Title: Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

Author: Various

Editor: Harry Bates

Release date: August 23, 2009 [eBook #29768]

Most recently updated: August 28, 2013

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

W. M. CLAYTON, Publisher HARRY BATES, Editor DR. DOUGLAS M. DOLD, Consulting Editor

That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid, by leading writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the Authors' League of America;

That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS MONTHLY, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE, and WESTERN ADVENTURES.

More than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

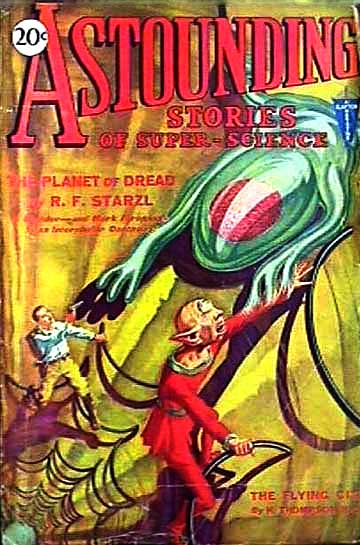

| COVER DESIGN | H. W. WESSOLOWSKI | ||

| Painted in Water-colors from a Scene in "The Planet of Dread." | |||

| THE PLANET OF DREAD | R. F. STARZL | 147 | |

| A Stupid Blunder—and Mark Forepaugh Faces a Lifetime of Castaway Loneliness in the Savage Welter of the Planet Inra's Monster-ridden Jungles. | |||

| THE LORD OF SPACE | VICTOR ROUSSEAU | 158 | |

| A Black Caesar Had Arisen on Eros—and All Earth Trembled at His Distant Menace. | |||

| THE SECOND SATELLITE | EDMOND HAMILTON | 175 | |

| Earth-men War on Frog-vampires for the Emancipation of the Human Cows of Earth's Second Satellite. (A Novelet.) | |||

| SILVER DOME | HARL VINCENT | 192 | |

| In Her Deep-buried Kingdom of Theros, Phaestra Reveals the Amazing Secret of the Silver Dome. | |||

| EARTH, THE MARAUDER | ARTHUR J. BURKS | 210 | |

| Deep in the Gnome-infested Tunnels of the Moon, Sarka and Jaska Are Brought to Luar the Radiant Goddess Against Whose Minions the Marauding Earth Had Struck in Vain. (Part Two of a Three-Part Novel.) | |||

| MURDER MADNESS | MURRAY LEINSTER | 237 | |

| Bell Has Fought through Tremendous Obstacles to Find and Kill The Master, Whose Diabolical Poison Makes Murder-mad Snakes of the Hands; and, as He Faces the Monster at Last—His Own Hands Start to Writhe! (Conclusion.) | |||

| THE FLYING CITY | H. THOMPSON RICH | 260 | |

| From Space Came Cor's Disc-city of Vada—Its Mighty, Age-old Engines Weakening— Its Horde of Dwarfs Hungry for the Earth! | |||

| THE READERS' CORNER | ALL OF US | 279 | |

| A Meeting Place for Readers of Astounding Stories. | |||

Single Copies, 20 Cents (In Canada, 25 Cents) Yearly Subscription, $2.00

Issued monthly by Publishers' Fiscal Corporation, 80 Lafayette St., New York, N. Y. W. M. Clayton, President; Nathan Goldmann, Secretary. Entered as second-class matter December 7, 1929, at the Post Office at New York, N. Y., under Act of March 3, 1879. Title registered as a Trade Mark in the U. S. Patent Office. Member Newsstand Group—Men's List. For advertising rates address E. R. Crowe & Co., Inc., 25 Vanderbilt Ave., New York; or 225 North Michigan Ave., Chicago.

This time Forepaugh was ready for it.

This time Forepaugh was ready for it.

here was no use hiding from the truth. Somebody had blundered—a fatal blunder—and they were going to pay for it! Mark Forepaugh kicked the pile of hydrogen cylinders. Only a moment ago he had broken the seals—the mendacious seals that certified to the world that the flasks were fully charged. And the flasks were empty! The supply of this precious power gas, which in an emergency should have been sufficient for six years, simply did not exist.

He walked over to the integrating machine, which as early as the year 2031 had begun to replace the older atomic processes, due to the shortage of the radium series metals. It was bulky and heavy compared to the atomic disintegrators, but it was much more economical and very dependable. Dependable—provided some thick-headed stock clerk at a terrestrial supply station did not check in empty hydrogen cylinders instead of full ones. Forepaugh's unwonted curses brought a smile to the stupid, good-natured face of his servant, Gunga—he who had been banished for life from his native Mars for his impiety in closing his single round eye during the sacred Ceremony of the Wells.

The Earth man was at this steaming hot, unhealthful trading station under[148] the very shadow of the South Pole of the minor planet Inra for an entirely different reason. One of the most popular of his set on the Earth, an athletic hero, he had fallen in love, and the devoutly wished-for marriage was only prevented by lack of funds. The opportunity to take charge of this richly paid, though dangerous, outpost of civilization had been no sooner offered than taken. In another week or two the relief ship was due to take him and his valuable collection of exotic Inranian orchids back to the Earth, back to a fat bonus, Constance, and an assured future.

It was a different young man who now stood tragically before the useless power plant. His slim body was bowed, and his clean features were drawn. Grimly he raked the cooling dust that had been forced in the integrating chamber by the electronic rearrangement of the original hydrogen atoms—finely powdered iron and silicon—the "ashes" of the last tank of hydrogen.

unga chuckled.

"What's the matter?" Forepaugh barked. "Going crazy already?"

"Me, haw! Me, haw! Me thinkin'," Gunga rumbled. "Haw! We got, haw! plenty hydr'gen." He pointed to the low metal roof of the trading station. Though it was well insulated against sound, the place continually vibrated to the low murmur of the Inranian rains that fell interminably through the perpetual polar day. It was a rain such as is never seen on Earth, even in the tropics. It came in drops as large as a man's fist. It came in streams. It came in large, shattering masses that broke before they fell and filled the air with spray. There was little wind, but the steady green downpour of water and the brilliant continuous flashing of lightning shamed the dull soggy twilight produced by the large, hot, but hidden sun.

"Your idea of a joke!" Forepaugh growled in disgust. He understood what Gunga's grim pleasantry referred to. There was indeed an incalculable quantity of hydrogen at hand. If some means could be found to separate the hydrogen atoms from the oxygen in the world of water around them they would not lack for fuel. He thought of electrolysis, and relaxed with a sigh. There was no power. The generators were dead, the air drier and cooler had ceased its rhythmic pulsing nearly an hour ago. Their lights were gone, and the automatic radio utterly useless.

"This is what comes of putting all your eggs in one basket," he thought, and let his mind dwell vindictively on the engineers who had designed the equipment on which his life depended.

An exclamation from Gunga startled him. The Martian was pointing to the ventilator opening, the only part of this strange building that was not hermetically sealed against the hostile life of Inra. A dark rim had appeared at its margin, a loathsome, black-green rim that was moving, spreading out. It crept over the metal walls like the low-lying smoke of a fire, yet it was a solid. From it emanated a strong, miasmatic odor.

"The giant mold!" Forepaugh cried. He rushed to his desk and took out his flash pistol, quickly set the localizer so as to cover a large area. When he turned he saw, to his horror, Gunga about to smash into the mold with his ax. He sent the man spinning with a blow to the ear.

"Want to scatter it and start it growing in a half-dozen places?" he snapped. "Here!"

e pulled the trigger. There was a light, spiteful "ping" and for an instant a cone of white light stood out in the dim room like a solid thing. Then it was gone, and with it was gone the black mold, leaving a circular area of blistered paint on the wall and an acrid odor in the air. Forepaugh leaped to the ventilating louver and closed it tightly.[149]

"It's going to be like this from now on," he remarked to the shaken Gunga. "All these things wouldn't bother us as long as the machinery kept the building dry and cool. They couldn't live in here. But it's getting damp and hot. Look at the moisture condensing on the ceiling!"

Gunga gave a guttural cry of despair. "It knows, Boss; look!"

Through one of the round, heavily framed ports it could be seen, the lower part of its large, shapeless body half-floating in the lashing water that covered their rocky shelf to a depth of several feet, the upper part spectral and gray. It was a giant amoeba, fully six feet in diameter in its present spheroid form, but capable of assuming any shape that would be useful. It had an envelope of tough, transparent matter, and was filled with a fluid that was now cloudy and then clear. Near the center there was a mass of darker matter, and this was undoubtedly the seat of its intelligence.

