"I'm afraid it'll have to go to the same place as my German pipe went—the dustbin. It suited me, too."

Title: Punch or the London Charivari, Vol. 147, December 16, 1914

Author: Various

Release date: August 9, 2009 [eBook #29652]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Neville Allen, Malcolm Farmer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

T. P.'s Weekly, in some sprightly lines, suggests that Punch should appear daily. This would certainly not be a whit more strange than to issue a T. P.'s Weekly Christmas Number as is done by our contemporary.

Answer to a Correspondent.—Yes, khaki is the fashionable colour for plum-puddings for the Front.

Post hoc propter hoc? Extract from the Eye-Witness's description of the KING'S visit to France:—"Another sight which excited the King's keen interest was the large bathing establishment at one of the divisional headquarters.... From here the procession returned to General Headquarters, where his Majesty received General Foch and presented him with the Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath."

Sir John French's praise of the Berkshire Regiment will surprise no one, least of all Mr. Punch's Toby.

Reuter tells us that when De Wet arrived at Johannesburg he was looking haggard and somewhat depressed. This lends colour to the rumour that he was annoyed at being captured.

In a letter published by a German newspaper a Landwehr officer writes:—"On the German front officers and men do not salute in the usual way, but by saying, 'God punish England,' while the reply is, 'May He punish England.'" This admission that the Germans themselves cannot do it is significant.

Die Post, in a reference to our million recruits, says, "Mere figures will not frighten us." Frankly, some of the figures of the stout Landwehr men frighten us.

At last in Constantinople there are signs that it is being realised that the Germans are driving the Turkish Army to Suez-side.

When the Germans and the Russians both claim to have won the same battle, what can one do? asks a correspondent. We can only suggest that the matter should be referred to the Hague Tribunal.

An item of war news which the President of the Society for the Promotion of Propriety thinks the Censor might very well have censored:—"To the south of Lask the Russian troops took Shertzoff."

"The Grenadier Guard, 6 ft. 7 in. high, whom the Prince of Wales noticed in hospital, is not the tallest man in the British Army, that distinction being claimed for Corporal Frank Millin, 2nd Coldstream Guards, who is 6 ft. 8½ in." This, again, is the sort of paragraph which might have been censored with advantage, for we are quite sure that, if the Prince of Wales's giant sees it, it will cause a relapse.

For the first time for many years there were no charges of murder at the December Sessions at the Old Bailey. It looks as if yet another of our industries has been filched by the Germans.

The Secretary of the Admiralty announces that candidates for assistant-clerkships, Royal Navy, who have completed a period of not less than three months' actual military service with His Majesty's Forces since mobilisation, will be granted fifty marks in the examination. It seems a most unpatriotic proceeding to pay them in German money.

The Nursing Times must really be more careful or we shall have the German newspapers drawing attention to atrocities by the French. In its issue of the 5th inst. our contemporary says:—"The 'Train unit' whose names we gave some weeks ago have waited all this time for their call for duty.... And now the French authorities have cut the train—and the staff—in two!"

Reply to those who think it absurd to take precautions against invasion:—It's the Hun-expected that always happens.

A great fall of cliff occurred last week between Beachy Head and Seaford, and the Germans are pointing out that the break-up of England has now begun in earnest.

"I'm afraid it'll have to go to the same place as my German pipe went—the dustbin. It suited me, too."

"Her thoughts came back to the dancing little figure in purple-striped pyjamas. She had a scared sense of irrevocable breaches."

An obvious misprint in the last word.

This is the method which the Kaiser means to try for his coming invasion of England.

"Professor G. Sims Woodhead, the Board's consultative bacteriological adviser, to whom the report had been submitted, said: 'I consider Dr. Mair's work contains a germ of great promise.'"

We hope the Professor will not lose sight of the promising young microbe.

"For any enemy ship to try to get into Dover at the present time would be like entering the mouth of hell.

[We understand that the Admiralty have received no condemnation of this.]"

We hope that none of our contemporaries will blame the Admiralty for its lack of information.

"Rev. Owen S. Watkins, one of the Wesleyan Methodist Chaplains with the Expeditionary Force (already mentioned in the dispatches), tells some most extraordinary stories of his experiences at the Front."

We remember now some mention of this "Expeditionary Force" being made in despatches, and we wondered at the time why the Censor allowed such a public reference to it.

The Russians quietly evacuated Lodz without the loss of a single man. The Germans allege that they captured it after strenuous fighting.

[Lines for King Albert's Book, published to-day for the benefit of The Daily Telegraph's Belgian Relief Fund.]

You that have faith to look with fearless eyes

Beyond the tragedy of a world at strife,

And trust that out of night and death shall rise

The dawn of ampler life;

Rejoice, whatever anguish rend your heart,

That God has given you, for a priceless dower,

To live in these great times and have your part

In Freedom's crowning hour.

That you may tell your sons who see the light

High in the heaven, their heritage to take:—

"I saw the powers of darkness put to flight.

I saw the morning break!"

In some respects one is no doubt compelled to admire the foresight of those gentlemen who are writing the History of the War while it is in progress, but as Mabel (my wife and very able colleague) justly observes, no History of the War, however copious or however fully illustrated, can be considered complete without a few salient details of the campaign by which The Snookeries (our domestic stronghold in Tooting) was saved from the fate of Belgium.

That omission I propose to remedy. Peace hath her strategy no less than War.

For some time prior to the Declaration of War it was evident that the butcher, the baker, and other foes of our domestic happiness were gathering for an onslaught. The attitude of the butcher was particularly uncompromising: I do not hesitate to describe it as distinctly Hun-ish. Diplomacy gave little hope of preserving peace, so that I was not altogether surprised when the war opened with a heavy bombardment. A brigade of small accounts advanced in skirmishing order, but were disposed of without trouble.

Mabel suggested a temporary withdrawal to the sand-dunes of Mudville-on-Sea, but I pointed out that this meant sacrificing part of our scanty store of ammunition and had the further disadvantage of cutting us off from our base of supplies in the City, to say nothing of losing touch with Uncle Robert, who has so often proved a staunch ally in a crisis.

We therefore resolved to entrench ourselves behind the Moratorium and prepared for a stubborn resistance. From this strong position we were able to sustain without loss a brisk fire of explosive missives which continued unchecked for some weeks. Speaking quite candidly, and dropping the language of the Press Bureau for the moment, there has never been a time when the postman's rat-tat has occasioned me less emotion.

The defences of the Moratorium did not save us from sundry annoying raids upon our supplies, the butcher being peculiarly active in this kind of warfare. I repeat, the butcher is a true Hun and must be sternly dealt with after the Peace. I was forced to silence him temporarily with a few shots from my new one-pounders.

I would like to say what a valuable weapon the one-pounder has proved in this campaign. It is wonderfully mobile and saves the waste of heavier ammunition. My only regret is that we were not armed with more of them.

Towards the end of August the rate-man and the gas-man mounted heavy ordnance upon official heights. They got our range to a nicety and threatened us in flank. I despatched Mabel at once to Uncle Robert, and with his assistance we were enabled to silence the enemy's howitzers, not, however, before the rate-man—a remorseless and persistent foe—had landed a "sheriff's officer" (as we jocularly term his missiles) into our dining-room. Little material damage was done, but for some days the effect upon the moral of our forces was apparent.

I must not forget to speak of Mabel's brilliant victory over the milkman, whose attack she frustrated by a threat to open negotiations for obtaining supplies from his hated rival. When these troubles are happily over I must certainly see that Mabel receives a decoration.

