Title: The Day of Sir John Macdonald

Author: Sir Joseph Pope

Release date: November 1, 2009 [eBook #30384]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

Within a short time will be celebrated the centenary of the birth of the great statesman who, half a century ago, laid the foundations and, for almost twenty years, guided the destinies of the Dominion of Canada.

Nearly a like period has elapsed since the author's Memoirs of Sir John Macdonald was published. That work, appearing as it did little more than three years after his death, was necessarily subject to many limitations and restrictions. As a connected story it did not profess to come down later than the year 1873, nor has the time yet arrived for its continuation and completion on the same lines. That task is probably reserved for other and freer hands than mine. At the same time, it seems desirable that, as Sir John Macdonald's centenary approaches, there should be available, in convenient form, a short résumé of the salient features of his {viii} career, which, without going deeply and at length into all the public questions of his time, should present a familiar account of the man and his work as a whole, as well as, in a lesser degree, of those with whom he was intimately associated. It is with such object that this little book has been written.

JOSEPH POPE.

OTTAWA, 1914.

| Page | ||

| PREFATORY NOTE | vii | |

| I. | YOUTH | 1 |

| II. | MIDDLE LIFE | 40 |

| III. | OLD AGE | 139 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE | 184 | |

| INDEX | 187 |

|

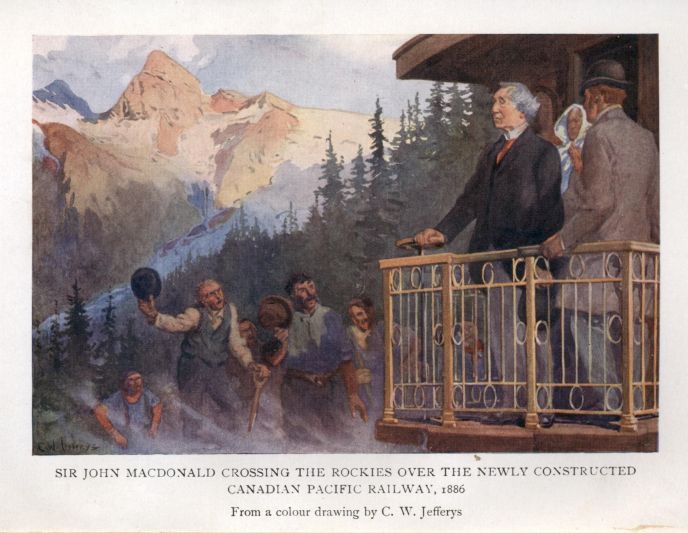

SIR JOHN MACDONALD CROSSING THE

ROCKIES OVER THE NEWLY CONSTRUCTED

CANADIAN PACIFIC RAILWAY, 1886 From a colour drawing by C. W. Jefferys. |

Frontispiece |

|

THE MACDONALD HOMESTEAD AT ADOLPHUSTOWN From a print in the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library. |

Facing page 4 |

|

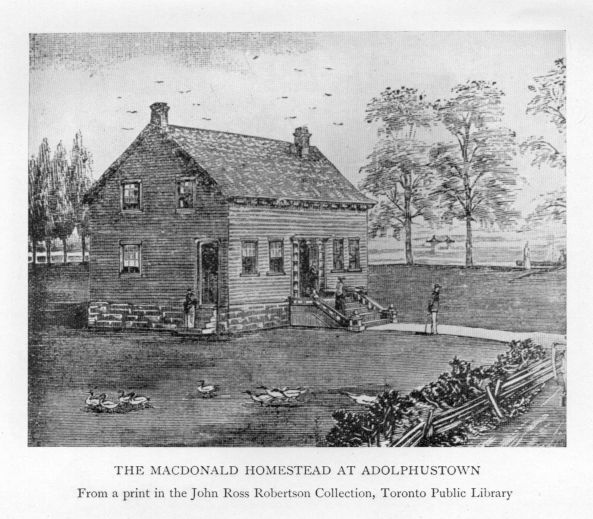

JOHN A. MACDONALD IN 1842 From a photograph. |

" 12 |

|

SIR ALLAN NAPIER MACNAB From a portrait in the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library. |

" 36 |

|

SIR EDMUND WALKER HEAD From the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library. |

" 42 |

|

SIR ÉTIENNE PASCAL TACHÉ From a portrait in the John Ross Robertson Collection, Toronto Public Library. |

" 70 |

|

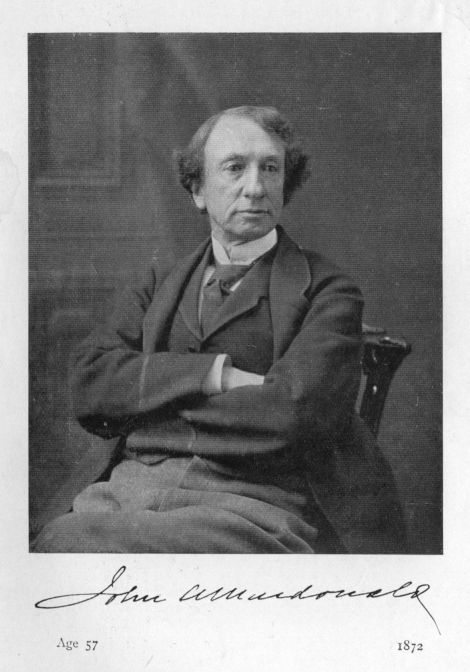

SIR JOHN A. MACDONALD IN 1872 From a photograph. |

" 96 |

|

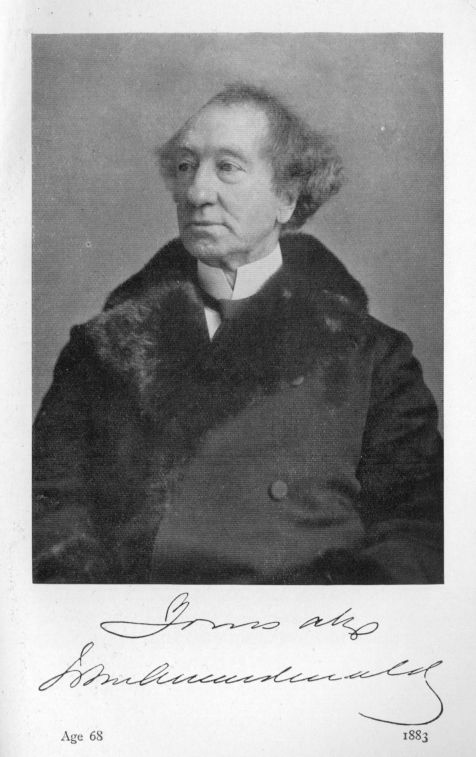

SIR JOHN A. MACDONALD IN 1883 From a photograph. |

" 138 |

John Alexander Macdonald, second son of Hugh Macdonald and Helen Shaw, was born in Glasgow on January 11, 1815. His father, originally from Sutherlandshire, removed in early life to Glasgow, where he formed a partnership with one M'Phail, and embarked in business as a cotton manufacturer. Subsequently he engaged in the manufacture of bandanas, and the style of the firm became 'H. Macdonald and Co.' The venture did not prove successful, and Macdonald resolved to try his fortunes in the New World. Accordingly, in the year 1820, he embarked for Canada in the good ship Earl of Buckinghamshire, and after a voyage long and irksome even for those days, landed at Quebec and journeyed overland to Kingston, then and for some years after the most considerable town in Upper Canada, boasting a population (exclusive of the military) of about 2500 souls.

At that time the whole population of what is now the province of Ontario did not exceed 120,000, clustered, for the most part, in settlements along the Bay of Quinté, Lake Ontario proper, and the vicinity of the Niagara and Detroit rivers. The interior of the province was covered with the primeval forest, which disappeared slowly, and only by dint of painful and unceasing toil. The early accounts of Kingston bear eloquent testimony to its primitive character. In 1815, according to a correspondent of the Kingston Gazette, the town possessed no footways worthy of the name, in consequence of which lack it was, during rainy weather, 'scarcely possible to move about without being in mud to the ankles.' No provision existed for lighting the streets 'in the dark of the moon'; a fire-engine was badly needed, and also the enforcement of a regulation prohibiting the piling of wood in public thoroughfares.

