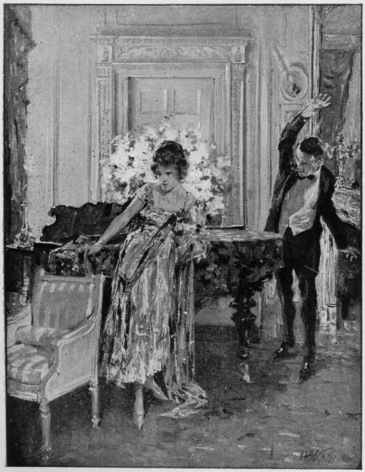

“I HATE IT AS YOU HATED THE BEASTS WHO SLEW YOUR FRIEND”

Title: The Crimson Tide: A Novel

Author: Robert W. Chambers

Illustrator: Arthur Ignatius Keller

Release date: September 1, 2009 [eBook #29880]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

“I HATE IT AS YOU HATED THE BEASTS WHO SLEW YOUR FRIEND”

THE CRIMSON TIDE

A NOVEL

By ROBERT W. CHAMBERS

Author of

“The Moonlit Way.”

“The Laughing Girl,”

“The Restless Sex,” etc.

WITH FRONTISPIECE BY

A. I. KELLER

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Published by arrangement with D. Appleton and Company

copyright, 1919, by

ROBERT W. CHAMBERS

Copyright, 1919, by

The International Magazine Company

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To

MARGARET ILLINGTON BOWES

AND

EDWARD J. BOWES

|

I I’d rather walk with Margaret, II An author’s such an ass, alas! III I’d rather walk with E. J. Bowes, IV If I could have my proper wish ENVOI Inspect my goods and choose a few R. W. C. |

FOREWORD

An American ambulance going south stopped on the snowy road; the driver, an American named Estridge, got out; his companion, a young woman in furs, remained in her seat.

Estridge, with the din of the barrage in his ears, went forward to show his papers to the soldiers who had stopped him on the snowy forest road.

His papers identified him and the young woman; and further they revealed the fact that the ambulance contained only a trunk and some hand luggage; and called upon all in authority to permit John Henry Estridge and Miss Palla Dumont to continue without hindrance the journey therein described.

The soldiers––Siberian riflemen––were satisfied and seemed friendly enough and rather curious to obtain a better look at this American girl, Miss Dumont, described in the papers submitted to them as “American companion to Marie, third daughter of Nicholas Romanoff, ex-Tzar.”

An officer came up, examined the papers, shrugged.

“Very well,” he said, “if authority is to be given this American lady to join the Romanoff family, now under detention, it is not my affair.”

But he, also, appeared to be perfectly good natured about the matter, accepting a cigarette from Estridge and glancing at the young woman in the ambulance as he lighted it.

“You know,” he remarked, “if it would interest you xii and the young lady, the Battalion of Death is over yonder in the birch woods.”

“The woman’s battalion?” asked Estridge.

“Yes. They make their début to-day. Would you like to see them? They’re going forward in a few minutes, I believe.”

Estridge nodded and walked back to the ambulance.

“The woman’s battalion is over in those birch woods, Miss Dumont. Would you care to walk over and see them before they leave for the front trenches?”

The girl in furs said very gravely:

“Yes, I wish to see women who are about to go into battle.”

She rose from the seat, laid a fur-gloved hand on his offered arm, and stepped down onto the snow.

“To serve,” she said, as they started together through the silver birches, following a trodden way, “is not alone the only happiness in life: it is the only reason for living.”

“I know you think so, Miss Dumont.”

“You also must believe so, who are here as a volunteer in Russia.”

“It’s a little more selfish with me. I’m a medical student; it’s a liberal education for me even to drive an ambulance.”

“There is only one profession nobler than that practised by the physician, who serves his fellow men,” she said in a low, dreamy voice.

“Which profession do you place first?”

“The profession of those who serve God alone.”

“The priesthood?”

“Yes. And the religious orders.”

“Nuns, too?” he demanded with the slightest hint of impatience in his pleasant voice.

The girl noticed it, looked up at him and smiled slightly.

“Had my dear Grand Duchess not asked for me, I should now he entering upon my novitiate among the Russian nuns.... And she, too, I think, had there been no revolution. She was quite ready a year ago. We talked it over. But the Empress would not permit it. And then came the trouble about the Deaconesses. That was a grave mistake–––”

She checked herself, then:

“I do not mean to criticise the Empress, you understand.”

“Poor lady,” he said, “such gentle criticism would seem praise to her now.”

They were walking through a pine belt, and in the shadows of that splendid growth the snow remained icy, so that they both slipped continually and she took his arm for security.

“I somehow had not thought of you, Miss Dumont, as so austerely inclined,” he said.

She smiled: “Because I’ve been a cheerful companion––even gay? Well, my gaiety made my heart sing with the prospect of seeing again my dearest friend––my closest spiritual companion––my darling little Grand Duchess.... So I have been, naturally enough, good company on our three days’ journey.”

He smiled: “I never suspected you of such extreme religious inclinations,” he insisted.

“Extreme?”

“Well, a novice–––” he hesitated. Then, “And you mean, ultimately, to take the black veil?”

“Of course. I shall take it some day yet.”

He turned and looked at her, and the man in him felt the pity of it as do all men when such fresh, xiv virginal youth as was Miss Dumont’s turns an enraptured face toward that cloister door which never again opens on those who enter.

Her arm rested warmly and confidently within his; the cold had made her cheeks very pink and had crisped the tendrils of her brown hair under the fur toque.

“If,” she said happily, “you have found in me a friend, it is because my heart is much too small for all the love I bear my fellow beings.”

“That’s a quaint thing to say,” he said.

“It’s really true. I care so deeply, so keenly, for my fellow beings whom God made, that there seemed only one way to express it––to give myself to God and pass my life in His service who made these fellow creatures all around me that I love.”

“I suppose,” he said, “that is one way of looking at it.”

“It seemed to be the only way for me. I came to it by stages.... And first, as a child, I was impressed by the loveliness of the world and I used to sit for hours thinking of the goodness of God. And then other phases came––socialistic cravings and settlement work––but you know that was not enough. My heart was too full to be satisfied. There was not enough outlet.”

“What did you do then?”

“I studied: I didn’t know what I wanted, what I needed. I seemed lost; I was obsessed with a desire to aid––to be of service. I thought that perhaps if I travelled and studied methods–––”

She looked straight ahead of her with a sad little reflective smile:

“I have passed by many strange places in the world.... And then I saw the little Grand Duchess at the xv Charity Bazaar.... We seemed to love each other at first glance.... She asked to have me for her companion.... They investigated.... And so I went to her.”

The girl’s face became sombre and she bent her dark eyes on the snow as they walked.

All the world was humming and throbbing with the thunder of the Russian guns. Flakes continually dropped from vibrating pine trees. A pale yellow haze veiled the sun.

Suddenly Miss Dumont lifted her head:

“If anything ever happens to part me from my friend,” she said, “I hope I shall die quickly.”

“Are you and she so devoted?” he asked gravely.

“Utterly. And if we can not some day take the vows together and enter the same order and the same convent, then the one who is free to do so is so pledged.... I do not think that the Empress will consent to the Grand Duchess Marie taking the veil.... And so, when she has no further need of me, I shall make my novitiate.... There are soldiers ahead, Mr. Estridge. Is it the woman’s battalion?”

He, also, had caught sight of them. He nodded.

“It is the Battalion of Death,” he said in a low voice. “Let’s see what they look like.”

The girl-soldiers stood about carelessly, there in the snow among the silver birches and pines. They looked like boys in overcoats and boots and tall wool caps, leaning at ease there on their heavy rifles. Some were only fifteen years of age. Some had been servants, some saleswomen, stenographers, telephone operators, dressmakers, workers in the fields, students at the university, dancers, laundresses. And a few had been born into the aristocracy.

They came, too, from all parts of the huge, sprawling Empire, these girl-soldiers of the Battalion of Death––and there were Cossack girls and gypsies among them––girls from Finland, Courland, from the Urals, from Moscow, from Siberia––from North, South, East, West.

There were Jewesses from the Pale and one Jewess from America in the ranks; there were Chinese girls, Poles, a child of fifteen from Trebizond, a Japanese girl, a French peasant lass; and there were Finns, too, and Scandinavians––all with clipped hair under the astrakhan caps––sturdy, well shaped, soldierly girls who handled their heavy rifles without effort and carried a regulation equipment as though it were a sheaf of flowers.

