“I supposed that father was working late over some papers and I knew that I must not disturb him.”

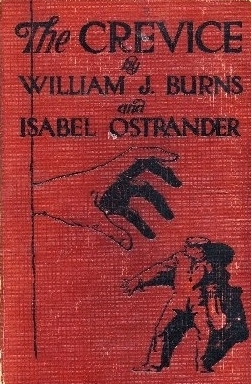

Title: The Crevice

Author: William J. Burns

Isabel Ostrander

Illustrator: Will Grefé

Release date: July 6, 2009 [eBook #29331]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank, Darleen Dove, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Roger Frank, Darleen Dove,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

“I supposed that father was working late over some papers and I knew that I must not disturb him.”

|

Copyright, 1915, by

W. J. WATT & COMPANY

CHAPTER |

PAGE |

|

| I | Pennington Lawton and the Grim Reaper | 1 |

| II | Revelations | 16 |

| III | Henry Blaine Takes a Hand | 29 |

| IV | The Search | 38 |

| V | The Will | 53 |

| VI | The First Counter-move | 66 |

| VII | The Letter | 78 |

| VIII | Guy Morrow Faces a Problem | 98 |

| IX | Gone! | 104 |

| X | Margaret Hefferman’s Failure | 116 |

| XI | The Confidence of Emily | 134 |

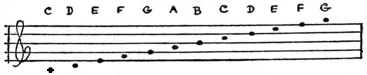

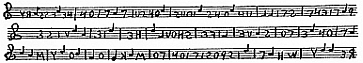

| XII | The Cipher | 154 |

| XIII | The Empty House | 171 |

| XIV | In the Open | 192 |

| XV | Checkmate! | 207 |

| XVI | The Library Chair | 224 |

| XVII | The Rescue | 240 |

| XVIII | The Trap | 255 |

| XIX | The Unseen Listener | 272 |

| XX | The Crevice | 290 |

| XXI | Cleared Skies | 308 |

PAGE |

|

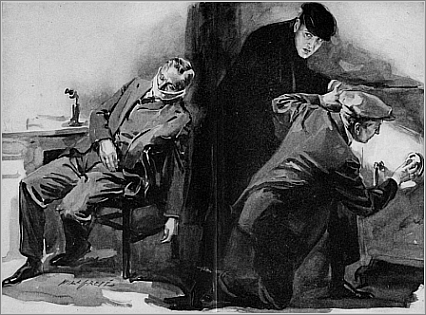

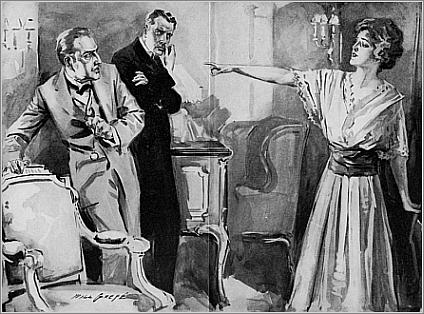

| “I supposed that father was working late over some papers and I knew that I must not disturb him.” | Frontispiece |

| With the cunning of a Jimmy Valentine he manipulated the tumblers. Ramon Hamilton, his discomfiture forgotten, watched with breathless interest. | 94 |

| Her head was thrown back, her eyes blazing: and as she faced him, she slowly raised her arm and pointed a steady finger at the recoiling figure. | 262 |

Had New Illington been part of an empire instead of one of the most important cities in the greatest republic in the world, the cry “The King is dead! Long live the King!” might well have resounded through its streets on that bleak November morning when Pennington Lawton was found dead, seated quietly in his arm-chair by the hearth in the library, where so many vast deals of national import had been first conceived, and the details arranged which had carried them on and on to brilliant consummation.

Lawton, the magnate, the supreme power in the financial world of the whole country, had been suddenly cut down in his prime.

The news of his passing traveled more quickly than the extras which rolled damp from the presses could convey it through the avenues and alleys of the city, whose wealthiest citizen he had been, and through the highways and byways of the country, which his marvelous mentality and finesse had so manifestly strengthened in its position as a world power.

At the banks and trust companies there were hurriedly-called directors’ meetings, where men sat about long mahogany tables, and talked constrainedly about 2 the immediate future and the vast changes which the death of this great man would necessarily bring. In the political clubs, his passing was discussed with bated breath.

At the hospitals and charitable institutions which he had so generously helped to maintain, in the art clubs and museums, in the Cosmopolitan Opera House––in the founding of which he had been leading spirit and unfailingly thereafter, its most generous contributor––he was mourned with a sincerity no less deep because of its admixture of self-interest.

In aristocratic drawing-rooms, there were whispers over the tea-cups; the luck of Ramon Hamilton, the rising young lawyer, whose engagement to Anita Lawton, daughter and sole heiress of the dead financier, had just been announced, was remarked upon with the frankness of envy, left momentarily unguarded by the sudden shock.

For three days Pennington Lawton lay in simple, but veritable state. Telegrams poured in from the highest representatives of State, clergy and finance. Then, while the banks and charitable institutions momentarily closed their doors, and flags throughout the city were lowered in respect to the man who had gone, the funeral procession wound its solemn way from the aristocratic church of St. James, to the graveyard. The last extras were issued, detailing the service; the last obituaries printed, the final pæans of praise were sung, and the world went on its way.

During the two days thereafter, multitudinous affairs of more imperative public import were brought to light; a celebrated murder was committed; a notorious band of criminals was rounded up; a political boss toppled and fell from his self-made pedestal; a diplomatic scandal of 3 far-reaching effect was unearthed, and in the press of passing events, the fact that Lawton had been eliminated from the scheme of things faded into comparative insignificance, from the point of view of the general public.

In the great house on Belleair Avenue, which the man who was gone had called home, a tall, slender young girl sat listlessly conversing with a pompous little man, whose clerical garb proclaimed the reason for his coming. The girl’s sable garments pathetically betrayed her youth, and in her soft eyes was the pained and wounded look of a child face to face with its first comprehended sorrow.

The Rev. Dr. Franklin laid an obsequious hand upon her arm.

“The Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.”

Anita Lawton shivered slightly, and raised a trembling, protesting hand.

“Please,” she said, softly, “I know––I heard you say that at St. James’ two days ago. I try to believe, to think, that in some inscrutable way, God meant it for the best when he took my father so ruthlessly from me, with no premonition, no sign of warning. It is hard, Dr. Franklin. I cannot coordinate my thoughts just yet. You must give me a little time.”

The minister bent his short body still lower before her.

“My dear child, do you remember, also, a later prayer in the same service?”––unconsciously he assumed the full rich, rounded, pulpit tones, which were habitual with him. “‘Lord, Thou hast been our refuge from one generation to another; before the mountains were brought forth or ever the earth and world were made––’”

A low knocking upon the door interrupted him, and the butler appeared.

“Mr. Rockamore and Mr. Mallowe,” Anita Lawton 4 read aloud from the cards he presented. “Oh, I can’t see them now. Tell them, Wilkes, that my minister is with me, and they must forgive me for denying myself to them.”

The butler retired, and the Rev. Dr. Franklin, at the mention of two of the most prominent and influential men in the city since the death of Lawton, turned bulging, inquiring eyes upon the girl.

“My dear child, is it wise for you to refuse to see two of your father’s best friends? You will need their help, their kindness––a woman alone in the world, no matter how exalted her position, needs friends. Mr. Mallowe is not one of my parishioners, but I understand that as president of the Street Railways, he was closely associated with your dear father in many affairs of finance. Mr. Rockamore I know to be a man of almost unlimited power in the world in which Mr. Lawton moved. Should you not see them? Remember that you are under my protection in every way, of course, but since our Heavenly Father has seen fit to take unto Himself your dear one, I feel that it would be advisable for you to place yourself under the temporal guidance of those whom he trusted, at any rate for the time being.”

“Oh, I feel that they were my father’s friends, but not mine. Since mother and my little sister and brother were lost at sea, so many years ago, I have learned to depend wholly upon my father, who was more comrade than parent. Then, as you know, I met Ramon––Mr. Hamilton, and of course I trust him as implicitly as I must trust you. But although, on many occasions, I assisted my father to receive his financial confrères on a social basis, I cannot feel at a time like this that I care to talk with any except those who are nearest and dearest to me.”

