Title: The Story of the Great War, Volume 5

Editor: Francis J. Reynolds

Allen L. Churchill

Francis Trevelyan Miller

Release date: July 7, 2009 [eBook #29341]

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/29341

Credits: E-text prepared by Charlene Taylor, Christine P. Travers, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://www.archive.org/details/storyofgreatwarh05churuoft |

Transcriber's note:

Obvious printer's errors have been corrected. Hyphenation and accentuation have been made consistent. All other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been retained.

Page 26: "notwithstanding he or they may believe to the contrary" has been changed to "notwithstanding what he or they may believe to the contrary".

Pages 178/179: Words are missing between "cross-" and "of" in the sentence: Ten miles west of Kolki the Russians succeeded in cross- of Gruziatin, two miles north of Godomitchy, the small German garrison of which, consisting of some five hundred officers and men, fell into Russian captivity.

Page 200: "during pursuit of the Russians" has been changed to "during pursuit by the Russians".

BATTLE OF JUTLAND BANK · RUSSIAN

OFFENSIVE · KUT-EL-AMARA

EAST AFRICA · VERDUN · THE

GREAT SOMME DRIVE · UNITED

STATES AND BELLIGERENTS

SUMMARY OF TWO YEARS' WAR

VOLUME V

P · F · COLLIER & SON · NEW YORK

Copyright 1916

By P. F. Collier & Son

PART I.—AUSTRIAN PROPAGANDA

CHAPTER

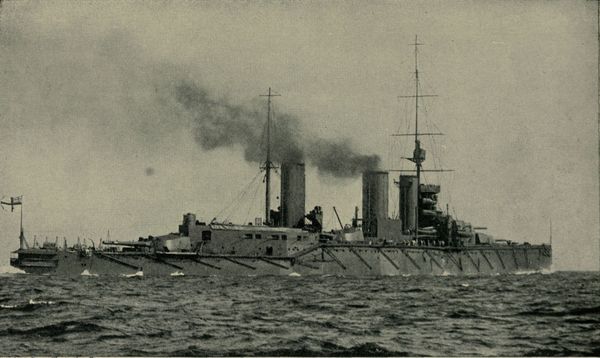

PART II.—OPERATIONS ON THE SEA

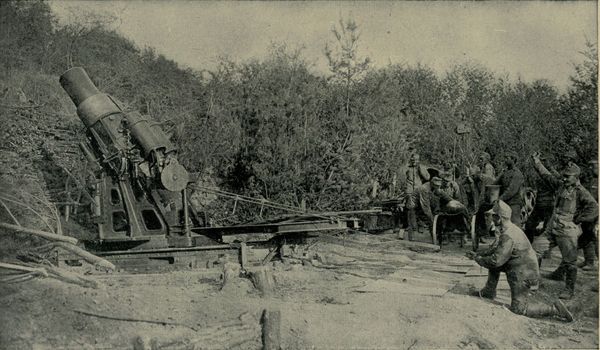

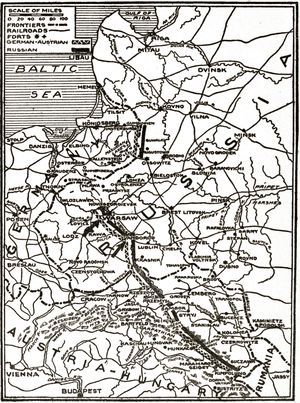

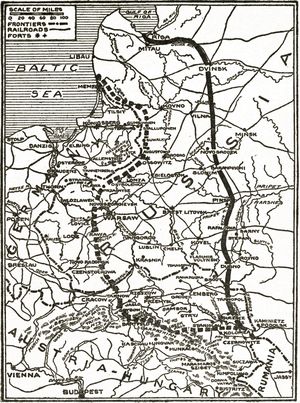

PART III.—CAMPAIGN ON THE EASTERN FRONT

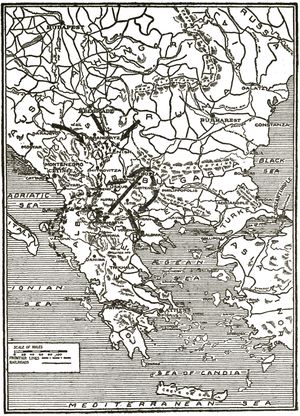

PART IV.—THE BALKANS

PART V.—AUSTRO-ITALIAN CAMPAIGN

PART VI.—RUSSO-TURKISH CAMPAIGN

PART VII.—CAMPAIGN IN MESOPOTAMIA AND PERSIA

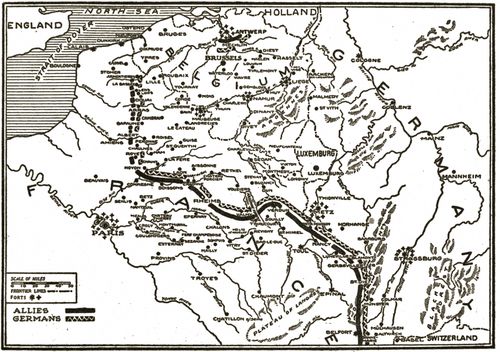

(p. 003) PART VIII.—OPERATIONS ON THE WESTERN FRONT

PART IX.—THE WAR IN THE AIR

PART X.—THE UNITED STATES AND THE BELLIGERENTS

AUSTRIAN AMBASSADOR IMPLICATED IN STRIKE PLOTS—HIS RECALL—RAMIFICATIONS OF GERMAN CONSPIRACIES

Public absorption in German propaganda was abating when attention became directed to it again from another quarter. An American war correspondent, James F. J. Archibald, a passenger on the liner Rotterdam from New York, who was suspected by the British authorities of being a bearer of dispatches from the German and Austrian Ambassadors at Washington, to their respective Governments, was detained and searched on the steamer's arrival at Falmouth on August 30, 1915. A number of confidential documents found among his belongings were seized and confiscated, the British officials justifying their action as coming within their rights under English municipal law. The character of the papers confirmed the British suspicions that Archibald was misusing his American passport by acting as a secret courier for countries at war with which the United States was at peace.

The seized papers were later presented to the British Parliament and published. In a bulky dossier, comprising thirty-four documents found in Archibald's possession, was a letter from the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador at Washington, Dr. Dumba, to Baron Burian, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister. In this letter Dr. Dumba took "this rare and safe opportunity" of "warmly recommending" to the Austrian Foreign Office certain proposals made by the editor of a Hungarian-American organ, the "Szabadsag," for effecting strikes in plants of the Bethlehem (p. 010) Steel Company and others in the Middle West engaged in making munitions for the Allies.

The United States Government took a serious view of the letter recommending the plan for instigating strikes in American factories. Dr. Dumba, thrown on his defense, explained to the State Department that the incriminating proposals recommended in the document did not originate from him personally, but were the fruit of orders received from Vienna. This explanation was not easily acceptable. The phraseology of Dr. Dumba far from conveyed the impression that he was submitting a report on an irregular proposal inspired by instructions of the Austrian Government. Such a defense, however, if accepted, only made the matter more serious. Instead of the American Government having to take cognizance of an offensive act by an ambassador, the Government which employed him would rather have to be called to account. Another explanation by Dr. Dumba justified his letter to Vienna on the ground that the strike proposal urged merely represented a plan for warning all Austrians and Hungarians, employed in the munition factories, of the penalties they would have to pay if they ever returned to their home country, after aiding in producing weapons and missiles of destruction to be used against the Teutonic forces. This defense also lacked convincing force, as the letter indicated that the aim was so to cripple the munition factories that their output would be curtailed or stopped altogether—an object that could only be achieved by a general strike of all workers.

