Title: The Story of the Great War, Volume 6

Editor: Francis J. Reynolds

Allen L. Churchill

Francis Trevelyan Miller

Release date: July 12, 2009 [eBook #29385]

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/29385

Credits: Produced by Charlene Taylor, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected. Hyphenation and accentuation have been standardised, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.

Page 382: Words are missing in the sentence "The genuine leaders of the Socialists should [...] the labor organizations realized immediately the policy which the dark forces were initiating."

Index: Links in bolded blue are internal links, those in green link to the other volumes of this serie on the Gutenberg site and will be opened in a new window.

Major General John J. Pershing, appointed to organize and command the American forces in France, is shown landing in France on June 12, 1917. French officers and officials of high rank are there to welcome him. His arrival is recognized as an epoch-making date in the war, for it foreshadows the creation of a great American Army in France.

SOMME · RUSSIAN DRIVE

FALL OF GORITZ · RUMANIA

GERMAN RETREAT · VIMY

REVOLUTION IN RUSSIA

UNITED STATES AT WAR

VOLUME VI

P · F · COLLIER & SON · NEW YORK

Copyright 1916

By P. F. Collier & Son

PART I.—WESTERN FRONT—SOMME AND VERDUN

CHAPTER

PART II.—EASTERN FRONT

PART III.—THE BALKANS

PART IV.—AUSTRO-ITALIAN FRONT

PART V.—WAR IN THE AIR AND ON THE SEA

PART VI.—THE UNITED STATES AND THE BELLIGERENTS

PART VII.—WESTERN FRONT

PART VIII.—THE UNITED STATES AND GERMANY

PART IX.—THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

(p. 004) PART X.—EASTERN FRONT

PART XI.—AUSTRO-ITALIAN FRONT

PART XII.—WAR ON THE SEA

PART XIII.—WAR IN THE AIR

FRENCH AND BRITISH ADVANCES

The first month of the Allied offensive on the Somme front closed quietly. The British and French forces had every reason to feel encouraged over their successes. In the two thrusts since July 1, 1916, they had won from the Germans nearly twenty-four square miles of territory. Considering the extent to which every fraction of a mile was fortified and defended, and the thoroughness of the German preparations to make the district impregnable, the Allied gains were important. As a British officer said at the time, it was like digging badgers out of holes—with the proviso that every badger had machine guns and rifles at the hole's mouth, while the approach to each was swept by the fire from a dozen neighboring earthworks.

It was estimated that in the first month of the Allied offensive on the Somme the German casualties amounted to about 200,000 men, while the Anglo-French forces lost less than a fourth of that number. The Allies claimed to have captured about 13,000 prisoners and between sixty and seventy field guns, exclusive of machine guns and the smaller artillery.

With the capture of Pozières it might be said that the second phase of the Battle of the Somme was concluded. The Allied forces were well established on the line to which the second main "push" which began July 14, 1916, was directed.

During the first three days of August, 1916, comparative quiet prevailed along the Somme front, and no important offensive was (p. 010) attempted by either side. Minor fighting continued, however, every day, and during the nights the English positions were heavily bombarded by the German guns.

On the night of August 4, 1916, the British assumed the offensive, advancing from Pozières on a front of 2,000 yards. The attack, which seems to have taken the Germans by surprise, was entirely successful, as the British troops gained 1,000 yards of the German second line and captured over 400 prisoners. This second line consisted of two strongly fortified trenches running parallel, which were backed by a network of supporting and intermediate trenches, all strongly constructed, with deep dugouts and cunningly devised machinery of defense. When the Australians made the thrust forward from Pozières while the British cooperated on the left over the ground to the east of the village, they found when going over the enemy trenches that in many places the British guns had wrecked and almost obliterated the German second lines. After the British advance the Germans launched two spirited counterattacks, which were easily repulsed by the British artillery. The British casualties were unimportant, but the troops suffered intensely from the heat of the evening and from the gas masks that they were forced to wear, as previous to the attack the Germans had bombarded with gas shells.

Minor fighting and artillery duels continued intermittently until the morning of August 6, 1916, when the Germans delivered two fierce attacks on the ground gained by the British east of Pozières. The Germans, employing liquid fire in one attack, forced the British back from one of the trenches they had captured on August 4, 1916, but part of this was later regained. The following day the Germans continued their attacks north and northeast of Pozières on the new British lines. After heavy bombardment of the British positions, the Germans penetrated their trenches, but were forced out again, having suffered some casualties and leaving a number of prisoners in British hands. In front of Souchez the Germans exploded a mine, and here some of their troops succeeded in entering the English trenches over the crater, but were quickly bombed out again.

(p. 011) On the same date late in the afternoon the French forces to the north of the Somme carried out a well-planned attack which resulted in the capture of a line of German trenches between the Hem Wood and the river. The French took 120 prisoners and a number of machine guns.

On August 8, 1916, the British positions north and east of Pozières were heavily bombarded by German artillery. In the evening of the same date British troops pushing forward engaged the enemy near the station of Guillemont. A bomb attack made by the Germans on the eastern portion of the Leipzig salient south of Thiepval was driven back with some casualties. Two British raiding parties about the same time succeeded in entering the German lines north of Roclincourt and blew up some dugouts. On this date a squadron of ten German aeroplanes endeavored to cross the British lines on a bombing expedition, but were driven off by four British offensive patrols. Two of the German aeroplanes were forced to descend behind their own lines, while the others were scattered and did not return to attack. In the evening of the same day the Germans made four attacks on the British lines to the northwest of Pozières, and in one were successful in occupying a portion of a British trench.

During this day the French north of the Somme, while the British were fighting at Guillemont, advanced east of Hill 139, north of Hardecourt, and took forty prisoners. The Germans, making two attempts to recapture the trenches won from them by the French on the previous day, were beaten back, leaving a great number of dead on the field. In the evening French troops captured a small wood and a heavily fortified trench to the north of the Hem Wood, making their gains for the two days, an entire line of German trenches on a front of three and three-quarter miles and a depth of from 330 to 350 yards.

In the battered and shell-pitted region to the northwest of Pozières fighting between the British and German troops continued unceasingly. The slight gains made by the British troops were won only by the greatest risk and daring, for the whole plateau between Thiepval and Pozières (about 3,000 yards) lay open to the German fire from the former place. A great part of (p. 012) it could be reached by machine guns, while German batteries at Courcelette and Grandcourt commanded the ground at close range. A network of German trenches, well planned, stretched in almost every direction. Flares and shell fire made the region as bright as day during the night, and it was only by rushing a trench from saps made within a few feet of the objectives or by breaking into a trench and bombing along it that the British were able to achieve any small gains. And gains were made on this terrible terrain daily, though only a few yards might be won, and a dozen or more prisoners captured.

The British attack on the Germans around Guillemont, which took place as previously noted on August 8, 1916, was at first successful. A section of the troops carried some trenches, and then pushing on gained a useful piece of ground south of Guillemont with few casualties. Another (the left) section of British troops were unable to proceed farther on account of the darkness. Another section, owing to miscalculation, swept through the German trenches straight into the village of Guillemont, where they lost their direction amid the ruins and confusion. Working their way through the shattered streets they proceeded to dig themselves in when they had reached the far northeast corner of the place. With enemies all around them, and the breadth of the ruined village between them and their friends, the adventure could have but one conclusion. A few of the men succeeded in getting back to the British lines, but the remainder fell into the hands of the enemy.[Back to Contents]

FURTHER SUCCESSES—FRENCH CAPTURE MAUREPAS

In the morning of August 11, 1916, after the usual preparatory bombardment, French troops carried the whole of the third German position north of the Somme from the river northeast of Hardecourt—that is to say, on a front of about four miles and to an average depth of about a mile. This third German position consisted of three, and in some places of four, lines of trenches strongly defended and with the usual trench blockhouses. The French attacked in force along the whole front, and in eighty minutes, according to the description given in French newspapers, carried the German position at a small cost in casualties compared with results. The Germans fought bravely and stubbornly, but the French artillery did such effective work before the advance attack that in the hand-to-hand conflicts that followed the French troops readily overcame the enemy. A Bavarian battalion which garrisoned a blockhouse on Hill 109 offered such a determined resistance that when the victorious French finally entered the work they found only 200 of the garrison alive.

