Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Volume 98, May 24, 1890

Author: Various

Editor: F. C. Burnand

Release date: January 21, 2010 [eBook #31039]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Neville Allen, Malcolm Farmer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Miss Jenny Miss Polly |

} |

By the Sisters Leamar. |

| The Soldier Doll The Soldier Doll |

} |

By the Two Armstrongs. |

Scene—A Nursery. Enter Miss Jenny and Miss Polly, who perform a blameless step-dance with an improving chorus.

Oh, isn't it jolly! we've each a new dolly,

And one is a Soldier, the other's a Tar!

We're fully contented with what's been presented,

Such good little children we both of us are!

[They dance up to a cupboard, from which they bring out two large Dolls, which they place on chairs.

Miss J. Don't they look nice!

Come, Polly, let us strive

To make ourselves believe that they're alive!

Miss P. (addressing Sailor D.). I'm glad you're mine. I dote on all that's nautical.

The Sailor D. (opening his eyes suddenly). Excuse me, Miss, your sister's more my sort o' gal!

[Kisses his hand to Miss J., who shrinks back, shocked and alarmed.

Miss J. Oh, Polly, did you hear? I feel so shy!

The Soldier D. (with mild self-assertion). I can say "Pa" and "Ma"—and wink my eye.

[Does so at Miss P., who runs in terror to Miss J.'s side.

Miss J. Why, both are showing signs of animation!

Miss P. Who'd think we had such strong imagination!

The Soldier Doll (aside to the Sailor D.). I say, old fellow, we have

caught their fancy—

In each of us they now a real man see!

Let's keep it up!

The Sailor D. (dubiously). D'ye think as we can do it?

The Soldier D. You stick by me, and I will see you through it.

Sit up, and turn your toes out,—don't you loll;

Put on the Man, and drop the bloomin' Doll!

[The Sailor Doll pulls himself together, and rises from chair importantly.

The Sailor D. (in the manner of a Music-hall Chairman)—Ladies, with your kind leave, this gallant gent Will now his military sketch present.

[Miss J. and P. applaud; the Soldier D., after feebly expostulating, is induced to sing.

When I used to be displayed

In the Burlington Arcade,

With artillery arrayed

Underneath. Shoulder Hump!

I imagine that I made

All the Lady Dolls afraid,

I should draw my battle-blade

From its sheath, Shoulder Hump!

For I'm Mars's gallant son,

And my back I've shown to none,

Nor was ever seen to run

From the strife! &c.

Oh, the battles I'd have won,

And the dashing deeds have done,

If I'd ever fired a gun

In my life! &c.

By your right flank, wheel!

Let the front rank kneel!

With the bristle of the steel

To the foe.

Till their regiments reel,

At our rattling peal,

And the military zeal

We show!

[Repeat, with the whole company marching round after him.

The Soldier Doll. My friend will next oblige—this jolly Jack Tar Will give his song and chorus in charàck-tar!

[Same business with Sailor D.

In costume I'm

So maritime,

You'd never suppose the fact is,

That with the Fleet

In Regent Street,

I'd precious little naval practice!

There was saucy craft,

Rigged fore an' aft,

Inside o' Mr. Cre-mer's.

From Noah's Arks to Clipper-built barques,

Like-wise mechanical stea-mers.

But to navigate the Serpentine,

Yeo ho, my lads, ahoy!

With clockwork, sails, or spirits of wine,

Yeo-ho, my lads, ahoy!

I did respeckfully decline,

So I was left in port to pine,

Which wasn't azactually the line

Of a rollicking Sailor Boy,

Yeo-ho! Of a rollicking Sailor Bo-oy!

Yes, there was lots Of boats and yachts,

Of timber and of tin, too;

But one and all Was far too small

For a doll o' my size to get into!

I was too big On any brig

To ship without disas-ter,

And it wouldn't never do

When the cap'n and the crew

Were a set o' little swabs all plas-ter!

An Ark is p'raps The berth for chaps

As is fond o' Natural Hist'ry.

But I sez to Shem

And the rest o' them,

"How you get along at all's a myst'ry!

With a Wild Beast Show

Let loose below,

And four fe-males on deck too!

I never could agree

With your happy fami-lee,

And your lubberly ways I objeck to."

[Chorus. Hornpipe by the company, after which the Soldier Doll advances condescendingly to Miss Jenny.

The Sold. D. Invincible I'm reckoned by the Ladies.

But yield to you—though conquering my trade is!

Miss J. (repulsing him). Oh, go away, you great conceited thing, you!

[The Sold. D. persists in offering her attentions.

Miss P. (watching them bitterly). To be deserted by one's doll does sting you!

[The Sailor D. approaches.

The Sailor D. (to Miss P.) Let me console you, Miss, a Sailor Doll

As swears his 'art was ever true to Poll!

Miss P. (indignantly to Miss J.) Your Sailor's teasing me to be his idol! Do make him stop—spitefully—When you've quite done with my doll!

Miss J. (scornfully). If you suppose I want your wretched warrior, I'm sorry for you!

Miss P. I for you am sorrier.

Miss J. (weeping, R.). Polly preferred to me—what ignominy!

Miss P. (weeping, L.). My horrid Sailor jilting me for Jenny!

[The two Dolls face one another, c.

Sailor D. (to Soldier D.). You've made her sluice her skylights now, you swab!

Soldier D. (to Sailor D.). As you have broke her heart, I'll break your nob!

[Hits him.

Sailor D. (in a pale fury). This insult must be blotted out in bran!

Soldier D. (fiercely). Come on, I'll shed your sawdust—if I can!

[Miss J. and P. throw themselves between the combatants.

Miss J. For any mess you make we shall be scolded,

So wait until a drugget we've unfolded!

[They lay down drugget on Stage.

The Soldier D. (politely). No hurry, Miss, we don't object to waiting.

The Sailor D. (aside). His valour—like my own—'s evaporating!

(Defiantly to Soldier D.). On guard! You'll see how soon I'll run you through!

(Confidentially). (If you will not prod me, I won't pink you.)

The Soldier D. Through your false kid my deadly blade I'll pass!

(Confidentially). (Look here, old fellow, don't you be a hass!)

[They exchange passes at a considerable distance.

The Sailor D. (aside). Don't lose your temper now!

Sold. D. Don't get excited.

Do keep a little farther off!

Sail. D. Delighted!

[Wounds Soldier D. by misadventure.

Sold. D. (annoyed). There now, you've gone and made upon my wax a dent!

Sail. D. Excuse me, it was really quite an accident.

Sold. D. (savagely). Such clumsiness would irritate a saint!

[Stabs Sailor Doll.

Miss J. and P. (imploringly). Oh, stop! the sight of sawdust turns us faint!

[They drop into chairs, swooning.

The Sailor D. I'll pay you out for that!

[Stabs Soldier D.

Sold. D. Right through you've poked me!

Sailor D. So you have me!

Sold. D. You shouldn't have provoked me!

[They fall transfixed.

Sailor D. (faintly). Alas, we have been led away by vanity.

