beloved subject. We were just as close chums at the age of fifty as we had been at ten, and just as thrilled at new advances in communication: at television, at the international language, at the supposed signals from Mars.

That was the state of affairs between us up to a year ago. At about that time Benda resigned his position with the New York Bell Telephone Company to accept a place as the Director of Communication in the Science Community. This, for many reasons, was a most amazing piece of news to myself and to anyone who knew Benda.

Of course, it was commonly known that Benda was being sought by Universities and corporations: I know personally of several tempting offers he had received. But the New York Bell is a wealthy corporation and had thus far managed to hold Benda, both by the munificence of its salary and by the attractiveness of the work it offered him. That the Science Community would want Benda was easy to understand; but, that it could outbid the New York Bell, was, to say the least, a surprise.

Furthermore, that a man like Benda would want to have anything at all to do with the Science Community seemed strange enough in itself. He had the most practical common sense—well-balanced habits of thinking and living, supported by an intellect so[Pg 295] clear and so keen that I knew of none to excel it. What the Science Community was, no one knew exactly; but that there was something abnormal, fanatical, about it, no one doubted.

The Science Community, situated in Virginia, in the foothills of the Blue Ridge, had first been heard of many years ago, when it was already a going concern. At the time of which I now speak, the novelty had worn off, and no one paid any more attention to it than they do to Zion City or the Dunkards. By this time, the Science Community was a city of a million inhabitants, with a vast outlying area of farms and gardens. It was modern to the highest degree in construction and operation; there was very little manual labor there; no poverty; every person had all the benefits of modern developments in power, transportation, and communication, and of all other resources provided by scientific progress.

So much, visitors and reporters were able to say.

The rumors that it was a vast socialistic organization, without private property, with equal sharing of all privileges, were never confirmed. It is a curious observation that it was possible, in this country of ours, for a city to exist about which we knew so little. However, it seemed evident from the vast number and elaboration of public buildings, the perfection of community utilities such as transportation, streets, lighting, and communication, from the absence of individual homes and the housing of people in huge dormitories, that some different, less individualistic type of social organization than ours was involved. It was obvious that as an organization, the Science Community must also be wealthy. If any of its individual citizens were wealthy, no one knew it.

I knew Benda as well as I knew myself, and if I was sure of anything in my life, it was that he was not the type of man to leave a fifty thousand dollar job and join a communist city on an[Pg 296] equal footing with the clerks in the stores. As it happens, I was also intimately acquainted with John Edgewater Smith, recently Power Commissioner of New York City and the most capable power engineer in North America, who, following Benda by two or three months, resigned his position, and accepted what his letter termed the place of Director of Power in the Science Community. I was personally in a position to state that neither of these men could be lightly persuaded into such a step, and that neither of them would work for a small salary.

Benda's first letter to me stated that he was at the Science Community on a visit. He had heard of the place, and while at Washington on business had taken advantage of the opportunity to drive out and see it. Fascinated by the equipment he saw there, he had decided to stay a few days and study it. The next letter announced his acceptance of the position. I would give a month's salary to get a look at those letters now; but I neglected to preserve them. I should like to see them because I am curious as to whether they exhibit the characteristics of the subsequent letters, some of which I now have.

As I have stated, Benda and I had been on the most intimate terms for forty years. His letters had always been crisp and direct, and thoroughly familiar and confidential. I do not know just how many letters I received from him from the Science Community before I noted the difference, but I have one from the third month of his stay there (he wrote every two or three weeks), characterized by a verbosity that sounded strange for him. He seemed to be writing merely to cover the sheet, trifles such as he had never previously considered worth writing letters about. Four pages of letter conveyed not a single idea. Yet Benda was, if anything, a man of ideas.

There followed several months of letters like that: a lot of words, eva[Pg 297]sion of coming to the point about anything; just conventional letters. Benda was the last man to write a conventional letter. Yet, it was Benda writing them: gruff little expressions of his, clear ways of looking at even the veriest trifles, little allusion to our common past: these things could neither have been written by anyone else, nor written under compulsion from without. Something had changed Benda.

I pondered on it a good deal, and could think of no hypothesis to account for it. In the meanwhile, New York City lost a third technical man to the Science Community. Donald Francisco, Commissioner of the Water Supply, a sanitary engineer of international standing, accepted a position in the Science Community as Water Director. I did not know whether to laugh and compare it to the National Baseball League's trafficking in "big names," or to hunt for some sinister danger sign in it. But, as a result of my ponderings, I decided to visit Benda at The Science Community.

I wrote him to that effect, and almost decided to change my mind about the visit because of the cold evasiveness of the reply I received from him. My first impulse on reading his indifferent, lackadaisical comment on my proposed visit was to feel offended, and determine to let him alone and never see him again. The average man would have done that, but my long years of training in psychological interpretation told me that a character and a friendship built during forty years does not change in six months, and that there must be some other explanation for this. I wrote him that I was coming. I found that the best way to reach the Science Community was to take a bus out from Washington. It involved a drive of about fifty miles northwest, through a picturesque section of the country. The latter part of the drive took me past settlements that looked as though they might be in about the same stage of progress as they had been during the American Revolution. The city of my destination was back in the hills, and very much isolated. During the last ten miles we met no traffic at all, and I was the only passenger left in the bus. Suddenly the vehicle stopped.

"Far as we go!" the driver shouted.

I looked about in consternation. All around were low, wild-looking hills. The road went on ahead through a narrow pass.

"They'll pick you up in a little bit," the driver said as he turned around and drove off, leaving me standing there with my bag, very much astonished at it all.

He was right. A small, neat-looking bus drove through the pass and stopped for me. As I got in, the driver mechanically turned around and drove into the hills again.

"They took up my ticket on the other bus," I said to the driver. "What do I owe you?"

"Nothing," he said curtly. "Fill that out." He handed me a card.

An impertinent thing, that card was. Besides asking for my name, address, nationality, vocation, and position, it requested that I state whom I was visiting in the Science Community, the purpose of my visit, the nature of my business, how long I intended to stay, did I have a place to stay arranged for, and if so, where and through whom. It looked for all the world as though they had something to conceal; Czarist Russia couldn't beat that for keeping track of people and prying into their business. Sign here, the card said.

It annoyed me, but I filled it out, and, by the time I was through, the bus was out of the hills, traveling up the valley of a small river; I am not familiar enough with northern Virginia to say which river it was. There was much machinery and a few people in the broad fields. In the distance ahead was a mass of chimneys and the cupolas of iron-works, but no smoke.[Pg 298]

There were power-line towers with high-tension insulators, and, far ahead, the masses of huge elevators and big, square buildings. Soon I came in sight of a veritable forest of huge windmills.

In a few moments, the huge buildings loomed up over me; the bus entered a street of the city abruptly from the country. One moment on a country road, the next moment among towering buildings. We sped along swiftly through a busy metropolis, bright, airy, efficient looking. The traffic was dense but quiet, and I was confident that most of the vehicles were electric; for there was no noise nor gasoline odor. Nor was there any smoke. Things looked airy, comfortable, efficient; but rather monotonous, dull. There was a total lack of architectural interest. The buildings were just square blocks, like neat rows of neat boxes. But, it all moved smoothly, quietly, with wonderful efficiency.

My first thought was to look closely at the people who swarmed the streets of this strange city. Their faces were solemn, and their clothes were solemn. All seemed intently busy, going somewhere, or doing something; there was no standing about, no idle sauntering. And look whichever way I might, everywhere there was the same blue serge, on men and women alike, in all directions, as far as I could see.