The Earth man recoiled in horror! A single cell with a brain! It was unthinkable. It was a biological nightmare. Never before had he seen one—had, in fact, dismissed the stories of the Inranian natives as a bit of primitive superstition, had laughed at these gentle, stupid amphibians with whom he traded when they, in their imperfect language, tried to tell him of it.

They had called it the Ul-lul. Well, let it be so. It was an amoeba, and it was watching him. It floated in the downpour and watched him. With what? It had no eyes. No matter, it was watching him. And then it suddenly flowed outward until it became a disc rocking on the waves. Again its fluid form changed, and by a series of elongations and contractions it flowed through the water at an incredible speed. It came straight for the window, struck the thick, unbreakable glass with a shock that could be felt by the men inside. It flowed over the glass and over the building. It was trying to eat them, building and all! The part of its body over the port became so thin that it was almost invisible. At last, its absolute limit reached, it dropped away, baffled, vanishing amid the glare of the lightning and the frothing waters like the shadows of a nightmare.

he heat was intolerable and the air was bad.

"Haw, we have to open vent'lator, Boss!" gasped the Martian.

Forepaugh nodded grimly. It wouldn't do to smother either. Though to open the ventilator would be to invite another invasion by the black mold, not to mention the amoebae and other fabulous monsters that had up to now been kept at a safe distance by the repeller zone, a simple adaptation of a very old discovery. A zone of mechanical vibrations, of a frequency of 500,000 cycles per second, was created by a large quartz crystal in the water, which was electrically operated. Without power, the protective zone had vanished.

"We watch?" asked Gunga.

"You bet we watch. Every minute of the 'day' and 'night.'"

He examined the two chronometers, assuring himself that they were well wound, and congratulated himself that they were not dependent on the defunct power plant for energy. They were his only means of measuring the passage of time. The sun, which theoretically would seem to travel round and round the horizon, rarely succeeded in making its exact location known, but appeared to shift strangely from side to side at the whim of the fog and water.

"Th' fellas," Gunga remarked, coming out of a study. "Why not come?" He referred to the Inranians.

"Probably know something's wrong. They can tell the quartz oscillator is stopped. Afraid of the Ul-lul, I suppose."

"'Squeer," demurred the Martian. "Ul-lul not bother fellas."

"You mean it doesn't follow them[150] into the underbrush. But it would find tough going there. Not enough water; trees there, four hundred feet high with thorny roots and rough bark—they wouldn't like that. Oh no, these natives ought to be pretty snug in their dens. Why, they're as hard to catch as a muskrat! Don't know what a muskrat is, huh? Well, it's the same as the Inranians, only different, and not so ugly."

or the next six days they existed in their straitened quarters, one guarding while the other slept, but such alarms as they experienced were of a minor nature, easily disposed of by their flash pistol. It had not been intended for continuous service, and under the frequent drains it showed an alarming loss of power. Forepaugh repeatedly warned Gunga to be more sparing in its use, but that worthy persisted in his practice of using it against every trifling invasion of the poisonous Inranian cave moss that threatened them, or the warm, soggy water-spiders that hopefully explored the ventilator shaft in search of living food.

"Bash 'em with a broom, or something! Never mind if it isn't nice. Save our flash gun for something bigger."

Gunga only looked distressed.

On the seventh day their position became untenable. Some kind of sea creature, hidden under the ever-replenished storm waters, had found the concrete emplacements of their trading post to its liking. Just how it was done was never learned. It is doubtful that the creatures could gnaw away the solid stone—more likely the process was chemical, but none the less it was effective. The foundations crumbled; the metal shell subsided, rolled half over so that silty water leaked in through the straining seams, and threatened at any moment to be buffeted and urged away on the surface of the flood toward that distant vast sea which covers nine-tenths of the area of Inra.

"Time to mush for the mountains," Forepaugh decided.

Gunga grinned. The Mountains of Perdition were, to his point of view, the only part of Inra even remotely inhabitable. They were sometimes fairly cool, and though perpetually pelted with rain, blazing with lightning and reverberating with thunder, they had caves that were fairly dry and too cool for the black mold. Sometimes, under favorable circumstances on their rugged peaks, one could get the full benefit of the enormous hot sun for whose actinic rays the Martian's starved system yearned.

"Better pack a few cans of the food tablets," the white man ordered. "Take a couple of waterproof sleeping bags for us, and a few hundred fire pellets. You can have the flash pistol; it may have a few more charges in it."

orepaugh broke the glass case marked "Emergency Only" and removed two more flash pistols. Well he knew that he would need them after passing beyond the trading area—perhaps sooner. His eyes fell on his personal chest, and he opened it for a brief examination. None of the contents seemed of any value, and he was about to pass when he dragged out a long, heavy, .45 caliber six-shooter in a holster, and a cartridge belt filled with shells. The Martian stared.

"Know what it is?" his master asked, handing him the weapon.

"Gunga not know." He took it and examined it curiously. It was a fine museum piece in an excellent state of preservation, the metal overlaid with the patina of age, but free from rust and corrosion.

"It's a weapon of the Ancients," Forepaugh explained. "It was a sort of family heirloom and is over 300 years old. One of my grandfathers used it in the famous Northwest Mounted Police. Wonder if it'll still shoot."

He leveled the weapon at a fat, sightless wriggler that came squirming through a seam, squinting unaccus[151]tomed eyes along the barrel. There was a violent explosion, and the wriggler disappeared in a smear of dirty green. Gunga nearly fell over backward in fright, and even Forepaugh was shaken. He was surprised that the ancient cartridge had exploded at all, though he knew powder making had reached a high level of perfection before explosive chemical weapons had yielded to the newer, lighter, and infinitely more powerful ray weapons. The gun would impede their progress. It would be of very little use against the giant Carnivora of Inra. Yet something—perhaps a sentimental attachment, perhaps what his ancestors would have called a "hunch"—compelled him to strap it around his waist. He carefully packed a few essentials in his knapsack, together with one chronometer and a tiny gyroscopic compass. So equipped, they could travel with a fair degree of precision toward the mountains some hundred miles on the other side of a steaming forest, a-crawl with feral life, and hot with blood-lust.

an and master descended into the warm waters and, without a backward glance, left the trading post to its fate. There was not even any use in leaving a note. Their relief ship, soon due, would never find the station without radio direction.

The current was strong, but the water gradually became shallower as they ascended the sloping rock. After half an hour they saw ahead of them the loom of the forest, and with some trepidation they entered the gloom cast by the towering, fernlike trees, whose tops disappeared in murky fog. Tangled vines impeded their progress. Quagmires lay in wait for them, and tough weeds tripped them, sometimes throwing one or another into the mud among squirming small reptiles that lashed at them with spiked, poisonous feet and then fell to pieces, each piece to lie in the bubbling ooze until it grew again into a whole animal.

Several times they almost walked under the bodies of great, spheroidal creatures with massive short legs, whose tremendously long, sinuous necks disappeared in the leafy murk above, swaying gently like long-stalked lilies in a terrestial pond. These were azornacks, mild-tempered vegetarians whose only defense lay in their thick, blubbery hides. Filled with parasites, stinking and rancid, their decaying covering of fat effectively concealed the tender flesh underneath, protecting them from fangs and rending claws.

Deeper in the forest the battering of the rain was mitigated. Giant neo-palm leaves formed a roof that shut out not only most of the weak daylight, but also the fury of the downpour. The water collected in cataracts, ran down the boles of the trees, and roared through the semi-circular canals of the snake trees, so named by early explorers for their waving, rubbery tentacles, multiplied a millionfold, that performed the duties of leaves. Water gurgled and chuckled everywhere, spread in vast dim ponds and lakes writhing with tormented roots, up-heaved by unseen, uncatalogued leviathans, rippled by translucent discs of loathsome, luminescent jelly that quivered from place to place in pursuit of microscopic prey.

