BIRDS

A MONTHLY SERIAL

ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY

DESIGNED TO PROMOTE

KNOWLEDGE OF BIRD-LIFE

VOLUME II.

CHICAGO

Nature Study Publishing Company

copyright, 1897

by

Nature Study Publishing Co.

chicago.

INTRODUCTION.

This is the second volume of a series intended to present, in accurate colored portraiture, and in popular and juvenile biographical text, a very considerable portion of the common birds of North America, and many of the more interesting and attractive specimens of other countries, in many respects superior to all other publications which have attempted the representation of birds, and at infinitely less expense. The appreciative reception by the public of Vol. I deserves our grateful acknowledgement. Appearing in monthly parts, it has been read and admired by thousands of people, who, through the life-like pictures presented, have made the acquaintance of many birds, and have since become enthusiastic observers of them. It has been introduced into the public schools, and is now in use as a text book by hundreds of teachers, who have expressed enthusiastic approval of the work and of its general extension. The faithfulness to nature of the pictures, in color and pose, have been commended by such ornithologists and authors as Dr. Elliott Coues, Mr. John Burroughs, Mr. J. W. Allen, editor of The Auk, Mr. Frank M. Chapman, Mr. J. W. Baskett, and others.

The general text of Birds—the biographies—has been conscientiously prepared from the best authorities by a careful observer of the feather-growing denizens of the field, the forest, and the shore, while the juvenile autobiographies have received the approval of the highest ornithological authority.

The publishers take pleasure in the announcement that the general excellence of Birds will be maintained in subsequent volumes. The subjects selected for the third and fourth volumes—many of them—will be of the rare beauty in which the great Audubon, the limner par excellence of birds, would have found “the joy of imitation.”

Nature Study Publishing Company.

BIRDS.

Illustrated by COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY.

BIRD SONG.

T SHOULD not be overlooked by the young observer that if he would learn to recognize at once any particular bird, he should make himself acquainted with the song and call notes of every bird around him. The identification, however, of the many feathered creatures with which we meet in our rambles has heretofore required so much patience, that, though a delight to the enthusiast, few have time to acquire any great intimacy with them. To get this acquaintance with the birds, the observer has need to be prepared to explore perilous places, to climb lofty trees, and to meet with frequent mishaps. To be sure if every veritable secret of their habits is to be pried into, this pursuit will continue to be plied as patiently as it has ever been. The opportunity, however, to secure a satisfactory knowledge of bird song and bird life by a most delightful method has at last come to every one.

A gentleman who has taken a great interest in Birds from the appearance of the first number, but whose acquaintance with living birds is quite limited, visited one of our parks a few days ago, taking with him the latest number of the magazine. His object, he said, was to find there as many of the living forms of the specimens represented as he could. “Seating myself amidst a small grove of trees, what was my delight at seeing a Red Wing alight on a telegraph wire stretching across the park. Examining the picture in Birds I was somewhat disappointed to find that the live specimen was not so brilliantly marked as in the picture. Presently, however, another Blackbird alighted near, who seemed to be the veritable presentment of the photograph. Then it occured to me that I had seen the Red Wing before, without knowing its name. It kept repeating a rich, juicy note, oncher-la-ree-e! its tail tetering at quick intervals. A few days later I observed a large number of Red Wings near the Hyde Park water works, in the vicinity of which, among the trees and in the marshes, I also saw many other birds unknown to me. With Birds in my hands, I identified the Robin, who ran along the ground quite close to me, anon summoning with his beak the incautious angle worm to the surface. The Jays were noisy and numerous, and I observed many new traits in the Wood Thrush, so like the Robin that I was at first in some doubt about it. I heard very few birds sing that day, most of them being busy in search of food for their young.”

[continued on page 17.]

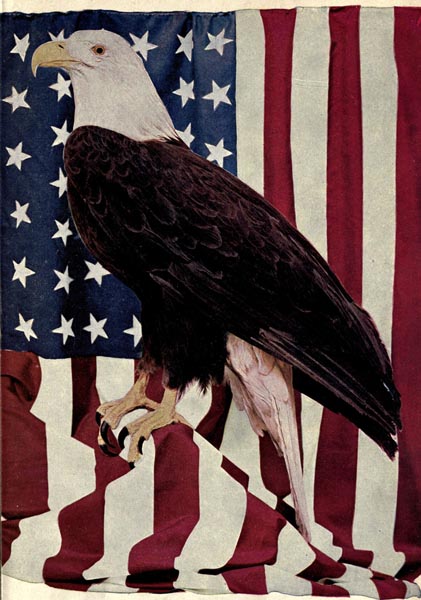

THE BALD-HEADED EAGLE.

Dear Boys and Girls:

I had hoped to show you the picture of the eagle that went through the war with the soldiers. They called him “Old Abe.” You will find on page 35 a long story written about him. Ask some one to read it to you.

I could not get “Old Abe,” or you should now be looking at his picture. He is at present in Wisconsin, and his owner would not allow him to be taken from home.

I did the next best thing, and found one that was very much like him. They are as near alike as two children of a family. Old Abe’s feathers are not quite so smooth, though. Do you wonder, after having been through the war? He is a veteran, isn’t he?

The picture is that of a Bald-headed Eagle. He is known, also, by other names, such as White-headed Eagle, Bird of Washington, Sea Eagle.

You can easily see by the picture that he is not bald-headed. The name White-headed would seem a better name. It is because at a distance his head and neck appear as though they were covered with a white skin.

He is called “Sea Eagle” because his food is mostly fish. He takes the fish that are thrown upon the shores by the waves, and sometimes he robs the Fish Hawk of his food.

This mighty bird usually places his large nest in some tall tree. He uses sticks three to five feet long, large pieces of sod, weeds, moss, and whatever he can find.

The nest is sometimes five or six feet through. Eagles use the same nest for years, adding to it each year.

Young eagles are queer looking birds. When hatched, they are covered with a soft down that looks like cotton.