The bus stopped before a neat, square building of rather smaller size, and the next thing I knew, Benda was running down the steps to meet me. He was his old gruff, enthusiastic self.

"Glad to see you, Hagstrom, old socks!" he shouted, and gripped my hand with two of his. "I've arranged for a room for you, and we'll have a good old visit, and I'll show you around this town."

I looked at him closely. He looked healthy and well cared-for, all except for a couple of new lines of worry on his face. Undoubtedly that worn look meant some sort of trouble.

(This part is interpolated by the author into Dr. Hagstrom's narrative.)

Every great religion has as its psychological reason for existence the mission of compensating for some crying, unsatisfied human need. Christianity spread and grew among people who were, at the time, persecuted subjects or slaves of Rome; and it flourished through the Middle Ages at a time when life held for the individual chiefly pain, uncertainty, and bereavement. Christianity kept the common man consoled and mentally balanced by minimizing the importance of life on earth and offering compensation afterwards and elsewhere.

A feeble nation of idle dreamers, torn by a chaos of intertribal feuds within, menaced by powerful, conquest-lusting nations from without, Arabia was enabled by Islam, the religion of her prophet Mohammed, to unite all her sons into an intense loyalty to one cause, and to turn her dream-stuff into reality by carrying her national pride and honor beyond her boundaries and spreading it over half the known world.

The ancient Greeks, in despair over the frailties of human emotion and the unbecomingness of worldly conduct, which their brilliant minds enabled them to recognize clearly but which they found themselves powerless to subdue, endowed the gods, whom they worshipped, with all of their own passions and weaknesses, and thus the foolish behavior of the gods consoled them for their own obvious shortcomings. So it goes throughout all of the world's religions.

In the middle of the twentieth century there were in the civilized world, millions of people in whose lives Christianity had ceased to play any part. Yet, psychically—remember, "psyche" means "soul"—they were just as sick and unbalanced, just as[Pg 299] much in need of some compensation as were the subjects of the early Roman empire, or the Arabs in the Middle Ages. They were forced to work at the strained and monotonous pace of machines; they were the slaves, body and soul, of machines; they lived with machines and lived like machines—they were expected to be machines. A mechanized mode of life set a relentless pace for them, while, just as in all the past ages, life and love, the breezes and the blue sky called to them; but they could not respond. They had to drive machines so that machines could serve them. Minds were cramped and emotions were starved, but hands must go on guiding levers and keeping machines in operation. Lives were reduced to such a mechanical routine that men wondered how long human minds and human bodies could stand the restraint. There is a good deal in the writings of the times to show that life was becoming almost unbearable for three-fourths of humanity.

It is only natural, therefore, that Rohan, the prophet of the new religion, found followers more rapidly than he could organize them. About ten years before the visit of Dr. Hagstrom to his friend Benda, Rohan and his new religion had been much in the newspapers. Rohan was a Slovak, apparently well educated in Europe. When he first attracted attention to himself, he was foreman in a steel plant at Birmingham, Alabama. He was popular as an orator, and drew unheard-of crowds to his lectures.

He preached of Science as God, an all-pervading, inexorably systematic Being, the true Center and Motive-Power of the Universe; a Being who saw men and pitied them because they could not help committing inaccuracies. The Science God was helping man become more perfect. Even now, men were much more accurate and systematic than they had been a hundred years ago; men's lives were ordered and rhythmic, like natural laws, not like the chaotic emotions of beasts and savages.

Somehow, he soon dropped out of the attention of the great mass of the public. Of course, he did so intentionally, when his ideas began to crystallize and his plans for his future organization began to form. At first he had a sort of church in Birmingham, called The Church of the Scientific God. There never was anything cheap nor blatant about him. When he moved his church from Birmingham to the Lovett Branch Valley in northern Virginia, he was hardly noticed. But with him went seven thousand people, to form the nucleus of the Science Community.

Since then, some feature writer for a metropolitan Sunday paper has occasionally written up the Science Community, both from its physical and its human aspects. From these reports, the outstanding bit of evidence is that Rohan believes intensely in his own religion, and that his followers are all loyal worshippers of the Science God. They conceive the earth to be a workshop in which men serve Science, their God, serving a sort of apprenticeship during which He perfects them to the state of ideal machines. To be a perfect machine, always accurate, with no distracting emotions, no getting off the track—that was the ideal which the Great God Science required of his worshippers. To be a perfect machine, or a perfect cog in a machine, to get rid of all individuality, all disturbing sentiment, that was their idea of supreme happiness. Despite the obvious narrowness it involved, there was something sublime in the conception of this religion. It certainly had nothing in common with the "Christian Science" that was in vogue during the early years of the twentieth Century; it towered with a noble grandeur above that feeble little sham.

The Science Community was organized like a machine: and all men played their parts, in government, in labor, in administration, in production, like per[Pg 300]fect cogs and accurate wheels, and the machine functioned perfectly. The devotees were described as fanatical, but happy. They certainly were well trained and efficient. The Science Community grew. In ten years it had a million people, and was a worldwide wonder of civic planning and organization; it contained so many astonishing developments in mechanical service to human welfare and comfort that it was considered as a sort of model of the future city. The common man there was provided with science-produced luxuries, in his daily life, that were in the rest of the world the privilege of the wealthy few—but he used his increased energy and leisure in serving the more devotedly, his God, Science, who had made machines. There was a great temple in the city, the shape of a huge dynamo-generator, whose interior was worked out in a scheme of mechanical devices, and with music, lights, and odors to help in the worship.

What the world knew the least about was that this religion was becoming militant. Its followers spoke of the heathen without, and were horrified at the prevalence of the sin of individualism. They were inspired with the mission that the message of God—scientific perfection—must be carried to the whole world. But, knowing that vested interests, governments, invested capital, and established religions would oppose them and render any real progress impossible, they waited. They studied the question, looking for some opportunity to spread the gospel of their beliefs, prepared to do so by force, finding their justification in their belief that millions of sufferers needed the comforts that their religion had given them. Meanwhile their numbers grew.

Rohan was Chief Engineer, which position was equal in honor and dignity to that of Prophet or High Priest. He was a busy, hard-worked man, black haired and gaunt, small of stature and fiery eyed; he looked rather like an overworked department-store manager rather than like a prophet. He was finding his hands more full every day, both because of the extraordinary fertility of his own plans and ideas, and because the Science Community was growing so rapidly. Among this heterogenous mass of proselyte strangers that poured into the city and was efficiently absorbed into the machine, it was yet difficult to find executives, leaders, men to put in charge of big things. And he needed constantly more and more of such men.

That was why Rohan went to Benda, and subsequently to others like Benda. Rohan had a deep knowledge of human nature. He did not approach Benda with the offer of a magnanimous salary, but came into Benda's office asking for a consultation on some of the puzzling communication problems of the Science Community. Benda became interested, and on his own initiative offered to visit the Science Community, saying that he had to be in Washington anyway in a few days. When he saw what the conditions were in the Science Community, he became fascinated by its advantages over New York; a new system to plan from the ground up; no obsolete installation to wrestle with; an absolutely free hand for the engineer in charge; no politics to play; no concessions to antiquated city construction, nor to feeble-minded city administration—just a dream of an opportunity. He almost asked for the job himself, but Rohan was tactful enough to offer it, and the salary, though princely, was hardly given a thought.

For many weeks Benda was absorbed in his job, to the exclusion of all else. He sent his money to his New York bank and had his family move in and live with him. He was happy in his communication problems.