Their commanding officer was a woman of forty. She lounged in front of the battalion in the snow, consulting with half a dozen officers of a man’s regiment.

The colour guard stood grouped around the battalion colours, where its white and gold folds swayed languidly in the breeze, and clots of virgin snow fell upon it, shaken down from the pines by the cannonade.

Estridge gazed at them in silence. In his man’s mind one thought dominated––the immense pity of it all. And there was a dreadful fascination in looking at these girl soldiers, whose soft, warm flesh was so soon to be mangled by shrapnel and slashed by bayonets.

“Good heavens,” he muttered at last under his breath. “Was this necessary?”

“The men ran,” said Miss Dumont.

“It was the filthy boche propaganda that demoralised them,” rejoined Estridge. “I wonder––are women more level headed? Is propaganda wasted on xvii these girl soldiers? Are they really superior to the male of the species?”

“I think,” said Miss Dumont softly, “that their spiritual intelligence is deeper.”

“They see more clearly, morally?”

“I don’t know.... I think so sometimes.... We women, who are born capable of motherhood, seem to be fashioned also to realise Christ more clearly––and the holy mother who bore him.... I don’t know if that’s the reason––or if, truly, in us a little flame burns more constantly––the passion which instinctively flames more brightly toward things of the spirit than of the flesh.... I think it is true, Mr. Estridge, that, unless taught otherwise by men, women’s inclination is toward the spiritual, and the ardour of her passion aspires instinctively to a greater love until the lesser confuses and perplexes her with its clamorous importunity.”

“Woman’s love for man you call the lesser love?” he asked.

“Yes, it is, compared to love for God,” she said dreamily.

Some of the girl-soldiers in the Battalion of Death turned their heads to look at this young girl in furs, who had come among them on the arm of a Red Cross driver.

Estridge was aware of many bib brown eyes, many grey eyes, some blue ones fixed on him and on his companion in friendly or curious inquiry. They made him think of the large, innocent eyes of deer or channel cattle, for there was something both sweet and wild as well as honest in the gaze of these girl-soldiers.

One, a magnificent blond six-foot creature with the peaches-and-cream skin of Scandinavia and the clipped xviii gold hair of the northland, smiled at Miss Dumont, displaying a set of superb teeth.

“You have come to see us make our first charge?” she asked in Russian, her sea-blue eyes all a-sparkle.

Miss Dumont said “Yes,” very seriously, looking at the girl’s equipment, her blanket roll, gas-mask, boots and overcoat.

Estridge turned to another girl-soldier:

“And if you are made a prisoner?” he enquired in a low voice. “Have you women considered that?”

“Nechevo,” smiled the girl, who had been a Red Cross nurse, and who wore two decorations. She touched the red and black dashes of colour on her sleeve significantly, then loosened her tunic and drew out a tiny bag of chamois. “We all carry poison,” she said smilingly. “We know the boche well enough to take that precaution.”

Another girl nodded confirmation. They were perfectly cheerful about it. Several others drew near and showed their little bags of poison slung around their necks inside their blouses. Many of them wore holy relics and medals also.

Miss Dumont took Estridge’s arm again and looked over at the big blond girl-soldier, who also had been smilingly regarding her, and who now stepped forward to meet them halfway.

“When do you march to the first trenches?” asked Miss Dumont gravely.

“Oh,” said the blond goddess, “so you are English?” And she added in English: “I am Swedish. You have arrived just in time. I t’ink we go forward immediately.”

“God go with you, for Russia,” said Miss Dumont in a clear, controlled voice.

But Estridge saw that her dark eyes were suddenly brilliant with tears. The big blond girl-soldier saw it, too, and her splendid blue eyes widened. Then, somehow, she had stepped forward and taken Miss Dumont in her strong arms; and, holding her, smiled and gazed intently at her.

“You must not grieve for us,” she said. “We are not afraid. We are happy to go.”

“I know,” said Palla Dumont; and took the girl-soldier’s hands in hers. “What is your name?” she asked.

“Ilse Westgard. And yours?”

“Palla Dumont.”

“English? No?”

“American.”

“Ah! One of our dear Americans! Well, then, you shall tell your countrymen that you have seen many women of many lands fighting rifle in hand, so that the boche shall not strangle freedom in Russia. Will you tell them, Palla?”

“If I ever return.”

“You shall return. I, also, shall go to America. I shall seek for you there, pretty comrade. We shall become friends. Already I love you very dearly.”

She kissed Palla Dumont on both cheeks, holding her hands tightly.

“Tell me,” she said, “why you are in Russia, and where you are now journeying?”

Palla looked at her steadily: “I am the American companion to the Grand Duchess Marie; and I am journeying to the village where the Imperial family is detained, because she has obtained permission for me to rejoin her.”

There was a short silence; the blue eyes of the xx Swedish girl had become frosty as two midwinter stars. Suddenly they glimmered warm again as twin violets:

“Kharasho!” she said smiling. “And do you love your little comrade duchess?”

“Next only to God.”

“That is very beautiful, Palla. She is a child to be enlightened. Teach her the greater truth.”

“She has learned it, Ilse.”

“She?”

“Yes. And, if God wills it, she, and I also, take the vows some day.”

“The veil!”

“Yes.”

“You! A nun!”

“If God accepts me.”

The Swedish girl-soldier stood gazing upon her as though fascinated, crushing Palla’s slim hands between her own.

Presently she shook her head with a wearied smile:

“That,” she said, “is one thing I can not understand––the veil. No. I can understand this–––” turning her head and glancing proudly around her at her girl comrades. “I can comprehend this thing that I am doing. But not what you wish to do, Palla. Not such service as you offer.”

“I wish to serve the source of all good. My heart is too full to be satisfied by serving mankind alone.”

The girl-soldier shook her head: “I try to understand. I can not. I am sorry, because I love you.”

“I love you, Ilse. I love my fellows.”

After another silence:

“You go to the imperial family?” demanded Ilse abruptly.

“Yes.”

“I wish to see you again. I shall try.”

The battalion marched a few moments later.

It was rather a bad business. They went over the top with a cheer. Fifty answered roll call that night.

However, the hun had learned one thing––that women soldiers were inferior to none.

Russia learned it, too. Everywhere battalions were raised, uniformed, armed, equipped, drilled. In the streets of cities the girl-soldiers became familiar sights: nobody any longer turned to stare at them. There were several dozen girls in the officers’ school, trying for commissions. In all the larger cities there were infantry battalions of girls, Cossack troops, machine gun units, signallers; they had a medical corps and transport service.

But never but once again did they go into action. And their last stand was made facing their own people, the brain-crazed Reds.

And after that the Battalion of Death became only a name; and the girl-soldiers bewildered fugitives, hunted down by the traitors who had sold out to the Germans at Brest-Litovsk. xxiii

PREFACE

A door opened; the rush of foggy air set the flames of the altar candles blowing wildly. There came the clank of armed men.

Then, in the dim light of the chapel, a novice sprang to her feet, brushing the white veil from her pallid young face.

At that the ex-Empress, still kneeling, lifted her head from her devotions and calmly turned it, looking around over her right shoulder.

The file of Red infantry advanced, shuffling slowly forward as though feeling their way through the candle-lit dusk across the stone floor. Their accoutrements clattered and clinked in the intense stillness. A slovenly officer, switching a thin, naked sword in his ungloved fist, led them. Another officer, carrying a sabre and marching in the rear, halted to slam and lock the heavy chapel door; then he ran forward to rejoin his men, while the chapel still reverberated with the echoes of the clanging door.

A chair or two fell, pushed aside by the leading soldiers and hastily kicked out of the way as the others advanced more swiftly now. For there seemed to be some haste. These men were plainly in a hurry, whatever their business there might be.

The Tzesarevitch, kneeling beside his mother, got up from his knees with visible difficulty. The Empress also rose, leisurely, supporting herself by one hand resting on the prie-dieu.

Then several young girls, who had been kneeling behind her at their devotions, stood up and turned to stare at the oncoming armed men, now surrounding them.

The officer carrying the naked sword, and reeking with fumes of brandy, counted these women in a loud, thick voice.

“That’s right,” he said. “You’re all present––one! two! three! four! five! six!––the whole accursed brood!” pointing waveringly with his sword from one to another.

Then he laughed stupidly, leering out of his inflamed eyes at the five women who all wore the garbs of the Sisters of Mercy, their white coiffes and tabliers contrasting sharply with the sombre habits of the Russian nuns who had gathered in the candle-lit dusk behind them.