“But suppose they have come, not wholly to offer you consolation, but to confer with you upon some business matters upon which it would be advantageous for you to inform yourself? Your grief and desire for seclusion are most natural, under the circumstances, but one must sometimes consider earthly things also.” The minister’s evidently eager desire to be present at an interview with the great men and to place himself on a more familiar footing with them was so obvious that Anita’s gesture of dissent held also something of repugnance.

“I could not, Dr. Franklin. Perhaps later, when the first shock has passed, but not yet. You understand that I like them both most cordially. Those whom father trusted must be men of sterling worth, but just now I feel as must an animal which has been beaten. I want to creep off into a dark and silent place until my misery dulls a little.”

“You have borne up wonderfully well, dear child, under the severe shock of this tragedy. Mrs. Franklin and I have remarked upon it. You have exhibited the same self-mastery and strength of character which made your father the man he was.” Dr. Franklin arose from his chair with a sigh which was not altogether perfunctory. “Think well over what I have said. Try to realize that your only consolation and strength in this hour of your deepest sorrow come from on High, and believe that if you take your poor, crushed heart to the Throne of Grace it shall be healed. That has been promised us. Think, also, of what I have just said to you concerning your father’s associates, and when next they call, as they will, of course, do very shortly, try to receive them with your usual gracious charms, and should they offer you any advice upon worldly matters, which we must not permit ourselves to neglect, send for me. I will leave 6 you now. Mrs. Franklin will call upon you to-morrow. Try to be brave and calm, and pray for the guidance which will be vouchsafed you, should you ask it, frankly and freely.”

Anita Lawton gave him her hand and accompanied him in silence to the door. There, with a few gentle words, she dismissed him, and when the sound of his measured footsteps had diminished, she closed the door with a little gasp of half relief, and turned to the window. It had been an effort to her to see and talk with her spiritual adviser, whose hypocrisy she had vaguely felt.

If only Ramon had come––Ramon, whose wife she would be in so short a time, and who must now be father as well as husband to her. She glanced at the little French clock on the mantel. He was late––he had promised to be there at four. As she parted the heavy curtains, the telephone upon her father’s desk, in the corner, shrilled sharply. When she took the receiver off the hook, the voice of her lover came to the girl as clearly, tenderly, as if he, himself, stood beside her.

“Anita, dear, may I come to you now?”

“Oh, please do, Ramon; I have been waiting for you. Dr. Franklin called this afternoon, and while he was here with me Mr. Rockamore and Mr. Mallowe came, but I could not see them. There is something I feel I must talk over with you.”

She hung up the receiver with a little sigh, and for the first time in days a faint suspicion of a smile lightened her face. As she turned away, however, her eyes fell upon the great leather chair by the hearth, and her expression changed as she gave an uncontrollable shudder. It was in that chair her father had been found on that fateful morning, about a week ago, clad still in the dinner-clothes of the previous evening, a faint, introspective 7 smile upon his keen, inscrutable face; his eyes wide, with a politely inquiring stare, as if he had looked upon things which until then had been withheld from his vision. She walked over to the chair, and laid her hand where his head had rested. Then, all at once, the tension within her seemed to snap and she flung herself within its capacious, wide-reaching arms, in a torrent of tears––the first she had shed.

It was thus that Ramon Hamilton found her, on his arrival twenty minutes later, and without ado, he gathered her up, carried her to the window-seat, and made her cry out her heart upon his shoulder.

When she was somewhat quieted he said to her gently, “Dearest, why will you insist upon coming to this room, of all others, at least just for a little time? The memories here will only add to your suffering.”

“I don’t know; I can’t explain it. That chair there in which poor father was found has a peculiar, dreadful fascination for me. I have heard that murderers invariably return sooner or later to the scene of their crime. May we not also have the same desire to stay close to the place whence some one we love has departed?”

“You are morbid, dear. Bring your maid and come to my mother’s house for a little, as she has repeatedly asked you to do. It will make it so much easier for you.”

“Perhaps it would. Your mother has been so very kind, and yet I feel that I must remain here, that there is something for me to do.”

“I don’t understand. What do you mean, dearest?”

She turned swiftly and placed her hands upon his broad shoulders. Her childish eyes were steely with an intensity of purpose hitherto foreign to them.

“Ramon, there is something I have not told you or any one; but I feel that the time has come for me to speak. It is not nervousness, or imagination; it is a fact which occurred on the night of my father’s death.”

“Why speak of it, Anita?” He took her hands from his shoulders, and pressed them gently, but with quiet strength. “It is all over now, you know. We must not dwell too much upon what is past; I shall have to help you to put it all from your mind––not to forget, but to make your memories tender and beautiful.”

“But I must speak of it. It will be on my mind day and night until I have told you. Ramon, you dined with us that night––the night before. Did my father seem ill to you?”

“Of course not. I had never known him to be in better health and spirits.” Ramon glanced at her in involuntary surprise.

“Are you sure?”

“Why do you ask me that? You know that heart-disease may attack one at any time without warning.”

Anita sank upon the window-seat again, and leaned forward pensively, her hands clasped over her knees.

“You will remember that after you and father had your coffee and cigars together in the dining-room, you both joined me?”

“Of course. You were playing the piano, ramblingly, as if your thoughts were far away, and you seemed nervous, ill at ease. I wondered about it at the time.”

“It was because of father. To you he appeared in the best of spirits, as you say, but I, who knew him better than any one else on earth, realized that he was forcing himself to be genial, to take an interest in what we were saying. For days he had been overwrought and depressed. 9 As you know, he has confided in me, absolutely, since I have been old enough to be a real companion to him. I thought that I knew all his business affairs––those of the last two or three years at least––but latterly his manner has puzzled and distressed me. Then, while you were in the dining-room, the telephone rang twice.”

“Yes; the calls were for your father. When he was summoned to the wire he immediately had the connection given to him on his private line, here in the library. After he returned to the dining-room he did seem slightly absent-minded, now that I think of it; but it did not occur to me that there could have been any serious trouble. You know, dearest, ever since the evening when he promised to give you to me, he has consulted me, also, to a great extent about his financial interests, and I think if any difficulty had arisen he would have mentioned it.”

“Still, I am convinced that something was on his mind. I tried to approach him concerning it, but he was evasive, and put me off, laughingly. You know that father was not the sort of man whose confidence could be forced even by those dearest to him. I had been so worried about him, though, that I had a nervous headache, and after you left, Ramon, I retired at once. An hour or two later, father had a visitor––that fact as you know, the coroner elicited from the servants, but it had, of course, no bearing on his death, since the caller was Mr. Rockamore. I heard his voice when I opened the door of my room, after ringing for my maid to get some lavender salts. I could not sleep, my headache grew worse; and while I was struggling against it, I heard Mr. Rockamore depart, and my father’s voice in the hall, after the slamming of the front door, telling 10 Wilkes to retire, that he would need him no more that night. I heard the butler’s footsteps pass down the hall, and then I rose and opened my door again. I don’t know why, but I felt that I wanted to speak to father when he came up on his way to bed.”

Anita paused, and Ramon, in spite of himself, felt a thrill of puzzled wonder at her expression, upon which a dawning look, almost of horror, spread and grew.

“But he did not come, and after a while I stole to the head of the stairs and looked down. There was a low light in the hall and a brighter one from the library, the door of which was ajar. I supposed that father was working late over some papers, and I knew that I must not disturb him. I crept back to bed at last, with a sigh, but left my own door slightly open, so that if I should happen to be awake when he passed, I might call to him.

“Presently, however, I dozed off. I don’t know how long I slept, but I awakened to hear voices––angry voices, my father’s and another, which I did not recognize. I got up and by the night-light I saw that the hands of the little clock on my dresser pointed to nearly three o’clock. I could not imagine who would call on father so very late at night, and I feared at first it might be a burglar, but my common sense assured me that father would not stop to parley with a burglar. While I stood wondering, father raised his voice slightly, and I caught one word which he uttered. Ramon, that word sounded to me like ‘blackmail!’ Why, what is it? Why do you look at me so strangely?” she added hastily, at his uncontrollable start.