Communication with the outside world, in those early days, was slow, toilsome, and sometimes dangerous. The roads were, for the most part, Indian paths, somewhat improved in places, but utterly unsuited, particularly in spring and autumn, for the passage of heavily laden vehicles. In 1817 a weekly {3} stage began running from Kingston to York (Toronto), with a fare of eighteen dollars. The opening of an overland highway between Kingston and Montreal, which could be travelled on by horses, was hailed as a great boon. Prior to this the journey to Montreal had been generally made by water, in an enlarged and improved type of bateau known as a Durham boat, which had a speed of two to three miles an hour. The cost to the passenger was one cent and a half a mile, including board.

In the early twenties of the nineteenth century the infant province of Upper Canada found itself slowly recovering from the effects of the War of 1812-14. Major-General Sir Peregrine Maitland, the lieutenant-governor, together with the Executive and Legislative Councils, was largely under the influence of the 'Family Compact' of those days. The oligarchical and selfish rule of this coterie gave rise to much dissatisfaction among the people, whose discontent, assiduously fanned by agitators like Robert Gourlay, culminated in open rebellion in the succeeding decade.

Such was the condition of things prevailing at the time when the future prime minister arrived in the town with which he was destined {4} to be in close association for nearly three-quarters of a century.

Hugh Macdonald, after a few years of unsatisfactory experience in Kingston, determined upon seeking fortune farther west. Accordingly he moved up the Bay of Quinté to the township of Adolphustown, which had been settled about forty years previously by a party of United Empire Loyalists under the command of one Captain Van Alstine. Here, at Hay Bay, Macdonald opened a shop. Subsequently he moved across the Bay of Quinté to a place in the county of Prince Edward, known then as the Stone Mills, and afterwards as Glenora, where he built a grist-mill. This undertaking, however, did not prosper, and in 1836 he returned to Kingston, where he obtained a post in the Commercial Bank. Shortly afterwards he fell into ill health, and in 1841 he died.

Few places in the wide Dominion of Canada possess greater charm than the lovely arm of Lake Ontario beside whose pleasant waters Sir John Macdonald spent the days of his early boyhood. The settlements had been founded by Loyalists who had left the United States rather than join in revolution. The lad lived in daily contact with men who had {5} given the strongest possible testimony of their loyalty, in relinquishing all that was dear to them rather than forswear allegiance to their king, and it is not surprising that he imbibed, in the morning of life, those principles of devotion to the crown and to British institutions which regulated every stage of his subsequent career. To the last he never forgot the Bay of Quinté, and whenever I passed through that charming locality in his company he would speak with enthusiasm of the days when he lived there. He would recall some event connected with each neighbourhood, until, between Glasgow and Kingston, Adolphustown, Hay Bay, and the Stone Mills, it was hard to tell what was his native place. I told him so one day, and he laughingly replied: 'That's just what the Grits say. The Globe has it that I am born in a new place every general election!'

When Hugh Macdonald moved from Hay Bay to the Stone Mills, his son John, then about ten years of age, returned to Kingston to pursue his studies. He attended the grammar school in that town until he reached the age of fifteen, when he began the world for himself. Five years at a grammar school was all the formal education Sir John {6} Macdonald ever enjoyed. To reflect upon the vast fund of knowledge of all kinds which he acquired in after years by his reading, his observation, and his experience, is to realize to the full the truth of the saying, that a man's education often begins with his leaving school. He always regretted the disadvantages of his early life. 'If I had had a university education,' I heard him say one day, 'I should probably have entered upon the path of literature and acquired distinction therein.' He did not add, as he might have done, that the successful government of millions of men, the strengthening of an empire, the creation of a great dominion, call for the possession and exercise of rarer qualities than are necessary to the achievement of literary fame.

In 1830 Macdonald, then fifteen years of age, entered upon the study of law in the office of George Mackenzie of Kingston, a close friend of his father, with whom also he lodged. In 1832 Mackenzie opened a branch office in the neighbouring town of Napanee, to which place Macdonald was occasionally sent to look after the business. In 1833, by an arrangement made between Mackenzie and L. P. Macpherson—a relative of the Macdonalds—young {7} Macdonald was sent to Picton, to take charge of Macpherson's law-office during his absence from Canada.

On being called to the bar in 1836, Macdonald opened an office in Kingston and began the practice of law on his own account. In the first year of his profession, there entered his office as student a lad destined to become, in Ontario, scarcely less eminent than himself. This was Oliver Mowat, the son of Macdonald's intimate personal and political friend, John Mowat of Kingston. Oliver Mowat studied law four years with Macdonald, leaving his office in 1840. About the same time another youth, likewise destined to achieve more than local celebrity as Sir Alexander Campbell, applied for admission to the office. Few circumstances in the political history of Canada have been more dwelt upon than this noteworthy association; few are more worthy of remark. A young man, barely twenty-one years of age, without any special advantages of birth or education, opens a law-office in Kingston, at that time a place of less than five thousand inhabitants. Two lads come to him to study law. The three work together for a few years. They afterwards go into politics. One drifts away {8} from the other two, who remain closely allied. After the lapse of twenty-five years the three meet again, at the Executive Council Board, members of the same Administration. Another twenty-five years roll by, and the principal is prime minister of Canada, while one of the students is lieutenant-governor of the great province of Ontario, the other his chief adviser, and all three are decorated by Her Majesty for distinguished services to the state.

The times were rough. In Macdonald's first case, which was at Picton, he and the opposing counsel became involved in an argument, which, waxing hotter and hotter, culminated in blows. They closed and fought in open court, to the scandal of the judge, who immediately instructed the crier to enforce order. This crier was an old man, personally much attached to Macdonald, in whom he took a lively interest. In pursuance of his duty, however, he was compelled to interfere. Moving towards the combatants, and circling round them, he shouted in stentorian tones, 'Order in the court, order in the court!' adding in a low, but intensely sympathetic voice as he passed near his protégé, 'Hit him, John!' I have heard Sir John Macdonald {9} say that, in many a parliamentary encounter of after years, he has seemed to hear, above the excitement of the occasion, the voice of the old crier whispering in his ear the words of encouragement, 'Hit him, John!'

In 1837 the rebellion broke out, and Macdonald hastened to give his services to the cause of law and order. 'I carried my musket in '37,' he was wont to say in after years. One day he gave me an account of a long march his company made, I forget from what place, but with Toronto as the objective point. 'The day was hot, my feet were blistered—I was but a weary boy—and I thought I should have dropped under the weight of the flint musket which galled my shoulder. But I managed to keep up with my companion, a grim old soldier, who seemed impervious to fatigue.'

In 1838 took place the notorious Von Shoultz affair, about which much misunderstanding exists. The facts are these. During the rebellion of 1837-38 a party of Americans crossed the border and captured a windmill near Prescott, which they held for eight days. They were finally dislodged, arrested, and tried by court-martial. The quartermaster of the insurgents was a man named Gold. He {10} was taken, as was also Von Shoultz, a Polish gentleman. Gold had a brother-in-law in Kingston, named Ford. Ford was anxious that some effort should be made to defend his relative. Leading lawyers refused the service. One morning Ford came to Macdonald's house before he was up. After much entreaty he persuaded Macdonald to undertake the defence. There could be practically no defence, however, and Von Shoultz, Gold, and nine others were condemned and hanged. Von Shoultz's career had been chequered. He was born in Cracow. His father, a major in a Cracow regiment, was killed in action while fighting for the cause of an independent Poland, and on the field of battle his son was selected by the corps to fill his father's place. He afterwards drifted about Europe until he reached Florence, where he taught music for a while. There he married an English girl, daughter of an Indian officer, General Mackenzie. Von Shoultz subsequently crossed to America, settled in Virginia, took out a patent for crystallizing salt, and acquired some property. The course of business took him to Salina, N.Y., not far from the Canadian boundary, where he heard of the rebellion going on in Canada. He not unnaturally {11} associated the cause of the rebels with that of his Polish brethren warring against oppression. He had been told that the Canadians were serfs, fighting for liberty. Fired with zeal for such a cause, he crossed the frontier with a company and was captured. He was only second in command, the nominal chief being a Yankee named Abbey, who tried to run away, and who, Von Shoultz declared to Macdonald, was a coward.

Von Shoultz left to Macdonald a hundred dollars in his will. 'I wish my executors to give Mr John A. Macdonald $100 for his kindness to me.' This was in the original draft, but Macdonald left it out when reading over the will for his signature. Von Shoultz observed the omission, and said, 'You have left that out.' Macdonald replied yes, that he would not take it. 'Well,' replied Von Shoultz, 'if it cannot be done one way, it can another.' So he wrote with his own hand a letter of instructions to his executors to pay this money over, but Macdonald refused to accept it.