“What do you wish?” demanded the ex-Empress in a fairly steady voice.

“Answer to your names!” retorted the officer brutally. The other officer came up and began to fumble for a note book in the breast of his dirty tunic. When he found it he licked the lead of his pencil and squinted at the ex-Empress out of drunken eyes.

“Alexandra Feodorovna!” he barked in her face. “If you’re here, say so!”

She remained calm, mute, cold as ice.

A soldier behind her suddenly began to shout:

“That’s the German woman. That’s the friend of the Staretz Novykh! That’s Sascha! Now we’ve got her, the thing to do is to shoot her–––”

“Mark her present,” interrupted the officer in command. “No ceremony, now. Mark the cub Romanoff present. Mark ’em all––Olga, Tatyana, Marie, xxv Anastasia!––no matter which is which––they’re all Romanoffs–––”

But the same soldier who had interrupted before bawled out again: “They’re not Romanoffs! There are no German Romanoffs. There are no Romanoffs in Russia since a hundred and fifty years–––”

The little Tzesarevitch, Alexis, red with anger, stepped forward to confront the man, his frail hands fiercely clenched. The officer in command struck him brutally across the breast with the flat of his sword, shoved him aside, strode toward the low door of the chapel crypt and jerked it open.

“Line them up!” he bawled. “We’ll settle this Romanoff dispute once for all! Shove them into line! Hurry up, there!”

But there seemed to be some confusion between the nuns and the soldiers, as the latter attempted to separate the ex-Empress and the young Grand Duchesses from the sisters.

“What’s all that trouble about!” cried the officer commanding. “Drive back those nuns, I tell you! They’re Germans, too! They’re Sascha’s new Deaconesses! Kick ’em out of the way!”

Then the novice, who had cried out in fear when the Red infantry first entered the chapel, forced her way out into the file formed by the Empress and her daughters.

“There’s a frightful mistake!” she cried, laying one hand on the arm of a young girl dressed, like the others, as a Sister of Mercy. “This woman is Miss Dumont, my American companion! Release her! I am the Grand Duchess Marie!”

The girl, whose arm had been seized, looked at the young novice over her shoulder in a dazed way; then, xxvi suddenly her lovely face flushed scarlet; tears sprang to her eyes; and she said to the infuriated officer:

“It is not true, Captain! I am the Grand Duchess Marie. She is trying to save me!”

“What the devil is all this row!” roared the officer, who now came tramping and storming among the prisoners, switching his sword to and fro with ferocious impatience.

The little Sister of Mercy, frightened but resolute, pointed at the novice, who still clutched her by the arm: “It is not true what she tells you,” she repeated. “I am the Grand Duchess Marie, and this novice is my American companion, Miss Dumont, who loves me devotedly and who now attempts to sacrifice herself in my place–––”

“I am the Grand Duchess Marie!” interrupted the novice excitedly. “This young girl dressed like a Sister of Mercy is only my American companion–––”

“Damnation!” yelled the officer. “I’ll take you both, then!” But the girl in the Sister of Mercy’s garb turned and violently pushed the novice from her so that she stumbled and fell on her knees among the nuns.

Then, confronting the officer: “You Bolshevik dog,” she said contemptuously, “don’t you even know the daughter of your dead Emperor when you see her!” And she struck him across the face with her prayer book.

As he recoiled from the blow a soldier shouted: “There’s your proof! There’s your insolent Romanoff for you! To hell with the whole litter! Shoot them!” Instantly a savage roar from the Reds filled that dim place; a soldier violently pushed the young Tzesarevitch into the file behind the Empress and held him xxvii there; the Grand Duchess Olga was flung bodily after him; the other children, in their hospital dresses, were shoved brutally toward their places, menaced by butt and bayonet.

“March!” bawled the officer in command.

But now, among the dark-garbed nuns, a slender white figure was struggling frantically to free herself:

“You red dogs!” she cried in an agonised voice. “Let that English woman go! It is I you want! Do you hear! I mock at you! I mock at your resolution! Boje Tzaria Khrani! Down with the Bolsheviki!”

A soldier turned and fired at her; the bullet smashed an ikon above her head.

“I am the Grand Duchess Marie!” she sobbed. “I demand my place! I demand my fate! Let that American girl go! Do you hear what I say? Red beasts! Red beasts! I am the Grand Duchess!–––”

The officer who closed the file turned savagely and shook his heavy cavalry sabre at her: “I’ll come back in a moment and cut your throat for you!” he yelled.

Then, in the file, and just as the last bayonets were vanishing through the crypt door, one of the young girls turned and kissed her hand to the sobbing novice––a pretty gesture, tender, gay, not tragic, even almost mischievously triumphant.

It was the adieu of the Grand Duchess Tatyana to the living world––her last glimpse of it through the flames of the altar candles gilding the dead Christ on his jewelled cross––the image of that Christ she was so soon to gaze upon when those lovely, mischievous young eyes of hers unclosed in Paradise....

The door of the crypt slammed. A terrible silence reigned in the chapel.

Then the novice uttered a cry, caught the foot of the cross with desperate hands, hung there convulsively.

To her the Mother Superior turned, weeping. But at her touch the girl, crazed with grief, lifted both hands and tore from her own face the veil of her novitiate just begun;––tore her white garments from her shoulders, crying out in a strangled voice that if a Christian God let such things happen then He was no God of hers––that she would never enter His service––that the Lord Christ was no bridegroom for her; and, her novitiate was ended––ended together with every vow of chastity, of humility, of poverty, of even common humanity which she had ever hoped to take.

The girl was now utterly beside herself; at one moment flaming and storming with fury among the terrified, huddling nuns; the next instant weeping, stamping her felt-shod foot in ungovernable revolt at this horror which any God in any heaven could permit.

And again and again she called out on Christ to stop this thing and prove Himself a real God to a pagan world that mocked Him.

Dishevelled, her rent veil in tatters on her naked shoulders, she sprang across the chapel to the crypt door, shook it, tore at it, seized chair after chair and shattered them to splinters against the solid panels of oak and iron.

Then, suddenly motionless, she crouched and listened.

“Oh, Mother of God!” she panted, “intervene now––now!––or never!”

The muffled rattle of a rather ragged volley answered her prayer.

Outside the convent a sentry––a Kronstadt sailor––stood. He also heard the underground racket. He nodded contentedly to himself. Other shots followed––pistol shots––singly.

After a few moments a wisp of smoke from the crypt crept lazily out of the low oubliettes. The day was grey and misty; rain threatened; and the rifle smoke clung low to the withered grass, scarcely lifting.

The sentry lighted a third cigarette, one eye on the barred oubliettes, from which the smoke crawled and spread out over the grass.

After a while a sweating face appeared behind the bars and a half-stifled voice demanded why there was any delay about fetching quick-lime. And, still clinging to the bars with bloody fingers, he added:

“There’s a damned novice in the chapel. I promised to cut her throat for her. Go in and get her and bring her down here.”

The novice was nowhere to be found.

They searched the convent thoroughly; they went out into the garden and beat the shrubbery, kicking through bushes and saplings, their cocked rifles poised for a snap shot.

Peasants, gathering there more thickly now, watched them stupidly; the throng increased in the convent grounds. Some Bolshevik soldiers pushed through the rapidly growing crowd and ran toward a birch wood east of the convent. Beyond the silvery fringe of birches, larger trees of a heavy, hard-wood forest loomed. Among these splendid trees a number of beeches were being felled on both sides of the road.

“Did you see a White Nun run this way?” demanded xxx the soldiers of the wood-cutters. The latter shook their heads:

“Nothing has passed,” they said seriously, “except some Ural Cossacks riding north like lost souls in a hurricane.”

An officer of the Red battalion, who had now hastened up with pistol swinging, flew into a frightful rage:

“Cossacks!” he bellowed. “You cowardly dogs, what do you mean by letting Kaledines’ horsemen gallop over you like that––you with your saws and axes––twenty lusty comrades to block the road and pull the Imperialists off their horses! Shame! For all I know you’ve let a Romanoff escape alive into the world! That’s probably what you’ve done, you greasy louts!”

The wood-cutters gaped stupidly; the Bolshevik officer cursed them again and gesticulated with his pistol. Other soldiers of the Red battalion ran up. One nudged the officer’s elbow without saluting:

“That other prisoner can’t be found–––”

“What! That Swedish girl!” yelled the officer.