Their parents feed them, and do not allow them to leave the nest until they are old enough to fly. When they are old enough, the mother bird pushes them out of the nest. She must be sure that they can fly, or she would not dare do this. Don’t you think so?

american bald eagle.

american bald eagle.From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences.

THE BALD-HEADED EAGLE.

HIS mighty bird of lofty flight is a native of the whole of North America, and may be seen haunting the greater portions of the sea coasts, as well as the mouths of large rivers. He is sometimes called the White-headed Eagle, the American Sea Eagle, the Bird of Washington, the Washington Eagle, and the Sea Eagle. On account of the snowy white of his head and neck, the name Bald Eagle has been applied to him more generally than any other.

Sea-faring men are partial to young Eagles as pets, there being a well established superstition among them that the ship that carries the “King of Birds” can never go down. The old Romans, in selecting the Eagle as an emblem for their imperial standard, showed this superstitious belief, regarding him as the favorite messenger of Jupiter, holding communion with heaven. The Orientals, too, believed that the feathers of the Eagle’s tail rendered their arrows invincible. The Indian mountain tribes east of Tennessee venerated the Eagle as their bird of war, and placed a high value on his feathers, which they used for headdresses and to decorate their pipes of peace.

The United States seems to have an abiding faith in the great bird, as our minted dollars show.

The nest of the Bald Eagle is usually placed upon the top of a giant tree, standing far up on the side of a mountain, among myriads of twining vines, or on the summit of a high inaccessible rock. The nest in the course of years, becomes of great size as the Eagle lays her eggs year after year in the same nest, and at each nesting season adds new material to the old nest. It is strongly and comfortably built with large sticks and branches, nearly flat, and bound together with twining vines. The spacious interior is lined with hair and moss, so minutely woven together as to exclude the wind. The female lays two eggs of a brownish red color, with many dots and spots, the long end of the egg tapering to a point. The parents are affectionate, attend to their young as long as they are helpless and unfledged, and will not forsake them even though the tree on which they rest be enveloped in flames. When the Eaglets are ready to fly, however, the parents push them from the perch and trust them to the high atmospheric currents. They turn them out, so to speak, to shift for themselves.

The Bald Eagle has an accommodating appetite, eating almost anything that has ever had life. He is fond of fish, without being a great fisher, preferring to rob the Fish-hawk of the fruits of his skillful labor. Sitting upon the side of a mountain his keen vision surveys the plain or valley, and detects a sheep, a young goat, a fat turkey or rooster, a pig, a rabbit or a large bird, and almost within an eye-twinkle he descends upon his victim. A mighty grasp, a twist of his talons, and the quarry is dead long before the Eagle lays it down for a repast. The impetuosity and skill with which he pursues, overtakes and robs the Fish-hawk, and the swiftness with which the Bald Eagle darts down upon and seizes the booty, which the Hawk has been compelled to let go, is not the least wonderful part of this striking performance.

The longevity of the Eagle is very great, from 80 to 160 years.

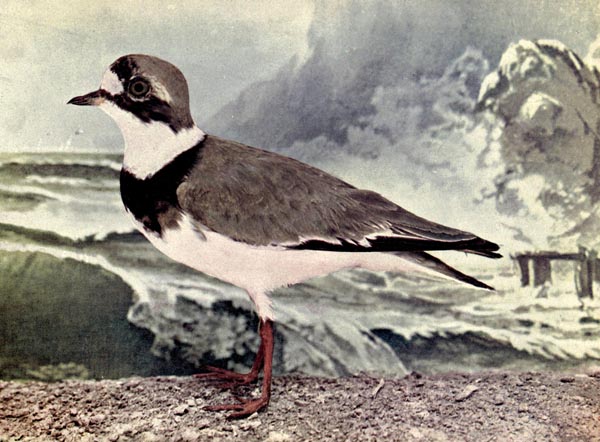

THE SEMI-PALMATED RING PLOVER.

N THEIR habits the Plovers are usually active; they run and fly with equal facility, and though they rarely attempt to swim, are not altogether unsuccessful in that particular.

The Semi-palmated Ring Plover utters a plaintive whistle, and during the nesting season can produce a few connected pleasing notes. The three or four pear-shaped, variagated eggs are deposited in a slight hollow in the ground, in which a few blades of grass are occasionally placed. Both parents assist in rearing the young. Worms, small quadrupeds, and insects constitute their food. Their flesh is regarded as a delicacy, and they are therefore objects of great attraction to the sportsman, although they often render themselves extremely troublesome by uttering their shrill cry and thus warning their feathered companions of the approach of danger. From this habit they have received the name of “tell-tales.” Dr. Livingstone said of the African species: “A most plaguey sort of public spirited individual follows you everywhere, flying overhead, and is most persevering in his attempts to give fair warning to all animals within hearing to flee from the approach of danger.”

The American Ring Plover nests as far north as Labrador, and is common on our shores from August to October, after which it migrates southward. Some are stationary in the southern states. It is often called the Ring Plover, and has been supposed to be identical with the European Ringed Plover.

It is one of the commonest of shore birds. It is found along the beaches and easily identified by the complete neck ring, white upon dark and dark upon light. Like the Sandpipers the Plovers dance along the shore in rhythm with the wavelets, leaving sharp half-webbed footprints on the wet sand. Though usually found along the seashore, Samuels says that on their arrival in spring, small flocks follow the courses of large rivers, like the Connecticut. He also found a single pair building on Muskeget, the famous haunt of Gulls, off the shore of Massachusetts. It has been found near Chicago, Illinois, in July.

ring plover.

ring plover.

THE RING PLOVER.

Plovers belong to a class of birds called Waders.

They spend the winters down south, and early in the spring begin their journey north. By the beginning of summer they are in the cold north, where they lay their eggs and hatch their young. Here they remain until about the month of August, when they begin to journey southward. It is on their way back that we see most of them.

While on their way north, they are in a hurry to reach their nesting places, so only stop here and there for food and rest.

Coming back with their families, we often see them in ploughed fields. Here they find insects and seeds to eat.