Dolls shouldn't try to imitate humanity!

[Dies.

Soldier D. For, if they do, they'll end like us, unpitied,

Each on the other's sword absurdly spitted!

[Dies. Miss J. and P. revive, and bend sadly over the corpses.

Miss Jenny. From their untimely end we draw this moral,

How wrong it is, even for dolls, to quarrel!

Miss Polly. Yes, Jenny, in the fate of these poor fellows see

What sad results may spring from female jealousy!

[They embrace penitently as Curtain falls.

[The Report of the Sweating Committee says that "the inefficiency of many of the lower class of workers, early marriages, and the tendency of the residuum of the population in large towns to form a helpless community, together with a low standard of life and the excessive supply of unskilled labour are the chief factors in producing sweating." The Committee's chief "recommendations" in respect of the evils of Sweating seem to be, the lime-washing of work-places and the multiplication of sanitary inspectors.]

Seventy-one Sittings, a many months' run,

Witnesses Two Hundred, Ninety and One:

Clergymen, guardians, factors, physicians,

Middlemen, labourers, smart statisticians,

Journalists, managers, Gentiles and Jews,

And this is the issue! A thing to amuse

A cynic, the chat of this precious Committee,

But moving kind hearts to despair blent with pity.

Cantuar., Derby, and mild Aberdeen,

Such anti-climax sure never was seen!

Onslow and Rothschild and Monkswell and Thring,

Are you content with the pitiful thing?

Dunraven out of it; lucky, my lad!

(Though your retirement seemed caused by a fad)

Was the Inquiry in earnest or sport?

What is the pith of this precious Report?

Sweating—which all the world joined to abuse—

Is not the fault of poor Russians or Jews;

'Tisn't the middleman more than the factor,

'Tisn't, no 'tisn't, the sub-contractor;

'Tisn't machinery. No! In fact,

What Sweating is, in a manner exact,

After much thinking we cannot define.

Who is to blame for it? Well, we incline[Pg 243]

To think that the Sweated (improvident elves!)

Are, at the bottom, to blame themselves!

They're poor of spirit, and weak of will,

They marry early, have little skill;

They herd together, all sexes and ages,

And take too tamely starvation wages;

And if they will do so, much to their shame,

How can the Capitalist be to blame?

Remedies? Humph! We really regret

We don't see our way to them. People must sweat,

Must stitch and starve till they almost drop;

But let it be done in a lime-washed shop!

To drudge in these dens is their destined fate,

But keep the dens in a decent state.

More inspectors, fewer bad smells,

These be our cures for the Sweaters' Hells!

Revolutions with rose-water cannot be made!

So it was said. But the horrors of Trade,

Competition's accursed fruit,

The woman a drudge, and the man a brute,

These, our Committee of Lordlings are sure,

Can only be met by the Rose-water Cure!

The Sweating Demon to exorcise

Exceeds the skill of the wealthy wise.

Still he must "grind the face of the poor."

(Though some of us have a faint hope, to be sure,

That the highly respectable Capitalist

To the Lords' mild lispings will kindly list.)

No; the Demon must work his will

On his ill-paid suffering victims still;

But—he'd better look with a little less dirt,

So sprinkle the brute with our Rose-water Squirt!!!

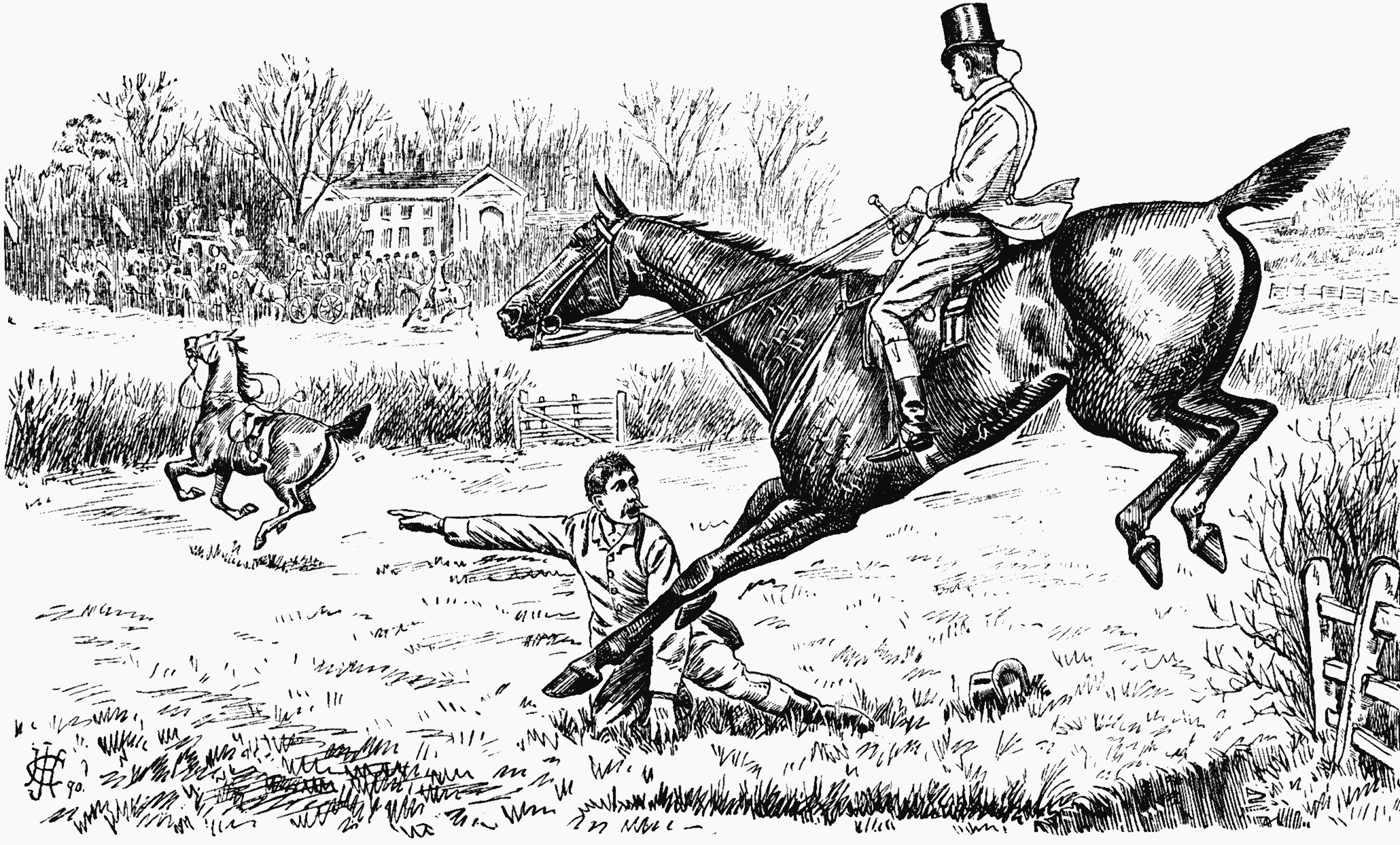

(An Incident in a "Point to Point" Race.)