“I? I am not looking at you strangely, dear; it is not possible that you could have heard aright. It must 11 have been simply a fancy of yours, born of the state of your nerves. You could not really have understood.” But Ramon Hamilton looked away from her as he spoke, with a peculiarly significant gleam in his candid eyes. After a slight pause he went on: “No one in the world could have attempted to blackmail your father. He was the soul of honor and integrity, as no one knows better than you. Why, his opinion was sought on every public question. You remember hearing of some of the political honors which he repeatedly refused, but he could, had he wished, have held the highest office at the disposal of the people. You must have been mistaken, Anita. There has never been a reason for the word ‘blackmail’ to cross your father’s lips.”

“I know that I was not mistaken, for I heard more––enough to convince me that I had been right in my surmise! Father was keeping something from me!”

“Dear little girl, suppose he had been? Nothing, of course, that could possibly reflect upon his integrity,––don’t misunderstand me––but you are only twenty, you know. It is not to be expected that you could quite comprehend the details of all the varied business interests of a man who had virtually led the finances of his country for more than twenty years. Perhaps it was a purely business matter.”

“I tell you, Ramon, that that man, whoever he was, actually dared to threaten father. When I heard that word ‘blackmail’ in the angriest tones which I had ever heard my father use, I did something mean, despicable, which only my culminating anxiety could have induced me to do. I slipped on my robe and slippers, stole half-way downstairs and listened deliberately.”

“Anita, you should not have done that! It was not like you to do so. If your father had wished you to 12 know of this interview, don’t you think he would have told you?”

“Perhaps he would have, but what opportunity was he given? A few hours later, he was found dead in that chair over there; the chair in which he sat while he was talking with his unknown visitor.”

The young man sprang to his feet. “You can’t realize what you are saying; what you are hinting! It is unthinkable! If you let these morbid fancies prey upon your mind, you will be really ill.” His tones were full of horror. “Your father died of heart-disease. The doctors and the coroner established that beyond the shadow of a doubt, you know. Any other supposition is beyond the bounds of possibility.”

“Of heart-disease, yes. But might not the sudden attack have been brought on by his altercation with this man? His sudden rage, controlled as it was, at the insults hurled at him?”

“What insults, Anita? Tell me what you heard when you crept down the stairs. You know you can trust me, dear––you must trust me.”

“The man was saying: ‘Come, Lawton, be sensible; half a loaf is better than no bread. There is no blackmail about this, even if you choose to call it so. It is an ordinary business proposition, as you have been told a hundred times!’”

“‘It’s a damnable crooked scheme, as I have told you a hundred times, and I shall have nothing to do with it! This is final!’ Father’s tones rang out clearly and distinctly, quivering with suppressed fury. ‘My hands are clean, my financial operations have been open and above-board; there is no stain upon my life or character, and I can look every man in the face and tell him to go where you may go now!’

“‘Oh, is that so!’ sneered the other man loudly. Then his voice became insinuatingly low. ‘How about poor Herbert––’ His tones were so indistinct that I could not catch the name. Then he went on more defiantly, ‘His wife––’ He didn’t finish the sentence, Ramon, for father groaned suddenly, terribly, as if he were in swift pain; the man gave a little sneering laugh, and I could hear him moving about in the library, whistling half under his breath in sheer bravado. I could not bear to hear any more. I put my hands over my ears and fled back to my room. What could it mean, Ramon? What is this about father and some other man and his wife which the stranger dared to insinuate! reflected upon father’s integrity? Why should he have groaned as if the very mention of these people hurt him inexpressibly?”

“I don’t know, dear.” Ramon Hamilton sat with his honest eyes still turned from her. “You must have been mistaken; perhaps you even dreamed it all.” Anita Lawton gave an impatient gesture.

“I am not quite the child you think me, Ramon. Could that man have meant to insinuate that father in his own advancement had trod upon and ruined some one else, as financiers have always done? Could he have meant that father had driven this man and his wife to despair? I cannot bear to think of it. I try to thrust it from my thoughts a dozen times a day, but that groan from father’s lips sounded so much like one of remorse that hideous ideas come beating in on my brain. Was my father like other rich men, Ramon? He did not live for money, although the successful manipulation of it was almost a passion with him. He lived for me, always for me, and the good that he would be able to do in this world.”

“Of course he did, darling. No one who knew him could imagine otherwise for a moment.” He hesitated, and then added, “No one else discovered this man’s presence in the house that night? You have told no one? Not the doctor, or the coroner, or Dr. Franklin?”

“Oh, no; if I had it would have been necessary for me to have told what I overheard. Besides, it could have had no direct bearing on daddy’s death; that was caused by heart-disease, as you say. But I believe, and I always will believe, that that man killed father, as surely, as inevitably, as if he had stabbed or shot or poisoned him! Why did he come like a thief in the night? Father’s integrity, his honor, were known to all the world. Why did that reference to this Herbert and his wife cause him such pain?”

“I don’t know, dear; I have no more idea than you. If you really, really overheard that conversation, as you seem convinced you did, you did well in keeping it to yourself. Let that hour remain buried in your thoughts, as in your father’s grave. Only rest assured that whatever it is, it casts no stain upon your father’s good name or his memory.” He rose and gathered her into his arms. “I must go now, Anita; I’ll come again to-morrow. You are quite sure that you will not accept my mother’s invitation? I really think it would be better for you.”

She looked deeply into his eyes, then drew herself gently from his clasp. “Not yet. Thank her for me, Ramon, with all my heart, but I will not leave my father’s house just yet, even for a few days. I am sure that I shall be happier here.” He kissed her, and left the room. She stood where he had left her until she heard the heavy thud of the front door. Then, turning 15 to the window, she thrust her slim little hand between the sedately drawn curtains, and waved him a tender good-by; then with a little sigh, she dropped among the pillows of the couch, lost in thought.

“Whatever was meant by that conversation which I overheard,” she murmured to herself, “Ramon knows. I read it in his eyes.”

The young man, as he made his way down the crowded avenue, was turning over in his mind the extraordinary story which the girl he loved had told him.

“What could it mean? Who could the man have been? Surely not Herbert himself, and yet––oh! why will they not let sleeping dogs lie; why must that old scandal, that one stain on Pennington Lawton’s past have been brought again to light, and at such a time? I pray God that Anita never mentions it to anyone else, never learns the truth. By Jove, if any complications arise from this, there will be only one thing for me to do. I must call upon the Master Mind.”

For two days Anita wandered wraithlike about the great darkened house. The thought that Ramon was keeping something from her––that he and her dead father together had kept a secret which, for some reason, must not be revealed to her, weighed upon her spirits. Conjectures as to the unknown intruder on the night of her father’s death, and his possible purpose, flooded her mind to the exclusion of all else.

In the dusk of the winter afternoon she was lying on the couch in her dressing-room, lost in thought, when Ellen, tapping lightly at the door, interrupted her reverie.

“The minister, Miss Anita––the Rev. Dr. Franklin––he is in the drawing-room.”

“Oh!” Anita gave a little movement of dismay. “Tell him that I am suffering from a very severe headache, and gave orders that I was not to be disturbed by anyone. He means well, Ellen, of course, but he always depresses me horribly, lately. I don’t feel like talking to him this afternoon.”

The maid retired, but returned again almost immediately with a surprised, half-frightened expression on her usually stolid face.

“Please, Miss Anita, Dr. Franklin says he must see you and at once. He seems to be excited and he won’t take no for an answer.”

“Ramon!” Anita cried, springing from the couch 17 with swift apprehension. “Something has happened to Ramon, and Dr. Franklin has come to tell me. He may be injured, dead! Ah, God would not do that; He would not take him from me, too!”

“Don’t take on so, Miss Anita, dear,” the faithful Ellen murmured, as she deftly smoothed the girl’s hair and rearranged her gown; “the little man acts more as if he had a fine piece of gossip to pass on––fidgeting about like an old woman, he is. Begging your pardon, Miss, I know he is the minister, of course, and I ought to show him more respect, but he forever reminds me of a fat black pigeon.”

The remarks of the privileged old servant fell upon deaf, unheeding ears. Anita, sobbing softly beneath her breath, flew down to the drawing-room, where the pompous black-cloaked figure rose at her entrance. But––was it purely Anita’s fancy or had some indefinable change actually taken place in the manner of her spiritual adviser? The rather close-set eyes seemed to the girl to gleam somewhat coldly upon her, and although he took both her hands in his in quick, fatherly greeting, his hand-clasp appeared all at once to be lacking in warmth.

“My poor child, my poor Anita!” he began unctuously, but she interrupted him.