Towards the end of October our entrenchments behind the Moratorium became untenable, but by that time we had received substantial reinforcements and were easily able to hold our own against the enemy's reckless frontal attacks. The landlord suddenly unmasked a very strong battery which created some consternation. He himself appeared in force, but, thanks to the vigilance of my outposts, I was enabled to make a strategic retirement by the back-garden gate, leaving Mabel to foil the enemy by a ruse-de-guerre. (Dear Mabel is wonderfully clever at these things.) I succeeded in regaining my position under cover of darkness.

The attacks of the landlord were renewed with such vigour that I called a council of war to discuss the situation. Retreat being out of the question, Mabel suggested a levy of our last reserves, and the charwoman (who is a discreet person of considerable experience in such matters) was mobilised. In this way we secured a sufficient force to rout the landlord on his next appearance.

The last few days have been comparatively quiet. Mabel's dressmaker and my tailor have reaffirmed their neutrality, and we have promise of further support, if needed, from Uncle Robert. Thus, although the enemy appear to contemplate a new attack in the future, we are full of confidence.

In conclusion, I must not forget to refer to the very able way in which Mabel out-manœuvred the coal-man. Before he could unlimber, she had deftly poured in a rapid fire of sympathy for the slackness of trade from which she knew he must be suffering, and followed this up by an order for two tons of the best Wallsend.

I think I am justified in advancing the theory that there are no flies on dear Mabel.

[To an old nautical air, with Mr. Punch's loud congratulations to Vice-Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee and his brave sailors.]

Hardened steel are our ships;

Gallant tars are our men;

We never are wordy

(Sturdee, boys, Sturdee!),

But quietly conquer again and again.

The Hon. Treasurer of the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street (where many Belgian children are being cared for) desires to express his sincere thanks to Mr. Punch's readers for their generous response to the appeal for help which was recently made in these pages.

Private Atkins. "FOR WHAT WE HAVE RECEIVED—AND ARE GOING TO RECEIVE—HERE'S TO THE A.S.C."

Child (much impressed by martial emblems opposite). "Mother, is that a soldier?"

Mother. "No, darling."

Child. "Why not?"

(From Mrs. James Prosser, 25, Paradise Road, Brixton.)

Kaiser,—Jim's gone. I don't know if you'll like to hear it, him being a good fighter. I'd warrant him to take the shine out of any two Germans I ever met. They're big men, the Germans, but they mostly run to fat after their premmer jewness, as the Belgian lady over the way said last week when we was a-talking about 'em. I don't know what she meant, but she didn't look as if it was anything in the way of a compliment. That's why I've wrote it down here.

Anyhow, Jim's gone. I saw him off with a lot of others, and they was all singing and shouting as loud as their lungs would let 'em—not drink, mind you, so don't you run away with that notion, but just high spirits and health and happiness. First it was "Tipperary," and that made me feel so mournful I had to give Jim a good old hug, and the little un pulling at my dress all the time and calling out, "Let me have a go at him, Mother," and "Don't give 'em all to Mother, Dad; keep half-a-dozen for me," just as sensible as a Christian, which is more than you can say of some. His name's Henery, the full name, not Henry, and we had him christened so, to make sure. He's going on for five years now, and he's got a leg and a chest on him to suit twice his years. I'm not saying that because I'm his mother, but because it's the truth. After they'd sung "Tipperary" they sang a lot of other songs. There was one in particklar that I liked, it had such a go with it. Jim told me it was made up by one of their own men, music and all. I misremember most of it, but there was two lines stuck in my head:—

General French is a regular blazer,

He's going to dust the German Kaiser.

There was a lot more about theirselves and their officers and their colonel, who was second to none and was making tracks for the German Hun, all as funny and clever as you could make it. I couldn't help laughing to see 'em all so jolly. Then the engine give a whistle and the guard said, "Stand back," and waved his green flag, and the train moved out, and the men cheered and we cheered back, and at last they was gone, and the little un was saying, "Don't mind me, mother. Have a good cry and get it over;" and then we went home, and he kept talking all the way of what he's going to do when he grows up to be a soldier himself.

Well, Jim's gone, but I wouldn't have had him stay at home not for ever so much. He was earning good money, too, in his job, but that's going to be kept open for him so as he can drop into it again when he comes back. And I'm going to keep his home open for him so as he can drop into that when he comes back; there's enough money coming in to make certain of that, what with allowances and my work. Mind you, I like to work; it keeps you from thinking too much, and me and the little un manage splendid together. He helps about the house better nor half-a-dozen housemaids, and he's so managing it would make you die of laughing to see him. The only trouble is he can't bear going to bed; but I tell him if he don't the Kaiser'll catch him, and then he's off with his clothes and into his cot like a flash of lightning.

There, I've talked about myself and the little un and all the time I meant to tell you about Jim. However, you'll know him right enough if ever you come up against him. He's a handsome man with black hair and no moustache, and he's got a scar over his right eye where he tumbled against the fender when he was four years old.

Yours without love,

Genial Pedestrian. "A bright moon to-night, constable."

Morbid P.C. "Yes, Sir. Let's 'ope it don't draw the fire of 'ostile

air-craft!"

Dear Charles,—As the men, for reasons best known to themselves, will suddenly chant on the march—"We're here because we're here, because we're here, because we're here," goodness knows when (if ever) we shall get to the Front; so this is yet another letter for you from the Back, where we are, much against our will, kept to deal kindly but firmly with the German invader as, home-sick and sea-sick, he alights gloomily on our shores. If, by the way, I have given hints in this correspondence as to the disposition of any part of our troops, it is a comfort to think that the artful spy who gets hold of them will have the utmost difficulty in making up his mind as to the real or fictitious existence of (1) my Division; (2) my Brigade; (3) my Battalion; (4) my Company; or even (5) me.

Meanwhile we are in a very difficult position, such as I believe few soldiers have ever been called upon to face. You will remember how, four months ago, we collected ourselves together in accordance with our long-standing engagement to protect these islands against the foreign trespasser, the condition of our contract being that our service should begin (as charity should) and end (as charity often does) at home. In the bad old days when I was at the Bar I should of course have known that contracts are apt to turn round on those who make them; but now I am only a plain soldier and I am unable to understand why I should be made to stay at home when I desire to go and make a nuisance of myself abroad. But the real trouble comes from this, that some six weeks ago I received written and explicit orders to the effect that I was to sail forthwith.

Suppose this had happened to you and you had been given special leave of forty-eight hours to make all necessary preparations, would not you have gone where your more impressionable acquaintances and friends were gathered together in the greatest numbers, informing them of the position and doing, on the strength of it, a quiet but irretrievable swank? No ostentation, mark you, and nothing approaching a boast, but just a suspicion of a brave careless laugh, a voice just slightly choked with emotion and but a formal reluctance to accept the numerous and costly gifts proffered by relatives who at less emotional times would have grudged you a Christmas card?

We did. We went home and were made a fuss of; we took our leave and nice things were said to us, tears welled, and hands, peculiarly firm or peculiarly tender as the case might be, held ours for rather longer than the customary period. With a brave "Pooh! Pooh! It doesn't matter in the least," we went off at last, off amid deafening cheers to the unknown future....

The following week-end we were home again as before, but, since the joy of a temporary reprieve may outweigh even the annoyance of an anticlimax, they were pleased to see us and gave us another farewell only slightly less emotional than the last. But on the third of this series of week-ends a note of insincerity crept into the "Goodbye, old man," and the hand-pressure was slightly curtailed.