Fallen Competitor (to his Bosom Friend, who now has the Race in hand). "Hi, George, old Man! Just catch my Horse, there's a good Chap!"

An Entertainment of a Good Stamp.—The Penny Postage Jubilee Exhibition at the Guildhall.

Example IV.—Treating of a passion which, in the well-meant process of making the best of it, unconsciously saddles its object with the somewhat harassing responsibility of competing with the Universal Provider.

Thou art all the world to me, love,

Thou art everything in one,

From my early cup of tea, love,

To my kidney underdone;

From my canter in the Row, love,

To my invitation lunch—

From my quiet country blow, love,

To my festive London Punch.

Thou art all in all to me, love,—

Thou art bread and meat and drink;

Thou art air and land and sea, love,—

Thou art paper, pens, and ink.

Thou art all of which I'm fond, love:

Thou art Whitstables from Rule's,—

"Little drops" with Spiers and Pond, love,—

Measures sweet at Mr. Poole's.

Thou art everything I lack, love,

From a month at Brighton gay

(Bar the journey there and back, love)

To the joys of Derby Day—

From the start from my abode, love,

With a team of frisky browns,

To the driving "on the road," love,

And the dry vin on the Downs!

Thou art all the world to me, love,—

Thou art all the thing contains;

Thou art honey from the bee, love,—

Thou art sugar from the canes.

Thou art—— stay! I've made a miss, love;

I'm forgetting, on my life!

Thou art all—excepting this, love,—

Your devoted servant's wife!

Sir,—Did Charles the First walk and talk half an hour after his head was cut off, or not?

Yours,

Sir,—Charles the First walked and talked one quarter of an hour, not half, as is erroneously supposed, after his decollation. We know this by two Dutch pictures which I had in my possession until only the other day, when I couldn't find them anywhere.

Yours,

Sir,—King Charles the First lost his head long before he came to the scaffold. I have the block now by me. From it the well-known wood-cut was taken.

Sir,—It is a very curious thing, but all the trouble was taken out of Charles's head and put into mine years ago by one of the greatest Charleses that ever lived, whose name was Dickens; and mine, without the "ENS," is

Yours truly,

P.S.—"'Mr. Dick sets us all right,' said My Aunt, quietly."

Mrs. Gamp's apartment wore, metaphorically speaking, a Bab-Balladish aspect, being considerably topsy-turvey, as rooms have a habit of being after any unusual ebullition of temper on the part of their occupants. It was certainly not swept and garnished, although its owner was preparing for the reception of a visitor. That visitor was Betsey Prig.

Mrs. Gamp's chimney-piece was ornamented with three photographs: one of herself, looking somewhat severe; one of her friend and bosom companion, Mrs. Prig, of far more amiable aspect; and one of a mysterious personage supposed to be Mrs. Harris.

"There! Now, drat you, Betsey, don't be long!" said Mrs. Gamp, apostrophising her absent friend. "For I'm in no mood for waiting, I do assure you. I'm easy pleased, but I must have my own way (as is always the best and wisest), and have it directly minit, when the fancy strikes me, else we shall part, and that not friendly, as I could wish, but bearin' malice in our 'arts."

"Betsey," said Mrs. Gamp, "I will now propoge a toast. My frequent pardner, Betsey Prig!"

"Which, altering the name to Sairah Gamp, I drink," said Mrs. Prig, "with love and tenderness!"

"Now, Sairah," said Mrs. Prig, "jining business with pleasure, as so often we've done afore, wot is this bothersome affair about which you wants to consult me? Are you a-goin' to call me over the Carpet once more, Sairey?"

"Drat the Carpet!" exclaimed Mrs. Gamp, with a vehement explosiveness whose utter unexpectedness quite disconcerted her friend.

"Is it Mrs. Harris?" inquired Mrs. Prig, solemnly.

"Yes, Betsy Prig, it is," snapped Mrs. Gamp, angrily, "that very person herself, and no other, which, after twenty years of trust, I never know'd nor never expected to, which it 'urts a feeling 'art even to name her name as henceforth shall be nameless betwixt us twain."

"Oh, shall it?" retorted Mrs. Prig, shortly. "Why bless the woman, if I'd said that, you'd ha' bitten the nose off my face, as is your nature to, as the poick says."

"Don't you say nothink against poicks, Betsey, and I'll say nothink against musicians," retorted Mrs. Gamp, mysteriously.

"Oh! then it was to call me over the Carpet that you sent for me so sudden and peremptory?" rejoined Mrs. Prig, with a smile.

"Drat the Carpet!!!" again ejaculated Mrs. Gamp, with astonishing fierceness. "Wot do you know about the Carpet, Betsey?"

"Why nothink at all, my dear; nor don't want to," replied Mrs. Prig, with surprise.

"Oh!" retorted Mrs. Gamp, "you don't, don't you? Well, then, I do, and it's time you did likewise, if pardners we are to remain who 'ave pardners been so long."

Mrs. Prig muttered something not quite audible, but which sounded suspiciously like, "'Ard wuck!"

"Which share and share alike is my mortar," continued Mrs. Gamp; "that as bin my princerple, and I've found it pay. But Injin Carpets for our mutual 'ome, of goldiun lustre and superfluos shine, as tho' we wos Arabian Knights, I cannot and I will not stand. It is the last stror as camels could not forgive. No, Betsey," added Mr. Gamp, in a violent burst of feeling, "nor crokydiles forget!"

"Bother your camels, and your crokydiles too!" retorted Mrs. Prig, with indifference. "Wy, Sairey, wot a tempest in a teapot, to be sure!"

Mrs. Gamp looked at her with amazement, incredulity, and indignation. "Wot!" she with difficulty ejaculated. "A—tempest—in—a—Teapot!! And does Betsey Prig, my pardner for so many years, call her friend a Teapot, and decline to take up Sairey's righteous quarrel with a Mrs. Harris?"

Then Mrs. Prig, smiling more scornfully, and folding her arms still tighter, uttered these memorable and tremendous words,—

"Wy, certainly she does, Sairey Gamp; most certainly she does. Wich I don't believe there's either rhyme or reason in sech an absurd quarrel!" After the utterance of which expressions she leaned forward, and snapped her fingers, and then rose to put on her bonnet, as one who felt that there was now a gulf between them which nothing could ever bridge across.

Adviser. Have you ever been present at a performance of The Dead Heart?

Patient. No; and I know nothing of a Tale of Two Cities.

A. Then surely you are well acquainted with All for Her?

P. I regret to reply in the negative.

A. Perhaps, you have seen the vision in The Bells, or the Corsican Brothers?

P. Alas! I am forced to confess I am familiar with neither!

A. Dear me! This is very sad! Strange! I will give you a prescription. Go to Paul Kauvar. You will then be provided with a thoroughly enjoyable mixture.

[Exit Patient to Drury Lane, where he passes a delightful evening.

The Lady once more left her frame in the Club Morning Room.

