Front Cover.

Front Cover.

Title: Out-of-Doors in the Holy Land: Impressions of Travel in Body and Spirit

Author: Henry Van Dyke

Release date: July 4, 2009 [eBook #29314]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Marius Borror, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Marius Borror,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

| Transcriber's note: | A few typographical errors have been corrected, mainly of inconsistent place-names. They appear in the text like this, and the explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked passage. |

Front Cover.

Front Cover.

| BOOKS BY HENRY VAN DYKE Published by CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS | |

| The Ruling Passion. Illustrated in color. | $1.50 |

| The Blue Flower. Illustrated in color. | $1.50 |

| Outdoors in the Holy Land. Illustrated in color | net $1.50 |

| Days Off. Illustrated in color. | $1.50 |

| Little Rivers. Illustrated in color. | $1.50 |

| Fisherman's Luck. Illustrated in color. | $1.50 |

| The Builders, and Other Poems. | $1.50 |

| Music, and Other Poems. | net $1.50 |

| The Toiling of Felix, and Other Poems. | $1.50 |

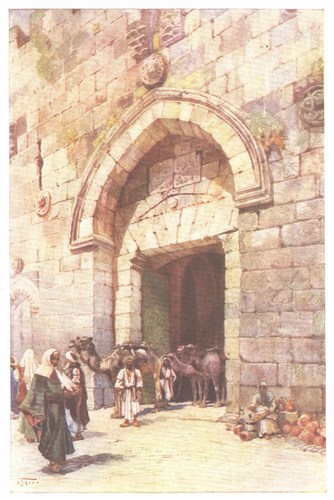

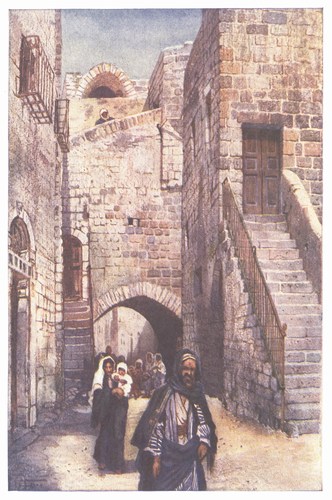

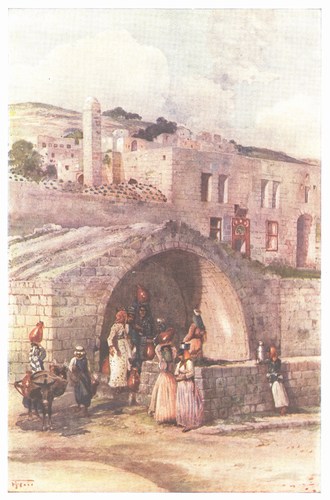

The Gate of David, Jerusalem.

The Gate of David, Jerusalem.

Copyright, 1908, by Charles Scribner's Sons

Published November, 1908

To

HOWARD CROSBY BUTLER

MASTER OF MERWICK

PROFESSOR OF ART AND ARCHÆOLOGY

WHO WAS A FRIEND TO THIS JOURNEY

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

BY HIS FRIEND

THE AUTHOR

For a long time, in the hopefulness and confidence of youth, I dreamed of going to Palestine. But that dream was denied, for want of money and leisure.

Then, for a long time, in the hardening strain of early manhood, I was afraid to go to Palestine, lest the journey should prove a disenchantment, and some of my religious beliefs be rudely shaken, perhaps destroyed. But that fear was removed by a little voyage to the gates of death, where it was made clear to me that no belief is worth keeping unless it can bear the touch of reality.

In that year of pain and sorrow, through a full surrender to the Divine Will, the hopefulness and confidence of youth came back to me. Since then it has been possible once more to wake in the morning with the feeling that the day might bring something new and wonderful and welcome, and to travel into the future with a whole and happy heart.

This is what I call growing younger; though the [page x] years increase, yet the burden of them is lessened, and the fear that life will some day lead into an empty prison-house has been cast out by the incoming of the Perfect Love.

So it came to pass that when a friend offered me, at last, the opportunity of going to Palestine if I would give him my impressions of travel for his magazine, I was glad to go. Partly because there was a piece of work,—a drama whose scene lies in Damascus and among the mountains of Samaria,—that I wanted to finish there; partly because of the expectancy that on such a journey any of the days might indeed bring something new and wonderful and welcome; but most of all because I greatly desired to live for a little while in the country of Jesus, hoping to learn more of the meaning of His life in the land where it was spent, and lost, and forever saved.

Here, then, you have the history of this little book, reader: and if it pleases you to look further into its pages, you can see for yourself how far my dreams and hopes were realised.

It is the record of a long journey in the spirit and [page xi] a short voyage in the body. If you find here impressions that are lighter, mingled with those that are deeper, that is because life itself is really woven of such contrasted threads. Even on a pilgrimage small adventures happen. Of the elders of Israel on Sinai it is written, "They saw God and did eat and drink"; and the Apostle Paul was not too much engrossed with his mission to send for the cloak and books and parchments that he left behind at Troas.

If what you read here makes you wish to go to the Holy Land, I shall be glad; and if you go in the right way, you surely will not be disappointed.

But there are two things in the book which I would not have you miss.

The first is the new conviction,—new at least to me,—that Christianity is an out-of-doors religion. From the birth in the grotto at Bethlehem (where Joseph and Mary took refuge because there was no room for them in the inn) to the crowning death on the hill of Calvary outside the city wall, all of its important events took place out-of-doors. Except the discourse in the upper chamber at Jerusalem, [page xii] all of its great words, from the sermon on the mount to the last commission to the disciples, were spoken in the open air. How shall we understand it unless we carry it under the free sky and interpret it in the companionship of nature?

The second thing that I would have you find here is the deepened sense that Jesus Himself is the great, the imperishable miracle. His words are spirit and life. His character is the revelation of the Perfect Love. This was the something new and wonderful and welcome that came to me in Palestine: a simpler, clearer, surer view of the human life of God.

HENRY VAN DYKE.

Avalon,

June 10, 1908.

| I. | Travellers' Joy | 1 |

| II. | Going up to Jerusalem | 23 |

| III. | The Gates of Zion | 45 |

| IV. | Mizpah and the Mount of Olives | 67 |

| V. | An Excursion to Bethlehem and Hebron | 83 |

| VI. | The Temple and the Sepulchre | 105 |

| VII. | Jericho and Jordan | 125 |

| VIII. | A Journey to Jerash | 151 |

| IX. | The Mountains of Samaria | 191 |

| X. | Galilee and the Lake | 217 |

| XI. | The Springs of Jordan | 259 |

| XII. | The Road to Damascus | 291 |

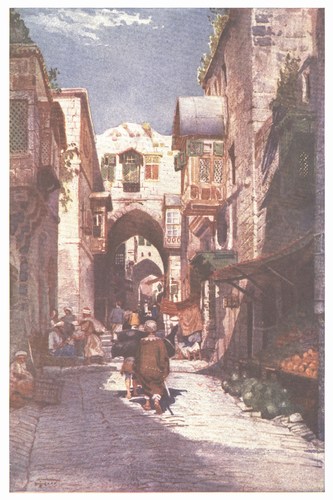

| The Gate of David, Jerusalem | Frontispiece |

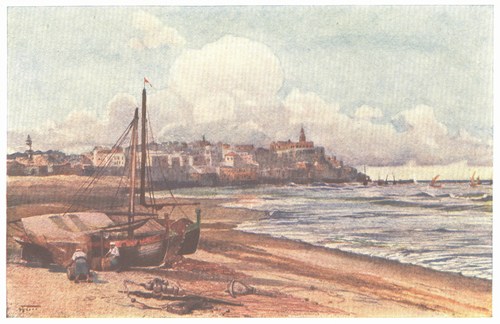

| Jaffa The port where King Solomon landed his cedar beams from Lebanon for the building of the Temple |

