Title: Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Author: Various

Editor: Harry Bates

Release date: November 11, 2009 [eBook #30452]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

W. M. CLAYTON, Publisher HARRY BATES, Editor DR. DOUGLAS M. DOLD, Consulting Editor

That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid, by leading writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the Authors' League of America;

That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS MONTHLY, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE, WESTERN ADVENTURES, and WESTERN LOVE STORIES.

More than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

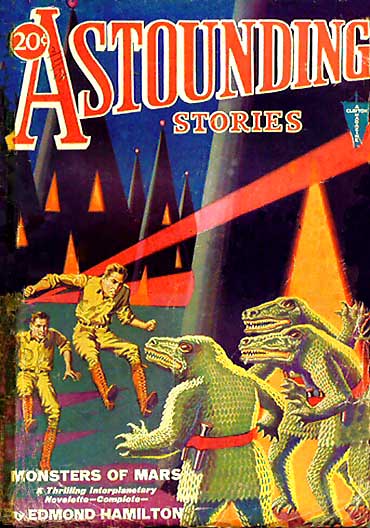

| COVER DESIGN | H. W. WESSO | ||

| Painted in Water-Colors from a Scene in "Monsters of Mars." | |||

| MONSTERS OF MARS | EDMOND HAMILTON | 4 | |

| Three Martian-Duped Earth-Men Swing Open the Gates of Space That for So Long Had Barred the Greedy Hordes of the Red Planet. (A Complete Novelette.) | |||

| THE EXILE OF TIME | RAY CUMMINGS | 26 | |

| From Somewhere Out of Time Come a Swarm of Robots Who Inflict on New York the Awful Vengeance of the Diabolical Cripple Tugh. (Beginning a Four-Part Novel.) | |||

| HELL'S DIMENSION | TOM CURRY | 51 | |

| Professor Lambert Deliberately Ventures into a Vibrational Dimension to Join His Fiancée in Its Magnetic Torture-Fields. | |||

| THE WORLD BEHIND THE MOON | PAUL ERNST | 64 | |

| Two Intrepid Earth-Men Fight It Out with the Horrific Monsters of Zeud's Frightful Jungles. | |||

| FOUR MILES WITHIN | ANTHONY GILMORE | 76 | |

| Far Down into the Earth Goes a Gleaming Metal Sphere Whose Passengers Are Deadly Enemies. (A Complete Novelette.) | |||

| THE LAKE OF LIGHT | JACK WILLIAMSON | 100 | |

| In the Frozen Wastes at the Bottom of the World Two Explorers Find a Strange Pool of White Fire—and Have a Strange Adventure. | |||

| THE GHOST WORLD | SEWELL PEASLEE WRIGHT | 118 | |

| Commander John Hanson Records Another of His Thrilling Interplanetary Adventures with the Special Patrol Service. | |||

| THE READERS' CORNER | ALL OF US | 134 | |

| A Meeting Place for Readers of Astounding Stories. | |||

Single Copies, 20 Cents (In Canada, 25 Cents) Yearly Subscription, $2.00

Issued monthly by Readers' Guild, Inc., 80 Lafayette Street, New York, N. Y. W. M. Clayton, President; Francis P. Pace, Secretary. Entered as second-class matter December 7, 1929, at the Post Office at New York, N. Y., under Act of March 3, 1879. Title registered as a Trade Mark in the U. S. Patent Office. Member Newsstand Group—Men's List. For advertising rates address E. R. Crowe & Co., Inc., 25 Vanderbilt Ave., New York; or 225 North Michigan Ave., Chicago.

The Martian gestured with a reptilian arm toward the

ladder.

The Martian gestured with a reptilian arm toward the

ladder.

llan Randall stared at the man before him. "And that's why you sent for me, Milton?" he finally asked.

There was a moment's silence, in which Randall's eyes moved as though uncomprehendingly from the face of Milton to those of the two men beside him. The four sat together at the end of a roughly furnished and electric-lit living-room, and in that momentary silence there came in to them from the outside night the distant pounding of the Atlantic upon the beach. It was Randall who first spoke again.

The other's face was unsmiling. "That's why I sent for you, Allan," he said quietly. "To go to Mars with us to-night!"

"To Mars!" he repeated. "Have you gone crazy, Milton—or is this some joke you've put up with Lanier and Nelson here?"

Milton shook his head gravely. "It is not a joke, Allan. Lanier and I are actually going to flash out over the[5] gulf to the planet Mars to-night. Nelson must stay here, and since we wanted three to go I wired you as the most likely of my friends to make the venture."

"But good God!" Randall exploded, rising. "You, Milton, as a physicist ought to know better. Space-ships and projectiles and all that are but fictionists' dreams."

"We are not going in either space-ship or projectile," said Milton calmly. And then as he saw his friend's bewilderment he rose and led the way to a door at the room's end, the other three following him into the room beyond.

t was a long laboratory of unusual size in which Randall found himself, one in which every variety of physical and electrical apparatus seemed represented. Three huge dynamo-motor arrangements took up the room's far end, and from them a tangle of wiring led through square black condensers and transformers to a battery of great tubes. Most remarkable, though, was the object at the room's center.

It was like a great double cube of dull metal, being in effect two metal cubes each twelve feet square, supported a few feet above the floor by insulated standards. One side of each cube was open, exposing the hollow interiors of the two cubical chambers. Other wiring led from the big electronic tubes and from the dynamos to the sides of the two cubes.

The four men gazed at the enigmatic thing for a time in silence. Milton's strong, capable face showed only in its steady eyes what feelings were his, but Lanier's younger countenance was alight[6] with excitement; and so too to some degree was that of Nelson. Randall simply stared at the thing, until Milton nodded toward it.

"That," he said, "is what will flash us out to Mars to-night."

Randall could only turn his stare upon the other, and Lanier chuckled. "Can't take it in yet, Randall? Well, neither could I when the idea was first sprung on us."

ilton nodded to seats behind them, and as the half-dazed Randall sank into one the physicist faced him earnestly.

"Randall, there isn't much time now, but I am going to tell you what I have been doing in the last two years on this God-forsaken Maine coast. I have been for those two years in unbroken communication by radio with beings on the planet Mars!

"It was when I still held my physics professorship back at the university that I got first onto the track of the thing. I was studying the variation of static vibrations, and in so doing caught steady signals—not static—at an unprecedentedly high wave-length. They were dots and dashes of varying length in an entirely unintelligible code, the same arrangement of them being sent out apparently every few hours.

"I began to study them and soon ascertained that they could be sent out by no station on earth. The signals seemed to be growing louder each day, and it suddenly occurred to me that Mars was approaching opposition with earth! I was startled, and kept careful watch. On the day that Mars was closest the earth the signals were loudest. Thereafter, as the red planet receded, they grew weaker. The signals were from some being or beings on Mars!

"At first I was going to give the news to the world, but saw in time that I could not. There was not sufficient proof, and a premature statement would only wreck my own scientific reputation. So I decided to study the signals farther until I had irrefutable proof, and to answer them if possible. I came up here and had this place built, and the aerial towers and other equipment I wanted set up. Lanier and Nelson came with me from the university, and we began our work.

ur chief object was to answer those signals, but it proved heartbreaking work at first. We could not produce a radio wave of great enough length to pierce out through earth's insulating layer and across the gulf to Mars. We used all the power of our great windmill-dynamo hook-ups, but for long could not make it. Every few hours like clockwork the Martian signals came through. Then at last we heard them repeating one of our own signals. We had been heard!

"For a time we hardly left our instruments. We began the slow and almost impossible work of establishing intelligent communication with the Martians. It was with numbers we began. Earth is the third planet from the sun and Mars the fourth, so three represented earth and four stood for Mars. Slowly we felt our way to an exchange of ideas, and within months were in steady and intelligent communication with them.

"They asked us first concerning earth, its climates and seas and continents, and concerning ourselves, our races and mechanisms and weapons. Much information we flashed out to them, the language of our communication being English, the elements, of which they had learned, with a mixture of numbers and symbolical dot-dash signals.