"Give me a problem in communication and you make me happy," he wrote[Pg 301] to Hagstrom in one of his early letters.

He had completed a certain division of his work on the Science Community's communication system, and it occurred to him that a few days' relaxation would do him good. A run up to New York would be just the thing.

To his amazement, he was not permitted to board the outbound bus.

"You'll need orders from the Chief Engineer's office," the driver said.

Benda went to Rohan.

"Am I a prisoner?" he demanded with his characteristic directness.

"An embarassing situation," the suave Rohan admitted, very calmly and at his ease. "You see, I'm nothing like a dictator here. I have no arbitrary power. Everything runs by system, and you're a sort of exception. No one knows exactly how to classify you. Neither do I. But, I can't break a rule. That is sin."

"What rule? I want to go to New York."

"Only those of the Faith who have reached the third degree can come and go. No one can get that in less than three years."

"Then you got me in here by fraud?" Benda asked bluntly.

Rohan side-stepped gracefully.

"You know our innermost secrets now," he explained. "Do you suppose there is any hope of your embracing the Faith?"

Benda whirled on his heel and walked out.

"I'll think about it!" he said, his voice snapping with sarcasm.

Benda went back to his work in order to get his mind off the matter. He was a well-balanced man if he was anything; and he knew that nothing could be accomplished by rash words or incautious moves against Rohan and his organization. And on that day he met John Edgewater Smith.

"You here?" Benda gasped. He lost his equilibrium for a moment in consternation at the sight of his fellow-engineer.

Smith was too elated to notice Benda's mood.

"I've been here a week. This is certainly an ideal opportunity in my line of work. Even in Heaven I never expected to find such a chance."

By this time Benda had regained control of himself. He decided to say nothing to Smith for the time being.

They did not meet again for several weeks. In the meantime Benda discovered that his mail was being censored. At first he did not know that his letters, always typewritten, were copied and objectionable matter omitted, and his signature reproduced by the photo-engraving process, separately each time. But before long, several letters came back to him rubber-stamped: "Not passable. Please revise." It took Benda two days to cool down and rewrite the first letter. But outwardly no one would have ever known that there was anything amiss with him.

However, he took to leaving his work for an hour or two a day and walking in the park, to think out the matter. He didn't like it. This was about the time that it began to be a real issue as to who was the bigger man of the two, Rohan or Benda. But no signs of the issue appeared externally for many months.

John Edgewater Smith realized sooner than Benda that he couldn't get out, because, not sticking to work so closely, he had made the attempt sooner. He looked very much worried when Benda next saw him.

"What's this? Do you know about it?" he shouted as soon as he had come within hearing distance of Benda.

"What's the difference?" Benda replied casually. "Aren't you satisfied?"

Smith's face went blank.

Benda came close to him, linked arms and led him to a broad vacant lawn in the park.

"Listen!" he said softly in Smith's ear. "Don't you suppose these people[Pg 302] who lock us in and censor our mail aren't smart enough to spy on what we say to each other?"

"Our only hope," Benda continued, "is to learn all we can of what is going on here. Keep your eyes and ears open and meet me here in a week. And now come on; we've been whispering here long enough."

Oddly enough, the first clue to the puzzle they were trying to solve was supplied by Francisco, New York's former Water Commissioner. Why were they being kept prisoners in the city? There must be more reason for holding them there than the fear that information would be carried out, for none of the three engineers knew anything about the Science Community that could be of any possible consequence to outsiders. They had all stuck rigidly to their own jobs.

They met Francisco, very blue and dejected, walking in the park a couple of months later. They had been having weekly meetings, feeling that more frequent rendezvous might excite suspicion. Francisco was overjoyed to see them.

"Been trying to figure out why they want us," he said. "There is something deeper than the excuse they have made; that rot about a perfect system and no breaking of rules may be true, but it has nothing to do with us. Now, here are three of us, widely admitted as having good heads on us. We've got to solve this."

"The first fact to work on," he continued, "is that there is no real job for me here. This city has no water problem that cannot be worked out by an engineer's office clerk. Why are they holding me here, paying me a profligate salary, for a job that is a joke for a grown-up man? There's something behind it that is not apparent on the surface."

The weekly meetings of the three engineers became an established institution. Mindful that their conversation was doubtless the object of attention on the part of the ruling powers of the city through spies and concealed microphones, they were careful to discuss trivial matters most of the time, and mentioned their problem only when alone in the open spaces of the park.

After weeks of effort had produced no results, they arrived at the conclusion that they would have to do some spying themselves. The great temple, shaped like a dynamo-generator attracted their attention as the first possibility for obtaining information. Benda, during his work with telephone and television installation, found that the office of some sort of ruling council or board of directors were located there. Later he found that it was called the Science Staff. He managed to slip in several concealed microphone detectors and wire them to a private receiver on his desk, doing all the work with his own hands under the pretense of hunting for a cleverly contrived short-circuit that his subordinates had failed to find.

"They open their meeting," he said, reporting several days of listening to his comrades, "with a lot of religious stuff. They really believe they are chosen by God to perfect the earth. Their fanaticism has the Mohammedans beat forty ways. As I get it from listening in, this city is just a preliminary base from which to carry, forcibly, the gospel of Scientific Efficiency to the whole world. They have been divinely appointed to organize the earth.

"The first thing on the program is the seizure of New York City. And, it won't be long; I've heard the details of a cut-and-dried plan. When they have New York, the rest of America can be easily captured, for cities aren't as independent of each other as they used to be. Getting the rest of the world into their hands will then be merely a matter of routine; just a little time, and it will be done. Mohammed's wars weren't in it with this!"

Francisco and Smith stared at him aghast. These dull-faced, blue-serge[Pg 303]clad people did not look capable of it; unless possibly one noted the fiery glint in their eyes. A worldwide Crusade on a scientific basis! The idea left them weak and trembling.

"Got to learn more details before we can do anything," Benda said. "Come on; we've been whispering here long enough; they'll get suspicious." Benda's brain was now definitely pitted against this marvelous organisation.

"

I've got it!" Benda reported at a later meeting. "I pieced it together from a few hours listening. Devilish scheme!

"Can you imagine what would happen in New York in case of a break-down in water-supply, electric power, and communication? In an hour there would be a panic; in a day the city would be a hideous shambles of suffering, starvation, disease, and trampling maniacs. Dante's Inferno would be a lovely little pleasure-resort in comparison.

"Also, have you ever stopped to think how few people there are in the world who understand the handling of these vital elements of our modern civilized organization sufficiently to keep them in operation? There you have the scheme. Because they do not want to destroy the city, but merely to threaten it, they are holding the three of us. A little skilful management will eliminate all other possible men who could operate the city's machinery, except ourselves. We three will be placed in charge. A threat, perhaps a demonstration in some limited section of what horrors are possible. The city is at their mercy, and promptly surrenders.

"An alternative plan was discussed: just a little quiet violence could eliminate those who are now in charge of the city's works, and the panic and horrors would commence. But, within an hour of the city's capitulation, the three of us could have things running smoothly again. And there would be no New York; in its place would be Science Community Number Two. From it they could step on to the next city."

The other two stared at him. There was only one comment.

"They seem to be sure that they could depend on us," Smith said.

"They may be correct," Benda replied. "Would you stand by and see people perish if a turn of your hand could save them? You would for the moment, forget the issue between the old order and the new religion."

They separated, horrified by the ghastly simplicity of the plan.

Just following this, Benda received the telegram announcing the prospective visit of his lifelong friend, Dr. Hagstrom. He took it at once to Rohan.