In the afternoon of the same day, August 11, 1916, French forces north of the Somme took several German trenches by assault and established their new line on the saddle to the north of Maurepas and along the road leading from the village to Hem. A strongly fortified quarry to the north of Hem Wood and two small woods were also occupied by the French troops. During the course of the action in this district they took 150 unwounded prisoners and ten machine guns.

British air squadrons numbering sixty-eight machines on August 12, 1916, bombed airship sheds at Brussels and Namur, and railway sidings and stations at Mons, Namur, Busigny, and Courtrai. Of the British machines engaged in these attacks, all but two returned safely. In the evening of the same day (p. 014) the British forces attacked the third German position which extended from the east of Hardecourt to the Somme east of Buscourt. On this front of about four miles the British infantry carried the trench and works of the Germans to a depth of from 660 to 1,100 yards. To the northwest of Pozières the British gained 300 to 400 yards on a front of a mile, and also captured trenches on the plateau northwest of Bazentin-le-Petit.

The French continued to make appreciable gains south of the Somme, carrying portions of trenches and taking some prisoners. The new British front to the west of Pozières was repeatedly attacked and bombarded by the Germans, and on August 15, 1916, they succeeded in recapturing trenches they had lost two days before. But they were unable to hold their gains for more than a day, when the British drove them out and consolidated the position.

During the afternoon and evening of August 16, 1916, German and French to the north and south of the Somme engaged in heavy bombardments. At Verdun the German lines were forced back close to Fleury, the French taking enemy trenches and smashing a counterattack with their artillery.

On the afternoon of August 17, 1916, there was hard fighting along the whole Somme front from Pozières to the river. The British gained ground toward Ginchy and Guillemont and took over 200 prisoners, including some officers. During the night the Germans delivered repeated attacks against the positions the British had captured, but only in one instance did they succeed in winning back a little ground.

On August 18, 1916, the British continued to add to their gains, advancing on a front of more than two miles for a distance of between 200 and 600 yards. As a result of these operations carried out along the British front from Thiepval to their right, south of Guillemont, a distance of eleven miles, was the gain of the ridge southeast of Thiepval commanding the village and northern slopes of the high ground north of Pozières. The British also held the edge of High Wood and half a mile of captured German trenches to the west of the wood. Advances were also made to the outskirts of the village of Guillemont, where the (p. 015) British occupied the railroad station and quarry, both of some considerable military importance. As a result of these operations the British captured sixteen officers and 780 of other ranks.

German guns continued to shell the British positions throughout the day and evening of August 18, 1916, but no infantry attacks were attempted. On the following day after a heavy bombardment the Germans made three vigorous bombing attacks on the British positions at High Wood, all of which were repulsed, though the Germans succeeded in some instances in gaining a foothold for a time in the British trenches. In the aggregate the British successes in this region had in a week resulted in the capture of trenches which, if put end to end, would reach for a number of miles.

On August 24, 1916, the French completed the capture of Maurepas, for which they had been battling for nearly two weeks, after seizing the trenches to the south of the village. Maurepas was of great military importance, for, with Guillemont on the British front, it formed advanced works of the stronghold of Combles. The attack was launched at five in the evening on a front of a mile and a quarter from north of Hardecourt to southeast of Maurepas. The French troops captured the German portion of Maurepas at the first dash, and a little later the strong intrenchments made by the Germans to cover the Maurepas-Combles road were in their possession. The victory was won over some of Germany's best troops, the Fifth Bavarian Reserve Division and the First Division of the Prussian Guard under Prince Eitel Frederick.

On the same day, August 24, 1916, the British troops on the north of the Somme attacked the German positions in the Maurepas region and carried with a rush that part of the village still held by the Germans and the adjoining trenches, taking 600 prisoners and eighteen guns. South of the village the Germans made a violent attack on the British position at Hill 121, but owing to the concentrated fire of artillery which mowed them down they were unable to reach the British lines at any point.[Back to Contents]

GERMAN COUNTERATTACKS

Throughout the week the Germans attempted repeatedly to retake the positions that had been won from them by the French and British troops. One of the most desperate attacks made was against the British positions between the quarry and Guillemont. After a heavy preparatory bombardment the Germans launched an attack that took them to the edge of the British trenches, where a desperate hand-to-hand struggle was made in which the Germans fought with stubbornness and determination, but were finally repulsed with heavy losses.

The new French positions gained at Maurepas were violently attacked on August 26, 1916, but the French artillery wrought terrible havoc among the German troops, and they withdrew in disorder. In two days the French took over 350 prisoners in this sector.

On the evening of August 26, 1916, the British captured several hundred yards of German trenches north of Bazentin-le-Petit and pushed forward some distance north of Ginchy.

After gaining a trench of 470 yards south of Thiepval and taking over 200 prisoners, the British on August 24, 1916, joined up with the French forces on the right, where important progress was made around Maurepas. Continued hard fighting on the eastern and northern edges of the Delville Wood advanced the British lines several hundred yards on each side of the Longueville-Flers road. These operations resulted in the British capturing eight officers and about 200 of other ranks.

West of Ginchy two German companies attacked the British trenches and were driven off by machine-gun fire. Bombardment of British positions continued during the night. Two aeroplane raids carried out by the British airmen damaged trains on the German line of communications. Important military points were also bombed with some success, but in encounters with German aircraft the British lost one machine.

(p. 017) The importance of the Thiepval sector to the Germans was demonstrated in their constant efforts to regain the positions there that had been captured by the British. A great number of guns were concentrated by the Germans in this sector. The bombardment which preceded the attack was of unusual violence, but owing to the intrepid spirit of the men from Wiltshire and Worcestershire, who defended the positions, the Germans were unable to reach the trenches and withdrew in disorder. According to an eyewitness of this attack, the first wave of German soldiers advancing to attack was thrown in disorder by the intense gunfire from the British positions. A second wave of men started—swept a little farther over the shell-torn terrain than the others had done, then faltered, broke apart, and fell back, having failed to get through the British artillery fire or even to approach their trenches.

In the area around Mouquet Farm and in the trenches south of Thiepval the British captured during the day one German officer and sixty-six of other ranks. British aircraft displayed great activity in this sector, dropping five tons of bombs on points of military importance behind the enemy lines. One hostile machine was brought down, while two British machines failed to return. South of the Ancre the British made slight advances, capturing four German officers and fifty-five of other ranks.

A great battle developed north of the Somme on September 2, 1916, in which the British and French forces took thousands of prisoners and captured important territory. After intense artillery preparation the French infantry cooperating with British troops attacked the German positions on a front of about three and three-quarter miles between the region north of Maurepas and the river. The strong German forces engaged were unable to resist the onslaught of the Allied troops. The villages of Forest, east of Maurepas, and Cléry-sur-Somme were captured, as well as all the German trenches along the route from Forest to Combles as far as the outskirts of the last place. The Germans launched with heavy forces a counterattack against the conquered positions, but were driven back by the heavy fire of the French batteries. The French official reports gave the number (p. 018) of unwounded prisoners captured in this battle as exceeding 2,000, and the booty taken included twelve guns and fifty machine guns. German aircraft which engaged British flyers during the progress of the battle were driven off with a loss of three machines destroyed and four badly injured. The British lost three.