"So I was wrong," she murmured, as she wended her way towards the now familiar spot. "Poor Nellie, after all, was not forgotten. I am glad of it,—very glad indeed!"

And the flesh tints of Sir Peter Lely's paint-brush brightened, as a smile played across the canvas features.

"I' faith! the Military gentlemen are gallants, one and all! To be sure! Then how would it be possible that the foundress of a hospital should be overlooked? And one as comely as myself!"

So, well pleased, she journeyed on. As she reached the river, there was quite a crowd,—people were coming by rail, and boat, and omnibus. It was quite like the olden days of the Exhibitions at South Kensington. She passed through the turnstiles, and then found the cause of the excitement. There were all sorts of good things. A gallery full of pictures, and relics of battles ancient and modern, a museum of industrial work, a collection of everything interesting to a soldier. In the grounds were balloons, and fireworks, assaults at arms, and the best military bands. At length the Lady from the frame in the Club Morning Room stood before a portrait showing a good-natured face and a comely presence.

"And so there I am! And in my hands a model of the Hospital hard-by! 'Gad zooks!' as poor dear Rowley used to say, I have no cause for complaint! I thank those kind hearts who can find good in everything,—even in poor Nellie!"

And, thoroughly satisfied at the treatment she had received at the Sodgeries, Mistress Nell Gwynne returned to her haunt in the Club Morning Room.

A Glee Quartette.—Welcome to the Meister Glee Singers. Mr. Saxon, in spite of his name, is by no means brutal, though he might be pardoned for being so when he sees his colleague Mr. Saxton suiting everybody to a T. Mr. Hast has just as much speed as is necessary, and the fourth gentleman should be neither angry Norcross, since he always sings in tune. 'Tis a mad world, my Meisters, but, mad or not, we shall always be glad to hear your glees.

At the Dentist's.—"It won't hurt you in the least, and it will be out before you know where you are;" i.e., "You will suffer in the one minute and thirty-nine seconds I am tugging at your jaw, all the concentrated agony of forty-eight continuous hours of wrenching your crushed and tortured body off your staring and staggered head."

Wednesday.—Great Day everywhere. Mr. Punch appears. Crowds in Fleet Street. The Numbers up in the Office Window. Receptions, alarums, (eight day) excursions (there and back) to meet H.M. Stanley. Curfew at dusk. No followers allowed.

Thursday.—Crowds out to meet H. M. Stanley. Mrs. Nemo's sixth and last dance to meet Mr. H. M. Stanley, as he hasn't been to any of the others.

Friday.—Lecture by Mr. Charles Wyndham on "the block system," in the time of Charles the First. Admission by entrances only.

Saturday.—Centenary Celebration of a lot of things. Review of the events of the past month in Hyde Park, by the Editor of the Nineteenth Century, to meet Mr. Stanley. Ceremony of conferring the Order of the Adelphi on H. M. Stanley, by Messrs. Gatti.

Sunday.—Short services from Dover to Calais. No sermon. Collection in Hyde Park. H. M. Stanley goes to meet somebody else for a change.

Monday.—Expedition to find H. M. Stanley.

Tuesday.—Readings of the Barometer, and lecture on hot-house plants and French grapes, by Sir Somers Vine. At Tattersall's, Lecture on the approaching "Eve of the Derby," and the female dark races.

It has been finally settled that Mr. Phil Gorman, who will be remembered in connection with the catering department at all the public dinners held of late years in Sloshfield, is to be the next incumbent of the highest municipal office in that prosperous borough. Mrs. Gorman is a daughter of the celebrated local poet, James Posh, whose verse still occasionally adorns the Sloshfield Standard.

A remarkable incident is stated to have taken place at Lady B—— 's fancy dress ball. A gentleman, wearing the gorgeous costume of a Venetian Senator of the renaissance period, somewhat awkwardly entangled his spurs in the flowing train of a beautiful débutante, dressed to represent Diana the Huntress. Some of those in the immediate vicinity of the ill-used goddess aver that she was distinctly heard to say, "Pig!". Those who know her better declare, however, that, with her usual politeness, she merely remarked, "I beg your pardon." Hence the misconception, which is certainly pardonable.

The trees in the Park are now assuming their brightest verdure. It is interesting to note that the number of sparrows shows no signs of diminution.

Excellent subject Sir Arthur has chosen for his serious opera—Ivanhoe. It is now finally settled that the part of Rowena will not be entrusted to Mr. Herbert Campbell. It is whispered that the great effect will be the song of Isaac of York, magnificently orchestrated for fifteen Jews' harps, played by lads all under the age of twelve. They have already commenced practice under the eye of Sir Arthur, who himself is no unskilled performer on the ancient lyre of Jubal.

They have bin so jolly busy lately at the "Grand Hotel," and a reel grand Hotel it is too, that they wanted sum assistence in the werry himportant line of Waiters; so they werry naterally sent for me, and in course I went, and a werry nice cumferal place it is for ewerybody, both Waiters and Wisiters, and I can trewly say as I aint had not a singel complaint since I have been here.

Well, one day a young Swell came a sauntering in, about 4 o'clock, and wanted to know if he cood have a lunch for a gentleman, and in the hansomest room as there was in the house. Of course I was ekal to the ocashun, and told him, yes, he coud, and not only in the hansomest room in that house but in the hansomest room in Lundon, and I at wunce showed him into our Marble Pillow Room, which I coud see at a glarnce made a werry deep impression on his mind, which I was not at all surprized at, for it is about as near a approach to Paradise as you can resonably expect so werry near the Strand.

So I sets him down at a sweet little round table, and I puts a lovely gold candlestick on it, with two darling little cherubs a climing up it, jest as if they was a going for to lite the candle, and then he horders his simple luncheon, which it was jest a cup of our shuperior chocolate and two xquisite little beef and am sandwitches, and wile he eat and drank 'em he arsked me sech lots of questyuns as farely estonished me. Such as, how much did the four Marbel Pillows cost? So I said, about 200 pound, for I allers thinks as an hed Waiter should be reddy to anser any question as he is arsked, weather he knos anythink about it or not.

Then he wanted to know where we got all our bewtifool flowers from, and I told him as we had 'em in fresh every morning from the South of France along with our Shampane, which was made a purpose for us by the most sellebrated makers, and consisted of two sorts, wiz.: dry for the higneramuses and rich for the connysewers. So he ordered a bottle of the latter, and drunk two glasses of it, and then acshally made me drink one two, and sed as it was the finest as he had ewer tasted. He then asked me what made us line all the room with such bewtifool looking glass, and I told him as it was by order of most of the most bewtifoolest Ladys in Lundon, who came to dine there wunce or twice every week. So he said as how he shood drop in now and then to see 'em, for he thort as they gave a sort of relish to a good dinner. He then got up, and saying as he didn't want not no Bill, he throwed down a soverain and saying, "I shall allus know where to cum to when I wants a reelly ellegant lunch, in a reelly ellegant room, and to be waited on by a reelly respectful Waiter," went away.