“What is it, Dr. Franklin? Has something happened to Ramon?” she asked swiftly. “Please tell me! Now, without delay! Don’t keep me in suspense. I can tell by your face, your manner, that a new misfortune has come to me! Does it concern Ramon?”

“Oh, no; it is not Mr. Hamilton. You need have no fears for him, Anita. I have come upon a business matter––a matter connected with your dear father’s estate.”

Anita motioned him to a chair. Seating herself opposite, she gazed at him inquiringly.

“The settlement of the estate? Oh, the lawyers are attending to that, I believe.” Anita spoke a little coldly. Had Dr. Franklin come already to inquire about a possible legacy for St. James’?

She was ashamed of the thought the next moment, when he said gently, “Yes, but there is something which I must tell you. It has been requested that I do so. It is a delicate matter to discuss with you, but surely no one is more fitted to speak to you than I.”

“Certainly, Doctor, I understand.” She leaned forward eagerly.

“My dear, you know the whole country, the whole world at large, has always considered your father to have been a man of great wealth.”

“Yes. My father’s charities alone, as you are aware, unostentatiously as they were conducted, would have tended to give that impression. Then his tremendous business interests––”

“Anita, at the moment of your father’s death he was far from being the King of Finance, which the world judged him to be. It is hard for me to tell you this, but you must know, and you must try to believe that your Heavenly Father is sending you this added trial for some sure purpose of His own. Your father died a poor man, Anita. In fact, a bankrupt.” The girl looked up with an incredulous smile.

“Dr. Franklin, who could ever have asked you to come to me with such an incredible assertion? Surely, you must know how preposterous the very idea is! I do not boast or brag, but it is common knowledge that my father was the richest man in the city, in this entire part of the country, in fact. The thought of such a 19 thing is absurd. Who could have attempted to perpetrate such a senseless hoax, a ridiculous insult to your intelligence and mine?”

The minister shook his head slowly.

“‘Common knowledge’ is, alas, not always trustworthy. It is only too true that your father stood on the verge of bankruptcy. His entire fortune has been swept away.”

“Impossible!”

Anita started from her chair, impressed in spite of herself. “How could that be? Who has told you this terrible thing?”

“The unfortunate news was disclosed to me confidentially by your late father’s truest friends and closest associates. Having your best interests at heart, they feel that you should know the state of affairs at once, and came to me as the one best fitted to inform you.”

“I cannot believe it!” Anita Lawton sank back with white, strained face. “I cannot believe that it is true. How could such a thing have happened? They must be mistaken––those who gave you such information. Father was worth millions, at least. That I know, for he told me much of his business affairs and up to the last day of his life he was engaged in tremendous deals of almost national importance.”

“Might he not have become so deeply involved in one of them that he could not extricate himself, and ruin came?” Dr. Franklin insinuated. “I know little of finance, of course; and those who wished you to know gave me none of the details beyond the one paramount fact.”

“I know, of course, who were your informants,” Anita said. “No one except my father’s three closest associates had any possible conception of how much he 20 possessed, even approximately, for he was always secretive and conservative in his dealings. Only to Mr. Mallowe, Mr. Rockamore and Mr. Carlis did he ever divulge his plans to the slightest extent. A bankrupt! My father a bankrupt? The very words seem meaningless to me. Dr. Franklin, there must be some hideous mistake.”

“Unfortunately, it is no mistake, my poor child. These gentlemen you mention, I may admit to you in confidence, were my informants.”

“You say they gave you no details beyond the paramount fact of my father’s ruin? But surely they must have told you something more. I have a right to know, Dr. Franklin, and I shall not rest until I do. How did such a catastrophe come to him? There have been no gigantic failures lately, no panics which could have swept him down. What terrible mistake could he have made, he whose judgment was almost infallible?”

The minister hesitated visibly, and when he spoke at last, it was as if with a conscious effort he chose his words.

“I do not think it was any sudden collapse of some project in which he was engaged, Anita, but a––a general series of misfortunes which culminated by forcing him, just before his death, to the brink of bankruptcy. You are a mere child, my dear, and could not be supposed to understand matters of finance. If you will be guided by me you will accept the assurance of your friends who truly have your best interests at heart. Their statements will be confirmed, I know, by the lawyers who are engaged in settling up the estate of your father. Do not, I beg of you, inquire too closely into the details of your father’s insolvency.”

Anita rose slowly, her eyes fixed upon the face of the 21 minister, and with her hands resting upon the chair-back, as if to steady herself, she asked quietly:

“Why should I not? What is there which I, his daughter, should not know? Dr. Franklin, there is something behind all this which you are trying to conceal from me. I knew my father to be a multi-millionaire. You come and tell me he was a pauper instead, a bankrupt; and I am not to ask how this state of affairs came about? You have known me since I was a little girl––surely you understand me well enough to realize that I shall not rest under such a condition until the whole truth is revealed to me!”

“I am your friend.” The resonance in the minister’s voice deepened. “You will believe me when I tell you that it would be best for your future, for the honor of your father’s memory, to place yourself without question in the hands of your true friends, and to ask no details which are not voluntarily given you.”

“‘Best for my future!’” she repeated, aghast. “‘For the honor of my father’s memory.’ What do you mean, Dr. Franklin? You have gone too far not to speak plainly. Do you dare––are you insinuating, that there was something disgraceful, dishonorable about my father’s insolvency? You have been my spiritual adviser nearly all my life, and when you tell me that my father was a bankrupt, that the knowledge comes to you from his best friends and will be corroborated by his attorneys, I am forced to believe you. But if you attempt to convince me that my father’s honor––his good name––is involved, then I tell you that it is not true! Either a terrible mistake has been made or a deliberate conspiracy is on foot––the blackest sort of conspiracy, to defame the dead!”

“My dear!” The minister raised his hands in 22 shocked amazement. “You are beside yourself, you don’t know what you are saying! I have repeated to you only that which was told to me, and in practically the same words. As to the possibility of a conspiracy, you will realize the absurdity of such an idea when I deliver to you the message with which I was charged. Your father’s partner in many enterprises, the Honorable Bertie Rockamore, together with President Mallowe, of the Street Railways, and Mr. Carlis, the great politician, promised some little time ago that they would stand in loco parentis toward you should your natural protector be removed. They desire me to tell you that you need have no anxiety for the immediate future. You will be cared for and provided with all that you have been accustomed to, just as if your father were alive.”

“Indeed? They are most kind––” Anita spoke quietly enough, but with a curiously dry, controlled note in her voice which reminded the minister of her father’s tones, and for some inexplicable reason he felt vaguely uncomfortable. “Please say to them that I do sincerely appreciate their magnanimity, their charity, toward one who has no right, legal or moral, to claim protection or care from them. But now, Dr. Franklin, may I beg that you will forgive me if I retire? The news you have brought me of course has been a terrible shock. I must have time to collect my thoughts, to realize the sudden, terrible change this revelation has made in my whole life. I am deeply grateful to you, to my father’s three associates, but I can say no more now.”

“Of course, dear child.” Dr. Franklin patted her hand perfunctorily and arose with ill-concealed relief that the interview was at an end. He could not understand her attitude of the last few moments and it 23 troubled him vaguely. She had received the news of her father’s bankruptcy with a girlish horror and incredulousness––which had been only natural under the circumstances; but when it was borne in upon her, in as delicate a way as he could convey it, that dishonor was involved in the matter, she had, after the first outburst, maintained a stony, ashen self-poise and control that were far from what he had expected. It was the most disagreeable task he had performed in many a day and he was heartily glad that it was over. Only his very great desire to ingratiate himself with these kings of finance, who had commissioned him to do their bidding, as well as the inclination to be of real service to his young and orphaned parishioner, had induced him to undertake the mission.

“You must rest and have an opportunity to adjust yourself to this new, unfortunate state of affairs,” he continued. “I will call again to-morrow. If I can be of the slightest service to you, do not hesitate to let me know. It is a sad trial, but our Heavenly Father has tempered the wind to the shorn lamb; He has provided you with a protector in young Mr. Hamilton, and with kind, true friends who will see that no harm or deprivation comes to you. Try to feel that this added grief and trouble will, in the end, be for the best.”

The alacrity with which he took his departure was painfully obvious, but Anita scarcely noticed it. Her mind was busy with the new, hideous thought, which had assailed her at that first hint of dishonesty on the part of her father––the thought that she was being made the victim of a gigantic conspiracy.