Facing page 14 |

| The Tall Tower of the Forty Martyrs at Ramleh | 28 |

| Street in Jerusalem | 60 |

| A Street in Bethlehem | 86 |

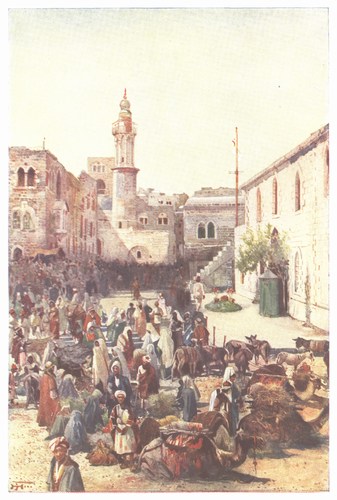

| The Market-place, Bethlehem | 90 |

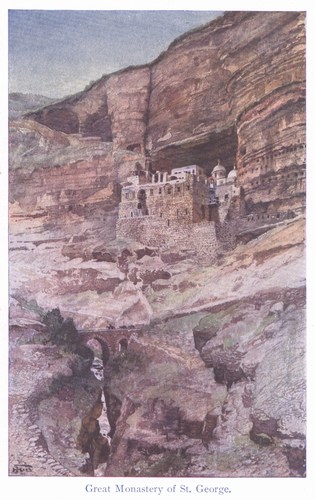

| Great Monastery of St. George | 136 |

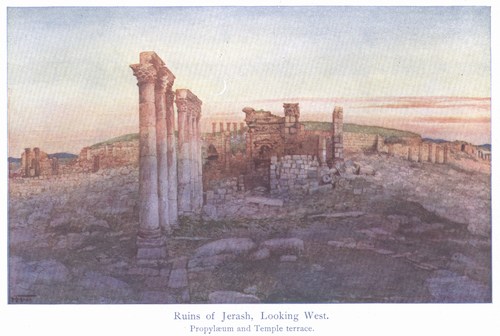

| Ruins of Jerash, Looking West Propylœum and Temple terrace |

184 |

| The Virgin's Fountain, Nazareth | 232 |

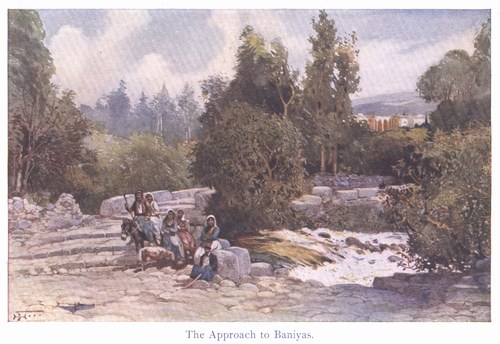

| The Approach to Bâniyâs | 276 |

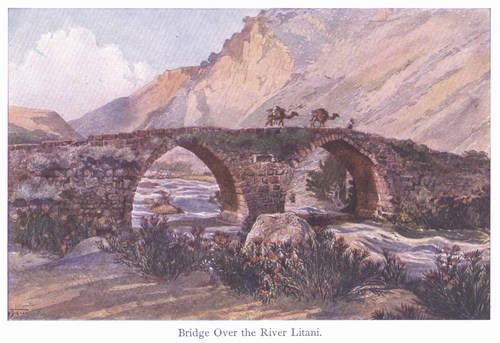

| Bridge Over the River Lîtânî | 282 |

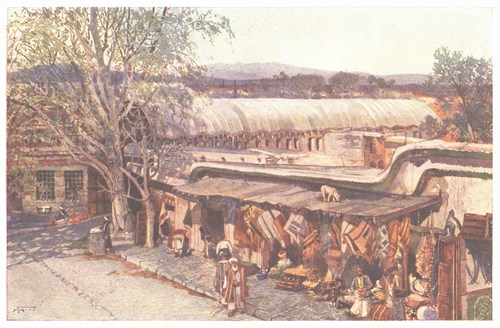

| A Small Bazaar in Damascus | 316 |

Who would not go to Palestine?

To look upon that little stage where the drama of

humanity has centred in such unforgetable scenes; to trace the rugged paths and ancient highways along which so many heroic and pathetic figures have travelled; above all, to see with the eyes as well as with the heart

"Those holy fields

Over whose acres walked those blessed feet

Which, nineteen hundred years ago, were nail'd

For our advantage on the bitter cross"—

for the sake of these things who would not travel far and endure many hardships?

It is easy to find Palestine. It lies in the south-east corner of the Mediterranean coast, where the "sea in the midst of the nations," makes a great elbow between Asia Minor and Egypt. A tiny land, about a hundred and fifty miles long and [page 4] sixty miles wide, stretching in a fourfold band from the foot of snowy Hermon and the Lebanons to the fulvous crags of Sinai: a green strip of fertile plain beside the sea, a blue strip of lofty and broken highlands, a gray-and-yellow strip of sunken river-valley, a purple strip of high mountains rolling away to the Arabian desert. There are a dozen lines of steamships to carry you thither; a score of well-equipped agencies to conduct you on what they call "a de luxe religious expedition to Palestine."

But how to find the Holy Land—ah, that is another question.

Fierce and mighty nations, hundreds of human tribes, have trampled through that coveted corner of the earth, contending for its possession: and the fury of their fighting has swept the fields as with fire. Temples and palaces have vanished like tents from the hillside. The ploughshare of havoc has been driven through the gardens of luxury. Cities have risen and crumbled upon the ruins of older cities. Crust after crust of pious legend has formed over the deep valleys; and tradition has set up its altars "upon every high hill and under every [page 5] green tree." The rival claims of sacred places are fiercely disputed by churchmen and scholars. It is a poor prophet that has but one birthplace and one tomb.

And now, to complete the confusion, the hurried, nervous, comfort-loving spirit of modern curiosity has broken into Palestine, with railways from Jaffa to Jerusalem, from Mount Carmel to the Sea of Galilee, from Beirût to Damascus,—with macadamized roads to Shechem and Nazareth and Tiberias,—with hotels at all the "principal points of interest,"—and with every facility for doing Palestine in ten days, without getting away from the market-reports, the gossip of the table d'hôte, and all that queer little complex of distracting habits which we call civilization.

But the Holy Land which I desire to see can be found only by escaping from these things. I want to get away from them; to return into the long past, which is also the hidden present, and to lose myself a little there, to the end that I may find myself again. I want to make acquaintance with the soul of that land where so much that is strange and memorable and for ever beautiful has come to pass: to walk [page 6] quietly and humbly, without much disputation or talk, in fellowship with the spirit that haunts those hills and vales, under the influence of that deep and lucent sky. I want to feel that ineffable charm which breathes from its mountains, meadows and streams: that charm which made the children of Israel in the desert long for it as a land flowing with milk and honey; and the great Prince Joseph in Egypt require an oath of his brethren that they would lay his bones in the quiet vale of Shechem where he had fed his father's sheep; and the daughters of Jacob beside the rivers of Babylon mingle tears with their music when they remembered Zion.

There was something in that land, surely, some personal and indefinable spirit of place, which was known and loved by prophet and psalmist, and most of all by Him who spread His table on the green grass, and taught His disciples while they walked the narrow paths waist-deep in rustling wheat, and spoke His messages of love from a little boat rocking on the lake, and found His asylum of prayer high on the mountainside, and kept His parting-hour with His friends in the moon-silvered quiet of the [page 7] garden of olives. That spirit of place, that soul of the Holy Land, is what I fain would meet on my pilgrimage,—for the sake of Him who interprets it in love. And I know well where to find it,—out-of-doors.

I will not sleep under a roof in Palestine, but nightly pitch my wandering tent beside some fountain, in some grove or garden, on some vacant threshing-floor, beneath the Syrian stars. I will not join myself to any company of labelled tourists hurrying with much discussion on their appointed itinerary, but take into fellowship three tried and trusty comrades, that we may enjoy solitude together. I will not seek to make any archæological discovery, nor to prove any theological theory, but simply to ride through the highlands of Judea, and the valley of Jordan, and the mountains of Gilead, and the rich plains of Samaria, and the grassy hills of Galilee, looking upon the faces and the ways of the common folk, the labours of the husbandman in the field, the vigils of the shepherd on the hillside, the games of the children in the market-place, and reaping

"The harvest of a quiet eye

That broods and sleeps on his own heart."

Four things, I know, are unchanged amid all the changes that have passed over the troubled and bewildered land. The cities have sunken into dust: the trees of the forest have fallen: the nations have dissolved. But the mountains keep their immutable outline: the liquid stars shine with the same light, move on the same pathways: and between the mountains and the stars, two other changeless things, frail and imperishable,—the flowers that flood the earth in every springtide, and the human heart where hopes and longings and affections and desires blossom immortally. Chiefly of these things, and of Him who gave them a new meaning, I will speak to you, reader, if you care to go with me out-of-doors in the Holy Land.

Of the voyage, made with all the swiftness and directness of one who seeks the shortest distance between two points, little remains in memory except a few moving pictures, vivid and half-real, as in a kinematograph.

First comes a long, swift ship, the Deutschland, quivering and rolling over the dull March waves of the Atlantic. Then the morning sunlight streams on the jagged rocks of the Lizard, where two wrecked steamships are hanging, and on the green headlands and gray fortresses of Plymouth. Then a soft, rosy sunset over the mole, the dingy houses, the tiled roofs, the cliffs, the misty-budded trees of Cherbourg. Then Paris at two in the morning: the lower quarters still stirring with somnambulistic life, the lines of lights twinkling placidly on the empty boulevards. Then a whirl through the Bois in a motor-car, a breakfast at Versailles with a merry little party of friends, a lazy walk through miles of picture-galleries [page 10] without a guide-book or a care. Then the night express for Italy, a glimpse of the Alps at sunrise, snow all around us, the thick darkness of the Mount Cenis tunnel, the bright sunshine of Italian spring, terraced hillsides, clipped and pollarded trees, waking vineyards and gardens, Turin, Genoa, Rome, arches of ruined aqueducts, snow upon the Southern Apennines, the blooming fields of Capua, umbrella-pines and silvery poplars, and at last, from my balcony at the hotel, the glorious curving panorama of the bay of Naples, Vesuvius without a cloud, and Capri like an azure lion couchant on the broad shield of the sea. So ends the first series of films, ten days from home.