Yet the impression was one of calm and quiet, and the waifs from other worlds felt a surcease of nervous tension. Unconsciously they relaxed. Taking their bearings, they changed their course slightly for the nesting place of the nearest tribe of Inranians where they hoped to get food and at least partial shelter; for their food tablets had mysteriously turned to an unpleasant viscous liquid, and their sleeping bags were alive with giant bacteria easily visible to the eye.

hey were doomed to disappointment. After nearly twelve hours of desperate struggling through the morass, through gloomy aisles, and countless narrow escapes from prowling beasts of prey in which only the[152] speed and tremendous power of their flash pistols saved them from instant death, they reached a rocky outcropping which led to the comparatively dry rise of land on which a tribe of Inranians made its home. Their faces were covered with welts made by the hanging filaments of blood-sucking trees as fine as spider webs, and their senses reeled with the oppressive stench of the abysmal jungle. If the pampered ladies of the Inner Planets only knew where their thousand-dollar orchids sprang from!

Converging runways showed the opening of one of the underground dens, almost hidden from view by a bewildering maze of roots, rendered more formidable by long, sharp stakes made from the iron-hard thigh-bones of the flying kabo.

Forepaugh cupped his hands over his mouth and gave the call.

"Ouf! Ouf! Ouf! Ouf! Ouf!"

He repeated it over and over, the jungle giving back his voice in a muffled echo, while Gunga held a spare flash pistol and kept a sharp lookout for a carnivore intent on getting an unwary Inranian.

There was no answer. These timid creatures, who are often rated the most intelligent life native to primitive Inra, had sensed disaster and had fled.

Forepaugh and Gunga slept in one of the foul, poorly ventilated dens, ate of the hard, woody tubers that had not been worth taking along, and wished they had a certain stock clerk at that place at that time. They were awakened out of deep slumber by the threshing of an evil looking creature which had become entangled among the sharpened spikes. Its tremendous maw, splitting it almost in half, was opened in roars of pain that showed great yellow fangs eight inches in length. Its heavy flippers battered the stout roots and lacerated themselves in the beast's insensate rage. It was quickly dispatched with a flash pistol and Gunga cooked himself some of the meat, using a fire pellet; but despite his hunger Forepaugh did not dare eat any of it, knowing that this species, strange to him, might easily be one of the many on Inra that are poisonous to terrestials.

hey resumed their march toward the distant invisible mountains, and were fortunate in finding somewhat better footing than they had on their previous march. They covered about 25 miles on that "day," without untoward incident. Their ray pistols gave them an insuperable advantage over the largest and most ferocious beasts they could expect to meet, so that they became more and more confident, despite the knowledge that they were rapidly using up the energy stored in their weapons. The first one had long ago been discarded, and the charge indicators of the other two were approaching zero at a disquieting rate. Forepaugh took them both, and from that time on he was careful never to waste a discharge except in case of a direct and unavoidable attack. This often entailed long waits or stealthy detours through sucking mud, and came near to ending both their lives.

The Earth man was in the lead when it happened. Seeking an uncertain footing through a tangle of low-growing, thick, ghastly white vegetation, he placed a foot on what seemed to be a broad, flat rock projecting slightly above the ooze. Instantly there was a violent upheaval of mud; the seeming rock flew up like a trap-door, disclosing a cavernous mouth some seven feet across, and a thick, triangular tentacle flew up from its concealment in the mud in a vicious arc. Forepaugh leaped back barely in time to escape being swept in and engulfed. The end of the tentacle struck him a heavy blow on the chest, throwing him back with such force as to bowl Gunga over, and whirling the pistols out of his hands into a slimy, bulbous growth nearby, where they stuck in the phosphorescent cavities the force of their impact had made.[153]

here was no time to recover the weapons. With a bellow of rage the beast was out of its bed and rushing at them. Nothing stayed its progress. Tough, heavily scaled trees thicker than a man's body shuddered and fell as its bulk brushed by them. But it was momentarily confused, and its first rush carried it past its dodging quarry. This momentary respite saved their lives.

Rearing its plumed head to awesome heights, its knobby bark running with brown rivulets of water, a giant tree, even for that world of giants, offered refuge. The men scrambled up the rough trunk easily, finding plenty of hand and footholds. They came to rest on one of the shelflike circumvoluting rings, some twenty-five feet above the ground. Soon the blunt brown tentacles slithered in search of them, but failed to reach their refuge by inches.

And now began the most terrible siege that interlopers in that primitive world can endure. From that cavernous, distended throat came a tremendous, world-shaking noise.

"HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM!"

Forepaugh put his hand to his head. It made him dizzy. He had not believed that such noise could be. He knew that no creature could long live amidst it. He tore strips from his shredded clothing and stuffed his ears, but felt no relief.

"HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM!"

It throbbed in his brain.

Gunga lay a-sprawl, staring with fascinated eye into the pulsating scarlet gullet that was blasting the world with sound. Slowly, slowly he was slipping. His master hauled him back. The Martian grinned at him stupidly, slid again to the edge.

Once more Forepaugh pulled him back. The Martian seemed to acquiesce. His single eye closed to a mere slit. He moved to a position between Forepaugh and the tree trunk, braced his feet.

"No you don't!" The Earth man laughed uproariously. The din was making him light-headed. It was so funny! Just in time he had caught that cunning expression and prepared for the outlashing of feet designed to plunge him into the red cavern below and to stop that hellish racket.

"And now—"

He swung his fist heavily, slamming the Martian against the tree. The red eye closed wearily. He was unconscious, and lucky.

Hungrily the Earth man stared at his distant flash pistols, plainly visible in the luminescence of their fungus bedding. He began a slow, cautious creep along the top of a vine some eight inches thick. If he could reach them....

rash! He was almost knocked to the ground by the thud of a frantic tentacle against the vine. His movement had been seen. Again the tentacle struck with crushing force. The great vine swayed. He managed to reach the shelf again in the very nick of time.

"HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM!"

A bolt of lightning struck a giant fern some distance away. The crash of thunder was hardly noticeable. Forepaugh wondered if his tree would be struck. Perhaps it might even start a fire, giving him a flaming brand with which to torment his tormentor. Vain hope! The wood was saturated with moisture. Even the fire pellets could not make it burn.

"HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM!"

The six-shooter! He had forgotten it. He jerked it from its holster and pointed it at the red throat, emptied all the chambers. He saw the flash of yellow flame, felt the recoil, but the sound of the discharges was drowned in the Brobdignagian tumult. He drew back his arm to throw the useless toy from him. But again that unexplainable, senseless "hunch" restrained him.[154] He reloaded the gun and returned it to its holster.

"HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM! HOOM!"

A thought had been struggling to reach his consciousness against the pressure of the unbearable noise. The fire pellets! Couldn't they be used in some way? These small chemical spheres, no larger than the end of his little finger, had long ago supplanted actual fire along the frontiers, where electricity was not available for cooking. In contact with moisture they emitted terrific heat, a radiant heat which penetrated meat, bone, and even metal. One such pellet would cook a meal in ten minutes, with no sign of scorching or burning. And they had several hundred in one of the standard moisture-proof containers.

s fast as his fingers could work the trigger of the dispenser Forepaugh dropped the potent little pellets down the bellowing throat. He managed to release about thirty before the bellowing stopped. A veritable tornado of energy broke loose at the foot of the tree. The giant maw was closed, and the shocking silence was broken only by the thrashing of a giant body in its death agonies. The radiant heat, penetrating through and through the beast's body, withered nearby vegetation and could be easily felt on the perch up the tree.

Gunga was slowly recovering. His iron constitution helped him to rally from the powerful blow he had received, and by the time the jungle was still he was sitting up mumbling apologies.

"Never mind," said his master. "Shin down there and cut us off a good helping of roast tongue, if it has a tongue, before something else comes along and beats us out of a feast."

"Him poison, maybe," Gunga demurred. They had killed a specimen new to zoologists.

"Might as well die of poison as starvation," Forepaugh countered.

Without more ado the Martian descended, cut out some large, juicy chunks as his fancy dictated, and brought his loot back up the tree. The meat was delicious and apparently wholesome. They gorged themselves and threw away what they could not eat, for food spoils very quickly in the Inranian jungles and uneaten meat would only serve to attract hordes of the gauzy-winged, glutinous Inranian swamp flies. As they sank into slumber they could hear the beginning of a bedlam of snarling and fighting as the lesser Carnivora fed on the body of the fallen giant.

When they awoke the chronometer recorded the passing of twelve hours, and they had to tear a network of strong fibers with which the tree had invested them preparatory to absorbing their bodies as food. For so keen is the competition for life on Inra that practically all vegetation is capable of absorbing animal food directly. Many an Inranian explorer can tell tales of narrow escapes from some of the more specialized flesh-eating plants; but they are now so well known that they are easily avoided.

clean-picked framework of crushed and broken giant bones was all that was left of the late bellowing monster. Six-legged water dogs were polishing them hopefully, or delving into them with their long, sinuous snouts for the marrow. The Earth man fired a few shots with his six-shooter, and they scattered, dragging the bodies of their fallen companions to a safe distance to be eaten.