Alas! there have been even more week-ends since that. I trust it is only our self-consciousness makes us think that we are looked upon as frauds, who have obtained by false pretences the field-glasses, electric torches, knitted wares, tears, hand-clasps and choicest superlatives of our friends. It becomes worse as time passes; we do not go home now, and we would even refrain from writing if we could hope by that means to have our whereabouts unknown and our existence doubtful. If the authorities won't part with us, they might at least give us an address which would make it look as if they had—something like "Capt. Blank, Blankth Blank Regt., Blankth Fighting Force, c/o G.P.O." What will happen is that we shall go suddenly and without time to explain, and, when our friends are told, their faces will cloud over, not with sorrow at our departure but with annoyance at being pestered with the news of it again. It is a hard life, is a soldier's!

One bold bad private informed our most youthful orderly officer, upon being asked if he had had a sufficient breakfast: "Yes, thank you, Sir: a glass of water and a woodbine;" otherwise personal idiosyncracies become less marked, since individualities become merged in the corporate machine. The battalion is cross as a whole, nervy as a whole, laughs as a whole, almost sneezes or has indigestion as a whole. Recalling the good old days of annual camps, when energy used to be rewarded with free beer rather than demanded as a matter of course, the battalion as often as not sings as a whole while route-marching at ease past the C.O.:—

"Nobody knows how dry we are,

Nobody knows how dry we are,

Nobody knows how dry we are,

And nobody seems to care."

While the conduct of all of us becomes every day more disciplined, our speech, I have to report with regret, becomes more loose. Emphasis is an essential of military life, and it must be such emphasis as the least intelligent may readily appreciate. Sometimes I tremble to think in what terms I may inadvertently ask some gentle soul later on in life to pass the marmalade, or with what expletives I may comment upon some little defect in domestic life. My literary friend, John, has shamelessly compiled a short phrase-book for our use abroad, reproducing our present regrettable idioms. One inquiry, to be addressed to the local peasant by the leading officer, runs thus:—"Can you tell me, Sir, where the enemy is at present to be found?"—"Où sont les Boches sanguinaires?"[Pg 495]

The other point of view as to going to the Front was put last Sunday with unconscious aptness. At breakfast we had read aloud to us a letter written with inspiring realism by a Watch Dog who is actually there and seeing life in all its detail in the trenches. Having listened to it with rapt attention, we then marched to church and (actually) sang with unanimous fervour:-

"The trivial round, the common task

Will furnish all we need to ask...."

Nevertheless more to be feared than the enraged German is the sceptical scornful Aunt of

Yours ever,

Usher (to Uninvited Guest). "Bride's friends to the right; Bridegroom's to the left."

Uninvited Guest. "I'm afraid I'm a neutral."

"Washington, Saturday.—The American Ambassador at Constantinople reports that Turkey has acquiesced in the departure of several Canadian missionaries, whose safe conduct was requested by Sir Cecil Spring-Rice, the British Ambassador here."

This is headed "Millionaires Released," and shows how well the clergy are paid in Canada.

Panther, tiger, wolf and bear,

They live where the hills are high,

Where the eagle swings in the upper air

And the gay dacoit is nigh;

But we live down in the delta lands,

A decenter place to be—

The frogs and the bats and Little Brother,

The pariah dogs and me.

He was a Rajah once on a time

Who is Little Brother now;

And I know it is all for monstrous crime

Or shamefully broken vow

That he slinks in the dust and eats alone

With a pious tongue and free;

For a holy man is Little Brother,

As beggars ought to be.

But whether he lurks in the morning light

Where the tall plantations grow,

Or wanders the village fields by nights

Telling of ancient woe;

Or whether he's making a sporting run

For me and a dog or two,

An uncanny beast is Little Brother

For Christian eyes to view.

For there comes an hour at the full o' the moon

When the Boh-tree blossoms fall,

And a devil comes out of the afternoon

And has him a night in thrall;

And he hunts till dawn like a questing hound

For souls that have lost their way;

And it's well to be clear of Little Brother

Till the good gods bring the day.

Wherefore I think I will end my song

Wishing him fair good night,

For Little Brother's got something wrong

That'll never on earth come right;

And this perhaps is the honest truth,

And the wisest folk agree,

The less I know about Little Brother

The better by far for me.

Old mother mine, at times I find

Pauses when fighting's done

That make me lonesome and inclined

To think of those I left behind—

And most of all of one.

At home you're knitting woolly things—

They're meant for me for choice;

There's rain outside, the kettle sings

In sobs and frolics till it brings

Whispers that seem a voice.

Cheer up! I'm calling, far away;

And, wireless, you can hear.

Cheer up! you know you'd have me stay

And keep on trying day by day;

We're winning, never fear.

Although to have me back's your prayer—

I'm willing it should be—

You'd never breathe a word to spare

Yourself, and stop me playing fair;

You're braver far than me.

So let your dear face twist a smile

The way it used to do;

And keep on cheery all the while,

Rememb'ring hating's not your style—

Germans have mothers too.

And when the work is through, and when

I'm coming home to find

The one who sent me out, ah! then

I'll make you (bless you) laugh again,

Old sweetheart left behind.

[An inevitable article in any decent magazine at this time of the year. Read it carefully, and then have an uproarious time in your own little house.]

It was a merry party assembled at Happy-Thought Hall for Christmas. The Squire liked company, and the friends whom he had asked down for the festive season had all stayed at Happy-Thought Hall before, and were therefore well acquainted with each other. No wonder, then, that the wit flowed fast and furious, and that the guests all agreed afterwards that they had never spent such a jolly Christmas, and that the best of all possible hosts was Squire Tregarthen!

But first we must introduce some of the Squire's guests to our readers. The Reverend Arthur Manley, a clever young clergyman with a taste for gardening, was talking in one corner to Miss Phipps, a pretty girl of some twenty summers. Captain Bolsover, a smart cavalry officer, together with Professor and Mrs. Smith-Smythe from Oxford, formed a small party in another corner. Handsome Jack Ellison was, as usual, in deep conversation with the beautiful Miss Holden, who, it was agreed among the ladies of the party, was not altogether indifferent to his fine figure and remarkable prospects. There were other guests, but as they chiefly played the part of audience in the events which followed their names will not be of any special interest to our readers. Suffice it to say that they were all intelligent, well-dressed and ready for any sort of fun.

(Now, thank heaven, we can begin.)

A burst of laughter from Captain Bolsover attracted general attention, and everybody turned in his direction.

"By Jove, Professor, that's good," he said, as he slapped his knee; "you must tell the others that."

"It was just a little incident that happened to me to-day as I was coming down here," said the Professor, as he beamed round on the company. "I happened to be rather late for my train, and as I bought my ticket I asked the clerk what time it was. He replied, 'If it takes six seconds for a clock to strike six, how long will it take to strike twelve?' I said twelve seconds, but it seems I was wrong."

The others all said twelve seconds too, but they were all wrong. Can you guess the right answer?

When the laughter had died down, the Reverend Arthur Manley said:

"That reminds me of an amusing experience which occurred to my housekeeper last Friday. She was ordering a little fish for my lunch, and the fishmonger, when asked the price of herrings, replied, 'Three ha'pence for one and a-half,' to which my housekeeper said, 'Then I will have twelve.' How much did she pay?" He smiled happily at the company.

"One-and-sixpence, of course," said Miss Phipps.

"No, no; ninepence," cried the Squire with a hearty laugh.

Captain Bolsover made it come to £1 3s. 2½d., and the Professor thought fourpence. But once again they were all wrong. What do you make it come to?

It was now Captain Bolsover's turn for an amusing puzzle, and the others turned eagerly towards him.

"What was that one about a door?" said the Squire. "You were telling me when we were out shooting yesterday, Bolsover."

Captain Bolsover looked surprised.

"Ah, no, it was young Reggie Worlock," said the Squire with a hearty laugh.

"Oh, do tell us, Squire," said everybody.