And now cums the strangest part of the hole affair, for presently in rushes our most gentlemanly Manager, and he says, says he, "Do you know, Robert, who that was as you've bin a waiting on?" "No, Sir!" says I. "Why it's no other than the young ——" But wild hosses shan't tear the name and title from me, as I was forbid to menshun it; but all I can say is, that if it was known when he was a coming next time, there wood be sich a crowd to see him as ewen our bewtifool Marble Pillow Room wouldn't hold.

Reported Accident to a Colonel and an Alderman.—Members of the Ancient Corporation will do well to open their Royal Academy Guide very cautiously, at least when they come to the Sculpture Department, as, if come upon suddenly, their nervous system would receive a severe shock from the following announcement:—"2023. Colonel W. H. Wilkin—bust." We are glad to say that the worthy and gallant Alderman has pulled himself together, and is uncommonly well. By the way, it is but fair to the sculptor to state that his name is—ahem!—"Walker".

Æsthetic Party (looking over Furnished House). "A—I'm afraid, my love, that this is the kind of Dining-room—A—in which one would feel that one ought to dine at Six o'Clock!!!"

Good Gentlemen both, you're on opposite tacks!

Well, your plans you are perfectly welcome to try on.

They talk of the patience of lambs, or park hacks;

They're not in it, my lads, with an elderly Lion.

A Lion, I mean, of the genuine breed,

And not a thin-skinned and upstart adolescent.

Dear me! did I let everybody succeed

In stirring me up, or in making things pleasant,

By smoothing me down in a flattering style,

I'd have, there's no doubt, a delectable time of it.

You think I look drowsy, and smile a fat smile;

Well, what if I do? Where's the very great crime of it?

A Lion, you know, is not all roar and ramp,

So, Stanley my hero, why worry and chivey?

Mere blarney won't blind me; I'm not of that stamp;

So don't hope to hypnotise me, good Caprivi.

Why, bless you, my boys, long before you were cubbed

I was charged, by your betters, with being too lazy;

But rivals have found, when outwitted or drubbed,

That a calm waiting game is not always so crazy.

In Indian jungles, American plains,

And far Eastern wilds, they have fancied me "bested,"

Because, when hot rivals were hungry for gains,

I kept my eyes open, and patiently rested.

A stolid and sleepy expression will steal

At times, I'm aware, o'er my leonine features;

But, when the time's ripe, my opponents may feel

I'm not the most easily humbugged of creatures.

In North as in South, in the East as the West,

Opponents have planted their paws down before me.

But where are they now, boys? J'y suis, j'y reste!

Staying power is the thing; so don't bully and bore me.

I hear you, my Stanley, I hear you and mark;

To snub you for patriot zeal were ungracious;

But—well, after all, on your Continent Dark

My footprints are plain, and my realm's pretty spacious.

I don't mean to say that a purblind content

My power should palsy, my policy dominate,

And Congos and Khartoums that pay cent. per cent.

Are tempting, but arrogant haste I abominate.

My "prancing proconsuls" not always are right,

Whose first and last word for old Leo is "collar!"

I'm not going to flare up like fury and fight

Every time someone else wins an acre or dollar.

But if you imagine I'm out of the hunt

Every time I take breath, you are vastly mistaken:

I know you're a brick, and like language that's blunt;

Well, Lions sleep lightly, and readily waken!

For you, friend Caprivi, your manners are nice,

Your style of caressing is verily charming;

How soothingly sweet is your placid advice,

Your mild deprecation is almost disarming;

Almost, but not quite, for 'tis true Teuton law

That unfailing defence is the root of the matter;

And Leo is fully aware tooth and claw

Must not be talked off e'en by friendlies who flatter.

Your prod, my good Stanley, Caprivi, your pat,

Are politic both; I've an eye upon each of you.

The lids may look lazy, but don't trust to that;

I watch, and I wait, and I weigh the 'cute speech of you.

I do not mind learning from both of your books,

But though you may think Leo given to slumber,

He may not be quite such a slug as he looks,

As rivals have found, dear boys, times out of number!

Amongst Cambridge cricketers Mr. Gosling and Mr. Henfrey may be trusted to avoid duck's eggs. Mr. Rowell prefers to bat well; and Mr. Leese wishes he had a freehold when he is at the wickets. With Woods, a Hill, a (Streat)field, a (Beres)ford and a (Cotte)rill, there's plenty of variety about Fenner's ground at present.

Poverty is commonly supposed to be a bar to all generosity and enjoyment of life. Perhaps this may be true of a certain class. But there is a kind of genteel and not unfashionable poverty with regard to which it is mainly false. A poor lady, for instance, who is afflicted with an overmastering charitable impulse, and is blessed with energy, will use this bar of poverty as a lever with which to move the bounty of her friends, in order that she herself may appear bountiful, and, as a rule, her efforts in this direction will be crowned with a success that would be phenomenal, if it were not so common. The history of her earlier years is easily written. Whilst still a child, she begins a collecting career, by being entrusted, on behalf of a church building fund, with a card divided into "bricks," each brick being valued at the price of half-a-crown. Her triumphs in inducing her relations and their friends to become purchasers of these minute and valueless squares of cardboard are great, and the consideration she acquires on all hands as a precocious charitable agent is very acceptable even to her childish mind.

Her profession having thus been determined, she devotes herself with an unflagging ardour to the task of diminishing the available assets of those with whom she may be brought in contact. Her parents, who are not overburdened with riches, look on at first with amusement, and afterwards with the dismay which any excess of zeal always arouses in the British breast. Their protests, however, fall upon deaf ears, and they adopt an attitude of severe neutrality, in the hope that years and a husband may bring wisdom to their daughter.

This does not save them from being made involuntary sharers in her charitable iniquities. Her father wakes one morning to find himself famous to the amount of one pound ten, contributed under the name of "A Cruel Parent," to the Amalgamated Society for the Reform of Rag-pickers, and his wife at the same time is made indignant by the discovery that she figures for twelve-and-sixpence, as "A Mother who ought to be Proud," in the balance-sheet of the United Charwomen's Home Reading Association. Further inquiry reveals the fact that the former sum resulted from the sale by the daughter to an advertising Old Clothes' Merchant of two of her father's suits, which, although they had seen service, he had not yet resolved to discard; and the result is the dismissal of the family butler, who had connived in the transaction. The twelve-and-sixpence had been formed gradually by the accumulation of stray coppers and postage-stamps, which her mother was accustomed to leave about on her writing-table, without the least intention that they should be devoted to charity. The parents expostulate in vain. The consciousness that she has diverted to objects, which she believes to be admirable, money that might have been unworthily spent, steels the heart of their daughter against their remonstrances, nor can she be induced to believe that, in thus taking upon herself to interpret or to correct the intentions of her parents, she has done wrong.

Matters, however, are thus brought to a crisis. Her home becomes unendurable to her, and she accepts the offer of marriage made by a subordinate, and not very highly paid official, in one of the Departments of the Civil Service. Her parents pronounce their blessing, and rejoice in an event which promises them an immunity from many annoyances.