The Ring Plover is so called from the white ring around its neck.

These birds are not particular about their nests. They do not build comfortable nests as most birds do. They find a place that is sheltered from the north winds, and where the sun will reach them. Here they make a rude nest of the mosses lying around.

The eggs are somewhat pointed, and placed in the nest with the points toward the center. In this way the bird can more easily cover the eggs.

We find, among most birds, that after the nest is made, the mother bird thinks it her duty to hatch the young.

The father bird usually feeds her while she sits on the eggs. In some of the bird stories, you have read how the father and mother birds take turns in building the nest, sitting on the nest, and feeding the young.

Some father birds do all the work in building the nest, and take care of the birds when hatched.

Among plovers, the father bird usually hatches the young, and lets the wife do as she pleases.

After the young are hatched they help each other take care of them.

Plovers have long wings, and can fly very swiftly.

The distance between their summer and winter homes is sometimes very great.

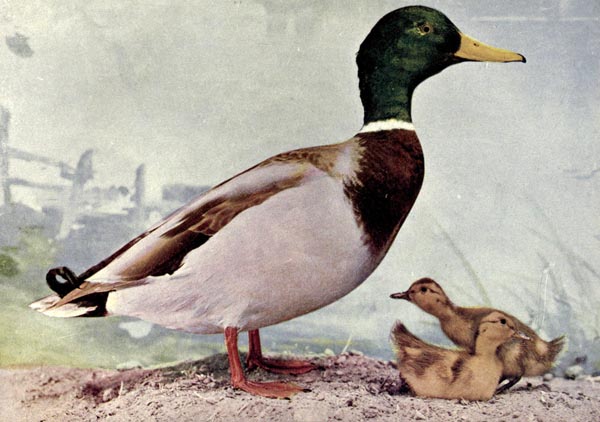

THE MALLARD DUCK.

We should probably think this the most beautiful of ducks, were the Wood Duck not around.

His rich glossy-green head and neck, snowy white collar, and curly feathers of the tail are surely marks of beauty.

But Mr. Mallard is not so richly dressed all of the year. Like a great many other birds, he changes his clothes after the holiday season is over. When he does this, you can hardly tell him from his mate who wears a sober dress all the year.

Most birds that change their plumage wear their bright, beautiful dress during the summer. Not so with Mr. Mallard. He wears his holiday clothes during the winter. In the summer he looks much like his mate.

Usually the Mallard family have six to ten eggs in their nest. They are of a pale greenish color—very much like the eggs of our tame ducks that we see about the barnyards.

Those who have studied birds say that our tame ducks are descendants of the Mallards.

If you were to hear the Mallard’s quack, you could not tell it from that of the domestic duck.

The Mallard usually makes her nest of grass, and lines it with down from her breast. You will almost always find it on the ground, near the water, and well sheltered by weeds and tall grasses.

It isn’t often you see a duck with so small a family. It must be that some of the ducklings are away picking up food.

Do you think they look like young chickens?

mallard duck.

mallard duck.From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences.

THE MALLARD DUCK.

HE Mallard Duck is generally distributed in North America, migrating south in winter to Panama, Cuba, and the Bahamas. In summer the full grown male resembles the female, being merely somewhat darker in color. The plumage is donned by degrees in early June, and in August the full rich winter dress is again resumed. The adult males in winter plumage vary chiefly in the extent and richness of the chestnut of the breast.

The Mallard is probably the best known of all our wild ducks, being very plentiful and remarkable on account of its size. Chiefly migrant, a few sometimes remain in the southern portion of Illinois, and a few pairs sometimes breed in the more secluded localities where they are free from disturbance. Its favorite resorts are margins of ponds and streams, pools and ditches. It is an easy walker, and can run with a good deal of speed, or dive if forced to do so, though it never dives for food. It feeds on seeds of grasses, fibrous roots of plants, worms, shell fish, and insects. In feeding in shallow water the bird keeps the hind part of its body erect, while it searches the muddy bottom with its bill. When alarmed and made to fly, it utters a loud quack, the cry of the female being the louder. “It feeds silently, but after hunger is satisfied, it amuses itself with various jabberings, swims about, moves its head backward and forward, throws water over its back, shoots along the surface, half flying, half running, and seems quite playful. If alarmed, the Mallard springs up at once with a bound, rises obliquely to a considerable height, and flies off with great speed, the wings producing a whistling sound. The flight is made by repeated flaps, without sailing, and when in full flight its speed is hardly less than a hundred miles an hour.”

Early in spring the male and female seek a nesting place, building on the ground, in marshes or among water plants, sometimes on higher ground, but never far from water. The nest is large and rudely made of sedges and coarse grasses, seldom lined with down or feathers. In rare instances it nests in trees, using the deserted nests of hawks, crows, or other large birds. Six or eight eggs of pale dull green are hatched, and the young are covered over with down. When the female leaves the nest she conceals the eggs with hay, down, or any convenient material. As soon as hatched the chicks follow the mother to the water, where she attends them devotedly, aids them in procuring food, and warns them of danger. While they are attempting to escape, she feigns lameness to attract to herself the attention of the enemy. The chicks are wonderfully active little fellows, dive quickly, and remain under water with only the bill above the surface.

On a lovely morning, before the sun has fairly indicated his returning presence, there can be no finer sight than the hurrying pinions, or inspiring note than the squawk, oft repeated, of these handsome feathered creatures, as they seek their morning meal in the lagoons and marshes.

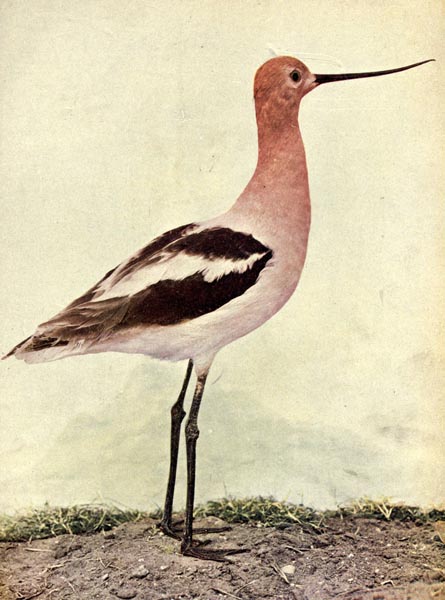

THE AMERICAN AVOCET.

