Title: Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Author: Various

Editor: Harry Bates

Release date: October 3, 2009 [eBook #30166]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

W. M. CLAYTON, Publisher HARRY BATES, Editor DR. DOUGLAS M. DOLD, Consulting Editor

That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid, by leading writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the Authors' League of America;

That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS MONTHLY, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE, WESTERN ADVENTURES, and WESTERN LOVE STORIES.

More than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

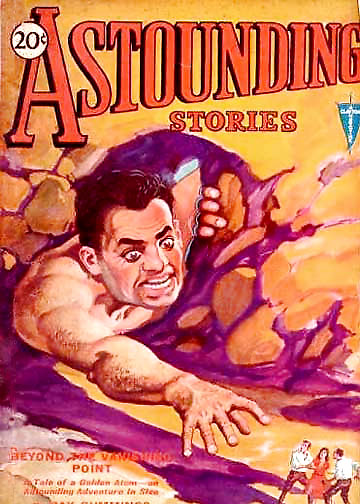

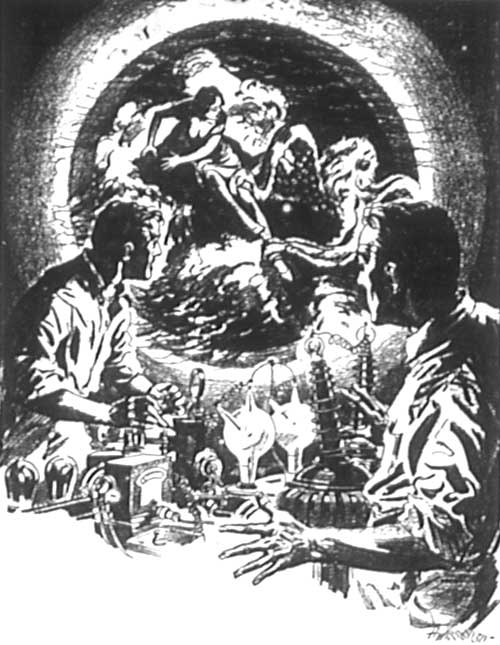

| COVER DESIGN | H. W. WESSO | ||

| Painted in Water-Colors from a Scene in "Beyond the Vanishing Point." | |||

| WHEN THE MOUNTAIN CAME TO MIRAMAR | CHARLES W. DIFFIN | 297 | |

| It is Magic against Magic As Garry Connell Bluffs for His Life with a Prehistoric Savage in the Heart of Sentinel Mountain. | |||

| BEYOND THE VANISHING POINT | RAY CUMMINGS | 314 | |

| The Tale of a Golden Atom—an Astounding Adventure in Size. (A Complete Novelette.) | |||

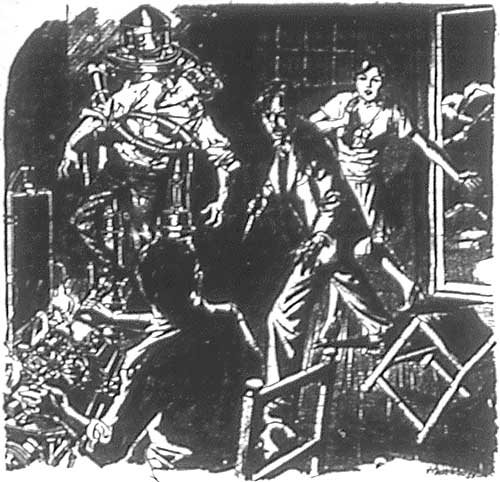

| TERRORS UNSEEN | HARL VINCENT | 360 | |

| One after Another the Invisible Robots Escape Shelton's Control—and Their Trail Leads Straight to the Gangster Chief Cadorna. | |||

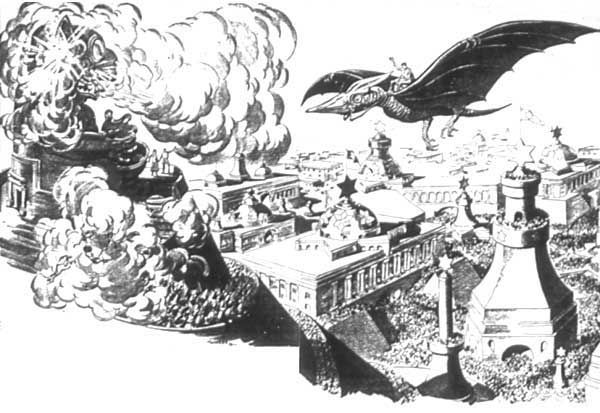

| PHALANXES OF ATLANS | F. V. W. MASON | 376 | |

| Never Did an Aviator Ride a More Amazing Sky-Steed Than Alden on His Desperate Dash to the Great Jarmuthian Ziggurat. (Conclusion of a Two-Part Novel.) | |||

| THE METEOR GIRL | JACK WILLIAMSON | 404 | |

| Through the Complicated Space-Time of the Fourth Dimension Goes Charlie King in an Attempt to Rescue the Meteor Girl. | |||

| THE READERS' CORNER | ALL OF US | 417 | |

| A Meeting Place for Readers of Astounding Stories. | |||

Single Copies, 20 Cents (In Canada, 25 Cents) Yearly Subscription, $2.00

Issued monthly by Readers' Guild, Inc., 80 Lafayette Street, New York, N. Y. W. M. Clayton, President; Francis P. Pace, Secretary. Entered as second-class matter December 7, 1929, at the Post Office at New York, N. Y., under Act of March 3, 1879. Title registered as a Trade Mark in the U. S. Patent Office. Member Newsstand Group—Men's List. For advertising rates address E. R. Crowe & Co., Inc., 25 Vanderbilt Ave., New York; or 225 North Michigan Ave., Chicago.

"That'll be all from you," he told the black one.

"That'll be all from you," he told the black one.

he first tremor that set the timbers of the house to creaking brought Garry Connell out of his bunk and into the middle of the floor. Then the floor heaved and 'dobe walls swayed while the man fought to keep his footing and pull himself through the doorway to the safety of the dark night. The earthquake that came with the spring of 1932 was on.

He was nauseated with that deathly sickness that only an earthquake gives, and he dropped breathlessly in the shelter of a date palm while the earth beneath him rolled and groaned in agony. A deeper roar was rising above all other sounds, and Connell looked up at the nearby top of Sentinel Mountain.[298]

The stars of the desert land showed clear; the grim blackness of Sentinel's lone peak rose abruptly from the sand of the desert floor in darker silhouette against the velvet of a midnight sky. And the mountain was roaring.

Softened by the distance, the deep, grumbling bass sang thunderingly through and above the other noises of the night, as if old Sentinel itself were voicing its remonstrance against this disturbance of its age-long rest.

The grumbling died to a clatter of falling boulders a hundred yards away at the mountain's base, and Connell's eyes discerned a puff of vaporous gray, a cloud of wind-blown dust, high up on the mountain's flank.

"Holy cats!" said Garry explosively, "what a slide! That must have ripped the old boy wide open."

His eyes followed the white scar far up on the mountainside, followed it down to the last loosened stones that had crashed among the date palms of Miramar ranch. "I don't just like the idea of the whole mountain moving in on me," he told himself; "I'll have to go up and look at that to-morrow."

t was afternoon of the following day when Garry rolled blankets and food into a snug pack and prepared for the ascent. "Guess likely I'll sleep out to-night," he mused and looked at the pistol he held in his hand.

"I don't want that thing slapping against me," he argued; "too darned hot! And there's nothing to use a gun on up on Sentinel.... Oh, well!" He threw the holster upon his bunk and dropped the automatic into the pack he was rolling. "I'll take it along. Might meet up with a rattler."

He brushed the sandy hair from his wet forehead and straightened to his full six feet of slender height before he slipped the straps of his pack about his shoulders. And a broad grin made pleasant lines about his gray eyes as he realized the boyish curiosity that was driving him to a stiff climb in the heat of the day.

There was no real trail up the thousand-foot slope of Sentinel Mountain. Prospectors had been over it, doubtless, in earlier days, but in all of Garry's twenty-one years no one besides himself had ever made the ascent.

There was nothing in all that solitary, desolate peak to call them; nothing, for that matter, to beckon Garry, except the hot desert days, the cool breath of evening and the glory of nights when the stars hung low over all the miles of sand and sagebrush that reached far out to the rippling sand-dunes shimmering in the distance. Nothing, that is, but the "feel" of the desert—and young Garry Connell was desert-born and bred.