The marriage duly takes place, but it is soon evident that the poor Lady Bountiful will not allow her change of condition to make any difference to the vigour and persistency of her charitable appeals. She continues the old firm and the old business under a new name, and takes advantage of her independence to enlarge immensely the field of her operations. No bazaar can be organised without her and as a stall-holder she is absolutely unrivalled. Missions, teas, treats, penny dinners, sea-side excursions, the building of halls, the endowment of a bishopric, the foundation of a flannel club, all depend upon her inexhaustible energy in begging. Nor is she satisfied with public institutions. Private applicants of all kinds gather about her. Destitute but undeserving widows, orphans who have brought the grey hairs of their parents to the grave, old soldiers and stranded foreigners batten upon her capacity for taking advantage of her friends. For it must be well understood that the restricted limits of her husband's means and his parsimony prevent her from contributing anything herself to her innumerable schemes except a lavish expenditure of pens and ink and paper with which to set forth her appeals. Yet in this she is a true altruist. For she knows and tells everybody how delightful and blessed it is to give, and accordingly in the purest spirit of self-denial she permits her friends to dispense the cash, whilst she herself is satisfied with the credit.

Like a mighty river, she receives the offerings of innumerable tributary streams, which lose their identity in hers, and are swept away under her name, to be finally merged in the great ocean of charitable effort. Who does not know, that it was mainly owing to her indefatigable efforts, that the new wing was added to the Disabled District Visitors' Refuge, and who has not seen at least one of the many subscription lists to which "per Mrs. So-and-So" invariably contributed the largest amount? Is it not also on record that at the reception which followed the public opening of this wing, when the collecting ladies advanced to deposit their collections at the feet of presiding Royalty, it was the Poor Lady Bountiful who brought the largest, the most beautifully embroidered and the fullest purse? It was felt on all hands, that "the dear Princess" had only done what an English Princess might properly be expected to do, when she afterwards, under the inspiration of the cunning Vicar, showered a few words of golden public praise into the palpitating bosom of the champion purse-bearer.

And thus her time is spent. When she is not organising a refuge she is setting on its legs a dinner fund, when she has exhausted the patience of her friends on behalf of her particular tame widow, she can always begin afresh with a poverty-stricken refugee, and if the delights of the ordinary subscription-card should ever pall, she can fly for relaxation to the seductive method of the snowball, which conceals under a cloak of geometrical progression and accuracy, the most comprehensive uncertainty in its results. One painful incident in her career must be chronicled. Fired by her example, but without her knowledge, a friend of hers from whom she is accustomed to solicit subscriptions, steps down to do battle on her own account in the charitable arena. And thus, when next the Poor Lady Bountiful makes an appeal in this quarter on behalf of a Siberian Count, whom she declares to be quite a gentleman in his own country, she is met by the declaration, that further relief is impossible, as her friend has a Bulgarian of her own to attend to. Thus there is an end of friendship, and both parties scatter dreadful insinuations as to the necessity for an audit of accounts. Eventually it happens that a rich and distant relation of her husband dies, and leaves him unexpectedly an income of several thousands a-year. Having thus lost all her poverty, she retires from the fitful fever of charitable life to the serene enjoyment of a substantial income, and awaits, with a fortitude that no collector is suffered to disturb, the approach of a non-subscribing and peaceful old age.

Hard Luck, by Arthur à Beckett, begins a trifle slow, but works up to an exciting climax, of which the secret is so profoundly kept, up till the very last moment, that not the most experienced in sensational plots would discover it. Capitally managed. It is one of the Arrowsmith Series, and a genuinely artistic shilling shocker.

A Black Business. By Hawley Smart. Uncommonly smart of him bringing it out just at this time, when the talk everywhere is about the Slave Trade, the struggle for Colonial life, Stanley, and the Very Darkest Africa. There's Black Business enough about. Smart chap Hawley.

The only thing I've to say against the Remarks of Bill Nye, in one volume, says the Baron, is the size of the book, which is as big as a family Bible. Nowadays, when busy men can only snatch a few seconds en route, the handy volume is the only really practicable form of literature. I'd rather have three small pocketable volumes of Bill Nye's essays and stories than this one cumbersome work, which, once on the shelf, runs a pretty good chance of being left there. The majority of Bill Nye's sayings are very amusing, and one of his short papers shows that the humorist can be pathetic on occasion without falling into mock sentiment. It is published by Neely, of New York, and, if reduced in bulk, the Remarks of Bill Nye ought to do very well here, even among those who, for want of familiarity with American slang, do not keenly appreciate American humour. The Baron does appreciate it when it is genuine American humour, but when the peculiar style is only copied by a journalistic 'arry, with whom the stupidest and most vulgar Yankeeisms pass for the highest wit, simply because they are Yankeeisms, then for this sort of imitation the Baron has no criticism sufficiently severe.

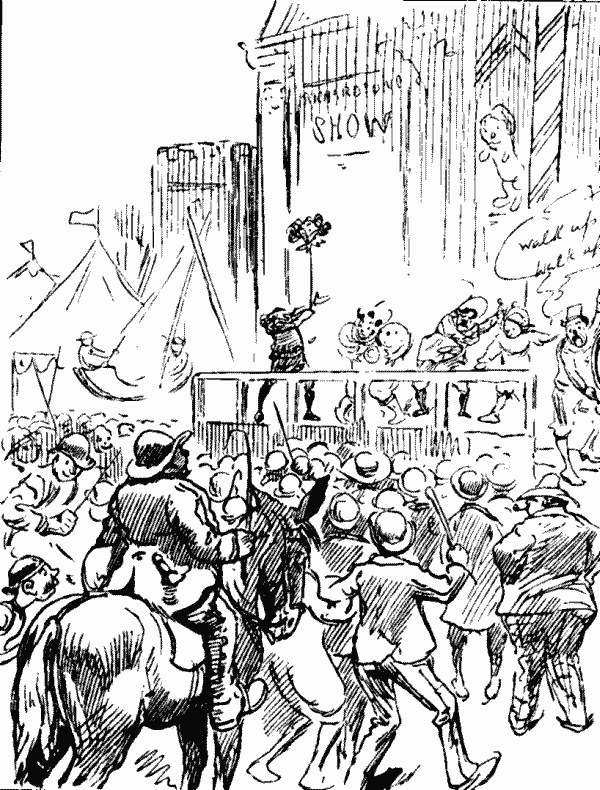

No. 216. "Walk up! Walk up! Just a goin' to begin'!"

[Probably from a contemporary wood engraving of Whitehall, 1649, which settles the question as to whether there was a "block" or not.]

Sir,—I have been about, according to your instructions, and I have come back with a mixed notion that somewhere in the dawn of history the Queen of Sheba, scantily dressed, and attended by her black Chamberlain, drove out on a four-horse parcel-post van to see an exhibition of paintings on china at Messrs. Howell and James's. It is perfectly true that in the course of my wanderings I had some champagne, but not a drop of chicken. Consequently, I have brought my critical faculty home with me entirely unimpaired. But to business.