HITE SNIPE, Yelper, Lawyer, and Scooper are some of the popular names applied in various localities to this remarkably long-legged and long and slender-necked creature, which is to be found in temperate North America, and, in winter, as far south as Cuba and Jamaica. In north-eastern Illinois the Avocet generally occurs in small parties the last of April and the first of May, and during September and the early part of October, when it frequents the borders of marshy pools. The bird combines the characteristics of the Curlew and the Godwit, the bill being recurved.

The cinnamon color on the head and neck of this bird varies with the individual; sometimes it is dusky gray around the eye, especially in the younger birds.

The Avocet is interesting and attractive in appearance, without having any especially notable characteristics. He comes and goes and is rarely seen by others than sportsmen.

american avocet.

american avocet.From col. F. M. Woodruff.

BIRD SONG—Continued from page 1.

Many of our singing birds may be easily identified by any one who carries in his mind the images which are presented in our remarkable pictures. See the birds at home, as it were, and hear their songs.

Those who fancy that few native birds live in our parks will be surprised to read the following list of them now visible to the eyes of so careful an observer as Mr. J. Chester Lyman.

“About the 20th of May I walked one afternoon in Lincoln Park with a friend whose early study had made him familiar with birds generally, and we noted the following varieties:

| 1 | Magnolia Warbler. | |

| 2 | Yellow Warbler. | |

| 3 | Black Poll Warbler. | |

| 4 | Black-Throated Blue Warbler. | |

| 5 | Black-Throated Queen Warbler. | |

| 6 | Blackburnian Warbler. | |

| 7 | Chestnut-sided Warbler. | |

| 8 | Golden-crowned Thrush. | |

| 9 | Wilson’s Thrush. | |

| 10 | Song Thrush. | |

| 11 | Catbird. | |

| 12 | Bluebird. | |

| 13 | Kingbird. | |

| 14 | Least Fly Catcher. | |

| 15 | Wood Pewee Fly Catcher. | |

| 16 | Great Crested Fly Catcher. | |

| 17 | Red-eyed Vireo. | |

| 18 | Chimney Swallow. | |

| 19 | Barn Swallow. | |

| 20 | Purple Martin. | |

| 21 | Red Start. | |

| 22 | House Wren. | |

| 23 | Purple Grackle. | |

| 24 | White-throated Sparrow. | |

| 25 | Song Sparrow. | |

| 26 | Robin. | |

| 27 | Blue Jay. | |

| 28 | Red-Headed Woodpecker. | |

| 29 | Kingfisher. | |

| 30 | Night Hawk. | |

| 31 | Yellow-Billed Cuckoo. | |

| 32 | Scarlet Tanager, Male and Female. | |

| 33 | Black and White Creeper. | |

| 34 | Gull, or Wilson’s Tern. | |

| 35 | The Omni-present English Sparrow. |

“On a similar walk, one week earlier, we saw about the same number of varieties, including, however, the Yellow Breasted Chat, and the Mourning, Bay Breasted, and Blue Yellow Backed Warblers.”

The sweetest songsters are easily accessible, and all may enjoy their presence.

C. C. Marble.

[to be continued.]

THE CANVAS-BACK DUCK.

HITE-BACK, Canard Cheval, (New Orleans,) Bull-Neck, and Red-Headed Bull-Neck, are common names of the famous Canvas-Back, which nests from the northern states, northward to Alaska. Its range is throughout nearly all of North America, wintering from the Chesapeake southward to Guatemala.

“The biography of this duck,” says Mabel Osgood Wright, “belongs rather to the cook-book than to a bird list,” even its most learned biographers referring mainly to its “eatable qualities,” Dr. Coues even taking away its character in that respect when he says “there is little reason for squealing in barbaric joy over this over-rated and generally under-done bird; not one person in ten thousand can tell it from any other duck on the table, and only then under the celery circumstances,” referring to the particular flavor of its flesh, when at certain seasons it feeds on vallisneria, or “water celery,” which won its fame. This is really not celery at all, but an eel-grass, not always found through the range of the Canvas-Back. When this is scarce it eats frogs, lizards, tadpoles, fish, etc., so that, says Mrs. Osgood, “a certificate of residence should be sold with every pair, to insure the inspiring flavor.”

The opinion held as to the edible qualities of this species varies greatly in different parts of the country. No where has it so high a reputation as in the vicinity of Chesapeake Bay, where the alleged superiority of its flesh is ascribed to the abundance of “water celery.” That this notion is erroneous is evident from the fact that the same plant grows in far more abundance in the upper Mississippi Valley, where also the Canvas-Back feeds on it. Hence it is highly probable that fashion and imagination, or perhaps a superior style of cooking and serving, play a very important part in the case. In California, however, where the “water celery” does not grow, the Canvas-Back is considered a very inferior bird for the table.

It has been hunted on Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries with such inconsiderate greed that its numbers have been greatly reduced, and many have been driven to more southern waters.

In and about Baltimore, the Canvas-Back, like the famous terrapin, is in as high favor for his culinary excellence, as are the women for beauty and hospitality. To gratify the healthy appetite of the human animal this bird was doubtless sent by a kind Providence, none the less mindful of the creature comforts and necessities of mankind than of the purely aesthetic senses.

canvas-back duck.

canvas-back duck.From col. F. M. Woodruff.

