Title: Tom and Maggie Tulliver

Adapter: Anonymous

Author: George Eliot

Release date: October 17, 2009 [eBook #30273]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| I. | TOM MUST GO TO SCHOOL |

| II. | THE CHOICE OF A SCHOOL |

| III. | TOM COMES HOME |

| IV. | ALL ABOUT A JAM PUFF |

| V. | THE FAMILY PARTY |

| VI. | THE MAGIC MUSIC |

| VII. | MAGGIE IS VERY NAUGHTY |

| VIII. | MAGGIE AND THE GIPSIES |

| IX. | THE GIPSY QUEEN ABDICATES |

| X. | TOM AT SCHOOL |

| XI. | THE NEW SCHOOLFELLOW |

| XII. | THE DUKE OF WELLINGTON |

| XIII. | PHILIP AND MAGGIE |

"What I want, you know," said Mr. Tulliver of Dorlcote Mill—"what I want is to give Tom a good eddication. That was what I was thinking of when I gave notice for him to leave th' academy at Lady Day. I meant to put him to a downright good school at Midsummer.

"The two years at th' academy 'ud ha' done well enough," the miller went on, "if I'd meant to make a miller and farmer of him like myself. But I should like Tom to be a bit of a scholard, so as he might be up to the tricks o' these fellows as talk fine and write with a flourish. It 'ud be a help to me wi' these lawsuits and things."

Mr. Tulliver was speaking to his wife, a blond, comely woman in a fan-shaped cap.

"Well, Mr. Tulliver," said she, "you know best. But hadn't I better kill a couple o' fowl, and have th' aunts and uncles to dinner next week, so as you may hear what Sister Glegg and Sister Pullet have got to say about it? There's a couple o' fowl wants killing!"

"You may kill every fowl i' the yard if you like, Bessy, but I shall ask neither aunt nor uncle what I'm to do wi' my own lad," said Mr. Tulliver.

"Dear heart!" said Mrs. Tulliver, "how can you talk so, Mr. Tulliver? However, if Tom's to go to a new school, I should like him to go where I can wash him and mend him; else he might as well have calico as linen, for they'd be one as yallow as th' other before they'd been washed half a dozen times. And then, when the box is goin' backards and forrards, I could send the lad a cake, or a pork-pie, or an apple."

"Well, well, we won't send him out o' reach o' the carrier's cart, if other things fit in," said Mr. Tulliver. "But you mustn't put a spoke i' the wheel about the washin' if we can't get a school near enough. But it's an uncommon puzzling thing to know what school to pick."

Mr. Tulliver paused a minute or two, and dived with both hands into his pockets, as if he hoped to find some idea there. Then he said, "I know what I'll do, I'll talk it over wi' Riley. He's coming to-morrow."

"Well, Mr. Tulliver, I've put the sheets out for the best bed, and Kezia's got 'em hanging at the fire. They aren't the best sheets, but they're good enough for anybody to sleep in, be he who he will."

As Mrs. Tulliver spoke she drew a bright bunch of keys from her pocket, and singled out one, rubbing her thumb and finger up and down it with a placid smile while she looked at the clear fire.

"I think I've hit it, Bessy," said Mr. Tulliver, after a short silence. "Riley's as likely a man as any to know o' some school; he's had schooling himself, an' goes about to all sorts o' places—auctioneering and vallyin' and that. I want Tom to be such a sort o' man as Riley, you know—as can talk pretty nigh as well as if it was all wrote out for him, and a good solid knowledge o' business too."

"Well," said Mrs. Tulliver, "so far as talking proper, and knowing everything, and walking with a bend in his back, and setting his hair up, I shouldn't mind the lad being brought up to that. But them fine-talking men from the big towns mostly wear the false shirt-fronts; they wear a frill till it's all a mess, and then hide it with a bib;—I know Riley does. And then, if Tom's to go and live at Mudport, like Riley, he'll have a house with a kitchen hardly big enough to turn in, an' niver get a fresh egg for his breakfast, an' sleep up three pair o' stairs—or four, for what I know—an' be burnt to death before he can get down."

"No, no," said Mr. Tulliver; "I've no thoughts of his going to Mudport: I mean him to set up his office at St. Ogg's, close by us, an' live at home. I doubt Tom's a bit slowish. He takes after your family, Bessy."

"Yes, that he does," said Mrs. Tulliver; "he's wonderful for liking a deal o' salt in his broth. That was my brother's way, and my father's before him."

"It seems a bit of a pity, though," said Mr. Tulliver, "as the lad should take after the mother's side instead o' the little wench. The little un takes after my side, now: she's twice as 'cute as Tom."

"Yes, Mr. Tulliver, and it all runs to naughtiness. How to keep her in a clean pinafore two hours together passes my cunning. An' now you put me i' mind," continued Mrs. Tulliver, rising and going to the window, "I don't know where she is now, an' it's pretty nigh tea-time. Ah, I thought so—there she is, wanderin' up an' down by the water, like a wild thing. She'll tumble in some day."

Mrs. Tulliver rapped the window sharply, beckoned, and shook her head.

"You talk o' 'cuteness, Mr. Tulliver," she said as she sat down; "but I'm sure the child's very slow i' some things, for if I send her upstairs to fetch anything, she forgets what she's gone for."

"Pooh, nonsense!" said Mr. Tulliver. "She's a straight, black-eyed wench as anybody need wish to see; and she can read almost as well as the parson."

"But her hair won't curl, all I can do with it, and she's so franzy about having it put i' paper, and I've such work as never was to make her stand and have it pinched with th' irons."

"Cut it off—cut it off short," said the father rashly.

"How can you talk so, Mr. Tulliver? She's too big a gell—gone nine, and tall of her age—to have her hair cut short.—Maggie, Maggie," continued the mother, as the child herself entered the room, "where's the use o' my telling you to keep away from the water? You'll tumble in and be drownded some day, and then you'll be sorry you didn't do as mother told you."

Maggie threw off her bonnet. Now, Mrs. Tulliver, desiring her daughter to have a curled crop, had had it cut too short in front to be pushed behind the ears; and as it was usually straight an hour after it had been taken out of paper, Maggie was incessantly tossing her head to keep the dark, heavy locks out of her gleaming black eyes.

"Oh dear, oh dear, Maggie, what are you thinkin' of, to throw your bonnet down there? Take it upstairs, there's a good gell, an' let your hair be brushed, an' put your other pinafore on, an' change your shoes—do, for shame; an' come and go on with your patchwork, like a little lady."

"O mother," said Maggie in a very cross tone, "I don't want to do my patchwork."

"What! not your pretty patchwork, to make a counterpane for your Aunt Glegg?"

"It's silly work," said Maggie, with a toss of her mane—"tearing things to pieces to sew 'em together again. And I don't want to sew anything for my Aunt Glegg; I don't like her."

Exit Maggie, drawing her bonnet by the string, while Mr. Tulliver laughs audibly.

"I wonder at you as you'll laugh at her, Mr. Tulliver," said the mother. "An' her aunts will have it as it's me spoils her."

Mr. Riley, who came next day, was a gentleman with a waxen face and fat hands. He talked with his host for some time about the water supply to Dorlcote Mill. Then after a short silence Mr. Tulliver changed the subject.

"There's a thing I've got i' my head," said he at last, in rather a lower tone than usual, as he turned his head and looked at his companion.

"Ah!" said Mr. Riley, in a tone of mild interest.

"It's a very particular thing," Mr. Tulliver went on; "it's about my boy Tom."

At the sound of this name Maggie, who was seated on a low stool close by the fire, with a large book open on her lap, shook her heavy hair back and looked up eagerly.

"You see, I want to put him to a new school at Midsummer," said Mr. Tulliver. "He's comin' away from the 'cademy at Lady Day, an' I shall let him run loose for a quarter; but after that I want to send him to a downright good school, where they'll make a scholard of him."

"Well," said Mr. Riley, "there's no greater advantage you can give him than a good education."

"I don't mean Tom to be a miller and farmer," said Mr. Tulliver; "I see no fun i' that. Why, if I made him a miller, he'd be expectin' to take the mill an' the land, an' a-hinting at me as it was time for me to lay by. Nay, nay; I've seen enough o' that wi' sons."

These words cut Maggie to the quick. Tom was supposed capable of turning his father out of doors! This was not to be borne; and Maggie jumped up from her stool, forgetting all about her heavy book, which fell with a bang within the fender, and going up between her father's knees said, in a half-crying, half-angry voice,—

"Father, Tom wouldn't be naughty to you ever; I know he wouldn't."

"What! they mustn't say any harm o' Tom, eh?" said Mr. Tulliver, looking at Maggie with a twinkling eye. Then he added gently, "Go, go and see after your mother."

"Did you ever hear the like on't?" said Mr. Tulliver as Maggie retired. "It's a pity but what she'd been the lad."

Mr. Riley laughed, took a pinch of snuff, and said,—

"But your lad's not stupid, is he?" said Mr. Riley. "I saw him, when I was here last, busy making fishing-tackle; he seemed quite up to it."

"Well, he isn't stupid. He's got a notion o' things out o' door, an' a sort o' common sense, and he'll lay hold o' things by the right handle. But he's slow with his tongue, you see, and he reads but poorly, and can't abide the books, and spells all wrong, they tell me, an' you never hear him say 'cute things like the little wench. Now, what I want is to send him to a school where they'll make him a bit nimble with his tongue and his pen, and make a smart chap of him."