As soon as she found herself alone, she flew to the telephone. “Main, 2785,” she demanded.... “Mr. Hamilton, please.... Is that you, Ramon?... Can 24 you come to me at once? I need your advice and help. Something has happened––something terrible! No, I cannot tell you over the ’phone. You will come at once? Yes, good-by, Ramon dear.”

She hung up the receiver and paced the floor restlessly. Almost inconceivable as it had appeared to her consciousness under the first shock of the announcement, she might in time have come to accept the astounding fact of her father’s insolvency, but that disgrace, dishonor, could have attached itself to his name––that he, the model of uprightness, of integrity could have been guilty of crooked dealing, of something which must for the honor of his memory be kept secret from the ears of his fellow-men, she could never bring herself to believe. Every instinct of her nature revolted, and underlying all her girlish unsophistication, a native shrewdness, inherited perhaps from her father, bade her distrust alike the worldly, self-interested pastor of the Church of St. James and the three so-called friends, who, although her father’s associates, had been his rivals, and who had offered with such astounding magnanimity to stand by her.

Why had they offered to help her? Was it really through tenderness and affection for her father’s daughter, or was it to stay her hand and close her mouth to all queries?

Why did not Ramon come? Surely he should have been there before this. What could be detaining him? She tried to be patient, to calm her seething brain while she waited, but it was no use. Hours passed while she paced the floor, restlessly, and the dusk settled into the darkness of early winter. Wilkes came to turn on the lights, but she refused them––she could think better in the dark. The dinner-hour came and went and twice 25 Ellen knocked anxiously upon the door, but Anita, torn with anxiety, would pay no heed. She had telephoned to Ramon’s office, only to find that he had left there immediately upon receiving her message; to his home––he had not returned.

Nine o’clock sounded in silvery chimes from the clock upon the mantel; then ten and eleven and at length, just when she felt that she could endure no more, the front door-bell rang. A well-known step sounded upon the stairs, and Ramon entered.

With a little gasp of joy and relief she flung herself upon him in the darkness, but at an involuntary groan from him she recoiled.

“What is it, Ramon? What has happened to you?”

Without waiting for a reply she switched on the light.

Ramon stood before her, his face pale, his eyes dark with pain. One arm was in a sling and the thick hair upon his forehead barely concealed a long strip of plaster.

“Nothing really serious, dear. I had a slight accident––run down by a motor-car, just after leaving the office. My head was cut and I was rather knocked out, so they took me to a hospital. I would have come before, but they would not allow me to leave. I knew that you would be anxious because of my delay in coming, but I feared to add to your apprehension by telephoning to you from the hospital.”

“But your arm––is it sprained?”

“Broken. I had a nasty crash––can’t imagine how it was that I didn’t see the car coming in time to avoid it. It was a big limousine with several men inside, all singing and shouting riotously, and the chauffeur, I think, must have been drunk, for he swerved the car directly across the road in my path. They never 26 stopped after they had bowled me over, and no one seemed to know where they went.”

“Then the police did not get their number?”

“No, but they will, of course. Not that I care, particularly; I’m lucky to have got off as lightly as I did. I might have been killed.”

“It was a miracle that you were not, Ramon. Do you know what I believe? I don’t think it was any accident, but a deliberate attempt to assassinate you; to keep you from coming to me.”

“What nonsense, dear! They were a wild, hilarious party, careless and irresponsible. Such accidents happen every day.”

“I am convinced that it was no accident. Ramon, I feel that I am to be the victim of a conspiracy; that you are the only human being who stands in the way of my being absolutely in the power of those who would defraud me and defame father’s name.”

“Anita, what do you mean?”

“Dr. Franklin called upon me this afternoon; he left just before I telephoned to you. He told me an astonishing piece of news. Ramon, would you have considered my father a rich man?”

“What an absurd question, dear! Of course. One of the richest men in the whole country, as you know.”

“You say that he consulted you about his business affairs, and that you knew of no trouble or difficulty which could have caused him anxiety? His securities in stocks and bonds, his assets were all sound?”

“Certainly. What do you mean?”

“I mean that my father died a pauper! That on the word of Mr. Rockamore, Mr. Mallowe, Mr. Carlis and Dr. Franklin, he was on the verge of dishonorable bankruptcy, into which I may not inquire.”

“Good Heavens, they must be mad! I am sure that your father was at the zenith of his successful career, and as for dishonor, surely, Anita, no one who knew him could credit that!”

“Mr. Rockamore and the other two who were so closely associated with him made a solemn promise to my father shortly before his death, it seems, that they would care for and provide for me. They sent Dr. Franklin to me this afternoon to explain the circumstances to me, and to assure me of their protection. Save for you, they consider me absolutely in their hands; and when I sent for you, you were almost killed in the attempt to come to me. Ramon, don’t you see, don’t you understand, there is some mystery on foot, some terrible conspiracy? That unknown visitor, my father’s death so soon after, and now this sudden revelation of his bankruptcy, together with this accident to you? Ramon, we must have advice and help. I do not believe that my father was a pauper. I know that he has done nothing dishonorable; I am convinced that the accident to you was a premeditated attempt at murder.”

“My God! I can’t believe it, Anita; I don’t know what to think. If it turns out that there really is something crooked about it all, and Rockamore and the others are concerned in it, it will be the biggest conspiracy that was ever hatched in the world of high finance. You were right, dear, bless your woman’s intuition; we must have help. This matter must be thoroughly investigated. There is only one man in America to-day, who is capable of carrying it through, successfully. I shall send at once for the Master Mind.”

“The Master Mind?”

“Yes, dear––Henry Blaine, the most eminent detective the English-speaking world has produced.”

“I have heard of him, of course. I think father knew him, did he not?”

“Yes, on one occasion he was of inestimable service to your father. I will summon him at once.”

Ramon went to the telephone and by good luck found the detective free for the moment and at his service.

He returned to the girl. She noticed that he reeled slightly in his walk; that his lips were white and set with pain.

“Ramon, you are ill, suffering. That cut on your head and your poor arm––”

“It is nothing. I don’t mind, Anita darling; it will soon pass. Thank Heavens, I found Mr. Blaine free. He will get to the truth of this matter for us even if no one else on earth could. He has brought more notorious malefactors to justice than any detective of modern times; fearlessly, he has unearthed political scandals which lay dangerously close to the highest executives of the land. He cannot be cajoled, bribed or intimidated; you will be safe in his hands from the machinations of every scoundrel who ever lived.”

“I have read of some of his marvelous exploits, but; what service was it that he rendered to my father?”

“I––I cannot tell you, dearest. It was very long ago, and a matter which affected your father solely. Perhaps some time you may learn the truth of it.”

“I may not know! I may not know! Why must I be so hedged in? Why must everything be kept from me? I feel as if I were living in a maze of mystery. I must know the truth.”

She wrung her hands hysterically, but he soothed her and they talked in low tones until Wilkes suddenly appeared in the doorway and announced:

“Mr. Henry Blaine!”

A man stood upon the threshold: a man of medium height, with sandy hair and mustache slightly tinged with gray. His face was alert and keenly intelligent. His eyes shrewd, but kindly, the brows sloping downward toward the nose, with the peculiar look of concentration of one given to quick decisions and instant, fearless action.

His eyes traveled quickly from the young girl’s face to Ramon Hamilton, as the latter advanced with outstretched hand.

“Mr. Blaine, it was fortunate that we found you at liberty and able to assist us in a matter which is of vital importance to us both. This is Miss Anita Lawton, daughter of the late Pennington Lawton, who desires your aid on a most urgent matter.”

“Miss Lawton.” Mr. Elaine bowed over her hand.

When they were seated she said, shyly: “I understand from Ramon––Mr. Hamilton––that you were at one time of great service to my father. I trust that you will be able to help me now, for I feel that I am in the meshes of a conspiracy. You know that my father died suddenly, almost a week ago.”

“Yes, of course. His death was a great loss to the whole country, Miss Lawton.”

“Something occurred a few hours before his death, 30 of which even the coroner is unaware, Mr. Blaine. I told Mr. Hamilton what I knew, but he advised me to say nothing of it, unless further developments ensued.”

“And they have ensued?” the detective asked quietly.

“Yes.”