He stopped once and dropped his pack while he mopped his wet face. From this point he could see his own ranch spread below him. Miramar, he had named it—"Beautiful Sea." The name was half an affectionate mockery of this land where the nearest water was fifty miles away, and half because of the sea of blue that he looked at now. Garry had never ceased to wonder at the mirage.

It was always the same in the summer heat—a phantom ocean of water. Garry's eyes loved to follow the quivering blue expanse that seemed so cool and deep. It rippled softly away to end in a line of white, like distant breakers on the horizon's rolling dunes.

This had been the bed of an ocean in some distant past, and that ancient ocean could never have seemed more real than this; yet Garry knew that this sea would vanish with the setting sun. He had watched it often.

hundred yards farther and he stopped again. It was no well-trodden path that Garry followed, but he knew his landmarks. There was the big split rock a half mile ahead, and the three-branched cactus beside it. But between these and the place where Garry stood was a fan-shaped sweep of boulders—and this where smooth going had been before.[299]

He forgot for the moment all discomfort. He stood staring under the hot sun that cast purple shadows beside the weathered rocks, and his eyes followed up the scarred mountainside.

"That whole ledge that stood out up there—that's gone!" he told himself. "The whole side of the mountain just shook itself loose...."

Far above, his eyes found another towering mass that reared itself menacingly. "That will come down next time," he said with conviction, "and I don't want to be under it when it breaks loose." Then his searching eyes found the lower ledge and its shattered remains.

It had held a welter of rocks above it as a dam holds the pressure of water—and the dam had burst. The torrent of stone from above had swept into motion and carried with it the accumulation of loose rubble below. Where the ledge had been was now a cliff—a sheer wall of rock. It had been covered before by the talus that was swept away.

Garry's eyes narrowed to see more plainly under the sun's glare. He was staring not alone at the cliff but at a shadow within it—a black shadow in the white face of the cliff itself.

"That was all covered up before," Garry stated; "buried for thousands of years, I suppose. But it can't be a cave; not a natural one, at least. There are no caves in this rock."

He stopped at times for breath, and his wonder grew as he climbed and the black mark took clearer form. At last he stood panting before it, to stare deep into the utter blackness of a passageway beyond an entrance of carved stone.

It was carved; there was no mistaking it! Here was a passage that nature had never formed. He took a quick stride forward to see the tool marks that showed on hard walls where symbols and figures of strange design were carved. An intrusion of harder rock had formed a roof, and they had cut in below—

"They!" He spoke the word aloud. Who were "they?"

e remembered the scientist who had stopped at the ranch some time before, and he recalled enough of the talk of Aztec and Toltec and Mayas to know that none of these old civilizations could explain the things he saw.

"This goes way back beyond them—it must," he reasoned. And there were pictures, long forgotten, that came to his mind to show him a vision from the past—figures whose coppery faces shone dark above their brilliant, colored robes—slaves, toiling and sweating to drive this tunnel into solid rock. He was suddenly a-quiver with a feeling of the presence of living things. His breath seemed stifled within him as he stepped into the dark where a pencil of light from his pocket-flash made the blackness more intense.

He tried to shake off the feeling, but an indefinable oppression was heavy upon him; the weight of the uncounted centuries these walls had seen filled him with strange forebodings.

His feet stumbled and scuffed over chips of stone; he steadied himself against the wall at times as he followed the corridor that went down and still down before him. It turned and twisted, then leveled off at last, and Garry Connell drew himself up sharply with a quick-drawn breath.

His flash was making a circle of light a dozen steps ahead, and showed a litter of sharp stone fragments. And, scattered over them, a tangle of bones shone white; one skull stood upright to stare mockingly from hollow sockets. The sudden white of them was startling in the black pit.

"Bones!" he said, and forced himself to disregard the echoes that tried to shout him down; "just bones! And the old-timers that wore them haven't been using them for thousands of years." He moved forward with determined steps to the end of the passage that finished in solid stone. He stopped abruptly. At closer range was some[300]thing that froze him to a tense, waiting crouch.

This wall of solid stone—it was not solid as it had seemed. There was a doorway; the stone was swung inward; and at one side in a straight-marked crack, he saw a thread of light.

He snapped off his own flash. Someone was there! Someone had beaten him to it! He held himself crouched and rigid at the thought. But who could it be? The utter silence and the steady, unchanging, pale-green light showed him the folly of the thought. There was no one there; there couldn't be anyone.

is hand, that trembled with excitement, reached across and over the skeleton remains posted like a ghostly guard before the door. He threw his weight upon the stone.

Its bearings groaned, but it moved at his touch. The stone swung slowly and ponderously into a silent room, and Garry Connell stared wide-eyed and wondering where rock walls, in carved and colored brilliance reflected the softest of diffused light.

A great room, hewn from the solid rock!—and Garry tried to see it and all that it held at one glance. He grasped the extent of the stone vault, a hundred feet across; the distant walls were plain in the soft light.

One high point of flashing color caught his eye and held it in marveling amazement. A thing of beauty and grace. It was a shining, silvery shape like a mushroom growth; it towered high in air, almost to the ceiling, a slender rod that swelled and opened to a curved and gleaming head. Graceful as a fairy parasol, huge enough to shelter a giant, it was like nothing he had ever seen.

But there was no time now for conjectures. He made no effort to understand; he wanted only to see what might be here; and his eyes flashed quickly over sculptured walls and a stone floor where metal boxes were arranged in orderly rows.

Hundreds of them, he estimated; huge cases, some eight or ten feet long. Two nearby were raised above the floor on bases of carved stone. Lusterless gray in color—metal, unmistakably—and in them....

"No use getting all hopped up over treasure hunting," Garry had told himself. But under all his incredulous amazement had been flickering thoughts of what he might find.

He stared hungrily at those two boxes near him. Each of the hundreds was big enough to hold a fortune. He reached for a metal bar beside the scattered bones, and, like a man in a sleep-walking dream, he stepped across those relics of earlier men and entered the room that they had guarded.

The light stopped him for a moment. He puzzled over it; stared wonderingly at a circle of glowing radiance in the roof of stone. It reminded him of something ... the watch on his wrist ... yes, that was the answer—some radio-active substance. His eyes came back to the nearest chest, and he jammed the point of his corroded bar beneath the flange of a tight-fitting lid.

he hidden room was cool, but Garry Connell wiped the sweat from his eyes when he ceased his frantic efforts. The metal bar clanged loudly upon the floor beside him. He stood, breathing heavily, his eyes on the metal cover that refused to move. And in the silence there came to him again that strange, prickling apprehension. He caught himself looking quickly behind him as if to find another person there.

His eyes were accustomed now to the pale light, and the sculptured figures on the walls stood out with startling distinctness. Garry turned to look at the nearer wall and the figure that was repeated over and over again.

It was a man, tall and lean, his robes, undimmed by the years, blazed in crimson and gold. But the face above! Garry shivered in spite of himself at the devilish ugliness the artist had copied. It was dead black in color, with slitted[301] eyes that had been touched up artfully to bring out their venomous stare. The head itself rose up to a rounded point that added to the inhuman brutality of the face.

He was seated on a throne, Garry saw, and other figures, less skilfully carved, were kneeling before him. Again, he was standing above a prostrate enemy, a triple-pointed spear raised to deliver the final blow.

Silently, Garry let his eyes follow around the room with its repetition of the horrible being who was evidently a king. Then he whistled softly. "Nice kind of hombre, he must have been," he said. And, "Boy," he told the carved image familiarly, "whoever you were, you've been dead a long time, and I don't mind telling you I'm glad of it."

He was slowly circling the first casket. Beyond it was the slender rod with its mushroom head that seemed more like a bell as he looked from below. The head's inner surface was emblazoned, like the figures on the wall, with crimson and gold in strange designs. He saw now that the base of it was connected with a smaller box, placed like the two beside it on a stone pedestal.

He came slowly beside it to study the box with narrowed eyes. He expected the metal cover would be as immovable as the others, and he started back and caught his breath sharply as the metal raised at his touch and the green radiance from above flashed back from within the box in a thousand scintillant lights. Then he stooped to see the brilliant, silvery sheen of metal wheels that moved on jeweled bearings.

mechanism of some sort—but what? he wondered. He had some knowledge of the stream of electrons that discharged continuously from the light above, and he knew how they could charge an electroscope that would automatically discharge to produce motion. He nodded in half-understanding as the fluttering gold-leaf fell and allowed a tiny wheel to move one notch in its escapement.