The Administration did not take long to make up its mind that the time for disciplining foreign diplomats who exceeded the duties of their office had come. On September 8, 1915, Austria-Hungary was notified that Dr. Konstantin Theodor Dumba was no longer acceptable as that country's envoy in Washington. The American note dispatched to Ambassador Penfield at Vienna for transmission to the Austrian Foreign Minister was blunt and direct. After informing Baron Burian that Dr. Dumba had admitted improper conduct in proposing to his Government plans to instigate strikes in American manufacturing plants, the United States thus demanded his recall:

(p. 011) "By reason of the admitted purpose and intent of Dr. Dumba to conspire to cripple legitimate industries of the people of the United States and to interrupt their legitimate trade, and by reason of the flagrant violation of diplomatic propriety in employing an American citizen, protected by an American passport, as a secret bearer of official dispatches through the lines of the enemy of Austria-Hungary, the President directs us to inform your excellency that Dr. Dumba is no longer acceptable to the Government of the United States as the Ambassador of His Imperial Majesty at Washington."

Dr. Dumba was not recalled by his Government until September 22, 1915, fourteen days after the American demand. Meanwhile Dr. Dumba had cabled to Vienna, requesting that he be ordered to return on leave of absence "to report." His recall was ostensibly in response to his personal request, but the Administration objected to this resort to a device intended to cloak the fact that he was now persona non grata whose return was really involuntary, and would not recognize a recall "on leave of absence." His Government had no choice but to recall him officially in view of the imminent contingency that otherwise he would be ousted, and in that case would be denied safe conduct from capture by an allied cruiser in his passage across the ocean. His request for passports and safe conduct was, in fact, disregarded by the Administration, which informed him that the matter was one to be dealt directly with his Government, pending whose official intimation of recall nothing to facilitate his departure could be done. On the Austrian Government being notified that Dr. Dumba's departure "on leave of absence" would not be satisfactory, he was formally recalled on September 28, 1915.

The seized Archibald dossier included a letter from the German military attaché, Captain Franz von Papen, to his wife, containing reference to Dr. Albert's correspondence, which left no doubt that the letters were genuine:

"Unfortunately, they stole a fat portfolio from our good Albert in the elevated (a New York street railroad). The English secret service of course. Unfortunately, there were some very (p. 012) important things from my report among them such as buying up liquid chlorine and about the Bridgeport Projectile Company, as well as documents regarding the buying up of phenol and the acquisition of Wright's aeroplane patent. But things like that must occur. I send you Albert's reply for you to see how we protect ourselves. We composed the document to-day."

The "document" evidently was Dr. Albert's explanation discounting the significance and importance of the letters. This explanation was published on August 20, 1915.

The foregoing disclosures of documents covered a wide range of organized German plans for embarrassing the Allies' dealings with American interests; but they related rather more to accomplished operations and such activities as were revealed to be under way—e. g., the acquisition of munitions combined with propaganda for an embargo—were not deemed to be violative of American law. But this stage of intent to clog the Allies' facilities for obtaining sinews of war, in the face of law, speedily grew to one of achievement more or less effective according to the success with which the law interposed to spoil the plans.

The autumn and winter of 1915 were marked by the exposure of a number of German plots which revealed that groups of conspirators were in league in various parts of the country, bent on wrecking munition plants, sinking ships loaded with Allies' supplies, and fomenting strikes. Isolated successes had attended their efforts, but collectively their depredations presented a serious situation. The exposed plots produced clues to secret German sources from which a number of mysterious explosions at munition plants and on ships had apparently been directed. Projected labor disturbances at munition plants were traced to a similar origin. The result was that the docket of the Federal Department of Justice became laden with a motley collection of indictments which implicated fifty or more individuals concerned in some dozen conspiracies, in which four corporations were also involved.

These cases only represented a portion of the criminal infractions of neutrality laws, which had arisen since the outbreak of the war. In January, 1916, an inquiry in Congress directed the (p. 013) Attorney General to name all persons "arrested in connection with criminal plots affecting the neutrality of our Government." Attorney General Gregory furnished a list of seventy-one indicted persons, and the four corporations mentioned. A list of merely arrested persons would not have been informative, as it would have conveyed an incomplete and misleading impression. Such a list, Mr. Gregory told Congress, would not include persons indicted but never arrested, having become fugitives from justice; nor persons indicted but never arrested, having surrendered; but would include persons arrested and not proceeded against. Thus there were many who had eluded the net of justice by flight and some through insufficient evidence. The seventy-one persons were concerned in violations of American neutrality in connection with the European war.

The list covered several cases already recorded in this history, namely:

A group of Englishmen, and another of Montenegrins, involved in so-called enlistment "plots" for obtaining recruits on American soil for the armies of their respective countries.

The case of Werner Horn, indicted for attempting to destroy by an explosive the St. Croix railroad bridge between Maine and New Brunswick.

A group of nine men, mainly Germans, concerned in procuring bogus passports to enable them to take passage to Europe to act as spies. Eight were convicted, the ninth man, named Von Wedell, a fugitive passport offender, was supposed to have been caught in England and shot.

The Hamburg-American case, in which Dr. Karl Buenz, former German Consul General in New York, and other officials or employees of that steamship company, were convicted (subject to an appeal) of defrauding the Government in submitting false clearance papers as to the destinations of ships sent from New York to furnish supplies to German war vessels in the Atlantic.

A group of four men, a woman, and a rubber agency, indicted on a similar charge, their operations being on the Pacific coast, where they facilitated the delivery of supplies to German cruisers when in the Pacific in the early stages of the war.

(p. 014) There remain the cases which, in the concatenation of events, might logically go on record as direct sequels to the public divulging of the Albert and Archibald secret papers. These included:

A conspiracy to destroy munition-carrying ships at sea and to murder the passengers and crews. Indictments in these terms were brought against a group of six men—Robert Fay, Dr. Herbert O. Kienzie, Walter L. Scholz, Paul Daeche, Max Breitung, and Engelbert Bronkhorst.

A conspiracy to destroy the Welland Canal and to use American soil as a base for unlawful operations against Canada. Three men, Paul Koenig, a Hamburg-American line official, R. E. Leyendecker, and E. J. Justice, were involved in this case.

A conspiracy to destroy shipping on the Pacific Coast. A German baron, Von Brincken, said to be one of the kaiser's army officers; an employee of the German consulate at San Francisco, C. C. Crowley; and a woman, Mrs. Margaret W. Cornell, were the offenders.

A conspiracy to prevent the manufacture and shipment of munitions to the allied powers. A German organization, the National Labor Peace Council, was indicted on this charge, as well as a wealthy German, Franz von Rintelen, described as an intimate friend of the German Crown Prince, and several Americans known in public life.

In most of these cases the name of Captain Karl Boy-Ed, the German naval attaché, or Captain Franz von Papen, the German military attaché, figured persistently. The testimony of informers confirmed the suspicion that a wide web of secret intrigue radiated from sources related to the German embassy and enfolded all the conspiracies, showing that few, if any, of the plots, contemplated or accomplished, were due solely to the individual zeal of German sympathizers.[Back to Contents]

THE PLOT TO DESTROY SHIPS—PACIFIC COAST CONSPIRACIES—HAMBURG-AMERICAN CASE—SCOPE OF NEW YORK INVESTIGATIONS

The plot of Fay and his confederates to place bombs on ships carrying war supplies to Europe was discovered when a couple of New York detectives caught Fay and an accomplice, Scholz, experimenting with explosives in a wood near Weehawken, N. J., on October 24, 1915. Their arrests were the outcome of a police search for two Germans who secretly sought to purchase picric acid, a component of high explosives which had become scarce since the war began. Certain purchases made were traced to Fay. On the surface Fay's offense seemed merely one of harboring and using explosives without a license; but police investigations of ship explosions had proceeded on the theory that the purchases of picric acid were associated with them.