"It was just a little riddle, my dear," said the Squire to Miss Phipps, always a favourite of his. "When is a door not a door?"

Miss Phipps said when it was a cucumber; but she was wrong. So were the others. See if you can be more successful.

"Yes, that's very good," said Captain Bolsover; "it reminds me of something which occurred during the Boer War."

Everybody listened eagerly.

"We were just going into action, and I happened to turn round to my men, and say, 'Now, then, boys, give 'em beans!' To my amusement one of them replied smartly, 'How many blue beans make five?' We were all so interested working it out that we never got into action at all."

"But that's easy," said the Professor. "Five."

"Four," said Miss Phipps. (She would. Silly kid.)

"Six," said the Squire.

Which was right?

Jack Ellison had been silent during the laughter and jollity, always such a feature of Happy-Thought Hall at Christmas time, but now he contributed an ingenious puzzle to the amusement of the company.[Pg 497]

"I met a man in a motor-'bus," he said in a quiet voice, "who told me that he had four sons. The eldest son, Abraham, had a dog who used to go and visit the three brothers occasionally. The dog, my informant told me, was very unwilling to go over the same ground twice, and yet being in a hurry wished to take the shortest journey possible. How did he manage it?"

For a little while the company was puzzled. Then, after deep thought, the Professor said:

"It depends on where they lived."

"Yes," said Ellison. "I forgot to say that my acquaintance drew me a map." He produced a paper from his pocket. "Here it is."

The others immediately began to puzzle over the answer, Miss Phipps being unusually foolish, even for her. It was some time before they discovered the correct route. What do you think it is?

"Well," said the Squire, with a hearty laugh, "it's time for bed."

One by one they filed off, saying what a delightful evening they had had. Jack Ellison was particularly emphatic, for the beautiful Miss Holden had promised to be his wife. He, for one, will never forget Christmas at Happy-Thought Hall.

[Note.—The originals of the drawings are on sale from the Author at five guineas apiece.]

Little Tomkins (to Herculean Coalheaver). "Why don't you come up the green a couple o' nights a week an' do a bit o' shootin' an' drillin'? You'd get as fit as a fiddle."

Last winter I wasn't familiar with Brown,

Our intercourse didn't extend

Past a grunt if we met on the journey to town

And a nod when I chose to unbend;

But times are mutata, and now I've begun

To cultivate Brown more and more,

For Brown has a son who is friends with the son

Of a man at the Office of War.

When a fog is concealing how matters progress

And editors wearily use

(Upholding the goodly repute of the Press)

A headline from yesterday's news,

Brown's knowledge enables his friends to decide

What the future is holding in store,

For we gather that Kitchener loves to confide

In that man at the Office of War.

And I in my turn spread the tidings about;

To the heart that is apt to be glum

And the spirit that suffers severely from doubt

Like a sunbeam in winter I come;

"The Teuton," I whisper, "will suffer eclipse

In the course of a fortnight—no more;

I have had it—well, almost direct from the lips

Of the Chief of the Office of War."

German soldiers being roused to enthusiasm by the "Hymn of Hate."

[The rumours of an invasion of this country, which have been prevalent during the last few days, are presumably responsible for these letters addressed to the Kaiser, which have been intercepted.]

Kind Sir,—Should your troops land in this neighbourhood, would you please ask them not to fire off guns between 3 and 4 P.M., as during that hour I have my afternoon rest, and I do not sleep very well.

Yours truly,

Sir,—Hearing that you are thinking of sending over an army, we have formed a small Reception Committee to provide for its comfort, and knowing how concerned you are for the welfare of your troops we think you will be glad to learn that complete arrangements have been made for conveying them to, and accommodating them at, a salubrious spot called Tipperary, immediately on their arrival.

(Signed)

Professor Burgess-Brown, the well-known swimming expert, presents his compliments. He would be pleased to call at Kiel Harbour (or other appointed place) in order to teach the art of natation to German soldiers who may, after arrival in England, suddenly find themselves deprived of their troopships when wishing to return.

Dear Sir,—We hear that a number of your friends are coming to England, and shall accordingly welcome an enquiry for our advice, which is always at the disposal of the travelling public. We do not know whether you propose personally to come over, but we should certainly recommend this course, as by travelling viá an English port you could get a boat direct to St. Helena and thus save the wearisome changing to which you might be exposed in sailing from the Continent.

Yours obediently,

Dear Sir,—I don't think there is much use in your troops landing. In this county alone there are two hundred and ninety-five more scouts than there were in August, and they are still coming in. Of course come if you like, but don't say I didn't warn you.

Yours,

Sir,—Hearing that your troops are thinking of visiting the above town, we should be glad to take you, in small or large groups. We understand that your excursion will be only a half-day one, but we have facilities for the immediate development of negatives.

Yours obediently,

Send your men over if you like. Let them turn their guns on all our ancient buildings, destroy crops, blow up bridges; but MIND, if one of your Huns raises a rifle to any Norfolk or Suffolk fox, there will be trouble of a serious kind.

Old Lady (to District Visitor). "Did you hear a strange noise this morning, Miss, at about four o'clock? I thought it was one of them aireoplanes; and my neighbour was so sure it was one he went down and let his dog loose."

The year that is stormily ending

Has brought us full measure of grief,

And yet we must thank it for sending

At times unexpected relief;

These boons are not felt in the trenches

Or make our home burdens less hard;

They're not a bonanza, but merit a stanza

Or two from the doggerel bard.

The names of musicians and mummers

No longer are loud on our lips;

By the side of our buglers and drummers

Caruso endures an eclipse;

And the legions of freaks and of faddists

Who hailed him with rapturous awe,

O wonder of wonders, are finding out blunders,

And worse, in the writings of SHAW!

Good Begbie, no longer upraising

His plea for the "uplift" of Hodge,

Has ceased for a season from praising

Lloyd George and Sir Oliver Lodge;

And there hasn't been much in the papers

About the next novel from Caine

(No doubt he's in Flanders, the guest of commanders

Who reverence infinite brain).

John Ward has forgiven the Curragh

(The Curragh's forgotten John Ward);

No longer he cries "Wurra Wurra!"

At sight of an officer's sword;

MacDonald, the terror of tigers,

Sits silent and meek as a mouse,

And the great von Keirhardi is curiously tardy

In "voicing" his spleen in the House.

The screeds of professors and jurists

Have quite disappeared from the Press;

'Tis little we hear of Futurists,

And frankly we care even less;

Why, Trevelyan, the martyr to candour,

Who lately his office resigned,

Though waters were heaving has sunk without leaving

The tiniest ripple behind.

In fine, though there fall to our fighters

Too many hard buffets and humps,

'Tis a comfort to think that our blighters

Are down in the deadliest dumps;

And whatever the future may bring us

In profits or pleasures or pains

The ill wind that's blowing to-day is bestowing

A number of negative gains.

"Are we sending Christmas cards this year? Yes," said Blathers, "but not next year, or the year after that, as we shall be retrenching. They are quite modest trifles, yet at the mere sight of the envelope each recipient will, cheerfully, I hope, pay twopence towards the sinews of war. One hundred of these contributions will amount, I am told, to sixteen shillings and eightpence; not much, but it is my little offering to the country in her hour of need. This is the card I propose to send out in a sealed and unstamped cover":—

Mr. and Mrs. Blathers wish you A Happy Christmas 1914, 1915 and 1916, and A Bright New Year 1915, 1916 and 1917.

"The Russian mining engineers who have been sent to Galicia since the occupation report that the oil districts will suffice to supply the whole of South-Western Russia. The working of the fields will start in the spring; moreover salt and iron abound, also sporadicalli, silver, copper, lead and the rarer metals."