Anita then detailed to Mr. Blaine the incident of her father’s nocturnal visitor. As she told him the conversation she had overheard, it seemed to her that the eyes of the detective narrowed slightly, but no other change of expression betrayed the fact that the incident might have held a significance in his mind.

“The voice was entirely strange to you?” he asked.

“Yes; I have never heard it before, but it made such an impression upon me that I think I would recognize it instantly whenever or wherever I might happen to hear it.”

“You caught no glimpse of the man through the half-opened door?”

“No, I was not far enough downstairs to see into the room.”

“And when you fled, after hearing your father groan, you returned immediately to your room?”

“Yes. I closed my door and buried my face deeply in the pillows on my bed. I did not want to hear or know any more. I was frightened; I did not know what to think. After a time I must have drifted off into an uneasy sort of sleep, for I knew nothing more until my maid came to tell me that Wilkes, the butler, wished to speak to me. My father had been found dead in his chair. No one in the household seemed to know of my father’s late visitor, for they made no mention of his coming. I would have told no one, except Ramon, but for the fact that this afternoon my minister informed me that my father, instead of being the multi-millionaire 31 we had all supposed him, had in reality died a bankrupt.”

The detective received this information with inscrutable calm. Only by a thoughtful pursing of his lips did he give indication that the news had any visible effect upon him.

Anita continued, giving him all the details of the minister’s visit, and the magnanimous promise of her father’s three associates to stand in loco parentis toward her.

It was only when she told of summoning her lover, and the accident which befell him on his way to her, that that peculiar gleam returned again to the eyes of Mr. Blaine, and they glanced narrowly at the young man opposite him.

“As I told Ramon, I cannot help but feel that it is not true. My father could not have become a pauper, much less could he, the soul of honor, have been guilty of anything derogatory to his good name. Until a few days prior to his death, he had been in his usual excellent spirits, and surely had there been any financial difficulties in his path he would have retrenched, in some measure. He made no effort to do so, however, and in the last few weeks has given even more generously than usual to the various philanthropic projects in which he was so interested. Does that look as if he was on the verge of bankruptcy? He bought me a string of pearls on my birthday, two months ago, which for their size are considered by experts to be the most perfectly matched in America. A fortnight ago, he presented me with a new car. Only three days before his death he spoke of an ancient château in France which he had desired to purchase. Oh, the whole affair is utterly inexplicable to me!”

“We will take the matter up at once, Miss Lawton. The main thing that I must impress upon you for the present is to acquiesce with the utmost docility and unsuspicion in every proposition made to you by the three men, Carlis, Mallowe and Rockamore; in other words, place yourself absolutely in their hands, but keep me informed of every move they make. You understand that the most important factor in this case is to keep them absolutely unsuspecting of your distrust, or that you have called me to your assistance. I must not be seen coming here or to Mr. Hamilton’s office, nor must you come to mine. I will have a private wire installed for you to-morrow morning, by means of which you can communicate with me, or one of my operatives, at any hour of the day or night, in the presence of anyone. This telephone will connect only with my office, but the number will be, supposedly, that of your dressmaker, and if you require aid, advice, or the presence of one of my operatives, you have merely to call up the number and say: ‘Is my gown ready? If it is, please send it around immediately.’ Let me know through this medium whatever occurs, and take absolutely no one into your confidence.”

“I understand, Mr. Blaine; and I will try to follow your instructions to the letter. Oh, by the way, there is something I wish to tell you, which no one, not even Mr. Hamilton, knows, much less my father’s friends, or my minister. Four years ago, my father financed a philanthropic venture of mine, the Anita Lawton Club for Working Girls. It is not a purely charitable institution, but a home club, where worthy young women could live by paying a nominal sum––merely to preserve their self-respect––and be aided in obtaining positions. Stenographers, telephone and telegraph operators, 33 clerks, all find homes there. No one knew, however, that under my management, the club grew in less than a year not only to have paid for itself, but to have yielded a small income, over and above expenses. I did not tell my father––I don’t know why, perhaps it was because I inherited a little of his business acumen, but I manipulated the net income in various minor undertakings, even in time buying small plots of unimproved real-estate, meaning after a year or two more to surprise my father with the result of my venture, but his death intervened before I could tell him about it.”

“Your father’s associates, then, believe you to be without funds or private income of your own?” the detective asked.

“Yes, Mr. Blaine. And whatever money is necessary for the investigation, will, of course, be forthcoming from this source.”

“Let me strongly advise you to make no mention of it to anyone else; let these men believe you to be utterly within their power financially. And now, Miss Lawton, I will leave you, for I have work to do.” The detective rose. “The private wire will be installed to-morrow morning. Remember to be absolutely unsuspicious, to appear deeply grateful for the kindness offered you; receive these men and your spiritual adviser whenever they call, and above all, keep me informed of everything that occurs, no matter how insignificant or irrelevant it may seem to you to be. Keep me advised on even the smallest details––anything, everything concerning you and them.”

Thus it was, that when two days later, President Mallowe of the Street Railways, called upon his new ward, she received him with downcast eyes, and a charmingly deferential manner. His long-nosed, heavy-jowled 34 face, with the bristling gray side-whiskers, flushed darkly when she placed her trembling little hand in his and shyly voiced her gratitude for his great kindness to her.

“My dear young lady, this has been a most sad and unfortunate affair, but I have come to assure you again of the sentiments of myself and my associates toward you. We come, your self-appointed guardians; we will see that no financial worriments shall come to you. Remember, my dear, that I have three married daughters of my own, and I could not permit the child of my old friend to want for anything. You may remain on here in this house, which has been your home, indefinitely, and it will be maintained for you in the manner to which you have always been accustomed.”

“Remain here in my home?” Anita stammered. “Why it––it is my home, isn’t it?”

“You must consider it as such. I do not like to tell you this, but it is necessary that you should know. I hold a mortgage of eighty thousand dollars on the house, but I have never recorded it, because of my friendship and close affiliation with your father. I shall not have it recorded now, of course, but there is a slight condition, purely a matter of business, which in view of the fact that through your coming marriage you will have a home of your own, Mr. Rockamore, Mr. Carlis and myself, feel that we should agree upon. Your father has a shadowy interest in some old bonds which have for years been unremunerative. Should they prove of ultimate value, we feel that they should be transferred to us as our reimbursement for the present large sum which we shall lay out for you.”

“Of course, Mr. Mallowe. That would only be just. I am glad that I may perhaps have an opportunity to 35 repay some of the kindness which in your great-hearted charity, you are now bestowing upon me. I will see that my father’s attorneys attend to the matter, as soon as possible. It may be some little time before the estate is settled, as of course it must be horribly complicated and involved, but I will bring this to their immediate attention.”

“You are a very brave young woman, Miss Lawton, and I am glad that you are taking such a clear-sighted view of this double catastrophe which has come upon you. Ah, I had almost forgotten; here is a duplicate of the mortgage which I hold upon this house, which your father made out to me some months ago.”

Anita scarcely glanced at it, but laid it quietly by upon the table, as though it were of small interest to her.

“Mr. Mallowe, although I understand that Mr. Rockamore, being a promoter, was more closely associated with my father in various projects than you, I believe that he always considered you his best friend. Can you tell me what it was which brought my father’s affairs to such a pass as this?”

“Dear young lady, do not ask me. It is a painful subject to discuss, and as you are a mere child, you cannot be supposed to understand the financial manœuvres of a man of your father’s passion for gigantic operations. Years of success had possibly made him overconfident; and then you know, we are none of us infallible; we are liable to make mistakes, at one time or another. Your father interested himself daringly in many schemes which we more conservative ones would have hesitated to enter; indeed, we not only hesitated, but repeatedly declined when your father placed the propositions before us. As you know, unfortunately, 36 he was a man who would have resented any attempt at advice, and although for a long time we have seen his approaching financial downfall, and have helped him in every way we could to avert it, he would not relinquish his plans while there was yet time. Do not ask me to go into any further details. It is really most distressing. Your father’s attorneys will understand the matter fully when the estate is finally settled.”

“I cannot understand it,” Anita murmured. “I thought my father’s judgment almost infallible. However, Mr. Mallowe, I cannot express my gratitude to you and my father’s other associates for your great kindness toward me. Believe me, I am deeply affected by it. I shall never forget what you have done.”

