Title: "And they thought we wouldn't fight"

Author: Floyd Phillips Gibbons

Release date: January 26, 2010 [eBook #31086]

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/31086

Credits: Produced by Christine Aldridge, Suzanne Shell and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

1. Minor print errors corrected. Details at the end of this text.

2. All dialect spelling has been retained.

Copyright, 1918,

By George H. Doran Company

Printed in the United States of America

FLOYD GIBBONS

FLOYD GIBBONS

Personal.

France, August 17, 1918.

Mr. Floyd Gibbons,

Care Chicago Tribune,

420 Sue Saint-Honore,

Paris.

Dear Mr. Gibbons:

At this time, when you are returning to America, I wish to express to you my appreciation of the cordial cooperation and assistance you have always given us in your important work as correspondent of the Chicago Tribune in France. I also wish to congratulate you on the honor which the French government has done you in giving you the Croix de Guerre, which is but a just reward for the consistent devotion to your duty and personal bravery that you have exhibited.

My personal regrets that you are leaving us at this time are lessened by the knowledge of the great opportunity you will have of giving to our people in America a true picture of the work of the American soldier in France and of impressing on them the necessity of carrying on this work to the end, which can be accomplished only by victory for the Allied arms. You have a great opportunity, and I am confident that you will grasp it, as you have grasped your past opportunities, with success. You have always played the game squarely and with courage, and I wish to thank you.

Sincerely yours,

John J. Pershing.

G. Q. G. A. le July 28, 1918.

Commandement en Chef

des Armées Allies

Le Général

Monsieur,

I understand that you are going to the United States to give lectures on what you have seen on the French front.

No one is more qualified than you to do this, after your brilliant conduct in the Bois de Belleau.

The American Army has proved itself to be magnificent in spirit, in gallantry and in vigor; it has contributed largely to our successes. If you can thus be the echo of my opinion I am sure you will serve a good purpose.

Very sincerely yours,

(Signed) F. Foch.

Monsieur Floyd Gibbons,

War Correspondent of the Chicago Tribune.

G.Q.G.A. Le 28 Juillet 1918.

Commandement en Chef

des Armies Allies

Le Général

Monsieur,

Je sais que vous allez donner des conférences aux Etats-Unis pour raconter ce que vous avez vu sur le front français.

Personne n'est plus qualifié que vous pour le faire, après votre brillante conduite au Bois BELLEAU.

L'Armée Américaine se montre magnifique de sentiments, de valeur et d'entrain, elle a contribué pour une large part à nos succès. Si vous pouvez être l'écho de mon opinion, je n'y verrai qu'avantage.

Croyez, Monsieur, à mes meilleurs sentiments.

F. Foch

Monsieur FLOYD GIBBONS

Correspondant de Guerre du CHICAGO TRIBUNE.

GRAND QUARTIER GÉNÉRAL

DES ARMÉES DU NORD ET DU NORD EST

ETAT-MAJOR

BUREAU DU PERSONNEL

(Decorations)

Order No. 8809 D

The General Commander-in-Chief Cites for the Croix de Guerre

M. Floyd Gibbons, War Correspondent of the Chicago Tribune:

"Has time after time given proof of his courage and bravery by going to the most exposed posts to gather information. On June 5, 1918, while accompanying a regiment of marines who were attacking a wood, he was severely wounded by three machine gun bullets in going to the rescue of an American officer wounded near him—demonstrating, by this action, the most noble devotion. When, a few hours later, he was lifted and transported to the dressing station, he begged not to be cared for until the wounded who had arrived before him had been attended to."

General Headquarters, August 2, 1918

The General Commander-in-Chief

(Signed) Petain

GRAND QUARTIER GENERAL

DES ARMÉES DU NORD ET DU NORD-EST

ETAT-MAJOR

BUREAU DU PERSONNEL

(Décorations)

ORDRE No 8809 D

Le Général Commandant en Chef Cite à l'Ordre de l'Armée:

M. FLOYD GIBBONS, Correspondant de Guerre du Chicago Tribune:

"A donné à maintes reprises des preuves de courage et de bravoure, en allant recueillir des informations aux postes les plus exposés. Le 5 Juin 1918, accompagnant un régiment de Fusiliers marins qui attaquait un bois, a été très grièvement atteint de trois balles de mitrailleuses en se portant au secours d'un officier américain blessé à ses côtés, faisant ainsi preuve, en cette circonstance, du plus beau dévouement. Relevé plusieurs heures après et transporté au poste de secours, a demandé à ne pas être soigné avant les blessés arrivés avant lui."

Au Grand Quartier Général, le 2 Aout 1918.

LE GÉNÉRAL COMMANDANT EN CHEF.

Marshal Foch, the commander of eleven million bayonets, has written that no man is more qualified than Gibbons to tell the true story of the Western Front. General Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces, has said that it was Gibbons' great opportunity to give the people in America a life-like picture of the work of the American soldier in France.

The key to the book is the man.

Back in the red days on the Rio Grande, word came from Pancho Villa that any "Gringos" found in Mexico would be killed on sight. The American people were interested in the Revolution at the border. Gibbons went into the Mexican hills alone and called Villa's bluff. He did more. He fitted out a box car, attached it to the revolutionary bandits' train and was in the thick of three of Villa's biggest battles. Gibbons brought out of Mexico the first authoritative information on the Mexican situation. The following year the War Department accredited him to General Pershing's punitive expedition and he rode with the flying column led by General Pershing when it crossed the border.

In 1917, the then Imperial German Government announced to the world that on and after February 1st its submarines would sink without warning any ship that ventured to enter a zone it had drawn in the waters of the North Atlantic.

Gibbons sensed the meaning of this impudent challenge.[xiv] He saw ahead the overt act that was bound to come and be the cause of the United States entering the war. In these days the cry of "Preparedness" was echoing the land. England had paid dearly for her lack of preparedness. The inefficient volunteer system had cost her priceless blood. The Chicago Tribune sought the most available newspaper man to send to London and write the story of England's costly mistakes for the profit of the American people. Gibbons was picked for the mission and arrangement was made for him to travel on the steamer by which the discredited Von Bernstorff was to return to Germany. The ship's safe conduct was guaranteed. Gibbons did not like this feature of the trip. He wanted to ride the seas in a ship without guarantees. His mind was on the overt act. He wanted to be on the job when it happened. He cancelled the passage provided for him on the Von Bernstorff ship and took passage on the largest liner in port, a ship large enough to be readily seen through a submarine periscope and important enough to attract the special attention of the German Admiralty. He sailed on the Laconia, an eighteen thousand ton Cunarder.

On the night of February 27, 1917, when the Laconia was two hundred miles off the coast of Ireland, the Gibbons' "hunch" was fulfilled. The Laconia was torpedoed and suck. After a perilous night in a small boat on the open sea, Gibbons was rescued and brought into Queenstown. He opened the cables and flashed to America the most powerful call to arms to the American people. It shook the country. It was the testimony of an eye witness and it convinced the Imperial German Government, beyond all reasonable doubt, of the wilful and malicious murder of American citizens. The Gibbons story furnished the proof of the overt act and it was[xv] unofficially admitted at Washington that it was the determining factor in sending America into the war one month later.

Gibbons greeted Pershing on the latter's landing in Liverpool. He accompanied the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces across the Channel and was at his side when he put foot on French soil. He was one of the two American correspondents to march with the first American troops that entered the trenches on the Western front. He was with the first American troops to cross the German frontier. He was with the artillery battalion that fired the first American shell into Germany.

On June 6th, 1918, Gibbons went "over the top" with the first waves in the great battle of the Bois de Belleau. Gibbons was with Major John Berry, who, while leading the charge, fell wounded. Gibbons saw him fall. Through the hail of lead from a thousand spitting machine guns, he rushed to the assistance of the wounded Major. A German machine gun bullet shot away part of his left shoulder, but this did not stop Gibbons. Another bullet smashed through his arm, but still Gibbons kept on. A third bullet got him. It tore out his left eye and made a compound fracture of the skull. For three hours he lay conscious on the open field in the Bois de Belleau with a murderous machine gun fire playing a few inches over his head until under cover of darkness he was able to crawl off the field. For his gallant conduct he received a citation from General Petain, Commander-in-Chief of the French Armies, and the French Government awarded him the Croix de Guerre with the Palm.