For vermicelli, however, it will still be necessary to go to Italy.

To the list of things that the Belgians in Crashie Howe do not understand, along with oatmeal, honey in the comb, and tapioca, must now be added the Scottish climate. They do not complain, but they are puzzled, and after sixty-five consecutive hours of rain they wonder wistfully if it is always like this. We simply dare not tell them the truth.

By every post we are busy hunting for lost relatives who are scattered before the shattering fist of the Kaiser over Great Britain, Belgium, Holland and France. We have not been very successful so far, but one or two we have found, at points as far apart as York and Milford Haven, and, best of all, we have unearthed a great-grandmother, last seen in an open coal boat off Ostend, who is now in comfortable quarters in a village in Ayrshire.

Our language difficulties have not been assisted by the arrival of a family from Antwerp who talk nothing but Walloon, but, on the other hand, the progress of the children is now beginning to afford certain frail lines of communication. The least of them, Élise, can already count up to twenty in English (with a strong Scoto-Flemish accent), and so it came about that when I took my little nieces round to pay calls, relations were at once established on a numerical basis.

"One, two, three," said Sheila, holding out her hand.

"Four," retorted Juliette, gurgling with delight.

"Five, six, seven," shouted Betty.

"Eight, nine?" enquired Juliette....

At the next cottage, where we were all rather shy, we began tentatively with "One?" But we finally gained so much confidence that by the time we reached our last visit we ran it up to ten at a single burst, and were consequently received with open arms.

One of our main concerns has been the Santa Claus question, and that is a matter which touches us closely, as we have among our number eleven children of Santa Claus age. There are a good many pitfalls here, and it is now unfortunately too late to warn other people of the chief of them. For the fact is—as we found to our amazement—that Santa Claus (you must, by the way, call him St. Nicholas; after all, it is his proper name) comes to Belgium and Russia, not on December 25th, but on December 6th. All our attempts to explain this phenomenon by the difference in the Russian calendar, though ingenious, have failed; it doesn't work out at all. Still, for some reason, that is how it is, and we cannot but be grateful to St. Nicholas for this delicate attention to our allies, by which no doubt they get the pick of the toys, even though we were nearly let in by him. Indeed Pierre had practically given up hope. He had told his mother that he was afraid St. Nicholas would never find his way to Scotland, it was too far.

Then there is another thing which might easily have been overlooked. It's no use putting out stockings, as we prefer to do in our insular way; one must put out shoes. At first sight it looks as if we in this country have the pull over our allies here, for one pair of little shoes does not hold much stuff. But fortunately it is the happy custom in all lands to allow of overflow to any extent. And finally St. Nicholas never comes down the chimney; he pops in through the window (which should be left slightly open at the bottom so that he can get in his thumb and prize it up). Also he never drove a reindeer in his life. He rides a horse. And this is of the first importance, for the one condition attaching to his benevolence is that you must put out a good wisp of hay for the horse, along with your shoes, or else he will simply pass on and you will get nothing at all.

Having collected and considered all these facts we were fully prepared to meet the situation—even down to the small gingerbread animals which always grace the day—on December 6th, and to deal faithfully with the little rows of clogs, bulging with hay, which awaited us on St. Nicholas Eve.

Weary Variety Agent. "And what's your particular claim to originality?"

Artiste. "I'm the only Comedian who has so far refrained from addressing the orchestra as 'you in the trench.'"

"It's perfectly simple," said the Reverend Henry, adopting his lofty style. "We must cut the whole lot. There is no other course."

"I don't consider that your opinion is of any value whatever," said Eileen. "In fact you ought not to be allowed to take part in this discussion. Every one knows that you have always tried to get out of Christmas presents, and now you are merely using a grave national emergency to further your private ends."

The Reverend Henry was squashed; but Mrs. Sidney had a perfect right to speak, for she has been without doubt the most persistent and painstaking Christmas provider in the family, and has never been known to miss a single relation even at the longest range.

"I quite agree with Henry," said she. "This is no time for Christmas presents—except to hospitals and Belgians and men at the Front."

"You mean that you would scratch the whole lot," said I, "even the pocket diary for 1915 that I send to Uncle William?"

"Yes, even that. You can send the diary to Sidney" (who is in Flanders). "I have always wanted him to keep a diary."

"What about the children?" said I.

"The children must realise," said the Reverend Henry solemnly, "what it means for the nation to be at war."

"Oh, no," Laura broke in impetuously. "How can they realise? How can you expect Kathleen to realise?"

"Do you know," said the Reverend Henry, "that only last Sunday my niece Kathleen was marching all over the house singing at the top of her voice, 'It's a long, long way to Tipperary: the Bible tells me so'? Obviously she realises."

"But what about——" Eileen was beginning.[Pg 503]

"Let's have a scrap of paper," said I, "a contract that we can all sign, and then we can put down the exceptions to the rule."

Henry was already hard at work with a sheet of foolscap.

" ... not to exchange, give, receive or swap in celebration of Christmas, 1914, any gift, donation, subscription, contribution, grant, token or emblem within the family and its connections: and further not to permit any gift, donation, subscription, contribution, grant, token or emblem to emanate from any member of the family to such as are outside."

"Good so far," said I.

"The following recipients to be excepted," Henry went on,

"(1) All Hospitals; (2) Belgians; (3) His Majesty's Forces——"

"(4) The Poor and Needy," suggested Eileen.

"(5) The Aged and Infirm," said I. "I only want to get in Great-aunt Amelia. She mustn't be allowed to draw a blank."

"That's true," said Henry; "we'll fix the age limit at ninety-one. That'll bring her in."

"(6) Children of such tender age that they are unable to realise the national emergency," said Mrs. Sidney.

"Quite so," said Henry. "What would you suggest as the age limit? Three?"

"Four," said Laura simultaneously.

"I should like to suggest five," said I, "to bring in Kathleen."

"Let's make it seven," said Mrs. Henry. "I can hardly believe that Peter realises, you know."

"Stop a bit," said I. "If you take in Peter you can't possibly leave out Tom. Make it eight-and-a-half."

"That seems a little hard on Alice, doesn't it?" said Eileen.

"Any advance on eight-and-a-half?" called Henry from the writing-desk. And from that moment the discussion assumed the character of an auction, Laura finally running it up to thirteen (which brings in the twins) to the general satisfaction.

When the contract was signed, witnessed and posted on its way to the other signatories there was a general sense of relief that Christmas would not be very different from usual after all. Henry growled a good deal. But we know our Reverend Henry: he will do his duty when the time comes.

"The Prince of Wales noticed a private in his own regiment, the Grenadier Guards, who is six feet inches in height. He is six feet inches in height."—Scotsman.

It sounds silly, but the writer evidently means it.

Voice from below. "For 'eaven's sake, mum, get back. The fire-escape will be 'ere in five minutes."

Endangered Female. "Five minutes? Then throw me back my knitting."

A Philistine? Then you will smile

At this old willow-pattern plate

And junks of long-forgotten date

That anchor off Pagoda Isle;

At little pig-tailed simpering rakes

Who kiss their hands (three miles away)

To dainty beauties of Cathay

Beside those un-foreshortened lakes.

With hand on heart they smile and sue.

Their topsy-turvy world, you say,

Is out of all perspective? Nay,

'Tis we who look at life askew.

Dreams lose their spell; hard facts we prize

In our humdrum philosophy;

But, could we change, who would not be

A suitor for those azure eyes?

Who would not sail with fairy freight

Piloting some flat-bottomed barge—

A size too small, or else too large—

On this old willow-pattern plate?