Mr. E. J. Poynter has painted a noble picture of the meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, and Mr. T. McLean exhibits it at 7, Haymarket. I once saw a picture of this Queen on an ancient corner-cupboard; that was in early childhood, and the Queen of those days was a very Dutch Lady. Mr. Poynter's is quite unlike that one; in fact, she is extremely beautiful. But why is she overcome? Solomon might have been pardoned for blushing when he saw her, but he takes it quite as a matter of course. The black Chamberlain is evidently not a lord, otherwise he would have been more careful about his Queen's dress. There are harps, peacocks, golden lions, luscious fruits, monkeys, marble steps, and gorgeous pillars, to complete the picture. Curiously enough, the other ladies do not seem to care for the newly-arrived Queen. Bravo, Poynter! A great picture!

After this I hurried to the painted China Exhibition at Howell And James's; very delicate, very graceful, and very refined. "A Wild Corner" by G. Leonce, "Blue Tits" by Miss Salisbury—sure to make her Mark(is),—two landscapes by A. Fisher (who needs no rod) struck me particularly, but did not hurt me much. And so to the wilds of Finsbury (14, Castle Street) where Messrs. McNamara were exhibiting the Postal Vehicles to be used at the Penny Postage Jubilee Celebration. I've already ordered two four-horse parcel vans, three two-horse, and two one-horse mail-carts for my private use, and have told Messrs. M. to put them down to you, Sir. I couldn't resist it. They said it would be all right. Please make it so. I am told, that no females are employed in these vehicles. Another injustice. I should like to ride in a lovely red carriage for ever.

Yours,

There has been lately some racing at Kempton and various other places, as to which, I ought perhaps to say a few words. Not that I acknowledge a right in anyone to dictate to me how and when I shall notice matters connected with the turf. The Bedlamites who mouth and gibber about horses and their owners, as if they were in the constant habit of living on terms of familiar intimacy with the aristocracy, instead of being, as they probably are, the dumpling-headed parasites of touts and stable-boys, are entitled only to the contempt of every decent man who knows anything about what he professes to understand. At any rate, they have mine. My knowledge of the Kempton Course dates back at least fifty years. To be sure, it was not at that time a racecourse, but was mostly ploughed fields and thickets. But if the anserous and asinine mooncalves, whose high priest is Mr. Jeremy, suppose that that fact in any way weakens the authority with which I may claim to speak on the subject, I can only assure them, that they prove themselves fit inmates for the various asylums from which they ought never to have been withdrawn. I never thought much of Philomel. Ten years ago, I observed, with regard to this animal, "Philomel must be watched. There is no knowing what a course of podophyllin and ginger might not do. Failing that, I should feel inclined to say, buncombe." Mr. J. says, this was a different mare. What of that? In turf matters the name is everything, and I am therefore justified in citing this as one of the most extraordinary instances of prescience known to the turf world.

Megatherium, I notice, has many admirers. As a horizontal bar, or possibly as a clothes-line, he might have merits, but as a horse, I must confess, he has little to recommend him. When Loblolly Boy cantered home for the East End Weight-for-age Welter Handicap, I said that the son of Rattlesnake could make mince-meat of all his rivals. Since then he has made for his owner £5,000,000 in added money, at an initial expense of twopence halfpenny for saveloys and onions, a combination of which this splendid animal is particularly fond. Loblolly Boy was by Rowdy out of Hoyden, and his pedigree mounts up to Sallycomeup, Kissmequick, and Curate on Toast, whilst in the collateral line he can claim kinship with Artaxerxes and Devil's Dustpan. In the Margate Open Sweepstakes, he ran second to Daddy, when the sea was as smooth as an old halfcrown. If there had been wind enough to blow out a wooden match, he must have won in a common hand-gallop.

Maud (on crossing the boundary between Hertfordshire and the neighbouring county, in which the Muzzling Order does not prevail). "That's right! Off with his Muzzle! So much for Buckingham!"

House of Commons, Monday, May 12.—"If a shutter be closed in the daytime," said Old Morality, a little abruptly, as we walked down to House to-day, "the stream of light piercing through the crevice seems to be in constant agitation. Why is this?"

Hadn't slightest idea. Suggested Right Hon. Gentleman had better give notice of question.

"I can tell you why," he proceeded, with unwonted perturbation. "Because little motes and particles of dust, thrown into agitation by the convective currents of the air, are made visible by the strong beam of light thrown into the room through the crevice of the shutter. That's just the way with us, dear Toby; a is the hatred of Government by the Opposition, the strong desire to take our places; b is the convective currents of air which agitate the political atmosphere; c is the Compensation Bill, the strong beam of light which, thrown into House through crevice opened by Jokim, makes the whole thing clear. Don't know whether I am; but if you reflect on the situation, you'll find there is much in what I say. We were going along moderately well. Irish Land Bill, of course, a rock ahead; everyone takes that into account. Suddenly Jokim, spoiling for a fight, goes and invents this Compensation Bill, quietly hands it over to Ritchie to work through, and all the greasy compound is in the devouring element. Seems a pity we could not leave the tolerably satisfactory undisturbed. Now we're in for it. Meetings out-of-doors; opposition in-doors; prospect of getting on with ordinary work of Session receding into distance."

Good deal of truth in what Old Morality says. House crowded to-night; full of seething excitement. Ritchie moved Second Reading of Compensation Bill; Caine moved Amendment, eliminating principle of compensation. Capital speech; would have been better if it had been half an hour shorter. Between them, Ritchie and Caine occupied nearly three hours of sitting, leaving five hours for the remaining 668 Members.

"This is not debate," protested Shaw-Lefevre, sternly! "it is preaching; why cannot a man be concise? Concision, if I may coin a word, is the soul of argument. My old friend Dizzy used to say to me, 'Shaw, what I admire about Lefevre is his terseness. If you want a man to say in twenty minutes everything that, from his point of view, is to be spoken on a given subject, Shaw-Lefevre is the man.' That was, perhaps, a too flattering view to take; but there's something in it, and it makes me, perhaps naturally, impatient of a man who wanders round his subject for an hour and a half."

Business done.—Debate on Compensation opened.

Tuesday.—"Heard something about good man struggling with adversity," said Member for Sark, looking at Rathbone. "Nothing to goody goody man struggling with manuscript of his speech."

Rathbone certainly a melancholy spectacle. Evidently had spent his nights and days in preparation of speech on Compensation Bill; brought it down in large quarto notes. Old Morality glanced across House with sudden access of interest; thought it was a copy-book; Speech evidently highly prized at rehearsals in family circle.

"I think," said Rathbone, complacently, "before I sit down I shall show you that the view I take is correct."[Pg 252]

This remark interjected early in speech; proved rather a favourite. Whenever Rathbone got more than usually muddled, looked round nervously at empty Benches, nodded confidentially to Mace, and remarked, "Before I sit down I think I shall show you——" What it was he meant to show, no one quite certain. Elliot Lees, who followed, assumed with reckless light-heartedness of youth, that he meant to show before he sat down, that the more public-houses licensed, the less drunkenness.