Fay confirmed this surmise. He described himself as a lieutenant in the German army, who, with the sanction of the German secret information service, had come to the United States after sharing in the Battle of the Marne, to perfect certain mine devices for attachment to munition ships in order to cripple them. In a Hoboken storage warehouse was found a quantity of picric acid he had deposited there, with a number of steel mine tanks, each fitted with an attachment for hooking to the rudder of a vessel, and clockwork and wire to fire the explosive in the tanks. In rooms occupied by Fay and Scholz were dynamite and trinitrotoluol (known as T-N-T), many caps of fulminate of mercury, and Government survey maps of the eastern coast line and New York Harbor. The conspirators' equipment included a fast motor boat that could dart up and down the rivers and along the water front where ships were moored, a high-powered automobile, and four suit cases containing a number of disguises. The purpose of (p. 016) the enterprise was to stop shipments of arms and ammunitions to the Allies. The disabling of ships, said Fay, was the sole aim, without destruction of life. To this end he had been experimenting for several months on a waterproof mine and a detonating device that would operate by the swinging of a rudder, to which the mine would be attached, controlled by a clock timed to cause the explosion on the high seas. The German secret service, both Fay and Scholz said, had provided them with funds to pursue their object. Fay's admission to the police contained these statements:

"I saw Captain Boy-Ed and Captain von Papen on my arrival in this country. Captain Boy-Ed told me that I was doing a dangerous thing. He said that political complications would result and he most assuredly could not approve of my plans. When I came to this country, however, I had letters of introduction to both those gentlemen. Both men warned me not to do anything of the kind I had in mind. Captain von Papen strictly forbade me to attach any of the mines to any of the ships leaving the harbors of the United States. But anyone who wishes to, can read between the lines.

"The plan on which I worked was to place a mine on the rudder post so that when it exploded it would destroy the rudder and leave the ship helpless. There was no danger of any person being killed. But by this explosion I would render the ship useless and make the shipment of munitions so difficult that the owners of ships would be intimidated and cause insurance rates to go so high that the shipment of ammunition would be seriously affected, if not stopped."

The Federal officials questioned the statement that Fay's design was merely to cripple munition ships. Captain Harold C. Woodward of the Corps of Engineers, a Government specialist on explosives, held that if the amount of explosive, either trinitrotoluol, or an explosive made from chlorate of potash and benzol, required by the mine caskets found in Fay's possession, was fired against a ship's rudder, it would tear open the stern and destroy the entire ship, if not its passengers and crew, so devastating would be the explosive force. A mine of the size Fay used, three (p. 017) feet long and ten inches by ten inches, he said, would contain over two cubic feet:

"If the mine was filled with trinitrotoluol the weight of the high explosive would be about 180 pounds. If it was filled with a mixture of chlorate of potash and benzol the weight would be probably 110 pounds. Either charge if exploded on the rudder post would blow a hole in the ship.

"The amount of high explosive put into a torpedo or a submarine mine is only about 200 pounds. It must not be forgotten that water is practically noncompressible, and that even if the explosion did not take place against the ship the effect would be practically the same. Oftentimes a ship is sunk by the explosion of a torpedo or a mine several feet from the hull.

"Furthermore, if the ship loaded with dynamite or high explosive, and the detonating wave of the first explosion reaches that cargo, the cargo also would explode. In high explosives the detonating wave in the percussion cap explodes the charge in much the same manner in which a chord struck on a piano will make a picture wire on the wall vibrate if both the wire and the piano string are tuned alike.

"Accordingly, if a ship carrying tons of high explosive is attacked from the outside by a mine containing 100 pounds of similar explosive, the whole cargo would go up and nothing would remain of either ship or cargo."

Therefore the charge made against Fay and Scholz, and four other men later arrested, Daeche, Kienzie, Bronkhorst, and Breitung, namely, conspiracy to "destroy a ship," meant that and all the consequences to the lives of those on board. Breitung was a nephew of Edward N. Breitung, the purchaser of the ship Dacia from German ownership, which was seized by the French on the suspicion that its transfer to American registry was not bona fide.

The plot was viewed as the most serious yet bared. Fay and his confederates were credited with having spent some $30,000 on their experiments and preparations, and rumor credited them with having larger sums of money at their command.

The press generally doubted if they could have conducted their operations without such financial support being extended them in (p. 018) the United States. A design therefore was seen in Fay's statement that he was financed from Germany to screen the source of this aid by transferring the higher responsibility in toto to official persons in Germany who were beyond the reach of American justice. These and other insinuations directed at the German Embassy produced a statement from that quarter repudiating all knowledge of the Fay conspiracy, and explaining that its attachés were frequently approached by "fanatics" who wanted to sink ships or destroy buildings in which munitions were made.

A similar conspiracy, but embracing the destruction of railroad bridges as well as munition ships and factories, was later revealed on the Pacific Coast. Evidence on which indictments were made against the men Crowley, Von Brincken, and a woman confederate aforementioned, named Captain von Papen, the German military attaché, as the director of the plot. The accused were also said to have had the cooperation of the German Consul General at San Francisco. The indictments charged them, inter alia, with using the mails to incite arson, murder, and assassination. Among the evidence the Government unearthed was a letter referring to "P," which, the Federal officials said, meant Captain von Papen. The letter, which related to a price to be paid for the destruction of a powder plant at Pinole, Cal., explained how the price named had been referred to others "higher up." It read:

"Dear Sir: Your last letter with clipping to-day, and note what you have to say. I have taken it up with them and 'B' [which the Federal officials said stood for Franz Bopp, German Consul at San Francisco] is awaiting decision of 'P' [said to stand for Captain von Papen in New York], so cannot advise you yet, and will do so as soon as I get word from you. You might size up the situation in the meantime."

The indictments charged that the defendants planned to destroy munition plants at Aetna and Gary, Ind., at Ishpeming, Mich., and at other places. The Government's chief witness, named Van Koolbergen, told of being employed by Baron von Brincken, of the German Consulate at San Francisco, to make and use clockwork bombs to destroy the commerce of neutral (p. 019) nations. For each bomb he received $100 and a bonus for each ship damaged or destroyed. For destroying a railway trestle in Canada over which supply trains for the Allies passed, he said he received first $250, and $300 further from a representative of the German Government, the second payment being made upon his producing newspaper clippings recording the bridge's destruction. It appeared that Van Koolbergen divulged the plot to the Canadian Government.

The three defendants and Van Koolbergen were later named in another indictment found by a San Francisco Federal Grand Jury, involving in all sixty persons, including the German Consul General in that city, Franz Bopp, the Vice Consul, Baron Eckhardt, H. von Schack, Maurice Hall, Consul for Turkey, and a number of men identified with shipping and commercial interests.

The case was the first in which the United States Government had asked for indictments against the official representatives of any of the belligerents. The warrants charged a conspiracy to violate the Sherman Anti-Trust Law by attempting to damage plants manufacturing munitions for the Allies, thus interfering with legitimate commerce, and with setting on foot military expeditions against a friendly nation in connection with plans to destroy Canadian railway tunnels.

The vice consul, Von Schack, was also indicted with twenty-six of the defendants on charges of conspiring to defraud the United States by sending supplies to German warships in the earlier stages of the war, the supplies having been sent from New York to the German Consulate in San Francisco. The charges related to the outfitting of five vessels. One of the latter, the Sacramento, now interned in a Chilean port, cleared from San Francisco, and when out to sea, the Government ascertained, was taken in command by the wireless operator, who was really a German naval reserve officer. Off the western coast of South America the Sacramento was supposed to have got into wireless communication with German cruisers then operating in the Pacific. There she joined the squadron under a show of compulsion, as though held up and captured. In this guise the war (p. 020) vessels seemingly convoyed the Sacramento to an island in the Pacific, where her cargo of food, coal, and munitions were transferred to her supposed captors. The Sacramento then proceeded to a Chilean port where her commanding officer reported that he had been captured by German warships and deprived of his cargo. The Chilean authorities doubted the story and ordered the vessel to be interned.