Only one of the flash pistols was in working order. The other had been trampled by heavy hoofs and was useless. A heavy handicap under which to traverse fifty miles of abysmal jungle. They started with nothing for breakfast except water, of which they had plenty.

Fortunately the outcroppings of rocks and gravel washes were becoming more and more frequent, and they were[155] able to travel at much better speed. As they left the low-lying jungle land they entered a zone which was faintly reminiscent of a terrestial jungle. It was still hot, soggy, and fetid, but gradually the most primitive aspects of the scene were modified. The over-arching trees were less closely packed, and they came across occasional rock clearings which were bare of vegetation except for a dense carpet of brown, lichenlike vegetation that secreted an astonishing amount of juice. They slipped and sloshed through this, rousing swarms of odd, toothed birds, which darted angrily around their heads and slashed at them with the razor-sharp saw edges on the back of their legs. Annoying as they were, they could be kept away with branches torn from trees, and their presence connoted an absence of the deadly jungle flesh-eaters, permitting a temporary relaxation of vigilance and saving the resources of the last flash gun.

They camped that "night" on the edge of one of these rock clearings. For the first time in weeks it had stopped raining, although the sun was still obscured. Dimly on the horizon could be seen the first of the foothills. Here they gathered some of the giant, oblong fungus that early explorers had taken for blocks of porous stone because of their size and weight, and, by dint of the plentiful application of fire pellets, managed to set it ablaze. The heat added nothing to their comfort, but it dried them out and allowed them to sleep unmolested.

n unwary winged eel served as their breakfast, and soon they were on their way to those beckoning hills. It had started to rain again, but the worst part of their journey was over. If they could reach the top of one of the mountains there was a good chance that they would be seen and rescued by their relief ship, provided they did not starve first. The flyer would use the mountains as a base from which to search for the trading station, and it was conceivable that the skipper might actually have anticipated their desperate adventure and would look for them in the Mountains of Perdition.

They had crossed several ranges of the foothills and were beginning to congratulate themselves when the diffused light from above was suddenly blotted out. It was raining again, and above the echo-augmented thunder they heard a shrill screeching.

"A web serpent!" Gunga cried, throwing himself flat on the ground.

Forepaugh eased into a rock cleft at his side. Just in time. A great grotesque head bore down upon him, many-fanged as a medieval dragon. Between obsidian eyes was a fissure whence emanated a wailing and a foul odor. Hundreds of short, clawed legs slithered on the rocks under a long sinuous body. Then it seemed to leap into the air again. Webs grew taut between the legs, strumming as they caught a strong uphill wind. Again it turned to the attack, and missed them. This time Forepaugh was ready for it. He shot at it with his flash pistol.

othing happened. The fog made accurate shooting impossible, and the gun lacked its former power. The web serpent continued to course back and forth over their heads.

"Guess we'd better run for it," Forepaugh murmured.

"Go 'head!"

They cautiously left their places of concealment. Instantly the serpent was down again, persistent if inaccurate. It struck the place of their first concealment and missed them.

"Run!"

They extended their weary muscles to the utmost, but it was soon apparent that they could not escape long. A rock wall in their path saved them.

"Hole!" the Martian gasped.

Forepaugh followed him into the rocky cleft. There was a strong draft of dry air, and it would have been next[156] to impossible to hold the Martian back, so Forepaugh allowed him to lead on toward the source of the draft. As long as it led into the mountains he didn't care.

The natural passageway was untenanted. Evidently its coolness and dryness made it untenable for most of Inra's humidity and heat loving life. Yet the floor was so smooth that it must have been artificially leveled. Faint illumination was provided by the rocks themselves. They appeared to be covered by some microscopic phosphorescent vegetation.

After hundreds of twists and turns and interminable straight galleries the cleft turned more sharply upward, and they had a period of stiff climbing. They must have gone several miles and climbed at least 20,000 feet. The air became noticeably thin, which only exhilarated Gunga, but slowed the Earth man down. But at last they came to the end of the cleft. They could go no further, but above them, at least 500 feet higher, they saw a round patch of sky, miraculously bright blue sky!

"A pipe!" Forepaugh cried.

He had often heard of these mysterious, almost fabulous structures sometimes reported by passing travelers. Straight and true, smooth as glass and apparently immune to the elements, they had been occasionally seen standing on the very tops of the highest mountains—seen for a few moments only before they were hidden again by the clouds. Were they observatories of some ancient race, placed thus to pierce the mysteries of outer space? They would find out.

he inside of the pipe had zigzagging rings of metal, conveniently spaced for easy climbing. With Gunga leading, they soon reached the top. But not quite.

"Eh?" said Forepaugh.

"Uh?" said Gunga.

There had not been a sound, but a distinct, definite command had registered on their minds.

"Stop!"

They tried to climb higher, but could not unclasp their hands. They tried to descend, but could not lower their feet.

The light was by now relatively bright, and as by command their eyes sought the opposite wall. What they saw gave their jaded nerves an unpleasant thrill—a mass of doughy matter of a blue-green color about three feet in diameter, with something that resembled a cyst filled with transparent liquid near its center.

And this thing began to flow along the rods, much as tar flows. From the mass extended a pseudopod; touched Gunga on the arm. Instantly the arm was raw and bleeding. Terrified, immovable, he writhed in agony. The pseudopod returned to the main mass, disappearing into its interior with the strip of bloody skin.

Its attention was centered so much on the luckless Martian that its control slipped from Forepaugh. Seizing his flash pistol, he set the localized for a small area and aimed it at the thing, intent on burning it into nothingness. But again his hand was stayed. Against the utmost of his will-power his fingers opened, letting the pistol drop. The liquid in the cyst danced and bubbled. Was it laughing at him? It had read his mind—thwarted his will again.

Again a pseudopod stretched out and a strip of raw, red flesh adhered to it and was consumed. Mad rage convulsed the Earth man. Should he throw himself tooth and nail on the monster? And be engulfed?

He thought of the six-shooter. It thrilled him.

But wouldn't it make him drop that too?

flash of atavistic cunning came to him.

He began to reiterate in his mind a certain thought.

"This thing is so I can see you better—this thing is so I can see you better."

He said it over and over, with all the[157] passion and devotion of a celibate's prayer over a uranium fountain.

"This thing is harmless—but it will make me see you better!"

Slowly he drew the six-shooter. In some occult way he knew it was watching him.

"Oh, this is harmless! This is an instrument to aid my weak eyes! It will help me realize your mastery! This will enable me to know your true greatness. This will enable me to know you as a god."

Was it complacence or suspicion that stirred the liquid in the cyst so smoothly? Was it susceptible to flattery? He sighted along the barrel.

"In another moment your great intelligence will overwhelm me," proclaimed his surface mind desperately, while the subconscious tensed the trigger. And at that the clear liquid burst into a turmoil of alarm. Too late. Forepaugh went limp, but not before he had loosed a steel-jacketed bullet that shattered the mind cyst of the pipe denizen. A horrible pain coursed through his every fibre and nerve. He was safe in the arms of Gunga, being carried to the top of the pipe to the clean dry air, and the blessed, blistering sun.

The pipe denizen was dying. A viscous, inert mass, it dropped lower and lower, lost contact at last, shattered into slime at the bottom.

iraculous sun! For a luxurious fifteen minutes they roasted there on the top of the pipe, the only solid thing in a sea of clouds as far as the eye could reach. But no! That was a circular spot against the brilliant white of the clouds, and it was rapidly coming closer. In a few minutes it resolved itself into the Comet, fast relief ship of the Terrestial, Inranian, Genidian, and Zydian Lines, Inc. With a low buzz of her repulsion motors she drew alongside. Hooks were attached and ports opened. A petty officer and a crew of roustabouts made her fast.

"What the hell's going on here?" asked the cocky little terrestial who was skipper, stepping out and surveying the castaways. "We've been looking for you ever since your directional wave failed. But come on in—come on in!"

He led the way to his stateroom, while the ship's surgeon took Gunga in charge. Closing the door carefully, he delved into the bottom of his locker and brought out a flask.