On July 5th, he was out of the hospital and back at the front, covering the first advance of the Americans with the British forces before Amiens. On July 18th he[xvi] was the only correspondent with the American troops when they executed the history-making drive against the German armies in the Château-Thierry salient—the beginning of the German end. He rode with the first detachment of American troops that entered Château-Thierry upon the heels of the retreating Germans.

Floyd Gibbons was the first to sound the alarm of the danger of the German peace offensive. Six weeks before the drive for a negotiated peace was made by the German Government against the home flank in America, Gibbons told that it was on the way. He crossed the Atlantic with his crippled arm in a sling and his head bandaged, to spend his convalescence warning American audiences against what he called the "Crooked Kamerad Cry."

Gibbons has lived the war, he has been a part of it. "And They Thought We Wouldn't Fight" is the voice of our men in France.

Frank Comerford.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | THE SINKING OF THE Laconia | 17 |

| II | PERSHING'S ARRIVAL IN EUROPE | 43 |

| III | THE LANDING OF THE FIRST AMERICAN CONTINGENT IN FRANCE | 61 |

| IV | THROUGH THE SCHOOL OF WAR | 78 |

| V | MAKING THE MEN WHO MAN THE GUNS | 96 |

| VI | "FRONTWARD HO!" | 117 |

| VII | INTO THE LINE—THE FIRST AMERICAN SHOT IN THE WAR | 134 |

| VIII | THE FIRST AMERICAN SECTOR | 158 |

| IX | THE NIGHT OUR GUNS CUT LOOSE | 182 |

| X | INTO PICARDY TO MEET THE GERMAN PUSH | 199 |

| XI | UNDER FIRE | 217 |

| XII | BEFORE CANTIGNY | 235 |

| XIII | THE RUSH OF THE RAIDERS—"ZERO AT 2 A. M." | 251 |

| XIV | ON LEAVE IN PARIS | 266 |

| XV | CHÂTEAU-THIERRY AND THE BOIS DE BELLEAU | 283 |

| XVI | WOUNDED—HOW IT FEELS TO BE SHOT | 305 |

| XVII | "GOOD MORNING, NURSE" | 323 |

| XVIII | GROANS, LAUGHS AND SOBS IN THE HOSPITAL | 338 |

| XIX | "JULY 18TH"—THE TURN OF THE TIDE | 354 |

| XX | THE DAWN OF VICTORY | 376 |

| APPENDIX | ||

| PERSONNEL OF THE AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCES IN FRANCE | 399 |

| FLOYD GIBBONS | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

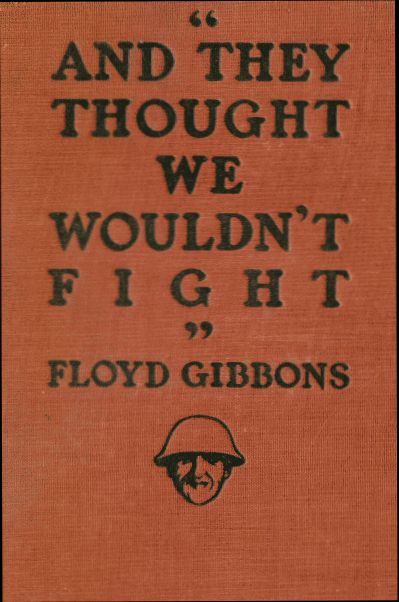

| THE ARRIVAL IN LONDON, SHOWING GENERAL PERSHING, MR. PAGE, FIELD MARSHAL VISCOUNT FRENCH, LORD DERBY, AND ADMIRAL SIMS | 50 |

| GENERAL PERSHING BOWING TO THE CROWD IN PARIS | 50 |

| THE FIRST AMERICAN FOOT ON FRENCH SOIL | 66 |

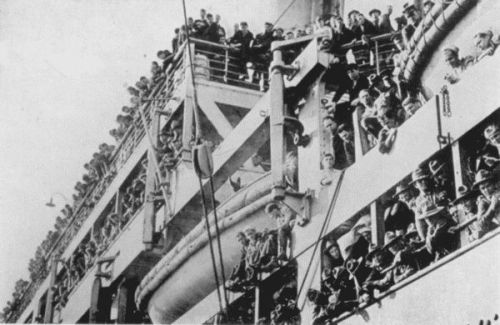

| THE FIRST GLIMPSE OF FRANCE | 66 |

| CAPT. CHEVALIER, OF THE FRENCH ARMY, INSTRUCTING AMERICAN OFFICERS IN THE USE OF THE ONE POUNDER | 122 |

| IN THE COURSE OF ITS PROGRESS TO THE VALLEY OF THE VESLE THIS 155 MM. GUN AND OTHERS OF ITS KIND WERE EDUCATING THE BOCHE TO RESPECT AMERICA. THE TRACTOR HAULS IT ALONG STEADILY AND SLOWLY, LIKE A STEAM ROLLER | 122 |

| GRAVE OF FIRST AMERICANS KILLED IN FRANCE. TRANSLATION: HERE LIE THE FIRST SOLDIERS OF THE GREAT REPUBLIC OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, FALLEN ON FRENCH SOIL FOR JUSTICE AND FOR LIBERTY, NOVEMBER 3RD, 1918 | 170 |

| FIRST OF THE GREAT FRANCO-AMERICAN COUNTER-OFFENSIVE AT CHÂTEAU-THIERRY. THE FRENCH BABY TANKS, KNOWN AS CHARS D'ASSAUTS, ENTERING THE WOOD OF VILLERS-COTTERETS, SOUTHWEST OF SOISSONS | 226 |

| YANKS AND POILUS VIEWING THE CITY OF CHÂTEAU-THIERRY WHERE IN THE MIDDLE OF JULY THE YANKS TURNED THE TIDE OF BATTLE AGAINST THE HUNS | 226 |

| MARINES MARCHING DOWN THE AVENUE PRESIDENT WILSON ON THE FOURTH OF JULY IN PARIS | 274 |

| BRIDGE CROSSING MARNE RIVER IN CHÂTEAU-THIERRY DESTROYED BY GERMANS IN THEIR RETREAT FROM TOWN | 274 |

| HELMET WORN BY FLOYD GIBBONS WHEN WOUNDED, SHOWING DAMAGE CAUSED BY SHRAPNEL | 314 |

| THE NEWS FROM THE STATES | 346 |

| SMILING WOUNDED AMERICAN SOLDIERS | 346 |

(Photographs Copyright by Committee on Public Information.)

Between America and the firing line, there are three thousand miles of submarine infested water. Every American soldier, before encountering the dangers of the battle-front, must first overcome the dangers of the deep.

Geographically, America is almost four thousand miles from the war zone, but in fact every American soldier bound for France entered the war zone one hour out of New York harbour. Germany made an Ally out of the dark depths of the Atlantic.

That three-thousand-mile passage represented greater possibilities for the destruction of the United States overseas forces than any strategical operation that Germany's able military leaders could direct in the field.

Germany made use of that three thousand miles of water, just as she developed the use of barbed wire entanglements along the front. Infantry advancing across No Man's Land were held helpless before the enemy's fire by barbed wire entanglements. Germany, with her submarine policy of ruthlessness, changed the Atlantic Ocean into another No Man's Land across which every American soldier had to pass at the mercy of the enemy before he could arrive at the actual battle-front.

This was the peril of the troop ship. This was the tremendous advantage which the enemy held over our armies even before they reached the field. This was the unprecedented condition which the United States and[18] Allied navies had to cope with in the great undertaking of transporting our forces overseas.

Any one who has crossed the ocean, even in the normal times before shark-like Kultur skulked beneath the water, has experienced the feeling of human helplessness that comes in mid-ocean when one considers the comparative frailty of such man-made devices as even the most modern turbine liners, with the enormous power of the wilderness of water over which one sails.

In such times one realises that safety rests, first upon the kindliness of the elements; secondly, upon the skill and watchfulness of those directing the voyage, and thirdly, upon the dependability of such human-made things as engines, propellers, steel plates, bolts and rivets.

But add to the possibilities of a failure or a misalliance of any or all of the above functions, the greater danger of a diabolical human, yet inhuman, interference, directed against the seafarer with the purpose and intention of his destruction. This last represents the greatest odds against those who go to sea during the years of the great war.

A sinking at sea is a nightmare. I have been through one. I have been on a ship torpedoed in mid-ocean. I have stood on the slanting decks of a doomed liner; I have listened to the lowering of the life-boats, heard the hiss of escaping steam and the roar of ascending rockets as they tore lurid rents in the black sky and cast their red glare o'er the roaring sea.

I have spent a night in an open boat on the tossing swells. I have been through, in reality, the mad dream of drifting and darkness and bailing and pulling on the oars and straining aching eyes toward an empty, meaningless horizon in search of help. I shall try to tell you how it feels.[19]

I had been assigned by The Chicago Tribune to go to London as their correspondent. Almost the same day I received that assignment, the "Imperial" Government of Germany had invoked its ruthless submarine policy, had drawn a blockade zone about the waters of the British Isles and the coasts of France, and had announced to the world that its U-boats would sink without warning any ship, of any kind, under any flag, that tried to sail the waters that Germany declared prohibitory.

In consideration of my personal safety and, possibly, of my future usefulness, the Tribune was desirous of arranging for me a safe passage across the Atlantic. Such an opportunity presented itself in the ordered return of the disgraced and discredited German Ambassador to the United States, Count von Bernstorff.

Under the rules of International courtesy, a ship had been provided for the use of von Bernstorff and his diplomatic staff. That ship was to sail under absolute guarantees of safe conduct from all of the nations at war with Germany and, of course, it would also have been safe from attack by German submarines. That ship was the Frederick VIII. At considerable expense the Tribune managed to obtain for me a cabin passage on that ship.

I can't say that I was over-impressed with the prospect of travel in such company. I disliked the thought that I, an American citizen, with rights as such to sail the sea, should have to resort to subterfuge and scheming to enjoy those rights. There arose in me a feeling of challenge against Germany's order which forbade American ships to sail the ocean. I cancelled my sailing on the Frederick VIII.

In New York, I sought passage on the first American ship sailing for England. I made the rounds of the steamship offices and learned that the Cunard liner Laconia[20] was the first available boat and was about to sail. She carried a large cargo of munitions and other materials of war. I booked passage aboard her. It was on Saturday, February 17th, 1917, that we steamed away from the dock at New York and moved slowly down the East River. We were bound for Liverpool, England. My cabin accommodations were good. The Laconia was listed at 18,000 tons and was one of the largest Cunarders in the Atlantic service. The next morning we were out of sight of land.

Sailors were stationed along the decks of the ship and in the look-outs at the mast heads. They maintained a watch over the surface of the sea in all directions. On the stern of the ship, there was mounted a six-inch cannon and a crew of gunners stood by it night and day.

Submarines had been recently reported in the waters through which we were sailing, but we saw none of them and apparently they saw none of us. They had sunk many ships, but all of the sinkings had been in the day time. Consequently, there was a feeling of greater safety at night. The Laconia sailed on a constantly zig-zagging course. All of our life-boats were swinging out over the side of the ship, so that if we were hit they could be lowered in a hurry. Every other day the passengers and the crew would be called up on the decks to stand by the life-boats that had been assigned to them.

The officers of the ship instructed us in the life-boat drill. They showed us how to strap the life-preservers about our bodies; they showed us how to seat ourselves in the life-boats; they showed us a small keg of water and some tin cans of biscuits, a lantern and some flares that were stored in the boat, and so we sailed along day after day without meeting any danger. At night, all of[21] the lights were put out and the ship slipped along through the darkness.

On Sunday, after we had been sailing for eight days, we entered the zone that had been prohibited by the Kaiser. We sailed into it full steam ahead and nothing happened. That day was February the twenty-fifth. In the afternoon, I was seated in the lounge with two friends. One was an American whose name was Kirby; the other was a Canadian and his name was Dugan. The latter was an aviator in the British army. In fights with German aeroplanes high over the Western Front he had been wounded and brought down twice and the army had sent him to his home in Canada to get well. He was returning once more to the battle front "to stop another bullet," as he said.

As we talked, I passed around my cigarette case and Dugan held a lighted match while the three of us lighted our cigarettes from it. As Dugan blew out the match and placed the burnt end in an ash tray, he laughed and said,

"They say it is bad luck to light three cigarettes with the same match, but I think it is good luck for me. I used to do it frequently with my flying partners in France and four of them have been killed, but I am still alive."

"That makes it all right for you," said Kirby, "but it makes it look bad for Gibbons and myself. But nothing is going to happen. I don't believe in superstitions."

That night after dinner Dugan and I took a brisk walk around the darkened promenade deck of the Laconia. The night was very dark, a stiff wind was blowing and the Laconia was rolling slightly in the trough of the waves. Wet from spray, we returned within and in one of the corridors met the Captain of the ship. I told him[22] that I would like very much to have a look at his chart and learn our exact location on the ocean.

He looked at me and laughed because that was a very secret matter. But he replied:

"Oh, you would, would you?" and his voice carried that particular British intonation that seemed to say, "Well it is jolly well none of your business."

Then I asked him when he thought we would land in Liverpool.

"I really don't know," said the ship's commander, and then, with a wink, he added, "but my steward told me that we would get in Tuesday evening."

Kirby and I went to the smoke room on the boat deck well to the stern of the ship. We joined a circle of Britishers who were seated in front of a coal fire in an open hearth. Nearly every one in the lighted smoke room was playing cards, so that the conversation was practically confined to the mentioning of bids and the orders of drinks from the stewards.

"What do you think are our chances of being torpedoed?" was the question I put before the circle in front of the fireplace.

The deliberative Mr. Henry Chetham, a London solicitor, was the first to answer.

"Well," he drawled, "I should say about four thousand to one."

Lucien J. Jerome of the British Diplomatic Service, returning with an Ecuadorian valet from South America, advanced his opinion.

I was much impressed with his opinion because the speaker himself had impressed me deeply. He was the best monocle juggler I had ever met. In his right eye he carried a monocle without a rim and without a ribbon[23] or thread to save it, should it ever have fallen from his eye.

Repeatedly during the trip, I had seen Mr. Jerome standing on the hurrideck of the Laconia facing the wind but holding the glass disk in his eye with a muscular grip that must have been vise-like. I had even followed him around the deck several times in a desire to be present when the monocle blew out, but the British diplomatist never for once lost his grip on it. I had come to the opinion that the piece of glass was fixed to his eye and that he slept with it. After the fashion of the British Diplomatic Service, he expressed his opinion most affirmatively.

"Nonsense," he said with reference to Mr. Chetham's estimate. "Utter nonsense. Considering the zone that we are in and the class of the ship, I should put the chances down at two hundred and fifty to one that we don't meet a 'sub.'"

At that minute the torpedo hit us.

Have you ever stood on the deck of a ferry boat as it arrived in the slip? And have you ever experienced the slight sideward shove when the boat rubs against the piling and comes to a stop? That was the unmistakable lurch we felt, but no one expects to run into pilings in mid-ocean, so every one knew what it was.

At the same time, there came a muffled noise—not extremely loud nor yet very sharp—just a noise like the slamming of some large oaken door a good distance away. Realising that we had been torpedoed, my imagination was rather disappointed at the slightness of the shock and the meekness of the report. One or two chairs tipped over, a few glasses crashed from table to floor and in an instant every man in the room was on his feet.

"We're hit," shouted Mr. Chetham.[24]

"That's what we've been waiting for," said Mr. Jerome.

"What a lousy torpedo!" said Mr. Kirby. "It must have been a fizzer."

I looked at my watch; it was 10:30.

Five sharp blasts sounded on the Laconia's whistle. Since that night, I have often marvelled at the quick coordination of mind and hand that belonged to the man on the bridge who pulled that whistle rope. Those five blasts constituted the signal to abandon the ship. Every one recognised them.

We walked hurriedly down the corridor leading from the smoke room in the stern to the lounge which was amidships. We moved fast but there was no crowding and no panic. Passing the open door of the gymnasium, I became aware of the list of the vessel. The floor of the gymnasium slanted down on the starboard side and a medicine ball and dozens of dumb bells and Indian clubs were rolling in that direction.

We entered the lounge—a large drawing room furnished with green upholstered chairs and divans and small tables on which the after-dinner liqueur glasses still rested. In one corner was a grand piano with the top elevated. In the centre of the slanting floor of the saloon was a cabinet Victrola and from its mahogany bowels there poured the last and dying strains of "Poor Butterfly."

The women and several men who had been in the lounge were hurriedly leaving by the forward door as we entered. We followed them through. The twin winding stairs leading below decks by the forward hatch were dark and I brought into play a pocket flashlight shaped like a fountain pen. I had purchased it before[25] sailing in view of such an emergency and I had always carried it fastened with a clip in an upper vest pocket.

My stateroom was B 19 on the promenade deck, one deck below the deck on which was located the smoke room, the lounge and the life-boats. The corridor was dimly lighted and the floor had a more perceptible slant as I darted into my stateroom, which was on the starboard and sinking side of the ship. I hurriedly put on a light non-sink garment constructed like a vest, which I had come provided with, and then donned an overcoat.

Responding to the list of the ship, the wardrobe door swung open and crashed against the wall. My typewriter slid off the dressing table and a shower of toilet articles pitched from their places on the washstand. I grabbed the ship's life-preserver in my left hand and, with the flashlight in my right hand, started up the hatchway to the upper deck.

In the darkness of the boat deck hatchway, the rays of my flashlight revealed the chief steward opening the door of a switch closet in the panel wall. He pushed on a number of switches and instantly the decks of the Laconia became bright. From sudden darkness, the exterior of the ship burst into a blaze of light and it was that illumination that saved many lives.

The Laconia's engines and dynamos had not yet been damaged. The torpedo had hit us well astern on the starboard side and the bulkheads seemed to be holding back from the engine room the flood of water that rushed in through the gaping hole in the ship's side. I proceeded down the boat deck to my station opposite boat No. 10. I looked over the side and down upon the water sixty feet below.

The sudden flashing of the lights on the upper deck[26] made the dark seething waters seem blacker and angrier. They rose and fell in troubled swells.

Steam began to hiss from some of the pipes leading up from the engine well. It seemed like a dying groan from the very vitals of the stricken ship. Clouds of white and black smoke rolled up from the giant grey funnels that towered above us.

Suddenly there was a roaring swish as a rocket soared upward from the Captain's bridge, leaving a comet's tail of fire. I watched it as it described a graceful arc and then with an audible pop it burst in a flare of brilliant colour. Its ascent had torn a lurid rent in the black sky and had cast a red glare over the roaring sea.

Already boat No. 10 was loading up and men and boys were busy with the ropes. I started to help near a davit that seemed to be giving trouble but was sternly ordered to get out of the way and to get into the boat.

Other passengers and members of the crew and officers of the ship were rushing to and fro along the deck strapping their life-preservers to them as they rushed. There was some shouting of orders but little or no confusion. One woman, a blonde French actress, became hysterical on the deck, but two men lifted her bodily off her feet and placed her in the life-boat.

We were on the port side of the ship, the higher side. To reach the boats, we had to climb up the slanting deck to the edge of the ship.

On the starboard side, it was different. On that side, the decks slanted down toward the water. The ship careened in that direction and the life-boats suspended from the davits swung clear of the ship's side.

The list of the ship increased. On the port side, we looked down the slanting side of the ship and noticed[27] that her water line on that side was a number of feet above the waves. The slant was so pronounced that the life-boats, instead of swinging clear from the davits, rested against the side of the ship. From my position in the life-boat I could see that we were going to have difficulty in the descent to the water.

"Lower away," some one gave the order and we started downward with a jerk toward the seemingly hungry, rising and falling swells. Then we stopped with another jerk and remained suspended in mid-air while the men at the bow and the stern swore and tusseled with the ropes.

The stern of the boat was down; the bow up, leaving us at an angle of about forty-five degrees. We clung to the seats to save ourselves from falling out.

"Who's got a knife? A knife! A knife!" shouted a fireman in the bow. He was bare to the waist and perspiration stood out in drops on his face and chest and made streaks through the coal dust with which his skin was grimed.

"Great Gawd! Give him a knife," bawled a half-dressed jibbering negro stoker who wrung his hands in the stern.

A hatchet was thrust into my hands and I forwarded it to the bow. There was a flash of sparks as it was brought down with a clang on the holding pulley. One strand of the rope parted.

Down plunged the bow of the boat too quickly for the men in the stern. We came to a jerky stop, this time with the stern in the air and the bow down, the dangerous angle reversed.

One man in the stern let the rope race through his blistered fingers. With hands burnt to the quick, he grabbed[28] the rope and stopped the precipitous descent just in time to bring the stern level with the bow.

Then bow and stern tried to lower away together. The slant of the ship's side had increased, so that our boat instead of sliding down it like a toboggan was held up on one side when the taffrail caught on one of the condenser exhaust pipes projecting slightly from the ship's side.

Thus the starboard side of the life-boat stuck fast and high while the port side dropped down and once more we found ourselves clinging on at a new angle and looking straight down into the water.

A hand slipped into mine and a voice sounded huskily close to my ear. It was the little old Jewish travelling man who was disliked in the smoke room because he used to speak too certainly of things about which he was uncertain. His slightly Teutonic dialect had made him as popular as the smallpox with the British passengers.

"My poy, I can't see nutting," he said. "My glasses slipped and I am falling. Hold me, please."

I managed to reach out and join hands with another man on the other side of the old man and together we held him in. He hung heavily over our arms, grotesquely grasping all he had saved from his stateroom—a gold-headed cane and an extra hat.

Many feet and hands pushed the boat from the side of the ship and we renewed our sagging, scraping, sliding, jerking descent. It ended as the bottom of the life-boat smacked squarely on the pillowy top of a rising swell. It felt more solid than mid-air at least.

But we were far from being off. The pulleys twice stuck in their fastings, bow and stern, and the one axe was passed forward and back (and with it my flashlight)[29] as the entangling mesh of ropes that held us to the sinking Laconia was cut away.

Some shout from that confusion of sound caused me to look up. I believe I really did so in the fear that one of the nearby boats was being lowered upon us.

Tin funnels enamelled white and containing clusters of electric bulbs hung over the side from one of the upper decks. I looked up into the cone of one of these lights and a bulky object shot suddenly out of the darkness into the scope of the electric rays.

It was a man. His arms were bent up at the elbows; his legs at the knees. He was jumping, with the intention, I feared, of landing in our boat, and I prepared to avoid the impact. But he had judged his distance well.

He plunged beyond us and into the water three feet from the edge of the boat. He sank from sight, leaving a white patch of bubbles and foam on the black water. He bobbed to the surface almost immediately.

"It's Dugan," shouted a man next to me.

I flashed a light on the ruddy, smiling face and water plastered hair of the little Canadian aviator, our fellow saloon passenger. We pulled him over the side and into the boat. He spluttered out a mouthful of water.

"I wonder if there is anything to that lighting three matches off the same match," he said. "I was trying to loosen the bow rope in this boat. I loosened it and then got tangled up in it. When the boat descended, I was jerked up back on the deck. Then I jumped for it. Holy Moses, but this water is cold."

As we pulled away from the side of the ship, its receding terraces of glowing port holes and deck lights towered above us. The ship was slowly turning over.

We were directly opposite the engine room section of the Laconia. There was a tangle of oars, spars and rigging[30] on the seats in our boat, and considerable confusion resulted before we could manage to place in operation some of the big oars on either side.

The jibbering, bullet-headed negro was pulling a sweep directly behind me and I turned to quiet him as his frantic reaches with the oar were jabbing me in the back.

In the dull light from the upper decks, I looked into his slanting face—his eyes all whites and his lips moving convulsively. He shivered with fright, but in addition to that he was freezing in the thin cotton shirt that composed his entire upper covering. He worked feverishly at the oar to warm himself.

"Get away from her. My Gawd, get away from her," he kept repeating. "When the water hits her hot boilers she'll blow up the whole ocean and there's just tons and tons of shrapnel in her hold."

His excitement spread to other members of the crew in our boat. The ship's baker, designated by his pantry headgear of white linen, became a competing alarmist and a white fireman, whose blasphemy was nothing short of profound, added to the confusion by cursing every one.

It was the tension of the minute—it was the give way of overwrought nerves—it was bedlam and nightmare.

I sought to establish some authority in our boat which was about to break out into full mutiny. I made my way to the stern. There, huddled up in a great overcoat and almost muffled in a ship's life-preserver, I came upon an old white-haired man and I remembered him.

He was a sea-captain of the old sailing days. He had been a second cabin passenger with whom I had talked before. Earlier in the year he had sailed out of Nova Scotia with a cargo of codfish. His schooner, the Secret, had broken in two in mid-ocean, but he and his[31] crew had been picked up by a tramp and taken back to New York.

From there he had sailed on another ship bound for Europe, but this ship, a Holland-American Liner, the Ryndam, had never reached the other side. In mid-Atlantic her captain had lost courage over the U-boat threats. He had turned the ship about and returned to America. Thus, the Laconia represented the third unsuccessful attempt of this grey-haired mariner to get back to his home in England. His name was Captain Dear.

"Our boat's rudder is gone, but we can stear with an oar," he said, in a weak-quavering voice—the thin high-pitched treble of age. "I will take charge, if you want me to, but my voice is gone. I can tell you what to do, but you will have to shout the orders. They won't listen to me."

There was only one way to get the attention of the crew, and that was by an overpowering blast of profanity. I called to my assistance every ear-splitting, soul-sizzling oath that I could think of.

I recited the lurid litany of the army mule skinner to his gentle charges and embellished it with excerpts from the remarks of a Chicago taxi chauffeur while he changed tires on the road with the temperature ten below.

It proved to be an effective combination, this brim-stoned oration of mine, because it was rewarded by silence.

"Is there a ship's officer in this boat?" I shouted. There was no answer.

"Is there a sailor or a seaman on board?" I inquired, and again there was silence from our group of passengers, firemen, stokers and deck swabs.[32]

They appeared to be listening to me and I wished to keep my hold on them. I racked my mind for some other query to make or some order to direct. Before the spell was broken I found one.

"We will now find out how many of us there are in this boat," I announced in the best tones of authority that I could assume. "The first man in the bow will count one and the next man to him will count two. We will count from the bow back to the stern, each man taking a number. Begin."

"One," came the quick response from a passenger who happened to be the first man in the bow. The enumeration continued sharply toward the stern. I spoke the last number.

"There are twenty-three of us here," I repeated, "there's not a ship's officer or seaman among us, but we are extremely fortunate to have with us an old sea-captain who has consented to take charge of the boat and save our lives. His voice is weak, but I will repeat the orders for him, so that all of you can hear. Are you ready to obey his orders?"

There was an almost unanimous acknowledgment of assent and order was restored.

"The first thing to be done," I announced upon Captain Dear's instructions, "is to get the same number of oars pulling on each side of the boat; to seat ourselves so as to keep on an even keel and then to keep the boat's head up into the wind so that we won't be swamped by the waves."

With some little difficulty, this rearrangement was accomplished and then we rested on our oars with all eyes turned on the still lighted Laconia. The torpedo had hit at about 10:30 P. M. according to our ship's time.[33] Though listing far over on one side, the Laconia was still afloat.

It must have been twenty minutes after that first shot that we heard another dull thud, which was accompanied by a noticeable drop in the hulk. The German submarine had despatched a second torpedo through the engine room and the boat's vitals from a distance of two hundred yards.

We watched silently during the next minute as the tiers of lights dimmed slowly from white to yellow, then to red and then nothing was left but the murky mourning of the night which hung over all like a pall.

A mean, cheese-coloured crescent of a moon revealed one horn above a rag bundle of clouds low in the distance. A rim of blackness settled around our little world, relieved only by a few leering stars in the zenith, and, where the Laconia's lights had shown, there remained only the dim outlines of a blacker hulk standing out above the water like a jagged headland, silhouetted against the overcast sky.

The ship sank rapidly at the stern until at last its nose rose out of the water, and stood straight up in the air. Then it slid silently down and out of sight like a piece of scenery in a panorama spectacle.

Boat No. 3 stood closest to the place where the ship had gone down. As a result of the after suction, the small life-boat rocked about in a perilous sea of clashing spars and wreckage.

As the boat's crew steadied its head into the wind, a black hulk, glistening wet and standing about eight feet above the surface of the water, approached slowly. It came to a stop opposite the boat and not ten feet from the side of it. It was the submarine.

"Vot ship vass dot?" were the first words of throaty[34] guttural English that came from a figure which projected from the conning tower.

"The Laconia," answered the Chief Steward Ballyn, who commanded the life-boat.

"Vot?"

"The Laconia, Cunard Line," responded the steward.

"Vot did she weigh?" was the next question from the submarine.

"Eighteen thousand tons."

"Any passengers?"

"Seventy-three," replied Ballyn, "many of them women and children—some of them in this boat. She had over two hundred in the crew."

"Did she carry cargo?"

"Yes."

"Iss der Captain in dot boat?"

"No," Ballyn answered.

"Well, I guess you'll be all right. A patrol will pick you up some time soon." Without further sound save for the almost silent fixing of the conning tower lid, the submarine moved off.

"I thought it best to make my answers sharp and satisfactory, sir," said Ballyn, when he repeated the conversation to me word for word. "I was thinking of the women and children in the boat. I feared every minute that somebody in our boat might make a hostile move, fire a revolver, or throw something at the submarine. I feared the consequence of such an act."

There was no assurance of an early pickup so we made preparations for a siege with the elements. The weather was a great factor. That black rim of clouds looked ominous. There was a good promise of rain. February has a reputation for nasty weather in the north Atlantic. The wind was cold and seemed to be rising. Our boat[35] bobbed about like a cork on the swells, which fortunately were not choppy.

How much rougher seas could the boat weather? This question and conditions were debated pro and con.

Had our rockets been seen? Did the first torpedo put the wireless out of commission? If it had been able to operate, had anybody heard our S. O. S.? Was there enough food and drinking water in the boat to last?

This brought us to an inventory of our small craft. After considerable difficulty, we found the lamp, a can of powder flares, the tin of ship's biscuit, matches and spare oil.

The lamp was lighted. Other lights were now visible. As we drifted in the darkness, we could see them every time we mounted the crest of the swells. The boats carrying these lights remained quite close together at first.

One boat came within sound and I recognised the Harry Lauder-like voice of the second assistant purser whom I had last heard on Wednesday at the ship's concert. Now he was singing—"I Want to Marry 'arry," and "I Love to be a Sailor."

There were an American woman and her husband in that boat. She told me later that an attempt had been made to sing "Tipperary," and "Rule Britannia," but the thought of that slinking dark hull of destruction that might have been a part of the immediate darkness resulted in the abandonment of the effort.

"Who's the officer in that boat?" came a cheery hail from the nearby light.

"What the hell is it to you?" our half frozen negro yelled out for no reason apparent to me other than possibly the relief of his feelings.

"Will somebody brain that skunk with a pin?" was[36] the inquiry of our profound oathsman, who also expressed regret that he happened to be sitting too far away from the negro to reach him. He accompanied the announcement with a warmth of language that must have relieved the negro of his chill.

The fear of the boats crashing together produced a general inclination toward maximum separation on the part of all the little units of survivors, with the result that soon the small crafts stretched out for several miles, their occupants all endeavoring to hold the heads of the boats into the wind.

Hours passed. The swells slopped over the sides of our boat and filled the bottom with water. We bailed it continually. Most of us were wet to the knees and shivering from the weakening effects of the icy water. Our hands were blistered from pulling at the oars. Our boat, bobbing about like a cork, produced terrific nausea, and our stomachs ached from vain wrenching.

And then we saw the first light—the first sign of help coming—the first searching glow of white radiance deep down the sombre sides of the black pot of night that hung over us. I don't know what direction it came from—none of us knew north from south—there was nothing but water and sky. But the light—it just came from over there where we pointed. We nudged dumb, sick boat mates and directed their gaze and aroused them to an appreciation of the sight that gave us new life.

It was 'way over there—first a trembling quiver of silver against the blackness, then drawing closer, it defined itself as a beckoning finger, although still too far away to see our feeble efforts to attract it.

Nevertheless, we wasted valuable flares and the ship's baker, self-ordained custodian of the biscuit, did the[37] honours handsomely to the extent of a biscuit apiece to each of the twenty-three occupants of the boat.

"Pull starboard, sonnies," sang out old Captain Dear, his grey chin whiskers bristling with joy in the light of the round lantern which he held aloft.

We pulled—pulled lustily, forgetting the strain and pain of innards torn and racked with violent vomiting, and oblivious of blistered palms and wet, half-frozen feet.

Then a nodding of that finger of light,—a happy, snapping, crap-shooting finger that seemed to say: "Come on, you men," like a dice player wooing the bones—led us to believe that our lights had been seen.

This was the fact, for immediately the oncoming vessel flashed on its green and red sidelights and we saw it was headed for our position. We floated off its stern for a while as it manœuvred for the best position in which it could take us on with a sea that was running higher and higher.

The risk of that rescuing ship was great, because there was every reason to believe that the submarine that had destroyed the Laconia still lurked in the darkness nearby, but those on board took the risk and stood by for the work of rescue.

"Come along side port!" was megaphoned to us. As fast as we could, we swung under the stern and felt our way broadside toward the ship's side.

Out of the darkness above, a dozen small pocket flashlights blinked down on us and orders began to be shouted fast and thick.

When I look back on the night, I don't know which was the more hazardous, going down the slanting side of the sinking Laconia or going up the side of the rescuing vessel.

One minute the swells would lift us almost level with[38] the rail of the low-built patrol boat and mine sweeper, but the next receding wave would swirl us down into a darksome gulf over which the ship's side glowered like a slimy, dripping cliff.

A score of hands reached out and we were suspended in the husky, tattooed arms of those doughty British Jack Tars, looking up into their weather-beaten youthful faces, mumbling our thankfulness and reading in the gold lettering on their pancake hats the legend, "H. M. S. Laburnum." We had been six hours in the open boat.

The others began coming alongside one by one. Wet and bedraggled survivors were lifted aboard. Women and children first was the rule.

The scenes of reunion were heart-gripping. Men who had remained strangers to one another aboard the Laconia, now wrung each other by the hand or embraced without shame the frail little wife of a Canadian chaplain who had found one of her missing children delivered up from another boat. She smothered the child with ravenous mother kisses while tears of gladness streamed down her face.

Boat after boat came alongside. The water-logged craft containing the Captain came last.

A rousing cheer went up as he stepped on the deck, one mangled hand hanging limp at his side.

The sailors divested themselves of outer clothing and passed the garments over to the shivering members of the Laconia's crew.

The cramped officers' quarters down under the quarter deck were turned over to the women and children. Two of the Laconia's stewardesses passed boiling basins of navy cocoa and aided in the disentangling of wet and matted tresses.

The men grouped themselves near steam-pipes in the[39] petty officers' quarters or over the grating of the engine rooms, where new life was to be had from the upward blasts of heated air that brought with them the smell of bilge water and oil and sulphur from the bowels of the vessel.

The injured—all minor cases, sprained backs, wrenched legs or mashed hands—were put away in bunks under the care of the ship's doctor.

Dawn was melting the eastern ocean grey to pink when the task was finished. In the officers' quarters, which had now been invaded by the men, the roll of the vessel was most perceptible. Each time the floor of the room slanted, bottles and cups and plates rolled and slid back and forth.

On the tables and chairs and benches the women rested. Sea-sick mothers, trembling from the after-effects of the terrifying experience of the night, sought to soothe their crying children.

Then somebody happened to touch a key on the small wooden organ that stood against one wall. This was enough to send some callous seafaring fingers over the ivory keys in a rhythm unquestionably religious and so irresistible under the circumstances that, although no one seemed to know the words, the air was taken up in a reverent, humming chant by all in the room.

At the last note of the Amen, little Father Warring, his black garb snaggled in places and badly soiled, stood before the centre table and lifted back his head until the morning light, filtering through the opened hatch above him, shown down on his kindly, weary face. He recited the Lord's prayer and all present joined. The simple, impressive service of thanksgiving ended as simply as it had begun.

Two minutes later I saw the old Jewish travelling man[40] limping about on one lame leg with a little boy in his arms. He was collecting big, round British pennies for the youngster.

A survey and cruise of the nearby waters revealed no more occupied boats and our mine sweeper, with its load of survivors numbering two hundred and sixty-seven, steamed away to the east. A half an hour steaming and the vessel stopped within hailing distance of two sister ships, toward one of which an open boat manned by jackies was being pulled.

I saw the hysterical French actress, her blonde hair wet and bedraggled, lifted out of the boat and carried up the companionway. Then a little boy, his fresh pink face and golden hair shining in the morning sun, was passed upward, followed by some other survivors, numbering fourteen in all, who had been found half-drowned and almost dead from exposure in a partially wrecked boat that was picked up just as it was sinking. It was in that boat that one American woman and her daughter died. One of the survivors of the boat told me the story. He said:

"Our boat was No. 8. It was smashed in the lowering. I was in the bow. Mrs. Hoy and her daughter were sitting toward the stern. The boat filled with water rapidly.

"It was no use trying to bail it out. There was a big hole in the side and it came in too fast. The boat's edge sank to the level of the water and only the air-tanks kept it afloat.

"It was completely awash. Every swell rode clear over our heads and we had to hold our breath until we came to the surface again. The cold water just takes the life out of you.[41]

"We saw the other boats showing their lights and drifting further and further away from us. We had no lights. And then, towards morning, we saw the rescuing ship come up into the cluster of other life-boats that had drifted so far away from us. One by one we saw their lights disappear as they were taken on board.

"We shouted and screamed and shrieked at the tops of our voices, but could not attract the attention of any of the other boats or the rescuing ship, and soon we saw its lights blink out. We were left there in the darkness with the wind howling and the sea rolling higher every minute.

"The women got weaker and weaker. Maybe they had been dead for some time. I don't know, but a wave came and washed both Mrs. Hoy and her daughter out of the boat. There were life-belts around their bodies and they drifted away with their arms locked about one another."

With such stories ringing in our ears, with exchanges of experiences pathetic and humorous, we steamed into Queenstown harbour shortly after ten o'clock that night. We had been attacked at a point two hundred miles off the Irish coast and of our passengers and crew, thirteen had been lost.

As I stepped ashore, a Britisher, a fellow-passenger aboard the Laconia, who knew me as an American, stepped up to me. During the voyage we had had many conversations concerning the possibility of America entering the war. Now he slapped me on the back with this question,

"Well, old Casus Belli," he said, "is this your blooming overt act?"

I did not answer him, but thirty minutes afterward I was pounding out on a typewriter the introduction to a[42] four thousand word newspaper article which I cabled that night and which put the question up to the American public for an answer.

Five weeks later the United States entered the war.[43]

Lean, clean, keen—that's the way they looked—that first trim little band of American fighting men who made their historic landing on the shores of England, June 8th, 1917.

I went down from London to meet them at the port of arrival. In my despatches of that date, I, nor none of the other correspondents, was permitted to mention the name of the port. This was supposed to be the secret that was to be religiously kept and the British censor was on the job religiously.

The name of the port was excluded from all American despatches but the British censor saw no reason to withhold transmission of the following sentence—"Pershing landed to-day at an English port and was given a hearty welcome by the Mayor of Liverpool."

So I am presuming at this late date of writing that it would serve no further purpose to refrain from announcing flatly that General John J. Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces overseas, and his staff, landed on the date above mentioned, at Liverpool, England.

The sun was shining brightly on the Mersey when the giant ocean liner, the Baltic, came slowly up the harbour in the tow of numerous puffing tugs. The great grey vessel that had safely completed the crossing of the submarine zone, was warped to the dock-side.

On the quay there were a full brass band and an honourary escort of British soldiers. While the moorings[44] were being fastened, General Pershing, with his staff, appeared on the promenade deck on the shore side of the vessel.

His appearance was the signal for a crash of cymbals and drums as the band blared out the "Star Spangled Banner." The American commander and the officers ranged in line on either side of him, stood stiffly at attention, with right hands raised in salute to the visors of their caps.

On the shore the lines of British soldiery brought their arms to the present with a snap. Civilian witnesses of the ceremony bared their heads. The first anthem was followed by the playing of "God Save the King." All present remained at the salute.

As the gangplank was lashed in place, a delegation of British military and civilian officials boarded the ship and were presented to the General. Below, on the dock, every newspaper correspondent and photographer in the British Isles, I think, stood waiting in a group that far outnumbered the other spectators.

There was reason for this seeming lack of proportion. The fact was that but very few people in all of England, as well as in all of the United States, had known that General Pershing was to land that day.

Few had known that he was on the water. The British Admiralty, then in complete control of the ocean lines between America and the British Isles, had guarded well the secret. England lost Kitchener on the sea and now with the sea peril increased a hundredfold, England took pains to guard well the passage of this standard-bearer of the American millions that were to come.

Pershing and his staff stepped ashore. Lean, clean, keen—those are the words that described their appearance. That was the way they impressed their critical[45] brothers in arms, the all-observing military dignities that presented Britain's hearty, unreserved welcome at the water's edge. That was the way they appeared to the proud American citizens, residents of those islands, who gathered to meet them.

The British soldiers admired the height and shoulders of our first military samples. The British soldier approves of a greyhound trimness in the belt zone. He likes to look on carriage and poise. He appreciates a steady eye and stiff jaw. He is attracted by a voice that rings sharp and firm. The British soldier calls such a combination, "a real soldier."

He saw one, and more than one, that morning shortly after nine o'clock when Pershing and his staff committed the date to history by setting foot on British soil. Behind the American commander walked a staff of American officers whose soldierly bearing and general appearance brought forth sincere expressions of commendation from the assemblage on the quay.

At attention on the dock, facing the sea-stained flanks of the liner Baltic, a company of Royal Welsh Fusiliers Stood like a frieze of clay models in stainless khaki, polished brass and shining leather.

General Pershing inspected the guard of honour with keen interest. Walking beside the American commander was the considerably stouter and somewhat shorter Lieutenant General Sir William Pitcairn Campbell, K.C.B., Chief of the Western Command of the British Home Forces.

Pershing's inspection of that guard was not the cursory one that these honourary affairs usually are. Not a detail of uniform or equipment on any of the men in the guard was overlooked. The American commander's attention was as keen to boots, rifles and belts, as though[46] he had been a captain preparing the small command for a strenuous inspection at the hands of some exacting superior.

As he walked down the stiff, standing line, his keen blue eyes taking in each one of the men from head to foot, he stopped suddenly in front of one man in the ranks. That man was File Three in the second set of fours. He was a pale-faced Tommy and on one of his sleeves there was displayed two slender gold bars, placed on the forearm.

The decoration was no larger than two matches in a

row and on that day it had been in use hardly more than

a year, yet neither its minuteness nor its meaning escaped

the eyes of the American commander.

Pershing turned sharply and faced File Three.

"Where did you get your two wounds?" he asked.

"At Givenchy and Lavenze, sir," replied File Three, his face pointed stiffly ahead. File Three, even now under twenty-one years of age, had received his wounds in the early fighting that is called the battle of Loos.

"You are a man," was the sincere, all-meaning rejoinder of the American commander, who accompanied his remark with a straightforward look into the eyes of File Three.

Completing the inspection without further incident, General Pershing and his staff faced the honour guard and stood at the salute, while once more the thunderous military band played the national anthems of America and Great Britain.

The ceremony was followed by a reception in the

cabin of the Baltic, where General Pershing received the

Lord Mayor of Liverpool, the Lady Mayoress, and a delegation

of civil authorities. The reception ended when

General Pershing spoke a few simple words to the assembled[47]

representatives of the British and American

Press.

"More of us are coming," was the keynote of his modest remarks. Afterward he was escorted to the quay-side station, where a special train of the type labelled Semi-Royal was ready to make the express run to London.

The reception at the dock had had none of the features of a demonstration by reason of the necessity for the ship's arrival being secret, but as soon as the Baltic had landed, the word of the American commander's arrival spread through Liverpool like wildfire.

The railroad from the station lay through an industrial section of the city. Through the railroad warehouses the news had preceded the train. Warehouse-men, porters and draymen crowded the tops of the cotton bales and oil barrels on both sides of the track as the train passed through.

Beyond the sheds, the news had spread through the many floors of the flour mills and when the Pershing train passed, handkerchiefs and caps fluttered from every crowded door and window in the whitened walls. Most of the waving was done by a new kind of flour-girl, one who did not wave an apron because none of them were dressed that way.

From his car window, General Pershing returned the greetings of the trousered girls and women who were making England's bread while their husbands, fathers, brothers, sweethearts and sons were making German cemeteries.

In London, General Pershing and his staff occupied suites at the Savoy Hotel, and during the four or five days of the American commander's sojourn in the capital of the British Empire, a seemingly endless line of[48] visitors of all the Allied nationalities called to present their compliments.

The enlisted men of the General's staff occupied quarters in the old stone barracks of the Tower of London, where they were the guests of the men of that artillery organisation which prefixes an "Honourable" to its name and has been assigned for centuries to garrison duty in the Tower of London.

Our soldiers manifested naïve interest in some of England's most revered traditions and particularly in connection with historical events related to the Tower of London. On the second day of their occupation of this old fortress, one of the warders, a "Beef-eater" in full mediæval regalia, was escorting a party of the Yanks through the dungeons.

He stopped in one dungeon and lined the party up in front of a stone block in the centre of the floor. After a silence of a full minute to produce a proper degree of impressiveness for the occasion, the warder announced, in a respectful whisper:

"This is where Anne Boleyn was executed."

The lined-up Yanks took a long look at the stone block. A silence followed during the inspection. And then one regular, desiring further information, but not wishing to be led into any traps of British wit, said:

"All right, I'll bite; what did Annie do?"

Current with the arrival of our men and their reception by the honour guard of the Welsh Fusiliers there was a widespread revival of an old story which the Americans liked to tell in the barrack rooms at night.

When the Welsh Fusiliers received our men at the dock of Liverpool, they had with them their historical mascot, a large white goat with horns encased in inscribed silver. The animal wore suspended from its neck[49] a large silver plate, on which was inscribed a partial history of the Welsh Fusiliers.

Some of these Fusiliers told our men the story.

"It was our regiment—the Welsh Fusiliers," one of them said, "that fought you Yanks at Bunker Hill. And it was at Bunker Hill that our regiment captured the great-great-granddaddy of this same white goat, and his descendants are ever destined to be the mascot of our regiment. You see, we have still got your goat."

"But you will notice," replied one of the Yanks, "we've got the hill."

During the four days in London, General Pershing was received by King George and Queen Mary at Buckingham Palace. The American commander engaged in several long conferences at the British War Office, and then with an exclusion of entertainment that was painful to the Europeans, he made arrangements to leave for his new post in France.

A specially written permission from General Pershing made it possible for me to accompany him on that historic crossing between England and France. Secret orders for the departure were given on the afternoon and evening of June 12th. Before four o'clock of the next morning, June 13th, I breakfasted in the otherwise deserted dining-room of the Savoy with the General and his staff.

Only a few sleepy-eyed attendants were in the halls and lower rooms of the Savoy. In closed automobiles we were whisked away to Charing Cross Station. We boarded a special train whose destination was unknown. The entire party was again in the hands of the Intelligence Section of the British Admiralty, and every possible means was taken to suppress all definite information concerning the departure.[50]

The special train containing General Pershing and his staff reached Folkstone at about seven o'clock in the morning. We left the train at the dockside and boarded the swift Channel steamer moored there. A small vociferous contingent of English Tommies returning to the front from leave in "Blighty" were crowded on all decks in the stern.

With life-boats swinging out over the side and every one wearing life-preservers, we steamed out of Folkstone harbour to challenge the submarine dangers of the Channel.

The American commander occupied a forward cabin suite on the upper deck. His aides and secretaries had already transformed it into a business-like apartment. In the General's mind there was no place or time for any consideration of the dangers of the Channel crossing. Although the very waters through which we dashed were known to be infested with submarines which would have looked upon him as capital prey, I don't believe the General ever gave them as much as a thought.

Every time I looked through the open door of his cabin, he was busy dictating letters to his secretaries or orders or instructions to his aides or conferring with his Chief of Staff, Brigadier General Harbord. To the American commander, the hours necessary for the dash across the Channel simply represented a little more time which he could devote to the plans for the great work ahead of him.

Our ship was guarded on all sides and above. Swift torpedo destroyers dashed to and fro under our bow and stern and circled us continually. In the air above hydro-airplanes and dirigible balloons hovered over the waters surrounding us, keeping sharp watch for the first appearance of the dark sub-sea hulks of destruction.

THE ARRIVAL IN LONDON, SHOWING GENERAL PERSHING, MR. PAGE,

FIELD MARSHAL VISCOUNT FRENCH, LORD DERBY,

AND ADMIRAL SIMS

THE ARRIVAL IN LONDON, SHOWING GENERAL PERSHING, MR. PAGE,

FIELD MARSHAL VISCOUNT FRENCH, LORD DERBY,

AND ADMIRAL SIMS

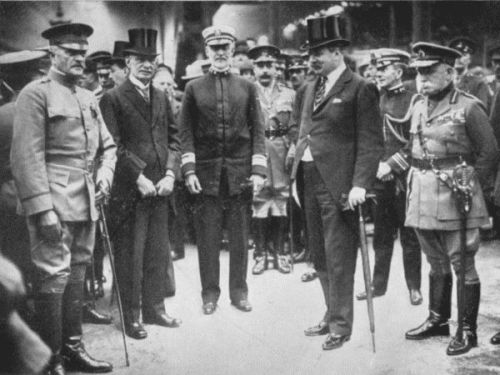

GENERAL PERSHING BOWING TO THE CROWD IN PARIS

GENERAL PERSHING BOWING TO THE CROWD IN PARIS

We did not learn until the next day that while we were making that Channel crossing, the German air forces had crossed the Channel in a daring daylight raid and were at that very hour dropping bombs on London around the very hotel which General Pershing had just vacated. Some day, after the war, I hope to ascertain whether the commander of that flight of bombing Gothas started on his expedition over London with a special purpose in view and whether that purpose concerned the supposed presence there of the commander-in-chief of the American millions that were later to change the entire complexion of the war against Germany.

It was a beautiful sunlight day. It was not long before the coast line of France began to push itself up through the distant Channel mists and make itself visible on the horizon. I stood in the bow of the ship looking toward the coast line and silent with thoughts concerning the momentousness of the approaching historical event.

It happened that I looked back amidships and saw a solitary figure standing on the bridge of the vessel. It was General Pershing. He seemed rapt in deep thought. He wore his cap straight on his head, the visor shading his eyes. He stood tall and erect, his hands behind him, his feet planted slightly apart to accommodate the gentle roll of the ship.

He faced due east and his eyes were directed toward the shores of that foreign land which we were approaching. It seemed to me as I watched him that his mind must have been travelling back more than a century to that day in history when another soldier had stood on the bridge of another vessel, crossing those same waters, but in an almost opposite direction.

It seemed to me that he must have been thinking of[52] that historical character who made just such a journey more than a hundred years before,—a great soldier who left his homeland to sail to other foreign shores halfway around the world and there to lend his sword in the fight for the sacred principles of Democracy. It seemed to me that day that Pershing thought of Lafayette.

As we drew close to the shore, I noticed an enormous concrete breakwater extending out from the harbour entrance. It was surmounted by a wooden railing and on the very end of it, straddling the rail, was a small French boy. His legs were bare and his feet were encased in heavy wooden shoes. On his head he wore a red stocking cap of the liberty type. As we came within hailing distance, he gave to us the first greeting that came from the shores of France to these first arriving American soldiers.

"Vive l'Amérique!" he shouted, cupping his hands to his mouth and sending his shrill voice across the water to us. Pershing on the bridge heard the salutation. He smiled, touched his hand to his hat and waved to the lad on the railing.

We landed that day at Boulogne, June 13th, 1917. Military bands massed on the quay, blared out the American National Anthem as the ship was warped alongside the dock. Other ships in the busy harbour began blowing whistles and ringing bells, loaded troop and hospital ships lying nearby burst forth into cheering. The news spread like contagion along the harbour front.

As the gangplank was lowered, French military dignitaries in dress uniforms resplendent with gold braid, buttons and medals, advanced to that part of the deck amidships where the General stood. They saluted respectfully and pronounced elaborate addresses in their native tongue. They were followed by numerous French Government[53] officials in civilian dress attire. The city, the department and the nation were represented in the populous delegations who presented their compliments, and conveyed to the American commander the of the entire people of France.

Under the train sheds on the dock, long stiff, standing ranks of French poilus wearing helmets and their light blue overcoats pinned back at the knees, presented arms as the General walked down the lines inspecting them. At one end of the line, rank upon rank of French marines, and sailors with their flat hats with red tassels, stood at attention awaiting inspection.

The docks and train sheds were decorated with French and American flags and yards and yards of the mutually-owned red, white and blue. Thousands of spectators began to gather in the streets near the station, and their continuous cheers sufficed to rapidly augment their own numbers.

Accompanied by a veteran French colonel, one of whose uniform sleeves was empty, General Pershing, as a guest of the city of Boulogne, took a motor ride through the streets of this busy port city. He was quickly returned to the station, where he and his staff boarded a special train for Paris. I went with them.

That train to Paris was, of necessity, slow. It proceeded slowly under orders and with a purpose. No one in France, with the exception of a select official circle, had been aware that General Pershing was arriving that day until about thirty minutes before his ship was warped into the dock at Boulogne. It has always been a mystery to me how the French managed to decorate the station at Boulogne upon such short notice.

Thus it was that the train crawled slowly toward Paris for the purpose of giving the French capital time[54] to throw off the coat of war weariness that it had worn for three and a half years and don gala attire for this occasion. Paris made full use of every minute of that time, as we found when the train arrived at the French capital late in the afternoon. The evening papers in Paris had carried the news of the American commander's landing on the shores of France, and Paris was ready to receive him as Paris had never before received a world's notable.

The sooty girders of the Gare du Nord shook with cheers when the special train pulled in. The aisles of the great terminal were carpeted with red plush. A battalion of bearded poilus of the Two Hundred and Thirty-seventh Colonial Regiment was lined up on the platform like a wall of silent grey, bristling with bayonets and shiny trench helmets.

General Pershing stepped from his private car. Flashlights boomed and batteries of camera men manœuvred into positions for the lens barrage. The band of the Garde Républicaine blared forth the strains of the "Star Spangled Banner," bringing all the military to a halt and a long standing salute. It was followed by the "Marseillaise."

At the conclusion of the train-side greetings and introductions, Marshal Joffre and General Pershing walked down the platform together. The tops of the cars of every train in the station were crowded with workmen. As the tall, slender American commander stepped into view, the privileged observers on the car-tops began to cheer.

A minute later, there was a terrific roar from beyond the walls of the station. The crowds outside had heard the cheering within. They took it up with thousands of[55] throats. They made their welcome a ringing one. Paris took Pershing by storm.

The General was ushered into the specially decorated reception chamber, which was hung and carpeted with brilliant red velvet and draped with the Allied flags. After a brief formal exchange of greetings in this large chamber, he and his staff were escorted to the line of waiting automobiles at the side of the station in the Rue de Roubaix.

Pershing's appearance in the open was the cue for wild, unstinted applause and cheering from the crowds which packed the streets and jammed the windows of the tall buildings opposite.

General Pershing and M. Painlevé, Minister of War, took seats in a large automobile. They were preceded by a motor containing United States Ambassador Sharp and former Premier Viviani. The procession started to the accompaniment of martial music by massed military bands in the courtyard of the station. It passed through the Rue de Compiègne, the Rue de Lafayette, the Place de l'Opéra, the Boulevard des Capucines, the Place de la Madeleine, the Rue Royale, to the Place de la Concorde.

There were some fifty automobiles in the line, the rear of which was brought up by an enormous motor-bus load of the first American soldiers from the ranks to pass through the streets of Paris.

The crowds overflowed the sidewalks. They extended from the building walls out beyond the curbs and into the streets, leaving but a narrow lane through which the motors pressed their way slowly and with the exercise of much care. From the crowded balconies and windows overlooking the route, women and children tossed down showers of flowers and bits of coloured paper.

The crowds were so dense that other street traffic became[56] marooned in the dense sea of joyously excited and gesticulating French people. Vehicles thus marooned immediately became islands of vantage. They were soon covered with men and women and children, who climbed on top of them and clung to the sides to get a better look at the khaki-clad occupants of the autos.

Old grey-haired fathers of French fighting men bared their heads and with tears streaming down their cheeks shouted greetings to the tall, thin, grey-moustached American commander who was leading new armies to the support of their sons. Women heaped armfuls of roses into the General's car and into the cars of other American officers that followed him. Paris street gamins climbed the lamp-posts and waved their caps and wooden shoes and shouted shrilly.

American flags and red, white and blue bunting waved wherever the eye rested. English-speaking Frenchmen proudly explained to the uninformed that "Pershing" was pronounced "Peur-chigne" and not "Pair-shang."

Paris was not backward in displaying its knowledge of English. Gay Parisiennes were eager to make use of all the English at their command, that they might welcome the new arrivals in their native tongue.

Some of these women shouted "Hello," "Heep, heep, hourrah," "Good morning," "How are you, keed?" and "Cock-tails for two." Some of the expressions were not so inappropriate as they sounded.