Several soldiers began speaking excitedly:

“While we were in the cellar, they say she ran away–––”

“Yes, Captain, while we were about that business in the crypt, Kaledines’ horsemen rode up outside–––”

“Who saw them?” demanded the officer hoarsely. “God curse you, who saw them?”

Some peasants had now come up. One of them began:

“Your honour, I saw Prince Kaledines’ riders–––”

“Whose!”

“The Hetman’s–––”

“Your honour! Prince Kaledines! The Hetman! xxxi Damnation! Who do you think you are! Who do you think I am!” burst out the Red officer in a fury. “Get out of my way!–––” He pushed the peasants right and left and strode away toward the convent. His soldiers began to straggle after him. One of them winked at the wood-cutters with his tongue in his cheek, and slung the rifle he carried over his right shoulder en bandoulière, muzzle downward.

“The Tavarish is in a temper,” he said with a jerk of his thumb toward the officer. “We arrested that Swedish girl in the uniform of the woman’s battalion. One shoots that breed on sight, you know. But we were in such a hurry to finish with the Romanoffs–––” He shrugged: “You see, comrades, we should have taken her into the crypt and shot her along with the Romanoffs. That’s how one loses these birds––they’re off if you turn your back to light a cigarette in the wind.”

One of the wood-cutters said: “Among Kaledines’ horsemen were two women. One was crop-headed like a boy, and half naked.”

“A White Nun?”

“God knows. She had some white rags hanging to her body, and dark hair clipped like a boy’s.”

“That––was––she!” said the soldier with slow conviction. He turned and looked down the long perspective of the forest road. Only a raven stalked there all alone over the fallen leaves.

“Certainly,” he said, “that was our White Nun. The Cossacks took her with them. They must have ridden fast, the horsemen of Kaledines.”

“Like a swift storm. Like the souls of the damned,” replied a peasant.

The soldier shrugged: “If there’s still a Romanoff xxxii loose in the world, God save the world!... And that big heifer of a Swedish wench!––she was a bad one, I tell you!––Took six of us to catch her and ten to hold her by her ten fingers and toes! Hey! God bless me, but she stands six feet and is made of steel cased in silk––all white, smooth and iron-hard––the blond young snow-tiger that she is!––the yellow-haired, six-foot, slippery beastess! God bless me––God bless me!” he muttered, staring down the wood-road to its vanishing point against the grey horizon.

Then he hitched his slung rifle to a more comfortable position, turned, gazed at the convent across the fields, which his distant comrades were now approaching.

“A German nest,” he said aloud to himself, “full of their damned Deaconesses! Hey! I’ll be going along to see what’s to be done with them, also!”

He nodded to the wood-cutters:

“Vermin-killing time,” he remarked cheerily. “After the dirty work is done, peace, land enough for everybody, ease and plenty and a full glass always at one’s elbows––eh, comrades?”

He strode away across the fields.

It had begun to snow.

ARGUMENT

The Cossacks sang as they rode:

|

I “Life is against us |

They were from the Urals: they sat their shaggy little grey horses, lance in hand, stirrup deep in saddle paraphernalia––kit-bags, tents, blankets, trusses of straw, a dead fowl or two or a quarter of beef. And from every saddle dangled a balalaika and the terrible Cossack whip.

The steel of their lances flashed red in the setting sun; snow whirled before the wind in blinding pinkish clouds, powdering horse and rider from head to heel.

Again one rider unslung his balalaika, struck it, looking skyward as he rode:

They rode into a forest, slowly, filing among the silver birches, then trotting out amid the pines.

The Swedish girl towered in her saddle, dwarfing the shaggy pony. She wore her grey wool cap, overcoat, and boots. Pistols bulged in the saddle holsters; sacks of grain and a bag of camp tins lay across pommel and cantle.

Beside her rode the novice, swathed to the eyes in a sheepskin greatcoat, and a fur cap sheltering her shorn head.

Her lethargy––a week’s reaction from the horrors of the convent––had vanished; and a feverish, restless alertness had taken its place.

Nothing of the still, white novice was visible now in her brilliant eyes and flushed cheeks.

Her tragic silence had given place to an unnatural loquacity; her grief to easily aroused mirth; and the dark sorrow in her haunted eyes was gone, and they grew brown and sunny and vivacious.

She talked freely with her comrade, Ilse Westgard; she exchanged gossip and banter with the Cossacks, argued with them, laughed with them, sang with them.

At night she slept in her sheepskin in Ilse Westgard’s vigorous arms; morning, noon and evening she filled the samovar with snow beside Cossack fires, or in the rare cantonments afforded in wretched villages, where whiskered and filthy mujiks cringed to the Cossacks, whispering to one another: “There is no end xxxv to death; there is no end to the fighting and the dying, God bless us all. There is no end.”

In the glare of great fires in muddy streets she stood, swathed in her greatcoat, her cap pushed back, looking like some beautiful, impudent boy, while the Cossacks sang “Lada oy Lada!”––and let their slanting eyes wander sideways toward her, till her frank laughter set the singers grinning and the gusli was laid aside.

And once, after a swift gallop to cross a railroad and an exchange of shots with the Red guards at long range, the sotnia of the Wild Division rode at evening into a little hamlet of one short, miserable street, and shouted for a fire that could be seen as far as Moscow.

That night they discovered vodka––not much––enough to set them singing first, then dancing. The troopers danced together in the fire-glare––clumsily, in their boots, with interims of the pas seul savouring of the capers of those ancient Mongol horsemen in the Hezars of Genghis Khan.

But no dancing, no singing, no clumsy capers were enough to satisfy these riders of the Wild Division, now made boisterous by vodka and horse-meat. Gossip crackled in every group; jests flew; they shouted at the peasants; they roared at their own jokes.

“Comrade novice!––Pretty boy with a shorn head!” they bawled. “Harangue us once more on law and love.”

She stood with legs apart and thumbs hooked in her belt, laughing at them across the fire. And all around crowded the wretched mujiks, peering at her through shaggy hair, out of little wolfish eyes.

A Cossack shouted: “My law first! Land for all! That is what we have, we Cossacks! Land for the xxxvi people, one and all––land for the mujik; land for the bourgeois; land for the aristocrat! That law solves all, clears all questions, satisfies all. It is the Law of Peace!”

A Cossack shoved a soldier-deserter forward into the firelight. He wore a patch of red on his sleeve.

“Answer, comrade! Is that the true law? Or have you and your comrades made a better one in Petrograd?”

The deserter, a little frightened, tried to grin: “A good law is, kill all generals,” he said huskily. “Afterward we shall have peace.”

A roar of laughter greeted him; these dark, thickset Cossacks with slanting eyes were from the Urals. What did they care how many generals were killed? Besides, their hetman had already killed himself.

Their officer moved out into the firelight––a reckless rider but a dull brain––and stood lashing at his snow-crusted boots with the silver-mounted quirt.

“Like gendarmes,” he said, “we Cossacks are forever doing the dirty work of other people. Why? It begins to sicken me. Why are we forever executing the law! What law? Who made it? The Tzar. And he is dead, and what is the good of the law he made?

“Why should free Cossacks be policemen any more when there is no law?

“We played gendarme for the Monarchists. We answered the distress call of the Cadets and the bourgeoisie! Where are they? Where is the law they made?”

He stood switching his dirty boots and swinging his heavy head right and left with the stupid, lowering menace of a bull.

“Then came the Mensheviki with their law,” he bellowed xxxvii suddenly. “Again we became policemen, galloping to their whistle. Where are they? Where is their law?”

He spat on the snow, twirled his quirt.

“There is only one law to govern the land,” he roared. “It is the law of hands off and mind your business! It’s a good law.”

“A good law for those who already have something,” cried a high, thin voice from the throng of peasants.

The Cossacks, who all possessed their portion of land, yelled with laughter. One of them called out to the Swedish girl for her opinion, and the fair young giantess strode gracefully out into the fire-ring, her cap in her hand and the thick blond ringlets shining like gold on her beautiful head.

“Listen! Listen to this soldier of the Death Battalion!” shouted the Cossacks in great glee. “She will tell us what the law should be!”

She laughed: “We fought for it––we women soldiers,” she said. “And the law we fought for was made when the first tyrant fell.

“This is the law: Freedom of mind; liberty of choice; an equal chance for all; no violence; only orderly debate to determine the will of the land.”

A Cossack said loudly: “Da volna! Those who have nothing would take, then, from those who have!”