It has been generally stated that it was the 'eloquent appeal' on behalf of this unfortunate man which established Macdonald's reputation at the bar, but this is quite a mistake. {12} Macdonald never made any speech in defence of Von Shoultz, for two very good reasons. First, the Pole pleaded guilty at the outset; and, secondly, the trial was by court-martial, on which occasions, in those days, counsel were not allowed to address the court on behalf of the prisoner.

This erroneous impression leads me to say that a good deal of misapprehension exists respecting the early manhood of Canada's first prime minister. He left school, as we have seen, at an age when many boys begin their studies. He did this in order that he might assist in supporting his parents and sisters, who, from causes which I have indicated, were in need of his help. The responsibility was no light one for a lad of fifteen. Life with him in those days was a struggle; and all the glamour with which writers seek to invest it, who begin their accounts by mysterious allusions to the mailed barons of his line, is quite out of place. His grandfather was a merchant in a Highland village. His father served his apprenticeship in his grandfather's shop, and he himself was compelled to begin the battle of life when a mere lad. Sir John Macdonald owed nothing to birth or fortune. He did not think little of either of them, but it is the {13} simple truth to say that he attained the eminent position which he afterwards occupied solely by his own exertions. He was proud of this fact, and those who thought to flatter him by asserting the contrary little knew the man. Nor is it true that he leaped at one bound into the first rank of the legal profession. On the contrary, I believe that his progress at the bar, although uniform and constant, was not extraordinarily rapid. He once told me that he was unfortunate, in the beginning of his career, with his criminal cases, several of his clients, of whom Von Shoultz was one, having been hanged. This piece of ill luck was so marked that somebody (I think it was William Henry Draper, afterwards chief justice) said to him, jokingly, one day, 'John A., we shall have to make you attorney-general, owing to your success in securing convictions!'

Macdonald's mother was in many ways a remarkable woman. She had great energy and strength of will, and it was she, to use his own words, who 'kept the family together' during their first years in Canada. For her he ever cherished a tender regard, and her death, which occurred in 1862, was a great grief to him.

The selection of Kingston by Lord Sydenham in 1840 as the seat of government of the united provinces of Canada was a boon to the town. Real property advanced in price, some handsome buildings were erected, apart from those used as public offices, and a general improvement in the matter of pavements, drains, and other public utilities became manifest. Meanwhile, however, Toronto had far outstripped its sometime rival. In 1824 the population of Toronto (then York) had been less than 1700, while that of Kingston had been about 3000, yet in 1848 Toronto counted 23,500 inhabitants to Kingston's 8400. Still, Kingston jogged along very comfortably, and Macdonald added steadily to his reputation and practice. On September 1, 1843, he formed a partnership with his quondam student Alexander Campbell, who had just been admitted to the bar. It was not long before Macdonald became prominent as a citizen of Kingston. In March 1843 he was elected to the city council for what is now a portion of Frontenac and Cataraqui wards. But a higher destiny awaited him.

The rebellion which had broken out in Lower Canada and spread to the upper {15} province, while the future prime minister was quietly applying himself to business, had been suppressed. In Upper Canada, indeed, it had never assumed a serious character. Its leaders, or some of them at any rate, had received the reward of their transgressions. Lord Durham had come to Canada, charged with the arduous duty of ascertaining the cause of the grave disorders which afflicted the colony. He had executed his difficult task with rare skill, but had gone home broken-hearted to die, leaving behind him a report which will ever remain a monument no less to his powers of observation and analysis than to the clearness and vigour of his literary style.[1] The {16} union of Upper and Lower Canada, advocated by Lord Durham, had taken place. The seat of government had been fixed at Kingston, and the experiment of a united Canada had begun.

We have seen that Macdonald, at the outbreak of the rebellion, hastened to place his military services at the disposal of the crown. On the restoration of law and order we find his political sympathies ever on the side of what used to be called the governor's party. This does not mean that at any time of his career he was a member of, or in full sympathy with, the high Toryism of the 'Family Compact.' In those days he does not even seem to have classed himself as a Tory.[2] Like many moderate men in the province, Macdonald sided with this party because he hated sedition. The members of the 'Family {17} Compact' who stood by the governor were devotedly loyal to the crown and to monarchical institutions, while the violent language of some of the Radical party alienated many persons who, while they were not Tories, were even less disposed to become rebels.

The exacting demands of his Radical advisers upon the governor-general at this period occasionally passed all bounds. One of their grievances against Sir Charles Metcalfe was that he had ventured to appoint on his personal staff a Canadian gentleman bearing the distinguished name of deSalaberry, who happened to be distasteful to LaFontaine. In our day, of course, no minister could dream of interfering, even by way of suggestion, with a governor-general in the selection of his staff. In 1844, when the crisis came, and Metcalfe appealed to the people of Canada to sustain him, Macdonald sought election to the Assembly from Kingston. It was his 'firm belief,' he announced at the time, 'that the prosperity of Canada depends upon its permanent connection with the mother country'; and he was determined to 'resist to the utmost any attempt (from whatever quarter it may come) which may tend to {18} weaken that union.' He was elected by a large majority.

In the same year, the year in which Macdonald was first elected to parliament, another young Scotsman, likewise to attain great prominence in the country, made his début upon the Canadian stage. On March 5, 1844, the Toronto Globe began its long and successful career under the guidance of George Brown, an active and vigorous youth of twenty-five, who at once threw himself with great energy and conspicuous ability into the political contest that raged round the figure of the governor-general. Brown's qualities were such as to bring him to the front in any labour in which he might engage. Ere long he became one of the leaders of the Reform party, a position which he maintained down to the date of his untimely death at the hands of an assassin in 1880. Brown did not, however, enter parliament for some years after the period we are here considering.

The Conservative party issued from the general elections of 1844 with a bare majority in the House, which seldom exceeded six and sometimes sank to two or three. Early in that year the seat of government had been removed from Kingston to Montreal. The first {19} session of the new parliament—the parliament in which Macdonald had his first seat—was held in the old Legislative Building which occupied what was afterwards the site of St Anne's Market. In those days the residential quarter was in the neighbourhood of Dalhousie Square, the old Donegana Hotel on Notre Dame Street being the principal hostelry in the city. There it was that the party chiefs were wont to forgather. That Macdonald speedily attained a leading position in the councils of his party is apparent from the fact that he had not been two years and a half in parliament when the prime minister, the Hon. W. H. Draper, wrote him (March 4, 1847) requesting his presence in Montreal. Two months later Macdonald was offered and accepted a seat in the Cabinet.

Almost immediately after Macdonald's admission to the Cabinet, Draper retired to the bench. He was succeeded by Henry Sherwood, a scion of the 'Family Compact,' whose term of office was brief. The elections came on during the latter part of December, and, as was very generally expected,[3] the {20} Sherwood Administration went down to defeat. In Lower Canada the Government did not carry a single French-Canadian constituency, and in Upper Canada they failed of a majority, taking only twenty seats out of forty-two. In accordance with the more decorous practice of those days, the Ministry, instead of accepting their defeat at the hands of the press, met parliament like men, and awaited the vote of want of confidence from the people's representatives. This was not long in coming; whereupon they resigned, and the Reform leaders Baldwin and LaFontaine reigned in their stead.

The events of the next few years afford a striking example of the mutability of political life. Though this second Baldwin-LaFontaine Administration was elected to power by a large majority—though it commanded more than five votes in the Assembly to every two of the Opposition—yet within three years both leaders had withdrawn from public life, and Baldwin himself had sustained a personal defeat at the polls. The Liberal Government, reconstituted under Sir Francis Hincks, managed to retain office for three years more; but it was crippled throughout its whole term by the most bitter internecine feuds, and it fell {21} at length before the assaults of those who had been elected to support it. The measure responsible more than any other for the excited and bitter feeling which prevailed was the Rebellion Losses Bill. There is reason to believe that the members of the Government, or at any rate the Upper-Canadian ministers, were not at any time united in their support of the Bill. But the French vehemently insisted on it, and the Ministry, dependent as it was on the Lower-Canadian vote for its existence, had no choice. The Bill provided, as the title indicates, for compensation out of the public treasury to those persons in Lower Canada who had suffered loss of property during the rebellion. It was not proposed to make a distinction between loyalists and rebels, further than by the insertion of a provision that no person who had actually been convicted of treason, or who had been transported to Bermuda, should share in the indemnity. Now, a large number of the people of Lower Canada had been more or less concerned in the rebellion, but not one-tenth of them had been arrested, and only a small minority of those arrested had been brought to trial. It is therefore easy to see that the proposal was calculated {22} to produce a bitter feeling among those who looked upon rebellion as the most grievous of crimes. It was, they argued, simply putting a premium on treason. The measure was fiercely resisted by the Opposition, and called forth a lively and acrimonious debate. Among its strongest opponents was Macdonald. According to his custom, he listened patiently to the arguments for and against the measure, and did not make his speech until towards the close of the debate.