Far more extensive were unlawful operations in this direction conducted by officials of the Hamburg-American line, as revealed at their trial in New York City in November, 1915. The indictments charged fraud against the United States by false clearances and manifests for vessels chartered to provision, from American ports, German cruisers engaged in commerce destroying. The prosecution proceeded on the belief that the Hamburg-American activities were merely part of a general plan devised by German and Austrian diplomatic and consular officers to use American ports, directly and indirectly, as war bases for supplies. The testimony in the case involved Captain Boy-Ed, the German naval attaché, who was named as having directed the distribution of a fund of at least $750,000 for purposes described as "riding roughshod over the laws of the United States." The defense freely admitted chartering ships to supply German cruisers at sea, and in fact named a list of twelve vessels, so outfitted, showing the amount spent for coal, provisions, and charter expenses to have been over $1,400,000; but of this outlay only $20,000 worth of supplies reached the German vessels. The connection of Captain Boy-Ed with the case suggested the defense that the implicated officials consulted with him as the only representative in the United States of the German navy, and were really acting on direct orders from the German Government, and not under the direction of the naval attaché. Military necessity was also a feasible ground for pleading justification in concealing the fact that the ships cleared to deliver their cargoes to German war vessels instead of to the ports named in their papers. These ports were professed to be their ultimate destinations if the vessels failed to meet the German cruisers. Had any other course been pursued, the primary destinations (p. 021) would have become publicly known and British and other hostile warships patrolling the seas would have been on their guard. The defendants were convicted, but the case remained open on appeal.

About the same time the criminal features of the Teutonic propaganda engaged the lengthy attention of a Federal Grand Jury sitting in New York City. A mass of evidence had been accumulated by Government agents in New York, Washington, and other cities. Part of this testimony related to the Dumba and Von Papen letters found in the Archibald dossier. Another part concerned certain revelations a former Austrian consul at San Francisco, Dr. Joseph Goricar, made to the Department of Justice. This informant charged that the German and Austrian Governments had spent between $30,000,000 and $40,000,000 in developing an elaborate spy system in the United States with the aim of destroying munition plants, obtaining plans of American fortifications, Government secrets, and passports for Germans desiring to return to Germany. These operations, he said, were conducted with the knowledge of Count von Bernstorff, the German Ambassador. Captains Boy-Ed and Von Papen were also named as actively associated with the conspiracy, as well as Dr. von Nuber, the Austrian Consul General in New York, who, he said, directed the espionage system and kept card indices of spies in his office.

The investigation involved, therefore, diplomatic agents, who were exempt from prosecution; a number of consuls and other men in the employ of the Teutonic governments while presumably connected with trustworthy firms; and notable German-Americans, some holding public office.

Contributions to the fund for furthering the conspiracy, in addition to the substantial sums believed to be supplied by the German and Austrian Governments, were said to have come freely from many Germans, citizens and otherwise, resident in the United States. The project, put succinctly, was "to buy up or blow up the munition plants." The buying up, as previously shown, having proved to be impracticable, an alternative plan presented itself to "tie up" the factories by strikes. This was (p. 022) Dr. Dumba's miscarried scheme, which aimed at bribing labor leaders to induce workmen, in return for substantial strike pay, to quit work in the factories. Allied to this design was the movement to forbid citizens of Germany and Austria-Hungary from working in plants supplying munitions to their enemies. Such employment, they were told, was treasonable. The men were offered high wages at other occupations if they would abandon their munition work. Teutonic charity bazaars held throughout the country and agencies formed to help Teutons out of employment were regarded merely as means to influence men to leave the munition plants and thus hamper the export of war supplies. Funds were traced to show how money traveled through various channels from the fountainhead to men working on behalf of the Teutonic cause. Various firms received sums of money, to be paid to men ostensibly in the employ of the concerns, but who in reality were German agents working under cover.

Evidence collected revealed these various facts of the Teutonic conspiracy. But the unfolding of such details before the Grand Jury was incidental to the search for the men who originated the scheme, acted as almoners or treasurers, or supervised, as executives, the horde of German and Austrian agents intriguing on the lower slopes under their instructions.[Back to Contents]

VON RINTELEN'S ACTIVITIES—CONGRESSMAN INVOLVED—GERMANY'S REPUDIATIONS—DISMISSAL OF CAPTAINS BOY-ED AND VON PAPEN

In this quest the mysterious movements and connections of one German agent broadly streaked the entire investigation. This person was Von Rintelen, supposed to be Dr. Dumba's closest lieutenant ere that envoy's presence on American soil was dispensed with by President Wilson. Von Rintelen's activities (p. 023) belonged to the earlier period of the war, before the extensive ramifications of the criminal phases of the German propaganda were known. At present he was an enforced absentee from the scenes of his exploits, being either immured by the British in the Tower of London, or in a German concentration camp as a spy. This inglorious interruption to the rôle he appeared to play while in the United States as a peripatetic Midas, setting plots in train by means of an overflowing purse, was due to an attempt to return to Germany on the liner Noordam in July, 1915. The British intercepted him at Falmouth, and promptly made him a prisoner of war after examining his papers.

Whatever was Von Rintelen's real mission in the United States in the winter of 1914-15, he was credited with being a personal emissary and friend of the kaiser, bearing letters of credit estimated to vary between $50,000,000 and $100,000,000. The figure probably was exaggerated in view of the acknowledged inability of the German interests in the United States to command anything like the lesser sum named to acquire all they wanted—control of the munition plants. His initial efforts appeared to have been directed to a wide advertising campaign to sway American sentiment against the export of arms shipments. His energies, like those of others, having been fruitless in this field, he was said to have directed his attention to placing large orders under cover for munitions with the object of depleting the source of such supplies for the Allies, and aimed to control some of the plants by purchasing their stocks. The investigation in these channels thus contributed to confirm the New York "World's" charges against German officialdom, based on its exposé of the Albert documents. Mexican troubles, according to persistent rumor, inspired Von Rintelen to use his ample funds to draw the United States into conflict with its southern neighbor as a means of diverting munition supplies from the Allies for American use. He and other German agents were suspected of being in league with General Huerta with a view to promoting a new revolution in Mexico.

The New York Grand Jury's investigations of Von Rintelen's activities became directed to his endeavors to "buy strikes." The (p. 024) outcome was the indictment of officials of a German organization known under the misleading name of the National Labor Peace Council. The persons accused were Von Rintelen himself, though a prisoner in England; Frank Buchanan, a member of Congress; H. Robert Fowler, a former representative; Jacob C. Taylor, president of the organization; David Lamar, who previously had gained notoriety for impersonating a congressman in order to obtain money and known as the "Wolf of Wall Street," and two others, named Martin and Schulties, active in the Labor Peace Council and connected with a body called the Antitrust League. They were charged with having, in an attempt to effect an embargo (which would be in the interest of Germany) on the shipment of war supplies, conspired to restrain foreign trade by instigating strikes, intimidating employees, bribing and distributing money among officers of labor organizations. Von Rintelen was said to have supplied funds to Lamar wherewith the Labor Peace Council was enabled to pursue these objects. One sum named was $300,000, received by Lamar from Von Rintelen for the organization of this body; of that sum Lamar was said to have paid $170,000 to men connected with the council.

The Labor Peace Council was organized in the summer of 1915, and met first in Washington, when resolutions were passed embracing proposals for international peace, but were viewed as really disguising a propaganda on behalf of German interests. The Government sought to show that the organization was financed by German agents and that its crusade was part and parcel of pro-German movements whose ramifications throughout the country had caused national concern.

Von Rintelen's manifold activities as chronicled acquired a tinge of romance and not a little of fiction, but the revelations concerning him were deemed sufficiently serious by Germany to produce a repudiation of him by the German embassy on direct instructions from Berlin, i. e.:

"The German Government entirely disavows Franz Rintelen, and especially wished to say that it issued no instructions of any kind which could have led him to violate American laws."