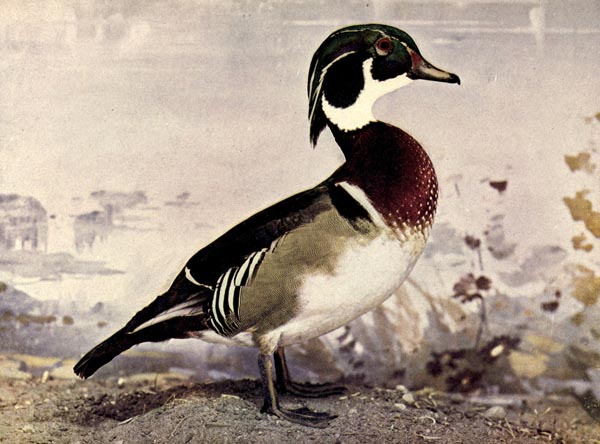

wood duck.

wood duck.From col. F. M. Woodruff.

THE WOOD DUCK.

A great many people think that this is the most beautiful bird of North America. It is called Wood Duck because it usually makes its nest in the hollow of a tree that overhangs the water. If it can find a squirrel’s or woodpecker’s hole in some stump or tree, there it is sure to nest.

A gentleman who delighted in watching the Wood Duck, tells about one that built her nest in the hollow of a tree that hung over the water. He was anxious to see how the little ones, when hatched, would get down.

In a few days he knew that the ducklings were out, for he could hear their pee, pee, pee. They came to the edge of the nest, one by one, and tumbled out into the water.

You know a duck can swim as soon as it comes out of the egg.

Sometimes the nest is in the hollow of a tree that is a short distance from the water.

Now how do you suppose the ducklings get there as they do?

If the nest is not far from the ground, the mother bird lets them drop from it on the dried grass and leaves under the tree. She then carries them in her bill, one by one, to the water and back to the nest.

If the nest should be far from the ground, she carries them down one by one.

This same gentleman says that he once saw a Wood Duck carry down thirteen little ones in less than ten minutes. She took them in her bill by the back of the neck or the wing.

When they are a few days old she needs only to lead the way and the little ones will follow.

The Wood Duck is also called Summer Duck. This is because it does not stay with us during the winter, as most ducks do.

It goes south to spend the winter and comes back north early in the spring.

THE WOOD DUCK.

UITE the most beautiful of the native Ducks, with a a richness of plumage which gives it a bridal or festive appearance, this bird is specifically named Spousa, which means betrothed. It is also called Summer Duck, Bridal Duck, Wood Widgeon, Acorn Duck and Tree Duck.

It is a fresh water fowl, and exclusively so in the selection of its nesting haunts. It inhabits the whole of temperate North America, north to the fur countries, and is found in Cuba and sometimes in Europe. Its favorite haunts are wooded bottom-lands, where it frequents the streams and ponds, nesting in hollows of the largest trees. Sometimes a hole in a horizontal limb is chosen that seems too small to hold the Duck’s plump body, and occasionally it makes use of the hole of an Owl or Woodpecker, the entrance to which has been enlarged by decay.

Wilson visited a tree containing a nest of a Wood or Summer Duck, on the banks of Tuckahoe river, New Jersey. The tree stood on a declivity twenty yards from the water, and in its hollow and broken top, about six feet down, on the soft decayed wood were thirteen eggs covered with down from the mother’s breast. The eggs were of an exact oval shape, the surface smooth and fine grained, of a yellowish color resembling old polished ivory. This tree had been occupied by the same pair, during nesting time, for four successive years. The female had been seen to carry down from the nest thirteen young, one by one, in less than ten minutes. She caught them in her bill by the wing or back of the neck, landed them safely at the foot of the tree, and finally led them to the water. If the nest be directly over the water, the little birds as soon as hatched drop into the water, breaking their fall by extending their wings.

Many stories are told of their attachment to their nesting places. For several years one observer saw a pair of Wood Ducks make their nest in the hollow of a hickory which stood on the bank, half a dozen yards from a river. In preparing to dam the river near this point, in order to supply water to a neighboring city, the course of the river was diverted, leaving the old bed an eighth of a mile behind, notwithstanding which the ducks bred in the old place, the female undaunted by the distance which she would have to travel to lead her brood to the water.

While the females are laying, and afterwards when sitting, the male usually perches on an adjoining limb and keeps watch. The common note of the drake is peet-peet, and when standing sentinel, if apprehending danger, he makes a noise not unlike the crowing of a young cock, oe-eek. The drake does not assist in sitting on the eggs, and the female is left in the lurch in the same manner as the Partridge.

The Wood Duck has been repeatedly tamed and partially domesticated. It feeds freely on corn meal soaked in water, and as it grows, catches flies with great dexterity.

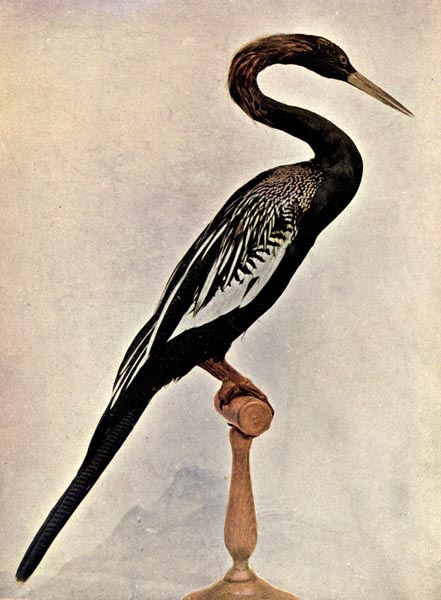

anhinga or snake bird.

anhinga or snake bird.From col. F. C. Baker.

THE ANHINGA OR SNAKE BIRD.

HE Snake Bird is very singular indeed in appearance, and interesting as well in its habits. Tropical and sub-tropical America, north to the Carolinas and Southern Illinois, where it is a regular summer resident, are its known haunts. Here it is recognized by different names, as Water Turkey, Darter, and Snake Bird. The last mentioned seems to be the most appropriate name for it, as the shape of its head and neck at once suggest the serpent. In Florida it is called the Grecian Lady, at the mouth of the Mississippi, Water Crow, and in Louisiana, Bec a Lancette. It often swims with the body entirely under water, its head and long neck in sight like some species of water snakes, and has no doubt more than once left the impression on the mind of the superstitious sailor that he has seen a veritable sea serpent, the fear of which lead him to exaggerate the size of it.