"You're quite in the right of it, Tulliver," observed Mr. Riley. "Better spend an extra hundred or two on your son's education than leave it him in your will."

"I dare say, now, you know of a school as 'ud be just the thing for Tom," said Mr. Tulliver.

Mr. Riley took a pinch of snuff, and waited a little before he said,—

"I know of a very fine chance for any one that's got the necessary money, and that's what you have, Tulliver. But if any one wanted his boy to be placed under a first-rate fellow, I know his man. He's an Oxford man, and a parson. He's willing to take one or two boys as pupils to fill up his time. The boys would be quite of the family—the finest thing in the world for them—under Stelling's eye continually."

"But do you think they'd give the poor lad twice o' pudding?" said Mrs. Tulliver, who was now in her place again.

"And what money 'ud he want?" said Mr. Tulliver.

"Stelling is moderate in his terms; he's not a grasping man," said Mr. Riley. "I've no doubt he'd take your boy at a hundred. I'll write to him about it if you like."

Mr. Tulliver rubbed his knees, and looked at the carpet.

"But belike he's a bachelor," observed Mrs. Tulliver, "an' I've no opinion o' house-keepers. It 'ud break my heart to send Tom where there's a housekeeper, an' I hope you won't think of it, Mr. Tulliver."

"You may set your mind at rest on that score, Mrs. Tulliver," said Mr. Riley, "for Stelling is married to as nice a little woman as any man need wish for a wife. There isn't a kinder little soul in the world."

"Father," broke in Maggie, who had stolen to her father's elbow again, listening with parted lips, while she held her doll topsy-turvy, and crushed its nose against the wood of the chair—"father, is it a long way off where Tom is to go? Shan't we ever go to see him?"

"I don't know, my wench," said the father tenderly. "Ask Mr. Riley; he knows."

Maggie came round promptly in front of Mr. Riley, and said, "How far is it, please sir?"

"Oh, a long, long way off," that gentleman answered. "You must borrow the seven-leagued boots to get to him."

"That's nonsense!" said Maggie, tossing her head and turning away with the tears springing to her eyes.

"Hush, Maggie, for shame of you, chattering so," said her mother. "Come and sit down on your little stool, and hold your tongue, do. But," added Mrs. Tulliver, who had her own alarm awakened, "is it so far off as I couldn't wash him and mend him?"

"About fifteen miles, that's all," said Mr. Riley. "You can drive there and back in a day quite comfortably. Or—Stelling is a kind, pleasant man—he'd be glad to have you stay."

"But it's too far off for the linen, I doubt," said Mrs. Tulliver sadly.

Tom was to arrive early one afternoon, and there was another fluttering heart besides Maggie's when it was late enough for the sound of the gig wheels to be expected; for if Mrs. Tulliver had a strong feeling, it was fondness for her boy.

At last the sound came, and in spite of the wind, which was blowing the clouds about, and was not likely to respect Mrs. Tulliver's curls and cap-strings, she came and stood outside the door with her hand on Maggie's head.

"There he is, my sweet lad! But he's got never a collar on; it's been lost on the road, I'll be bound, and spoilt the set!"

Mrs. Tulliver stood with her arms open; Maggie jumped first on one leg and then on the other; while Tom stepped down from the gig, and said, "Hallo, Yap! what, are you there?"

Then he allowed himself to be kissed willingly enough, though Maggie hung on his neck in rather a strangling fashion, while his blue eyes wandered towards the croft and the lambs and the river, where he promised himself that he would begin to fish the first thing to-morrow morning. He was a lad with light brown hair, cheeks of cream and roses, and full lips.

"Maggie," said Tom, taking her into a corner as soon as his mother was gone out to examine his box, "you don't know what I've got in my pockets," nodding his head up and down as a means of rousing her sense of mystery.

"No," said Maggie. "How stodgy they look, Tom! Is it marls (marbles) or cob-nuts?" Maggie's heart sank a little, because Tom always said it was "no good" playing with her at those games, she played so badly.

"Marls! no. I've swopped all my marls with the little fellows; and cobnuts are no fun, you silly—only when the nuts are green. But see here!" He drew something out of his right-hand pocket.

"What is it?" said Maggie in a whisper. "I can see nothing but a bit of yellow."

"Why, it's a new— Guess, Maggie!"

"Oh, I can't guess, Tom," said Maggie impatiently.

"Don't be a spitfire, else I won't tell you," said Tom, thrusting his hand back into his pocket.

"No, Tom," said Maggie, laying hold of the arm that was held stiffly in the pocket. "I'm not cross, Tom; it was only because I can't bear guessing. Please be good to me."

Tom's arm slowly relaxed, and he said, "Well, then, it's a new fish-line—'two new uns—one for you, Maggie, all to yourself. I wouldn't go halves in the toffee and gingerbread on purpose to save the money; and Gibson and Spouncer fought with me because I wouldn't. And here's hooks; see here! I say, won't we go and fish to-morrow down by Round Pond? And you shall catch your own fish, and put the worms on, and everything. Won't it be fun!"

Maggie's answer was to throw her arms round Tom's neck and hug him, and hold her cheek against his without speaking, while he slowly unwound some of the line, saying, after a pause,—

"Wasn't I a good brother, now, to buy you a line all to yourself? You know, I needn't have bought it if I hadn't liked!"

"Yes, very, very good. I do love you, Tom."

Tom had put the line back in his pocket, and was looking at the hooks one by one, before he spoke again.

"And the fellows fought me because I wouldn't give in about the toffee."

"Oh dear! I wish they wouldn't fight at your school, Tom. Didn't it hurt you?"

"Hurt me? No," said Tom, putting up the hooks again. Then he took out a large pocket-knife, and slowly opened the largest blade and rubbed his finger along it. At last he said,—

"I gave Spouncer a black eye, I know—that's what he got by wanting to leather me; I wasn't going to go halves because anybody leathered me."

"Oh, how brave you are, Tom! I think you're like Samson. If there came a lion roaring at me, I think you'd fight him; wouldn't you, Tom?"

"How can a lion come roaring at you, you silly thing? There's no lions—only in the shows."

"No; but if we were in the lion countries—I mean, in Africa, where it's very hot—the lions eat people there. I can show it you in the book where I read it."

"Well, I should get a gun and shoot him."

"But if you hadn't got a gun. We might have gone out, you know, not thinking, just as we go fishing; and then a great lion might run towards us roaring, and we couldn't get away from him. What should you do, Tom?"

Tom paused, and at last turned away, saying, "But the lion isn't coming. What's the use of talking?"

"But I like to fancy how it would be," said Maggie, following him. "Just think what you would do, Tom."

"Oh, don't bother, Maggie! you're such a silly. I shall go and see my rabbits."

Upon this Maggie's heart began to flutter with fear, for she had bad news for Tom. She dared not tell the sad truth at once, but she walked after Tom in trembling silence as he went out.

"Tom," she said timidly, when they were out of doors, "how much money did you give for your rabbits?"

"Two half-crowns and a sixpence," said Tom promptly.

"I think I've got a great deal more than that in my steel purse upstairs. I'll ask mother to give it you."

"What for?" said Tom. "I don't want your money, you silly thing. I've got a great deal more money than you, because I'm a boy."

"Well, but, Tom, if mother would let me give you two half-crowns and a sixpence out of my purse to put into your pocket and spend, you know, and buy some more rabbits with it."

"More rabbits? I don't want any more."

"Oh, but, Tom, they're all dead!"

Tom stopped, and turned round towards Maggie. "You forgot to feed 'em, then, and Harry forgot?" he said, his colour rising for a moment. "I'll pitch into Harry—I'll have him turned away. And I don't love you, Maggie. You shan't go fishing with me to-morrow. I told you to go and see the rabbits every day." He walked on again.

"Yes, but I forgot; and I couldn't help it, indeed, Tom. I'm so very sorry," said Maggie, while the tears rushed fast.

"You're a naughty girl," said Tom severely, "and I'm sorry I bought you the fish-line. I don't love you."

"O Tom, it's very cruel," sobbed Maggie. "I'd forgive you if you forgot anything—I wouldn't mind what you did—I'd forgive you and love you."

"Yes, you're a silly; but I never do forget things—I don't."

"Oh, please forgive me, Tom; my heart will break," said Maggie, shaking with sobs, clinging to Tom's arm, and laying her wet cheek on his shoulder.

Tom shook her off. "Now, Maggie, you just listen. Aren't I a good brother to you?"

"Ye-ye-es," sobbed Maggie.

"Didn't I think about your fish-line all this quarter, and mean to buy it, and saved my money o' purpose, and wouldn't go halves in the toffee, and Spouncer fought me because I wouldn't?"

"Ye-ye-es—and I—lo-lo-love you so, Tom."

"But you're a naughty girl. Last holidays you licked the paint off my lozenge-box; and the holidays before that you let the boat drag my fish-line down when I'd set you to watch it, and you pushed your head through my kite, all for nothing."

"But I didn't mean," said Maggie; "I couldn't help it."

"Yes, you could," said Tom, "if you'd minded what you were doing. And you're a naughty girl, and you shan't go fishing with me to-morrow."