After an intermission of twenty-four hours, the second series begins on the white ship Oceana, an immense yacht, ploughing through the tranquil, sapphire Mediterranean, with ten passengers on board, and the band playing three times a day just as usual. Then comes the low line of the African coast, the lighthouse of Alexandria, the top of Pompey's Pillar showing over the white, modern city.

Half a dozen little rowboats meet us, well out at [page 11] sea, buffeted and tossed by the waves: they are fishing: see! one of the men has a strike, he pulls in his trolling-line, hand over hand, very slowly, it seems, as the steamship rushes by. I lean over the side, run to the stern of the ship to watch,—hurrah, he pulls in a silvery fish nearly three feet long. Good luck to you, my Egyptian brother of the angle!

Now a glimpse of the crowded, busy harbour of Alexandria, (recalling memories of fourteen years ago,) and a leisurely trans-shipment to the little Khedivial steamer, Prince Abbas, with her Scotch officers, Italian stewards, Maltese doctor, Turkish sailors, and freight-handlers who come from whatever places it has pleased Heaven they should be born in. The freight is variegated, and the third-class passengers are a motley crowd.

A glance at the forward main-deck shows Egyptians in white cotton, and Turks in the red fez, and Arabs in white and brown, and coal-black Soudanese, and nondescript Levantines, and Russians in fur coats and lamb's-wool caps, and Greeks in blue embroidered jackets, and women in baggy trousers and black veils, and babies, and cats, and parrots. [page 12] Here is a tall, venerable grandfather, with spectacles and a long gray beard, dressed in a black robe with a hood and a yellow scarf; grave, patriarchal, imperturbable: his little granddaughter, a pretty elf of a child, with flower-like face and shining eyes, dances hither and yon among the chaos of freight and luggage; but as the chill of evening descends she takes shelter between his knees, under the folds of his long robe, and, while he feeds her with bread and sweetmeats, keeps up a running comment of remarks and laughter at all around her, and the unspeakable solemnity of old Father Abraham's face is lit up, now and then, with the flicker of a resistless smile.

Here are two bronzed Arabs of the desert, in striped burnoose and white kaftan, stretched out for the night upon their rugs of many colours. Between them lies their latest purchase, a brand-new patent carpet-sweeper, made in Ohio, and going, who knows where among the hills of Bashan.

A child dies in the night, on the voyage; in the morning, at anchor in the mouth of the Suez Canal, we hear the carpenter hammering together a little pine coffin. All day Sunday the indescribable traffic [page 13] of Port Saïd passes around us; ships of all nations coming and going; a big German Lloyd boat just home from India crowded with troops in khâki, band playing, flags flying; huge dredgers, sombre, oxlike-looking things, with lines of incredibly dirty men in fluttering rags running up the gang-planks with bags of coal on their backs; rowboats shuttling to and fro between the ships and the huddled, transient, modern town, which is made up of curiosity shops, hotels, business houses and dens of iniquity; a row of Egyptian sail boats, with high prows, low sides, long lateen yards, ranged along the entrance to the canal. At sunset we steam past the big statue of Ferdinand de Lesseps, standing far out on the break-water and pointing back with a dramatic gesture to his world-transforming ditch. Then we go dancing over the yellow waves into the full moonlight toward Palestine.

In the early morning I clamber on deck into a thunderstorm: wild west wind, rolling billows, flying gusts of rain, low clouds hanging over the sand-hills of the coast: a harbourless shore, far as eye can see, a [page 14] land that makes no concession to the ocean with bay or inlet, but cries, "Hitherto shalt thou come, but no farther; and here shall thy proud waves be stayed." There are the flat-roofed houses, and the orange groves, and the minaret, and the lighthouse of Jaffa, crowning its rounded hill of rock. We are tossing at anchor a mile from the shore. Will the boats come out to meet us in this storm, or must we go on to Haifâ, fifty miles beyond? Rumour says that the police have refused to permit the boats to put out. But look, here they come, half a dozen open whale-boats, each manned by a dozen lusty, bare-legged, brown rowers, buffeting their way between the scattered rocks, leaping high on the crested waves. The chiefs of the crews scramble on board the steamer, identify the passengers consigned to the different tourist-agencies, sort out the baggage and lower it into the boats.

Jaffa.

Jaffa.My tickets, thus far, have been provided by the great Cook, and I fall to the charge of his head boatman, a dusky demon of energy. A slippery climb down the swaying ladder, a leap into the arms of two sturdy rowers, a stumble over the wet thwarts, and I [page 15] find myself in the stern sheets of the boat. A young Dutchman follows with stolid suddenness. Two Italian gentlemen, weeping, refuse to descend more than half-way, climb back, and are carried on to Haifâ. A German lady with a parrot in a cage comes next, and her anxiety for the parrot makes her forget to be afraid. Then comes a little Polish lady, evidently a bride; she shuts her eyes tight and drops into the boat, pale, silent, resolved that she will not scream: her husband follows, equally pale, and she clings indifferently to his hand and to mine, her eyes still shut, a pretty image of white courage. The boat pushes off; the rowers smite the waves with their long oars and sing "Halli—yallah—yah hallah"; the steersman high in the stern shouts unintelligible (and, I fear, profane) directions; we are swept along on the tops of the waves, between the foaming rocks, drenched by spray and flying showers: at last we bump alongside the little quay, and climb out on the wet, gliddery stones.

The kinematograph pictures are ended, for I am in Palestine, on the first of April, just fifteen days from home.

Will my friends be here to meet me, I wonder? This is the question which presses upon me more closely than anything else, I must confess, as I set foot for the first time upon the sacred soil of Palestine. I know that this is not as it should be. All the conventions of travel require the pilgrim to experience a strange curiosity and excitement, a profound emotion, "a supreme anguish," as an Italian writer describes it, "in approaching this land long dreamed about, long waited for, and almost despaired of."

But the conventions of travel do not always correspond to the realities of the heart. Your first sight of a place may not be your first perception of it: that may come afterward, in some quiet, unexpected moment. Emotions do not follow a time-table; and I propose to tell no lies in this book. My strongest feeling as I enter Jaffa is the desire to know whether my chosen comrades have come to the rendezvous at the appointed time, to begin our long ride together.

It is a remote and uncertain combination, I grant you. The Patriarch, a tall, slender youth of seventy years, whose home is beside the Golden Gate of California, was wandering among the ruins of Sicily when I last heard from him. The Pastor and his wife, the Lady of Walla Walla, who live on the shores of Puget Sound, were riding camels across the peninsula of Sinai and steamboating up the Nile. Have the letters, the cablegrams that were sent to them been safely delivered? Have the hundreds of unknown elements upon which our combination depended been working secretly together for its success? Has our proposal been according to the supreme disposal, and have all the roads been kept clear by which we were hastening from three continents to meet on the first day of April at the Hotel du Parc in Jaffa?

Yes, here are my three friends, in the quaint little garden of the hotel, with its purple-flowering vines of Bougainvillea, fragrant orange-trees, drooping palms, and long-tailed cockatoos drowsing on their perches. When people really know each other an unfamiliar meeting-place lends a singular intimacy [page 18] and joy to the meeting. There is a surprise in it, no matter how long and carefully it has been planned. There are a thousand things to talk of, but at first nothing will come except the wonder of getting together. The sight of the desired faces, unchanged beneath their new coats of tan, is a happy assurance that personality is not a dream. The touch of warm hands is a sudden proof that friendship is a reality.

Presently it begins to dawn upon us that there is something wonderful in the place of our conjunction, and we realise dimly,—very dimly, I am sure, and yet with a certain vague emotion of reverence,—where we are.

"We came yesterday," says the Lady, "and in the afternoon we went to see the House of Simon the Tanner, where they say the Apostle Peter lodged."

"Did it look like the real house?"

"Ah," she answers smilingly, "how do I know? They say there are two of them. But what do I care? It is certain that we are here. And I think that St. Peter was here once, too, whether the house he lived in is standing yet, or not."

Yes, that is reasonably certain; and this is the place where he had his strange vision of a religion meant for all sorts and conditions of men. It is certain, also, that this is the port where Solomon landed his beams of cedar from Lebanon for the building of the Temple, and that the Emperor Vespasian sacked the town, and that Richard Lionheart planted the banner of the crusade upon its citadel. But how far away and dreamlike it all seems, on this spring morning, when the wind is tossing the fronds of the palm-trees, and the gleams of sunshine are flying across the garden, and the last clouds of the broken thunderstorm are racing westward through the blue toward the highlands of Judea.

Here is our new friend, the dragoman George Cavalcanty, known as "Telhami," the Bethlehemite, standing beside us in the shelter of the orange-trees: a trim, alert figure, in his belted suit of khâki and his riding-boots of brown leather.

"Is everything ready for the journey, George?"

"Everything is prepared, according to the instructions you sent from Avalon. The tents are pitched a little beyond Latrûn, twenty miles away. The horses [page 20] are waiting at Ramleh. After you have had your mid-day breakfast, we will drive there in carriages, and get into the saddle, and ride to our own camp before the night falls."