(p. 025) It is essential to the record to chronicle that American sentiment did not accept German official disclaimers very seriously. They were too prolific, and were viewed as apologetic expedients to keep the relations between the two governments as smooth as possible in the face of conditions which were daily imperiling those relations. Germany appeared in the position of a Frankenstein who had created a hydra-headed monster of conspiracy and intrigue that had stampeded beyond control, and washed her hands of its depredations. The situation, however, was only susceptible to this view by an inner interpretation of the official disclaimers. In letter, but not in spirit, Germany disowned her own offspring by repudiating the deeds of plotters in terms which deftly avoided revealing any ground for the suspicion—belied by events—that those deeds had an official inception. Germany, in denying that the plotters were Government "agents," suggested that these men pursued their operations with the recognition that they alone undertook all the risks, and that if unmasked it was their patriotic duty not to betray "the cause," which might mean their country, the German Government, or the German officials who directed them. Not all the exposed culprits had been equal to this self-abnegating strain on their patriotism; some, like Fay, were at first talkative in their admissions that their pursuits were officially countenanced, another recounted defense of Werner Horn, who attempted to destroy a bridge connecting Canada and the United States, even went so far as to contend that the offense was military—an act of war—and therefore not criminal, on the plea that Horn was acting as a German army officer. In other cases incriminating evidence made needless the assumption of an attitude by culprits of screening by silence the complicity of superiors. Yet despite almost daily revelations linking the names of important German officials, diplomatic and consular, with exposed plots, a further repudiation came from Berlin in December, 1915, when the New York Grand Jury's investigation was at high tide. This further disavowal read:

"The German Government, naturally, has never knowingly accepted the support of any person, group of persons, society or (p. 026) organization seeking to promote the cause of Germany in the United States by illegal acts, by counsels of violence, by contravention of law, or by any means whatever that could offend the American people in the pride of their own authority.... I can only say, and do most emphatically declare to Germans abroad, to German-American citizens of the United States, to the American people all alike, that whoever is guilty of conduct tending to associate the German cause with lawlessness of thought, suggestion or deed against life, property, and order in the United States is, in fact, an enemy of that very cause and a source of embarrassment to the German Government, notwithstanding what he or they may believe to the contrary."

The stimulus for this politic disavowal, and one must be sought, since German statements always had a genesis in antecedent events—was not apparently due to continued plot exposures, which were too frequent, but could reasonably be traced to a ringing address President Wilson had previously made to Congress on December 7, 1915. The President, amid the prolonged applause of both Houses, meeting in joint session, denounced the unpatriotism of many Americans of foreign descent. He warned Congress that the gravest threats against the nation's peace and safety came from within, not from without. Without naming German-Americans, he declared that many "had poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life," and called for the prompt exercise of the processes of law to purge the country "of the corrupt distempers brought on by these citizens."

"I am urging you," he said in solemn tones, "to do nothing less than save the honor and self-respect of the nation. Such creatures of passion, disloyalty, and anarchy must be crushed out."

Three days before this denunciation, the Administration had demanded from Germany the recall of Captains Boy-Ed and Von Papen, respectively the military aid and naval attaché of the German embassy. Unlike the procedure followed in requesting Dr. Dumba's recall, no reasons were given. None according to historic usage were necessary, and if reasons were given, they (p. 027) could not be questioned. It was sufficient that a diplomatic officer was non persona grata by the fact that his withdrawal was demanded.

Germany, through her embassy, showed some obduracy in acting upon a request for these officials' recall without citing the cause of complaint. There was an anxiety that neither should be recalled with the imputation resting upon them that they were concerned, say, in the so-called Huerta-Mexican plot—if one really existed—or with the conspiracies to destroy munition plants and munition ships, or, in Captain Boy-Ed's case, in the Hamburg-American line's chartered ships for provisioning of German cruisers, sailing with false manifests and clearance papers.

An informal note from Secretary Lansing to Count von Bernstorff so far acceded to the request for a bill of particulars, though not customary, that the German embassy professed to be satisfied. Secretary Lansing stated that Captains Boy-Ed and Von Papen had rendered themselves unacceptable by "their activities in connection with naval and military affairs." This was intended to mean that such activities here indicated had brought the two officials in contact with private individuals in the United States who had been involved in violation of the law. The incidents and circumstances of this contact were of such a cumulative character that the two attachés could no longer be deemed as acceptable to the American Government. Here was an undoubted implication of complicity by association with wrongdoers, but not in deed. The unofficial statement of the cause of complaint satisfied the embassy in that it seemed to relieve the two officers from the imputation of themselves having violated American laws. The record stood, however, that the United States had officially refused to give any reasons for demanding their recall. Germany officially recalled them on December 10, 1915, and before the year was out they quitted American soil under safe conducts granted by the British Government.

Captain von Papen, however, was not permitted to escape the clutches of the British on the ocean passage. While respecting his person, they seized his papers. These, duly published, made his complicity in the German plots more pronounced than ever. (p. 028) His check counterfoils showed a payment of $500 to "Mr. de Caserta, Ottawa." De Caserta was described in British records as "a dangerous German spy, who takes great risks, has lots of ability, and wants lots of money." He was supposed to have been involved in conspiracies in Canada to destroy bridges, armories, and munition factories. He had offered his services to the British Government, but they were rejected. Later he was reported to have been shot or hanged in London as a spy.

Another check payment by Captain von Papen was to Werner Horn for $700. Horn, as before recorded, was the German who attempted to blow up a railroad bridge at Vanceboro, Maine. Other payments shown by the Von Papen check book were to Paul Koenig, of the Hamburg-American line. Koenig was arrested in New York in December, 1915, on a charge of conspiracy with others to set on foot a military expedition from the United States to destroy the locks of the Welland Canal for the purpose of cutting off traffic from the Great Lakes to the St. Lawrence River.

The German consul at Seattle was shown to have received $500 from Captain von Papen shortly before an explosion occurred there in May, 1915, and $1,500 three months earlier. Another payment was to a German, who, while under arrest in England on a charge of being a spy, committed suicide.[Back to Contents]

GREAT BRITAIN'S DEFENSE OF BLOCKADE—AMERICAN METHODS IN CIVIL WAR CITED

Issues with Great Britain interposed to engage the Administration's attention, in the brief intervals when Germany's behavior was not doing so, to the exclusion of all other international controversies produced by the war. In endeavoring to balance the scales between the contending belligerents, the United States (p. 029) had to weigh judicially the fact that their offenses differed greatly in degree. Germany's crimes were the wanton slaughter of American and other neutral noncombatants, Great Britain's the wholesale infringements of American and neutral property rights. Protests menacing a rupture of relations had to be made in Germany's case; but those directed to Great Britain, though not less forceful in tone, could not equitably be accompanied by a hint of the same alternative. Arbitration by an international court was the final recourse on the British issues. Arbitration could not be resorted to, in the American view, for adjusting the issues with Germany.

The Anglo-American trade dispute over freedom of maritime commerce by neutrals during a war occupied an interlude in the crisis with Germany. The dispatch of the third Lusitania note of July 21, 1915, promised a breathing spell in the arduous diplomatic labors of the Administration, pending Germany's response. But a few days later the Administration became immersed in Great Britain's further defense of her blockade methods, contained in a group of three communications, one dated July 24, and two July 31, 1915, in answer to the American protests of March 31, July 14, and July 15, 1915. The main document, dated July 24, 1915, showed both Governments to be professing and insisting upon a strict adherence to the same principles of international law, while sharply disagreeing on the question whether measures taken by Great Britain conformed to those principles.

The United States had objected to certain interferences with neutral trade Great Britain contemplated under her various Orders in Council. The legality of these orders the United States contested. Great Britain was notified by a caveat, sent July 14, 1915, that American rights assailed by these interferences with trade would be construed under accepted principles of international law. Hence prize-court proceedings based on British municipal legislation not in conformity with such principles would not be recognized as valid by the United States.

Great Britain defended her course by stating the premise that a blockade was an allowable expedient in war—which the United States did not question—and upon that premise reared a structure (p. 030) of argument which emphasized the wide gap between British and American interpretations of international law. A blockade being allowable, Great Britain held that it was equally allowable to make it effective. If the only way to do so was to extend the blockade to enemy commerce passing through neutral ports, then such extension was warranted. As Germany could conduct her commerce through such ports, situated in contiguous countries, almost as effectively as through her own ports, a blockade of German ports alone would not be effective. Hence the Allies asserted the right to widen the blockade to the German commerce of neutral ports, but sought to distinguish between such commerce and the legitimate trade of neutrals for the use and benefit of their own nationals. Moreover, the Allies forebore to apply the rule, formerly invariable, that ships with cargoes running a blockade were condemnable.