"Will my friend be permitted to depart again, if he once gets in here?" he demanded with his customary directness.

"It depends on you," Rohan replied blandly. "We want your friend to see our Community, and to go away and carry with him the nicest possible reports and descriptions of it to the world. I wonder, do I make myself clear?"

"That means I've got to feed him taffy while he's here?" Benda asked gruffly.

"You choose to put it indelicately. He is to see and hear only such things about the Science Community as will please the world and impress it favorably. I am sure you will understand that under no other circumstances will he be permitted to leave here."

Benda turned around abruptly and walked out without a word.

"Just a moment," Rohan called after him. "I am sure you appreciate the fact that every precaution will be taken to hear the least word that you say to him during his stay here? You are watched only perfunctorily now. While he is here you will be kept[Pg 304] track of carefully, and there will be three methods of checking everything you do or say. I am sure you do not underestimate our caution in this matter."

Benda spent the days intervening between then and the arrival of his friend Hagstrom, closed up in his office, in intense study. He figured things on pieces of paper, committed them to memory, and scrupulously burned the paper. Then he wandered about the park and plucked at leaves and twigs.

(Related by Peter Hagstrom, Ph.D.)

Benda conducted me personally to a room very much like an ordinary hotel room. He was glad to see me. I could tell that from his grip of welcome, from his pleased face, from the warmth in his voice, from the eager way in which he hovered around me. I sat down on a bed and he on a chair.

"Now tell me all about it," I said.

The room was very still, and in its privacy, following Benda's demonstrative welcome, I expected some confidential revelations. Therefore I was astonished.

"There isn't much to tell," he said gaily. "My work is congenial, fascinating, and there's enough of it to keep me out of mischief. The pay is good, and the life pleasant and easy."

I didn't know what to say for a moment. I had come there with my mind made up that there was something suspicious afoot. But he seemed thoroughly happy and satisfied.

"I'll admit that I treated you a little shabbily in this matter of letters," he continued. "I suppose it is because I've had a lot of new and interesting problems on my mind, and it's been hard to get my mind down to writing letters. But I've got a good start on my job, and I'll promise to reform."

I was at a loss to pursue that subject any further.

"Have you seen Smith and Francisco?" I asked.

He nodded.

"How do they like it?"

"Both are enthusiastic about the wonderful opportunities in their respective fields. It's a fact: no engineer has ever before had such resources to work with, on such a vast scale, and with such a free hand. We're laying the framework for a city of ten millions, all thoroughly systematized and efficient. There is no city in the world like it; it's an engineer's dream of Utopia."

I was almost convinced. There was only the tiniest of lurking suspicions that all was not well, but it was not powerful enough to stimulate me to say anything. But I did determine to keep my eyes open.

I might as well admit in advance that from that moment to the time when I left the Science Community four days later, I saw nothing to confirm my suspicions. I met Smith and Francisco at dinner and the four of us occupied a table to ourselves in a vast dining hall, and no one paid for the meal nor for subsequent ones. They also seemed content, and talked enthusiastically of their work.

I was shown over the city, through its neat, efficient streets, through its comfortable dormitories each housing hundreds of families as luxuriously as any modern hotel, through its marvelous factories where production had passed the stage of labor and had assumed the condition of a devoted act of worship. These factory workers were not toiling: they were worshipping their God, of Whom each machine was a part. Touching their machine was touching their God. This machinery, while involving no new principles, was developed and coordinated to a degree that exceeded anything I had ever seen anywhere else.

I saw the famous Science Temple in[Pg 305] the shape of a huge dynamo-generator, with its interior decorations, paintings, carvings, frescoes, and pillars, all worked out on the motive of machinery; with its constant streams of worshippers in blue serge, performing their conventional rites and saying their prayer formulas at altars in the forms of lathes, microscopes, motors, and electron-tubes.

"You haven't become a Science Communist yourself?" I bantered Benda.

There was a metallic ring in the laugh he gave.

"They'd like to have me!" was all he said.

I was rather surprised at the emptiness of the large and well-kept park to which Benda took me. It was beautifully landscaped, but only a few scattering people were there, lost in its vast reaches.

"These people seem to have no need of recreation," Benda said. "They do not come here much. But I confess that I need air and relaxation, even if only for short snatches. I've been too busy to get away for long at a time, but this park has helped me keep my balance—I'm here every day for at least a few minutes."

"Beautiful place," I remarked. "A lot of strange trees and plants I never saw before—"

"Oh, mostly tropical forms, common enough in their own habitats. They have steam pipes under the ground to grow them. I've been trying to learn something about them. Fancy me studying natural history! I've never cared for it, but here, where there is no such thing as recreation, I have become intensely interested in it as a hobby. I find it very much of a rest to study these plants and bugs."

"Why don't you run up to New York for a few days?"

"Oh, the time will come for that. In the meanwhile, I've got an idea all of a sudden. Speaking of New York, will you do me a little service? Even though you might think it silly?"

"I'll do anything I can," I began, eager to be of help to him.

"It has been somewhat of a torture to me," Benda continued, "to find so many of these forms which I am unable to identify. I like to be scientific, even in my play, and reference books on plants and insects are scarce here. Now, if you would carry back a few specimens for me, and ask some of the botany and zoology people to send me their names—"

"Fine!" I exclaimed. "I've got a good-sized pocket notebook I can carry them in."

"Well then, please put them in the order in which I hand them to you, and send me the names by number. I am pretty thoroughly familiar with them, and if you will keep them in order, there is no need for me to keep a list. The first is a blade of this queer grass."

I filed the grass blade between the first two pages of my book.

"The next is this unusual-looking pinnate leaf." He tore off a dry leaflet and handed me a stem with three leaflets irregularly disposed of it.

"Now leave a blank page in your book. That will help me remember the order in which they come."

Next came a flat insect, which, strangely enough, had two legs missing on one side. However, Benda was moving so fast that I had to put it away without comment. He kept darting about and handing me twigs of leaves, little sticks, pieces of bark, insects, not seeming to care much whether they were complete or not; grass-blades, several dagger-shaped locust-thorns, cross-sections of curious fruits, moving so rapidly that in a few moments my notebook bulged widely, and I had to warn him that its hundred leaves were almost filled.

"Well, that ought to be enough," he said with a sigh after his lively exertion. "You don't know how I'll appreciate your indulging my foolish little whim."

"Say!" I exclaimed. "Ask some[Pg 306]thing of me. This it nothing. I'll take it right over to the Botany Department, and in a few days you ought to have a list of names fit for a Bolshevik."

"One important caution," he said. "If you disturb their order in the book, or even the position on the page, the names you send me will mean nothing to me. Not that it will be any great loss," he added whimsically. "I suppose I've become a sort of fan on this, like the business men who claim that their office work interferes with their golf."

We walked leisurely back toward the big dormitory. It was while we were crossing a street that Benda stumbled, and, to dodge a passing truck, had to catch my arm, and fell against me. I heard his soft voice whisper in my ear:

"Get out of this town as soon as you can!"

I looked at him in startled amazement, but he was walking along, shaking himself from his stumble, and looking up and down the street for passing trucks.

"As I was saying," he said in a matter-of-fact voice, "we expect to reach the one-and-one-quarter million mark this month. I never saw a place grow so fast."

I felt a great leap of sudden understanding. For a moment my muscles tightened, but I took my cue.

"Remarkable place," I said calmly; "one reads a lot of half-truths about it. Too bad I can't stay any longer."

"Sorry you have to leave," he said, in exactly the right tone of voice. "But you can come again."