Happy is the man that seeth the face of a friend in a far country:

The darkness of his heart is melted in the rising of an inward joy.

It is like the sound of music heard long ago and half forgotten:

It is like the coming back of birds to a wood that winter hath made bare.

I knew not the sweetness of the fountain till I found it flowing in the desert:

Nor the value of a friend till the meeting in a lonely land.

The multitude of mankind had bewildered me and oppressed me:

And I said to God, Why hast thou made the world so wide?

But when my friend came the wideness of the world had no more terror:

Because we were glad together among men who knew us not.

[page 22]

I was slowly reading a book that was written in a strange language:

And suddenly I came upon a page in mine own familiar tongue.

This was the heart of my friend that quietly understood me:

The open heart whose meaning was clear without a word.

O my God whose love followeth all thy pilgrims and strangers:

I praise thee for the comfort of comrades on a distant road.

You understand that what we had before us in this first stage of our journey was a very simple proposition. The distance from Jaffa to Jerusalem is fifty miles by railway and forty miles by carriage-road. Thousands of pilgrims and tourists travel it every year; and most of them now go by the train in about four hours, with advertised stoppages of three minutes at Lydda, eight minutes at Ramleh, ten minutes at Sejed, and unadvertised delays at the convenience of the engine. But we did not wish to get our earliest glimpse of Palestine from a car-window, nor to begin our travels in a mechanical way. The first taste of a journey often flavours it to the very end.

The old highroad, which is now much less frequented than formerly, is very fair as far as Ramleh; and beyond that it is still navigable for vehicles, though somewhat broken and billowy. Our plan, therefore, was to drive the first ten miles, where the [page 26] road was flat and uninteresting, and then ride the rest of the way. This would enable us to avoid the advertised rapidity and the uncertain delays of the railway, and bring us quietly through the hills, about the close of the second day, to the gates of Jerusalem.

The two victorias rattled through the streets of Jaffa, past the low, flat-topped Oriental houses, the queer little open shops, the orange-groves in full bloom, the palm-trees waving their plumes over garden-walls, and rolled out upon the broad highroad across the fertile, gently undulating Plain of Sharon. On each side were the neat, well-cultivated fields and vegetable-gardens of the German colonists belonging to the sect of the Templers. They are a people of antique theology and modern agriculture. Believing that the real Christianity is to be found in the Old Testament rather than in the New, they propose to begin the social and religious reformation of the world by a return to the programme of the Minor Prophets. But meantime they conduct their farming operations in a very profitable way. Their grain-fields, their fruit-orchards, their vegetable-gardens are trim and [page 27] orderly, and they make an excellent wine, which they call "The Treasure of Zion." Their effect upon the landscape, however, is conventional.

But in spite of the presence and prosperity of the Templers, the spirit of the scene through which we passed was essentially Oriental. The straggling hedges of enormous cactus, the rows of plumy eucalyptus-trees, the budding figs and mulberries, gave it a semi-tropical touch and along the highway we encountered fragments of the leisurely, dishevelled, dignified East: grotesque camels, pensive donkeys carrying incredible loads, flocks of fat-tailed sheep and lop-eared goats, bronzed peasants in flowing garments, and white-robed women with veiled faces.

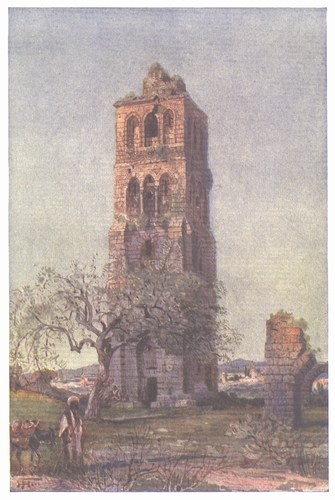

Beneath the tall tower of the forty martyrs at Ramleh (Mohammedan or Christian, their names are forgotten) we left the carriages, loaded our luggage on the three pack-mules, mounted our saddle-horses, and rode on across the plain, one of the fruitful gardens and historic battle-fields of the world. Here the hosts of the Israelites and the Philistines, the Egyptians and the Romans, the Persians and the Arabs, the Crusaders and the Saracens, have marched [page 28] and contended. But as we passed through the sun-showers and rain-showers of an April afternoon, all was tranquillity and beauty on every side. The rolling fields were embroidered with innumerable flowers. The narcissus, the "rose of Sharon," had faded. But the little blue "lilies-of-the-valley" were there, and the pink and saffron mallows, and the yellow and white daisies, and the violet and snow of the drooping cyclamen, and the gold of the genesta, and the orange-red of the pimpernel, and, most beautiful of all, the glowing scarlet of the numberless anemones. Wide acres of young wheat and barley glistened in the light, as the wind-waves rippled through their short, silken blades. There were few trees, except now and then an olive-orchard or a round-topped carob with its withered pods.

"The Tall Tower of the Forty Martyrs at Ramleh."

"The Tall Tower of the Forty Martyrs at Ramleh."

The highlands of Judea lay stretched out along the eastern horizon, a line of azure and amethystine heights, changing colour and seeming almost to breathe and move as the cloud shadows fleeted over them, and reaching away northward and southward as far as eye could see. Rugged and treeless, save for a clump of oaks or terebinths planted here or [page 29] there around some Mohammedan saint's tomb, they would have seemed forbidding but that their slopes were clothed with the tender herbage of spring, their outlines varied with deep valleys and blue gorges, and all their mighty bulwarks jewelled right royally with the opalescence of sunset.

In a hollow of the green plain to the left we could see the white houses and the yellow church tower of Lydda, the supposed burial-place of Saint George of Cappadocia, who killed the dragon and became the patron saint of England. On a conical hill to the right shone the tents of the Scotch explorer who is excavating the ancient city of Gezer, which was the dowry of Pharaoh's daughter when she married King Solomon. City, did I say? At least four cities are packed one upon another in that grassy mound, the oldest going back to the flint age; and yet if you should examine their site and measure their ruins, you would feel sure that none of them could ever have amounted to anything more than what we should call a poor little town.

It came upon us gently but irresistibly that afternoon, as we rode easily across the land of the Philistines [page 30] in a few hours, that we had never really read the Old Testament as it ought to be read,—as a book written in an Oriental atmosphere, filled with the glamour, the imagery, the magniloquence of the East. Unconsciously we had been reading it as if it were a collection of documents produced in Heidelberg, Germany, or in Boston, Massachusetts: precise, literal, scientific.

We had been imagining the Philistines as a mighty nation, and their land as a vast territory filled with splendid cities and ruled by powerful monarchs. We had been trying to understand and interpret the stories of their conflict with Israel as if they had been written by a Western war-correspondent, careful to verify all his statistics and meticulous in the exact description of all his events. This view of things melted from us with a gradual surprise as we realised that the more deeply we entered into the poetry, the closer we should come to the truth, of the narrative. Its moral and religious meaning is firm and steadfast as the mountains round about Jerusalem; but even as those mountains rose before us glorified, uplifted, and bejewelled [page 31] by the vague splendours of the sunset, so the form of the history was enlarged and its colours irradiated by the figurative spirit of the East.

There at our feet, bathed in the beauty of the evening air, lay the Valley of Aijalon, where Joshua fought with the "five kings of the Amorites," and broke them and chased them. The "kings" were head-men of scattered villages, chiefs of fierce and ragged tribes. But the fighting was hard, and as Joshua led his wild clansmen down upon them from the ascent of Beth-horon, he feared the day might be too short to win the victory. So he cheered the hearts of his men with an old war-song from the Book of Jasher.

Does any one suppose that this is intended to teach us that the sun moves and that on this day his course was arrested? Must we believe that the whole solar system was dislocated for the sake of this battle? To understand the story thus is to misunderstand its vital spirit. It is poetry, imagination, heroism. By [page 32] the new courage that came into the hearts of Israel with their leader's song, the Lord shortened the conflict to fit the day, and the sunset and the moonrise saw the Valley of Aijalon swept clean of Israel's foes.

As we passed through the wretched, mud-built village of Latrûn (said to be the birthplace of the Penitent Thief), a dozen long-robed Arabs were earnestly discussing some question of municipal interest in the grassy market-place. They were as grave as the storks, in their solemn plumage of black and white, which were parading philosophically along the edge of a marsh to our right. A couple of jackals slunk furtively across the road ahead of us in the dusk. A kafila of long-necked camels undulated over the plain. The shadows fell more heavily over cactus-hedge and olive-orchard as we turned down the hill.

In the valley night had come. The large, trembling stars were strewn through the vault above us, and rested on the dim ridges of the mountains, and shone reflected in the puddles of the long road like fallen jewels. The lights of Latrûn, if it had any, were already out of sight behind us. Our horses were weary and began to stumble. Where was the camp? [page 33] Look, there is a light, bobbing along the road toward us. It is Youssouf, our faithful major-domo, come out with a lantern to meet us. A few rods farther through the mud, and we turn a corner beside an acacia hedge and the ruined arch of an ancient well. There, in a little field of flowers, close to the tiniest of brooks, our tents are waiting for us with open doors. The candles are burning on the table. The rugs are spread and the beds are made. The dinner-table is laid for four, and there is a bright

bunch of flowers in the middle of it. We have seen the excellency of Sharon and the moon is shining for us on the Valley of Aijalon.