"We were as eager to learn about them. They were somewhat reticent, we found, concerning their planet and themselves. They admitted that their world was a dying one and that their great canals were to make life possible on it, and also admitted that they were different in bodily form from ourselves.

"They told us finally that communi[7]cation like this was too ineffective to give us a clear picture of their world, or vice versa. If we could visit Mars, and then they visit earth, both worlds would benefit by the knowledge of the other. It seemed impossible to me, though I was eager enough for it. But the Martians said that while spaceships and the like were impossible, there was a way by which living beings could flash from earth to Mars and back by radio waves, even as our signals flashed!"

andall broke in in amazement. "By radio!" he exclaimed, and Milton nodded.

"Yes, so they said, nor did the idea of sending matter by radio seem too insane, after all. We send sound, music by radio waves across half the world from our broadcasting stations. We send light, pictures, across the world from our television stations. We do that by changing the wave length of the light-vibrations to make them radio vibrations, flashing them out thus over the world, to receivers which alter their wave-lengths again and change them back into light-vibrations.

"Why then could not matter be sent in the same way? Matter, it has been long believed, is but another vibration of the ether, like light and radiant heat and radio vibrations and the like, having a lower wave-length than any of the others. Suppose we take matter and by applying electrical force to it change its wave-length, step it up to the wave-length of radio vibrations? Then those vibrations can be flashed forth from the sending station to a special receiver that will step them down again from radio vibrations to matter vibrations. Thus matter, living or non-living, could be flashed tremendous distances in a second!

his the Martians told us, and said they would set up a matter-transmitter and receiver on Mars and would aid and instruct us so that we could set up a similar transmitter and receiver here. Then part of us could be flashed out to Mars as radio vibrations by the transmitter, and in moments would have flashed across the gulf to the red planet and would be transformed back from radio vibrations to matter-vibrations by the receiver awaiting us there!

"Naturally we agreed enthusiastically to build such a matter-transmitter and receiver, and then, with their instructions signalled to us constantly, started the work. Weeks it took, but at last, only yesterday, we finished it. The thing's two cubical chambers are one for the transmitting of matter and the other for its reception. At a time agreed on yesterday we tested the thing, placing a guinea pig in the transmitting chamber and turning on the actuating force. Instantly the animal vanished, and in moments came a signal from the Martians saying that they had received it unharmed in their receiving chamber.

"Then we tested it the other way, they sending the same guinea pig to us, and in moments it flashed into being in our receiving chamber. Of course the step-down force in the receiving chamber had to be in operation, since had it not been at that moment the radio-vibrations of the animal would have simply flashed on endlessly in endless space. And the same would happen to any of us were we flashed forth and no receiving chamber turned on to receive us.

"We signalled the Martians that all tests were satisfactory, and told them that on the next night at exactly midnight by our time we would flash out ourselves on our first visit to them. They have promised to have their receiving chamber operating to receive us at that moment, of course, and it is my plan to stay there twenty-four hours, gathering ample proofs of our visit, and then flash back to earth.

"Nelson must stay here, not only to flash us forth to-night, but above all to have the receiving chamber operating to receive us at the destined mo[8]ment twenty-four hours later. The force required to operate it is too great to use for more than a few minutes at a time, so it is necessary above all that that force be turned on and the receiving chamber ready for us at the moment we flash back. And since Nelson must stay, and Lanier and I wanted another, we wired you, Randall, in the hope that you would want to go with us on this venture. And do you?"

s Milton's question hung, Randall drew a long breath. His eyes were on the two great cubical chambers, and his brain seemed whirling at what he had heard. Then he was on his feet with the others.

"Go? Could you keep me from going? Why, man, it's the greatest adventure in history!"

Milton grasped his hand, as did Lanier, and then the physicist shot a glance at the square clock on the wall. "Well, there's little enough time left us," he said, "for we've hardly an hour before midnight, and at midnight we must be in that transmitting chamber for Nelson to send us flashing out!"

Randall could never recall but dimly afterward how that tense hour passed. It was an hour in which Milton and Nelson went with anxious faces and low-voiced comments from one to another of the pieces of apparatus in the room, inspecting each carefully, from the great dynamos to the transmitting and receiving chambers, while Lanier quickly got out and made ready the rough khaki suits and equipment they were to take.

It lacked but a quarter-hour of midnight when they had finally donned those suits, each making sure that he was in possession of the small personal kit Milton had designated. This included for each a heavy automatic, a small supply of concentrated foods, and a small case of drugs chosen to counteract the rarer atmosphere and lesser gravity which Milton had been warned to expect on the red planet. Each had also a strong wrist-watch, the three synchronized exactly with the big laboratory clock.

hen they had finished checking up on this equipment the clock's longer hand pointed almost to the figure twelve, and the physicist gestured expressively toward the transmitting chamber. Lanier, though, strode for a moment to one of the laboratory's doors and flung it open. As Randall gazed out with him they could see far out over the tossing sea, dimly lit by the great canopy of the summer stars overhead. Right at the zenith among those stars shone brightest a crimson spark.

"Mars," said Lanier, his voice a half-whisper. "And they're waiting out there for us now—out there where we'll be in minutes!"

"And if they shouldn't be waiting—their receiving chamber not ready—"

But Milton's calm voice came across the room to them: "Zero hour," he said, stepping up into the big transmitting chamber.

Lanier and Randall slowly followed, and despite himself a slight shudder shook the latter's body as he stepped into the mechanism that in moments would send him flashing out through the great void as impalpable ether-vibrations. Milton and Lanier were standing silent beside him, their eyes on Nelson, who stood watchfully now at the big switchboard beside the chambers, his own gaze on the clock. They saw him touch a stud, and another, and the hum of the great dynamos at the room's end grew loud as the swarming of angry bees.

The clock's longer hand was crawling over the last space to cover the smaller hand. Nelson turned a knob and the battery of great glass tubes broke into brilliant white light, a crackling coming from them. Randall saw the clock's pointer clicking over the last divisions, and as he saw Nelson grip a great switch there came over him a wild impulse to bolt from the transmitting chamber. But then as his[9] thoughts whirled maelstromlike there came a clang from the clock and Nelson flung down the switch in his grasp. Blinding light seemed to break from all the chamber onto the three; Randall felt himself hurled into nothingness by forces titanic, inconceivable, and then knew no more.

andall came back to consciousness with a humming sound in his ears and with a sharp pain piercing his lungs at every breath. He felt himself lying on a smooth hard surface, and heard the humming stop and be succeeded by a complete silence. He opened his eyes, drawing himself to his feet as Milton and Lanier were doing, and stared about him.

He was standing with his two friends inside a cubical metal chamber almost exactly the same as the one they had occupied in Milton's laboratory a few moments before. But it was not the same, as their first astounded glance out through its open side told them.

For it was not the laboratory that lay around them, but a vast conelike hall that seemed to Randall's dazed eyes of dimensions illimitable. Its dull-gleaming metal walls slanted up for a thousand feet over their heads, and through a round aperture at the tip far above and through great doors in the walls came a thin sunlight. At the center of the great hall's circular floor stood the two cubical chambers in one of which the three were, while around the chambers were grouped masses of unfamiliar-looking apparatus.

o Randall's untrained eyes it seemed electrical apparatus of very strange design, but neither he nor Milton nor Lanier paid it but small attention in that first breathless moment. They were gazing in fascinated horror at the scores of creatures who stood silent amid the apparatus and at its switches, gazing back at them. Those creatures were erect and roughly man-like in shape, but they were not human men. They were—the thought blasted to Randall's brain in that horror-filled moment—crocodile-men.