"Clockworks!" he told himself—it was as near as he could come to a name for the machine—"and it's been running here all this time.... What for, I wonder? What was it supposed to do?"

He stared again at the bell-shape towering above him, but its purpose was beyond guessing: it was a part of the machine. His eyes came back to the mechanism itself. There was a splinter of stone.... Garry reached for it unthinkingly, but his hand was checked in mid-air.

The fragment was wedged beneath a tiny lever, holding it erect. "That's the answer," Garry whispered. "The machine was left open,"—he felt of the cover that had been dented by some heavy blow, and saw sharp splinters of rock beneath his feet—"a rock fell from the roof, flaked off and dropped onto the machine, and a splinter jammed this little lever. But the machine has been ticking along...."

His fingers reached for the stone.

"Let's go!" he said, and grinned broadly at the thoughts that were in his mind. "Let's see what the machine would have done!"

The fragment came away within his hand, and he saw the lever fall slowly. There was motion within the case—wheels and shining spheres that touched one upon another were spinning in gleaming circles of silvery green—and from above he heard the first faint whisper of a sound.

It came from the bell, and Garry drew back to stare upward. The first soft humming of the clear bell-note was incredibly sweet. It rose in pitch while the volume increased, till the musical note was lost in the rising roar that resounded from walls and roof. Higher it rose; it was a scream that was human in its agony, prodigious in its volume!

arry Connell stood trembling with unnamed fear. This sound was unbearable; it beat upon his[302] ears; it battered his whole body; it searched out every quivering nerve and tore at it with fingers of fire. Still higher!—and the scream was piercing and torturing his brain. He felt the jerk of uncontrollable muscles.

The whirling machine was a blur of light, and he longed with every fibre of his tortured mind to throw himself upon it—into it!—anything to end the unbearable impact from on high. His body, assailed by a clamor that was physical torment, could not move; the vibrations beat him down with crushing force, while the shrieking voice rose higher, then grew faint, and, with a final whisper, died to nothingness.

And still Garry felt himself sinking; the room was blurred; the excruciating agony of tortured nerves melted into a lethargy that swept through him. Dimly he sensed that the monstrous, quivering, bell-topped thing was still launching its devastating rain of vibrations; they were above the range of hearing; but he felt his body quivering in response to the unheard note. Then even these vague fragments of understanding left him. The towering, soundless thing was indistinct ... it vanished in the darkness that closed about....

He was upon the floor in a crouching heap when the tremors that shook him ceased. His mind, in the same instant, was cleared, and he knew that the soundless vibrations from the bell had ended. A wave of thankfulness flooded through him, and he luxuriated in the utter silence of the room—until that silence was broken by another sound.

It was hard and metallic, like the click of a withdrawn bolt, and came first from the case at his side. A second sharp rap replied from the other raised casket, then an echoing tattoo of metallic impacts rattled and clattered in the resounding room. Each of the hundreds of caskets was adding its voice to the clacking chorus.

he paralysis that had held Garry's muscles was gone, and he came slowly to his feet to see the edge of the cover he had tried vainly to move, rising smoothly in the air. His eyes darted about; the second casket was opening; beyond were countless others; the room was alive with silent motion where metal lids lifted like petals of flowers unfolding to the sun.

The machine had done it! The conviction came to him abruptly. Those vibrations that had beaten him down had done this: some unlocking mechanism within each case had been actuated when the vibrations reached the proper pitch. Then the thoughts were driven from his mind by a more thrilling conviction: The caskets were open! The treasure! Who could know what some of them might contain? He took one quick step toward the nearer of the two.

One step!—and his reaching hands stopped motionless above the open case. The contents of the box were plain before him—and he stared in horror at the black, half-naked figure of a man as silent and unmoving as its counterpart upon the wall.

Black as a carving in ebony, it was the face that held Garry's eyes. He saw the pointed head, the thin lips half-drawn from snarling teeth, the expression of brutal savagery that even this frozen stillness could not conceal.

The eyes were closed; Garry saw their slitted lids. He was looking at them when they quivered and twitched. The lids opened slowly, drew back from staring eyes that were cold and dead—eyes that came suddenly to life, that turned and stared unwinkingly, horribly, into his.

arry's lips were moving as he drew back in slow retreat, but he heard no sound of his own voice, only a husky whisper that said over and over again: "Mummies! Caskets of mummies! And they're coming back to life!"

Suspended animation. He had heard of such things. Dim, fleeting remembrance of what he had read came flashingly to him—toads that had lived a[303] thousand years sealed up in rock—but this, a human thing, a man!—no, no!—it couldn't come to life; not after all this time!

The pointed head, the ugly, menacing face and the body of dead black that rose slowly within the casket gave his argument the lie. In dreadful, living reality he saw the thing before him as it stretched its corded neck, extended and flexed its long, black arms and breathed deeply through lips drawn thin. Then, with a bound of returning energy, it leaped out and down to stand half-naked and black, towering threateningly above his head.

And Garry, too stunned to feel a sense of fear, looked first at the living face before him and then at the carvings done in stone. There was too much here for instant comprehension; his reason could not follow fast enough where facts were leading, and his mind seemed groping for some certain, proven thing.

"It's the same one that's on the wall," he explained painstakingly to himself. "It's the king, the old boy himself! I said he would be a bad hombre; I said he was a bad one—"

He saw the other raise his hands threateningly, and he crouched to meet the attack. But the black hands dropped, and the scowling face turned, while Garry's eyes followed toward a sound of movement in the second casket.

The green light flooded down, and Garry Connell glanced quickly at the doorway. Too many of these blacks and this would be no safe place for him. He was expecting another apparition like the first; he would have thought himself prepared against any further surprise, but his gray eyes opened wide at what the light disclosed.

here was the casket, gray and lusterless on its low, stone base. Its cover, like the others, stood erect, and above the nearer edge an arm was raising. But it was a white arm, and it ended in a slim, white hand!—its rounded softness held in clear outline against the back ground of gray, until the arm fell that the hand might grip the metal edge.

Garry's eyes held in wondering fascination upon those slender white fingers. The hand of a woman—a girl!—what marvel of miracles was this? He held his silent pose while he stared at the face that appeared before him.

It was milk-white against the dull gray metal beyond, the white of death itself, until returning circulation brought a flush of pink that crept slowly to the rounded cheeks. Dark hair cascaded about the shoulders to mingle with a lacy veil of golden threads. A film of golden lace wrapped about her—her robes had gone to dust, vanished with the vanished years—and only the threads of gold with which the robe was shot remained, a futile concealment for the slim white of her shoulders, the soft curves of rounded breasts. But Garry's eyes were held by the eyes that looked and locked with his.

Dark eyes, deep and steady, yet glowing softly with the wonder of this awakening. Windows, crystal clear, through which shone softly a light that filled him through and through!

Alluring as was the rounded whiteness of the form so thinly veiled, it was not this nor the childlike beauty of the face that held him spellbound. Garry Connell's only love had been the desert, and now he was filled and shaken by the glamour from within these thrilling eyes.

A rasping word made echoes in the silence, and Garry saw the girl's eyes widen as she turned them upon the black one, who had spoken. He saw her face lose its color and go dead white, and plainly her wide eyes showed the fears that swept in upon her with returning remembrance.

arry followed her gaze to the wild figure whose slitted eyes glittered in savage triumph and pos[304]sessiveness at the white beauty of the trembling girl. The lean figure spoke again in that rasping, unintelligible voice—he addressed the girl now—and the tone sent a strange prickling of animosity through every fibre of the watching man.

The black one took one stride forward; the girl, in a flash of white and gold, sprang from her resting place to take shelter behind the high casket. Her eyes came back to Garry's, and the call for help though voiceless was none the less real.

Then her pale lips moved, and she called to him with a clear voice that uttered unknown words.

Garry came from the spell that bound him, and with a quick rush made between her and the advancing man. He landed tense and crouching, and his voice was hoarse with excitement when he spoke.

"That'll be all from you," he told the black one.

His words could mean nothing to this savage, but the tone that rang through them, and his crouching, ready pose, must have been plain. The inky face beneath the high-pointed dome of head was twisted with rage; the eyes glared at this being who dared to oppose him. But the black one paused, then stepped backward to the casket where he had been.

Garry retreated a few slow steps to the end of the metal box that sheltered the girl. "Can't you understand me?" he asked. "Am I dreaming? What has happened? Who are you, and who is this black beast? What does it all mean?"

Again he was sure that mere speech useless, but he felt that he had to speak, to say something, anything, to prove the reality of his own waking self and of the wild, nightmare experience.