How thankful I was for the forty years of playing and working together that had accustomed us to that sort of team-work! Unconsciously we responded to one another's cues. Once our ability to "play together" had saved my life. It was when we were in college and were out on a cross-country hike together; Benda suddenly caught my hand and swung it upward. I recognized the gesture; we were cheerleaders and worked together at football games, and we had one stunt in which we swung our hands over our heads, jumped about three feet, and let out a whoop. This was the "stunt" that he started out there in the country, where we were by ourselves. Automatically, without thinking, I swung my arms and leaped with him and yelled. Only later did I notice the rattlesnake over which I had jumped. I had not seen that I was about to walk right into it, and he had noticed it too late to explain. A flash of genius suggested the cheering stunt to him.

"Communication is a science!" he had said, and that was all the comment there was on the incident.

So now, I followed my cue, without knowing why, nor what it was all about, but confident that I should soon find out. By noon I was on the bus, on my way through the pass, to meet the vehicle from Washington. As the bus swung along, a number of things kept jumbling through my mind: Benda's effusive glee at seeing me, and his sudden turning and bundling me off in a nervous hurry without a word of explanation; his lined and worried face and yet his insistence on the joys of his work in The Science Community; his obvious desire to be hospitable and play the good host, and yet his evasiveness and unwillingness to chat intimately and discuss important thing as he used to. Finally, that notebook full of odd specimens bulging in my pocket. And the memory of his words as he shook hands with me when I was stepping into the bus:

"Long live the science of communication!" he had said. Otherwise, he was rather glum and silent.

I took out the book of specimens and looked at it. His caution not to disturb the order and position of things rang in my ears. The Science of Communication! Two and two were beginning to make four in my mind. All the way on the train from Wash[Pg 307]ington to New York I could hardly, keep my hands off the book. I had definitely abandoned the idea of hunting up botanists and zoologists at Columbia. Benda was not interested in the names of these things. That book meant something else. Some message. The Science of Communication!

That suddenly explained all the contradictions in his behavior. He was being closely watched. Any attempt to tell me the things he wanted to say would be promptly recognized. He had succeeded brilliantly in getting a message to me. Now, my part was to read it! I felt a sudden sinking within me. That book full of leaves, bugs, and sticks? How could I make anything out of it?

"There's the Secret Service," I thought. "They are skilled in reading hidden messages. It must be an important one, worthy of the efforts of the Secret Service, or he would not have been at such pains to get it to me—

"But no. The Secret Service is skilled at reading hidden messages, but not as skilled as I am in reading my friend's mind. Knowing Benda, his clear intellect, his logical methods, will be of more service in solving this than all the experts of the Secret Service."

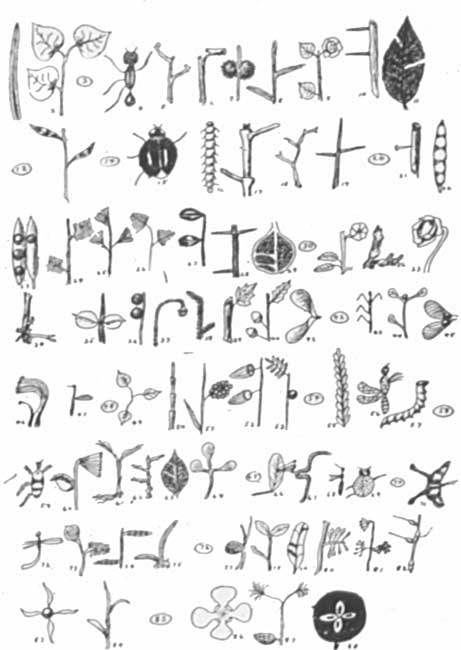

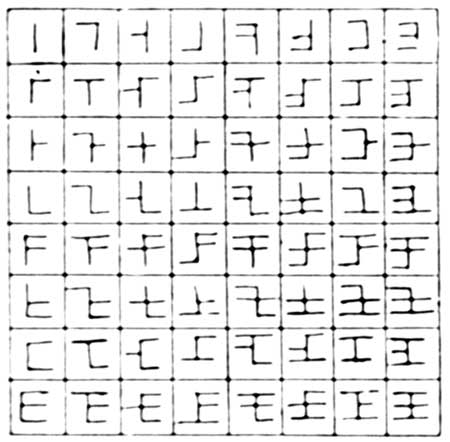

I barely stopped to eat dinner when I reached home. I hurried to the laboratory building, and laid out the specimens on white sheets of paper, meticulously preserving order, position, and spacing. To be on the safe side I had them photographed, asking the photographer to vary the scale of his pictures so that all of the final figures would be approximately the same size. Plate I. shows what I had.

I was all a-tremble when the mounted photographs were handed to me. The first thing I did was to number the specimens, giving each blank space also its consecutive number. Certainly no one could imagine a more meaningless jumble of twigs, leaves, berries, and bugs. How could I read any message out of that?

Yet I had no doubt that the message concerned something of far more importance than Benda's own safety. He had moved in this matter with astonishing skill and breathless caution; yet I knew him to be reckless to the extreme where only his own skill was concerned. I couldn't even imagine his going to this elaborate risk merely on account of Smith and Francisco. Something bigger must be involved.

I stared at the rows of specimens.

"Communication is a science!" Benda had said, and it came back to me as I studied the bent worms and the beetles with two legs missing. I was confident that the solution would be simple. Once the key idea occurred to me I knew I should find the whole thing astonishingly direct and systematic. For a moment I tried to attach some sort of heiroglyphic significance to the specimen forms; in the writing of the American Indians, a wavy line meant water, an inverted V meant a wigwam. But, I discarded that idea in a moment. Benda's mind did not work along the paths of symbolism. It would have to be something mathematical, rigidly logical, leaving no room for guess-work.

No sooner had the key-idea occurred to me than the basic conception underlying all these rows of twigs and bugs suddenly flashed into clear meaning before me. The simplicity of it took my breath away.

"I knew it!" I said aloud, though I was alone. "Very simple."

I was prepared for the fact that each one of the specimens represented a letter of the alphabet. If nothing else, their number indicated that. Now I could see, so clearly that the photographs shouted at me, that each specimen consisted of an upright stem, and from this middle stem projected side-arms to the right and to the left, and in various vertical locations on each side.

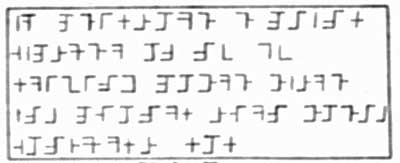

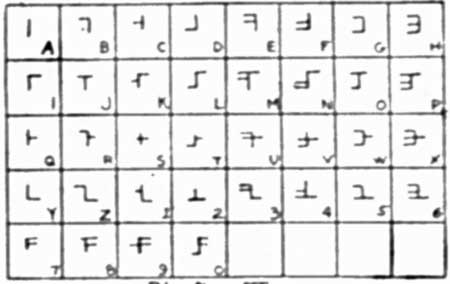

The middle upright stem contained[Pg 308] these side-arms in various numbers and combinations. In five minutes I had a copy of the message, translated into its fundamental characters, as shown on Plate II.

Plate I

Plate I

The first grass-blade was the simple, upright stem; the second, three leaflets on their stem, represented the upright portion with two arms to the left at the top and middle, and one arm to the right at the top; and so on.