It is no hardship to rise early in camp. At the windows of a house the daylight often knocks as an unwelcome messenger, rousing the sleeper with a sudden call. But through the roof and the sides of a tent it enters gently and irresistibly, embracing you [page 34] with soft arms, laying rosy touches on your eyelids; and while your dream fades you know that you are awake and it is already day.

As we lift the canvas curtains and come out of our pavilions, the sun is just topping the eastern hills, and all the field around us glittering with immense drops of dew. On the top of the ruined arch beside the camp our Arab watchman, hired from the village of Latrûn as we passed, is still perched motionless, wrapped in his flowing rags, holding his long gun across his knees.

"Salâm 'aleikum, yâ ghafîr!" I say, and though my Arabic is doubtless astonishingly bad, he knows my meaning; for he answers gravely, "'Aleikum essalâm!—And with you be peace!"

It is indeed a peaceful day in which our journey to Jerusalem is completed. Leaving the tents and impedimenta in charge of Youssouf and Shukari the cook, and the muleteers, we are in the saddle by seven o'clock, and riding into the narrow entrance of the Wâdi 'Ali. It is a long, steep valley leading into the heart of the hills. The sides are ribbed with rocks, among which the cyclamens grow in profusion. [page 35]A few olives are scattered along the bottom of the vale, and at the tomb of the Imâm 'Ali there is a grove of large trees. At the summit of the pass we rest for half an hour, to give our horses a breathing-space, and to refresh our eyes with the glorious view westward over the tumbled country of the Shephelah, the opalescent Plain of Sharon, the sand-hills of the coast, and the broad blue of the Mediterranean. Northward and southward and eastward the rocky summits and ridges of Judea roll away.

Now we understand what the Psalmist means by ascribing "the strength of the hills" to Jehovah; and a new light comes into the song:

"As the mountains are round about Jerusalem,

So Jehovah is round about his people."

These natural walls and terraces of gray limestone have the air of antique fortifications and watch-towers of the border. They are truly "munitions of rocks." Chariots and horsemen could find no field for their manœuvres in this broken and perpendicular country. Entangled in these deep and winding valleys by which they must climb up from the plain, the [page 36] invaders would be at the mercy of the light infantry of the highlands, who would roll great stones upon them as they passed through the narrow defiles, and break their ranks by fierce and sudden downward rushes as they toiled panting up the steep hillsides. It was this strength of the hills that the children of Israel used for the defence of Jerusalem, and by this they were able to resist and defy the Philistines, whom they could never wholly conquer.

Yonder on the hillside, as we ride onward, we see a reminder of that old tribal warfare between the people of the highlands and the people of the plains. That gray village, perched upon a rocky ridge above thick olive-orchards and a deliciously green valley, is the ancient Kirjath-Jearim, where the Ark of Jehovah was hidden for twenty years, after the Philistines had sent back this perilous trophy of their victory over the sons of Eli, being terrified by the pestilence and disaster that followed its possession. The men of Beth-shemesh, to whom it was first returned, were afraid to keep it, because they also had been smitten with death when they dared to peep into this dreadful box. But the men of Kirjath-Jearim [page 37] were at once bolder and wiser, so they "came and fetched up the Ark of Jehovah, and brought it into the house of Abinadab in the hill, and set apart Eleazar, his son, to keep the Ark of Jehovah."

What strange vigils in that little hilltop cottage where the young man watches over this precious, dangerous, gilded coffer, while Saul is winning and losing his kingdom in a turmoil of blood and sorrow and madness, forgetful of Israel's covenant with the Most High! At last comes King David, from his newly won stronghold of Zion, seeking eagerly for this lost symbol of the people's faith. "Lo, we heard of it at Ephratah; we found it in the field of the wood." So the gray stone cottage on the hilltop gave up its sacred treasure, and David carried it away with festal music and dancing. But was Eleazar glad, I wonder, or sorry, that his long vigil was ended?

To part from a care is sometimes like losing a friend.

I confess that it is difficult to make these ancient stories of peril and adventure, (or even the modern history of Abu Ghôsh the robber-chief of this village [page 38] a hundred years ago), seem real to us to-day. Everything around us is so safe and tranquil, and, in spite of its novelty, so familiar. The road descends steeply with long curves and windings into the Wâdi Beit Hanîna. We meet and greet many travellers, on horseback, in carriages and afoot, natives and pilgrims, German colonists, French priests, Italian monks, English tourists and explorers. It is a pleasant game to guess from an approaching pilgrim's looks whether you should salute him with "Guten Morgen," or "Buon' Giorno," or "Bon jour, m'sieur." The country people answer your salutation with a pretty phrase: "Nehârak saîd umubârak—May your day be happy and blessed."

At Kalôniyeh, in the bottom of the valley, there is a prosperous settlement of German Jews; and the gardens and orchards are flourishing. There is also a little wayside inn, a rude stone building, with a terrace around it; and there, with apricots and plums blossoming beside us, we eat our lunch al fresco, and watch our long pack-train, with the camp and baggage, come winding down the hill and go tinkling past us toward Jerusalem.

The place is very friendly; we are in no haste to leave it. A few miles to the southward, sheltered in the lap of a rounding hill, we can see the tall cypress-trees and quiet gardens of 'Ain Karîm, the village where John the Baptist was born. It has a singular air of attraction, seen from a distance, and one of the sweetest stories in the world is associated with it. For it was there that the young bride Mary visited her older cousin Elizabeth,—you remember the exquisite picture of the "Visitation" by Albertinelli in the Uffizi at Florence,—and the joy of coming motherhood in these two women's hearts spoke from each to each like a bell and its echo. Would the birth of Jesus, the character of Jesus, have been possible unless there had been the virginal and expectant soul of such a woman as Mary, ready to welcome His coming with her song? "My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour." Does not the advent of a higher manhood always wait for the hope and longing of a nobler womanhood?

The chiming of the bells of St. John floats faintly and silverly across the valley as we leave the shelter [page 40] of the wayside rest-house and mount for the last stage of our upward journey. The road ascends steeply. Nestled in the ravine to our left is the grizzled and dilapidated village of Liftâ, a town with an evil reputation.

"These people sold all their land," says George the dragoman, "twenty years ago, sold all the fields, gardens, olive-groves. Now they are dirty and lazy in that village,—all thieves!"

Over the crest of the hill the red-tiled roofs of the first houses of Jerusalem are beginning to appear. They are houses of mercy, it seems: one an asylum for the insane, the other a home for the aged poor. Passing them, we come upon schools and hospital buildings and other evidences of the charity of the Rothschilds toward their own people. All around us are villas and consulates, and rows of freshly built houses for Jewish colonists.

This is not at all the way that we had imagined to ourselves the first sight of the Holy City. All here is half-European, unromantic, not very picturesque. It may not be "the New Jerusalem," but it is certainly a modern Jerusalem. Here, in these comfortably [page 41] commonplace dwellings, is almost half the present population of the city; and rows of new houses are rising on every side.

But look down the southward-sloping road. There is the sight that you have imagined and longed to see: the brown battlements, the white-washed houses, the flat roofs, the slender minarets, the many-coloured domes of the ancient city of David, and Solomon, and Hezekiah, and Herod, and Omar, and Godfrey, and Saladin,—but never of Christ. That great black dome is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The one beyond it is the Mosque of Omar. Those golden bulbs and pinnacles beyond the city are the Greek Church of Saint Mary Magdalen on the side of the Mount of Olives; and on the top of the lofty ridge rises the great pointed tower of the Russians from which a huge bell booms out a deep-toned note of welcome.

On every side we see the hospices and convents and churches and palaces of the different sects of Christendom. The streets are full of people and carriages and beasts of burden. The dust rises around us. We are tired with the trab, trab, trab of [page 42] our horses' feet upon the hard highroad. Let us not go into the confusion of the city, but ride quietly down to the left into a great olive-grove, outside the Damascus Gate.

Here our white tents are pitched among the trees, with the dear flag of our home flying over them. Here we shall find leisure and peace to unite our hearts, and bring our thoughts into tranquil harmony, before we go into the bewildering city. Here the big stars will look kindly down upon us through the silvery leaves, and the sounds of human turmoil and contention will not trouble us. The distant booming of the bell on the Mount of Olives will mark the night-hours for us, and the long-drawn plaintive call of the muezzin from the minaret of the little mosque at the edge of the grove will wake us to the sunrise.

This is the thanksgiving of the weary:

The song of him that is ready to rest.

It is good to be glad when the day is declining:

And the setting of the sun is like a word of peace.

The stars look kindly on the close of a journey:

The tent says welcome when the day's march is done.

For now is the time of the laying down of burdens:

And the cool hour cometh to them that have borne the heat.

I have rejoiced greatly in labour and adventure:

My heart hath been enlarged in the spending of my strength.

Now it is all gone yet I am not impoverished:

For thus only may I inherit the treasure of repose.

Blessed be the Lord that teacheth my hands to unclose and my fingers to loosen:

He also giveth comfort to the feet that are washed from the dust of the way.