Fighting on the Somme and Ancre was continued with increased severity on September 3, 1916. The Germans stubbornly contested the British advance, but were unable to gain any material advantage except at Ginchy, occupied by the British, who were driven out of all but a small portion of the place. As an offset to this loss the British troops captured the strongly fortified village of Guillemont and the German defenses on a front of one and two-third miles to an average depth of about 800 yards. The British took during this battle over 800 prisoners.

The new French positions to the north of Combles were violently attacked on this same date, but the German effort was broken by the machine-gun and artillery barrage. The French captured over 500 prisoners and ten machine guns.

South of the Somme, on a front of about twelve miles, the French troops attacked enemy organizations from Barleux to the region south of Chaulnes and were entirely successful in gaining their objectives.

Southwest of Barleux the French infantry in a single push carried three successive German lines and advanced over a mile, which brought them to the outskirts of Berny and Deniécourt. To the south, by a well-planned enveloping movement, the village of Soyécourt was carried, and here a whole Prussian battalion was cut off and surrendered after a short resistance. South of Vermandovillers, where the Germans occupied a portion of the village, the French launched an attack on the German front in the afternoon, but it was night before they could break through north of Chilly. The French pushed on through the breach, forcing the Germans to retire to their second line, leaving 1,200 prisoners, guns and machine guns in French hands. Desperate attempts were made by the German General von Hein to recover the lost ground. Before the French had time to consolidate their (p. 019) positions he launched six counterattacks, all of which failed under the French barrage of fire. On September 4, 1916, the French made 2,700 prisoners between Barleux and Chilly.[Back to Contents]

OPERATIONS AT VERDUN—BRITISH VICTORIES IN THE SOMME

The intense activity of the Allied forces in the Somme region in August and during the first week in September, 1916, exceeded in interest the happenings around Verdun. While only one building in the town remained uninjured by the shells which the Germans poured into it daily, the French, to whom the initiative had passed, continued to harry the enemy daily along the Thiaumont-Vaux front. Their "nibbling" process went on unceasingly, seizing some hundred yards of trenches, or taking batches of 200 or 300 prisoners with such frequency as to produce a decidedly depressing effect on the German commanders and on their troops, who in this sector represented the pick of the German army.

On September 6, 1916, a signal success was won by the French at Verdun when they carried the German line on the Vaux-Chapître Wood-Le Chenois front to a length of 1,000 yards, taking 250 prisoners and ten guns.

In the second week of September, 1916, the French and British forces made important gains in the Somme region. On September 9, 1916, British forces advancing on a front of 6,000 yards occupied Falfemont Farm, Leuze Wood, Guillemont, and Ginchy, the area gained being more than four square miles. The bravery displayed by the Irish troops from Connaught, Leinster, and Munster in connection with the capture of Guillemont was especially commended by headquarters. The same troops fought with distinction in the capture of Ginchy, a village only in name, for shell fire had reduced it to mere heaps of rubble and dust.

(p. 020) In an assault on the French front September 9, 1916, between Belloy-en-Santerre and Barleux the Germans by using jets of flame obtained a temporary footing in the French trenches, but were driven out by a vigorous counterattack with the loss of four machine guns. On the night of September 11, 1916, French forces north of the Somme took the offensive and drove a broad wedge right in between the powerfully defended German positions of Combles on the north and Péronne to the south. Continuing their advance on the following day, in less than half an hour they carried the German first line and, taking Hill 145 by the way, pressed on to the Bapaume road south of Rancourt, and held it as far south as Bouchavesnes village which was captured by a brilliant dash early in the evening. On September 13, 1916, the French again advanced, carrying several positions and occupying in this region the German third line. They also captured a trench system south of Combles. In the two days' fighting 2,300 German prisoners were captured.

On the night of Thursday, September 13, 1916, the British forces won German trenches to the southeast of Thiepval and a heavily fortified place known as Wunderwerk. This was the prelude to a series of brilliant victories won by the British troops which had not been surpassed during the entire fighting in the Somme area. At 6 a. m. on September 15, 1916, the British attacked on a front of about six miles, extending from Bouleaux Wood east of Guillemont to the north of the Albert-Bapaume road. A tremendous bombardment of the enemy positions continued for twenty minutes before the infantry advanced to attack. The Germans were believed to have 1,000 guns concentrated in this sector which had been shelling the British positions for several days, but during this battle for some reason, perhaps lack of ammunition, they played an unimportant part, and were far outclassed by the British artillery.[Back to Contents]

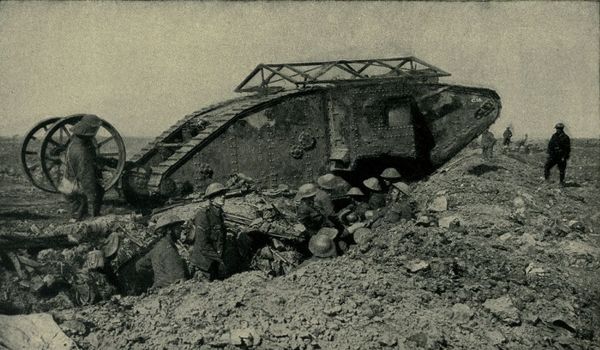

THE "TANKS"—BRITISH CAPTURE MARTINPUICH

It was in this battle that the British for the first time introduced a new type of armored cars which proved veritable fortresses on wheels, and came to be popularly known as "tanks." These destructive engines of warfare were from twenty to forty feet long and were painted a dull drab, or some unassuming color calculated to blend with the tones of the landscape. In a dim light they suggested the giant slugs of a prehistoric age. Sliding along the ground on caterpillar wheels, with armored cheeks on each side of the head, above which guns stuck out like the stalked eyes of land crabs, their first appearance in this sector may well have created consternation among the German troops who saw them for the first time. There was something uncanny about these steel-scaled monsters that slid over the ground as it were on their stomachs, balanced by a flimsy tail supported on two wheels. Weighing many tons, when the "tank" came to an obstacle, such as a house or wall, it rammed the obstruction with its full weight, and then climbing over the débris lumbered on its way. Through vast craters and muddy shell holes and over trenches the monsters waddled along, scattering death and destruction as they advanced. The German soldiers, after the first consternation caused by the appearance of these war engines in the field, bravely attacked them; swarming over the sides of the "tanks" and seeking to batter in the steel scales and armored plates and to silence the guns that spouted fire from the head, but the daring efforts were useless and caused many casualties. Machine-gun fire was also ineffectual. They could only be disabled by a direct hit from a large gun. It is said that the Germans voiced their disgust for this kind of warfare, and protested that the British were not fighting fair!

At first the Germans thought they could rush a "tank" as they would a fort, and lost heavily in such futile attacks; they could (p. 022) make no impression on the steel "hide" of the monsters. Once astride a trench, the guns of the tank could rake right and left, mowing down the defenders whose volleys pattered harmlessly on the steel plates of the war engine.

A young Australian who served in one of these new war machines described "tanksickness" as being as bad as seasickness until you became accustomed to the constant plunges and lurchings as the "tank" encountered obstacles on its way. The Australian noted down his impressions while cruising around the German lines in a "tank." A few quotations from his diary may be of interest:

"Peppering begun at once. Thought old thing was going to be drowned in a shower of bullets. Germans dashed up from all sides. We fired at them point-blank. The survivors had another try. More of them went down.... A rain of bullets resumed. It was like as if hundreds of rivets were being hammered into the hide of the 'tank.' We rushed through.... Got right across a trench. Made the sparks fly. Went along parapet, routing out Germans everywhere. Tried to run, but couldn't keep it up under our fire. Threw up the sponge and surrendered in batches."