He saw the crouching girl rise to her full height; he saw the movement of her hand as she swept the dark hair away from her face, and the film of gold lace clung closely about her as she came to his side. One hand was outstretched to rest, light and cool, upon his forehead.

e heard her voice, so soft and liquid yet so charged with terror. She spoke meaningless words and phrases, but at the touch of her hand upon his face he started abruptly.

Did the words themselves take on meaning and coherence, or was it something within himself?—Garry could not have told. But, with the startling clarity of a radio switched full on, he got the impress of her thoughts, and his own brain took them and put them into words that he knew.

"You will help me, you will save me," the words were saying. "You are one of us, I know. You are a stranger, but your skin is white; you are not of the tribe of Horab."

Garry was motionless and listening. He knew he was sensing her thoughts—she was communicating with him by some telepathic magic—and he knew, as he caught the words, that Horab was the black one there before him, reaching and feeling within the casket where he had slept. Horab—a savage king of a savage land—

"He captured me," the words continued in breathless haste. "I am from Zahn: do you know the good land of Zahn? I am Luhra. Horab captured me; carried me here to this island; it was yesterday he brought me here. He put me to sleep, and he put his men to sleep, hundreds of his chosen warriors. He worked his magic, and he said we would sleep for one hundred summers. But it was yesterday. And now you will save me; my father is a great man; he will reward you—"

The sentences flashed almost incoherently into his mind, but ceased at a sound and stirring from the room at their backs.

Garry needed a moment for the substance of the message to register. He had heard it as truly as if she had spoken: Horab had captured her—yesterday!... And his own lips that had[305] been loose with astonishment closed to a grim smile.

"Yesterday!" She thought it was yesterday that her long night had begun. Did Horab know the truth? Garry was suddenly certain that he did. Horab's plans had miscarried; he could not know how far in a distant past was that day when he had placed himself and this girl in their caskets, safe in their mountain tomb.

nly an instant for these thoughts to form—then his eyes were steady upon the tall savage who had found what he sought in the big metal case. Horab, king of a vanished race, turned now with a heavy scepter in his hand; and its jeweled head flashed brilliantly as he raised it high in air and shouted an echoing command into the room. A white hand was tugging at Garry's shoulder, a soft body clinging close, to turn him where new danger threatened.

The other caskets! He had forgotten them, and he saw the nearer ones alive with struggling forms. A black man-shape, with sullen, animal face and pointed head, came slowly erect and staggered upon the floor. Another—and another! There were scores of the black, naked men who scrambled from the nearer caskets and swayed drunkenly upon their feet.

Garry stood tense, his mind a chaos of half-formed plans. This one brute he might handle, but the whole tribe—that was too large an order. Yet he knew with an unshakable conviction that he would carry this girl from their evil clutches or die in the trying.

Feminine charms had failed to interest Garry in that world outside, but now the message of these soft eyes, the appealing beauty of this lovely face, proud and unafraid despite her fears, the hand so soft and trusting upon his face!—there had something entered into Garry Connell's lonely life that struck deep within him and found a ready response.

He swept one arm about the soft, yielding body beneath its wisp of garment, and he swung her behind him as he set himself to meet the attack. And he flashed her a look that must have carried a message, for the trembling lips were framing a ghost of a smile as her eyes met his.

Garry's thoughts darted to the gun, but his tightly-wrapped pack was in the passage outside. He prayed for a moment's time that he might meet this mob pistol in hand, and he half turned; but no time was given. The leader was shouting orders, his harsh voice resounded in shattering echoes throughout the stone vault, and the horde of blacks surged forward at his command.

mass of lean bodies, with faces ugly and brutal where sleep-filled eyes opened wide and glaring! They crowded upon him, and Garry met the rush with a rain of straight rights and lefts into the nearest faces. He was carried backward to the wall by the weight of their numbers, but he saw some go down for the count.

The room seemed filled with leaping, shouting men. Their shrill cries echoed in a tumult of discord, and above all Garry heard the hoarse screams of their leader.

There were fists and arms clubbing at his head. He warded them off, then sprang from the wall, leaping outward and sideways, where there was room for free swings of his pounding fists. Another black face went blank under the impact of his blow—a second—and a third!

He was giving ground slowly as the others came on. Then beyond the crowding figures he saw one who held a trident spear high in air. The weapon was poised; the metal points shone in the green light—points that would tear his body to shreds at a single blow.

Garry paused but an instant, then opened his clenched fists to clutch the lean neck of an enemy before him. He whirled the man's body and held it as a shield while he reached vainly to grip at the thrusting spear. Dimly he[306] saw the flash of white and gold where the girl, Luhra, threw her own body upon the armed figure and clung in desperation to the shaft of the deadly weapon.

arry hung fast to the struggling body, that was his shield; there were other spears now that flashed in the air. He loosed one hand and landed a short jab in the face of a savage whose hands were at his throat. The blow was light, and he was amazed to see the man stagger and fall. There were others who swayed helplessly and stumbled to their knees. Spears rang sharply, clattering upon the stone.... They were falling. The body he held went suddenly limp within his arms and sagged heavily to the floor....

Garry saw the one who had threatened him drop; he took the girl with him as he fell, and his spear flew wildly from his open hand. Garry was alone!—and the enemy was only a tangle of sprawling bodies where the twitching of an outflung arm marked the last sign of life.

He was breathing hard, for some of the enemies' blows had landed, and he staggered as he wiped a trickle of blood from his eyes. No time to figure what this meant, but the blacks were certainly out of it. Beyond the huddled bodies the tall figure of Horab leaped wildly in air as he sprang forward, and in the same instant Garry threw himself between the black menace and the prostrate girl.

He staggered again as he landed from his wild leap, and he called for his last reserve of strength to put power behind the blow that he launched for the snarling face above.

The heavy scepter swung high, and was falling as Garry struck. He saw the blow start; saw the fiery arc the jeweled head made in descending like a mace above his head. Then the face of Horab vanished, and the room was a whirling place of flashing red and yellow before blackness blotted it out....

arry awoke to blink stupidly at a green light above him. His head was a blinding, throbbing pain that blurred his thoughts.

It cleared slowly. The gleaming figure of a girl was rising from the floor. His aching eyes saw the white of her young body through the dull glow of golden lace. Her eyes came to his, and sharply he realized that this was no dream—this cave whose walls seemed swaying, the face that was staring pitifully at him, and, beyond, in a ghastly green light, the dark silhouette of a lean man who bent his pointed head above a chest.

Connell's mind was a whirl of snarled thoughts and emotions, of puzzled wonder and fighting rage; yet strangely through and above them all was a feeling of pure joy in the message of the eyes in a face that was utterly lovely.

The black figure had opened the chest. Garry saw the luminous green about it shot through with the reflected radiance of many gems. Jewels cascaded brilliantly from the lean black hands as they withdrew a golden cord. Part of some gem-incrusted fabric, it was, that he tore roughly from its rotted fastenings before coming swiftly to the still helpless body of Connell.

Garry's struggles were futile; his hands were tied before him. The shooting pain of a prodding spear brought him from the paralyzing numbness that held him, and he came dizzily to his feet. Again the walls whirled, and he would have fallen headlong but for a lithe, soft body that sprang close to throw white arms about him.

Through blood-shot eyes he saw Luhra, of the land of Zahn, with head held high and flashing eyes as she turned squarely to face the savage black. And he heard the stream of strange sentences that she poured protestingly upon him.

er message broke off abruptly. Garry's eyes followed hers to watch a savage king, naked but for the[307] tattered remnants of robes that time had eaten. He was reaching, into a casket that had once held kingly raiment—reaching with a lean black hand that brought forth only fragments of purple and crimson cloth that went quickly to dust within his hands.

Garry saw the slitted eyes stare in puzzled wonder at the rotted cloth, then glance sharply and inquiringly about. He saw the black one place a jeweled head-dress of barbaric splendor upon his ugly, pointed head, then rise and cross slowly to the heap of bodies. Spear in hand, he passed on to the serried rows of caskets.

Those nearest were empty, as Garry knew; he had seen the eruption of life from within them. Horab, with a growled word, moved on to the other caskets that stretched out across the room. The ugly head stooped; again the hands reached down, to come back this time with an empty, gleaming skull.

Garry thought once of his pistol, but knew in the same thought that he could never reach it; the spear of Horab would crash through him at the first movement. He dismissed the thought—forgot it—and forgot all else in the fascination of beholding the sagging lips and the scowling stupefaction on the black face of Horab. And slowly there came to his throbbing brain an explanation.