“I think not!” cried another,“––not in the Urals!”

Thunderous laughter from their comrades and cries of, “Palla! Let us hear our pretty boy, who has made for the whole world a law.”

Palla Dumont, her slender hands thrust deep in her great coat sleeves, and standing like a nun lost in mystic revery, looked up with gay audacity––not like xxxviii a nun at all, now, save for the virginal allure that seemed a part of the girl.

“There is only one law, Tavarishi,” she said, turning slightly from her hips as she spoke, to include those behind her in the circle: “and that law was not made by man. That law was born, already made, when the first man was born. It has never changed. It comprehends everything; includes everything and everybody; it solves all perplexity, clears all doubts, decides all questions.

“It is a living law; it exists; it is the key to every problem; and it is all ready for you.”

The girl’s face had altered; the half mischievous audacity in defiance of her situation––the gay, impudent confidence in herself and in these wild comrades of hers, had given place to something more serious, more ardent––the youthful intensity that smiles through the flaming enchantment of suddenly discovered knowledge.

“It is the oldest of all laws,” she said. “It was born perfect. It is yours if you accept it. And this law is the Law of Love.”

A peasant muttered: “One gives where one loves.”

The girl turned swiftly: “That is the soul of the Law!” she cried, “to give! Is there any other happiness, Tavarishi? Is there any other peace? Is there need of any other law?

“I tell you that the Law of Love slays greed! And when greed dies, war dies. And hunger, and misery die, too!

“Of what use is any government and its lesser laws and customs, unless it is itself governed by that paramount Law?

“Of what avail are your religions, your churches, xxxix your priests, your saints, relics, ikons––all your candles and observances––unless dominated by that Law?

“Of what use is your God unless that Law of Love also governs Him?”

She stood gazing at the firelit faces, the virginal half-smile on her lips.

A peasant broke the silence: “Is she a new saint, then?” he said distinctly.

A Cossack nodded to her, grinning respectfully:

“We always like your sermons, little novice,” he said. And, to the others: “Nobody wishes to deny what she says is quite true”––he scratched his head, still grinning––“only––while there are Kurds in the world–––”

“And Bolsheviki!” shouted another.

“True! And Turks! God bless us, Tavarishi,” he added with a wry face, “it takes a stronger stomach to love these beasts than is mine–––”

In the sudden shout of laughter the girl, Palla, looked around at her comrade, Ilse.

“Until each accepts the Law of Love,” said the Swedish girl-soldier, laughing, “it can not be a law.”

“I have accepted it,” said Palla gaily; but her childishly lovely mouth was working, and she clenched her hands in her sleeves to control the tremor.

Silent, the smile still stamped on her tremulous lips, she stood for a few moments, fighting back the deep emotions enveloping her in surging fire––the same ardent and mystic emotions which once had consumed her at the altar’s foot, where she had knelt, a novice, dreaming of beatitudes ineffable.

If that vision, for her, was ended––its substance but the shadow of a dream––the passion that created it, the fire that purified it, the ardent heart that needed xl love––love sacred, love unalloyed––needed love still, burned for it, yearning to give.

As she lifted her head and looked around her with dark eyes still a little dazed, there was a sudden commotion among the mujiks; a Cossack called out something in a sharp voice; their officer walked hastily out into the darkness; a shadowy rider spurred ahead of him.

Suddenly a far voice shouted: “Who goes there! Stoi!”

Then red flashes came out of the night; Cossacks ran for their horses; Ilse appeared with Palla’s pony as well as her own, and halted to listen, the fearless smile playing over her face.

“Mount!” cried many voices at once. “The Reds!”

Palla flung herself astride her saddle; Ilse galloped beside her, freeing her pistols; everywhere in the starlight the riders of the Wild Division came galloping, loosening their long lances as they checked their horses in close formation.

Then, with scarcely a sound in the unbroken snow, they filed away eastward at a gentle trot, under the pale lustre of the stars. 1

On the 7th of November, 1917, the Premier of the Russian Revolutionary Government was a hunted fugitive, his ministers in prison, his troops scattered or dead. Three weeks later, the irresponsible Reds had begun their shameful career of treachery, counselled by a pallid, black-eyed man with a muzzle like a mouse––one L. D. Bronstein, called Trotzky; and by two others––one a bald, smooth-shaven, rotund little man with an expression that made men hesitate, and features not trusted by animals and children.

The Red Parliament called him Vladimir Ulianov, and that’s what he called himself. He had proved to be reticent, secretive, deceitful, diligent, and utterly unhuman. His lower lip was shaped as though something dripped from it. Blood, perhaps. His eyes were brown and not entirely unattractive. But God makes the eyes; the mouth is fashioned by one’s self.

The world knew him as Lenine.

The third man squinted. He wore a patch of sparse cat-hairs on his chin and upper lip.

His head was too big; his legs too short, but they were always in a hurry, always in motion. He had a 2 persuasive and ardent tongue, and practically no mind. The few ideas he possessed inclined him to violence––always the substitute for reason in this sort of agitator. It was this ever latent violence that proved persuasive. His name was Krylenko. His smile was a grin.

These three men betrayed Christ on March 3d, 1918.

On the Finland Road, outside of Petrograd, the Red ragamuffins held a perpetual carmagnole, and all fugitives danced to their piping, and many paid for the music.

But though White Guards and Red now operated in respectively hostile gangs everywhere throughout the land, and the treacherous hun armies were now in full tide of their Baltic invasion, there still remained ways and means of escape––inconspicuous highways and unguarded roads still open that led out of that white hell to the icy but friendly seas clashing against the northward coasts.

Diplomats were inelegantly “beating it.” A kindly but futile Ambassador shook the snow of Petrograd from his galoshes and solemnly and laboriously vanished. Mixed bands of attachés, consular personnel, casuals, emissaries, newspaper men, and mission specialists scattered into unfeigned flight toward those several and distant sections of “God’s Country,” divided among civilised nations and lying far away somewhere in the outer sunshine.

Sometimes White Guards caught these fugitives; sometimes Red Guards; and sometimes the hun nabbed them on the general hunnish principle that whatever is running away is fair game for a pot shot.

Even the American Red Cross was “suspect”––treachery being alleged in its relations with Roumania; 3 and hun and Bolshevik became very troublesome––so troublesome, in fact, that Estridge, for example, was having an impossible time of it, arrested every few days, wriggling out of it, only to be collared again and detained.

Sometimes they questioned him concerning gun-running into Roumania; sometimes in regard to his part in conducting the American girl, Miss Dumont, to the convent where the imperial family had been detained.

That the de facto government had requested him to undertake this mission and to employ an American Red Cross ambulance in the affair seemed to make no difference.

He continued to be dogged, spied on, arrested, detained, badgered, until one evening, leaving the Smolny, he encountered an American––a slim, short man who smiled amiably upon him through his glasses, removed a cigar from his lips, and asked Estridge what was the nature of his evident and visible trouble.

So they walked back to the hotel together and settled on a course of action during the long walk. What this friend in need did and how he did it, Estridge never learned; but that same evening he was instructed to pack up, take a train, and descend at a certain station a few hours later.

Estridge followed instructions, encountered no interference, got off at the station designated, and waited there all day, drinking boiling tea.

Toward evening a train from Petrograd stopped at the station, and from the open door of a compartment Estridge saw his chance acquaintance of the previous day making signs to him to get aboard.

Nobody interfered. They had a long, cold, unpleasant night journey, wedged in between two soldiers 4 wearing arm-bands, who glowered at a Russian general officer opposite, and continued to mutter to each other about imperialists, bourgeoisie, and cadets.

At every stop they were inspected by lantern light, their papers examined, and sometimes their luggage opened. But these examinations seemed to be perfunctory, and nobody was detained.

In the grey of morning the train stopped and some soldiers with red arm-bands looked in and insulted the general officer, but offered no violence. The officer gave them a stony glance and closed his cold, puffy eyes in disdain. He was blond and looked like a German.

At the next stop Estridge received a careless nod from his chance acquaintance, gathered up his luggage and descended to the frosty platform.

Nobody bothered to open their bags; their papers were merely glanced at. They had some steaming tea and some sour bread together.

A little later a large sleigh drove up behind the station; their light baggage was stowed aboard, they climbed in under the furs.

“Now,” remarked his calm companion to Estridge, “we’re all right if the Reds, the Whites and the boches don’t shoot us up.”

“What are the chances?” inquired Estridge.