Despite the protests of the Opposition, the Bill passed its third reading in the House of Assembly on March 9, 1849, by a vote of forty-seven to eighteen. Outside the walls of parliament the clamour grew fiercer every hour. Meetings were held all over Upper Canada and in Montreal, and petitions to Lord Elgin, the governor-general, poured in thick and fast, praying that the obnoxious measure might not become law. In Toronto some disturbances took place, during which the houses of Baldwin, Blake, and other prominent Liberals were attacked, and the Reform leaders were burned in effigy.

The Government, which all along seems to have underrated public feeling, was so unfortunate as to incur the suspicion of {23} deliberately going out of its way to inflame popular resentment. It was considered expedient, for commercial reasons, to bring into operation immediately a customs law, and the Ministry took the unwise course of advising the governor-general to assent to the Rebellion Losses Bill at the same time. Accordingly, on April 25, Lord Elgin proceeded to the Parliament Buildings and gave the royal assent to these and other bills. Not a suspicion of the governor's intention had got abroad until the morning of the eventful day. His action was looked upon as a defiance of public sentiment; the popular mind was already violently excited, and consequences of the direst kind followed. His Excellency, when returning to his residence, 'Monklands,' was grossly insulted, his carriage was almost shattered by stones, and he himself narrowly escaped bodily injury at the hands of the infuriated populace. A public meeting was held that evening on the Champs de Mars, and resolutions were adopted praying Her Majesty to recall Lord Elgin. But no mere passing of resolutions would suffice the fiercer spirits of that meeting. The cry arose—'To the Parliament Buildings!' and soon the lurid flames mounting on the night air told {24} the horror-stricken people of Montreal that anarchy was in their midst. The whole building, including the legislative libraries, which contained many rare and priceless records of the colony, was destroyed in a few minutes.

This abominable outrage called for the severest censure, not merely on the rioters, but also on the authorities, who took few steps to avert the calamity. An eyewitness stated that half a dozen men could have extinguished the fire, which owed its origin to lighted balls of paper thrown about the chamber by the rioters; but there does not seem to have been even a policeman on the ground. Four days afterwards the Government, still disregarding public sentiment, brought the governor-general to town to receive an address voted to him by the Assembly. The occasion was the signal for another disturbance. Stones were thrown at Lord Elgin's carriage; and missiles of a more offensive character were directed with such correctness of aim that the ubiquitous reporter of the day described the back of the governor's carriage as 'presenting an awful sight.' Various societies, notably St Andrew's Society of Montreal, passed resolutions removing Lord Elgin from the presidency or patronage of their {25} organizations; some of them formally expelled him. On the other hand, he received many addresses from various parts of the country expressive of confidence and esteem. Sir Allan MacNab and William Cayley repaired to England to protest, on behalf of the Opposition, against the governor's course. They were closely followed by Francis Hincks, representing the Government. The matter duly came up in the Imperial parliament. In the House of Commons the Bill was vigorously attacked by Gladstone, who shared the view of the Canadian Opposition that it was a measure for the rewarding of rebels. It was defended by Lord John Russell, and Lord Elgin's course in following the advice of his ministers was ultimately approved by the home government.

As in many another case, the expectation proved worse than the reality. The commission appointed by the Government under the Rebellion Losses Act was composed of moderate men, who had the wisdom to refuse compensation to many claimants on the ground of their having been implicated in the rebellion, although never convicted by any court. Had it been understood that the restricted interpretation which the commission gave the Bill would be applied, it is possible that this {26} disgraceful episode in the history of Canada would not have to be told.

An inevitable consequence of this lamentable occurrence was the removal of the seat of government from Montreal. The Administration felt that, in view of what had taken place, it would be folly to expose the Government and parliament to a repetition of these outrages. This resolve gave rise to innumerable jealousies on the part of the several cities which aspired to the honour of having the legislature in their midst. Macdonald was early on the look-out, and, at the conclusion of his speech on the disturbances, in the course of which he severely censured the Ministry for its neglect to take ordinary precautions to avert what it should have known was by no means an unlikely contingency, he moved that the seat of government be restored to Kingston—a motion which was defeated by a large majority, as was a similar proposal in favour of Bytown (Ottawa). It was finally determined to adopt the ambulatory system of having the capital alternately at Quebec and Toronto, a system which prevailed until the removal to Ottawa in 1865.[4]

The historic Annexation manifesto of 1849 was an outcome of the excitement produced by the Rebellion Losses Act. Several hundreds of the leading citizens of Montreal, despairing of the future of a country which could tolerate such legislation as they had recently witnessed, affixed their names to a document advocating a friendly and peaceable separation from British connection as a prelude to union with the United States. Men subsequently known as Sir John Rose, Sir John Caldwell Abbott, Sir Francis Johnson, Sir David Macpherson, together with such well-known citizens as the Redpaths, the Molsons, the Torrances, and the Workmans, were among the number.

Macdonald, referring in later years to this Annexation manifesto, observed:

Our fellows lost their heads. I was pressed to sign it, but refused and advocated the formation of the British America League as a more sensible procedure. From all parts of Upper Canada, and from the British section of Lower Canada, and {28} from the British inhabitants of Montreal, representatives were chosen. They met at Kingston for the purpose of considering the great danger to which the constitution of Canada was exposed. A safety-valve was found. Our first resolution was that we were resolved to maintain inviolate the connection with the mother country. The second proposition was that the true solution of the difficulty lay in the confederation of all the provinces. The third resolution was that we should attempt to form in such confederation, or in Canada before Confederation, a commercial national policy. The effects of the formation of the British America League were marvellous. Under its influence the annexation sentiment disappeared, the feeling of irritation died away, and the principles which were laid down by the British America League in 1850 are the lines on which the Conservative-Liberal party has moved ever since.

The carrying of the Rebellion Losses Bill was the high-water mark of the LaFontaine-Baldwin Administration. In the following session symptoms of disintegration began to {29} appear. Grown bold by success, the advanced section of the Upper-Canadian Radicals pressed for the immediate secularization of the Clergy Reserves[5] by a process scarcely distinguishable from confiscation. To this demand the Government was not prepared to agree, and in consequence there was much disaffection in the Reform ranks. This had its counterpart in Lower Canada, where Louis Joseph Papineau and his Parti Rouge clamoured for various impracticable constitutional changes, including a general application of the elective principle, a republican form of government, and, ultimately, annexation to the United States.

To add to the difficulties of the situation, George Brown, in the columns of the Globe, which up to this time was supposed to reflect the views of the Government, began a furious onslaught against Roman Catholicism in general and on the French Canadians in particular. This fatuous course could not fail to prove embarrassing to a Ministry which drew its main support from Lower Canada. {30} It was the time of the 'Papal Aggression' in England. Anti-Catholicism was in the air, and found a congenial exponent in George Brown, whose vehement and intolerant nature espoused the new crusade with enthusiasm. It is difficult for any one living in our day to conceive of the leading organ of a great political party writing thus of a people who at that time numbered very nearly one-half the population of Canada, and from whose ranks the parliamentary supporters of its own political party were largely drawn:

It would give us great pleasure to think that the French Canadians were really hearty coadjutors of the Upper-Canadian Reformers, but all the indications point the other way, and it appears hoping against hope to anticipate still; their race, their religion, their habits, their ignorance, are all against it, and their recent conduct is in harmony with these.[6]

The Ministry could not be expected to stand this sort of thing indefinitely. They were {31} compelled to disavow the Globe, and so to widen the breach between them and Brown.