That brought the message down to the simple and straightforward matter of a substitution cipher. I was confident that Benda had no object in introducing any complications that could possibly be avoided, as his sole purpose was to get to me the most readable message without getting caught at it. I recollected now how cautious he had been to hand me no paper, and how openly and obviously he had dropped each specimen into my book; because he knew someone was watching him and expecting him to slip in a message. He had, as I could see now in the retrospect, been conspicuously careful that nothing suspicious should pass from his hands to mine.

Plate II

Plate II

Substitution ciphers are easy to solve, especially for those having some experience. The method can be found in Edgar Allen Poe's "Gold Bug" and in a host of its imitators. A Secret Service cipher man could have read it in an hour. But I knew my friend's mind well enough to find a short-cut. I knew just how he would go about devising such a cipher, in fact, how ninety-nine persons out of a hundred with a scientific education would do it.

If we begin adding horizontal arms to the middle stem, from top to bottom and from left to right, the possible characters can be worked out by the system shown on Plate III.

Plate III

Plate III

It is most logical to suppose that Benda would begin with the first sign and substitute the letters of the alphabet in order. That would give us the cipher code shown on Plate IV.

It was all very quick work, just as I had anticipated, once the key-idea had occurred to me. The ease and speed of[Pg 309] my method far exceeded that of Poe's method, but, of course, was applicable only to this particular case. Substituting letters for signs out of my diagram, I got the following message:

AM PRISONER R PLANS CAPTURE OF N Y BY SEIZING POWER WATER AND PHONES THEN WORLD CONQUEST S O S

Plate IV

Plate IV

(By Peter Hagstrom, M.D.)

My solution of the message practically ends the story. Events followed each other from then on like bullets from a machine-gun. A wild drive in a taxicab brought me to the door of Mayor Anderson at ten o'clock that night. I told him the story and showed him my photographs.

Following that I spent many hours telling my story to and consulting with officers in the War Department. Next afternoon, photographic maps of the Science Community and its environs, brought by airplanes during the forenoon, were spread on desks before us. A colonel of marines and a colonel of aviation sketched plans in notebooks. After dark I sat in a transport plane with muffled exhaust and propellers, slipping through the air as silently as a hawk. About us were a dozen bombing planes, and about fifty transports, carrying a battalion of marines.

I am not an adventure-loving man. Though a cordon of husky marines about me was a protection against any possible danger, yet, stealing along through that wild valley in the Virginia mountains toward the dark masses of that fanatic city, the silent progress of the long, dark line through the night, their mysterious disappearance, one by one, as we neared the city, the creepy, hair-raising journey through the dark streets—I shall never forget for the rest of my life the sinking feeling in my abdomen and the throbbing in my head. But I wanted to be there, for Benda was my lifelong friend.

I guided them to Rohan's rooms, and saw a dozen dark forms slip in, one by one. Then we went on to the dormitory where Benda lived. Benda answered our hammering at his door in his pajamas. He took in the Captain's automatic, and the bayonets behind me, at a glance.

"Good boy, Hagstrom!" he said. "I knew you'd do it. There wasn't much time left. I got my instructions about handling the New York telephone system to-day."

As we came out into the street. I saw Rohan handcuffed to two big marines, and rows of bayonets gleaming in the darkness down the streets. Every few moments a bright flare shot out from the planes in the sky, until a squad located the power-house and turned on all the lights they could find.

Have you ever stood on the seashore, with the breakers rolling at your feet, and imagined what the scene would be like if the ocean water were gone? I have had a vision of that many times. Standing on the Atlantic Coast, gazing out toward Spain, I can envisage myself, not down at the sea-level, but upon the brink of a height. Spain and the coast of Europe, off there upon another height.

And the depths between? Unreal landscape! Mysterious realm which now we call the bottom of the sea! Worn and rounded crags; bloated mud-plains; noisome reaches of ooze which once[Pg 310] were the cold and dark and silent ocean floor, caked and drying in the sun. And off to the south the little fairy mountain tops of the West Indies rearing their verdured crowns aloft.

"Look around, Chief. See where I am?"

"Look around, Chief. See where I am?"

If the ocean water were gone! Can you picture it? A new world, greater in area than all the land we now have. They would call the former sea-level the zero-height, perhaps. The depths would go down as far beneath it as Mount Everest towers above it. Aeroplanes would fly down into them.

And I can imagine the settlement of these vast new realms: New little nations being created, born of man's indomitable will to conquer every adverse condition of inhospitable nature.

A novel setting for a story of adventure. It seems so to me. Can you say that the oceans will never drain of their water? That an earthquake will not open a rift—some day in the future—and lower the water into subterranean caverns? The volume of water of all the oceans is no more to the volume of the earth than a tissue paper wrapping on an orange.

Is it too great a fantasy? Why, reading the facts of what happened in 1929, it is already prognosticated. The fishing banks off the Coast of Newfoundland have suddenly sunk. Cable ships repairing a broken cable, snapped by the earthquake of November 18th, 1929, report that for distances of a hundred miles on the Grand Banks the cables have disappeared into unfathomable depths. And before the subterranean cataclysm, they were within six hundred feet of the surface. And all the bottom of that section of the North Atlantic seems to have caved in. Ten thousand square miles dropped out of the bottom of the ocean! Fact, not fancy.

And so let us enlarge the picture. Let us create the Lowlands—twenty thousand feet below the zero-height—the setting for a tale of adventure. The romance of the mist-shrouded deeps. And the romance of little Jetta.

I was twenty-five years of age that May evening of 2020 when they sent me south into the Lowlands. I had been in the National Detective Service Bureau, and then was transferred to the Customs Department, Atlantic Lowlands Branch. I went alone; it was best, my commander thought. An assignment needing diplomacy rather than a show of force.

It was 9 P. M. when I catapulted from the little stage of Long Island airport. A fair, moonlit evening—a moon just beyond the full, rising to pale the eastern stars. I climbed about a thousand feet, swung over the headlands of the Hook, and, keeping in the thousand-foot local lane, took my course.

My destination lay some thirteen hundred miles southeast of Great New York. I could do a good normal three-ninety in this fleet little Wasp, especially if I kept in the rarer air-pres[Pg 311]sures over the zero-height. The thousand-foot lane had a southward drift, this night. I was making now well over four hundred; I would reach Nareda soon after midnight.

The Continental Shelf slid beneath me, dropping away as my course took me further from the Highland borders. The Lowlands lay patched with inky shadows and splashes of moonlight. Domes with upstanding, rounded heads; plateaus of naked black rock, ten thousand feet below the zero-height; trenches, like valleys, ridged and pitted, naked in places like a pockmarked lunar landscape. Or again, a pall of black mist would shroud it all, dark curtain of sluggish cloud with moonlight tinging its edges pallid green.

To my left, eastward toward the great basin of the mid-Atlantic Lowlands, there was always a steady downward slope. To the right, it came up over the continental shelf to the Highlands of the United States.

There was often water to be seen in these Lowlands. A spring-fed lake far down in a caldron pit, spilling into a trench; low-lying, land-locked little seas; cañons, some of them dry, others filled with tumultuous flowing water. Or great gashes with water sluggishly flowing, or standing with a heavy slime, and a pall of uprising vapor in the heat of the night.

At 37°N. and 70°W., I passed over the newly named Atlas Sea. A lake of water here, more than a hundred miles in extent. Its surface lay fifteen thousand feet below the zero-height; its depth in places was a full three thousand. It was clear of mist to-night. The moonlight shimmered on its rippled surface, like pictures my father had often shown me of the former oceans.

I passed, a little later, well to the westward of the verdured mountain top of the Bermudas.