“Excellent, excellent,” said his companion cheerily, “I should say we have about one chance in ten to get out of this alive. I’ll take either end––ten to one we don’t get out––ten to two we’re shot up and not killed––ten to three we are arrested but not killed––one to ten we pull through with whole skins.”

Estridge smiled. They remained silent, probably preoccupied with the hazards of their respective fortunes. It grew colder toward noon.

The young man seated beside Estridge in the sleigh smoked continually.

He was attached to one of the American missions sent into Russia by an optimistic administration––a mission, as a whole, foredoomed to political failure.

In every detail, too, it had already failed, excepting only in that particular part played by this young man, whose name was Brisson.

He, however, had gone about his occult business in a most amazing manner––the manner of a Yankee who knows what he wants and what his country ought to want if it knew enough to know it wanted it.

He was the last American to leave Petrograd: he had taken his time; he left only when he was quite ready to leave.

And this was the man, now seated beside Estridge, who had coolly and cleverly taken his sporting chance in remaining till the eleventh hour and the fifty-ninth minute in the service of his country. Then, as the twelfth hour began to strike, he bluffed his way through.

During the first two or three days of sleigh travel, Brisson learned all he desired to know about Estridge, and Estridge learned almost nothing about Brisson except that he possessed a most unholy genius for wriggling out of trouble.

Nothing, nobody, seemed able to block this young man’s progress. He bluffed his way through White Guards and Red; he squirmed affably out of the clutches of wandering Cossacks; he jollied officials of 6 all shades of political opinion; but he always continued his journey from one étape to the next. Also, he was continually lighting one large cigar after another. Buttoned snugly into his New York-made arctic clothing, and far more comfortable at thirty below zero than was Estridge in Russian costume, he smoked comfortably in the teeth of the icy gale or conversed soundly on any topic chosen. And the range was wide.

But about himself and his mission in Russia he never conversed except to remark, once, that he could buy better Russian clothing in New York than in Petrograd.

Indeed, his only concession to the customs of the country was in the fur cap he wore. But it was the galoshes of Manhattan that saved his feet from freezing. He had two pair and gave one to Estridge.

During several hundreds of miles in sleighs, Brisson’s constant regret was the absence of ferocious wolves. He desired to enjoy the whole show as depicted by the geographies. He complained to Estridge quite seriously concerning the lack of enterprise among the wolves.

But there seemed to be no wolves in Russia sufficiently polite to oblige him; so he comforted himself by patting his stomach where, sewed inside his outer underclothing, reposed documents destined to electrify the civilised world with proof infernal of the treachery of those three men who belong in history and in hell to the fraternity which includes Benedict Arnold and Judas.

One late afternoon, while smoking his large cigar and hopefully inspecting the neighbouring forest for wolves, this able young man beheld a sotnia of Ural 7 Cossacks galloping across the snow toward the flying sleigh, where he and Estridge sat so snugly ensconced.

There was, of course, only one thing to do, and that was to halt. Kaledines had blown his brains out, but his riders rode as swiftly as ever. So the sleigh stopped.

And now these matchless horsemen of the Wild Division came galloping up around the sleigh. Brilliant little slanting eyes glittered under shaggy head-gear; broad, thick-lipped mouths split into grins at sight of the two little American flags fluttering so gaily on the sleigh.

Then two booted and furred riders climbed out of their saddles, and, under their sheepskin caps, Brisson saw the delicate features of two young women, one a big, superb, blue-eyed girl; the other slim, dark-eyed, and ivory-pale.

The latter said in English: “Could you help us? We saw the flags on your sleigh. We are trying to leave the country. I am American. My name is Palla Dumont. My friend is Swedish and her name is Ilse Westgard.”

“Get in, any way,” said Brisson briskly. “We can’t be in a worse mess than we are. I imagine it’s the same case with you. So if we’re all going to smash, it’s pleasanter, I think, to go together.”

At that the Swedish girl laughed and aided her companion to enter the sleigh.

“Good-bye!” she called in her clear, gay voice to the Cossacks. “When we come back again we shall ride with you from Vladivostok to Moscow and never see an enemy!”

When the young women were comfortably ensconced in the sleigh, the riders of the Wild Division crowded 8 their horses around them and shook hands with them English fashion.

“When you come back,” they cried, “you shall find us riding through Petrograd behind Korniloff!” And to Brisson and Estridge, in a friendly manner: “Come also, comrades. We will show you a monument made out of heads and higher than the Kremlin. That would be a funny joke and worth coming back to see.”

Brisson said pleasantly that such an exquisite jest would be well worth their return to Russia.

Everybody seemed pleased; the Cossacks wheeled their shaggy mounts and trotted away into the woods, singing. The sleigh drove on.

“This is very jolly,” said Brisson cheerfully. “Wherever we’re bound for, now, we’ll all go together.”

“Is not America the destination of your long journey?” inquired the big, blue-eyed girl.

Brisson chuckled: “Yes,” he said, “but bullets sometimes shorten routes and alter destinations. I think you ought to know the worst.”

“If that’s the worst, it’s nothing to frighten one,” said the Swedish girl. And her crystalline laughter filled the icy air.

She put one persuasive arm around her slender, dark-eyed comrade:

“To meet God unexpectedly is nothing to scare one, is it, Palla?” she urged coaxingly.

The other reddened and her eyes flashed: “What God do you mean?” she retorted. “If I have anything to say about my destination after death I shall go wherever love is. And it does not dwell with the God or in the Heaven that we have been taught to desire and hope for.”

The Swedish girl patted her shoulder and smiled 9 in good humoured deprecation at Brisson and Estridge.

“God let her dearest friend die under the rifles of the Reds,” she explained cheerfully, “and my little comrade can not reconcile this sad affair with her faith in Divine justice. So she concludes there isn’t any such thing. And no Divinity.” She shrugged: “That is what shakes the faith in youth––the seeming indifference of the Most High.”

Palla Dumont sat silent. The colour had died out in her cheeks, her dark, indifferent eyes became fixed.

Estridge opened the fur collar of his coat and pulled back his fur cap.

“Do you remember me?” he said to Ilse Westgard.

The girl laughed: “Yes, I remember you, now!”

To Palla Dumont he said: “And do you remember?”

At that she looked up incuriously; leaned forward slowly; gazed intently at him; then she caught both his hands in hers with a swift, sobbing intake of breath.

“You are John Estridge,” she said. “You took me to her in your ambulance!” She pressed his hands almost convulsively, and he felt her trembling under the fur robe.

“Is it true,” he said, “––that ghastly tragedy?”

“Yes.”

“All died?”

“All.”

Estridge turned to Brisson: “Miss Dumont was companion to the Grand Duchess Marie,” he said in brief explanation.

Brisson nodded, biting his cigar.

The Swedish girl-soldier said: “They were devoted––the little Grand Duchess and Palla.... It 10 was horrible, there in the convent cellar––those young girls–––” She gazed out across the snow; then,

“The Reds who did it had already made me prisoner.... They arrested me in uniform after the decree disbanding us.... I was on my way to join Kaledines’ Cossacks––a rendezvous.... Well, the Reds left me outside the convent and went in to do their bloody work. And I gnawed the rope and ran into the chapel to hide among the nuns. And there I saw a White Nun––quite crazed with grief–––”

“I had heard the volley that killed her,” said Palla, in explanation, to nobody in particular. She sat staring out across the snow with dry, bright eyes.

Brisson looked askance at her, looked significantly at the Swedish girl, Ilse Westgard: “And what happened then?” he inquired, with the pleasant, impersonal manner of a physician.

Ilse said: “Palla had already begun her novitiate. But what happened in those terrible moments changed her utterly.... I think she went mad at the moment.... Then the Superior came to me and begged me to hide Palla because the Bolsheviki had promised to return and cut her throat when they had finished their bloody business in the crypt.... So I caught her up in my arms and I ran out into the convent grounds. And at that very moment, God be thanked, a sotnia of the Wild Division rode up looking for me. And they had led horses with them. And we were in the saddle and riding like maniacs before I could think. That is all, except, an hour ago we saw your sleigh.”

“You have been hiding with the Cossacks ever since!” exclaimed Estridge to Palla.

“That is her history,” replied Ilse, “and mine. And,” 11 she added cheerfully but tenderly, “my little comrade, here, is very, very homesick, very weary, very deeply and profoundly unhappy in the loss of her closest friend... and perhaps in the loss of her faith in God.”