"One can hardly imagine any spectacle more terrifying," said an eyewitness, "than these monsters must have presented to German eyes when, after a hurricane bombardment, through the smoke and dust of bursting shells, the great shapes came lumbering forward in the gray light of dawn. The enemy evidently had no hint of what they were. They emptied their rifles at them, and the things came rolling on. They turned on their machine guns, and the bullets only struck sparks from the great beasts' awful sides. In several places they sat themselves complacently astride of the trench, and swept it in both directions and all the ground beyond with their machine guns. Against strong points they were invaluable, because they could thrust themselves, secure in the toughness of their hide, in close quarters where unprotected infantry could never get. In woods they trampled their way through the undergrowth and climbed over or broke down barricades, contemptuous of the machine guns (p. 023) and rifle fire which made the approach of unarmored men impossible."

During this advance the British penetrated the third German line, which was shattered at all points. Three new villages—Flers, Martinpuich, and Courcelette—fell into British hands and more than twenty miles of German trenches were taken. Over 100 officers and 4,000 other ranks were captured by the British.

Martinpuich, which was known to be strongly fortified by the Germans, was the first trench to be carried by the British troops almost without a check. Beyond this was a series of other trenches and fortified positions in shell holes and the like. And here the "tanks" did effective service, their appearance creating consternation among the German troops, whose gunfire was powerless to injure or to impede the triumphal progress of these ungainly forts on wheels. In one instance a German battalion commander surrendered to a "tank" and was taken on board as a passenger. Up to the outskirts of Martinpuich there was stiff fighting and the village itself bristled with machine guns. The Germans stubbornly and bravely contested the British advance through the ruins. The British troops, however, continued to push forward almost yard by yard until the whole place was in their hands, and they had dug themselves in in a line on the farthest eastern and northern sides of the village.

Before the hour set for the advance the British troops who took Courcelette were strongly attacked by the Germans on the front just north of the Bapaume road. The British front-line trench was broken by the attack, and hard fighting was in progress when the hour set for the British advance arrived. Then from support lines and other positions to the rear of the trench the Germans had entered the British troops swept forward. The Germans were overwhelmed as the waves of khaki-clad, cheering men rushed forward and over them and out beyond the objective points as originally planned. In front of Courcelette there were formidable German positions; two trenches in particular which had been strongly fortified and against which the British troops for a time hurled themselves in vain. Twice the British troops were driven back, but the third assault was (p. 024) entirely successful, the British troops sweeping over the two trenches and into the outskirts of Courcelette. By 8.10 o'clock the British forces had worked clear through the village ruins and had carried two especially strong positions on the farther side, a quarry on the north and a cemetery on the northeast of the village.

In the High Wood area, to the right of the two attacks described, the Germans had converted a large mine crater into a fortress of formidable strength, for from this position they could sweep the entire wood with machine guns so placed that the British were powerless to reach them. The "tanks" were of great efficiency in reducing this strong point on the eastern angle of the wood. The British troops fighting every yard of the way, slowly encircled the wood, which was still full of cunningly hidden machine guns, and then went steadily through it. This wood, which was described as a horrible place, with its heaps of dead and shattered defenses, was effectually cleaned out by the British and occupied by them, and a line was established due north of the farthest extremity for about 1,000 yards.

Flers was captured by the British by successive pushes in which the "tanks" again demonstrated their value. Leading the way, these monsters waddled through the village, shattering barricades, crushing their way through masonry and creating general alarm among the German troops, who saw these formidable war engines for the first time.

In the capture of Courcelette, Flers, and Martinpuich the British air service successfully cooperated with the movements of the artillery and infantry. During the day, September 15, 1916, thirteen German aeroplanes and kite balloons were destroyed, and nine others were driven down in a damaged condition. The British reported that four of their machines were lost.

On the following day, September 16, 1916, the Germans attacked the British positions around Flers and along the Les Bœufs road, and were beaten off. The British line which had been held and lived in for a day was now little more than a series (p. 025) of shell holes linked by a shallow trench. Though "the air was stiff with bullets" as an officer described it, the British troops climbed out of their shattered position and pushing on took possession of a more satisfactory trench ahead, where they consolidated and sat down. This last small advance cost the British more casualties than all the other operations during the two days' fighting.[Back to Contents]

CAPTURE OF COMBLES—AIR RAIDS

Meanwhile the Allied troops—the French on the south, the British on the north—made steady progress in hemming in Combles. The French increased their gains by storming Le Priez Farm and against severe attacks held their gains north and south of Bouchavesnes. In another dashing attack they took by assault a group of German trenches south of Rancourt, some of their troops pushing forward to the edge of the village. South of the Somme they advanced east of Deniécourt and northeast of Berny, taking several hundred prisoners and ten machine guns. The closing-in process around Combles went steadily forward.

In the evening of September 17, 1916, the British forces in the vicinity of Courcelette extended their gains on a front of 1,000 yards, captured a strong fortification known as the Danube Trench on a mile front, and also the strongly defended work at Mouquet Farm which had been fought over for several weeks. On the same date the French made a spirited attack south of the Somme, wresting from the Germans what portions they still held of the villages of Vermandovillers and Berny, the ground between the two, and also between Berny and Deniécourt, breaking up all counterattacks and taking 700 prisoners.

On September 18, 1916, the British on the Somme front continued to add to their gains of the previous days. Northwest of Combles they captured a strongly fortified German work and, (p. 026) beating off numerous counterattacks north of Flers, took six howitzers, two field guns and lighter pieces, as well as some prisoners. South of this the British took another section of German trenches, and by a counterattack won back trenches to the east beyond Mouquet Farm which they had lost on previous days.

On the same date the French took the village of Deniécourt, making the third village captured by them in two days. During these operations over 1,600 prisoners were taken, including twenty-five officers.

Owing to the weather conditions, little progress was made by the Allied forces on September 19, 1916. Raids were successful, however, on enemy trenches northeast of Bethune, and the French made some advance and took prisoners east of Berny. The Germans made five spirited attacks against the French front in Champagne where the Russian detachments were posted, all of which were repulsed with heavy losses by the guns and machine guns. From 9 in the morning until nightfall of the following day the Germans continued their assaults on the French lines, but only here and there did they make even temporary progress.

On Thursday, September 21, 1916, the British line in the west was again advanced. A section of the German front about a mile long was attacked between Martinpuich and Flers. Two lines of German trenches were captured in this push. Meanwhile the French continued to develop their hemming in of Combles, nibbling their way forward, taking prisoners and guns, a slow but determined advance that the Germans could not restrain.

British guns displayed great activity on Friday, September 22, 1916, when they destroyed ten hostile gun pits, damaged severely fourteen others, and blew up five ammunition pits. About the same time fifty aeroplanes raided an important railroad junction, destroyed several ammunition trains, and caused violent explosions and conflagrations.

September 25, 1916, was a notable day in the history of the Allied advance in the west, when French and British forces (p. 027) again assumed the offensive. The German positions were stormed on a front of about six miles between Combles and Martinpuich to a depth of more than a mile. The strongly fortified villages of Les Bœufs and Morval with several lines of trenches were captured. Morval, standing on a height north of Combles, with its subterranean quarries and maze of wire entanglements, constituted a formidable citadel of defense. By the capture of these villages German communication with Combles was cut off. The British took a large number of prisoners and immense quantities of war material.

About noon of the same date the French attacked the German positions between Combles and Rancourt and the defenses from the latter village to the Somme. Rancourt was taken after a sharp struggle, and the French lines were advanced to the northeast of Combles as far as the southern outskirts of Frégicourt. East of the Bethune road the French positions were extended for half a mile, while farther south several systems of German trenches were captured in the vicinity of the Cabal du Nord.