[page 44]

Blessed be the Lord that maketh my meat at nightfall savoury:

And filleth my evening cup with the wine of good cheer.

Blessed be the Lord that maketh me happy to be quiet:

Even as a child that cometh softly to his mother's lap.

O God thou faintest not neither is thy strength worn away with labour:

But it is good for us to be weary that we may obtain thy gift of rest.

Out of the medley of our first impressions of Jerusalem one fact emerges like an island from the sea: it is a city that is lifted up. No river; no harbour; no encircling groves and gardens; a site so lonely and so lofty that it breathes the very spirit of isolation and proud self-reliance.

"Beautiful in elevation, the joy of the whole earth

Is Mount Zion, on the sides of the north

The city of the great King."

Thus sang the Hebrew poet; and his song, like all true poetry, has the accuracy of the clearest vision. For this is precisely the one beauty that crowns Jerusalem: the beauty of a high place and all that belongs to it: clear sky, refreshing air, a fine outlook, and that indefinable sense of exultation that comes into the heart of man when he climbs a little nearer to the stars.

Twenty-five hundred feet above the level of the [page 48] sea is not a great height; but I can think of no other ancient and world-famous city that stands as high. Along the mountainous plateau of Judea, between the sea-coast plain of Philistia and the sunken valley of the Jordan, there is a line of sacred sites,—Beërsheba, Hebron, Bethlehem, Bethel, Shiloh, Shechem. Each of them marks the place where a town grew up around an altar. The central link in this chain of shrine-cities is Jerusalem. Her form and outline, her relation to the landscape and to the land, are unchanged from the days of her greatest glory. The splendours of her Temple and her palaces, the glitter of her armies, the rich colour and glow of her abounding wealth, have vanished. But though her garments are frayed and weather-worn, though she is an impoverished and dusty queen, she still keeps her proud position and bearing; and as you approach her by the ancient road along the ridges of Judea you see substantially what Sennacherib, and Nebuchadnezzar, and the Roman Titus must have seen.

"The sides of the north" slope gently down to the huge gray wall of the city, with its many towers and gates. Within those bulwarks, which are thirty-eight [page 49] feet high and two and a half miles in circumference, "Jerusalem is builded as a city that is compact together," covering with her huddled houses and crooked, narrow streets, the two or three rounded hills and shallow depressions in which the northern plateau terminates. South and east and west, the valley of the Brook Kidron and the Valley of Himmon surround the city wall with a dry moat three or four hundred feet deep.

Imagine the knuckles of a clenched fist, extended toward the south: that is the site of Jerusalem, impregnable, (at least in ancient warfare), from all sides except the north, where the wrist joins it to the higher tableland. This northern approach, open to Assyria, and Babylon, and Damascus, and Persia, and Greece, and Rome, has always been the weak point of Jerusalem. She was no unassailable fortress of natural strength, but a city lifted up, a lofty shrine, whose refuge and salvation were in Jehovah,—in the faith, the loyalty, the courage which flowed into the heart of her people from their religion. When these failed, she fell.

Jerusalem is no longer, and never again will be, [page 50] the capital of an earthly kingdom. But she is still one of the high places of the world, exalted in the imagination and the memory of Jews and Christians and Mohammedans, a metropolis of infinite human hopes and longings and devotions. Hither come the innumerable companies of foot-weary pilgrims, climbing the steep roads from the sea-coast, from the Jordan, from Bethlehem,—pilgrims who seek the place of the Crucifixion, pilgrims who would weep beside the walls of their vanished Temple, pilgrims who desire to pray where Mohammed prayed. Century after century these human throngs have assembled from far countries and toiled upward to this open, lofty plateau, where the ancient city rests upon the top of the closed hand, and where the ever-changing winds from the desert and the sea sweep and shift over the rocky hilltops, the mute, gray battlements, and the domes crowned with the cross, the crescent, and the star.

"The wind bloweth where it will, and thou hearest the voice thereof, but knowest not whence it cometh, nor whither it goeth; so is every one that is born of the Spirit."

The mystery of the heart of mankind, the spiritual airs that breathe through it, the desires and aspirations that impel men in their journeyings, the common hopes that bind them together in companies, the fears and hatreds that array them in warring hosts,—there is no place in the world to-day where you can feel all this so deeply, so inevitably, so overwhelmingly, as at the Gates of Zion.

It is a feeling of confusion, at first: a bewildering sense of something vast and old and secret, speaking many tongues, taking many forms, yet never fully revealing its source and its meaning. The Jews, Mohammedans, and Christians who flock to those gates are alike in their sincerity, in their devotion, in the spirit of sacrifice that leads them on their pilgrimage. Among them all there are hypocrites and bigots, doubtless, but there are also earnest and devout souls, seeking something that is higher than themselves, "a city set upon a hill." Why do they not understand one another? Why do they fight and curse one another? Do they not all come to humble themselves, to pray, to seek the light?

Dark walls that embrace so many tear-stained, [page 52] blood-stained, holy and dishonoured shrines! And you, narrow and gloomy gates, through whose portals so many myriads of mankind have passed with their swords, their staves, their burdens and their palm-branches! What songs of triumph you have heard, what yells of battle-rage, what moanings of despair, what murmurs of hopes and gratitude, what cries of anguish, what bursts of careless, happy laughter,—all borne upon the wind that bloweth where it will across these bare and rugged heights. We will not seek to enter yet into the mysteries that you hide. We will tarry here for a while in the open sunlight, where the cool breeze of April stirs the olive-groves outside the Damascus Gate. We will tranquillize our thoughts,—perhaps we may even find them growing clearer and surer,—among the simple cares and pleasures that belong to the life of every day; the life which must have food when it is hungry, and rest when it is weary, and a shelter from the storm and the night; the life of those who are all strangers and sojourners upon the earth, and whose richest houses and strongest cities are, after all, but a little longer-lasting tents and camps.

The place of our encampment is peaceful and friendly, without being remote or secluded. The grove is large and free from all undergrowth: the trunks of the ancient olive-trees are gnarled and massive, the foliage soft and tremulous. The corner that George has chosen for us is raised above the road by a kind of terrace, so that it is not too easily accessible to the curious passer-by. Across the road we see a gray stone wall, and above it the roof of the Anglican Bishop's house, and the schools, from which a sound of shrill young voices shouting in play or chanting in unison rises at intervals through the day. The ground on which we stand is slightly furrowed with the little ridges of last year's ploughing: but it has not yet been broken this spring, and it is covered with millions of infinitesimal flowers, blue and purple and yellow and white, like tiny pansies run wild.

The four tents, each circular and about fifteen feet [page 54] in diameter, are arranged in a crescent. The one nearest to the road is for the kitchen and service; there Shukari, our Maronite chef, in his white cap and apron, turns out an admirable six-course dinner on a portable charcoal range not three feet square. Around the door of this tent there is much coming and going: edibles of all kinds are brought for sale; visitors squat in sociable conversation; curious children hang about, watching the proceedings, or waiting for the favours which a good cook can bestow.

The next tent is the dining-room; the huge wooden chests of the canteen, full of glass and china and table-linen and new Britannia-ware, which shines like silver, are placed one on each side of the entrance; behind the central tent-pole stands the dining-table, with two chairs at the back and one at each end, so that we can all enjoy the view through the open door. The tent is lofty and lined with many-coloured cotton cloth, arranged in elaborate patterns, scarlet and green and yellow and blue. When the four candles are lighted on the well-spread table, and Youssouf the Greek, in his embroidered jacket and baggy blue breeches, comes in to serve the dinner, it [page 55] is quite an Oriental scene. His assistant, Little Youssouf, the Copt, squats outside of the tent, at one side of the door, to wash up the dishes and polish the Britannia-ware.

The two other tents are of the same pattern and the same gaudy colours within: each of them contains two little iron bedsteads, two Turkish rugs, two washstands, one dressing-table, and such baggage as we had imagined necessary for our comfort, piled around the tent-pole,—this by way of precaution, lest some misguided hand should be tempted to slip under the canvas at night and abstract an unconsidered trifle lying near the edge of the tent.

Of our own men I must say that we never had a suspicion, either of their honesty or of their good-humour. Not only the four who had most immediately to do with us, but also the two chief muleteers, Mohammed 'Ali and Moûsa, and the songful boy, Mohammed el Nâsan, who warbled an interminable Arabian ditty all day long, and Fâris and the two other assistants, were models of fidelity and willing service. They did not quarrel (except once, over the division of the mule-loads, in the mountains of Gilead); [page 56] they got us into no difficulties and subjected us to no blackmail from humbugging Bedouin chiefs. They are of a picturesque motley in costume and of a bewildering variety in creed—Anglican, Catholic, Coptic, Maronite, Greek, Mohammedan, and one of whom the others say that "he belongs to no religion, but sings beautiful Persian songs." Yet, so far as we are concerned, they all do the things they ought to do and leave undone the things they ought not to do, and their way with us is peace. Much of this, no doubt, is due to the wisdom, tact, and firmness of George the Bethlehemite, the best of dragomans.