One hundred summers, Luhra had said—Horab had meant to sleep for a hundred years—and the machine that was to waken him had failed to function. Ages beyond computing had passed, and these two only, the black king and the girl, had survived. They had been directly beneath the light; its flooding energy had brought them safely through the dreamless years. But, for the others, it had been different.

Those nearest the light had responded to the vibrating call, but their vitality was gone; their moment of life was short. As for the hundreds who had felt the light but faintly—the skull told the story. They had died as they slept, died thousands of years ago, and their skeletons were all that remained to mock at their king and the frustration of his plans.

ut what was the purpose of the long sleep? Luhra's touch and her soundless words supplied the answer.

"Why did he wish this?" her mind said, repeating his question. "Horab's own country was lost; the yellow-ones from across the great water had conquered and overrun it. But Horab had planted the seeds of disease, and the yellow ones must all die in time. Horab is a king and a worker of magic; he is in league with a devil; he learns his magic of him. We of Zahn, all feared the magic of Horab—" She stopped at the quiver of rock beneath their feet.

Garry's mind had cleared, but it was an instant before he knew that the movement was not in his own throbbing head. Then the earth tremor came unmistakably, and his thoughts flashed back to the mass of rock above the mouth of the cave. If more quakes were coming they must get out, and do it at once—

The black hand of King Horab cast the skull vindictively against the wall, and the clatter of its falling fragments mingled with strange oaths from the savage lips. Then he came toward the two and Garry searched his mind desperately for some means of escape.

The trident spear was aimed, and Garry waited for the throw. He felt, more than saw, the flash of light that was Luhra as she sprang for a spear beside the fallen men. An instant and she was before him, tense and poised, a golden Amazon, whose upraised arm and steady eyes checked even Horab in his advance.

She spoke to the savage in sharp, staccato phrases, but Garry got no meaning from the words. There was a quick interchange between them; vehement protest and shaking of his[308] poised spear on the part of Horab. Luhra added a word or two, and she lowered her weapon as Horab did the same.

Her head was bowed as she reached to touch Garry's forehead. He sensed a hopeless sorrow that was so plainly hers, but with it he felt a mingling of another emotion that stirred him to the depths of his being. The slim, white figure straightened, and the dark eyes squarely upon his when she spoke.

"Listen carefully," she said; "it is the last time—"

arry found himself trembling; he was suddenly breathless with emotion. The racking pain in his head had settled to a dull ache, but his brain was clear, and through it were flashing strange thoughts.

The threat, the wild adventure itself!—they were nothing before the truth that was so plain to him now. He loved this girl! he loved her!—and his whole self responded with an inflow of fresh energy at the thought. A stranger from a strange, lost world!—but what of it?—he loved her!... The message from the lips and fingers of the girl broke in upon the thoughts that were crying for expression.

"You think of me." She smiled with her lips and eyes. "I am glad that you do, my dear one, but it is hopeless.

"Listen: I have promised; Luhra has spoken: I will go with Horab to do as he wills. I will go freely, and he will leave you here unharmed. He promises me this.

"I will go with Horab far across the blue water that surrounds us here. It is an island, as you know, for have you not come here from afar?" Garry broke in with a startled exclamation. An island! Water! He closed his lips upon the denial of her words.

"And you," Luhra continued unheeding, "when we have gone, will return to your own land.

"But, oh, my dear one, remember always I love you. I have read your thoughts, oh bravest and tenderest of men; I loved you from the moment when my eyes opened and found you waiting there. I am telling you now, for I will never see you again." She broke in upon the wild urge of protest that filled his mind.

With an imperious gesture she motioned Horab to discard his spear, and she placed hers beside it on the rocky floor. But she flinched and retreated from the outstretched arms and grasping hands, while Garry Connell struggled in insane frenzy at the cords that bound his wrists.

He felt the lean hands of Horab upon him, and the long arms held him in a crushing grip. And he saw the black face laugh evilly at the watching girl as Horab kicked the spears over beside the casket where she had been.

Garry felt himself raised in air, and he was as helpless as a child in that grasp. An instant later he was thrown heavily, to lie bruised and breathless in the metal box where first he had seen Luhra's face in wide-eyed awakening.

he rasping voice of Horab rose high and shrill. He was shouting triumphantly at the girl, while his hands worked to bind Garry's feet. Luhra's head and shoulders showed above the casket edge as she circled swiftly to approach from the opposite side and reach a trembling hand that would make the contact necessary for thought transference. Her cool touch was upon him; Garry ceased his futile struggle while her words came, brokenly to his mind.

"Horab has tricked us," she cried; "he is leaving you here. He will paralyze you with the devil song of the bell, but not to sleep as I did: it will stop on another note. He says you will be always awake, but helpless—thinking—thinking—always!"

She buried her face in her hands to hide from his gaze the horror that was in her eyes. Garry Connell's straining hands went limp. The terror in the girl's voice struck through his own[309] wild medley of thoughts to make him shudder with realization of the truth.

The threat was real! If Horab left the cave and took Luhra with him, the two would die in the desert. The black savage would never dare to face the strange, new world. And he, Garry, would be here in this cave, in this very coffin, held in a waking death. No one knew he was here; only by chance would the cave be investigated. And when someone finally came!

Garry stared in fascination at the green light. He knew with terrible certainty that whatever help might come would come too late. To lie there hour after hour, for days and then for years—waiting!—always waiting!... And he could never still his thoughts.... He had a sickening realization of the thing they would find. A body!—his body!—and the mind within it utterly insane....

The sound of the shrieking bell was in his ears, and his nerves were trembling in response. He saw long arms above the casket, tearing away the figure of a struggling girl.... And then he knew he was alone....

he sound of the bell rose to the piercing, nerve-shredding scream he had heard before. He must think fast—and act!—but the numbness of brain and muscle was creeping upon him. He tried to call out, but his throat was tight, and would not respond. The echoes died into silence; the vibrations, as before, passed beyond audible range. He was sinking ... sinking....

Dimly he felt the casket shaking beneath him. In some distant corner of his mind he knew that the earthquake shocks had turned. Then he heard with ear-splitting plainness the shrieking discord as the tremor shook the vibrating machine to silence.

The room was quiet; the paralysis left him; and in the instant of his release the clear brain of Garry Connell flashed from chaos to lay before him a full-formed plan.

"Luhra!" he called in the silent room. "Luhra!" But it seemed an age before he heard Horab and his captive returning from the passage. Then the touch of her hand gave him courage to continue.

"Yes?" she whispered; "yes, my dear one?"

He saw the shoulders of the black as he half-raised a spear threateningly toward the girl, then turned to adjust the whirring machine.

"Tell him," shouted Garry, "—tell Horab to shut off that damnable machine!" The shriek of it was rising again to drown his voice. "Tell him his life depends upon it. Tell him to listen to what I say or he will die."

He heard the girl's voice raised in a high-pitched call, and he heard the rasping snarl of Horab in reply. The girl repeated her cry above the echoing clamor of the bell—and the intolerable, rising scream, after a time, was stilled.

Garry experienced one raging moment when he would have given his hope of life for the ability to talk to Horab face to face and in words that could penetrate the black one's brain. But he could not. He must use this girl as an interpreter, and he must give her words to say that would make this ugly beast pause. He must speak as she would speak; put words and sentences into her mouth that would reach the savage superstitions of the other.

He spoke slowly, and stared impressively into the dark, fear-filled eyes in the white face that bent above him. He must make the girl believe.

"Horab works magic," he told her. "Tell Horab that I, too, am a magician—a great magician—a greater one than Horab."

e waited an instant to hear the girl's words and the disdainful laughter from lips in a savage face thrust close to where he lay.

"Horab is truly a magician," said Luhra doubtfully; "he laughs at your magic. Horab's Tao is a strong Tao, wicked and powerful."[310]

"His Tao?" said Garry, and looked at the girl questioningly. He got the thought in her mind. "Oh, yes—his god, or devil."

He turned his head to stare straight into the grinning face whose wide, thin lips were twisted into a leering snarl. Garry had to summon all his power of will to hold the look that he gave his enemy and to laugh, in his turn, long and contemptuously. Another tremor shook the casket where he lay.

"Tell Horab," he ordered, while his eyes stared steadily into those of the savage king, "—tell Horab my Tao is stronger than his. My Tao is angry because I have been harmed; he is shaking the mountain. He will shake it down on Horab and crush out his life."