“I am tranquil and I am not unhappy,”––said Palla. “And if I ever win free of this murderous country I shall, for the first time in my life, understand what the meaning of life really is. And shall know how to live.”

“You thought you knew how to live when you took the white veil,” said Ilse cheerfully. “Perhaps, after all, you may make other errors before you learn the truth about it all. Who knows? You might even care to take the veil again–––”

“Never!” cried Palla in a clear, hard little voice, tinged with the scorn and anger of that hot revolt which sometimes shakes youth to the very source of its vitality.

Ilse said very calmly to Estridge: “With me it is my reason and not mere hope that convinces me of God’s existence. I try to reason with Palla because one is indeed to be pitied who has lost belief in God–––”

“You are mistaken,” said Palla drily; “––one merely becomes one’s self when once the belief in that sort of God is ended.”

Ilse turned to Brisson: “That,” she said, “is what seems so impossible for some to accept––so terrible––the apparent indifference, the lack of explanation––God’s dreadful reticence in this thunderous whirlwind of prayer that storms skyward day and night from our martyred world.”

Palla, listening, sat forward and said to Brisson: “There is only one religion and it has only two precepts––love and give! The rest––the forms, observances, 12 creeds, ceremonies, threats, promises, are man-made trash!

“If man’s man-made God pleases him, let him worship him. That kind of deity does not please me. I no longer care whether He pleases me or not. He no longer exists as far as I am concerned.”

Brisson, much interested, asked Palla whether the void left by discredited Divinity did not bewilder her.

“There is no void,” said the girl. “It is already filled with my own kind of God, with millions of Gods––my own fellow creatures.”

“Your fellow beings?”

“Yes.”

“You think your fellow creatures can fill that void?”

“They have filled it.”

Brisson nodded reflectively: “I see,” he said politely, “you intend to devote your life to the cult of your fellow creatures.”

“No, I do not,” said the girl tranquilly, “but I intend to love them and live my life that way unhampered.” She added almost fiercely: “And I shall love them the more because of their ignorant faith in an all-seeing and tender and just Providence which does not exist! I shall love them because of their tragic deception and their helplessness and their heart-breaking unconsciousness of it all.”

Ilse Westgard smiled and patted Palla’s cheeks: “All roads lead ultimately to God,” she said, “and yours is a direct route though you do not know it.”

“I tell you I have nothing in common with the God you mean,” flashed out the girl.

Brisson, though interested, kept one grey eye on duty, ever hopeful of wolves. It was snowing hard now––a perfect geography scene, lacking only the 13 wolves; but the étape was only half finished. There might be hope.

The rather amazing conversation in the sleigh also appealed to him, arousing all his instincts of a veteran newspaper man, as well as his deathless curiosity––that perpetual flame which alone makes any intelligence vital.

Also, his passion for all documents––those sewed under his underclothes, as well as these two specimens of human documents––were now keeping his lively interest in life unimpaired.

“Loss of faith,” he said to Palla, and inclined toward further debate, “must be a very serious thing for any woman, I imagine.”

“I haven’t lost faith in love,” she said, smilingly aware that he was encouraging discussion.

“But you say you have lost faith in spiritual love––”

“I did not say so. I did not mean the other kind of love when I said that love is sufficient religion for me.”

“But spiritual love means Deity–––”

“It does not! Can you imagine the all-powerful father watching his child die, horribly––and never lifting a finger! Is that love? Is that power? Is that Deity?”

“To penetrate the Divine mind and its motives for not intervening is impossible for us–––”

“That is priest’s prattle! Also, I care nothing now about Divine motives. Motives are human, not divine. So is policy. That is why the present Pope is unworthy of respect. He let his flock die. He deserted his Cardinal. He let the hun go unrebuked. He betrayed Christ. I care nothing about any mind weak enough, politic enough, powerless enough, to ignore love for motives!

“One loves, or one does not love. Loving is giving––” The girl sat up in the sleigh and the thickening snowflakes drove into her flushed face. “Loving is giving,” she repeated, “––giving life to love; giving up life for love––giving! giving! always giving!––always forgiving! That is love! That is the only God!––the indestructible, divine God within each one of us!”

Brisson appraised her with keen and scholarly eyes. “Yet,” he said pleasantly, “you do not forgive God for the death of your friend. Don’t you practise your faith?”

The girl seemed nonplussed; then a brighter tint stained her cheeks under the ragged sheepskin cap.

“Forgive God!” she cried. “If there really existed that sort of God, what would be the use of forgiving what He does? He’d only do it again. That is His record!” she added fiercely, “––indifference to human agony, utter silence amid lamentations, stone deaf, stone dumb, motionless. It is not in me to fawn and lick the feet of such an image. No! It is not in me to believe it alive, either. And I do not! But I know that love lives: and if there be any gods at all, it must be that they are without number, and that their substance is of that immortality born inside us, and which we call love! Otherwise, to me, now, symbols, signs, saints, rituals, vows––these things, in my mind, are all scrapped together as junk. Only, in me, the warm faith remains––that within me there lives a god of sorts––perhaps that immortal essence called a soul––and that its only name is love. And it has given us only one law to live by––the Law of Love!”

Brisson’s cigar had gone out. He examined it attentively 15 and found it would be worth relighting when opportunity offered.

Then he smiled amiably at Palla Dumont:

“What you say is very interesting,” he remarked. But he was too polite to add that it had been equally interesting to numberless generations through the many, many centuries during which it all had been said before, in various ways and by many, many people.

Lying back in his furs reflectively, and deriving a rather cold satisfaction from his cigar butt, he let his mind wander back through the history of theocracy and of mundane philosophy, mildly amused to recognize an ancient theory resurrected and made passionately original once more on the red lips of this young girl.

But the Law of Love is not destined to be solved so easily; nor had it ever been solved in centuries dead by Egyptian, Mongol, or Greek––by priest or princess, prophet or singer, or by any vestal or acolyte of love, sacred or profane.

No philosophy had solved the problem of human woe; no theory convinced. And Brisson, searching leisurely the forgotten corridors of treasured lore, became interested to realise that in all the history of time only the deeds and example of one man had invested the human theory of divinity with any real vitality––and that, oddly enough, what this girl preached––what she demanded of divinity––had been both preached and practised by that one man alone––Jesus Christ.

Turning involuntarily toward Palla, he said: “Can’t you believe in Him, either?”

She said: “He was one of the Gods. But He was no more divine than any in whom love lives. Had He 16 been more so, then He would still intervene to-day! He is powerless. He lets things happen. And we ourselves must make it up to the world by love. There is no other divinity to intervene except only our own hearts.”

But that was not, as the young girl supposed, her fixed faith, definite, ripened, unshakable. It was a phase already in process of fading into other phases, each less stable, less definite, and more dangerous than the other, leaving her and her ardent mind and heart always unconsciously drifting toward the simple, primitive and natural goal for which all healthy bodies are created and destined––the instinct of the human being to protect and perpetuate the race by the great Law of Love.

Brisson’s not unkindly cynicism had left his lips edged with a slight smile. Presently he leaned back beside Estridge and said in a low voice:

“Purely pathological. Ardent religious instinct astray and running wild in consequence of nervous dislocations due to shock. Merely over-storage of superb physical energy. Intellectual and spiritual wires overcrowded. Too many volts.... That girl ought to have been married early. Only a lot of children can keep her properly occupied. Only outlet for her kind. Interesting case. Contrast to the Swedish girl. Fine, handsome, normal animal that. She could pick me up between thumb and finger. Great girl, Estridge.”

“She is really beautiful,” whispered Estridge, glancing at Ilse.

“Yes. So is Mont Blanc. That sort of beauty––the super-sort. But it’s the other who is pathologically interesting because her wires are crossed and 17 there’s a short circuit somewhere. Who comes in contact with her had better look out.”

“She’s wonderfully attractive.”

“She is. But if she doesn’t disentangle her wires and straighten out she’ll burn out.... What’s that ahead? A wolf!”

It was the rest house at the end of the étape––a tiny, distant speck on the snowy plain.

Brisson leaned over and caught Palla’s eye. Both smiled.

“Well,” he said, “for a girl who doesn’t believe in anything, you seem cheerful enough.”

“I am cheerful because I do believe in everything and in everybody.”

Brisson laughed: “You shouldn’t,” he said. “Great mistake. Trust in God and believe nobody––that’s the idea. Then get married and close your eyes and see what God will send you!”

The girl threw back her pretty head and laughed.