“Do not speak of it, dear Miss Lawton. I only wish for your sake that your poor father had heeded poorer heads than his, but it is too late to speak of that now. We will do all in our power to aid you, rest assured of that. Should you require anything, you have only to call upon Mr. Rockamore, Mr. Carlis or myself.”

When he had bowed himself out, Anita flew to the table, seized the duplicate of the mortgage which he had given her, and slipped it between the pages of a book lying there. Then she went directly to her dressing-room where on a little stand near her bed reposed a telephone instrument which had not been there three days previously.

“Grosvenor 0760,” she demanded, and when a voice replied to her at the other end of the wire, she asked querulously, “Is not my new gown ready yet? If it is, will you kindly send it over at once? I have also found your last quarterly bill, and I think there is something wrong with it. I will send it back by the messenger, who brings my gown. Thank you; good-by.”

She took an envelope from the desk and returning to the drawing-room slipped the duplicate mortgage within it and sealed it carefully.

When, a few minutes later, a tall, dark, stolid-faced young man appeared, with a large dressmaker’s box, she placed the envelope in his hand.

“For Mr. Blaine,” she whispered. “See that it reaches him immediately.”

A half hour afterward, Ramon Hamilton went to the telephone in his office, and heard the detective’s voice over the wire.

“Mr. Hamilton, have you among the letters and documents at your office the signature of the person we were discussing the other day?”

“Why, yes, I think so. I will look and see. If I have do you wish me to send it around to you?”

“No, thank you. A messenger boy will call for it in a few minutes.”

Wondering, Ramon Hamilton shuffled hastily through the paper in the pigeon-holes of his desk until he came to a letter from Pennington Lawton. He carefully tore off the signature, and when the messenger boy appeared, gave it to him. He would not have been so puzzled, had he seen the great Henry Blaine, when a few minutes had elapsed, seated before the desk in his office, comparing the signature of the torn slip which he had sent with that affixed to the duplicate mortgage.

A long, close, breathless scrutiny, with the most powerful magnifying glasses, and the detective jumped to his feet.

“That’s no signature of Pennington Lawton,” he exulted to himself. “I thought I knew that fine hand, perfectly as the forgery has been done. That’s the work of James Brunell, by the Lord!”

Henry Blaine, the man of decision, wasted no time in vain thought. Instantly, upon his discovery that the signature of Pennington Lawton had been forged, and that it had been done by an old and well-known offender, he touched the bell on his desk, which brought his confidential secretary.

“Has Guy Morrow returned yet from that blackmail case in Denver?”

“Yes, sir. He’s in his private office now, making out his report to you.”

A moment later, there entered a tall, dark young man, strong and muscular in build, but not apparently heavy, with a smooth face and firm-set jaw.

“I haven’t finished my report yet, sir––”

“The report can wait. You remember James Brunell, the forger?”

“James Brunell?” Morrow repeated. “He was before my time, of course, but I’ve heard of him and his exploits. Pretty slick article, wasn’t he! I understand he has been dead for years––at least nothing has been heard of his activities since I have been in the sleuth game.”

“Did you ever hear of any of his associates?”

“I can’t say that I have, sir, except Crimmins and Dolan; Crimmins died in San Quentin before his time was up; Dolan after his release went to Japan.”

“I want to find Brunell. His closest associate was Walter Pennold. I think Pennold is living somewhere in Brooklyn, and through him you may be able to locate Brunell––”

Morrow shrugged his shoulders.

“A retired crook in the suburbs. That’s going to take time.”

“Not the way we’ll work it. Listen.”

The next morning, a tall, dark young man, strong and muscular in build, with a smooth face and firm-set jaw, appeared at the Bank of Brooklyn & Queens, and was immediately installed as a clerk, after a private interview with the vice-president.

His fellow clerks looked at him askance at first, for they knew there had been no vacancy, and there was a long waiting list ahead of him, but the young man bore himself with such a quiet, modest air of camaraderie about him that by the noon hour they had quite accepted him as one of themselves.

During the morning a package came to the bank and a letter which read in part:

... I am returning these securities to you in the hope that you may be able to place them in the possession of Jimmy Brunell. They belong to him, and my conscience is responsible for their return. I don’t know where to find him. I do know that at one time he did some banking at the Brooklyn & Queens Institution. If he does not do so now, kindly hold these securities for Jimmy Brunell until called for, and in the meantime see Walter Pennold of Brooklyn.

With the package and letter came a request from Henry Blaine which those in power at the Brooklyn & Queens Bank were only too glad to accede to, in order to ingratiate themselves with the great investigator.

In accordance with this request, therefore, the affair was made known by the bank-officials to the clerks as a 40 matter of long standing which had only just been rediscovered in an old vault, and the subordinates discussed it among themselves with the gusto of those whose lives were bounded by gilt cages, and circumscribed by rules of silence. It was not unusual, therefore, that the new clerk, Alfred Hicks, should have heard of it, but it was unusual that he should find it expedient to make a detour on his way to work the next morning which would take him to the gate of Walter Pennold’s modest home. Perhaps the fact that Alfred Hicks’ real name was Guy Morrow and that a letter received early that morning from Henry Blaine’s office, giving Pennold’s address and a single line of instruction may have had much to do with his matutinal visit.

Be that as it may, Morrow, the dapper young bank-clerk, found in the Pennold household a grizzled, middle-aged man, with shifty, suspicious eyes and a moist hand-clasp; behind him appeared a shrewish, thin-haired wife who eyed the intruder from the first with ill-concealed animosity.

He smiled––that frank, winning smile which had helped to land more men behind the bars than the astuteness of many of his seniors––and said: “I’m a clerk in the Brooklyn & Queens Bank, Mr. Pennold, and we have a box of securities there evidently belonging to one Jimmy Brunell. No one knows anything about it and no note came with it except a line which read: ‘Hold for Jim Brunell. See Walter Pennold of Brooklyn.’ Now you’re the only Walter Pennold who banks with the B. & Q. and I thought you might like to know about it. There are over two hundred thousand dollars in securities and they have evidently been left there by somebody as conscience-money. You can go to the bank and see the people about it, of course. In fact, I understand 41 they are going to write you a letter concerning it, but I thought you might like to know of it in advance. In case this Mr. Brunell is alive, they will pay him the money on demand, or if dead, to his heirs after him.”

The middle-aged man with the shifty eyes spat cautiously, and then, rubbing his stubby chin with a hairy, freckled hand, observed:

“Well, young man, I’m Pennold, all right. I do some business with the Brooklyn & Queens people––small business, of course, for we poor honest folk haven’t the money to put in finance that the big stock-holders have. I don’t know where you can find this man Brunell, haven’t heard of him in years, but I understand he went wrong. Ain’t that so, Mame?”

The hatchet-faced woman nodded her head in slow and non-committal thought.

Pennold edged a little nearer his unknown guest and asked in a tone of would-be heartiness. “And what might your name be? You’re a bright-looking feller to be a bank-clerk––not the stolid, plodding kind.”

Morrow chuckled again.

“My name is Hicks. I live at 46 Jefferson Place. It’s only a little way from here, you know.” He swung his lunch-box nonchalantly. “Of course, bank-clerking don’t get you anywhere, but it’s steady, such as it is, and I go out with the boys a lot.” He added confidentially: “The ponies are still running, you know, even if the betting-ring is closed––and there are other ways––” He paused significantly.

“I see, a sport, eh?” Pennold darted a quick glance at his wife. “Well, don’t let it get the best of you, young feller. Remember what I told you about Jimmy Brunell––at least, what the report of him was. If I hear anything of where he is, I’ll let the bank know.”

“I’ll be getting on; I’m late now––” Morrow paused on the bottom step of the little porch and turned. “See you again, Mr. Pennold, and your wife, if you’ll let me. I pass by here often––I’ve been boarding with Mrs. Lindsay, on Jefferson Place, for some time now. By the way, have you seen the sporting page of the Gazette this morning? Al Goetz edits it, you know, and he gives you the straight dope. There’ll be nothing to that fight they’re pulling off Saturday night at the Zucker Athletic Club––Hennessey’ll put it all over Schnabel in the first round. Good-by! If you hear anything of this Brunell, be sure you let me or the bank know!”

For a long moment after his buoyant stride had carried him out of sight around the corner, Walter Pennold and his wife sat in thoughtful silence. Then the woman spoke.

“What d’ye think of it all, Wally?”