He continued to stare while he heard Luhra's voice, high with hope, and he saw a change of expression flicker across the black face, though Horab shouted a vehement reply.

Luhra was speaking to him. "Horab says the earth has shaken before; that it is not your Tao who shakes it. He asks for another sign."

Garry was not surprised. He had fired this shot at random; the tremor itself had suggested it. And now—

"Another sign!" Garry had to fight hard for self-control to keep from shouting the truth to this evil thing—to keep from telling him of the time that had passed, and of the world that was waiting for him. But that would never do: he must play upon this black one's superstitions. Let Horab once leave this cave with that devilish, soundless scream ringing in his ears and he, Garry Connell, was lost. And Luhra!—what hope for her out there?... The black hands were moving impatiently toward the machine....

Garry found himself speaking slowly—short sentences that Luhra quickly repeated. And something within him rose to frame words such as Garry Connell, man of the desert, would never have thought to speak—phrases that best might reach a savage, vicious mind.

e glanced once at the watch on his wrist. He did not feel the torture of the tight gold cord. He was thinking in terms of daylight, and of how much time had passed since he had seen the sun....

"Horab shall have a sign—a terrible sign," he said. "Death waits for Horab in the world outside, my Tao tells me. Horab shall die horribly. I see him choking in the hot sand. His tongue fills his mouth. The hot sun burns, and he is filled with fire. He tries to scream—to call upon his Tao—but he makes no sound.... And so shall Horab die."

The girl translated swiftly; the answer was a wild cry of rage from the black. He sprang beside the helpless man and his spear was raised high.

Garry felt the weight of Luhra's body thrown protectingly across him, and looked up to see murder in the savage, slitted eyes. "Tell Horab," he directed sharply, "that if be harms you or me the burning death is his! But—" He waited deliberately after Luhra had spoken, and he saw plainly the flicker of fear in the ugly face. Now was the time.

"Unbind my feet!" he ordered, and he put into his voice all the force and menace he could muster. "Take me to the outer world. Take your spear. If I do not speak truth, kill me there. My Tao will show you a sign; he will fill your heart with fear as it now is filled with evil. But, it may be I can save you. Unbind my feet! Be quick!"

Again he waited while Luhra spoke, and he cursed silently with the agony of waiting. To be playing a part, speaking these absurdly childish things, when what he wanted was his hand upon a gun or in a grip of death about that black throat! Yet he lay as still as if the vibrations of the bell were upon him, and his eyes held unwaveringly upon the savage face, until he felt the fumbling of hands about his feet....[311]

square-cut portal!—and beyond it a golden sun that shone through mists of purple and rose! Was he too late? Garry pressed forward in what would have been a clumsy run, but for the spear that had prodded him through all the long passage, and that warned now against attempted escape.

The brilliance and heat that struck him when he stepped, out into the open brought Garry in a flash from the world of horror and make-believe into the world he knew. He wanted to shout for sheer joy; but more than all else he wanted to leap at the ugly thing who stood blinking his eyes in the mouth of the cave.

The thought of escape was strong upon him, but the touch of a timid hand showed the folly of that. Luhra was beside him, her filmy lacework shining softly in the sun, to make more lovely the delicate flush beneath. Her eyes, shielded from the sun, were upon him with a look half hopeful, half despairing. No, he must see it through—go on with his play-acting—meet magic with magic. Horab had come out from the cave, and spear in hand he stood commandingly above them on a huge boulder. Yes, the magic must go on.

The harsh voice of the savage ripped out unintelligible words. Luhra translated. "It is changed," she said, "and Horab fears. But the water is there, and there is no burning death.... He says your Tao is weak."

Garry stared with thankful eyes across the blue expanse where a line of white marked ghostly breakers on a distant shore; where hills were reflected in the shimmering blue. But the sun was still above their tops, so he must spar for time—

"My Tao is strong," he said, and went on with whatever fantastic thoughts came into his mind. He was talking against time. He told of the new world his Tao had built, of men harnessing the lightning and flying through the air; of cannon that roared like the thunder and threw death and destruction upon those that the Tao would destroy.... And his eyes watched the slow descent of the dropping sun, while the figure above stirred impatiently and raised his spear.

"A sign!" Luhra was imploring. "He does not believe!"

The golden ball was touching now on a distant, purple peak. The amazing magic of the desert!—its moment had come! Garry indicated as best he could the phantom sea, so real, below.

"My Tao has spoken," he shouted: "watch! The waters shall be dried up; the seas shall become a desert of hot sand; the lands and waters that Horab knows shall be no more! There shall be no food for his stomach nor water for his lips where Horab wanders in torment.... Unless I save him."

e turned to stare at the vast mirage. He knew that the eyes of the others had followed his, and he knew that they saw the first change that crept over the land.

The blue that was so unmistakably a sea was dissolving; it seemed sucked into the sand. And, while yet the hot rays cast their lingering gold over mountain and plain, the seas faded and were gone ... and where they had been in unquestioned reality was only yellow sand that whirled hotly and drifted in the first breath of the coming night....

The towering figure above them stood rigid. Garry had found a sharp edge of rock, and sawed frantically upon it to cut the soft gold of the cords at his wrists. The one above them paid no heed; his eyes were held in horror of this silent death that swept across the world.

The hand that Garry extended was steady and cautious; his arm crept about the body of white and gold to draw the amazed and wondering girl silently into the open cave.

"Follow!" he ordered, and dashed headlong down the darkened way where an automatic was waiting for his eager fingers.

The pack was there, and he tore at[312] it with frenzied hands to grip at the pistol within. And there was also an open chest whose contents glittered in the green light, and whose weight was not too great for him to carry....

He had both chest and gun when he returned. The stumbling falls in his mad rush had not served to allay the hurts of his tortured body, nor still his raging fury. He called to Luhra as he ran—and realized that Luhra was gone. The chest fell forgotten at his feet as he rushed out; he shouted her name and cursed himself for leaving her.

ad the fascination of the outer world drawn her back? Had she trusted too greatly in the power of his Tao to shield her from harm? Connell could not know. He knew only that he saw her struggling in the grip of the long arms where the black one held her on an outthrust rock.

They were a hundred feet away, yet the black face beneath its pointed skull showed plainly its bestial fury as Garry sprang forward. With one motion the tall figure dashed the girl to the stone at his feet and raised his spear. He paused to laugh harshly at the man who rushed toward him—who could never reach him to stop the fatal thrust.

A threat, it might have been, to hold the attacker off, or a murderous intent to end now and forever this one captive's life: Garry did not wait to learn. And the hundred-foot distance that meant a hundred feet of safety to the savage was spanned by a stream of lead from a gun whose stabbing flashes cracked sharply upon the still air. The ringing clatter of a spear that fell among granite stones came thinly to Garry as he saw the black form of Horab, king of another day, spin dizzily from the rock on which he stood.

He had hit him—wounded him at least—and the firing of that wild fusillade might have emptied the magazine! Gary waited for nothing more, but gathered the limp body of the girl within his outstretched arms and carried her stumblingly across the welter of rocks on the boulder-strewn slope. Nor did he stop until he had gained the safety of open ground beyond the marks of the great slide.

he earth was shivering and weaving as he laid her down; a rock crashed sharply in the distance. Garry turned to retrace his steps and leap wildly from rock to rock toward the mouth of the cave in a granite cliff. And the metal chest was in his arms when he returned where Luhra waited.

The ground was alive with sickening motion, he was nauseated with earthquake sickness, but he gave thought only to his gun and the one cartridge that he found in the chamber. He steadied his arm upon a rock to take aim at a figure on a distant slope.

Horab had climbed back upon the rock. A lean figure and black, he was sharply outlined in the last rays of the setting sun; the target was clear beyond the pistol's sights. But the fingers of the grim-faced man refused to tighten upon the trigger.

Savage and cruel—a relic of a bygone age! He stood there, ludicrous and unreal in his stark black nakedness, his frayed robes of crimson whipping to tatters in the breeze. Yet he had forgotten his wounds—Horab was standing upright—and Garry's hand that held the pistol fell loosely at his side. The hate melted from his heart as he watched where Horab drew himself painfully erect.

A barbarous figure was Horab, and evil beyond redemption, yet there were not lacking the attributes of a king in the grotesque form whose head was still held high. The sun made flashing brilliance of the jewels on that distorted head, while he stared with hopeless, savage eyes across the changed world where he could have no part. His Tao had failed him; his enemy had struck him down; and now—

The rock that had been a rest for Garry's arm was swaying, and to his[313] ears came a rumble and groan. Sentinel Mountain, that had watched the ages pass, that had seen the oceans truly change to sand, protested again at this disturbance of its own long sleep.