In 1851 Baldwin and LaFontaine retired from public life. A new Administration was formed from the same party under the leadership of Hincks and Morin, and in the general elections that followed George Brown was returned to parliament for Kent. The new Ministry, however, found no more favour at the hands of Brown than did its predecessor. Nor was Brown content to confine his attacks to the floor of the House. He wrote and published in the Globe a series of open letters addressed to Hincks, charging him with having paltered away his Liberal principles for the sake of French-Canadian support. To such lengths did Brown carry his opposition, that in the general elections of 1854 we find him, together with the extreme Liberals, known as Rouges, in Lower Canada, openly supporting the Conservative leaders against the Government.

While Brown was thus helping on the disruption of his party, his future great rival, by a very different line of conduct, was laying broad and deep the foundations of a policy tending to ameliorate the racial and religious differences unfortunately existing between {32} Upper and Lower Canada.[7] To a man of Macdonald's large and generous mind the fierce intolerance of Brown must have been in itself most distasteful. At the same time, there is no doubt that George Brown's anti-Catholic, anti-French crusade, while but one factor among several in contributing to the downfall of the Baldwin and Hincks Governments, became in after years, when directed against successive Liberal-Conservative Administrations, the most formidable obstacle against which Macdonald had to contend.

The result of the Globe's propaganda amounted to this, that for twenty years the Conservative leader found himself in a large minority in his own province of Upper Canada, and dependent upon Lower Canada for support—truly an unsatisfactory state of affairs to himself personally, and one most inimical to the welfare of the country. It was not pleasant for a public man to be condemned, election after election, to fight a losing battle {33} in his home province, where he was best known, and to be obliged to carry his measures by the vote of his allies of another province. It is therefore not to be wondered at that Sir John Macdonald in his reminiscent moods sometimes alluded to these days, thus:

Had I but consented to take the popular side in Upper Canada, I could have ridden the Protestant horse much better than George Brown, and could have had an overwhelming majority. But I willingly sacrificed my own popularity for the good of the country, and did equal justice to all men.[8]

Scattered throughout his correspondence are several references of a similar tenor. I do not believe, however, that the temptation ever seriously assailed him. Indeed, we find that at every step in his career, when the opportunity presented itself for showing sympathy with the French Canadians in their struggle for the maintenance of their just rights, he invariably espoused their cause, not then a popular one. At the union of Upper and Lower Canada in 1841 there seems to have been a general disposition to hasten the {34} absorption of the French-Canadian people, so confidently predicted by Lord Durham. That nobleman declared with the utmost frankness that, in his opinion, the French Canadians were destined speedily to lose their distinctive nationality by becoming merged in the Anglo-Saxon communities surrounding them, and he conceived that nothing would conduce so effectually to this result as the union of Upper and Lower Canada. His successor, Lord Sydenham, evidently shared these views upon the subject, for his Cabinet did not contain a single French Canadian. In furtherance of this policy it was provided in the Union Act (1840) that all the proceedings of parliament should be printed in the English language only. At that time the French Canadians numbered more than one-half the people of Canada, and the great majority of them knew no other language than French. No wonder that this provision was felt by them to be a hardship, or that it tended to embitter them and to increase their hostility to the Union. Macdonald had not sat in parliament a month before the Government of which he was a supporter proposed and carried in the House of Assembly a resolution providing for the removal of this restriction. {35} During the ensuing two years the same Government opened negotiations (which came to nothing at the time) with certain leaders among the French Canadians looking towards political co-operation, and similar though equally fruitless overtures were made to them during the weeks following Macdonald's admission into the Draper Cabinet. This policy Macdonald had deliberately adopted and carried with him into Opposition.

In a letter outlining the political campaign of 1854, he says in so many words:

My belief is that there must be a material alteration in the character of the new House. I believe also that there must be a change of Ministry after the election, and, from my friendly relations with the French, I am inclined to believe my assistance would be sought.[9]

Meanwhile the cleavage in the Reform ranks was daily becoming wider. Indeed, as has been said, the Radical section of the Upper-Canadian representation, known as the Clear Grit party, were frequently to be found voting with the Conservative Opposition, with whom they had nothing in common save dislike and {36} distrust of the Government. The result of the elections of 1854 showed that no one of the three parties—the Ministerialists, the Opposition, or the Clear Grits and Lower-Canadian Rouges combined—had an independent majority. Upon one point, however, the two last-named groups were equally determined, namely, the defeat of the Government. This they promptly effected by a junction of forces. The leader of the regular Opposition, Sir Allan MacNab, was 'sent for.' But his following did not exceed forty, while the defeated party numbered fifty-five, and the extreme Radicals about thirty-five. It was obvious that no Ministry could be formed exclusively from one party; it was equally clear that the government of the country must be carried on. In these circumstances Sir Allan resolved upon trying his hand at forming a new Government. He first offered Macdonald the attorney-generalship for Upper Canada, and, availing himself of his young ally's 'friendly relations with the French,' entered into negotiations with A. N. Morin, the leader of the Lower-Canadian wing of the late Cabinet. Morin consented to serve in the new Ministry. The followers of MacNab and Morin together formed a majority of the {37} House. The French leader, however, was most anxious that his late allies in Upper Canada—Sir Francis Hincks and his friends—should be parties to the coalition. Hincks, while not seeing his way to join the new Administration, expressed his approval of the arrangements, and promised his support on the understanding that two of his political friends from Upper Canada should have seats in the new Government. This proposal was accepted by MacNab, and John Ross (son-in-law of Baldwin) and Thomas Spence were chosen. The basis of the coalition was an agreement to carry out the principal measures foreshadowed in the speech from the throne—including the abolition of the Seigneurial Tenure[10] and the secularization of the Clergy Reserves.

Such was the beginning of the great Liberal-Conservative party which almost constantly from 1854 to 1896 controlled the destinies of Canada. Its history has singularly borne out the contention of its founders, that in uniting as they did at a time when their co-operation was essential to the conduct of affairs, they {38} acted in the best interests of the country. For a long time there had not been any real sympathy between the French Liberal leaders, LaFontaine and Morin, and the Liberals of Upper Canada. After the echoes of the rebellion had died away these French Liberals became in reality the Conservatives of Lower Canada. The Globe repeatedly declared this. Their junction with MacNab and Macdonald was therefore a fusion rather than a coalition. The latter word more correctly describes the union between the Conservatives and the Moderate Reformers of Upper Canada. It was, however, a coalition abundantly justified by circumstances. The principal charge brought against the Conservative party at the time was that in pledging themselves to secularize the Clergy Reserves they were guilty of an abandonment of principle. But in 1854 this had ceased to be a party question. The progress of events had rendered it inevitable that these lands should be made available for settlement; and since this had to come, it was better that the change should be brought about by men who had already striven to preserve the rights of property acquired under the Clergy Reserve grants, rather than by those whose policy was little {39} short of spoliation. The propriety and reasonableness of all this was very generally recognized at the time, not merely by the supporters of MacNab and Macdonald, but also by their political opponents. A. A. Dorion, the Rouge leader, considered the alliance quite natural. Robert Baldwin and Francis Hincks both publicly defended it, and their course did much to cement the union between the Conservatives and those who, forty years after the events here set down, were known to the older members of the community as 'Baldwin Reformers.'

[1] The question of the authorship of Lord Durham's Report is one which all Canadians have heard debated from their youth up. No matter who may have composed the document, it was Lord Durham's opinions and principles that it expressed. Lord Durham signed it and took responsibility for it, and it very naturally and properly goes under his name. But in a review of my Memoirs of Sir John Macdonald the Athenaeum (January 12, 1895) said: 'He,' the author, 'repeats at second hand, and with the incorrectness of those who do not take the trouble to verify their references, that Lord Durham's report on Canada' was written by the nobleman whose name it bears. 'He could easily have ascertained that the author of the report which he commends was Charles Buller, two paragraphs excepted which were contributed by Gibbon Wakefield and R. D. Hanson.' Some years later, however, in a review of Mr Stuart Reid's book on Lord Durham, the same Athenaeum (November 3, 1906) observed: 'Mr Reid conclusively disposes of Brougham's malignant slander that the matter of Lord Durham's report on Canada came from a felon (Wakefield) and the style from a coxcomb (Buller). The latter, in his account of the mission, frequently alludes to the report, but not a single phrase hints that he was the author.'

[2] 'It is well known, sir, that while I have always been a member of what is called the Conservative party, I could never have been called a Tory, although there is no man who more respects what is called old-fogey Toryism than I do, so long as it is based upon principle' (Speech of Hon. John A. Macdonald at St Thomas, 1860).