On the chief point at issue Sir Edward Grey wrote:

"The contention which I understand the United States Government now puts forward is that if a belligerent is so circumstanced that his commerce can pass through adjacent neutral ports as easily as through ports in his own territory, his opponent has no right to interfere and must restrict his measure of blockade in such a manner as to leave such avenues of commerce still open to his adversary.

"This is a contention which his Majesty's Government feel unable to accept and which seems to them unsustained either in point of law or upon principles of international equity. They are unable to admit that a belligerent violates any fundamental principle of international law by applying a blockade in such a way as to cut out the enemy's commerce with foreign countries through neutral ports if the circumstances render such an application of the principles of blockade the only means of making it effective."

In this connection Sir Edward Grey recalled the position of the United States in the Civil War, when it was under the necessity of declaring a blockade of some 3,000 miles of coast line, a military operation for which the number of vessels available was at first very small:

(p. 031) "It was vital to the cause of the United States in that great struggle that they should be able to cut off the trade of the Southern States. The Confederate armies were dependent on supplies from overseas, and those supplies could not be obtained without exporting the cotton wherewith to pay for them.

"To cut off this trade the United States could only rely upon a blockade. The difficulties confronting the Federal Government were in part due to the fact that neighboring neutral territory afforded convenient centers from which contraband could be introduced into the territory of their enemies and from which blockade running could be facilitated.

"In order to meet this new difficulty the old principles relating to contraband and blockade were developed, and the doctrine of continuous voyage was applied and enforced, under which goods destined for the enemy territory were intercepted before they reached the neutral ports from which they were to be reexported. The difficulties which imposed upon the United States the necessity of reshaping some of the old rules are somewhat akin to those with which the Allies are now faced in dealing with the trade of their enemy."

Though an innovation, the extension of the British blockade to a surveillance of merchandise passing in and out of a neutral port contiguous to Germany was not for that reason impermissible. Thus that preceded the British contention, which, moreover, recognized the essential thing to be observed in changes of law and usages of war caused by new conditions was that such changes must "conform to the spirit and principles of the essence of the rules of war." The phrase was cited from the American protest by way of buttressing the argument to show that the United States itself, as evident from the excerpt quoted, had freely made innovations in the law of blockade within this restriction, but regardless of the views or interests of neutrals. These American innovations in blockade methods, Great Britain maintained, were of the same general character as those adopted by the allied powers, and Great Britain, as exemplified in the Springbok case, had assented to them. As to the American contention that there was a lack of written authority for the British (p. 032) innovations or extensions of the law of blockade, the absence of such pronouncements was deemed unessential. Sir Edward Grey considered that the function of writers on international law was to formulate existing principles and rules, not to invent or dictate alterations adapting them to altered circumstances.

So, to sum up, the modifications of the old rules of blockade adopted were viewed by Great Britain as in accordance with the general principles on which an acknowledged right of blockade was based. They were not only held to be justified by the exigencies of the case, but could be defended as consistent with those general principles which had been recognized by both governments.

The United States declined to accept the view that seizures and detentions of American ships and cargoes could justifiably be made by stretching the principles of international law to fit war conditions Great Britain confronted, and assailed the legality of the British tribunals which determined whether such seizures were prizes. Great Britain had been informed:

"... So far as the interests of American citizens are concerned the Government of the United States will insist upon their rights under the principles and rules of international law as hitherto established, governing neutral trade in time of war, without limitation or impairment by order in council or other municipal legislation by the British Government, and will not recognize the validity of prize-court proceedings taken under restraints imposed by British municipal law in derogation of the rights of American citizens under international law."

British prize-court proceedings had been fruitful of bitter grievances to the State Department from the American merchants affected. Sir Edward Grey pointed out that American interests had this remedy in challenging prize-court verdicts:

"It is open to any United States citizen whose claim is before the prize court to contend that any order in council which may affect his claim is inconsistent with the principles of international law, and is, therefore, not binding upon the court.

"If the prize court declines to accept his contentions, and if, after such a decision has been upheld on appeal by the judicial (p. 033) committee of His Majesty's Privy Council, the Government of the United States considers that there is serious ground for holding that the decision is incorrect and infringes the rights of their citizens, it is open to them to claim that it should be subjected to review by an international tribunal."

One complaint of the United States, made on July 15, 1915, had been specifically directed to the action of the British naval authorities in seizing the American steamer Neches, sailing from Rotterdam to an American port, with a general cargo. The ground advanced to sustain this action was that the goods originated in part at least in Belgium, and hence came within the Order in Council of March 11, 1915, which stipulated that every merchant vessel sailing from a port other than a German port, carrying goods of enemy origin, might be required to discharge such goods in a British or allied port. The Neches had been detained at the Downs and then brought to London. Belgian goods were viewed as being of "enemy origin," because coming from territory held by Germany. This was the first specific case of the kind arising under British Orders in Council affecting American interests, the goods being consigned to United States citizens.

Great Britain on July 31, 1915, justified her seizure of the Neches as coming within the application of her extended blockade, as previously set forth, which with great pains she had sought to prove to the United States was permissible, under international law. Her defense in the Neches case, however, was viewed as weakened by her citing Germany's violations of international law to excuse her extension of old blockade principles to the peculiar circumstances of the present war. In intimating that so long as neutrals tolerated the German submarine warfare, they ought not to press her to abandon blockade measures that were a consequence of that warfare, Great Britain was regarded as lowering her defense toward the level of the position taken by Germany. Sir Edward Grey's plan was thus phrased:

"His Majesty's Government are not aware, except from the published correspondence between the United States and Germany, (p. 034) to what extent reparation has been claimed from Germany by neutrals for loss of ships, lives, and cargoes, nor how far these acts have been the subject even of protest by the neutral governments concerned.

"While these acts of the German Government continue, it seems neither reasonable nor just that His Majesty's Government should be pressed to abandon the rights claimed in the British note and to allow goods from Germany to pass freely through waters effectively patrolled by British ships of war."

Such appeals the American Government had sharply repudiated in correspondence with Germany on the submarine issue. Great Britain, however, unlike Germany, did not admit that the blockade was a reprisal, and therefore without basis of law, on the contrary, she contended that it was a legally justifiable measure for meeting Germany's illegal acts.

The British presentation of the case commanded respect, though not agreement, as an honest endeavor to build a defense from basic facts and principles by logical methods. One commendatory view, while not upholding the contentions, paid Sir Edward Grey's handling of the British defense a generous tribute, albeit at the expense of Germany:

"It makes no claim which offends humane sentiment or affronts the sense of natural right. It makes no insulting proposal for the barter or sale of honor, and it resorts to no tricks or evasions in the way of suggested compromise. It seeks in no way to enlist this country as an auxiliary to the allied cause under sham pretenses of humane intervention."

The task before the State Department of making a convincing reply to Sir Edward Grey's skillful contentions was generally regarded as one that would test Secretary Lansing's legal resources. The problem was picturesquely sketched by the New York "Times":

"The American eagle has by this time discovered that the shaft directed against him by Sir Edward Grey was feathered with his own plumage. To meet our contentions Sir Edward cites our own seizures and our own court decisions. It remains to be seen whether out of strands plucked from the mane and tail of the (p. 035) British lion we can fashion a bowstring which will give effective momentum to a counterbolt launched in the general direction of Downing Street."[Back to Contents]

BRITISH BLOCKADE DENOUNCED AS ILLEGAL AND INEFFECTIVE BY THE UNITED STATES—THE AMERICAN POSITION

Secretary Lansing succeeded in accomplishing the difficult task indicated at the conclusion of the previous chapter. The American reply to the British notes was not dispatched until October 21, 1915, further friction with Germany having intervened over the Arabic. It constituted the long-deferred protest which ex-Secretary Bryan vainly urged the President to make to Great Britain simultaneously with the sending of the third Lusitania note to Germany. The President declined to consider the issues on the same footing or as susceptible to equitable diplomatic survey unless kept apart.