"Can't be too careful," he remarked, filling a small tumbler for himself and another for his guest. "Always apt to be some snooper to report me. But say—you're wanted in the radio room."

"Radio room nothing! When do we eat?"

"Right away, but you'd better see him. Fellow from the Interplanetary News Agency wants you to broadcast a copyrighted story. Good for about three years' salary, old boy."

"All right. I'll see him"—with a happy sigh—"just as soon as I put through a personal message."

n the day of the next full moon every living thing on earth will be wiped out of existence—unless you succeed in your mission, Lee."

Nathaniel Lee looked into the face of Silas Stark, President of the United States of the World, and nodded grimly. "I'll do my best, Sir," he answered.

"You have the facts. We know who this self-styled Black Caesar is, who has declared war upon humanity. He is a Dane named Axelson, whose father, condemned to life imprisonment for resisting the new world-order, succeeded in obtaining possession of an interplanetary liner.

"He filled it with the gang of desperate men who had been associated with him in his successful escape from the penitentiary. Together they sailed into Space. They disappeared. It was supposed that they had somehow met their death in the ether, beyond the range of human ken.

"Thirty years passed, and then this son of Axelson, born, according to his own story, of a woman whom the[159] father had persuaded to accompany him into Space, began to radio us. We thought at first it was some practical joker who was cutting in.

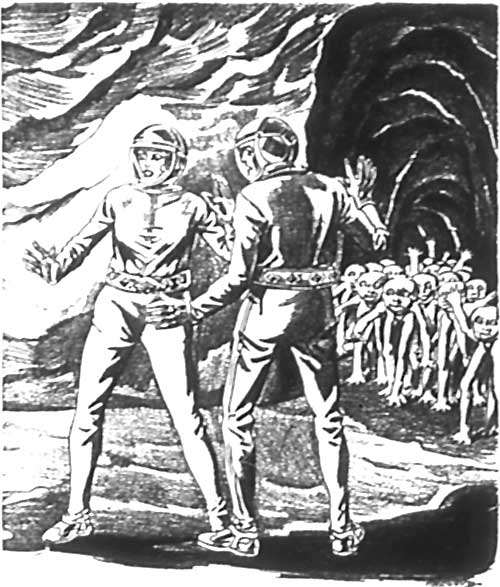

It was like struggling with some vampire creatures in

a hideous dream.

It was like struggling with some vampire creatures in

a hideous dream.

"When our electricians demonstrated beyond doubt that the voice came from outer space, it was supposed that some one in our Moon Colony had acquired a transmitting machine. Then the ships we sent to the Moon Colony for gold failed to return. As you know, for seven weeks there has been no communication with the Moon. And at the last full moon the—blow—fell.

"The world depends upon you, Lee. The invisible rays that destroyed every living thing from China to Australia—one-fifth of the human race—will fall upon the eastern seaboard of America when the moon is full again. That has been the gist of Axelson's repeated communications.

"We shall look to you to return, either with the arch-enemy of the human race as your prisoner, or with the good news that mankind has been set free from the menace that overhangs it.

"God bless you, my boy!" The President of the United States of the World gripped Nat's hand and stepped down the ladder that led from the landing-stage of the great interplanetary space-ship.

he immense landing-field reserved for the ships of the Interplanetary Line was situated a thousand feet above the heart of New York City, in Westchester County. It was a flat space set on the top of five great towers, strewn with electrified sand, whose glow had the property of dispersing the sea fogs. There, at rest upon what resembled nothing so much as iron claws, the long gray shape of the vacuum flyer bulked.

Nat sneezed as he watched the operations of his men, for the common cold, or coryza, seemed likely to be the last of the germ diseases that would yield to medical science, and he had caught a bad one in the Capitol, while listening to the debate in the Senate upon the threat to humanity. And it was cold on the landing-stage, in contrast to the perpetual summer of the glass-roofed city below.

But Nat forgot the cold as he watched the preparations for the ship's departure. Neon and nitrogen gas were being pumped under pressure into the outer shell, where a minute charge of leucon, the newly discovered element that helped to counteract gravitation, combined with them to provide the power that would lift the vessel above the regions of the stratosphere.

In the low roof-buildings that surrounded the stage was a scene of tremendous activity. The selenium discs were flashing signals, and the radio receivers were shouting the late news; on the great power boards dials and light signals stood out in the glow of the amylite tubes. On a rotary stage a thousand feet above the ship a giant searchlight, visible for a thousand miles, moved its shaft of dazzling luminosity across the heavens.

Now the spar-aluminite outer skin of the ship grew bright with the red neon glare. Another ship, from China, dropped slowly to its stage near by, and the unloaders swarmed about the pneumatic tubes to receive the mail. The teleradio was shouting news of a failure of the Manchurian wheat crop. Nat's chief officer, a short cockney named Brent, came up to him.

"Ready to start, Sir," he said.

at turned to him. "Your orders are clear?"

"Yes, Sir."

"Send Benson here."

"I'm here, Sir." Benson, the ray-gunner in charge of the battery that[160] comprised the vessel's armament, a lean Yankee from Connecticut, stepped forward.

"You know your orders, Benson? Axelson has seized the Moon and the gold-mines there. He's planning to obliterate the Earth. We've got to go in like mad dogs and shoot to kill. No matter if we kill every living thing there, even our own people who are inmates of the Moon's penal settlement, we've got to account for Axelson."

"Yes, Sir."

"We can't guess how he got those gold-ships that returned with neon and argon for the Moon colonists. But he mustn't get us. Let the men understand that. That's all."

"Very good, Sir."

The teleradio suddenly began to splutter: A-A-A, it called. And instantly every sound ceased about the landing-stage. For that was the call of Axelson, somewhere upon the Moon.

"Axelson speaking. At the next full moon all the American Province of the World Federation will be annihilated, as the Chinese Province was at the last. There's no hope for you, good people. Send out your vacuum liners. I can use a few more of them. Within six months your world will be depopulated, unless you flash me the signal of surrender."

Would the proud old Earth have to come to that? Daily those ominous threats had been repeated, until popular fears had become frenzy. And Nat was being sent out as a last hope. If he failed, there would be nothing but surrender to this man, armed with a super-force that enabled him to lay waste the Earth from the Moon.

Within one hour, those invisible, death-dealing rays had destroyed everything that inhaled oxygen and exhaled carbon. The ray with which the liner was equipped was a mere toy in comparison. It would kill at no more than 500 miles, and its action was quite different.

As a prelude to Earth's surrender, Axelson demanded that World President Stark and a score of other dignitaries should depart for the Moon as hostages. Every ray fortress in the world was to be dismantled, every treasury was to send its gold to be piled up in a great pyramid on the New York landing-stage. The Earth was to acknowledge Axelson as its supreme master.

he iron claws were turning with a screwlike motion, extending themselves, and slowly raising the interplanetary vessel until she looked like a great metal fish with metal legs ending with suckerlike disks. But already she was floating free as the softly purring engines held her in equipoise. Nat climbed the short ladder that led to her deck. Brent came up to him again.

"That teleradio message from Axelson—" he began.

"Yes?" Nat snapped out.

"I don't believe it came from the Moon at all."

"You don't? You think it's somebody playing a hoax on Earth? You think that wiping out of China was just an Earth-joke?"

"No, Sir." Brent stood steady under his superior's sarcasm. "But I was chief teleradio operator at Greenwich before being promoted to the Province of America. And what they don't know at Greenwich they don't know anywhere."

Brent spoke with that self-assurance of the born cockney that even the centuries had failed to remove, though they had removed the cockney accent.

"Well, Brent?"

"I was with the chief electrician in the receiving station when Axelson was radioing last week. And I noticed that the waves of sound were under a slight Doppler effect. With the immense magnification necessary for transmitting from the Moon, such deflection might be construed as a mere fan-like extension. But there was ten times the magnification one would expect from the Moon; and I calculated[161] that those sound-waves were shifted somewhere."

"Then what's your theory, Brent?"

"Those sounds come from another planet. Somewhere on the Moon there's an intercepting and re-transmitting plant. Axelson is deflecting his rays to give the impression that he's on the Moon, and to lure our ships there."

"What do you advise?" asked Nat.

"I don't know, Sir."