Garry heard the coming of the masses from above; the crashing din was deadening to his ears. They were safe—and his eyes were upon a savage figure, black and tall, that stared and stared, silently, across a sea of yellow sand. He watched it, clear-cut, motionless—until it vanished beneath the roaring flood of rocks.

nd close in his arms there pressed the soft body of a trembling girl who touched his face and whispered: "Your Tao, my brave one, is strong. Hold me closely that he may count me as your friend."

His own whispered words, though differing somewhat, were a fervent echo of hers. He saw the rocky masses piled high where the mouth of a cave had been; and "Thank God!" Garry Connell said, "we got out of there in time!"

The casket of jewels lay neglected among the rocks: to-morrow would be time enough to salvage the wealth for which he had risked his life. He swept the girl into his arms, and the sun's last rays made golden splendor of his burden as he carried her across the broken stones.

His ranch showed far below him when he stopped, but the green of date palms had vanished under the last great sweep of rocks. Some few that remained made dark splotches among the shadows that were engulfing the world.

What did it matter? Miramar—"Beautiful Sea!" He laughed grimly at thought of how that sea had served him, but his eyes were tender in his tanned and blood-stained face.

Miramar could be restored. And it would be less lonely now....

robot chemist with an electric eye, radio brain and magnet hands functioned without human supervision in an improvised laboratory recently before members of the New York Electrical Society.

The automatic chemist performed several experiments. Its work was explained by William C. MacTavish, professor of chemistry at New York University, and was part of a program in which cold light was reproduced, a sample weighing a millionth of a gram analyzed, a photo-electric cell used to control analysis and new scientific apparatus demonstrated.

In his talk on "The Magic of Modern Chemistry," Professor MacTavish demonstrated the separation of para-hydrogen and ortho-hydrogen. In the micro-analysis of a millionth of a gram, Professor MacTavish exhibited in the micro-projector a ball of gold weighing one thousandth of a milligram (one twenty-eight millionth of an ounce), having a value of less than one ten-thousandth of a cent.

The robot chemist was the joint creation of Dr. H. M. Partridge and Professor Ralph H. Muller of the department of chemistry at New York University. In explaining what the automatic chemist can do, Professor MacTavish said:

"The ability of the automatic chemist to control chemical operations is due to its sensitivity to slight variations in color and light intensity. Its working parts are very simple. They consist of a standard light source, in this case an electric light, a photo-electric cell which detects differences in the amount of light impinging on it, a radio tube which amplifies the signal received from the photo-electric cell and which operates the relays controlling the automatic valves.

"Between the electric light and the photo-electric cell is placed a glass vessel holding an alkali that is to be neutralized. Above is a tube from which an acid passes, drop by drop, through an automatic valve, into the alkali. A small amount of chemical indicator added to the alkali maintains a red color in it until it is neutralized. When a sufficient amount of the acid has dropped into the alkali, the red color disappears, indicating complete neutralization.

"When the solution is colored red, an insufficient amount of lights gets through to the photo-electric cell. As the red color gradually diminishes, the amount of light passing through increases, and when the solution is entirely clear the light reaches a critical value which causes the photo-electric cell to pass a signal to the radio tube. This tube operates the relay which closes a valve and shuts off the supply of acid.

"Using a device of this sort to perform such operations around a laboratory will save a great deal of a chemist's time. Its electric eye is about 165 times as sensitive to differences in color as any human eye."

The fly landed with a thud on the center table.

The fly landed with a thud on the center table.

t was shortly after noon of December 31, 1960, when the series of weird and startling events began which took me into the tiny world of an atom of gold, beyond the vanishing point, beyond the range of even the highest-powered electric-microscope. My name is George Randolph. I was, that momentous afternoon, assistant chemist for the Ajax International Dye Company, with main offices in New York City.

It was twelve-twenty when the local exchange call-sorter announced Alan's connection from Quebec.

"You, George? Look here, we've got to have you up here at once. [315]Chateau Frontenac, Quebec. Will you come?"

I could see his face imaged in the little mirror on my desk; the anxiety, tenseness in his voice, was duplicated in his expression.

"Well—" I began.

"You must, George. Babs and I need you. See here—"

He tried at first to make it sound like an invitation for a New Year's Eve holiday. But I knew it was not that. Alan and Barbara Kent were my best friends. They were twins, eighteen years old. I felt that Alan would always be my best friend; but for Babs my hopes, longings, went far deeper, though as yet I had never brought myself to the point of telling her so.

"I'd like to come, Alan. But—"

"You must! George, I can't tell you over the public air. It's—I've seen him! He's diabolical! I know it now!"

Him! It could only mean, of all the world, one person!

"He's here!" he went on. "Near here. We've seen him to-day! I didn't want to tell you, but that's why we came. It seemed a long chance, but it's he, I'm positive!"[316]

I was staring at the image of Alan's eyes; it seemed that there was horror in them. And in his voice. "God, George, it's weird! Weird, I tell you. His looks—he—oh I can't tell you now! Only, come!"

was busy at the office in spite of the holiday season, but I dropped everything and went. By one o'clock that afternoon I was wheeling my little sport midge from its cage on the roof of the Metropole building, and went into the air.

It was a cold gray afternoon with the feel of coming snow. I made a good two hundred and fifty miles at first, taking the northbound through-traffic lane which to-day the meteorological conditions had placed at 6,200 feet altitude.

Flying is largely automatic. There was not enough traffic to bother me. The details of leaving the office so hastily had been too engrossing for thought of Alan and Babs. But now, in my little pit at the controls, my mind flung ahead. They had located him. That meant Franz Polter, for whom we had been searching nearly four years. And my memory went back into the past with vivid vision....

The Kents, four years ago, were living on Long Island. Alan and Babs were fourteen years old, and I was seventeen. Even then Babs represented to me all that was desirable in girlhood. I lived in a neighboring house that summer and saw them every day.

To my adolescent mind a thrilling mystery hung upon the Kent family. The mother was dead. Dr. Kent, father of Alan and Babs, maintained a luxurious home, with only a housekeeper and and no other servant. Dr. Kent was a retired chemist. He had, in his home, a chemical laboratory in which he was working upon some mysterious problem. His children did not know what it was, nor, of course, did I. And none of us had ever been in the laboratory, except that when occasion offered we stole surreptitious peeps.

I recall Dr. Kent as a kindly, iron-gray haired gentleman. He was stern with the discipline of his children; but he loved them, and was indulgent in a thousand ways. They loved him; and I, an orphan, began looking upon him almost as a father. I was interested in chemistry. He knew it, and did his best to help and encourage me in my studies.

here came an afternoon in the summer of 1956, when arriving at the Kent house, I ran upon a startling scene. The only other member of the household was a young fellow of twenty-five, named Franz Polter. He was a foreigner, born, I understood, in one of the Balkan Protectorates; and he was here, employed by Dr. Kent as laboratory assistant. He had been with the Kents, at this time, two years. Alan and Babs did not like him, nor did I. He must have been a clever, skilful chemist. No doubt he was. But in aspect he was, to us, repulsive. A hunchback, with a short thick body; dangling arms that suggested a gorilla; barrel chest; a lump set askew on his left shoulder, and his massive head planted down with almost no neck. His face was rugged in feature; a wide mouth, a high-bridged heavy nose; and above the face a great shock of wavy black hair. It was an intelligent face; in itself, not repulsive.

But I think we all three feared Franz Polter. There was always something sinister about him, quite apart from his deformity.

I came, that afternoon, upon Babs and Polter under a tree on the Kent lawn. Babs, at fourteen with her long black braids down her back, bare-legged and short-skirted in a summer sport costume, was standing against the tree with Polter facing her. They were about of a height. To my youthful imaginative mind rose the fleeting picture of a young girl in a forest menaced by a gorilla.

I came upon them suddenly. I heard Polter say:[317]

"But I lof you, And you are almos' a woman. Some day you lof me."

He put out his thick hand and gripped her shoulder. She tried to twist away. She was frightened, but she laughed.

"You—you're crazy!"

He was suddenly holding her in his arms, and she was fighting him. I dashed forward. Babs was always a spunky sort of girl. In spite of her fear now, she kept on laughing, and she shouted:

"You—let me go, you—hunchback!"