The note embraced a study of eight British communications made to the American Government in 1915 up to August 13, relating to blockade restrictions on American commerce imposed by Great Britain. It had been delayed in the hope that the announced intention of the British Government "to exercise their belligerent rights with every possible consideration for the interest of neutrals," and their intention of "removing all causes of avoidable delay in dealing with American cargoes," and of causing "the least possible amount of inconvenience to persons engaged in legitimate trade," as well as their "assurance to the United States Government that they would make it their first aim to minimize the inconveniences" resulting from the "measures taken by the allied governments," would in practice not unjustifiably infringe upon the neutral rights of American citizens engaged in trade and commerce. The hope had not been realized.

(p. 036) The detentions of American vessels and cargoes since the opening of hostilities, presumably under the British Orders in Council of August 20 and October 29, 1914, and March 11, 1915, formed one specific complaint. In practice these detentions, the United States contended, had not been uniformly based on proofs obtained at the time of seizure. Many vessels had been detained while search was made for evidence of the contraband character of cargoes, or of intention to evade the nonintercourse measures of Great Britain. The question became one of evidence to support a belief—in many cases a bare suspicion—of enemy destination or of enemy origin of the goods involved. The United States raised the point that this evidence should be obtained by search at sea, and that the vessel and cargo should not be taken to a British port for the purpose unless incriminating circumstances warranted such action. International practice to support this view was cited. Naval orders of the United States, Great Britain, Russia, Japan, Spain, Germany, and France from 1888 to the opening of the present war showed that search in port was not contemplated by the government of any of these countries.

Great Britain had contended that the American objection to search at sea was inconsistent with American practice during the Civil War. Secretary Lansing held that the British view of the American sea policy of that period was based on a misconception:

"Irregularities there may have been at the beginning of that war, but a careful search of the records of this Government as to the practice of its commanders shows conclusively that there were no instances when vessels were brought into port for search prior to instituting prize court proceedings, or that captures were made upon other grounds than, in the words of the American note of November 7, 1914, evidence found on the ship under investigation and not upon circumstances ascertained from external sources."

Great Britain justified bringing vessels to port for search because of the size and seaworthiness of modern carriers and the difficulty of uncovering at sea the real transaction owing to the intricacy of modern trade operations. The United States submitted (p. 037) that such commercial transactions were essentially no more complex and disguised than in previous wars, during which the practice of obtaining evidence in port to determine whether a vessel should be held for prize-court proceedings was not adopted. As to the effect of size and seaworthiness of merchant vessels upon search at sea, a board of naval experts reported:

"The facilities for boarding and inspection of modern ships are in fact greater than in former times, and no difference, so far as the necessities of the case are concerned, can be seen between the search of a ship of a thousand tons and one of twenty thousand tons, except possibly a difference in time, for the purpose of establishing fully the character of her cargo and the nature of her service and destination."

The new British practice, which required search at port instead of search at sea, in order that extrinsic evidence might be sought (i. e., evidence other than that derived from an examination of the ship at sea), had this effect:

"Innocent vessels or cargoes are now seized and detained on mere suspicion while efforts are made to obtain evidence from extraneous sources to justify the detention and the commencement of prize proceedings. The effect of this new procedure is to subject traders to risk of loss, delay and expense so great and so burdensome as practically to destroy much of the export trade of the United States to neutral countries of Europe."

The American note next assailed the British interpretation of the greatly increased imports of neutral countries adjoining Great Britain's enemies. These increases, Sir Edward Grey contended, raised a presumption that certain commodities useful for military purposes, though destined for those countries, were intended for reexportation to the belligerents, who could not import them directly. Hence the detention of vessels bound for the ports of those neutral countries was justified. Secretary Lansing denied that this contention could be accepted as laying down a just and legal rule of evidence:

"Such a presumption is too remote from the facts and offers too great opportunity for abuse by the belligerent, who could, if the rule were adopted, entirely ignore neutral rights on the high (p. 038) seas and prey with impunity upon neutral commerce. To such a rule of legal presumption this Government cannot accede, as it is opposed to those fundamental principles of justice which are the foundation of the jurisprudence of the United States and Great Britain."

In this connection Secretary Lansing seized upon the British admission, made in the correspondence, that British exports to those neutral countries had materially increased since the war began. Thus Great Britain concededly shared in creating a condition relied upon as a sufficient ground to justify the interception of American goods destined to neutral European ports. The American view of this condition was:

"If British exports to those ports should be still further increased, it is obvious that under the rule of evidence contended for by the British Government, the presumption of enemy destinations could be applied to a greater number of American cargoes, and American trade would suffer to the extent that British trade benefited by the increase. Great Britain cannot expect the United States to submit to such manifest injustice or to permit the rights of its citizens to be so seriously impaired.

"When goods are clearly intended to become incorporated in the mass of merchandise for sale in a neutral country it is an unwarranted and inquisitorial proceeding to detain shipments for examination as to whether those goods are ultimately destined for the enemy's country or use. Whatever may be the conjectural conclusions to be drawn from trade statistics, which, when stated by value, are of uncertain evidence as to quantity, the United States maintains the right to sell goods into the general stock of a neutral country, and denounces as illegal and unjustifiable any attempt of a belligerent to interfere with that right on the ground that it suspects that the previous supply of such goods in the neutral country, which the imports renew or replace, has been sold to an enemy. That is a matter with which the neutral vendor has no concern and which can in no way affect his rights of trade."

The British practice had run counter to the assurances Great Britain made in establishing the blockade, which was to be so (p. 039) extensive as to prohibit all trade with Germany or Austria-Hungary, even through the ports of neutral countries adjacent to them. Great Britain admitted that the blockade should not, and promised that it would not, interfere with the trade of countries contiguous to her enemies. Nevertheless, after six months' experience of the "blockade," the United States Government was convinced that Great Britain had been unsuccessful in her efforts to distinguish between enemy and neutral trade.

The United States challenged the validity of the blockade because it was ineffective in stopping all trade with Great Britain's enemies. A blockade, to be binding, must be maintained by force sufficient to prevent all access to the coast of the enemy, according to the Declaration of Paris of 1856, which the American note quoted as correctly stating the international rule as to blockade that was universally recognized. The effectiveness of a blockade was manifestly a question of fact:

"It is common knowledge that the German coasts are open to trade with the Scandinavian countries and that German naval vessels cruise both in the North Sea and the Baltic and seize and bring into German ports neutral vessels bound for Scandinavian and Danish ports. Furthermore, from the recent placing of cotton on the British list of contraband of war it appears that the British Government had themselves been forced to the conclusion that the blockade is ineffective to prevent shipments of cotton from reaching their enemies, or else that they are doubtful as to the legality of the form of blockade which they have sought to maintain."

Moreover, a blockade must apply impartially to the ships of all nations. The American note cited the Declaration of London and the prize rules of Germany, France, and Japan, in support of that principle. In addition, "so strictly has this principle been enforced in the past that in the Crimean War the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council on appeal laid down that if belligerents themselves trade with blockaded ports they cannot be regarded as effectively blockaded. (The Franciska, Moore, P. C. 56). This decision has special significance at the present time (p. 040) since it is a matter of common knowledge that Great Britain exports and reexports large quantities of merchandise to Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Holland, whose ports, so far as American commerce is concerned, she regards as blockaded."