"Neither do I. Set your course Moonward, and tell Mr. Benson to keep his eyes peeled."

he Moon Colony, discovered in 1976, when Kramer, of Baltimore, first proved the practicability of mixing neon with the inert new gas, leucon, and so conquering gravitation, had proved to be just what it had been suspected of being—a desiccated, airless desolation. Nevertheless, within the depths of the craters a certain amount of the Moon's ancient atmosphere still lingered, sufficient to sustain life for the queer troglodytes, with enormous lung-boxes, who survived there, browsing like beasts upon the stunted, aloe-like vegetation.

Half man, half ape, and very much unlike either, these vestiges of a species on a ruined globe had proved tractable and amenable to discipline. They had become the laborers of the convict settlement that had sprung up on the Moon.

Thither all those who had opposed the establishment of the World Federation, together with all persons convicted for the fourth time of a felony, had been transported, to superintend the efforts of these dumb, unhuman Moon dwellers. For it had been discovered that the Moon craters were extraordinarily rich in gold, and gold was still the medium of exchange on Earth.

To supplement the vestigial atmosphere, huge stations had been set up, which extracted the oxygen from the subterranean waters five miles below the Moon's crust, and recombined it with the nitrogen with which the surface layer was impregnated, thus creating an atmosphere which was pumped to the workers.

Then a curious discovery had been made. It was impossible for human beings to exist without the addition of those elements existing in the air in minute quantities—neon, krypton, and argon. And the ships that brought the gold bars back from the Moon had conveyed these gaseous elements there.

he droning of the sixteen atomic motors grew louder, and mingled with the hum of gyroscopes. The ladder was drawn up and the port hole sealed. On the enclosed bridge Nat threw the switch of durobronze that released the non-conducting shutter which gave play to the sixteen great magnets. Swiftly the great ship shot forward into the air. The droning of the motors became a shrill whine, and then, growing too shrill for human ears to follow it, gave place to silence.

Nat set the speed lever to five hundred miles an hour, the utmost that had been found possible in passing through the earth's atmosphere, owing to the resistance, which tended to heat the vessel and damage the delicate atomic engines. As soon as the ether was reached, the speed would be increased to ten or twelve thousand. That meant a twenty-two hour run to the Moon Colony—about the time usually taken.

He pressed a lever, which set bells ringing in all parts of the ship. By means of a complicated mechanism, the air was exhausted from each compartment in turn, and then replaced, and as the bells rang, the men at work trooped out of these compartments consecutively. This had been originated for the purpose of destroying any life dangerous to man that might unwittingly have been imported from the Moon, but on one occasion it had resulted in the discovery of a stowaway.

Then Nat descended the bridge to[162] the upper deck. Here, on a platform, were the two batteries of three ray-guns apiece, mounted on swivels, and firing in any direction on the port and starboard sides respectively. The guns were enclosed in a thin sheath of osmium, through which the lethal rays penetrated unchanged; about them, thick shields of lead protected the gunners.

He talked with Benson for a while. "Don't let Axelson get the jump on you," he said. "Be on the alert every moment." The gunners, keen-looking men, graduates from the Annapolis gunnery school, grinned and nodded. They were proud of their trade and its traditions; Nat felt that the vessel was safe in their hands.

The chief mate appeared at the head of the companion, accompanied by a girl. "Stowaway, Sir," he reported laconically. "She tumbled out of the repair shop annex when we let out the air!"

at stared at her in consternation, and the girl stared back at him. She was a very pretty girl, hardly more than twenty-two or three, attired in a businesslike costume consisting of a leather jacket, knickers, and the black spiral puttees that had come into style in the past decade. She came forward unabashed.

"Well, who are you?" snapped Nat.

"Madge Dawes, of the Universal News Syndicate," she answered, laughing.

"The devil!" muttered Nat. "You people think you run the World Federation since you got President Stark elected."

"We certainly do," replied the girl, still laughing.

"Well, you don't run this ship," said Nat. "How would you like a long parachute drop back to Earth?"

"Don't be foolish, my dear man," said Madge. "Don't you know you'll get wrinkles if you scowl like that? Smile! Ah, that's better. Now, honestly, Cap we just had to get the jump on everybody else in interviewing Axelson. It means such a lot to me."

Pouts succeeded smiles. "You're not going to be cross about it, are you?" she pleaded.

"Do you realize the risk you're running, young woman?" Nat demanded. "Are you aware that our chances of ever getting back to Earth are smaller than you ought to have dreamed of taking?"

"Oh, that's all right," the girl responded. "And now that we're friends again, would you mind asking the steward to get me something to eat? I've been cooped up in that room downstairs for fifteen hours, and I'm simply starving."

Nat shrugged his shoulders hopelessly. He turned to the chief mate. "Take Miss Dawes down to the saloon and see that Wang Ling supplies her with a good meal," he ordered. "And put her in the Admiral's cabin. That good enough for you?" he asked satirically.

"Oh that'll be fine," answered the girl enthusiastically. "And I shall rely on you to keep me posted about everything that's going on. And a little later I'm going to take X-ray photographs of you and all these men." She smiled at the grinning gunners. "That's the new fad, you know, and we're going to offer prizes for the best developed skeletons in the American Province, and pick a King and Queen of Beauty!"

radio, Sir!"

Nat, who had snatched a brief interval of sleep, started up as the man on duty handed him the message. The vessel had been constantly in communication with Earth during her voyage, now nearing completion, but the dreaded A-A-A that prefaced this message told Nat that it came from Axelson.

"Congratulations on your attempt," the message ran, "I have watched your career with the greatest interest, Lee, through the medium of such scraps of[163] information as I have been able to pick up on the Moon. When you are my guest to-morrow I shall hope to be able to offer you a high post in the new World Government that I am planning to establish. I need good men. Fraternally, the Black Caesar."

Nat whirled about. Madge Dawes was standing behind him, trying to read the message over his shoulder.

"Spying, eh?" said Nat bitterly.

"My dear man, isn't that my business?"

"Well, read this, then," said Nat, handing her the message. "You're likely to repent this crazy trick of yours before we get much farther."

And he pointed to the cosmic-ray skiagraph of the Moon on the curved glass dome overhead. They were approaching the satellite rapidly. It filled the whole dome, the craters great black hollows, the mountains standing out clearly. Beneath the dome were the radium apparatus that emitted the rays by which the satellite was photographed cinematographically, and the gyroscope steering apparatus by which the ship's course was directed.

Suddenly a buzzer sounded a warning. Nat sprang to the tube.

"Gravitational interference X40, gyroscopic aberrancy one minute 29," he called. "Discharge static electricity from hull. Mr. Benson, stand by."

"What does that mean?" asked Madge.

"It means I shall be obliged if you'll abstain from speaking to the man at the controls," snapped Nat.

"And what's that?" cried Madge in a shriller voice, pointing upward.

cross the patterned surface of the Moon, shown on the skiagraph, a black, cigar-shaped form was passing. It looked like one of the old-fashioned dirigibles, and the speed with which it moved was evident from the fact that it was perceptibly traversing the Moon's surface. Perhaps it was travelling at the rate of fifty thousand miles an hour.

Brent, the chief officer, burst up the companion. His face was livid.

"Black ship approaching us from the Moon, Sir," he stammered. "Benson's training his guns, but it must be twenty thousands miles away."

"Yes, even our ray-guns won't shoot that distance," answered Nat. "Tell Benson to keep his guns trained as well as he can, and open fire at five hundred."

Brent disappeared. Madge and Nat were alone on the bridge. Nat was shouting incomprehensible orders down the tube. He stopped and looked up. The shadow of the approaching ship had crossed the Moon's disk and disappeared.

"Well, young lady, I think your goose is cooked," said Nat. "If I'm not mistaken, that ship is Axelson's, and he's on his way to knock us galley-west. And now oblige me by leaving the bridge."

"I think he's a perfectly delightful character, to judge from that message he sent you," answered Madge, "and—"

Brent appeared again. "Triangulation shows ten thousand miles, Sir," he informed Nat.

"Take control," said Nat. "Keep on the gyroscopic course, allowing for aberrancy, and make for the Crater of Pytho. I'll take command of the guns." He hurried down the companion, with Madge at his heels.

he gunners stood by the ray-guns, three at each. Benson perched on a revolving stool above the batteries. He was watching a periscopic instrument that connected with the bridge dome by means of a tube, a flat mirror in front of him showing all points of the compass. At one edge the shadow of the black ship was creeping slowly forward.

"Eight thousand miles, Sir," he told Nat. "One thousand is our extreme range. And it looks as if she's making for our blind spot overhead."

Nat stepped to the speaking-tube. "Try to ram her," he called up to[164] Brent. "We'll open with all guns, pointing forward."