There was nothing of this flight novel to me. I had frequently flown over the Lowlands; I had descended into them many times. But never upon such a mission as was taking me there now.

I was headed for Nareda, capital village of the tiny Lowland Republic of Nareda, which only five years ago came into national being as a protectorate of the United States. Its territory lies just north of the mountain Highlands of Haiti, Santo Domingo and Porto Rico. A few hundred miles of tumbled Lowlands, embracing the turgid Nares Sea, whose bottom is the lowest point of all the Western Hemisphere—some thirty thousand feet below the zero-height.

The village of Nareda is far down indeed. I had never been there. My charts showed it on the southern border of the Nares Sea, at minus twenty thousand feet, with the Mona Valley behind it like a gash in the steep upward slopes to the Highlands of Porto Rico and Haiti.

Nareda has a mixed population of typical Lowland adventures, among which the hardy Dutch predominate; and Holland and the United States have combined their influence in the World Court to give it national identity.

And out of this had arisen my mission now. Mercury—the quicksilver of commerce—so recently come to tremendous value through its universal use in the new antiseptics which bid fair to check all human disease—was being produced in Nareda. The import duty into the United States was being paid openly enough. But nevertheless Hanley's agents believed that smuggling was taking place.

It was to investigate this condition that Hanley was sending me. I had introduction to the Nareda government officials. I was to consult with Hanley by ether-phone in seeking the hidden source of the contraband quicksilver, but, in the main, to use my own judgment.

A mission of diplomacy. I had no mind to pry openly among the people[Pg 312] of these Lowland depths, looking for smugglers. I might, indeed, find them too unexpectedly! Over-curious strangers are not welcomed by the Lowlanders. Many have gone into the depths and have never returned....

I was above the Nares Sea, by midnight. I was still flying a thousand feet over the zero-height. Twenty-one thousand feet below me lay the black expanse of water. The moon had climbed well toward the zenith, now. Its silver shafts penetrated the hanging mist-stratas. The surface of the Nares Sea was visible—dark and sullen looking.

I shifted the angles of incidence of the wings, re-set my propeller angles and made the necessary carburetor adjustments, switching on the supercharger which would supply air at normal zero-height pressure to the carburetors throughout my descent.

I swung over Nareda. The lights of the little village, far down, dwarfed by distance, showed like bleary, winking eyes through the mists. The jagged recesses of the Mona valley were dark with shadow. The Nares Sea lay like some black monster asleep, and slowly, heavily panting. Moonlight was over me, with stars and fleecy white clouds. Calm, placid, atmospheric night was up here. But beneath, it all seemed so mysterious, fantastic, sinister.

My heart was pounding as I put the Wasp into a spiral and forced my way down.

With heavy, sluggish engines I panted down and came to rest in the dull yellow glow of the field lights. A new world here. The field was flat, caked ooze, cracked and hardened. It sloped upward from the shore toward where, a quarter of a mile away, I could see the dull lights of the settlement, blurred by the gathered night vapors.[Pg 313]

The field operator shut off his permission signal and came forward. He was a squat, heavy-set fellow in wide trousers and soiled white shirt flung open at his thick throat. The sweat streamed from his forehead. This oppressive heat! I had discarded my flying garb in the descent. I wore a shirt, knee-length pants, with hose and wide-soled shoes of the newly fashioned Lowland design. What few weapons I dared carry were carefully concealed. No alien could enter Nareda bearing anything resembling a lethal weapon.

My wide, thick-soled shoes did not look suspicious for one who planned much walking on the caked Lowland ooze. But those fat soles were cleverly fashioned to hide a long, keen knife-blade, like a dirk. I could lift a foot and get the knife out of its hidden compartment with fair speed. This I had in one shoe.

In the other, was the small mechanism of a radio safety recorder and image finder, with its attendant individual audiophone transmitter and receiver. A miracle of smallness, these tiny contrivances. With batteries, wires and grids, the whole device could lay in the palm of one's hand. Once past this field inspection I would rig it for use under my shirt, strapped around my chest. And I had some colored magnesium flares.

The field operator came panting.

"Who are you?"

"Philip Grant. From Great New York." I showed him my name etched on my forearm. He and his fellows searched me, but I got by.

"You have no documents?"

"No."

My letter to the President of Nareda was written with invisible ink upon the fabric of my shirt. If he had heated it to a temperature of 180°F. or so, and blown the fumes of hydrochloric acid upon it, the writing would have come out plain enough.

I said, "You'll house and care for my machine?"[Pg 314]

They would care for it. They told me the price—swindlingly exorbitant for the unwary traveller who might wander down here.

"All correct," I said cheerfully. "And half that much more for you and your men if you give me good service. Where can I have a room and meals?"

"Spawn," said the operator. "He is the best. Fat-bellied from his own good cooking. Take him there, Hugo."

I had a gold coin instantly ready; and with a few additional directions regarding my flyer, I started off.

It had been hot and oppressive standing in the field; it was infinitely worse climbing the mud-slope into the village; but my carrier, trudging in advance of me along the dark, winding path up the slope, shouldered my bag and seemed not to notice the effort. We passed occasional tube-lights strung on poles. They illumined the heavy rounded crags. A tumbled region, this slope which once was the ocean floor twenty thousand feet below the surface. Rifts were here like gulleys; little buttes reared their rounded, dome heads. And there were caves and crevices in which deep sea fish once had lurked.

For ten minutes or so we climbed. It was past the midnight hour; the village was asleep. We entered its outposts. The houses were small structures of clay. In the gloom they looked like drab little beehives set in unplanned groups, with paths for streets wandering between them.

Then we came to a more prosperous neighborhood. The street widened and straightened. The clay houses, still with rounded dome like tops, stood back from the road, with wooden front fences, and gardens and shrubbery. The windows and doors were like round finger-holes plugged in the clay by a giant hand. Occasionally the windows, dimly lighted, stared like sleeping giant eyes.

There were flowers in all the more pretentious private gardens. Their perfume, hanging in the heavy night air, lay on the village, making one forget the over-curtain of stenching mist. Down by the shore of the Nares Sea, this world of the depths had seemed darkly sinister. But in the village now, I felt it less ominous. The scent of the flowers, the street lined in one place by arching giant fronds drowsing and nodding overhead—there seemed a strange exotic romance to it. The sultry air might almost have been sensuous.

"Much further, Hugo?"

"No. We are here."

He turned abruptly into a gateway, led me through a garden and to the doorway of a large, rambling, one-story building. The news of my coming had preceded me. A front room was lighted; my host was waiting.

Hugo set down my bag, accepted another gold coin; and with a queer sidelong smile, the incentive for which I had not the slightest idea, he vanished. I fronted my host, this Jacob Spawn. Strange fate that should have led me to Spawn! And to little Jetta!

Spawn was a fat-bellied Dutchman, as the field attendant had said. A fellow of perhaps fifty-five, with sparse gray hair and a heavy-jowled, smooth-shaved face from which his small eyes peered stolidly at me. He laid aside a huge, old-fashioned calabash pipe and offered a pudgy hand.

"Welcome, young man, to Nareda. Seldom do we see strangers."

The meal which he presently cooked and served me himself was lavishly done. He spoke good English, but slowly, heavily, with the guttural intonation of his race. He sat across the table from me, puffing his pipe while I ate.

"What brings you here, young lad? A week, you say?"

"Or more. I don't know. I'm looking for oil. There should be petroleum beneath these rocks."

For an hour I avoided his prying questions. His little eyes roved me,[Pg 315] and I knew he was no fool, this Dutchman, for all his heavy, stolid look.