We have many visitors at the camp, but none unwelcome. The American Consul, a genial scholar who knows Palestine by heart and has made valuable contributions to the archæology of Jerusalem, comes with his wife to dine with us in the open air. George's gentle wife and his two bright little boys, Howard and Robert, are with us often. Missionaries come to tell us of their labours and trials. An Arab hunter, with his long flintlock musket, brings us beautiful gray partridges which he has shot among the near-by hills. The stable-master comes day [page 57] after day with strings of horses galloping through the grove; for our first mounts were not to our liking, and we are determined not to start on our longer ride until we have found steeds that suit us. Peasants from the country round about bring all sorts of things to sell—vegetables, and lambs, and pigeons, and old coins, and embroidered caps.

There are two men ploughing in a vineyard behind the camp, beyond the edge of the grove. The plough is a crooked stick of wood which scratches the surface of the earth. The vines are lying flat on the ground, still leafless, closely pruned: they look like big black snakes.

Women of the city, dressed in black and blue silks, with black mantles over their heads, come out in the afternoon to picnic among the trees. They sit in little circles on the grass, smoking cigarettes and eating sweetmeats. If they see us looking at them they draw the corners of their mantles across the lower part of their faces; but when they think themselves unobserved they drop their veils and regard us curiously with lustrous brown eyes.

One morning a procession of rustic women and [page 58] girls, singing with shrill voices, pass the camp on their way to the city to buy the bride's clothes for a wedding. At nightfall they return singing yet more loudly, and accompanied by men and boys firing guns into the air and shouting.

Another day a crowd of villagers go by. Their old Sheikh rides in the midst of them, with his white-and-gold turban, his long gray beard, his flowing robes of rich silk. He is mounted on a splendid white Arab horse, with arched neck and flaunting tail; and a beautiful, gaily dressed little boy rides behind him with both arms clasped around the old man's waist. They are going up to the city for the Mohammedan rite of circumcision.

Later in the day a Jewish funeral comes hurrying through the grove: some twenty or thirty men in flat caps trimmed with fur and gabardines of cotton velvet, purple, or yellow, or pink, chanting psalms as they march, with the body of the dead man wrapped in linen cloth and carried on a rude bier on their shoulders. They seem in haste, (because the hour is late and the burial must be made before sunset), perhaps a little indifferent, or almost joyful. [page 59] Certainly there is no sign of grief in their looks or their voices; for among them it is counted a fortunate thing to die in the Holy City and to be buried on the southern slope of the Valley of Jehoshaphat, where Gabriel is to blow his trumpet for the resurrection.

Outside the gates we ride, for the roads which encircle the city wall and lead off to the north and south and east and west, are fairly broad and smooth. But within the gates we walk, for the streets are narrow, steep and slippery, and to attempt them on horseback is to travel with an anxious mind.

Through the Jaffa Gate, indeed, you may easily ride, or even drive in your carriage: not through the gateway itself, which is a close and crooked alley, but through the great gap in the wall beside it, made for the German Emperor to pass through at the time of his famous imperial scouting-expedition in Syria in 1898. Thus following the track of the great William [page 60] you come to the entrance of the Grand New Hotel, among curiosity-shops and tourist-agencies, where a multitude of bootblacks assure you that you need "a shine," and valets de place press their services upon you, and ingratiating young merchants try to allure you into their establishments to purchase photographs or embroidered scarves or olive-wood souvenirs of the Holy Land.

A Street in Jerusalem.

A Street in Jerusalem.

Come over to Cook's office, where we get our letters, and stand for a while on the little terrace with the iron railing, looking at the motley crowd which fills the place in front of the citadel. Groups of blue-robed peasant women sit on the curbstone, selling firewood and grass and vegetables. Their faces are bare and brown, wrinkled with the sun and the wind. Turkish soldiers in dark-green uniform, Greek priests in black robes and stove-pipe hats, Bedouins in flowing cloaks of brown and white, pale-faced Jews with velvet gabardines and curly ear-locks, Moslem women in many-coloured silken garments and half-transparent veils, British tourists with cork helmets and white umbrellas, camels, donkeys, goats, and sheep, jostle together in picturesque confusion. [page 61] There is a water-carrier with his shiny, dripping, bulbous goat-skin on his shoulders. There is an Arab of the wilderness with a young gazelle in his arms.

Now let us go down the greasy, gliddery steps of David Street, between the diminutive dusky shops with open fronts where all kinds of queer things to eat and to wear are sold, and all sorts of craftsmen are at work making shoes, and tin pans, and copper pots, and wooden seats, and little tables, and clothes of strange pattern. A turn to the left brings us into Christian Street and the New Bazaar of the Greeks, with its modern stores.

A turn to the right and a long descent under dark archways and through dirty, shadowy alleys brings us to the Place of Lamentations, beside the ancient foundation wall of the Temple, where the Jews come in the afternoon of Fridays and festival-days to lean their heads against the huge stones and murmur forth their wailings over the downfall of Jerusalem. "For the majesty that is departed," cries the leader, and the others answer: "We sit in solitude and mourn." "We pray Thee have mercy on Zion," cries the leader, [page 62] and the others answer: "Gather the children of Jerusalem." With most of them it seems a perfunctory mourning; but there are two or three old men with the tears running down their faces as they kiss the smooth-worn stones.

We enter convents and churches, mosques and tombs. We trace the course of the traditional Via Dolorosa, and try to reconstruct in our imagination the probable path of that grievous journey from the judgment-hall of injustice to the Calvary of cruelty—a path which now lies buried far below the present level of the city.

One impression deepens in my mind with every hour: this was never Christ's city. The confusion, the shallow curiosity, the self-interest, the clashing prejudices, the inaccessibility of the idle and busy multitudes were the same in His day that they are now. It was not here that Jesus found the men and women who believed in Him and loved Him, but in the quiet villages, among the green fields, by the peaceful lake-shores. And it is not here that we shall find the clearest traces, the most intimate visions of Him, but away in the big out-of-doors, where [page 63] the sky opens free above us, and the landscapes roll away to far horizons.

As we loiter about the city, now alone, now under the discreet and unhampering escort of the Bethlehemite; watching the Mussulmans at their dinner in some dingy little restaurant, where kitchen, store-room and banquet-hall are all in the same apartment, level and open to the street; pausing to bargain with an impassive Arab for a leather belt or with an ingratiating Greek for a string of amber beads; looking in through the unshuttered windows of the Jewish houses where the families are gathered in festal array for the household rites of Passover week; turning over the chaplets, and rosaries, and anklets, and bracelets of coloured glass and mother-of-pearl, and variegated stones, and curious beans and seed-pods in the baskets of the street-vendors around the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; stepping back into an archway to avoid a bag-footed camel, or a gaily caparisoned horse, or a heavy-laden donkey passing through a narrow street; exchanging a smile and an unintelligible friendly jest with a sweet-faced, careless child; listening to long [page 64] disputes between buyers and sellers in that resounding Arab tongue which seems full of tragic indignation and wrath, while the eyes of the handsome brown Bedouins who use it remain unsearchable in their Oriental languor and pride; Jerusalem becomes to us more and more a symbol and epitome of that which is changeless and transient, capricious and inevitable, necessary and insignificant, interesting and unsatisfying, in the unfinished tragi-comedy of human life. There are times when it fascinates us with its whirling charm. There are other times when we are glad to ride away from it, to seek communion with the great spirit of some antique prophet, or to find the consoling presence of Him who spake the words of the eternal life.

How wonderful are the cities that man hath builded:

Their walls are compacted of heavy stones,

And their lofty towers rise above the tree-tops.

Rome, Jerusalem, Cairo, Damascus,—

Venice, Constantinople, Moscow, Pekin,—

London, New York, Berlin, Paris, Vienna,—

These are the names of mighty enchantments:

They have called to the ends of the earth,

They have secretly summoned an host of servants.

They shine from far sitting beside great waters:

They are proudly enthroned upon high hills,

They spread out their splendour along the rivers.

Yet are they all the work of small patient fingers:

Their strength is in the hand of man,

He hath woven his flesh and blood into their glory.

The cities are scattered over the world like ant-hills:

Every one of them is full of trouble and toil,

And their makers run to and fro within them.

[page 66]

Abundance of riches is laid up in their store-houses:

Yet they are tormented with the fear of want,

The cry of the poor in their streets is exceeding bitter.

Their inhabitants are driven by blind perturbations:

They whirl sadly in the fever of haste,

Seeking they know not what, they pursue it fiercely.

The air is heavy-laden with their breathing:

The sound of their coming and going is never still,

Even in the night I hear them whispering and crying.

Beside every ant-hill I behold a monster crouching:

This is the ant-lion Death,

He thrusteth forth his tongue and the people perish.

O God of wisdom thou hast made the country:

Why hast thou suffered man to make the town?

Then God answered, Surely I am the maker of man:

And in the heart of man I have set the city.

Mizpah of Benjamin stands to the northwest: the sharpest peak in the Judean range, crowned with a ragged, dusty village and a small mosque. We rode to it one morning over the steepest, stoniest bridle-paths that we had ever seen. The country was bleak and rocky, a skeleton of landscape; but between the stones and down the precipitous hillsides and along the hot gorges, the incredible multitude of spring flowers were abloom.