"Very good, Sir," the Cockney called back.

The black shadow was now nearly in the centre of the mirror. It moved upward, vanished. Suddenly the atomic motors began wheezing again. The wheeze became a whine, a drone.

"We've dropped to two thousand miles an hour, Sir," called Brent.

Nat leaped for the companion. As he reached the top he could hear the teleradio apparatus in the wireless room overhead begin to chatter:

"A-A-A. Don't try to interfere. Am taking you to the Crater of Pytho. Shall renew my offer there. Any resistance will be fatal. Axelson."

And suddenly the droning of the motors became a whine again, then silence. Nat stared at the instrument-board and uttered a cry.

"What's the matter?" demanded Madge.

Nat swung upon her. "The matter?" he bawled. "He's neutralized our engines by some infernal means of his own, and he's towing us to the Moon!"

he huge sphere of the Moon had long since covered the entire dome. The huge Crater of Pytho now filled it, a black hollow fifty miles across, into which they were gradually settling. And, as they settled, the pale Earth light, white as that of the Moon on Earth, showed the gaunt masses of bare rock, on which nothing grew, and the long stalactites of glassy lava that hung from them.

Then out of the depths beneath emerged the shadowy shape of the landing-stage.

"You are about to land," chattered the radio. "Don't try any tricks; they will be useless. Above all, don't try to use your puny ray. You are helpless."

The ship was almost stationary. Little figures could be seen swarming upon the landing-stage, ready to adjust the iron claws to clamp the hull. With a gesture of helplessness, Nat left the bridge and went down to the main deck where, in obedience to his orders, the crew had all assembled.

"Men, I'm putting it up to you," he said. "Axelson, the Black Caesar, advises us not to attempt to use the Ray-guns. I won't order you to. I'll leave the decision with you."

"We tried it fifteen minutes ago, Sir," answered Benson. "I told Larrigan to fire off the stern starboard gun to see if it was in working order, and it wasn't!"

At that moment the vessel settled with a slight jar into the clamps. Once more the teleradio began to scream:

"Open the port hold and file out slowly. Resistance is useless. I should turn my ray upon you and obliterate you immediately. Assemble on the landing-stage and wait for me!"

"You'd best obey," Nat told his men. "We've got a passenger to consider." He glared at Madge as he spoke, and Madge's smile was a little more tremulous than it had been before.

"This is the most thrilling experience of my life, Captain Lee," she said. "And I'll never rest until I've got an X-Ray photograph of Mr. Axelson's skeleton for the Universal News Syndicate."

ne by one, Nat last, the crew filed down the ladder onto the landing-stage, gasping and choking in the rarefied air that lay like a blanket at the bottom of the crater. And the reason for this was only too apparent to Nat as soon as he was on the level stage.

Overhead, at an altitude of about a mile, the black ship hung, and from its bow a stupendous searchlight played to and fro over the bottom of the crater, making it as light as day. And where had been the mining machinery, the great buildings that had housed convicts and Moon people, and the huge edifice that contained the pumping station, there was—nothing.

The devilish ray of Axelson had not merely destroyed them, it had obliterated all traces of them, and the crew[165] of the liner were breathing the remnants of the atmosphere that still lay at the bottom of the Crater of Pytho.

But beside the twin landing-stages, constructed by the World Federation, another building arose, with an open front. And that front was a huge mirror, now scintillating under the searchlight from the black ship.

"That's it, Sir!" shouted Brent.

"That's what?" snapped Nat.

"The deflecting mirror I was speaking of. That's what deflected the ray that wiped out China. The ray didn't come from the Moon. And that's the mirror that deflects the teleradio waves, the super-Hertzian rays that carry the sound."

Nat did not answer. Sick at heart at the failure of his mission, he was watching the swarm of Moon men who were at work upon the landing-stage, turning the steel clamps and regulating the mechanism that controlled the apparatus. Dwarfed, apish creature, with tiny limbs, and chests that stood out like barrels, they bustled about, chattering in shrill voices that seemed like the piping of birds.

It was evident that Axelson, though he had wiped out the Moon convicts and the Moon people in the crater, had reserved a number of the latter for personal use.

he black ship was dropping into its position at the second landing-stage, connected with the first by a short bridge. The starboard hold swung open, and a file of shrouded and hooded forms appeared, masked men, breathing in condensed air from receptacles upon their chests, and staring with goggle eyes at their captives. Each one held in his hand a lethal tube containing the ray, and, as if by command, they took up their stations about their prisoners.

Then, at a signal from their leader, they suddenly doffed their masks.

Nat looked at them in astonishment. He had not known whether these would be Earth denizens or inhabitants of some other planet. But they were Earth men. And they were old.

Men of sixty or seventy, years, with long, gray beards and wrinkled faces, and eyes that stared out from beneath penthouses of shaggy eyebrows. Faces on which were imprinted despair and hopelessness.

Then the first man took off his mask and Nat saw a man of different character.

A man in the prime of life, with a mass of jet black hair and a black beard that swept to his waist, a nose like a hawk's, and a pair of dark blue eyes that fixed themselves on Nat's with a look of Luciferian pride.

"Welcome, Nathaniel Lee," said the man, in deep tones that had a curious accent which Nat could not place. "I ought to know your name, since your teleradios on Earth have been shouting it for three days past as that of the man who is to save Earth from the threat of destruction. And you know me!"

"Axelson—the Black Caesar," Nat muttered. For the moment he was taken aback. He had anticipated any sort of person except this man, who stood, looked, and spoke like a Viking, this incarnation of pride and strength.

Axelson smiled—and then his eyes lit upon Madge Dawes. And for a moment he stood as if petrified into a block of massive granite.

"What—who is this?" he growled.

"Why, I'm Madge Dawes, of the Universal News Syndicate," answered the girl, smiling at Axelson in her irrepressible manner. "And I'm sure you're not nearly such a bold, bad pirate as people think, and you're going to let us all go free."

nstantly Axelson seemed to become transformed into a maniac. He turned to the old men and shouted in some incomprehensible language. Nat and Madge, Brent and Benson, and two others who wore the uniforms of officers were seized and dragged across the bridge to the landing-stage where[166] the black ship was moored. The rest of the crew were ordered into a double line.

And then the slaughter began.

Before Nat could even struggle to break away from the gibbering Moon men to whom he and the other prisoners had been consigned, the aged crew of the Black Caesar had begun their work of almost instantaneous destruction.

Streams of red and purple light shot from the ray-pistols that they carried, and before them the crew of the ether-liner simply withered up and vanished. They became mere masses of human débris piled on the landing-stage, and upon these masses, too, the old men turned their implements, until only a few heaps of charred carbon remained on the landing-stage, impalpable as burned paper, and slowly rising in the low atmospheric pressure until they drifted over the crater.

Nat had cried out in horror at the sight, and tried to tear himself free from the grasp of the Moon dwarfs who held him. So had the rest. Never was struggle so futile. Despite their short arms and legs, the Moon dwarfs held them in an unshakable grip, chattering and squealing as they compressed them against their barrel-like chests until the breath was all but crushed out of their bodies.

"Devil!" cried Nat furiously, as Axelson came up to him. "Why don't you kill us, too?" And he hurled furious taunts and abuse at him, in the hope of goading him into making the same comparatively merciless end of his prisoners.

Axelson looked at him calmly, but made no reply. He looked at Madge again, and his features were convulsed with some emotion that gave him the aspect of a fiend. And then only did Nat realize that it was Madge who was responsible for the Black Caesar's madness.

Axelson spoke again, and the prisoners were hustled up the ladder and on board the black vessel.

he Kommandant-Kommissar will see you!" The door of their prison had opened, letting in a shaft of light, and disclosing one of the graybeards, who stood there, pointing at Nat.

"The—who?" Nat demanded.

"The Kommandant-Kommissar, Comrade Axelson," snarled the graybeard.

Nat knew what that strange jargon meant. He had read books about the political sect known as Socialists who flourished in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, and, indeed, were even yet not everywhere extinct. And with that a flash of intuition explained the presence of these old men on board.

These were the men who had been imprisoned in their youth, with Axelson's father, and had escaped and made their way into space, and had been supposed dead long since. Somewhere they must have survived.

And here they were, speaking a jargon of past generations, and ignorant that the world had changed, relics of the past, dead as the dead Moon from which the black ship was winging away through the ether.