With this Tom ran away from Maggie towards the mill, meaning to greet Luke there, and complain to him of Harry.

"Oh, he is cruel!" Maggie sobbed aloud. She would stay up in the attic and starve herself—hide herself behind the tub, and stay there all night; and then they would all be frightened, and Tom would be sorry.

Thus Maggie thought in the pride of her heart, as she crept behind the tub; but presently she began to cry again at the idea that they didn't mind her being there.

Meanwhile, Tom was too much interested in his talk with Luke, and in going the round of the mill, to think of Maggie at all. But when he had been called in to tea, his father said, "Why, where's the little wench?" And Mrs. Tulliver, almost at the same moment, said, "Where's your little sister?"

"I don't know," said Tom. He didn't want to "tell" of Maggie, though he was angry with her; for Tom Tulliver was a lad of honour.

"What! hasn't she been playing with you all this while?" said the father. "She'd been thinking o' nothing but your coming home."

"I haven't seen her this two hours," says Tom.

"Goodness heart! she's got drownded," exclaimed Mrs. Tulliver, rising from her seat and running to the window.

"Nay, nay, she's none drownded," said Mr. Tulliver.—"You've been naughty to her, I doubt, Tom?"

"I'm sure I haven't, father," said Tom quickly. "I think she's in the house."

"Perhaps up in that attic," said Mrs. Tulliver, "a-singing and talking to herself, and forgetting all about meal-times."

"You go and fetch her down, Tom," said Mr. Tulliver, rather sharply. "And be good to her, do you hear? Else I'll let you know better."

Maggie, who had taken refuge in the attic, knew Tom's step, and her heart began to beat with the shock of hope. But he only stood still on the top of the stairs and said, "Maggie, you're to come down." Then she rushed to him and clung round his neck, sobbing, "O Tom, please forgive me! I can't bear it. I will always be good—always remember things. Do love me—please, dear Tom?" And the boy quite forgot his desire to punish her as much as she deserved; he actually began to kiss her in return, and say,—

"Don't cry, then, Magsie; here, eat a bit o' cake."

Maggie's sobs began to subside, and she put out her mouth for the cake and bit a piece; and then Tom bit a piece, just for company, and they ate together, and rubbed each other's cheeks and brows and noses together while they ate like two friendly ponies.

"Come along, Magsie, and have tea," said Tom at last.

So ended the sorrows of this day, and the next morning Maggie was to be seen trotting out with her own fishing-rod in one hand and a handle of the basket in the other. She had told Tom, however, that she should like him to put the worms on the hook for her.

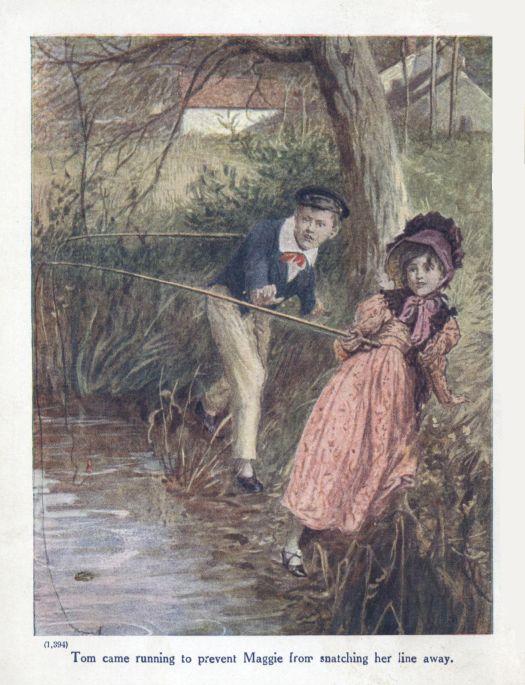

They were on their way to the Round Pool—that wonderful pool which the floods had made a long while ago. The sight of the old spot always heightened Tom's good-humour, and he opened the basket and prepared their tackle. He threw Maggie's line for her, and put the rod into her hand. She thought it probable that the small fish would come to her hook, and the large ones to Tom's. But after a few moments she had forgotten all about the fish, and was looking dreamily at the glassy water, when Tom said, in a loud whisper, "Look, look, Maggie!" and came running to prevent her from snatching her line away.

Maggie was frightened lest she had been doing something wrong, as usual; but presently Tom drew out her line and brought a large tench bouncing out upon the grass.

Tom was excited.

"O Magsie! you little duck! Empty the basket."

Maggie did not know how clever she had been; but it was quite enough that Tom called her Magsie, and was pleased with her. There was nothing to mar her delight in the whispers and the dreamy silences, when she listened to the light dipping sounds of the rising fish, and the gentle rustling, as if the willows and the reeds and the water had their happy whisperings also. Maggie thought it would make a very nice heaven to sit by the pool in that way, and never be scolded. She never knew she had a bite until Tom told her, it is true, but she liked fishing very much.

It was one of their happy mornings. They trotted along and sat down together, with no thought that life would ever change much for them. They would only get bigger and not go to school, and it would always be like the holidays; they would always live together, and be very, very fond of each other.

It was Easter week, and Mrs. Tulliver's cheese-cakes were even more light than usual, so that no season could have been better for a family party to consult Sister Glegg and Sister Pullet and Sister Deane about Tom's going to school.

On Wednesday, the day before the aunts and uncles were coming, Tom and Maggie made several inroads into the kitchen, where great preparations were being made, and were induced to keep aloof for a time only by being allowed to carry away some of the good things to eat.

"Tom," said Maggie, as they sat on the boughs of the elder tree, eating their jam puffs, "shall you run away to-morrow?"

"No," said Tom slowly—"no, I shan't."

"Why, Tom? Because Lucy's coming?"

"No," said Tom, opening his pocket-knife and holding it over the last jam puff, with his head on one side. "What do I care about Lucy? She's only a girl; she can't play at bandy."

"Is it the tipsy-cake, then?" said Maggie, while she leaned forward towards Tom with her eyes fixed on the knife.

"No, you silly; that'll be good the day after. It's the pudding. I know what the pudding's to be—apricot roll-up—oh, my buttons!"

With this the knife came down on the puff, and in a moment that dainty lay in two; but the result was not pleasing to Tom, and after a few moments' thought he said,—

"Shut your eyes, Maggie."

"What for?"

"You never mind what for. Shut 'em, when I tell you." Maggie obeyed.

"Now which'll you have, Maggie—right hand or left?"

"I'll have that with the jam run out," said Maggie, keeping her eyes shut to please Tom.

"Why, you don't like that, you silly. You may have it if it comes to you fair, but I shan't give it you without. Right or left?—you choose, now. Ha-a-a!" said Tom, as Maggie peeped. "You keep your eyes shut, now, else you shan't have any."

So Maggie shut her eyes quite close, till Tom told her to "say which," and then she said, "Left hand."

"You've got it," said Tom, in rather a bitter tone.

"What! the bit with the jam run out?"

"No; here, take it," said Tom firmly, handing the best piece to Maggie.

"Oh please, Tom, have it. I don't mind; I like the other. Please take this."

"No, I shan't," said Tom, almost crossly.

Maggie began to eat up her half puff with great relish; But Tom had finished his own first, and had to look on while Maggie ate her last morsel or two without noticing that Tom was looking at her.

"Oh, you greedy thing!" said Tom, when she had eaten the last morsel.

Maggie turned quite pale. "O Tom, why didn't you ask me?"

"I wasn't going to ask you for a bit, you greedy. You might have thought of it without, when you knew I gave you the best bit."

"But I wanted you to have it—you know I did," said Maggie, in an injured tone.

"Yes; but I wasn't going to do what wasn't fair. But if I go halves, I'll go 'em fair—only I wouldn't be a greedy."

With this Tom jumped down from his bough, and threw a stone with a "hoigh!" to Yap, who had also been looking on wistfully while the jam puff vanished.

Maggie sat still on her bough, and gave herself up to misery. She would have given the world not to have eaten all her puff, and to have saved some of it for Tom. Not but that the puff was very nice; but she would have gone without it many times over sooner than Tom should call her greedy and be cross with her.

And he had said he wouldn't have it; and she ate it without thinking. How could she help it? The tears flowed so plentifully that Maggie saw nothing around her for the next ten minutes; then she jumped from her bough to look for Tom. He was no longer near her, nor in the paddock behind the rickyard. Where was he likely to be gone, and Yap with him?

Maggie ran to the high bank against the great holly-tree, where she could see far away towards the Floss. There was Tom in the distance; but her heart sank again as she saw how far off he was on his way to the great river, and that he had another companion besides Yap—naughty Bob Jakin, whose task of frightening the birds was just now at a standstill.

It must be owned that Tom was fond of Bob's company. How could it be otherwise? Bob knew, directly he saw a bird's egg, whether it was a swallow's, or a tom-tit's, or a yellow-hammer's; he found out all the wasps' nests, and could set all sorts of traps; he could climb the trees like a squirrel, and had quite a magical power of finding hedgehogs and stoats; and every holiday-time Maggie was sure to have days of grief because Tom had gone off with Bob.

Well, there was no help for it. He was gone now, and Maggie could think of no comfort but to sit down by the holly, or wander lonely by the hedgerow, nursing her grief.