On the second day of the Allied offensive the French and British continued their successful advance. Combles, which the Allied troops had been closing in on for some days, was captured. Here an enormous quantity of booty, munitions, and supplies which the Germans had stored away in the subterranean regions of the place fell to the victors.

The subsequent capture of Gueudecourt by the French and British forces completed the notable advance of the Allies on September 25, 1916. They were now in possession of the ridge that dominates the valley of Bapaume, having cleared a stretch of ground on the far side of the crest to a distance of half a mile. In the night of September 26, 1916, the British troops captured Thiepval and the strongly fortified ridge east of it, which included an important stronghold, the Zollern Redoubt. The British reported the capture of over 1,500 prisoners during the two days' fighting.[Back to Contents]

BRITISH CAPTURE EAUCOURT L'ABBAYE-REGINA TRENCH

September 30, 1916, marked the close of the third month of Allied fighting in the Somme region. Since September 15, 1916, seven new German divisions were brought against the British and five against the French. According to reports from British headquarters in France, the British troops had engaged thirty-eight German divisions, of which twenty-nine had been forced to withdraw in a broken and exhausted state. During the three months' campaign the Allied forces captured over 60,000 German prisoners, of which number the British claimed to have taken 26,735. Besides other war material the Allies recovered from the Somme battle fields 29 heavy guns and howitzers, 92 field guns and howitzers, 103 trench artillery pieces, and 397 machine guns.

In the afternoon of October 1, 1916, the British troops assaulted the double-trench system of the main German third line over a front of about 3,000 yards from beyond Le Sars to a point 1,000 yards or so east of Eaucourt l'Abbaye. The British troops in the center, directly in front of Eaucourt l'Abbaye, were held up by the complicated defenses there, but the troops on the right, carrying everything before them, swept over the main lines of trench east of the place until well beyond it they occupied positions on the north, which they held against all German assaults. The center was meanwhile reenforced by the arrival of "tanks," which accomplished useful work in clearing the trenches; these were then occupied by the British troops. On October 2, 1916, German forces succeeded in pressing through a gap in the British line, and again occupied trenches before the village, while the British continued to hold their positions on the farther side, some of which were a thousand yards to the rear of the enemy. The following day the British heavily bombarded Eaucourt l'Abbaye and drew the cordon tighter around it. October 4, 1916, they (p. 029) assumed the offensive, and driving the Germans out of their trenches, filled up the gap and entered the town. Eaucourt l'Abbaye, with its old monastic buildings furnished with immense cellars, crypts and vaults, offered admirable conditions for prolonged defense. More important than the occupation of this place was the capture by the British of the positions around it with over 3,000 yards of the long-prepared German third line. These gains were won by the British troops at considerable cost in casualties, while the Germans also lost heavily.

The important part played by the "tanks" in this successful operation is worthy of record. One of these machines becoming disabled, continued for some time to operate as a stationary fortress. Later the "tank" became untenable and the crew were forced to abandon it. While this was being done the commanding officer of the "tank" was somewhat severely wounded so that he could not proceed. Two unwounded members of the crew refused to leave the wounded officer, and for more than two days they stayed with him in a shell hole between the lines. While hiding in this dangerous position the wounded officer was again struck by a bullet, but it was found impossible to get him away until the British captured the positions around the town.

There was intermittent shelling of the British front south of the Ancre during the night of October 4, 1916. A successful raid was carried out by a London territorial battalion in the Vimy area on the following day, and an assault on the British trenches east of St. Eloi was repulsed. October 6, 1916, was unmarked by any important offensive on the part of the belligerents. The Germans continued to shell heavily the British front south of the Ancre. Three British raiding parties succeeded in penetrating German trenches in the Loos area and south of Arras.

An important success was won by the British on the following day, October 7, 1916, when Le Sars—their twenty-second village—was captured. The Germans evidently anticipated the attack, for they had massed a large number of troops on a short front. The town itself was held by the Fourth Ersatz Division, and the ground behind Eaucourt l'Abbaye by a Bavarian division. The place, though strongly fortified, did not offer the resistance that (p. 030) the British troops expected. Their first forward sweep carried them to a sunken road that ran across the village at about its middle, and a second rush after the barrage had lifted brought them through the rest of the place and about 500 yards beyond on the Bapaume road. In Le Sars itself six officers and between 300 and 400 other ranks were made prisoners by the British. The Bavarians between Le Sars and Eaucourt fought with stubborn valor and gave the British troops plenty of hard work. Owing to the complication of fortified positions, trenches, and sunken roads, the ground in this section of the fighting area presented many difficulties. To the northeast of Eaucourt the determined pressure of the British troops caused the Bavarian resistance to crumble and the victors swept on and out along the road to Le Barque. At other points the British pierced the German lines and occupied positions midway between Eaucourt and the Butte de Warlencourt. To the left, a mile or so back, in what was known as the Mouquin Farm region, the British troops pushed forward in the direction of Pys and Miraumont, and all that part of Regina Trench over which there had been much stiff fighting was held by them. German troops had recovered a small portion of the front-line trenches they had lost to the north of Les Bœufs. In this sector on the night of October 7, 1916, the British guns shattered two attempted counterattacks and gathered in three officers, 170 men, and three machine guns. To the north of the Somme the French infantry cooperating with the British army attacked from the front of Morval-Bouchavesnes and carried their line over 1,300 yards northeast of Morval. During this advance over 400 prisoners, including ten officers, were captured, and also fifteen machine guns. Large gatherings of German troops reported north of Saillisel were caught by the concentrated fire from the French batteries.

In the region of Gueudecourt the British advanced their lines and beat off a furious attack made on the Schwaben Redoubt north of Thiepval on October 8, 1916. This repulse of the Germans was followed by the British troops winning some ground north of the Courcelette-Warlencourt road. In two days they took prisoner thirteen officers and 866 of other ranks.

(p. 031) The British continued their daily policy of making raids on the German trenches. Several were carried out on October 10, 1916, in the Neuville-St. Vaast and Loos regions, where trenches were invaded, three machine-gun emplacements destroyed, and a large number of prisoners taken. On the same date there was intense artillery activity on the Somme between the French and Germans. The French fought six air fights and bombed the St. Vaast Wood. To the south of the river the French troops took the offensive and attacked on a front of over three miles between Berny-en-Santerre and Chaulnes. Here the French infantry by vigorous fighting captured the enemy position and certain points beyond it. They also captured the town of Bovent, and occupied the northern and western outskirts of Ablaincourt and most of the woods of Chaulnes. During this offensive more than 1,250 Germans were taken.[Back to Contents]

CONTINUED ALLIED ADVANCE

Unceasing activity on the part of the Germans on October 11, 1916, showed that the recent successes of the Allies had by no means dampened their ardor or impaired their morale. All day long they shelled the British front south of the Ancre, especially north of Courcelette. Here the Germans attempted an attack, but were caught on their own parapets and stopped by the British barrage. Two German battery positions were destroyed here by bombing from aeroplanes. Two British aircraft engaged seven hostile machines, one of which was destroyed and two others were severely damaged. Behind the German front British aeroplanes bombed railway stations, trains, and billets, losing during these air fights four machines.

In the afternoon of this date, October 11, 1916, the British troops by a determined push gained 1,000 yards between Les Bœufs and Le Transloy, having gained all the territory they set out to win. The advance, which was won at a comparatively (p. 032) small cost, brought the British lines within 500 yards of one of the few conspicuous landmarks in this desolate region—a cemetery about half a mile from Le Transloy.