This bird so strange in looks and action is common in summer in the South Atlantic and Gulf States, frequenting the almost impenetrable swamps, and is a constant resident of Florida.

As a diver the Snake Bird is the most wonderful of all the Ducks. Like the Loon it can disappear instantly and noiselessly, swim a long distance and reappear almost in an opposite direction to that in which naturally it would be supposed to go. And the ease with which, when alarmed, it will drop from its perch and leave scarcely a ripple on the surface of the water, would appear incredible in so large a bird, were it not a well known fact. It has also the curious habit of sinking like a Grebe.

The nests of the Anhinga are located in various places, sometimes in low bushes at a height from the ground of only a few feet, or in the upper branches of high trees, but always over water. Though web footed, it is strong enough to grasp tightly the perch on which it nests. This gives it a great advantage over the common Duck which can nest only on the ground. Sometimes Snake Birds breed in colonies with various species of Herons. From three to five eggs, bluish, or dark greenish white, are usually found in the nest.

Prof. F. C. Baker, secretary of the Chicago Academy of Sciences, to whom we are indebted for the specimen presented here, captured this bird at Micco, Brevard Co., Florida, in April, 1889. He says he found a peculiar parasite in the brain of the Anhinga.

The Anhingas consist of but one species, which has a representative in the warmer parts of each of the great divisions of the earth. The number seen together varies from eight or ten to several hundred.

The hair-like feathers on the neck form a sort of loose mane.

When asleep the bird stands with its body almost erect. In rainy weather it often spends the greater part of the day in an erect attitude, with its neck and head stretched upward, remaining perfectly motionless, so that the water may glide off its plumage. The fluted tail is very thick and beautiful and serves as a propeller as well as a rudder in swimming.

THE AMERICAN WOODCOCK.

SN’T this American Woodcock, or indeed any member of the family, a comical bird? His head is almost square, and what a remarkable eye he has! It is a seeing eye, too, for he does not require light to enable him to detect the food he seeks in the bogs. He has many names to characterize him, such as Bog-sucker, Mud Snipe, Blind Snipe. His greatest enemies are the pot hunters, who nevertheless have nothing but praise to bestow upon him, his flesh is so exquisitely palatable. Even those who deplore and deprecate the destruction of birds are not unappreciative of his good qualities in this respect.

The Woodcock inhabits eastern North America, the north British provinces, the Dakotas, Nebraska and Kansas, and breeds throughout the range.

Night is the time when the Woodcock enjoys life. He never flies voluntarily by day, but remains secluded in close and sheltered thickets till twilight, when he seeks his favorite feeding places. His sight is imperfect by day, but at night he readily secures his food, assisted doubtless by an extraordinary sense of smell. His remarkably large and handsome eye is too sensitive for the glare of the sun, and during the greater part of the day he remains closely concealed in marshy thickets or in rank grass. In the morning and evening twilight and on moonlight nights, he seeks his food in open places. The early riser may find him with ease, but the first glow from the rays of the morning sun will cause his disappearance from the landscape.

He must be looked for in swamps, and in meadows with soft bottoms. During very wet seasons he seeks higher land—usually cornfields—and searches for food in the mellow plowed ground, where his presence is indicated by holes made by his bill. In seasons of excessive drought the Woodcock resorts in large numbers to tide water creeks and the banks of fresh water rivers. So averse is he to an excess of water, that after continued or very heavy rains he has been known suddenly to disappear from widely extended tracts of country.

A curious habit of the Woodcock, and one that is comparatively little known, is that of carrying its young in order to remove them from danger. So many trustworthy naturalists maintain this to be true that it must be accepted as characteristic of this interesting bird. She takes her young from place to place in her toe grasps as scarcity of food or safety may require.

As in the case of many birds whose colors adapt them to certain localities or conditions of existence, the patterns of the beautiful chestnut parts of the Woodcock mimic well the dead leaves and serve to protect the female and her young. The whistle made by their wings when flying is a manifestation of one of the intelligences of nature.

The male Woodcock, it is believed, when he gets his “intended” off entirely to himself, exhibits in peculiar dances and jigs that he is hers and hers only, or rises high on the wing cutting the most peculiar capers and gyrations in the air, protesting to her in the grass beneath the most earnest devotion, or advertising to her his whereabouts.

american woodcock.

american woodcock.From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences.

THE WOODCOCK.

Here is a bird that is not often seen in the daytime. During the day he stays in the deep woods or among the tall marsh grasses.

It is at twilight that you may see him. He then comes out in search of food.

Isn’t he an odd-looking bird? His bill is made long so that he can bore into the soft ground for earthworms.

You notice his color is much like the Ruffed Grouse in June “BIRDS.” This seems to be the color of a great many birds whose home is among the grasses and dried leaves. Maybe you can see a reason for this.

Those who have watched the Woodcock carefully, say that he can move the tip end of the upper part of his bill. This acts like a finger in helping him to draw his food from the ground.

What a sight it must be to see a number of these queer looking birds at work getting their food. If they happen to be in a swampy place, they often find earthworms by simply turning over the dead leaves.

If there should be, near by, a field that has been newly plowed, they will gather in numbers, at twilight, and search for worms.

The Woodcock has short wings for his size. He seems to be able to fly very fast. You can imagine how he looks while flying—his long bill out in front and his legs hanging down.

THE AMERICAN SCOTER.

HE specimen we give of the American Scoter is one of unusual rarity and beauty of plumage. It was seen off the government pier, in Chicago, in November, 1895, and has been much admired.

The Scoter has as many names as characteristics, being called the Sea Coot, the Butter-billed, and the Hollow-billed Coot. The plumage of the full grown male is entirely black, while the female is a sooty brown, becoming paler below. She is also somewhat smaller.