We remained in his kitchen. Save for its mud walls, its concave, dome-roof, it might have been a cookery of the Highlands. There was a table with its tube-light; the chairs; his electron stove; his orderly rows of pots and pans and dishes on a broad shelf.

I recall that it seemed to me a woman's hand must be here. But I saw no woman. No one, indeed, beside Spawn himself seemed to live here. He was reticent of his own business, however much he wanted to pry into mine.

I had felt convinced that we were alone. But suddenly I realized it was not so. The kitchen adjoined an interior back-garden. I could see it through the opened door oval—a dim space of flowers; a little path to a pergola; an adobe fountain. It was a sort of Spanish patio out there, partially enclosed by the wings of the house. Moonlight was struggling into it. And, as I gazed idly, I thought I saw a figure lurking. Someone watching us.

Was it a boy, observing us from the shadowed moonlit garden? I thought so. A slight, half grown boy. I saw his figure—in short ragged trousers and a shirt-blouse—made visible in a patch of moonlight as he moved away and entered the dark opposite wing of the house.

I did not see the boy's figure again; and presently I suggested that I retire. Spawn had already shown me my bedroom. It was in another wing of the house. It had a window facing the front; and a window and door back to this same patio. And a door to the house corridor.

"Sleep well, Meester Grant." My bag was here on the table under an electrolier. "Shall I call you?"

"Yes," I said. "Early."

He lingered a moment. I was opening my bag. I flung it wide under his gaze.

"Well, good night. I shall be very comfortable, thanks."

"Good night," he said.

He went out the patio door. I watched his figure cross the moonlit path and enter the kitchen. The noise of his puttering there sounded for a time. Then the light went out and the house and garden fell into silence.

I closed my doors. They sealed on the inside, and I fastened them securely. Then I fastened the transparent window panes. I did not undress, but lay on the bed in the dark. I was tired; I realized it now. But sleep would not come.

I am no believer in occultism, but there are premonitions which one cannot deny. It seemed now as I lay there in the dark that I had every reason to be perturbed, yet I could not think why. Perhaps it was because I had been lying to this innkeeper stoutly for an hour past, and whether he believed me or not for the life of me I could not now determine.

I sat up on the bed, presently, and adjusted the wires and diaphragms of the ether-wave mechanism. When in place it was all concealed under my shirt. As I switched it on, the electrodes against my flesh tingled a little. But it was absolutely soundless, and one gets used to the tingle. I decided to call Hanley.

The New York wave-sorter handled me promptly, but Hanley's office was dead.

As I sat there in the darkness, annoyed at this, a slight noise forced itself on me. A scratching—a tap—something outside my window.

Spawn, come back to peer in at me?

I slipped noiselessly from the bed. The sound had come from the window which faced the patio. The room, over by the bed, was wholly dark. The moonlight outside showed the patio window as a dimly illumined oval.

For a moment I crouched on the floor by the bed. No sound. The silence of the Lowlands is as heavy and oppressive as its air. I felt as though my heart were audible.[Pg 316]

I lifted my foot; extracted my dirk. It opened into a very businesslike steel blade of a good twelve-inch length. I bared the blade. The click of it leaving the flat, hollow handle sounded loud in the stillness of the room.

A moment. Then it seemed that outside my window a shadow had moved. I crept along the floor. Rose up suddenly at the window.

And stared at a face peering in at me. A small face, framed by short, clustering, dark curls.

A girl!

She drew back from the window like a startled fawn; timorous, yet curious, too, for she ran only a few steps, then turned and stood peering. The moonlight slanted over the western roof of the building and fell on her. A slight, boyish figure in short, tattered trousers and a boy's shirt, open at her slim, rounded throat. The moonlight gleamed on the white shirt fabric to show it torn and ragged. Her arms were upraised; her head, with clustering, flying dark curls, was tilted as though listening for a sound from me. A shy, wild creature. Drawn to my window; tapping to awaken me, then frightened at what she had done.

I opened the garden door. She did not move. I thought she would run, but she did not. The moonlight was on me as I stood there. I was conscious of its etching me with its silver sheen. And twenty feet from me this girl stood and gazed, with startled eyes and parted lips—and white limbs trembling like a frightened animal.

The patio was very silent. The heavy arching fronds stirred slightly with a vague night breeze; the moonlight threw a lacy dark pattern of them on the gray stone path. The fountain bowl gleamed white in the moonlight behind the girl, and in the silence I could hear the low splashing of the water.

A magic moment. Unforgettable. It comes to some of us just once, but to all of us it comes. I stood with its spell upon me. Then I heard my voice, tense but softly raised.

"Who are you?"

It frightened her. She retreated until the fountain was between us. And as I took a step forward, she retreated further, noiseless, with her bare feet treading the smooth stones the path.

I ran and caught her at the doorway of the flowered pergola. She stood trembling as I seized her arms. But the timorous smile remained, and her eyes, upraised to mine, glowed with misty starlight.

"Who are you?"

This time she answered me. "I am called Jetta."

It seemed that from her white forearm within my grasp a magic current swept from her to me and back again. We humans, for all our clamoring, boasting intellectuality, are no more than puppets in Nature's hands.

"Are you Spawn's daughter?"

"Yes."

"I saw you a while ago, when I was having my meal."

"Yes—I was watching you."

"I thought you were a boy."

"Yes. My father told me to keep away. I wanted to meet you, so I came to wake you up."

"He may be watching us now."

"No. He is sleeping. Listen—you can hear him snore."

I could, indeed. The silence of the garden was broken now by a distant, choking snore.

We both laughed. She sat on the little mossy seat in the pergola doorway And on the side away from the snore. (I had the wit to be sure of that.)

"I wanted to meet you," she repeated. "Was it too bold?"

I think that what we said sitting there with the slanting moonlight on us, could not have amounted to[Pg 317] much. Yet for us, it was so important! Vital. Building memories which I knew—and I think that she knew, even then—we would never forget.

"I will be here a week, Jetta."

"I want—I want very much to know you. I want you to tell me about the world of the Highlands. I have a few books. I can't read very well, but I can look at the pictures."

"Oh, I see—"

"A traveler gave them to me. I've got them hidden. But he was an old man: all men seem to be old—except those in the pictures, and you, Philip."

I laughed. "Well, that's too bad. I'm mighty glad I'm young."

Ah, in that moment, with blessed youth surging in my veins, I was glad indeed!

"Young. I don't remember ever seeing anyone like you. The man I am to marry is not like you. He is old, like father—"

I drew back from her, startled.

"Marry?"

"Yes. When I am seventeen. The law of Nareda—your Highland law, too, father says—will not let a girl be married until she is that age. In a month I am seventeen."

"Oh!" And I stammered, "But why are you going to marry?"

"Because father tells me to. And then I shall have fine clothes: it is promised me. And go to live in the Highlands, perhaps. And see things; and be a woman, not a ragged boy forbidden to show myself; and—"

I was barely touching her. It seemed as though something—some vision of happiness which had been given me—were fading, were being snatched away. I was conscious of my hand moving to touch hers.

"Why do you marry—unless you're in love? Are you?"

Her gaze like a child came up to meet mine. "I never thought much about that. I have tried not to. It frightened me—until to-night."

She pushed me gently away. "Don't. Let's not talk of him. I'd rather not."

"But why are you dressed as a boy?"

I gazed at her slim but rounded figure in tattered boy's garb—but the woman's lines were unmistakable. And her face, with clustering curls. Gentle girlhood. A face of dark, wild beauty.