The English continued to make night raids on the German trenches. Five such raids undertaken October 11-12, 1916, in the Messines, Bois Grenier, and Haisnes areas were all successful; heavy casualties were inflicted on the Germans and a number of prisoners were taken. During the day of October 12, 1916, the British attacked the low heights between their front trenches and the Bapaume-Péronne road, where they gained ground and made captures. On this date the French infantry north of the Somme made progress to the west of Sailly-Saillisel. South of the Somme French forces took the offensive on October 14, 1916, delivering an attack west of Belloy-en-Santerre, by which they gained possession of the first German line on a front of about a mile and a quarter. By another attack they captured the village of Génermont and the sugar refinery to the northeast of Ablaincourt. In these two attacks nearly 1,000 prisoners were taken, including seventeen officers.

On the same date British forces in the neighborhood of the Stuff Redoubt and Schwaben Redoubt cleared two lines of German communication trenches for a distance of nearly 200 yards. During these operations, which were carried out by a single company, the British took two officers and 303 of other ranks. In the evening the British advanced their lines northeast of Gueudecourt and made further captures of men and material.

On Sunday, October 15, 1916, south of the Somme, the Germans made desperate attempts to regain the trenches they had lost to the French southeast of Belloy-en-Santerre, but the attacks were shattered by the French artillery.

French assaults by the German troops were repulsed on the following day when the French carried a wood between Génermont and Ablaincourt, taking prisoner four officers and 110 of other ranks, as well as a number of machine guns. The German aircraft were especially active on this day and the French fought seven engagements. In the Lassigny sector a German machine hit by French guns fell in flames behind its own lines.

(p. 033) The clear weather which prevailed during the day of October 16, 1916, tempted British airmen to renewed activity. They bombed successfully railway lines, stations, and factories. During the numerous fights in the air three German machines were destroyed and one was driven to earth, while two kite balloons were forced down in flames. For these successful exploits the British paid somewhat heavily. One of their machines was brought down by German gunfire and six were missing at the end of the day.

Heavy bombardments on both sides, trench raids, and counterattacks, which resulted in some successes for the Allied troops, marked the following days. On October 21, 1916, the Germans lost heavily in an attempt to recover Sailly-Saillisel from the French. Three regiments of the Second Bavarian Division recently arrived in this sector were shattered one after the other by French curtain and machine-gun fire. South of the Somme a brilliant little success was achieved by the French north of Chaulnes. Early in the afternoon the French infantry after a heavy bombardment of the enemy lines pushed forward and gained a foothold in the Bois Étoile which was held by troops of Saxony.

The Chaulnes garrison attempted to come to the support of the Saxons, but were driven back by the destructive fire from French batteries. Generals Marchand and Ste. Clair Deville, who were wounded in fighting in the Somme region, continued to hold their commands and to direct the action of the French troops under them.

Early in the morning of October 21, 1916, German troops in considerable force attacked the Schwaben Redoubt north of Thiepval occupied by the British, and at several points succeeded in entering the trenches. But in a short time the British troops by a vigorous attack drove them out, capturing five officers and seventy-nine of other ranks. A subsequent attack by the British, delivered on a front of some 5,000 yards between Schwaben Redoubt and Le Sars, advanced the British line from 300 to 500 yards. Sixteen officers and over 1,000 German prisoners were taken during this operation, while the British losses were said (p. 034) to be slight. On this same date British aircraft showed great activity, bombing German communications, an important railroad junction, and an ammunition depot, while there were several air duels in which the British destroyed three machines and drove others behind their lines. Two British aeroplanes were not heard from again.

In the afternoon of the following day, October 22, 1916, the British right wing advanced east of Gueudecourt and Les Bœufs and captured 1,000 yards of German trenches. On the same day British airmen bombed two railway stations behind the enemy's lines, hitting a train and working great damage to buildings and rolling stock. The British airmen in a series of engagements brought down seven German machines, damaging others and forcing them to descend. At the close of the day eight British machines were missing.[Back to Contents]

FRENCH RETAKE DOUAUMONT

On October 24, 1916, on the Verdun front a great victory was won by the French in the capture of Fort Douaumont. This stronghold, which had been termed by the Germans "the main pillar of the Verdun defenses," had been captured by the Brandenburgers in the last week of February, 1916. The French lost the fort, but they clung desperately to the approaches, which for weeks were the scenes of bloody struggles. The fort was retaken by the Allied troops on May 22, 1916, but after two days of furious bombardment and the attacks of fresh German troops they were driven from the place. From that time until the French recaptured it on October 24, 1916, it had remained in German possession. Shortly before noon of the last date the French launched their attack on the right bank of the Meuse after an intense artillery preparation. The German line, attacked on a front of about four and a half miles, was broken (p. 035) through everywhere to a depth which attained at the middle a distance of two miles.

General Nivelle had intrusted the plans for the recapture of Fort Douaumont to General Mangin. Artillery preparation began on October 21, 1916, when the air was clear and favored observation by captive balloons and aeroplanes. For two days the fort and its approaches were subjected to an almost continuous bombardment of French guns. On October 23, 1916, the explosion of a bomb started a fire in Fort Douaumont. The shelters covering the quarries of Haudromont were destroyed and also the battery at Damloup, while the ravines were blown to pieces. Owing to the wide extent of the French attacks the Germans seemed to have been in doubt as to the point from which the main assault would be launched. Gradually the French "felt out" the positions of the 130 German batteries, a great number of which they destroyed.

The troops selected by the French for their attack belonged to divisions that had been fighting for some time in this sector. According to the French official account of the storming of the fort, from left to right was the division of General Guyot de Salins, reenforced on the left by the Eleventh Infantry. This division was made up of Zouaves and Colonial sharpshooters, among them the Moroccan regiment which had previously been honored for heroic conduct at Dixmude and Fleury, and to whom fell the honor of attacking Fort Douaumont. Then came the division commanded by General du Passage, consisting of troops from all parts of France. A division commanded by General Bardmelle, composed of troops of the line and light infantry, came next, and a battalion of Singhalese also took an equal part in the attack.

At 11.40 a. m. the attack was launched in a heavy fog. It had been planned that the first stroke should take in the quarries of Haudromont, the height to the north of the ravine of La Dame, the intrenchment north of the farm of Thiaumont, the battery of La Fausse-Côte, and the ravine of Bazite. In the second phase, after an hour's stop to consolidate the first gains, the French troops were to press on to the crest of the heights to the north of (p. 036) the ravine of Couleuvre, the village of Douaumont, the fort of Douaumont, the dam and pond of Vaux, and on to the battery of Damloup.

The French attack succeeded in carrying out the first phase of the plan with insignificant losses, and proceeded almost immediately to advance to the second objective. "At 2.30 p. m.," said a French eyewitness of the attack, "the fog lifted and the observers could see a magic spectacle. It was our soldiers, filing like so many shadows along the crest of Douaumont, approaching the fort from all sides. Arriving at the fort, they quickly established themselves within, and through field glasses could be seen the long column of prisoners as they filed out.

"The French Fourth Regiment, charged with taking the quarries of Haudromont, went beyond their objective, which was the trench of Balfourier. The division under General Guyot de Salins had taken Thiaumont and Douaumont, while that of General du Passage had seized the wood of Caillette and advanced to the heights of La Fausse-Côte.

"Steadily foot by foot the French infantry pushed on, driving the enemy before them and taking 3,500 prisoners on the way, till at last after a severe struggle around Fort Douaumont they shot all of its defenders who refused to surrender and won it back to France."

In the space of four hours the French had recaptured territory which had taken the Germans eight months to conquer at a cost of several hundred thousand of their best troops. The Germans explained their defeat on the ground that the fog hampered their observation and barrage, while the French artillery had set fire to a store of benzine in the fort, which forced the garrison to evacuate.