"Don't go, Captain," pleaded Madge. "Tell him we'll all go together."

Nat shook his head. "Maybe I'll be able to make terms with him," he answered, and stepped out upon the vessel's deck.

The graybeard slammed the door and laughed savagely. "You'll make no terms with the Black Caesar," he said. "This is the reign of the proletariat. The bourgeois must die! So Lenin decreed!"

But he stopped suddenly and passed his hand over his forehead like a man awakening from a dream.

"Surely the proletariat has already triumphed on earth?" he asked. "A long time has passed, and daily we expect the summons to return and establish the new world-order. What year is this? Is it not 2017? It is so hard to reckon on Eros."

"On Eros?" thought Nat. "This is the year 2044," he answered. "You've[167] been dreaming, my friend. We've had our new world-order, and it's not in the least like the one you and your friends anticipated."

"Gott!" screamed the old man. "Gott, you're lying to me, bourgeois! You're lying, I tell you!"

o Eros was their destination! Eros, one of the asteroids, those tiny fragments of a broken planet, lying outside the orbit of Mars. Some of these little worlds, of which more than a thousand are known to exist, are no larger than a gentleman's country estate; some are mere rocks in space. Eros, Nat knew, was distinguished among them from the fact that it had an eccentric orbit, which brought it at times nearer Earth than any other heavenly body except the Moon.

Also that it had only been known for thirty years, and that it was supposed to be a double planet, having a dark companion.

That was in Nat's mind as he ascended the bridge to where Axelson was standing at the controls, with one of the graybeards beside him. The door of his stateroom was open, and suddenly there scuttled out of it one of the most bestial objects Nat had ever seen.

It was a Moon woman, a dwarfish figure, clothed in a shapeless garment of spun cellulose, and in her arms she held a heavy-headed Moon baby, whose huge chest stood up like a pyramid, while the tiny arms and legs hung dangling down.

"Here is the bourgeois, Kommandant," said Nat's captor.

Axelson looked at Nat, eye meeting eye in a slow stare. Then he relinquished the controls to the graybeard beside him, and motioned Nat to precede him into the stateroom.

Nat entered. It was an ordinary room, much like that of the captain of the ether-liner now stranded on the Moon. There were a bunk, chairs, a desk and a radio receiver.

Axelson shut the door. He tried to speak and failed to master his emotion. At last he said:

"I am prepared to offer you terms, Nathaniel Lee, in accordance with my promise."

"I'll make no terms with murderers," replied Nat bitterly.

xelson stood looking at him. His great chest rose and fell. Suddenly he put out one great hand and clapped Nat on the shoulder.

"Wise men," he said, "recognize facts. Within three weeks I shall be the undisputed ruler of Earth. Whether of a desert or of a cowed and submissive subject-population, rests with the Earth men. I have never been on Earth, for I was born on Eros. My mother died at my birth. I have never seen another human woman until to-day."

Nat looked at him, trying to follow what was in Axelson's mind.

"My father fled to Eros, a little planet seventeen miles in diameter, as we have found. He called it a heavenly paradise. It was his intention to found there a colony of those who were in rebellion against the tyrants of Earth.

"His followers journeyed to the Moon and brought back Moon women for wives. But there were no children of these unions. Later there were dissensions and civil war. Three-fourths of the colony died in battle with one another.

"I was a young man. I seized the reins of power. The survivors—these old men—were disillusioned and docile. I made myself absolute. I brought Moon men and women to Eros to serve us as slaves. But in a few years the last of my father's old compatriots will have died, and thus it was I conceived of conquering Earth and having men to obey me. For fifteen years I have been experimenting and constructing apparatus, with which I now have Earth at my mercy.

"But I shall need assistance, intelligent men who will obey me and aid me[168] in my plans. That is why I saved you and the other officers of your ether-lines. If you will join me, you shall have the highest post on Earth under me, Nathaniel Lee, and those others shall be under you."

xelson paused, and, loathing the man though he did, Nat was conscious of a feeling of pity for him that he could not control. He saw his lonely life on Eros, surrounded by those phantom humans of the past, and he understood his longing for Earth rule—he the planetary exile, the sole human being of all the planetary system outside Earth, perhaps, except for his dwindling company of aged men.

"To-day, Nathaniel Lee," Axelson went on, "my life was recast in a new mould when I saw the woman you have brought with you. I did not know before that women were beautiful to look on. I did not dream that creatures such as she existed. She must be mine, Nathaniel Lee.

"But that is immaterial. What is your answer to my offer?"

Nat was trying to think, though passion distorted the mental images as they arose in his brain. To Axelson it was evidently incomprehensible that there would be any objection to his taking Madge. Nat saw that he must temporize for Madge's sake.

"I'll have to consult my companions," he answered.

"Of course," answered Axelson. "That is reasonable. Tell them that unless they agree to join me it will be necessary for them to die. Do Earth men mind death? We hate it on Eros, and the Moon men hate it, too, though they have a queer legend that something in the shape of an invisible man raises from their ashes. My father told me that that superstition existed on Earth in his time, too. Go and talk to your companions, Nathaniel Lee."

The Black Caesar's voice was almost friendly. He clapped Nat on the shoulder again, and called the graybeard to conduct him back to his prison.

"Oh, Captain Lee, I'm so glad you're back!" exclaimed Madge. "We've been afraid for you. Is he such a terrible man, this Black Caesar?"

Nat sneered, then grinned malevolently. "Well, he's not exactly the old-fashioned idea of a Sunday-school teacher," he answered. Of course he could not tell the girl about Axelson's proposal.

he little group of prisoners stood on the upper deck of the black ship and watched the Moon men scurrying about the landing-stage as she hovered to her position.

Axelson's father had not erred when he had called the tiny planet, Eros, a heavenly paradise, for no other term could have described it.

They were in an atmosphere so similar to that of Earth that they could breathe with complete freedom, but there seemed to be a lightness and a vigor in their limbs that indicated that the air was supercharged with oxygen or ozone. The presence of this in large amounts was indicated by the intense blueness of the sky, across which fleecy clouds were drifting.

And in that sky what looked like threescore moons were circling with extraordinary swiftness. From thirty to forty full moons, of all sizes, from that of a sun to that of a brilliant planet, and riding black against the blue.

The sun, hardly smaller than when seen from Earth, shone in the zenith, and Earth and Mars hung in the east and north respectively, each like a blood-red sun.

The moons were some of the thousand other asteroids, weaving their lacy patterns in and out among each other. But, stupendous as the sight was, it was toward the terrestrial scene that the party turned their eyes as the black ship settled.

A sea of sapphire blue lapped sands of silver and broke into soft lines of foam. To the water's edge extended a lawn of brightest green, and behind[169] this an arm of the sea extended into what looked like a tropical forest. Most of the trees were palmlike, but towered to immense heights, their foliage swaying in a gentle breeze. There were apparently no elevations, and yet, so small was the little sphere that the ascending curve gave the illusion of distant heights, while the horizon, instead of seeming to rise, lay apparently perfectly flat, producing an extraordinary feeling of insecurity.

Near the water's edge a palatial mansion, built of hewn logs and of a single story, stood in a garden of brilliant flowers. Nearer, beyond the high landing-stage, were the great shipbuilding works, and near them an immense and slightly concave mirror flashed back the light of the sun.

"The death ray!" whispered Brent to Nat.

Axelson came up to the party as the ship settled down. "Welcome to Eros," he said cordially. "My father told me that in some Earth tongue that name meant 'love'."

ever, perhaps, was so strange a feast held as that with which Axelson entertained his guests that day. Dwarfish Moon men passed viands and a sort of palm wine in the great banquet-room, which singularly resembled one of those early twentieth century interiors shown in museums. Only the presence of a dozen of the aged guards, armed with ray-rods, lent a grimness to the scene.

Madge sat on Axelson's right, and Nat on his left. The girl's lightheartedness had left her; her face grew strained as Axelson's motives—which Nat had not dared disclose to her—disclosed themselves in his manner.

Once, when he laid his finger for a moment against her white throat, she started, and for a moment it seemed as if the gathering storm must break.

For Nat had talked with his men, and all had agreed that they would not turn traitor, though they intended to temporize as long as possible, in the hope of catching the Black Caesar unawares.

Then slowly a somber twilight began to fall, and Axelson rose.

"Let us walk in the gardens during the reign of Erebos," he said.

"Erebos?" asked Nat.

"The black world that overshadows us each sleeping period," answered Axelson.