On the day of the family party Aunt Glegg was the first to arrive, and she was followed not long afterwards by Aunt Pullet and her husband.

Maggie and Tom, on their part, thought their Aunt Pullet tolerable, because she was not their Aunt Glegg. Tom always declined to go more than once during his holidays to see either of them. Both his uncles tipped him that once, of course; but at his Aunt Pullet's there were a great many toads to pelt in the cellar-area, so that he preferred the visit to her. Maggie disliked the toads, and dreamed of them horribly; but she liked her Uncle Pullet's musical snuff-box.

When Maggie and Tom came in from the garden with their father and their Uncle Glegg, they found that Aunt Deane and Cousin Lucy had also arrived. Maggie had thrown her bonnet off very carelessly, and coming in with her hair rough as well as out of curl, rushed at once to Lucy, who was standing by her mother's knee.

Lucy put up the neatest little rosebud mouth to be kissed. Everything about her was neat—her little round neck with the row of coral beads; her little straight nose, not at all snubby; her little clear eyebrows, rather darker than her curls to match her hazel eyes, which looked up with shy pleasure at Maggie, taller by the head, though scarcely a year older.

"O Lucy," burst out Maggie, after kissing her, "you'll stay with Tom and me, won't you?—Oh, kiss her, Tom."

Tom, too, had come up to Lucy, but he was not going to kiss her—no; he came up to her with Maggie because it seemed easier, on the whole, than saying, "How do you do?" to all those aunts and uncles.

"Heyday!" said Aunt Glegg loudly. "Do little boys and gells come into a room without taking notice o' their uncles and aunts? That wasn't the way when I was a little gell."

"Go and speak to your aunts and uncles, my dears," said Mrs. Tulliver. She wanted also to whisper to Maggie a command to go and have her hair brushed.

"Well, and how do you do? And I hope you're good children—are you?" said Aunt Glegg, in the same loud way, as she took their hands, hurting them with her large rings, and kissing their cheeks, much against their desire. "Look up, Tom, look up. Boys as go to boarding-schools should hold their heads up. Look at me now." Tom would not do so, and tried to draw his hand away. "Put your hair behind your ears, Maggie, and keep your frock on your shoulder."

Aunt Glegg always spoke to them in this loud way, as if she thought them quite deaf, or perhaps rather silly.

"Well, my dears," said Aunt Pullet sadly, "you grow wonderful fast.—I doubt they'll outgrow their strength," she added, looking over their heads at their mother. "I think the gell has too much hair. I'd have it thinned and cut shorter, sister, if I was you. It isn't good for her health. It's that as makes her skin so brown, I shouldn't wonder.—Don't you think so, Sister Deane?"

"I can't say, I'm sure, sister," said Mrs. Deane.

"No, no," said Mr. Tulliver, "the child's healthy enough—there's nothing ails her. There's red wheat as well as white, for that matter, and some like the dark grain best. But it 'ud be as well if Bessy 'ud have the child's hair cut, so as it 'ud lie smooth."

Maggie now wished to learn from her Aunt Deane whether she would leave Lucy behind to stay at the mill. Aunt Deane would hardly ever let Lucy come to see them, to Maggie's great regret.

"You wouldn't like to stay behind without mother, should you, Lucy?" she said to her little daughter.

"Yes, please, mother," said Lucy timidly, blushing very pink all over her little neck.

"Well done, Lucy!—Let her stay, Mrs. Deane, let her stay," said Mr. Deane, a large man, who held a silver snuff-box very tightly in his hand, and now and then exchanged a pinch with Mr. Tulliver.

"Maggie," said Mrs. Tulliver, beckoning Maggie to her, and whispering in her ear, as soon as this point of Lucy's staying was settled, "go and get your hair brushed—do, for shame. I told you not to come in without going to Martha first; you know I did."

"Tom, come out with me," whispered Maggie, pulling his sleeve as she passed him; and Tom followed willingly enough.

"Come upstairs with me, Tom," she whispered, when they were outside the door. "There's something I want to do before dinner."

"There's no time to play at anything before dinner," said Tom.

"Oh yes, there is time for this. Do come, Tom."

Tom followed Maggie upstairs into her mother's room, and saw her go at once to a drawer, from which she took a large pair of scissors.

"What are they for, Maggie?" said Tom.

Maggie answered by seizing her front locks and cutting them straight across the middle of her forehead.

"Oh, my buttons, Maggie, you'll catch it!" exclaimed Tom; "you'd better not cut any more off."

Snip went the great scissors again while Tom was speaking; and he couldn't help feeling it was rather good fun—Maggie would look so queer.

"Here, Tom, cut it behind for me," said Maggie, much excited.

"You'll catch it, you know," said Tom as he took the scissors.

"Never mind; make haste!" said Maggie, giving a little stamp with her foot. Her cheeks were quite flushed.

One delicious grinding snip, and then another and another. The hinder locks fell heavily on the floor, and soon Maggie stood cropped in a jagged, uneven manner.

"O Maggie!" said Tom, jumping round her, and slapping his knees as he laughed—"oh, my buttons, what a queer thing you look! Look at yourself in the glass."

Maggie felt an unexpected pang. She didn't want her hair to look pretty—she only wanted people to think her a clever little girl, and not to find fault with her untidy head. But now, when Tom began to laugh at her, the affair had quite a new aspect. She looked in the glass, and still Tom laughed and clapped his hands, while Maggie's flushed cheeks began to pale and her lips to tremble a little.

"O Maggie, you'll have to go down to dinner directly," said Tom. "Oh my!"

"Don't laugh at me, Tom," said Maggie, with an outburst of angry tears, stamping, and giving him a push.

"Now, then, spitfire!" said Tom. "What did you cut it off for, then? I shall go down; I can smell the dinner going in."

He hurried downstairs at once. Maggie could see clearly enough, now the thing was done, that it was very foolish, and that she should have to hear and think more about her hair than ever. As she stood crying before the glass she felt it impossible to go down to dinner and endure the severe eyes and severe words of her aunts, while Tom, and Lucy, and Martha, who waited at table, and perhaps her father and her uncles, would laugh at her—for if Tom had laughed at her, of course every one else would; and if she had only let her hair alone, she could have sat with Tom and Lucy, and had the apricot pudding and the custard!

"Miss Maggie, you're to come down this minute," said Kezia, entering the room after a few moments. "Lawks! what have you been a-doing? I niver see such a fright."

"Don't, Kezia," said Maggie angrily. "Go away!"

"But I tell you, you're to come down, miss, this minute; your mother says so," said Kezia, going up to Maggie and taking her by the hand to raise her from the floor, on which she had thrown herself.

"Get away, Kezia; I don't want any dinner," said Maggie, resisting Kezia's arm. "I shan't come."

"Oh, well, I can't stay. I've got to wait at dinner," said Kezia, going out again.

"Maggie, you little silly," said Tom, peeping into the room ten minutes later, "why don't you come and have your dinner? There's lots o' goodies, and mother says you're to come."

Oh, it was dreadful! Tom was so hard. If he had been crying on the floor, Maggie would have cried too. And there was the dinner, so nice, and she was so hungry. It was very bitter.

But Tom was not altogether hard. He was not inclined to cry, but he went and put his head near her and said in a lower, comforting tone,—

"Won't you come, then, Magsie? Shall I bring you a bit o' pudding when I've had mine, and a custard and things?"

"Ye-e-es," said Maggie, beginning to feel life a little more tolerable.

"Very well," said Tom, going away. But he turned again at the door and said, "But you'd better come, you know. There's the dessert—nuts, you know, and cowslip wine."

Slowly she rose from amongst her scattered locks, and slowly she made her way downstairs. Then she stood leaning with one shoulder against the frame of the dining-parlour door, peeping in as it stood ajar. She saw Tom and Lucy with an empty chair between them, and there were the custards on a side-table. It was too much. She slipped in and went towards the empty chair. But she had no sooner sat down than she wished herself back again.

Mrs. Tulliver gave a little scream as she saw her, and felt such a "turn" that she dropped the large gravy-spoon into the dish, with the most serious results to the table-cloth.

Mrs. Tulliver's scream made all eyes turn towards the same point as her own, and Maggie's cheeks and ears began to burn, while Uncle Glegg, a kind-looking, white-haired old gentleman, said,—

"Heyday! What little gell's this? Why, I don't know her. Is it some little gell you've picked up in the road, Kezia?"

"Why, she's gone and cut her hair herself," said Mr. Tulliver in an undertone to Mr. Deane, laughing with much enjoyment. "Did you ever know such a little hussy as it is?"

"Why, little miss, you've made yourself look very funny," said Uncle Pullet.

"Fie, for shame!" said Aunt Glegg in her loudest tone. "Little gells as cut their own hair should be whipped, and fed on bread and water—not come and sit down with their aunts and uncles."

"Ay, ay," said Uncle Glegg playfully "she must be sent to jail, I think, and they'll cut the rest off there, and make it all even."

"She's more like a gipsy nor ever," said Aunt Pullet in a pitying tone. "It's very bad luck, sister, as the gell should be so brown; the boy's fair enough. I doubt it'll stand in her way i' life, to be so brown."

"She's a naughty child, as'll break her mother's heart," said Mrs. Tulliver, with the tears in her eyes.

"Oh my, Maggie," whispered Tom, "I told you you'd catch it."