[3] 'In '47 I was a member of the Canadian Government, and we went to a general election knowing well that we should be defeated' (Sir John A. Macdonald to the Hon. P. C. Hill, dated Ottawa, October 7, 1867).

[4] The dates of the first meetings of the Executive Council, held at the various seats of government, from the Union in 1841 till 1867, are as follows: at Kingston, June 11, 1841; at Montreal, July 1, 1844; at Toronto, November 13, 1849; at Quebec, October 22, 1851; at Toronto, November 9, 1855; at Quebec, October 21, 1859; at Ottawa, November 28, 1865.

[5] That is, that the land set apart by the Constitutional Act of 1791 'for the support and maintenance of a Protestant Clergy,' amounting to one-seventh of all the lands granted, should be taken over by the Government and thrown open for settlement.

[6] Globe, 1851. For further instances see Globe, February 9 and December 14, 1853; February 9, 18, 22 and November 5, 1856; August 7 and December 23, 1857.

[7] To all Conservatives who cherish the memory of Sir John Macdonald we bring the reminder that no leader ever opposed so sternly the attempt to divide this community on racial or religious lines' (Globe, November 10, 1900).

The Globe's latter-day estimate of Sir John Macdonald recalls the late Tom Reid's definition of a statesman—'a successful politician who is dead.'

[8] To a friend, dated Ottawa, April 20, 1869.

[9] See Pope's Memoirs of Sir John Macdonald, vol. i, p. 103.

[10] The seigneurial system was a survival of the French régime. The reader is referred to The Seigneurs of Old Canada by Professor Munro in the present Series.

The Liberal-Conservative Government formed in 1854 was destined to a long and successful career, though not without the usual inevitable changes. Very shortly after its accession to power, Lord Elgin, whose term of office had expired, was succeeded by Sir Edmund Head. The new governor-general was a man of rare scholastic attainments. During the previous seven years he had occupied the position of lieutenant-governor of New Brunswick, and he was to administer, for a like period, the public affairs of Canada acceptably and well. One thing, however, greatly interfered with his popularity and lessened his usefulness. A story was spread abroad that Sir Edmund Head had called the French Canadians 'an inferior race.' This, though it was not true, was often reiterated; and the French Canadians persisted in believing that Sir Edmund had made the remark—even after an explanation of what he really did say.

Early in 1855 Morin retired to the bench. His place in the Cabinet was filled by George Étienne Cartier, member for Verchères in the Assembly. Cartier had begun his political career in 1848 as a supporter of LaFontaine, but he was one of those who followed Morin in his alliance with the Conservatives. Now, on the withdrawal of his chief, he succeeded, in effect, to the leadership of the French-Canadian wing of the Government. The corresponding position from the English province was held by John A. Macdonald, for it was no secret at the time that Sir Allan MacNab, the titular leader, had seen his best days, and leaned heavily upon his friend the attorney-general for Upper Canada.

Under these circumstances were brought together the two men who for the ensuing eighteen years governed the country almost without intermission. During the whole of this long period they were, with but one trivial misunderstanding, intimate personal friends. That Sir John Macdonald entertained the warmest feelings of unbroken regard for his colleague, I know, for he told me so many times; and Cartier's correspondence plainly indicates that these sentiments were fully reciprocated.

Sir George Cartier was a man who devoted his whole life to the public service of his country. He was truthful, honest, and sincere, and commanded the respect and confidence of all with whom he came in contact. Had it not been for Sir George Cartier, it is doubtful whether the Dominion of Canada would exist to-day. He it was who faced at its inception the not unnatural French-Canadian distrust of the measure. It was his magnificent courage and resistless energy which triumphed over all opposition. Confederation was not the work of any one person. Macdonald, Brown, Tupper—each played his indispensable part; but assuredly not the least important share in the accomplishment of that great undertaking is to be ascribed to George Étienne Cartier.

Other public men of the period claim our brief attention. Sir Allan MacNab, the leader of the Conservative party, had had a long and diversified experience. He was born at Niagara in 1798, and at an early age took up the profession of arms. When the Americans attacked Toronto in 1813, Allan MacNab, then a boy at school, was one of a number selected to carry a musket. He afterwards entered the Navy and was rated as a {43} midshipman on board Sir James Yeo's ship on the Great Lakes. MacNab subsequently joined the 100th Regiment under Colonel Murray, and was engaged in the storming of Niagara. He was a member and speaker of the old House of Assembly of Upper Canada, and in 1841 was elected to the first parliament under the new Union. For sixteen years he continued to represent Hamilton, serving during a portion of the time as speaker of the Assembly. In 1860 he was elected a member of the Legislative Council, and was chosen speaker of that body a few months prior to his death in 1862. In 1854, as we have seen, he was called upon, as the recognized leader of the Opposition, to form the new Ministry. He thus became prime minister, an event that caused some grumbling on the part of younger spirits who thought Sir Allan rather a 'back number.' It has been charged against Sir John Macdonald that he at the time intrigued to accomplish his old chief's overthrow, but there is not a particle of truth in the statement. When forming his plans for the general elections of 1854, Macdonald thus wrote:

You say truly that we are a good deal hampered with 'old blood.' Sir Allan {44} will not be in our way, however. He is very reasonable, and requires only that we should not in his 'sere and yellow leaf' offer him the indignity of casting him aside. This I would never assent to, for I cannot forget his services in days gone by.[1]

Sir Allan was a Tory of the 'Family Compact' school, which with changed conditions was fast becoming an anachronism. He was at the same time a loyal and faithful public servant.

MacNab retired from the premiership in 1856 and was succeeded by Colonel (afterwards Sir) Étienne Taché, who had held Cabinet office continuously since 1848. Taché was a more moderate man than Sir Allan, without his ambition or intractability; but he does not appear to have been distinguished by any particular aptitude for public life, and the prominence he attained was in large measure the result of circumstance. He was, however, generally regarded as a safe man with no private interests to serve, and he was quite content to allow Macdonald and Cartier a free hand in the direction of public affairs. {45} Under their united guidance much was accomplished. During the first session after the formation of the Liberal-Conservative party the two great questions which had long distracted the united province of Canada—the Clergy Reserves and the Seigneurial Tenure—were settled on terms which were accounted satisfactory by all moderate and reasonable men. Both the measures which the Government introduced to adjust these matters were opposed at every stage by Brown, Dorion, and other professed champions of the popular will.[2] Brown, who had never forgotten the failure of the Conservative leaders to open negotiations with him on the defeat of the Hincks Government, vented his wrath alternately on the new Ministry and on the Roman Catholic Church, assailing both with amazing violence. Despite this unrestrained vehemence, impulsiveness, and lack of discretion, George Brown's great ability and intellectual power made him a formidable opponent, as the ministers learned to their cost.

{46} Meanwhile, as the different groups settled into their places, political parties in the legislature became more clearly defined. The French-Canadian ministerialists soon ceased to be regarded as anything but Conservatives; and while many of the Upper-Canadian supporters of the Government long continued to be known as 'Baldwin Reformers,' the line of separation between them and their Conservative allies grew fainter every day. It was inevitable that this should be so. Baldwin himself had disappeared. Hincks had left the country. John Ross, the leading member of the Liberal wing of the coalition, had resigned from the Cabinet. So it came to pass, after the withdrawal of Sir Allan MacNab, that many quondam Liberals grew to realize that there was no longer any reason why they should not unite under the leadership of the man who inspired equally the confidence and the regard of the whole party.

All this was gall and wormwood to Brown, who pursued Macdonald with a malignity which has no parallel in our happier times. Nor, it must be confessed, did Macdonald fail to retort. Though not a resentful person, nor one who could not control his feelings, he never disguised his personal antipathy {47} towards the man who had persistently and for many years misrepresented and traduced him. On one occasion Macdonald was moved to bring certain accusations against Brown's personal character. These, however, he failed to establish to the satisfaction of the special committee of parliament appointed to try the charge. This was the only time, as far as I know, when Brown got the better of his rival.

While the Liberal-Conservative forces were being consolidated under Macdonald and Cartier, a similar process was taking place in the Reform ranks under Dorion and Brown. Dorion was a distinguished member of the Montreal bar and a courtly and polished gentleman of unblemished reputation. He had become the leading member of the Parti Rouge on Papineau's retirement in 1854, and was now the chief of the few French Radicals in the Assembly. In like manner Brown assumed the leadership of the Clear Grits, the Radicals of Upper Canada.