In addition to the fort and village adjoining, the French forces captured the Haudromont quarries which had been in possession of the Germans since April 18, 1916.[Back to Contents]

GERMANS LOSE FORT VAUX—FRENCH TAKE SAILLISEL

On the Somme front the operations of the Allied troops were impeded by heavy rains, but artillery duels continued daily; the British airmen made many raids on enemy positions and were successful in bombing depots and railways. October 27, 1916, an aerial combat took place in which many machines were engaged. Five aeroplanes fell during the fight, two of which were British.

On Saturday morning, October 28, 1916, the British troops carried out a successful operation northeast of Les Bœufs, which resulted in the capture of enemy trenches. The Germans driven from their position were caught by the British rifle fire and lost two officers and 138 of other ranks. On the following day the British won another trench from the Germans to the northeast of Les Bœufs.

In summing up the gains of the Allies during the month of October, 1916, it will be noted that they had made steady progress. The British forces had won the high ground in the vicinity of the Butte de Warlencourt, which brought them nearer to the important military position of Bapaume. The French had by ceaseless activity pushed forward their lines toward Le Transloy. During four months from July 1 to November 1, 1916, the Franco-British troops in the course of the fighting on the Somme had captured 71,532 German soldiers and 1,449 officers. The material taken by the Allies during this period included 173 field guns, 130 heavy guns, 215 trench mortars, and 981 machine guns.

After the French victory on October 24, 1916, when Fort Douaumont was captured from the Germans, it was inevitable that Fort Vaux on the same front must also fall, and this took place on November 2, 1916. For some days Fort Vaux had been subjected to intense artillery fire by the French, and the German (p. 039) commander ordered the evacuation of the fortress during the night. It was in defending this stronghold against overwhelming odds that the French Major Raynal and his garrison won the praise of even their enemies. The German direct attack on the fort began March 9, 1916, and for ninety days Major Raynal held it against the ceaseless attacks of Germany's finest troops backed not by batteries, but by parks of artillery. Only when the fort was in ruins and the garrison could fight no longer were the German troops able to occupy the work. The French Government marked its appreciation of Major Raynal's heroic defense by publishing his name and by conferring on him the grade of Commander of the Legion of Honor, a distinction usually reserved only for divisional generals. The German Crown Prince appreciating Major Raynal's heroic qualities permitted him on his surrender to retain his sword.

North of the Somme, despite the persistent bad weather, the French troops on November 1 and 2, 1916, captured German trenches northeast of Les Bœufs and a strongly organized system of trenches on the eastern outskirts of St. Pierre Vaast Wood. By these operations the French took 736 prisoners, of whom twenty were officers, and also twelve machine guns.

The British forces on the Somme on the night of November 2, 1916, by a surprise attack captured a German trench east of Gueudecourt and carried out a successful raid on German trenches near Arras. British aircraft, which had been actively engaged in bombing German batteries, in the course of several combats in the air destroyed two hostile machines. On November 4, 1916, the Germans attempted by a counterattack to regain the trenches won by the British near Gueudecourt, but were driven off with heavy losses, considering the number of troops engaged. The Germans left on the field more than a hundred dead, and the British captured thirty prisoners and four machine guns. British aircraft, which continued to operate despite the heavy weather that prevailed, suffered heavily on November 4, 1916. One of their machines which had attacked and destroyed a German aeroplane was so badly damaged that it fell within German lines and four other British aircraft did not return.

(p. 040) German attempts to wrest from the French the trenches they had won on November 1, 1916, on the western edge of St. Pierre Vaast Wood were unsuccessful, though at some points the German troops succeeded in penetrating the lines. But their foothold in the French trenches was only temporary, and they were driven out with considerable losses.

On Sunday, November 5, 1916, the French took the offensive south of the village of Saillisel, attacking simultaneously on three sides the St. Pierre Vaast Wood, which had been strongly organized by the German troops. As a result of this spirited attack the French captured in succession three trenches defending the northern horn of the wood, and the entire line of hostile positions on the southwestern outskirts of the wood. At this point the fighting was of the most desperate description. The Germans fought with great bravery, making violent counterattacks, which the French repulsed with bomb and bayonet, and capturing during the operations on this front 522 prisoners, including fifteen officers.

The British troops, which had won 1,000 yards of a position on the high ground in the neighborhood of the Butte de Warlencourt on November 5, 1916, were forced to relinquish a great part of their gains when the Germans made a violent attack on the following day.

North of the Somme the French made important advances between Les Bœufs and Sailly-Saillisel. To the south on November 6, 1916, in the midst of a heavy rain they launched a dashing attack on a front of two and a half miles. German positions extending from the Chaulnes Wood to the southeast of the Ablaincourt sugar refinery were carried, and the whole of the villages of Ablaincourt and Pressoir were occupied by the French infantry. Pushing forward their lines they also captured the cemetery to the east of Ablaincourt, which had been made into a stronghold by the Germans. The French positions were farther carried to the south of the sugar refinery as far as the outskirts of Gomiécourt. In these successful operations the French captured over 500 prisoners, including a number of officers.[Back to Contents]

BRITISH SUCCESSES IN THE ANCRE

In the Ancre region the British won some notable victories on November 12, 1916, when Beaumont-Hamel was taken, which the Germans considered an even more impregnable stronghold than Thiepval. The British also swept all before them on the south side of the Ancre, capturing the lesser village of St. Pierre Divion. The defeats which the British had suffered in this region during July of 1916 were amply atoned for by these victories. Beaumont-Hamel lies in the fold of a ridge and was honeycombed with dugouts and the defenses so cunningly prepared that it was extremely difficult for the British artillery to destroy them. Under Beaumont-Hamel there is an elaborate system of caves or cellars dating from ancient days, and it was the emergence of the German troops from the dugouts and these lairs that made the attack of the Ulster troops in July unavailing. Attacking simultaneously northward, down the nearer slope, and eastward directly against the face of the main German line before Beaumont-Hamel, the British troops captured the whole position at once.

The entire front on which the British attacked was over 8,000 yards. On the right, or east, the advance began from the western end of Regina Trench from the British position about 700 yards to the north of Stuff Redoubt. From this point a German trench known as the Hansa line ran northwestward to the Ancre, directly opposite the village of Beaucourt. On the extreme right, north of Stuff Redoubt, to reach that trench meant an advance of only a score or so of yards. To the westward, above Schwaben Redoubt half a mile, the advance was nearly 1,000 yards. By St. Pierre Divion, along the valley of the Ancre itself, the advance was over 1,500 yards. Everywhere in this sector the British troops were successful. They gained in this offensive a stretch of 3,000 yards north of the Ancre to an average depth of about a mile. The victory of the British troops was especially (p. 042) notable, because they had struck frontally at the main German first line with tier upon tier of trenches which the Germans had strongly fortified and wired for two years past. One English county battalion alone to the south of Beaumont-Hamel took 300 prisoners, and in the village itself 700 were captured, mostly soldiers from Silesia and East Prussia. At the close of the day over 2,000 German prisoners had been taken, and the ground won by the British amounted to about four square miles. During the night of November 12, 1916, and during the day following in the clean-up of the labyrinthian defenses which the Germans had skillfully constructed 2,000 more prisoners were added to the number already captured in this sector. The British advance had brought them to the outskirts of Beaucourt-sur-Ancre, which was taken on November 14, 1916. Pushing on through the village to the left of it, the British troops advanced over the high ground to the northeast of Beaumont-Hamel, on to the road from Serre to Beaucourt, having gathered in another thousand prisoners on the way.