This Duck is sometimes found in great numbers along the entire Atlantic coast where it feeds on small shell fish which it secures by diving. A few nest in Labrador, and in winter it is found in New Jersey, on the Great Lakes, and in California. The neighborhoods of marshes and ponds are its haunts, and in the Hudson Bay region the Scoter nests in June and July.

The nest is built on the ground near water. Coarse grass, feathers, and down are commonly used to make it comfortable, while it is well secreted in hollows in steep banks and cliffs. The eggs are from six to ten, of a dull buff color.

Prof. Cooke states that on May 2, 1883, fifty of these ducks were seen at Anna, Union county, Illinois, all busily engaged in picking up millet seed that had just been sown. If no mistake of identification was made in this case, the observation apparently reveals a new fact in the habits of the species, which has been supposed to feed exclusively in the water, and to subsist generally on fishes and other aquatic animal food.

white-winged scoter.

white-winged scoter.From col. F. M. Woodruff.

OLD ABE.

“I’d rather capture Old Abe,” said Gen. Sterling Price, of the Confederate Army, “than a whole brigade.”

LD ABE” was the live war Eagle which accompanied the Eighth Wisconsin regiment during the War of the Rebellion. Much of a more or less problematical character has been written about him, but what we regard as authentic we shall present in this article. Old Abe was a fine specimen of the Bald Eagle, very like the one figured in this number of Birds. Various stories are told of his capture, but the most trustworthy account is that Chief Sky, a Chippewa Indian, took him from the nest while an Eaglet. The nest was found on a pine tree in the Chippewa country, about three miles from the mouth of the Flambeau, near some rapids in the river. He and another Indian cut the tree down, and, amid the menaces of the parent birds, secured two young Eagles about the size of Prairie Hens. One of them died. The other, which lived to become historical, was sold to Daniel McCann for a bushel of corn. McCann carried it to Eau Claire, and presented it to a company then being organized as a part of the Eighth Wisconsin Infantry.

What more appropriate emblem than the American Bald-headed Bird could have been thus selected by the patriots who composed this regiment of freemen! The Golden Eagle (of which we shall hereafter present a splendid specimen,) with extended wings, was the ensign of the Persian monarchs, long before it was adopted by the Romans. And the Persians borrowed the symbol from the Assyrians. In fact, the symbolical use of the Eagle is of very remote antiquity. It was the insignia of Egypt, of the Etruscans, was the sacred bird of the Hindoos, and of the Greeks, who connected him with Zeus, their supreme deity. With the Scandinavians the Eagle is the bird of wisdom. The double-headed Eagle was in use among the Byzantine emperors, “to indicate their claims to the empire of both the east and the west.” It was adopted in the 14th century by the German emperors. The arms of Prussia were distinguished by the Black Eagle, and those of Poland by the White. The great Napoleon adopted it as the emblem of Imperial France.

Old Abe was called by the soldiers the “new recruit from Chippewa,” and sworn into the service of the United States by encircling his neck with red, white, and blue ribbons, and by placing on his breast a rosette of colors, after which he was carried by the regiment into every engagement in which it participated, perched upon a shield in the shape of a heart. A few inches above the shield was a grooved crosspiece for the Eagle to rest upon, on either end of which were three arrows. When in line Old Abe was always carried on the left of the color bearer, in the van of the regiment. The color bearer wore a belt to which was attached a socket for the end of the staff, which was about five feet in length. Thus the Eagle was high above the bearer’s head, in plain sight of the column. A ring of leather was fastened to one of the Eagle’s legs to which was connected a strong hemp cord about twenty feet long.

Old Abe was the hero of about twenty-five battles, and as many skirmishes. Remarkable as it may appear, not one bearer of the flag, or of the Eagle, always shining marks for the enemy’s rifles, was ever shot down. [Pg 36] Once or twice Old Abe suffered the loss of a few feathers, but he was never wounded.

The great bird enjoyed the excitement of carnage. In battle he flapped his wings, his eyes blazed, and with piercing screams, which arose above the noise of the conflict, seemed to urge the company on to deeds of valor.

David McLane, who was the first color bearer to carry him into battle, said:

“Old Abe, like all old soldiers, seemed to dread the sound of musketry but with the roll of artillery he appeared to be in his glory. Then he screamed, spread his wings at every discharge, and reveled in the roar and smoke of the big guns.” A correspondent who watched him closely said that when a battle had fairly begun Old Abe jumped up and down on his perch with such wild and fearful screams as an eagle alone can utter. The louder the battle, the fiercer and wilder were his screams.

Old Abe varied his voice in accord with his emotions. When surprised he whistled a wild melody of a melancholy softness; when hovering over his food he gave a spiteful chuckle; when pleased to see an old friend he seemed to say: “How do you do?” with a plaintive cooing. In battle his scream was wild and commanding, a succession of five or six notes with a startling trill that was inspiring to the soldiers. Strangers could not approach or touch him with safety, though members of the regiment who treated him with kindness were cordially recognized by him. Old Abe had his particular friends, as well as some whom he regarded as his enemies. There were men in the company whom he would not permit to approach him. He would fly at and tear them with his beak and talons. But he would never fight his bearer. He knew his own regiment from every other, would always accompany its cheer, and never that of any other regiment.

Old Abe more than once escaped, but was always lured by food to return. He never seemed disposed to depart to the blue empyrean, his ancestral home.

Having served three years, a portion of the members of Company C were mustered out, and Old Abe was presented to the state of Wisconsin. For many years, on occasions of public exercise or review, like other illustrious veterans, he excited in parade universal and enthusiastic attention.

He occupied pleasant quarters in the State Capitol at Madison, Wisconsin, until his death at an advanced age.

snowy heron or little egret.

snowy heron or little egret.From col. F. M. Woodruff. CHICAGO COLORTYPE CO.

THE SNOWY HERON.

“What does it cost this garniture of death?

It costs the life which God alone can give;

It costs dull silence where was music’s breath,

It costs dead joy, that foolish pride may live.

Ah, life, and joy, and song, depend upon it,

Are costly trimmings for a woman’s bonnet!”

—May Riley Smith.