While the politicians were thus busy, Canada continued to develop, if not at the rate to which we are accustomed in these later days, still at a fair pace. In 1851 the population of Upper Canada had been 952,000 and {48} that of Lower Canada 890,000. Of the cities Montreal boasted 58,000, Quebec 42,000, Toronto 31,000, and Kingston 12,000. By 1861 these figures had grown to 1,396,000 for Upper Canada, 1,111,000 for Lower Canada, and the cities had correspondingly increased. Montreal had now 90,000 people, Quebec 51,000, Toronto 45,000, and Kingston 14,000. The total revenue of Canada in 1855 amounted to $4,870,000, not half that of the single province of Ontario to-day, and the expenditure to $4,780,000.

Much had already been spent on the improvement of inland navigation, and the early fifties saw the beginning of a great advance in railway construction. The Intercolonial Railway to connect the Maritime Provinces with Canada was projected as early as in 1846, though inability to agree upon the route delayed construction many years. In 1853 the Grand Trunk was opened from Montreal to Portland in Maine. The Great Western (now a portion of the Grand Trunk system), running between the Niagara and Detroit rivers, was opened during the following year; and 1855 witnessed the completion of the Grand Trunk from Montreal to Brockville, and the Great Western from Toronto to {49} Hamilton. The Detroit river at that time marked the western limit of settlement in Canada. North and west stretched a vast lone land about which scarcely anything was known. The spirit of enterprise, however, was stirring. The expiry of certain trading privileges granted to the Hudson's Bay Company in 1838 offered the occasion for an inquiry by a committee of the Imperial House of Commons into the claims of the company to the immense region associated with its name. The Canadian Government accepted an invitation to be represented at this investigation, and in the early part of the year 1857 dispatched to England Chief Justice Draper as commissioner. The committee, which included such eminent persons as Lord John Russell, Lord Derby, and Mr Gladstone, reported to the effect that terms should be agreed upon between the company and the Imperial and Canadian governments, in order that the territory might be made available for settlement; but no further steps were then taken. The question was not to be settled until some years later.

About the same time certain adventurous spirits approached the Canadian Government with a suggestion to build a railway across {50} the prairies and through the Rocky mountains to the Pacific ocean. From Sir John Macdonald's papers it appears that a proposal of this nature was made to him in the early part of 1858. There is a letter addressed to Macdonald, dated at Kingston in January of that year, and signed 'Walter R. Jones.' In the light of subsequent events this letter is interesting. The writer suggests that the time has arrived to organize a company to build a railway 'through British American territory to the Pacific.' It would be some years, of course, before such a company could actually begin the work of construction; therefore action should begin at once. Nothing will be gained by delay, the writer points out; and if Canada does not seize the golden opportunity, it is probable that the United States will be first in the field with such a railway, 'as they are fully alive to the great benefit it would be to them, not only locally, but as a highway from Europe to China, India, and Australia.' This would greatly lessen the value of a Canadian and British railway, and would cause the enterprise to 'be delayed or entirely abandoned.' Thus Canada would lose, not only the through traffic and business of the railway, but also the {51} opportunity to open up the Great West to settlers, 'which of itself would be a great boon to Canada.'

The letter proceeds to say that, as the claims of the Hudson's Bay Company to the lands of the West are shortly to be extinguished, the railway company could secure the grant of a harbour on Vancouver Island and the privilege of 'working the coal mines there'; also, 'a grant of land along the proposed line of railway.' A subsidy should be obtained from the Imperial Government for 'a line of steamers from Vancouver Island to China, India, and Australia.' If the Canadian people would take up the matter with spirit and buy largely of the stock, and if the subject were laid before the merchants of London, 'there would be no difficulty in raising the required capital, say £15,000,000.' There can be no doubt that the line would pay. Any one looking at a map of the world can see that it would afford the shortest route between Europe and the East. The writer thinks that it would be well to start the nucleus of a company immediately so as to apply for a charter at the next session of the Canadian parliament. 'Of course,' he adds, 'in my humble circumstances it would be the height of folly to think of attempting {52} to organize or connect myself with such a vast undertaking unless I could get the countenance and support of some one in high standing.' Macdonald, however, deemed the proposal premature until the claims of the Hudson's Bay Company were disposed of. He was destined to carry it out many years later.

The question as to the seat of government proved in those days extremely troublesome, promising to vie with the now happily removed Clergy Reserves question, in frequently recurring to cause difficulty. The inconvenience of the ambulatory system under which the legislature sat alternately four years at Quebec and four years at Toronto was acknowledged by everybody, but it seemed impossible to agree upon any one place for the capital. Quebec, Montreal, Toronto, and Kingston all aspired to the honour, and the sectional jealousies among the supporters of the Ministry afforded periodical opportunities to the Opposition, of which they did not fail to take advantage. One ministerial crisis arising out of this dispute acquired exceptional prominence by reason of the fact that it led to what is known in Canadian history as the 'Double Shuffle.'

In the session of 1857 the Ministry proposed to submit the question to the personal decision of the queen, and introduced resolutions in the Assembly praying that Her Majesty would be graciously pleased to exercise the royal prerogative by the selection of some one place as the permanent capital of Canada. This reference to Her Majesty was fiercely opposed by the Clear Grits as being a tacit acknowledgment of Canada's unfitness to exercise that responsible government for which she had contended so long. The Globe, in a series of articles, denounced the 'very idea as degradation.' The motion was nevertheless carried by a substantial majority, and the address went home accordingly.

The harvest of 1857 proved a failure, and in the autumn of that year Canada passed through one of the most severe periods of financial depression with which she has ever been afflicted. The period between 1854 and 1856 saw great commercial activity. Vast sums of money had been spent in constructing railways. This outlay, three bountiful harvests, and the abnormally high prices of farm products caused by the Crimean War, combined to make a period of almost unexampled prosperity—a prosperity more {54} apparent than real. The usual reaction followed. Peace in Europe, coinciding with a bad harvest in Canada, produced the inevitable result. Every class and interest felt the strain. Nor did the Ministry escape. It was at this gloomy period that Colonel Taché, weary of office, relinquished the cares of state, and Macdonald became first minister. Two days after the new Ministry had taken office parliament was dissolved and writs were issued for a general election. The main issues in this contest, both forced by George Brown, were 'Representation by Population' and 'Non-sectarian Schools'—otherwise No Popery. These cries told with much effect in Upper Canada. 'Rep. by Pop.,' as it was familiarly called, had long been a favourite policy with Brown and the Globe. By the Union Act of 1840 the representation of Upper and Lower Canada in the Assembly was fixed at eighty-four, forty-two from each province. At that time Lower Canada had the advantage of population, and consequently a smaller representation than that to which it would have been entitled on the basis of numbers. But the French Canadians were content to abide by the compact, and on that score there was peace. As soon, however, as {55} the influx of settlers into Upper Canada turned the scale, the Globe began to agitate for a revision of the agreement. In the session of 1853 Brown condemned the system of equal representation, and moved that the representation of the people in parliament should be based upon population, without regard to any line of separation between Upper and Lower Canada. On this he was defeated, but with rare pertinacity he stuck to his guns, and urged his views upon the Assembly at every opportune and inopportune moment. The Macdonald-Cartier Government opposed the principle of representation by population because it was not in accord with the Union Act. That Act was a distinct bargain between Upper Canada and Lower Canada, and could not be altered without the consent of both. On the school question Macdonald took the ground that the clause granting separate schools to Roman Catholics was in the Common School Act long before he became a member of the government—having been placed there by Robert Baldwin—and that it would be unfair and unjust arbitrarily to take the privilege away. Moreover, he argued, on the authority of Egerton Ryerson, a Protestant clergyman and superintendent of {56} schools for Upper Canada, that the offending clause injured nobody, but, on the contrary, 'widens the basis of the common school system.'

This might be good logic, and inherently fair and just. All the same, the Globe conducted its campaign with such telling effect that three ministers lost their seats in the general elections of 1857, and the Clear Grits came out of the campaign in Upper Canada with a majority of six or eight.