“Dunno.” The gentleman addressed drew from his pocket a blackened, odoriferous pipe and sucked upon it. “Must be some lay, of course. I’ll go up to the bank and find out what I can, but I don’t think that young feller, Hicks, is in on it. I’ve been in the game for forty years, and if I’m a judge, he’s no ’tec. Fool kid spendin’ more’n he earns and out for what coin he can grab. I’ll look up that landlady of his, too, Mame; and if he’s on the level there, and at the bank––”

“And if those securities are at the bank, he ought to be willin’ to come in with us on a share,” the wife supplemented shrewdly. “But it seems like some kind of a gag to me. You knew all Jimmy Brunell’s jobs till he got religion or somethin’, and turned honest––I can’t think of any old crook who’d turn over that money to him, two hundred thousand cold, because his conscience 43 hurt him, can you? You know, too, how decent and respectable Jimmy’s been livin’ all these years, putting up a front for the sake of that daughter of his; suppose this was a put-up game to catch him––what do the bulls want him for?”

“I ain’t no mind-reader. I’ll look up this business of securities, and then if the young feller’s talked straight, we’ll try to work it through him, if we can get to him, and I guess we can, so long as I ain’t lost the gift of the gab in twenty years. We’ll be as good, sorrowing heirs as ever Jimmy Brunell could find anywheres.”

Before Walter Pennold could reach the bank, however, an unimpeachably official letter arrived from that institution, confirming the news imparted by the bank-clerk concerning the securities left for James Brunell. Pennold, going to the bank ostensibly to assure those in authority there of his cordial willingness to assist in the search for the heir, incidentally assured himself of Alfred Hicks’ seemingly legitimate occupation. A later visit to Mrs. Lindsay of 46 Jefferson Place convinced him that the young man had lived there for some months and was as generous, open-handed, easy-going a boarder as that excellent woman had ever taken into her house. Just what price was paid by Henry Blaine to Mrs. Lindsay for that statement is immaterial to this narrative, but it suffices that Walter Pennold returned to the sharp-tongued wife of his bosom with only one obstacle in his thoughts between himself and a goodly share of the coveted two hundred thousand dollars.

That obstacle was an extremely healthy fear of Jimmy Brunell. It was true that there had been no connection between them in years, but he remembered Jimmy’s attitude toward the “snitcher,” as well as toward the man who “held out” on his pals; and behind 44 his cupidity was a lurking caution which was made manifest when he walked into the kitchen and found Mrs. Pennold with her shriveled arms immersed in the washtub.

“Say, Mame, the young feller, Hicks, is all right, and so is the bank; but how about Jimmy himself? If I can fix the young feller, and we can pull it off with the bank, that’s all well and good. But s’pose Jimmy should hear of it? Know what would happen to us, don’t you?”

“If he ain’t heard of them securities all this time they’ve been lyin’ forgotten in the bank, it’s safe he won’t hear of ’em now unless you tell him,” retorted his shrewder half, dryly. “Of course, if he’s lived straight, as he has for near twenty years as far as we know, and he finds it out, he’ll grab everything for himself. Why shouldn’t he? But s’pose the bulls are after him for somethin’, and the bank’s hood-winked as well as us, where are we if we mix up in this? Tell me that!”

“There’s another side of it, too, Mame.”

Pennold walked to the window, and regarded the sordid lines of washed clothes contemplatively. “What if Jimmy has been up to somethin’ on the quiet, that the bulls ain’t on to, and this bunch of securities is on the level? If I went to him on the square, and offered him a percentage to play dead, wouldn’t he be ready and willin’ to divide?”

“Of course he would; he’s no fool,” returned Mrs. Pennold shortly. “But let me tell you, Wally, I don’t like the look of that ‘See Walter Pennold of Brooklyn,’ on the note in the bank. S’pose they was trying to trace him through us?”

“You’re talkin’ like a blame’ fool, Mame. Them securities 45 has been there for years, forgotten. Everybody knows that me and Brunell was pals in the old days, but no one’s got nothin’ on us now, and he give up the game years ago.”

“How d’you know he did?” persisted his wife doggedly. “That’s what you better find out, but you’ve gotter be careful about it, in case this whole thing should be a plant.”

“You don’t have to tell me!” Pennold grumbled. “I’ll write him first and then wait a few days, and if anyone’s tailing me in the meantime, they’ll have a run for their money.”

“Write him!”

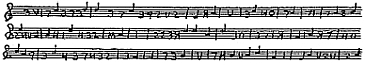

“Of course. You may have forgotten the old cipher, but I haven’t. You know yourself we invented it, Jimmy and me, and the police tried their level best to get on to it, but failed.”

“You can’t address it in cipher, and if you’re tailed you won’t get a chance to mail it, Wally. Better wait and try to see him without writing.”

For answer Pennold opened a drawer in the table, drew forth a grimy sheet of paper and an envelope, and bent laboriously to his task. It was long past dusk when he had finished, and tossed the paper across the table for his wife’s perusal. This is what she saw:

When she had gazed long at the characters, she shook her head at him, and a slow smile came over her face.

“You’ve forgotten a little yourself, Wally. You made a mistake in the k.”

He glanced half-incredulously at it, and then laid his huge, rough hand on her thin hair in the first caress he had given her in years.

“By God, old girl, you’re a smart one! You’re right. Now listen. You’ve got to do the rest for me, the hardest part. Mail it.”

“How? If we’re tailed––”

“There’ll be only one on the job, if we are, and I’ll keep him busy to-morrow morning. You go to the market as usual, then go into that big department store, Ahearn & McManus’. There’s a mail chute there, next the notion counter on the ground floor. Buy a spool of thread or somethin’, and while you’re waitin’ for change, drop the letter in the box. You used to be pretty slick in department stores, Mame––”

“Smoothest shoplifter in New York until I got palsy!” she interrupted proudly, an unaccustomed glow on her sallow face. “I’ll do it, Wally; I know I can!”

The next morning Alfred Hicks was a little late in getting to his work at the bank––so late, in fact, that he had only time to wave a cordial greeting to his new friends in their cages as he passed. He paused, however, that evening, with a pot of flowering bloom for Mrs. Pennold’s dingy, not over-clean window-sill, and a packet of tobacco which he shared generously with his host. He talked much, with the garrulous self-confidence of youth, but did not mention the matter of the securities, and left the crafty couple completely disarmed.

Neither on entering nor leaving did Hicks appear to notice a short, swarthy figure loitering in the shadow of a dejected-looking ailanthus tree near the corner. 47 It would have appeared curious, therefore, that the lurking figure followed the bank-clerk almost to his lodgings, had it not been for the fact that just before Jefferson Place was reached the figure sidled up to Hicks’ side and whispered:

“No news yet, Morrow. Pennold went this morning to old Loui the Grabber and tried to borrow money from him, but didn’t get it. I heard the whole talk. Then he went to Tanbark Pete’s and got a ten-spot. After that, he divided his time between two saloons, where he played dominoes and pinochle, and his own house. I’ve got to report to H. B. when I’m sure the subject is safe for the night. Have you found anything yet?”

“Only that I’ve got him on the run. If he knows where our man is, Suraci, he’ll go after him in a day or two. Meantime, tell H. B., in case I don’t get a chance to let him know, that the securities stunt went, all right, and my end of it is O. K.”

The next day, and the following, Pennold did indeed set for the young Italian detective a swift pace. He departed upon long rambles, which started briskly and ended aimlessly; he called upon harmless and tedious acquaintances, from Jamaica to Fordham; he went––apparently and ostentatiously to look for a position as janitor––to many office-buildings in lower Manhattan, which he invariably entered and left by different doors. In the evenings he sat blandly upon his own stoop, smoking and chatting amiably if monosyllabically with his wife and their new-found friend, Alfred Hicks, while his indefatigable shadow glowered apparently unnoticed from the gloom of the ailanthus tree.

On Thursday morning, however, Pennold betook himself leisurely to the nearest subway station, and there the real trial of strength between him and his unseen 48 antagonist began. From the Brooklyn Bridge station he rode to the Grand Central; then with a speed which belied his physical appearance, he raced across the bridge to the downtown platform, and caught a train for Fourteenth Street. There he swiftly turned north to Seventy-second Street––then to the Grand Central, again to Ninety-sixth, and so on, doubling from station to station until finally he felt that he must be entirely secure from pursuit.