He did let her go; but in a frenzy of rage he hauled back his hand and struck her in the face. I was upon him the next second. I had him down on the lawn, punching him; but though at seventeen I was a reasonably husky lad, the hunchback with his thick, hairy gorilla arms proved much stronger. He heaved me off. And then the commotion brought Alan. Without waiting to find out what the trouble was, he jumped on Polter. Between us, I think we would have beaten him pretty badly. But the housekeeper summoned Dr. Kent and the fight was over.

olter left for good within an hour. He did not speak to any of us. But I saw him as he put his luggage into the taxi which Dr. Kent had summoned. I was standing silently nearby with Babs and Alan. The look he flung us as he drove away carried an unmistakable menace—the promise of vengeance. And I think now that in his warped and twisted mind he was telling himself that he would some day make Babs regret that she had laughed at his love.

What happened that night none of us ever knew. Dr. Kent worked late in his laboratory; he was there when Alan and Babs and the housekeeper went to bed. He had written a note to Alan; it was found on his desk in a corner of the laboratory next morning, addressed in care of the family lawyer to be given Alan in the event his father died. It said very little. Described a tiny fragment of gold quartz rock the size of a walnut which would be found under the giant microscope in the laboratory; and told Alan to give it to the American Scientific Society to be guarded and watched very carefully.

This note was found, but Dr. Kent had vanished! There had been a midnight marauder. The laboratory was on the lower floor of the house. Through one of its open windows, so the police said, an intruder had entered. There was evidence of a struggle, but it must have been short, and neither Babs, Alan, the housekeeper nor any of the neighbors heard anything amiss. And the fragment of golden quartz was gone!

The police investigation came to nothing. Polter was found in New York. He withstood the police questions. There was nothing except suspicion upon which he could be held, and he was finally released. Immediately, he disappeared.

Neither Alan, Babs nor I saw Polter again. Dr. Kent had never been heard from to this day, four years later when I flew to join the twins in Quebec. And now Alan had told me that Polter was up there! We had never ceased to believe that Dr. Kent was alive, and that Polter was the midnight marauder. And as we grew older, we began to search for Polter. It seemed to us that now we were older, if we could once get our hands on him, we could drag from him the truth in which the police had failed.

he call of a traffic director in mid-Vermont brought me back from these vivid thoughts. My buzzer was clanging; a peremptory halting-signal day-beam came darting up at me from below. It caught me and clung: I shouted down at it.

"What's the matter?" I gave my name and number and all the details in a breath. Above everything I had no wish to be halted now. "What's the matter? I haven't done anything wrong."[318]

"The hell you haven't," the director roared. "Come down to three thousand. That lane's barred."

I dove obediently and his beam followed me. "Once more like that, young fellow—" But he went busy with somebody else and I didn't hear the end of his threat.

I crossed into Maine in mid-afternoon. Twilight was upon me. The sky was solid lead. The landscape all up through here was gray-white with snow in the gathering darkness. I passed the city of Jackman, crossing full over it to take no chances of annoying the border officials; and a few miles further, I dropped to the glaring lights of the International Inspection Field. The formalities were soon finished. I was ready to take-away when Alan rushed at me.

"George! I thought I could connect here." He gripped me. He was wild-eyed, incoherent. He waved his taxiplane away. "I'm going back with my friend. George. I can't—I don't know what's happened to her. She's gone, now!"

"Who's gone? Babs?"

"Yes." He pushed me into my plane and climbed in after me. "Don't talk. Get us up! I'll tell you then. I shouldn't have left."

When we were up in the air, I swung on him. "What are you talking about? Babs gone?"

I could feel myself shuddering with a nameless horror.

"I don't know what I'm talking about, George. I'm about crazy. The Quebec police think I am, anyway. I been raising hell with them for an hour. Babs is gone. I can't find her. I don't know where she is."

e finally calmed down enough to tell me. Shortly after his radiophone to me in New York, he had missed Babs. They had had lunch in the huge hotel and then walked on the Dufferin Terrace—the famous promenade outside looking down over the lower city, the great sweep of the St. Lawrence River and the gray-white distant Laurentian mountains.

"I was to meet her inside. I went in ahead of her. But she didn't come. I went back to the terrace and she was gone. Wasn't in our rooms. Nor the lobby—nor anywhere."

But it was early afternoon, in the public place of a civilized city. In the daylight of the Dufferin Terrace, beside the long ice toboggan slide, under the gaze of skaters on the ice-rink and several hundred holiday merrymakers, a young girl could hardly be murdered, or forcibly abducted, without attracting some attention! The Quebec police thought the young American unduly excited over his sister, who was missing only an hour. They would do what they could, if by dark she had not rejoined him. They suggested that doubtless the young lady had gone shopping.

"Maybe she did," I agreed. But in my heart, I felt differently. "She'll be waiting for us in the hotel when we get there, Alan."

"But I'm telling you we saw Polter this morning. He lives here—not thirty miles from Quebec. We saw him on the terrace after breakfast. Recognized him at once."

"Did he see you?"

"I don't know. He was lost in the crowd in a minute. But I asked a young French fellow who it was. He knew him. Told me, Frank Raskor. That's the name he wears now. He's a famous man up here—well known, immensely rich. I don't know if he saw us or not. What a fool I was to leave Babs alone, even for a minute!"

We were speeding over a white-clad valley with a little frozen river winding down its middle. Almost full night had come. The leaden sky was low above us. It began snowing. The lights of the small villages along the river were barely visible.

"Can you land us, Alan?"

"Yes, surely. Municipal field just beyond the Citadel. We can get to the hotel in five minutes. Good landing lights."[319]

t was a flight of only half an hour. During it, Alan told me about Polter. The hunchback, known now as Frank Rascor, owned a mine in the Laurentides, some thirty miles from Quebec City—a fabulously productive mine of gold. It was an anomaly that gold should be produced in this region. No vein o£ gold-bearing rock had been found, except the one on Polter's property. Alan had seen a newspaper account of the strangeness of it; and just upon the chance had come to Quebec, seen Frank Rascor on the Dufferin Terrace, and recognized him as Polter.

Again my thoughts went back into the past. Had Polter stolen that missing fragment of golden quartz the size of a walnut which had been beneath Dr. Kent's microscope? We always thought so. Dr. Kent had some secret, some great problem upon which he was working. Polter, his assistant, had evidently known, or partially known, its details. And now, four years later, Polter was immensely rich, with a "gold mine" in mountains where there was no other such evidence of gold!

I seemed to see some connection. Alan, I knew, was groping with a dim idea, so strange he hardly dared voice it.

"I tell you, it's weird, George. The sight of him. Polter—heavens, one couldn't mistake that hunchback—and his face, his features, just the same as when we knew him."

"Then what's weird?? I demanded.

"His age." There was a queer solemn hush in Alan's voice. "George, when we knew Polter, he was about twenty-five, wasn't he? Well, that was four years ago. But he isn't twenty-nine now! I swear it's the same man—but he isn't around thirty. Don't ask me what I'm talking about. I don't know. But he isn't thirty. He's nearer fifty! Unnatural! Weird! I felt it, and so did Babs, just that brief look we had at him."

I did not answer. My attention was on managing the plane. The lights of Sevis were under us. Beyond the city cliffs the St. Lawrence lay in its deep valley; and the Quebec lights, the light-dotted ramparts with the terrace and the great fortress-like hotel showed across the river.

"Better take the stick, Alan. I don't know where the field is. And don't you worry about Babs. She'll be back by now."

ut she was not. We went to the two connecting rooms in the tower of the hotel which Alan and Babs had engaged. We inquired with half a dozen phone-calls. No one had seen or heard from her. The Quebec police were sending a man up to talk to Alan.

"Well, we won't be here," Alan called to me. He was standing by the window in Bab's room; he was trembling too much to use the phone. I hung up the receiver and went through the connecting door to join him.

Bab's room! It sent a pang through me. A few of her garments were lying around. A negligee was laid out on the dainty little bed. A velvet boudoir doll—she had always loved them—stood on the dresser. Upon this hotel room, in a day, she had impressed her personality. Her perfume was in the air. And now she was gone.

"We won't be here," Alan was repeating. He gripped me at the window. "Look!" In his hand was an ugly-looking, smokeless, soundless automatic of the Essen type. "And I've got another, for you. Brought them up with me."

His face was white and drawn, but his hands abruptly were steady. The tremble was gone out of his voice.

"I'm going after him. George! Now! Understand that? Now! His place is only thirty miles from here, out there in the mountains. You can see it in the daylight—a wall around his property and a stone castle which he built in the middle of it. A gold mine? Hell!"