“Marriage and priests are of no consequence,” she said, “but I adore little children!”

They were a weary, half-starved and travel-stained quartette when the Red Guards stopped them for the last time in Russia and passed them through, warning them that the White Guards would surely do murder if they caught them.

The next day the White Guards halted them, but finally passed them through, counselling them to keep out of the way of the Red Guards if they wished to escape being shot at sight.

In the neat, shiny, carefully scrubbed little city of Helsingfors they avoided the huns by some miracle––one of Brisson’s customary miracles––but another little company of Americans and English was halted and detained, and one harmless Yankee among them was arrested and packed off to a hun prison.

Also, a large and nervous party of fugitives of mixed nationalities and professions––consuls, chargés, attachés, and innocent, agitated citizens––was summarily grabbed and ordered into indefinite limbo.

But Brisson’s daily miracles continued to materialise, even in the land of the Finn. By train, by sleigh, by boat, his quartette floundered along toward safety, and finally emerged from the white hell of the Red people into the sub-arctic sun––Estridge with painfully scanty luggage, Palla Dumont with none at all, 19 Ilse Westgard carrying only her Cossack saddle-bags, and Brisson with his damning papers still sewed inside his clothes, and owing Estridge ten dollars for not getting murdered.

They all had become excellent comrades during those anxious days of hunger, fatigue and common peril, but they were also a little tired of one another, as becomes all friends when subjected to compulsory companionship for an unreasonable period.

And even when one is beginning to fall in love, one can become surfeited with the beloved under such circumstances.

Besides, Estridge’s budding sentiment for Ilse Westgard, and her wholesome and girlish inclination for him, suffered an early chill. For the poor child had acquired trench pets from the Cossacks, and had passed on a few to Estridge, with whom she had been constantly seated on the front seat.

Being the frankest thing in Russia, she told him with tears in her blue eyes; and they had a most horrid time of it before they came finally to a sanitary plant erected to attend to such matters.

Episodes of that sort discourage sentiment; so does cold, hunger and discomfort incident on sardine-like promiscuousness.

Nobody in the party desired to know more than they already knew concerning anybody else. In fact, there was little more to know, privacy being impossible. And the ever instinctive hostility of the two sexes, always and irrevocably latent, became vaguely apparent at moments.

Common danger swept it away at times; but reaction gradually revealed again what is born under the human skin––the paradox called sex-antipathy. And 20 yet the men in the party would not have hesitated to sacrifice their lives in defence of these women, nor would the women have faltered under the same test.

Brisson was the philosophical stoic of the quartette. Estridge groused sometimes. Palla, when she thought herself unnoticed, camouflaged her face in her furs and cried now and then. And occasionally Ilse Westgard tried the patience of the others by her healthy capacity for unfeigned laughter––sometimes during danger-laden and inopportune moments, and once in the shocking imminence of death itself.

As, for example, in a vile little village, full of vermin and typhus, some hunger-crazed peasants, armed with stolen rifles and ammunition, awoke them where they lay on the straw of a stable, cursed them for aristocrats, and marched them outside to a convenient wall, at the foot of which sprawled half a dozen blood-soaked, bayoneted and bullet-riddled landlords and land owners of the district.

And things had assumed a terribly serious aspect when, to their foolish consternation, the peasants discovered that their purloined cartridges did not fit their guns.

Then, in the very teeth of death, Ilse threw back her blond head and laughed. And there was no mistaking the genuineness of the girl’s laughter.

Some of their would-be executioners laughed too;––the hilarity spread. It was all over; they couldn’t shoot a girl who laughed that way. So somebody brought a samovar; tea was boiled; and they all went back to the barn and sat there drinking tea and swapping gossip and singing until nearly morning.

That was a sample of their narrow escapes. But Brisson’s only comment before he went to sleep was that 21 Estridge would probably owe him a dollar within the next twenty-four hours.

They had a hair-raising time in Helsingfors. On one occasion, German officers forced Palla’s door at night, and the girl became ill with fear while soldiers searched the room, ordering her out of bed and pushing her into a corner while they ripped up carpets and tore the place to pieces in a swinishly ferocious search for “information.”

But they did nothing worse to her, and, for some reason, left the hotel without disturbing Brisson, whose room adjoined and who sat on the edge of his bed with an automatic in each hand––a dangerous opportunist awaiting events and calmly determined to do some recruiting for hell if the huns harmed Palla.

She never knew that. And the worst was over now, and the Scandinavian border not far away. And in twenty-four hours they were over––Brisson impatient to get his papers to Washington and planning to start for England on a wretched little packet-boat, in utter contempt of mines, U-boats, and the icy menace of the North Sea.

As for the others, Estridge decided to cable and await orders in Copenhagen; Palla, to sail for home on the first available Danish steamer; Ilse, to go to Stockholm and eventually decide whether to volunteer once more as a soldier of the proletariat or to turn propagandist and carry the true gospel to America, where, she had heard, the ancient liberties of the great Democracy were becoming imperilled.

The day before they parted company, these four people, so oddly thrown together out of the boiling cauldron of the Russian Terror, arranged to dine together for the last time.

Theirs were the appetites of healthy wolves; theirs was the thirst of the marooned on waterless islands; and theirs, too, was the feverish gaiety of those who had escaped great peril by land and sea; and who were still physically and morally demoralized by the glare and the roar of the hellish conflagration which was still burning up the world around them.

So they met in a private dining room of the hotel for dinner on the eve of separation.

Brisson and Estridge had resurrected from their luggage the remains of their evening attire; Ilse and Palla had shopped; and they now included in a limited wardrobe two simple dinner gowns, among more vital purchases.

There were flowers on the table, no great variety of food but plenty of champagne to make up––a singular innovation in apology for short rations conceived by the hotel proprietor.

There was a victrola in the corner, too, and this they kept going to stimulate their nerves, which already were sufficiently on edge without the added fillip of music and champagne.

“As for me,” said Brisson, “I’m in sight of nervous dissolution already;––I’m going back to my wife and children, thank God––” he smiled at Palla. “I’m grateful to the God you don’t believe in, dear little lady. And if He is willing, I’ll report for duty in two weeks.” He turned to Estridge:

“What about you?”

“I’ve cabled for orders but I have none yet. If they’re through with me I shall go back to New York and back to the medical school I came from. I hate the idea, too. Lord, how I detest it!”

“Why?” asked Palla nervously.

“I’ve had too much excitement. You have too––and so have Ilse and Brisson. I’m not keen for the usual again. It bores me to contemplate it. The thought of Fifth Avenue––the very idea of going back to all that familiar routine, social and business, makes me positively ill. What a dull place this world will be when we’re all at peace again!”

“We won’t be at peace for a long, long while,” said Ilse, smiling. She lifted a goblet in her big, beautifully shaped hand and drained it with the vigorous grace of a Viking’s daughter.

“You think the war is going to last for years?” asked Estridge.

“Oh, no; not this war. But the other,” she explained cheerfully.

“What other?”

“Why, the greatest conflict in the world; the social war. It’s going to take many years and many battles. I shall enlist.”

“Nonsense,” said Brisson, “you’re not a Red!”

The girl laughed and showed her snowy teeth: “I’m one kind of Red––not the kind that sold Russia to the boche––but I’m very, very red.”

“Everybody with a brain and a heart is more or less red in these days,” nodded Palla. “Everybody knows that the old order is ended––done for. Without liberty and equal opportunity civilisation is a farce. Everybody knows it except the stupid. And they’ll have to be instructed.”

“Very well,” said Brisson briskly, “here’s to the universal but bloodless revolution! An acre for everybody and a mule to plough it! Back to the soil and to hell with the counting house!”

They all laughed, but their brimming glasses went 24 up; then Estridge rose to re-wind the victrola. Palla’s slim foot tapped the parquet in time with the American fox-trot; she glanced across the table at Estridge, lifted her head interrogatively, then sprang up and slid into his arms, delighted.

While they danced he said: “Better go light on that champagne, Miss Dumont.”

“Don’t you think I can keep my head?” she demanded derisively.

“Not if you keep up with Ilse. You’re not built that way.”

“I wish I were. I wish I were nearly six feet tall and beautiful in every limb and feature as she is. What wonderful children she could have! What magnificent hair she must have had before she sheared it for the Woman’s Battalion! Now it’s all a dense, short mass of gold––she looks like a lovely boy who requires a barber.”

“Your hair is not unbecoming, either,” he remarked, “––short as it is, it’s a mop of curls and very fetching.”