It was a stiff scramble up the conical hill to the little hamlet at the top, built out of and among ruins. The mosque, evidently an old Christian church remodelled, was bare, but fairly clean, cool, and tranquil. We peered through a grated window, tied with many-coloured scraps of rags by the Mohammedan pilgrims, into a whitewashed room containing a huge sarcophagus said to be the tomb of Samuel. Then we climbed the minaret and [page 70] lingered on the tiny railed balcony, feeding on the view.

The peak on which we stood was isolated by deep ravines from the other hills of desolate gray and scanty green. Beyond the western range lay the Valley of Aijalon, and beyond that the rich Plain of Sharon with iridescent hues of green and blue and silver, and beyond that the yellow line of the sand-dunes broken by the white spot of Jaffa, and beyond that the azure breadth of the Mediterranean. Northward, at our feet, on the summit of a lower conical hill, ringed with gray rock, lay the village of El-Jib, the ancient Geba of Benjamin, one of the cities which Joshua gave to the Levites.

This was the place from which Jonathan and his armour-bearer set out, without Saul's knowledge, on their daring, perilous scouting expedition against the Philistines. What fighting there was in olden days over that tumbled country of hills and gorges, stretching away north to the blue mountains of Samaria and the summits of Ebal and Gerizim on the horizon!

There on the rocky backbone of Benjamin and [page 71] Ephraim, was Ramallah (where we had spent Sunday in the sweet orderliness of the Friends' Mission School), and Beëroth, and Bethel, and Gilgal, and Shiloh. Eastward, behind the hills, we could trace the long, vast trench of the Jordan valley running due north and south, filled with thin violet haze and terminating in a glint of the Dead Sea. Beyond that deep line of division rose the mountains of Gilead and Moab, a lofty, unbroken barrier. To the south-east we could see the red roofs of the new Jerusalem, and a few domes and minarets of the ancient city. Beyond them, in the south, was the truncated cone of the Frank Mountain, where the crusaders made their last stand against the Saracens; and the hills around Bethlehem; and a glimpse, nearer at hand, of the tall cypresses and peaceful gardens of 'Ain Karîm.

This terrestrial paradise of vision encircled us with jewel-hues and clear, exquisite outlines. Below us were the flat roofs of Nebi Samwîl, with a dog barking on every roof; the filthy courtyards and dark doorways, with a woman in one of them making bread; the ruined archways and broken cisterns [page 72] with a pool of green water stagnating in one corner; peasants ploughing their stony little fields, and a string of donkeys winding up the steep path to the hill.

Here, centuries ago, Samuel called all Israel to Mizpah, and offered sacrifice before Jehovah, and judged the people. Here he inspired them with new courage and sent them down to discomfit the Philistines. Hither he came as judge and ruler of Israel, making his annual circuit between Gilgal and Bethel and Mizpah. Here he assembled the tribes again, when they were tired of his rule, and gave them a King according to their desire, even the tall warrior Saul, the son of Kish.

Do the bones of the prophet rest here or at Ramah? I do not know. But here, on this commanding peak, he began and ended his judgeship; from this aerie he looked forth upon the inheritance of the turbulent sons of Jacob; and here, if you like, today, a pale, clever young Mohammedan will show you what he calls the coffin of Samuel.

We had seen from Mizpah the sharp ridge of the Mount of Olives, rising beyond Jerusalem. Our road thither from the camp led us around the city, past the Damascus Gate, and the royal grottoes, and Herod's Gate, and the Tower of the Storks, and St. Stephen's Gate, down into the Valley of the Brook Kidron. Here, on the west, rises the precipitous Temple Hill crowned with the wall of the city, and on the east the long ridge of Olivet.

There are several buildings on the side of the steep hill, marking supposed holy places or sacred events—the Church of the Tomb of the Virgin, the Latin Chapel of the Agony, the Greek Church of St. Mary Magdalen. On top of the ridge are the Russian Buildings, with the Chapel of the Ascension, and the Latin Buildings, with the Church of the Creed, the Church of the Paternoster, and a Carmelite Nunnery. Among the walls of these inclosures we wound our way, and at last tied our [page 74] horses outside of the Russian garden. We climbed the two hundred and fourteen steps of the lofty Belvidere Tower, and found ourselves in possession of one of the great views of the world. There is Jerusalem, across the Kidron, spread out like a raised map below us. The mountains of Judah roll away north and south and east and west—the clean-cut pinnacle of Mizpah, the lofty plain of Rephaïm, the dark hills toward Hebron, the rounded top of Scopus where Titus camped with his Roman legions, the flattened peak of Frank Mountain. Bethlehem is not visible; but there is the tiny village of Bethphage, and the first roof of Bethany peeping over the ridge, and the Inn of the Good Samaritan in a red cut of the long serpentine road to Jericho. The dark range of Gilead and Moab seems like a huge wall of lapis-lazuli beyond the furrowed, wrinkled, yellowish clay-hills and the wide gray trench of the Jordan Valley, wherein the river marks its crooked path with a line of deep green. The hundreds of ridges that slope steeply down to that immense depression are touched with a thousand hues of amethystine light, and the ravines between them filled with a [page 75] thousand tones of azure shadow. At the end of the valley glitter the blue waters of the Dead Sea, fifteen miles away, four thousand feet below us, yet seeming so near that we almost expect to hear the sound of its waves on the rocky shores of the Wilderness of Tekoa.

On this mount Jesus of Nazareth often walked with His disciples. On this widespread landscape His eyes rested as He spoke divinely of the invisible kingdom of peace and love and joy that shall never pass away. Over this walled city, sleeping in the sunshine, full of earthly dreams and disappointments, battlemented hearts and whited sepulchres of the spirit, He wept, and cried: "O Jerusalem, how often would I have gathered thy children together even as a hen gathereth her own brood under her wings, and ye would not!"

Come down, now, from the mount of vision to the grove of olive-trees, the Garden of Gethsemane, where Jesus used to take refuge with His friends. It lies on the eastern slope of Olivet, not far above the Valley of Kidron, over against that city-gate which was called the Beautiful, or the Golden, but which is now walled up.

The grove probably belonged to some friend of Jesus or of one of His disciples, who permitted them to make use of it for their quiet meetings. At that time, no doubt, the whole hillside was covered with olive-trees, but most of these have now disappeared. The eight aged trees that still cling to life in Gethsemane have been inclosed with a low wall and an iron railing, and the little garden that blooms around them is cared for by Franciscan monks from Italy.

The gentle, friendly Fra Giovanni, in bare sandaled feet, coarse brown robe, and broad-brimmed straw hat, is walking among the flowers. He opens [page 77] the gate for us and courteously invites us in, telling us in broken French that we may pick what flowers we like. Presently I fall into discourse with him in broken Italian, telling him of my visit years ago to the cradle of his Order at Assisi, and to its most beautiful shrine at La Verna, high above the Val d'Arno. His old eyes soften into youthful brightness as he speaks of Italy. It was most beautiful, he said, bellisima! But he is happier here, caring for this garden, it is most holy, santissima!

The bronzed Mohammedan gardener, silent, patient, absorbed in his task, moves with his watering-pot among the beds, quietly refreshing the thirsty blossoms. There are wall-flowers, stocks, pansies, baby's breath, pinks, anemones of all colours, rosemary, rue, poppies—all sorts of sweet old-fashioned flowers. Among them stand the scattered venerable trees, with enormous trunks, wrinkled and contorted, eaten away by age, patched and built up with stones, protected and tended with pious care, as if they were very old people whose life must be tenderly nursed and sheltered. Their boles hardly seem to be of wood; so dark, so twisted, so furrowed are they, of [page 78] an aspect so enduring that they appear to be cast in bronze or carved out of black granite. Above each of them spreads a crown of fresh foliage, delicate, abundant, shimmering softly in the sunlight and the breeze, with silken turnings of the under side of the innumerable leaves. In the centre of the garden is a kind of open flower house with a fountain of flowing water, erected in memory of a young American girl. At each corner a pair of slender cypresses lift their black-green spires against the blanched azure of the sky.

It is a place of refuge, of ineffable tranquillity, of unforgetful tenderness. The inclosure does not offend. How else could this sacred shrine of the out-of-doors be preserved? And what more fitting guardian for it than the Order of that loving Saint Francis, who called the sun and the moon his brother and his sister and preached to a joyous congregation of birds as his "little brothers of the air"? The flowers do not offend. Their antique fragrance, gracious order, familiar looks, are a symbol of what faithful memory does with the sorrows and sufferings of those who have loved us best--she treasures and [page 79] transmutes them into something beautiful, she grows her sweetest flowers in the ground that tears have made holy.

It is here, in this quaint and carefully tended garden, this precious place which has been saved alike from the oblivious trampling of the crowd and from the needless imprisonment of four walls and a roof, it is here in the open air, in the calm glow of the afternoon, under the shadow of Mount Zion, that we find for the first time that which we have come so far to seek,—the soul of the Holy Land, the inward sense of the real presence of Jesus.