"The 'Figaro' publishes a telegram from Petrograd which contradicts the German announcement that Lodz is occupied by the Kermans."—Lancashire Evening Post.

And quite right too.

There was a battlefield, I was told, with a ruined village near it, about as far from Paris as Sevenoaks is from London, and I decided to see it. The preliminaries, they said, would be difficult, but only patience was needed—patience and one's papers all in order. It would be necessary to go to the War Bureau, opposite the Invalides.

I went to the War Bureau opposite the Invalides one afternoon. I rang the bell and a smiling French soldier opened the door. Within were long passages and other smiling French soldiers in little knots guarding the approaches, all very bureaucratic. The head of the first knot referred me to the second knot; the head of the second referred me to a third. The head of this knot, which guarded the approach to the particular military mandarin whom I needed or thought I needed, smiled more than any of them, and, having heard my story, said that that was certainly the place to obtain leave. But it was unwise and even impossible to go by any other way than road, as the railway was needed for soldiers and munitions of war, and therefore I must bring my chauffeur with me, with his papers, which must be examined and passed.

My chauffeur? I possessed no such thing. Necessary then to provide myself with a chauffeur at once. Out I went in a fusillade of courtesies and sought a chauffeur. I visited a taxi rank and stopped this man and that, but all shied at the distance. At last one said that his garage would provide me with a car. So off to the garage we went, and there I had an interview with a manager, who declined to believe that permission for the expedition would be made at all, except possibly to oblige a person of great importance. Was I a person of great importance? he asked me. Was I? I wondered. No, I thought not. Very well then, he considered it best to drop the project.

I came away and hailed another taxi, driven by a shaggy grey hearthrug. I told him my difficulties, and he at once offered to drive me anywhere and made no bones about the distance whatever. So it was arranged that he should come for me on the morrow—say Tuesday, at a quarter to eleven, and we would then get through the preliminaries and my lunch comfortably by noon and be off and away. So do hearthrugs talk with foreigners—light-heartedly and confident. But Heaven disposes. For when we reached the Bureau at a minute after eleven the next morning the smiling janitor told us we were too late. Too late at eleven? Yes, the office in question was closed between eleven and two; we must return at two.

"But the day will be over," I said; "the light will have gone. Another day lost!" Nothing on earth can crystallize and solidify so swiftly and implacably as the French official face. At these words his smile vanished. He was not angry or threatening—merely granite. Those were the rules, and how could anyone question them? At two, he repeated: and again I left the building, this time not bowing quite so effusively, but suppressing a thousand criticisms which might have been spoken were not the French our allies.

Three hours to kill in a city where everything is shut. No Louvre, no Carnavalet! However, the time went, chiefly over lunch, and at two we were there again, the hearthrug and I, and were shown into a waiting-room where far too many other persons had already assembled. To me this congestion seemed deplorable; but the hearthrug merely grinned. It was all a new experience to him, and his meter was registering the time. We waited, I suppose, forty minutes and then came our turn, and we were led to a little room where sat a typical elderly French officer at a table. He had white moustaches and was in uniform with blue and red about it. I bowed, he bowed, the hearthrug grovelled. I explained my need, and he replied instantly that I had come to the wrong place; the right place was the Conciergerie.

Another rebuff! In England I might have told him that it was one of his own idiotic men who had told me otherwise, but of what use would that be in France? In France a thing is or is not, and there is no getting round it if it is not. French officials are portcullises, and they drop as suddenly and as effectively. Knowing this, so far from showing resentment or irritation, I bowed and made my thanks as though I had come for no other purpose than a dose of frustration; and again we left this cursed Bureau.

I re-entered the taxi, which, judging by the meter, I should very soon have completely paid for, and we hurtled away (for the hearthrug was a demon driver) to Paris's Scotland Yard. Here were more passages, more little rooms, more inflexible officials. I had bowed to half-a-dozen and explained my errand before at last the right one was reached, and him the hearthrug grovelled to again and called "Mon Colonel." He sat at a table in a little room, and beside him, all on the same side of the table, sat three civilians. On the wall behind was a map of France. What they did all day, I wondered, and how much they were paid for it; for we were the only clients, and the suggestion of the place was one of anecdotage and persiflage rather than toil. They acted with the utmost unanimity. First "Mon Colonel" scrutinised my passport, and then the others, in turn, scrutinised it. What did I want to go to —— for? (The name is suppressed because it is two or three months since the battle was fought there.) I replied that my motive was pure curiosity. Did I know it was a very dull town? I wanted to see the battlefield. That would be triste too. Yes, I knew, but I was interested. "Mon Colonel" shrugged and wrote on a piece of paper and passed the paper to the first civilian, who wrote something else and passed it on, and finally the last one got it and discovered a mistake in the second civilian's writing, and the mistake had to be initialled by all the lot, each making great play with a blotter; and at last the precious document was handed to me and I was really free to start. But it was now dark.

The road from —— leaves the town by a hill, crosses a canal, and then mounts and winds, and mounts again, and dips and mounts, between fields of stubble, with circular straw-stacks as their only occupants. The first intimation of anything untoward, besides the want of life, was the spire of the little white village of —— on the distant hill, which surely had been damaged. As one drew nearer it was clear that not only had the spire been damaged, but that the houses had been damaged too. The place seemed empty and under a ban.

I stopped the car outside, at the remains of a burned shed, and walked along the desolate main street. All the windows were broken; the walls were indented with little holes or perforated with big ones. The roofs were in ruins. Here was the post-office; it is now half demolished and boarded up. There was the inn; it is now empty and forlorn. Half the great clock face leant against a wall. Everyone had fled—it is a "deserted village" with a vengeance: nothing left but a few fowls. Everything was damaged; but the church had suffered most. Half of the shingled spire was destroyed, most of the roof, and the great bronze bell lay among the débris on the ground. It is as though the enemy's policy was to intimidate the simple folk through the failure of their super-natural stronghold. "If the church is so pregnable, then what chance have we?"—that is the question which it was hoped would be asked; or so I imagined as I stood before this ruined[Pg 505] sanctuary. Where, I wondered, are those villagers now, and what chances are there of the rebuilding of these old peaceful homes, so secure and placid only four months ago?

And then I walked to the battlefield a few hundred yards away, and only too distinguishable as such by the little cheap tricolors on the hastily-dug graves among the stubble and the ricks. Hitherto I had always associated these ricks with the art of Claude Monet, and seeing the one had recalled the other; but henceforward I shall think of those poor pathetic graves sprinkled among them, at all kinds of odd angles to each other—for evidently the holes were dug parallel with the bodies beside them—each with a little wooden cross hastily tacked together, and on some the remnants of the soldier's coat or cap, or even boots, and on some the blue, white and red. As far as one can distinguish, these little crosses break the view: some against the sky-line, for it is hilly about here, others against the dark soil.

It was a day of lucid November sunshine. The sky was blue and the air mild. A heavy dew lay on the earth. Not a sound could be heard; not a leaf fluttered. No sign of life. We were alone, save for the stubble and the ricks and the wooden crosses and the little flags. How near the dead seemed: nearer than in any cemetery.

Suddenly a distant booming sounded; then another and another. It was the guns at either Soissons or Rheims—the first thunder of man's hatred of man I had ever heard.

So I, too, non-combatant, as Anno-Domini forces me to be, know something of war—a very little, it is true, but enough to make a difference when I read the letters from the trenches or meet a Belgian village refugee.

Pompous Lady. "I shall descend at Knightsbridge."

Tommy (aside). "Takes 'erself for a bloomin' Zeppelin!"

"General Joffre then engaged in a short conversation with several journalists, and when they referred to the military medal which M. Poincaré pinned on his chest, he said: '3/8 All this counts for nothing.'"