"That," said Rathbone, with unaccustomed flash of intelligent speech, "was exactly the reverse of what I undertook to show the House."

Would have gone on pretty well only for (1) the Accountant, and (2) Sinclair. Whatever it was Rathbone was going to show before he sat down, he had fortified himself in his position by opinion of a sworn Accountant. Conversations with this Accountant set forth at length. Rathbone appears to have been kept by the Accountant in state of constant surprise. "Let's take two places in the country," he said, in one of the more lucid passages. "Well, there are only 360 public-houses in Leeds. Sheffield has 400 public-houses in proportion to population, whereas Bradford hasn't 160. Well, I was so much struck with this, that I wanted to know whether there were any reasons for it. So I applied to the Accountant—without telling him my object—which really was," he added, nodding quite briskly at the Mace, "to know whether there was more drunkenness in Leeds or Sheffield. He said at once, that Leeds was the most. Then I said to the Accountant 'I don't care about your individual cases, let's take the average. Let's take Birmingham.'"

Afterwards Blackburn and Stockport were "taken"—"As if they were goes of gin," said the Member for Sark; Rathbone turning over papers, which appeared to have got upside down, recited heaps of figures. These struck him the more he studied them. Anonymous Accountant seemed to have brought him completely under a spell. His highly respectable appearance, his evident earnestness, his accumulated mass of figures, his engagement of the Accountant, the tone of his voice, his general attitude, all conveyed impression that he was really saying something intelligible and useful. The few Members present honestly endeavoured to follow him; might have got a clue only for Sinclair.

At end of first half-hour Rathbone began to show signs of distress. Sinclair thought he was signalling for water; prepared to go for glass; something wrong; Rathbone violently agitated; nodding and winking and pointing to recess under bench before him. House now really excited. Began to think that perhaps the Accountant was hidden down there. If he could be only got up, might explain matters. Sinclair sharing general agitation, dived under seat; reappeared attempting to secrete small medicine bottle, apparently containing milk-punch; drew cork with difficulty; poured out dose, handed it to Rathbone. Rathbone gulped it down; smacked his lips; much refreshed; evidently good for another hour.

"I said to the Accountant," he continued, "if the Magistrates of Sheffield had indiced these lorcences—I mean endorsed those licences——."

Off again, wading with the Accountant knee-deep in figures from Leeds to Sheffield, back to Birmingham, across to Liverpool, on to York, with occasional sips of milk-punch. A wonderful performance that held in breathless attention few Members present to hear it.

"It is magnificent," said the Member for Sark; "but it isn't clear."

Business done.—Rathbone's great speech on the Licensing Question.

Wednesday.—Quite lively for Wednesday afternoon. At outset, apparently nothing particular in wind. Irish Members had first three places on Agenda, but that nothing unusual. Prospect was, that Debate on their first Bill, appropriating Irish Church Fund to provide Dwellings for Agricultural Labourers, would occupy whole of Sitting; be divided on just before half-past five. To make sure, Akers-Douglas issued Whip to Ministerialists, urging them to be in their places as early as four.

"Never know what the Bhoys will do," he said, sagely. "Like to be on the safe side. Division at five, so be here at four."

The Bhoys came down in great force at one o'clock; only a score or so of Ministerialists visible. Fox rose to move Second Reading of Bill. Good for an hour if necessary. Long John O'Connor, that Eiffel Tower of patriotism, ready to Second Motion, in a discourse of ninety minutes.

"May as well make an afternoon of it," he says, gazing round the expectant but empty Benches opposite.

Fox just started, when happy thought struck Irish Members. If they divided at once, before Ministerial majority arrived, could carry Second Reading; so Brer Fox doubled, and in ten minutes got back home. Long John folded himself up, till casual passer-by might have mistaken him for Picton. Conservatives, not ready for this manœuvre, dumfounded. Division imminent; only thing to be done was to make speeches till four o'clock and majority arrived. Everybody available pressed into service. Charles Lewis, coming up breathless, declared that "promoters of Bill, wished by a side-stab in the wind of the Government"—he meant by a side-wind—"to stab the Measure on the same subject the Government had brought forward."

That was better; though how you stab by a side-wind not explained. Prince Arthur threw himself languidly into fray. Talked up to quarter past three; majority beginning to trickle in, T. W. Russell moved Adjournment of Debate. Defeated by 94 votes against 68. Irish Members evidently in majority of 26. Prince Arthur, with eye nervously watching door, wished that night or Blucher would come. Neither arriving, stepped aside, letting Irish Members carry their Bill; which they did, amid tumultuous cheering.

"It's of no consequence, I assure you," Prince Arthur said, quoting Mr. Toots when he inadvertently sat down on Florence Dombey's best bonnet. "They may carry their Bill, but we'll take the money."

Business done.—Irish Members out-manœuvre Government.

Friday.—Second Reading of Compensation Bill carried at early hour this morning, after dull debate. Morning Sitting to-day for Supply. Duller than ever. Dullest of all, Jokim on Treasury Bench in charge of Estimates.

"Yes, Toby," he said, in reply to sympathetic greeting, "I am a little hipped; situation growing too heavy for me. Patriotism all very well; public spirit desirable; self-abnegation, as Old Morality says, is the seed of virtue. But you may carry spirit of self-sacrifice too far. Read my speech at dinner to Hartington, of course? Put it in the right light, don't you think? We Dissentient Liberals, as they call us, are the Paschal Lambs of politics; except that, instead of being offered up as sacrifice, we offer up ourselves. Still there are degrees. Hartington given up something; Chamberlain chucked himself away; James might have been on the Woolsack. But think of me, dear Toby, and all I've sacrificed. Four years ago a private Member, adrift from my Party; no chance of reinstatement; not even sure of a seat. Now Chancellor of the Exchequer, with £5000 a-year, and a pick of safe seats. Too much to expect of me, Toby; sometimes more than I can bear;" and Jokim hid his face in his copy of the Orders of the Day, whilst Theodore Fry looking on, was dissolved in tears.

Business done.—Supply.

Complaints are often made as to the non-appreciation of jokes by those to whom they are addressed. A Correspondent sends us on this subject the following interesting remarks:—"I have made on an average ten jokes a day for the last six years. Being in possession of a large independent income, I could have afforded to make more, but I think ten a day a reasonable number. I find that, as a rule, the wealthy and highly-placed have absolutely no appreciation of humour. The necessitous, however, show a keen taste for it. The other day a gentleman, whom I had only seen once, asked me for the loan of a sovereign. I immediately made six jokes running, and was rewarded by six successive peals of laughter. I then informed him I had no money with me, and left him chuckling to himself something about an Eastern coin of small value, called, I believe, a dam."

Narrow Escape of an R.A.!—Everyone knows that a Critic is one, who would, professionally, roast and cut up his own father; but that some Critics go beyond this, may be gathered from the fact of the Art-Critic of the Observer, in one of his recent reviews of the Academy, having thus expressed himself:—

"Mr. Poynter's flesh is never quite to our liking,"——

Heavens! What a dainty cannibal is this Critic! But how lucky for Mr. Poynter.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.