The child's heart swelled, and getting up from her chair she ran to her father, hid her face on his shoulder, and burst out into loud sobbing.

"Come, come, my wench," said her father soothingly, putting his arm round her, "never mind; you was i' the right to cut it off if it plagued you. Give over crying; father'll take your part."

"How your husband does spoil that child, Bessy," said Mrs. Glegg in a loud "aside" to Mrs. Tulliver. "It'll be the ruin of her if you don't take care. My father niver brought his children up so, else we should ha' been a different sort o' family to what we are."

Mrs. Tulliver took no notice of her sister's remark, but threw back her cap-strings and served the pudding in silence.

When the dessert came the children were told they might have their nuts and wine in the summer-house, since the day was so mild; and they scampered out among the budding bushes of the garden like small animals getting from under a burning-glass.

The children were to pay an afternoon visit on the following day to Aunt Pullet at Garum Firs, where they would hear Uncle Pullet's musical-box.

Already, at twelve o'clock, Mrs. Tulliver had on her visiting costume. Maggie was frowning, and twisting her shoulders, that she might, if possible, shrink away from the prickliest of tuckers; while her mother was saying, "Don't, Maggie, my dear—don't look so ugly!" Tom's cheeks were looking very red against his best blue suit, in the pockets of which he had, to his great joy, stowed away all the contents of his everyday pockets.

As for Lucy, she was just as pretty and neat as she had been yesterday, and she looked with wondering pity at Maggie pouting and writhing under the tucker. While waiting for the time to set out, they were allowed to build card-houses, as a suitable amusement for boys and girls in their best clothes.

Tom could build splendid houses, but Maggie's would never bear the laying on of the roof. It was always so with the things that Maggie made, and Tom said that no girls could ever make anything.

But it happened that Lucy was very clever at building; she handled the cards so lightly, and moved so gently, that Tom admired her houses as well as his own—the more readily because she had asked him to teach her. Maggie, too, would have admired Lucy's houses if Tom had not laughed when her houses fell, and told her that she was "a stupid."

"Don't laugh at me, Tom!" she burst out angrily. "I'm not a stupid. I know a great many things you don't."

"Oh, I dare say, Miss Spitfire! I'd never be such a cross thing as you—making faces like that. Lucy doesn't do so. I like Lucy better than you. I wish Lucy was my sister."

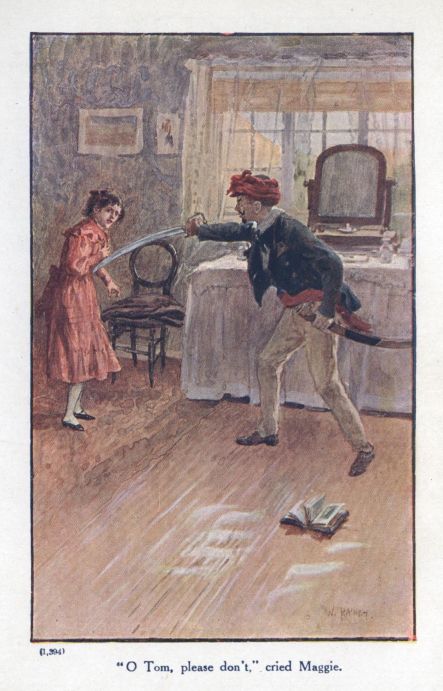

"Then it's wicked and cruel of you to wish so," said Maggie, starting up from her place on the floor and upsetting Tom's wonderful pagoda. She really did not mean it, but appearances were against her, and Tom turned white with anger, but said nothing. He would have struck her, only he knew it was cowardly to strike a girl.

Maggie stood in dismay and terror while Tom got up from the floor and walked away. Lucy looked on mutely, like a kitten pausing from its lapping.

"O Tom," said Maggie at last, going half-way towards him, "I didn't mean to knock it down—indeed, indeed, I didn't."

Tom took no notice of her, but took, instead, two or three hard peas out of his pocket, and shot them with his thumbnail against the window, with the object of hitting a bluebottle which was sporting in the spring sunshine.

Thus the morning had been very sad to Maggie, and when at last they set out Tom's coldness to her all through their walk spoiled the fresh air and sunshine for her. He called Lucy to look at the half-built bird's nest without caring to show it to Maggie, and peeled a willow switch for Lucy and himself without offering one to Maggie. Lucy had said, "Maggie, shouldn't you like one?" but Tom was deaf.

Still, the sight of the peacock spreading his tail on the stackyard wall, just as they reached the aunt's house, was enough to turn the mind from sadness. And this was only the beginning of beautiful sights at Garum Firs.

All the farmyard life was wonderful there—bantams, speckled and top-knotted; Friesland hens, with their feathers all turned the wrong way; Guinea-fowls that flew and screamed, and dropped their pretty-spotted feathers; pouter pigeons, and a tame magpie; nay, a goat, and a wonderful dog, half mastiff, half bull-dog, as large as a lion!

Uncle Pullet had seen the party from the window, and made haste to unbar and unchain the front door. Aunt Pullet, too, appeared at the doorway, and as soon as her sister was within hearing said, "Stop the children, Bessy; don't let 'em come up the doorsteps. Sally's bringing the old mat and the duster to rub their shoes."

"You must come with me into the best room," she went on as soon as her guests had passed the portal.

"May the children come too, sister?" inquired Mrs. Tulliver, who saw that Maggie and Lucy were looking rather eager.

"Well," said Aunt Pullet, "it'll perhaps be safer for the girls to come; they'll be touching something if we leave 'em behind."

When they all came down again Uncle Pullet said that he reckoned the missis had been showing her bonnet—that was what had made them so long upstairs.

Meanwhile Tom had spent the time on the edge of the sofa directly opposite his Uncle Pullet, who looked at him with twinkling gray eyes and spoke to him as "young sir."

"Well, young sir, what do you learn at school?" was the usual question with Uncle Pullet; whereupon Tom always looked sheepish, rubbed his hand across his face, and answered, "I don't know."

The appearance of the little girls made Uncle Pullet think of some small sweetcakes, of which he kept a stock under lock and key for his own private eating on wet days; but the three children had no sooner got them between their fingers than Aunt Pullet desired them to abstain from eating till the tray and the plates came, since with those crisp cakes they would make the floor "all over" crumbs.

Lucy didn't mind that much, for the cake was so pretty she thought it was rather a pity to eat it; but Tom, watching his chance while the elders were talking, hastily stowed his own cake in his mouth at two bites. As for Maggie, she presently let fall her cake, and by an unlucky movement crushed it beneath her foot—a source of such disgrace to her that she began to despair of hearing the musical snuff-box to-day, till it occurred to her that Lucy was in high favour enough to venture on asking for a tune.

So she whispered to Lucy, and Lucy, who always did what she was asked to do, went up quietly to her uncle's knee, and, blushing all over her neck while she fingered her necklace, said, "Will you please play us a tune, uncle?" But Uncle Pullet never gave a too ready consent. "We'll see about it," was the answer he always gave, waiting till a suitable number of minutes had passed.

Perhaps the waiting increased Maggie's enjoyment when the tune began. For the first time she quite forgot that she had a load on her mind—that Tom was angry with her; and by the time "Hush, ye pretty warbling choir" had been played, her face wore that bright look of happiness, while she sat still with her hands clasped, which sometimes comforted her mother that Maggie could look pretty now and then, in spite of her brown skin. But when the magic music ceased, she jumped up, and running towards Tom, put her arm round his neck and said, "O Tom, isn't it pretty?"

Now Tom had his glass of cowslip wine in his hand, and Maggie jerked him so as to make him spill half of it. He would have been an extreme milksop if he had not said angrily, "Look there, now!"

"Why don't you sit still, Maggie?" her mother said peevishly.

"Little gells mustn't come to see me if they behave in that way," said Aunt Pullet.

"Why, you're too rough, little miss," said Uncle Pullet.

Poor Maggie sat down again, with the music all chased out of her soul.

Mrs. Tulliver wisely took an early opportunity of suggesting that, now they were rested after their walk, the children might go and play out of doors; and Aunt Pullet gave them leave, only telling them not to go off the paved walks in the garden, and if they wanted to see the poultry fed, to view them from a distance on the horse-block.

For a long time after the children had gone out the elders sat deep in talk about family matters, till at last Mrs. Pullet, observing that it was tea-time, turned to reach from a drawer a fine damask napkin, which she pinned before her in the fashion of an apron. Then the door was thrown open; but instead of the tea-tray, Sally brought in an object so startling that both Mrs. Pullet and Mrs. Tulliver gave a scream, causing Uncle Pullet to swallow a lozenge he was sucking—for the fifth time in his life, as he afterwards noted.

The startling object was no other than little Lucy, with one side of her person, from her small foot to her bonnet-crown, wet and discoloured with mud, holding out two tiny blackened hands, and making a very piteous face.

As soon as the children reached the open air Tom said, "Here, Lucy, you come along with me," and walked off to the place where the toads were, as if there were no Maggie in existence. Lucy was naturally pleased that Cousin Tom was so good to her, and it was very amusing to see him tickling a fat toad with a piece of string, when the toad was safe down the area, with an iron grating over him.