But on the other 5/8 we offer our respectful congratulations.

I have a friend, a gloomy soul,

Who daily wails about the war,

Taking the line that, on the whole,

Our luck is rotten at the core,

And into each success

Reads some disaster, rather more than less.

Another friend I have, whose heart

Beats with "abashless" confidence,

Who sees the Kaiser in the cart

And hung in chains "a fortnight hence";

He saw this months ago,

And some day hopes to say, "I told you so."

When Heraclitus brings a cloud,

Democritus provides the sun;

Or should the Hopeful crow too loud,

I listen to the Mournful One;

And thus, between the two,

I find a fairly rational point of view.

"Once or twice he sighed a little, although he had an uninterrupted view of a profile as regular as a canoe."—New Magazine.

No, he was not a shirker, as you thought. Nor was he engaged in making munitions of war, or khaki, or woollens, or military boots, or in exporting cocoa to the enemy viâ neutral Holland—that roaring monopoly of the Pacificist. His business was to spy at spies—a task that called for as much coolness and courage as any job at the Front. And so when the officious flapper presented him with a white feather he had no use for it except as a pipe-cleaner.

For his purpose Christopher Brent had taken up his residence at a "select boarding establishment" on the East Coast, which contained the following members of the German Secret Service: Mrs. Sanderson, proprietress; Carl, her son, clerk in the British Admiralty; Fräulein Schroeder, boarder, and Fritz, waiter. Their design, if I rightly penetrated its darkness, was to give information of the whereabouts of a certain section of the Expeditionary Force which was "coming through from the North"; to supply Berlin with plans of the coast defences; and finally to give a signal to a German submarine by the firing of the house, which would incidentally mean the roasting alive of its innocent contents. All this (for the sake of Aristotle and the Unities) was to take place in a single day, though I for one could not believe that either the pigeon post or the ordinary mail would be equal to the strain.

Their utensils included a Marconi instrument concealed in the chimney; a bomb; a revolver; maps of the minefield and harbour; a carrier-pigeon, and a knife for disposing of the cliff-sentry.

"Hands up!"

"Hands up yourself!"

Carl Sanderson. .. Mr. Malcolm Cherry.

Christopher Brent. .. Mr. Dennis Eadie.

To frustrate their schemes something more was needed than the wit of Brent and his ally, the widow Leigh; something more, even, than his skill in shooting pigeons in flight with an air-rifle. The vacuum was supplied by the crass stupidity of the Emperor's minions. Even when full credit is given to Brent for letting his bath overflow so as to flood the public salon and render it untenable, it was surely unwise of Mrs. Sanderson to offer her private parlour for the use of the boarders on the very day set apart for the execution of her plans which were centred in this room. It was also gross carelessness on the part of her son, when he had Brent, with hands up, at his mercy, to place his own revolver on the table and to use, in exchange, the unloaded weapon which he had taken from his opponent's pocket. It was puerile, too, to accept without proof the verbal assurances of the widow Leigh that she was one of themselves, a loyal German spy. And Fritz committed an unpardonable error in giving away the site of the Marconi apparatus by his undisguised suspicion of anybody who took any interest in the fireplace.

And so their schemes all went agley; the whole pack was arrested; and when the curtain fell on a happy group of boarders in midnight déshabille there was every promise that the misdemeanants would receive a month's imprisonment or at least a caution to be of good behaviour for the future.

I understand, on good authority, that the tendency of the public at this juncture of the War is to demand light refreshment. Well, they have it here. For, though the subject deals with a serious problem of the hour, it can be treated, and is treated, with a very permissible humour that just stops short of farce. Some of the stage-devices, as I am assured by my betters, may have a touch of antiquity, but their application is as modern as can well be, and I should indeed be ungrateful if after an entertainment so smoothly and dexterously administered I were to be captious about origins or other matters of pedantry.

Mr. Dennis Eadie, as Brent, both in his real character of detective and in the assumed futility of his disguise as a genial idiot, was equally excellent, and again proved his gift for quick-change artistry. Miss Mary Jerrold's Fräulein Schroeder was extraordinarily Teutonic in all but her quiet humour, which she seemed to have caught from the country of her adoption. The Fritz of Mr. Henry Edwards was another delightful sketch, though his actual German birth and his allegation of Dutch nationality were both belied by the red Italian corpuscles with which the authors had inoculated him. Miss Jean Cadell, as usual, played a pale and fatuous spinster, but this time, in the part of Miss Myrtle, she had her chance, and seized it bravely. When that typical British boarder, Mr. John Preston, M.P.. (interpreted with great relish and vigour by Mr. Hubert Harben), remarked, "I call a spade a spade," she replied, "And I suppose you would call a dinner-napkin a serviette"—one of the pleasantest remarks in a play where the good things said were many and unforced.

I have not mentioned the admirable performance—its merits might easily be missed—of Mr. Stanley Logan as a Territorial Tommy; or the very natural manners of Mrs. Robert Brough as Mrs. Sanderson; or the quiet art of Miss Ruth Mackay in a part (Miriam Leigh) that offered a too-limited scope to her exceptional talents. Miss Isobel Elsom contributed her share of the rather perfunctory love-interest with a very pretty sincerity; and Mr. Malcolm Cherry, in the ungrateful part of the spy Carl, did his work soundly, with a lofty sacrifice of his own obvious good-nature. Indeed, it was a very excellent cast.

I should like to congratulate the authors, Messrs. Lechmere Worrall, and Harold Terry, on having given the public what they want, without lapsing into banality. The attraction of the first two Acts was not, perhaps, fully sustained in the third, but they gave us quite a cheerful evening; and at the fall of the curtain the audience was so importunate in their applause that Mr. Dennis Eadie had to break it to them that, though the loss of their company would give him pain, he thought the time had come for them to go away.

I did not notice Mr. Reginald McKenna in the stalls, but it was a great night for him and the Home Office.

Says the sleek humanitarian: "Any sacrifice I'd make

For the voluntary system—up to going to the stake,"

Which inspires the obvious comment that contingencies like this

Turn the coming of conscription to unmitigated bliss.

"The remaining characters were taken by Mr. Herbert Lomas as Ever, a splendid actor...."—Manchester City News.

You should see Sir Herbert Tree as Always.

If The Prussian Officer, a study of morbidly vicious cruelty practised by a captain of Cavalry on his helpless orderly (and the first of a sheaf of collected stories, short or shortish, by Mr. D. H. Lawrence, issued by Messrs. Duckworth), had been written since the declaration of war it would certainly be discounted as a product of the prevailing odium bellicosum. But it appeared well in the piping times of peace, and I remember it (as I remember others of the collection) with a freshness which only attaches to work that lifts itself out of the common ruck. An almost too poignant intensity of realism, expressed in a distinguished and fastidious idiom, characterises Mr. Lawrence's method. It is a realism not of minutely recorded outward happenings, trivial or exciting, but of fiercely contested agonies of the spirit. None of those stories is a story in the accepted mode. They are studies in (dare one use the overworked word?) psychological portraiture. I don't know any other writer who realises passion and suffering with such objective force. The word "suffering" drops from his pen in curiously unexpected contexts. The fact of it seems to obsess him. Yet it is no morbid obsession. He seems to be dominated by sympathy in its literal meaning, and it gives his work a surprising richness of texture.... I dare press this book upon all such as need something more than mere yarns, who have an eye for admirably sincere workmanship and are interested in their fellows—fellows of all sorts, soldiers, keepers, travellers, clergymen, colliers, with womenfolk to match.