During the two days' fighting in this region no British troops won greater distinction than the Scots and the Royal Naval Division. In all the German lines in France there was no more formidable position than the angle immediately above the Ancre, where Beaumont-Hamel lay in a hollow of the hill. On the morning of November 13, 1916, the Royal Naval Division attacked the stretch from just below the "Y" ravine on the south of Beaumont-Hamel to the north side of the Ancre. After a preliminary bombardment, which played havoc with the German barbed-wire entanglements protecting their front line, the British naval troops swept over the line with a rush as if the barriers had been made of straw. The British right rested on the Ancre as they swept across the valley bottom. Northwest, where there was a rise of ground, the center of the line had to attack diagonally along the slope of the hill. At the top of the slope there was a German redoubt hidden in a curve, and invisible in front, composed of a triangle of three deep pits with concrete emplacements for machine guns which could sweep the slope in all directions. This formidable redoubt was situated immediately (p. 043) behind the German front trench, reaching back to, and resting on, the second. At all points the British naval troops carried the front trench by storm. On the right they rushed along the valley bottom and the lower part of the slope, carrying line after line of trench on to the dip where a sunken road ran along their front going up from the Ancre to Beaumont-Hamel on the left.

Here for a short space of time the British troops rested while others, also of the Naval Division, came up and swept through them on and up the slope until they had won a line beyond. After this the first line caught up with them again, and they all swept on together in a splendid charge that covered a good 1,500 yards and which brought them to the very edge of Beaucourt. It was during this operation that a British battalion commander was wounded, but continued to lead and animate his men during the entire advance.

Meanwhile the British right center was held up by the redoubt. The German machine guns, while checking the troops in front of them, also swept the ground along the face of the slope to the left.

Here the troops of the Royal Naval Division suffered badly, but they continued to advance under the withering fire, winning the first and second line trenches, and then, as supports came up on the right, braving the machine-gun fire, they pushed on across the dip and sunken road up the slope toward Beaucourt. Here all the troops made a junction, forming a line on the Beaucourt-Beaumont-Hamel road. Back of this line the Germans still held the central parts of the trenches, over the two ends of which the British troops had swept. The redoubt still remained intact and other important positions were in German hands.

On the night of the 13th the British battalion commander who had been wounded during the advance gathered together 600 men, all that could be spared, from established positions, and with these troops he purposed to attempt a farther advance. It was while he was gathering these men together that the officer received a second wound, but still refused to retire from the field.

(p. 044) At early dawn of November 14, 1916, this officer led his 600 men against the village of Beaucourt. In less than a quarter of an hour's hand-to-hand fighting the British troops had won the village. When the sun shone on the scene of the struggle the British troops were digging themselves in on the farther side of Beaucourt. It was only then that the brave battalion commander who had successfully led the attack with four wounds in his body had to be taken to the rear.

It was on November 14, 1916, in the fighting on the Ancre that the Scots won special distinction. Their line in the fighting was just above that taken by the Naval Division, and included Beaumont-Hamel itself and the famous "Y" ravine. This ravine was such a formidable place that it merits a somewhat detailed description. Imagine a great gash in the earth some 7,000 or 8,000 yards in total length. In form like a great "Y" lying on its side, the prongs at the top projected down to the German front line while the stem ran back connecting with the road through the dip which goes from Beaumont-Hamel on the north to the Ancre. At the forked or western end, projecting down to the front, there is a chasm more than thirty feet deep, with walls so precipitous that in some parts they overhang. The Germans had burrowed into the sides of the earth and established lairs far below the thirty feet level of the ravine, where they were practically out of reach of shell fire coming from whatever direction. In some instances they had hollowed out great caves large enough to contain fully a battalion and a half of men. In addition, the thoroughgoing Germans had made a tunnel from the forward end of the ravine to their own fourth line in the rear. Altogether the position was admirably adapted to sustain a long defense and it was owing to the darkness when the British attacked, and which took the Germans by surprise, that the stronghold was captured. The violent artillery bombardment by the British before the attack had battered all the ordinary trenches and positions to pieces without effecting any serious damage to the underground shelters. Following the bombardment, the Scotch troops broke over the German defenses, meeting their only check in the onward rush at the ends of the "Y" ravine. On (p. 045) the south of this narrow point, keeping step with the Naval Division on their right, they swept across the first and second lines to the third. Here there was stiff fighting for a time, and when the Scots had struggled forward they left behind a trench full of German dead. On the north side every foot of ground was contested before the third line was reached, and then from both sides the ravine was attacked with bombs. At a point just behind the fork of the "Y" the first breach was made, and down the sheer sides of the ravine the British troops dropped with bayonet in hand. Then followed a stubborn struggle, for the Germans filled both sides of the chasm. Bombing, bayoneting, and grappling hand to hand continued for some time, the Germans despite their bravery being slowly forced back. At this stage of the fighting the British delivered a new frontal attack against the narrow bit of the front line still unbroken at the forward end of the "Y." As the Germans at that end turned to repel the assault the Scotch troops in the ravine rushed forward to be joined presently by other British troops that had by this time broken into the ravine, when there followed a scene of indescribable confusion. The struggle, however, was of short duration, when the Germans, at first singly and then in groups, flung down their arms and surrendered. All the Germans visible were made prisoners, but it was known that the tunnel and the shelters and dugouts contained many men. A shrewd Scotch private who had lived in Germany succeeded by strategy in drawing out most of the Germans from their hiding places. The canny Scot took a German officer who had surrendered, and leading him to suspected dugouts bade him order the men inside to come out. This ruse worked happily and at one dugout fifty Germans issued forth and surrendered.

While this struggle in the ravine was going on, other Scotch troops had swarmed over the German lines higher up, and by noon had taken possession of the site—there is no village—of Beaumont-Hamel. The place is underlaid with many subterranean hiding places, and it was during the process of gathering in the Germans concealed in these underground shelters that some extraordinary incidents took place. One example of personal (p. 046) bravery at this time must be cited. While the fighting was still going on a man of the British Signal Corps was running telephone lines up, and had just reached his goal in a captured German trench when he was struck down before the mouth of a dugout. Just as he collapsed a German officer appeared from the depths, and "Signals" could see that there were a number of German soldiers behind him. By a supreme effort the wounded man struggled to his feet and ordered the officer to surrender. This the German was quite ready to do. The Scot then pulled himself together and with his remaining strength telephoned an explanation of the situation back over the line which he had just laid. Having done this he stood guard over the German officer in the opening of the dugout, keeping others blocked behind him, until relieved of his charges by the arrival of help. As a whole the Scots took over 1,000 prisoners and gathered in fifty-four machine guns in the day's fighting.

No doubt the British successes in this area were gained by the unexpectedness and dash of their attacks which took the Germans by surprise. The foggy weather which prevailed had hampered the Germans so that they were unable to observe the movements of British troops.

In the region to the south of the Ancre a relief was going on, so that there was double the usual number of Germans in the trenches. The relieving division, the Two Hundred and Twenty-third, one of the Ludendorff's new formations and going into action for the first time as a division, was caught within a few minutes after getting to the trenches. Again the "tanks" were found of special service, though owing to the heavy mud encountered during the advance they were considerably hampered in their movements. At one point north of the Ancre a "tank" was useful in clearing the German first-line trench, and at another point south of the river one pushed forward and got ahead of the British infantry into a position strongly held by the Germans who swarmed around it and tried to blow it up with bombs. The "tank" stood off the furious assaults until the British infantry came up, when it became busy and helped the troops clean up the trenches and dugouts in the vicinity.[Back to Contents]

OPERATIONS ON THE FRENCH FRONT—FURTHER FIGHTING IN THE ANCRE

While the British were winning one of their most important victories on the Somme on the French front both north and south there was continued activity. The whole village of Saillisel, over which there had been prolonged fighting, was now in French hands. Heavy attacks by the German troops assisted by "flame throwers" were repulsed. Southeast of Berny the Germans succeeded in penetrating the French trenches, but were thrust out by a keen counterattack.

During the fighting in these sectors the French took 220 prisoners, seven officers, and eight machine guns.