EMPERATE and tropical America, from Long Island to Oregon, south to Buenos Ayres, may be considered the home of the Snowy Heron, though it is sometimes seen on the Atlantic coast as far as Nova Scotia. It is supposed to be an occasional summer resident as far north as Long Island, and it is found along the entire gulf coast and the shores of both oceans. It is called the Little White Egret, and is no doubt the handsomest bird of the tribe. It is pure white, with a crest composed of many long hair-like feathers, a like plume on the lower neck, and the same on the back, which are recurved when perfect.

Snowy Herons nest in colonies, preferring willow bushes in the marshes for this purpose. The nest is made in the latter part of April or early June. Along the gulf coast of Florida, they nest on the Mangrove Islands, and in the interior in the willow ponds and swamps, in company with the Louisiana and Little Blue Herons. The nest is simply a platform of sticks, and from two to five eggs are laid.

Alas, plume hunters have wrought such destruction to these lovely birds that very few are now found in the old nesting places. About 1889, according to Mr. F. M. Woodruff, this bird was almost completely exterminated in Florida, the plume hunters transferring their base of operation to the Texas coast of the Gulf, and the bird is now in a fair way to be utterly destroyed there also. He found them very rare in 1891 at Matagorda Bay, Texas. This particular specimen is a remarkably fine one, from the fact that it has fifty-two plumes, the ordinary number being from thirty to forty.

Nothing for some time has been more commonly seen than the delicate airy plumes which stand upright in ladies’ bonnets. These little feathers, says a recent writer, were provided by nature as the nuptial adornment of the White Heron. Many kind-hearted women who would not on any account do a cruel act, are, by following this fashion, causing the continuance of a great cruelty. If ladies who are seemingly so indifferent to the inhumanity practiced by those who provide them with this means of adornment would apply to the Humane Education Committee, Providence, R. I., for information on the subject, they would themselves be aroused to the necessity of doing something towards the protection of our birds. Much is, however, being done by good men and women to this end.

The Little Egret moves through the air with a noble and rapid flight. It is curious to see it pass directly overhead. The head, body and legs are held in line, stiff and immovable, and the gently waving wings carry the bird along with a rapidity that seems the effect of magic.

An old name of this bird was Hern, or Hernshaw, from which was derived the saying, “He does not know a Hawk from a Hernshaw.” The last word has been corrupted into “handsaw,” rendering the proverb meaningless.

SUMMARY

Page 3.

BALD EAGLE.—Haliæetus leucocephalus. Other names: “White-headed Eagle,” “Bird of Washington,” “Gray Eagle,” “Sea Eagle.” Dark brown. Head, tail, and tail coverts white. Tarsus, naked. Young with little or no white.

Range—North America, breeding throughout its range.

Nest—Generally in tall trees.

Eggs—Two or three, dull white.

Page 8.

SEMI-PALMATED PLOVER.—Ægialitis semi-palmata. Other names: “American Ring Plover,” “Ring Neck,” “Beach Bird.” Front, throat, ring around neck, and entire under parts white; band of deep black across the breast; upper parts ashy brown. Toes connected at base.

Range—North America in general, breeding in the Arctic and sub-arctic districts, winters from the Gulf States to Brazil.

Nest—Depression in the ground, with lining of dry grass.

Eggs—Three or four; buffy white, spotted with chocolate.

Page 11.

MALLARD DUCK.—Anas boschas. Other names: “Green-head,” “Wild Duck.” Adult male, in fall, winter, and spring, beautifully colored; summer, resembles female—sombre.

Range—Northern parts of Northern Hemisphere.

Nest—Of grasses, on the ground, usually near the water.

Eggs—Six to ten; pale green or bluish white.

Page 15.

AMERICAN AVOCET.—Recurvirostra americana. Other names: “White Snipe,” “Yelper,” “Lawyer,” “Scooper.”

Range—Temperate North America.

Nest—A slight depression in the ground.

Eggs—Three or four; pale olive or buffy clay color, spotted with chocolate.

Page 20.

CANVAS-BACK.—Aythya vallisneria. Other names: “White-Back,” “Bull-Neck,” “Red-Headed Bull-Neck.”

Range—North America. Breeds only in the interior, from northwestern states to the Arctic circle; south in winter to Guatemala.

Nest—On the ground, in marshy lakesides.

Eggs—Six to ten; buffy white, with bluish tinge.

Page 21.

WOOD DUCK.—Aix sponsa. Coloring varied; most beautiful of ducks. Other names: “Summer Duck,” “Bridal Duck,” “Wood Widgeon,” “Tree Duck.”

Range—North America. Breeds from Florida to Hudson’s Bay; winters south.

Nest—Made of grasses, usually placed in a hole in tree or stump.

Eggs—Eight to fourteen; pale, buffy white.

Page 26.

SNAKE BIRD.—Anhinga anhinga. Other names: “Water Turkey,” “Darter,” “Water Crow,” “Grecian Lady.”

Range—Tropical and sub-tropical America.

Nest—Of sticks, lined with moss, rootlets, etc., in a bush or tree over the water.

Eggs—Two to four; bluish white, with a chalky deposit.

Page 30.

AMERICAN WOODCOCK.—Philohela minor. Other names: “Bog-sucker,” “Mud Snipe,” “Blind Snipe.”

Range—Eastern North America, breeding throughout its range.

Nest—Of dried leaves, on the ground.

Eggs—Four; buffy, spotted with shades of rufous.

Page 33.

WHITE-WINGED SCOTER.—Oidemia deglandi. Other names: “American Velvet Scoter,” “White-winged Coot,” “Uncle Sam Coot.”

Range—Northern North America; breeding in Labrador and the fur countries; south in winter.

Nest—On the ground, beneath bushes.

Eggs—Six to ten; pale, dull buff.

Page 38.

SNOWY HERON.—Ardea candidissima. Other names: “Little Egret,” “White-crested Egret,” “White Poke.”

Range—Tropical and temperate America.

Nest—A platform of sticks, in bushes, over water.

Eggs—Three to five; pale, dull blue.