On a map of the North you may be able to find an island named after one Margaret. It should lie, though I have sought it in vain, just about where the florid details of the Norwegian coast-line run up to those blank spaces that are dotted over, it would seem, only by the occasional footprints of polar bears. Anyhow it was so christened by two bold mariners who lived in the Spacious Days (Murray) of Queen Elizabeth. That they both loved the lady (Elizabeth, of course, too—but I mean Margaret) may be assumed; but that they should eventually, with one accord, desire to resign their claims upon her affection must be read to be understood. I for one did not quarrel with them on this score. For had not their mistress in the meantime found companionship more suitable than theirs? Besides, if even the author is so little courteous to his heroine as to invite her to appear only in two chapters between the third and the twenty-seventh, why should two rough sea-dogs—or you and I—be more attentive? And indeed it is a correct picture of his period that Mr. Ralph Durand is concerned to present rather than a love story. In the writing of the love scenes considered necessary to the mechanism of the plot he seems very little at his ease; and so marked at times is his discomfort that I must confess to having felt some irritation when my willingness to be convinced was not met halfway. In the handling of his sheets and oars I like the author better, though even here I miss what might have brought me into a companionship with his people as close as I could wish on a most adventurous journey of nearly four hundred pages. But perhaps that is my fault; and, at the least, here is a straightforward sea story—as honest as the sea and as clean.

Llanyglo was a child with fair hair and blue eyes, and how she grew and what she learnt, and all the changes of her dresses and her soul, are set forth by Mr. Oliver Onions in Mushroom Town (Hodder and Stoughton). She differed from the children of other novelists who grow up to be men and women, because she was made of bricks and mortar and iron girders and romantic scenery and ozone (especially ozone), and the people who lived with her or took trips to see her are treated as a mere emblematical garnish of her character and growth. Llanyglo is a daughter of Wales, but she is not any town that you may happen to have seen, although possibly Blackpool and Douglas and Llandudno have met her, and turned up their noses at her, as she turned up her nose at them. Lancashire built and conquered her, to be conquered and annually recuperated in turn. Cymria capta ferum ... might have been the motto of her municipal arms. Exactly how Mr. Onions exhibits the romantic spectacle of her development, with the strange knowledge she picked up, as from virgin wildness she became first select and then popular, I cannot hope to explain. Suffice it to say that the process is epitomised in sketches of the various people who helped in the moulding of her—the drunken Kerr brothers, who built a house in a single night; Howell Gruffydd, the wily grocer; Dafydd Dafis, the harper; and John Willie Garden, son of the shrewd cotton-spinner who first saw the possibilities of the place, and won the heart of the untamed gipsy girl, Ynys. This is surely Mr. Onions' best novel since Good Boy Seldom; and as Llanyglo is safely ensconced on the West coast you should go there at once for the winter season.

Spragge's Canyon (Smith, Elder), takes its title, as you might guess, from the canyon where the Spragges lived. It was a delightful spot, a kind of earthly paradise (snakes included), and the Spragge family had made it all themselves out of unclaimed land on the Californian coast. Wherefore the Spragges loved it with a love only equalled perhaps by the same emotion in the breast of Mr. H. A. Vachell, who has written a book about it. The Spragges of the tale are Mrs. Spragge, widow of the pioneer, and her son George. With them on the ranch lived also a cousin, Samantha, a big-built capable young woman, destined by Providence and Mrs. Spragge to be the helpmate of George. But George, though he was strong and handsome and a perfect marvel with rattlesnakes (which he collected as a subsidiary source of income), was also a bit of a fool; and when, on one of his rare townward excursions, he got talking to Hazel Goodrich in a street car, her pale attractiveness and general lure proved too much for him. Accordingly Hazel was asked down to the ranch on a visit (I am taking it on trust that Mr. Vachell knows the Californian etiquette in these matters) and has the time of her life, flirting with the love-lorn George, impressing his mother, and generally scoring off poor Samantha. At least so she thought. Really, however, Mrs. Spragge had taken Hazel's measure in one, and was all the time quietly fighting her visitor for her son's future. This fight, and the character of the mother who makes it, are the best things in the book. I shall not tell you who wins. Personally I had expected a comedy climax, and was unprepared for creeps. But George, I may remind you, collected snakes. A good and virile tale.

Sir Melville Macnaghten hopes, in his Introduction to Days of my Years (Arnold), that his reminiscences "may be found of some interest to a patient reader"; and, when one considers that Sir Melville spent twenty-four years at Scotland Yard, many of them as chief of the Criminal Investigation Department, he can hardly be accused of undue optimism. Speaking as one of his readers, I found no difficulty at all in being patient. I have always had a weakness for official detectives, and have resented the term "Scotland Yard bungler" almost as if it were a personal affront; and now I feel that my resentment is justified. Scotland Yard does not bungle; and the advice I shall give for the future to any eager-eyed, enthusiastic young murderer burning to embark on his professional career is, don't practise in London. I would not lightly steal a penny toy in the Metropolitan area. There are two hundred and seventy-nine pages in this story of crime, as seen by the man at the very centre of things, and nearly every one of them is packed with matter of absorbing interest. Consider the titles of the chapters: "Bombs and their Makers"; "Motiveless Murders"; "Half-a-day with the Blood-hounds." This, I submit, is the stuff; this, I contend, is the sort of thing you were looking for. There is something so human and simple in Sir Melville's method of narration that it is with an effort that one realises what an important person he really was, and what extraordinary ability he must have had to win and hold his high position. Even when he disparages blood-hounds I reluctantly submit to his superior knowledge and abandon one of my most cherished illusions. I hate to do it, but if he says that a blood-hound is no more use in tracking criminals than a Shetland pony would be, I must try to believe him.

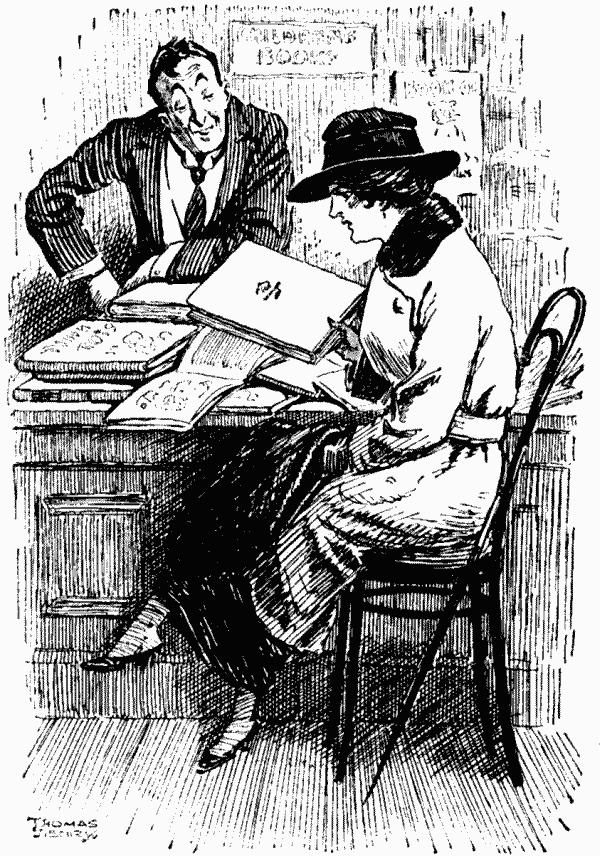

Lady (rather difficult to please). "I like this one, but—I see it's printed in Germany."

Salesman. "Well, if you like it, Madam, I wouldn't take too much notice of that statement. It's probably only another German lie!"

"After Herr Von Holman Bethwig's wild speech in the German Reichstag the Government might change their minds."

It isn't much one can do to the German Chancellor just now, but these misprints of his name always annoy him, and every little helps.