Still Lucy wished Maggie to enjoy the sight also, especially as she would doubtless find a name for the toad, and say what had been his past history; for Lucy loved Maggie's stories about the live things they came upon by accident—how Mrs. Earwig had a wash at home, and one of her children had fallen into the hot copper, for which reason she was running so fast to fetch the doctor. So now the desire to know the history of a very portly toad made her run back to Maggie and say, "Oh, there is such a big, funny toad, Maggie! Do come and see."

Maggie said nothing, but turned away from her with a deep frown. She was actually beginning to think that she should like to make Lucy cry, by slapping or pinching her, especially as it might vex Tom, whom it was of no use to slap, even if she dared, because he didn't mind it. And if Lucy hadn't been there, Maggie was sure he would have made friends with her sooner.

Tickling a fat toad is an amusement that does not last, and Tom by-and-by began to look round for some other mode of passing the time. But in so prim a garden, where they were not to go off the paved walks, there was not a great choice of sport.

"I say, Lucy," he began, nodding his head up and down, as he coiled up his string again, "what do you think I mean to do?"

"What, Tom?" said Lucy.

"I mean to go to the pond and look at the pike. You may go with me if you like."

"O Tom, dare you?" said Lucy. "Aunt said we mustn't go out of the garden."

"Oh, I shall go out at the other end of the garden," said Tom. "Nobody 'ull see us. Besides, I don't care if they do; I'll run off home."

"But I couldn't run," said Lucy.

"Oh, never mind; they won't be cross with you," said Tom. "You say I took you."

Tom walked along, and Lucy trotted by his side. Maggie saw them leaving the garden, and could not resist the impulse to follow. She kept a few yards behind them unseen by Tom, who was watching for the pike—a highly interesting monster; he was said to be so very old, so very large, and to have such a great appetite.

"Here, Lucy," he said in a loud whisper, "come here."

Lucy came carefully as she was bidden, and bent down to look at what seemed a golden arrow-head darting through the water. It was a water-snake, Tom told her; and Lucy at last could see the wave of its body, wondering very much that a snake could swim.

Maggie had drawn nearer and nearer; she must see it too, though it was bitter to her, like everything else, since Tom did not care about her seeing it. At last she was close by Lucy, and Tom turned round and said,—

"Now, get away, Maggie. There's no room for you on the grass here. Nobody asked you to come."

Then Maggie, with a fierce thrust of her small brown arm, pushed poor little pink-and-white Lucy into the cow-trodden mud.

Tom could not restrain himself, and gave Maggie two smart slaps on the arm as he ran to pick up Lucy, who lay crying helplessly. Maggie retreated to the roots of a tree a few yards off, and looked on. Why should she be sorry? Tom was very slow to forgive her, however sorry she might have been.

"I shall tell mother, you know, Miss Mag," said Tom, as soon as Lucy was up and ready to walk away. It was not Tom's practice to "tell," but here justice clearly demanded that Maggie should be visited with the utmost punishment.

"Sally," said Tom, when they reached the kitchen door—"Sally, tell mother it was Maggie pushed Lucy into the mud."

Sally, as we have seen, lost no time in presenting Lucy at the parlour door.

"Goodness gracious!" Aunt Pullet exclaimed, after giving a scream; "keep her at the door, Sally! Don't bring her off the oilcloth, whatever you do."

"Why, she's tumbled into some nasty mud," said Mrs. Tulliver, going up to Lucy.

"If you please, 'um, it was Miss Maggie as pushed her in," said Sally. "Master Tom's been and said so; and they must ha' been to the pond, for it's only there they could ha' got into such dirt."

"There it is, Bessy; it's what I've been telling you," said Mrs. Pullet. "It's your children; there's no knowing what they'll come to."

Mrs. Tulliver went out to speak to these naughty children, supposing them to be close at hand; but it was not until after some search that she found Tom leaning with rather a careless air against the white paling of the poultry-yard, and lowering his piece of string on the other side as a means of teasing the turkey-cock.

"Tom, you naughty boy, where's your sister?" said Mrs. Tulliver in a distressed voice.

"I don't know," said Tom.

"Why, where did you leave her?" said his mother, looking round.

"Sitting under the tree against the pond," said Tom.

"Then go and fetch her in this minute, you naughty boy. And how could you think o' going to the pond, and taking your sister where there was dirt? You know she'll do mischief, if there's mischief to be done."

The idea of Maggie sitting alone by the pond roused a fear in Mrs. Tulliver's mind, and she mounted the horse-block to satisfy herself by a sight of that fatal child, while Tom walked—not very quickly—on his way towards her.

"They're such children for the water, mine are," she said aloud, without reflecting that there was no one to hear her; "they'll be brought in dead and drownded some day. I wish that river was far enough."

But when she not only failed to see Maggie, but presently saw Tom returning from the pond alone, she hurried to meet him.

"Maggie's nowhere about the pond, mother," said Tom; "she's gone away."

After Tom and Lucy had walked away, Maggie's quick mind formed a plan which was not so simple as that of going home. No; she would run away and go to the gipsies, and Tom should never see her any more. She had been often told she was like a gipsy, and "half wild;" so now she would go and live in a little brown tent on the common.

The gipsies, she considered, would gladly receive her, and pay her much respect on account of her superior knowledge. She had once mentioned her views on this point to Tom, and suggested that he should stain his face brown, and they should run away together; but Tom rejected the scheme with contempt, observing that gipsies were thieves, and hardly got anything to eat, and had nothing to drive but a donkey. To-day, however, Maggie thought her misery had reached a pitch at which gipsydom was her only refuge, and she rose from her seat on the roots of the tree with the sense that this was a great crisis in her life.

She would run straight away till she came to Dunlow Common, where there would certainly be gipsies; and cruel Tom, and the rest of her relations who found fault with her, should never see her any more. She thought of her father as she ran along, but made up her mind that she would secretly send him a letter by a small gipsy, who would run away without telling where she was, and just let him know that she was well and happy, and always loved him very much.

Maggie soon got out of breath with running, but by the time that Tom got to the pond again she was at the distance of three long fields, and was on the edge of the lane leading to the highroad.

She presently passed through the gate into the lane, and she was soon aware, not without trembling, that there were two men coming along the lane in front of her.

She had not thought of meeting strangers; and, to her surprise, while she was dreading their scolding as a runaway, one of the men stopped, and in a half-whining, half-coaxing tone asked her if she had a copper to give a poor fellow.

Maggie had a sixpence in her pocket—her Uncle Glegg's present—which she drew out and gave this "poor fellow" with a polite smile. "That's the only money I've got," she said. "Thank you, little miss," said the man in a less grateful tone than Maggie expected, and she even saw that he smiled and winked at his companion.

She now went on, and turning through the first gate that was not locked, crept along by the hedgerows. She was used to wandering about the fields by herself, and was less timid there than on the highroad. Sometimes she had to climb over high gates, but that was a small evil; she was getting out of reach very fast, and she should probably soon come within sight of Dunlow Common. She hoped so, for she was getting rather tired and hungry. It was still broad daylight, yet it seemed to her that she had been walking a very great distance indeed, and it was really surprising that the common did not come in sight.

At last, however, the green fields came to an end, and Maggie found herself looking through the bars of a gate into a lane with a wide margin of grass on each side of it. She crept through the bars of the gate and walked on with a new spirit, and at the next bend in the lane Maggie actually saw the little black tent with the blue smoke rising before it which was to be her refuge. She even saw a tall female figure by the column of smoke—doubtless the gipsy-mother, who provided the tea and other groceries; it was astonishing to herself that she did not feel more delighted. But it was startling to find the gipsies in a lane after all, and not on a common—indeed, it was rather disappointing; for a mysterious common, where there were sand-pits to hide in, and one was out of everybody's reach, had always made part of Maggie's picture of gipsy life.

She went on, however, and before long a tall figure, who proved to be a young woman with a baby on her arm, walked slowly to meet her. Maggie looked up in the new face and thought that her Aunt Pullet and the rest were right when they called her a gipsy; for this face, with the bright dark eyes and the long hair, was really something like what she used to see in her own glass before she cut her hair off.

"My little lady, where are you going to?" the gipsy said.

It was delightful, and just what Maggie expected—the gipsy saw at once that she was a little lady.

"Not any farther," said Maggie. "I'm come to stay with you, please."

"That's pritty; come, then. Why, what a nice little lady you are, to be sure!" said the gipsy, taking her by the hand. Maggie thought her very nice, but wished she had not been so dirty.

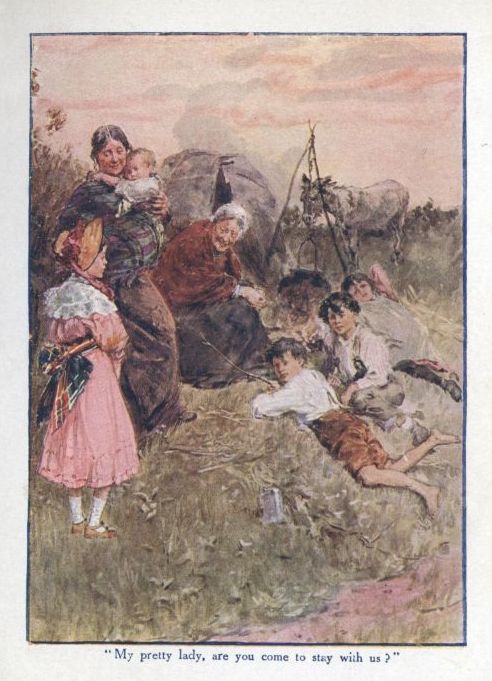

There was quite a group round the fire when they reached it. An old gipsy-woman was seated on the ground nursing her knees, and poking a skewer into the round kettle that sent forth an odorous steam; two small, shock-headed children were lying down resting on their elbows; and a donkey was bending his head over a tall girl, who, lying on her back, was scratching his nose and feeding him with a bite of excellent stolen hay.

The slanting sunlight fell kindly upon them, and the scene was really very pretty and comfortable, Maggie thought, only she hoped they would soon set out the tea-cups. It was a little confusing, though, that the young woman began to speak to the old one in a language which Maggie did not understand, while the tall girl who was feeding the donkey sat up and stared at her. At last the old woman said,—

"What, my pretty lady, are you come to stay with us? Sit ye down, and tell us where you come from."

It was just like a story. Maggie liked to be called pretty lady and treated in this way. She sat down and said,—

"I'm come from home because I'm unhappy, and I mean to be a gipsy. I'll live with you, if you like, and I can teach you a great many things."

"Such a clever little lady," said the woman with the baby, sitting down by Maggie, and allowing baby to crawl; "and such a pritty bonnet and frock," she added, taking off Maggie's bonnet and looking at it while she spoke to the old woman in the unknown language. The tall girl snatched the bonnet and put it on her own head hind-foremost with a grin; but Maggie was determined not to show that she cared about her bonnet.

"I don't want to wear a bonnet," she said; "I'd rather wear a red handkerchief, like yours" (looking at her friend by her side). "My hair was quite long till yesterday, when I cut it off; but I dare say it will grow again very soon."

"Oh, what a nice little lady!—and rich, I'm sure," said the old woman. "Didn't you live in a beautiful house at home?"

"Yes, my home is pretty, and I'm very fond of the river, where we go fishing; but I'm often very unhappy. I should have liked to bring my books with me, but I came away in a hurry, you know. But I can tell you almost everything there is in my books, I've read them so many times, and that will amuse you. And I can tell you something about geography too—that's about the world we live in—very useful and interesting. Did you ever hear about Columbus?"

"Is that where you live, my little lady?" said the old woman at the mention of Columbus.

"Oh no!" said Maggie, with some pity. "Columbus was a very wonderful man, who found out half the world; and they put chains on him and treated him very badly, you know—but perhaps it's rather too long to tell before tea. I want my tea so."

"Why, she's hungry, poor little lady," said the younger woman. "Give her some o' the cold victual.—You've been walking a good way, I'll be bound, my dear. Where's your home?"

"It's Dorlcote Mill—a good way off," said Maggie. "My father is Mr. Tulliver; but we mustn't let him know where I am, else he'll fetch me home again. Where does the queen of the gipsies live?"

"What! do you want to go to her, my little lady?" said the younger woman.

"No," said Maggie; "I'm only thinking that if she isn't a very good queen you might be glad when she died, and you could choose another. If I was a queen, I'd be a very good queen, and kind to everybody."

"Here's a bit o' nice victual, then," said the old woman, handing to Maggie a lump of dry bread, which she had taken from a bag of scraps, and a piece of cold bacon.

"Thank you," said Maggie, looking at the food without taking it; "but will you give me some bread and butter and tea instead? I don't like bacon."

"We've got no tea nor butter," said the old woman with something like a scowl.

"Oh, a little bread and treacle would do," said Maggie.

"We han't got no treacle," said the old woman crossly.

Meanwhile the tall girl gave a shrill cry, and presently there came running up a rough urchin about the age of Tom. He stared at Maggie, and she felt very lonely, and was quite sure she should begin to cry before long. But the springing tears were checked when two rough men came up, while a black cur ran barking up to Maggie, and threw her into a tremor of fear.

Maggie felt that it was impossible she should ever be queen of these people.

"This nice little lady's come to live with us," said the young woman. "Aren't you glad?"

"Ay, very glad," said the younger man, who was soon examining Maggie's silver thimble and other small matters that had been taken from her pocket. He returned them all except the thimble to the younger woman, and she immediately restored them to Maggie's pocket, while the men seated themselves, and began to attack the contents of the kettle—a stew of meat and potatoes—which had been taken off the fire and turned out into a yellow platter.

Maggie began to think that Tom must be right about the gipsies: they must certainly be thieves, unless the man meant to return her thimble by-and-by. All thieves, except Robin Hood, were wicked people.

The women now saw she was frightened.

"We've got nothing nice for a lady to eat," said the old woman, in her coaxing tone. "And she's so hungry, sweet little lady!"

"Here, my dear, try if you can eat a bit o' this," said the younger woman, handing some of the stew on a brown dish with an iron spoon to Maggie, who dared not refuse it, though fear had chased away her appetite. If her father would but come by in the gig and take her up! Or even if Jack the Giantkiller, or Mr. Greatheart, or St. George who slew the dragon on the half-pennies, would happen to pass that way!

"What! you don't like the smell of it, my dear," said the young woman, observing that Maggie did not even take a spoonful of the stew. "Try a bit—come."

"No, thank you," said Maggie, trying to smile in a friendly way. "I haven't time, I think—it seems getting darker. I think I must go home now, and come again another day, and then I can bring you a basket with some jam-tarts and things."

Maggie rose from her seat, when the old gipsy-woman said, "Stop a bit, stop a bit, little lady; we'll take you home all safe when we've done supper. You shall ride home like a lady."

Maggie sat down again, with little faith in this promise, though she presently saw the tall girl putting a bridle on the donkey and throwing a couple of bags on his back.

"Now, then, little missis," said the younger man, rising and leading the donkey forward, "tell us where you live. What's the name o' the place?"

"Dorlcote Mill is my home," said Maggie eagerly. "My father is Mr. Tulliver; he lives there."

"What! a big mill a little way this side o' St. Ogg's?"

"Yes," said Maggie. "Is it far off? I think I should like to walk there, if you please."

"No, no, it'll be getting dark; we must make haste. And the donkey'll carry you as nice as can be—you'll see."

He lifted Maggie as he spoke, and set her on the donkey.

"Here's your pretty bonnet," said the younger woman, putting it on Maggie's head. "And you'll say we've been very good to you, won't you, and what a nice little lady we said you was?"

"Oh yes, thank you," said Maggie; "I'm very much obliged to you. But I wish you'd go with me too."

"Ah, you're fondest o' me, aren't you?" said the woman. "But I can't go; you'll go too fast for me."

It now appeared that the man also was to be seated on the donkey, holding Maggie before him, and no nightmare had ever seemed to her more horrible. When the woman had patted her on the back, and said "good-bye," the donkey, at a strong hint from the man's stick, set off at a rapid walk along the lane towards the point Maggie had come from an hour ago.

Maggie was completely terrified at this ride on a short-paced donkey, with a gipsy behind her, who considered that he was earning half a crown. Two low thatched cottages—the only houses they passed in this lane—seemed to add to the dreariness. They had no windows to speak of, and the doors were closed. It was probable that they were inhabited by witches, and it was a relief to find that the donkey did not stop there.

At last—oh, sight of joy!—this lane, the longest in the world, was coming to an end, and was opening on a broad highroad, where there was actually a coach passing! And there was a finger-post at the corner. She had surely seen that finger-post before—"To St. Ogg's, 2 miles."

The gipsy really meant to take her home, then. He was probably a good man after all, and might have been rather hurt at the thought that she didn't like coming with him alone. This idea became stronger as she felt more and more certain that she knew the road quite well, when, as they reached a cross-road, Maggie caught sight of some one coming on a horse which seemed familiar to her.

"Oh, stop, stop!" she cried out. "There's my father!—O father, father!"

The sudden joy was almost painful, and before her father reached her she was sobbing. Great was Mr. Tulliver's wonder, for he had been paying a visit to a married sister, and had not yet been home.

"Why, what's the meaning o' this?" he said, checking his horse, while Maggie slipped from the donkey and ran to her father's stirrup.

"The little miss lost herself, I reckon," said the gipsy. "She'd come to our tent at the far end o' Dunlow Lane, and I was bringing her where she said her home was. It's a good way to come arter being on the tramp all day."

"Oh yes, father, he's been very good to bring me home," said Maggie—"a very kind, good man!"

"Here, then, my man," said Mr. Tulliver, taking out five shillings. "It's the best day's work you ever did. I couldn't afford to lose the little wench. Here, lift her up before me."

"Why, Maggie, how's this, how's this?" he said, as they rode along, while she laid her head against her father and sobbed. "How came you to be rambling about and lose yourself?"

"O father," sobbed Maggie, "I ran away because I was so unhappy—Tom was so angry with me. I couldn't bear it."

"Pooh, pooh!" said Mr. Tulliver soothingly; "you mustn't think o' running away from father. What 'ud father do without his little wench?"

"Oh no, I never will again, father—never."

Mr. Tulliver spoke his mind very strongly when he reached home that evening, and Maggie never heard one reproach from her mother, or one taunt from Tom, about running away to be queen of the gipsies.

In due time Tom found himself at King's Lorton, under the care of the Rev. Walter Stelling, a big, broad-chested man, not yet thirty, with fair hair standing erect, large light-gray eyes, and a deep bass voice.

The schoolmaster had made up his mind to bring Tom on very quickly during the first half-year; but Tom did not greatly enjoy the process, though he made good progress in a very short time.

The boy was, however, very lonely, and longed for playfellows. In his secret heart he yearned to have Maggie with him; though, when he was at home, he always made it out to be a great favour on his part to let Maggie trot by his side on his pleasure excursions.

And before this dreary half-year was ended Maggie actually came. Mrs. Stelling had given a general invitation for the little girl to come and stay with her brother; so when Mr. Tulliver drove over to King's Lorton late in October, Maggie came too. It was Mr. Tulliver's first visit to see Tom, for the lad must learn, he had said, not to think too much about home.

"Well, my lad," the miller said to Tom, when Mr. Stelling had left the room, and Maggie had begun to kiss Tom freely, "you look rarely. School agrees with you."

Tom wished he had looked rather ill.

"I don't think I am well, father," said Tom; "I wish you'd ask Mr. Stelling not to let me do Euclid; it brings on the tooth-ache, I think."

"Euclid, my lad. Why, what's that?" said Mr. Tulliver.

"Oh, I don't know. It's definitions, and axioms, and triangles, and things. It's a book I've got to learn in; there's no sense in it."

"Go, go!" said Mr. Tulliver; "you mustn't say so. You must learn what your master tells you. He knows what it's right for you to learn."

"I'll help you now, Tom," said Maggie. "I'm come to stay ever so long, if Mrs. Stelling asks me. I've brought my box and my pinafores—haven't I, father?"

"You help me, you silly little thing!" said Tom. "I should like to see you doing one of my lessons! Why, I learn Latin too! Girls never learn such things; they're too silly."

"I know what Latin is very well," said Maggie confidently. "Latin's a language. There are Latin words in the dictionary. There's bonus, a gift."

"Now you're just wrong there, Miss Maggie!" said Tom. "You think you're very wise. But bonus means 'good,' as it happens—bonus, bona, bonum."

"Well, that's no reason why it shouldn't mean 'gift,'" said Maggie stoutly. "It may mean several things—almost every word does. There's 'lawn'—it means the grass-plot, as well as the stuff handkerchiefs are made of."

"Well done, little un," said Mr. Tulliver, laughing, while Tom felt rather disgusted.

Mrs. Stelling did not mention a longer time than a week for Maggie's stay, but Mr. Stelling said that she must stay a fortnight.

"Now, then, come with me into the study, Maggie," said Tom, as their father drove away. "What do you shake and toss your head now for, you silly? It makes you look as if you were crazy."

"Oh, I can't help it," said Maggie. "Don't tease me, Tom. Oh, what books!" she exclaimed, as she saw the bookcases in the study. "How I should like to have as many books as that!"

"Why, you couldn't read one of 'em," said Tom triumphantly. "They're all Latin."

"No, they aren't," said Maggie. "I can read the back of this—History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire."

"Well, what does that mean? You don't know," said Tom, wagging his head.

"But I could soon find out," said Maggie.

"Why, how?"

"I should look inside, and see what it was about."

"You'd better not, Miss Maggie," said Tom, seeing her hand on the volume. "Mr. Stelling lets nobody touch his books without leave, and I shall catch it if you take it out."

"Oh, very well! Let me see all your books, then," said Maggie, turning to throw her arms round Tom's neck, and rub his cheek with her small round nose.

Tom, in the gladness of his heart at having dear old Maggie to dispute with and crow over again, seized her round the waist, and began to jump with her round the large library table. Away they jumped with more and more vigour, till at last, reaching Mr. Stelling's reading-stand, they sent it thundering down with its heavy books to the floor. Tom stood dizzy and aghast for a few minutes, dreading the appearance of Mr. or Mrs. Stelling.

"Oh, I say, Maggie," said Tom at last, lifting up the stand, "we must keep quiet here, you know. If we break anything, Mrs. Stelling'll make us cry peccavi."

"What's that?" said Maggie.

"Oh, it's the Latin for a good scolding," said Tom.

"Is she a cross woman?" said Maggie.

"I believe you!" said Tom, with a nod.

"I think all women are crosser than men," said Maggie. "Aunt Glegg's a great deal crosser than Uncle Glegg, and mother scolds me more than father does."

"Well, you'll be a woman some day," said Tom, "so you needn't talk."

"But I shall be a clever woman," said Maggie, with a toss.

"Oh, I dare say, and a nasty, conceited thing. Everybody'll hate you."

"But you oughtn't to hate me, Tom. It'll be very wicked of you, for I shall be your sister."

"Yes; but if you're a nasty, disagreeable thing, I shall hate you."

"Oh but, Tom, you won't! I shan't be disagreeable. I shall be very good to you, and I shall be good to everybody. You won't hate me really, will you, Tom?"

"Oh, bother, never mind! Come, it's time for me to learn my lessons. See here what I've got to do," Tom went on, drawing Maggie towards him, and showing her his theorem, while she pushed her hair behind her ears, and prepared herself to help him in Euclid.

"It's nonsense!" she said, after a few moments reading, "and very ugly stuff; nobody need want to make it out."

"Ah, there now, Miss Maggie!" said Tom, drawing the book away and wagging his head at her; "you see you're not so clever as you thought you were."

"Oh," said Maggie, pouting, "I dare say I could make it out if I'd learned what goes before, as you have."

"But that's what you just couldn't, Miss Wisdom," said Tom. "For it's all the harder when you know what goes before. But get along with you now; I must go on with this. Here's the Latin Grammar. See what you can make of that."

Maggie found the Latin Grammar quite soothing, for she delighted in new words, and quickly found that there was an English Key at the end, which would make her very wise about Latin at slight expense.

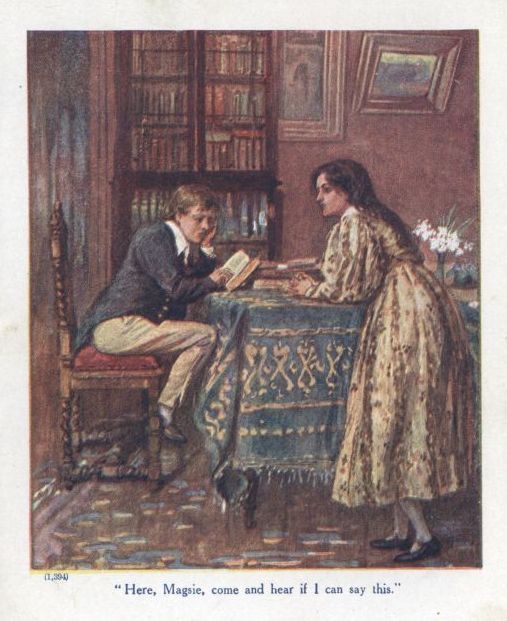

After a short period of silence Tom called out,—

"Now, then, Magsie, give us the Grammar!"

"O Tom, it's such a pretty book!" she said, as she jumped out of the large armchair to give it him. "I could learn Latin very soon. I don't think it's at all hard."

"Oh, I know what you've been doing," said Tom; "you've been reading the English at the end. Any donkey can do that. Here, come and hear if I can say this. Stand at that end of the table."

Maggie obeyed, and took the open book.

"Where do you begin, Tom?"

"Oh, I begin at 'Appellativa arborum,' because I say all over again what I've been learning this week."

Tom sailed along pretty well for three lines, and then he stuck fast.

"There, you needn't laugh at me, Tom, for you didn't remember it at all, you see."

"Phee-e-e-h! I told you girls couldn't learn Latin."

"Very well, then," said Maggie, pouting. "I can say it as well as you can. And you don't mind your stops. For you ought to stop twice as long at a semicolon as you do at a comma, and you make the longest stops where there ought to be no stops at all."

"Oh, well, don't chatter. Let me go on."

It was a very happy fortnight to Maggie, this visit to Tom. She was allowed to be in the study while he had his lessons, and in time got very deep into the examples in the Latin Grammar.

Mr. Stelling liked her prattle immensely, and they were on the best of terms. She told Tom she should like to go to school to Mr. Stelling, as he did, and learn just the same things. She knew she could do Euclid, for she had looked into it again, and she saw what ABC meant—they were the names of the lines.

"I'm sure you couldn't do it, now," said Tom, "and I'll just ask Mr. Stelling if you could."

"I don't mind," said she. "I'll ask him myself."

"Mr. Stelling," she said, that same evening when they were in the drawing-room, "couldn't I do Euclid, and all Tom's lessons, if you were to teach me instead of him?"

"No, you couldn't," said Tom indignantly. "Girls can't do Euclid—can they, sir?"

"They can pick up a little of everything, I dare say," said Mr. Stelling; "but they couldn't go far into anything. They're quick and shallow."

Tom, delighted with this, wagged his head at Maggie behind Mr. Stelling's chair. As for Maggie, she had hardly ever been so angry. She had been so proud to be called "quick" all her little life, and now it appeared that this quickness showed what a poor creature she was. It would have been better to be slow, like Tom.

"Ha, ha, Miss Maggie!" said Tom, when they were alone; "you see it's not such a fine thing to be quick. You'll never go far into anything, you know."

And Maggie had no spirit for a retort.