Crocodile-men! It was only so that he could think of them in that moment. For they were terribly like great crocodile shapes that had learned in some way to carry themselves erect upon their hinder limbs. The bodies were not covered with skin, but with green bony plates. The limbs, thick and taloned at their paw-ends, seemed greater in size and stronger, the upper two great arms and the lower two the legs upon which each walked, while there was but the suggestion of a tail. But the flat head set on the neckless body was most crocodilian of all, with great fanged, hinged jaws projecting forward, and with dark unwinking eyes set back in bony sockets.

Each of the creatures wore on his torso a gleaming garment like a coat of metal scales, with metal belts in which some had shining tubes. They were standing in groups here and there about the mechanisms, the nearest group at a strange big switch-panel not a half-dozen feet from the three men. Milton and Lanier and Randall returned in a tense silence the unwinking stare of the monstrous beings around them.

"The Martians!" Lanier's horror-filled exclamation was echoed in the next instant by Randall's.

"The Martians! God, Milton! They're not like anything we know—they're reptilian!"

ilton's hand clutched his shoulder. "Steady, Randall," he muttered. "They're terrible enough, God knows—but remember we must seem just as grotesque to them."

The sound of their voices seemed to break the great hall's spell of silence, and they saw the crocodilian Martians before them turning and speaking swiftly to each other in low hissing speech-sounds that were quite unintelligible to the three. Then from the small group nearest them one came[10] forward, until he stood just outside the chamber in which they were.

Randall felt dimly the momentousness of the moment, in which beings of earth and Mars were confronting each other for the first time in the solar system's history. The creature before them opened his great jaws and uttered slowly a succession of sounds that for the moment puzzled them, so different were they from the hissing speech of the others, though with the same sibilance of tone. Again the thing repeated the sounds, and this time Milton uttered an exclamation.

"He's speaking to us!" he cried. "Trying to speak the English that I taught them in our communication! I caught a word—listen...."

As the creature repeated the sounds, Randall and Lanier started to hear also vaguely expressed in that hissing voice familiar words: "You—are Milton and—others from—earth?"

Milton spoke very clearly and slowly to the creature: "We are those from earth," he said. "And you are the Martians with whom we have communicated?"

"We are those Martians," said the other's hissing voice slowly. "These"—he waved a taloned paw toward those behind him—"have charge of the matter-transmitter and receiver. I am of our ruler's council."

"Ruler?" Milton repeated. "A ruler of all Mars?"

"Of all Mars," the other said. "Our name for him would mean in your words the Martian Master. I am to take you to him."

ilton turned to the other two with face alight with excitement. "These Martians have some supreme ruler they call the Martian Master," he said quickly; "and we're to go before him. As the first visitors from earth we're of immense importance here."

As he spoke, the Martian official before them had uttered a hissing call, and in answer to it a long shape of shining metal raced into the vast hall and halted beside them. It was like a fifty-foot centipede of metal, its scores of supporting short legs actuated by some mechanism inside the cylindrical body. There was a transparent-walled control room at the front end of that body, and in it a Martian at the controls who snapped open a door from which a metal ladder automatically descended.

The Martian official gestured with a reptilian arm toward the ladder, and Milton and Lanier and Randall moved carefully out of the cube-chamber and across the floor to it, each of their steps being made a short leap forward by the lesser gravity of the smaller planet. They climbed up into the centipede-machine's control room, their guide following, and then as the door snapped shut, the operator of the thing pulled and turned the knob in his grasp and the long machine scuttled forward with amazing smoothness and speed.

In a moment it was out of the building and into the feeble sunlight of a broad metal-paved street. About them lay a Martian city, seen by their eager eyes for the first time. It was a city whose structures were giant metal cones like that from which they had just come, though none seemed as large as that titanic one. Throngs of the hideous crocodilian Martians were moving busily to and fro in the streets, while among them there scuttled and flashed numbers of the centipede-machines.

s their strange vehicle raced along, Randall saw that the conelike structures were for the most part divided into many levels, and that inside some could be glimpsed ranks of great mechanisms and hurrying Martians tending them. Away to their right across the vast forest of cones that was the city the sun's little disk was shining, and he glimpsed in that direction higher ground covered with a vast tangle of bright crimson jungle[11] that sloped upward from a great, half-glimpsed waterway.

The Martian beside them saw the direction of his gaze and leaned toward him. "No Martians live there," he hissed slowly. "Martians live only in cities where canals meet."

"Then there's no life in those crimson jungles?" Randall asked, repeating the question a moment later more slowly.

"No Martians there, but life—living things," the other told him, searching for words. "But not intelligent, like Martians and you."

He turned to gaze ahead, then pointed. "The Martian Master's cone," he hissed.

The three saw that at the end of the broad metal street down which their vehicle was racing there loomed another titanic cone-structure, fully as large as the mighty one in which they first found themselves. As the centipede-machine swept up to its great door-opening and halted, they descended to the metal paving and then followed their reptilian guide through the opening.

hey found themselves in a great hall in which scores of the Martians were coming and going. At the hall's end stood a row of what seemed guards, Martians grasping shining tubes such as they had already glimpsed. These gave way to allow their passage when their conductor uttered a hissing order, and then they were moving down a shorter hall at whose end also were guards. As these sprang aside before them, a great door of massive metal they guarded moved softly upward, disclosing a mighty circular hall or room inside. Their crocodilian guide turned to them.

"The hall of the Martian Master," he hissed.

They passed inside with him. The great hall seemed to extend upward to the giant cone's tip, thin light coming down from an opening there. Upon the dull metal of its looming walls were running friezes of lighter metal, grotesque representations of reptilian shapes that they could but vaguely glimpse. Around the walls stood rank after rank of guards.

At the hall's center was a low dias, and in a semicircle around and behind it stood a half-hundred great crocodilian shapes. Randall guessed even at the moment that they were the council of which their conductor had named himself a member. But like Milton and Lanier, he had eyes in that first moment only for the dais itself. For on it was—the Martian Master.

Randall heard Milton and Lanier choke with the horror that shook his own heart and brain as he gazed. It was not simply another great crocodilian shape that sat upon that dais. It was a monstrous thing formed by the joining of three of the great reptilian bodies! Three distinct crocodile-like bodies sitting close together upon a metal seat, that had but a single great head. A great, grotesque crocodilian head that bulged backward and to either side, and that rested on the three thick short necks that rose from the triple body! And that head, that triple-bodied thing, was living, its unwinking eyes gazing at the three men!

he Martian Master! Randall felt his brain reel as he gazed at that mind-shattering thing. The Martian Master—this great head with three bodies! Reason told Randall, even as he strove for sanity, that the thing was but logical, that even on earth biologists had formed multiple-headed creatures by surgery, and that the Martians had done so to combine in one great head, one great brain, the brains of three bodies. Reason told him that the great triple brain inside that bulging head needed the bloodstreams of all three bodies to nourish it, must be a giant intellect indeed, one fitted to be the supreme Martian Master. But reason could not overcome the horror that choked him as he gazed at the awful thing.[12]

A hissing voice sounding before him made him aware that the Martian Master was speaking.

"You are the Earth-beings with whom we communicated, and whom we instructed to build a matter-transmitter and receiver on earth?" the slow voice asked. "You have come safely to Mars by means of that station?"

"We have come safely." Milton's voice was shaken and he could find no other words.

"That is well. Long had we desired to have such a station built on earth, since with it there to flash back and forth between the two worlds is easy. You have come, then, to learn of this world and to take back what you learn to your races?"

"That is why we came." Milton said, more steadily. "We want to stay only hours on this first visit, and then flash back to earth as we came."

he head's awful eyes seemed to consider them. "But when do you intend to go back?" its strange voice asked. "Unless the one at your earth station has its receiver operating at the right moment you will simply flash on endlessly as radio waves—will be annihilated."

Milton found the courage to smile. "We started from earth at our midnight exactly, and at midnight exactly twenty-four earth hours later, we are to flash back and the receiver will be awaiting us."

There was silence when he had said that, a silence that seemed to Randall's strained mind to have become suddenly tense, sinister. The great triple-bodied creature before them considered them again, its eyes moving over them, and when it again spoke the hissing words came very slowly.

"Twenty-four earth hours," it said; "and then your receiver on earth will be awaiting you. That time we can measure to the moment, and that is well. For it is not you three Earth-beings who will flash back to earth when that moment comes! It will be Martians, the first of our Martian masses who have waited for ages for that moment and who will begin then our conquest of the earth!

"Yes, Earth-beings, our great plan comes to its end now at last! At last! Age on age, prisoned on this dying, arid world, we have desired the earth that by right of power shall be ours, have sought for ages to communicate with its beings. You finally heard us, you hearkened to us, you built the matter-transmitting and receiving station on earth that was the one thing needed for our plan. For when the matter-receiver of that station is turned on in twenty-four of your hours, and ready to receive matter flashes from here, it will be the first of our millions who will flash at last to earth!

"I, the Martian Master, say it. Those first to go shall seize that matter-receiver on earth when first they appear there, shall build other and larger receivers, and through them within days all our Martian hordes shall have been flashed to earth! Shall have poured out over it and conquered with our weapons your weak races of Earth-beings, who cannot stand before us, and whose world you have delivered at last into our hands!"

For a moment, when the great monster's hissing voice had ceased, Milton and Randall and Lanier gazed toward it as though petrified, the whole unearthly scene spinning about them. And then, through the thick silence, the thin sound of Milton's voice:

"Our world—our earth—delivered to the Martians, and by us! God—no!"

With that last cry of agonized comprehension and horror, Milton did what surely had never any in the great hall expected, leaped onto the dais with a single spring toward the Martian Master! Randall heard a hundred wild hissing cries break from about him, saw the crocodilian forms of guards and council rushing forward even as he and Lanier sprang after Milton, and then glimpsed shining tubes levelled from which brilliant[13] shafts of dazzling crimson light or force were stabbing toward them!

o Randall the moment that followed was but a split-second flash and whirl of action. As his earthly muscles took him forward with Lanier after Milton in a great leap to the dais, he was aware of the brilliant red rays stabbing behind him closely, and knew that only the tremendous size of his leap had taken him past them. In the succeeding instant he was made aware of what he had escaped, for the hastily-loosed rays struck squarely a group of three or four Martian guards rushing to the dais from the opposite side, and they vanished from view with a sharp detonation as though clicked out of existence!

Randall was not to know then, that the red rays were ones that annihilated matter by neutralizing or damping the matter-vibrations in the ether. But he did know that no more rays were loosed, for by then he and Milton and Lanier were on the dais and were wrapped in a hurricane combat with the guards that had rushed between them and the Martian Master.

Gleaming fangs—great scaled forms—reaching talons—it was all a wild phantasmagoria of grotesque forms spinning around him as he struck with all the power of his earthly muscles and felt crocodilian forms staggering and going down beneath his frenzied blows. He heard the roar of an automatic close beside him in the melee as Milton remembered at last through the red haze of his fury the weapon he carried, but before either Randall or Lanier could reach their own weapons a new wave of crocodilian forms had poured onto them that by sheer pressing weight held them helpless, to be disarmed.

issing orders sounded, the arms and legs of the three were tightly grasped by great taloned paws, and the masses of Martians about them melted back from the dais. Held each by two great creatures, Milton and Randall and Lanier faced again the triple-bodied Martian Master, who in all that wild moment of struggle appeared not to have changed his position. The big monster's black eyes stared unmovedly down at them.

"You Earth-beings seem of lower intelligence even than we thought," his hissing voice informed them. "And those weapons—crude, very crude."

Milton, his face set, spoke back: "It may be that you will find human weapons of some power if your hordes reach earth," he said.

"But what compared with the power of ours?" the other asked coldly. "And since our scientists even now devise new weapons to annihilate the earth's races, I think they would be glad of three of those races to experiment with now. The one use we can make of you, certainly."

The creature turned its bulging head a little towards the guards who held the three men, and uttered a brief hissing order. Instantly the six Martians, grasping the three tightly, marched them across the great hall and through a different door than that by which they had entered.

They were taken down a narrow corridor that turned sharply twice as they went on. Randall saw that it was lit by squares inset in the walls that glowed with crimson light. It came to him as they marched on that night must be upon the Martian city without, since the sun had been sinking when they had crossed it in the centipede-machine.

hrough what seemed an ante-room they were taken, and then into a long hall instantly recognizable as a laboratory. There were many glowing squares illuminating it, and narrow windows high in the wall gave them a glimpse of the city outside, a pattern of crimson lights. Long metal tables and racks filled the big room's farther end, while along the walls were ranged shining mechanisms of un[14]familiar and grotesque appearance. Fully a score of the crocodilian Martians were busy in the room, some intent on their work at the racks and tables, others operating some of the strange machines.

The guards conducted the three to an open space by the wall, below one of the high window-openings and between two great cylindrical mechanisms. Then, while five of their number held the three men prisoned in that space by the threat of their levelled ray-tubes, the other moved toward one of the busy Martian scientists and held with him a brief interchange of hissing speech.

Milton leaned to whisper to the other two: "We've got to get out of this while we're still living," he whispered. "You heard the Martian Master—in constructing that matter-receiver on earth, we've opened a door through which all the Martian millions will pour onto our world!"

"It's useless, Milton," said Randall dully. "Even if we got clear of this the Martians will be at their matter-transmitter in hordes when the moment comes to flash back to earth."

"I know that, but we've got to try," the other insisted. "If we or some of us could get clear of this, we might in some way hide near the matter-transmitter until the moment came and then fight to it."

"But how to get out of the hands of these, even?" asked Lanier, nodding toward the alert guards before them.

here's but one way," Milton whispered swiftly. "Our earthly muscles would enable us, I think, to get through this window-opening above us in a leap, if we had a moment's chance. Well, whichever of us they take to experiment with or examine first, must make a struggle or disturbance that will turn the guards' attention for a moment and give the other two a chance to make the attempt!"

"One to stay and the other two to get away...." Randall said slowly; but Milton's tense whisper interrupted:

"It's the only way, and even then a thousand to one chance! But it's we who have opened this gate for the Martian invasion of our world and it's we who must—"

Before he could finish, the approach of hissing voices told them that the leader of the six guards and the Martian who seemed the chief of the experimenters in the hall were nearing them. The three men stood silent and tense as the two crocodilian monsters stopped before them. The scientist, who carried in his metal-belt, instead of a ray-tube a compact case of instruments, surveyed them as though in curiosity.

He came closer, his quick reptilian eyes taking in with evident interest every feature of their bodily appearance. Intuitively the three knew that one of them was to be chosen for a first investigation by the Martian scientists, and that that one would have not even the slender hope of escape open to the other two. A strange lottery of life and death!

andall saw the creature's gaze turn from one to another of them, and then heard the hiss of his voice as he pointed a taloned paw toward Milton. Instantly two of the guards had seized Milton and had jerked him out from the wall, the other guards holding back Randall and Lanier with threatening tubes. It was upon Milton that the fatal choice had fallen!

Randall and Lanier made together a half-movement forward, but Milton, a tense message in his eyes, forced them back. The guards who held the physicist led him, at the direction of the Martian scientist, toward a great upright frame at the room's far end, upon which were clustered a score of dial-indicators. From these flexible cords led; and now the scientists began attaching these by clips to various spots on Milton's body. Some mechanical examination of his bodily characteris[15]tics were apparently to be made. Milton shot suddenly a glance at the two by the wall, and his head nodded in an almost imperceptible signal. The muscles of Lanier and Randall tensed.

Then abruptly Milton seemed to go mad. He shouted aloud in a terrible voice, and at the same moment tore from him the cords just attached, his fists striking out then at the amazed Martians around him. As they leaped back from that sudden explosion of activity and sound on Milton's part the guards before Randall and Lanier whirled instinctively for an instant toward it. And in that instant the two had leaped.

t was upward they leaped, with all the force of their earthly muscles, toward the big window-opening a half-dozen feet in the wall above them. Like released steel springs they sat up, and Randall heard the thump of their feet as they struck the opening's sill, heard wild cries suddenly coming from beneath them, as the guards turned back toward them. Crimson rays clove up like light toward them, but the instant's surprise had been enough, and in it they had leaped on and through the opening, into the outside night!

As they shot downward and struck the metal paving outside, Randall heard a wild babble of cries from inside. A moment he and Lanier gazed frenziedly around them, then were running with great leaps along the base of the building from which they had just escaped.

In the darkness of night the Martian city stretched away to their right, its massive dark cone-structures outlined by points of glowing ruddy light here and there upon them. Beside the city's metal streets were illuminated by the brilliant field of stars overhead and by the soft light of the two moons, one much larger than the other, that moved among those stars.

Along the street crocodilian Martians were coming and going still, though in small numbers, there being but few in sight in the dim-lit street's length. Lanier pointed ahead as they leaped onward.

"Straight onward, Randall!" he jerked. "There seem fewer of the Martians this way!"

"But the great cone of the matter-station is the other way!" Randall exclaimed.

"We can't risk making for it now!" cried the other. "We've got to keep clear of them until the alarm is over. Hear them now?"

For even as they leaped forward a rising clamor of hissing cries and rush of feet was coming from behind as scores of Martians poured out into the darkness from the great cone-building. The two fugitives had passed by then from the shadow of the mighty structure, and as they ran along the broad metal street toward the shadow of the next cone, through the light of the moons above, they heard higher cries and then glimpsed narrow shafts of crimson force cleaving the night around them.

andall, as the deadly rays drove past him, heard the low detonating sound made by their destruction of the air in their path, and the inrush of new air. But in the misty and uncertain moonlight the rays could not be loosed accurately, and before they could be swept sidewise to annihilate the two fleeing men they had gained, with a last great leap, the shadow of the next building.

On they ran, the clatter of the Martian pursuit growing more noisy behind them. Randall heard Lanier gasping with each great leap, and felt himself at every breath a knife of pain stabbing through his lungs, the rarified atmosphere of the red planet taking its toll. Again from the darkness behind them the crimson rays clove, but this time were wide of their mark.

With every moment the clamor of pursuit seemed growing louder, the alarm spreading out over the Martian city and arousing it. As they raced[16] past cone after cone, Randall knew even the increased power of their muscles could not long aid them against the exhaustion which the thin air was imposing on them. His thoughts spun for a moment to Milton, in the laboratory behind, and then back to their own desperate plight.

Abruptly shapes loomed in the misty light before them! A group of three great Martians, reptilian shapes that had been coming toward them and had stopped for an instant in amazement at sight of the running pair. There was no time to halt themselves, to evade the three, and with a mutual instinct Lanier and Randall seized together the last expedient open to them. They ran straight forward toward the astounded three, and when a half-score feet from them, leaped with all their force upward and toward them, their tensed bodies flying through the air with feet outstretched before them.

Then they had struck the group of three with feet-foremost, and with the impetus of that great leap had knocked them sprawling to this side and that, while with a supreme effort the two kept their balance and leaped on. The cries of the three added to the din behind them as they threw themselves forward.

hey flung themselves past a last cone building to halt for an instant in utter amazement despite the nearing pursuit. Before them were no more streets and structures, but a huge smooth-flowing waterway! It gleamed in the moonlight and lay at right angles across their path, seeming to flow along the Martian city's edge.

"A canal!" cried Lanier. "It's one of the canals that meet at this city and flow around it! We're trapped—we've reached the city's edge!"

"Not yet!" Randall gasped. "Look!"

As he pointed to the left Lanier shot a glance there; and then both of them were running in that direction, along the smooth metal paving that bordered the mighty canal. They came to what Randall had seen, a mighty metal arch that soared out over the waterway to its opposite side. A bridge!

They were on it, were racing up the smooth incline of it. Randall glanced back as they reached the arch's summit. From that height the city stretched far away behind them, a lace of crimson lights in the night. He glimpsed the gleam of the giant waterway that encircled the city completely, one that was fed by other canals from far away that emptied into it, the great city's vital water-supply brought thus from this world's melting polar snows.

There were moving lights behind now, too, pouring out onto the metal paving by the waterway, moving to and fro as though in confusion, with a babel of hissing cries. It was not until Randall and Lanier were running down the descending incline of the great arched bridge, though, that the lights and shouts of their pursuers began to move up on that bridge after them.

unning off the bridge's smooth way, the two found themselves stumbling on through the darkness over more metal paving, and then over soft ground. There were no lights or buildings or sounds of any sort on this farther side of the great waterway. A tall dark wall seemed suddenly to loom up out of the darkness some distance ahead of the two.

"The crimson jungle!" Randall cried. "The jungles we glimpsed from the city! It's a chance to hide!"

They raced toward the protecting blackness of that wall of vegetation. They reached it, flung themselves inside, just as the pursuing Martians, a mass of running crocodilian shapes and of great racing centipede-machines, swept up over the bridge's arch behind. A moment the two halted in the thick vegetation's shelter, gasping for breath, then were moving forward through the jungle's denser darkness.

Thick about them and far above them towered the masses of strange trees[17] and plant life through which they made their way. Randall could see but dimly the nature of these plant-forms, but could make out that they were grotesque and unearthly in appearance, all leafless, and with masses of thin tendrils branching from them instead of leaves. He realized that it was only beside the arid planet's great canals that this profusion of plant life had sufficient moisture for existence, and that it was the broad bands of jungle bordering the canals that had made the latter visible to earth's astronomers.

anier and he halted for a moment to listen. The thick jungle about them seemed quite silent. But from behind there came through it a vague tumult of hissing calls; and then, as they glimpsed red flashes far behind, they heard the crashing of great masses of the leafless trees.

"The rays!" whispered Lanier. "They're beating through the jungle with them and the centipede-machines after us!"

They paused no more, but pushed on through the thick growths with renewed urgency. Now and then, as they passed through small clearings, Randall glimpsed overhead the fast-moving nearer moon and slower sailing farther moon of Mars, moving across the steady stars. In some of these clearings they saw, too, strange great openings burrowed in the ground as though by some strange animal.

The crashing clamor of the Martians beating the jungle behind was coming close, ever closer, and as they came to still another misty-lit clearing, Lanier paused, with face white and tense.

"They're closing in on us!" he said. "They're hunting us down by beating the jungle with those centipede-machines, and even if we escape them we're getting farther from the city and the matter-station each moment!"

Randall's eyes roved desperately around the clearing; and then, as they fell on a group of the great burrowed openings that seemed present everywhere about them, he uttered an exclamation.

"These holes! We can hide in one until they've passed over us, and then steal back to the city!"

Lanier's eyes lit. "It's a chance!"

hey sprang toward the openings. They were each of some four feet diameter, extending indefinitely downward as though the mouths of tunnels. In a moment Randall was lowering himself into one, Lanier after him. The tunnel in which they were, they found, curved to one side a few feet below the surface. They crawled down this curve until they were out of sight of the opening above. They crouched silent, then, listening.

There came down to them the dull, distant clamor of the centipede-machines crashing through the jungle, cutting a way with rays, their clamor growing ever louder. Then Randall, who was lowest in the tunnel, turned suddenly as there came to him a strange rustling sound from beneath him. It was as though some crawling or creeping thing was moving in the tunnel below them!

He grasped the arm of Lanier, beside and a little above him, to warn him, but the words he was about to whisper never were uttered. For at this moment a big shapeless living thing seemed to flash up toward them through the darkness from beneath, cold ropelike tentacles gripped both tightly; and then in an instant they were being dragged irresistibly down into the lightless tunnel's depths!

s they were pulled swiftly downward into the tunnel by the tentacles that grasped them an involuntary cry of horror came from Randall and Lanier alike. They twisted frantically in the cold grip that held them, but found it of the quality of steel. And as Randall twisted in it to strike frantically down through the darkness at whatever thing of horror held them, his clenched fist met but the cold[18] smooth skin of some big, soft-bodied creature!

Down—down—remorselessly they were being drawn farther into the black depths of the tunnel by the great thing crawling down below them. Again and again the two twisted and struck, but could not shake its hold. In sheer exhaustion they ceased to struggle, dragged helplessly farther down.

Was it minutes or hours, Randall wondered afterward, of that horrible progress downward, that passed before they glimpsed light beneath? A feeble glow, hardly discernible, it was, and as they went lower still he saw that it was caused by the tunnel passing through a strata of radio-active rock that gave off the faint light. In that light they glimpsed for the first time the horror dragging them downward.

It was a huge worm creature! A thing like a giant angleworm, three feet or more in thickness and thrice that in length, its great body soft and cold and worm-like. From the end nearest them projected two long tentacles with which it had gripped the two men and was dragging them down the tunnel after it! Randall glimpsed a mouth-aperture in the tentacled end of the worm body also, and two scarlike marks above it, placed like eyes, although eyes the monstrous thing had not.

ut a moment they glimpsed it and then were in darkness again as the tunnel passed through the radio-active strata and lower. The horror of that moment's glimpse, though, made them strike out in blind repulsion, but relentlessly the creature dragged them after it.

"God!" It was Lanier's panting cry as they were dragged on. "This worm monster—we're hundreds of feet below the surface!"

Randall sought to reply, but his voice choked. The air about them was close and damp, with an overpowering earthy smell. He felt consciousness leaving him.

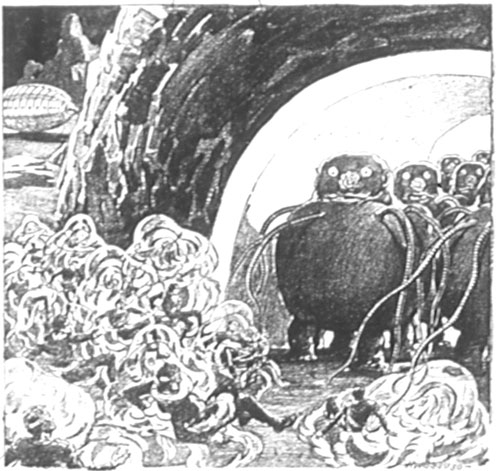

A gleam of soft light—they were passing more radio-active patches. He felt the wild convulsive struggles of Lanier against the thing; and then suddenly the tunnel ended, debouched into a far-stretching, low-ceilinged cavity. It was feebly illuminated by radio-active patches here and there in walls and ceiling, and as the monster that held them halted on entering the cavity, Randall and Lanier lay in its grip and stared across the weird place with intensified horror.

For it was swarming with countless worm monsters! All were like the one who held them, thick long worm bodies with projecting tentacles and with black eyeless faces. They were crawling to and fro in this cavern far beneath the surface, swarming in hordes around and over each other, pouring in and out of the awful place from countless tunnels that led upward and downward from it!

world of worm monsters, beneath the surface of the Martian jungles! As Randall stared across that swarming, dim-lit cave of horror, physically sick at sight of it, he remembered the countless tunnel openings they had glimpsed in their flight through the jungle, and remembered the remark of the Martian who had first guided them across the city, that in the jungles were living things, of a sort. These were the things, worm monsters whose unthinkable networks of tunnels and burrows formed beneath the surface a veritable worm world!

"Randall!" It was Lanier's thick exclamation. "Randall—those scar-marks on their—faces—you see—?"

"See?"

"Those marks! These creatures had eyes once but must have been forced down here by the Martians. These may once have been—ages ago—human!"

At that thought Randall felt horror overcoming his senses. He was aware that the great worm monster holding them was dragging them forward through the cavern, that others of the[19] swarms there were crowding around them, feeling them blindly with their tentacles, helping to drag them forward.

Half-carried and half-dragged they went, scores of tentacles now holding them, great worm shapes crawling forward on all sides of them and accompanying them along the cavern's length. He glimpsed worm monsters here and there emerging from the upward tunnels with masses of strange plant stuff in their grasp that others blindly devoured. His senses reeled from the suffocating air, the great cavity being but a half-score feet in height, burrowed from the damp earth by these numberless things.

he faint, strange light of the radio-active patches showed him that they were approaching the cavern's end. Tunnels opened from its end as from all its walls and floor, and into one Randall was dragged by the creatures, one before and one behind, grasping him, and Lanier being brought behind him in the same way. In the close tunnel the heavy air was deadly, and he was but partly conscious when again, after moments of crawling along it, he felt himself dragged out into another cavern.

This earth-walled cavity, though, seemed to extend farther than the first, though of the same height as the first and with a few radio-active illuminating patches. In it seethed and swarmed literally hundreds on hundreds of the worm monsters, a sea of great crawling bodies. Randall and Lanier saw that they were being carried and dragged now toward the farther end of this larger cavity.

As they approached it, pushing through the swarming creatures who felt them with inquisitive tentacles as their captors took them forward, the two men saw that a great shape was looming up in the faint light at the cave's far end. In moments they were close enough to discern its nature, and a horror and awe filled them at sight of it more intense than they had yet felt.

For the looming shape was a huge earthen image or statue of a worm! It was shaped with a childish crudeness from the solid earth, a giant earthen worm shape whose body looped across the cave's end, and whose tentacled head or front end was reared upward to the cavity's roof. Before this awful earthen shape was a section of the cave's floor higher than the rest, and on it a great crudely shaped rectangular earthen block.

"Lanier—that shape!" whispered Randall in his horror. "That earthen image, made by these creatures—it's the worm god they've made for themselves!"

"A worm god!" Lanier repeated, staring toward it as they were dragged nearer. "Then that block...."

"Its altar!" Randall exclaimed. "These things have some dim spark of intelligence or memory! They're brought us here to—"

efore he could finish, the clutching tentacles of the worm monsters about them had dragged them up onto the raised floor beside the block, beneath the looming earthen worm shape. There they glimpsed for the first time in the faint light another who stood there held tightly by the tentacles of two worm monsters. It was a Martian!

The big crocodilian shape was apparently a prisoner like themselves, captured and brought down from above. His reptilian eyes surveyed Lanier and Randall quickly as they were dragged up and held beside him, but he took no other interest. To the two men, at the moment, it seemed that his great crocodilian shape was human, almost, so much more man-like was it than the grotesque worm monsters before them.

With a half-dozen of the creatures holding the two men and the Martian tightly, another great worm monster crawled to the edge of the raised earth floor in front of the giant worm god's image, and then reared up the first[20] third of his thick body into the air. By then the great, faint-lit cavity stretching before them was filled with countless numbers of the monsters, pouring into it from all the tunnels that opened into it from above and below, packing it thick with their grotesque bodies as far as the eye could reach in the dim light.

They were seething and crawling in that great mass; but as the worm monster on the elevation upreared, all in the cavity seemed suddenly to quiet. Then the upreared eyeless thing began to move his long tentacles. Very slowly at first he waved them back and forth, and slowly the masses of monsters in the cavity, all turned by some sense toward him, did likewise, the cavity becoming a forest of upraised tentacles waving rhythmically back and forth in unison with those of the leader.

ack and forth—back and forth—Randall felt caught in some torturing nightmare as he watched the countless tentacle-feelers waving thus from one side to the other. It was a ceremony, he knew—some strange rite springing perhaps from dim memory alone, that these worm monsters carried out thus before the looming shape of their worm god. Only the six that held the three captives never relaxed their grip.

Still on and on went the strange and senseless rite. By then the close, damp air of that cavity far beneath Mars' surface was sinking Randall and Lanier deeper into a half-consciousness. The Martian beside them never moved or spoke. The upstretched tentacles of the leader and of the great worm horde before him never ceased swaying rhythmically from side to side.

Randall, half-hypnotized by those swaying tentacles and but semi-conscious by then, could only estimate afterward how long that grotesque rite went on. Hours it must have endured, he knew, hours in which each opening of his eyes revealed only the dimly-illuminated cavern, the worm monsters that filled it, the forest of tentacles waving in unison. It was only toward the end of those hours that he noticed vaguely that the tentacles were waving faster and faster.

And as the tentacles of leader and worm horde waved alike ever more swiftly an atmosphere of growing excitement and expectation seemed to hold the horde. At last the upstretched feelers were whipping back and forth almost too swiftly for the eye to follow. Then abruptly the worm leader ceased the motion himself, and while the horde before him continued it, turned and crawled to the three captives.

In an instant, as though in answer to a second command, the two worm monsters who held the Martian dragged him forward toward the great earthen block before the worm god's image. Two others of the creatures came from the side, and the four swiftly stretched the Martian flat on the block's top, each of the four grasping with their tentacles one of his four taloned limbs. They seemed to hesitate then, the worm leader beside them, the tentacles of the horde waving swiftly still.

Abruptly the tentacles of the leader flashed up as though in a signal. There was a dull ripping sound, and in that moment Randall and Lanier saw the Martian on the block torn literally limb from limb by the four great worm monsters who had held his four limbs!

The tentacles of the horde waved suddenly with increased, excited swiftness at that. Randall shrank in horror.

"They've brought us here for that!" he cried. "To sacrifice us on that altar that way to their worm god!"

But Lanier too had cried out, appalled, as he saw that awful sacrifice, and both strained madly against the grip of the worm creatures. Their struggles were in vain, and then in answer to another unspoken command the two monsters that held Randall were[21] dragging him also to the earthen altar!

He felt himself gripped by the four great creatures around the block, felt as he struggled with his last strength that he was being stretched out on the block, each of the four at one of its corners grasping one of his limbs. He heard Lanier's mad cries as though from a great distance, glimpsed as he was held thus on his back the great shape of the earthen worm god reared over him, and then glimpsed the leader of the monsters rearing beside him.

he dull sound of the swift-waving tentacles of the horde came to him, there was a tense moment of agony of waiting, and then the tentacles of the leader flashed up in the signal!

But at the same moment Randall felt his limbs released by the four monsters that had held them! There seemed sudden wild confusion in the great cave. The strange rite broke off; the horde of worm monsters crawled frantically this way and that in it. Randall slipped off the block; staggered to his feet.

The worm monsters in the cave were swarming toward the downward tunnel openings! The two captives forgotten, the creatures were pouring in crawling, fighting swarms toward those openings. And then, as Randall and Lanier stared stupefied, there came a red flash from one of the upward tunnels and a brilliant crimson ray stabbed down and mowed a path of annihilation in the cave's earthen side!

The two heard great thumping sounds from above, saw the tunnels leading from above becoming suddenly many times greater in size as red rays flashed down along them to gouge the tunnel's walls. Then down from those enlarged tunnels there were bursting long shining shapes, great centipede-machines crawling down the tunnels which their rays made larger before them! And as the centipede-machines burst down into the cavern their crimson rays stabbed right and left to cut paths of annihilation among the worms.

"The Martians!" Lanier cried. "They didn't find us above—they knew we must have been taken by these things—and they've come down after us!"

ack, Lanier!" Randall shouted. "Quick, before they see us, behind this—"

As he spoke he was jerking Lanier with him behind the looming earthen statue of the great worm god. Crouched there between the statue and the cave's wall they were hidden precariously from the view of those in the cavern. And now that cavern had become a scene of horror unthinkable as the centipede-machines pouring down into it blasted the frantically crawling worm monsters with their rays.

The worm monsters attempted no resistance, but sought only to escape into their downward tunnels, and in moments those not caught by the rays had vanished in the openings. But the centipede-machines, after racing swiftly around the cavity, were following them, were going down into those downward tunnels also, their rays blasting down ahead of each to make the tunnel large enough for them to follow.

In a moment all but one had vanished down into the openings, the remaining one having its front or head jammed in one of the openings from the failure of its operator to blast a large enough opening before him. As Lanier and Randall watched tensely they saw the machine's control room door open and a Martian descend. He inspected the tunnel opening in which his vehicle was jammed, then with a hand ray-tube began to disintegrate the earth around that opening to free his machine.

Randall clutched his companion's arm. "That machine!" he whispered. "If we could capture it, it would give us a chance to get back to the city—to Milton and the matter-transmitter!"

Lanier started, then nodded swiftly. "We'll chance it," he whispered. "For our twenty-four hours here must be almost up."[22]

hey hesitated a moment, then crept forward from behind the great earthen statue. The Martian had his back to them, his attention on the freeing of his mechanism. Across the dim-lit cavern they crept softly, and were within a dozen feet of the Martian when some sound made him wheel quickly to confront them with the deadly tube. But even as he whirled the two had leaped.

The force of their leap sent them flying through that dozen feet of space to strike the Martian at the moment his tube levelled. One hissing call he uttered as they struck him, and then with all his strength Lanier had grasped the crocodilian body and bent it backward. Something in it snapped, and the Martian collapsed limply. The two looked wildly around.

Nothing showed that the Martian's call had been heard, and after a moment's glance that showed the head of the centipede machine already freed, they were clambering up into its control room, closing the door. Randall seized the knob with which he had seen the machines operated. As he pulled it toward him the machine moved across the tunnel opening and raced smoothly over the cavern's floor. As he turned the knob the machine turned swiftly in the same direction.

He headed the long mechanism toward one of the upward-curving tunnels which the Martians had blasted larger in descending. They were almost to it when there flashed up into the cavity from one of the downward tunnel openings a centipede-machine, and then another, and another. The Martians in their transparent-windowed control rooms took in at a glance the dead crocodilian on the floor, and then the three great machines were darting toward that of Randall and Lanier.

"The Martian we killed!" Randall cried. "They heard his call and are coming after us!"

"Turn to the wall!" Lanier shouted to him. "I have the rays—"

t that moment there was a clicking beside Randall and he glimpsed Lanier pulling forth two small grips he had found, then saw that two crimson rays were stabbing from tubes in their machine's front toward the others even as their own rays darted back. The beams that had been loosed toward them grazed past them as Randall whirled their machine to the wall, and he saw one of the three attacking mechanisms vanish as Lanier's beams struck it.

Around—back—with instinctive, lightninglike motions he whirled their centipede-machine in the great dim-lit cave as the two remaining ones leapt again to the attack. Their rays shot right and left to catch the two men's vehicle in a trap of death, and as Randall swung their own mechanism straight ahead he glimpsed at the cavern's far end the great earthen worm god still upreared.

On either side of them the red beams burned as they leapt forward, but as though running a gauntlet of death Randall kept the machine racing forward in the succeeding second until the two others loomed on either side of it. Then Lanier's beams were driving in turn to right and left of them and the two vanished as though by magic as they were struck.

"Up to the surface!" Lanier cried, his eyes on the glowing dial of his wrist-watch. "We've been held hours here—we've but a half-hour or more before earth midnight!"

andall sent their machine racing again toward one of the upward tunnels, and as the long mechanism began to climb smoothly up the darkness he heard Lanier agonizing beside him.

"God, if we have only enough time to get to that matter-transmitter before the Martians start flashing to earth through it!"

"But Milton?" Randall cried. "We don't know whether he's alive or dead! We can't leave him!"[23]

"We must!" said Lanier solemnly. "Our duty's to the earth now, man, to the world that we alone can save from the Martian invasion and conquest! At the hour of twelve Nelson will have the matter-receiver turned on and at that hour the Martian will start flashing to earth—unless we prevent!"

Suddenly Randall grasped the knob in his hands more tightly as light showed above them. They had been climbing upward through the enlarged tunnel at their machine's highest speed, and now as the tunnel curved the light grew stronger. Suddenly they were emerging into the thin sunlight of the Martian day.

In the crimson jungle about them were many Martians, milling excitedly to and fro, and other centipede-machines that were blasting their way down through tunnels to the worm world beneath.

Randall and Lanier, breathless, crouched low in the transparent-windowed control room as they sent their mechanism racing through this scene of swarming activity. Both gasped as one of the centipede-machines clashed against their own in passing, its Martian driver turning to stare after them. But there came no alarm, and in a moment they had passed out of the swarm of Martians and machines and were heading through the jungle in the direction of the city.

hrough the weird red vegetation their mechanism raced with them, Randall holding it at its highest speed, and in minutes they came out of the jungle and were racing over the clear space between it and the great canal. Beyond that canal loomed into the thin sunlight the clustering cones of the mighty Martian city, two towering above all the others—the cone of the Martian Master and the other cone in which was the matter-transmitter and receiver.

It was toward the latter that Lanier pointed. "Head straight toward that cone, Randall—we've but minutes left!"

They were racing now up over the great arch of the canal's metal bridge, and then scuttling smoothly off it and along the broad metal street through which they had fled in darkness hours before. In it Martians and centipede-machines were coming and going in great numbers, but none noticed the human forms of the two crouched low in their mechanism's control room.

They were rushing then toward the looming cone of the Martian Master. As they flashed past it Randall saw Lanier's face working, knew the desire that tore at him even as at himself to burst inside and ascertain whether or not Milton still lived in the laboratories from which they had fled. But they were past it, faces white and grim, were rushing on through the Martian city at reckless speed toward the other mighty cone.

t seemed that all in the great city were heading toward the same goal, streams of crocodilian Martians and masses of shining centipede-machines filling the streets as they moved toward it. As they came closer to the mighty structure, hearts pounding, they saw that around it surged a mighty mass of Martians and machines. The hordes waiting to be released through the matter-transmitter inside upon the unsuspecting earth!

"Try to get the machine inside!" Lanier whispered tensely. "If we can smash that transmitter yet...."

Randall nodded grimly. "Keep ready at the ray-tubes," he told the other.

As unobtrusively as possible he sent their long mechanism worming forward through the vast throng of machines and Martians, toward the great cone's door. Crouching low, the hands of their watches closing fast toward the twelfth figure, they edged forward in the long machine. At last they were moving through the mighty door, into the cone's interior.

They moved slowly on through the mass of machines and crocodile forms[24] inside, then halted. For at the great crowd's center was a clear circle hundreds of feet across, and as Randall gazed across it his heart seemed to leap once and then stop.

At the center of that clear circle rose the two cubical metal chambers of the matter-transmitter and receiver. The transmitting chamber, they saw, was flooded with humming force, with white light pouring from its inner walls. It was already in operation, and the masses of Martians in the great cone were only waiting for the moment to sound when the receiver on earth would be operating also. Then they would pour into the chamber to be flashed in masses across the gulf to earth! The eyes of all in the cone seemed turned toward an erect dial-mechanism beside the chambers which was clocklike in appearance, and that would mark the moment when the first Martian could enter the transmitting-chamber and flash out.

little distance from the two metal chambers stood a low dais on which there sat the hideous triple-bodied form of the Martian Master. Around him were the massed members of his council, waiting like him for the start of their age-planned invasion of earth. And beside the dais was a figure between two crocodilian guards at sight of whom Randall forgot all else.

"Milton! My God, Lanier, it's Milton!"

"Milton! They've brought him here to torture or kill him if they find he's lied about the moment they could flash to earth!"

Milton! And at sight of him something snapped in Randall's brain.

With a single motion of the knob he sent their centipede-machine crashing out into the clear circle at the mighty cone's center. A wild uproar of hissing cries broke from all the thousands in it as he sent the mechanism whirling toward the dais of the Martian Master. He saw the crocodilian forms there scattering blindly before him, and then as his rays drove out and spun and stabbed in mad figures of crimson death through the astounded Martian masses he saw Milton looking up toward them, crying out crazily to them as his two guards loosed him for the moment.

A high call from the Martian Master ripped across the hall and was answered by a shattering roar of hissing voices as Martians and machines surged madly toward them. Randall and Lanier in a single leap were out of the centipede-machine, and in an instant had half-dragged Milton with them in a great leap up to the edge of the humming transmitting chamber.

ilton was shouting hoarsely to them over the wild uproar. To enter that transmitting chamber before the destined moment was annihilation, to be flashed out with no receiver on earth awaiting them. They turned, struck with all their strength at the first Martians rushing up to them. No rays flashed, for a ray loosed would destroy the chamber behind them that was the one gate for the Martians to the world they would invade. But as the Martian Master's high call hissed again all the countless crocodilian forms in the great cone were rushing toward them.

Braced at the very edge of the humming, light-filled chamber, Randall and Lanier and Milton struck madly at the Martians surging up toward them. Randall seemed in a dream. A score of taloned paws clutched him from beneath; scaled forms collapsed under his insane blows.

The whole vast cone and surging reptilian hordes seemed spinning at increasing speed around him. As his clenched fists flashed with waning strength he glimpsed crocodilian forms swarming up on either side of them, glimpsed Lanier down, talons reaching toward him, Milton fighting over him like a madman. Another moment would see it ended—reptilian arms reaching in scores to drag him down—Milton[25] jerking Lanier half to his feet. The Martian Master's call sounded—and then came a great clanging sound at which the Martian hordes seemed to freeze for an instant motionless, at which Milton's voice reached him in a supreme cry.

"Randall—the transmitter!"

For in that instant Milton was leaping back with Lanier, and as Randall with his last strength threw himself backward with them into the humming transmitting-chamber's brilliant light, he heard a last frenzied roar of hissing cries from the Martian hordes about them. Then as the brilliant light and force from the chamber's walls smote them, Randall felt himself hurled into blackness inconceivable, that smashed like a descending curtain across his brain.

The curtain of blackness lifted for a moment. He was lying with Milton and Lanier in another chamber whose force beat upon them. He saw a yellow-lit room instead of the great cone—saw the tense, anxious face of Nelson at the switch beside them. He strove to move, made to Nelson a gesture with his arm that seemed to drain all strength and life from him; and then, as in answer to it Nelson drove up the switch and turned off the force of the matter-receiver in which they lay, the black curtain descended on Randall's brain once more.

wo hours later it was when Milton and Randall and Lanier and Nelson turned to the laboratory's door. They paused to glance behind them. Of the great matter-transmitter and receiver, of the apparatus that had crowded the laboratory, there remained now but wreckage.

For that had been their first thought, their first task, when the astounded Nelson had brought the three back to consciousness and had heard their amazing tale. They had wrecked so completely the matter-station and its actuating apparatus that none could ever have guessed what a mechanism of wonder the laboratory a short time before had held.

The cubical chambers had been smashed beyond all recognition, the dynamos were masses of split metal and fused wiring, the batteries of tubes were shattered, the condensers and transformers and wiring demolished. And it had only been when the last written plans and blue-prints of the mechanism had been burned that Milton and Randall and Lanier had stopped to allow their exhausted bodies a moment of rest.

ow as they paused at the laboratory's door, Lanier reached and swung it open. Together, silent, they gazed out.

It all seemed to Randall exactly as upon the night before. The shadowy masses in the darkness, the heaving, dim-lit sea stretching far away before them, the curtain of summer stars stretched across the heavens. And, sinking westward amid those stars, the red spark of Mars toward which as though toward a magnet all their eyes had turned.

Milton was speaking. "Up there it has shone for centuries—ages—a crimson spot of light. And up there the Martians have been watching, watching—until at last we opened to them the gate."

Randall's hand was on his shoulder. "But we closed that gate, too, in the end."

Milton nodded slowly. "We—or the fate that rules our worlds. But the gate is closed, and God grant, shall never again be opened by any on this world."

"God grant it," the other echoed.

And they were all gazing still toward the thing. Gazing up toward the crimson spot of light that burned there among the stars, toward the planet that shone red, menacing, terrible, but whose menace and whose terror had been thrust back even as they had crouched to spring at last upon the earth.

Presently there was not one Robot, but three!

Presently there was not one Robot, but three!