In Lower Canada there was a different result. The appeals to sectional and religious prejudice, which wrought havoc in the ranks of the ministerial supporters in the upper province, had a contrary effect among the Rouges. Their alliance with the Clear Grit party wellnigh brought their complete overthrow. Dorion himself was elected, but his namesake J. B. E. Dorion, commonly known as l'enfant terrible, was unsuccessful, as also was Luther H. Holton, the leading English-speaking Liberal of the province. Other prominent Rouges such as Papin, Doutre, Fournier, and Letellier were given abundant leisure to deplore the fanaticism of George Brown. Cartier had the satisfaction of coming to the assistance of his colleague with {57} almost the whole representation of Lower Canada at his back.

This brings us to the historic incident of the 'Double Shuffle.' Shortly after the elections it became known that Her Majesty, in response to the request of the legislature, had chosen Ottawa as the seat of government. The announcement was somewhat prematurely made and gave rise to a good deal of dissatisfaction. This manifested itself when parliament met. In the early days of the session of 1858 a motion was carried in the Assembly to the effect that 'in the opinion of this House, the city of Ottawa ought not to be the permanent seat of government of this province.' Thereupon the Ministry promptly resigned, construing the vote as a slight upon Her Majesty, who had been asked to make the selection. The governor-general then sent for Brown and invited him to form a new Administration. What followed affords an admirable illustration of the character of George Brown. Though in an undoubted minority in a House fresh from the people, with Lower Canada almost unitedly opposed to him, Brown accepted the invitation of the governor-general. His only hope could have lain in a dissolution, and Sir Edmund Head {58} gave him to understand at the outset, both verbally and in writing, that on this he must not count. There are several examples in British political history, notably that of Lord Derby in 1858 and Disraeli in 1873, where statesmen in opposition, feeling that the occasion was not ripe for their purposes, have refused to take advantage of the defeat of the Ministry to which they were opposed. George Brown was not so constituted. Without attempting to weigh the chances of being able to maintain himself in power for a single week, he eagerly grasped the prize. Two days after his summons he and his colleagues were sworn into office and had assumed the functions of advisers of the crown. How accurately does this headlong impetuosity bear out Sir John Macdonald's estimate of the man![3]

The inevitable happened, and that speedily. Within a few hours the Assembly passed a vote of want of confidence in the new Ministry, and Brown and his colleagues, having been refused a dissolution, were compelled to resign. The governor-general sent for A. T. Galt, then {59} the able and popular member of the House from Sherbrooke in Lower Canada. But Galt declined the honour. The formation of a new Administration was then entrusted to Cartier, who, with the assistance of Macdonald, soon accomplished the task. Thus came into power the former Macdonald-Cartier Government, under the changed name of the Cartier-Macdonald Government, with personnel very slightly altered. Even this did not fill up the cup of Brown's humiliation. By their acceptance of office he and his colleagues had vacated their seats in the Assembly, and so found themselves outside the legislature for the remainder of the session. Those members of the Cartier-Macdonald Government, on the contrary, who had been members of the Macdonald-Cartier Government, did not vacate their seats by reason of their resumption of office. The Independence of Parliament Act of 1857 provided that

whenever any person holding the office of Receiver General, Inspector General, Secretary of the Province, Commissioner of Crown Lands, Attorney General, Solicitor General, Commissioner of Public Works, Speaker of the Legislative Council, {60} President of Committees of the Executive Council, Minister of Agriculture, or Postmaster General, and being at the same time a member of the Legislative Assembly or an elected member of the Legislative Council, shall resign his office, and within one month after his resignation accept any other of the said offices, he shall not thereby vacate his seat in the said Assembly or Council.

These words are clear. Any member of a government could resign his office and accept another within one month without vacating his seat in parliament. Thirty days had not elapsed since Macdonald had held the portfolio of attorney-general. There was, therefore, no legal necessity for his taking the sense of his constituents on resuming it. Elections no more in 1858 than now were run for the fun of the thing. One technical objection alone stood in the way. The Act says that if any member resign office, and within one month after his resignation accept any other of the said offices, he shall not thereby vacate his seat in the Assembly. It says nothing about the effect of accepting anew the office just demitted, though it seems only reasonable {61} to infer that, if the acceptance of a new office by a minister did not call for a fresh appeal to his constituents, a fortiori neither would the mere resumption of an office whose acceptance they had already approved. In the judgment of Macdonald and several of his colleagues there was no legal impediment to the direct resumption of their former offices, but a difference of opinion existed on the point, and, in order to keep clearly within the law, the ministers first accepted portfolios other than those formerly held by them. Thus, Cartier was first sworn in as inspector-general and Macdonald as postmaster-general. On the following day they resigned these portfolios and were appointed respectively to their old offices of attorney-general East and attorney-general West. Their colleagues in the Macdonald-Cartier Government underwent a similar experience.

The 'Double Shuffle' proved a source of acute dissatisfaction to Brown and his friends. The ministers were accused by them of having perverted an Act of Parliament to a sense it was never intended to bear. Their action in swearing to discharge duties which they never intended to perform was characterized as little short of perjury. They were, however, {62} sustained both by parliament and in the courts. Thirteen years later, no less a personage than Gladstone gave to the proceeding the sanction of his great authority. In order to qualify Sir Robert Collier, his attorney-general, for a seat on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, appointments to which were restricted to judges, he nominated him a justice of the Court of Common Pleas, in which Sir Robert took his seat, sat for a few days, resigned, and went on the Judicial Committee.[4]

The year 1858 saw the beginnings of a movement in the direction of Confederation. At an early period in the session Galt raised the question in an interesting speech. When he joined the Ministry, as inspector-general (finance minister), he again brought it forward. During recess a delegation consisting of Cartier, Galt, and John Ross proceeded to England with the object of discussing the subject with Her Majesty's government.

The ranks of the Reform Opposition at this time included D'Arcy M'Gee, William M'Dougall, and many other strong debaters, among them John Sandfield Macdonald, who had sat continuously in the Assembly since the Union—for Glengarry until the general elections of 1857, and then for Cornwall. At first he had been a Conservative, but he drifted into the Liberal ranks and remained there until after Confederation, despite periodic differences with George Brown. He opposed the Confederation movement. But we must not anticipate his career further than to say that his political attitude was at all times extremely difficult to define. That he himself would not demur to this estimate may be inferred from the fact that he was wont to describe himself, in his younger days, as a 'political Ishmaelite.' Though born and bred a Roman Catholic, he was not commonly regarded as an eminently devout member of that Church, of which he used laughingly to call himself 'an outside pillar.' The truth is that John Sandfield Macdonald was too impatient of restraint and too tenacious of his own opinions to submit to any authority. In no sense could he be called a party man.

Another member of the Opposition was the {64} young man we have already met as a student in Macdonald's law-office, afterwards Sir Oliver Mowat, prime minister of Ontario. Mowat was of a type very different to Sandfield Macdonald. He had been a consistent Reformer from his youth up. After a heated struggle, he had been elected to parliament for the South Riding of Ontario, in the general elections of 1857, over the receiver-general J. C. Morrison. On this occasion the electors were assured that the alternative presented to them was to vote for 'Mowat and the Queen' or 'Morrison and the Pope.' Mowat at once took a prominent position in the Liberal ranks, and formed one of George Brown's 'Short Administration.'

Among those who first entered parliament at the general elections of 1857 were Hector Langevin and John Rose. The former was selected to move the vote of want of confidence in the short-lived Brown-Dorion Administration. Rose at that time was a young and comparatively unknown lawyer of Montreal, in whom Macdonald had detected signs of great promise. Earlier in the same year he had accompanied Macdonald on an official mission to England. This was the beginning of a close personal friendship between the two {65} men, which lasted for more than thirty years and had no little bearing on Rose's future. On returning from England Macdonald appointed him solicitor-general for Lower Canada. In the ensuing election Rose stood for Montreal, against no less a personage than Luther H. Holton, and was elected. He was destined to fill the office of Finance minister of Canada, to become a baronet, an Imperial Privy Councillor, and a close friend of His Majesty King Edward VII, then Prince of Wales. It was believed that still higher marks of distinction were to be conferred upon him, when he died in 1888. It was said that Sir John Rose owed much of his success to the cleverness and charm of his wife. I have often heard Sir John Macdonald speak of her as a brilliant and delightful woman of the world, devoted at all times to her husband and his interests. This lady was originally Miss Charlotte Temple of Vermont. Before becoming the wife of John Rose she had been married and widowed. There had been a tragic event in her life. This was related to me by Sir John Macdonald substantially as I set it down here.