Finally, the law of nations forbade the blockade of neutral ports in time of war. The Declaration of London specifically stated that "the blockading forces must not bar access to neutral ports or coasts." This pronouncement the American Government considered a correct statement of the universally accepted law as it existed to-day and prior to the Declaration of London. Though not regarded as binding upon the signatories because not ratified by them, the Declaration of London, the American note pointed out, had been expressly adopted by the British Government, without modification as to blockade, in the Order in Council of October 9, 1914. More than that, Secretary Lansing recalled the views of the British Government "founded on the decisions of the British Courts," as expressed by Sir Edward Grey in instructing the British delegates to the conference which formulated the Declaration of London, and which had assembled in that city on the British Government's invitation in 1907. These views were:

"A blockade must be confined to the ports and coast of the enemy, but it may be instituted of one port or of several ports or of the whole of the seaboard of the enemy. It may be instituted to prevent the ingress only, or egress only, or both."

The United States Government therefore concluded that, measured by the three universally conceded tests above set forth, the British policy could not be regarded as constituting a blockade in law, in practice, or in effect. So the British Government was notified that the American Government declined to recognize such a "blockade" as legal.

Stress had been laid by Great Britain on the ruling of the Supreme Court of the United States on the Springbok case. The ruling was that goods of contraband character, seized while going to the neutral port of Nassau, though actually bound for the blockaded ports of the South, were subject to condemnation. Secretary Lansing recalled that Sir Edward Grey, in his instruction (p. 041) to the British delegates to the London conference before mentioned, expressed this view of the case, as held in England prior to the present war:

"It is exceedingly doubtful whether the decision of the Supreme Court was in reality meant to cover a case of blockade running in which no question of contraband arose. Certainly if such was the intention the decision would pro tanto be in conflict with the practice of the British courts. His Majesty's Government sees no reason for departing from that practice, and you should endeavor to obtain general recognition of its correctness."

The American note also pointed out that "the circumstances surrounding the Springbok case were essentially different from those of the present day to which the rule laid down in that case is sought to be applied. When the Springbok case arose the ports of the confederate states were effectively blockaded by the naval forces of the United States, though no neutral ports were closed, and a continuous voyage through a neutral port required an all sea voyage terminating in an attempt to pass the blockading squadron."

Secretary Lansing interjected new elements into the controversy in assailing as unlawful the jurisdiction of British prize courts over neutral vessels seized or detained. Briefly, Great Britain arbitrarily extended her domestic law, through the promulgation of Orders in Council, to the high seas, which the American Government contended were subject solely to international law. So these Orders in Council, under which the British naval authorities acted in making seizures of neutral shipping, and under which the prize courts pursued their procedure, were viewed as usurping international law. The United States held that Great Britain could not extend the territorial jurisdiction of her domestic law to cover seizures on the high seas. A recourse to British prize courts by American claimants, governed as those courts were by the same Orders in Council which determined the conditions under which seizures and detentions were made, constituted in the American view, the form rather than the substance of redress:

(p. 042) "It is manifest, therefore, that, if prize courts are bound by the laws and regulations under which seizures and detentions are made, and which claimants allege are in contravention of the law of nations, those courts are powerless to pass upon the real ground of complaint or to give redress for wrongs of this nature. Nevertheless, it is seriously suggested that claimants are free to request the prize court to rule upon a claim of conflict between an Order in Council and a rule of international law. How can a tribunal fettered in its jurisdiction and procedure by municipal enactments declare itself emancipated from their restrictions and at liberty to apply the rules of international law with freedom? The very laws and regulations which bind the court are now matters of dispute between the Government of the United States and that of His Britannic Majesty."

The British Government, in pursuit of its favorite device of seeking in American practice parallel instances to justify her prize-court methods, had contended that the United States, in Civil War contraband cases, had also referred foreign claimants to its prize courts for redress. Great Britain at the time of the American Civil War, according to an earlier British note, "in spite of remonstrances from many quarters, placed full reliance on the American prize courts to grant redress to the parties interested in cases of alleged wrongful capture by American ships of war and put forward no claim until the opportunity for redress in those courts had been exhausted."

This did not appear to be altogether the case, Secretary Lansing pointed out that Great Britain, during the progress of the Civil War, had demanded in several instances, through diplomatic channels, while cases were pending, damages for seizures and detentions of British ships alleged to have been made without legal justification. Moreover, "it is understood also that during the Boer War, when British authorities seized the German vessels, the Herzog, the General and the Bundesrath, and released them without prize court proceedings, compensation for damages suffered was arranged through diplomatic channels."

The point made here was by way of negativing the position Great Britain now took that, pending the exhaustion of legal (p. 043) remedies through the prize courts with the result of a denial of justice to American claimants, "it cannot continue to deal through the diplomatic channels with the individual cases."

The United States summed up its protest against the British practice of adjudicating on the interference with American shipping and commerce on the high seas under British municipal law as follows:

"The Government of the United States has, therefore, viewed with surprise and concern the attempt of His Majesty's Government to confer upon the British prize courts jurisdiction by this illegal exercise of force in order that these courts may apply to vessels and cargoes of neutral nationalities, seized on the high seas, municipal laws and orders which can only rightfully be enforceable within the territorial waters of Great Britain, or against vessels of British nationality when on the high seas.

"In these circumstances the United States Government feels that it cannot reasonably be expected to advise its citizens to seek redress before tribunals which are, in its opinion, unauthorized by the unrestricted application of international law to grant reparation, nor to refrain from presenting their claims directly to the British Government through diplomatic channels."

The note, as the foregoing series of excerpts show, presented an array of legal arguments formidable enough to persuade any nation at war of its wrongdoing in adopting practices that caused serious money losses to American interests and demoralized American trade with neutral Europe. Great Britain, however, showed that she was not governed by international law except in so far as it was susceptible to an elastic interpretation, and held, by implication, that a policy of expediency imposed by modern war conditions condoned, if it did not also sanction, infractions.

Nothing in Great Britain's subsequent actions, nor in the utterances of her statesmen, could be construed as promising any abatement of the conditions. In fact, there was an outcry in England that the German blockade should be more stringent by extending it to all neutral ports. Sir Edward Grey duly convinced the House of Commons that the Government could not (p. 044) contemplate such a course, which he viewed as needless, as well as a wrong to neutrals.

As to the hostility of the neutrals to British blockade methods, Sir Edward Grey said:

"What I would say to neutrals is this: There is one main question to be answered—Do they admit our right to apply the principles which were applied by the American Government in the war between the North and South—to apply those principles to modern conditions, and to do our best to prevent trade with the enemy through neutral countries?

"If they say 'Yes'—as they are bound in fairness to say—then I would say to them: 'Do let chambers of commerce, or whatever they may be, do their best to make it easy for us to distinguish.'

"If, on the other hand, they answer it that we are not entitled to interrupt trade with the enemy through neutral countries, I must say definitely that if neutral countries were to take that line, it is a departure from neutrality."[Back to Contents]

GREAT BRITAIN UNYIELDING—EFFECT OF THE BLOCKADE—THE CHICAGO MEAT PACKERS' CASE

The existing restrictions satisfied Great Britain that Germany, without being brought to her knees, was feeling the pinch of food shortage. To that extent—and it was enough in England's view—the blockade was effective, the contentions of the United States notwithstanding. So Great Britain's course indicated that she would not relax by a hair the barrier she had reared round the German coast; but she sought to minimize the obstacles to legitimate neutral trade, so far as blockade conditions permitted, and was disposed to pay ample compensation for losses as judicially determined. The outlook was that American (p. 045) scores against her could only be finally settled by arbitral tribunals after the war was over. Satisfaction by arbitration thus remained the only American hope in face of Great Britain's resolve to keep Germany's larder depleted and her export trade at a standstill, whether neutrals suffered or not. Incidentally, the United States was reminded that in the Civil War it served notice on foreign governments that any attempts to interfere with the blockade of the Confederate States would be resented. The situation then, and the situation now, with the parts of the two countries reversed, were considered as analogous.

A parliamentary paper showed that the British measures adopted to intercept the sea-borne commerce of Germany had succeeded up to September, 1915, in stopping 92 per cent of German exports to America. Steps had also been taken to stop exports on a small scale from Germany and Austria-Hungary by parcel post. The results of the blockade were thus summarized: